Abstract

This paper proposes a novel multiplicative logistic map derived from the rule of multiplicative calculus and introduces an additional parametric freedom that fundamentally extends its dynamical capabilities. The theoretical and numerical analysis confirm that this map undergoes a period-doubling bifurcation cascade into chaos as rigorously validated by stability analysis, bifurcation diagrams, transversality conditions and stability conditions. Crucially, compared to the classical logistic map, it exhibits a significantly broader chaotic region and an expanded output range beyond [0,1]. Cobweb and time-series plots visually confirm these enhanced and complex behaviors. Moreover, owing to its greater parametric flexibility and wider chaotic dynamics, the multiplicative logistic map is a highly suitable candidate for advanced encryption applications. Experimental results and comparative analysis demonstrate that the image encryption algorithm based on the proposed map exhibits strong resistance to statistical attacks and superior parameter robustness in practical implementations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chaos is a phenomenon which is difficult to predict if it manifests itself in a nonlinear system. Such systems appear in some continuous forms, as well as discrete forms. The classical mathematical model of discrete chaotic systems is the logistic map which is constructed to capture the essence of processes observed in nature. Logistic map is interesting not only for its simple form but also from a mathematical perspective: nonlinear models can behave in chaotic and complicated ways.

The conventional logistic map was initially popularized in a paper by the biologist Robert May1 in 1976, analogous to the logistic equation first created by Verhulst2. It is a famous iterative map that gains attention for simulating the evolution of insect populations under limited resource constraints and revealing the astonishing process from stability, bifurcation to chaos, as follows.

where \({x_n} \in [0,1]\) represents the population ratio at generation \(n\) and \(r\) is the intrinsic growth rate which is restricted to the interval (0,4]. The bifurcation diagram shown in Fig. 1 is a basic characteristic of the logistic map which represents that the system will enter chaos through period-doubling bifurcation as parameter is varied. A more detailed mathematical analysis of logistic map and its applications were extensively discussed in the literature3.

Since the introduction of the classical logistic map, various generalized versions have been proposed and exhibited different dynamic characteristics. The early research on the generalization of the logistic map mainly focused on nonlinear form extension. Marotto4 proposed a generalized model based on logistic map to exhibit an interesting property of biological populations, namely the threshold phenomena. At extremely low levels many populations tend to lead to extinction rather than to growth. However, beyond some threshold the population will tend to grow in a manner similar to that predicted by the logistic equation. The model is considered as

Blumberg5 introduced a modification of the logistic growth equation to model population dynamics or organ size evolution which is defined as

Radwan6 and Rocha7,8,9 also proposed a class of generalized logistic maps with arbitrary powers.

In summary, the generalizations of the logistic map mentioned above can be unified into the following form

These generalized logistic maps exhibit various dynamical behaviors similar to the traditional logistic map such as Hopf bifurcation and chaos.

In addition, there are other examples of nonlinear generalizations of logistic map, such as exponential logistic map which is applicable for single species population regulated with an epidemic disease at high density as follows1

Hassell10 provided a more flexible framework with negative exponential powers as follows

This generalized logistic model describes a population with a propensity to simple exponential growth at low densities. Empirically, it is plausible for a single species population which is regulated by an epidemic disease at high density.

Subsequent research on the generalization of the logistic map turned to complex dynamics, such as fractional order logistic11,12,13,14, delayed logistic15,16, modulated logistic17,18,19, and coupled logistic20,21,22.

The traditional logistic map and its various modified or expanded versions are highly rich in information and indications which constitute an important part of the fundamental research on chaos theory such as stability analysis, bifurcation patterns and Lyapunov exponents. However, not only do modified versions of classical logistic map need to be investigated, but new methods should also be developed to generalize novel chaotic systems.

The multiplicative logistic map

Aniszewska and Rybaczuk23 presented a modified version of the classical Lorenz system. The new system was constructed during the study of the behaviors of dynamical systems described with multiplicative calculus24. The reason for employing multiplicative calculus is that in the case of dynamical systems depending on the shifts of fractal dimensions, it is impossible to define the derivative quotient in the classical derivative of a function.

There is a relationship between the classical derivative and the multiplicative derivative for function \(f(x)\) as follows

where \(f^{\prime}(x)\) is a classical additive derivative of \(f(x)\) with respect to \(x\) and \(\frac{{\pi f(x)}}{{\pi x}}\) is the multiplicative derivative defined as

From Eqs. (7) and (8), we know that the essence of the relationship between the classical derivative and the multiplicative derivative is logarithmic transformation. Therefore, to explore chaos in multiplicative systems, the transition rules from classical additive calculus to multiplicative calculus involves replacing addition by multiplication

and multiplication by raising to suitable power

By using this rule to process classical logistic map (1), we can obtain a multiplicative logistic map

where \(\ln r\) has been replaced by \(r\).

