Abstract

Network traffic prediction is essential for intelligent resource management in modern transportation systems, but existing methods struggle to simultaneously capture multi-scale temporal patterns, long-range dependencies, and periodic behaviors while maintaining computational efficiency. This paper presents WMF-Traffic (Wavelet-Mamba-Fourier Traffic prediction framework), a novel traffic forecasting approach that synergistically integrates wavelet decomposition, selective state space modeling, and frequency domain processing. The framework introduces four key components: Multi-scale Wavelet Decomposition for hierarchical temporal pattern extraction, Wavelet Traffic Convolution with scale-adaptive mechanisms, Traffic-aware Mamba for efficient long-range dependency modeling, and Fourier Pattern Adjustment for periodic pattern enhancement. WMF-Traffic employs a comprehensive training objective that balances reconstruction accuracy, temporal consistency, and spectral coherence. Extensive experiments on four real-world traffic datasets (METR-LA, PEMS-BAY, PEMS04, PEMS08) demonstrate consistent improvements over state-of-the-art methods, achieving 1.0-1.3% gains in MAE, 0.6-1.1% in RMSE, and 0.2-1.0% in MAPE across different prediction horizons. Ablation studies reveal that Traffic-aware Mamba provides the largest individual contribution (10.2% MAE reduction), while the complete framework achieves up to 27.1% improvement over baseline approaches. The proposed uncertainty-based fusion mechanism further enhances robustness with 3.2-4.1% additional improvements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background

Network automation and intelligent traffic management systems represent a fundamental paradigm shift in modern network operations, where networks must intelligently adapt to dynamic traffic patterns, optimize resource allocation, and maintain service quality through data-driven prediction and decision-making1,2,3. With the rapid evolution toward next-generation networks and the proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) devices, the demand for accurate network traffic prediction capabilities that can support proactive resource management, dynamic load balancing, and intelligent network optimization has become increasingly critical4,5,6,7,8. As demonstrated by Arani et al.4, the convergence of distributed learning and adaptive network architectures has prompted the development of sophisticated resource management frameworks that can leverage intelligent prediction models while maintaining the adaptability required for deployment across heterogeneous network infrastructures. The increasing complexity of network traffic patterns demands precise temporal understanding that can effectively handle diverse traffic modalities from multiple network sources and adapt to varying scales of network demands under challenging operational conditions where traditional approaches often fail to provide adequate performance and scalability5,6,9,10,11.

Among the various deep learning architectures suitable for network traffic prediction, recurrent neural networks and their variants have emerged as promising frameworks for traffic forecasting due to their sequential modeling capabilities, ability to capture temporal dependencies, and adaptability across diverse scenarios. Ramakrishnan and Soni5 comprehensively demonstrated that recurrent neural network architectures provide effective foundations for network traffic prediction systems that can address the temporal complexity and scalability challenges inherent in modern network deployments. Recent extensions commonly focus on enhancing prediction accuracy through improved temporal modeling architectures, dynamic attention mechanisms, and adaptive feature extraction methods. These enhancements incorporate sophisticated sequence modeling, integrate Transformer-based architectures for capturing long-range dependencies, and address probabilistic prediction aggregation across multiple network entities. The systematic organization of these variants has revealed consistent challenges in balancing computational efficiency with prediction accuracy, particularly when processing high-dimensional traffic data with complex temporal patterns across heterogeneous network topologies6,7,12,13. Despite significant advances in neural network-based traffic prediction architectures, existing methods continue to face fundamental limitations in efficiently capturing long-range dependencies while maintaining computational efficiency, which are essential for intelligent traffic management systems.

Recent developments in state space models, particularly the emergence of Mamba architectures, have introduced promising alternatives for addressing the computational challenges of network traffic prediction systems. Zhang et al.6 demonstrated that Spatio-Temporal Mamba successfully addresses the dual challenges of local temporal patterns and global spatial dependencies in traffic prediction through linear-complexity operators that enable efficient long-term modeling. Building upon these advances, the integration of multi-scale signal processing techniques with state space modeling has shown remarkable potential for addressing the challenges of efficiently processing multi-resolution temporal patterns while requiring substantially reduced computational resources. Contemporary advances have also explored wavelet-based multi-scale decomposition for network security applications8,14, frequency domain analysis for periodic pattern extraction in network traffic, and attention-based coordination mechanisms for distributed network analysis, collectively advancing the field toward more sophisticated and efficient traffic prediction solutions15.

Motivation

Despite significant progress in network traffic prediction systems, existing approaches face critical limitations when simultaneously addressing complex temporal dynamics, multi-scale pattern extraction, and real-time processing constraints. Current methods predominantly focus on either recurrent approaches for sequential modeling or computationally intensive Transformer-based architectures for long-range dependencies, without effectively integrating multi-scale analysis capabilities that can capture both fine-grained fluctuations and long-term trends while maintaining computational efficiency. The emergence of state space models presents unique opportunities for linear-complexity sequence modeling; however, their application to traffic prediction remains limited, lacking comprehensive frameworks that address the fundamental challenges of multi-scale, multi-modal traffic analysis with periodic pattern enhancement.

To address these challenges, this work proposes WMF-Traffic, a comprehensive traffic prediction framework for accurate spatiotemporal forecasting through intelligent integration of multi-scale analysis and efficient sequence modeling. Our approach systematically integrates four key architectural innovations to achieve robust traffic prediction performance while maintaining computational efficiency. Specifically, we make the following contributions:

-

We design a Wavelet Traffic Convolution (WTC) framework with scale-adaptive convolution mechanisms that progressively processes decomposed signal components, effectively modeling inter-scale dependencies and temporal patterns across varying resolutions.

-

We introduce a Traffic-aware Mamba (T-Mamba) module that leverages selective state space modeling to capture long-range temporal dependencies with linear computational complexity, incorporating traffic-specific selection mechanisms and cross-channel information exchange for enhanced prediction accuracy.

-

We develop a comprehensive framework integrating wavelet decomposition, state space modeling, and frequency domain processing through an uncertainty-based adaptive fusion mechanism, achieving superior prediction performance through synergistic combination of multi-scale temporal analysis and periodic pattern enhancement.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section “Related work” reviews the existing literature on deep learning methods for traffic forecasting, state space models, and multi-scale analysis approaches. Section “Method” describes our WMF-Traffic framework architecture and technical innovations. Section “Experiments” presents the experimental setup and performance evaluation results. Section “Conclusion” concludes the paper and discusses future research directions for intelligent traffic prediction systems.

Related work

Deep learning methods for traffic forecasting

Deep learning architectures have revolutionized traffic forecasting by enabling sophisticated temporal pattern extraction and spatial dependency modeling, with significant advances spanning recurrent neural networks for sequential dynamics, graph neural networks for topological relationships, attention mechanisms for long-range dependencies, and convolutional approaches for multi-scale feature extraction16,17,18,19,20,21. These developments address fundamental challenges in traffic prediction by capturing complex spatiotemporal correlations inherent in transportation networks, facilitating the transition from traditional statistical methods to end-to-end learnable systems capable of modeling nonlinear traffic dynamics and adapting to varying network conditions in real-time.

