Abstract

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is characterized by glomerular deposits of IgA-containing immune complexes (IgA-ICs), which are suspected to originate from circulation. However, the composition of these ICs is not fully understood. To address this gap in knowledge, we performed label-free quantitative mass-spectrometry analyses of glomerular and circulatory IgA-ICs with a focus on complement proteins. Glomeruli of patients with IgAN compared to healthy glomeruli had greater amounts of several complement-system proteins associated with classical, alternative, and terminal pathways, including complement factor H-related (CFHR) proteins 1, 2, 3, and 5, C1q chains B and C, and properdin. Circulatory IgA-ICs of patients with IgAN vs. healthy controls had a greater abundance of complement proteins CFHR1, C1q chains A, B, and C, and properdin. Furthermore, levels of several complement proteins in circulatory IgA-ICs of IgAN patients were reduced after immunosuppressive therapy (i.e., tonsillectomy combined with pulse steroid therapy) but not in patients on comprehensive supportive therapy. CFHR1 exhibited the greatest decrease (Fold change = 48.16, P < 0.0001). These data together revealed the complexity of complement proteome in glomerular and circulatory IgA-ICs and suggested an association of complement regulatory proteins, such as CFHR1, with pathogenic IgA-ICs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) is a common primary glomerulonephritis, with many patients progressing to kidney failure1,2. The pathogenesis of IgAN follows a multi-hit mechanism, starting with aberrantly glycosylated IgA1, known as galactose-deficient IgA1 (Gd-IgA1), being the initiating element (Hit1)3. In this hypothesis, Gd-IgA1-containing immune complexes (ICs) with molecular weight greater than 800–900 kDa form in the circulation (Hits2–3), and some of these ICs enter glomerular mesangium and activate mesangial cells, resulting in the cellular proliferation and overproduction of extracellular matrix, cytokines, and chemokines (Hit4)4. However, the specific components of IgA-immune complexes (IgA-ICs) and the proteins involved in the development of glomerulonephritis through IgA-IC deposition in the glomeruli are not yet fully understood.

Kidney biopsy specimens from patients with IgAN show mesangial IgA deposits with a granular pattern, similar to that observed with other circulating ICs associated with glomerulonephritis, such as those in lupus nephritis. The recurrence of IgAN after kidney transplantation further supports the role of circulating IgA-IC deposition in the pathogenesis of IgAN5. IgA1 with galactose-deficient O-glycans forms IgA1-ICs with IgG6,7, and IgG recognizing Gd-IgA1, defined as a Tn antigen (i.e., IgA1 with a GalNAc residue(s)), is elevated in the circulation of many patients with IgAN8, resulting in the glomerular co-deposition of IgA and IgG9. These findings suggest that the production of autoantibodies against abnormally glycosylated IgA1 is involved in the pathogenesis of IgAN. Recently, Matsumoto et al. showed that the levels of circulating ICs with IgM specific for Tn antigen are elevated in the sera of patients with IgAN compared with healthy individuals and that it contained complement C310. However, glomerular deposition of IgM is variably present and not detected in all patients; 4 to 70% in pediatric patients and 25% in adult11,12.

Several components of the complement pathway have been detected in the glomeruli of patients with IgAN13. Immunohistochemical analyses have identified properdin, complement factor (CF) B, CFH, and CFH-related proteins (CFHR) 1 and 5 from the alternative pathway, as well as mannan-binding lectin (MBL), MBL-associated serine protease 1 and 2, and C4d from the lectin pathway13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Glomerular complement C3-IgA colocalization is associated with active glomerular injury20, and glomerular CFHR5 deposition correlates with C3 fragments and C5b-9 deposition and shows severe progression, whereas factor H deposition is reduced in progressive cases15. MBL glomerular deposition is observed in about 25% of patients and is linked to histological severity, while mesangial C4d deposition in the C1q-negative cases predicts poor prognosis18,19. Although C1q, the initiating component of the classical pathway, is rarely detected, some studies suggest an association between the glomerular deposition of C1q and IgAN progression21,22. These findings together support the role of complement in the glomerular injury. However, the key IgA-IC-associated molecules and pathways involved in the development of glomerulonephritis remain unclear.

To identify molecules involved in the pathogenesis of glomerulonephritis and nephritogenic molecules in the circulating IgA-ICs of patients with IgAN, we performed a comprehensive proteomic evaluation by mass spectrometry label-free quantification using laser capture micro-dissected (LMD) paraffin embedded kidney tissues and circulating IgA-ICs. Specifically, we assessed the proteome of IgA-ICs and glomerular proteins using two groups of patients with different treatments, those who received immunosuppressive therapy group (i.e., tonsillectomy combined with pulse steroid therapy) and those who were on supportive therapy (i.e., comprehensive supportive therapy including renin-angiotensin-system inhibitor; RASI). Our results revealed elevated abundance of several complement proteins, including the regulatory proteins CFHR1, 2, 3, and 5, in glomerular proteome of patients with IgAN. Some of these proteins, including CFHR1, were also elevated in the circulating IgA-ICs from patients with IgAN. Notably, CFHR1 abundance in these circulating complexes was reduced after immunosuppressive therapy but not after supportive therapy. These findings together underscore the importance of complement and complement regulatory proteins in the biological activity of IgA-ICs in IgAN.

