Abstract

Chickenpox is a highly contagious viral infection caused by varicella-zoster virus (VZV) whose clinical manifestations mimic mpox posing challenges for diagnosis without laboratory confirmation. Here, we investigated VZV among the mpox-suspected cases, May to October 2022, in Ethiopia. Samples were collected from 202 mpox-suspected cases in 11 of Ethiopia’s 14 regions and screened for mpox virus by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Then, differential testing of other selected orthopoxviruses, VZV and herpes simplex virus (HSV) were conducted for 133 randomly selected samples. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and downstream analysis was performed on 8 VZV-positive samples. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize epidemiological and clinical data. All the 202 enrolled cases tested negative for mpox. Of these, 133 samples were tested for VZV, and 107 (80.5%, 95% CI: 72.9% – 86.3%) turned positive but remained negative for HSV and other tested orthopoxviruses. At least one VZV-positive case was reported in each region sampled. Half (49.6%) of the cases were hospitalized, with no fatalities. The sequences were clustered primarily in Clade 5 (62.5%, 5) followed by Clade 3 (25.0%, 2) and Clade 1 (12.5%, 1). This investigation confirmed VZV as the predominant causative agent among mpox-suspected cases. To our knowledge, this represents the first clade-level genomic characterization of VZV from Ethiopia, revealing circulation of multiple clades among samples collected during May to October 2022. The findings highlight the need to strengthen differential diagnostic capacities including multiplex testing, and building genomic surveillance capacities for epidemic intelligence and outbreak response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mpox (formerly known as monkeypox) is a zoonotic disease caused by the monkeypox virus (MPXV), which is a member of the Orthopoxvirus genus within the Poxviridae family. The first human case of mpox was reported in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in 1970, and since then, the disease has caused sporadic cases and outbreaks, predominantly in West and Central Africa1. In recent years, however, mpox has spread to non-endemic countries within Africa and worldwide. In July 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared mpox as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). Between 1 January 2022 and 31 May 2025, WHO reported 148 892 laboratory-confirmed cases of mpox and 341 deaths across 137 countries2. Mpox was again declared as a PHEIC from 14 August 2024 due to an upsurge of cases in endemic countries and expanding number of affected countries globally until lifted on 05 September 20253. and currently remains a public health concern in Africa4.

Mpox, chickenpox, measles, herpes simplex virus (HSV), scabies, hand, foot and mouth (HFM) disease, and other rash-related conditions can produce similar clinical manifestations. Some peculiar characteristics can, however, help to distinguish one from the other. Clinically, mpox rashes are deep-seated, same-stage lesions that typically emerge on the face, eyes, inside the mouth, on the hands, feet, chest, and genitals and/or anus5. In contrast, chickenpox generally produces a rash that does not affect the palms and soles or the perineal area, with different stages of lesions occurring simultaneously6.

Furthermore, Koplik spots and maculopapular, confluent rash-which usually begins on the face and spreads downward, accompanied by high-grade fever7 and the characteristic of “3Cs” (coryza, cough, and conjunctivitis) are features observed during measles infection8. Symmetrical rashes involving the hands, feet, buttocks, and mouth in HFM disease7, and painful, localized rashes mainly affecting the mouth and genital area with characteristic grouped and recurrent lesions, together with fever and lymphadenopathy in HSV infections9, are important clinical characteristics.

Given the overlapping clinical features, diagnosing these rash-associated diseases based on clinical presentations alone is inadequate and unreliable, highlighting the need for diagnostic testing support1,10,11. At the start of the mpox epidemic in Brazil, it was challenging to clinically differentiate between atypical rashes associated with mpox and those related to varicella-zoster virus (VZV), which was co-circulating10. Such incidents can pose significant challenges for disease diagnosis and management at both clinical and public health levels unless supported with differential diagnostic capacities7,10,11,12.

While much attention has focused on mpox, limited data exist on the contribution of other rash-associated viruses, specifically varicella-zoster virus VZV (the causative agent of chickenpox), to case burden in Africa. Misidentification risks can delay response, distort outbreak metrics, and lead to inappropriate case management, and inefficient allocation of limited public health resources13,14.

Chickenpox is a highly contagious viral infection15. Globally, an estimated 140 million varicella cases occur annually, with most individuals acquiring the infection at some point in their lives16. In countries where the varicella vaccine has been incorporated into routine immunization programs, primarily in developed nations, the burden of the disease has significantly decreased17,18. In 1998, WHO recommended introducing routine childhood vaccination against chickenpox in countries where the disease has significant socioeconomic impacts. Despite the recommendations, the vaccination has not been implemented in most African countries, including Ethiopia19,20,21. This creates an epidemiological blind spot for both endemic and imported VZV strains. Although its benign characteristics, VZV can cause complications and deaths, particularly in high-risk populations22. In Africa, factors such as an aging population (increasing the risk of VZV reactivation) and high prevalence of human immune deficiency virus (HIV) further increase disease severity17,21.