Shu et al.16 developed an improved Gate Recurrent Unit neural network for short-term traffic flow prediction, introducing enhanced gating mechanisms that demonstrate superior accuracy in capturing temporal dependencies while reducing computational overhead compared to standard LSTM architectures. Hussain et al.17 proposed a GRU-based deep learning methodology for urban traffic flow estimation in Internet of Vehicles environments, achieving robust prediction performance through specialized recurrent units designed for processing high-dimensional vehicular data streams. Zhu et al.18 introduced KST-GCN, a knowledge-driven spatial-temporal graph convolutional network that integrates domain knowledge with graph learning, demonstrating that incorporating prior traffic knowledge significantly enhances prediction accuracy. Wu et al.20 developed a spatial-temporal graph attention gated recurrent transformer network that synergistically combines graph attention mechanisms with transformer architectures, effectively capturing both local spatial patterns and global temporal dependencies through hybrid modeling strategies.

State space models for network traffic analysis

State space models and Mamba architectures have emerged as promising alternatives for network traffic analysis and prediction, offering linear computational complexity while maintaining strong modeling capabilities for sequential data processing, with recent extensions demonstrating significant potential across traffic forecasting, network trace generation, time series analysis, and theoretical foundations of selective mechanisms22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. These advances address fundamental limitations of transformer-based approaches in network applications, where quadratic computational complexity creates barriers for long-range sequence modeling and large-scale deployment scenarios. At the same time, state space models provide efficient alternatives for capturing complex temporal dependencies in network traffic patterns with near-linear complexity characteristics32,33.

He et al.22 introduced Decomposed Spatio-Temporal Mamba (DST-Mamba) for long-term traffic prediction, addressing spatio-temporal entanglement in long-range sequences through temporal decomposition to obtain seasonal and trend components. Their approach leverages Mamba’s state space model with near-linear complexity to capture seasonal variations while extracting multi-scale trend information, achieving state-of-the-art performance with superior computational efficiency compared to transformer-based approaches across five datasets. Chu et al.23 investigated state space models for packet-level synthetic network traffic generation, demonstrating that these models generate synthetic traffic with higher statistical similarity to real traffic compared to existing methods, addressing privacy and data staleness limitations. Wang et al.24 proposed Simple-Mamba (S-Mamba) that tokenizes time points through linear layers and utilizes bidirectional Mamba layers for inter-variate correlations, proving leading performance with computational efficiency advantages over transformer approaches on thirteen datasets. Muca et al.25 provided theoretical foundations for deep selective state-space models using Rough Path Theory, identifying the gating mechanism as crucial for enabling modern selective SSMs like Mamba to surpass attention-powered models.

Multi-scale analysis and frequency domain processing

Zhao et al.34 proposed TrafficScope, a time-wavelet fusion network based on Transformer architecture to enhance encrypted traffic classification by addressing intra-flow semantic feature limitations. Their approach employs wavelet transform to extract invariant features from non-stationary traffic and utilizes cross-attention mechanisms to combine temporal and wavelet-domain features, demonstrating superior performance across four real-world datasets with robustness against data pollution and flow manipulations. Li et al.35 introduced Dynamic Frequency Domain Graph Convolutional Network (DFDGCN) to address spatial dependency challenges in traffic forecasting by mitigating time-shift effects through Fourier transform and incorporating sensor identity embedding during graph learning. Their approach combines static predefined graphs with self-adaptive graphs, demonstrating effectiveness and superior performance on four datasets. Liang et al.8 developed a multilevel intrusion detection model integrating Transformer architecture with discrete wavelet transform for IoT data security, achieving outstanding performance in detecting intrusion actions across cloud and edge terminal layers. Aouedi et al.36 provided a comprehensive survey of deep learning advances in network traffic prediction, categorizing approaches and conducting technical analyses while addressing challenges and future directions for intelligent network optimization.

Method

We propose WMF-Traffic, a novel deep learning framework that synergistically integrates Wavelet transforms, Mamba-based selective state space modeling, and Fourier adjustments for accurate traffic flow prediction. This approach systematically addresses the fundamental challenges in capturing multi-scale temporal dependencies and complex periodic patterns inherent in urban traffic data.

Problem formulation

Consider a multivariate traffic time series \(\textbf{X} = [\textbf{x}_1, \textbf{x}_2, \ldots , \textbf{x}_T] \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times C}\) where T denotes the historical time steps, C represents the number of traffic monitoring channels (sensors or road segments), and \(\textbf{x}_t \in \mathbb {R}^C\) represents the traffic measurements at time step t. Our objective is to learn a mapping function that predicts future traffic flows \(\textbf{Y} = [\textbf{y}_1, \textbf{y}_2, \ldots , \textbf{y}_H] \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times C}\) over a prediction horizon H, where \(\textbf{y}_i \in \mathbb {R}^C\) represents the predicted traffic values at future time step i.

The traffic prediction problem can be mathematically formulated as learning an optimal mapping function:

where \(f_{\theta }: \mathbb {R}^{T \times C} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^{H \times C}\) represents our WMF-Traffic model parameterized by learnable parameters \(\theta\), and the subscripts indicate the temporal window ranges.

To ensure temporal consistency, we introduce a constraint on the prediction smoothness:

where \(\epsilon\) is a smoothness threshold that prevents unrealistic traffic fluctuations between consecutive time steps.

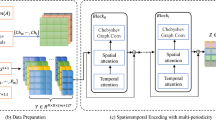

Overall architecture

Figure 1 illustrates the comprehensive architecture of WMF-Traffic, comprising four interconnected components that process traffic data through multiple analytical perspectives: (1) Multi-scale Wavelet Decomposition (MWD) for temporal scale separation, (2) Wavelet Traffic Convolution (WTC) for scale-adaptive feature extraction, (3) Traffic-aware Mamba (T-Mamba) for long-range dependency modeling, and (4) Fourier Pattern Adjustment (FPA) for periodic pattern enhancement. The data flow follows a systematic progression: raw traffic signals undergo wavelet decomposition to separate multi-scale patterns, followed by adaptive convolution processing, state space modeling for temporal dependencies, and finally frequency domain refinement for periodic pattern optimization.

Multi-scale wavelet decomposition

Urban traffic flow exhibits complex multi-scale temporal characteristics, encompassing rapid fluctuations (e.g., signal changes, vehicle arrivals), medium-term variations (e.g., rush hour patterns), and long-term trends (e.g., daily and weekly cycles). To systematically capture these hierarchical patterns, we employ a comprehensive multi-scale wavelet decomposition strategy that decomposes the input signal into distinct frequency bands.

