Abstract

The molecular mechanism of vascular atrophy and remodeling after arterial transplantation into a venous environment remains unclear. This study grafted the common carotid artery of New Zealand white rabbits into the external jugular vein to establish an animal model of arterial mechanical unloading. Its efficacy was verified by ultrasound. Immunohistochemical methodologies, transmission electron microscopy, and TUNEL staining showed vascular morphology changes. Genomic analysis, proteomic profiling, iPathway guide (IPG) analysis, gene overexpression/silenced, flow cytometry, and stretch testing were applied to elucidate the molecular mechanisms. Comparative analysis between the arterial graft and the control group revealed the successful preparation of the animal model in vitro. Morphological examination indicated that atrophy under venous flow mechanics is predominantly attributed to the apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). Bioinformatics results proved that thrombospondin-4 (THBS4) plays a pivotal role in vascular remodeling via the focal adhesion pathway. Experiments demonstrated THBS4’s regulation of VSMCs apoptosis and its relation with low stretch tension. This study was the first to introduce gene transcriptomics and proteomics into the arterial mechanical unloading animal model and the first to demonstrate the role of THBS4 in promoting VSMCs apoptosis. Consequently, THBS4 emerges as a promising therapeutic target for the prevention of intimal hyperplasia post-vascular transplantation in vascular surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) remarkably improves patient survival rates, and clinical data demonstrate excellent long-term patency rates with autologous arterial grafts, especially the internal thoracic artery1,2. Although arterial grafting significantly improves long-term patency rate, it is difficult to obtain and is limited in length, therefore, saphenous vein grafting remains the mainstay of clinical practice3. Unfortunately, up to 50% of patients experience late vein graft failure within 10 years due to intimal hyperplasia, and there are no effective interventions to reduce the intimal hyperplasia and subsequent atherosclerosis that leads to graft failure4. To date, the molecular mechanisms underlying the long-term patency of arterial grafts remain unclear. It is urgent to study the molecular mechanism of arterial resistance to intimal hyperplasia and maintaining long-term patency, which has important clinical guiding significance for improving the patency rate of clinical vein transplantation.

As we all know, saphenous vein has larger diameter than coronary artery, and its blood pressure and vascular tension are low, while coronary artery has higher blood pressure and vascular tension. Therefore, after CABG, the hemodynamic environment changes significantly due to the mismatch of venous diameter, the difference of vascular tension and pressure5. These changes mainly stimulate the morphological and functional changes of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), which transform from the contractile phenotype to the synthetic phenotype4,6,7. This leads to cell proliferation, migration and the deposition of extracellular matrix components, thus causing changes in vascular morphology and function, such as intimal hyperplasia, to cope with the sudden changes in the hemodynamic environment4,6,7. On the contrary, these changes will not happen after internal thoracic artery transplantation. This may be because its diameter is equivalent to that of coronary artery, and the fluctuation of hemodynamic conditions is very small5. Therefore, it can better adapt to arterial circulation. Further comparative studies have shown that VSMCs from the saphenous vein exhibit robust capabilities for proliferation, differentiation, and migration5. However, VSMCs derived from the internal thoracic artery display a higher propensity for apoptosis, which enhances their role in preventing intimal hyperplasia5. Therefore, the research on the regulation of apoptosis in VSMCs holds significant clinical guiding significance for inhibiting intimal hyperplasia of veins.

It is interesting that intimal hyperplasia vascular diseases, such as atherosclerosis, only occur in arteries but not in veins. Theoretically, the level of lipid and glucose in the veins of the same person is higher than that in the arteries. Nevertheless, once a vein is transplanted into an artery, even if the blood lipid and blood glucose levels are normal, under the influence of arterial blood pressure and tension, the transplanted vein will quickly develop intimal hyperplasia7. These phenomena indicate that arterial blood pressure and tension play important roles in changing the structure and function of the vein wall. Then, how would lowering arterial blood pressure and tension affect the structure and function of the artery? Although this hypothesis may reveal potential pathophysiological mechanisms, it has been ignored by clinical researchers because it does not mimic clinical CABG. Therefore, relatively fewer studies have investigated what happens when arterial mechanical stimulation is unloaded. Bayer et al. reported that reducing arterial wall tension using a cuff method leads to rapid and extensive atrophy of the arterial media, and Zhang et al. demonstrated that atherosclerosis did not occur in arteries grafted into veins in cholesterol-fed rabbits; however, the artery grafts were atrophied and remodeled8,9. This atrophy and remodeling of the arteries is closely related to the apoptosis of VSMCs9. Previous studies have shown that inducing vascular atrophy and VSMCs apoptosis may be a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of cardiovascular disease with intimal hyperplasia10. However, the molecular mechanism underlying the vascular atrophy and VSMCs apoptosis have not been deeply studied.

Recent studies have shown that VSMCs in the intimal hyperplasia stage are resistant to apoptosis11. Changes in hemodynamics affect the interaction of vascular wall tension and extracellular matrix, and it may be these changes that alter the survival characteristics of VSMCs12. Thrombospondin-4 (THBS4) is a secreted extracellular matrix protein that regulates cell behavior by binding to various cell surface molecules13,14. THBS4 is basically not expressed in adult tissues. However, its expression is significantly increased during tissue remodeling and regeneration, such as in atherosclerotic lesions15,16,17. During AngII-induced hypertension, THBS4 expression reduces heart hypertrophy and cardiac inflammation18. However, in the aorta, a lack of THBS4 can lead to inflammation and arterial dissection. THBS4 inhibits endothelial cell (EC) proliferation by reducing focal adhesion13. THBS4 can change macrophage apoptosis19. However, the regulatory mechanism of THBS4 on VSMCs apoptosis remains unclear.

In this paper, we established an animal model of low pressure and low tension of the right common carotid artery (RCCA) grafted into the right external jugular vein (REJV) in New Zealand rabbits using a vascular anastomosis wheel. For the first time, gene transcriptome and proteomic analyses were performed on arterial grafts under the action of low pressure and low tension to identify the morphological and molecular changes of arterial grafts under the condition of reduced hemodynamics. Subsequently, iPathway Guide (IPG) analysis determined that targeting THBS4 may provide a new strategy for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases caused by intimal hyperplasia.

Results

Vascular morphological changes after transplanting RCCA into REJV

The animal model of low pressure and low stretch of vascular mechanics was established in New Zealand rabbits by the RCCA being inverted and grafted into the REJV with end-to-end anastomosis using a vascular anastomosis wheel (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1). The patency of the rabbits’ arterial grafts was measured using ultrasound at 1-, 7-, 14-, and 30-days post-operation. After transplantation of the RCCA to the REJV, the peak systolic blood flow velocity (PS) was significantly decreased at all time points after grafting compared to that in the control artery (p < 0.05). The vascular resistance changed from a high resistance vessel to a low resistance vessel, indicated by the resistive index (RI) values decreasing. The RI also differed significantly from that of the normal common carotid artery control sample at all time points (p < 0.05). The volumetric flow (VolFlow) measurements indicated that the RCCA also changed from a high-flow vessel to a low-flow vessel, and all values were significantly lower than that for the control artery (p < 0.05). Therefore, the results clearly indicate a change in vascular characteristics of the artery graft toward a low-resistance and low-flow vessel after grafting into a venous environment (Fig. 1B).

