Abstract

Diagnostic and therapeutic drug monitoring are necessary means of precision medicine. Our previous study demonstrated that the sponge Haliclona sp. spicules (SHS) can be employed as a new class of microneedles, capable of forming a substantial number of microchannels within the skin. In this study, dermal interstitial fluid (ISF) was obtained via percutaneous extraction using sponge Haliclona sp. spicules (SHS) to explore the correlation between the concentration of target compounds in the extract and their content in the skin or blood. Methodologically, we compared SHS with dermaroller, ultrasound, and reverse iontophoresis for interstitial fluid (ISF) extraction efficacy in vitro, while optimizing extraction parameters (dosage of SHS, extraction solvent, extraction time) via orthogonal experimental design. Target compounds spanning diverse physicochemical properties (fluorescein sodium, rhodamine B, salicylic acid, FD 1 k, urea, glucose) were evaluated. We also detected the concentration of target compounds and their levels in the blood in vivo. Key results showed that robust linear correlations were observed between the detected concentration of target compounds through SHS and their levels in various skin layers, as well as in the blood. Additionally, we developed a mathematical model predicting extraction efficiency log kp = 2.9711 + 0.00235MV − 0.059526 log P + 6.7506 log MW−0.6. These findings provide a new non-invasive percutaneous sampling strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Disease diagnosis was crucial for evaluating a patient’s physical condition and represented a vital step preceding treatment1,2,3. Each disease was characterized by unique biomarkers, and vigilance was essential when molecular abnormalities manifest in the body, signaling potential disease occurrence4. For instance, individuals with elevated homocysteine levels faced more than a threefold increased risk of heart disease5. Similarly, those with chronic kidney disease often exhibited heightened levels of urea and creatinine6. Consequently, the detection of endogenous molecule levels in the body became paramount for disease prevention. Therapeutic drug monitoring played a pivotal role in disease treatment. Through extensive pharmacokinetic studies, it was established that individuals vary in their drug absorption levels. Particularly for drugs with a narrow therapeutic window, relying solely on dosage for predicting therapeutic effects can be perilous7,8,9,10. Hence, the importance of therapeutic drug monitoring garnered increasing attention. This monitoring practice entailed the measurement of drug concentrations in body fluids during clinical procedures, allowing for continuous dose adjustments based on monitoring outcomes to achieve optimal therapeutic effects11,12,13. Given the rapid advancement of medical technology today, therapeutic drug monitoring held great promise.

Due to the skin barrier derived from stratum corneum, ones cannot directly obtain concentration information of therapeutics or endogenous molecules in the body14,15,16. Blood sampling was the most common method17,18, but it carried the potential for disease transmission due to repeated needle use19. Additionally, needle phobia in some individuals may lead to treatment refusal. Moreover, blood sampling generated hazardous waste, incurring additional disposal costs20. A range of non-invasive sampling methods were also developed and employed. Some methods initially designed for percutaneous drug delivery showed potential for monitoring. Microneedles21,22,23,24, for example, increase skin permeability by creating physical channels, facilitating the flow of drug molecules in and out of the skin. However, they were limited by the difficulty of design21,25. Ultrasound technology was another commonly used means for percutaneous monitoring26,27,28. Utilizing cavitation29, thermal30, and acoustic flow31 effects on tissues and cells, it enhanced drug entry and exit. While successful in practice, its main drawback was the time-consuming process. Reverse iontophoresis, successfully employed in percutaneous monitoring32,33,34,35,36, induces electro-migration and electro-osmosis in the skin37,38. Nevertheless, its application required calibration, effects vary among different populations with varying skin thickness, and endogenous molecular competition was a significant factor38,39. In previous research, we discovered that sponge Haliclona sp. spicules (SHS),which were collected from explants in Dongshan Bay, Fujian, China, can create numerous skin channels (around 103 channels per mm2 when topically applied at a dosage of 0.05 mg/mm2) and consequently increase skin permeability, promoting the penetration of drug molecules into the skin40,41,42. Furthermore, SHS can be applied to any desired skin area, naturally detaching within 72 h, sparking our interest in its potential application in percutaneous monitoring.

In this study, we compared the effectiveness of SHS with dermaroller, ultrasound, and reverse iontophoresis in percutaneous extraction. We found that SHS significantly increased the exudation of target compounds in a short time. Simultaneously, we evaluated the factors influencing the extraction effect of SHS and identified the optimal percutaneous monitoring conditions. Further, we utilized SHS for the percutaneous extraction of various target compounds and examined the association between the identified concentration of these target compounds and their respective levels within different skin layers as well as in the blood.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and animals

Rhodamine B, fluorescein sodium, and salicylic acid were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA), Cat. No. R6626, Purity ≥ 95% (HPLC). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran with a molecular weight of 1,000 Da (FD 1 K) and 2000 Da (FD 2 K) was obtained from Zancheng Technology Co., LTD (Tianjin, China). Glucose, urea, Cyclosporin A, glucose testing kits, and urea nitrogen testing kits were purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China), Cat. No. SC5120, Purity ≥ 98% (HPLC). Isoflurane for scientific research was acquired from Rayward Life Technologies Inc (Shenzhen, China). The blood sugar test kit was obtained from Sinocare Inc. (Changsha, China), and heparin lithium was procured from Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Male Sprague Dawley rats (6–8 weeks old), BALB/c rats and C57BL/6 J rats were procured from Shanghai Slack Laboratory Animal Co., LTD (Shanghai, China). All animal experimental procedures were reviewed by the Xiamen University Laboratory Animal Management and Ethics Association and conducted in accordance with relevant national regulations (Ethics Approval No. XMULAC20240217). The study followed all ARRIVE guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Preparation and purification of SHS