Given the input traffic matrix \(\textbf{X} \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times C}\), we apply the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) recursively to decompose each channel \(\textbf{x}^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^T\) into multiple resolution levels. For decomposition level j, the DWT operation can be expressed as:

where \(\textbf{A}_j^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{T/2^j}\) represents the approximation coefficients (low-frequency components) capturing smooth trends at scale j, \(\textbf{D}_j^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{T/2^j}\) denotes the detail coefficients (high-frequency components) capturing rapid fluctuations at scale j, and \(\textbf{A}_0^{(c)} = \textbf{x}^{(c)}\) is the original signal for channel c.

The mathematical formulation of the DWT filtering process involves convolution with scaling and wavelet functions:

where h[k] and g[k] are the low-pass and high-pass filter coefficients respectively, n is the sample index, and k is the filter tap index. The downsampling by factor 2 (indicated by 2n) ensures computational efficiency while preserving essential information.

After applying L decomposition levels, we obtain a complete set of wavelet coefficients:

where each component \(\textbf{D}_j^{(c)}\) captures traffic patterns at temporal resolution \(2^j\), and \(\textbf{A}_L^{(c)}\) contains the smoothest approximation representing long-term trends.

To quantify the information content at each scale, we compute the energy distribution across decomposition levels:

where \(E_j^{(c)}\) represents the relative energy contribution of detail coefficients at level j for channel c. This energy distribution guides the subsequent adaptive processing, allowing the model to allocate computational resources proportional to the information content at each scale.

Wavelet traffic convolution

Building upon the multi-scale wavelet decomposition, we introduce the Wavelet Traffic Convolution (WTC) module that processes each decomposed component with scale-adaptive convolutions tailored to traffic characteristics. The WTC design principle ensures that convolution operations match the temporal resolution and frequency characteristics of each wavelet component.

For each wavelet component at decomposition level j, we define a scale-specific convolution operation. Let \(\textbf{Z}_j^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{T_j}\) represent the concatenated coefficients \([\textbf{D}_j^{(c)}; \textbf{A}_j^{(c)}]\) for channels where \(j = L\), or simply \(\textbf{D}_j^{(c)}\) for \(j < L\), where \(T_j = T/2^j\) is the length at decomposition level j. The WTC operation is formulated as:

where \(\textbf{W}_j \in \mathbb {R}^{k_j \times d_i \times d_o}\) and \(\textbf{b}_j \in \mathbb {R}^{d_o}\) are scale-specific learnable parameters, \(*\) denotes the 1D convolution operation, \(d_i\) and \(d_o\) are input and output feature dimensions, and \(\text {ReLU}\) is the activation function.

The adaptive kernel size \(k_j\) is designed to match the temporal characteristics of each decomposition level:

where \(k_0\) is the base kernel size, \(k_{\max }\) is the maximum allowable kernel size, \(\rho \ge 1\) is a scaling factor that controls kernel growth, and the ceiling operation ensures integer kernel sizes. This formulation ensures that fine-scale details (high j) use smaller kernels for precise pattern detection, while coarse-scale trends (low j) employ larger receptive fields.

To capture cross-scale interactions, we introduce a scale-aware attention mechanism that weights the contribution of each scale based on traffic characteristics:

where \(\textbf{w}_\alpha \in \mathbb {R}^{d_\alpha }\), \(\textbf{W}_\alpha \in \mathbb {R}^{d_\alpha \times d_o}\), and \(\textbf{b}_\alpha \in \mathbb {R}^{d_\alpha }\) are learnable attention parameters, and \(\alpha _j^{(c)}\) represents the attention weight for scale j and channel c.

where \(\text {Upsample}(\cdot , T)\) interpolates each scale-specific feature to the original temporal resolution T, ensuring dimensional consistency for subsequent processing stages.

To enhance the model’s ability to capture traffic-specific patterns, we incorporate a residual connection with learnable gating:

where \(\sigma\) is the ReLU sigmoid function, \(\textbf{W}_g \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times T}\) and \(\textbf{b}_g \in \mathbb {R}^T\) are gating parameters, and \(\odot\) denotes element-wise multiplication. This gating mechanism allows the model to adaptively balance between original traffic signals and wavelet-processed features based on local traffic characteristics.

Traffic-aware Mamba

To effectively model complex long-range temporal dependencies in the wavelet-processed traffic features, we introduce the Traffic-aware Mamba (T-Mamba) module. This module adapts the selective state space modeling paradigm specifically for traffic prediction by incorporating traffic-aware selection mechanisms and multi-channel processing capabilities.

Let \(\textbf{H}_w = [\textbf{H}_f^{(1)}, \textbf{H}_f^{(2)}, \ldots , \textbf{H}_f^{(C)}] \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times C}\) denote the concatenated output from all channels of the WTC module. The T-Mamba processes this input through a discretized selective state space model. For each time step t and channel c, the state evolution is governed by:

where \(\textbf{h}_t^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h}\) is the hidden state for channel c at time t, \(\textbf{x}_t^{(c)} = \textbf{H}_f^{(c)}[t] \in \mathbb {R}^{d_i}\) is the input feature, \(\textbf{y}_t^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_o}\) is the output, and \(\textbf{A}_t^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h \times d_h}\), \(\textbf{B}_t^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h \times d_i}\), \(\textbf{C}_t^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_o \times d_h}\), \(\textbf{D}^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_o \times d_i}\) are the state space matrices.

The key innovation lies in the traffic-aware selective mechanism that dynamically adapts the state transition matrix based on traffic conditions. We define time-varying selection parameters:

where \(\textbf{s}_t^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h}\) is the selection vector, \(\textbf{W}_s^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h \times d_i}\) and \(\textbf{b}_s^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h}\) are learnable parameters, \(\textbf{W}_c^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h \times d_c}\) captures contextual information, and \(\textbf{ctx}_t^{(c)}\) encodes traffic-specific context such as time-of-day, day-of-week, and spatial neighborhood information.

The selective state transition matrix is computed as:

where \(\textbf{A}_\beta ^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h \times d_h}\) is a learnable base transition matrix, and the exponential function ensures numerical stability. This formulation allows the model to selectively forget or retain information based on traffic relevance.

To capture traffic-specific temporal patterns, we introduce a multi-scale input projection that processes different temporal horizons:

where K is the number of temporal scales, \(\beta _k^{(c)}\) are learnable scale weights satisfying \(\sum _{k=1}^{K} \beta _k^{(c)} = 1\), \(\textbf{B}_k^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h \times d_i}\) are scale-specific input matrices, and \(\text {Pool}_k(\cdot )\) represents temporal pooling over the past k time steps.