VZV was reported in rash associated outbreaks or as part of regular monitoring in some regions globally. Moreover, since recently, it was profoundly reported during mpox multi-country outbreak confirmation and response in 2022 and afterwards. As such, VZV was reported in DRC, Nigeria, Kenya, Pakistan and Brazil with rates ranging from 22.2% to 80.4%23,24,25,26,27 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests in which the positivity rate differences could be attributed to different host, viral related and other factors including variations in case definitions, specimens types, diagnostic methods, and whether sampling occurred during outbreak or routine surveillance periods22,28.

Emerging genomic data from the globe reveal that there are eight distinct clades of VZV, Clades 1–6, clades 8 and 9 which are characterized by distinct geographic and evolutionary patterns29, with implications for pathogenicity and vaccine escape22. Reports in Kenya, Guinea-Bissau, DRC and India revealed predominance of Clade 518,26,30,31. Clade 4 was also known to circulate in Africa in addition to clade 5, while Clades 1, 3 and 5 in Europe32, clade 2 in China and other areas in Asia33. Additionally, clade 9 was reported for the first time in India in addition to the previously circulating clades of 1,4 and 530,34. Identifying and characterizing the VZV genome is important to have an epidemiological insight, reveal the genetic diversity, and evolutionary patterns33.

There are limited data on epidemiological and genomic diversity of VZV in Africa20, and this gap is particularly more pronounced in resource-constrained settings such as Ethiopia, where the circulation and clade distribution has not been previously explored. There has not been epidemiological data reports of VZV in Ethiopia, except the 2018 clinically suspected VZV outbreak reported in 201819. Moreover, VZV is not included under the national notifiable diseases list and no vaccination program against it has been implemented, contributing to the scarcity of epidemiological data. All these limits understanding of the epidemiology of chickenpox, VZV viral diversity, and its transmission dynamics in the country. Addressing these knowledge gaps is therefore important for accurate differential diagnosis among clinically similar pathogens and supports to guide appropriate case managements and public health interventions. The study finding can provide critical baseline data on clade distribution and transmission dynamics in Ethiopia. Thus, this study aimed to characterize the molecular epidemiology of VZV detected among mpox-suspected cases in Ethiopia in 2022 and assess the circulating VZV clades using whole-genome sequencing.

Methods and materials

Setting and context

Ethiopia, with an estimated population of 126.5 million as of 2023, is the second most populous country in Africa, after Nigeria35. The country is administratively divided into 12 regional states and two city administrations36 and shares borders with 6 African countries namely Djibouti, Eritrea, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan. The capital, Addis Ababa, serves as the headquarters of the African Union and hosts many international events and tourist visits37. The country, as outlined in the recent guideline, has list of immediately and weekly reportable diseases under surveillance including Mpox38. Mpox suspect case identification and screening was carried out in previous years since 2022 as part of national preparedness efforts during the PHEIC period; however, no confirmed case was confirmed among those initially screened ones until recently. Ethiopia reported its first mpox case (mpox Clade Ib)39 and death on 25 of May 2025 and 31 of May 2025, respectively; after three years of preparedness and monitoring activities.

This study was based on data and samples collected from suspected mpox cases across Ethiopian regions and city administrations. The Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) is the national authority mandated to conduct public health emergency management activities, including preparedness for emerging public health threats, disease and health events surveillance, and outbreak response and recovery among others38. Hence, this mpox preparedness activity and laboratory investigation was conducted under EPHI’s mandate of public health emergency management systems. The investigations were carried out in accordance with approved national, and international guidelines40,41.

Case definition41

The 2022 WHO mpox case definition was used to enroll cases included in this study. A suspected mpox case was defined as any person, regardless of age, in an mpox non-endemic country presenting with an unexplained acute rash and one or more of the following signs or symptoms, since 15 March 2022: headache, acute onset of fever (> 38.5 °C), lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes), myalgia (muscle pain/body aches), back pain, asthenia (profound weakness), and for which the following common causes of acute rash do not explain the clinical picture: varicella zoster, herpes zoster, measles, herpes simplex, bacterial skin infections, disseminated gonococcus infection, primary or secondary syphilis, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, granuloma inguinale, molluscum contagiosum, allergic reaction (e.g., to plants); and any other locally relevant common causes of papular or vesicular rash.

Data collection and selection procedure for VZV testing and sequencing

Data was collected from suspected mpox cases as part of the national mpox preparedness efforts and from investigation of skin lesion reports from different parts of the country. Skin lesion or crust, respiratory swabs and serum were collected from cases who met the mpox case definition by trained personnel in accordance with standard operating procedure (SOP). Actual testing was conducted from the skin lesion/crust samples, and the remaining were kept for back up testing. Upon collection, the samples were transported to EPHI by trained health care workers adhering to recommended sample transportation temperature conditions (2–8 °C). Epidemiological and clinical data were submitted to EPHI along with samples. Data collection were carried out upon informed consent was obtained from all enrolled mpox suspected cases or their legal guardians.