Aniszewska25 quantitatively analyzed the chaotic behaviors of (9) by the study of bifurcation diagrams and Lyapunov exponents. As shown in Fig. 2, the multiplicative logistic map exhibits a period-doubling route to chaos. However, comparing Figs. 1 and 2, we can see that the structures of the two bifurcation diagrams are very similar in the interval (0,4], except for the difference in the scale of the vertical coordinate \({x_n}\).

In fact, taking the logarithm on both sides of Eq. (9) yields

Letting \(y_{n} = \ln x_{n}\) and replacing \(\ln r\) by \(r\), we obtain

Therefore, after taking the logarithm on the vertical coordinate in Fig. 2, we can see that the multiplicative logistic map (9) exhibits the same bifurcation diagrams as the classical additive logistic map (1) when \(r \in (0,4]\). Of course, the transition from (1) to (9) is not unique. For example, classical logistic map can also be transformed into another form

However, by taking the logarithm of both sides of the equation and setting \({y_n}=\ln {x_n}\), we still obtain Eq. (11).

From the above comparisons, it can be seen that if the transition from classical calculation to multiplicative calculation fully follows the rules of addition being replaced by multiplication and multiplication being replaced by suitable power, the resulting new map will have a completely similar bifurcation structure to the original map. However, if the transition rules are only partially applied, does the obtained generalized discrete logistic map have different chaotic dynamical behaviors?

To increase the flexibility of parameters, we first rewrite the logistic map (1) as

Letting \({r_1}{\text{=}}\alpha\) and \({r_2}=r\), we have

As previously mentioned, the transition from the classical logistic map to the multiplicative logistic map is achieved by replacing addition with multiplication and multiplication with suitable power operations. If this rule is only partially applied, a new multiplicative logistic map is postulated as follows, where \(\alpha {x_n}\) is kept unchanged and \(r\left( {1 - {x_n}} \right)\) is replaced by \({r^{1 - {x_n}}}\) in Eq. (14).

Note that map (15) can reduce to several well-known models under specific parameter choices. In particular, when we set \(\alpha {\text{=}}1\) and replace \(r\) with \({e^r}\), (15) reduces to the exponential logistic map (5). Similarly, when we set \(r=e\) and \(\alpha e{\text{=}}\alpha\) it reduces to the famous Ricker model26. This new multiplicative logistic map represents a generalized and more universal framework for modeling population dynamics. It elegantly unifies several classical models by subsuming them as special cases under specific parameter constraints. The parameter flexibility allows it to capture a wider range of biological complexities and become a powerful tool for studying nonlinear population behaviors.

Chaos of the new multiplicative logistic map

Stability analysis of fixed points

Theoretically, the fixed point can be obtained from the following equation for fixed parameters \(\alpha\) and

Obviously, there are a trivial fixed points \({x_1}=0\) and a nontrivial fixed point \({x_2}=1+{{\ln \alpha } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\ln \alpha } {\ln r}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\ln r}}\) for all values of the parameters satisfying \(\alpha r \ne 1\).

To analyze the stability of the fixed points, we compute the derivative of

For the trivial fixed point \({x_1}\), we have \({f_x}\left( {{x_1},\alpha ,r} \right)=\alpha r\). So, the trivial fixed point is stable when \(\alpha r<1\) and unstable when \(\alpha r>1\).

For the nontrivial fixed point \({x_2}\), we have \({f_x}\left( {{x_2},\alpha ,r} \right)=1 - \ln r - \ln \alpha\). So, when \(1<\alpha r<{e^2}\) the fixed point is stable and when \(\alpha r<1\) or \(\alpha r>{e^2}\) the fixed point is unstable.

Exploration and verification of period-doubling bifurcation

In dynamical systems, a point \(x^{*}\) is called a period-n point of the function \(f(x)\) if \({f^n}\left( {{x^{\text{*}}}} \right)={x^{\text{*}}}\) and \({f^k}\left( {{x^*}} \right) \ne {x^*}\) for any positive integer \(k<n\), where \({f^n}(x)\) denotes the n-th iterate of \(f(x)\). As a special case, a point \({x^*}\) that satisfies \(f(x)=x\) is called a fixed point or period-1 point. To explore the period-doubling bifurcation in system (15), we present a schematic analysis by plotting the functions \(f(x)\), \({f^2}(x)\), and \({f^4}(x)\) for different values of parameters \(r\) at \(\alpha {\text{=}}2\) as shown in Fig. 3.