Surgical diagram and operation charts of the experimental model. (A) Schematic diagram of arterial transplantation in the New Zealand rabbits and ultrasound examination at different time points after operation. VAW: vascular anastomosis wheel. (B) Statistical results of PS, RI, and Vol flow of normal arteries and vessels on the 1st, 7th, 14th and 30th day after the carotid artery transplantation in the New Zealand rabbits. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. n = 3 or 4 rabbits. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Examination of the vessels at the histological level by H&E staining was revealed slight decrease in the intima-medial thickness of the arterial graft at day 3 post-operation. The intima-medial thickness decreased significantly on postoperative day 7 (P < 0.0001 vs. control and day 3), decreased sharply on day 30 (p = 0.0001 vs. day 7), and stabilized on day 30 (Fig. 2A and B). With prolonged postoperative time, the tunica media thinned gradually; however, the intima changed minimally. Immunofluorescence revealed decrease in the number of α-SMA-positive cells, shown as red fluorescence, in the tunica media of the arterial graft with time after grafting (Fig. 2C). The integrated optical density results showed that at 7 days, 14 days, and 30 days after the operation, the expression of α-SMA in the postoperative groups was significantly lower than that in the normal artery group (p < 0.0001 vs. artery), and there was no significant difference between the 14-day postoperative group and the normal vein group, as well as between the 30-day postoperative group and the normal vein group (Fig. 2D). After counting the nuclei in the intima and media of blood vessels, the results indicated that there were significant differences between the 7-day, 14-day, and 30-day postoperative groups and the normal artery group (p < 0.0001 vs. the artery group). In contrast, there were no significant differences between the 14-day and 30-day postoperative groups and the normal vein group (Fig. 2E). Higher magnification examination of the arterial grafts by TEM revealed consistent results. Seven days post-operation, the myofilaments within the cells and the contractile bodies related to contraction decreased. (Fig. 2F). However, the cytoplasm was filled with many organelles associated with synthesis, such as the rough endoplasmic reticulum, ribosomes, and mitochondria. This suggested that the VSMCs underwent a phenotypic switch into a synthetic phenotype. In addition, many lipid droplets were deposited in the cytoplasm, and a large number of lysosomes appeared. On day 14, the amount of ribosomes, rough endoplasmic reticulum, lysosomes, mitochondria, and deposition of lipid droplets in the VSMCs decreased. Additionally, breakages occurred in the elastic plate. The synthetic VSMCs gradually were inhibited at 30 days after grafting to prevent excessive vascular repair (Fig. 2F).

Changes in arterial graft after RCCA transplantation into REJV. (A) Representative H&E staining of normal arteries and veins at 3, 7, 14, and 30 days post-operation. Upper panel: The scale bar is 100 µm, at ×10; below panel: The scale bar is 50 µm, at ×40. (B) Intima-media thickness plots at 3, 7, 14, and 30 days after transplantation. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and measured by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons, n = 3 rabbits, two to six different visual fields were repeated per rabbit. ***p < 0.001. (C) Representative immunofluorescence images of arterial and venous sections stained with α-SMA (red) and DAPI (blue) at 3, 7, 14, and 30 days post-grafting of the artery (RCCA) into the vein (REJV). Scale bars: 75 µm. (D) Integrated optical density histogram of normal arteries and veins at 3, 7, 14, and 30 days post-operation. n = 3 rabbits, two to six different visual fields were repeated per rabbit. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and measured by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. ***p < 0.0001 compared to artery; ###p < 0.0001 compared to vein. (E) Number of cell nuclei histogram of normal arteries and veins at 3, 7, 14, and 30 days post-operation. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 4) and measured by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. ***p < 0.0001 compared to artery; ###p < 0.0001 and ##p < 0.001 compared to vein. (F) TEM images of the arterial grafts at 3, 7, 14, and 30 days post-operation. Black boxes indicate areas viewed in magnification. Blue arrows indicate rough endoplasmic reticulum and ribosomes; Red arrows indicate lysosomes; Green arrows indicate mitochondria; Yellow arrows indicate lipid droplets. Scale bars: 10 µm; scale bar of the magnified image: 1 µm. (G) Arterial grafts at 3, 7, 14, and 30 days post-operation were stained with FITC-dUTP and analyzed using the TUNEL assay. Scale bars: 50 µm; scale bar of the magnified image: 7.5 µm. (H) TUNEL fluorescence area comparison at 3, 7, 14, and 30 days post-operation. n = 3 rabbits, two to six different visual fields were repeated per rabbit. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and measured by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. ***p < 0.001.

We next performed TUNEL experiments to investigate whether the decrease in the number of VSMCs in the tunica media of the grafts was due to apoptosis. The TUNEL assay revealed severe vascular medial cell apoptosis, starting from the proximal lateral to the medial side (Fig. 2G). In addition, immunofluorescence using TUNEL assay revealed that the highest number of stained cells was at seven days after grafting but apoptosis was over by 30 days or earlier post-grafting (Fig. 2G and H).

Gene expression profilings in arterial grafts reveal changes in THBS4 and focal adhesion pathways

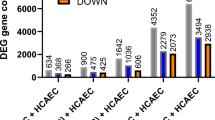

Gene expression profiling was then undertaken to reveal potential signaling pathways involved in the changes in the RCCA after grafting into the REJV. For this analysis, arterial grafts (T) and contralateral artery controls (C) were harvested 14 days after transplantation. The harvested tissues were first analyzed using high-throughput sequencing. The DEGs between the two groups are shown in volcano maps (Supplementary Fig. 2A). We observed that 2,999 genes were upregulated, whereas 2,029 genes were downregulated in T compared with C. Transcriptome differences in the top 100 upregulated genes were evident in the T and C circular heat maps of the DEGs (Fig. 3A). Notably, one of the top 100 upregulated genes was THBS4 that encodes the THBS4 extracellular matrix protein (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Table 1). KEGG and GO analyses were then performed to reveal the pathways and biological systems that the DEGs were involved in. KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that focal adhesion pathways were among the top 20 enriched KEGG pathways of the downregulated DEGs (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the genes PARVA, VCL, MYLK, ITGB5, and BCL2, which are involved in the regulation of apoptosis in the focal adhesion pathway, were all significantly downregulated (Supplementary Fig. 2A). GO enrichment analysis revealed that cell–matrix adhesion and cell-substrate adhesion were among the top 20 enriched GO terms for the downregulated DEGs (Supplementary Fig. 2C). Therefore, these results suggest that THBS4 and focal adhesion pathways are involved in arterial graft remodeling, and the mechanism involves apoptosis.

High-throughput detection results after arterial grafting. (A) Heatmap of the top 100 upregulated differentially expressed genes in arterial grafts 14 days post-grafting. "C" represents the contralateral control group. “T” represents the experimental group 14 days after the surgery. (B) Heatmap of the top 150 differentially expressed proteins of arterial graft remodeling 30 days post-operation. "C" represents the contralateral control group. “T” represents the experimental group 30 days after the surgery. (C) THBS4 protein expression was detected via immunohistochemistry at 3, 7, 14, and 30 days post-operation. Neg represents the control group without adding the primary antibody. Red arrows indicate THBS4 protein expression in the cytoplasm and nucleus. Scale bars: 20 µm. (D) Comparison of the average optical density of immunohistochemical staining for THBS4 between groups. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and measured by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons (n = 4). *p < 0.0001 compared to 7 days post-operation.