All mpox-suspected samples collected during the study period were first screened based on completeness of epidemiological and clinical data. Due to logistic and reagent constraints, only subsets of the collected samples were selected and tested for VZV. Of the total 202 suspected mpox cases, 133 samples (65.8%) were selected for VZV PCR testing through systematic random sampling, as they appeared sequentially in the data registration sheet on a monthly basis. The selection prioritized specimen quality, availability of case information, and temporal representation across outbreak months. From these, 15 PCR-confirmed VZV-positive samples were further selected for sequencing based on Ct value thresholds, regional representation, and sample integrity to capture both genetic and geographic diversity while minimizing selection bias. In addition, a total of 40 samples, including 15 VZV-positive and 25 VZV-negative specimens, all negative for mpox were purposively selected considering VZV test status, timing of sample collection, regional distribution, and sample adequacy. These were shipped to the Institut National de Recherche Biomédicale (INRB), DRC, for confirmatory testing of both VZV and mpox, after which sequencing was conducted on all 15 VZV-positive samples. Prior to shipment, 25 mpox-negative samples were also sent to the NICD for mpox re-testing, where all results were confirmed negative.

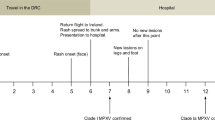

DNA extraction and laboratory testing

Viral deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted from clinical samples using the Qiagen DNA Purification Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA was screened for mpox and other orthopoxviruses, VZV, and HSV using real-time PCR assays. Then the subset of randomly selected mpox-negative samples, which accounts for reagent shortage, underwent differential testing targeting other orthopoxviruses: smallpox, cowpox, camelpox, racoonpox, and vaccinia viruses using Multiplex Altona Realstar Orthopox PCR kits (Cat no: 361003) while testing for herpes simplex virus (HSV) and VZV was conducted using monoplex Altona PCR kits (cat: 061013 and 081013) (Fig. 1). The VZV PCR run was conducted by adjusting the program; one stage of initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min followed by amplification at 95 °C for 15 s and result acquisition at 58 °C for 1 min, both set for 45 cycle repeats42.

Results were qualitatively interpreted as positive or negative based on the presence or absence of PCR sigmoid amplification curves, a curve consisting of exponential, linear and plateau phases, at the end of the PCR run. The testing and result interpretation process followed the manufacturer’s protocol and manual adjustments, and reviews of PCR-amplification curves were conducted to validate the presence or absence of real sigmoid amplification curves within the 45 cycles run. Per the manufacturer’s claim, this kit has a high diagnostic performance (can detect 0.1 DNA copies of VZV/µl) and with no report of cross-reactivity reports against other viruses including herpesviruses (HSV-1, HSV-2), cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus42. Both negative and positive controls were included in each batch of the tests in addition to the internal controls provided with the kit to properly control each step of the PCR run, including the DNA extraction, master mix preparation and run program and efficiency of the thermocycler. All the leftover negative and positive samples are archived at the EPHI for any potential molecular and epidemiological studies.

VZV DNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

All 15 positive samples that remained concordant (positive at both EPHI initial testing and INRB re-testing) were subjected to whole-genome sequencing (WGS) using the Illumina MiSeq platform with 2 × 150 bp paired-end chemistry. Libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit, following the manufacturer’s recommended protocols. Quality filtering and adapter trimming were completed prior to downstream analysis.

Sequence reads were aligned to the reference genome Human alphaherpesvirus 3 (GenBank accession NC_001348.1, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/9625875) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) with default parameters. Quality metrics including mapped read percentage, coverage depth, duplicate read rate, and coverage breadth were computed for each sample.

Bioinformatics analysis was conducted using the GeVarLi pipeline (GEnome assembly, VARiants calling, and Lineages assignment; version 1.2.0, https://forge.ird.fr/transvihmi/nfernandez/GeVarLi.git) to enable consensus sequence generation, variant calling, and assessment of sequence quality metrics. Sequence reads were aligned to the human alphaherpesvirus 3 (VZV) reference genome (GenBank accession NC_001348.1, accessible via NCBI: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/9625875) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) with standard parameters.

Only samples achieving greater than 70% genome coverage were selected for downstream analysis and clade assignment, consistent with VZV genomic sequencing standards. This threshold was applied to ensure reliable variant detection and confident phylogenetic placement43, as samples below this cutoff lack sufficient data in key genomic regions for robust analysis. For each sample, sequence quality metrics were calculated, including percentage of mapped reads, mean coverage depth, duplicate read rate, and genome coverage breadth.

