Abstract

Altered DNA methylation (DNAm) patterns have been proven to play a key role in Crohn’s disease (CD) pathogenesis. However, DNAm and its association with disease status in Chinese CD remain unclear. This study systematically examines DNAm patterns in Chinese patients with CD and their association with disease status. By elucidating specific DNAm alterations involved in CD pathogenesis, it aims to provide a molecular foundation for early diagnosis, prognosis assessment, and personalized treatment strategies. In this study, 24 adult treatment-naïve patients with CD were enrolled between January 2022 and May 2023. We performed reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) on paired inflamed and non-inflamed intestinal mucosa samples from these patients, and inflammation-specific and disease severity-specific differential methylation signatures were identified. A total of 17,097 differentially methylated sites (DMCs) and 2,687 differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were identified in inflamed mucosa. Biological association analysis revealed that inflammation-associated DMRs were enriched in immune function, with 123 DMRs annotating 89 genes involved in immune cell function while 173 DMRs annotating 117 genes participated in cell adhesion function. Analysis of DNAm profiles of inflamed mucosal samples by disease severity revealed that 389 DMRs were associated with the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD) and 327 DMRs with the Crohn Disease Activity Index (CDAI). Of these, six genes, KDM4B, CLDN15, PGGHG, SLC25A10, KIAA2013, and N4BP1, were significantly associated with inflammation, SES-CD and CDAI. Hence, DNAm reflects immunological changes in the gut of CD patients and discriminates patients based on disease severity, highlighting its potential as a predictive marker for disease management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is characterized by chronic relapsing inflammation that can affect any segment of the digestive tract, as observed in Crohn’s disease (CD), or be limited to the colon, as seen in ulcerative colitis (UC). The prevalence of IBD is increasing, especially in Eastern countries. IBD arises in the context of intricate interplays between genome, epigenome, gut microbiota, immune dysregulation and the environment, the full understanding of which remains elusive. Large-scale genome-wide association studies have revealed over 200 disease-associated loci, yet the overall genetic contribution to IBD risk remains modest, estimated at 13.1% for CD and 8.2% for UC1,2,3. Recently, epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation (DNAm), histone modifications, and miRNA synthesis, have been recognized as plausible mechanisms for both initiating and sustaining intestinal mucosal inflammation in human IBD4.

Remarkably, the most consistent progress in understanding DNAm changes in IBD has been achieved due to technological innovations for genome-wide methylation assessment. For instance, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of peripheral blood DNAm studies in IBD observed differentially methylated positions (DMPs), such as VMP1/TMEM49/MIR21 and RPS6KA2, were consistently differentially methylated across all studies5. However, DNAm changes in peripheral blood cells are primarily associated with inflammatory status rather than disease status6. It also found that methylation patterns in blood tend to revert to “normal” following anti-inflammatory treatment, irrespective of the underlying disease state. Consequently, an increasing number of studies have focused on the DNA methylome of specific mucosal cell types in IBD, including epithelial cells7,8,9, adipose stem cells10, and CD4+ lymphocytes11. These studies have unveiled distinct DNAm patterns linked to inflammation and different disease subtypes. Additionally, investigations into genome-wide DNAm in the intestinal tissue of UC have identified specific DNAm alterations associated with genetic variations, disease status, severity, and clinical outcomes12,13,14. However, the differentiation in DNAm between inflamed and non-inflamed mucosa, as well as the relationship between DNAm and disease severity in treatment-naïve CD patients, remains unclear.

This study analyzed the DNAm profiles in the mucosa of treatment-naïve CD patients and examined the correlation between DNAm patterns and disease severity. It aims to investigate the role of inflammation-associated DNAm in the immune signaling pathways of CD and to identify specific DNAm alterations that are significantly associated with disease severity, thereby enhancing the management of CD.

Methods

Patient enrollment and sample collection

All patient recruitment and sample collection were performed under full ethical approval from the Ruijin Hospital Ethics Committee, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine (2019 − 186). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and all methods were performed according to the relevant guidelines and regulations15,16,17. This study enrolled 24 consecutive adult patients with treatment-naïve Crohn’s disease between January 2022 and May 2023. The diagnosis of CD requires a comprehensive evaluation based on clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, endoscopic examinations and histopathological analyses in accordance with guideline18. A paired tissue sample consists of two specimens obtained from the same patient during a single colonoscopic examination: one from the diseased tissue (inflammatory regions) and the other from adjacent normal tissue. Typical preparatory protocols preceding a colonoscopy include dietary modifications, the administration of oral laxatives, and the suspension of certain medications, among other interventions19. All participants adhere to a standardized bowel preparation regimen and subsequently undergo a colonoscopic examination. The area around the ulcer was inflammation site, and biopsy should be performed on the surrounding area, rather than at the base of the ulcer. Biopsies were obtained from intestinal segments exhibiting the most pronounced inflammation and ulceration. Four biopsies were collected from both inflamed and non-inflamed sites and stored at − 80 °C. The key clinical characteristics, including age, gender, disease location (according to Montreal classification), Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD)20, Crohn Disease Activity Index (CDAI)21,22, and behaviour, were collected (Table 1). Informed consent was obtained from all patients in this study.