Proteomic profiling of arterial graft remodeling

To validate the pathways identified by the gene expression profiling, proteomic profiling of the arterial remodeling was then undertaken on two sample groups; the experimental group (T) included three samples of RCCAs 30 days after grafting, and the control group (C) included three samples of contralateral arteries. After screening, 6,057 proteins were quantified. Differentially expressed proteins were screened for each sample group, and 643 DEGs were identified: 382 proteins were upregulated and 261 were downregulated in T compared with C (Supplementary Fig. 3A). The top 150 upregulated proteins are illustrated in Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table 2. This result revealed that THBS4 protein expression was high, with a 4.18-fold increase compared to that in the control samples (Supplementary Table 2). Functional enrichment analysis of the downregulated proteins is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3B and C, revealing significant differences in the focal adhesion pathway. Moreover, in the focal adhesion pathway, the expression levels of proteins related to apoptosis, such as VCL, MYLK, PARVA, ITGB5, and ITGA9 were all decreased (Supplementary Fig. 3A). This result suggests that THBS4 is increased at the protein level alongside decreased levels of proteins in the focal adhesion pathway, validating the RNA results above. This implies that THBS4 and focal adhesion pathways are essential in vascular remodeling.

The expression pattern of THBS4 protein was investigated through immunohistochemistry. The immunohistochemical results revealed that THBS4 was expressed in the cytoplasm and nucleus on days 3 and 7 post-operation in the grafted RCCA (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the expression of THBS4 was significantly higher at 7 days post-operation compared to that at 3 days, 14 days, and 30 days (p < 0.0001 vs. 7 days post-operation), see Fig. 3D. Moreover, the location of THBS4 expressed shift from the outside to the inside of the tunica media over time (Fig. 3C).

THBS4 promotes HASMCs apoptosis

To investigate the effect of THBS4, we subsequently investigated overexpression and silencing of THBS4 in HASMCs. The transfection efficiency was verified using Rt-qPCR to measure the level of mRNA and is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 4 (p < 0.05). The results showed that compared with the empty plasmid group (Neg), the THBS4 mRNA level in the OV-THBS4 group was significantly increased (P < 0.0001), indicating that OV-THBS4 can efficiently mediate the overexpression of THBS4 and can be used for subsequent functional studies. Three siRNA sequences (Si1, Si2, Si3) targeting distinct regions of the THBS4 transcript were transfected into cells to silence THBS4 expression. Quantitative RT-PCR confirmed significant THBS4 knockdown in all siRNA groups compared to the non-targeting siRNA control (Neg). The expression of THBS4 in the Si1 sequence group was significantly reduced (P = 0.0204). Based on these results, Si1 was selected for the subsequent functional experiments.

Flow cytometry analysis was performed 48 h after transfection to investigate apoptosis and the cell cycle (Fig. 4). 7AAD/APC double staining (Fig. 4A–D) revealed a dramatic increase in apoptosis (47.4 ± 6.4%) with OV-THBS4 than compared with that in the negative control (8.9 ± 2.7%). In contrast, no notable change was observed with Si-THBS4. Thus, this result showed that OV-THBS4 promotes apoptosis in HASMCs.

Cell apoptosis and cycle arrest were induced in HASMCs by overexpressed THBS4. (A) Cell apoptosis analysis of HASMCs after THBS4 overexpression for 48 h was detected via flow cytometry analysis using Annexin V-APC and 7-AAD double staining. HASMCs are presented in a scatter plot where the upper left quadrant (Q1) identifies naked nucleated cells (7-AAD+/APC-), the upper right quadrant (Q2) identifies late apoptotic cells (7-AAD+/APC+), the lower left quadrant (Q3) identifies live cells (7-AAD−/APC−), and the lower right quadrant (Q4) identifies early apoptotic cells (7-AAD-/APC+). (B) Quantification of apoptotic cells by THBS4 overexpression. The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated. Apoptosis rate = the upper right quadrant (Q2) + the lower right quadrant (Q4). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed by unpaired T-test. n = 3 experiments, **p < 0.01. (C) Cell apoptosis analysis of HASMCs after THBS4 silencing for 48 h was detected via flow cytometry analysis using Annexin V-APC and 7-AAD double staining. (D) Quantification of apoptotic cells by THBS4 silencing. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed by unpaired T-test. n = 3 experiments, ns = non-significant. (E) Changes in the cell cycle of HASMCs owing to overexpressed THBS4 for 48 h. (F) Percentages of different cell cycles in HASMCs after THBS4 was overexpressed. Percentage of cells in the S phase increased significantly. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed by unpaired T-test. n = 3 experiments, **p < 0.01. (G) Changes in the cell cycles of HASMCs owing to silenced THBS4 for 48 h. (H) Percentages of different cell cycles in HASMCs after silencing THBS4. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed by unpaired T-test. n = 3 experiments, ns = non-significant.

Meanwhile, Cell cycle perturbation was assessed using single PI staining and is illustrated in Fig. 4E–H. The negative control and OV-THBS4 groups had 81.6 ± 3.0% and 55.0 ± 5.5% cells in G0/G1 phase, and 13.2 ± 2.7% and 37.7 ± 6.8% cells in the S phase, respectively (Fig. 4E and F). Thus, OV-THBS4 treatment significantly decreased the number of HASMCs in the G0/G1 phase and elevated the number of those in the S phase. However, this was not observed with Si-THBS4 treatment (Fig. 4G and H). These results suggest that OV-THBS4 interferes with the cell cycle of HASMCs and influences cell proliferation.

Overall, the results suggest that THBS4 not only promotes apoptosis, but also induces proliferation. The dual effect of promoting both cell apoptosis and cell proliferation will be investigated in detail in the subsequent experiments to understand how it affects the overall balance of VSMCs in vascular tissues.

Low stretch stress promoted the expression of THBS4 and apoptosis of HASMCs

Under normal blood pressure conditions, the maximum stretching deformation of human aorta is 9–12%. Therefore, in the cell experiment of this part, we chose to exert low stretching force of 5% and normal physiological stretching force of 10% in vitro, while exerting high stretching force of 15% on HASMCs. After subjecting HASMCs to low stretching force (5%), normal physiological stretching force (10%), and high stretching force (15%) for 12 h continuously using the Flexcell 5000 mechanical loading system in vitro, we collected the cells. The expression of THBS4 in cells under different stretch stress was detected by RT-qPCR and western blot, while the apoptosis of cells was detected by the Annexin V-APC and 7-AAD dual staining apoptosis detection kit. The results are shown in Fig. 5.

THBS4 expression and apoptosis in VSMCs under different intensities of mechanical stretch. (A) THBS4 gene expression at stretch deformation 0,5,10 and 15%. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and measured by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. n = 3 experiments, p < 0.05, significant difference, #compared to stretch deformation 5%. (B) Quantification of THBS4 protein in HASMCs at stretch deformation 0, 5, 10 and 15%. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and measured by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. n = 3 experiments, p < 0.05, significant difference, ⊙compared to stretch deformation 15%. (C) The levels of THBS4 in HASMCs were detected by western blotting undert stretch deformation of 0, 5, 10 and 15%. The original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 15. (D) Apoptosis analysis of HASMCs at stretch deformation 0,5,10 and 15% was detected via flow cytometry analysis using Annexin V-APC and 7-AAD double staining. (E) Quantification of apoptotic cells by different stretch deformation. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons, n = 3 experiments, p < 0.05, significant difference, *compared to stretch deformation 0%, #compared to stretch deformation 5%.

The RT-qPCR results indicated a decrease in THBS4 gene expression with increasing stretch stress. Notably, the THBS4 gene expression at 5% stretch was significantly higher than that at 15% stretch (Fig. 5A). Similarly, the expression of THBS4 protein at 5% stretching deformation exhibited a significantly higher level compared to that at 15%, consistent with the gene expression results (Fig. 5B and C).

