Abstract

This study presents the first characterization of a primary cell culture from white skeletal muscle of European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Using immunofluorescence and gene expression analyses over 12 days, cell activation, proliferation, differentiation, fusion, and maturation phases were described. During culture development, myogenic regulatory factors (myf5, myod1, myod2, myog, mrf4) were sequentially expressed. Proliferation peaked at days 4–6, with high Pcna and Myod immunodetection and gene expression of pax7, c-met, and pcna. Early downregulation of cell cycle regulators, cdkn1a and cdkn1cb, and mstnb may have contributed to proliferation, while cdkn1bb progressively increased, likely to promote differentiation. The Gh/Igf axis showed differential regulation, igf-1 decreasing early and igf-2, igf-1ra, igf-1rb, and igfbp-1a gradually rising. Differentiation, myotube formation, and maturation were marked by higher Myhc staining, sarcomere development, and upregulation of cdh15, cav3, mef2, mymk, mymx, myhcb, and wnt4. Anabolic (akt2, mtor, eif4ebp1) and proteolytic-related genes (foxo1a, murf1, mafbx, capn1, capn3b, atg12, map1lc3b) increased in later stages. Comparison with other vertebrates revealed both conserved and species-specific regulatory mechanisms of myogenesis. These findings provide a comprehensive molecular framework of skeletal muscle development in European sea bass and establish a valuable in vitro model for studying fish muscle biology and potential aquaculture and biotechnology applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In teleost fish such as the European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax), white skeletal muscle constitutes most of the body mass and represents the main commercially valuable tissue for the industry. Understanding the mechanisms underlying fish muscle growth and plasticity is therefore essential for enhancing growth performance and optimizing fillet quality. Despite its economic importance, particularly in the Mediterranean region1, knowledge about the molecular pathways governing muscle development and growth in European sea bass remains limited.

Muscle cell cultures offer a powerful in vitro tool to explore the regulation of muscle formation, providing a controlled environment that overcomes the limitations of in vivo studies2. In comparison with cell lines, primary cultures derived directly from muscle tissue better reflect the physiological behavior and responses of muscle cells in their native state3, making them very valuable for investigating the molecular mechanisms regulating muscle development, adaptation, and maintenance with greater accuracy. Therefore, establishing a primary cell culture from European sea bass white muscle-derived cells could substantially enhance our understanding of myogenic processes in this species and pave the way for applications in the aquaculture industry. Indeed, these cultures are highly useful for evaluating the muscle growth-promoting effects or toxicity of different molecules2,4 and compounds5, which can be used to improve fish nutrition with their incorporation into feeds5. Moreover, as recently highlighted by Goswami et al.6, research into the molecular regulation of fish muscle growth is crucial for advancing cultured fish meat production, which is gaining importance as a promising alternative protein source for the future.

Myogenesis in vertebrates, is a complex process orchestrated by the interplay of numerous molecular and cellular mechanisms7,8,9. It begins with the activation of satellite cells [expressing paired box 3 (Pax3) and 7 (Pax7)], which proliferate into myoblasts, differentiate into myocytes, fuse to form multinucleated myotubes, and ultimately mature into functional contractile myofibers (expressing myosin heavy chain, Myhc)10,11. The progression of myogenesis is tightly controlled by the myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs), including the myogenic factor 5 (Myf5) and the myoblast determination protein (Myod), which drive the commitment of satellite cells to the myogenic lineage and their proliferation, as well as the myogenin (Myog) and the myogenic regulatory factor 4 (Mrf4), which regulate terminal cell differentiation and maturation12,13. Moreover, the myoblasts fusion process involves different membrane proteins14, such as cadherins (Cdhs), that mediate cell–cell adhesions15; caveolins (Cavs), involved in vesicular trafficking and signal transduction16; and the recently discovered proteins myomaker (Mymk) and Myomixer (Mymx), implicated in plasma membrane hemifusion and fusion pore formation, respectively17,18.

Beyond the role of the MRFs and the proteins mediating myoblasts fusion, myogenesis is also regulated by a complex network of genes and proteins, including key regulators of cell cycle such as the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (Pcna), the hepatic growth factor receptor (c-Met), or the cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) inhibitors19,20,21. Furthermore, the Wnt signaling pathway is also crucial for the proper progression of myogenesis, since it promotes satellite cell activation and facilitates their transition toward differentiation in mammals22, but its specific functions in fish remain poorly explored. A muscle regeneration study in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) showed an upregulation of wnt5b gene expression following the proteolysis step, coinciding with the initiation of myogenesis23.

The growth hormone/insulin-like growth factors (Gh/Igfs) axis is also important in controlling myogenesis by promoting muscle cell proliferation and differentiation, as clearly demonstrated in mammals24 and fish25. Gh stimulates the production of Igfs, which exert anabolic effects on muscle tissue by binding to Igf-1 receptors (Igf-1r)26, while their availability and activity are finely tuned by Igf-binding proteins (Igfbps)27,28. Igfs trigger a signaling cascade with the kinase Akt is a central component in the regulation of protein synthesis, acting through the kinase mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)29.

Furthermore, the balance between protein synthesis and degradation is crucial for muscle formation and homeostasis maintenance. In vertebrates, muscle proteolysis is primarily mediated by three major intracellular catabolic systems: the ubiquitin–proteasome system, the Ca2+-dependent proteinases (calpains), and the autophagy-lysosome system (cathepsins)30,31,32. In fish, this topic has been extensively investigated in species such as rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)33, Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar)34, gilthead sea bream31,35, and tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus)36, whereas studies on European sea bass remain comparatively limited.

Addressing the gaps in knowledge regarding the regulation of myogenesis in European sea bass, this study establishes and characterizes a primary cell culture derived from the white skeletal muscle of this species. By combining temporal immunofluorescence detection of Pcna, Myod, and Myhc with gene expression profiling of key molecules involved in the cell cycle, signaling pathways, metabolic regulation, and protein turnover, this study aims to elucidate the molecular dynamics underlying the myogenic process in this species. The findings provide valuable insights for both basic research in muscle biology and potential aquaculture and biotechnology applications.

Materials and methods

Primary white muscle cell culture

For the primary muscle cell culture, juveniles of European sea bass (≈ 12 g) were used. Fish were obtained from Piscimar SL (Burriana, Castellón, Spain) and kept in a semi-closed recirculation system at the fish facilities of the Faculty of Biology (University of Barcelona), at 21–23 °C. They were fed ad libitum with a commercial diet (Microbaq M 1.65 mm, Dibaq S.A., Segovia, Spain) and acclimatized for at least 1 week prior to the experiments. Fish were fasted for 24 h before any handling.

The fish were first lightly sedated with MS-222 (Ref. A5040, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and then sacrificed with a sharp blow to the head. Each fish was weighed and then immersed in 70% ethanol for 30 s to sterilize its external surfaces.

Cell isolation was conducted using the protocol from Montserrat et al.37 for gilthead sea bream, with slight modifications. All methodological details are detailed below. Under sterile conditions, white muscle fillets from both sides of the fish were collected and placed in basal medium [Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Ref. D7777), 9 mM NaHCO3 (Ref. S5761), 20 mM HEPES (Ref. H3375), 1.1 g/L NaCl (Ref. S5886)] with 1% (v/v) antibiotic/antimycotic (Ref. A5955), 0.15% (v/v) gentamicin (Ref. G1397), and 15% (v/v) horse serum (Ref. H1270), pH 7.4. Approximately 24 g of tissue (from a pool of approximately 30 fish) was required for each culture, and it was maintained in ice until being chopped into small fragments with sterile blades. The fragments were centrifuged (5 min, 300 g, 4 °C) and the pellet was washed twice with washing medium (basal medium containing 1% antibiotic/antimycotic and 0.15% gentamicin).