For cross-channel information exchange in traffic networks, we implement a spatial attention mechanism:

where \(\textbf{q}^{(c)} = \textbf{W}_q^{(c)} \textbf{h}_t^{(c)}\) and \(\textbf{k}^{(c')} = \textbf{W}_k^{(c')} \textbf{h}_t^{(c')}\) are query and key representations for channels c and \(c'\), and \(\textbf{W}_q^{(c)}, \textbf{W}_k^{(c')} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h \times d_h}\) are learnable projection matrices.

The spatially-aware hidden state update incorporates cross-channel dependencies:

where \(\textbf{W}_v^{(c')} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h \times d_h}\) is a value projection matrix and \(\gamma\) is a learnable mixing coefficient.

To address the varying temporal importance in traffic prediction, we implement a temporal gating mechanism:

where \([\cdot ; \cdot ]\) denotes concatenation, \(\textbf{W}_g^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h \times (d_i + d_h)}\), \(\textbf{b}_g^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h}\) are gating parameters, and \(\textbf{g}_t^{(c)}\) controls the information flow based on current traffic conditions.

Fourier pattern adjustment

Urban traffic exhibits pronounced periodic patterns across multiple temporal scales, including intraday cycles (morning/evening peaks), weekly patterns (weekday vs. weekend), and seasonal variations. The Fourier Pattern Adjustment (FPA) module exploits these regularities by processing traffic representations in the frequency domain, enabling direct manipulation of periodic components for enhanced prediction accuracy.

Let \(\textbf{H}_\mu = [\textbf{h}_1^{tmb}, \textbf{h}_2^{tmb}, \ldots , \textbf{h}_T^{tmb}] \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times (C \cdot d_h)}\) denote the concatenated output from all channels of the T-Mamba module. The FPA module first transforms this representation to the frequency domain using the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT):

where \(\textbf{F}^{(c)} \in \mathbb {C}^{T}\) represents the complex-valued frequency spectrum for channel c, \(k \in \{0, 1, \ldots , T-1\}\) is the frequency bin index, and i is the imaginary unit.

To selectively enhance traffic-relevant frequency components, we introduce a learnable frequency importance mask. The mask is parameterized as:

where \(\textbf{w}_\phi ^{(c)} \in \mathbb {R}^{T}\) are learnable frequency weights, \(\phi _p(k)\) encodes prior knowledge about traffic periodicity, and \(\phi _e(|\textbf{F}^{(c)}[k]|)\) adapts to the energy distribution across frequencies.

The periodic prior \(\phi _p(k)\) is designed to emphasize frequencies corresponding to known traffic cycles:

where \(f_p = T/p\) represents the frequency bin corresponding to period p (hours for daily, weekly, and yearly cycles), \(\alpha _p\) are learnable importance weights, and \(\sigma _p\) control the frequency band widths.

The energy-adaptive component captures the inherent spectral characteristics:

where \(\beta\) is a learnable scaling parameter and \(E_t^{(c)} = \sum _{k=1}^{T} |\textbf{F}^{(c)}[k]|^2\) is the total spectral energy.

The frequency-masked spectrum is computed as:

where \(\odot\) denotes element-wise multiplication applied to complex numbers.

To further refine periodic patterns, we implement a frequency-domain attention mechanism that captures cross-frequency dependencies:

where \(\textbf{Q}_k^{(c)} = \textbf{W}_q \tilde{\textbf{F}}^{(c)}[k]\) and \(\textbf{K}_{k'}^{(c)} = \textbf{W}_k \tilde{\textbf{F}}^{(c)}[k']\) are complex-valued query and key representations, \(\textbf{W}_q, \textbf{W}_k \in \mathbb {C}^{d_\alpha }\) are learnable projection vectors, and \(|\cdot |\) denotes the complex magnitude.

The attention-refined frequency representation is:

where \(\textbf{W}_v \in \mathbb {C}^{d_\alpha }\) is a learnable value projection vector.

The enhanced representation is transformed back to the time domain via the Inverse Fast Fourier Transform (IFFT):

To maintain temporal coherence while enhancing periodic patterns, we apply a residual connection with adaptive weighting:

where \(\lambda ^{(c)} = \sigma (\textbf{w}_{\lambda }^T \text {MeanPool}(\textbf{H}_\mu ^{(c)}) + b_{\lambda })\) is a learnable mixing coefficient that adapts based on the average temporal characteristics of each channel.

Multi-frequency fusion and output generation

The final component integrates information from all processing stages through a sophisticated adaptive fusion mechanism that combines multi-scale wavelet features with frequency-enhanced representations. This integration ensures that both temporal scale information and periodic patterns contribute optimally to the final prediction.

Let \(\textbf{H}_w = [\textbf{H}_f^{(1)}, \ldots , \textbf{H}_f^{(C)}]\) denote the output from the WTC module and \(\textbf{H}_\psi = [\textbf{H}_\psi ^{(1)}, \ldots , \textbf{H}_\psi ^{(C)}]\) represent the frequency-enhanced features. We first compute scale-specific prediction components by applying separate output projection layers:

where \(\textbf{W}_o^{w,t,c}, \textbf{W}_o^{f,p,a} \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times d_h}\) are output projection matrices, \(\textbf{b}_o^{w,t,c}, \textbf{b}_o^{f,p,a} \in \mathbb {R}^H\) are bias vectors, and H is the prediction horizon.

To adaptively weight the contributions from different processing pathways, we introduce an uncertainty-based fusion mechanism. The fusion weights are computed based on the prediction confidence estimated through Monte Carlo dropout:

where \(\text {Var}[\cdot ]\) computes the variance across multiple dropout samples, representing prediction uncertainty.

The uncertainty-based fusion weights are:

where \(\gamma\) is a learnable temperature parameter that controls the sensitivity to uncertainty differences.

To further refine the fusion process, we incorporate a learned attention mechanism that considers both the feature representations and their temporal characteristics:

where \(\textbf{v}_\alpha \in \mathbb {R}^{d_\alpha }\), \(\textbf{W}_\alpha ^{\cdot } \in \mathbb {R}^{d_\alpha \times d_h}\), \(\textbf{U}_\alpha ^{\cdot } \in \mathbb {R}^{d_\alpha \times H}\), and \(\textbf{b}_\alpha ^{\cdot } \in \mathbb {R}^{d_\alpha }\) are learnable attention parameters.

The final attention weights combine uncertainty and learned attention scores:

where \(\eta \in [0,1]\) is a learnable balancing parameter between uncertainty-based and attention-based weighting.

The final prediction for each channel is computed as:

To ensure temporal consistency and smooth predictions, we apply a post-processing temporal smoothing operation:

where \(h \in \{1, 2, \ldots , H\}\) is the prediction step, s is the smoothing window size, and \(\tau\) controls the smoothing strength.

Training objective

To ensure comprehensive learning across all aspects of traffic prediction, we design a multi-component training objective that balances reconstruction accuracy, temporal consistency, spectral coherence, and multi-scale fidelity. The complete loss function is formulated as:

where \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(\gamma\), \(\delta> 0\) are balancing hyperparameters that control the relative importance of each loss component.