DNA extraction and RRBS

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples from CD patients were underwent DNA extraction using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany)23. Quality control measures were implemented to ensure the integrity of the extracted DNA samples. The methylation status of CpG sites was assessed using the reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) method, as previously described24. A DNA input ranging from 50 ng to 100 ng was digested with the MspI enzyme prior to ligation with a methylated adaptor containing complementary sticky ends. Subsequently, the ligation products underwent bisulfite conversion using the Methylcode Bisulfite Conversion Kit (ThermoFisher, MECOV50), followed by purification and recovery steps25,26. To introduce a barcode for Illumina sequencing, the converted DNA was amplified. Finally, the libraries were sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq X10 platform27,28.

DNA methylation analysis

The Illumina bcl2fastq software was performed to do the demultiplexing of reads (https://support.illumina.com/sequencing/sequencing_software/bcl2fastq-conversion-software.html). FASTQ data were adapter-trimmed by the first 2 bases from each end with trim-galore (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore). Single-end reads were generated by merging the paired-end read FASTQ files. The single-end reads were aligned to the bisulfite-converted human reference genome (version hg19) using Bismark29 and Bowtie v.130, resulting in BAM files. The mapped bam files were subsequently utilized for further analysis. CpG methyRate calculating was performed with Bismark to identify the differentially methylated sites (DMCs) between inflamed and non-inflamed samples from CD patients. A minimum of five CpG sites was required to define a differentially methylated region (DMR). p-values were adjusted using the false discovery rate (FDR). The definitive DMCs were selected using the following criteria: an absolute methylation difference (|Δβ value|) of at least 10 and a corrected p-value (P.adjust) below 0.0001. Likewise, the definitive DMRs between inflamed and non-inflamed samples were determined by a threshold of |Δβ value| ≥ 10 coupled with a P.adjust < 0.01. For subgroup analyses stratified by SES-CD and CDAI, the DMR criteria were adjusted to an |Δβ value| ≥ 10 and a P.adjust < 0.05.

Statistical analysis

The volcano plot was generated using the ggplot2 package in R software (version 4.3.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and the heatmap was constructed with the pheatmap package in R31. Gene Ontology (GO) for biological process enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment (www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html)32,33,34 analyses were performed for genes annotated to DMRs using R with the BiocManager package clusterProfiler35,36. KEGG copyright permission is 251,684. To cluster similarity matrices of the GO terms, the simplifyEnrichment R package was implemented for visualizing, summarizing, and comparing the clusterings37. The VennDiagram R package was used to create a Venn diagram to illustrate the intersection of the DMRs. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney tests were used to compare distributions between two groups. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses for the two groups in Figs. 1 and 3 were conducted using R version 4.3.2, while those for the two groups in Fig. 4 were performed with GraphPad Prism version 9.0.

Differential methylation analysis of inflamed and non-inflamed mucosae from CD patients. (A) A volcano plot based on DMRs (P.adjust < 0.01, |Δβ value| ≥ 10). Blue represents hypomethylation sites, while red represents hypermethylation sites. (B) A total of 1933 DMRs were hypermethylated (upper), while 764 DMRs were hypomethylated (lower) (p-values calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test). (C) Pie charts illustrate functional genomic distribution of hypermethylated (upper) and hypomethylated DMRs (lower). (D) A heatmap of DMRs identified in inflamed and non-inflamed mucosae. Each row represents a DMR based tag. Each column represents a tissue specimen. The brown represents inflamed samples, and the green represents the non-inflamed ones. Yellow indicates increased DNA methylation in inflamed tissues compared to non-inflamed tissues, blue indicates decreased DNA methylation in inflamed tissues. ***P<0.001.

Results

Identification of inflammation-associated methylation signatures in CD

A total of 17,097 DMCs (Additional file 1) and 2,687 DMRs (Additional file 2) were identified between inflamed and non-inflamed mucosae. Significant DMR differences, with more hypermethylated DMR and reduced hypomethylated DMR were observed in inflamed regions than in non-inflamed regions (Fig. 1A-B). The majority of DMRs were in promoter regions (32%) and intron regions (31%). Specifically, hypermethylated DMRs were predominantly present in promoter regions (33%) and intron regions (30%), while hypomethylated DMRs showed a similar distribution in promoter regions (31%) and intron regions (32%) (Fig. 1C). Heatmap revealed a clear visual distinction of methylation features between the two groups (Fig. 1D). The top 10 DMRs are presented in Table 2.