The sponge Haliclona sp., cultured at Dongshan Bay (Fujian, China) in 2021, was used as the raw materials for SHS. Purified SHS was obtained using the method described in our patent (ZL201610267764.6). SHS samples (100 mg) were subjected to sequential ultrasonic washing with 0.1 mol/L NaOH (5 mL) and HCl (5 mL) for 30 min each, followed by rinsing with deionized water. Subsequently, acetonitrile (5 mL) was used for further ultrasonic cleaning for 30 min, and the samples were finally lyophilized using a vacuum freeze dryer.

In vitro percutaneous extraction studies

Fresh dorsal skin from young porcine (procured from YinXiang Group, Xiamen, China) was shaved to a length no longer than 2 mm using an electric razor (Yizu DDG-S02, Zhejiang, China) for in vitro percutaneous extraction studies. The skin was subjected to cryopreservation at a temperature of − 20 °C and defrosted before use. Skin disk samples were obtained using a punch with a diameter of 36 mm, and the subcutaneous fat layer was excised using a scalpel. After washing with ultrapure water, the skin was placed in vertical Franz diffusion cells (procured from FDCs, ZhengTong, Tianjin, China). In the receptor chamber of the Franz diffusion cell, 12 mL of a target compound solution dissolved in saline was added. The entire device was bathed in water at 37 °C for a designated period. The resulting skin model contained the target compound, and the effective extraction area was 177 mm241.

Afterwards, we obtained the dermal interstitial fluid (ISF) using different strategies. For the SHS group, 10 mg/177 mm2 of SHS was applied topically to the skin, which was then electrically massaged for 2 min with an electric massager operating at 0.3 N force and 300 rpm frequency. The skin was then washed twice with pure water to remove surface residue. In the dermaroller group, a dermaroller device (model HC902, 0.2 mm, 162 microneedles, Munich, Germany) was used to treat the dermal surface., it was rolled horizontally, vertically, and diagonally across the skin for 8 times. For the ultrasound group, 4 mL of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate solution was applied to the skin, followed by placement of the entire Franz diffusion cell in an Ultrasonic Cell Crusher (ATPIO, Nanjing, China). A 20 kHz ultrasonic wave with a 2-s on/off pulse was applied for 90 s, using a horn positioned approximately 3 mm from the skin surface. For the reverse iontophoresis group, 0.3 mL of saline was applied to the surface of the skin. The Cu electrode was positioned within the receptor chamber, while the Ag/AgCl electrode was situated within the donor chamber. The applied voltage was 4 V, with an extraction time of 2 min. Finally, 0.3 mL of buffer was administered to the skin surface for extraction for 2 min, and the extracted solution was collected for target compound concentration analysis. To analyze the content of target compounds in different skin layers, the stratum corneum was obtained via the tape-stripping method. The stratum corneum was separated from the underlying dermis using a scalpel, with the latter structure left intact. Subsequently, the dermis was divided into smaller sections. These layers were then soaked in a methanol/PBS solution and extracted for 24 h, yielding a solution suitable for analysis.

In vivo percutaneous extraction studies

To further verify the relationship between the detected concentration of target compounds and their levels in the blood, we chose Sprague Dawley rats (6–8 weeks old, male) as experimental animals, with salicylic acid and glucose serving as hydrophilic model molecules. For salicylic acid, its solution injected in the experiment was 10%, and the initial concentrations were established at 5 g/kg (w/w), 4 g/kg (w/w), 3 g/kg (w/w), 2 g/kg (w/w), and 1 g/kg (w/w). For glucose, its solution injected in the experiment was 2 mg/mL, and the initial concentrations were set at 20 mg/kg (w/w), 15 mg/kg (w/w), 10 mg/kg (w/w), 5 mg/kg (w/w), and 1 mg/kg (w/w). The concentration of the target compounds in SD rats was increased to the initial concentration through the intravenous administration of the target compound solution. The extraction procedure was then conducted on SD rats at 30 min following the intravenous injection. SD rats were anesthetized with isoflurane through a gas anesthesia machine, and their backs were carefully shaved. Thereafter, a 177 mm2 hollow cylinder was affixed to the backs of the rats via the application of cyanoacrylate adhesive. 10% (w/v) glucose solution or 2 mg/mL salicylic acid solution was administered intravenously. Subsequently, a precise dose of SHS was applied to the skin. The skin was electrically massaged for 2 min, after which it was washed twice with pure water to remove any surface residue. Finally, 0.3 mL of saline was applied to the surface of the skin for extraction over a designated period, and the extracted solution was collected for the detection of the target compound concentration. Simultaneously, 0.5 mL of blood was collected from SD rats by tail-breaking.

To observe the changes in the detected salicylic acid concentration over time, we gave SD rats an intravenous injection of 2 mg/mL salicylic acid solution to bring the concentration of salicylic acid in SD rats to 20 mg/kg (w/w). Subsequently, the identical extraction procedure previously outlined was conducted at 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 min post-injection.