Clade identification and phylogenetic analysis were performed using the VaricellaGen pipeline (https://github.com/MicroBioGenoHub/VaricellaGen), a modular and automated workflow for VZV genomic analysis44. Visualization of phylogenetic clustering and clade assignments was completed using the Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v7 platform.

Data analysis and quality assurance

Data was entered and analyzed using Microsoft Excel, Microsoft 365 v2507, to generate figures and descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages for continuous variables as means and medians. Additionally, 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value were presented for simple comparison among selected variable values;. Clustered bar charts were presented by running an R script in RStudio v2024.12.0.467 with R v4.4.2, using ggplot2 v3.5.2, dbplyr v2.5.0, and tidyr v1.3.1. Both meta and biodata quality were ensured through training provisions for data and sample collectors as well as laboratory experts who performed the laboratory tests. Portions of samples were also shipped to Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) and WHO-designated regional reference laboratories in the DRC and South Africa for confirmatory testing for mpox and VZV, as well as for VZV sequencing. In total, in two rounds of shipments, 15 VZV-positive and 25 negative specimens, all of which were mpox-negative, were shipped to DRC, while 25 mpox-negative specimens with VZV status not known at the time were shipped to NICD primarily for mpox re-testing. A concordant test result was received at both laboratories for both VZV and mpox, further ensuring the quality of reported test results. The sample collection, transportation, testing, and result interpretations were carried out with strict adherence to the SOPs and manufacturers’ instructions.

Results

Demographic characteristics of suspected Mpox cases and VZV test results

In the analysis of 202 samples for mpox, none were positive. Then, a subset of 133 cases from the 202 suspected mpox cases were randomly selected for other orthopoxvirus, VZV, and HSV testing with negative results except for VZV. Testing was not conducted for the remaining samples due to a shortage of testing reagents. Testing for VZV was conducted throughout the six months ranging from 5 in September 2022 to 41 in August 2022 (Figs. 1 and 2).

Key: * All test results were negative for the respective tested viruses, †mpox was part of the multiplex detection panel and the test results were again conclusively negative, same as the initial test results by the monoplex RT-PCR test.

Among the 133 cases, 62.4% were males and 37.6% were females. The overall age range was 1–76 years (median: 23.5 years); 60.2% of cases were from the 16–30 year-old age group. More than half of the suspected cases (63.9%) originated from three regions: 28.6% (38/133) from Addis Ababa, 19.5% (26/133) from Amhara, and 15.8% (21/133) from Oromia (Table 1).

The overall VZV positivity rate was 80.5% (95% CI: 72.9% – 86.3%) among the 133 mpox-suspected cases. The highest VZV positivity rate was observed in patients younger than 16 years (85.7%), followed by those older than 30 years (80.0%). The greatest number of VZV-positive cases was reported from Addis Ababa (28.6%), Amhara (19.5%), and Oromia (15.8%), the same regions that contributed the largest number of suspected cases. Patients having a travel history in the last 21 days before the onset of illness had a higher positivity rate (87.0%, 20/23) compared to those without recent travel. Moreover, VZV was detected during all months in the study period ranging from 58.3% in June to 97.2% in July (Table 1).

Clinical presentation and rash distribution reported among the VZ tested Mpox suspected cases

All suspected cases presented with a rash involving some or all parts of the body. More than half of the 133 enrolled cases reported fever (63.2%), headache (59.4%), itchy lesion (56.4%), muscle pain (51.1%), and fatigue (51.1%) (Fig. 3). Approximately 41.4% of the suspected cases had a rash or lesion covering the entire body, while 58.6% of them had a rash or lesion affecting at least one part of the body (Table 1).

In this study, we reported mainly a non-localized rash involving the face, limbs, trunk, palm, sole and genitals among the majority of the participants (Fig. 4).

Parts of the body involved in rash presentation among mpox-suspected cases in Ethiopia, May to October 2022 (n = 96). The percentages were calculated among 96 cases who had an explicit list of parts of the body affected with rash. *The localized rash was presented in one particular body part of the enrolled case: without further to other body parts (4 cases had rash on the face, one on limb and 1 on trunk).

VZV clade identification and metadata characteristics

A total of 15 randomly selected and shipped VZV-positive samples were processed for whole-genome sequencing (WGS). Of these, eight achieved ≥ 70% genome coverage and were included in downstream bioinformatics analysis. The 70% coverage cut-off value was applied to maximize the number of usable sequences while ensuring sufficient quality for variant detection and phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 1).

For the eight included samples, approximately 4.2 million raw paired reads were generated in total (mean: 529,246 per sample; range: 64,672–2,765,526). After quality filtering and adapter trimming, mapped read percentages were relatively high (mean: 57.4%, range: 36.6–70.5%), indicating efficient target enrichment. Mean sequencing depth ranged from 42× to 422× (mean: 418×), and duplicate read rates remained low (mean: 2.1%; range: 0–7%), indicating robust library complexity and minimal PCR bias. Complete sample-level sequencing quality metrics are available in Supplementary Table S1. Sequence mapping was performed against the VZV reference genome (Human alphaherpesvirus 3, GenBank accession NC_001348.1) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) with standard parameters.