Immunological relevance of inflammation-associated DMRs in CD

GO analysis for biological process enrichment revealed that the set of genes (n = 2,028) annotated to our inflammation-associated DMRs were enriched in immune function, including changes in immune cell proliferation, activation, and differentiation (Additional file 3). After clustering the similarity matrices of the 221 biological process terms, 14 clusters were obtained with 8 of these clusters containing at least five biological processes each (Fig. 2A). In alignment with our priori hypotheses, two clusters, immune cell function and cell adhesion were closely related to the immunology of IBD (Table 3). Intriguingly, several other clusters pointed towards a convergence with epithelial development and proliferation pathways, suggesting a broader impact of the identified DMRs on both immune regulation and tissue homeostasis. The cluster of immune cell functions comprises 14 biological processes and involves 89 genes, corresponding to 123 DMRs (Additional file 4). Similarly, the cluster of cell adhesion includes seven biological processes and 117 genes, accounting for 173 DMRs (Additional file 5). To prioritize the most significant DMRs, we ranked them based on P.adjust and listed them in Supplementary Table 1, for further examination. Among the genes annotated to these DMRs, the methylation of JAK3, SBNO2, LIMK1, CXCL5, and RUNX3 has been reported to associated with IBD, confirming the findings of previous studies38,39,40,41,42. The top 20 biological processes associated with immunology were presented in a bubble chart (Fig. 2B). KEGG enrichment analysis revealed nine significant pathways, including axon guidance, the Rap1 signaling pathway, regulation of actin cytoskeleton, Yersinia infection, the Notch signaling pathway, focal adhesion, Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis, bacterial invasion of epithelial cells, and pathogenic Escherichia coli infection (Fig. 2C). These signaling pathways play crucial roles in various biological processes, including immune regulation, inflammatory responses, cell migration, and cell adhesion, and are intimately linked to the pathological mechanisms underlying IBD.

Biological relevance of the inflammation-associated DMRs in CD. (A) Similarity matrix of 221 biological process terms obtained from the enrichment analysis of genes mapped by the inflammation-associated DMRs. (B) The top 20 biological processes related to immunology, identified through GO enrichment analysis. (C) Enriched KEGG categories for DMRs.

Methylation signatures were associated with disease severity in CD

As a proof-of-concept, we further investigated whether DNAm could distinguish patients with CD based on their disease severity. We compared the inflamed mucosae from 10 patients with mild CD (0 < SES-CD ≤ 3) to 12 patients with moderate CD (4 < SES-CD ≤ 6) and 2 patients with severe CD (SES-CD ≥ 7). The analysis revealed significant DNAm differences between patients with mild CD and those with moderate to severe (serious) CD. A total of 9,029 DMCs (Additional file 6) and 389 DMRs (Additional file 7) were identified based on a P.adjust < 0.05 (Fig. 3A). Among these, 291 were hypermethylated and 98 were hypomethylated (Fig. 3B). Most DMRs were located in promoter regions (33%) and intron regions (26%). Hyper- and hypomethylated DMRs were similarly distributed, with 32% and 36% in promoter regions and 27% and 20% in intron regions, respectively (Fig. 3C). Importantly, a heatmap shows the top 100 DMRs based on P.adjust displayed a clear visual distinction between mild and moderate to severe mucosae from CD patients, indicating unique DNAm patterns associated with disease severity (Fig. 3D). DMRs associated with both SES-CD and inflammation are displayed in Table 4. Likewise, we compared the inflamed mucosae from 5 patients with mild CD (150 < CDAI < 220) to 16 patients with moderate CD (221 < CDAI < 450) and 3 patients with severe CD (CDAI > 450). A total of 9,268 DMCs (Additional file 8) and 327 DMRs (Additional file 9) were identified, with 201 being hypermethylated and 126 hypomethylated (Fig. 3E-F). The global distribution of hypermethylated and hypomethylated DMRs was like that compared by SES-CD (Fig. 3G). A heatmap results of the top 100 DMRs displayed an unclear visual distinction between mild and moderate to severe mucosae from CD patients (Fig. 3H). We identified 18 DMRs associated with both CDAI and inflammation. However, only SLC25A10 has been reported to be associated with IBD (Table 5).