We also explored the relationship between the detected concentration of cyclosporin A and their levels in the blood. The BALB/c mice acted as the donors, and the C57BL/6 J mice acted as the recipients. Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane via a gas anesthesia machine. Skin grafts (10 mm in diameter) were harvested from the backs of BALB/c mice and transplanted onto C57BL/6 J recipients. Each group included at least three mice. The experimental group received daily intraperitoneal injections of cyclosporin A (15 mg/kg), while the control group was not subjected to any form of treatment. Percutaneous extractions (using DMSO as the solvent) and blood samples were obtained at 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 days post-injection, with each extraction lasting 2 h.

Analytical method

The contents of rhodamine B, sodium fluorescein, salicylic acid, and FD 1 k in the collected solution were evaluated through the utilization of fluorescence spectroscopy (Tecan Infinite 200PRO, Männedorf, Switzerland). The presence of Rhodamine B was confirmed at an excitation wavelength of 355 nm and an emission wavelength of 580 nm. The standard curve exhibited a range from 0.05 to 100 ng/mL (R2 = 0.9998), 0.1–500 ng/mL (R2 = 0.9992), 0.1–100 ng/mL (R2 = 0.9999), 0.1–100 ng/mL (R2 = 0.9998) in methanol/PBS, NaCl, NaCl containing 1% Tween 80, NaCl containing 5% Tween 80, respectively. The presence of sodium fluorescein was confirmed at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 535 nm. The standard curve ranged from 0.001 to 0.05 μg/mL (R2 = 0.9999) and from 0.001 to 0.1 μg/mL (R2 = 0.9983) in methanol/PBS and NaCl, respectively. Salicylic acid was identified at an excitation wavelength of 308 nm and an emission wavelength of 396 nm. The standard curve exhibited a range of 0.01–2.5 μg/mL (R2 = 0.9996) and 0.01–2.5 μg/mL (R2 = 0.9999) in methanol and PBS, respectively, with NaCl. Fluorescence detection of FD 1 k was observed at an excitation wavelength of 490 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm. The standard curve ranged from 0.01 to 100 ng/mL (R2 = 0.9999), 1–1000 ng/mL (R2 = 0.9964) in methanol/PBS, NaCl, respectively. The contents of urea and glucose in the collection solution were determined using the detection kit.

Cyclosporin A was analyzed using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS). The analysis was conducted using an Agilent 1290 Infinity LC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), with separation achieved using a Hypersil GOLD™ C18 column (1.9 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm). The mobile phase comprised 85% aqueous methanol containing 5 mmol/L ammonium acetate and 0.1% formic acid, with a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min and an injection sample volume of 0.01 mL. Electrospray ionization was conducted in positive ion mode. Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) was employed with precursor/product ion pairs of 1219.6/1202.7 m/z for the analysis of Cyclosporin A. The ion spray voltage was calibrated at 4 kV, and the source temperature was maintained at 200 °C. The demonstrated method exhibited linearity over the concentration range of 1.0–1,500.0 ng/mL, with a calculated correlation coefficient of 0.9982.

Data analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SD. The statistical significance of the findings was determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test, with p < 0.05 considered indicative of a significant difference. The orthogonal experimental data were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.

Results

Percutaneous extraction using SHS in vitro

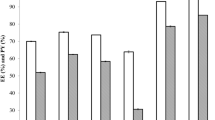

To assess the effectiveness of SHS in percutaneous extraction, sodium fluorescein was employed as a model drug, and the extraction effects of SHS were compared with reverse iontophoresis, dermaroller, and ultrasound (Fig. 1). The results revealed that the amount of sodium fluorescein extracted from the skin by SHS (4433.97 ± 1208.99 ng/mL) was significantly higher than that in the other groups, being 12.47 ± 3.39 times that of the reverse iontophoresis group (p < 0.01), 8.49 ± 1.28 times that of the microneedle roller group (p < 0.01), and 9.32 ± 2.55 times that of the ultrasound group (p < 0.01). These findings highlight the effective capability of SHS in extracting target compounds percutaneously from the skin.

In order to further explore the optimal percutaneous extraction conditions of SHS, we conducted a study using a three-level and three-factor orthogonal experimental design with rhodamine B as the model molecule (Supplementary Fig. S1). The results indicated that the amount of SHS, percutaneous extraction time, and extraction solvent significantly influenced the extraction efficiency of target compounds. Considering the practical application and patient compliance, we aimed to achieve the highest percutaneous extraction efficiency in a short time. Therefore, we adopted the SHS percutaneous extraction protocol with a dosage of 0.05 mg SHS/mm2, saline as the extraction solvent, and an extraction time of 2 min for subsequent studies.

Furthermore, we utilized SHS to extract a series of target compounds with different molecular weights and different lipophilicity, including urea (MW 60.05, logP − 2.11), salicylic acid (MW 138.12, logP 2.26), glucose (MW 180.15, logP − 2.60), sodium fluorescein (MW 332.30, logP − 0.67), rhodamine B (MW 479.01, logP 1.95), FD 1 K (average MW 1000, logP − 7.72) and FD 2 K (average MW 2000, logP − 7.72). The results indicated that SHS can efficiently extract target compounds with a molecular weight of up to 1000 Da (Fig. 2). However, for drugs with a molecular weight exceeding 1 KDa, such as FD 2 K, no notable distinction was observed in comparison to the control group. The skin channel created by SHS could be insufficient to allow these large molecules to permit the passage of these large molecules into the extraction solvent within a short time frame. Simultaneously, we determined the content of target compounds in different skin layers (viable epidermis and dermis). Subsequently, we investigated the relationship between the detected concentration of target compounds and their levels in the skin. The results revealed a series of positive correlations between the concentration of target compounds extracted by SHS and their contents in the viable epidermis (Supplementary Fig. S2) and dermis (Supplementary Fig. S3). These findings suggested that the concentration obtained through percutaneous extraction using SHS can be used to determine and indicate the content of the target compound in different skin layers.

