Abstract

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is associated with daytime dysfunction, impaired attention, longer reaction times, and other related issues, which may adversely affect the well-being and job performance of maternal and child health (MCH) nurses. However, the state of EDS among MCH nurses in China remains unclear, and few studies have focused on its associations with mental well-being and quality of work life (QWL). This study aims to investigate the prevalence of EDS among MCH nurses in China and explore its relationships with mental health (anxiety, depressive symptoms), and QWL. A multicenter cross-sectional study included 1426 MCH nurses selected from four hospitals in China. PSM was used to minimize the impact of potential confounders between the EDS and non-EDS groups. After PSM, binary logistic regression and multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to examine the associations of EDS with MCH nurses’ mental health and QWL, respectively. The results showed that 24.2% of MCH nurses experienced EDS. Additionally, EDS was positively associated with symptoms of anxiety (OR = 1.548, 95% CI: 1.115–2.151) and depression (OR = 1.814, 95% CI: 1.311–2.512), while being negatively associated with the QWL of MCH nurses (β = − 0.114, P = 0.002). To improve the mental health and QWL of MCH nurses, it is crucial to adjust work schedules and reduce drowsiness, which plays a vital role in stabilizing the nursing workforce and enhancing patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is characterized by the inability to maintain awake and alert during the daytime, which results in irrepressible drowsiness or sleepiness1. A meta-analysis has shown that the global prevalence of EDS among nurses is 32.2%2, which is higher than that in the general adult population3. This discrepancy may be linked to the inherent occupational attributes of nursing, particularly shift work, which disrupts sleep patterns and circadian rhythms, contributing to the development of EDS4. Compared with other sleep disorders such as poor sleep quality and insomnia, EDS is uniquely defined by impaired daytime function1,5,6; it undermines cognitive function, reaction times, attention span, and decision-making capabilities7,8, leading to reduced work efficiency and even adverse clinical events9. This impact is particularly consequential for nurses, who work 24-h shifts and are engaged in complex, high-risk tasks (e.g., surgical assistance, medication administration, injections, etc.) that demand sustained vigilance at all times. Notably, this issue has been insufficiently addressed in prior research, and the focus on maternal and child health (MCH) nurses is even more lacking.

MCH nurses serve a crucial function in protecting the health of women and children. As specialists caring for two vulnerable groups (women and children) across prenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum phases10, MCH nurses face heightened responsibility, chronic work stress, and frequent shift work11—factors that may further increase their risk of EDS. In addition, following the adjustment of China’s fertility policy, there has been an increase in cases of repeated caesarean deliveries, long interpregnancy intervals, and advanced maternal age12. This poses higher demands on the professional skills of MCH nurses, as the risk of pregnancy complications such as gestational diabetes mellitus and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, as well as adverse neonatal outcomes, has significantly increased13,14. Meanwhile, it also indirectly augments the workload of MCH nurses, leading to the occurrence of sleep disorders. Furthermore, given that EDS directly impairs the daytime alertness and cognitive sharpness critical to MCH nurses’ safety–critical duties (e.g., neonatal emergency response, maternal complication monitoring, etc.), investigating EDS in this specific population is both theoretically necessary and practically urgent.

Empirical research has shown that EDS is significantly associated with a variety of negative psychological health outcomes. Specifically, individuals exposed to EDS have higher levels of stress15 and increased mental fatigue16. A significant association has been observed between EDS and mental well-being, such as anxiety and depressive symptoms, in college students17, whereas research involving adult women has shown a different viewpoint18. However, there remains limited evidence regarding the relationship between EDS and mental health among MCH nurses, who often experience sleep disturbance and psychological issues19,20. In addiction, adverse occupational outcomes associated with EDS (e.g., decreased productivity, impaired work performance, etc.) may lead to difficulties aligning MCH nurses’ knowledge, skills, or abilities with the job requirements and exacerbating work-related stress21, which impact their evaluations of quality of work life (QWL)22, because QWL reflects well-being and overall quality of life in the workplace23. Nonetheless, the relationship between EDS and QWL among MCH nurses also remains unexplored.