From the Fig. 5D and E, it is evident that the apoptosis rate of HASMCs in static culture is 24.81%, 47.1% at 5% stretch, 39.8% at 10% stretch, and 34.6% at 15% stretch. The apoptosis rate in the experimental group exceeded that in the control group (static culture), with a gradual decrease observed in the experimental group’s apoptosis rate as stretch stress increased; notably, the apoptosis rate was significantly higher in the 5% stretching group compared to the 15% stretching group.

THBS4 interaction with PAK1 via focal adhesion pathway modulates VSMCs apoptosis

The DEG data were then used to perform iPathway Guide (IPG) analysis. The topology of the focal adhesion pathway, consisting of genes and their directional interactions, is illustrated in Fig. 6A. This highlighted genes of interest, which were related to cellular components. THBS4 and PAK1 gene were in the focal adhesion pathway and mechanisms linking the proteins to apoptosis were identified (Fig. 6B). Of particular interest was the suggestion in the analysis that PAK1 could directly regulate apoptosis.

THBS4 regulates VSMCs apoptosis, interacting with the focal adhesion pathway. (A) IPG analysis of the perturbation of the focal adhesion pathway. Blue indicates downregulated genes; Red indicates upregulated genes. Pathway analysis was performed using KEGG database53,55. (B) The molecular mechanisms related to the apoptotic process may be regulated in the focal adhesion pathways. Blue indicates downregulated genes; Red indicates upregulated genes. (C) p-PAK1 expression after transfection with THBS4 for 72 h. p-PAK1 expression was upregulated after THBS4 was overexpressed on the left. On the right, p-PAK1 expression was inhibited after small RNA interfered with THBS4. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and analzsed by paired T-test. n = 6 experiments, *p < 0.05. The original blots are presented in Supplementary Figs. 16 and 17.

Identification of PAK1 gene in the IPG analysis led us to speculate that THBS4 helps regulate focal adhesion interaction with PAK1. We investigated PAK1 activation in cells overexpressing THBS4 and those in which THBS4 silenced. Western blot analysis revealed that OV-THBS4 had significantly increased active p-PAK1 levels (p = 0.0017), whereas Si-THBS4 had significantly decreased active p-PAK1 levels (p = 0.0065) (Fig. 6C).

Quality control analyses of the above experiments are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5–14.

Discussion

Studying the changes that occur when arteries are grafted into veins is essential, as this could affect the success of surgical interventions and the long-term patency of grafts. Understanding the biological and pathophysiological mechanisms involved in arterial grafting could help identify potential therapeutic targets for improving vein graft success and reducing the risk of graft failure due to restenosis or atherosclerosis20. Furthermore, such studies could help develop new surgical approaches for treating vascular diseases. Therefore, continuously investigating the changes that occur during arterial grafting mechanical unloading and identifying potential targets for intervention are essential.

Investigations in the rabbit model revealed that the vessel walls thinned over time post-grafting; this is because of the VSMC apoptosis caused by decreased pressure, and low blood flow8,9. Clear evidence of decreased blood flow volume and velocity and decreased resistance in the grafted vessels was observed with ultrasound analysis. It has previously been demonstrated that reduced blood flow can enhance VSMC apoptosis, whereas hypertension onset and reversal can also upregulate apoptosis in VSMCs21,22. In the quantitative analysis of the immunofluorescence results of our experiment, it was found that apoptosis occurred in the transplanted vessel walls. The thinning of the vessel walls was mainly caused by the apoptosis of VSMCs, and the peak of apoptosis occurred around 7 days after transplantation (Fig. 2D and E). However, by 14 days after transplantation, the extracellular matrix of the cells in the transplanted vessels had become similar to that of veins, and by 30 days after transplantation, the apoptotic process of the cells had ended. Studies have shown that in the intimal hyperplasia model, the thickening of the neointima becomes significant after 14 days of injury, and is in the stage of tissue remodeling23. Consistent with this, in our experimental model, the vessel wall had thinned significantly by 14 days after transplantation, approaching the thickness of a venous wall, suggesting that the vessel was in the remodeling recovery phase at this time (see Fig. 1A–E). Notably, no cellular aggregation was observed in TUNEL assay, confirming that apoptosis occurred at a single cell level, consistent with previous research findings24.

Multiple pathways including SAPK/JNK, rac-p38MAPK, Rho-GDIα, Akt, Fas/FasL, and Hippo-YAP might be involved in regulating VSMC apoptosis9. However, whether these pathways are involved in the therapeutic mechanisms of arterial grafting in CABG and whether they have a role in atherosclerosis need to be further explored. To reveal the mechanisms involved in the transition of the arterial grafts in this study, transcriptome and proteome analyses were undertaken; based on the previous research23,25 and the changes in vascular morphology observed in our experiments, transcriptome analysis was conducted 14 days after the surgery, and proteomic analysis was carried out 30 days after the surgery. The results showed that the THBS4 gene and protein were significantly upregulated, and were enriched in the focal adhesion pathway which was significantly downregulated. Moreover, extracellular matrix can regulate the focal adhesion pathway. This indicates that the remodeling of arterial grafts is related to focal adhesions pathway, and this remodeling may be modulated by the extracellular matrix protein THBS4. The transcriptome analysis results showed that the expression of THBS4 was significantly upregulated, with a fold change of 7.76938 (see Supplementary Table 1). In the intimal hyperplasia model, THBS4 expression was significantly increased five days after injury and decreased two weeks after injury23. The reason for this difference might be due to the different mechanical environments of the two models. Our research focus is on the remodeling of arteries after mechanical unloading. In the intimal hyperplasia model, THBS4 mainly plays a role in activating the proliferation of VSMC and recruiting inflammatory cells23. In our experiment, THBS4 might mainly play an important role in regulating the apoptosis of VSMC in arteries after mechanical unloading. Stenina et al. first reported that THBS4 was expressed in VSMCs13. THBS4 can interfere with focal adhesion, resulting in changes in cell shape, suggesting that it regulates cell–matrix interactions and influences cell function26.

The IPG analysis in this study suggested that THBS4 regulates VSMC apoptosis via ITGA6-FAK-PI3K-RAC-PAK1 signaling. However, only THBS4 upregulation was detected in the protein analysis group, which indicates that THBS4-induced apoptosis occurred at the transcriptional level. THBS4 secretion by bovine aortic endothelial cells reduces focal adhesion26. In vascular cells, focal adhesion decreases, leading to their failure to proliferate13. Furthermore, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) can induce THBS synthesis and secretion in VSMCs15. Therefore, if we consider this alongside our results, we can speculate that changes in mechanical stress stimulate the upregulation of FGF23 and PDGFB in VSMCs, thereby regulating THBS4 secretion by VSMCs. The secreted THBS4 might interact with integrins and activate PAK1 in the downstream pathway, which eventually activates p53 and regulates VSMC apoptosis. Our immunohistochemical analysis revealed that THBS4 was expressed in the cytoplasm and nuclei of VSMCs following arterial transplantation. Therefore, we might have identified a novel function of THBS4 in regulating VSMC apoptosis. However, this will need further in-depth investigations.