Three VZV clades were observed among Ethiopian samples: Clade 5 (62.5%, n = 5), Clade 3 (25.0%, n = 2), and Clade 1 (12.5%, n = 1) (Table 2). Ethiopian sequences clustered phylogenetically with previously reported African and global VZV strains of Clades 5, 3, and 1, including reference sequences deposited in GISAID. No unique geographical clustering was revealed in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5), although sample size limits the power to detect recent introductions or clustering patterns.

The maximum likelihood method was utilized to generate the phylogenetic tree of the VZV genome of eight genomes (≥ 70% coverage) from Ethiopia. Each clade to which ours belongs is denoted by dark blue, orange and green for clades 1, 3 and 5 respectively. The red and green edited genome names are VZV genomes of Ethiopia generated from the current study.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study provides the first genomic evidence of VZV circulation among suspected mpox cases in Ethiopia during the 2022 global mpox outbreak. We report that among 133 suspected mpox cases, 80.5% (107) tested positive for VZV, with infections detected across all age groups and both genders and reported in multiple regions, including city administrations. The most common clinical presentations included fever, headache, itchy lesions, muscle pain, and fatigue. Although the number of genomic sequences was limited, we identified three distinct VZV clades, suggesting genetic diversity among the circulating strains in Ethiopia. This clade-level genomic characterization of VZV in Ethiopia, can bridge a significant data gap in the country and beyond in Eastern African region.

An overall VZV positivity rate of 80.5% among mpox-suspected participants demonstrates the high level of VZV circulation during the study period, aligning with previous clinical outbreak reports from Ethiopia. These findings highlights the need to strengthen surveillance, preventive interventions, and public health preparedness19. VZV is not currently included in Ethiopia’s national surveillance or immunization programs23, a significant gap given its potential for reactivation and associated morbidity21. Comparative analysis shows similarly high VZV positivity rates among mpox-negative cases in DRC (80.4%)28 and (59.6%)24, Nigeria (66.7%)25, Kenya (61.4%)26, and Pakistan (66.7%)23, while lower rates have been documented in other settings, including within Nigeria (17.1%) and Brazil (22.4%)27. Such differences could be attributed to several factors, including variations in case definitions, specimen types, diagnostic methods, and whether sampling occurred during outbreak or routine surveillance periods22,28.

In our study, fever, headache, itchy lesion, muscle pain, and fatigue were reported by more than 50% of the participants, consistent with a report from DRC45. Non-localized rashes were observed on the face, limbs, trunk, palm, sole, and genitals, with 41.4% of cases exhibiting rash across the entire body. Similar distributions of skin lesions have been reported in other studies among mpox and VZV cases25. The rash may initially present on the face, chest, and back and then spread to other parts of the body including the genitals46, as observed in our study. Identification of VZV based on clinical diagnosis alone is challenging, particularly in the presence of other rash-causing diseases such as mpox6, implying the need and importance of laboratory confirmation.

Our findings, derived from suspected mpox cases primarily sampled for mpox testing, highlight that the high VZV positivity rate observed in our study, as well as other countries6, underscores the need for building differential testing capacity for rash-associated diseases with overlapping clinical presentations, such as VZV and mpox. In line with this, the WHO, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Africa CDC, and other agencies recommend devising comprehensive testing algorithms for accurate etiologic identification, essential for timely and appropriate public health response and clinical management11,46,47,48. In multiple reports, VZV was detected more frequently than mpox among suspected mpox cases, further stressing the importance of incorporating differential diagnostic testing in dealing with mpox outbreaks or during surveillance6,23,25,27. Infection with VZV or mpox may also increase susceptibility to subsequent infections, though the mechanism remains unclear24. Reports speculate that the susceptibility could be attributed to impaired skin barrier and compromised immunity25.

While VZV is considered a children’s disease, it also affects all age groups22,25. In our study, a high positivity rate was detected across all ages, with a slight increase among children under 16. This slight increase may be due to immunity or primary infections of VZV49 in addition to close interaction among older children; close contacts during classes and play; and sharing of materials, which all could contribute to increased virus acquisition25. Reactivation of VZV, usually after the age of 50 years, may contribute to increased reports among the higher age groups in our report50. Similar patterns have been reported in other settings without a significant difference28.