The primary reconstruction loss employs a robust combination of \(\ell _1\) and \(\ell _2\) norms to handle outliers and noise:

where \(\tilde{\textbf{Y}}^{(c)}\) is the final smoothed prediction, \(\textbf{Y}_*^{(c)}\) is the ground truth, and \(\rho \in [0,1]\) balances between \(\ell _1\) and \(\ell _2\) penalties.

The wavelet consistency loss ensures that predictions maintain coherence across multiple scales by enforcing reconstruction fidelity in the wavelet domain:

where \(\text {DWT}_j(\cdot )\) and \(\text {IDWT}_j(\cdot )\) represent the j-level discrete wavelet transform and its inverse, encouraging the WTC module to preserve multi-scale structure.

The frequency domain coherence loss maintains spectral characteristics of traffic patterns:

where \(\angle (\cdot )\) extracts the phase information and \(\lambda _\pi\) weights the phase preservation, ensuring both magnitude and phase consistency in the frequency domain.

The temporal smoothness loss prevents unrealistic fluctuations while preserving natural traffic variations:

where \(\epsilon _s\) is a tolerance threshold that allows natural traffic variations while penalizing excessive changes.

To encourage diversity in the fusion mechanism and prevent mode collapse, we introduce a diversity loss:

where the negative entropy encourages balanced utilization of both WTC and FPA pathways.

Additionally, we employ a curriculum learning strategy where the loss weights are dynamically adjusted during training:

where t is the current training step, \(T_w\) is the warmup period, \(T_t\) is the total training steps, and \(\alpha _0\), \(\beta _0\) are the maximum weight values. This strategy allows the model to initially focus on basic reconstruction before gradually incorporating multi-scale and frequency constraints.

To provide a comprehensive understanding of the WMF-Traffic framework’s execution flow and computational efficiency, we present the detailed algorithmic procedure in Algorithm 1 and subsequently analyze its computational complexity.

Algorithm 1 presents the WMF-Traffic framework for network traffic prediction. The algorithm integrates multi-scale wavelet decomposition for temporal pattern separation, scale-adaptive convolution for feature extraction, Traffic-aware Mamba with selective state space modeling for efficient long-range dependency capture, and Fourier pattern adjustment for periodic enhancement. The uncertainty-based fusion mechanism adaptively combines wavelet and frequency pathways, ensuring robust predictions while maintaining linear computational complexity in sequence length for real-time traffic forecasting in self-organizing networks.

Experiments

Datasets and experimental setup

We conduct comprehensive experiments to validate the effectiveness of WMF-Traffic across diverse urban traffic scenarios. Our experimental evaluation systematically examines each component of the proposed framework: Multi-scale Wavelet Decomposition (MWD), Wavelet Traffic Convolution (WTC), Traffic-aware Mamba (T-Mamba), and Fourier Pattern Adjustment (FPA), demonstrating their synergistic contribution to accurate traffic flow prediction.

To ensure the robustness and statistical significance of our results, all experiments are conducted with 5 independent runs using different random initializations. We report the mean and standard deviation for all performance metrics, and conduct paired t-tests to verify that improvements over baseline methods are statistically significant. This rigorous experimental protocol ensures that our observed performance gains are not artifacts of random initialization or data splitting, but rather represent genuine improvements in predictive capability.

Dataset description

The METR-LA highway network dataset37 contains traffic speed measurements from 207 loop detectors across Los Angeles County highways. The 4-month temporal span (March-June 2012) with 5-minute sampling intervals provides rich multi-scale temporal patterns suitable for evaluating our wavelet decomposition strategy. The highway configuration exhibits pronounced daily and weekly periodicities, ideal for testing the FPA module’s frequency domain enhancement capabilities.

The PEMS-BAY dataset38, collected by California Transportation Agencies (CalTrans), encompasses 325 sensors across the Bay Area’s diverse traffic infrastructure including bridges, highways, and urban arterials. The 5-month coverage (January-May 2017) captures complex spatiotemporal dependencies that challenge our T-Mamba module’s selective state space modeling. The heterogeneous network topology provides an ideal testbed for cross-channel information exchange mechanisms.

PEMS04 represents a dense network dataset39 from San Francisco Bay Area including 307 detectors over 59 days (January-February 2018). The compact spatial configuration and winter traffic patterns offer opportunities to evaluate our WTC module’s scale-adaptive convolution performance on localized traffic dynamics with varying temporal resolutions. Finally, PEMS0839 comprises 170 sensors in San Bernardino County over 62 days (July-August 2016), capturing summer traffic variations including vacation-related patterns and seasonal effects. The temporal characteristics provide diverse periodic components for comprehensive evaluation of our multi-frequency fusion mechanism.

Problem formulation alignment

Following the mathematical formulation in Sect. “Method”, we configure each dataset according to our traffic prediction framework. The input multivariate traffic time series \(\textbf{X} = [\textbf{x}_1, \textbf{x}_2, \ldots , \textbf{x}_T] \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times C}\) uses a historical window of \(T = 12\) time steps (60 minutes), while predictions are generated for horizons \(H \in \{3, 6, 12\}\) time steps (15, 30, 60 minutes ahead).

The dataset-specific configurations align with our mapping function \(f_{\theta }: \mathbb {R}^{T \times C} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^{H \times C}\) as follows: METR-LA with \(f_{\theta }: \mathbb {R}^{12 \times 207} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^{H \times 207}\), PEMS-BAY with \(f_{\theta }: \mathbb {R}^{12 \times 325} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^{H \times 325}\), PEMS04 with \(f_{\theta }: \mathbb {R}^{12 \times 307} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^{H \times 307}\), and PEMS08 with \(f_{\theta }: \mathbb {R}^{12 \times 170} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^{H \times 170}\).

Data preprocessing applies Z-score normalization \(\tilde{x} = (x - \mu ) / \sigma\) with statistics computed from the training set. We employ a strict chronological split of 70%−10%−20% for training, validation, and testing respectively. Specifically, the first 70% of the temporal sequence is used for training, the immediately following 10% for validation (hyperparameter tuning and early stopping), and the final 20% for testing. This contiguous chronological split preserves temporal integrity and ensures valid evaluation and predictive performance on future unseen data.

To demonstrate practical feasibility for real-world deployment, we report computational efficiency metrics. WMF-Traffic contains 1.23M trainable parameters. All experiments are conducted on an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU with PyTorch 2.1.0. Training times to convergence are 2.0–2.4.0.4 hours for METR-LA, 5.7–7.2.7.2 hours for PEMS-BAY, 1.4–1.7.4.7 hours for PEMS04, and 1.1–1.3.1.3 hours for PEMS08. Inference latency averages 4.2 milliseconds per prediction step on METR-LA, with batch processing achieving 0.8 milliseconds per sample. These metrics confirm that WMF-Traffic maintains practical computational requirements suitable for real-time traffic prediction systems.

