Abstract

Under-five child mortality remains a significant public health issue in Bangladesh and other developing countries. Identifying key risk factors within a hierarchical data structure is crucial for improving health system performance. This study employed the Fine-Gray Frailty (FGF) model to Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) data to assess child mortality from disease-related causes, treating non-disease-related deaths as competing risks in hierarchical framework. The model was also applied by considering non-disease deaths as the main event in a subsequent analysis. Findings reveal that maternal age, child sex, birth order, and regional variation remain significant determinants of mortality after adjusting for the hierarchical data structure. Children of mothers older than 30 years face a significantly higher risk of non-disease deaths compared with those aged 20–30 years. Male children experience higher mortality than females for both disease and non-disease causes. Higher birth order is associated with a lower risk of non-disease mortality. Regionally, Khulna shows a significantly increasing hazard of non-disease deaths than Barisal. This study underscores the value of hierarchical competing risk models for guiding targeted public health interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The infant mortality rate is frequently used by researchers and decision-makers as an indicator of a nation’s health, in particular to capture the socioeconomic development of a country. This indicator offers a comprehensive view of the socioeconomic status, cultural norms, health care quality,neighbourhood and national environment1. In Bangladesh and other developing nations, under-five mortality is still a major public health concern due to the differences in healthcare access, socioeconomic status, maternal and child health interventions. Despite gradual progress, Bangladesh’s child mortality rate further continues to decline in order to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)2. According to World Health Organisation (WHO), globally a dramatic decline from 12.7 million in 1990 to 4.9 million in 2022 in child mortality rates3. Bangladesh’s infant mortality rates have drastically decreased over the last three decades, falling from 133 deaths to 25 per 1000 live births, or an 81 percent drop from 1989 to 20222.

It is crucial to examine trends, risk factors, and intervention tactics in Bangladesh since the decline in under-five mortality is a crucial indicator of a country’s overall progress and healthcare efficacy. Numerous studies have been conducted on the demographic and socioeconomic factors associated with death among children under five in Bangladesh. These includes gender, the child’s birth order, birth weight, and size, the mother’s age at birth, her education, her number of pregnancies, her height and weight, household wealth and poverty, occupation of the parents, household sanitation facilities, and living in rural areas4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11.

Statistical analysis of data from the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) is crucial for identifying clinical prognostic factors, informing potential therapeutic development, and designing evidence-based intervention strategies. Many statistical methods have been applied in BDHS data to identify important factors for the occurrence of death or cure by either ignoring the competing events or using inappropriate regression-based statistical methods. For instance, Karmaker et al. employed the Cox Proportional Hazard (PH) model to assess the causes of under-five mortality in Bangladesh12. In the presence of competing risks (CRs) data, the traditional technique such as Kaplan–Meier for the estimation of Cumulative Incidence Function (CIF) to assess different exposures overestimate the CIFs over time compared with a Cause Specific Hazard (CSH) regression approach13,14,15,16. The major limitation of using PH model (which examines the effect of covariates on the CSH function) in a CRs setup is that during estimation of regression parameters under a specific cause it considers the individuals failing from causes other than cause of interest as censored observations17. The solution of this problem is to apply Fine-Gray regression model18 based on CIF which does not ignore the other competing risks when a specific cause is of interest17,19. Another paper by Mohammad13 considered CRs settings but ignore the hierarchical nature of the data. Thus, one of the objectives of this paper is to consider the CRs settings under hierarchical structure to estimate the likelihood of the event of interest among the numerous potential outcomes over time. In particular, the hierarchical nature of the BDHS child mortality data is considered across different region using two regression approaches: Fine-Gray frailty (FGF) model and CIF. Traditional CRs model such as cause-specific hazard (CSH) model, Fine-Gray sub-distribution hazard (SDH) model does not allow the hierarchical component of the data. Thus, Fine-Gray Frailty (FGF) Model with hierarchical likelihood (H-likelihood) estimation technique20,21 has been used for this study. The main idea is to consider the heterogeneity in risk factors among different clusters. The technical detail of this technique is beyond the scope of this paper and can be found in20. Furthermore, to compare H-Likelihood model and proportional hazard (PH) model, the CIF has been used. The application of CIF is shown by assessing a certain subject’s risk with the desired specified exposures from the fitted regression models to see the model-based prediction. The quantity CIF estimates the marginal likelihood of patients who actually developed the event of interest, no matter if a patient was censored or failed in other competing events. The graphical representation of CIF curves is always appealing and, thus, is popular in medical research. Computation and graphical representation of the CIF curves between different risk factor groups are straightforward and always possible to help one make personalized individual clinical decisions14. Nowadays, competing risks (CRs) data are found in many fields, ranging from medicine to epidemiology. Therefore, the construction of accurate regression models for competing risks data based on the two discussed approaches (the frailty and SDH methods) is of potentially great interest in many other contexts and applied fields.

