Abstract

The vector propulsion system with a universal coupling joint exhibits complex spatial positioning and dynamic interactions. Under challenging sea conditions, the installation foundation of autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) rolls with the hull motion, transmitting complex alternating loads to the steering mechanism through the support structure. This significantly impacts the vibrational response of the propulsion shafting. First, based on coordinate transformation methods, the stiffness matrix and the inclination and rolling angles of key parameters are analyzed. The absolute velocity of the propeller is derived using velocity synthesis principles and coordinate transformation matrices. Next, a unified dynamic model of the propulsion system under basic motion is established using the Lagrange equation, with centroid displacement as the generalized coordinate. Finally, the vibration characteristics of the propeller and its corresponding propulsion performance under AUV rolling motion are investigated through numerical simulation and experimental methods. The results demonstrate that rolling conditions not only transmit low-frequency vibrations but also excite high-frequency structural-roll coupled vibrations. Shorter rolling periods and larger inclination angles increase vibration amplitudes and cause significant thrust losses. This effect is a critical consideration for the process control of vector propulsion systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of vector propellers on AUVs (Autonomous Underwater Vehicles) is a promising technology, as the propulsion system can provide not only forward thrust but also controllable forces and torques in pitch, yaw, roll, and reverse directions—a concept known as thrust vectoring1. Structurally, this system consists of two main components: the steering mechanism and the propeller shafting2. Among propeller shafting designs, universal joint-based systems are widely adopted due to their simplicity and high efficiency3. In such configurations, dynamic interactions exist between the propeller and the shafting. When an AUV equipped with a vector propeller operates at sea, environmental disturbances such as wind, waves, and currents inevitably induce various swaying motions4. Although the frequencies of these motions (including roll) are significantly lower than the propeller’s rotational frequency, they can still affect the shafting’s dynamic behavior through the steering mechanism. This influence becomes more pronounced as the vector propeller’s thrust angles increase, potentially leading to operational instability or even failure. To enhance the reliability and safety of vector propellers in complex marine environments, a thorough analysis of their dynamic characteristics under rolling conditions is essential5,6.

The motion characteristics of a vector propeller under rolling conditions fall within the research domain of rotor systems subjected to base excitation. Early studies in this field primarily focused on the dynamic response of rotating machinery under seismic excitation, with applications in seismic design. However, these investigations often overlooked the interaction between base motion and rotor dynamics. To quantify the influence of base excitation on rotor systems, some scholars employed simplified mass-spring-damper models to represent the base. While this approach provided preliminary insights, its applicability to multi-degree-of-freedom rotor systems proved limited. Consequently, alternative methodologies emerged, treating the base motion as an imposed kinematic constraint to compute the dynamic response of the rotor system. For instance, Tan7 derived the equations of motion for a cantilever rotor under base excitation using Euler-Bernoulli beam theory in conjunction with idealized assumptions. Similarly, Duchemin8 conducted theoretical and experimental studies on the dynamic behavior of a flexible rotor system subjected to support motion excitation, establishing a mathematical framework for calculating kinetic and strain energy.

A critical limitation of these studies lies in their assumption of a perfectly rigid foundation. In practice, foundation stiffness exerts a non-negligible influence on the system’s vibrational response9. This effect is particularly pronounced in vector propellers, where the propeller shafting is mounted on a steering mechanism whose stiffness undergoes significant variation during directional adjustments. Thus, a coupled analysis incorporating the rotor, bearings, and foundation is essential for accurate dynamic characterization. Recent advances in this domain include the amplitude filtering characteristics of singular value decomposition10 which investigated the response characteristics of different rotor configurations under varying support and foundation conditions. Cavalca11 and Chen12 introduced a mixed coordinate methodology to assess the influence of supporting structures on rotor dynamics. Chen13 further developed a comprehensive dynamic model of a rotor-bearing-casing coupled system, validating its accuracy through full-scale aero-engine testing. Complementary approaches include Wang’s14 impedance matching method, integrated with modal analysis and transfer matrix techniques, and Li’s15 simplified two-particle rotor model, which elucidated the effect of stator wall thickness on system vibrations and demonstrated the efficacy of model reduction strategies.

In actual rotor systems subjected to foundation excitation, both the supporting foundation and the rotor exhibit complex coupled motions. To study such dynamics, Wang16 designed an aircraft engine power simulator and investigated its dynamic characteristics under varying centrifugal forces and gyroscopic torques. Hou17 established the kinetic equations for a biased rotor system during maneuver flight and analyzed the nonlinear vibration response under different support schemes using numerical and analytical methods. Similarly, in AUVs equipped with vector propulsion systems, the propeller undergoes complex spatial motion due to AUV sway. This results in a highly dynamic coupling relationship between the propulsion shafting and the steering mechanism. Furthermore, the trigonometric relationship between the active and driven shafts of the universal joint in the propulsion system causes fluctuations in the propulsion angle, generating additional stress and deformation. These effects can adversely impact propulsion performance. Therefore, While Mazzer18, Zhu19 and Wang20 have conducted studies on the stability, kinematics, dynamics, and torsional vibration of universal couplings, there remains a lack of an appropriate computational method that integrates AUV motion with propeller motion. This gap leads to insufficient accuracy, reliability, and engineering applicability in numerical simulations.