Mental health problems, such as anxiety and depressive symptoms, can not only impact nurses’ well-being and health20 but also elevate the risk of medical errors24, causing a direct or indirect detrimental effect on women’s and children’s health. Similarly, poor QWL negatively influences the productivity and work performance of MCH nurses25,26, which directly impacts the quality of nursing care. Furthermore, the shortage of nurses is a widespread concern27, and unsatisfactory QWL has been linked to increased turnover intentions28, which exacerbates the insufficiency of nursing staff and negatively affects the functioning and development of MCH institutions. Thus, exploring the influence of EDS on mental health and QWL among MCH nurses is essential.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the prevalence of EDS among MCH nurses in China. Furthermore, the study aimed to eliminate potential confounding factors by utilizing propensity score matching (PSM) to explore the associations between EDS and mental health (anxiety and depressive symptoms) as well as QWL. It provides nursing managers with new insights for enhancing the mental health and QWL of MCH nurses, thereby improving the quality of nursing care and maintaining the sustainability of the nursing workforce.

Theoretical framework

Job Demands-Resources theory (J-DR) guided this study29. The model categorizes job characteristics into two core dimensions: job demands (e.g., shift work, emotional labor, workplace violence, etc.) and job resources (e.g., social support, peer support, training opportunities, etc.)30,31. High job demands continuously deplete individuals’ resources, triggering physical or psychological exhaustion and ultimately job burnout; in contrast, adequate job resources help employees cope with stress effectively, thereby enhancing their job satisfaction and performance29. According to this theory, EDS exacerbates the imbalance between job demands and resources. Specifically, the daytime dysfunction caused by EDS may lead to the depletion of psychological resources; this, in turn, exerts a negative impact on mental health and ultimately results in anxiety and depressive symptoms17. Furthermore, along with heightened resource depletion, EDS is linked to health risk behaviors, including decreased social and physical activity, which hinder the individual’s capacity to obtain and utilize new resources32,33, leading to a conflict between resource acquisition and depletion. Therefore, based on the theory mentioned above, the following hypothesis is proposed: EDS is positively correlated with anxiety and depressive symptoms and negatively correlated with the QWL among MCH nurses.

Methods

Study design and participants

This multicenter cross-sectional survey enrolled nurses working in 4 maternal and child health institutions in Fuzhou, China between December 2022 and January 2023, using convenience sampling. The sample size was calculated using the single population proportion formula: N = (Zα/2)2 × p(1 − p)/d2. Approximately 25% nurses reported the presence of EDS4,34. According to this criterion (α = 0.05; d = 0.03), 800 participants were required. We ultimately determined a minimum sample size of 889, accounting for a 10% non-response rate. MCH nurses who had both (a) achieved professional qualification certificates and (b) willingly participated in the study. And the following groups were excluded: (a) nursing students, retired nurses, and refresher nurses; (b) nurses with fewer than six months of professional experience; and (c) those that absent more than one month of work because of marriage, childbirth, illness , or other personal reasons.

Study instruments

Demographic questionnaire

The researcher designed a demographic questionnaire based on a literature review. The sociodemographic details of MCH nurses included their age, marital status, education level, and sex. Personal monthly income, professional rank, type of employment, weekly working hours, and frequency of night shifts were considered work-related variables.

The study also inquired about physical activity and sleep quality. Participants’ sleep quality over the preceding month was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)35. In the Chinese population, a total score greater than seven indicates poor sleep, while a score of seven or less suggests good sleep36. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the scale in this study was 0.752. Additionally, the Chinese version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF) was used to assess the participants’ physical activity levels over the previous week. The participants were categorized into three groups based on their physical activity level: low, moderate, and high37. This questionnaire has been validated with Chinese university students38.

Epworth sleepiness scale

The ESS is a self-administered questionnaire designed by Johns that evaluates a person’s tendency toward sleepiness in eight common situations39, such as sitting and reading, watching TV, and more. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = seldom, 2 = often, 3 = frequently), resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 24. An ESS score higher than 9 or 10 indicates the presence of EDS, with higher values reflecting more severe sleepiness. Although two distinct cutoffs (i.e., > 9 and > 10) are used to define EDS, a meta-analysis demonstrated that excluding studies employing the > 9 cutoff did not impact the pooled estimate of EDS prevalence among nurses2; thus, to avoid overdiagnosis and enhance result specificity, the cutoff of > 10 was ultimately adopted in this study. Therefore, the cutoff for EDS is ultimately set at 10 in this study. The Chinese version of the ESS has shown excellent reliability, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.81440. In our study, the scale’s Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.811.