Overexpression of THBS4 increased apoptosis dramatically, whereas there was no effect from THBS4 silencing; this might be because THBS4 is expressed at a low level in normal cells, and its expression is only switched on during events such as tissue remodeling18,19. THBS4 overexpression also arrested HASMCs in the S phase, indicating that they could not proliferate. Some studies have uncovered that external stimuli, such as mechanical stress, injury, or inflammation, can arrest or block the growth cycle of VSMCs, consistent with our results21,27. Thus, THBS4 might also halt HASMC proliferation as well as apoptosis. We speculate that THBS4 regulates apoptosis through the focal adhesion pathway and overexpression of THBS4 upregulates PAK1 expression in HASMCs. PAK1 is a target protein for the small GTPases- cell division cycle 42 (Cdc42) and Rac28 PAK1 reduces endothelial progenitor cell proliferation by downregulating the c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway, thus, exhibiting antiangiogenic characteristics28. PAK is located upstream in the JNK pathway; therefore, it might be involved in the JNK signaling cascade and apoptosis29,30 PAK1 is a potential mediator of Rac/Cdc42 signaling, and studies have observed PAK1 stimulating p38 activity31. Furthermore, PAK1 can cause anti-cardiac hypertrophy32. Therefore, PAK1 is key in linking extracellular signals from membrane components to nuclear reactions, such as transcription activation33. Benzo[a]pyrene induces apoptosis by activating the Cdc42/Rac1-PAK1-SEK1-JNK1 signaling pathway34. Our results indicate that THBS4 regulates apoptosis in HASMCs by activating the ITGA6-PI3K-VAV-RAC-PAK1-p38MAPK-p53 signaling pathway.

Grafting arteries into veins does not usually result in arteriosclerosis or intimal hyperplasia9. Based on the findings of this study, this might be attributed to the high expression of THBS4, which is crucial in PAK1 upregulation and, subsequently, p53, leading to VSMC apoptosis. It is inconsistent with the fact that THBS4 can reportedly promote the proliferation of HASMCs13. Through comparison, the molecular weight of the THBS4 fragment studied by Stamina et al. was 74 kDa, whereas that of the THBS4 fragment in our experiment was 135 kDa13. In addition, THBS4 has a complex multi-domain structure, which can be cut into different fragments by various molecules, such as MMP9, and different fragments will have different functions when combined with different proteins13,35. How the fragments work has not been studied in detail. This study sheds light on the important role of THBS4 in VSMC apoptosis, and more studies are required to explore the potential benefits of THBS4-related strategies aimed at positively influencing neointimal remodeling following injury.

Additionally, we observed apoptosis in HASMCs and variations in THBS4 expression under different stretch deformation. Specifically, HASMCs apoptosis were significantly higher at 5% hypo-stretch deformation compared to 15% stretch deformation. These findings align with previous studies suggesting that a 10% stretch promotes cell apoptosis while a 15% stretch reduces it36. Furthermore, exposure of VSMCs to less than 10% stretch has been shown to increase apoptosis in mice37. Notably, under 5% stretch deformation, it was observed that THBS4 gene and protein were significantly overexpressed in HASMCs, which was consistent with the observed apoptosis trend. This study represents the first investigation on the expression changes in THBS4 under different stretching conditions, indicating that THBS4 may regulate apoptosis induced by low-level stretch deformation.

THBS4 may simultaneously exert different effects on distinct cell populations. For instance, it has been shown to promote apoptosis in macrophages via specific integrin receptors19, while in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), it can initially stimulate proliferation and migration23. This dual signaling within the tissue milieu collectively drives structured remodeling. Our transcriptional data (showing upregulation of macrophage markers CD68 and CSF1R) and ultrastructural evidence (showing VSMC phenotype transformation) suggest that THBS4 may promote the transition of VSMCs into a macrophage-like phenotype38. Subsequently, THBS4 could then facilitate the apoptosis of these transformed cells once their role in the remodeling process is complete. This sequence of events effectively resolves the paradox, as THBS4 first contributes to a change in cell fate (interpreted as 'pro-proliferative’ in some contexts) and later mediates the clearance of the same cell lineage. The expression of THBS4 in our in vitro HASMC model confirms its ability to exert direct and sustained regulatory effects on these cells. Its unique domain structure (e.g., integrin-binding RGD motifs not present in THBS113) allows for diverse receptor interactions, underpinning its pleiotropic functions. Therefore, the dual role of THBS4 is not contradictory but rather reflects its sophisticated mechanism as a key regulator coordinating different phases of vascular adaptation, particularly in our model of mechanical unloading.

We have considered the potential limitations of our study. The results obtained using an animal model might not be directly translated into clinical settings; therefore, the role of THBS4 in improving patency of grafts in CABG will need to be investigated using other approaches. Our transcriptome and proteome analyses suggested pathways that could be involved in apoptosis of VSMCs during adaptation of vessels to grafting. However, these pathways will need further detailed investigation at the molecular level, and we plan to address them in our next study. The findings have major implications for the development of novel treatments for arterial injuries and related conditions.

Materials and methods

Animals and experimental design

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the School of Biological Science and Medical Engineering, Beihang University (Approval number: 2022210). All animal experiments include planned experimental design, statistical considerations, procedures (including the administration of potassium chloride for the purpose of euthanasia) and outcomes and are in full accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including those outlined by the approving committee. New Zealand white rabbits were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of Peking University Health Science Centre (Beijing, China; Production License No. SYXK- Jing-2023-0031) and maintained under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions with controlled temperature (23 ± 1℃) and 12-h light/dark cycles.

Thirty-three male New Zealand large white rabbits, 10 months old, 3.5–4 kg were selected randomly for arterial graft modeling where the RCCA was transplanted into the REJV. Each graft was harvested under general anesthesia on postoperative days 3, 7, 14, and 30. All rabbits were euthanized by injecting with potassium chloride (0.5 mL/kg) while still under anesthesia. Six rabbits were sampled at each time point for transcriptome analysis. Three of the rabbits in each group were used for pathological analysis. The remaining three rabbits were subjected to proteomic analysis at 30 days after surgery. Self-contralateral arteries were harvested as controls.

Surgical procedure

Anesthesia was induced via an intramuscular propofol injection (2.5 mg/kg). Tracheal intubation was performed, anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane and oxygen, and the animal was autonomously ventilated.

An incision was made in the middle of the neck of each rabbit—layer-by-layer, the skin and muscles were separated, and the trachea was exposed. On either side of the trachea were the left and right common carotid arteries and the external jugular veins (EJV). Simultaneously, heparin sodium (50 U/kg) was intravenously injected to induce heparinization. A few drops of papaverine were administered into the RCCA. The RCCA segment, approximately 2 cm long, was separated, excised, turned over between vascular clamps, and anastomosed end-to-end with the EJV using the vascular anastomosis wheel. Suture the muscles and skin layer by layer.

One day after the operation and one day before sample collection, the vascular patency was examined using an 8—14 MHz linear array probe of the ultrasound (Logiq 9, GE, USA). The changes in maximum blood flow velocity PS, resistance index RI and blood flow volume VolFlow were also measured.

Morphology

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The grafts were fixed in 10% formalin at 4 ℃ for 4 h and then cut into 4-μm thick sections using paraffin embedding. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The rest were dewaxed with xylene, hydrated with ethanol, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with a 1:50 dilution of THBS4 primary antibody (SC-28293, Santa Cruz). The slides were rinsed thrice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min each time. The slides were stained with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB, ZLI-9017, ZSGB-Bio) and hematoxylin (Sigma). After dehydration and transparency, images were obtained using a microscope (Olympus IX71). H&E staining was scanned using PRECICE500B fully automatic digital slice scanning system (Unic Technologies, Beijing). The resulting digital images were analyzed using iViewer software (Unic Technologies, Beijing). The contours of the internal and external elastic laminae were manually delineated by pathologists in a blinded manner at 40× magnification. The intima-media thickness was then automatically calculated by the iViewer measurement tool as the average perpendicular distance between the two defined boundaries at multiple equidistant points around the vascular circumference. This measurement method is consistent with that described in previous studies.39 For each sample, two to seven fields of view were analyzed, and a total of four independent samples were investigated per group.