Differential methylation analysis of inflamed mucosae categorized by SES-CD and CDAI scores. (A) A volcano plot based on DMRs (P.adjust < 0.05, |Δβ value| ≥ 10) between mild and moderate to severe (serious) inflamed mucosal samples. Blue represents hypomethylation sites, while red represents hypermethylation sites. (B) A total of 291 DMRs were hypermethylated (upper), while 98 DMRs were hypomethylated (lower). (C) Pie charts illustrate functional genomic distribution of hypermethylated (upper) and hypomethylated DMRs (lower). (D) A heatmap of DMRs identified in mild and serious inflamed mucosal samples from CD patients categorized by SES-CD score. (E) A volcano plot based on DMRs (P.adjust < 0.05, |Δβ value| ≥ 10) between mild and moderate to severe (serious) inflamed mucosal samples. Blue represents hypomethylation sites, while red represents hypermethylation sites. (F) A total of 291 DMRs were hypermethylated (upper), while 98 DMRs were hypomethylated (lower). (G) Pie charts illustrate the proportion of genome-wide coverage of hypermethylated (upper) and hypomethylated (lower) DMRs. (H) A heatmap indicated the top 100 DMRs profile between mild and serious inflamed mucosal samples from CD patients categorized by CDAI score. Each row represents a DMR based tag. Each column represents a tissue specimen. The brown represents mild samples, and the green represents the serious ones. Yellow indicates increased DNA methylation in serious tissues compared to mild tissues, blue indicates decreased DNA methylation in serious tissues. ***P<0.001.

Disease severity-specific inflammatory DMRs

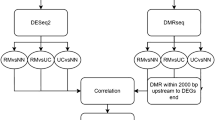

To further select DNAm signatures specific to inflammation and disease severity in CD, we compared inflammation-associated DMRs with those identified in subgroups categorized by the SES-CD and CDAI. We found significant overlap within these groups of DMRs, particularly between inflammation-associated DMRs and those associated with severe disease status (Fig. 4A). Subsequently, we identified DMRs that were simultaneously hypermethylated or hypomethylated in both inflammation-associated and severe disease status-associated DMRs. This screen identified 36 shared DMRs between high SES-CD-associated and high CDAI-associated DMRs, of which 6 were also inflammation-associated (Fig. 4B). Of these six DMRs, KDM4B and CLDN15 showed the most significant differences between groups (P < 0.001).

Relationship between DNA methylation signatures of inflammation and disease severity. (A) Study design and the workflow of finding disease severity-specific inflammatory DMRs. Upon 24 patient admission, clinical information was collected, and paired tissues were obtained for RRBS. We compared inflammation-associated DMRs with those identified in subgroups categorized by the SES-CD and CDAI. A Venn diagram displays the intersection of DMRs associated with inflammation, SES-CD and CDAI. (B) Six shared DMRs exhibit a consistent pattern of hypermethylation across inflammation, high SES-CD, and high CDAI conditions.

Discussion

Over the past decades, extensive research has established a strong correlation between DNAm and the pathogenesis of IBD. Studies have shown that altered DNAm patterns in the circulation of IBD patients reflect inflammatory states and correlate with disease progression, treatment response, and genetic variants. Despite identifying methylation changes in disease tissues and specific cell types in IBD, the precise differences in DNAm between inflamed and non-inflamed mucosa, and their impact on disease severity and clinical outcomes in treatment-naïve CD patients, remain unclear. In this study, we utilized a treatment-naïve CD cohort to uncover distinct methylation patterns between inflamed and non-inflamed mucosae, as well as between inflamed mucosae of CD patients with varying disease severity.

We first demonstrated that significant DMRs were identified between inflamed and non-inflamed mucosa in CD, with most of them being hypermethylated (1,933 hypermethylated DMRs and 754 hypomethylated DMRs). The majority of these DMRs were located in gene body regions, including exons and introns, and secondarily in promoter and distal intergenic regions. This localization pattern aligns well with the DMC outcomes reported in previous investigations, which compared colonoscopy samples of CD patients against healthy controls utilizing the HumanMethylation450K BeadChip platform43. Notably, no significant differences in the distribution patterns were discerned between hypermethylated and hypomethylated DMRs. Furthermore, several genes annotated to the most prominent DMRs. Among the genes annotated as DMRs, PKD144, RNF18645 and TPPP346 have been implicated in the pathogenesis of UC, while RUNX347 as a gene associated with IBD susceptibility. In addition, other notable DMRs have been shown to act as biomarkers of malignancy in a variety of cancers48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56, suggesting their potential role in CD. Notably RNF186 and RUNX3, have been previously implicated in UC, highlighting the potential involvement of inflammation-associated DMRs in the underlying mechanisms of CD 42,57,58.

