Abstract

In this paper, we report a novel Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ nanocatalyst as a highly active, recyclable, and sustainable platform for the synthesis of triarylpyridines. This catalyst integrates the benefits of a mesoporous MCM-41 support, magnetic Fe₃O₄ core, and ZnCl₂ Lewis acid centers stabilized by cystine linkers, resulting in high surface area, strong catalytic activity, and excellent stability. Under optimized conditions (100 °C, 2 h, 7 mol% catalyst) in a deep eutectic solvent (choline chloride–glycerol), twenty triarylpyridines were obtained in excellent yields (84–98%). The system exhibited broad substrate tolerance, efficiently converting electron-donating, electron-withdrawing, sterically hindered, and heteroaryl substrates with consistent turnover numbers (TON = 12.0–14.0) and turnover frequencies (TOF = 6.0–7.0 h⁻1). Compared to conventional catalysts, this method offers significantly shorter reaction times, higher yields, operation under air without oxidants, and facile magnetic recovery with reusability up to eight cycles. Thus, this approach provides a practical, eco-friendly, and scalable alternative for the synthesis of triarylpyridines, aligning efficiency with sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

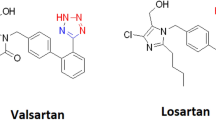

Triarylpyridines represent an important class of heterocyclic compounds with wide applications in pharmaceuticals, materials science, and organic electronics1,2. Their structural framework imparts significant biological activity, making them key scaffolds in anticancer, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral agents2,3,4. In medicinal chemistry, triarylpyridine derivatives have been reported as kinase inhibitors, estrogen receptor modulators, and neuroprotective agents, underlining their role as privileged structures for drug discovery3,5. Beyond pharmaceuticals, triarylpyridines are also valuable in materials chemistry due to their conjugated aromatic system1,2. They exhibit strong fluorescence, excellent thermal stability, and electron-transport properties, enabling their use in fluorescent probes, organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), and functional materials for optoelectronic devices6,7. Given this dual significance in both therapeutic and technological applications, the development of efficient, sustainable, and versatile synthetic methods for triarylpyridines remains a high priority.

Traditional methods for constructing triarylpyridines often rely on transition-metal-catalyzed cyclization, multicomponent reactions, or oxidative coupling strategies8. While effective, these approaches typically require long reaction times, elevated temperatures, expensive or toxic catalysts, and organic solvents. Furthermore, many processes depend on oxidants such as O₂, peroxides, or stoichiometric reagents, leading to increased waste generation and environmental concerns9. Reported catalytic systems have achieved moderate to good yields but suffer from limitations such as poor reusability, catalyst leaching, and the use of hazardous solvents like toluene10. These drawbacks restrict their large-scale applicability and fail to meet modern standards of green chemistry11. Hence, designing catalytic systems that are efficient, recyclable, environmentally benign, and broadly applicable is essential for advancing triarylpyridine synthesis.

Magnetic nanocatalysts have emerged as powerful tools in sustainable organic synthesis due to their high surface area, tunable morphology, and facile recovery using an external magnet12,13,14,15,16. The incorporation of functional supports, such as mesoporous silica, not only enhances stability but also allows for the immobilization of active sites, preventing catalyst leaching and enabling reusability17,18. Fe₃O₄-based nanocatalysts, in particular, are widely studied for their biocompatibility, low toxicity, and magnetic separability19,20. When combined with porous supports and functional linkers, these systems can host a variety of catalytic sites, offering versatility for acid, base, and transition-metal-mediated transformations21,22. Their reusability reduces costs and waste, making them ideal candidates for green and scalable synthesis23,24,25.

Zinc-based catalysts have gained increasing attention in organic synthesis owing to their low toxicity, natural abundance, affordability, and strong Lewis acidity. ZnCl₂, in particular, efficiently activates carbonyl groups and facilitates condensation reactions26,27,28. Unlike many transition-metal catalysts, zinc salts are environmentally benign and compatible with a wide range of functional groups29,30. This makes zinc an attractive choice for heterocyclic synthesis, including the construction of pyridine frameworks.

Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) have recently emerged as green alternatives to volatile organic solvents. They are formed by the simple mixing of hydrogen bond donors and or by varying the molar ratios of the donors and acceptors. Their physicochemical properties, such as acidity and polarity, strongly influence reaction behavior, particularly fragmentation performance and solubilization capacity. High solvent polarity indicates a strong ability to dissolve diverse substrates, leading to nonvolatile, biodegradable, and low-cost reaction media31,32. The choline chloride–glycerol system is particularly attractive because of its biodegradability, low toxicity, and ability to dissolve a wide range of organic and inorganic compounds33. Moreover, DESs often enhance reaction rates and selectivity by stabilizing reactive intermediates and facilitating efficient heat transfer34.

In this work, we introduce a novel Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ nanocatalyst system in a choline chloride–glycerol solvent for the synthesis of triarylpyridines. This method integrates the advantages of magnetic nanocatalysts, zinc-based Lewis acid activation, and green solvent design to provide a highly efficient and sustainable platform. Under optimized conditions (100 °C, 2 h), the system delivered a broad scope of triarylpyridines in high yields (84–98%) with consistent TON and TOF values. Importantly, the catalyst is magnetically recoverable and reusable for at least eight cycles, surpassing traditional catalytic systems in activity, stability, and eco-friendliness. This strategy thus represents a superior and scalable alternative for triarylpyridine synthesis, aligning with the principles of green chemistry.