Percutaneous extraction using SHS in vivo

In the subsequent in vivo experiment, we utilized salicylic acid and glucose as hydrophilic model molecules, cyclosporin A as hydrophobic model molecules to further verify the relationship between the detected concentration of target compounds and their levels in the blood. Linear regression analysis showed a correlation between SHS-extracted concentrations of hydrophilic compounds and their blood levels (salicylic acid: R2 = 0.8503; glucose: R2 = 0.9081) (Fig. 3). This suggests that we can determine and indicate the content of the hydrophilic target compounds in the blood through percutaneous extraction using SHS.

The relationship between detected target compounds (salicylic acid and glucose) concentration with their level in blood. (a) The relationship between detected glucose concentration with its level in blood was fitted as a line (purple line), R2 = 0.9081. (b) The relationship between detected salicylic acid concentration with its level in blood was fitted as a line (blue line), R2 = 0.8503.

To further evaluate the effectiveness of SHS in monitoring the content of target compounds in the blood, we observed in vivo the changes in the concentration of salicylic acid in the blood and that extracted using SHS over 180 min after its intravenous injection. We noted a rapid rise in the concentration of salicylic acid in both the blood and the sample extracted by SHS to the peak value within half an hour, followed by a decline and stabilization at approximately 1.5 h (Fig. 4a). Simultaneously, we predicted the change in salicylic acid concentration in blood through the actual measured concentration extracted by SHS, using the calculation formula obtained in Fig. 3b. No appreciable discrepancy was discerned between the actual measured and predicted blood salicylic acid concentration after injection. This suggests that the percutaneous extraction of the hydrophilic target compound using SHS can track rapid changes in its content in the blood.

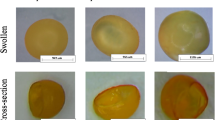

Kinetic study of target compound concentration over time in ISF and blood. (a) Kinetic study of salicylic acid concentration over time in ISF and blood. The real salicylic acid level in blood (red line) and detected salicylic concentration (dark line) from ISF using SHS both increased rapidly after injection and began to decrease half an hour later. They leveled off in an hour. These data showed similar kinetics with no time lag observed for the 30–min time resolution. The predicted salicylic acid level (blue line) in blood from the detected salicylic acid concentration using the formula in Fig. 3b was in good agreement with the real salicylic acid level in blood. After examination, there was no significant discrepancy between the predicted blood salicylic acid level and the measured blood salicylic acid level. **p < 0.01, ns p > 0.05. Mean ± SD of n = 3 independent samples. Two-tailed Student’s t-test. (b) Kinetic study of cyclosporin A concentration over time in ISF and blood. Mean ± SD of n = 3 independent samples. (c) Murine skin grafts with or without cyclosporin A treatment in vivo.

In the in vivo experiment for cyclosporin A, we monitored its concentration in both percutaneous extraction samples and blood at 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 days post-injection, over a 2-h period. Figure 4c shows the status changes of skin grafts in cyclosporine A-treated experimental groups and untreated control groups after murine skin transplantation. The untreated control group exhibited initial rejection signs at day 5 post-transplantation, progressing to complete ulceration by day 11. In contrast, cyclosporine A-treated mice exhibited no detectable rejection phenomena in skin grafts (Fig. 4c). However, our findings revealed no correlation between the cyclosporin A concentrations detected via SHS and the corresponding levels in the blood (Fig. 4b). The lack of correlation between cyclosporin A concentrations in extraction samples and blood in this study implies potential limitations for monitoring hydrophobic compounds via SHS, possibly due to its hydrophobic nature and complex distribution profile in the body.

Mathematical models of percutaneous extraction using SHS

Previous studies Sloan43 have shown that skin penetration models with an intact stratum corneum follow Fick’s first law,

In this context, \({\text{k}}_{{\text{p}}}\) represents skin permeability, while \({\text{a}}\), \({\text{b}}\) and \({\text{c}}\) are constants. \({\text{P}}\) signifies the oil–water partition coefficient for the target compounds, and \({\text{MW}}\) denotes the molecular weight of the target compounds.

Rzhevskiy et al.44 proposed a drug permeation model for microporous skin,

where \({\text{k}}_{{\text{p}}}\) is the skin permeability, \({\text{r}}_{{\text{p}}}\) represents the pore radius, \({\text{n}}_{{\text{p}}}\) signifies the pore density, and \({\text{ MW}}\) stands for the molecular weight of the target compounds.

Similarly, we derived a mathematical model for percutaneous extraction of target compound using SHS.

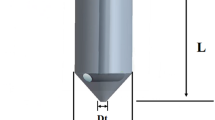

Since microneedles are removed after application, the drug penetration channels in the ‘perforated’ skin, formed by the microneedles, resemble hollow ‘funnels’ with two bases, which lengths are \(2r_{p}\) and \({ }\frac{{\pi \left( {l_{p} - 2r_{p} } \right)}}{8},\) respectively. In contrast, SHS, which remains on the skin after application, results in the formation of annular channels. SHS forms a solid part with a radius \(r_{s}\) equal to the SHS radius at the center of the skin channel, as illustrated in Fig. 5. Drawing on the analogy of the formation of a ‘funnel’ in ‘perforated’ skin, it is reasonable to assume that SHS puncturing into the skin would create a similar but impermeable small ‘funnel’ at the center (depicted in gray in Fig. 5b) with two bases \({ }2r_{s}\) and \(\frac{{r_{s} }}{{r_{p} }} \cdot \pi \left( {l_{p} - 2r_{1} } \right)/8,\) respectively.