The intestinal immune system, composed of the intestinal epithelium, immune cells, and the gut microbiota, plays a crucial role in maintaining gut health. IBD arises from an atypical immune reaction to gut microorganisms in individuals with a genetic predisposition; however, the detailed mechanisms underlying this condition are still being elucidated. GO analysis revealed that the 2,028 genes associated with inflammation-related DMRs are significantly enriched in immune-related biological processes, including immune cell proliferation, activation, and differentiation. This enrichment underscores the pivotal role of epigenetic modifications in orchestrating immune responses central to CD pathology. Notably, the clustering of biological processes highlighted two major clusters—immune cell function and cell adhesion—that are intrinsically linked to IBD immunology. These findings align with established evidence that immune dysregulation and impaired cell adhesion are critical drivers of IBD pathogenesis. Furthermore, the identification of additional clusters related to epithelial development and proliferation suggests that the epigenetic alterations in CD extend beyond immune regulation to encompass epithelial integrity and tissue homeostasis. This dual impact is consistent with the multifactorial nature of CD, where both immune dysfunction and epithelial barrier defects contribute to disease progression. The interplay between immune cells and epithelial cells is crucial for maintaining intestinal homeostasis, and disruptions in this balance can lead to chronic inflammation and tissue damage observed in CD patients. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis identified nine significant pathways. These pathways are integral to various biological processes such as immune regulation, inflammatory responses, cell migration, and adhesion, all of which are intimately linked to the pathological mechanisms of IBD. The identification of these pathways highlights the complex interplay between immune responses and epithelial cell functions in CD.

Upon conducting a more detailed analysis of the DNAm profiles in the mucosae of patient subgroups categorized by SES-CD and CDAI, we uncovered a substantial number of DMRs. This finding suggests that there are significant epigenetic variations in the mucosal tissues of patients with differing levels of disease activity and severity as measured by these clinical indices. However, the heatmap representation of the top 100 DMRs distinctly visualized a separation between the mild and moderate-to-severe mucosae of CD patients when categorized using the SES-CD, whereas no such clear distinction was observed when utilizing the CDAI. The clear distinction in DNAm patterns between mild and severe CD mucosae, as evidenced by heatmap analyses, indicates that DNA methylation profiles could serve as biomarkers for disease severity and progression. This prognostic potential is particularly valuable for tailoring therapeutic interventions and monitoring treatment efficacy. Additionally, our analysis revealed that several genes annotated to the top 10 DMRs, such as APBB1IP59, SLC25A1060, NLRP661,62 and NOTHC1 63,64have been previously implicated in IBD. FMO565 and ECE166 have been implicated in intestinal inflammation, further validate the relevance of our findings and highlight key players in the epigenetic regulation of CD. These observations contribute to the growing understanding of the role of epigenetics in the progression of IBD and suggest that endoscopic assessments like the SES-CD may be particularly valuable in identifying molecular signatures associated with disease activity. This knowledge could pave the way for the development of more targeted diagnostics and personalized treatment strategies tailored to the specific epigenetic profiles of individual patients.

In our final analysis, we explored the overlaps among DMRs linked to inflammation and disease severity in patients with CD. Our findings revealed that a significant proportion of these shared DMRs display consistent methylation patterns—either hypermethylation or hypomethylation——across inflammation, high SES-CD, and high CDAI-associated DMRs. This consistency suggests that there may be common epigenetic mechanisms underlying the inflammatory process and the severity of the disease as assessed by these clinical metrics. The identification of overlapping DMRs across different evaluations of disease severity highlights the intricate relationship between epigenetic modifications and the pathophysiology of CD. Specifically, the recurring methylation patterns indicate that certain epigenetic changes are central to both the initiation and exacerbation of inflammatory responses in CD patients. These shared epigenetic signatures may serve as critical biomarkers for disease monitoring and prognosis, offering insights into the molecular underpinnings that drive disease progression. Among the shared DMRs, KDM4B and CLDN15 emerged as a particularly noteworthy gene. KDM4B is hypomethylated in favorable clinical outcomes related to high CDAI and SES-CD scores. This inverse relationship implies that distinct methylation patterns may be associated with better disease control and improved patient outcomes, as opposed to those indicative of active disease or higher disease activity. CLDN15 plays a key role in intestinal barrier function. CLDN15 methylation levels are also positively correlated with the occurrence and severity of inflammation, which may influence the permeability of intestinal epithelial cells and exacerbate intestinal inflammatory responses in patients with IBD.