Results

Glomerular proteomic analysis

Using a workflow combining laser capture microdissection with mass spectrometry (MS) for analysis of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) kidney tissues, we have performed proteomic analysis of glomeruli from patients with IgAN (n = 31) and controls (n = 10). The clinical characteristics and renal-biopsy pathology of patients with IgAN included in the glomerular proteome are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The information about control-kidney tissues purchased from OriGene Technologies (Rockville, MD, USA) was shown in Supplementary Table S2. We detected 2207 proteins of which 501 proteins had a greater abundance in the glomeruli of patients with IgAN compared to those from normal glomeruli of control tissues (Supplementary Table S3). Of those, 244 has ≥ 2-fold higher abundance, including some complement proteins and immunoglobulin component chains, such as the constant segments of IgA1 and IgA2 heavy chains, lambda light chain, and several variable segments of heavy and light chains. The complement protein with most elevated abundance in glomerular proteome in IgAN was CFHR1.

To visualize the relationship between the proteins abundant in the glomeruli from patients with IgAN, k-means clustering was performed using Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING). K-means clustering of the top 100 proteins with elevated abundance in patients with IgAN revealed biological functions related to complement activation, nucleic acid-binding proteins, proton motive force-driven mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis, and extracellular matrix organization as major clusters (Fig. 1). A total of 28 proteins associated with the complement cascade, as listed in Map04610 of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway, were identified. These proteins are plotted on a volcano plot comparing differentially abundant proteins between patients with IgAN and controls (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table S4). CFHR1 showed the highest fold change (FC) among the complement-related proteins, with CFHR2, CFHR3, and CFHR5 also detected at elevated levels in the IgAN glomeruli (CFHR1, FC = 12.92, P < 0.0001; CFHR2, FC = 6.91, P < 0.0001; CFHR3, FC = 1.84, P = 0.0456; and CFHR5, FC = 5.48, P < 0.0001). The levels of complement proteins involved in the classical, alternative, and terminal pathways were also higher in patients with IgAN than in controls (Fig. 2c).

Diagram of protein-protein interaction analysis of the top 100 glomerular proteins upregulated in patients with IgAN compared with controls. K-means clustering in the STRING database, using an average confidence score of 0.4 and 7 clusters, identified major biological functions, including complement activation (red), nucleic acid binding protein (dark goldenrod), proton motive force-driven mitochondrial ATP synthesis (green), and extracellular matrix organization (light green). Lines in different colors indicate various types of interactions, including known, predicted, and other interactions. Red line, gene fusions; green line, gene neighborhood; blue line, gene co-occurrence; purple line, experimentally determined; yellow line, text mining; cyan line, from curated databases; black line, co-expression; light blue line, protein homology. STRING, Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins; IgAN, IgA nephropathy; ATP, adenosine triphosphate.

Volcano plot comparing glomerular protein abundance between patients with IgAN and controls (a). Volcano plot comparison of glomerular-protein abundance between the immunosuppression therapy and supportive therapy groups of patients with IgAN (b). A P value of less than 0.05 and an absolute value of Log2 (fold change) of greater than 0.58 were considered significant. Molecules significantly upregulated are shown on the right side in red, while those downregulated are shown on the left side in blue. Molecules that were not significantly different between the two groups appear in gray. Gene symbols related to the complement cascade are annotated. The diagram of complement pathway (c). The proteins which were detected more abundantly in the glomeruli of patients with IgAN compared to controls were colored according to fold-change levels. IgAN, IgA nephropathy; FC, fold change; CFHR, Complement factor H-related protein; CFH, Complement factor H; C1QB, Complement C1q subcomponent subunit B; C1QC, Complement C1q subcomponent subunit C; C1R, Complement C1r subcomponent; C3, Complement C3; C4A, Complement C4-A; C4B, Complement C4-B; C4BPA, C4b-binding protein alpha chain; C5, Complement C5; C6, Complement component C6, C7, Complement component C7; C8A, Complement component C8 alpha chain; C8B, Complement component C8 beta chain; C8G, Complement component C8 gamma chain; C9, Complement component C9; F2, Prothrombin; SERPING1, Plasma protease C1 inhibitor; CFP, Properdin; CFB, Complement factor B; CFD, Complement factor D; DAF, decay-accelerating factor; CR1, Complement receptor type 1; CFI, Complement factor I; CLU, Clusterin; VTN, Vitronectin; MAC, Membrane attack complex; MBL, Mannan-binding lectin; MASP, Mannose-binding lectin-associated serine protease.

To determine whether glomerular proteome may show differences based on the clinal status and treatment modality, we analyzed samples from patients with IgAN on immunosuppressive therapy group (n = 18) vs. those on supportive therapy (n = 13). The clinical characteristics are detailed in Supplementary Table S1. A total of 2226 proteins were identified of which 55 proteins had higher abundance in the immunosuppressive-therapy group vs. supportive therapy group (Supplementary Table S5). This result was visualized in a volcano plot, with annotations highlighting the molecules involved in the complement pathway (Fig. 2b). The abundance of complement proteins was generally comparable between the two groups, except for CFHR3 that was higher in immunosuppressive therapy group (FC = 3.62, P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Table S5).

Comparison of IgA-IC components between patients with IgAN and healthy controls (HCs)

Next, we have analyzed serum IgA proteomes with a goal to identify proteins associated with IgA-IC and cross-compare the results with the data from glomerular proteomics. We used serum samples from 14 patients who were diagnosed in 2021 with IgAN and then underwent tonsillectomy plus corticosteroid therapy and serum samples from 20 healthy volunteers, which represent a cohort partially distinct from that used in the glomerular proteomics analysis; nine of the patients included in this analysis were also included in the analysis of the immunosuppressive therapy group in the glomerular proteomics study. The demographic and clinical laboratory data are provided in Supplementary Table S6. MS analysis identified 234 proteins (Supplementary Table S7) of which 18 proteins were more abundant in IgA-ICs from patients with IgAN compared to those from HCs (Table 1). The proteins abundant in IgA-ICs from patients with IgAN were clustered mainly into those associated with host-killing symbiont cells and those associated with the initial triggering of the complement pathway using k-means clustering algorithm (Fig. 3). CFHR1 was the most abundant complement-associated protein, and the three component chains of C1q (A, B, and C chains) and properdin were detected at higher levels in patients with IgAN compared to HCs (Table 1). It was determined that CFHR1 was one of the common proteins detected more abundant in the glomeruli and IgA-ICs of patients with IgAN compared to HCs. These findings, particularly those regarding CFHR1, did not change when only patients available for both glomerular and IgA-IC proteomics were included (data not shown). We confirmed the colocalization of CFHR1 with mesangial IgA deposition by immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. 4).

