Abstract

This pilot study investigates the learning effect in repeated trials of the Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test in adults with different levels of physical fitness. Twenty physically active (PAS) and non-physically active subjects (NAS) participated in the study (age 19.9 ± 1.6 years, height 174.5 ± 8.1 cm, body mass 66.5 ± 8.2 kg, and BMI 21.8 ± 1.6 kg/m²). They repeatedly performed the Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test (Level 1) once a week until performance plateaued. Maximal heart rate was analyzed in three one-minute intervals after the test was completed. PAS completed 3.1 ± 1.28 and NAS completed 2.7 ± 0.15 trials. Performance level significantly improved from the initial to the final trial in both PAS (from 14.5 ± 1.1 to 15.2 ± 1.1, p = .006) and NAS (from 13.0 ± 1.0 to 13.5 ± 0.9, p = .008). Similarly, the distance covered significantly increased in both the PAS (from 588.5 ± 317.4 m to 748.7 ± 373.4 m, p = .001) and the NAS (from 360.0 ± 175.9 m to 432.0 ± 188.4 m, p = .003). Maximal oxygen uptake also significantly increased in the PAS (from 41.6 ± 1.8 ml/kg/min to 43.3 ± 2.4 ml/kg/min, p = .005) as well as in the NAS (from 39.5 ± 1.5 ml/kg/min to 40.1 ± 1.6 ml/kg/min, p = .003). However, there were no significant changes in maximal heart rate between the first and last trials in either group. These findings indicate a significant learning effect in the Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test (Level 1) over 3 trials, regardless of the subjects’ level of physical fitness. However, this may bias the results, and therefore, practice trials are recommended before testing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Level 1 (YYIR1) assesses the ability to perform high-intensity exercise repeatedly interspersed by short recovery intervals. This makes it particularly suitable for intermittent sports1,2. Its popularity among strength and conditioning professional sstems from its capacity to assess both aerobic and anaerobic fitness components, along with recovery capacity during high-intensity intermittent activities 3. Given its resemblance to the physiological demands of team sports, the YYIR1 demonstrates strong ecological validity4. Although maximal oxygen uptake (VO₂max) is a strong predictor (r =.70–0.74) of YYIR1 performance, other variables such as acid–base regulation, VO₂ kinetics, maximal aerobic speed, and relative exercise intensity also contribute meaningfully to performance45,

The YYIR1 has been validated across various populations and sport settings. A systematic review encompassing 248 studies and 9,440 participants reported normative data by sport and competition level, with the YYIR1 accounting for 57.7% of all Yo-Yo test applications6. The test also demonstrates high discriminatory power, especially when distinguishing between performance levels in team sports such as soccer and basketball7.

Despite its widespread adoption and generally good-to-excellent test–retest reliability8, several methodological concerns remain. Notably, many studies do not report the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which limits comparisons9. Moreover, the potential for learning effects, defined as performance improvements stemming from test familiarity rather than physiological adaptation10, has received relatively little attention. This oversight is critical, as such effects may influence the validity of baseline assessments and the interpretation of longitudinal changes. Most YYIR1 research has focused on soccer players of varying ages, competition levels, and positions111,, 12. However, limited information is available on the learning effects in broader populations, such as physically active adults, despite the growing use of field tests in non-elite and recreational settings.

Comparative studies of intermittent fitness tests have shown that response to training and familiarization may vary. For instance, although both the YYIR1 and the 30 − 15 Intermittent Fitness Test are sensitive to training adaptations, they may emphasize different physiological components13, indicating that each test’s unique learning profile must be understood. Modifications to test protocols can also influence familiarity and performance. In rugby players, a prone-start modification of the YYIR1 produced different performance outcomes than the standard version, reinforcing the importance of protocol consistency and familiarization14.

These findings have important implications. If initial performance gains are primarily due to learning, this may compromise the validity of baseline or early follow-up measurements, leading to overestimation of training effects. Therefore, determining the duration and magnitude of the learning effect is essential for the development of standardized and reliable testing procedures. Our previous case study showed that the distance covered in the first set of measurements increased by 15.4%, which corresponds to a 4.6% increase in the level achieved. The distance covered in the second set of measurements also increased by 17.9%, which corresponds to a 5.5% increase in the level achieved. The participant’s performance changes fell outside of the SWC and the CV, but not the 2CV during both sets of measurements15. These improvements in YYIR1 performance may be ascribed to practice with repeated attempts of the test by improving running technique at the turning point and/or by simply increasing the linear speed15.