Beyond KDM4B and CLDN15, the consistency of methylation patterns across various DMRs underscores the potential of DNA methylation profiling as a tool for personalized medicine in CD. Future research should focus on the functional validation of identified DMRs and associated genes to uncover their mechanistic roles in CD. Integrating genetic and epigenetic data could provide a more comprehensive understanding of CD susceptibility and progression, elucidating how genetic predispositions interact with epigenetic modifications to drive disease. Moreover, exploring the therapeutic potential of targeting specific epigenetic regulators, such as KDM4B, may pave the way for innovative interventions aimed at restoring immune balance and epithelial integrity in CD patients.

While our study provides significant insights into the epigenetic mechanisms underlying CD, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the relatively small sample size, particularly within the severe CD subgroup, may limit the generalizability of our findings and necessitate validation in larger, independent cohorts. Second, the absence of a well-matched control group restricts our ability to fully contextualize the methylation changes observed in CD patients. Including a healthy control group in future studies would allow for a more comprehensive comparison and enhance the robustness of our conclusions. Additionally, the cross-sectional design of our study precludes establishing causal relationships between DNA methylation (DNAm) changes and disease progression. Longitudinal studies are essential to elucidate the temporal dynamics of epigenetic modifications and their causal roles in CD pathogenesis.

Conclusions

Our study identifies distinct DNAm patterns in inflamed mucosae in treatment-naïve CD patients. These DMRs are involved in immune cell function and cell adhesion, suggesting a potential role in immune modulation and tissue equilibrium in CD. Our analysis further suggests the potential relevance of six inflammation-associated markers, particularly those identified by SES-CD/CDAI, in understanding disease activity and progression.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI-Sequence Read Archive (SRA), PRJNA1278942, and further queries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Jostins, L. et al. Host–microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 491, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11582 (2012).

de Lange, K. M. et al. Genome-wide association study implicates immune activation of multiple integrin genes in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Genet. 49, 256–261. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3760 (2017).

Liu, J. Z. et al. Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nat. Genet. 47, 979–986. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3359 (2015).

Noble, A. J., Nowak, J. K., Adams, A. T., Uhlig, H. H. & Satsangi, J. Defining interactions between the Genome, Epigenome, and the environment in inflammatory bowel disease: progress and prospects. Gastroenterology 165 (e42), 44–60. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2023.03.238 (2023).

Joustra, V. et al. Systematic review and Meta-analysis of peripheral blood DNA methylation studies in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohns Colitis. 17, 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac119 (2023).

Somineni, H. K. et al. Blood-Derived DNA methylation signatures of crohn’s disease and severity of intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology 156, 2254–2265e2253. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.270 (2019).

Barnicle, A., Seoighe, C., Greally, J. M., Golden, A. & Egan, L. J. Inflammation-associated DNA methylation patterns in epithelium of ulcerative colitis. Epigenetics 12, 591–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592294.2017.1334023 (2017).

Howell, K. J. et al. DNA methylation and transcription patterns in intestinal epithelial cells from pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel diseases differentiate disease subtypes and associate with outcome. Gastroenterology 154, 585–598. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.007 (2018).

Kraiczy, J. et al. Assessing DNA methylation in the developing human intestinal epithelium: potential link to inflammatory bowel disease. Mucosal Immunol. 9, 647–658. https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2015.88 (2016).

Serena, C. et al. Adipose stem cells from patients with crohn’s disease show a distinctive DNA methylation pattern. Clin. Epigenetics. 12, 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-020-00843-3 (2020).

Sun, Z. et al. Hypomethylation and overexpression of Th17-Associated genes is a hallmark of intestinal CD4 + Lymphocytes in crohn’s disease. J. Crohns Colitis. 17, 1847–1857. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad093 (2023).

Harris, R. A. et al. DNA methylation-associated colonic mucosal immune and defense responses in treatment-naive pediatric ulcerative colitis. Epigenetics 9, 1131–1137. https://doi.org/10.4161/epi.29446 (2014).

Venkateswaran, S. et al. Longitudinal DNA methylation profiling of the rectal mucosa identifies cell-specific signatures of disease status, severity and clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis cell-specific DNA methylation signatures of UC. Clin. Epigenetics. 15, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-023-01462-4 (2023).

Taman, H. et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation in Treatment-naive ulcerative colitis. J. Crohns Colitis. 12, 1338–1347. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy117 (2018).

Feakins, R. M. British society of, G. Inflammatory bowel disease biopsies: updated British society of gastroenterology reporting guidelines. J. Clin. Pathol. 66, 1005–1026. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2013-201885 (2013).

Hommes, D. W. & van Deventer, S. J. Endoscopy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 126, 1561–1573. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.023 (2004).

Lamb, C. A. et al. British society of gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 68, s1–s106. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318484 (2019).

Gomollon, F. et al. 3rd European Evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of crohn’s disease 2016: part 1: diagnosis and medical management. J. Crohns Colitis. 11, 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw168 (2017).