Psychometric scales for depression, and anxiety

The Zung Self-Assessment Scale for Anxiety (SAS)41 and the Zung Self-Assessment Scale for Depression (SDS)42 were used to assess symptoms of anxiety and depression, respectively. Each scale consists of twenty items, with participant responses ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The normalized total score was calculated by multiplying the raw total score by 1.25, and higher scores indicate more severe mental health issues. The critical values for SAS and SDS were 50 and 5343, respectively, and the scales have been widely used among Chinese medical professionals44. The Cronbach’s α coefficients in this study were 0.850 for SAS and 0.805 for SDS.

The work-related quality of life-2 scale

The WRQOL-2 scale was used to assess work-related quality of life and was developed by Van Laar et al45. It was subsequently translated and revised into a Chinese version by Shao et al.46. The scale contains a total of 32 participant-scored entries in seven dimensions: working conditions (WCS), general well-being (GWB), control at work (CAW), employment evaluation of nurses (EEN), home-work interface (HWI), career satisfaction (JCS), and work at stress (SAW). A five-point Likert scale was used to rate each item (1 being “strongly disagree” and 5 being “strongly agree”). Notably, the dimension of SAW was the reverse entry, requiring a transformed score by subtracting 6 from the original entry score. The total score of the scale ranged from 32 to 160, with higher scores indicating a better QWL. The Chinese version of the scale was validated and found strong reliability and validity among mainland Chinese nurses (Cronbach’s α = 0.940)47. In our study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.960.

Data collection

Permission was obtained from the directors of the nursing departments of the four hospitals prior to the study. To ensure the authenticity and rigor of the data, uniform training was required for the four investigators from each hospitals to understand the purpose, the selection of the participants, and the implementation process of the study. The survey was completed anonymously via WenJuanXing, a widely used online survey platform in China. Before answering the questionnaire, participants were asked to read the permission form to ensure that they were fully informed about the study and aware that they could withdraw at any time for any reason.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS, version 27.0 and Stata, version 18.0. Propensity Score Matching (PSM) is a valuable statistical method in observational studies. Though it cannot address unmeasured confounders and may cause minor information loss, its ability to approximate the comparability of randomized trials remains pivotal—this is because PSM simulates randomized trials to balance confounding variable distribution, controlling confounding bias and reducing selection bias48. Specifically, it matches individuals with similar propensity scores (a value reflecting one’s exposure probability, derived by condensing multiple confounding variables) between the exposed and control groups48. Compared with regression models, PSM eliminates the need to prespecify the relationship forms between variables and achieves confounder balance through matching, which better reduces model dependence and bias, leading to more robust causal inference. In this study, PSM was used to adjust for potentially confounding variables between the EDS and non-EDS groups, including age, educational level, sex, marital status, physical activity, sleep quality, personal monthly income, professional rank, employment type, weekly working hours, and night shift frequency. Given the moderate sample size of this study and the categorical nature of all covariates, PSM was performed with a caliper value of 0.05, a 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching ratio, and logistic regression for propensity score estimation49. Independent t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables were used to compare the baseline characteristics between the EDS and non-EDS groups. The association between EDS and anxiety and depressive symptoms among MCH nurses was analyzed by conducting binary logistic regression analyses on the Post-matching data. Ratio ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the outcome variables. In order to evaluate the link between EDS and QWL, multiple linear regression analysis was implemented. The level of statistical significance was established at P < 0.05, and all statistical tests were two-sided.

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fujian Maternal and Child Health Hospital (No. 2022YJ071). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. For online survey consent, the first section of the questionnaire included the informed consent information. Participants had to click “I agree to participate” after reading it, confirming their consent before proceeding with the questionnaire. In this study, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 1510 questionnaires were distributed, out of which 1426 were considered valid after excluding incomplete data or apparent logical errors, and the effective recovery rate was 94.44%. The majority of MCH nurses were female (n = 1401, 98.2%), married (n = 766, 53.7%), and aged between 26 and 35 years (n = 579, 40.6%). In terms of educational level and professional rank, approximately 52.9% (n = 754) had a junior college degree, while 42.4% were senior nurses (n = 604). Most participants worked as contract employees (n = 952, 66.8%), and a large proportion reported rotating shift work (n = 1031, 72.3%) and working 36–40 h per week (n = 794, 55.7%). Moreover, around 44.5% of the participants reported engaging in a moderate level of physical activity (n = 634), and more than half of the participants reported experiencing poor sleep quality (n = 826, 57.9%).