Enzymatic digestion was performed with 0.2% (w/v) collagenase type IA (Ref. C9891) in basal medium for 1 h in agitation, at 18 °C, in the dark. The suspension was centrifuged (10 min, 300 g, 4 °C), the pellet was washed twice with washing medium, then centrifuged again (first for 10 min, then for 15 min, both at 300 g, 4 °C). The pellet was resuspended and incubated in basal medium with 0.1% (w/v) trypsin (Ref. T4799) for 20 min in agitation, at 18 °C, in the dark. The suspension was centrifuged (1 min, 300 g, 4 °C), and the supernatant containing the cells was diluted in basal medium containing 1% antibiotic/antimycotic, 0.15% gentamicin, and 15% horse serum to neutralize the trypsin activity. The pellet underwent a second trypsin digestion following the same procedure, and the supernatant was pooled with the previous one. The resulting suspension was centrifuged (20 min, 300 g, 4 °C), and the pellet was resuspended in complete medium [basal medium with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Ref. F7524), and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic]. The suspension was sequentially filtered through 100 μm (Ref. CLS431752) and 40 μm (Ref. CLS431750) cell strainers. Finally, the suspension was centrifuged (20 min, 300 g, 4 °C), the pellet was resuspended in complete medium, and cells were counted and diluted to obtain a concentration of 0.75 × 10⁶ cells/mL.

Cells were plated in 6-well plates for gene expression analyses at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells/well, and in 12-well plates with 18 mm Ø glass coverslips at a density of 0.75 × 106 cells/well for immunofluorescence analyses. Both plates and coverslips were pre-treated with poly-l-lysine (Ref. P6282) and laminin (Ref. L2020) prior to cell plating. For the pre-treatment, a solution of 38.46 μg/mL poly-l-lysine (Ref. P6282) was added to each well, left for 10 min at room temperature, and then removed. The wells were washed twice with sterile Milli-Q water, air-dried, and stored at 4 °C until use. On the day of culture, the plates were treated with a solution of 20 µg/mL laminin and kept at 4 °C for at least 5 h. Before seeding the cells, the laminin solution was removed.

Once plated, cells were incubated at 23 °C and 2.5% CO2, with a full replacement of the culture medium every 2 days. Myoblasts were allowed to develop for 12 days, and their morphology was regularly monitored under an inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Brightfield photos were taken daily from day 1 to day 12 using a Canon EOS 1000D camera.

Extended culture trials were also conducted, in which cells were maintained for more than 30 days with complete medium replacement every 2–3 days. Once the culture reached confluence, a subset of cells continued to proliferate and differentiate, leading to the formation of overlapping cell layers rather than a single monolayer. Samples were not collected at this late stage, as the first 12 days of culture already encompassed the complete sequence of myogenic events in this species. These observations were only used to assess cell longevity and are not presented in the manuscript.

All media, reagents, and cell strainers were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and the culture plates were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

All animal-handling procedures were carried out under the current legislation established by the Council of the European Union (EU 2010/63) and the governments of Spain and Catalonia, and were approved by the Ethics and Animal Care Committee of the University of Barcelona (permit number CEEA OB 296/23).

Immunofluorescence

To carry out immunofluorescence assays, cells on the coverslips were first washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS, Ref. 14190144, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (Ref. P6148, Sigma-Aldrich) in DPBS containing 60 mM sucrose for 20 min at room temperature. Then, cells were permeabilized with 0.05% (w/v) saponin (Ref. S-4521, Sigma-Aldrich) in DPBS with 20 mM glycine (Ref. G8898, Sigma-Aldrich) for 8 min. After two washes with DPBS and 20 mM glycine (washing solution) for 5 min each, cells were blocked with 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA, Ref. A7030, Sigma-Aldrich) in DPBS with 20 mM glycine for 40 min at room temperature. Cells were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-Pcna (1:100 dilution, Ref. sc-56, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany), mouse monoclonal anti-Myod (1:100 dilution, Ref. sc-377460, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or mouse monoclonal anti-Myhc (1:100 dilution; Ref. MF20, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, USA) for 1 h at 37 °C, followed by two washes with washing solution (5 min each) and incubation with Alexa-546-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1500 dilution, Ref. A11003, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h at 37 °C. For nuclei staining, cells were incubated with 0.5 μg/mL DAPI (Ref. d9542, Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min at room temperature, and for F-actin staining, cells were incubated with Phalloidin CruzFluor™ 488 Conjugate (1:2000 dilution, Ref. sc-363791, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 20 min at room temperature. Primary and secondary antibodies, as well as the DAPI and the phalloidin conjugate, were diluted in blocking solution (1% BSA in DPBS with 20 mM glycine) with 0.025% saponin.

For each antibody, three different negative controls were performed: (1) without the primary antibody, to verify that the secondary antibody did not bind non-specifically; (2) without the secondary antibody, to detect any possible autofluorescence or fluorescence derived from the primary antibody itself; and (3) without either antibody, to assess the intrinsic background or autofluorescence of the cells. None of these controls showed any specific fluorescent signal, confirming the specificity and reliability of the immunofluorescence staining.

Cells were mounted with Fluoromount™ Aqueous Mounting Medium (Ref. F4680, Sigma-Aldrich). Images for Pcna, Myod, and Myhc quantification were acquired using an Olympus BX61 microscope (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) connected to an Olympus DP70 camera (Olympus), while high-resolution images for visualization of F-actin bundles were obtained using a confocal microscope. Results were obtained from three independent cultures (N = 3), sampled on days 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. Image processing and quantification of Pcna, Myod, and Myhc (myotube coverage and number of nuclei in Myhc-labeled cells) were done on randomly selected microscopic fields to avoid bias, using ImageJ software (version 1.53f51). Additionally, the Myotube Analyzer software (version 1.0.3)38 was used to quantify the diameter of myotubes. The diameter of the analyzed myotubes was measured multiple times along their length, with at least six measurements taken per myotube.

Gene expression

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

For RNA extraction, cells from six replicate wells were pooled on days 2 and 4 of culture, and cells from three replicate wells were pooled on days 6, 8, 10, and 12. Total RNA was extracted from each pooled sample using 1 mL of TRI Reagent® Solution (Ref. T9424, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA). RNA concentration was quantified using a Nanodrop 2200™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and its integrity was checked with an agarose gel (1%, w/v) stained with SYBR-Safe DNA Gel Stain (Ref. S33102, Invitrogen). Possible DNA present in the samples was digested using the DNase I Amplification Grade (Ref. 18068015, Invitrogen). The cDNA synthesis was performed using 2.2 µg of RNA and the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit® (Ref. 4897030001, Roche, Basel, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

The mRNA transcript levels of genes related to satellite cell activation and proliferation [paired box protein 3b (pax3b), and 7 (pax7), hepatocyte growth factor receptor (c-met), and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (pcna)], genes encoding the MRFs [myogenic factor 5 (myf5), myoblast determination protein 1 (myod1), and 2 (myod2), myogenic regulatory factor 4 (mrf4), and myogenin (myog)], genes involved in cell cycle regulation [(cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1a (cdkn1a), 1ba (cdkn1ba), 1bb (cdkn1bb), and 1cb (cdkn1cb)] and growth inhibition [myostatin b (mstnb)], genes associated with muscle differentiation, fusion and maturation [myod family inhibitor (mdfi), dedicator of cytokinesis protein 5 (dock5), cadherin 15 (cdh15), caveolin 3 (cav3), myomaker (mymk), myomixer (mymx), myocyte enhancer factor 2aa (mef2aa), 2b (mef2b), 2ca (mef2ca), 2cb (mef2cb), and 2d (mef2d)], genes of the Wnt signaling pathway [wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 1 (wnt1), 4 (wnt4), 3a (wnt3a), 5a (wnt5a), 5b (wnt5b), and 7a (wnt7a)], genes of the Gh/Igfs axis [growth hormone receptor 1 (ghr-1) and 2 (ghr-2), insulin-like growth factor 1 (igf-1), and 2 (igf-2), insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor a (igf-1ra) and b (igf-1rb), insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1a (igfbp-1a), 3a (igfbp-3a), 5b (igfbp-5b), and 6b (igfbp-6b)], genes of the Akt/mTor pathway [RAC-alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (akt1), and 2 (akt2), mechanistic target of rapamycin (mtor), regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (rptor), ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta 1b (rps6kb1b), and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (eif4ebp1)], genes related to muscle protein degradation and the autophagic-lysosome system [forkhead box protein O1a (foxo1a), muscle RING-finger protein-1 (murf1), muscle atrophy F-box protein (mafbx), autophagy-related protein 12 (atg12), microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3b (map1lc3b), cathepsin ba (ctsba), d (ctsd), la (ctsla), and l.1 (ctsl.1), calpain 1 (capn1), 2b (capn2b), and 3b (capn3b)], and three reference genes [elongation factor 1-alpha (ef1a), ribosomal protein S30 (fau), and ribosomal protein l17 (rpl17)] were examined in a CFX384™ real-time system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA). The analyses were performed in triplicate in 384-well PCR plates (Ref. HSP3801, Bio-Rad). The amplifications were performed in a 5 μL reaction volume, containing 2 μL of cDNA, 0.25 μL of DEPC-treated water, 2.5 μL of iTaq™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Ref. 1725125, Bio-Rad), and 250 nM (final concentration) of forward and reverse primers (Table S1). The protocol for the reactions was set as follows: an initial activation step of 3 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C, 30 s at the melting temperature of the primers (see Table S1) and fluorescence detection, followed by an amplicon dissociation analysis from 55 to 95 °C. Prior to the analyses, standard curves with a pool of samples were run to verify primer efficiency (90–110%), assess reaction specificity, confirm the absence of primer dimers, and determine the optimal cDNA dilution for each assay. The expression level of each gene was calculated relative to the geometric mean of the two most stable reference genes using the Bio-Rad CFX Manager™ 3.1 software (Bio-Rad). Gene expression analyses were performed in six independent cultures (N = 6).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The normality of the data and the homogeneity of the variances were tested with Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. When the data did not show a normal distribution or homoscedasticity, were transformed by logarithm. Differences among groups were tested by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test. For data that did not accomplish normality, the Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test was used followed by Mann–Whitney U test to determine differences among groups. The confidence interval for all analyses was set at 5%.