When \(r{\text{ }} = {\text{ }}2.5{\text{ }}\), it can be seen that the new multiplicative logistic map exhibits simple dynamical behaviors characterized by two fixed points \({x_1}=0\) and \({x_2}=1+{{\ln \alpha } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\ln \alpha } {\ln r}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\ln r}}\) in Fig. 3a. The intersection of \(y=f(x)\) with the line \(y=x\) identifies these equilibrium states. However, as the parameter \(r\) exceeds the first critical value \(r_{c}^{1}={{{e^2}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{e^2}} \alpha }} \right. \kern-0pt} \alpha }\), the nontrivial fixed point \({x_2}\) loses its stability as \(\left| {{f_x}\left( {{x_2},\alpha ,r} \right)} \right|>1\). Consequently, the first period-doubling bifurcation unfolds and it is visualized by analyzing the second iterate \(y={f^2}(x)\) at \(r=5\). As shown in Fig. 3b, two new stable period-2 points \({x_3}\) and \({x_4}\) emerge near the fixed point \({x_2}\), visible as new intersections of \(y={f^2}(x)\) with the line \(y=x\) and characterized by a slope of \({f^2}(x)\) whose absolute value is less than 1. This bifurcation signifies the system’s departure from simple fixed-point behavior towards a period-2 orbit, marking the onset of period-doubling route to chaos. In Fig. 3c, with a further increase in the parameter to \(r{\text{=}}7\), the system undergoes a second period-doubling bifurcation. The previously stable period-2 points \({x_3}\) and \({x_4}\) becomes unstable. This instability is mirrored in the graph of \({f^2}(x)\), where the absolute value of slope at the points \({x_3}\) and \({x_4}\) now exceeds the stability threshold. The fourth iterate \(y={f^4}(x)\) reveals the birth of four new stable period-4 points \({x_5}\), \({x_6}\), \({x_7}\) and \({x_8}\), forming a stable period-4 orbit. This cascade from a fixed point to a 2-cycle and then to a 4-cycle is a hallmark of the Feigenbaum scenario. The visualization of this second bifurcation in our model strongly indicates its capability to reproduce universal features of nonlinear dynamics.

In summary, this series of figures not only visually guides the reader through the initial stages of the period-doubling cascade but also underscores a key novel aspect of our proposed map: the explicit dependence of the critical bifurcation parameter \(r_{c}^{1}\) on the multiplicative parameter \(\alpha\). This differentiates its dynamical landscape from the classical logistic map and provides a richer parameter space for controlling the transition to chaos.

Next, we will further verify that the new multiplicative logistic map enters chaos through a period-doubling bifurcation cascade.

The eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix of a dynamical system reflect the rate of change in different directions, and an eigenvalue of \(- 1\) means that in some directions the rate of change is opposite to its current state, which may cause changes in the periodic behaviors of the system. In brief, when the eigenvalue of the Jacobian matrix is \(- 1\), the system may experience period-doubling bifurcation.

At the critical parameter value \(r_{c}^{1}={{{e^2}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{e^2}} \alpha }} \right. \kern-0pt} \alpha }\) for fixed \(\alpha\), the nontrivial fixed point satisfies \({f_x}\left( {{x_2},\alpha ,r_{c}^{1}} \right)=1 - \ln r_{c}^{1} - \ln \alpha = - 1\). According to Theorem 3.5.1 in reference27, if the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix are \(- 1\) at a fixed point and the transversality condition and stability condition are satisfied, the system will experience period-doubling bifurcation.

Firstly, the transversality condition for system (15) can be calculated as follows

Therefore, the system will first experience period-doubling bifurcation at the critical value \(r_{c}^{1}{\text{=}}{{{e^2}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{e^2}} \alpha }} \right. \kern-0pt} \alpha }\).

The transversality condition ensures that the system eigenvalues cross the unit circle at a non-zero rate as parameters vary, thereby avoiding the degradation of bifurcations.

Secondly, the stability condition for system (15) is verified at the critical value \(r_{c}^{1}\) as follows

Then \(\beta \ne 0\) means a change in the stability of the fixed point at \(\left( {{x_2},r_{c}^{1}} \right)\) and the occurrence of a period-doubling bifurcation. Moreover, the sign of \(\beta\) determines the stability and direction of bifurcation of the period-2 orbits.