Diagram of the protein-protein interaction analysis of proteins that are more abundant in IgA-ICs in the IgAN group compared with healthy controls. K-means clustering (3 clusters) on STRING database, with an average confidence score 0.4, revealed two major protein groups: one associated with host killing of symbiont cells and the other associated with initial triggering of the complement pathway. C1QA, Complement C1q subcomponent subunit A; C1QB, Complement C1q subcomponent subunit B; C1QC, Complement C1q subcomponent subunit C; CFP, Properdin; CFHR1, Complement factor H-related protein 1; CSTG, Cathepsin G; DEFA1, Neutrophil defensin 1; LTF, Lactotransferrin; HP, Haptoglobin; ACTB, Actin, cytoplasmic 1; AMBP, alpha-1-microglobulin/bikunin precursor; PRSS3, Trypsin-3.

Representative images of immunofluorescence staining of remnant frozen kidney-biopsy specimens for CFHR1 and IgA. Double immunofluorescence staining of CFHR1 (red) and IgA (green) using frozen kidney-biopsy sections of the control and patients with IgAN. Representative glomerular images from one control and three patients with IgAN. CFHR1 is colocalized predominantly with IgA in the mesangium. The negative control for CFHR1 is shown in the right row, and the glomeruli are marked by a dotted line. (Size bars = 20 μm: original magnification ×40)

Longitudinal changes in the components of IgA-ICs across different treatment groups

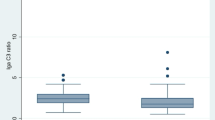

To assess the impact of therapy on IgA and IgA-IC proteome, we analyzed the IgA-ICs proteomes at diagnosis and after treatment using samples from volunteers whose pre- and post-treatment sera were available in immunosuppressive therapy (n = 10) and supportive therapy groups (n = 8), which partially differ from the cohort used for glomerular proteomics analysis; eight patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy and five patients receiving supportive therapy were also included in the glomerular proteomics study. The demographic and clinical laboratory data are provided in Supplementary Table S6. MS analysis identified 233 proteins in IgA-ICs from patients treated with immunosuppressive therapy (Supplementary Table S8). The proteins that significantly decreased after immunosuppressive therapy are listed in Table 2. CFHR1, which was found in high abundance in IgA-ICs in patients with IgAN at diagnosis, showed the most significant reduction after treatment in the immunosuppressive therapy group (FC = 48.16, P < 0.0001), whereas it remained unchanged in the supportive therapy group (FC = 1.69, P = 0.4547) (Supplementary Table S9). The comparison of the abundance of proteins detected in IgA-ICs at diagnosis in the immunosuppressive therapy and supportive therapy groups revealed that CFHR1 was more abundant in the immunosuppressive therapy group (FC = 5.14, P = 0.0199) (Supplementary Table S10). The attributable value of CFHR1 in IgA-ICs at diagnosis, calculated by normalizing the Log2-transformed abundance value measured by MS and imputing the missing values based on a normal distribution followed by normalization subtracting the median of each sample, was compared between the two treatment groups, and their changes before and after treatment were visualized (Fig. 5). The CFHR1 levels in IgA-ICs at diagnosis were significantly higher in the immunosuppressive therapy group compared with the supportive therapy group (Mann–Whitney test, P = 0.0343) and the abundance of CFHR1 decreased after treatment in the immunosuppressive therapy group but remained unchanged in the supportive therapy group (P = 0.0020 and P = 0.3200, respectively). To validate the proteomic results, CFHR1 levels contained in IgA-ICs (ng/10 µg IgA) were measured using a CFHR1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit. A significant correlation was observed between CFHR1 abundance measured by MS (n = 70; HC, n = 20; IgAN at diagnosis, n = 32; IgAN 2 years after diagnosis, n = 18) and by ELISA (P ≤ 0.0001, r = 0.8446). The CFHR1 levels in IgA-ICs quantified by ELISA (ng/10 µg IgA) were significantly higher in patients with IgAN compared with HCs and disease controls (P = 0.0009 and P = 0.0003, respectively) (Fig. 6). The demographic and clinical laboratory data are provided in Supplementary Table S11. Next, we assessed the effect of treatment on total serum levels of CFHR1. The results showed that total serum levels of CFHR1 were significantly higher in patients with IgAN compared with HCs and disease controls (P = 0.0042 and P < 0.0001, respectively) but the serum CFHR1 levels did not change between samples collected at diagnosis and post-treatment (Supplementary Figure S1).