Results

Cell culture progression and immunofluorescence analyses

Cells isolated from the white skeletal muscle of European sea bass were cultured for 12 days, and representative daily brightfield images are shown in Fig. S1.

Immunofluorescence staining for Pcna revealed a high proportion of Pcna-positive cells during the proliferative phase, peaking on days 4 and 6 and subsequently decreasing from day 8 onward (Fig. 1A,B). The number of cells estimated by nuclear counting progressively increased as cells proliferated, remaining stable from day 6 onwards (Fig. 1C).

Analysis of cell proliferation throughout the development of primary cells from European sea bass white muscle at days (D) 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 post-seeding. Indirect immunofluorescence detection of Pcna (red), nuclei stained with DAPI (blue), and F-actin with phalloidin (green). (A) Representative images, (B) measurement of Pcna-positive cells (%), and (C) nuclei quantification throughout the culture. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 3 independent cell cultures. Statistical analysis was assessed by one-way ANOVA. Different letters indicate significant differences between days of culture (p < 0.05).

Regarding Myod-expressing cells, over 80% of cells expressed this factor from days 2 to 8, with a decrease to 66% by day 10 and to 33% by day 12 (Fig. 2A,B).

Analysis of Myod expression throughout the development of primary cells from European sea bass white muscle at days (D) 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 post-seeding. Indirect immunofluorescence detection of Myod (red), nuclei stained with DAPI (blue), and F-actin with phalloidin (green). (A) Representative images and (B) measurement of Myod-positive cells (%) throughout the culture. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 3 independent cell cultures. Statistical analysis was assessed by one-way ANOVA. Different letters indicate significant differences between days of culture (p < 0.05).

Myhc staining indicated that myotube formation began between days 2 and 4, since the first Myhc-expressing cells were observed on day 4 (Fig. 3A,B). Myotube coverage, estimated through Myhc detection, gradually increased from day 4, reaching its maximum extent by days 10–12 (Fig. 3B). Similarly, between days 4 and 12, the average myotube diameter increased from approximately 29–94 μm (Fig. 3C), and the percentage of nuclei in Myhc-positive cells rose from about 5% to 63% (Fig. 3D). Dual labeling of Myhc and F-actin revealed that myofiber development began around day 8, as F-actin formed organized patterns and visible striations typical of sarcomere assembly (Fig. 3A). These F-actin bundles measured approximately 1.5 μm, with gaps of 0.5 μm between bundles (Fig. 4).

Analysis of cell differentiation, fusion, and maturation throughout the development of primary cells from European sea bass white muscle at days (D) 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 post-seeding. Indirect immunofluorescence detection of Myhc (red), nuclei stained with DAPI (blue), and F-actin with phalloidin (green). (A) Representative images, (B) myotube coverage (%), (C) myotube diameter (µm), and (D) quantification of nuclei in Myhc labeled cells (%) throughout the culture. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 3 independent cell cultures. Statistical analysis was assessed by one-way ANOVA. Different letters indicate significant differences between days of culture (p < 0.05).

Representative image of indirect immunofluorescence detection of MyHC (red), nuclei (blue), and F-actin (green) on day 12 of a primary cell culture from European sea bass white muscle. (B) and (D) are magnified images of the boxed areas in (A) and (C), respectively. Arrowheads indicate F-actin bundles.

The myogenic identity of the culture was confirmed by the labeling of most cells for Myod and Myhc, and by F-actin staining showing the typical cytoskeletal arrangement and morphology of myogenic cells.

Transcriptional regulation of myogenesis in vitro

The genes associated with satellite cell activation and proliferation control, pax3b exhibited high expression levels at the beginning of the culture, followed by a gradual decrease over the days (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the expression of pax7 and c-met was low on day 2, increased by day 4, and progressively declined during the subsequent days of culture (Fig. 5B,C). The proliferation marker pcna showed maximum expression on days 2 and 4, with a drastic decrease from day 6 onward (Fig. 5D).

Relative expression of genes related to satellite cell activation and control of proliferation throughout the development of primary cells from European sea bass white muscle. Expression of (A) pax3b, (B) pax7, (C) c-met, and (D) pcna on days (D) 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 6 independent cell cultures. Statistical analysis was assessed by one-way ANOVA. Different letters indicate significant differences between days of culture (p < 0.05).

Concerning the MRFs, myf5 expression was low on day 2, increased by day 4, and showed a slight but non-significant decline in the later stages of the culture (Fig. 6A). The transcriptional profiles of both myod paralogs differed, since myod1 exhibited high expression on day 2, followed by a decline throughout the culture period, whereas myod2 displayed low initial levels and rose to a peak on day 8 before decreasing again (Fig. 6B,C). In contrast, myog and mrf4 maintained low expression during the early culture days, with both reaching maximum levels on day 10 (Fig. 6D,E).

Relative gene expression of myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs) throughout the development of primary cells from European sea bass white muscle. Expression of (A) myf5, (B) myod1, (C) myod2, (D) myog, and (E) mrf4 on days (D) 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 6 independent cell cultures. Statistical analysis was assessed by one-way ANOVA. Different letters indicate significant differences between days of culture (p < 0.05).

The four cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors studied exhibited distinct transcriptional patterns. Both cdkn1a and cdkn1cb presented the highest expression on day 2 and dropped sharply on day 4, remaining at minimal levels thereafter (Fig. 7A,D). Conversely, cdkn1ba showed no significant variations throughout the culture period (Fig. 7B), whereas cdkn1bb displayed a gradual increase in expression over the days (Fig. 7C). Moreover, the growth inhibitor mstnb exhibited a similar pattern to that of cdkn1a and cdkn1cb, with its highest expression on day 2, a sharp drop by day 4, and minimal levels thereafter (Fig. 7E).

Relative gene expression of cell cycle and growth inhibitors throughout the development of primary cells from European sea bass white muscle. Expression of (A) cdkn1a, (B) cdkn1ba, (C) cdkn1bb, (D) cdkn1cb, and (E) mstnb on days (D) 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 6 independent cell cultures. Statistical analysis was assessed by one-way ANOVA. Different letters indicate significant differences between days of culture (p < 0.05).

With respect to regulators of muscle differentiation, fusion, and maturation, all the genes analyzed (mdfi, dock5, cdh15, cav3, mef2aa, mef2ca, mef2cb, mef2d, mymk, mymx, and myhcb) presented a progressively increasing expression as the culture developed (Fig. 8A–K). Among them, mdfi and dock5 showed a linear increase throughout the culture (Fig. 8A,B). In contrast, all other genes reached their peak transcription levels on day 10, followed by a subsequent decline (Fig. 8C–K).