Therefore, the nontrivial fixed point \({x_2}=1+{{\ln \alpha } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\ln \alpha } {\ln r}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\ln r}}\) bifurcates at \(r_{c}^{1}={{{e^2}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{e^2}} 2}} \right. \kern-0pt} 2}=3.6945\) when \(\alpha = 2\). As \(r\) continues to increase, the eigenvalues of Jacobian matrix for period-2 points reach \(- 1\) again, and the period-2 points bifurcate into a period-4 points, and so on, forming an infinite cascade of period-doubling bifurcation sequences.

In the same vein, when the parameter \(r\) is fixed, the above condition can also be verified. For the critical value \(\alpha _{c}^{1}{\text{=}}{{{e^2}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{e^2}} r}} \right. \kern-0pt} r}{\text{=}}4.9260\) at \(r{\text{=}}1.5\), the nontrivial fixed point satisfies \({f_x}\left( {{x_2},\alpha _{c}^{1},r} \right)=1 - \ln r - \ln \alpha _{c}^{1}= - 1\).

The transversality condition and the stability condition for system (15) are calculated as follows

Therefore, the system will first experience period-doubling bifurcation at the critical value \(\alpha _{c}^{1}{\text{=}}{{{e^2}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{e^2}} r}} \right. \kern-0pt} r}\).

Bifurcation diagrams and Lyapunov exponents

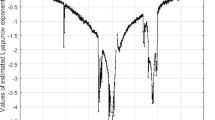

To further discuss the chaotic characteristics for the new multiplicative logistic map, the overall dynamic behaviors of this map are illustrated in Fig. 4 by means of the bifurcation diagrams and the corresponding Lyapunov exponent spectrums. As follows, all numerical computations are performed in MATLAB R2023b.

Bifurcation diagram exhibits some characteristic property of the asymptotic solution of a dynamical system as a function of a control parameter, and allow one to see briefly where the qualitative change occurs in the asymptotic solution. Correspondingly, The Lyapunov exponent measures the exponential divergence rate of adjacent trajectories in dynamical systems and serves as a key quantitative indicator to analyze chaotic motion. Usually, a positive Lyapunov exponent means exponential separation of adjacent orbits and therefore a chaotic indicator, while a negative exponent indicates normal and periodic system behavior28.

The Lyapunov exponent for a system \({x_{n+1}}=f\left( {{x_n}} \right)\) with an initial value \({x_0}\) can be defined as29

In Fig.4a, bifurcation diagram and Lyapunov exponent with respect to parameter \(r\) are presented to analyze the chaotic dynamical behaviors of the system. Macroscopically, both the bifurcation diagram and the Lyapunov exponents reveal the same dynamical behaviors of the system. In particular, the presence of positive Lyapunov exponents is consistent with the chaotic region. More detailed analysis is listed as follows.

When \(r \in (1,3.6945)\), the point \({x_2}=1+{{\ln \alpha } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\ln \alpha } {\ln r}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\ln r}}\) is a stable fixed point of the system and all system orbits will converge towards \({x_2}\) from any initial value of \({x_0}\). As crosses the first critical value \(r_{c}^{1}{\text{=}}{{{e^2}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{e^2}} 2}} \right. \kern-0pt} 2}{\text{=}}3.6945\), the fixed point \({x_2}\) loses its stability and the first period-doubling bifurcation occurs, resulting in two new stable period-2 points. When \(r \in (3.6945,6.2453)\), the system behaves as a stable period-2 orbit. As the parameter \(r\) increases beyond the second critical value \(r_{c}^{2}{\text{=}}6.2453\), the two stable period-2 points become unstable and the second period-doubling bifurcation occurs, which typically results in the emergence of four period-4 points. With a further increase of the parameter \(r\) , a cascade of new period doublings occurs, yielding period-4 bifurcation, period-8 bifurcation, and so on. Consequently, the orbits become chaotic, whereby the attractor evolves from a finite to an infinite set of points.

A similar bifurcation structure is observed for parameter \(\alpha\) in Fig. 4c, the system also undergoes a series of period-doubling bifurcations into chaos from a fixed point to period-2 points, period-4 points, and so on. However, compared to the bifurcation diagram for parameter \(r\) in Fig. 4a, the diagram in Fig. 4c exhibits narrower periodic windows embedded in the chaotic region and a significantly broader output range of the chaotic sequences.