Experimental

Materials and methods

In this study, all materials were obtained from reputable suppliers, including Fisher, Sigma-Aldrich, Fluka, and Merck, and were used directly without further purification. The progress of the reactions was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Purification was carried out by column chromatography using Merck silica gel (230–400 mesh) as the stationary phase. The products were characterized by 1 H and 13 C NMR spectroscopy, recorded on a Bruker spectrometer operating at 400 MHz and 100 MHz, respectively.

Preparation of Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine nanocomposite

The innovative magnetic nanostructure Fe3O4@MCM-41 was successfully synthesized through a straightforward chemical co-precipitation method, echoing the strategies outlined in our previous research endeavors. This synthesis enabled the incorporation of iron oxide into the mesoporous silica framework, resulting in a composite with notable magnetic properties and good structural stability. To create the Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine nanocomposite, A measured quantity of 1.5 g of cystine was mixed with 1 g of Fe₃O₄@MCM-41 in 50 mL of deionized water. This mixture was then subjected to reflux conditions for a continuous 12 h, allowing for a thorough interaction of the components. Upon completion of this reaction, we isolated the Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine nanocomposite using a strong magnetic field for extraction. The resulting material was carefully washed with deionized water and ethanol to remove any unreacted elements and impurities before being left to dry overnight in a 60 °C drying oven, ensuring optimal preservation of its properties.

Preparation of Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ nanocomposite

To create the cutting-edge Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ nanocomposite, we commenced with precision, carefully integrating 4 mmol of ZnCl₂ into a uniformly blended suspension of 1 g of ultrasonically dispersed Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine, all within 50 mL of ethanol. This mixture was subjected to a vigorous reflux at elevated temperatures for a duration of 12 h, fostering an intimate interaction among the components and catalyzing their transformation into the desired nanocomposite. Once the synthesis was complete, we employed a meticulous magnetic separation technique to extract the newly formed nanocomposite from the swirling liquid, ensuring no precious particles were left behind. The isolated product underwent a rigorous washing process using hot water and ethanol, eliminating any lingering impurities and enhancing its purity. To finalize the process, we carefully dried the nanocomposite at a controlled temperature of 60 °C, preserving its structural integrity while bestowing it with a refined finish. The result was a striking and highly stable nanocomposite, poised for further exploration and applications.

General method for the preparation of triarylpyridines

A carefully crafted mixture of aromatic aldehydes (0.5 mmol) and various acetophenone derivatives (1.0 mmol) was blended with NH4OAc (1.5 mmol) and a finely tuned catalyst, Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ (7 mol%). The mixture was then introduced into a solvent of ChCl-glycerol (3 mL) and subjected to vigorous stirring at a steady 100 °C for 2 h. As the reaction reached completion, the catalyst was skillfully extracted using magnetic separation, leaving behind the reaction mixture, which was further diluted with 10 mL of a saturated aqueous solution of sodium Na2SO4. The mixture was extracted with dichloromethane in three successive washes (3 × 5 mL), ensuring that every trace of the product was captured. The organic layers, now combined, were washed with a brine solution to purge any impurities and then dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, creating a clean slate for the next phase. The solvent was gently evaporated under reduced pressure, revealing a tantalizing crude product. To attain the desired products, the crude material underwent purification via silica gel column chromatography, utilizing a mixture of hexane and ethyl acetate (4:1) as eluents. The identity and structural integrity of the triarylpyridine products were confirmed by meticulous comparison with established literature, along with insightful analyses of 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, ensuring that the results were both accurate and reliable.

Catalyst recovery and reuse

The recyclability of the Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ catalyst was examined in the model synthesis of triphenyl pyridine (4a) under the optimized reaction conditions. A mixture of benzaldehyde (0.5 mmol), acetophenone (1 mmol), and ammonium acetate (1.5 mmol) was stirred in 3 mL of ChCl–glycerol at 100 °C for 2 h in the presence of Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ (7 mol%). After completion, the reaction mixture was cooled, and the catalyst was separated magnetically, washed with ethanol and water, and dried at 60 °C for reuse. This procedure was repeated for several consecutive runs to assess the catalyst’s stability and reusability.

Recovery and reuse of DES

After completion of the reaction, the catalyst was magnetically separated, washed successively with ethanol and water, and dried for reuse. The remaining reaction mixture was diluted with 10–20 mL of deionized water and cooled to 0–5 °C for about 30 min to induce crystallization of the product. The crystalline solid was collected by vacuum filtration, washed with cold water followed by cold ethanol, and dried under vacuum at 50 °C to constant weight. The combined filtrate containing the deep eutectic solvent (ChCl–glycerol) was concentrated under reduced pressure at 80 °C to remove water and volatile impurities. The recovered DES was further dried under high vacuum to ensure minimal moisture content and reused directly in subsequent reactions. This procedure allowed efficient recovery of both the catalyst and solvent, supporting the sustainability of the developed methodology.

Results and discussions

The synthetic route for preparing the Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ nanocomposite involves several sequential steps as illustrated in Fig. 1. Initially, Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles are synthesized through a co-precipitation reaction of FeCl₃·6H₂O and FeCl₂·4H₂O in distilled water under a nitrogen atmosphere, using NH₄OH as the precipitating agent at 80 °C. The obtained Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles are then coated with MCM-41, a mesoporous silica material, using tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) as the silica precursor and CTAB as the surfactant template, yielding Fe₃O₄@MCM-41. This step provides a high surface area and ordered mesoporous channels suitable for further functionalization. Subsequently, the Fe₃O₄@MCM-41 nanocomposite is functionalized with cystine, an amino acid containing disulfide and amine functional groups, via reflux in deionized water. This modification introduces nitrogen- and sulfur-containing groups on the nanocomposite surface, which act as coordination sites. Finally, ZnCl₂ is immobilized onto the cystine-modified Fe₃O₄@MCM-41 by refluxing in ethanol. The Zn2⁺ ions coordinate with the amine and thiol groups of cystine, forming the final Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ nanocomposite. This material combines the magnetic recoverability of Fe₃O₄, the high surface area of MCM-41, and the catalytic activity provided by Zn2⁺ coordinated cystine ligands.