O’Brien, C. L., Allison, G. E., Grimpen, F. & Pavli, P. Impact of colonoscopy bowel Preparation on intestinal microbiota. PLoS One. 8, e62815. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062815 (2013).

Koutroumpakis, E. & Katsanos, K. H. Implementation of the simple endoscopic activity score in crohn’s disease. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 22, 183–191. https://doi.org/10.4103/1319-3767.182455 (2016).

Best, W. R. Predicting the crohn’s disease activity index from the Harvey-Bradshaw index. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 12, 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MIB.0000215091.77492.2a (2006).

Best, W. R., Becktel, J. M. & Singleton, J. W. Rederived values of the eight coefficients of the crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI). Gastroenterology 77, 843–846 (1979).

Janecka, A., Adamczyk, A. & Gasinska, A. Comparison of eight commercially available kits for DNA extraction from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Anal. Biochem. 476, 8–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2015.01.019 (2015).

Guo, S., Diep, D., Plongthongkum, N., Fung, H. L. & Zhang, K. Identification of methylation haplotype blocks aids in Deconvolution of heterogeneous tissue samples and tumor tissue-of-origin mapping from plasma DNA. Nat. Genet. 49, 635–642. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3805 (2017).

Jia, Z. et al. DNA methylation patterns at and beyond the histological margin of early-stage invasive lung adenocarcinoma radiologically manifested as pure ground-glass opacity. Clin. Epigenetics. 13, 153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-021-01140-3 (2021).

Gu, H. et al. Preparation of reduced representation bisulfite sequencing libraries for genome-scale DNA methylation profiling. Nat. Protoc. 6, 468–481. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2010.190 (2011).

Nair, S. S. et al. Guidelines for whole genome bisulphite sequencing of intact and FFPET DNA on the illumina HiSeq X ten. Epigenetics Chromatin. 11, 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13072-018-0194-0 (2018).

Raine, A., Liljedahl, U. & Nordlund, J. Data quality of whole genome bisulfite sequencing on illumina platforms. PLoS One. 13, e0195972. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195972 (2018).

Krueger, F. & Andrews, S. R. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics 27, 1571–1572. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr167 (2011).

Langmead, B. Aligning short sequencing reads with Bowtie. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics Chap. 11, Unit 11 17, (2010). https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi1107s32

Ito, K. & Murphy, D. Application of ggplot2 to pharmacometric graphics. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 2, e79. https://doi.org/10.1038/psp.2013.56 (2013).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. ClusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS: J. Integr. Biology. 16, 284–287. https://doi.org/10.1089/omi.2011.0118 (2012).

Wu, T. et al. ClusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innov. (Camb). 2, 100141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141 (2021).

Gu, Z., Hübschmann, D. & SimplifyEnrichment A bioconductor package for clustering and visualizing functional enrichment results. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 21, 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2022.04.008 (2023).

Agliata, I. et al. The DNA methylome of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) reflects intrinsic and extrinsic factors in intestinal mucosal cells. Epigenetics 15, 1068–1082. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592294.2020.1748916 (2020).

Kalla, R. et al. Analysis of systemic epigenetic alterations in inflammatory bowel disease: defining Geographical, genetic and Immune-Inflammatory influences on the Circulating methylome. J. Crohns Colitis. 17, 170–184. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac127 (2023).

Meng, W. et al. DNA methylation fine-tunes pro-and anti-inflammatory signalling pathways in inactive ulcerative colitis tissue biopsies. Sci. Rep. 14, 6789. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57440-0 (2024).

Gould, N. J. D., Davidson, K. L. M., Nwokolo, C. U. & Arasaradnam, R. P. A systematic review of the role of DNA methylation on inflammatory genes in ulcerative colitis. Epigenomics 8, 667–684. https://doi.org/10.2217/epi-2016-0006 (2016).

Dybska, E. et al. Methylation of RUNX3 promoter 2 in the whole blood of children with ulcerative colitis. Genes 13, 1568 (2022).

Kim, T. O. et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of the DNA Methylation Profile Identifies the Fragile Histidine Triad (FHIT) Gene as a New Promising Biomarker of Crohn’s Disease. J. Clin. Med. 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051338 (2020).

Nielsen, D. S. G., Fredborg, M., Andersen, V. & Purup, S. Administration of protein kinase D1 induces a protective effect on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced intestinal inflammation in a Co-Culture model of intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells and RAW264.7 macrophage cells. Int. J. Inflam. 2017 (9273640). https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9273640 (2017).

Fujimoto, K. et al. Regulation of intestinal homeostasis by the ulcerative colitis-associated gene RNF186. Mucosal Immunol. 10, 446–459. https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2016.58 (2017).