A notable feature in Fig. 4a is that the chaotic region is interrupted by a period-3 window, which is clearly visible in both the bifurcation diagram and the Lyapunov exponent spectrum. For clearer visualization, a magnified view of this window is provided in Fig. 4b. The presence of periodic windows indicates that the route to chaos in the new multiplicative logistic map evolutes via a pattern of intermittency, which is characterized by alternating bursts of order and chaos. These phenomena include all sudden destruction or creations of chaotic attractors may result from the collision of an unstable periodic orbit and a coexisting chaotic attractor, which is called chaos crisis30. In the field of secure communication31, the integration of this feature into a semiconductor chaotic encryption chip enables dynamic carrier frequency modulation via intermittent chaotic signals, and enhances interception resistance in hardware-level secure communication.

In our calculations, the dynamical behavior of the new multiplicative logistic map is verified through numerical calculations of the bifurcation diagram and the Lyapunov exponents. The analysis confirms the existence of period-doubling cascades leading to chaos. As expected, this period-doubling evolutionary process is consistent with the results shown in Fig. 3.

Recently, chaos-based encryption algorithm32,33,34 has attracted significant research attention. Compared to the classical logistic map and its generalizations, the proposed new multiplicative logistic map exhibits significantly broader chaotic intervals across both parameters as shown in Table 1, thereby indicating potentially enhanced randomness and stronger resistance to cryptographic attacks35. Moreover, as highlighted by Alvarez36 and Kocarev37, a secure chaos-based cryptosystem requires a large key space to effectively resist brute-force attacks. The introduction of two parameters in Eq. (15) effectively expands the parametric freedom of the new multiplicative logistic map and significantly increases the potential key space for any encryption scheme built upon our map.

More significantly in the current context, the enhanced dimensionality not only allows for richer bifurcation scenarios and broader regimes of chaotic behavior but also facilitates the identification of transitions between order and chaos in a two-dimensional parameter space. In what follows, we systematically examine the global dynamics of the system across this extended parameter plane.

To visualize the global dynamics of the new multiplicative logistic map, the heat map of the largest Lyapunov exponent in terms of the parameter \(\alpha\) and \(r\) is obtained and displayed using the 2D and 3D plots in Fig. 5. In these figures, the parameter space \((\alpha ,r)\) is delineated using a color scheme in which non-chaotic regions with a non-positive Lyapunov exponent are marked in black, whereas chaotic regions with a positive exponent are shown in green.

The structure of the Lyapunov exponent heat map in Fig. 5a reveals a complex interplay between order and chaos across the \((\alpha ,r)\) parameter plane. Extensive black regions dominate for lower values of \(\alpha\) and \(r\) signifying regular dynamics where the system converges to stable fixed points or periodic orbits. As either parameter increases, the system transitions from non-chaotic to chaotic states gradually, with the Lyapunov exponent heat map shifting from black to green patterns. This transition often follows period-doubling bifurcations, visible as layered or branching structures near the edges of chaotic zones. Within the broad green chaotic regions, narrow black bands are observed, representing periodic windows where high-period orbits stabilize temporarily before chaos reemerges.

Furthermore, the overall geometry of the Lyapunov exponent spectrum in Fig. 5a and b exhibits a fractal or self-organized structure, as characterized by its multiscale self-similarity embed in the two-dimensional parameter space, which is absent in the classical one-parameter logistic map. The presence of these fractal patterns is a hallmark of unimodal maps and illustrates the underlying complexity of the system’s dynamics. This intricate structure makes it exceedingly challenging, if not impossible, to derive closed formulas that precisely delineate the chaotic regions from the non-chaotic regions. Nevertheless, inspired by the hyperbolic shape of the interspersed black non-chaotic regions, and noting that the critical parameters during the system’s first period-doubling bifurcation satisfy \(\alpha r={e^2}\), we believe that this observation may offer a promising starting point for tackling this problem.

The 3D visualization in Fig. 5c further enriches the interpretation by depicting the Lyapunov exponent as an elevated surface on which chaotic regions appear as ridges or plateaus rising above the zero-exponent plane. This perspective emphasizes how chaos emerges and intensifies with parameter variations, while the 2D heat map provides a clear topological overview of both chaotic and regular domains. These plots together demonstrate that the new map exhibits rich nonlinear dynamical phenomena, including stable equilibria, period-doubling routes to chaos, and periodic windows.

Cobweb diagrams and time-series plots

To further study the route of the new multiplicative logistic map to chaos, Figs. 6 and 7 provide complementary insights into the system’s dynamical evolution: a geometric perspective from the cobweb plots and a view of its temporal evolution from the time series with parameter \(\alpha =2\) and initial value \({x_0}=1.5\).