In this work, we would like to build on previous results, but with a larger sample with varying levels of physical fitness. We were interested in how many repeated trials and to what extent performance on this test would improve. Therefore, the aim of this pilot study was to investigate the learning effect of repeated Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test (Level 1) in adults with different levels of physical fitness. Based on our previous experience, we assume that there will be a significant improvement in the YYIR1 distance covered and corresponding performance level regardless of the subjects’ level of physical fitness.

Methods

Study design

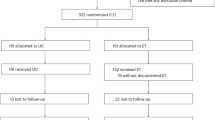

This study employed a repeated-measures observational design to investigate learning effects in the Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Level 1 (YYIR1) among university students with differing physical activity levels. This design allowed for the evaluation of performance progression across multiple weekly trials, with a focus on identifying the point at which performance plateaued and whether this was influenced by baseline fitness status. Sample size estimation was informed by a prior case study15 examining performance changes during repeated administrations of the YYIR1. The observed improvements in VO₂max and distance covered yielded large effect sizes (Cohen’s d ≈ 1.6–1.8). Based on these estimates, a power analysis (α = 0.05, power = 0.80) indicated that approximately 8 participants per group would be sufficient to detect significant between-group differences. To account for variability and ensure adequate power, a sample size of 10 participants per group was adopted. This size is considered appropriate for a pilot or exploratory study employing a within-subject, repeated-measures design.

Participants

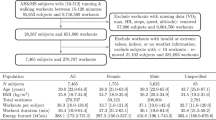

Twenty volunteer university students were recruited for this study and categorized into two groups: physically active subjects (PAS) and non-physically active subjects (NAS). The classification was based on responses to the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). For each participant, responses regarding the frequency (days per week) and duration (minutes per day) of physical activity across work, transport, and leisure domains were converted into MET-minutes per week. Participants who achieved ≥ 600 MET-minutes per week were classified as PAS, while those below this threshold were designated as NAS16. Inclusion criteria were healthy individuals without musculoskeletal issues, a normal body composition based on BMI, aged between 18 and 22 years, and no prior experience with theYYIR1 test . Exclusion criteria included incomplete experimental protocol or any illness during the study period. The average characteristics for the PAS group were as follows: age 20.6 ± 1.26 years, height 175.9 ± 9.57 cm, body mass 69.7 ± 9.99 kg, and BMI 22.42 ± 1.5 kg/m², and for the NAS group: age 19.2 ± 1.55 years, height 173.1 ± 6.23 cm, body mass 63.3 ± 4.17 kg, and BMI 21.16 ± 1.6 kg/m².

All participants provided written informed consent after being fully informed about the purpose and procedures of the study. The study procedures adhered to the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments, and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Physical Education and Sports, Comenius University in Bratislava (approval no. 2/2023, dated 7 February 2023).

Procedure

Participants were instructed to refrain from any physical activity for 48 h before testing and to avoid introducing additional physical training during the testing period. The YYIR1 was conducted once per week at the same time and on the same day to maintain consistency and continued until participants no longer showed performance improvements. Specifically, testing was repeated weekly until participants reached a performance plateau, defined as achieving the same performance level on two consecutive trials. The trial at which this plateau was first observed was designated as the “last trial” and was used for comparison with the first trial in subsequent analyses. They were advised not to consume large meals within three hours of the test and were encouraged to stay well-hydrated. Participants were also asked to report how they felt (e.g., sick or tired). Before the YYIR1, participants completed a standardized warm-up consisting of two minutes of jogging, two minutes of dynamic stretching, and two minutes of athletic running drills. Detailed instructions on the test procedure were also provided. To familiarize themselves with the test, participants performed the first two shuttle runs before the initial measurement.

The YYIR1 involves repeated 2 × 20-meter shuttle runs at progressively increasing speeds, interspersed with 10-second recovery periods, and continues until the participant reaches voluntary exhaustion. Participants were required to maintain synchronization with the audio recording, completing each 20-meter shuttle run in time with the beeps. They began each run with one foot behind the starting line, turned at the beep signal, and returned to the starting point, ensuring full completion of each 40-meter interval. Active recovery—walking or jogging—was permitted during the 10-second intervals between runs. The test commenced at a speed of 10.0 km/h, increasing to 12 km/h, then 13 km/h, and subsequently in increments of 0.5 km/h. Performance was recorded as the level and total distance covered in the last successfully completed shuttle15. Maximal oxygen uptake (VO₂max, mL·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹) was estimated using the equation proposed by Bangsbo et al. 2, calculated as VO₂max = (Distance run in meters × 0.0084) + 36.4. Heart rate was continuously monitored during the test using the Polar Team Pro system (Polar Electro, Kempele, Finland). Maximum heart rate was analyzed post-test, followed by three one-minute seated recovery intervals. During this time, participants were instructed to remain silent and focus on recovery.