Comparison of CFHR1 levels in IgA-ICs between immunosuppressive-therapy and supportive-therapy groups and their changes before and after treatment. The vertical axis represents the attributable CFHR1 value in IgA-ICs measured by MS (AU). This value was calculated by normalizing the Log2-transformed abundance measured and replacing the missing data with a normal distribution. Normalization was performed by subtracting the median of Log2-transformed abundance of each sample. The CFHR1 levels in IgA-ICs at diagnosis were significantly higher in the immunosuppressive-therapy group compared with the supportive-therapy group (Mann-Whitney test, P = 0.0343) (a). The abundance of CFHR1 decreased after treatment in the immunosuppressive-therapy group but remained unchanged in the supportive-therapy group (Wilcoxon test, P = 0.0020; Paired t test, P = 0.3200) (b, c). CFHR1, complement factor H-related protein 1; IgA-ICs, IgA-immune complexes; RBX, renal biopsy; MS, mass spectrometry; AU, arbitrary unit.

Determination of CFHR1 abundance in IgA-ICs by ELISA. CFHR1 levels in IgA-ICs (expressed in ng/10 µg IgA) were significantly higher in patients with IgAN compared with HCs and disease controls (Kruskal–Wallis test followed by post-hoc Dunn’s test, P = 0.0009 and P = 0.0003, respectively). CFHR1, complement factor H-related protein 1; HCs, healthy controls; DCs, disease controls; IgAN, IgA nephropathy; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Discussion

Results of this study showed that some complement proteins, including those associated with the classical, alternative, and terminal pathways, were more abundant in the glomeruli of patients with IgAN compared to those of controls. CFHRs, regulatory proteins that compete with CFH to regulate C3b inactivation, were also highly upregulated in the glomeruli of IgAN patients, with CFHR1 showing the highest FC among the complement proteins. Furthermore, circulating IgA-ICs in patients with IgAN contained elevated levels of complement proteins, including C1q, CFHR1, and properdin. The abundance of CFHR1 in IgA-ICs at diagnosis was higher in immunosuppressive therapy group than in supportive therapy group and was also higher than in healthy controls and disease controls. Notably, the abundance of CFHR1 in IgA-ICs decreased after immunosuppressive therapy and correlated with therapeutic remission. In contrast, total serum CFHR1 levels were significantly elevated in the IgAN patients compared to both healthy and disease controls but remained unchanged after either immunosuppressive or the supportive therapy. Although speculative, elevated circulating total CFHR1 levels in patients with IgAN may modulate alternative complement pathway upon exposure to microbial antigens bound to IgA. Based on our data, we propose that assessment of CFHR1 levels associated with IgA-ICs will provide new insights into nephritogenic potential of IgA-ICs and enable to determine the impact of drugs in clinical trials on these complexes.

The majority of IgA in the body is produced by mucosal-associated lymphoid tissues, with 3–5 g of IgA secreted daily into the intestinal lumen, where it plays an important role as the first line of defense against microbial invasion23. Complement C1q, found at elevated levels in the IgA-ICs of patients with IgAN, is essential for recognizing antigen-bound immunoglobulins24.

The presence of elevated levels of C1q, the initiating component of the classical pathway, and CFHR1 and properdin, the proteins involved in the alternative pathway, in IgA-ICs open a question on the respective roles of classical, alternative, and terminal pathways after the deposition of IgA-ICs in the glomeruli. Indeed, classical pathway components (e.g., C1q, C1r, C4a, and C4b) and alternative-pathway regulators (CFHR1, 2, and 5) exhibited a greater abundance in the glomeruli of patients with IgAN than controls, along with the components of the terminal pathway. CFHRs compete with CFH and to prevent C3b inactivation, thus contributing to the amplification of the alternative pathway.

CFHRs are members of the CFH protein family, comprising CFHR1-5. CFH consists of 20 short consensus repeats (SCRs), with N-terminal SCRs 1–4 mediating the strong complement regulatory activity and SCRs 6–7 and 19–20 acting as ligand-binding and surface recognition sites25,26. Although these ligand-binding and surface recognition sites are retained in CFHRs with varying degrees of conservation, homologs of the complement regulatory domains are absent in CFHRs. While the precise functions of CFHRs remain incompletely understood, accumulating evidence suggests that some CFHRs modulate complement activity by competing with CFH for C3b binding25. CFH is a cofactor for complement factor I, the protease necessary to generate iC3b. Due to the high degree of similarity between the SCR1-2 domains of CFHR1, CFHR2, and CFHR5, these proteins can form homo- and heterodimers, that could interfere with CFH-mediated C3b inactivation27.

CFHR1-5 proteins are encoded by the corresponding genes, FHR1–FHR5, which are in the proximity to the gene encoding factor H (CFH) on human chromosome 1q3228. A recent genome-wide association study identified IgAN susceptibility loci on 1q32 and detected rs6677604 as the top SNPs in CFH and CFHR3-1 deletion (CFHR3-1Δ) as the top copy number variation signal29. Interestingly, the rs6677604-A allele and CFHR3-1Δ were in strong linkage disequilibrium and associated with lower complement activation in glomeruli. The CFHR3-1Δ allele has protective effects in both age-related macular degeneration and IgAN30,31. Genetic variants in CFHR5 have also been shown to contribute to IgAN susceptibility32. Furthermore, circulating CFHR1 and CFHR5 levels contribute to IgAN development, activity, and progression33,34, and elevated amount of glomerular CFHR5 correlates with IgAN progression15.

However, the contributions of CFHRs have been reported in C3 glomerulopathy and atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome which is induced by complement dysregulation, and also reported in other ICs-mediated glomerulonephritis, such as systemic lupus erythematosus with nephritis35,36. Therefore, the findings of this study merely suggest the possibility of CFHRs modulating complement in IgAN glomeruli; comparison with disease controls will be essential to demonstrate its disease-specific nature.