Methodology

Study design

A cross-sectional analytical design using secondary data from the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) 2022 is used for this study. The BDHS is a nationally representative survey conducted by the National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) in collaboration with ICF International under the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program. The survey entailed a two-stage stratified cluster sampling design ensuring representation across all eight administrative divisions as well as urban and rural areas of Bangladesh. In the first stage, enumeration areas (EAs) were selected from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) sampling frame. In the second stage, households were systematically selected from each EA, and eligible ever-married women aged 15–49 years were interviewed.

Data sources

Two data sets were used in this study. One is the Verbal Autopsy (VA) dataset which contains cause-of-death information for 503 deceased children under five years of age. The causes of death were determined through standardized WHO verbal autopsy protocols. However, the VA dataset does not include socio-demographic or household information. Another is the Birth Recode (BR) dataset which includes detailed information on live births (n = 64,722) within the five years preceding the survey, covering maternal, household, and child characteristics.

Data merging and sample construction

To obtain both mortality outcomes and socio-demographic characteristics, the VA dataset was merged with the BR dataset using the unique case identifier (CASEID, cluster number, household number, mother’s line number and child’s birthdate). Since multiple children can be born to the same mother, each mother was treated as a cluster in the analytical design. All live-born children from the BR dataset who could be successfully matched with the VA records and had complete information on age at death, cause of death, and selected covariates were included in the analysis. Observations were excluded if the unique identifiers were missing or inconsistent across datasets, if the child’s age at death was unavailable or implausible, or if the cause of death was unspecified or indeterminate.

After merging the dataset, finally we analyze 1039 observations with 388 unique mothers where 203 children have been identified death due to the disease-related causes, 203 deaths due to non-disease-related causes, and 42 have unidentified and undefined information (Fig. 1). All variables used in the analysis were complete with no missing values in the final merged dataset. As a result, no imputation procedures or sensitivity analyses were necessary.

Study variables

The response variable is time to the occurrence of event of interest (for instance disease related events as main event and other causes of death as competing and vice versa). The events and risk factors are considered as follows:

On the basis of literature review on child mortality13,22,23,24,25,26,27 the covariates considered in this paper are: Mother’s age, Gender of child, Birthdate difference, Birth order, media, family size, division, mother’s education, father’s education, wealth status, place of residence, religion.

To achieve our study’s goal, we first consider death from a disease-related cause to be the main event of interest, with non-disease-related causes and other events being considered as competing events. Further, we considered non-disease-related causes as a main event of interest, with disease-related causes and others being regarded as competing events (Table 1).

Statistical models

Traditional CR models such as CSH models and Fine-Gray SDH models do not allow hierarchical components. Therefore, FGF Model is used to estimate the model parameters using H-likelihood multicomponent estimation procedures20,21 for this study. The H-likelihood multicomponent approach is the extended version of the H-likelihood estimation procedure of one component.

Let \({T}_{ij}\) denote the survival time of the \(j\)-th child in the \(i\)-th cluster, and \(k\in \{\text{1,2},3\}\) denote the cause of death. The sub-distribution hazard function for cause \(k\) conditional on cluster-specific frailty \({v}_{i}\) is defined as:

where, \({h}_{k0}\left(t\right)\) is the baseline sub-distribution hazard, \({X}_{ij}\) is the vector of covariates, \({\beta }_{k}\) is the regression coefficient vector, and \({v}_{i}\sim N(0,\theta )\) is the random effect capturing unobserved heterogeneity within clusters.