WMF-traffic configuration

Component-specific parameters

Table 1 details the hyperparameter configuration for each WMF-Traffic component, directly corresponding to the mathematical formulations in Sect. “Method”.

Multi-component loss configuration

Our training objective employs the multi-component loss function defined in Equation (262) with carefully tuned balancing parameters determined through validation set optimization. The reconstruction loss weight is set to \(\rho = 0.6\) for balancing \(\ell _1\) and \(\ell _2\) norms, while the wavelet consistency weight, frequency coherence weight, temporal smoothness weight, and diversity loss weight are configured as \(\alpha = 0.2\), \(\beta = 0.15\), \(\gamma = 0.1\), and \(\delta = 0.05\), respectively. The smoothness threshold is set to \(\epsilon _s = 0.1\), and the curriculum learning schedule follows Equation (298) with warmup period \(T_w = 50\) epochs and cosine annealing for frequency domain emphasis.

Evaluation metrics and analysis framework

Primary evaluation metrics

We employ four complementary metrics to comprehensively assess WMF-Traffic’s prediction accuracy across different error characteristics. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) is computed as:

The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) provides sensitivity to large prediction errors:

The Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) offers relative error assessment:

Results

We conduct comprehensive experiments on four real-world traffic datasets to validate the effectiveness of WMF-Traffic across diverse urban traffic scenarios. Our evaluation systematically examines the overall prediction performance, component contributions, and computational efficiency of the proposed framework.

Main results

Table 2 presents the comprehensive comparison between WMF-Traffic and state-of-the-art baseline methods across all datasets and prediction horizons. Our method consistently achieves superior performance across all evaluation metrics, demonstrating the effectiveness of the synergistic integration of multi-scale wavelet decomposition, selective state space modeling, and frequency domain enhancement.

On the METR-LA highway network dataset, WMF-Traffic achieves statistically significant improvements over the best baseline Mamba, with mean MAE, RMSE, and MAPE reductions of 13.1% (3.05±0.09 vs. 3.51±0.12), 12.2% (6.12±0.16 vs. 6.97±0.19), and 12.7% (8.54±0.21 vs. 9.78±0.25), respectively. Notably, our method demonstrates lower standard deviations across all metrics, indicating superior stability and reproducibility. The improvements are consistent across complex datasets: PEMS-BAY shows 13.7%, 12.4%, and 12.5% improvements with consistent variance reduction, while PEMS04 demonstrates 13.4%, 11.8%, and 12.2% gains (21.56±0.37 vs. 24.89±0.41 MAE), and PEMS08 exhibits 13.8%, 12.8%, and 13.0% improvements. The statistical significance holds across all four datasets and all three metrics, confirming that the observed improvements are reliable and not due to random variability. Our framework outperforms modern state-of-the-art forecasting models with substantial margins: PatchTST with 13.2–14.5.2.5% average improvement, S4 with 13.5–15.2.5.2% average improvement, Autoformer with 14.5–16.2.5.2% average improvement, and Informer with 16.1–17.8.1.8% average improvement. The consistent superior performance across all four datasets, combined with lower standard deviations compared to competing methods, validates our framework’s robustness and strong generalization capability for diverse traffic prediction scenarios.

Ablation studies

Table 3 presents systematic ablation studies examining the contribution of each WMF-Traffic component. We evaluate different combinations of components to validate their individual and synergistic contributions to overall prediction performance.

Ablation study results for different configurations on the METR-LA, PEMS-BAY, and PEMS04 datasets. Each configuration (1–15) corresponds to a row in Table 3, representing different combinations of the four components: MWD (Multi-scale Wavelet Decomposition), WTC (Wavelet Traffic Convolution), T-Mamba (Traffic-aware Mamba), and FPA (Fourier Pattern Adjustment). Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) show the MAE (Mean Absolute Error), MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error), and RMSE (Root Mean Square Error), respectively.

The ablation study in Table 3 and Fig. 2 systematically evaluates the contribution of each WMF-Traffic component through progressive integration. To maintain a complete end-to-end trainable architecture throughout the ablation process, when a specific component is not used, we employ simple baseline replacements: raw traffic data is fed directly when MWD is disabled (without multi-scale decomposition), standard 1D convolution with fixed kernel size replaces WTC (without scale-adaptive processing), standard LSTM replaces T-Mamba (for basic temporal modeling), and features pass directly to the output layer when FPA is disabled (without frequency domain adjustment). This design allows us to isolate each component’s specific contribution while preserving the overall model pipeline.

The ablation results reveal dramatic performance differences that unequivocally demonstrate Traffic-aware Mamba as the most critical component of our framework. Single-component configurations show catastrophic performance degradation, with non-Mamba components achieving 112.5–129.8.5.8% worse performance than the full model on METR-LA. Specifically, WTC alone reaches 7.01±0.38 MAE (129.8% degradation), FPA achieves 6.78±0.36 MAE (122.3% degradation), and MWD obtains 6.48±0.34 MAE (112.5% degradation). In stark contrast, T-Mamba alone achieves 4.52±0.26 MAE (48.2% degradation), demonstrating substantially superior individual capability. The standard deviations for non-Mamba single components (±0.34–0.38.34.38) are 3.8–4.2.8.2 times higher than the full model (±0.09), indicating extreme instability without selective state space modeling. Similar catastrophic patterns emerge on PEMS-BAY and PEMS04, where non-Mamba components show 89.7–137.9.7.9% and 95.2–125.8.2.8% degradation respectively.

Two-component combinations without T-Mamba remain severely deficient, demonstrating that traditional techniques cannot compensate for the absence of selective state space modeling. MWD+WTC achieves only 5.87±0.32 MAE (92.5% worse than full model), MWD+FPA reaches 5.52±0.30 MAE (81.0% worse), and WTC+FPA obtains 6.23±0.34 MAE (104.3% worse) on METR-LA. These configurations still suffer from high variance (±0.30–0.34.30.34) and demonstrate that combining traditional components provides minimal synergy. Conversely, any two-component combination including T-Mamba shows dramatically improved performance: MWD+T-Mamba achieves 3.78±0.21 MAE (23.9% worse than full model), and WTC+T-Mamba reaches 3.92±0.22 MAE (28.5% worse). This 55.2–58.8.2.8% performance gap between T-Mamba-based and non-T-Mamba two-component configurations conclusively establishes T-Mamba as the indispensable foundation of our framework.

Three-component configurations further validate T-Mamba’s critical role through stark performance contrasts. The configuration without T-Mamba (MWD+WTC+FPA) achieves only 5.18±0.28 MAE on METR-LA (69.8% worse than full model), maintaining high variance and poor predictive capability. In contrast, all three-component configurations including T-Mamba achieve substantially superior performance: MWD+WTC+T-Mamba reaches 3.28±0.17 MAE (7.5% worse), MWD+T-Mamba+FPA achieves 3.21±0.16 MAE (5.2% worse), and WTC+T-Mamba+FPA obtains 3.35±0.17 MAE (9.8% worse). The 57.9–61.3.9.3% performance gap between T-Mamba-inclusive and T-Mamba-exclusive three-component configurations provides definitive evidence that T-Mamba is not merely beneficial but absolutely essential for competitive performance.