In Fig. 6a for \(r=3\), the system converges to a stable fixed point. This is visually confirmed by the cobweb trajectory spiraling inward and ultimately contracting to a single point. As shown by the corresponding time series in Fig. 7a, the state variable rapidly converges to a constant value.

As the parameter increases to \(r=5\) in Fig. 6b, the system undergoes its first period-doubling bifurcation. The previously stable fixed point loses its stability and gives rise to a stable period-2 orbit. The evolutionary process is clearly depicted in the cobweb plot as oscillations between two distinct values, as corroborated by the corresponding time series in Fig. 7b, which displays a regular and sustained alternation between two levels.

The result of the second period-doubling bifurcation is shown in Fig. 7c for \(r=7\). Here, the period-2 orbit becomes unstable, and the system settles into a period-4 orbit. The cobweb diagram evolves into a more complex, yet still orderly, closed structure involving four distinct points. This sequential doubling from period-2 to period-4 is a classic signature of the period-doubling bifurcation route to chaos, and the corresponding time series in Fig. 7c confirms the iteration through four distinct values.

Finally, at \(r=9\) in Fig. 6d, the system exhibits unambiguous chaotic behavior. Correspondingly, the time series in Fig. 7d shows aperiodic and unpredictable motion without any convergence to a periodic orbit. Furthermore, a significant novel contribution is the expanded dynamical range of the output sequence. Unlike the classical logistic map whose chaotic orbit is typically confined to a narrower range, the orbit of this new multiplicative map traces an intricate, non-repeating pattern and almost fills the entire output rectangle. This expanded range is not merely a quantitative change but provides greater flexibility for practical applications. It directly helps mitigate quantization errors and statistical biases inherent in digital implementations of chaotic systems with limited value ranges. This enhanced capability makes the proposed map particularly suitable for a broader spectrum of applications, including quantitative financial modeling, pathological diagnosis and weather forecasting.

Performance metrics analysis in image encryption

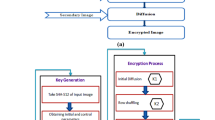

In this section, we evaluate the performance of the proposed multiplicative logistic map for image encryption. Its effectiveness is quantified by measuring the randomness of the encrypted images using several metrics: histogram analysis, correlation analysis, and information entropy.

In the following experiments, we employ an image encryption algorithm proposed by Elghandour39. The algorithm consists of confusion and diffusion processes, both of which are based on chaotic maps. For the diffusion process, the original two-dimensional piecewise smooth nonlinear chaotic map is replaced with the multiplicative logistic map with parameter values \(r=1.5\) and \(\alpha =17\). A 512 × 512 Peppers image is utilized to evaluate the encryption algorithm.

An image histogram depicts the distribution of image pixels by plotting the number of pixels at each gray level. The redundancy of original images should be hidden in the distribution of encrypted images which logically need to be uniform. In encryption practices, the closer the distribution of the encrypted data is to a uniform distribution, the higher the level of security it provides. From the simulation results shown in Fig. 8, the corresponding encrypted image shows up to be so noisy such that any data from them cannot be gotten. Moreover, the histogram of encrypted image exhibits a perfectly uniform distribution, so that it is enough to makes statistic attacks infeasible.

An effective image cryptosystem must ensure that the correlation between adjacent pixels in the encrypted image is sufficiently minimized to resist statistical attacks. This requirement arises from the fact that original images typically exhibit strong intrinsic correlations among adjacent pixels. Therefore, to enhance security against statistical analysis, a well-designed encryption scheme should produce encrypted images with negligible dependence between adjacent pixels. The degree of association between adjacent pixels can be quantitatively evaluated using the correlation coefficients, which provide a rigorous measure of linear dependence between adjacent pixels. The correlation values can be calculated by the following Eq.

where

and

In this study, we evaluate the performance of the proposed chaotic encryption algorithm based on the multiplicative logistic map by computing and comparing the correlation coefficients of adjacent pixels in both the original and encrypted images. Specifically, this involves measuring the correlation in three distinct directional relationships: horizontally adjacent pixels, vertically adjacent pixels, and diagonally adjacent pixels. As can be seen from Fig. 9, the correlation coefficients of the original images are close to 1, while the correlation coefficients of encrypted images are close to 0. So, the original images have strong correlations for the adjacent pixels, while the encrypted images have hardly any correlations for the adjacent pixels. These demonstrate that the encryption scheme based our proposed multiplicative map can protects the images against statistical attacks.