Relative gene expression of regulators of muscle differentiation, fusion, and maturation throughout the development of primary cells from European sea bass white muscle. Expression of (A) mdfi, (B) dock5, (C) cdh15, (D) cav3, (E) mef2aa, (F) mef2ca, (G) mef2cb, (H) mef2d, (I) mymk, (J) mymx, and (K) myhcb on days (D) 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 6 independent cell cultures. Statistical analysis was assessed by one-way ANOVA. Different letters indicate significant differences between days of culture (p < 0.05).

The Wnt gene family displayed varied expression patterns across the culture period. While wnt1 presented stable transcription levels throughout the culture (Fig. 9A), wnt4 increased its expression during the later stages (Fig. 9B). Meanwhile, wnt5a and wnt5b initially showed low expression, reached a maximum on day 8, and then experienced a slight but not-significant decline thereafter (Fig. 9C,D).

Relative expression of genes of the Wnt signaling pathway throughout the development of primary cells from European sea bass white muscle. Expression of (A) wnt1, (B) wnt4, (C) wnt5a, and (D) wnt5b on days (D) 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 6 independent cell cultures. Statistical analysis was assessed by one-way ANOVA. Different letters indicate significant differences between days of culture (p < 0.05).

Regarding the relative expression of genes of the Gh/Igf axis, ghr1 and ghr2 exhibited distinct patterns over the culture period. While ghr1 exhibited no significant differences (Fig. 10A), ghr2 was expressed at low levels on day 2 and increased to a peak on day 6 (Fig. 10B). The expression of igf-1 was highest on day 2 but dropped sharply by day 4, remaining at minimal levels thereafter (Fig. 10C). In contrast, igf-2 displayed a progressive increase throughout the culture period (Fig. 10D). Similarly, both igf-1ra and igf-1rb steadily increased from the beginning of the culture and maintained this trend over time (Fig. 10E,F). With respect to the binding proteins, igfbp-1a showed a steady increase from the beginning of the culture, reaching maximum levels between days 8 and 12 (Fig. 10G), while igfbp-3a exhibited stable expression throughout the culture period (Fig. 10H). The expression of igfbp-5b reached its maximum on day 2, followed by a sharp decline starting from day 4 (Fig. 10I), and igfbp-6b displayed a peak on day 4, with low expression levels observed on the other days (Fig. 10J).

Relative expression of genes of the Gh/Igf axis throughout the development of primary cells from European sea bass white muscle. Expression of (A) ghr-1, (B) ghr-2, (C) igf-1, (D) igf-2, (E) igf-1ra, (F) igf-1rb, (G) igfbp-1a, (H) igfbp-3a, (I) igfbp-5b, and (J) igfbp-6b on days (D) 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 6 independent cell cultures. Statistical analysis was assessed by one-way ANOVA. Different letters indicate significant differences between days of culture (p < 0.05).

The expression analysis of genes involved in anabolic signaling and energy regulation revealed that akt2, mtor, and eif4ebp1 followed a similar pattern during the culture period, progressively increasing from the start of the culture to the later stages (Fig. 11B,C,F). In contrast, the expression of akt1, rptor, and rps6kb1b remained relatively stable throughout the culture period, showing no significant fluctuations (Fig. 11A,D,E).

Relative expression of genes related to anabolic signaling in the Akt/mTor pathway throughout the development of primary cells from European sea bass white muscle. Expression of (A) akt1, (B) akt2, (C) mtor, (D) rptor, (E) rps6kb1b, and (F) eif4ebp1 on days (D) 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 6 independent cell cultures. Statistical analysis was assessed by one-way ANOVA. Different letters indicate significant differences between days of culture (p < 0.05).

Relative expression of genes related to muscle protein degradation and autophagic-lysosome system throughout the development of primary cells from European sea bass white muscle. Expression of (A) foxo1a, (B) murf1, (C) mafbx, (D) atg12, (E) map1lc3b, (F) ctsba, (G) ctsd, (H) ctsla, (I) ctsl.1, (J) capn1, (K) capn2b, and (L) capn3b on days (D) 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 6 independent cell cultures. Statistical analysis was assessed by one-way ANOVA. Different letters indicate significant differences between days of culture (p < 0.05).

Most genes associated with protein degradation pathways (foxo1a, murf1, mafbx, capn1, capn3b) and the autophagic-lysosome system (atg12, map1lc3b) exhibited low mRNA levels at the beginning of the culture and increased as the culture progressed (Fig. 12A–E,J,L). Conversely, ctsd and ctsl.1 displayed an inverse pattern, with high expression at the onset of the culture followed by a gradual decrease over time (Fig. 12G,I), whereas ctsba, ctsla, and capn2b showed no significant differences (Fig. 12F,H,K).

Discussion

Understanding the regulation of muscle growth and development in fish is essential for both basic biological research and advancements in aquaculture production. While primary cultures of white skeletal muscle cells have been established in several teleost species to study myogenesis in vitro37,39,40,41,42, no such culture has yet been developed for European sea bass. Thus, we established a primary myogenic culture in this species and employed immunofluorescence and gene expression analyses to characterize the temporal profile of key molecular regulators involved in muscle formation.

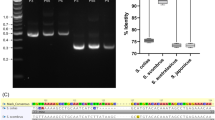

The European sea bass exhibits indeterminate growth, maintaining a high proportion of quiescent and proliferative satellite cells even in adulthood, driving postembryonic mosaic hyperplasia43. The mitotic potential of satellite cells isolated from white muscle in this species has been demonstrated in the present study by their ability to proliferate and increase in number progressively throughout the culture. Proliferation peaked between days 4 and 6, with around 80% Pcna-positive cells, although some cells maintained Pcna expression at later stages (about 30% on day 12). This pattern aligned with pcna gene expression, which peaked on days 2 and 4, preceding the increase of Pcna immunodetection, and then gradually decreased. Compared to the primary culture of white muscle cells from gilthead sea bream, a closely related marine species, European sea bass showed a comparable proliferative capacity13,37. However, compared to rainbow trout44, cells derived from European sea bass of similar size (5–10 g) exhibited a higher proliferative capacity. Both species showed approximately 30% proliferative cells on day 2, but in rainbow trout, this increased to 50% by day 4 and dropped to 10% by day 744, while European sea bass increased the proportion of proliferative cells to 80% on days 4 and 6. These differences may be influenced by culture temperature, being 18 °C in rainbow trout and 23 °C in European sea bass.

Moreover, at the onset of culture, the gene expression of key upstream regulators of myogenesis, such as pax3b and pax745, exhibited high levels and decreased steadily throughout the culture. These transcription factors play a fundamental role in guiding progenitor cells into the myogenic program and in regulating their survival, proliferation, and migration in other teleosts, primarily by activating members of the MRFs family, Myf5 and Myod1, as well as the receptor for hepatocyte growth factor, c-Met46,47,48. Our findings are consistent with this, showing elevated myf5, myod1, and c-met gene expression on days 2 and/or 4 of culture, with subsequent downregulation as the culture progressed.

In line with these findings, the early high immunodetection of Myod, with more than 80% of Myod-positive cells already present by day 2 of culture, may suggest that most isolated satellite cells were quickly activated and committed to the myogenic lineage. The sustained high detection of Myod from day 2 to day 8 aligns with previous results in gilthead sea bream13, and in zebrafish (Danio rerio)46, in which similar immunostaining patterns were reported on these days. Although immunofluorescence data on later days in these species is lacking for comparison, the observed reduction in Myod detection in European sea bass on days 10–12 follows a common trend during myofiber maturation in mammals49.

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors are key regulators of cell cycle progression50, but their involvement in fish myogenesis has received little attention. During the in vitro myogenesis of European sea bass, cdkn1a (p21), cdkn1ba, cdkn1bb (both paralogs of p27), and cdkn1cb (p57) exhibited distinct expression patterns, which would propose different regulatory roles in cell cycle control. Both cdkn1a and cdkn1cb exhibited a sharp decline from day 2 to day 4, followed by consistently low expression levels until day 12, suggesting an early role in regulating cell cycle arrest and a subsequent decrease as differentiation progresses. In mouse, Cdkn1a has been shown to be upregulated by Mstn, contributing to the negative regulation of the G1 to S shift and the maintenance of satellite cells in a quiescent state51. These results would explain the observed similar expression profiles of cdkn1a and mstnb in European sea bass in vitro myogenesis, indicating a potential positive regulatory relationship between these two molecules. In contrast, cdkn1ba maintained relatively stable expression throughout the culture period and cdkn1bb exhibited a progressive increase, peaking at days 10–12. Thus, cdkn1bb could be the paralog that might play a more prominent role in European sea bass, potentially contributing to the later stages of differentiation and the stabilization of the post-mitotic state. Taken together, these results reveal that, although acting at different time points, these cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors converge in downregulating the cell cycle, as reflected by their low expression at day 4, coinciding with the highest proliferative activity.