Statistical analysis

Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test due to the small sample size, and homogeneity of variances was verified using Levene’s test. To assess test–retest consistency, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated as ICC(3,1) (two-way mixed-effects model, single measures, consistency). ICC values were interpreted as: <0.50 poor, 0.50–0.75 moderate, 0.75–0.90 good, and > 0.90 excellent reliability17. Performance plateau was defined as the point at which participants failed to improve their achieved level in theYYIR1 test between consecutive trials. Testing was repeated weekly until the level attained remained unchanged on two consecutive occasions. The number of trials required to reach this plateau (a discrete, non-normally distributed variable) was recorded for each participant and compared between fitness groups using the Mann–Whitney U test. Effect size for this comparison was calculated as r = Z/√N and interpreted as small (0.10), medium (0.30), or large (0.50)18. For the remaining outcomes (performance level, maximal heart rate, heart rate at 1, 2 and 3 min post-YYIR1, estimated VO₂max, and distance covered), which met parametric assumptions, a mixed 2 × 2 ANOVA (Group × Trial: first vs. last) was performed. Assumptions for the ANOVA (normality of residuals and homogeneity of variances) were checked; sphericity was not applicable because the repeated factor had only two levels. Partial eta squared (η²) was reported as the ANOVA effect-size measure (small 0.01, medium 0.06, large 0.14)19. To determine whether maximal effort was achieved during familiarization, achieved HRmax was compared to age-predicted HRmax (220 - age) using paired t-tests for both the first and last trials within each group. Normality of the paired differences was confirmed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Cohen’s d was calculated as the effect size measure (small 0.20, medium 0.50, large 0.80). Additionally, the coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated for each variable across trials to provide a measure of within-subject variability and test–retest reliability. Given the exploratory nature of this pilot study, no adjustments for multiple comparisons were applied across the seven dependent variables to maximize sensitivity. Nevertheless, this increases the risk of type I error and is acknowledged as a study limitation. All analyses were conducted in SPSS version 26 and statistical significance was set at p <.05.

Results

The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for all variables indicated excellent reliability in both the PAS and NAS. Specifically, ICC values ranged from 0.903 to 0.976 in the NAS and from 0.909 to 0.974 in the PAS. These results support the internal consistency and stability of the performance measures used in the study ( Table 1).

For the performance level variable, a repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant main effect of group, F(1, 9) = 8.85, p =.016, partial η² = 0.496, and a significant effect of trial, F(1, 9) = 32.48, p <.001, partial η² = 0.783. However, the interaction between group and trial was not significant. Post hoc comparisons revealed significant improvements from trial 1 to trial 2 in both the NAS (mean difference = + 0.48, 95% CI [0.16, 0.80], p =.008) and PAS (mean difference = + 0.67, 95% CI [0.25, 1.09], p =.006).

For maximal heart rate, a significant main effect of group was found, F(1, 9) = 5.25, p =.048, partial η² = 0.369. No significant effects were observed for trial or the group × trial interaction. Pairwise comparisons showed no significant changes between pre- and post-test values in the NAS (mean difference = − 0.10, 95% CI [− 4.08, 4.28], p =.958) or PAS (mean difference = + 3.40, 95% CI [− 2.36, 9.16], p =.215).

Regarding heart rate 1, 2 and 3 min after YYIR1, no significant main effects or interaction effects were detected in any of the analyses. Post hoc comparisons confirmed no significant differences between the first and last trials in either group (all 95% CIs included zero) Table( 2).

For maximal oxygen uptake, the analysis revealed significant main effects of trial (F(1, 9) = 24.43, p =.001, partial η² = 0.731) and group (F(1, 9) = 8.46, p =.017, partial η² = 0.485), as well as a significant interaction (F(1, 9) = 5.30, p =.047, partial η² = 0.371). Both groups showed significant increases from baseline to the final test (NAS: mean difference = + 0.60, 95% CI [0.27, 0.94], p =.003; PAS: mean difference = + 1.79, 95% CI [0.71, 2.88], p =.005).