Immunofluorescence staining

The grafts were embedded in optimum cutting temperature compound and cut into 4-μm thick frozen sections. Immunofluorescence (IF) staining was performed. Sections were incubated with alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA, 1:400, A2547, Sigma) and THBS4 (1:50, SC-28293, Santa Cruz) overnight at 4 °C, followed by the addition of a secondary antibody. Nuclei were stained with 4ʹ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, S2110, Solarbio). Immunofluorescence was observed using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica SP5, Germany).

TUNEL assay (KeyGen BioTech) was used to assess apoptosis according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Paraffin sections were fixed using a microwave antigen in sodium citrate-hydrochloric acid buffer for 8 min. The slices were rinsed with PBS thrice, placed in terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) reaction solution in a humid and dark oven at 37 ℃ for 1 h, and rinsed with PBS thrice. Staining with streptavidin-fluorescein was also performed for 30 min in a humid and dark oven at 37 ℃. The cells were then washed thrice with PBS. The nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The sections were observed using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica SP5, Germany). TUNEL staining was quantified using Image J (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Two to seven fields of view were for isolated for each sample, and a total of 4 samples were counted per field of view.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

At 4 ℃, the graft was fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2–3 h, washed with 0.1 M phosphate buffer, fixed with 1% osmotic acid for 1.5 h in the dark, washed with ultrapure water, and dehydrated with a series of acetone concentrations (50%, 70%, 90%, 96%, and 100%) for 5 min each time. The graft was then embedded in Epon 812 and polymerized at 60 ℃ for 48 h. Using a UC 7 microtome (Leica Microsystems), ultra-thin slices with 60 nm thickness were obtained. The slices were stained with 2% uranyl acetate and lead citrate for 25 and 7 min, respectively. Slices were collected on a 200-mesh grid, and images were obtained at 80 kV using TEM (Hitachi, HT-7800, Tokyo, Japan).

Gene transcriptome analysis

After disrupting the tissues using liquid nitrogen, RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) as described previously40 and according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA purification, reverse transcription, library construction, and sequencing were performed by Majorbio Bio-pharm Biotechnology Ltd., Shanghai, according to the Illumina (San Diego, CA) kit instructions. The RNA-seq transcriptome librariy was prepared following Illumina® Stranded mRNA Prep, Ligation (San Diego, CA) using 1ug of total RNA. Shortly, messenger RNA was isolated according to polyA selection method by oligo (dT) beads and then fragmented by fragmentation buffer firstly. Secondly double-stranded cDNA was synthesized with random hexamer primers. Then the synthesized cDNA was subjected to end-repair, phosphorylation and adapter addition according to library construction protocol. Libraries were size selected for cDNA target fragments of 300-400bp use magnetic beads followed by PCR amplified for 10–15 PCR cycles. After quantified by Qubit 4.0, the sequencing library was performed on NovaSeq X Plus platform (PE150) using NovaSeq Reagent Kit.

Gene expression data used in this study were obtained from the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencing platform. The reference rabbit genome was obtained from the Ensembl database (http://asia.ensembl.org/Oryctolagus_cuniculus/Info/Index). We compared the 14-day grafted RCCA with the control contralateral artery as we considered this the ideal timepoint for identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) related to arterial transplantation. Sequence alignment and analysis were conducted using HISAT2 (http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/hisat2/index.shtml). Plot reading of each sample was performed using StringTie (https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/stringtie/).

Differential expression was analyzed using DESeq241/DEGseq42/edger43/Limma44/NOIseq45, with |log2 (fold change)|≥ 1 and P-adjust ≤ 0.05 (DESeq2/edgeR/Limma)/p-adjust ≤ 0.001 (DEGseq)/Prob > 0.8 (NOIseq) considered significant DEGs. Functional enrichment analysis, including GO (Gene Ontology, http://www.Geneontology.Org/) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, http://www.genome.jp/kegg/), was used to determine the DEGs with significant GO terms and metabolic pathways when compared with the whole-transcriptome background. Goatools (https://github.com/tanghaibao/Goatools) and KOBAS (http://kobas.cbi.pku.edu.cn/home.do) were used for the GO functional enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses46.

Proteome analysis

For proteome analysis, 30-day post-graft RCCA and contralateral-artery control samples were selected, each with at least three biological replicates. We extracted proteins and hydrolyzed them into peptides using the enzyme as described previously47. In the library generated via data dependent acquisition (DDA), all six samples were pooled into a mixture, and eight fractions were obtained via high pH separation. Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) was performed for all six samples to evaluate the differences between protein groups. Simultaneously, data from MS 1 and MS 2 level peptides were collected, and samples were randomly collected. All samples were added to an iRT kit (Ki3002; Biognosys AG, Switzerland) to calibrate the retention times of the extracted peptide peaks. The DIA dataset was statistically analyzed using Spectronaut 13 (Biognosys AG, Switzerland), including data standardization and relative protein quantification. After Welch’s analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, differentially expressed proteins were filtered out if the p-value was < 0.05 and the fold change was > 2.

Cell culture and transfection

HASMCs were obtained from CHI Scientific and maintained in a medium of 37 ℃ under 5% CO2. HASMCs were grown in DMEM/F12 (Gibco) supplemented with 1 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) and 10% FBS (Gibco). Cells were transfected with (i) 2.5 μg plasmids (General Biol) or (ii) 50 nM siRNA (General Biol) using the Lipo 3000 transfection reagent (GK20006, GLPBio), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were harvested 48 h post-transfection for further testing.

The THBS4 plasmid was constructed by General Biotechnology Company by cloning the full-length human THBS4 gene (NCBI reference sequence: NM_003248). The siRNA targeting for THBS4 was designed and synthesized by General Biotechnology Company.

Flow cytometry analysis

The Annexin V-APC/7-AAD Apoptosis Kit (AP105, Multi Sciences) was used to study apoptosis. HASMCs were seeded overnight in six-well plates (105 cells/well) and transfected with Lipo 3000 plasmid DNA/siRNA targeting THBS4. After 48 h, floating and adherent cells were collected via centrifugation at 201 g for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the cells were gently resuspended by adding 500 μL of 1 × binding buffer. Afterward, 5 μL Annexin V-APC and 10 μL 7-AAD were added and mixed gently. After incubation in the dark at room temperature for 5 min, and 10,000 cells per sample were analyzed using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD FACSCanto™, USA).

A Cell Cycle Staining Kit (CCS012; Multi Sciences) was used for cell cycle analysis. The cells were collected, washed once with PBS, and centrifuged at 201 g for 5 min. The cells were resuspended in 1 mL of DNA staining solution and 10 µL of permeabilizing solution in the dark for 30 min. Then 10,000 cells per sample were analyzed using flow cytometry (BD FACSAria™ II, USA).