The hierarchical likelihood (H-likelihood) for the FGF model is given by:

where, \(\iota_{1} = \mathop \sum \limits_{i,j} {\text{log}}\left\{ {\left( {f_{{\left( {\beta , \lambda_{0} } \right)}} (y_{ij} , \delta_{ij} {|}v_{i} } \right)} \right\}\) and \(\iota_{2} = \iota_{2} \left( {\alpha ;v} \right) = \log \left( {f_{\alpha } \left( v \right)} \right)\).

Here, \({f}_{(\beta ,{\lambda }_{0})}({y}_{ij},{\delta }_{ij}\mid {v}_{i})\) is the conditional likelihood for observation \((i,j)\), and \({f}_{\alpha }({v}_{i})\) is the marginal distribution of the frailty term.

The nuisance baseline parameter \({\lambda }_{0}\) is removed through profiling, producing the profile log-likelihood:

where \(\iota_{1p}\) denotes the partial log-likelihood independent of \(\lambda_{0}\).

Thus, the generalized partial H-likelihood becomes:

Model parameters (\(\beta ,\theta\)) were estimated iteratively using the H-likelihood multicomponent algorithm, which jointly maximizes the marginal likelihood of fixed and random effects without requiring numerical integration. Variance components (\(\theta\)) were estimated using the adjusted profile likelihood derived from the curvature of the H-likelihood function. As the H-likelihood FGF model accounts for hierarchical clustering through random effects, it does not rely on the traditional proportional SDH assumption used in standard Fine-Gray models. Nevertheless, the proportionality of SDH was checked graphically using CIF plots, which confirmed no major violations.

The CIF for the main event of interest was estimated as:

where, \(\widehat{{\lambda }_{k0}}\left(t\right)\) is the baseline cumulative SDH function for cause k at time t and \(\beta\) are the vector of the parameter of the models.

The Fine–Gray SDH model was chosen because it directly estimates the cumulative incidence of competing events, making risk estimates more interpretable for policy and public health than cause-specific or Cox frailty models treating competing events. To account for children within mothers, a hierarchical H-likelihood extension was used. This approach addresses within-cluster correlation and unobserved heterogeneity, producing more robust estimates than models assuming independence.

Results

Table 2 presents the distribution of child mortality and its causes among 1,039 observations by regional, socioeconomic, and demographic characteristics.

Mortality patterns are different for various divisions. In particular, for Barisal divison, 12 children (10.17%) died from disease-related causes, 21 (17.80%) from non-disease causes, 8 (6.78%) from external causes, and 77 (65.25%) were censored (survived). In Chattogram, 17 (8.85%) were disease-related deaths, 37 (19.27%) non-disease, 9 (4.69%) external, and 129 (67.19%) censored. Dhaka division recorded 19 (15.97%) disease-related deaths, 22 (18.49%) non-disease, no external deaths, and 78 (65.55%) censored. Khulna division had comparatively higher non-disease mortality, with 7 (8.97%) disease-related, 25 (32.05%) non-disease, 1 (1.28%) external, and 45 (57.69%) censored. Mymensingh and Sylhet divisions experienced higher survival rates, in which Mymensingh experienced 18 (12.16%) disease-related deaths and Sylhet 27 (14.29%). Rajshahi and Rangpur division experienced the same pattern, where non-disease mortality was relatively high (24.69% and 25.44%, respectively).

Upon comparison of type of residence, urban residence revealed 44 (13.06%) disease-related, 67 (19.88%) non-disease, 5 (1.48%) external, and 221 (65.58%) censored cases, while rural residence revealed 75 (10.68%) disease-related, 134 (19.09%) non-disease, 24 (3.42%) external, and 469 (66.81%) censored cases. While the overall death patterns were similar across areas, deaths from external causes occurred more frequently in rural regions.