Therefore, this study designs and develops a vector propulsion device and constructs a “propeller-steering mechanism” research system. The vibration characteristics of the system under rolling conditions are analyzed to enhance the engineering adaptability in the reliability design of vector propellers. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. Kinematic analysis of the vector propulsion system presents the coordinate system and kinetic model. Section Construction of fundamental dynamic equations for thruster constructs fundamental dynamic equations for thruster and derives the stiffness matrix. Section Construction of dynamic equations for thruster with AUV rocking constructs dynamic equations for thruster with AUV rocking. Section Calculation of vibration characteristics analyzes the vibration characteristics under different rolling conditions. Section Experiments of vibration characteristics and propulsion performance conducts experimental validation in conjunction with engineering applications.

Kinematic analysis of the vector propulsion system

Establishment of the coordinate system

Figure 1 depicts the vector thruster in its real-world configuration. The propeller shaft is connected to the screw via a universal joint to transmit power and torque. The moving platform, on which the propeller is mounted, may be oriented within a biconical workspace whose opening depends on the length of links and controlled through actuator adjustments. To ensure high maneuverability, every point within the biconical workspace must be reachable. Thus, a double-cross universal joint is adopted21 as it accommodates both translational and rotational misalignments during thrust vectoring. While this configuration provides greater flexibility, it also increases the system’s sensitivity to overall motion.

Based on the mechanical model mechanism illustrated in Fig. 1, a simplified model of the steering mechanism and propulsive shafting is established, as shown in Fig. 2(a). To characterize the spatial motion of each vector propeller component, kinematic coordinate systems must first be defined. Subsequently, the kinematic relationships between components are derived through coordinate transformation. The following four coordinate systems are implemented:

(1) Base coordinate system fixed on ground \({O_0} - {x_0}{y_0}{z_0}\), denoted by \({R^0}\).

(2) Inertial coordinate system fixed on AUV \({O_b} - {x_b}{y_b}{z_b}\), denoted by \({R^b}\).

(3) Rotation coordinate system on the geometry center of propeller as the original point, \({O_r} - {x_r}{y_r}{z_r}\) denoted by \({R^r}\).

(4) Rotation coordinate system on the mass center of propeller as the original point. \({O_c} - {x_c}{y_c}{z_c}\), denoted by \({R^c}\).

Based on the coordinate transformation relationship, the base coordinate system can be obtained by sequentially rotating the angles\(\alpha\), \(\beta\)and\(\gamma\)around the coordinate axes from an initial attitude parallel to the inertial coordinate system, as shown in Fig. 2(b). The corresponding coordinate transformation matrices for these three rotations are given in Eq. (1). Similarly, the spindle coordinate system \({R^c}\)can be obtained by sequentially rotating the angles \(\theta\), \(\varphi\), and \(\psi\)around the coordinate axes starting from an attitude parallel to the base coordinate system. Thus, the transformation matrix from\({R^b}\)to \({R^c}\)is derived as Eq. (2).

During vector thruster operation, the propeller rotates about its central axis while simultaneously exhibiting spatial oscillations due to unbalanced excitation forces. The propeller’s motion can be decomposed into: (1) rotational movement about a coordinate axis, (2) translational movement of its center of mass, and 3) rotational movement about its center of mass.

The rotational component of the motion of propeller

Establishing a unified dynamic model requires determining the propeller’s rotational characteristics in the difference coordinate system. For convenience, we denote the propeller rotational movement about a coordinate axis by\(\omega\), where the superscript indicates the two relatively moving coordinate systems, while the subscript specifies both the rotation axis and its associated coordinate system.

The propeller’s absolute rotation arises from the superposition of the AUV’s rotation relative to the ground and the propeller’s own rotation relative to the AUV. By applying time-dependent Euler angles, the components of angular velocity\(\omega _{{}}^{{bo}}\) in the coordinate system\({R^b}\)can be expressed as\(\omega _{{x,b}}^{{b0}},{\text{ }}\omega _{{y,b}}^{{b0}},{\text{ }}\omega _{{z,b}}^{{b0}}\), and calculated as follows:

According to the given equation, if two or more of (\(\dot {\alpha },\dot {\beta },\dot {\gamma }\)) are negligible:

In the same way, the component of \(\omega _{{}}^{{bo}}\) in the \({R^c}\) system is

According to the superposition theorem of the angular velocity vector, the vector form of the absolute angular velocity\({\omega ^{co}}\)of the propeller in the coordinate system \({R^c}\) is obtained as follows:

The translation component of the motion of propeller

Furthermore, to characterize the translational motion of the propeller in the \({R^0}\) coordinate, make the translational displacement and rotational displacement of \({R^r}\) to \({R^0}\) is \({x_c}\), \({y_c}\),\({z_c}\), and \({\theta _x}\),\({\theta _y}\),\({\theta _z}\)respectively; the translational displacement and rotational displacement of \({R^c}\) to \({R^0}\) is \({x_c}\), \({y_c}\),\({z_c}\), and \({\theta _{x,c}}\),\({\theta _{y,c}}\),\({\theta _{z,c}}\) respectively. \({\omega ^{b0}}\)is the angular velocity vector of the foundation rotation relative to the ground.