The entropy is a perfect feature to measure the degree of unpredictability and randomness. Hence, the security of an encryption algorithm can be evaluated by calculating the information entropy of the encrypted image. A higher information entropy, especially one closer to the theoretical maximum value of 8, indicates a more secure algorithm. The entropy of a gray image can be computed as

where \(p(i)\) represents the probability of gray value \(i\).

To further investigate the superiority of the encryption algorithm based on the multiplicative logistic map, we replace the chaotic map in the diffusion process with the classical logistic map and exponential logistic map respectively, and execute the same encryption procedure. In Table 2, the information entropy of the encrypted images obtained using these three maps is presented for comparison.

It can be seen from Table 2, all three chaotic maps demonstrate excellent encryption performance in the diffusion process with the entropy values of encrypted images approaching the theoretical optimum of 8. The multiplicative logistic map exhibits the best parameter stability and performance consistency across a wide parameter range, while both the classical logistic map and exponential logistic map require specific parameter values to achieve optimal performance. These results indicate that the proposed multiplicative logistic map offers superior parameter robustness in image encryption applications and provides greater flexibility in parameter selection for practical implementations.

Conclusions

In summary, this study presents a comprehensive chaotic dynamical analysis of a novel multiplicative logistic map. A key innovation of this new map is its foundation in multiplicative calculus, endowing it with an extra parameter for enhanced flexibility. The theoretical and numerical analysis confirm that this map undergoes a period-doubling bifurcation cascade into chaos as rigorously validated by bifurcation diagrams, transversality conditions, and stability conditions. The most significant findings for the system are its enlarged chaotic region and expanded range of output values as visualized in the bifurcation diagram, Lyapunov exponent and cobweb plots.

These properties of multi-parameter freedom and rich dynamic behaviors are not just theoretical improvements but constitute a primary advantage of the new map. They enable the generation of more complex and unpredictable sequences, thereby offering a significantly more powerful tool for applications in various fields such as image encryption. Experimental results and comparative analysis demonstrate that the image encryption algorithm based on the multiplicative logistic map exhibits strong resistance to statistical attacks and superior parameter robustness in practical implementations.

Data availability

This manuscript has no associated data and the data that support the results are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

May, R. M. Simple mathematical models with very complicated dynamics. Nature 261 (5560), 459–467 (1976).

VerhulstP F Notice Sur La Loi Que La population suit Dans son accroissement. Correspondence Mathematique Et Phys. 10, 113–121 (1838).

Feigenbaum, M. J. Quantitative universality for a class of nonlinear transformations. J. Stat. Phys. 19 (1), 25–52 (1978).

Marotto, F. R. The dynamics of a discrete population model with threshold. Math. Biosci. 58 (1), 123–128 (1982).

Blumberg, A. A. Logistic growth rate functions. J. Theor. Biol. 21, 42–44 (1968).

Radwan, A. G. On some generalized discrete logistic maps. J. Adv. Res. 4 (2), 163–171 (2013).

Rocha, J. L., Fournier-Prunaret, D. & Taha, A. K. Strong and weak allee effects and chaotic dynamics in richards’ growths. Discrete Continuous Dyn. Systems—Series B. 18, 2397–2425 (2013).

Rocha, J. L., Fournier-Prunaret, D. & Taha, A. K. Big Bang bifurcations in von bertalanffy’s dynamics with strong and weak allee effects. Nonlinear Dyn. 84 (2), 607–626 (2016).

Rocha, J. L., Taha, A. K. & Fournier-Prunaret, D. Big Bang bifurcation analysis and allee effect in generic growth functions. Int. J. Bifurcat. Chaos. 26 (2), 1650108 (2016).

Hassell, M. P. Density-dependence in single-species populations. J. Anim. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.2307/3863 (1975).

Danca, M. F., Fečkan, M. & Kuznetsov, N. Chaos control in the fractional order logistic map via impulses. Nonlinear Dyn. 98 (2), 1219–1230 (2019).

Panigoro, H. S., Rayungsari, M. & Suryanto, A. Bifurcation and chaos in a discrete-time fractional-order logistic model with allee effect and proportional harvesting. Int. J. Dynamics Control. 11 (4), 1544–1558 (2023).

Mendiola-Fuentes, J. et al. A note on stability of fractional logistic maps. Appl. Math. Lett. 125, 107787 (2022).