Comparison of non-EDS and EDS groups before and after PSM

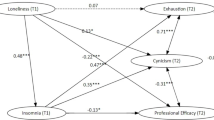

The study flowchart is shown in Fig. 1. Of these participants, 345 (24.2%) were assigned to the EDS group, and 1081 (75.8%) were assigned to the non-EDS group. After PSM, the sample size was reduced from 1426 to 676, with an average of 338 participants assigned to each group. The absolute standardized difference values of all variables were within 0.1 after matching, indicating a negligible difference between the EDS and non-EDS groups (Fig. 2). Figure 3 show the density distribution of propensity scores before and after matching, respectively, it can be seen that PSM significantly corrected the propensity score deviation between the treatment group and the control group, as the density distributions overlapped almost exactly. In addition, the observed covariates between the EDS and non-EDS groups after PSM did not differ significantly (P > 0.05, Table 1), making the two groups comparable.

Comparison of standard mean difference before and after PSM. 1, Age; 2, sex; 3, Educational level; 4, Marital status; 5, Employment type; 6, Professional rank; 7, Personal monthly income; 8, Night shift frequency; 9, Weekly working hours; 10, Physical activity; 11, Sleep Quality; PSM, propensity score matching; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Comparison of mental health (anxiety and depressive symptoms) and QWL between the EDS and non-EDS groups

The outcome data on mental health (anxiety and depressive symptoms) before and after matching are shown in Table 2. Before PSM, the results showed that the prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms among MCH nurses was 32.3% (461/1426) and 33.7% (480/1426), respectively. Additionally, the prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms among MCH nurses differed significantly between the EDS and non-EDS groups, both before and after PSM (P < 0.05).

The results indicated that the overall QWL of MCH nurses was moderate before PSM (122.10 ± 18.26), which remained stable after PSM (119.85 ± 18.13). Table 3 presents a comparison of overall QWL and its dimension scores among MCH nurses before and after PSM in EDS and non-EDS groups. Except for the dimension of working conditions (WCS), participants’ overall QWL and the scores of the other dimensions between the two groups showed significant differences both before and after PSM (P < 0.05).

Binary logistic regression analyses for anxiety and depressive symptoms

The results from the binary logistic analysis are presented in Table 4. MCH nurses with EDS were more likely to suffer from anxiety (odds ratios = 1.548, 95% confidence intervals: 1.115 to 2.151) and depressive symptoms (odds ratios = 1.814, 95% confidence intervals: 1.311 to 2.512) than those without EDS. In addition, MCH nurses with weekly working hours exceeding 46 h had an elevated likelihood of anxiety symptoms, while those with a night shift frequency of 1–5 per month were at a high risk of depressive symptoms; meanwhile, poor sleep quality was a common risk factor for both anxiety and depressive symptoms (all P < 0.05, Table 4).

Multiple linear regression analysis for the QWL

The results of the multiple linear regression of QWL Post-matching are presented in Table 5. The results revealed that MCH nurses with EDS are associated with significantly lower QWL (β = − 0.114, 95% CI = [− 6.724, − 1.530]). Moreover, more frequent night shifts (> 10 days/month), longer weekly working hours (≥ 36 h), and poor sleep quality were negatively associated with MCH nurses’ QWL. Instead, higher professional titles (associate advanced or advanced nurse) and moderate personal monthly income (3000–11,999 yuan) were positively associated with MCH nurses’ QWL (all P < 0.05, Table 5).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the prevalence of EDS among Chinese MCH nurses through a large multi-centre cross-sectional survey and examined its associations with mental health (anxiety and depressive symptoms) as well as QWL using PSM. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large-scale investigation of EDS among nurses in Chinese MCH institutions. Furthermore, to enhance the validity and reliability of the study results, we used PSM to control for the confounding effects of potential covariables. Based on the results of binary logistic analysis and multiple linear regression after PSM, EDS was significantly associated with MCH nurses’ anxiety and depressive symptoms as well as lower levels of QWL.