The architecture of the Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ nanocomposite was elucidated through a range of advanced spectroscopic techniques. These included Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), which provided insights into molecular interactions; thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), which revealed thermal stability; and X-ray diffraction (XRD), which illuminated the crystalline structure. Additionally, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) and inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) detailed the elemental composition, while Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis assessed the material’s surface area and porosity. Vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) offered crucial data on magnetic properties, complemented by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) that showcased the composite’s morphology at various scales, painting a comprehensive picture of its features and functionalities.

FT-IR spectrums of nanocomposites (Fig. 2)

The FT-IR spectra in Fig. 2 confirm the successful stepwise functionalization of the Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ catalyst. For Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles, the characteristic Fe–O stretching band appears around 580 cm⁻1, which is a distinctive peak for magnetite. After coating with MCM-41, new absorption bands corresponding to Si–O–Si stretching (~ 1080 cm⁻1), Si–O–Si bending (~ 800 cm⁻1), and symmetric stretching (~ 460 cm⁻1) emerge, indicating the successful formation of the mesoporous silica shell around Fe₃O₄. Additionally, C–H stretching vibrations around 2920–2850 cm⁻1 also confirm the presence of organic template remnants during synthesis. Upon functionalization with cystine, new peaks appear around 1650 cm⁻1 and 1540 cm⁻1, corresponding to C=O stretching (amide) and N–H bending vibrations, respectively. These signals confirm the attachment of cystine onto the silica surface. Moreover, the band near 3300–3400 cm⁻1 indicates N–H and O–H stretching, while the weak absorption around 2500–2600 cm⁻1 can be attributed to –SH groups from cystine. Finally, in the spectrum of Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂, slight shifts in the amine and thiol-related bands are observed due to the coordination of Zn2⁺ ions with nitrogen and sulfur groups, confirming the successful immobilization of zinc chloride on the nanocomposite structure.

TGA spectrums of nanocomposites (Fig. 3)

The thermal stability and composition of the prepared nanocomposites are evaluated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), as shown in Fig. 3. The pure Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles show negligible weight loss up to 800 °C, indicating their high thermal stability and absence of significant organic or volatile components. For Fe₃O₄@MCM-41, a slight weight loss is observed below 200 °C, which can be attributed to the removal of physisorbed water and surface hydroxyl groups. A further small weight reduction between 200 and 600 °C indicates the decomposition of residual surfactant (CTAB) used during the synthesis of MCM-41. In the case of Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine, a more significant weight loss is observed between 200 and 600 °C due to the decomposition of organic cystine ligands grafted onto the silica surface. This confirms the successful introduction of organic functionalities into the composite. The Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ catalyst exhibits a similar weight loss profile but with slightly higher degradation in the same region, reflecting the presence of coordinated cystine-ZnCl₂ complexes. Overall, the gradual weight losses indicate increasing amounts of organic content with each functionalization step, while the high residual weight at 800 °C demonstrates good thermal stability of the final catalyst.

XRD patterns of nanocomposites (Fig. 4)

The XRD analysis in Fig. 4 provides structural confirmation of the Fe₃O₄ and Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ nanocomposite. The Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles exhibit characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ values of approximately 30°, 35°, 43°, 53°, 57°, and 63°, which correspond to the (220), (311), (400), (422), (511), and (440) crystal planes of the cubic spinel structure of magnetite. These peaks match well with the standard JCPDS card for Fe₃O₄, confirming the crystalline phase purity of the nanoparticles. For the Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ nanocomposite, the XRD pattern retains the main diffraction peaks of Fe₃O₄, confirming that the crystalline spinel structure of the magnetic core remains intact after coating, functionalization, and ZnCl₂ immobilization. However, a slight decrease in peak intensity is observed, which can be attributed to the amorphous nature of the silica shell and organic functional groups surrounding the Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles. This indicates successful surface modification without altering the crystalline structure of the Fe₃O₄ core, ensuring that the magnetic properties are preserved while introducing catalytic functionality.

EDX analysis of Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine and Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂

The EDX spectrum of Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine confirms the presence of Fe, O, and Si, corresponding to the magnetic core and silica framework, along with N, C, and S peaks indicating cystine functionalization (Fig. 5). After ZnCl₂ modification, additional Zn and Cl peaks appear, confirming coordination of Zn2⁺ ions with cystine groups while maintaining the original framework. These results verify the successful synthesis of the Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ nanocomposite as a stable, multifunctional catalyst combining magnetic recoverability with Zn-based catalytic activity. ICP-OES analysis further revealed a Zn content of 1.42 × 10⁻3 mol g⁻1, confirming substantial metal incorporation.

BET analysis of Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ (Fig. 6)

The BET nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm of Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ exhibits a type IV isotherm with an H3-type hysteresis loop, characteristic of mesoporous materials (Fig. 6). This behavior originates from capillary condensation within mesopores, while the H3 hysteresis loop arises from the presence of interparticle voids or slit-like pores generated by the close packing of nearly spherical particles35. The high adsorption volume at elevated relative pressures indicates the presence of well-defined mesopores, which is consistent with the MCM-41 silica framework. The surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution are crucial parameters that directly affect the catalyst’s performance. The BET analysis unveiled that the synthesized Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ catalyst boasts a specific surface area of 312.0 m2/g, highlighting its remarkable capacity for interaction and reaction. Furthermore, the catalyst’s pore volume was determined to be 0.52 cm3/g, indicating a significant ability to harbor substances within its structure. Detailed pore size analysis revealed the formation of mesopores, typically measuring between 10 and 20 nm, harmonizing beautifully with the average particle size obtained from SEM and TEM imaging, thus confirming the structure of this catalyst. The data suggest that despite partial reduction in surface area due to cystine grafting and ZnCl₂ immobilization, the nanocomposite retains a sufficiently high surface area and porous structure, making it suitable for heterogeneous catalysis applications.