For distance covered, there was a significant main effect of trial, F(1, 9) = 35.59, p <.001, partial η² = 0.798). No significant effects were found for group or the group × trial interaction. Pairwise comparisons showed a significant increase in distance covered in both the NAS (mean difference = + 72.00 m, 95% CI [31.99, 112.01], p =.003) and PAS (mean difference = + 160.20 m, 95% CI [80.64, 239.77], p =.001).

To assess baseline differences in performance between groups, a Mann–Whitney U test was conducted, revealing no statistically significant differences (U = 44.5, p =.649) and a negligible effect size (r =.102).

An analysis of key performance variables using the coefficient of variation (CV) was conducted across two trials in both the NAS and PAS. Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, and CVs for all measured variables. In both groups, performance level, VO₂max, and distance covered showed moderate to large increases between the first and second trials. Maximal heart rate remained largely stable, with only small changes across trials. Heart rate at 1 min post-test exhibited small to moderate increases, while heart rate at 2 min post-test showed small to moderate variations. Heart rate at 3 min post-test presented minor changes, with slight increases in NAS and minor decreases in PAS. The CVs provide information on the within-group variability for each variable across trials.

To assess whether each test was maximal, achieved HRmax was compared to age-predicted HRmax (220-age) using paired t-tests. In the NAS group, achieved HRmax during the first trial (191.0 ± 5.5 bpm) was significantly lower than predicted HRmax (199.4 ± 1.8 bpm) (t = −4.676, p =.001, d = 1.52), and remained significantly lower in the last trial (190.9 ± 7.0 bpm) (t = −3.569, p =.006, d = 1.21). Similarly, in the PAS group, achieved HRmax during the first trial (182.5 ± 11.5 bpm) was significantly lower than predicted HRmax (198.5 ± 2.5 bpm) (t = −4.110, p =.003, d = 1.39), and remained significantly lower in the last trial (185.9 ± 7.6 bpm) (t = −5.040, p <.001, d = 1.66). Despite these statistical differences from age-predicted values, participants in both groups achieved > 91% of predicted HRmax across all trials, suggesting that near-maximal effort was attained during tests.

Discussion

Our findings showed a significant learning effect with repeated trials of the YYIR1 with an interval of one week (over 3 trials), regardless of the subjects’ level of physical fitness. More specifically, the performance level in the YYIR1 improved significantly with repeated trials in physically active (4.8%) and non-physically active subjects (3.8%). In addition, the distance covered in the YYIR1 improved significantly with repeated trials in physically active (27.2%) and non-physically active subjects (20.0%). Also, the maximal oxygen uptake in the YYIR1 improved significantly with repeated trials in physically active (4.1%) and non-physically active subjects (1.5%). Although these changes in the performance level and maximal oxygen uptake were relatively small in magnitude (< 5%), they exceeded the typical within-subject variability observed in the YYIR1 (as indicated by the coefficient of variation). It is therefore likely that they represent true improvements rather than random fluctuation. However, there were no significant changes in maximal heart rate between the first and last trials in either group.

The greater improvement in performance level (4.8% vs. 3.8%), distance covered (27.2% vs. 20.0%), and maximal oxygen uptake (4.1% vs. 1.5%) on repeated trials of the YYIR1 test in the group of physically active than in the inactive subjects can be ascribed to their previous experience with this exercise. Intermittent running is part of many team sports (soccer, basketball, etc.), which are among the most common forms of physical activity for university students. Therefore, it is not a new exercise for them, and this movement is performed more effectively and consistently compared to physically inactive students. It is a skill that physically active subjects have learned in the autonomous phase of motor learning. It is therefore very likely that these individuals performed this task largely automatically with minimal demands on cognitive processing. They primarily contract the muscles involved in this specific movement, and therefore the improvement in performance on repeated trials is greater compared to those who are not familiar with this type of physical activity. Therefore, the dynamic stereotype of this exercise is learned much better by them than by physically inactive individuals.

On the other hand, intermittent running was not previously performed by physically inactive subjects, and therefore this motor skill is in the cognitive stage of motor learning. This novel task was inconsistent and inefficient, requiring significant attention in individuals with no experience in this type of physical activity. Many muscles contract during this exercise, although not all of them are involved in straight and changing direction of running, but they can relieve the work of the muscles involved. This is a new skill for them, and therefore the improvement in performance with repeated trials was smaller compared to physically active subjects. As they become more familiar with intermittent running, their movement should also become more efficient.