Wen, Y. et al. Transcriptional landscape of intestinal environment in DSS-induced ulcerative colitis mouse model. BMC Gastroenterol. 24, 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-024-03128-8 (2024).

Hantisteanu, S. et al. Runx3 prevents spontaneous colitis by directing the differentiation of anti-inflammatory mononuclear phagocytes. PLoS One. 15, e0233044. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233044 (2020).

Hu, H. F. et al. LINC00982-encoded protein PRDM16-DT regulates CHEK2 splicing to suppress colorectal cancer metastasis and chemoresistance. Theranostics 14, 3317–3338. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.95485 (2024).

Wang, G. et al. Novel prognosis and therapeutic response model of Immune-Related LncRNA pairs in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Vaccines (Basel). 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10071161 (2022).

Liu, Q., Li, R., Wu, H. & Liang, Z. A novel cuproptosis-related gene model predicts outcomes and treatment responses in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 23, 226. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10678-9 (2023).

Tao, T. et al. Cancer stem cell-specific expression profiles reveal emerging bladder cancer biomarkers and identify circRNA_103809 as an important regulator in bladder cancer. Aging (Albany NY). 12, 3354–3370. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.102816 (2020).

Sun, H., Li, Q., Song, Z. & Li, C. Hypoxia induction of SH2D3A triggers malignant progression of lung cancer. Stem Cell. Res. 58, 102630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scr.2021.102630 (2022).

Fei, X. et al. Identification of Prognosis-Related Molecular Subgroups and Construction of a Prognostic Prediction Model Using Immune-Related Genes in Pancreatic Cancer. J Oncol 7117014, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7117014 (2022).

Ma, F., Zhang, B., Wang, Y. & Lou, C. Long Non-Coding RNA AGAP2-AS1: A comprehensive overview on its biological functions and clinical significances in human cancers. Molecules 29 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29153461 (2024).

Okumura, T. et al. MicroRNA profiles to predict postoperative prognosis in patients with small cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Anticancer Res. 35, 719–727 (2015).

Yoshikawa, Y. et al. Identification of the minimum combination of serum MicroRNAs to predict the recurrence of colorectal cancer cases. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 30, 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-022-12355-w (2023).

McGovern, D. P. et al. Genome-wide association identifies multiple ulcerative colitis susceptibility loci. Nat. Genet. 42, 332–337. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.549 (2010).

Beaudoin, M. et al. Deep resequencing of GWAS loci identifies rare variants in CARD9, IL23R and RNF186 that are associated with ulcerative colitis. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003723. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003723 (2013).

Sun, H. et al. Distinct integrin activation pathways for effector and regulatory T cell trafficking and function. J. Exp. Med. 218 https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20201524 (2021).

Frenkel, S. et al. Genome-wide analysis identifies rare copy number variations associated with inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 14, e0217846. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217846 (2019).

Ranson, N. et al. Nod-Like receptor Pyrin-Containing protein 6 (NLRP6) is Up-regulated in ileal crohn’s disease and differentially expressed in goblet cells. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6 (e118), 110–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.03.001 (2018).

Alipour, M. et al. Mucosal barrier depletion and loss of bacterial diversity are primary abnormalities in paediatric ulcerative colitis. J. Crohns Colitis. 10, 462–471. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv223 (2016).

Huang, R. et al. Disparity expression of Notch1 in benign and malignant colorectal diseases. PLoS One. 8, e81005. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081005 (2013).

Dahan, S. et al. Notch-1 signaling regulates intestinal epithelial barrier function, through interaction with CD4 + T cells, in mice and humans. Gastroenterology 140, 550–559. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.057 (2011).

Schaller, M. L. et al. Fmo5 plays a sex-specific role in goblet cell maturation and mucus barrier formation. BioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.05.588360 (2024).

Law, I. K., Murphy, J. E., Bakirtzi, K., Bunnett, N. W. & Pothoulakis, C. Neurotensin-induced Proinflammatory signaling in human colonocytes is regulated by beta-arrestins and endothelin-converting enzyme-1-dependent endocytosis and resensitization of neurotensin receptor 1. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 15066–15075. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.327262 (2012).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32470951), Shanghai Municipal Health Planning Commission (202340092, 202240038), Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology (22ZR1439600).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZTW, LW and JZ designed the research studies. TYZ, QWL, QYH and CXG conducted the experiments. WYX and ZTW analyzed the data. TYZ and QWL wrote the manuscript. All authors approved final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T., Lin, Q., Xu, Wy. et al. Mucosal DNA methylation reveals immune-related methylation profile and correlates with crohn’s disease status. Sci Rep 16, 2848 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29123-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29123-x