VSM analysis of Fe₃O₄ NPs and Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂

The magnetic properties of the samples (Fig. 7) were evaluated using VSM, revealing distinct differences between Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles and the Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ catalyst. Pure Fe₃O₄ exhibited a high saturation magnetization of 66.54 emu g⁻1, confirming strong superparamagnetic behavior and facile magnetic separation. After coating with MCM-41, cystine, and ZnCl₂, the magnetization decreased to 48.49 emu g⁻1 due to the non-magnetic layers. Nevertheless, the catalyst retained sufficient magnetic strength for rapid separation and reuse, confirming its effective magnetic recoverability and multifunctional catalytic nature.

SEM and TEM analysis of Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ catalyst

The SEM images (Fig. 8) at 1 µm and 500 nm scales provide clear insights into the surface morphology and aggregation behavior of the Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ catalyst. The material exhibits a relatively uniform spherical-like morphology with moderate aggregation, which is typical for magnetic nanocomposites due to dipole–dipole interactions between Fe₃O₄ cores. The high-magnification images reveal a rough surface decorated with smaller particles, confirming the successful deposition of the mesoporous MCM-41 silica shell followed by cystine and ZnCl₂ functionalization. This morphology not only enhances structural stability but also increases the number of accessible active sites through the mesoporous channels.

The TEM images (Fig. 9) at 100 nm and 50 nm scales further confirm the core–shell structure, showing dark Fe₃O₄ cores encapsulated by lighter mesoporous silica shells. The uniform contrast difference validates the presence of multiple Fe₃O₄ cores embedded within the silica framework while preserving porosity even after modification. These structural features ensure easy diffusion of reactant molecules and efficient exposure of Zn2⁺ catalytic sites. The particle size distribution histogram derived from TEM analysis (Fig. 9) reveals an average particle size of approximately 15.7 nm, consistent with nanoscale dimensions observed across the sample. Collectively, the SEM and TEM analyses confirm the successful formation of a mesoporous, magnetically recoverable Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ nanocatalyst with a stable core–shell architecture and high accessibility of catalytic sites.

Final confirmation

All characterization results confirm that Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ was successfully synthesized as a thermally stable, mesoporous, and magnetically recoverable nanocatalyst with well-defined Zn2⁺ active sites anchored through cystine on the Fe₃O₄@MCM-41 framework. The stepwise synthesis from Fe₃O₄ to Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ was verified by FT-IR spectra, which revealed characteristic Fe–O, Si–O–Si, and cystine functional groups (N–H, C=O, S–H), along with notable band shifts upon Zn2⁺ coordination. TGA analysis indicated distinct weight losses corresponding to surface water removal, cystine decomposition, and Zn complexation, confirming the good thermal stability of the final catalyst. XRD patterns retained the Fe₃O₄ spinel structure with slight peak intensity reduction due to the silica and organic layers, indicating that the crystalline integrity was preserved. EDX and ICP-OES analyses verified the presence of Fe, Si, O, C, N, S, Zn, and Cl, confirming successful ZnCl₂ immobilization and quantifying Zn loading. BET analysis exhibited a type-IV isotherm with H3 hysteresis, characteristic of mesoporous materials, while maintaining sufficient surface area and pore volume for catalytic accessibility. SEM and TEM images showed spherical and uniformly coated nanostructures, with TEM further revealing Fe₃O₄ cores encapsulated by mesoporous silica shells and ordered channels retained after functionalization. VSM measurements demonstrated that, although the magnetization decreased from 66.538 emu/g for Fe₃O₄ to 48.491 emu/g for the final catalyst, the material still exhibited adequate magnetic response for recovery.

Catalytic activity in the synthesis of triaryl pyridines

Table 1 summarizes the systematic optimization of reaction conditions for the synthesis of triphenyl pyridine (product 4a) from benzaldehyde (1), acetophenone (2), and ammonium acetate (3) in the presence of a Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ catalyst. The table carefully explores different solvents, reaction times, and catalyst loadings to maximize the product yield.

The solvent played a crucial role in determining the reaction efficiency. Conventional solvents such as water, ethanol, and acetonitrile gave moderate to low yields, while polar, high-boiling solvents like PEG and [BMIM]PF₆ significantly improved the results. Glycerol and deep eutectic solvents, particularly ChCl–glycerol, provided the highest yields (up to 98%) in shorter times, highlighting their superior ability to enhance catalytic activity and stabilize intermediates.

Finally, catalyst loading optimization (entries 17–23) showed that 7 mol% of Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ in ChCl–glycerol at 100 °C was the most efficient condition, affording a near-quantitative yield (99%). Lower loadings (4 mol%) or higher ones (10 mol%) did not improve the outcome, while control experiments with bare Fe₃O₄, MCM-41, or without catalyst confirmed the essential role of the functionalized catalyst. Without catalyst, no reaction occurred, underscoring the necessity of the designed catalytic system.

Overall, the optimization study demonstrates that the combination of Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ (7 mol%) and ChCl–glycerol (100 °C) provides the best conditions, yielding triphenyl pyridine efficiently and sustainably (Entry 17). The choice of green solvent systems and recyclable heterogeneous catalyst highlights both high catalytic performance and environmentally friendly methodology.