As myogenesis advanced, the MRFs involved in terminal differentiation, such as myod2, myog, and mrf4, were upregulated. myod2 peaked on day 8 of culture, whereas myog and mrf4 reached their highest expression on day 10 before subsequently decreasing. Myod2 and Myod1, paralogs of Myod in fish, play distinct yet complementary roles in myogenesis, with myod2 typically expressed after myod118. This temporal pattern suggests a role for myod2 in the transition from myoblasts to differentiated myotubes, which aligns with the present findings. Meanwhile, Myog and Mrf4 are essential for late differentiation and myotube maturation, driving the expression of genes that establish muscle fiber identity and function12. In this line, in previous studies with gilthead sea bream muscle cell culture, myod2, myog, and mrf4 peaked earlier than in European sea bass, at days 6, 8, and 9 of culture, respectively13,18. The slightly faster progression observed in gilthead sea bream compared to European sea bass could be a characteristic trait of this species, or it may be influenced by the initial cell seeding density, as those studies utilized seeding densities up to 25% higher than those used in our European sea bass experiments13,18. Higher seeding densities can enhance cell–cell interactions and promote earlier myogenic differentiation, potentially accelerating the overall development of muscle cells in culture.

The role of the Myod family inhibitor (Mdfi) in fish myogenesis remains unexplored, and its function in mammals is still debated. In pig muscle satellite cells, MDFI has been shown to enhance proliferation while suppressing differentiation52. Conversely, studies on the C2C12 mouse myoblast cell line have reported that MDFI facilitates differentiation by upregulating MYOD, MYOG, and Myosin53. In European sea bass, the gradual increase in mdfi expression, in parallel with myog and myhcb, would support a similar role, regulating the transition from proliferation to differentiation and myotube maturation.

Several markers associated with later stages of muscle development in vertebrates, including dock5, cdh15, cav3, mymk, mymx, mef2aa, mef2ca, mef2cb, and mef2d exhibited a progressive increase in transcription in the European sea bass culture, peaking on days 10 or 12. This peak coincided with active myoblast fusion to form myotubes, a process involving migration, elongation, cell–cell contact formation, recognition, and final myoblast membrane fusion (reviewed in Lehka and Rędowicz14). Cell migration depends on cytoskeletal remodeling, in which Dock5 plays a critical role, as demonstrated in zebrafish54. The parallel increase in dock5 transcription and F-actin bundle formation in European sea bass culture further supports its involvement in cytoskeletal dynamics. Various membrane proteins are involved in cell–cell contact formation and recognition, including Cdh15 and Cav3, which remain poorly studied in fish55 compared to mammals14,15. However, their expression profiles during in vitro myogenesis in European sea bass point to a comparable function in facilitating cell–cell interactions during myoblast fusion. mymk and mymx also exhibited maximum transcription levels during active myotube formation, aligning with previous findings demonstrating their essential and complementary roles in the membrane fusion of founder and donor myoblasts in fish18,56,57,58. Regarding mef2 genes, six have been identified in teleost fish (mef2aa, mef2ab, mef2b, mef2ca, mef2cb, and mef2d)59, with all but mef2ab annotated in European sea bass. In the present study, all five annotated genes were detected, although mef2b exhibited markedly lower expression (data not shown), according to the absence of mRNA detection in zebrafish somitic muscle during early larval development60. All other mef2 genes showed a similar pattern, with the highest transcription during terminal differentiation and maturation, consistent with their well-conserved function in vertebrates59,61.

Both myhcb gene expression and Myhc immunostaining also confirmed the proper progression of the cell culture, steadily increasing throughout the culture. The first Myhc-positive cells were observed on day 4, marking the beginning of myocyte fusion into polynucleated myotubes, and peaked on days 10–12 of culture. Additionally, the diameter and nuclear content of myotubes and myofibers increased over time, reaching their highest levels by days 10–12, demonstrating the contribution of satellite cells to fiber hypertrophy. Dual labeling of Myhc and F-actin confirmed that myofiber maturation began around day 8, as F-actin started forming organized patterns and visible striations characteristic of sarcomere assembly, ensuring that the cultured cells were properly developing into functional muscle tissue. All these results are in agreement with the Myhc expression profile in vertebrate myogenesis13,62.

Given the importance of Wnt signaling in embryonic development, morphogenesis22, and muscle formation and regeneration in vertebrates63,64, the transcriptional dynamics of pathway members were analyzed during in vitro myogenesis. All analyzed Wnt genes were detected, but only wnt1, wnt4, wnt5a, and wnt5b showed reliable expression, while wnt3a, wnt10b, and wnt7a displayed minimal transcriptional activity (data not shown), pointing toward a limited role in this in vitro model. The stable expression of wnt1 suggests a role in maintaining baseline myogenic regulation rather than driving significant changes. Conversely, increased wnt4 expression supports its involvement in myoblast fusion, as was observed in C2C12 and primary mouse satellite cells, in which Wnt4 enhanced differentiation and hypertrophic myotube growth through Mstn suppression65,66, and aligns with the inverse relationship between wnt4 and mstnb expression in our model. On the other hand, wnt5a exhibited maximum expression levels at days 2 and 8, indicating involvement in both early signaling and later differentiation, in agreement with its function in activating key myogenic regulators (Myf5, MyoD, Myog) and Myhc67,68. Meanwhile, the single peak of wnt5b at day 8 proposes a more restricted role in terminal differentiation and myoblast fusion, as also suggested by Otero-Tarrazón et al.23 in a muscle regeneration experiment in gilthead sea bream. Overall, these findings support stage-specific roles of Wnt signaling in myogenesis and highlight the importance of studying this pathway in other teleosts to reveal species-specific adaptations in muscle formation and regeneration.

The Gh/Igf axis, a key regulator of muscle growth in vertebrates24, has been widely documented in various fish species25,69,70,71, and few studies have examined its function in European sea bass72,73,74. In this species, in vitro myogenesis showed distinct temporal expression of Gh/Igf-related genes. The stable expression of ghr1 might reflect a continuous but non-dynamic role, while the transient upregulation of ghr2 at day 6 suggests a more prominent function during the mid-stage of differentiation. The differential expression of these two paralogs may reflect distinct regulatory functions, as described in gilthead sea bream75,76,77 and other fish species70,78,79.

Concerning Igfs, igf-1 showed an early peak at day 2, followed by a sharp decline, whereas igf-2 pattern was opposite, with a progressive increase throughout the culture, which would indicate a sequential participation in myogenesis regulation in this species. Interestingly, despite the evolutionary conservation of Igfs, their transcription dynamics during myogenesis appear to vary across species. In teleosts such as gilthead sea bream, rainbow trout, and salmon, both igf-1 and igf-2 are more expressed early in culture and decrease over time, consistent with the mitogenic effects of exogenous Igfs in these species44,80,81,82,83,84. In contrast, mice and humans show increasing IGF-1 and IGF-2 gene expression during myogenesis85,86, with exogenous IGF-1 promoting early myogenic commitment and IGF-2 driving terminal differentiation87. Moreover, we observed that igf-2 exhibited markedly higher average expression levels than igf-1 throughout the culture (log2FC ≈ 6, data not shown), resembling the differences in expression levels in muscle of these factors reported in chicken88, and highlighting their main respective roles as autocrine/paracrine (Igf-2) and endocrine (Igf-1) regulators. Taken together, further studies are needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying the differential regulation of these two growth factors during European sea bass myogenesis compared to other species, and ongoing research in our group is currently addressing this question.

The transcription of both Igf-1 receptors, igf-1ra and igf-1rb, steadily increased throughout the culture. These results match the observed rise in Igf-1rs number and specific binding in parallel with muscle cells differentiation in gilthead sea bream37 and rainbow trout primary cultures89. Furthermore, it is consistent with the delayed myogenic differentiation in C2C12 cells with Igf-1rs inactivation90, and enhanced differentiation in the C2-LISN mouse myoblasts line overexpressing these receptors91.