Maternal education revealed a clear gradient in the mortality outcomes. For mothers with no education, 11 (10.68%) of the deaths were related to disease, 8 (7.77%) non-disease, and 82 (79.61%) censored. With higher education, mortality also increased as individuals with higher education recorded 12 (13.95%) disease-related and 28 (32.56%) non-disease deaths, while the proportion of censored cases decreased to 50.00%. Similar pattern was observed for father’s education, as secondary and above secondary educated fathers have reported relatively higher non-disease mortality (20.87% and 20.09%) and fewer censored cases (62.62% and 65.89%).

Maternal age at delivery showed distinct differences across groups. Among the 19 years and below age group of mothers, 21 (9.01%) children died due to disease-related and 44 (18.88%) non-disease related reasons, while 69.96% survived. In the 20–30 years age group of mothers, 85 (12.69%) were disease-related and 116 (17.31%) non-disease deaths, while in the age group of mothers above 30 years, non-disease mortality was high at 30.15% and survival was lower at 55.15%.

The findings reveal that religious affiliation has a negligeable differences. Within Muslim families, 113 (11.51%) of the deaths were disease-related and 185 (18.84%) non-disease-related, with a 66.70% survival percentage. Within other religions, 6 (10.53%) were disease-related and 16 (28.07%) non-disease-related, with 61.40% censored cases. Socioeconomic status was moderately correlated with mortality. The poor families experienced 62 (11.21%) disease-related and 100 (18.08%) non-disease deaths, while middle-income families experienced slightly increased non-disease mortality (22.11%). The wealthiest quintile experienced 32 (10.81%) disease-related and 59 (19.93%) non-disease deaths, with 66.22% survival.

The findings highlight gender disparity, for instance, male. children experienced higher mortality compared to female children, with 70 (13.62%) disease-related, 112 (21.79%) non-disease, and 21 (4.09%) external deaths among males, whereas females had 49 (9.33%) disease-related, 89 (16.95%) non-disease, and 8 (1.52%) external deaths. Female survival (72.19%) was considerably higher than male survival (60.51%). Media exposure also showed variation. The deaths due to disease and non-disease among the households with media exposure were 57 (11.70%) and 108 (22.18%), respectively, and those without exposure were 62 (11.23%) and 93 (16.85%), respectively.

Table 3 shows the background characteristics of Child Mortality and Survival. The mean mother age at first birth is 23.47 years and 75% of mothers took their first child before the age of 26.92 years. The mean interval between the 1st and 2nd births is 1403.9 days. 25% of mothers took their second child with 692.8 days gap where 75% of mothers took their second child before 1835.8 days. The mean interval between the 2nd and 3rd birth is 1501 days whereas this gap was reduced by 160 days for taking the fourth birth. The table further shows that 25% of families have 4 members where the average family size is almost 5.

Figure 2 depicts that the survival rate of children and cause of death over 2017–2022. It shows that the survival rate of children has increased in these periods. In 2017, the rate was approximately 25% with an increment of 100% in 2022. The death rate due to main event and due to non-disease has decreased over a year except in 2021 with the lowest death rate due to main event is approximately 27% and it slightly increased in 2022.

Figure 3 shows the survival probability curve for both main event of interest and non-disease. From both the curves, we observed a steep drop in survival probability within the first 1,500 days (~ 4 years), indicating higher child mortality during early childhood due to main cause of death and non-disease-related causes. After that initial decline, the survival curve stabilizes, suggesting that mortality risks decrease significantly as children grow older.

Table 4 presents the estimated sub distribution hazard ratios (SHRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from the hierarchical competing risk model for both disease-related and non-disease-related child deaths.