Scope of the method

The Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ catalyst system in choline chloride/glycerol deep eutectic solvent offers a broad and general platform for the synthesis of triarylpyridines (Table 2). The reactions proceed efficiently under relatively mild conditions (100 °C, 2 h), providing high isolated yields (84–98%) across 20 diverse examples. The system is tolerant of a wide range of functional groups, including both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents, as well as heteroaryl moieties. The relatively narrow range of TON (12.0–14.0) and TOF (6.0–7.0 h⁻1) values demonstrates the robustness of the catalyst, showing that performance is maintained regardless of substrate structure. The use of a magnetically recoverable Fe₃O₄ core combined with a mesoporous MCM-41 support and cystine-ZnCl₂ complex ensures high surface area, strong Lewis acidity, and facile catalyst recycling. These features make the system not only efficient but also practical for sustainable synthesis. Electron-donating substituents (e.g., Me, OMe) enhance reaction efficiency, likely due to increased nucleophilicity of the aryl aldehydes and stabilization of the developing cationic intermediates in the multicomponent condensation pathway. These substrates generally produced the highest yields (96–98%) and maximum TON/TOF values (up to 14.0 and 7.0 h⁻1), as seen for products 4a, 4b, 4n, and 4o.

On the other hand, electron-withdrawing substituents (e.g., NO₂, Cl, Br) tend to slightly reduce yields (87–94%) because of reduced electron density on the aromatic ring, making nucleophilic attack less favorable. However, the drop is minor, as Lewis acid activation by ZnCl₂ is strong enough to drive the condensation. This balance explains why even substrates like 4c (NO₂) and 4t (tetrachloro) still achieve high yields (90% and 84%, respectively). Substrates with bulky or multiple halogen substituents (e.g., 4m, 4t) display the lowest yields (87% and 84%), which corresponds to the lowest TON/TOF values in the table. Steric hindrance likely slows down intermediate formation and cyclization, while cumulative electron-withdrawing effects further reduce reactivity. These examples highlight the limits of the method when highly substituted or sterically congested substrates are employed. The method tolerates heteroaryl partners, including pyridine, thiophene, and furan derivatives (e.g., 4h, 4i, 4r, 4s). Despite the possibility of catalyst poisoning or competitive coordination of heteroatoms with Zn2⁺ centers, yields remain in the 87–95% range, with TON values around 12.4–13.6. This reflects the stabilizing role of the mesoporous support and cystine linker, which provide selective activation without deactivating the catalyst.

This methodology provides a highly general, functional-group-tolerant, and efficient route to triarylpyridines. The combination of deep eutectic solvent, heterogeneous Fe₃O₄-based catalyst, and Lewis acid ZnCl₂ sites ensures consistent productivity across diverse substrates. While electronic and steric effects cause slight variations in yield and turnover numbers, the system maintains high efficiency throughout. In practice, the TON values suggest that further improvements in catalyst productivity will be best achieved by lowering catalyst loading rather than altering substrates.

Plausible mechanism

The proposed mechanistic pathway for the preparation of triaryl pyridines in the presence of Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂/ChCl-Glycerol involves a multi-step sequence. Initially, benzyl alcohol undergoes oxidation to form the corresponding aldehyde intermediate (Fig. 10). This aldehyde then undergoes condensation with another aldehyde molecule, forming Intermediate A. The presence of the catalytic system facilitates dehydration, leading to the generation of reactive intermediates. Subsequently, Intermediate A reacts with ammonia acetate (NH₄OAc) to form an imine-type species, which is stabilized by hydrogen bonding and coordination with the ZnCl₂ centers. This results in Intermediate B, a crucial step toward building the pyridine framework. Through further tautomerization and nucleophilic addition, Intermediate C is formed, containing both amine and carbonyl functionalities, which set the stage for cyclization. Finally, cyclization and oxidation processes convert Intermediate C into Intermediate D, which undergoes aromatization to give the final triaryl pyridine products. The Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ catalyst, with its strong Lewis acidic sites and the deep eutectic solvent system (ChCl-Glycerol), provides a synergistic effect, enhancing the reaction rate, improving selectivity, and enabling efficient conversion under mild and green conditions.

Catalyst recovery and reuse

Figure 11 illustrates the recyclability of the Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ catalyst in the synthesis of triphenyl pyridine (product 4a). In the first cycle, the catalyst gave a yield of nearly 98%, and this high efficiency was retained in subsequent cycles with only a gradual decrease. The yields remained above 95% up to the 5th cycle, demonstrating the robustness of the catalyst under reaction conditions. Beyond the 6th to 8th cycles, a slight drop in yield was observed, with the yield decreasing to around 87% by the 8th cycle. This decline may be attributed to minor catalyst deactivation due to leaching of active ZnCl₂ sites or partial surface fouling. Nevertheless, the catalyst still maintained a high efficiency after multiple uses, confirming its excellent stability, reusability, and suitability for sustainable large-scale applications.

To thoroughly assess the structural integrity of the catalyst following repeated utilization, comprehensive FT-IR and XRD analyses were conducted on both fresh and reused samples, as illustrated in Fig. 12. The XRD patterns of the reused catalyst, even after eight rigorous runs, bore a striking resemblance to those of the pristine catalyst, exhibiting no significant shifts or loss of diffraction peaks. This consistency indicates that the crystalline architecture of the Fe3O4@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl2 nanocatalyst remarkably retains its integrity throughout the refilling process. Similarly, the FT-IR spectra of the utilized catalyst mirrored those of the new material closely, confirming the preservation of key functional groups and the steadfastness of the guanidine and graphene oxide framework. The strong correlation between the FT-IR and XRD spectra before and after numerous cycles underlines the resilience of the catalyst’s structure and functionality. The recycled catalyst demonstrated an impressive palladium content of 1.42 × 10⁻3 mol/g, a mere fraction lower than the 1.39 × 10⁻3 mol/g measured for the fresh catalyst. This negligible difference serves as a testament to the material’s remarkable resistance to metal loss during the catalytic process. These compelling findings highlight the characteristics of the Fe3O4@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl2 nanocomposite, showcasing not only outstanding structural and magnetic stability but also durability and reusability. This positions it as an exemplary candidate for sustained catalytic applications, promising unparalleled efficiency and reliability across a spectrum of chemical processes.