Similarly, the progressive increase of igfbp-1a, peaking between days 8 and 12, suggests a role in modulating Igf activity during late differentiation and myotube maturation, which might be in line with the negative role attributed to Igfbp-1 in teleost growth27. In contrast, igfbp-3a presented relatively stable expression, while igfbp-5b peaked early at day 2 before declining, pointing to a role in early development, as seen in Atlantic salmon in which it stimulates satellite cells activation83. The transient peak of igfbp-6b at day 4 may point to a regulatory function in the transition from proliferation to differentiation. Thus, the distinct expression patterns of Igfbps throughout myogenesis highlight their potential roles in fine-tuning myogenesis regulation.

Regarding the key components of the anabolic Akt/mTor pathway, the expression of akt2, mtor, and eif4ebp1 progressively increased, whereas akt1, rptor, and rps6kb1b remained relatively stable throughout the culture. The continuous presence of akt1 transcripts agrees with its function in early myogenic proliferation and differentiation92,93 and with its constant levels throughout the culture of the C2 mouse myoblast cell line94. Conversely, Akt2 appears to have a more important role in later stages, during myotube maturation and myofiber formation92,93,94, which could explain its gradual upregulation. Similarly, the progressive increase of mtor, a central regulator of protein synthesis and cell growth95,96,97, also highlights the enhanced anabolic activity required during myotube and myofiber development. The expression of rptor, a scaffold protein of the mTORC1 complex, was possibly maintained in the European sea bass culture to preserve mTORC1 integrity and baseline function during myogenesis. Regarding downstream effectors, the stable gene expression of rps6kb1b, which encodes the ribosomal S6 kinase 1 involved in protein translation, may be due to its regulation predominantly occurring at the post-translational level, rather than through transcriptional changes98. In contrast, eif4ebp1, an inhibitor of cap-dependent translation29,95, was progressively upregulated, perhaps reflecting the need for fine-tuning translation rates during the transition from proliferation to differentiation. All these findings indicate a coordinated transcriptional regulation of key growth and translation pathways during European sea bass myogenesis, emphasizing the critical role of the Akt/mTor pathway in fish muscle development, as reported in species such as gilthead sea bream99, rainbow trout100, or fine flounder (Paralichthys adspersus)101.

Finally, during myogenesis, the precise regulation of protein synthesis and degradation is crucial for proper cellular progression, with proteolytic systems being key in maintaining this balance. Thus, the expression of lysosomal proteases ctsd and ctsl.1 showed higher expression at the beginning of the culture and decreased over time, in agreement with the role of cathepsins in early differentiation during in vitro myogenesis already reported in fish31. In contrast, the lack of significant fluctuations in the expression of ctsba, ctsla, as well as capn2b proposes a more constitutive role in proteolytic regulation, independent of the myogenic stage. On the other hand, transcripts encoding components of the ubiquitin–proteasome system, including foxo1a, murf1, and mafbx, as well as calpains capn1 and capn3b, progressively increased throughout the culture. This pattern agrees with their known roles in muscle remodeling and protein turnover during differentiation102,103, as well as with the increase of murf1 and mafbx during the in vitro development of gilthead sea bream myocytes found by Vélez et al.31. Similarly, genes associated with the autophagy-lysosome pathway, such as atg12 and map1lc3b, were also gradually upregulated, which may support their involvement in organelle recycling and energy homeostasis during myotube maturation33,104,105.

In summary, this study has established and characterized a primary white muscle cell culture in European sea bass for the first time, integrating immunofluorescence and transcriptional analyses to provide a detailed overview of myogenesis regulation. The findings highlight how various molecular pathways are coordinated throughout myogenesis (Fig. 13), including several molecules previously unknown or poorly described in fish, revealing both conserved and species-specific regulatory dynamics. Although further work will help to better understand the precise roles of some of these molecules in fish, the panel of stage-specific markers presented here offers a valuable tool for evaluating myogenic development, with relevance for both basic muscle biology and applied aquaculture research.

Schematic representation of the development of a primary cell culture derived from white skeletal muscle of European sea bass, alongside the gene expression profile of key regulators involved in cell cycle progression, signaling pathways, metabolic regulation, and protein turnover. The diagram illustrates the sequential stages of myogenesis, from isolated satellite cells through myoblasts, myocytes, and myotubes, culminating in mature myofibers. The timeline highlights major cellular processes during myogenesis, including activation and proliferation, differentiation, fusion, and maturation.

Data availability

All relevant data are within the paper and the Supplementary material files.

References

APROMAR. La Acuicultura en España (2024).

Vélez, E. J. et al. Contribution of in vitro myocytes studies to understanding fish muscle physiology. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 199, 67–73 (2016).

Baydoun, A. R. Cell culture technique. In Principles and Techniques of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (eds Wilson, K. & Walker, J.) 38–72 (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Duran, B. O. S. et al. Amino acids and IGF1 regulation of fish muscle growth revealed by transcriptome and microRNAome integrative analyses of pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus) Myotubes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 1180 (2022).

Sánchez-Moya, A. et al. Cysteamine improves growth and the GH/IGF axis in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata): In vivo and in vitro approaches. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1211470 (2023).

Goswami, M. et al. Cellular aquaculture: Prospects and challenges. Micromachines 13, 828 (2022).

Johnston, I. A., Bower, N. I. & Macqueen, D. J. Growth and the regulation of myotomal muscle mass in teleost fish. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 1617–1628 (2011).

Rossi, G. & Messina, G. Comparative myogenesis in teleosts and mammals. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 3081–3099 (2014).

Millan-Cubillo, A. F. et al. Proteomic characterization of primary cultured myocytes in a fish model at different myogenesis stages. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–16 (2019).

Bentzinger, C. F., Wang, Y. X. & Rudnicki, M. A. Building muscle: Molecular regulation of myogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a008342 (2012).

Chal, J. & Pourquié, O. Making muscle: Skeletal myogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Development 144, 2104–2122 (2017).

Asfour, H. A., Allouh, M. Z. & Said, R. S. Myogenic regulatory factors: The orchestrators of myogenesis after 30 years of discovery. Exp. Biol. Med. 243, 118–128 (2018).

Garcia de la serrana, D. et al. Characterisation and expression of myogenesis regulatory factors during in vitro myoblast development and in vivo fasting in the gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 167, 90–99 (2014).

Lehka, L. & Rędowicz, M. J. Mechanisms regulating myoblast fusion: A multilevel interplay. Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol. 104, 81–92 (2020).

Maître, J. L. & Heisenberg, C. P. Three functions of cadherins in cell adhesion. Curr. Biol. 23, R626 (2013).

Pfannkuche, K. (ed.) Cell Fusion: Overviews and Methods 2nd edn. (Springer, 2015).

Leikina, E. et al. Myomaker and myomerger work independently to control distinct steps of membrane remodeling during myoblast fusion. Dev. Cell 46, 767-780.e7 (2018).

Perelló-Amorós, M. et al. Myomaker and myomixer characterization in gilthead sea bream under different myogenesis conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 14639 (2022).

Gal-Levi, R., Leshem, Y., Aoki, S., Nakamura, T. & Halevy, O. Hepatocyte growth factor plays a dual role in regulating skeletal muscle satellite cell proliferation and differentiation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 1402, 39–51 (1998).

Campbell, C. A. et al. p65 signaling dynamics drive the developmental progression of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells through cell cycle regulation. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–22 (2024).

Johnson, S. E. & Allen, R. E. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) is expressed in activated rat skeletal muscle satellite cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 154, 39–43 (1993).

Qin, K. et al. Canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling: Multilayered mediators, signaling mechanisms and major signaling crosstalk. Genes Dis. 11, 103–134 (2024).

Otero-Tarrazón, A. et al. Muscle regeneration in gilthead sea bream: Implications of endocrine and local regulatory factors and the crosstalk with bone. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1101356 (2023).

Velloso, C. P. Regulation of muscle mass by growth hormone and IGF-I. Br. J. Pharmacol. 154, 557–568 (2008).

Fuentes, E. N., Valdés, J. A., Molina, A. & Björnsson, B. T. Regulation of skeletal muscle growth in fish by the growth hormone—Insulin-like growth factor system. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 192, 136–148 (2013).