Set the coordinates of the geometric center of the in the basic coordinate system \({R^0}\) as\((\Delta x,\Delta y,\Delta z)\)at static condition, representing its spatial displacement from the AUV’s motion center along each axis. Therefore, the absolute position vector p of the propeller centroid is expressed as follows:

Where in: \({p_1}\) is the position vector of the propeller centroid in the coordinate system\({R^b}\)and \({R^0}\), respectively. Furthermore, the absolute rotation of the propeller is obtained by the rotation of the foundation to the ground and the rotation of the propeller itself to the base. So the absolute translation velocity of the propeller centroid is expressed as follows:

Besides, according to the geometrical relation of the double axis coupling, the coordinate of propeller can be expressed as following:

where in: \({L_1}\) is the length of the driven shaft. r is the inclination angle of the driven shaft. Substituting Eq. (10) into Eq. (9), the translation component with the inclination angle as the independent variable can be obtained.

Construction of fundamental dynamic equations for thruster

The dynamic equation of propeller

Given the structural complexity of the vector propulsion system, this section will first analyze the motion model of the propeller and then establish the fundamental dynamic equations of the vector thruster using the stiffness coupling method. Based on rotor dynamics theory, the propeller’s dynamic equation is derived as follows:

where in: M is the mass matrix; u is the matrix of center coordinates; G is the matrix of the gyro; C is the damping matrix; K is the stiffness matrix; \({F_u}\)is the additional excitation caused by the unbalance mass of propeller. The specific expansion formula for each part are as follows.

\(M=diag(m,m,{J_A},{J_A}),u={\left\{ {x,y,\theta {}_{x},{\theta _y}} \right\}^T}\)

\(G=\left[ \begin{gathered} 0{\text{ 0 0 0}} \hfill \\ {\text{0 0 0 0}} \hfill \\ {\text{0 0 0 }}{{\text{J}}_B}\omega \hfill \\ 0{\text{ 0 }}{{\text{J}}_B}\omega {\text{ 0}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right],{F_u}=\left\{ \begin{gathered} me{\omega ^2}\cos (\omega t+\varphi ) \hfill \\ me{\omega ^2}\sin (\omega t+\varphi ) \hfill \\ ({J_B} - {J_A}){\omega ^2}\delta \sin (\omega t+\varphi ) \hfill \\ ({J_A} - {J_B}){\omega ^2}\delta \cos (\omega t+\varphi ) \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right\}\)

Where in: m is the mass of the propeller; \({J_A}=({J_{xx}}+{J_{yy}})/2\), \({J_B}={J_{zz}}\), and \({J_{xx}}\),\({J_{yy}}\),\({J_{zz}}\) are the moment of inertia of propeller respectively; K is the equivalent stiffness matrix of propulsion system that can be calculated by the superposition of the support stiffness and the driven shaft itself stiffness in series generally22.

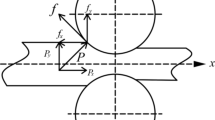

The stiffness matrix of steering mechanism

The steering mechanism of the vector thruster in this study is a multi-branch parallel structure with multi-degree-of-freedom, allowing the propeller to achieve deflection in both horizontal and vertical directions. Let \({\theta _x}\) be the horizontal deflection angle and \({\theta _y}\)be the vertical deflection angle. Using spatial geometry, the thrust vector is decomposed into the three axes of the motion coordinate system, yielding thrust components \({F_x}\), \({F_y}\), and \({F_z}\), as illustrated in Fig. 3. During the operation process, the vector thruster alters the direction of the propeller by adjusting the length of the telescopic rod and changing the inclination angle of the coupling. To simplify the calculations, we only consider the steering mode in which one link (A) performs telescopic motion while the other remains constant, as shown in Fig. 4. In this configuration, the variation in the propeller’s inclination angle is constrained to the \({x_b}{o_b}{z_b}\) plane.

Due to its short length, the driven shaft is resistant to bending under external loading during operation, making stiffness considerations unnecessary. However, the links are susceptible to both elastic and bending deformations along their length. Therefore, the brace stiffness under mechanical forces must be taken into account. As shown in Fig. 4, the transverse and longitudinal displacement of the propeller in the \({y_b}{o_b}{z_b}\) plane, denoted as \((x,y)\), can be determined by the radial and axial displacements at reference points A, B and C on the moving platform, denoted as \(({x_A},{y_A})\), \(({x_B},{y_B})\) and \(({x_C},{y_C})\), respectively.