For disease-related deaths, the risk was lower among mothers younger than 20 years (SHR = 0.67; 95% CI 0.41–1.10) and slightly lower among mothers older than 30 years (SHR = 0.78; 95% CI 0.40–1.54), compared with mothers aged 20–29 years. Moreover, female children showed a reduced risk, with 35%, and that is statistically significant (SHR = 0.65; 95% CI 0.45–0.94). The hazard decreased with higher birth order (SHR = 0.86; 95% CI 0.70–1.05) but remained statistically insignificant. Regional variation was modest; however, children in the Sylhet division had slightly higher risks (SHR = 1.71; 95% CI 0.84–3.50) where Rajshahi, Khulna and Chattogram show the lower risk, with approximately 7%, 9% and 11% respectively, relative to Barisal but remained statistically insignificant. Children from rich families show approximately 35% (0.6579; 95% CI 0.387–1.1183) lower risk than children from poor families but with the cost of insignificant result. Parental education and residence showed no significant strong association, although the direction of the estimates suggested a protective effect with increasing education and economic status.

For non-disease-related deaths, the risk increased sharply among children born to mothers older than 30 years (SHR = 2.39; 95% CI 1.54–3.72). Female children were less likely to die from non-disease causes (SHR = 0.73; 95% CI 0.55–0.98). The hazard decreased significantly with increasing birth order (SHR = 0.78; 95% CI: 0.66–0.92), indicating that firstborns were more vulnerable to non-disease related death. Children of highly educated mothers had notably higher SHR values (e.g., secondary = 2.51; higher = 4.61), this emphasizes the necessity of a comprehensive strategy that incorporates education as part of larger initiatives to lower child mortality and enhance general child health outcomes. Regional effects were observed in Khulna (SHR = 1.97; 95% CI 1.06–3.66) but the effects are at the border line (close to 1) and insignificant effect for Rangpur (SHR = 1.57; 95% CI 0.88–2.82), where non-disease mortality appeared elevated compared to Barisal.

Across both models, variables such as media exposure, family size, and household wealth showed limited influence on child survival after adjusting for hierarchical clustering at the maternal level. Overall, the model indicates that maternal age, child sex, birth order, and regional variation are the most consistent predictors of child mortality under competing risks (Fig. 4).

Figure 5 plotted the frailty effects for each mother. The frailty variance is 0.0425 and the p-value indicates that based on this dataset there are no frailty effects for mothers in child mortality.

CIF Graphs for the main event of interest and competing events

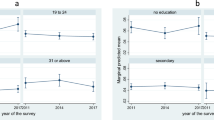

Figure 6 shows comparison of CIFs for disease-related child mortality between the PH model (left panels) and the H-Likelihood Frailty model (right panels).

Across divisions, both models identify Khulna as high-risk regions, though the H-Likelihood model produces lower overall cumulative incidence, indicating that frailty effects reduce the apparent baseline risk. Male children consistently show higher cumulative incidence than females in both models. By maternal education, children of higher-educated mothers exhibit the highest CIF values, suggesting that factors beyond education, such as better reporting or smaller family size, may influence observed mortality. Moreover, cause-specific models can give different (and sometimes apparently counterintuitive) results compared with all-cause analyses. In terms of place of residence, children in urban areas have higher risk of non-disease-related death than rural areas in both models. Overall, while both models yield almost similar rank patterns across subgroups, the H-Likelihood model systematically predicts lower absolute probabilities due to its adjustment for unobserved heterogeneity.

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of child mortality in Bangladesh along with the significant effects of socio-demographic variables on child mortality.

It indicates that children of mothers younger than 20 and older than 30 have a lower likelihood of dying from disease-related causes, but a higher risk of death from non-disease (perinatal-related) causes compared with those whose mothers are aged 20–30 years. Hofferth, S. L., & Hayes, C. D. have shown that children of teenage mothers face numerous risks such as low birth weight, and health-related problems which can lead children to perinatal death28. In a study, Myrskylä, M., et al., found children of young and old mothers have worse condition in health and have higher mortality than those born to mothers aged 25–34 years29.

Male children are more likely to have disease-related occurrences than female children. Generally, morbidity and mortality rates are higher in males than in females throughout life30.