Duan, C., Ren, H. & Gao, S. Insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), IGF receptors, and IGF-binding proteins: Roles in skeletal muscle growth and differentiation. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 167, 344–351 (2010).

Garcia de la serrana, D. & Macqueen, D. J. Insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins of teleost fishes. Front. Endocrinol. 9, 1–12 (2018).

Kelley, K. M., Haigwood, J. T., Perez, M. & Galima, M. M. Serum insulin-like growth factor binding proteins (IGFBPs) as markers for anabolic/catabolic condition in fishes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 129, 229–236 (2001).

Schiaffino, S. & Mammucari, C. Regulation of skeletal muscle growth by the IGF1-Akt/PKB pathway: Insights from genetic models. Skelet. Muscle 1, 1–14 (2011).

Salmerón, C., Navarro, I., Johnston, I. A., Gutiérrez, J. & Capilla, E. Characterisation and expression analysis of cathepsins and ubiquitin-proteasome genes in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) skeletal muscle. BMC Res. Notes 8, 1–15 (2015).

Vélez, E. J. et al. Proteolytic systems’ expression during myogenesis and transcriptional regulation by amino acids in gilthead sea bream cultured muscle cells. PLoS ONE 12, 1–21 (2017).

Jackman, R. W. & Kandarian, S. C. The molecular basis of skeletal muscle atrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287, C834–C843 (2004).

Seiliez, I., Dias, K. & Cleveland, B. M. Contribution of the autophagy-lysosomal and ubiquitin-proteasomal proteolytic systems to total proteolysis in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) myotubes. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 307, R1330–R1337 (2014).

Bower, N. I., de la Serrana, D. G. & Johnston, I. A. Characterisation and differential regulation of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 α and β transcripts in skeletal muscle of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 396, 265–271 (2010).

Salmerón, C. et al. Characterisation and expression of calpain family members in relation to nutritional status, diet composition and flesh texture in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). PLoS ONE 8, e75349 (2013).

Shaalan, W., El-Hameid, N. A. A., El-Serafy, S. S. & Salem, M. Molecular characterization and expression of calpains and cathepsins in tilapia muscle in response to starvation. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 23, 21895 (2023).

Montserrat, N., Sánchez-Gurmaches, J., García De La Serrana, D., Navarro, M. I. & Gutiérrez, J. IGF-I binding and receptor signal transduction in primary cell culture of muscle cells of gilthead sea bream: Changes throughout in vitro development. Cell Tissue Res. 330, 503–513 (2007).

Noë, S. et al. The myotube analyzer: How to assess myogenic features in muscle stem cells. Skelet. Muscle 12, 1–12 (2022).

Koumans, J. T. M., Akster, H. A., Dulos, G. J. & Osse, J. W. M. Myosatellite cells of Cyprinus carpio (Teleostei) in vitro: Isolation, recognition and differentiation. Cell Tissue Res. 261, 173–181 (1990).

Powell, R. L., Dodson, M. V. & Cloud, J. G. Cultivation and differentiation of satellite cells from skeletal muscle of the rainbow trout Salmo gairdneri. J. Exp. Zool. 250, 333–338 (1989).

Rescan, P.-Y., Paboeuf, G. & Fauconneau, B. Myosatellite cells of Oncorhynchus mykiss: culture and myogenesis on laminin substrates. In Biology of Protozoa Invertebrates and Fishes: In Vitro Experimental Models and Applications (Eds. IFREMER), vol. 18, 63–68 (1995).

Sepich, D. S., Ho, R. K. & Westerfield, M. Autonomous expression of the nic1 acetylcholine receptor mutation in zebrafish muscle cells. Dev. Biol. 161, 84–90 (1994).

Mommsen, T. P. Paradigms of growth in fish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 129, 207–219 (2001).

Gabillard, J. C., Sabin, N. & Paboeuf, G. In vitro characterization of proliferation and differentiation of trout satellite cells. Cell Tissue Res. 342, 471–477 (2010).

Buckingham, M. & Relaix, F. PAX3 and PAX7 as upstream regulators of myogenesis. Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol. 44, 115–125 (2015).

Froehlich, J. M., Galt, N. J., Charging, M. J., Meyer, B. M. & Biga, P. R. In vitro indeterminate teleost myogenesis appears to be dependent on Pax3. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 49, 371–385 (2013).

Relaix, F. et al. Pax3 and Pax7 have distinct and overlapping functions in adult muscle progenitor cells. J. Cell Biol. 172, 91–102 (2006).

Jiao, S., Tan, X., You, F. & Pang, Q. Multiple isoforms of olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) Pax3a and Pax3b display differential regulations on myogenic differentiation. J. Ocean Univ. China 21, 1295–1306 (2022).

Schmidt, M., Schüler, S. C., Hüttner, S. S., von Eyss, B. & von Maltzahn, J. Adult stem cells at work: Regenerating skeletal muscle. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 76, 2559–2570 (2019).

Besson, A., Dowdy, S. F. & Roberts, J. M. CDK inhibitors: Cell cycle regulators and beyond. Dev. Cell. 14, 159–169 (2008).

McCroskery, S., Thomas, M., Maxwell, L., Sharma, M. & Kambadur, R. Myostatin negatively regulates satellite cell activation and self-renewal. J. Cell Biol. 162, 1135–1147 (2003).

Hou, L. et al. MiR-27b promotes muscle development by inhibiting MDFI expression. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 46, 2271–2283 (2018).

Huang, B. et al. Mdfi promotes C2C12 cell differentiation and positively modulates fast-to-slow-twitch muscle fiber transformation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 605875 (2021).

Moore, C. A., Parkin, C. A., Bidet, Y. & Ingham, P. W. A role for the Myoblast city homologues Dock1 and Dock5 and the adaptor proteins Crk and Crk-like in zebrafish myoblast fusion. Development 134, 3145–3153 (2007).

Chong, S. W., Korzh, V. & Jiang, Y. J. Myogenesis and molecules—Insights from zebrafish Danio rerio. J. Fish Biol. 74, 1693–1755 (2009).

Landemaine, A., Rescan, P. Y. & Gabillard, J. C. Myomaker mediates fusion of fast myocytes in zebrafish embryos. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 451, 480–484 (2014).

Zeng, W. et al. The regulatory role of myomaker in the muscle growth of the Chinese perch (Siniperca chuatsi). Animals 14, 2448 (2024).

Perello-Amoros, M., Rallière, C., Gutiérrez, J. & Gabillard, J. C. Myomixer is expressed during embryonic and post-larval hyperplasia, muscle regeneration and differentiation of myoblats in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Gene 790, 145688 (2021).

Taylor, M. V. & Hughes, S. M. Mef2 and the skeletal muscle differentiation program. Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol. 72, 33–44 (2017).

Yogev, O., Williams, V. C., Hinits, Y. & Hughes, S. M. eIF4EBP3L acts as a gatekeeper of TORC1 in activity-dependent muscle growth by specifically regulating Mef2ca translational initiation. PLOS Biol. 11, e1001679 (2013).

Hinits, Y. & Hughes, S. M. Mef2s are required for thick filament formation in nascent muscle fibres. Development 134, 2511–2519 (2007).

Perruchot, M. H., Ecolan, P., Sorensen, I. L., Oksbjerg, N. & Lefaucheur, L. In vitro characterization of proliferation and differentiation of pig satellite cells. Differentiation 84, 322–329 (2012).

von Maltzahn, J., Chang, N. C., Bentzinger, C. F. & Rudnicki, M. A. Wnt signaling in myogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 602–609 (2012).

Girardi, F. & Le Grand, F. Wnt signaling in skeletal muscle development and regeneration. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 153, 157–179 (2018).

Bernardi, H. et al. Wnt4 activates the canonical β-catenin pathway and regulates negatively myostatin: Functional implication in myogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 300, 1122–1138 (2011).

Fedon, Y. et al. Role and function of Wnts in the regulation of myogenesis: When Wnt meets myostatin. In Skeletal Muscle—From Myogenesis to Clinical Relations (ed. Cseri, J.) (IntechOpen, 2012).

Tajbakhsh, S. et al. Differential activation of Myf5 and MyoD by different Wnts in explants of mouse paraxial mesoderm and the later activation of myogenesis in the absence of Myf5. Development 125, 4155–4162 (1998).