Thus, our findings clearly indicate a learning effect in the YYIR1 test, with significant performance improvements observed in the three initial trials in both groups. It is important to note that our analysis compared the first trial with the last trial at which each participant reached their individual performance plateau, rather than using a fixed trial number (e.g., Trial 2 or Trial 3) for all participants. These improvements align with previous research 15, which highlights how test-specific familiarity with repeated trials and improved pacing strategies can enhance performance in the Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test. They may be attributed to practice with repeated trials of this test by increasing linear velocity and/or improving running technique at the turning point 15. Since the majority of this test consists of linear sprinting, the increase in linear velocity most likely contributed to the higher level of performance achieved 15. It is likely that the improvement in the participant’s ability to turn 180° also played a role in increasing the distance covered on repeated trials at this test 15. Notably, a performance plateau was generally reached between the second and third trials, with mean stabilization occurring at 2.7 trials in the NAS group and 3.1 trials in the PAS group. This determination of the familiarization endpoint reflects the fact that individuals require different amounts of exposure to achieve stable performance. It also ensures that an individual’s true baseline is captured, rather than an arbitrary, fixed number of trials being determined.

Comparable outcomes were reported by Streetman et al 20., where 16 physically active college students demonstrated improved performance and reduced anxiety during high-intensity functional training following two familiarization sessions, with performance stabilizing after the third trial. Similarly, Hibbert et al21. found that in a 20 km cycling time trial, three familiarization trials were recommended for recreationally active individuals to reduce systematic error. Dias et al22. also reported performance stabilization in 1-RM strength assessments after two to three familiarization sessions in 21 resistance-trained men.

However, considerable individual variability was observed in this study, especially among physically active participants. Some of whom needed up to six trials to achieve stable performance. This suggests that while three familiarization trials may be sufficient for most individuals, additional trials may be necessary for others to obtain reliable baseline data. This emphasizes the individualized nature of the familiarization process and reinforces the recommendation to include familiarization sessions in testing protocols to minimize learning effects and better capture true training adaptations.

Despite consistent improvements in performance level, total distance, and estimated VO₂max, no significant differences were found between physically active and inactive participants. This suggests that baseline fitness does not substantially affect the final stabilized outcomes when considering initial performance. This finding aligns with García-Pérez et al23., who reported no consistent differences in familiarization duration or VO₂max between novice and experienced treadmill runners during 15 min of running. However, they emphasized that familiarization with longer, graded protocols may be more critical for trained individuals to achieve true maximal oxygen uptake. These insights are important for practitioners and researchers using the YYIR1 in heterogeneous populations, as they indicate that familiarization requirements may be broadly consistent regardless of training status. Nonetheless, the moderate effect sizes observed for VO₂max suggest subtle trends in favor of physically active individuals, likely reflecting increased physiological adaptation during high-intensity intermittent exercise.

The heart rate values also indicate that the exercise was performed with maximum effort. Although significant differences were observed in both groups across all trials, participants consistently achieved > 91% of their predicted HRmax. This confirms that the observed learning effects reflect genuine improvements in performance and pacing rather than submaximal effort during initial trials. Heart rate during recovery measured 1 and 2 min after the test demonstrated high consistency across trials and groups, suggesting that neither environmental familiarity nor physical activity level significantly influences early-phase recovery kinetics. These findings contrast with those of Barak r et al24., who reported that training status significantly influenced the kinetics of heart rate recovery, especially during the first 1–2 min after submaximal cycling in both trained and untrained male participants. We also observed a slight, nonsignificant improvement in 3-min heart rate recovery in physically active participants which may reflect differences in the late phase of autonomic regulation. This trend could be attributed to increased stroke volume, cardiac output, or vagal reactivation in individuals with higher training status, which may lead to a better recovery capacity for this type of exercise. It is known that the intensity of intermittent activity can influence the dynamics of autonomic recovery25.