Mechanical stretching experiment

The HASMCs were seeded onto the BioFlex® Culture plate (BF-3001 C) coated with collagen type I at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well. After 12 h, the culture medium was replaced with fresh DMEM/F12, and cyclic stretching was performed using the FX-5000 T strain apparatus (FX 5000, flex cell, USA). The mechanical stretching had the amplitudes of 5%, 10% and 15%, and followed a sine wave pattern with a frequency of 1.0 Hz for a duration of 12 h.

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

RNA was extracted as described in Section "THBS4 promotes HASMCs apoptosis". The RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the ReScript™ II RT SuperMix for qPCR (+ gDNA Eraser) kit (R712-01, Nobelab, China). 2 × SYBR Premix UrTaq II (R601, Nobelab, China) was used to detect gene expression via RT-qPCR, and GAPDH was the internal control. The primer pairs are included in the supplementary material. All tests were performed thrice independently, and gene expression was normalized to GAPDH expression. Relative gene expression was calculated as fold changes using the 2-∆∆CT method.

Western blot analysis

Total protein from HASMCs was extracted using RIPA buffer (Solarbio) and a cocktail (GLPBio) at a ratio of 100:1. Protein concentrations were measured using a NanoDrop 2000/2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo, USA). Equal amounts (50 μg) of the total protein were separated using 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (Solarbio) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Subsequently, membranes were blocked with 5% non-lipid dry milk in TBST for 1 h, incubated overnight at 4 °C, and shaken with the primary antibodies to detect THBS4 (1:100, SC-28293, Santa Cruz), p-PAK1 (1:1000, ET1608-58, Huabio), and actin (1:5000, R1207-1, Huabio). The membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse (or rabbit) secondary detection antibody (Huabio, China). Immunoreactive proteins were detected using a chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Millipore) and visualized on the proteinsimple imaging platform (FluoChem R, US).

iPathway guide

The iPathway Guide (IPG) uses impact analysis to score pathways. The impact analysis method uses two types of evidence: i) DEG over-representation in a particular pathway and ii) perturbation calculations in the pathway topology using the expression changes measured for that pathway. The topological structures of the potential pathways composed of genes and their directional interactions were obtained from the KEGG database.

In this experiment, 54,541 genes were in the Advaita Knowledge Base (AKB), of which 3,957 DEGs were identified. These data have been used in previous studies48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55. We identified 281 important signal paths. We found 4,592 GO terms, 247 miRNAs, 469 gene upregulators, 809 chemical upregulators, and 239 diseases to be enriched through multiple comparative correlations.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated thrice. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Non-paired and paired t-test was used for two-sample statistical comparisons, whereas one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was used for more than two groups. A P-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request. Contact information: Yubo Fan at yubofan@buaa.edu.cn. To review GEO accession GSE289973: Go to https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE289973 Enter token uhqhwaoeptixpwd into the box. The proteomics data can be accessed via the website: https://www.iprox.cn/page/PSV023.html;?url=17471022778881G4I Enter the password VulQ to view.

Abbreviations

- AKT:

-

Protein kinase B

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- DAB:

-

3,3'-Diaminobenzidine

- DAPI:

-

4ʹ,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DDA:

-

Data dependent acquisition

- DEGs:

-

Differentially expressed genes

- DIA:

-

Data-independent acquisition

- EC:

-

Endothelial cell

- EJV:

-

External jugular veins

- ERK:

-

Mitogenactivated protein kinase

- FAK:

-

Focal adhesion kinase

- Fas/FasL:

-

Fas antigen/fas ligand

- FGF23:

-

Fibroblast growth factor 23

- bFGF:

-

Basic fibroblast growth factor

- HASMCs:

-

Human aortic smooth muscle cells

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin

- Hippo-YAP:

-

Hippo pathway Yes-associated protein

- IF:

-

Immunofluorescence

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- ITGA6:

-

Integrin alpha 6

- IPG:

-

IPathway guide

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinases

- MEK:

-

The mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- PAK1:

-

P21-activated kinase 1

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PDGF:

-

Platelet derived growth factor

- PI3K:

-

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PS:

-

Peak systolic blood flow velocity

- RAC:

-

Small Rho GTPases

- RCCA:

-

Right common carotid artery

- RI:

-

Resistive index

- REJV:

-

Right external jugular vein

- Rho-GDIα:

-

Rho guanine dissociation inhibitor α

- SAPK/JNK:

-

Stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

- TEM:

-

Transmission electron microscopy

- THBS4:

-

Thrombospondin-4

- VAW:

-

Vascular anastomosis wheels

- VolFlow:

-

Volumetric flow

- VSMCs:

-

Vascular smooth muscle cells

References

Head, S. J., Kieser, T. M., Falk, V., Huysmans, H. A. & Kappetein, A. P. Coronary artery bypass grafting: Part 1–the evolution over the first 50 years. Eur. Heart J. 34, 2862–2872. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht330 (2013).

Beerkens, F. J. et al. Contemporary coronary artery bypass graft surgery and subsequent percutaneous revascularization. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 19, 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-021-00612-6 (2022).

Desai, M., Seifalian, A. M. & Hamilton, G. Role of prosthetic conduits in coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. Off. J. Eur. Assoc. Cardio-thorac. Surg. 40, 394–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.11.050 (2011).

Wadey, K., Lopes, J., Bendeck, M. & George, S. Role of smooth muscle cells in coronary artery bypass grafting failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 114, 601–610. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvy021 (2018).

Gharibeh, L., Ferrari, G., Ouimet, M. & Grau, J. B. Conduits’ biology regulates the outcomes of coronary artery bypass grafting. JACC. Basic Transl. Sci. 6, 388–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.11.015 (2021).

Pauletto, P., Sartore, S. & Pessina, A. C. Smooth-muscle-cell proliferation and differentiation in neointima formation and vascular restenosis. Clin. Sci. 87, 467–479. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs0870467 (1994).

Chen, J., Zhou, Y., Liu, S. & Li, C. Biomechanical signal communication in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 14, 357–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12079-020-00576-1 (2020).

Bayer, I. M., Adamson, S. L. & Langille, B. L. Atrophic remodeling of the artery-cuffed artery. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19, 1499–1505. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.atv.19.6.1499 (1999).

Zhang, H. et al. Artery interposed to vein did not develop atherosclerosis and underwent atrophic remodeling in cholesterol-fed rabbits. Atherosclerosis 177, 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.06.019 (2004).

Min, S. K., Kenagy, R. D. & Clowes, A. W. Induction of vascular atrophy as a novel approach to treating restenosis. A review. J. Vasc. Surg. 47, 662–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2007.07.056 (2008).

Deuse, T. et al. Dichloroacetate prevents restenosis in preclinical animal models of vessel injury. Nature 509, 641–644. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13232 (2014).

Walsh, K., Smith, R. C. & Kim, H. S. Vascular cell apoptosis in remodeling, restenosis, and plaque rupture. Circ. Res. 87, 184–188. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.res.87.3.184 (2000).

Stenina, O. I. et al. Thrombospondin-4 and its variants: Expression and differential effects on endothelial cells. Circulation 108, 1514–1519. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000089085.76320.4E (2003).

Muppala, S. et al. The P387 thrombospondin-4 variant promotes accumulation of macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 34, 11529–11545. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201901434RRRR (2020).

Stenina-Adognravi, O. & Plow, E. F. Thrombospondin-4 in tissue remodeling. Matrix Biol. J. Int. Soc. Matrix Biol. 75–76, 300–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matbio.2017.11.006 (2019).

Yazman, S. et al. New biomarkers (endocan, interleukin-17, and thrombospondin-4) for the diagnosis, assessment of severity, and follow-up of peripheral arterial disease. Angiology 74, 631–639. https://doi.org/10.1177/00033197231166492 (2023).