Comparison with reported methods

Table 3 shows a comparison between the newly developed catalytic system (Entry 6) and previously reported methods (Entries 1–5). Traditional catalysts such as Cu(OTf)₂, Fe₃O₄ NPs, VNU-22, and B(C₆F₅)₃ required longer reaction times (8–14 h) at elevated temperatures (100–120 °C) and often relied on harsh conditions like organic solvents (toluene) or oxidants (t-BuOOH, O₂). While yields ranged from 76 to 90%, these methods lacked reusability, limiting their practicality and sustainability. In contrast, the Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂/ChCl-Glycerol system (Entry 6) achieved an excellent yield of 98% within just 2 h at 100 °C under air, highlighting its superior catalytic activity. Moreover, unlike earlier methods, this catalyst demonstrated remarkable recyclability (up to 8 cycles), underscoring its cost-effectiveness and eco-friendliness. Hence, this newly developed system outperforms conventional methods by combining high efficiency, shorter reaction times, mild conditions, and sustainability.

Conclusion

The Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂/ChCl–glycerol catalytic system proved to be an efficient, versatile, and sustainable platform for the synthesis of triarylpyridines. It demonstrated excellent activity across a broad substrate range, including electron-rich, electron-poor, sterically hindered, and heteroaryl compounds, maintaining high yields under mild conditions. The deep eutectic solvent medium provided a green and environmentally benign alternative to traditional organic solvents, eliminating the need for external oxidants. The catalyst exhibited remarkable stability and reusability, retaining high performance over multiple cycles with minimal loss of activity. Overall, this methodology offers a practical, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly approach suitable for large-scale and pharmaceutical applications.

Data availability

The detailed spectra for both ¹H NMR and ¹³C NMR of the diaryl ether products are carefully assembled and showcased in the Supplementary File.

References

Shabalin, D. A. Recent advances and future challenges in the synthesis of 2, 4, 6-triarylpyridines. Org Biomol. Chem. 19, 8184 (2021).

Ren, Y. M. & Cai, C. Three-components condensation catalyzed by molecular iodine for the synthesis of 2, 4, 6-triarylpyridines and 5-unsubstituted-3, 4-dihydropyrimidin-2 (1 H)-ones under solvent-free conditions. Monatshefte für Chemie Chem. Mon. 140(1), 49–52 (2009).

Davoodnia, A., Bakavoli, M., Moloudi, R., Tavakoli-Hoseini, N. & Khashi, M. Highly efficient, one-pot, solvent-free synthesis of 2, 4, 6-triarylpyridines using a Brønsted-acidic ionic liquid as reusable catalyst. Monatshefte für Chemie-Chem. Mon. 141(8), 867–870 (2010).

Ghobadi, M., Kargar Razi, M., Javahershenas, R. & Kazemi, M. Nanomagnetic reusable catalysts in organic synthesis. Synth. Commun. 51, 647-669 (2021).

Negi, A., Mirallai, S. I., Konda, S. & Murphy, P. V. An improved method for synthesis of non-symmetric triarylpyridines. Tetrahedron 27(121), 132930 (2022).

Shabalin, D. A., Dvorko, M. Y., Schmidt, E. Y. & Trofimov, B. A. Regiocontrolled synthesis of 2, 4, 6-triarylpyridines from methyl ketones, electron-deficient acetylenes and ammonium acetate. Org. Biomol. Chem. 19(12), 2703–2715 (2021).

Dadashi, H., Hajinasiri, R. & Hossaini, Z. Fe3O4/ZnO/MWCNTs magnetic nanocomposites promoted synthesis of new chromeno pyrano [2, 3-d] thiazins: Investigation of antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Appl. Organometallic Chem. 35(4), e6168 (2021).

Song, Z., Huang, X., Yi, W. & Zhang, W. One-pot reactions for modular synthesis of polysubstituted and fused pyridines. Org. Lett. 18(21), 5640–5643 (2016).

Kadu, V. D., Chandrudu, S. N., Hublikar, M. G., Bansode, S. I. & Bhosale, R. B. Metal-free sustainable N-α-C (sp3)-H functionalization of arylmethylamines with arylmethylketones to synthesis of kröhnke pyridines under solvent-free condition. Catal. Lett. 155(1), 49 (2025).

Torabi, M., Zolfigol, M. A., Zarei, N., Yarie, M. & Azizian, S. Engineering iodine decorated azo-bridged porous organic polymer: A brilliant catalyst for the preparation of 2, 4, 6-trisubstituted pyridines. Polymer 15(317), 127873 (2025).

Hatvate, N. & Gupta, J. An efficient, green and solvent-free three-component synthesis of 2, 4, 6-triarylpyridines utilizing ZSM-5 as a heterogeneous catalyst. Synth. Commun. 54(20), 1760–1770 (2024).

Aghajeri, M., Kiasat, A., R. & Sanaeishoar, H. Synthesis, characterization and application of Fe3O4@ MCM-BP as a Novel Nanomagnetic Reusable Basic Catalyst for the one Pot Solvent-Free Synthesis of Dihydropyridine, Polyhydroquinoline and Polyhydroacridine Derivatives via Hantzsch Multicomponent Condensation Reaction. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 39, 35 (2020).