Approximately one-quarter of MCH nurses reported having EDS (24.2%), which is consistent with the findings of previous studies among nurses conducted in England (28%)34 and Japan (24.6%)4, while lower than that reported in relevant studies conducted in Istanbul (38.55%)50 and Ethiopia (53.52%)51. These similarities and differences across studies may be attributed to factors such as the special characteristics of nursing work, hospital management systems, and sociocultural environments. To ensure the continuity of nursing work, most nurses are required to work in shifts, which may lead to circadian rhythm disruption and thus exert a serious impact on their physical and mental health52. Terauchi et al. found that compared with the control group, the incidence of EDS among female nurses engaged in shift work was 1.92 times that of the latter4. Additionally, unreasonable scheduling, such as quick returns (less than 11 h off work between work shifts)53 and shifts longer than 12 hours54, is also significantly associated with higher rates of EDS among nurses. Therefore, it is essential for nursing managers to rationalize work assignments appropriately and ensure that nurses receive adequate rest between shifts. Notably, all participants were from grade-A tertiary hospitals in Fuzhou(with relatively sufficient resources and advanced management). Additionally, the city’s developed economy has fostered strong health awareness among residents. This heightened awareness facilitates the timely detection of sleep problems and encourages help-seeking behavior, which may account for the relatively lower EDS rate observed in this study. Besides, the participants of this study mainly consist of young nurses aged ≤ 35 years, most of whom hold senior nurse or higher professional ranks. Their stronger sleep recovery capacity, coupled with richer clinical experience and higher professional skills (both of which help mitigate work stress), may also be important reasons for the lower EDS prevalence observed in our study55.

As hypothesized, MCH nurses with EDS were 1.814 times more likely to have depressive symptoms and 1.548 times more likely to have anxiety symptoms than those without EDS. Similarly, a prospective study involving 2787 Chinese adolescents found that baseline EDS predicted new onsets of depression and anxiety at follow-up17. This may be attributed to the interference of EDS with the secretion of specific neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin and norepinephrine), which exacerbates negative emotions and elevates the risk of developing psychopathological problems56,57. Moreover, nurses who experience high levels of drowsiness often exhibit negative reactions to stressors, which may further contribute to mental health issues58. This indicates that nursing managers should reasonably arrange shift schedules and allocate human resources to reduce EDS-related psychological stressors. Besides, light and temperature modulation, music and aromatherapy, yoga, sleep education, and psychotherapy are effective in reducing sleep and psychological harms caused by shift work59. Notably, a longitudinal study conducted in Sweden found that anxiety and depression also increased the risk of developing EDS over a 10-year period60. This suggests that there may be a bidirectional relationship between EDS and mental health, which indicates that future research could be conducted to explore the causal relationship between them among MCH nurses. A network analysis found that anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders often coexist among Chinese nurses61. Given that, nursing managers should identify core symptoms and shift from “single intervention” to "integrated and differentiated intervention" to break the vicious cycle and promote nurses’ overall health.

This study demonstrated that individuals who report EDS have lower QWL levels among MCH nurses in Fujian Province, which aligns with our hypothesis. Similarly, Li et al. found that the sleep quality of MCH nurses was negatively correlated with their QWL19. Besides, among the seven dimensions of sleep quality, “daytime dysfunction” showed the strongest negative correlation with QWL. In addition, a previous study in Jordan showed that nurses with good sleep quality were approximately 25 times more likely to have an excellent QWL than those with poor sleep quality62. A systematic review pointed out nurses’ QWL is mainly influenced by three dimensions: personal (socio-demographic), occupational, and psychological63. Notably, in terms of the occupational dimension, factors such as long working hours, high night shift frequency, and severe work-related stress have all been proven to be associated with nurses’ poor sleep quality64, and this suggests that sleep problems may be a key mediating variable between occupational factors and QWL. Therefore, providing a favorable work environment (e.g., optimizing shift schedules, reducing workload, and improving nurses’ compensation, etc.) may be the most direct and effective way to promote nurses’ sleep health as well as improve their QWL.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, establishing a causal association between EDS and mental health, including QWL, is difficult due to the cross-sectional research design. To address this issue, more extensive longitudinal research on the subject is required. Secondly, all participants were recruited from four tertiary hospitals in a single province. Regional differences in healthcare infrastructures, socioeconomic contexts, occupational environment and work-related stress may limit the findings’ representativeness and generalizability to all Chinese MCH nurses. Thirdly, while this study controlled for some observable confounders, there may still be unobserved confounders that could affect the generalization of the results. Finally, all explanatory variables were self-reported through questionnaires. Given the sensitivity of mental health topics, MCH nurses may have under or overreported symptoms due to personal or institutional concerns, making the data potentially subject to recall bias, social desirability bias, or demand effects, which could affect the validity of the findings.