Further, no significant changes in maximal heart rate between the first and last trials in PAS and NAS suggests a lack of improvement or potential decline in autonomic function, particularly in parasympathetic nerve activity. However, physically active subjects had a slightly faster heart rate recovery, indicating better cardiovascular conditioning and a more robust ability for the parasympathetic nervous system to slow the heart down after exercise. While HR in NAS decreased from 191.0 ± 5.5 bpm to 129.2 ± 10.7 bpm (32.4%) in the 3rd minute of recovery in the 1 st trial and from 190.9 ± 7.1 bpm to 130.8 ± 9.0 bpm (31.5%) in the 3rd minute of recovery in the last trial, in PAS it was a decrease from 182.5 ± 11.5 bpm to 117.5 ± 21.9 bpm (35.6%) in the 3rd minute of recovery in the first trial and from 185.9 ± 7.6 bpm to 116.3 ± 15.3 bpm (37.4%) in the 3rd minute of recovery in the last trial. From this it is evident that the decrease in heart rate was slightly faster in PAS compared to NAS (32.4% versus 35.6% in the first trial and 31.5% versus 37.4% in the last trial), indicating better cardiorespiratory fitness in PAS than in NAS. This is related to faster reactivation of the parasympathetic nervous system, which slows the heart rate.

Improvements in VO₂max across repeated trials underscore the positive influence of familiarization on performance, particularly among physically active participants who exhibited greater gains. However, these findings contrast with those of Lim et al26.. In their study, 15 physically active adults completed one laboratory−graded exercise test followed by three self-paced VO₂max field tests. Familiarization had minimal effect on VO₂max values but improved pace consistency and performance measures such as speed and distance. This discrepancy may stem from methodological differences. While Lim et al26. used direct VO₂max measurement using a portable metabolic gas analyzer, we have used an indirect estimate based on the highest level achieved during the test. Given this, it is likely that individuals with higher baseline fitness are better equipped to adapt to the intermittent demands of the YYIR1 test. This may be due to better pacing strategies, metabolic efficiency, or psychological factors like motivation and familiarity with the testing environment. This highlights the importance of familiarization trials to ensure valid and reliable fitness assessments, especially when VO₂max is estimated indirectly. Therefore, caution is warranted when interpreting estimated VO₂max data, especially in heterogeneous populations.

Improvements in distance covered during the YYIR1, strongly predicted by baseline scores, further support the test’s reliability and sensitivity to learning effects. CVs for performance level were 6.81–7.75% in NAS and 7.05–7.71% in PAS, and for maximal heart rate it was 2.9–3.69% in NAS and 4.09–6.32% in PAS. These values are consistent with those reported by Bangsbo et al2., who documented similar CVs for the YYIR1 in repeated testing scenarios.Higher CVs were observed for distance covered, 43.57–48.85% in NAS and 49.87–53.94% in PAS. This reflects the greater absolute variability associated with this measure, particularly during the initial familiarization phases, but improved substantially as participants reached their performance plateau on the test.

The lack of significant group differences in distance covered suggests that the familiarization effect operates similarly across fitness levels, with both physically active and inactive individualsfrom repeated exposure (21.4% and 16.7%, respectively). These findings are consistent with our previous findings15, where a physically active participant improved his YYIR1 performance by up to 17.9% comparedto his initial trial. This highlights the importance of incorporating familiarization trials to reduce the novelty effect and increase the validity of performance-based assessments within intermittent fitness testing.

Furthermore, there were no significant differences between groups in reaching a performance plateau, suggesting that the learning effect is overall consistent regardless of training background. The small effect size suggests any true differences may be subtle and undetectable within the current sample. This finding supports the practical recommendation that three familiarization trials are sufficient to stabilize performance across diverse populations.

Although these findings provide valuable insights into the understanding of learning effects in the YYIR1, a few limitations must be acknowledged. The relatively small and homogeneous sample of young university students limits the generalizability of the results. In addition, the small sample size reduces the statistical power to detect subtle between-group differences and interactions. The non-significant difference in the number of trials required to achieve stable performance between groups (Mann-Whitney U = 44.5, p =.649) may reflect insufficient statistical power rather than a true absence of effect, given the small sample size (n = 10 per group). Although the study was adequately powered to detect the large effect sizes observed for primary outcomes (VO₂max, distance covered), it may have had insufficient power to detect smaller differences in familiarization demands between physically active and inactive individuals.