Abudken, A. M. H., Saadi, L., Ali, R. & Kazemi, M. Fe3O4@ SiO2-DHB/DI (S-NH)-Pd (0) nanocomposite: a novel, efficient, and reusable heterogeneous catalyst for carbonylative preparation of N-aryl amides. BMC Chem. 19, 71 (2025).

Naderi, M. & Farhadi, M. Synthesis of new derivatives of 1, 2, 3-triazoles using CuFe2O4 catalyst. Biol. Mol. Chem. 2(2), 69–81 (2024).

Ali, R., Hussein, S. A., Znad, M. R. & Al-Delfi, M. N. Chem. Africa 8, 839 (2025).

Ali, R. & Shiri, L. Synthesis of Tetrahydrobenzo [b] pyran derivatives using reusable CoFe2O4@ SiO2-CPTES-Melamine-Cu nanocatalyst. J. Appl. Organometallic Chem. 5, 97-111 (2025).

Kazemi, M. & Shiri, L. Recoverable bromine-containing nano-catalysts in organic synthesis. Mini Rev. Org. Chem. 15(2), 86–104 (2018).

Naderi, M. & Nademi, A. Efficient synthesis of Fe3O4@ SiO2-NEP-Cu catalyst for the three-component coupling reaction of se powders, aryl iodides and azoles. J.Synth. Chem. 3(3), 231–248 (2024).

Shafik, M. S. & Saif, S. One-pot access to sulfonamides under green conditions in the presence of Fe3O4@ SiO2-picolylamine-Pd catalyst. J. Synth. Chem. 3(2), 74–90 (2024).

Fajer, A. N., Al-Bahrani, H. A., Kadhum, A. A. H. & Kazemi, M. Synthesis of pyrano-pyrimidines: recent advances in catalysis by magnetically recoverable nanocatalysts. Mol. Divers. 28, 3523–3555 (2023).

Pramanik, M. & Bhaumik, A. Phosphonic acid functionalized ordered mesoporous material: A new and ecofriendly catalyst for one-pot multicomponent Biginelli reaction under solvent-free conditions. ACS appl. Mater. Interfaces. 6(2), 933–941 (2014).

Ray, S., Das, P., Bhaumik, A., Dutta, A. & Mukhopadhyay, C. Covalently anchored organic carboxylic acid on porous silica nano particle: A novel organometallic catalyst (PSNP-CA) for the chromatography-free highly product selective synthesis of tetrasubstituted imidazoles. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 10(458), 183–195 (2013).

Kavyani, S. & Baharfar, R. Design and characterization of Fe3O4/GO/Au-Ag nanocomposite as an efficient catalyst for the green synthesis of spirooxindole-dihydropyridines. Appl. Organometallic Chemist. 34(4), e5560 (2020).

Sead, F. F., Jain, V., Kumar, A., MM, R., Kundlas, M., Gupta, S.& Javahershenas, R. Magnetically recoverable catalysts for efficient multicomponent synthesis of organosulfur compounds. RSC Advances 15, 3928 (2025).

Ghorbani, R. & Zahedi, M. Magnetic heterogeneous catalyst Ni0. 25Mn0. 25Cu0. 5Fe2O4: Its efficiency in the synthesis of tetrazole heterocycles with biological properties. Biol. Mol. Chem. 2(1), 1–2 (2024).

K. Sudhakara et al. Sudhakara, K., Praveen, K. A., Kumar, B. P., Raghavender, A., Ravi, S., Keniec, D. N., & Lee, Y. I. Synthesis of γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles and catalytic activity of azide-alkyne cycloaddition reactions. Asian J. Nanosci. Mater. 5, 243 (2022).

Jalili, M. & Salehpour, M. Preparation of ZnO nanocatalyst and its use in the synthesis of tetraketones. J. Synth. Chem. 3(2), 149–162 (2024).

Mokhtari, M. & Naseri, B. Application of ZnS-ZnFe2O4 heterogeneous catalyst in the synthesis of pyridazinon compounds. Nanomater. Chem. 2(1), 66–78 (2024).

Hemmesi, L. & Naeimi, H. Preparation and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles supported on reduced graphene oxide and using as an effective catalyst for synthesis of l, 4-dihydropyrimidinones under solvent-free conditions. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 60(3), 477–488 (2023).

Mustafa, A. M. & Younes, A. One-pot synthesis of new pyranopyrazole derivatives using ZnO. Nanomater. Chem. 1(2), 120–130 (2024).

Li, W., Liu, Q., Zhang, Y., Li, C. A., He, Z., Choy, W. C. & Kyaw, A. K. K. Biodegradable materials and green processing for green electronics. Adv. Mater. 32(33), 2001591 (2020).

Wang, H., Chen, J., Pei, Z., Huang, J., Wang, J., Yang, S., & Li, H. Enhancing lignocellulosic biorefinery sustainability: Mechanisms and optimization of microwave-responsive deep eutectic solvents for rapid delignification. Biofuel Res. J. 12(1), 2306–2318 (2025).

Grudniewska, A., de Melo, E. M., Chan, A., Gniłka, R., Boratynski, F., & Matharu, A. S. Enhanced protein extraction from oilseed cakes using glycerol–choline chloride deep eutectic solvents: a biorefinery approach. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6(11), 15791-15800 (2018).

Rafiee, K., Schritt, H., Pleissner, D., Kaur, G. & Brar, S. K. Biodegradable green composites: It’s never too late to mend. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 1(30), 100482 (2021).