Our proteomic analyses revealed a compartment-specific distribution of CFHR1 and CFHR2,3,5. CFHR1,2,3,5 proteins were detected in the glomeruli of patients with IgAN, with CFHR3 exhibiting higher levels in those receiving immunosuppressive therapy compared to those on supportive therapy. In contrast, CFHR1, but not CFHR2,3,5, was elevated in IgA-ICs of patients with IgAN. CFHRs are mainly produced by hepatocytes and released into the systemic circulation. However, they can be expressed by some immune cells, including macrophages in the restricted situation, according to human protein atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org) and previous reports37,38. Elevated CFHR3 expression in glomeruli may be caused by other mechanisms not involving IgA-ICs, such as alternation of glomerular microenvironment induced by extracellular-matrix organization, proliferation of mesangial cells, or accumulated macrophage. It is necessary to clarify the localization of CFHRs within the glomerular components and pathways leading to the overexpression of these complement-regulating proteins.

The present study has several limitations. First, a relatively small number of patients with IgAN and disease controls for the comparative IgA-ICs and glomerular proteomics limits the generalizability of our findings. To more robustly demonstrate the involvement of CFHR1 and CFHR3 in the pathogenesis of IgAN, it is necessary to revalidate these findings in a larger, separate cohort using immunohistochemical techniques and ELISA methods. Furthermore, the relationship between long-term renal outcomes and the degree of renal deposition in CFHRs will need to be explored in future studies. Second, although this study demonstrated the presence of components of the classical, alternative, and terminal complement pathways, we believe this does not exclude the involvement of the lectin pathway. Previous studies have reported lectin-pathway involvement in IgAN based on immunohistochemistry and functional assays18,19,39. Several factors may account for the lack of detection due to the abundance and nature of target proteins and sensitivity threshold of mass spectrometry. Third, the mechanism by which CFHR1 abundance in IgA-ICs is reduced by immunosuppressive treatment remains unclear. The effectiveness of immunosuppressive treatment versus tonsillectomy has not been elucidated, as only a small number of patients underwent tonsillectomy alone. As CFHRs may be influenced by genetic factors, it would be valuable to validate the current findings across diverse ethnic groups in future studies.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that some complement proteins were more abundant in the glomeruli of patients with IgAN compared with controls, including proteins from the classical, alternative, and terminal pathways of the complement cascade, including complement-regulating proteins CFHR1, CFHR2, CFHR3, and CFHR5. IgA-ICs of IgAN patients contained also some of these complement-associated proteins, including CFHR1, properdin, and C1q. Notably, immunosuppressive therapy led to disease remission that was associated with reduction of CFHR1 associated with IgA-ICs, pointing to the role of complement and complement regulatory proteins in the pathogenesis of IgAN. Moreover, CFHR1 in IgA-ICs may also serve as a novel biomarker for complement-modulating therapies in IgAN.

Methods

Biospecimens: serum and remnant kidney tissues

In accordance with the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines for IgAN and IgA vasculitis, two treatment groups were investigated, I: immunosuppressive therapy group (which manage the IgAN-specific drivers for nephron loss; i.e., tonsillectomy combined with pulse steroid therapy) and II: supportive therapy group (which manage the genetic response to IgAN-induced nephron loss; i.e., comprehensive supportive therapy including RASI). Treatments were determined according to the treatment-selection flowchart, and patients with IgAN who received immunosuppressive therapy (i.e., tonsillectomy combined with pulse steroid therapy) or only comprehensive supportive therapy were included (Supplementary Figure S2a). Corticosteroid therapy was performed based on the Pozzi protocol modified for Japanese patients40,41; i.e., methylprednisolone (0.5 g) was administered intravenously for three consecutive days at the beginning of the steroid course, and this regimen was repeated after two and four months; oral prednisone (0.5 mg/kg) was administered every other day for six months. All the patients received comprehensive supportive therapy that included RASI to lower blood pressure to a target below 125/75 mm Hg.

Serum samples from patients with primary IgAN were collected at various time points, including at diagnosis and 2 years after diagnosis (Supplementary Figure S2b). Serum samples were aliquoted and stored at − 80 °C. Samples from disease controls were collected at diagnosis after obtaining informed consent, and the samples were stored under identical conditions. Samples from healthy volunteers whose age and sex are comparable with IgAN group were collected after obtaining informed consent. Biospecimens from each group were randomly selected from the pool of available samples; details are provided in Supplementary Tables S6 and S11.

Patient-eligible flow chart for the proteomic comparison of IgA-IC components between patients with IgAN and HCs and for longitudinal proteomic analysis of the components of IgA-ICs across different treatment groups are shown in Supplementary Figure S2c, d.

Stored remnant FFPE kidney tissues from patients with IgAN diagnosed in FHU were processed for LMD. Control kidney tissues purchased from OriGene Technologies (Rockville, MD, USA) were from normal segments of kidneys removed due to cancer (Supplementary Table S2). Since a total of 80 glomerular cross sections per patient were required for the proteomic analysis, it was not possible to include all patients used for IgA-ICs analysis in the glomerular proteomic analysis. From IgAN patients diagnosed between 2020 and 2022, one primary IgAN patients treated with immunosuppressive therapy and eight patients treated with supportive therapy were included. Overlapping biospecimens of patients used for proteomic analysis for glomeruli and IgA-ICs are detailed in Supplementary Figure S3.

Laser microdissection and sample Preparation for mass spectrometry analysis

FFPE kidney Sect. (10-µm thick) were mounted on polyethylene naphthalate membrane glass slides (11505158, Leica, Wetzlar, Hesse, Germany). Tissue sections were deparaffinized, stained with hematoxylin, rinsed, and air-dried. A total of 80 glomerular cross-sections were laser microdissected using the LMD 6000 system (Leica, Wetzlar, Hesse, Germany).