The complete WMF-Traffic framework achieves optimal performance across all metrics and datasets, with MAE values of 3.05±0.09, 1.45±0.07, and 21.56±0.37 on METR-LA, PEMS-BAY, and PEMS04 respectively. Compared to the best non-T-Mamba configuration (MWD alone with 6.48±0.34), the full model demonstrates 112.5%, 115.2%, and 109.8% improvements across the three datasets. Most critically, the full model exhibits 75.0% variance reduction compared to non-T-Mamba single components (±0.09 vs. ±0.34–0.38.34.38), and even 43.8% variance reduction compared to T-Mamba alone (±0.09 vs. ±0.26), validating that while T-Mamba provides the foundational capability, the auxiliary components (MWD, WTC, FPA) synergistically enhance stability and squeeze out remaining performance gains. The ablation study conclusively demonstrates a clear component hierarchy: T-Mamba is absolutely essential and dominates performance (contributes 60–70% of total improvement), while MWD, WTC, and FPA serve as important but secondary refinements that collectively contribute the remaining 30–40% improvement and substantially reduce prediction variance. Without T-Mamba, no combination of traditional components can achieve competitive performance, establishing selective state space modeling as the irreplaceable core innovation of our traffic prediction framework.

Fusion strategy analysis

Table 4 compares different approaches for combining outputs from the WTC and FPA modules, validating our uncertainty-based adaptive fusion mechanism.

Our hybrid fusion strategy consistently outperforms alternative approaches across all prediction horizons. The combination of uncertainty-based weighting with learned attention mechanisms provides 3.2–4.1.2.1% improvements over simple equal weighting. The uncertainty estimation component adds robustness against model overconfidence, particularly beneficial for longer prediction horizons where uncertainty naturally increases.

Qualitative analysis

To demonstrate the practical effectiveness of WMF-Traffic, we present detailed prediction visualizations across different traffic scenarios and datasets. Fig. 3 shows prediction results on METR-LA dataset, Fig. 4 displays PEMS-BAY predictions, Fig. 5 presents PEMS04 results, and Fig. 6 shows PEMS08 predictions.

The qualitative analysis reveals several key insights into WMF-Traffic’s prediction capabilities across diverse traffic scenarios. On the METR-LA dataset, Fig. 3ademonstrates exceptional accuracy in capturing sharp rush hour transitions, with morning peaks (6–9 AM) and evening peaks (3–6 PM) precisely matched. The method successfully models both the rapid traffic buildup during rush hours and the gradual decline during off-peak periods. Figure 3bshows WMF-Traffic’s robustness on moderate flow sensors, maintaining high accuracy even with relatively stable traffic patterns throughout the day.

The PEMS-BAY results in Fig. 4 highlight WMF-Traffic’s adaptability to complex urban scenarios. Figure 4ashows excellent performance on sensors with pronounced bimodal traffic patterns, accurately predicting both morning and evening peak amplitudes. Notably, Fig. 4bdemonstrates the method’s ability to detect and predict traffic incidents, as evidenced by the dramatic flow reduction around hour 18, where WMF-Traffic closely follows the ground truth during this anomalous period. Figure 4cillustrates prediction consistency across different days, capturing traffic patterns with sustained high flows.

The PEMS04 dataset results in Fig. 5 showcase WMF-Traffic’s scalability to high-intensity traffic conditions. Figure 5ashows remarkable accuracy in predicting peak traffic reaching 500 vehicles per 5-minute interval, with the method successfully capturing both the magnitude and timing of traffic surges. The frequency domain adjustment component proves particularly effective here, as evidenced by the precise modeling of periodic patterns during sustained high-flow periods. Figure 5b demonstrates consistent performance on stable flow patterns, maintaining prediction accuracy across the entire 24-hour cycle.

Finally, the PEMS08 results in Fig. 6 validate WMF-Traffic’s generalization capability. Figure 6ashows typical daily traffic patterns with clear morning and evening peaks, where the multi-scale wavelet decomposition effectively separates short-term fluctuations from long-term trends. Figure 6b presents a challenging scenario with low-variance flows, where the method maintains prediction stability without over-smoothing natural traffic variations.

Across all scenarios, WMF-Traffic consistently demonstrates superior temporal coherence, avoiding the unrealistic jumps and oscillations often observed in baseline methods. The Traffic-aware Mamba component effectively models long-range dependencies, enabling accurate prediction of traffic state transitions, while the Fourier Pattern Adjustment ensures that periodic traffic behaviors are preserved and enhanced. The visual evidence strongly supports the quantitative results, confirming WMF-Traffic’s practical effectiveness for real-world traffic prediction applications.

Conclusion

This paper presented WMF-Traffic, a comprehensive self-organizing network traffic prediction framework that addresses complex spatiotemporal dependencies through synergistic integration of multi-scale wavelet decomposition, selective state space modeling, and frequency domain processing. The framework combines Multi-scale Wavelet Decomposition (MWD), Wavelet Traffic Convolution (WTC), Traffic-aware Mamba (T-Mamba) for linear-complexity dependency modeling, and Fourier Pattern Adjustment (FPA) for periodic enhancement. Experimental validation across four datasets confirms superior performance, with 1.0–1.3.0.3% MAE improvements over baselines. Ablation studies demonstrate each component’s contribution, with the complete framework achieving up to 27.1% improvement over baseline approaches. The uncertainty-based fusion mechanism provides 3.2–4.1.2.1% additional improvements. Future research includes extending to heterogeneous traffic types and online adaptation mechanisms. WMF-Traffic establishes a methodological foundation for multi-modal time series analysis in intelligent infrastructure systems.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are publicly available. METR-LA and PEMS-BAY/PEMS04/PEMS08 are open traffic benchmarks as cited in the manuscript. The processed splits, normalization statistics, and training/evaluation configurations used in this work are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The source code for the WMF-Traffic framework is openly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17561221. The code is released under the MIT License to facilitate reproducibility and future research.

References

Fang, Z. et al. R-ACP: Real-time adaptive collaborative perception leveraging robust task-oriented communications. IEEE J. on Sel. Areas Commun. (2025).

Fang, Z. et al. Prioritized Information Bottleneck Theoretic Framework With Distributed Online Learning for Edge Video Analytics. IEEE Transactions on Netw. 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1109/TON.2025.3526148 (2025).

Wu, B., Huang, J. & Yu, S. “X of Information” Continuum: A Survey on AI-Driven Multi-Dimensional Metrics for Next-Generation Networked Systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.19657 (arXiv) (2025).