Children in the Khulna division are slightly less likely to die from disease-related causes than those in Barisal, while the risk is also lower in Rajshahi and Chattogram. Mymensingh shows a relatively higher level of disease-related mortality compared with Barisal31. Rural–urban differences were observed, with disease-related deaths being somewhat higher among urban children, whereas non-disease deaths were almost similar across residence types. Environmental hazards may still play an important role in these circumstances. This finding coincides with the study of Tabassum and Bari32.

This study also shows that higher maternal education appears to be associated with an increasing risk of death due to non-disease causes, which may reflect contextual or behavioral factors rather than a direct causal link. Children from middle- and higher-income families experienced slightly lower non-disease mortality than those from poorer households. Moreover, children from Muslim families were at a lower risk of death than those from other religions. According to the Bangladesh Sample Vital Statistics (2020), male children remain more vulnerable to childhood mortality than females, particularly in Dhaka, Mymensingh, and Rajshahi divisions, while Muslim children were found to be more likely than others to die in childhood33.

The Kaplan–Meier survival curves and cumulative incidence function (CIF) plots provided valuable visual insights into mortality risks over time and across different strata. These plots revealed high early childhood mortality, particularly within the first 1,500 days, emphasizing the critical need for focused interventions during this vulnerable period. Moreover, the CIF analysis underscored the differential risks across divisions, wealth quintiles, and maternal education levels, reinforcing the importance of context-specific public health strategies.

The main limitation of this study lies in the relatively small data size. Although the BDHS provides nationally representative data, information on deceased children is limited and not included in the main birth recode file, thereby constraining the effective sample size for mortality analysis. Consequently, the limited number of events in certain cause-specific categories may have reduced the statistical power, resulting in wider confidence intervals and some non-significant estimates. Moreover, the inferential process is constrained by the use of the newly implemented H-likelihood framework, which, while advantageous for capturing cluster-level heterogeneity, complicates direct comparison with traditional approaches. Nonetheless, model comparisons revealed several noteworthy differences between the PH and H-likelihood models. While both produced consistent directional trends, the H-likelihood model estimated lower cumulative incidence probabilities and smaller standard errors for deaths due to the main event of interest. This difference highlights how alternative modelling frameworks can yield varying interpretations of mortality risk, underscoring the importance of careful model selection and validation in competing-risk analysis.

Finally, the outcomes of this study highlight the importance of specialized public health initiatives to reduce child mortality in Bangladesh. Maternal health education should be addressed and ensured, particularly for teenage mothers and women over the age of 30. Although maternal education has been demonstrated to have a favourable impact on child death rates in Bangladesh, it might not be sufficient on its own to completely address the ingrained socioeconomic differences that lead to health disparities36,37. This emphasizes the necessity of a comprehensive strategy that incorporates education as part of larger initiatives to lower child mortality and enhance general child health outcomes. Another study reported that education of mothers had no significant effect in reducing sex or household socioeconomic status-based differentials in under-five mortality over the time34,36,37. Cause-specific models can give different (and sometimes apparently counterintuitive) results compared with all-cause analyses35. Underserved areas with poor health facilities should be developed by the government, and NGOs should also work on them. A poverty alleviation program should be made available to low-income families in order to ensure healthy childbirth. Community and religious leaders should encourage basic maternal health habits during community or religious meetings. Overall, an educated generation should be ensured for improved child survival.

Conclusion

The study reveals that socio-demographic, geographic, and maternal factors significantly influence child mortality in Bangladesh. Maternal age has been found to be a significant factor in this study. Children who are born to teenage or older mothers face higher risks. Gender differences also contribute to mortality risks. Male children are more vulnerable to disease-related occurrences. Rural children are more susceptible to disease-related mortality due to environmental hazards and limited healthcare access. Maternal education, family income, and religious background are also significant determinants of mortality. The study suggests a hierarchical approach to child survival, emphasizing maternal education, equitable healthcare access, and targeted regional strategies to reduce mortality disparities. Policymakers and healthcare practitioners should focus on context-specific strategies to improve child health outcomes in Bangladesh. It is important to use caution when interpreting our results that higher maternal education is linked to higher disease-specific mortality for certain causes. Risk factors may have different associations with specific causes compared with all-cause under-5 mortality, according to recent cause-specific analyses conducted in Bangladesh. In other words, a factor that protects against infectious neonatal deaths may have a weaker or no protective effect for other causes that manifest later. Children of educated mothers may survive early infectious hazards but remain susceptible to other cause-groups due to regional and temporal variations in the cause-mix (declining infectious mortality but a relative rise in congenital, injury, and non-communicable causes). Therefore, in order to evaluate unexpected relationships, cause-specific models, rather than all-cause under five mortality, are crucial.