The protein extraction from the collected cross-sections of glomeruli was performed according to a modification of previously published protocol42. For extraction and uncross-link of proteins and fragmentation of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), microdissected tissues were heated with 100 µl of lysis buffer (containing 12 mM sodium deoxycholate, 12 mM sodium lauroyl sarcosinate, 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, and protease inhibitor ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-free cocktail (11873580001, Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA), [pH 8.0]) at 99 °C for 60 min, followed by sonication at 4 °C for 30 min using a Bioruptor UCD-250 (BM Equipment Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Protein quantification was performed using the Micro BCA kit (23235, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Two micrograms of glomerular protein extracted from each sample was reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol at 25 °C for 30 min and alkylated with 55 mM iodoacetamide at 25 °C for 30 min in the dark. Each sample was prepared for proteomic analysis according to the single-pot, solid-phase-enhanced sample preparation protocol43. In this process, proteins were bound to Sera-Mag SpeedBeads (45152105051150, 65152105051150, GE Healthcare), washed with 80% ethanol, and digested with Trypsin/Lys-C Mix (1:50, w/w) (Promega, Madison, WV, USA, V507A) in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate at 37 °C [pH 8.0] with continuous mixing at 1000 rpm overnight in a ThermoMixer C (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The digested samples were acidified with trifluoroacetic acid (13972; Kanto Kagaku Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and desalted using GL-Tip-SDB (7820–11200, GL Science, Tokyo, Japan).

Purification of IgA and sample Preparation for mass spectrometry

IgA was purified from 100 µl of serum from patients with IgAN and healthy controls (HCs) using affinity chromatography with an anti-human IgA antibody (0855068, Cappel Laboratories, Cochranville, PA, USA) immobilized on a HiTrap NHS-activated High Performance column (17071601, GE HealthCare, Chicago, IL, USA), as described previously44,45. The median recovery in IgA purification was 73.4% (63.1–87.1%). The purified samples were aliquoted and stored at − 80 °C. With this process, IC-associated proteins were also pulled -down and 5 µg of purified IgA proteins was used for the MS analysis for IgA-IC analysis.

Protein identification in glomerular extracts and IgA-ICs using LC–MS

Tryptic peptides (300 ng for glomeruli and 500 ng for IgA-ICs) were analyzed via liquid chromatography coupled with Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The peptides were loaded onto an EASY-nLC 1000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a trap column (Acclaim PepMap 100 C18 LC column, 3 μm, 75 μm ID × 20 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific) equilibrated with 0.1% formic acid. Elution was performed using a linear gradient consisting of 0%–35% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid over 120 min at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. The eluted peptides were separated on an EASY-Spray C18 LC column (75 μm × 15 cm, 3 μm, 100 Å, Thermo Fisher Scientific). A hybrid quadrupole mass filter/linear ion trap/Orbitrap MS was employed, alternating between a full Orbitrap MS scan (m/z 375–1500 for glomeruli and 500–1700 for IgA-ICs) at a resolving power of 120000 and an S-lens radio frequency of 60%, and subsequent MS/MS scan of the abundant precursor ions.

Analysis of MS/MS data and differential analysis of proteins detected by MS

The MS/MS data were analyzed using Mascot (Matrix Science, London, UK) and SEQUEST HT search algorithms against the UniProtKB Homo sapiens protein database (version 2022-03-30 and 2023-05-03) utilizing Proteome Discoverer 2.4 (version 2.4.0.305 and 2.4.1.15, respectively; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The workflow included spectrum file RC, spectrum selector, Mascot, SEQUEST HT search nodes, percolator, IMP-ptmRS, and Minora Feature Detector nodes. The mass tolerance levels were set to 10 ppm for MS and 0.6 Da for MS/MS. Trypsin was specified as the protease, with up to two missed cleavages allowed. The false discovery rate was controlled at 1% using target-decoy database searches46.

Label-free quantification was performed using Proteome Discoverer 2.4 with precursor ion quantifier nodes. Differential analysis of the relative abundance of peptides and proteins between samples was conducted using Perseus software (version 1.6.15.0; Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Martinsried, Bavaria, Germany). The protein abundance values were converted to a Log2 scale. Only proteins detected in 70% of the samples from at least one group were included in the analysis. Normalization was performed by subtracting the median of each sample. Missing values were imputed based on a normal distribution (width = 0.3, downshift = 1.8). Significance was assessed using t-test analysis. An unadjusted P value of less than 0.05 and an absolute value of Log2 (fold change, FC) of greater than 0.58 were considered significant, as the primary aim of this analysis was to identify candidate proteins for further biological validation. To further ensure the reliability of our findings, we confirmed that a subset of proteins also passed FDR < 0.05 (s0 = 0.1) in Perseus.

STRING analysis

Clustering analysis and visualization of functional and physiological interactions of the genes were performed using STRING version 12.0 (https://string-db.org/).

Immunofluorescence in renal tissues

For the analysis, frozen renal biopsy tissues obtained from the patients with IgAN and human kidney frozen tissue block (CB520344) (Supplementary Table S2) acquired from OriGene Technologies (Rockville, MD, USA) was used as controls. Frozen tissues were sliced in 3-µm sections and fixed in acetone at − 20 °C for 10 min. The slides were blocked with 10% normal goat serum (S1000, Vector Laboratories, Newark, CA, USA) at 25 °C for 1 h and then incubated with anti-CFHR1 antibody (HPA040726, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as the primary antibody at a 1:100 dilution in Can Get Signal Immunostain (NKB-601, Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) at 4 °C overnight. After several washes, the slides were incubated with Alexa Fluor™ 594-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (A-11058, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at a 1:3000 dilution in Can Get Signal Immunostain at 25 °C for 1 h in darkness. Slides were then washed thoroughly and incubated with a rabbit anti-IgA-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antibody (F0204, DAKO, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at a 1:100 dilution in 10% normal goat serum at 4 °C for 1 h. For the negative controls, an identical protocol was followed, but the primary antibody was replaced with PBS. Slides were then mounted with ProLong™ Gold Antifade reagent (P36930, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), and images were obtained using a fluorescence microscope (BZ-X800, KEYENCE, Osaka, Japan).