Similarly, SHS form annular channel skin models in diffusion resistance

where \(K\left( x \right)\) and \(D\left( x \right)\) describe the distribution and diffusion of solute in different phase, in solvent \(K\left( x \right) = 1\), \(D\left( x \right) = D_{v}\), in the skin \(K\left( x \right) = K_{s}\), \(D\left( x \right) = D_{s}\). Assumptions on the cuticle of the hole is filled with solvent, the distribution and the diffusion coefficient of the solute in the hole is identical to that of the solvent, \(K\left( x \right) = 1\), \(D\left( x \right) = D_{v}\).

\(a\left( x \right)\) is the function of diffusion area in x direction. When \(0 \le {\text{x}} \le h_{SC}\), \(a\left( x \right) = n_{p} \pi \left( {r_{p}^{2} - r_{s}^{2} } \right)\). In the “funnel”, \(a\left( x \right) = \left( {1 - \frac{{r_{s}^{2} }}{{r_{p}^{2} }}} \right) \cdot n_{p} \pi r_{f}^{2} \left( x \right)\). The \(r_{f}\) of both skin sides respectively represents as \({ }r_{f} \left( x \right) = r_{p} + 4\left( {x - h_{SC} } \right)/\pi\) and \(r_{f} \left( x \right) = r_{p} - 4x/\pi\).

The \(\left( x \right)\), \(D\left( x \right){\text{ and }}a\left( x \right)\) function can be expressed as:

By integrating the piecewise function, we can obtain:

Because the channels formed by SHS are nanoscale, the pore radius should be smaller than the gap between the pores.

According to the published research45, the permeability coefficient of the annular channel formed by hSHS should approximately be:

The skin treated with SHS exhibits both annular channels and an intact stratum corneum. Therefore, we believe its drug permeability coefficient should be the sum of the contributions from the intact stratum corneum,\(k_{p,\;complete\;SC} ,\) and the annular channel, \(k_{p,\;annular\;channel}\).

Considering that the dose of SHS used is consistent, we fit the skin permeability, oil–water partition coefficient and molecular weight data for the six target compounds mentioned above, and obtain:

Discussion

The sponge Haliclona sp. spicules (SHS) have been utilized as an innovative discrete silica microneedle for delivering various therapeutics and drug nano-carriers40,42,46. The penetration depth of SHS into the dermis is approximately 30–40 μm, with a random insertion angle41. Consequently, SHS can reside in the epidermal layer over approximately 48 h without causing damage to the blood vessels in the dermis. Skin safety profiles of sponge Haliclona sp. spicules (SHS) have been systematically evaluated in our prior study,SHS demonstrates excellent skin safety in Draize testing with higher doses (5–10 mg/cm2) showing only mild transient erythema (P.I.I. 1.51–1.61 resolving in 72 h) and lower doses (1–2 mg/cm2) being nonirritating (P.I.I. 0.29–0.38) with mere slight desquamation in prolonged use40,47,48. Further, SHS can create plenty of microchannels within epidermis (around 103 channels per mm2 when topically applied at a dosage of 0.05 mg/mm2) to dramatically increase the permeability of skin. Therefore, in comparison to Dermaroller, ultrasound, and reverse iontophoresis, SHS demonstrates a more effective percutaneous extraction of target compounds. This includes both endogenous molecules and therapeutics, making it a potential tool for disease diagnosis and therapeutic drug monitoring.

After confirming the applicability of SHS in the percutaneous extraction field, Rhodamine B (MW = 479.01, logP = 1.95) was selected as another model drug to investigate potential factors influencing the percutaneous extraction efficiency of SHS: SHS dosage, extraction solvent, and extraction time. Rhodamine B, being more lipophilic than sodium fluorescein, was chosen to demonstrate the efficacy and feasibility of SHS percutaneous extraction for lipophilic target compounds. A higher dosage of SHS led to the formation of more microchannels on the stratum corneum, resulting in increased skin permeability. This positive correlation between SHS dosage and percutaneous extraction efficiency can be attributed to the greater number of microchannels formed with a higher SHS dosage. SHS creates numerous microchannels in the skin, and with the application of the extraction solvent to the outer side of the skin, a concentration gradient is established. Target compounds within the skin move along this gradient. With an increase in percutaneous extraction time, more target compounds move to the outer side of the skin and are absorbed by the extraction solvent. This explains the positive correlation between percutaneous extraction time and SHS percutaneous extraction efficiency. However, the distribution of Rhodamine B content at different extraction times suggests that the increase in content becomes more gradual with longer extraction times. Interestingly, the percutaneous extraction efficiency of SHS decreased with an increase in the addition of Tween 80 to the extraction solvent. While Tween 80 was expected to enhance the solubility of Rhodamine B in physiological saline, experimental results showed a negative correlation between the efficiency of SHS percutaneous extraction and the addition of Tween 80. One possible reason is that Tween 80, as a surfactant, might increase the deposition of lipophilic molecules in the stratum corneum, thereby reducing their content in the extraction solvent. In short, considering patient compliance and practical convenience, the aim was to obtain as much detectable target compound as possible in the shortest percutaneous extraction time. Therefore, the adopted percutaneous extraction scheme included a SHS dosage of 10 mg/177 mm2, extraction solvent of physiological saline, and an extraction time of 2 min.