Conclusion

This study provides new insights for better understanding the associations between EDS, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and QWL among MCH nurses by using propensity score matching. This study has revealed that MCH nurses with EDS are at a higher risk of experiencing anxiety and depressive symptoms, and their QWL tends to be unsatisfactory compared to those without EDS. These findings emphasize the importance of focusing on the daytime functions of MCH nurses and providing organizational support to reduce the occurrence of EDS. This is essential for enhancing the mental well-being of MCH nurses and their QWL, which in turn helps retain the nursing staff and provides high-quality care to patients.

Implications for nursing management

This study offers valuable implications for MCH institutions to enhance nurses’ mental health and quality of work life by improving their daytime function, and these insights further provide important practical guidance for nursing management and policymakers. First, it is essential to establish scientific work schedules (e.g., avoiding frequent shift rotations and excessively long working hours, and ensuring adequate rest periods between shifts, etc.). Second, regular lectures on sleep health and mental well-being should be organized to equip nurses with self-regulation skills and strengthen peer support; additionally, nursing administrators could set up specialized psychological and sleep support teams to provide professional counseling and intervention services for MCH nurses. Given that sleep and mental health issues often coexist, nursing managers should emphasize personalized management and identify core symptoms of individuals and shift from a “single intervention” approach to an "integrated and differentiated intervention" model to promote nurses’ overall health. Finally, creating a favorable work environment—such as reducing workplace noise, optimizing nurses’ compensation, and enhancing humanistic care—also plays a pivotal role in improving MCH nurse’ physical and mental health as well as their quality of work life.

Data availability

The data that support the findings from this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sateia, M. J. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: Highlights and modifications. Chest 146, 1387–1394 (2014).

Gu, K., Chen, H., Shi, H. & Hua, C. Global prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Nurs. Rev. 72, e13087 (2025).

Hayley, A. C. et al. Prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness in a sample of the Australian adult population. Sleep Med. 15, 348–354 (2014).

Terauchi, M., Ideno, Y. & Hayashi, K. Effect of shift work on excessive daytime sleepiness in female nurses: Results from the Japan nurses’ health study. Ind. Health 62, 252–258 (2024).

Ohayon, M. et al. National sleep foundation’s sleep quality recommendations: First report. Sleep Health 3, 6–19 (2017).

Perlis, M. L. et al. Insomnia. Lancet 400, 1047–1060 (2022).

Scott, L. D., Arslanian-Engoren, C. & Engoren, M. C. Association of sleep and fatigue with decision regret among critical care nurses. Am. J. Crit. Care 23, 13–23 (2014).

Silva Gomes, V. & Cardoso Júnior, M. M. The effect of sleepiness in situation awareness: A scoping review. Work 78, 641–655 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness in general hospital nurses: Prevalence, correlates, and its association with adverse events. Sleep Breath. 23, 209–216 (2019).

Biro, M. A. What has public health got to do with midwifery? Midwives’ role in securing better health outcomes for mothers and babies. Women Birth. 24, 17–23 (2011).

Ye, Q., Zhong, K., Yuan, L., Huang, Q. & Hu, X. “High-stress, conscientiousness and positive coping”: Correlation analysis of personality traits, coping style and stress load among obstetrics and gynecology female nurses and midwives in twenty-one public hospitals in Southern China. BMC Womens Health. 25, 116 (2025).

Tatum, M. China’s three-child policy. Lancet 397, 2238 (2021).

Kongwattanakul, K., Thamprayoch, R., Kietpeerakool, C. & Lumbiganon, P. Risk of severe adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes in deliveries with repeated and primary cesarean deliveries versus vaginal deliveries: a cross-sectional study. J. Pregnancy. 2020, 9207431 (2020).

Xiu, S. et al. Association between interpregnancy interval and adverse perinatal outcomes according to maternal age in the context of China’s two-child policy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 25, 81 (2025).

Garcia-Tudela, A., Simonelli-Munoz, A. J., Gallego-Gomez, J. I. & Rivera-Caravaca, J. M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on stress and sleep in emergency room professionals. J. Clin. Nurs. 32, 5037–5045 (2023).

Chen, S., Wu, H., Sun, M., Wei, Q. & Zhang, Q. Effects of shift work schedules, compensatory sleep, and work-family conflict on fatigue of shift-working nurses in Chinese intensive care units. Nurs. Crit. Care 28, 948–956 (2023).

Luo, C., Zhang, J., Chen, W., Lu, W. & Pan, J. Course, risk factors, and mental health outcomes of excessive daytime sleepiness in rural Chinese adolescents: A one-year prospective study. J. Affect. Disord. 231, 15–20 (2018).