Measurement of serum CFHR1 levels and the amount of CFHR1 contained in IgA-ICs

The concentration of serum CFHR1 was measured using an ELISA kit (ELH-CFHR1, RayBio, Norcross, GA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For measurement of the amount of CHFR1 associated with IgA-ICs, the IgA concentration of IgA-ICs was initially measured using a separate ELISA kit (88-50600, Invitrogen, Waltham, Massachusetts, US). Then, its concentration was standardized to 10 µg/ml, and 100 µl of each sample was added to the appropriate wells of CFHR1 ELISA kit. The CFHR1 concentration in IgA-ICs was determined based on a standard curve (ng/ml), and the final data were expressed as ng of CFHR1 per 10 µg of IgA (ng/IgA 10 µg).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analyses and graphing were carried out using GraphPad Prism 9. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Continuous variables were expressed as the medians (interquartile ranges). Comparisons between two groups were performed using Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, depending on the distribution of variables. Paired groups were compared using the paired t-test or Wilcoxon test, based on the normality of data. Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was employed to assess the strength of the relationships between the variables. The Kruskal-Wallis test followed by post-hoc Dunn’s test was used for multiple comparisons. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

References

McGrogan, A., Franssen, C. F. & de Vries, C. S. The incidence of primary glomerulonephritis worldwide: A systematic review of the literature. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 26, 414–430 (2011).

Lai, K. N. et al. IgA nephropathy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2, 16001 (2016).

Suzuki, H. et al. The pathophysiology of IgA nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 22, 1795–1803 (2011).

Novak, J. et al. IgA1 immune complexes from pediatric patients with IgA nephropathy activate cultured human mesangial cells. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 26, 3451–3457 (2011).

Ponticelli, C. et al. Kidney transplantation in patients with IgA mesangial glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 60, 1948–1954 (2001).

Tomana, M. et al. Galactose-deficient IgA1 in sera of IgA nephropathy patients is present in complexes with IgG. Kidney Int. 52, 509–516 (1997).

Tomana, M. et al. Circulating immune complexes in IgA nephropathy consist of IgA1 with galactose-deficient hinge region and antiglycan antibodies. J. Clin. Invest. 104, 73–81 (1999).

Suzuki, H. et al. Aberrantly glycosylated IgA1 in IgA nephropathy patients is recognized by IgG antibodies with restricted heterogeneity. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1668–1677 (2009).

Rizk, D. V. et al. Glomerular immunodeposits of patients with IgA nephropathy are enriched for IgG autoantibodies specific for galactose-deficient IgA1. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 30, 2017–2026 (2019).

Matsumoto, Y. et al. Identification and characterization of circulating immune complexes in IgA nephropathy. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm8783 (2022).

Katafuchi, R., Nagae, H., Masutani, K., Tsuruya, K. & Mitsuiki, K. Comprehensive evaluation of the significance of immunofluorescent findings on clinicopathological features in IgA nephropathy. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 23, 169–181 (2019).

Eison, T. M. et al. Association of IgG co-deposition with serum levels of galactose-deficient IgA1 in pediatric IgA nephropathy. Clin. Nephrol. 78, 465–469 (2012).

Maillard, N. et al. Current understanding of the role of complement in IgA nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26, 1503–1512 (2015).

Murphy, B., Georgiou, T., Machet, D., Hill, P. & McRae, J. Factor H-related protein-5: A novel component of human glomerular immune deposits. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 39, 24–27 (2002).

Medjeral-Thomas, N. R. et al. Progressive IgA nephropathy is associated with low circulating mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease-3 (MASP-3) and increased glomerular factor H-related protein-5 (FHR5) deposition. Kidney Int. Rep. 3, 426–438 (2018).

Onda, K. et al. Excretion of complement proteins and its activation marker C5b-9 in IgA nephropathy in relation to renal function. BMC Nephrol. 12, 64 (2011).

Wang, Y. et al. The prognostic role of activation of the complement pathways in the progression of advanced IgA nephropathy to end-stage renal disease. BMC Nephrol. 25, 387 (2024).

Roos, A. et al. Glomerular activation of the lectin pathway of complement in IgA nephropathy is associated with more severe renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17, 1724–1734 (2006).

Espinosa, M. et al. Association of C4d deposition with clinical outcomes in IgA nephropathy. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 9, 897–904 (2014).

Novak, L. et al. Kidney injury and colocalization of complement C3, IgA, and IgG in glomerular immune-complex deposits of patients with IgA nephropathy or IgA vasculitis with nephritis. Kidney Int. 108, 1158–1169 (2025).

Paunas, T. I. F. et al. Glomerular abundance of complement proteins characterized by proteomic analysis of laser-captured microdissected glomeruli associates with progressive disease in IgA nephropathy. Clin. Proteom. 14, 30 (2017).

Tan, L. et al. A multicenter, prospective, observational study to determine association of mesangial C1q deposition with renal outcomes in IgA nephropathy. Sci. Rep. 11, 5467 (2021).