As shown in Fig. 4, the moving platform (ABC) is an equilateral triangle, and O is the center of the triangle. Analysis of the moving platform’s geometric configuration reveals that: \({\raise0.7ex\hbox{$a$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {a l}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$l$}}={\raise0.7ex\hbox{$2$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {2 3}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$3$}}\), \({\raise0.7ex\hbox{$b$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {b l}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$l$}}={\raise0.7ex\hbox{$1$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 3}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$3$}}\). Based on these spatial relationships, the coordinate transformation can be formulated as:

Equations 14 and 15 can be expressed in matrix form as follows:

Assuming the propeller’s centroid is subject to both a concentrated force and torque, denoted as \(F=\left\{ {{F_x}{\text{ }}{F_y}{\text{ }}{M_y}{\text{ -}}{M_X}} \right\}\), the reaction forces at hinge points A, B, and C can be determined through force equilibrium and moment balance principles as follows:

Based on the force analysis of hinge points A, B, and C, it is assumed that the links experience solely axial deformation and bending deformation along the directions AO, BO and CO. Consequently, the force equations can be expressed in matrix form as:

where in: \({k_1}\) and \({k_2}\) are the tensile/compressive stiffness (axial load resistance) and bending stiffness (lateral load resistance) of the links respectively. Additionally, stiffness variations of the links during telescopic motion are disregarded.

The stiffness matrix of the vector thruster steering mechanism, which accounts for its geometric properties, is expressed by Eq. (17). This derivation, combined with the relationships established in Eqs. (13) through (16), leads to the formulation presented in Eq. (18). Since the derivation method for the damping matrix is similar to the stiffness matrix and their parameters are largely comparable, we omitted the detailed expression for brevity.

Construction of dynamic equations for thruster with AUV rocking

Due to the spatial offset between the propeller’s installation position and the AUV’s center of motion, the propeller’s three-dimensional motion under AUV rolling can be decomposed into translational components along the three principal inertial axes and rotational components about these axes8. Actual AUV motion encompasses multiple degrees of freedom (surge, sway, heave, pitch, and yaw), but the coupling effects between them are not significant for the vibration response under investigation23. Consequently, to streamline the computational analysis, this study focuses exclusively on roll motion, while other hull motion components are considered negligible (i.e., \(\gamma \ne 0\), \(\omega _{{z,b}}^{{bo}} \ne 0\), \(\dot {\omega }_{{z,b}}^{{bo}} \ne 0\)). Under these conditions, the roll motion dynamics can be described by the following governing equation:

The relative position of \({R^c}\) and \({R^r}\) is fixed, and the displacement of the two coordinate systems has the following relationship:

where in: e is the eccentricity, \(\varphi\) is the phase angle of the unbalanced mass.

Based on the kinematic transmission characteristics of universal joints, the motion relationship can be expressed as follows

where in: \(\theta ^{\prime}\),\(\theta\)are the angular displacement of the driving shaft and the driven shaft.

Neglecting the effects of backlash, friction, and misalignment in the joint, and assuming an ideal joint, the rotational speed of the propeller about its center of mass can be obtained by integrating both sides of Eq. 21 as follows:

where in, \(\Omega ^{\prime}\)can be regarded as the angular velocity of the driving shaft.

Due to the combined translational and rotational motions analyzed above, the propulsion system deviates from the inertial reference frame and is subjected to additional inertial forces. These inertial forces are independent of the propeller’s own velocity and displacement, but depend on the base motion characteristics (including translational and rotational velocities and accelerations), the propeller’s structural properties such as unbalanced mass magnitude and distribution, and the propeller’s rotational speed. Consequently, the dynamic equation (Eq. 11) must be modified as follows:

where in: the mass matrix M, the gyroscope effect matrix G, the damping matrix C and the stiffness matrix K are all consistent with those parameter when the foundation is fixed. The stiffness matrix of system \({K_b}\) is related to the speed and displacement of the propeller, and can be expressed as follows:

where in: \({K_{{{(\omega _{{x,b}}^{{bo}})}^2}}}=\left[ \begin{gathered} 0{\text{ }}0{\text{ }}0{\text{ }}0 \hfill \\ 0{\text{ -}}m{\text{ }}0{\text{ }}0 \hfill \\ 0{\text{ }}0{\text{ }}0{\text{ }}0 \hfill \\ 0{\text{ }}0{\text{ }}0{\text{ }}{J_A}{\text{-}}{J_B} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right]\)

Moreover, \({F_g}\)is the gravity component; \({F_b}\) is the additional incentive caused by AUV rolling; \({F_{bu}}\)is the coupling excitation induced by combined AUV roll motion and rotor unbalance24. The specific expansion formulas for these additional excitation can be expressed as Eq. 26. Vector decomposition of \({F_b}\) reveals that the additional excitation is independent of Coordinate \(\Delta z\), being solely determined by Coordinates \(\Delta x\)and \(\Delta y\).