Our study revealed that multiple clades of VZV were circulating in Ethiopia, with Clade 5 predominant, followed by Clade 3 and Clade 1. To our knowledge, this is the first clade-level characterization of VZV in the country. Predominance of Clade 5 has also been reported in Kenya26, DRC18, Guinea-Bissau31, and India30, although Clade 4 has been noted in Africa, and clades 1, 3, and 5 are predominantly European32. One sequenced specimen was collected from a traveler returning from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, consistent with a report of Clade 5 among travelers and non-travelers across multiple countries, including Ethiopia and Saudi Arabia, suggesting the widespread distribution of the clade across countries34. Phylogenetic analysis revealed Ethiopian sequences clustered with viruses from clade 5, 3, and 1 reported from GISAID and reports from other African countries, without unique country-specific clustering. However, the small number of VZV sequences in our study could lack power in revealing recent introductions. Understanding VZV clade distribution has crucial benefits to gain the view of genomic recombination among the different clades, reinfections, and reactivations due to the different clades51. Given the absence of previous VZV genomes reported in Ethiopia, this study helps bridge a critical regional genomic gap.

This study has certain limitations: The data and samples we analyzed and presented were primarily collected as a part of mpox preparedness and response, which could have a gap in fully capturing the clinical and epidemiological information related to chickenpox. All the collected samples from suspected mpox samples couldn’t be tested due to reagent and logistic constraints, which could limit presentation of data on the remaining samples. The samples were from a limited time frame; the situation might differ outside that outbreak context. Moreover, the small number of genomes sequenced limits the phylogenetic inferences and may not capture and reflect the full diversity of circulating VZV clades in Ethiopia.

Ethical statement

This study utilized data collected from the mpox outbreak preparedness, surveillance, outbreak investigation activities. Under the Federal Democratic Republic Ethiopia, Regulation No. 529/202352, the EPHI is mandated to conduct Public Health Emergency Management. Thus, the activity was deemed non-research and ethics approval was deemed not necessary. The work was also in accordance with the 2022 public health emergency management guideline of the institute40. Data and sample collections were conducted by trained professionals and was in accordance with ethical guidelines, including anonymization, ensuring confidentiality and obtaining verbal consent. No personnel identifier was used throughout the data analysis, manuscript write up and other stages of the process. Cases were treated and managed according to national case management protocols.

Conclusions

Our findings revealed a high prevalence of VZV among cases suspected of mpox in Ethiopia, emphasizing the critical need for differential diagnostic testing during mpox or VZV outbreaks and routine surveillance. Notably, VZV was detected across all demographic groups and regions, indicating widespread transmission. The identification of multiple VZV clades in multiple regions suggests the need for in-depth investigations to elucidate the transmission dynamics and evolutionary patterns of VZV within Ethiopia.

Building on the findings detailed herein, several priorities emerge to strengthen VZV detection, surveillance, control, and research in Ethiopia. First, a surveillance system should be designed and strengthened to systematically monitor the distribution and impact of VZV. This also needs in building and strengthening differential diagnostic capacities including multiplex testing and establishing genomic sequencing capacities for epidemic intelligence and outbreak response. Second, longitudinal studies (with larger cohorts) are needed to better understand the chickenpox burden in the country and to assess VZV reactivation patterns and monitor clade evolution over time. This will provide insights into disease dynamics and potential shifts in genetic diversity. Finally, collaboration with African genomic centers and reference laboratories should be strengthened for timely outbreak confirmation and data sharing and overall regional capacity building in diseases intelligence and outbreak response.

Data availability

All the data are available within the manuscript and its supplemental materials. The VZV genome data are uploaded to NCBI ([https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/](https:/www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)) and are publicly accessible with accession numbers: SAMN51699733-40 and BioProject accession number: PRJNA1331950. No personal identifiable information was included in any of these uploaded sequences.

References

Sagdat, K., Batyrkhan, A. & Kanayeva, D. Exploring monkeypox virus proteins and rapid detection techniques. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 14, 1414224. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2024.1414224 (2024).

World Health Organization (WHO). Global Mpox Trends [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 8]. Available from: https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/#sec-global

Taylor, L. WHO declares mpox emergency over but says threat remains [Internet]. News; [cited 2025 Sep 12]. (2025). Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/390/bmj.r1908

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Director-General declares mpox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern, 14 August 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/14-08-2024-who-director-general-declares-mpox-outbreak-a-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern

Wang, X. & Lun, W. Skin manifestation of human Monkeypox. J. Clin. Med. 12(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12030914 (2023).

Riche, E. et al. Differences and similarities between Monkeypox and Chickenpox in children during an outbreak. Travel Med Infect Dis [Internet]. ;58(January):102687. (2024). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2024.102687

Ministry of Health Malaysia. Mpox management in Malaysia: Management of outpatient Suspected mpox case in healthcare facilities; Differences between mpox and other Diagnosis [Internet]. (2025). Available from: https://mpox.moh.gov.my/ms/petugas-kesihatan/garis-panduan-mpox

World Health Organization (WHO). Measles [Internet]. (2018). Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/immunization/vpd_surveillance/vpd-surveillance-standards-publication/who-surveillancevaccinepreventable-11-measles-r2.pdf

World Health Organization (WHO). Herpes simplex virus [Internet]. (2025). Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/herpes-simplex-virus

Martins-Filho, P. R. et al. First reports of Monkeypox and varicella-zoster virus coinfection in the global human Monkeypox outbreak in 2022. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 51, 102510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102510 (2023).