Barratt, J. et al. Why target the gut to treat IgA nephropathy? Kidney Int. Rep. 5, 1620–1624 (2020).

Fujita, T. Evolution of the lectin-complement pathway and its role in innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 346–353 (2002).

Cserhalmi, M., Papp, A., Brandus, B., Uzonyi, B. & Jozsi, M. Regulation of regulators: Role of the complement factor H-related proteins. Semin Immunol. 45, 101341 (2019).

Jozsi, M., Tortajada, A., Uzonyi, B., Goicoechea de Jorge, E. & Rodriguez de Cordoba, S. Factor H-related proteins determine complement-activating surfaces. Trends Immunol. 36, 374–384 (2015).

de Goicoechea, E. et al. Dimerization of complement factor H-related proteins modulates complement activation in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 110, 4685–4690 (2013).

Perez-Caballero, D. et al. Clustering of missense mutations in the C-terminal region of factor H in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 478–484 (2001).

Zhu, L. et al. Variants in complement factor H and complement factor H-related protein genes, CFHR3 and CFHR1, affect complement activation in IgA nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26, 1195–1204 (2015).

Hughes, A. E. et al. A common CFH haplotype, with deletion of CFHR1 and CFHR3, is associated with lower risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Genet. 38, 1173–1177 (2006).

Gharavi, A. G. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for IgA nephropathy. Nat. Genet. 43, 321–327 (2011).

Zhai, Y. L. et al. Rare variants in the complement factor H-related protein 5 gene contribute to genetic susceptibility to IgA nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 2894–2905 (2016).

Zhu, L. et al. Circulating complement factor H-related protein 5 levels contribute to development and progression of IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 94, 150–158 (2018).

Medjeral-Thomas, N. R. et al. Circulating complement factor H-related proteins 1 and 5 correlate with disease activity in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 92, 942–952 (2017).

Zhao, J. et al. Association of genetic variants in complement factor H and factor H-related genes with systemic lupus erythematosus susceptibility. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002079 (2011).

Zipfel, P. F., Wiech, T., Stea, E. D. & Skerka, C. CFHR gene variations provide insights in the pathogenesis of the kidney diseases atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and C3 glomerulopathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 31, 241–256 (2020).

Schafer, N. et al. Complement regulator FHR-3 is elevated either locally or systemically in a selection of autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 7, 542 (2016).

Schafer, N. et al. Complement factor H-related 3 enhanced inflammation and complement activation in human RPE cells. Front. Immunol. 12, 769242 (2021).

Roos, A. et al. Human IgA activates the complement system via the mannan-binding lectin pathway. J. Immunol. 167, 2861–2868 (2001).

Pozzi, C. et al. Corticosteroid effectiveness in IgA nephropathy: Long-term results of a randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 15, 157–163 (2004).

Ogura, S., Moriyama, T., Miyabe, Y., Karasawa, K. & Nitta, K. Evaluation of appropriate treatment for IgA nephropathy with mild proteinuria and normal renal function. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 25, 1103–1110 (2021).

Wakabayashi, M. et al. Phosphoproteome analysis of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue sections mounted on microscope slides. J. Proteome Res. 13, 915–924 (2014).

Hughes, C. S. et al. Single-pot, solid-phase-enhanced sample Preparation for proteomics experiments. Nat. Protoc. 14, 68–85 (2019).

Ohyama, Y. et al. Analysis of O-glycoforms of the IgA1 hinge region by sequential deglycosylation. Sci. Rep. 10, 671 (2020).

Ohyama, Y. et al. Racial heterogeneity of IgA1 hinge-region O-glycoforms in patients with IgA nephropathy. iScience 25, 105223 (2022).

Zhong, Z. et al. Proteomic analysis of irradiation with millimeter waves on soybean growth under flooding conditions. Int J. Mol. Sci 21, 486 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Miho Tanaka for her cooperation in the LC-MS analysis and Ms. Akiho Ikuta, Ms. Ikumi Matsui and Ms. Maki Okada for providing assistances in the purification of IgA from the patient’s serum.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI) (grant numbers: 20K08623, 20K22915, 22K08366, 22K16253, and 23K07729), Hori Sciences and Arts Foundation, Yukiko Ishibashi Foundation, and Aichi Jinzou Foundation. JN is supported in part by UAB research-acceleration funds and a gift from IGA Nephropathy Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.T. and Y.O. contributed equally to this study Y. T., Y. O., S. S., T. E., M. H., H. Y., and T. N. performed the experiments. Y. T., Y. O., S. S., T. E., T. M., N. T., J. N., and K. T. designed the experiments. Y. T., Y. O., S. S., T. E., H.Y., and T. N. analyzed the data. Y. T., Y. O., T. M., J. N., and K. T. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

KT received research funding from Oriental Yeast Co., Ltd. JN is a co-founder and co-owner of and consultant for Reliant Glycosciences, LLC. JN is a co-inventor on US patent application 14/318,082 (assigned to The UAB Research Foundation [UABRF] and licensed by UABRF to Reliant Glycosciences, LLC). Since 2024, JN received honoraria from Calliditas, Travere, Novartis, and Vera Therapeutics. All other authors declared no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All experimental protocols were approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Fujita Health University (approved number HM22-140) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Patients who were diagnosed by kidney biopsy at the Department of Nephrology, Fujita Health University School of Medicine (FHU) (Toyoake, Japan) between January 2017 and December 2022 were included.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsuji, Y., Ohyama, Y., Saitoh, S. et al. Complement proteins associated with circulatory and glomerular IgA-containing immune complexes in patients with IgA nephropathy. Sci Rep 15, 45375 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29024-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29024-z