Wang, M. et al. Curcumin-activated Wnt5a pathway mediates Ca2+ channel opening to affect myoblast differentiation and skeletal muscle regeneration. J. Cachexia. Sarcopenia Muscle 15, 1834–1849 (2024).

Company, R., Astola, A., Pendón, C., Valdivia, M. M. & Pérez-Sánchez, J. Somatotropic regulation of fish growth and adiposity: Growth hormone (GH) and somatolactin (SL) relationship. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 130, 435–445 (2001).

Reindl, K. M. & Sheridan, M. A. Peripheral regulation of the growth hormone-insulin-like growth factor system in fish and other vertebrates. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 163, 231–245 (2012).

Reinecke, M. et al. Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factors in fish: Where we are and where to go. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 142, 20–24 (2005).

Enes, P., Sanchez-Gurmaches, J., Navarro, I., Gutiérrez, J. & Oliva-Teles, A. Role of insulin and IGF-I on the regulation of glucose metabolism in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) fed with different dietary carbohydrate levels. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 157, 346–353 (2010).

Terova, G. et al. Cloning and expression analysis of insulin-like growth factor I and II in liver and muscle of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax, L.) during long-term fasting and refeeding. J. Fish Biol. 70, 219–233 (2007).

De Celis, S. V. R., Gómez-Requeni, P. & Pérez-Sánchez, J. Production and characterization of recombinantly derived peptides and antibodies for accurate determinations of somatolactin, growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 139, 266–277 (2004).

Saera-Vila, A., Calduch-Giner, J. A. & Pérez-Sánchez, J. Duplication of growth hormone receptor (GHR) in fish genome: Gene organization and transcriptional regulation of GHR type I and II in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 142, 193–203 (2005).

Vélez, E. J. et al. Effects of sustained exercise on GH-IGFs axis in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 310, R313–R322 (2016).

Lavajoo, F. et al. Regulatory mechanisms involved in muscle and bone remodeling during refeeding in gilthead sea bream. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–14 (2020).

Kittilson, J. D., Jones, E. & Sheridan, M. A. ERK, Akt, and STAT5 are differentially activated by the two growth hormone receptor subtypes of a teleost fish (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Front. Endocrinol. 2, 12056 (2011).

Reid, R. M., Turkmen, S., Cleveland, B. M. & Biga, P. R. Direct actions of growth hormone in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, skeletal muscle cells in vitro. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 297, 111725 (2024).

Jiménez-Amilburu, V. et al. Insulin-like growth factors effects on the expression of myogenic regulatory factors in gilthead sea bream muscle cells. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 188, 151–158 (2013).

Castillo, J., Codina, M., Martínez, M. L., Navarro, I. & Gutiérrez, J. Metabolic and mitogenic effects of IGF-I and insulin on muscle cells of rainbow trout. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 286, 935–941 (2004).

Codina, M. et al. Metabolic and mitogenic effects of IGF-II in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) myocytes in culture and the role of IGF-II in the PI3K/Akt and MAPK signalling pathways. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 157, 116–124 (2008).

Rius-Francino, M. et al. Differential effects on proliferation of GH and IGFs in sea bream (Sparus aurata) cultured myocytes. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 172, 44–49 (2011).

Bower, N. I. & Johnston, I. A. Transcriptional regulation of the IGF signaling pathway by amino acids and insulin-like growth factors during myogenesis in Atlantic salmon. PLoS ONE 5, e11100 (2010).

Jiao, S. et al. Differential regulation of IGF-I and IGF-II gene expression in skeletal muscle cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 373, 107–113 (2013).

Yan, Z. et al. Highly coordinated gene regulation in mouse skeletal muscle regeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8826–8836 (2003).

Aboalola, D. & Han, V. K. M. Different effects of insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin-like growth factor-2 on myogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 8286248 (2017).

Kocamis, H., McFarland, D. C. & Killefer, J. Temporal expression of growth factor genes during myogenesis of satellite cells derived from the biceps femoris and pectoralis major muscles of the chicken. J. Cell. Physiol. 186, 146–152 (2001).

Castillo, J. et al. IGF-I binding in primary culture of muscle cells of rainbow trout: Changes during in vitro development. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 283, R647–R652 (2002).

Cheng, Z. Q. et al. Functional inactivation of the IGF-I receptor delays differentiation of skeletal muscle cells. J. Endocrinol. 167, 175–182 (2000).

Quinn, L. S., Steinmetz, B., Maas, A., Ong, L. & Kaleko, M. Type-1 insulin-like growth factor receptor overexpression produces dual effects on myoblast proliferation and differentiation. J. Cell. Physiol. 159, 387–398 (1994).

Héron-Milhavet, L. et al. Only Akt1 is required for proliferation, while Akt2 promotes cell cycle exit through p21 binding. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 8267–8280 (2006).

Gardner, S., Anguiano, M. & Rotwein, P. Defining Akt actions in muscle differentiation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 303, 1292–1300 (2012).

Rotwein, P. & Wilson, E. M. Distinct actions of Akt1 and Akt2 in skeletal muscle differentiation. J. Cell. Physiol. 219, 503–511 (2009).

Bodine, S. C. et al. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 1014–1019 (2001).

Glass, D. J. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy signaling pathways. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 37, 1974–1984 (2005).

Glaviano, A. et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies in cancer. Mol. Cancer. 22, 1–37 (2023).

Fenton, T. R. & Gout, I. T. Functions and regulation of the 70 kDa ribosomal S6 kinases. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 43, 47–59 (2011).

Vélez, E. J. et al. IGF-I and amino acids effects through TOR signaling on proliferation and differentiation of gilthead sea bream cultured myocytes. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 205, 296–304 (2014).

Seiliez, I. et al. An in vivo and in vitro assessment of TOR signaling cascade in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 295, 329–335 (2008).

Fuentes, E. N. et al. IGF-I/PI3K/Akt and IGF-I/MAPK/ERK pathways in vivo in skeletal muscle are regulated by nutrition and contribute to somatic growth in the fine flounder. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 300, R1532–R1542 (2011).

Liang, Y. C., Yeh, J. Y., Forsberg, N. E. & Ou, B. R. Involvement of μ- and m-calpains and protein kinase C isoforms in L8 myoblast differentiation. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 38, 662–670 (2006).

Goll, D. E., Thompson, V. F., Li, H., Wei, W. & Cong, J. The calpain system. Physiol. Rev. 83, 731–801 (2003).

Zhou, Z. et al. Autophagy regulation in teleost fish: A double-edged sword. Aquaculture 558, 738369 (2022).

Fortini, P. et al. The fine tuning of metabolism, autophagy and differentiation during in vitro myogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 7, e2168 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the personnel from the facilities at the Faculty of Biology (Universitat de Barcelona) for the maintenance of the fish.

Funding

This work was supported by the projects with references RTI2018-100757-B-I00 (MICIU/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033 and “ERDF A way of making Europe”), PID2023-149563OB-I00 (MICIU/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033 and “ERDF/EU”), and PID2020-116172RB-I00 (MICIU/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033). I.G.-P. and I.R. received support through predoctoral fellowships with reference numbers PRE2019-089578 (MICIU/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033 and “ESF Investing in your future”) and PRE2021-100391 (MICIU/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033 and “ESF+”), respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: I.G.-P. and J.G.; methodology: I.G.-P.; validation: I.G.-P.; formal analysis: I.G.-P. and A.R.; investigation: I.G.-P., I.R., C.D.-S., and A.R.; writing—original draft: I.G.-P.; writing—review and editing: I.G.-P., J.G., I.R., J.B., E.C., I.N., and A.R.; visualization: I.G.-P.; supervision: J.G.; project administration: J.G. and J.B.; funding acquisition: J.G., J.B, E.C., and I.N. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

All animal-handling procedures were carried out under the current legislation established by the Council of the European Union (EU 2010/63) and the governments of Spain and Catalonia, and were approved by the Ethics and Animal Care Committee of the University of Barcelona (permit number CEEA OB 296/23). The experiments were also conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

García-Pérez, I., Rodríguez, I., Rubio, A. et al. Characterization of myogenesis in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) using primary white muscle cell cultures. Sci Rep 15, 45778 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28654-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28654-7