Next, we utilized SHS for the percutaneous extraction of various target compounds, each with different molecular weights and varying degrees of lipophilicity. We examined the association between the identified concentration of these target compounds and their respective levels within different skin layers. Our analysis yielded a series of linear fitting results, as illustrated in Supplementary Figs. S2–S3, affirming that the concentration data acquired through SHS can be correlated with the content of these compounds in the skin. These findings underscore the viability of employing SHS for the percutaneous extraction of target compounds for potential applications in disease diagnosis and therapeutic drug monitoring.

Salicylic acid, characterized by a narrow therapeutic window and dose-dependent toxicity, is a medication frequently implicated in aspirin overdose49. The identification of overdoses involving therapeutic salicylic acid is often subject to delays, and the prognosis for salicylic acid poisoning remains bleak, particularly in vulnerable populations such as children and the elderly. Diabetes is a prevalent condition marked by diminished insulin sensitivity and the degeneration of pancreatic islet cells50. Maintaining precise blood sugar equilibrium is crucial, as elevated blood sugar levels may lead to a spectrum of ailments, while critically low blood sugar levels pose an immediate threat to life. Consequently, we selected salicylic acid, as a representative therapeutic agent, and glucose, as an endogenous molecule, to assess the feasibility of percutaneous extraction for monitoring their concentrations in the blood. The results (Fig. 4a) revealed a positive correlation between the concentration of target compounds in the extraction solution and their corresponding content in the blood. These linear fitting outcomes strongly indicate the ability to calculate the content of target compounds in the blood based on the detected concentration of these compounds through SHS. Consequently, in the application of SHS for percutaneous extraction of target compounds in disease diagnosis and therapeutic drug monitoring, the concentration information acquired through non-invasive sampling can be effectively associated with the actual content of these compounds in the patient’s blood. This approach facilitates the prediction of the patient’s health status and the effectiveness of drug treatments.

Moreover, leveraging the linear formula derived from the correlation between the SHS-detected quantity of salicylic acid and its blood content, we anticipated the trend of changes in blood salicylic acid content inferred from the SHS-detected amount. The predicted outcomes aligned with the observed trend of salicylic acid level changes. We observed no statistically significant discrepancy between the anticipated content of salicylic acid content in the blood and the experimentally measured content. These findings affirm that the quantification of hydrophilic target compounds by SHS, as a percutaneous extraction method, promptly reflects the actual content of these compounds in both interstitial fluid and blood. But for the lipophilic target compounds, the result is not ideal.

Numerous mathematical models have been developed to elucidate the impact of the physicochemical attributes of compounds on their penetration behaviors in the skin, including the penetration model depicting the transit of the compound through the complete skin layer43,51 and the drug penetration model specific to microporous skin44. We noticed that the size of the skin channels induced by SHS is in the nano-scale range40, we inferred that skin treated by SHS exhibits characteristics falling between intact skin and microporous skin. By integrating the mathematical models of the two extremes, we deduce that the impact of the physicochemical attributes of target compounds on their skin penetration behaviors:

Hence, for specific target compounds, the anticipation of their extraction efficiency through SHS can be informed by parameters such as their molecular weight and oil–water partition coefficient, though its generalizability requires verification with broader datasets. Given that the skin channel created by SHS is inherently hydrophilic, the extraction efficiency is expected to progressively diminish with an increase in both the oil/water coefficient and the molecular weight of the target compounds. We acknowledge the R2 value of 0.7820 reflects about 22% unexplained variation in our percutaneous model, attributable to unaccounted biological complexities including skin heterogeneity (stratum corneum thickness/lipid variations), dynamic physiological factors (blood flow/immune responses), and compound-specific behaviors (protein binding/non-linear diffusion). These limitations are being addressed through model refinement incorporating key biological variables.

Conclusion

This study illustrates the utilization of SHS in percutaneous extraction of diverse target compounds(fluorescein sodium, rhodamine B, salicylic acid, FD 1 k, urea, glucose) with distinct physicochemical properties. Robust linear correlations were observed between the detected concentration of target compounds through SHS and their levels in various skin layers, as well as in the blood. These findings substantiate the efficacy and feasibility of SHS for percutaneous extraction, indicating its potential in disease diagnosis and therapeutic drug monitoring. Additionally, mathematical models for percutaneous extraction via SHS were established by fitting the permeability coefficient of target compounds with their molecular weights (MW) and oil–water partition coefficients (logP): log kp = 2.9711 + 0.00235MV − 0.059526 log P + 6.7506 log MW−0.6. The topical application of SHS not only serves as a novel platform for skin drug delivery but also introduces a non-invasive, convenient, and efficient sampling strategy that could significantly improve patient compliance and clinical monitoring precision.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

References

Wang, L., Xiong, Q., Xiao, F. & Duan, H. 2D nanomaterials based electrochemical biosensors for cancer diagnosis. Biosens Bioelectron 89, 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2016.06.011 (2017).

Larheim, T. A., Hol, C., Ottersen, M. K., Mork-Knutsen, B. B. & Arvidsson, L. Z. The role of imaging in the diagnosis of temporomandibular joint pathology. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. North Am. 30, 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coms.2018.04.001 (2018).