Hayley, A. C. et al. The relationship between excessive daytime sleepiness and depressive and anxiety disorders in women. Aust. N Z J Psychiatry 47, 772–778 (2013).

Li, J. N. et al. Exploring the associations between chronotype, night shift work schedule, quality of work life, and sleep quality among maternal and child health nurses: A multicentre cross-sectional study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2023, 1–12 (2023).

Yang, J. et al. Risk factors and consequences of mental health problems in nurses: A scoping review of cohort studies. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 33, 1197–1211 (2024).

Mao, Y., Raju, G. & Zabidi, M. A. Association between occupational stress and sleep quality: A systematic review. Nat. Sci. Sleep 15, 931–947 (2023).

Akter, N., Akkadechanunt, T., Chontawan, R. & Klunklin, A. Factors predicting quality of work life among nurses in tertiary-level hospitals, Bangladesh. Int. Nurs. Rev. 65, 182–189 (2018).

Hsu, M. Y. & Kernohan, G. Dimensions of hospital nurses’ quality of working life. J. Adv. Nurs. 54, 120–131 (2006).

Song, Q., Tang, J., Wei, Z. & Sun, L. Prevalence and associated factors of self-reported medical errors and adverse events among operating room nurses in China. Front. Public Health 10, 988134 (2022).

Nayeri, N. D., Salehi, T. & Noghabi, A. A. Quality of work life and productivity among Iranian nurses. Contemp. Nurse 39, 106–118 (2011).

Al-Dossary, R. N. The relationship between nurses’ quality of work-life on organizational loyalty and job performance in saudi arabian hospitals: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 10, 918492 (2022).

World H, & Organization. State of the world’s nursing 2020: Investing in education, jobs and leadership. (2020).

Poku, C. A. et al. Quality of work-life and turnover intentions among the Ghanaian nursing workforce: A multicentre study. PLoS ONE 17, e0272597 (2022).

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F. & Schaufeli, W. B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 499–512 (2001).

Bakker, A. B. & Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: state of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 22, 309–328 (2007).

Demerouti, E. & Bakker, A. B. The job demands-resources model: Challenges for future research. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 37, 974–982 (2011).

Holding, B. C. et al. Sleepiness, sleep duration, and human social activity: An investigation into bidirectionality using longitudinal time-use data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 117, 21209–21217 (2020).

Andrianasolo, R. M. et al. Leisure-time physical activity and sedentary behavior and their cross-sectional associations with excessive daytime sleepiness in the French SU.VI.MAX-2 study. Int. J. Behav. Med. 23, 143–152 (2016).

Westwell, A., Cocco, P., Van Tongeren, M. & Murphy, E. Sleepiness and safety at work among night shift NHS nurses. Occup. Med. 71, 439–445 (2021).

Buysse D J, Reynolds C F, 3rd, Monk T H, Berman S R, Kupfer D J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28, 193–213 (1989).

Liu, X. et al. Reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index. Chin. J. Psychiatry 29, 103–107 (1996).

Macfarlane, D. J., Lee, C. C., Ho, E. Y., Chan, K. L. & Chan, D. T. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of IPAQ (short, last 7 days). J. Sci. Med. Sport. 10, 45–51 (2007).

Qu, N. N. & Li, K. J. Study on the reliability and validity of international physical activity questionnaire (Chinese Vision, IPAQ). Chin. J. Epidemiol. 25, 265–268 (2004).

Johns, M. W. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 14, 540–545 (1991).

Peng, L. L. et al. Reliability and validity of the simplified Chinese version of Epworth sleepiness scale. Chin. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 46, 44–49 (2011).

Zung, W. W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 12, 371–379 (1971).

Zung, W. W. A self-rating depression scale. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 12, 63–70 (1965).

Gong, Y. et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and related risk factors among physicians in China: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 9, e103242 (2014).

Lu, G. et al. Prevalence of depression and its correlation with anxiety, headache and sleep disorders among medical staff in the Hainan Province of China. Front. Public Health. 11, 1122626 (2023).

Easton, S. V. L. D. User Manual for the Work-Related Quality of Life (WRQoL) Scale: A Measure of Quality of Working Life 2nd edn. (University of Portsmouth, 2018).

Shao, Y., Liao, S., Zhong, H., Bu, S. & WEN, R.,. Work-related quality of life scale among Chinese nurses: Evaluation of the reliability and validity. J. Nurs. Sci. 29, 1–3 (2014).