Wang, Y., Liu, S. & Khan, A. On fractional coupled logistic maps: chaos analysis and fractal control. Nonlinear Dyn. 111 (6), 5889–5904 (2023).

Smith, J. M. Mathematical ideas in biology (CUP Archive, 1968).

Baker, R. E. & Röst, G. Global dynamics of a novel delayed logistic equation arising from cell biology. J. Nonlinear Sci. 30 (1), 397–418 (2020).

da Costa, D. R. & Medrano-T R O, Leonel, E. D. Route to chaos and some properties in the boundary crisis of a generalized logistic map. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 486, 674–480 (2017).

Ashish, C. J. & Chugh, R. Discrete chaotification of a modulated logistic system. Int. J. Bifurcat. Chaos. 31 (05), 2150065 (2021).

Han, X., Mou, J., Jahanshahi, H., Cao, Y. & Bu, F. A new set of hyperchaotic maps based on modulation and coupling. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 137 (4), 523 (2022).

Al-Kaff, M. et al. Exploring chaos and bifurcation in a discrete prey-predator based on coupled logistic map Scientific Reports. Scientific Rep. 14(1), 16118 (2024).

Salman, S. M., Yousef, A. M. & Elsadany, A. A. Dynamic behavior and bifurcation analysis of a deterministic and stochastic coupled logistic map system. Int. J. Dynamics Control. 10 (1), 69–85 (2022).

Bosisio, A., Naimzada, A. & Pireddu, M. Proving chaos for a system of coupled logistic maps: A topological approach. Chaos: Interdisciplinary J. Nonlinear Sci. 34 (3), 033112 (2024).

Aniszewska, D. & Rybaczuk, M. Analysis of the multiplicative Lorenz system. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 25 (1), 79–90 (2005).

Rybaczuk, M. & Stoppel, P. The fractal growth of fatigue defects in materials. Int. J. Fract. 103 (1), 71–94 (2000).

Aniszewska, D. New discrete chaotic multiplicative maps based on the logistic map. Int. J. Bifurcat. Chaos. 28 (09), 1850118 (2018).

Ricker, W. Stock and recruitment. J. Fisheries Board. Can. 11 (5), 559–663 (1954).

Guckenheimer, J. & Holmes, P. Nonlinear oscillations, dynamical systems, and bifurcations of vector fields (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Landau, R. H. et al. A survey of computational physics: introductory computational science (Princeton University Press, 2008).

Layek, G. C. An introduction to dynamical systems and chaos (Springer Nature, 2024).

Grebogi, C., Ott, E. & Yorke, J. A. Crises, sudden changes in chaotic attractors, and transient chaos. Phys. D: Nonlinear Phenom. 7 (1–3), 181–200 (1983).

Darya, A. M. et al. Using intermittent chaotic clocks to secure cryptographic chips. IEEE Embed. Syst. Lett. 16 (4), 529–532 (2024).

Zhang, B. & Liu, L. Chaos-based image encryption: Review, application, and challenges. Mathematics 11 (11), 2585 (2023).

Chatterjee, D., Banik, B. G. & Banik, A. Attack resistant chaos-based cryptosystem by modified Baker map and logistic map. Int. J. Inf. Comput. Secur. 20 (1–2), 48–83 (2023).

Shi, L., Li, X., Jin, B. & Li, Y. A chaos-based encryption algorithm to protect the security of digital artwork images. Mathematics 12 (20), 3162 (2024).

Kanso, A. & Ghebleh, M. A refinement of the logistic map for cryptographic applications. Frankl. Open., : 100333. (2025).

Alvarez, G. & Li, S. Some basic cryptographic requirements for chaos-based cryptosystems. Int. J. Bifurcat. Chaos. 16 (08), 2129–2151 (2006).

Kocarev, L. Chaos-based cryptography: a brief overview. IEEE Circuits Syst. Mag. 1 (3), 6–21 (2002).

Pati, N. C., Layek, G. C. & Pal, N. Bifurcations and organized structures in a predator-prey model with hunting cooperation Vol. 140, 110184 (Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 2020).

Elghandour, A., Salah, A. & Karawia, A. A new cryptographic algorithm via a two-dimensional chaotic map. Ain Shams Eng. J. 13 (1), 101489 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The research presented was financially supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2018JY0256).

Funding

This work was supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2018JY0256).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G. S. L. wrote the main manuscript text and K. B. C. Writing- Reviewing and Editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, S., Kan, B. Chaos of the new multiplicative logistic map. Sci Rep 15, 43743 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28695-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28695-y