Rayappan, J. B. B. & Lee, J. H. Biomarkers and biosensors for cervical cancer diagnosis. (2021).

Wasilewski, T. et al. Olfactory receptor-based biosensors as potential future tools in medical diagnosis. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 150, 116599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2022.116599 (2022).

Ching, C. T., Chou, T. R., Sun, T. P., Huang, S. Y. & Shieh, H. L. Simultaneous, noninvasive, and transdermal extraction of urea and homocysteine by reverse iontophoresis. Int. J. Nanomed. 6, 417–423. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S16418 (2011).

Wascotte, V. et al. Non-invasive diagnosis and monitoring of chronic kidney disease by reverse iontophoresis of urea in vivo. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 69, 1077–1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.02.012 (2008).

Ma, J. H. et al. Spectral entropy monitoring reduces anesthetic dosage for patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 26, 818–821. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2012.01.028 (2012).

Akbar, M. & Agah, M. A microfabricated propofol trap for breath-based anesthesia depth monitoring. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 22, 443–451. https://doi.org/10.1109/jmems.2012.2227949 (2013).

Nunes, R. R. et al. Brazilian consensus on anesthetic depth monitoring. Rev. Bras. Anestesiol. 65, 427–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjan.2015.10.001 (2015).

Rawson, T. M. et al. Microneedle biosensors for real-time, minimally invasive drug monitoring of phenoxymethylpenicillin: A first-in-human evaluation in healthy volunteers. Lancet Digit. Health 1, E335–E343. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2589-7500(19)30131-1 (2019).

Eliasson, E., Lindh, J. D., Malmström, R. E., Beck, O. & Dahl, M. L. Therapeutic drug monitoring for tomorrow. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 69(Suppl 1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-013-1504-x (2013).

Clarke, W. in Clinical challenges in therapeutic drug monitoring (eds William Clarke & Amitava Dasgupta) 1–15 (Elsevier, 2016).

Ates, H. C. et al. On-site therapeutic drug monitoring. Trends Biotechnol. 38, 1262–1277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.03.001 (2020).

Baroli, B. Penetration of nanoplarticles and nanomaterials in the skin: Fiction or reality?. J. Pharm. Sci. 99, 21–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.21817 (2010).

Wong, R., Geyer, S., Weninger, W., Guimberteau, J. C. & Wong, J. K. The dynamic anatomy and patterning of skin. Exp. Dermatol. 25, 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/exd.12832 (2016).

Haque, T. & Talukder, M. M. U. Chemical enhancer: A simplistic way to modulate barrier function of the stratum corneum. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 8, 169–179. https://doi.org/10.15171/apb.2018.021 (2018).

Xue, P. et al. Blood sampling using microneedles as a minimally invasive platform for biomedical diagnostics. Appl. Mater. Today 13, 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmt.2018.08.013 (2018).

Liu, G. S. et al. Microneedles for transdermal diagnostics: Recent advances and new horizons. Biomaterials 232, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119740 (2020).

Sagoe-Moses, C., Pearson, R. D., Perry, J. & Jagger, J. Risks to health care workers in developing countries. N Engl J Med. 345, 538–541. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm200108163450711 (2001).

Miller, M. A. & Pisani, E. The cost of unsafe injections. Bull. World Health Organ. 77, 808–811 (1999).

Ita, K. Transdermal delivery of drugs with microneedles: Strategies and outcomes. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 29, 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2015.05.001 (2015).

Larrañeta, E., Lutton, R. E. M., Woolfson, A. D. & Donnelly, R. F. Microneedle arrays as transdermal and intradermal drug delivery systems: Materials science, manufacture and commercial development. Mater. Sci. Eng. R-Rep. 104, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mser.2016.03.001 (2016).

Narayanan, S. P. & Raghavan, S. Solid silicon microneedles for drug delivery applications. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. (2016).

Sonetha, V., Majumdar, S. & Shah, S. Step-wise micro-fabrication techniques of microneedle arrays with applications in transdermal drug delivery-A review. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 68, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2022.103119 (2022).

Chua, B., Desai, S. P., Tierney, M. J., Tamada, J. A. & Jina, A. N. Effect of microneedles shape on skin penetration and minimally invasive continuous glucose monitoring in vivo. Sens. Actuators, A 203, 373–381 (2013).

Tachibana, K. et al. Enhanced cytotoxic effect of Ara-C by low intensity ultrasound to HL-60 cells. Cancer Lett. 149, 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00358-4 (2000).

Carmen, J. C. et al. Ultrasonic-enhanced gentamicin transport through colony biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Chemother. 10, 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10156-004-0319-1 (2004).

van Wamel, A., Bouakaz, A., Bernard, B., ten Cate, F. & de Jong, N. Radionuclide tumour therapy with ultrasound contrast microbubbles. Ultrasonics 42, 903–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultras.2003.11.013 (2004).

Yusof, N. S. M., Anandan, S., Sivashanmugam, P., Flores, E. M. M. & Ashokkumar, M. A correlation between cavitation bubble temperature, sonoluminescence and interfacial chemistry—A minireview. Ultrason. Sonochem. 85, 105988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.105988 (2022).

Nightingale, K. R., Kornguth, P. J. & Trahey, G. E. The use of acoustic streaming in breast lesion diagnosis: a clinical study. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 25, 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-5629(98)00152-5 (1999).