Li, P., Wang, Y. & Zhang, M. Translation and validation of the work-related quality of life scale (WRQoLS-2) in a nursing cohort. Contemp. Nurse. 58, 435–445 (2022).

Kane, L. T. et al. Propensity score matching: A statistical method. Clin. Spine Surg. 33, 120–122 (2020).

Austin, P. C. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm. Stat. 10, 150–161 (2011).

Çolak, M. & Esin, M. N. Factors affecting the psychomotor vigilance of nurses working night shift. Int. Nurs. Rev. 71, 84–93 (2024).

Adane, A., Getnet, M., Belete, M., Yeshaw, Y. & Dagnew, B. Shift-work sleep disorder among health care workers at public hospitals, the case of Sidama national regional state, Ethiopia: A multicenter cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 17, e0270480 (2022).

Rosa, D., Terzoni, S., Dellafiore, F. & Destrebecq, A. Systematic review of shift work and nurses’ health. Occup. Med. 69, 237–243 (2019).

Eldevik, M. F., Flo, E., Moen, B. E., Pallesen, S. & Bjorvatn, B. Insomnia, excessive sleepiness, excessive fatigue, anxiety, depression and shift work disorder in nurses having less than 11 hours in-between shifts. PLoS ONE 8, e70882 (2013).

Arbour, M. et al. Factors that contribute to excessive sleepiness in midwives practicing in the United States. J. Midwifery Womens Health 64, 179–185 (2019).

Xiao, Q. et al. Determinants of sleep quality and their impact on health outcomes: A cross-sectional study on night-shift nurses. Front. Psychiatry 15, 1506061 (2024).

Chellappa, S. L., Schroder, C. & Cajochen, C. Chronobiology, excessive daytime sleepiness and depression: Is there a link?. Sleep Med. 10, 505–514 (2009).

Walker, M. P. & van der Helm, E. Overnight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processing. Psychol. Bull. 135, 731–748 (2009).

Topal Kilincarslan, G., Ozcan Algul, A. & Gordeles, B. N. Sleep quality, coping, and related depression: A cross-sectional study of Turkish nurses. Int. Nurs. Rev. 71, 895–903 (2024).

Inchingolo, A. D. et al. Guidelines for reducing the adverse effects of shift work on nursing staff: a systematic review. Healthcare 13, 2148 (2025).

Theorell-Haglöw, J., Åkerstedt, T., Schwarz, J. & Lindberg, E. Predictors for development of excessive daytime sleepiness in women: A population-based 10-year follow-up. Sleep 38, 1995–2003 (2015).

Chen, F. et al. Relationships among sleep quality, anxiety, and depression among Chinese nurses: A network analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 389, 119587 (2025).

Alzoubi, M. M. et al. Assessment of the quality of nursing work life and its related factors among critical care nurses. Front. Public Health 12, 1305686 (2024).

Sibuea, Z. M., Sulastiana, M. & Fitriana, E. Factor affecting the quality of work life among nurses: A systematic review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 17, 491–503 (2024).

Dong, H., Zhang, Q., Zhu, C. & Lv, Q. Sleep quality of nurses in the emergency department of public hospitals in China and its influencing factors: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 18, 116 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the MCH nurses participating in the study. Additionally, thank you to the proofreaders and editors for their valuable assistance.

Funding

This study was funded by Social Development Guiding Project Fund from Fujian Science and Technology Department (No.2023Y0055) and Scientific and Technological Initial Project Fund from Fujian Maternity and Health Hospital (No. YCXH 22-06).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.P.W. and J.N.L. contributed equally to this paper and are joint first author. Y.P.W. and J.N.L. contributed to study design, data curation, data processing, data analysis, manuscript drafting and writing—review & editing. X.M.J. contributed to study design, manuscript drafting and revision. Q.X.Z. contributed to study design, data analysis, and manuscript drafting. X.Q.C. contributed to study design, data curation, and manuscript drafting. Y.Q.P. contributed to study design, data analysis, and manuscript revision. X.X.G. contributed to study design, data processing, and manuscript revision. M.H.L. and C.L.X. contributed to data curation and manuscript drafting. J.Y.L. and Q.L.W. contributed to data curation and manuscript revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Li, J., Jiang, X. et al. Association of excessive daytime sleepiness with anxiety, depressive symptoms, and quality of work life among maternal and child health nurses. Sci Rep 16, 43 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28720-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28720-0