\(F{}_{g}= - mg\left\{ \begin{gathered} \sin \gamma \hfill \\ \cos \gamma \hfill \\ 0 \hfill \\ 0 \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right\},{F_{bu}}=\left\{ \begin{gathered} 0 \hfill \\ m{(\omega _{{x,b}}^{{b0}})^2}e\sin (\Omega t+\varphi ) \hfill \\ 0 \hfill \\ ({J_B} - {J_A}){(\omega _{{x,b}}^{{b0}})^2}\delta \cos (\Omega t+\varphi ) \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right.\)

Calculation of vibration characteristics

Based on the established dynamic model of the propulsion system, the kinetic properties of the propulsion shafting are analyzed in this chapter. In the vector thruster, the driven shaft and links are fabricated from structural steel, with a Young’s modulus of 2 × 1011Pa. The geometrical parameters of the propulsion system are provided in Table 1.

Set the coordinate \(\Delta {x_0}\)= 0, \(\Delta {y_0}\)=0.5 m, \(\Delta {z_0}\)= 0, the inclination angle r = 5 deg; set the rolling period of AUV T = 6 S and roll amplitudes 20 deg. A numerical simulation is performed, and the resulting displacement of the propeller in the y-direction is shown in Fig. 5. The spectral patterns for displacement, acceleration, and velocity versus frequency are found to be fundamentally similar.

Figure 5(a) shows the time history of the vibration response. It can be observed that the vibration under roll motion represents a superposition of high-frequency and low-frequency components25, corresponding to structural-roll coupling vibration and roll vibration transmission respectively. Due to the influence of rolling motion is significantly weaker than that of the propeller’s eccentric load, the amplitude of the high-frequency vibration is much larger than that of the low-frequency vibration. As shown in Fig. 5(b), the high-frequency vibration components primarily consist of the first- and second-order natural frequencies. The contributions from higher-order natural frequencies are negligible. The first-order frequency band is primarily determined by the inertia and stiffness characteristics of the drive shaft, intermediate shaft, and driven shaft, while the second-order band mainly results from motion characteristic changes caused by inclination. In Fig. 5(b), the peak frequencies at 5 Hz, 10 Hz, and 15 Hz correspond to the rotational frequency, while the peaks at 0.25 Hz and 0.5 Hz align with the rolling response. Furthermore, certain nonlinear vibration features, including distinct peaks and excitation bands (e.g., 270–340 Hz), arise from nonlinear restoring forces and damping effects.

Since the shafting operating frequency is considerably higher than the AUV’s rolling frequency, the interaction between these vibrations is often neglected under normal working conditions. However, due to the system’s nonlinear characteristics, the high- and low-frequency vibrations may mutually reinforce each other—an effect that will be analyzed separately in the following section.

Characteristic analysis of roll vibration transmission

Based on the findings from Fig. 5, the vibration response of the propeller includes frequency components linked to the rolling frequency, primarily at one and two times the rolling frequency. Under these low-frequency vibrations, the thrust angle of the vector thruster fluctuates, which can impact the hydrodynamic performance of the propeller. Therefore, these characteristic frequencies were selected to analyze the vibration behavior under different operating parameters of the propulsion system. With the rolling amplitude fixed at 20 deg, simulations were conducted for rolling periods of 2 s, 4 s, 6 s, 8 s, and 10s. The resulting dynamic responses of the propeller in the x- and y-directions under these varying rolling conditions are presented in Fig. 6a, b, respectively.

Figure 6c demonstrates that the amplitudes of both once and twice rolling frequency components in the x-direction exhibit a decreasing trend as the rolling period increases. Notably, these amplitudes approach zero when the rolling period exceeds 6 s. Concurrently, the y-direction components show a gradual amplitude increase with rolling period until reaching a stable plateau beyond 6 s as shown in Fig. 6d. This behavior stems from enhanced propeller acceleration and corresponding excitation loads, which are directly influenced by the instantaneous acceleration characteristics of the AUV’s rolling motion. The propulsion system’s x-direction response is predominantly characterized by the fundamental rolling frequency component. In contrast, the y-direction response displays more complex dynamics: while containing the fundamental frequency component, it also features a twice the sway frequency component whose amplitude diminishes with increasing longitudinal rolling period, alongside a nearly constant DC offset. This is because the propeller’s inclination angle variation is constrained to the \({x_b}{o_b}{z_b}\) plane, which amplifies the resulting excitation loads in the y-direction. As a result, a direct correlation exists between the vibration amplitudes at twice the sway frequency and the AUV’s instantaneous roll acceleration.

During the inclination angle adjustment of the vector propeller, the propeller’s position relative to the AUV’s rolling center changes according to the computational model, thereby affecting the additional eccentric excitation. As analyzed in Sect. Construction of fundamental dynamic equations for thruster, the inclination angle variation introduces an additional bending moment, further exciting the shafting system. To comprehensively evaluate the effects of inclination angle variations on the shafting’s dynamic characteristics in the x- and y-directions, the vibration amplitude of the propeller was calculated at 5° increments. The results are shown in Fig. 7a,b, and the key observations include.

x-direction: The low-frequency vibration response is dominated by the rolling frequency (1×). The amplitude reaches its minimum at an inclination angle of r = − 5° and exhibits asymmetry about r = 0°, owing to the fact that this angle does not correspond to the position of minimal base excitation.

y-direction: The primary low-frequency response occurs at twice the rolling frequency (2×). The amplitude initially decreases, then increases with the inclination angle, reaching a minimum at r = 10°, also demonstrating asymmetry about r = 0°.