Thommes, M., Kaneko, K., Neimark, A. V., Olivier, J. P., Rodriguez-Reinoso, F., Rouquerol, J. & Sing, K. S. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC technical report). Pure Appl. Chem. 87(9–10), 1051–1069 (2015).

Wang, M., Yang, Z., Song, Z. & Wang, Q. Three-component one-pot synthesis of 2, 4, 6-triarylpyridines without catalyst and solvent. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 52(3), 907–910 (2015).

More, P. E., More, B. P., Bagal, H. L., Raskar, P. T., Shinde, N. S., & Kamble, V. T. . Zinc ferrite as an efficient and recyclable heterogeneous catalyst for the synthesis of 2, 4, 6-triarylpyridines under solvent-free conditions. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 59(2), 298–304 (2023).

Rekunge, D. S., Kale, I. A. & Chaturbhuj, G. U. An efficient, green solvent-free protocol for the synthesis of 2, 4, 6-triarylpyridines using reusable heterogeneous activated Fuller’s earth catalyst. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 15(11), 2455–2462 (2018).

Li, J., He, P. & Yu, C. DPTA-catalyzed one-pot regioselective synthesis of polysubstituted pyridines and 1, 4-dihydropyridines. Tetrahedron 68(22), 4138–4144 (2012).

Mao, Z. Y., Liao, X. Y., Wang, H. S., Wang, C. G., Huang, K. B. & Pan, Y. M. Acid-catalyzed tandem reaction for the synthesis of pyridine derivatives via C= C/C (sp3)–N bond cleavage of enones and primary amines. RSC Adv. 1(7), 13123–13129 (2017).

Xu, H., Zeng, J. C., Wang, F. J. & Zhang, Z. Metal-free synthesis of 2, 4, 6-trisubstituted pyridines via iodine-initiated reaction of methyl aryl ketones with amines under neat heating. Synthesis 49(8), 1879–1883 (2017).

Klemens, T., Świtlicka, A., Machura, B., Kula, S., Krompiec, S., Łaba, K. & Maćkowski, S. A family of solution processable ligands and their Re (I) complexes towards light emitting applications. Dyes Pigments 1(163), 86–101 (2019).

Zhao, Q., Li, L., Bi, D., Wang, H., Liu, D., Wei, Y. & Zhou, G. Manipulating intramolecular charge transfer in terpyridine derivatives towards turn-on fluorescence chemosensors for Zn2+. Chem. Asian J. 20(2), e202401247 (2025).

Tummalapalli, K., Vasavi, C. S., Munusami, P., Pathak, M. & Balamurali, M. M. Evaluation of DNA/Protein interactions and cytotoxic studies of copper (II) complexes incorporated with N, N donor ligands and terpyridine ligand. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1(95), 1254–1266 (2017).

Varaprasad, B., Kumar, K. B., Siddaiah, V., Shyamala, P. & Chinnari, L. Copper-catalyzed efficient access to 2, 4, 6-triphenyl pyridines via oxidative decarboxylative coupling of aryl acetic acids with oxime acetates. New J. Chem. 45(34), 15205–15209 (2021).

Han, J., Guo, X., Liu, Y., Fu, Y., Yan, R., & Chen, B. One-pot synthesis of benzene and pyridine derivatives via copper-catalyzed coupling reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 359(15), 2676–2681 (2017).

Gajaganti, S., Kumar, D., Singh, S., Srivastava, V. & Allam, B. K. A new avenue to the synthesis of symmetrically substituted pyridines catalyzed by magnetic nano–Fe3O4: methyl arenes as sustainable surrogates of aryl aldehydes. ChemistrySelect 4(31), 9241–9246 (2019).

Doan, S. H., Tran, N. K., Pham, P. H., Nguyen, V. H., Nguyen, N. N., Ha, P. T. & Phan, N. T.. A new synthetic pathway to triphenylpyridines via cascade reactions utilizing a new iron-organic framework as a recyclable heterogeneous catalyst. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 13, 2382–2389 (2019).

Ling, F., Shen, L., Pan, Z., Fang, L., Song, D., Xie, Z., & Zhong, W. B (C6F5) 3-catalyzed oxidative deamination/cyclization cascade reaction of benzylamines and ketones for the synthesis of 2, 4, 6-triarylpyridines. Tetrahedron Lett. 59(41), 3678–3682 (2018).

Guo, X., Lu, J., Wang, M., Chen, A., Hong, H., Li, Q. & Zhi, C. Synthesis of polyfunctional pyridines via copper-catalyzed oxidative coupling reactions. J. Org. Chem. 81(23), 11671–11677 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rima Heider Al Omari **:** Assistance in conducting research and assistance in obtaining analysis. Reza Mohammadi: Supervisor, article writer, and designer of the project. Subbulakshmi Ganesan: Assistance in conducting research and assistance in obtaining analysis. Shaker Al-Hasnaawei **:** Assistance in conducting research and assistance in obtaining analysis. Karthikeyan Jayabalan: Assistance in conducting research and assistance in obtaining analysis. Renu Sharma: Consulting in conducting laboratory work and conducting research. Aashna Sinha **:** Consulting in conducting laboratory work and conducting research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

The use of generative AI and disclosure

The authors are passionately integrating generative AI and AI-assisted technologies into their writing, merging creativity with groundbreaking innovation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Omari, R.H., Mohammadi, R., Ganesan, S. et al. Fe₃O₄@MCM-41-Cystine-ZnCl₂ nanocomposite in deep eutectic solvent: a sustainable and scalable catalytic system for three-component synthesis of triarylpyridines. Sci Rep 15, 45168 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28700-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28700-4