Data availability

Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS), 2022 data is available in [https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm] This study used anonymized secondary data from the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) 2022, accessed with permission from the DHS Program. The BDHS was approved by the ICF International IRB and the Bangladesh Medical Research Council (BMRC). As only de-identified data were used, no further ethical approval was required.

References

Kumar, P. P. & File, G. Infant and child mortality in Ethiopia: A statistical analysis approach. Ethiop. J. Educ. Sci. 5(2), 51–57 (2010).

Niport, M. et al. ICF international: Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2014. Dhaka, Bangladesh and Rockville: NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International (2016).

WHO Children: Reducing mortality 2022. https://www.who.int/news/item/13-03-2024-global-child-deaths-reach-historic-low-in-2022---un-report. Accessed 13 Mar 2024.

Kabir, A., Islam, M. S., Ahmed, M. S. & Barbhuiya, K. Factors influencing infant and child mortality in Bangladesh. J Med Sci. 5, 292–295 (2001).

Hossain, M. & Islam, M. Socio-economic variables affecting infants and children mortality in Bangladesh. Internet J Health. 9(2), 1–7 (2009).

Nure Alam, S., Nuruzzaman, H. & Abdul, G. Differentials and determinants of under-five mortality in Bangladesh. Int J Curr Res. 3(3), 142–148 (2011).

Rahman, M. et al. Impact of environmental sanitation and crowding on infant mortality in rural Bangladesh. Lancet 2, 28–30 (1985).

Hossain, M. M., Mani, K. K. C. & Islam, M. R. Prevalence and determinants of the gender differentials risk factors of child deaths in Bangladesh: evidence from the Bangladesh demographic and health survey, 2011. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9, e0003616 (2015).

Abir, T. et al. Risk factors for under-5 mortality: evidence from Bangladesh demographic and health survey, 2004–2011. BMJ Open 5, e006722 (2015).

Kabir, A., Islam, M. S. & Ahmed, M. S. Factors influencing infant and child mortality in Bangladesh. J Med Sci 5, 292–295 (2001).

Khan, M. A. et al. Trends and projections of under-5 mortality in Bangladesh including the effects of maternal high-risk fertility behaviours and use of healthcare services. PLoS ONE 16, e0246210 (2021).

Karmaker, S., Lahiry, S., Roy, D. & Singha, B. Determinants of infant and child mortality in Bangladesh: Time trends and comparisons across South Asia. Bangladesh J Med Sci. 13(4), 431–437 (2014).

Mohammad, K. A., Fatima-Tuz-Zahura, M. & Bari, W. Fine and Gray competing risk regression model to study the cause-specific under-five child mortality in Bangladesh. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 17, 1–8 (2017).

Haque, M. A. & Cortese, G. Cumulative incidence functions for competing risks survival data from subjects with COVID-19. Mathematics 11(17), 3772 (2023).

Austin, P. C., Lee, D. S. & Fine, J. P. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis overestimates cumulative incidence of health-related events in competing risk settings: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 93, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.005 (2017).

Latouche, A., Porcher, R. & Chevret, S. Sample size formula for proportional hazards modeling of competing risks. Stat. Med. 24(18), 3247–3257. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2164 (2005).

Porta, N., Gomez, G., Calle, M. L. & Malats, N. Competing risks methods (2007). http://upcommons.upc.edu/bitstream/handle/2117/2201/TR_CR. pdf?sequence=1.

Fine, J. P. & Gray, R. J. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 94, 496–509 (1999).