Zierfuss, B. et al. Thrombospondin-4 increases with the severity of peripheral arterial disease and is associated with diabetes. Heart Vessels 35, 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-019-01453-7 (2020).

Palao, T. et al. Thrombospondin-4 mediates cardiovascular remodelling in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 35, 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carpath.2018.03.003 (2018).

Rahman, M. T. et al. Effects of thrombospondin-4 on pro-inflammatory phenotype differentiation and apoptosis in macrophages. Cell Death Dis. 11, 53. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-020-2237-2 (2020).

Spadaccio, C. et al. Preventing treatment failures in coronary artery disease: What can we learn from the biology of in-stent restenosis, vein graft failure, and internal thoracic arteries?. Cardiovasc. Res. 116, 505–519. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvz214 (2020).

Grootaert, M. O. J. & Bennett, M. R. Vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis: Time for a re-assessment. Cardiovasc. Res. 117, 2326–2339. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvab046 (2021).

Dong, Y. et al. Molecular machinery and interplay of apoptosis and autophagy in coronary heart disease. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 136, 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.09.001 (2019).

Rohl, S. et al. Transcriptomic profiling of experimental arterial injury reveals new mechanisms and temporal dynamics in vascular healing response. JVS Vasc. Sci. 1, 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvssci.2020.01.001 (2020).

Buus, C. L. et al. Smooth muscle cell changes during flow-related remodeling of rat mesenteric resistance arteries. Circ. Res. 89, 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1161/hh1401.093575 (2001).

Suna, G. et al. Extracellular matrix proteomics reveals interplay of aggrecan and aggrecanases in vascular remodeling of stented coronary arteries. Circulation 137, 166–183. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023381 (2018).

Sage, E. H. & Bornstein, P. Extracellular proteins that modulate cell-matrix interactions. SPARC, tenascin, and thrombospondin. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 14831–14834 (1991).

Li, G. et al. Identification of PI3K regulatory subunit p55gamma as a novel inhibitor of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointimal formation. Cardiovasc. Res. 105, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvu235 (2015).

Chistiakov, D. A., Sobenin, I. A., Orekhov, A. N. & Bobryshev, Y. V. Human miR-221/222 in physiological and atherosclerotic vascular remodeling. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 354517. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/354517 (2015).

Li, L. H. et al. p21-activated protein kinase 1 induces the invasion of gastric cancer cells through c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-mediated activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Oncol. Rep. 38, 193–200. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2017.5643 (2017).

Zhou, Y. et al. P21-activated kinase 1 mediates angiotensin II-induced differentiation of human atrial fibroblasts via the JNK/c-Jun pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 23, 207. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2021.11846 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Rho family GTPases regulate p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase through the downstream mediator Pak1. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 23934–23936. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.270.41.23934 (1995).

Wang, Y. et al. The p21-activated kinase 1 (Pak1) signalling pathway in cardiac disease: From mechanistic study to therapeutic exploration. Br. J. Pharmacol. 175, 1362–1374. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13872 (2018).

Perez-Yepez, E. A., Saldivar-Ceron, H. I., Villamar-Cruz, O., Perez-Plasencia, C. & Arias-Romero, L. E. p21 Activated kinase 1: Nuclear activity and its role during DNA damage repair. DNA Repair 65, 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2018.03.004 (2018).

Yoshii, S. et al. Involvement of alpha-PAK-interacting exchange factor in the PAK1-c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase 1 activation and apoptosis induced by benzo[a]pyrene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 6796–6807. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.21.20.6796-6807.2001 (2001).

Maly, K. et al. The expression of thrombospondin-4 correlates with disease severity in osteoarthritic knee cartilage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20020447 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Yes-associated protein reacts differently in vascular smooth muscle cells under different intensities of mechanical stretch. Aging 14, 286–296. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.203768 (2022).

Jensen, L. F., Bentzon, J. F. & Albarran-Juarez, J. The phenotypic responses of vascular smooth muscle cells exposed to mechanical cues. Cells 10, 2209. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10092209 (2021).

Wirka, R. C. et al. Atheroprotective roles of smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation and the TCF21 disease gene as revealed by single-cell analysis. Nat. Med. 25, 1280–1289. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0512-5 (2019).

Jiang, Q. et al. Nephrectomy and high-salt diet inducing pulmonary hypertension and kidney damage by increasing Ang II concentration in rats. Respir. Res. 25, 288. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-024-02916-w (2024).

Landolt, L., Marti, H. P., Beisland, C., Flatberg, A. & Eikrem, O. S. RNA extraction for RNA sequencing of archival renal tissues. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 76, 426–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365513.2016.1177660 (2016).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Wang, L., Feng, Z., Wang, X., Wang, X. & Zhang, X. DEGseq: An R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics 26, 136–138. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp612 (2010).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 (2010).

Smyth, G. K., Ritchie, M., Thorne, N., Wettenhall, J. & Shi, W. Limma: Linear models for microarray data. In Bioinformatics & Computational Biology Solutions Using R & Bioconductor (2010).

Tarazona, S., García, F., Ferrer, A., Dopazo, J. & Conesa, A. NOIseq: A RNA-seq differential expression method robust for sequencing depth biases. Univ. Southampt. 17, 18 (2012).

Xie, C. et al. KOBAS 2.0: A web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucl. Acids Res. 39, W316-322. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr483 (2011).

Yu, B. et al. iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomic analysis of thoracic aortas from adult rats born to preeclamptic dams. Clin. Proteomics 18, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12014-021-09327-9 (2021).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucl. Acids Res. 45, D362–D368. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw937 (2017).

Nam, J. W. et al. Global analyses of the effect of different cellular contexts on microRNA targeting. Mol. Cell 53, 1031–1043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.013 (2014).

Davis, A. P. et al. The comparative toxicogenomics database: Update 2019. Nucl. Acids Res. 47, D948–D954. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky868 (2019).

Agarwal, V., Bell, G. W., Nam, J. W. & Bartel, D. P. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife 4, e05005. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.05005 (2015).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The gene ontology consortium. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/75556 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucl. Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Kawashima, S. & Nakaya, A. The KEGG databases at GenomeNet. Nucl. Acids Res. 30, 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/30.1.42 (2002).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucl. Acids Res. 53, D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Yan Jinqiang, Department of Pathology, Liaocheng People`s Hospital, Shandong Province, for sectioning paraffin and frozen samples; Shi Miao, Department of Ultrasound, Liaocheng People`s Hospital, Shandong, for help with the ultrasonic examination; Chen Chao from the Central Laboratory of Liaocheng People’s Hospital of Shandong Province for the revision and suggestions on some of the charts in the article; and XinYi Animal Hospital Liaocheng Central Hospital for providing the operating platform for animal experiments and animal care.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (11827803 and U20A20390, to Yubo Fan), Higher Education Discipline Innovation Project (No. B13003, to Yubo Fan), and Medical and Health Science and Technology Development Project of Shandong Province (No.202203010759, to Fei Xu). Science and Technology Collaboration Project of Shanxi Province, Grant Number: [No.202304041101033].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.X.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Validation. X.L. J.: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. S.D.C.: Conceptualization, Methodology. Y.B.F.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, F., Jia, X., Chai, S. et al. Thrombospondin-4 regulates apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells after artery transplanted into vein. Sci Rep 16, 150 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29180-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29180-2