Characteristic analysis of structural-roll coupling vibration

Although the vibration amplitude at N-times the rolling frequency is relatively small, a distinct geometric mapping relationship exists between propeller vibration and inclination angle fluctuations due to the structural characteristics of the vector thruster. During AUV rolling, these fluctuations impact the steering mechanism’s stiffness, consequently altering the high-frequency vibration characteristics of the propulsion shafting and ultimately affecting propulsion performance. To better investigate how AUV rolling affects the vector propeller’s transient vibration, this chapter employs the amplitude of its inclination angle fluctuation to characterize the high-frequency components. Experimental tests were performed under two inclination conditions (r = 1° and r = 5°) with a fixed rolling period of 2 s and rolling amplitude of 20°. Figure 8 presents a comparison of the inclination angle fluctuation curves with and without AUV rolling under these two conditions.

From the time-domain response plot, it can be observed that although the propeller’s overall vibration behavior remains unchanged26, certain discrepancies exist in the values between the two conditions. As shown in Fig. 8a, the trend intensifies, with the fifth and sixth peaks becoming clearly visible due to sustained excitation. Compared to the condition of r = 1°, under r = 5°, the shift in natural frequency makes the rolling effect more pronounced in the waveform. As shown in Fig. 8b, a significant deviation is already observable in the 3rd and 4th waveforms. This shows that AUV rolling has different effects on various frequency components, requiring individual analysis.

As analyzed in Sect. Establishment of the coordinate system, the transient process contains multiple frequency components due to dynamic changes in the inclination angle of the propulsive shafting under rolling motion. We focus on the first-order band (150–300 Hz) and the second-order band (550–700 Hz), with rolling periods set to 2 S, 4 S, and 6 S. The maximum amplitude and corresponding peak frequency under different inclination angles are shown in Fig. 9. As illustrated in Fig. 9a, the results indicate that as the inclination angle increases, the vibration amplitude rises significantly in both the first- and second-order frequency bands. Additionally, a smaller swing cycle leads to a larger fluctuation amplitude—a trend more pronounced in the high-frequency band than in the low-frequency band. Meanwhile, Fig. 9b demonstrates that as the inclination angle increases, the peak frequency in the second-order frequency band shows a decreasing trend, while that in the first-order frequency band exhibits an increasing tendency. This trend becomes more noticeable at larger roll periods. This phenomenon occurs because the increasing angle progressively affects the moment of inertia, thereby reducing the natural frequency of the propulsion shafting. Consequently, this amplifies the influence of swing motion on the vibration response. These features may induce complex spatial vibrations in the propeller, influencing its hydrodynamic behavior—a phenomenon we will explore further below.

Experiments of vibration characteristics and propulsion performance

Based on the aforementioned vibration characteristics during AUV rolling motion, the AUV is subjected to multiple periodic and aperiodic disturbances from the offshore environment. These disturbances inevitably affect the thruster’s overall performance. To holistically examine this phenomenon, we designed the vector thruster system illustrated in Fig. 10. The vector thruster, with a rated thrust of 30 kg, is designed based on commonly available commercial structures. It is mounted externally to the hull, eliminating the need for hull-penetrating sealing devices. Both the linear and rotary motors are fully waterproof. In this configuration, the main thrust motor provides torque for propeller rotation, with thrust magnitude regulated by motor speed adjustment. Three servo motors drive three kinematic pairs, allowing the dynamic propeller to achieve attitude adjustments through variations in the telescopic rod length27.

This study investigates the influence of AUV motion on the vibration performance of a vector thruster using a simulated offshore test bench. As shown in Fig. 11, the propeller submergence depth is set at 0.5 L (where L is the total length of the thruster), and the water tank length is 6.25 L. The physical model is positioned to ensure computational accuracy with the following boundaries: the flow inlet is located 1.5 L from the front of the thruster, the outlet boundary is 3.375 L from the rear, and the side boundaries are symmetric with a diameter of 3 L. This configuration effectively minimizes boundary layer and wall proximity effects. Depending on operational requirements, the test bench can perform both fixed-point positioning and sinusoidal cyclic motions about its horizontal and vertical axes, enabling comprehensive testing of propulsion performance across various inclination angles and roll periods. The apparatus is equipped with a triaxial force transducer capable of measuring forces in all three directions (x, y, z). Accordingly, the system provides real-time monitoring of these parameters. However, as this study focuses on propulsion efficiency, only the unidirectional thrust component is analyzed.

To systematically evaluate propulsion performance of vector thruster across different operational poses, tests are conducted at inclination angles of 5° and 10°, rolling periods of 2 s and 4 s, and a constant propeller speed of 400 rpm. The specific steps are as follows:

Step 1: Configure the monitoring system to track and record the key parameters such as the vertical displacement of the driven shaft, the effective thrust and force efficiency.