World Health Organization (WHO). Diagnostic testing for the monkeypox virus (MPXV): interim guidance, 10 May 2024. ;(May):1–18. (2024). Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MPX-Laboratory-2024.1

Israeli, O. et al. Rapid amplicon nanopore sequencing (RANS) for the differential diagnosis of monkeypox virus and other vesicle-forming pathogens. Viruses 14(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/v14081817 (2022).

Malik, W. et al. Delayed recognition of Mpox on an inpatient psychiatric unit: A case report and investigation. Antimicrob. Steward Healthc. Epidemiol. 5 (1), 1–3 (2025).

Rahi, M., Joy, S. & Sharma, A. Public health challenges in the context of the global spread of Mpox infections. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 108 (4), 641–645 (2023).

Jezek, Z., Szczeniowski, M., Paluku, K. M., Mutombo, M. & Grab, B. Human monkeypox: confusion with chickenpox. Acta Trop. 45 (4), 297–307 (1988).

Bozzola, E. & Bozzola, M. Varicella complications and universal immunization. J Pediatr (Rio J) [Internet]. 92(4):328–30. (2016). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedp.2016.05.008

Lo Presti, C., Curti, C., Montana, M., Bornet, C. & Vanelle, P. Chickenpox: An update. Med Mal Infect [Internet]. 49(1):1–8. (2019). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2018.04.395

Leung, J. et al. Shongo Lushima R. Varicella in the Tshuapa Province, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2009–2014. Trop. Med. Int. Heal. 24 (7), 839–848 (2019).

Tilahun, H., Alayu, M., Demssie, M. & Yalew, T. Suspected chicken pox outbreak investigation and response in Yirga Chefe Town, Ethiopia, August 2018. Int. J. Infect. Dis. Ther. 5 (3), 70 (2020).

Varela, F. H., Pinto, L. A. & Scotta, M. C. Global impact of varicella vaccination programs. Hum Vaccines Immunother [Internet]. ;15(3):645–57. (2019). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2018.1546525

Hussey, H. S. et al. Varicella Zoster virus-associated morbidity and mortality in africa: A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 6 (4), 1–6 (2016).

Gershon, A. A. et al. Varicella zoster virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Prim [Internet]. ;1(July):1–19. (2015). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.16

Hanif, S. et al. A hidden dilemma; post COVID-19 first detection of Varicella zoster M4 genotype from Pakistan. Acta Trop [Internet]. ;253(February):107162. (2024). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2024.107162

Hughes, C. M. et al. A Tale of two viruses: coinfections of Monkeypox and varicella Zoster virus in the Democratic Republic of congo. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 104 (2), 604–611 (2021).

Stephen, R. et al. The epidemiological trend of Monkeypox and Monkeypox-varicella Zoster viruses co-infection in North-Eastern Nigeria. Front. Public. Heal. 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1066589 (2022).

Wang, Y., Sibaii, F., Lee, K., Gill, J. & Hatch, M. L. J. High prevalence of varicella Zoster virus infection among persons with suspect Mpox cases during an Mpox outbreak in Kenya, 2024. MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.04.08.25325502 (2025).

Adelino, T. É. R. et al. Differential diagnosis of exanthematous viruses during the 2022 Mpox outbreak in Minas Gerais, Brazil. J. Clin. Microbiol. 62 (6), 1–13 (2024).

Mande, G. et al. Enhanced surveillance of monkeypox in Bas-Uélé, Democratic Republic of Congo: the limitations of symptom-based case definitions. Int J Infect Dis [Internet]. ;122:647–55. (2022). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.06.060

Nadtoka, M. I. et al. Studying the genetic diversity of the varicella-zoster virus in selected regions of the Russian Federation using high-throughput sequencing. J Microbiol Epidemiol Immunobiol [Internet]. ;100(5):267–75. (2023). Available from: https://doi.org/10.36233/0372-9311-423

Nyayanit, D. A. et al. Molecular characterization of varicella Zoster virus isolated from clinical samples in India. Indian J. Med. Res. 154 (4), 517–520 (2021).

Depledge, D. P. et al. Evolution of cocirculating Varicella-Zoster virus genotypes during a chickenpox outbreak in Guinea-Bissau. J. Virol. 88 (24), 13936–13946 (2014).

YawnBP et al. A population-based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes Zoster before Zoster vaccine introduction. Mayo Clin. Proc. 82 (11), 1341–1349 (2007).

Zeng, T. et al. Clinical symptoms and molecular epidemiologic characteristics of varicella patients among children and adults in Ganzhou, China. Virol. J. 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-025-02661-6 (2025).