Coviello, V. & Boggess, M. Cumulative incidence estimation in the presence of competing risks. The Stat. J. 4(2), 103–112 (2004).

Ha, I. D., Christian, N. J., Jeong, J. H., Park, J. & Lee, Y. Analysis of clustered competing risks data using subdistribution hazard models with multivariate frailties. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 25(6), 2488–2505 (2016).

Ha, I. D., Jeong, J. H. & Lee, Y. Statistical Modelling of Survival Data with Random Effects: H Likelihood Approach (Springer Publishing Company, 2018).

Baqui, A. H., Arifeen, S. E., Akhter, T., Chowdhury, H. R., Rahman, K. M., Chowdhury, E. K., Alam, N. & Emdadul Haque, D. M. Causes of death in children under five years of age in Bangladesh, Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey. Dhaka: National Institute of Population Research and Training, Mitra and Associates, and ORC Macro (1998).

Chowdhury, A. Determinants of under-five mortality in Bangladesh. Open J. Stat. 3, 213–219 (2013).

Chowdhury, Q. H., Islam, R. & Hossain, K. Socio-economic determinants of neonatal, post neonatal, infant and child mortality. Int. J. Soc. Anthropol. 2(6), 118–125 (2010).

Haque, M. N., Siddiqi, N. A. & Goni, M. A. Differentials and determinants of under-5 mortality in Bangladesh. Int. J. Curr. Res. 3(3), 142–148 (2011).

Mozumder, K. A. & Khuda, B. Kane TT. Determinants of infant and child mortality in rural Bangladesh. ICDDR; 1998. B Working Paper No. 115.

Uddin, M. J., Hossain, M. Z. & Ullah, M. O. Child mortality in a developing country: A statistical research. J. Appl. Quant. Methods. 4(2), 142–148 (2009).

Hofferth, S. L. & Hayes, C. D. Risking the future: Adolescent sexuality, pregnancy, and childbearing, volume II: Working papers and statistical appendices.

Myrskylä, M. & Fenelon, A. Maternal age and offspring adult health: evidence from the health and retirement study. Demography 49, 1231–1257 (2012).

Lozano, R. et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. The Lancet. 380(9859), 2095–2128 (2012).

Rahman, A. & Hossain, M. M. Prevalence and determinants of fever, ARI and diarrhea among children aged 6–59 months in Bangladesh. BMC Pediatr. 22(1), 117 (2022).

Tabassum, T. & Bari, W. Competing risks analysis of under-five child mortality in Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Sci. Res. 27(1), 27–38 (2014).

Chowdhury, A. H., Hanifi, S. M. A., Mia, M. N. & Bhuiya, A. Socioeconomic inequalities in under-five mortality in rural Bangladesh: evidence from seven national surveys spreading over 20 years. Int. J. Equity Health. 16(1), 197 (2017).

Mazumder, T. et al. An analysis of cause-specific under-5 mortality in Bangladesh using the demographic and health survey 2011 and 2017–2018. BMC Pediatr. 24, 572. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-04979-6 (2024).

Caldwell, J. C. How is greater maternal education translated into lower child mortality?. Health Trans. Rev. 4(2), 224–229 (1994).

Uddin, M. F. et al. Sociodemographic and maternal health-related factors associated with mortality among children under three in Bangladesh: An analysis of data from Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2017–18. BMC Publ. Health 24, 3324. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-20426-8 (2024).

Funding

The authors did not receive any financial support or funding for the conduct of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**Nazmul Haque, Mohammad Anamul Haque** jointly conceived and designed the study, performed statistical analyses, prepared visualizations, and contributed to drafting the full manuscript **. Sheikh Sifat Sadikeen** performed statistical analysis and contributing to drafting the manuscript. **Md. Jamal Uddin** Provided guidance on statistical modelling and analysis and contributed to manuscript refinement.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haque, N., Haque, M.A., Sadikeen, S.S. et al. A hierarchical competing risks survival model in the study of child mortality in Bangladesh. Sci Rep 15, 44812 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28584-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28584-4