Furthermore, no adjustments for multiple comparisons were applied to the seven ANOVA analyses because this exploratory study prioritized sensitivity to detect learning effects in physiological variables. However, this approach increases the risk of Type I error, and future studies should consider appropriate adjustments. Future research should also include larger and more diverse cohorts (females, youth athletes, etc.) to confirm and extend these findings. Longitudinal studies examining the effect of training interventions and long-term familiarization with the YYIR1 test and physiological responses would deepen understanding of the test’s reliability and validity in various contexts.

Conclusion

In repeated trials of the Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test (Level 1) with an interval of one week, a significant learning effect is evident within 3 trials, regardless of the subjects’ level of physical fitness. Specifically, there is a significant improvement in the performance level, distance covered, as well as maximal oxygen uptake, but not in maximal heart rate in the initial minutes after the test. However, this may bias the results, and therefore, practice trials are recommended before testing an individual’s ability to repeatedly perform high-intensity exercise using the YYIR1. Given the small sample size of this study, these conclusions should be interpreted with caution, particularly regarding non-significant findings, which may reflect limited statistical power to detect smaller effects rather than true absence of differences. Replication with larger samples is recommended to confirm these results.

Practical recommendations

The findings of this study have important implications for coaches, sport scientists, and practitioners using the Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Level 1 (YYIR1) in athletes and the general population. The results indicate a significant learning effect during the first two to three test administrations, regardless of participants’ baseline physical fittness levels. Some individuals, particularly physically active subjects, may require more than three familiarization sessions to reach stable performance. Therefore, it is strongly recommended to include a minimum of three familiarization trials before relying on YYIR1 outcomes for training prescriptions. Practitioners should closely monitor individual improvements across trials and continue familiarization until a performance plateau is achieved to ensure reliable baseline measurements. This is especially important in small groups or heterogeneous populations, where variability may be higher. Additional sessions should be provided for individuals whose performance appears inconsistent or unexpectedly low.

In addition, incorporating 3-minute heart rate (HR) recovery measurements post-test for each participant is advised, as this metric provides enhanced sensitivity to effort level, training status, and late-phase autonomic regulation, especially in physically active individuals. The rate of HR decline within the first three minutes post-exercise is closely linked to cardiovascular fitness and serves as a predictor of endurance capacity,recovery ability. Using the perceived exertion scale alongside HR measurements can further validate test results and help distinguish learning effects from submaximal effort. Furthermore, a 5–7-day interval between tests is recommended to prevent cumulative fatigue. Longitudinal monitoring should be employed to differentiate genuine performance changes from familiarization effects.

Implementing these practices will improve the reliability and validity of YYIR1 results by minimizing the confounding influence of test novelty. The notable within-group increases in distance covered—despite the absence of additional training—highlight the test’s sensitivity to familiarization effects. Crucially, a similar number of familiarization trials is required by both physically active and non-active individuals, supporting the use of a standardized testing protocol across varying fitness levels, enhancing consistency and comparability in field-based performance assessments.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author MP, upon reasonable request. Due to ethical restrictions and privacy considerations involving participant data, the dataset is not publicly available.

References

Krustrup, P. et al. The Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test: physiological response, reliability, and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35 (4), 697–705. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000058441.94520.32 (2003).

Bangsbo, J., Iaia, F. M. & Krustrup, P. The Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test: A useful tool for evaluation of physical performance in intermittent sports. Sports Med. 38 (1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200838010-00004 (2008).

Castagna, C., Impellizzeri, F. M., Chamari, K., Carlomagno, D. & Rampinini, E. Aerobic fitness and Yo-Yo continuous and intermittent tests performances in soccer players: A correlation study. J. Strength. Conditioning Res. 20 (2), 320–325. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-18065.1 (2006).

Mooney, M., Worn, R., Spencer, M. & O’Brien, B. J. Anaerobic and aerobic metabolic capacities contributing to Yo-Yo intermittent recovery level 2 test performance in Australian rules footballers. Sports 12 (9), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports12090236 (2024).

Rampinini, E. et al. Physiological determinants of Yo-Yo intermittent recovery tests in male soccer players. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 108 (2), 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-009-1221-4 (2010).

Schmitz, B. et al. The Yo-Yo intermittent tests: A systematic review and structured compendium of test results. Front. Physiol. 9, 870. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00870 (2018).

Vernillo, G., Silvestri, A. & La Torre, A. The Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test in junior basketball players according to performance level and age group. J. Strength. Conditioning Res. 26 (9), 2490–2494. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823f2878 (2012).

Grgic, J. et al. Test–retest reliability of the Yo-Yo test: A systematic review. Sports Med. 49 (10), 1547–1557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279–019–01143–4 (2019).