Kumar, A. et al. First detection of Varicella Zoster Virus clade 9 cases in India during mpox surveillance. Ann Med [Internet]. ;55(2). (2023). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2023.2253733

The World Bank. The World Bank in Ethiopia [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 11]. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ethiopia/overview

Ethiopian Statistical Services. Projected Population of Ethiopia 2025 [Internet]. (2025). Available from: https://ess.gov.et/download/projected-population-of-ethiopia-2025/

Embassy of Ethiopia Washington DC. Overview About Ethiopia [Internet]. Available from: https://ethiopianembassy.org/overview-about-ethiopia/

Ethiopian Public Health Institute. Public Health Emergency Management Guideline for Ethiopia (Second ed., Dec.2022) [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 May 18]. Available from: https://eweb.ephi.gov.et/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/PHEM_Guideline_Second_Edition_2023.pdf

World Health Organization (WHO). Mpox: Multi-country External Situation Report no.54 Mpox [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 9]. pp. 1–10. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/multi-country-outbreak-of-mpox--external-situation-report--54---27-june-2025

Ethiopian Public Health Institute. Public health Emergency Management(PHEM). Interim Guide for Mpox Surveillance and Contact Tracing. (2022).

WHO Health Emergencies Programme. Surveillance, case investigation and contact tracing for monkeypox. World Heal Organ [Internet]. ;(August):1–12. (2022). Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MPX-Surveillance-2022.3

Altona Diagnostics GmbH, RealStar & PCR Kit Instructions for Use. ; (2016). Available from: https://altona-diagnostics.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/RealStar-VZV-PCR-Kit-1.0_WEB_CE_EN-S02.pdf

Sims, D., Sudbery, I., Ilott, N. E., Heger, A. & Ponting, C. P. Sequencing depth and coverage: key considerations in genomic analyses. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15 (2), 121–132 (2014).

MicroBioGenoHub. VaricellaGen Pipline [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 May 1]. Available from: https://github.com/MicroBioGenoHub/VaricellaGen

Onyeaghala, C. et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation and outcome of human Mpox in rivers State, Nigeria during the 2022-23 outbreak: an observational retrospective study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 50 (5), 1–8 (2025).

US-Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/hcp/laboratories/index.html

Titanji, B. K., Hazra, A. & Zucker, J. Mpox clinical Presentation, diagnostic Approaches, and treatment strategies: A review. JAMA 332, 19 (2024).

Africa, C. D. C. Mpox Testing Strategy [Internet]. (2024). Available from: https://africacdc.org/download/mpox-testing-strategy-november-2024/

Suryam, V. & Das, A. L. Chickenpox appearing in previously vaccinated individuals. Med J Armed Forces India [Internet]. 65(3):280–1. (2009). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-1237(09)80028-2

Bardach, A. E. et al. Herpes Zoster epidemiology in Latin america: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 16 (8 August), 1–19 (2021).

Quinlivan, M. et al. The molecular epidemiology of varicella-zoster virus: evidence for geographic segregation. J. Infect. Dis. 186 (7), 888–894 (2002).

Federal Negarit Gazette of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 26]. (2023). Available from: https://ephi.gov.et/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/1.-EPHI-REGULATION-2015-E.C-The-LATEST-one-1-1.pdf

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the UKHSA, Africa CDC, WHO, U.S. CDC and OSU GOHi for logistic and technical support provided for laboratory testing. We appreciate the support provided from the Institute National de Recherche Biomédicale (INRB), DRC and the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD), South Africa for the technical support in VZV sequence generation and specimen re-checking respectively. We are grateful to all supervisors who provided input and guidance in conducting the assessment and generating this report. We would also like to thank the regional health bureaus and public health institutes and experts involved during suspected mpox case investigation and screening activities. Finally, we acknowledge all study participants and data collectors, and laboratory experts involved in this study.

Funding

This research received no external specific funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.T, A.G and T.B drafted the main manuscript, A.T., A.A., W.S. and B.A. conducted laboratory analysis and/or WGS; A.T., H.O., A.G. L.G. conducted data analysis; A.T., H. O., S.K., M.G, LD. and B.A. conducted bioinformatics analysis; A.T., N.K., M.A, B.A., P.M., D.W., S.T., G.T., M.K, C.L., M.H, D.A.A, M.A., and M.W. supervised the work, administered the project and/or secured resources; S.K., H.A. and D.A.A. critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tayachew, A., Kebede, N., Alayu, M. et al. Genomic evidence of varicella-zoster virus among Mpox-suspected cases in Ethiopia during the 2022 Mpox multi-country outbreak. Sci Rep 16, 148 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29116-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29116-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Targeted metagenomics reveals hidden chickenpox epidemic amid Mpox surveillance in Uganda

Scientific Reports (2026)