Step 2: The experimental system was activated and allowed to stabilize prior to data collection. Parameter monitoring included real-time numerical displays, dynamic visualization of performance curves (with adjustable viewing ranges), and automated data archiving.

Step 3: Upon completing data acquisition for the current inclination angle and roll period, manually adjust the thruster to the next working condition.

Step 4: Access the auto-saved system data, organize the results, and plot dynamic curves in MATLAB using effective thrust and torque as dual vertical axes, as shown in Fig. 12.

In Fig. 12, the right coordinate axis represents the vertical displacement of the driven shaft. A comparison between Fig. 12a,c shows that as the roll period decreases, its fluctuation amplitude increases significantly. Additionally, compared with Fig. 12b,d exhibits not only a larger fluctuation range but also a higher fluctuation frequency. These observations align with the conclusions drawn in Sect. Calculation of vibration characteristics. Furthermore, the vertical displacement in Fig. 12b demonstrates a greater fluctuation range and higher fluctuation rate than in Fig. 12a. A similar trend is observed between Fig. 12c,d. This phenomenon can be attributed to increased propeller vibration caused by variations in the inclination angle.

Figure 12 also shows the variation of effective thrust on the left vertical axis. It can be observed that the effective thrust is strongly correlated with the vertical displacement of the driven shaft. When the vertical displacement fluctuates, the effective thrust follows essentially the same pattern of fluctuation while exhibiting an overall reduction. This occurs because the inclination angle fluctuation intensifies the wake vortex effect, thereby influencing the hydrodynamic performance of the propeller. To further investigate the influence of AUV rolling on propeller dynamic performance, multiple sets of data are measured and analyzed, and the theoretical thrust is calculated as a second-order nonlinear function of the propeller’s rotational speed. The variation of thrust with the inclination angle was plotted for rolling periods of 2, 4, and 6 s, with the theoretical values indicated by a dashed line, as shown in Fig. 13.

It can be observed that when the roll period is small, the effective thrust exhibits significant thrust loss, and the larger the inclination angle, the greater the thrust loss. This is because the AUV’s rolling intensifies the fluctuation of the inclination angle, thereby affecting the internal flow field characteristics of the thruster and resulting in thrust loss. As the roll period increases, the thrust loss gradually decreases, and the thrust progressively rises, with the thrust variation patterns under different inclination angles being essentially consistent. When the roll period exceeds 6 s, the effective thrust essentially approaches the thrust characteristics of the thruster under non-rolling conditions (as indicated by the dashed line). Therefore, it is essential to fully account for the roll motion’s impact on AUV thrust at large inclination angles. Accordingly, designers should adjust shaft stiffness or steering mechanism geometry to minimize such vibrations and implement real-time thrust vector compensation. Due to the simultaneous variations in rotational speed, thrust and thrust angle during the operation of the vector thruster, further experimental studies are essential to ensure the motion accuracy and dynamic stability of the propulsion system under complex working conditions.

Conclusion

The rolling motion of an AUV equipped with a vector thruster may generate additional inertial forces and moments on the propeller, leading to coupled vibration between the steering mechanism and the propulsive shafting. These inertial forces can alter the inclination angle of the shafting, further amplifying vibrations and creating a feedback mechanism. To investigate the dynamic characteristics of the vector thruster under AUV rolling conditions, a unified spatial dynamic model was established and validated through an offshore test bench under simulated operational conditions. The results from numerical simulations and experimental studies are summarized as follows:

-

(1)

The complex trigonometric relationships among components of the vector thruster lead to additional parameter matrices in its equations of motion under rolling conditions. Building upon this foundation, the proposed unified mathematical model employing coordinate transformation effectively characterizes the integrated impact of AUV rolling motion on the vector thruster.

-

(2)

The vibration response of the propulsion shafting under AUV rolling contains both low-frequency and high-frequency components. The low-frequency components are related to the natural frequency of the rolling motion, primarily at 1× and 2× the rolling frequency, and originate from additional inertial forces and moments. High-frequency vibrations are attributed to structural-roll coupling from dynamic changes in the inclination angle, which can induce complex propeller gyrations that may degrade hydrodynamic performance.

-

(3)

The vibration characteristics and propulsion performance of the vector thruster are influenced by both the AUV’s rolling frequency and the driven shaft inclination angle. As the rolling period decreases and the inclination angle increases, the thrust exhibits larger fluctuation amplitudes and significant losses. Ensuring the AUV’s control accuracy requires mitigating roll-induced vibrations through optimization of both the stiffness characteristics and spatial positioning of the steering mechanism, along with the implementation of real-time thrust vector compensation.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tabatabaee-Nasab, F. S. & Moosavian, S. Self-tuning tracking control of AUVs for inspection task with ocean turbulences and uncertainties. Ocean Eng. 295, 116843 (2024).

Dong, L. X. & Li, J. B. Investigating the vibration characteristics of vector thrusters under complex inclination angle variations. Ships Offshore Struct. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445302.2024.2411390 (2024).