Dieter, D. et al. Reliability and validity of the Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level 1 in young soccer players. Dieter Deprez. 32 (10), 59. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2013.876088 (2014).

Glaister, M., Howatson, G., Pattison, J. R. & McInnes, G. Familiarization and reliability of multiple sprint running performance indices. J. Strength. Conditioning Res. 24 (4), 1131–1137. https://doi.org/10.1519/R–20336.1(2010).

Deprez, D. et al. Reliability and validity of the Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level 1 in young soccer players. J. Sports Sci. 32 (10), 903–910. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2013.876088 (2014).

Ehlert, A. M., Cone, J. R., Wideman, L. & Goldfarb, A. H. Evaluation of a goalkeeper-specific adaptation to the Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level 1: reliability and variability. J. Strength. Conditioning Res. 33 (3), 819–824. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002869 (2019).

Buchheit, M. & Rabbani, A. The 30–15 intermittent fitness test versus the Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level 1: relationship and sensitivity to training. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 9 (3), 522–524. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2012-0335 (2014).

Dobbin, N., Hunwicks, R., Highton, J. & Twist, C. A reliable testing battery for assessing physical qualities of elite academy rugby league players. J. Strength. Conditioning Res. 32 (11), 3232–3238. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002280 (2018).

Zemková, E. & Pacholek, M. Performance in the Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test May improve with repeated trials: does practice matter? J. Funct. Morphology Kinesiol. 8 (2), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk8020075 (2023).

Herrmann, S. D., Heumann, K. J., Ananian, D., Ainsworth, B. E. & C. A., & Validity and reliability of the global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ). Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 17 (3), 221–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/1091367X.2013.805139 (2013).

Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15 (2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012 (2016).

Li, C. H., Nesca, J., Waisman, M., Cheng, M. W. & Tze, V. M. C. A robust effect size measure Aw for MANOVA with non-normal and non-homogenous data. Methodological Innovations https://doi.org/10.1177/20597991211055949 (2021).

Yagin, F. H., Pinar, A., de Fernandes, S. & M. S Statistical effect sizes in sports science. J. Exerc. Sci. Phys. Activity Reviews. 2 (1), 164–171. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12601138 (2024).

Streetman, A. E., Lewis, A. K., Rogers, E. L., Heinrich, K. M. & DeBlauw, J. A. Anticipatory anxiety, familiarization, and performance: finding the sweet spot to optimize high-quality data collection and minimize subject burden. Eur. J. Invest. Health Psychol. Educ. 12 (9), 1349–1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe12090094 (2022).

Hibbert, A. W., Billaut, F., Varley, M. C. & Polman, R. C. J. Familiarization protocol influences reproducibility of 20-km cycling time-trial performance in novice participants. Front. Physiol. 8, 488. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00488 (2017).

Dias, R. M. et al. Influence of familiarization process on muscular strength assessment in 1-RM tests. Revista Brasileira De Med. Do Esporte. 11, 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-86922005000100004 (2005).

García-Pérez, J. A., Pérez-Soriano, P., Llana-Belloch, S., Lucas-Cuevas, Á. G. & Sánchez-Zuriaga, D. Do experienced and novice runners achieve kinematic and kinetic changes with treadmill running familiarization? Hum. Mov. Sci. 63, 120–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2018.11.015 (2019).

Barak, O. F. et al. Heart rate recovery after submaximal exercise in four different recovery protocols in male athletes and non-athletes. J. Sports Sci. Med. 10 (2), 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e6f8b5 (2011).

Sasso, J. P. et al. Investigating the role of exercise pattern in acute cardiovagal recovery. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 57 (3), 579–589. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000003580 (2025).

Lim, W., Lambrick, D., Mauger, A. R., Woolley, B. & Faulkner, J. The effect of trial familiarisation on the validity and reproducibility of a field-based self-paced VO₂max test. Biology Sport. 33 (3), 269–275. https://doi.org/10.5604/20831862.1208478 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prince Sultan University for their support in the form of publication incentives and covering publication fees. This work was supported by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences (No. 1/0725/23).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors have made substantial, direct and intellectual contributions to the work, and approved it for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pacholek, M., Prieto-González, P. & Zemková, E. The learning effect in repeated Yo-Yo intermittent recovery tests in adults with different levels of physical fitness. Sci Rep 15, 44754 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28776-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28776-y