Shi, X., Martin, R. W., Vaezy, S., Kaczkowski, P. & Crum, L. A. Color Doppler detection of acoustic streaming in a hematoma model. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 27, 1255–1264. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-5629(01)00428-8 (2001).

Sieg, A., Guy, R. H. & Delgado-Charro, M. B. A. Reverse iontophoresis for noninvasive glucose monitoring: The internal standard concept. J. Pharm. Sci. 92, 2295–2302. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.10492 (2003).

Degim, I. T., Ilbasmis, S., Dundaroz, R. & Oguz, Y. Reverse iontophoresis: a non-invasive technique for measuring blood urea level. Pediatr. Nephrol. 18, 1032–1037. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-003-1217-y (2003).

Sieg, A. et al. Extraction of amino acids by reverse iontophoresis in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmaceut. Biopharmaceut.: Off. J. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Pharmazeut. Verfahrenstechnik e.V 72, 226–231 (2009).

Leboulanger, B., Guy, R. H. & Delgado-Charro, M. B. Non-invasive monitoring of phenytoin by reverse iontophoresis. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 22, 427–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2004.04.010 (2004).

Delgado-Charro, M. B. & Guy, R. H. Transdermal reverse iontophoresis of valproate: A noninvasive method for therapeutic drug monitoring. Pharm. Res. 20, 1508–1513. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025730815971 (2003).

Burnette, R. R. & Ongpipattanakul, B. Characterization of the permselective properties of excised human skin during iontophoresis. J. Pharm. Sci. 76, 765–773. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.2600761003 (1987).

Pikal, M. J. Transport mechanisms in iontophoresis. I. A theoretical model for the effect of electroosmotic flow on flux enhancement in transdermal iontophoresis. Pharmaceut. Res. 7, 118–126 (1990).

Kasting, G. B. & Keister, J. C. Application of electrodiffusion theory for a homogeneous membrane to iontophoretic transport through skin. J. Control. Release 8, 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-3659(89)90042-4 (1989).

Zhang, C. et al. Skin delivery of hyaluronic acid by the combined use of sponge spicules and flexible liposomes. Biomater. Sci. 7, 1299–1310. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8bm01555d (2019).

Zhang, S. M. et al. Skin delivery of hydrophilic biomacromolecules using marine sponge spicules. Mol. Pharm. 14, 3188–3200. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00468 (2017).

Liang, X. J. et al. Skin delivery of siRNA using sponge spicules in combination with cationic flexible liposomes. Mol. Therapy-Nucl. Acids 20, 639–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2020.04.003 (2020).

Sloan, K. B. Prodrugs: Topical and Ocular Drug Delivery. (Prodrugs : topical and ocular drug delivery, 1992).

Rzhevskiy, A. S., Guy, R. H. & Anissimov, Y. G. Modelling drug flux through microporated skin. J. Control. Release 241, 194–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.09.029 (2016).

Scheuplein, R. J. & Blank, I. H. Mechanism of percutaneous absorption. IV. Penetration of nonelectrolytes (alcohols) from aqueous solutions and from pure liquids. J. investing. Dermatol. 605, 286–296 (1973).

Lin, X. K., Wang, Z. H., Ou, H. L., Mitragotri, S. & Chen, M. Correlations Between skin barrier integrity and delivery of hydrophilic molecules in the presence of penetration enhancers. Pharmaceut. Res. 37, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-020-02800-4 (2020).

Zhai, H., Zhang, C., Ou, H. & Chen, M. Transdermal delivery of heparin using low-frequency sonophoresis in combination with sponge spicules for venous thrombosis treatment. Biomater. Sci. 9, 5612–5625. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1BM00703C (2021).

Jin, Y., Zhang, C., Jia, M. & Chen, M. Enhanced dermal delivery of nanoparticulate formulation of cutibacterium acnes using sponge spicules for atopic dermatitis treatment. Int. J. Nanomed. 20, 3235–3249. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.S509798 (2025).

Levy, G. Clinical pharmacokinetics of aspirin. Pediatrics 62, 867–872. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.62.5S.867 (1978).

Roden, M. & Shulman, G. I. The integrative biology of type 2 diabetes. Nature 576, 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1797-8 (2019).

Potts, R. O. & Guy, R. H. PREDICTING SKIN PERMEABILITY. Pharm. Res. 9, 663–669. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015810312465 (1992).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant (2022J01025) from the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province of China, a grant(FJHJFL-2023-32) from the Fujian Ocean and Fisheries Department, a grant (21CZP002HJ05) from Xiamen Marine and Fisheries Development Fund, a grant (S202410384619) from the College Students’ Innovative Entrepreneurial Training Plan Program and a grant (2023XAKJ0101003) from the Scientific Research Foundation of State Key Laboratory of Vaccines for Infectious Diseases, Xiang An Biomedicine Laboratory.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L., S.Z., M.J., S.C., R.Z. and Y.L. performed the experiments. M.C. and G.Y. designed the experiments. S.L. and M.C. were involved in the analyses and interpretation of data. All authors wrote the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethicl approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Xiamen University (2024.09.29/ XMULAC20240217).

Trial registration

Prof. Dr. Ming Chen reports a patent CN202210295831.0 pending.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Zhang, S., Jia, M. et al. Percutaneous extraction using sponge spicules for disease diagnosis and therapeutic drug monitoring. Sci Rep 15, 45470 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29102-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29102-2