Emanuele, C., Vladimir, F. & Rinaldo, C. Path guidance and attitude control of a vectored thruster AUV. Proceedings of the 7th Biennial Conference on Engineering Systems Design and Analysis. 325–332 (2004).

Zhu, L. X. & Yu, L. F. Waves of 3D marine structures slamming at different initial poses in complex wind-wave-flow environments. China Ocean. Eng. 30, 772–785 (2016).

Singh, M. P., Chang, T. S. & Suarez, L. E. A response spectrum method for seismic design evaluation of rotating machines. J. Vib. Acoust. 114, 454–460 (1992).

Sun, B., Zeng, Y. Z. & Su, Z. N. Task allocation in multi-AUV dynamic game based on interval ranking under uncertain information. Ocean Eng. 288, 116057 (2023).

Tan, T. H., Lee, H. P. & Leng, G. Dynamic stability of a radially rotating beam subjected to base excitation. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 146, 265–279 (1997).

Duchemin, M., Berlioz, A. & Ferraris, G. Dynamic behavior and stability of a rotor under base excitation. J. Vib. Acoust. 128, 576–585 (2006).

Yu, D. M., Zou, L. & Wan, D. C. Numerical analysis of multi-modal vibrations of a vertical riser in step currents. Ocean Eng. 152, 428–442 (2018).

Guo, M. J., Li, W. G., Yang, Q. J., Zhao, X. Z. & Tang, Y. L. Amplitude filtering characteristics of singular value decomposition and its application to fault diagnosis of rotating machinery. Measurement 154, 107444 (2020).

Cavalca, K. L. & Okabe, E. P. On the analysis of rotor-bearing-foundation systems. Springer Netherlands (2011).

Chen, Y. S. et al. Accurate identification of the frequency response functions for the rotor-bearing-foundation system using the modified Pseudo mode shape method. J. Sound Vib. 329, 644–658 (2010).

Chen, G. A coupling dynamic model for whole aero-engine vibration and its verification. Journal Aerosp. Power. 27, 241–254 (2012).

Wang, Z. Calculation methods for the vibration of a huge Rotor-Bearing-Foundation system. Journal Tsinghua Univ. (Science Technology). 9–20 (1984).

Li, K. H., Tai, X. Y. & Sun, D. Vibration characteristics analysis of rotor-stator coupled systems. J. Shenyang Aerosp. Univ. 33, 17–21 (2016).

Wang, S., Liao, M. & Wei, L. Vibration characteristics of squeeze film damper during maneuver flight. Int. J. Turbo Jet-Engines 32, 85 (2015).

Lei, H., Yushu, C. & Qingjie, C. Nonlinear vibration phenomenon of an aircraft rub-impact rotor system due to hovering flight. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 19, 286–297 (2014).

Mazzei, A. J. Dynamic stability of a rotating shaft driven through a universal joint. J. Sound Vib. 222, 19–47 (1999).

Zhu, J. L., Ma, W. H. & Hu, B. C. Dynamic analysis of double universal couplings. J. Jilin Univ. (Engineering Technol. Edition). 26, 77–81 (1996).

Wang, H. E., Luo, Y. G. & He, M. Analysis and calculation of torsional vibration of multi joint universal drive shaft in three-dimensional space. J. Mech. Eng. 36, 37–41 (2000).

Joonyoung, K. & Kihun, K. C. Estimation of hydrodynamic coefficients for an AUV using nonlinear observers. IEEE J. Oceanic Eng. 27, 830–840 (2002).

Liu, P., Islam, M. & Veitch, B. Unsteady hydromechanics of a steering podded propeller unit. Ocean Eng. 36, 1003–1014 (2009).

Yu, D. M., Chen, J. P. & Chen, Y. Z. Prediction of the VIV Responses Based on the Numerical Solutions of Controlled Motion. Shock and Vibration. 2774070 (2021). (2021).

Zou, D., Rao, Z. & Na, T. Coupled longitudinal-transverse dynamics of a marine propulsion shafting under superharmonic resonances. J. Sound Vib. 346, 248–264 (2015).

Zou, D. L. et al. Influence evaluation of wake shedding on natural frequencies of marine propulsion shafts. J. VibroEng. 19, 2142–2152 (2017).

Dong, L. X. & Li, J. B. Coupled vibration characteristics of marine shafting with complex change of inclination under ice loads. Adv. Mech. Eng. 15, 1–15 (2023).

Kadiyam, J. et al. Simulation-based semi-empirical comparative study of fixed and vectored thruster configurations for an underwater vehicle. Ocean Eng. 234, 109231 (2021).

Funding

This paper was supported by Guangdong Key Construction Discipline Research Capacity Improvement Project (Grant No. 2024ZDJS058).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: L. Dong, J. Li; data collection: L. Dong, J. Liu; software: J. Li; analysis and interpretation of results: L. Dong, J. Li, X. Zhao; draft manuscript preparation: L. Dong, J. Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Dong, L., Liu, J. et al. Investigating the vibration characteristics of vector thrusters under rolling condition. Sci Rep 15, 43564 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28791-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28791-z