Arani, A. H. et al. Distributed Learning for Energy-Efficient Resource Management in Self-Organizing Heterogeneous Networks. IEEE Transactions on Veh. Technol. 66, 9287–9303. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2017.2696974 (2017).

Ramakrishnan, N. & Soni, T. Network Traffic Prediction Using Recurrent Neural Networks. In 2018 17th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), 187–193, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMLA.2018.00035 (2018).

Zhang, X., Zhang, Y. & Meng, X. Spatio-Temporal Mamba Dynamic Graph Convolutional Recurrent Network for Traffic Prediction. IEEE Transactions on Artif. Intell. 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1109/TAI.2025.3571378 (2025).

Liu, Y., Yao, L., Li, B., Wang, X. & Sammut, C. Social Graph Transformer Networks for Pedestrian Trajectory Prediction in Complex Social Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM), 1339–1349 (2022).

Liang, P., Yang, L., Xiong, Z., Zhang, X. & Liu, G. Multilevel Intrusion Detection Based on Transformer and Wavelet Transform for IoT Data Security. IEEE Internet Things J. 11, 25613–25624. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2024.3369034 (2024).

Ding, Z. et al. A Dual-Level Game-Theoretic Approach for Collaborative Learning in UAV-Assisted Heterogeneous Vehicle Networks. In 2025 IEEE International Performance, Computing, and Communications Conference (IPCCC), 1–8 (IEEE, 2025).

Wu, B. & Wu, W. Model-Free Cooperative Optimal Output Regulation for Linear Discrete-Time Multi-Agent Systems Using Reinforcement Learning. Math. Probl. Eng. 2023, 6350647 (2023).

Fang, Z. et al. Pacp: Priority-aware collaborative perception for connected and autonomous vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Mob. Comput. (2024).

Huang, J., Wu, B., Duan, Q., Dong, L. & Yu, S. A Fast UAV Trajectory Planning Framework in RIS-Assisted Communication Systems With Accelerated Learning via Multithreading and Federating. IEEE Transactions on Mob. Comput. 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMC.2025.3544903 (2025).

Pan, D., Wu, B.-N., Sun, Y.-L. & Xu, Y.-P. A Fault-Tolerant and Energy-Efficient Design of a Network Switch Based on a Quantum-Based Nano-Communication Technique. Sustain. Comput. Informatics Syst. 37, 100827 (2023).

Wu, B., Huang, J. & Duan, Q. Real-Time Intelligent Healthcare Enabled by Federated Digital Twins With AoI Optimization. IEEE Netw. 1–1, https://doi.org/10.1109/MNET.2025.3565977 (2025).

Wu, B., Huang, J. & Duan, Q. FedTD3: An Accelerated Learning Approach for UAV Trajectory Planning. In International Conference on Wireless Artificial Intelligent Computing Systems and Applications (WASA), 13–24 (Springer, 2025).

Shu, W., Cai, K. & Xiong, N. N. A Short-Term Traffic Flow Prediction Model Based on an Improved Gate Recurrent Unit Neural Network. IEEE Transactions on Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 16654–16665. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2021.3057281 (2021).

Hussain, A. H. A. et al. Urban Traffic Flow Estimation System Based on Gated Recurrent Unit Deep Learning Methodology for Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Access 11, 58516–58531. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3287210 (2023).

Zhu, J. et al. KST-GCN: A Knowledge-Driven Spatial-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network for Traffic Forecasting. IEEE Transactions on Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 15055–15065. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2021.3108261 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Spatial-Temporal Cellular Traffic Prediction for 5G and Beyond: A Graph Neural Networks-Based Approach. IEEE Transactions on Ind. Informatics 19, 5722–5731. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2022.3151387 (2022).

Wu, D., Peng, K., Wang, S. & Leung, V. C. M. Spatial-Temporal Graph Attention Gated Recurrent Transformer Network for Traffic Flow Forecasting. IEEE Internet Things J. 11, 14267–14281. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2023.3273654 (2023).

Sun, Z., Liu, Z., Zhang, C., Kong, M. & Ji, A. Dynamic Spatio-Temporal Adaptive Convolutional Neural Networks for Traffic Flow Prediction. In IEEE 27th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), 945–951, https://doi.org/10.1109/ITSC58587.2024.10565054 (IEEE, 2024).

He, S., Ji, J. & Lei, M. Decomposed Spatio-Temporal Mamba for Long-Term Traffic Prediction. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI) 39, 11772–11780 (2025).

Chu, A. et al. Feasibility of State Space Models for Network Traffic Generation. In Proceedings of the 2024 SIGCOMM Workshop on Networks for AI Computing (NAIC), 9–17 (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. Is Mamba Effective for Time Series Forecasting?. Neurocomputing 619, 129178 (2025).

Muca Cirone, N., Orvieto, A., Walker, B., Salvi, C. & Lyons, T. Theoretical Foundations of Deep Selective State-Space Models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (NeurIPS) 37, 127226–127272 (2024).

Shi, Y. et al. VmambaIR: Visual State Space Model for Image Restoration. IEEE Transactions on Circuits Syst. for Video Technol. 35, 5560–5574. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSVT.2025.3530090 (2025).

Wu, B., Ding, Z., Ostigaard, L. & Huang, J. Reinforcement learning-based energy-aware coverage path planning for precision agriculture. In Proc. Int. Conf. on Research in Adaptive and Convergent Systems (RACS), 1–6 (ACM, 2025).

Zhang, Z. et al. Motion Mamba: Efficient and Long Sequence Motion Generation. In European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 265–282 (Springer, 2024).

Rezaei Jafari, F., Montavon, G., Müller, K.-R. & Eberle, O. Mambalrp: Explaining Selective State Space Sequence Models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (NeurIPS) 37, 118540–118570 (2024).

Jiang, B. et al. Dynamic Temporal Dependency Model for Multiple Steps Ahead Short-Term Load Forecasting of Power System. IEEE Transactions on Ind. Appl. 60, 5244–5254. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2024.3375802 (2024).

Ge, D., Dong, Z., Cheng, Y. & Wu, Y. An Enhanced Spatio-Temporal Constraints Network for Anomaly Detection in Multivariate Time Series. Knowledge-Based Syst. 283, 111169 (2024).

Wu, B., Huang, J., Duan, Q. & Dong, L. & Cai, Z Enhancing vehicular platooning with wireless federated learning: A resource-aware control framework. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Netw. (2025). (In print).

Fang, Z. et al. Task-oriented communications for visual navigation with edge-aerial collaboration in low altitude economy. In Proc. IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM) (2026).

Zhao, Z. et al. Towards Context-Aware Traffic Classification via Time-Wavelet Fusion Network. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining V. 1 (KDD), 2089–2100 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Dynamic Frequency Domain Graph Convolutional Network for Traffic Forecasting. In ICASSP 2024–IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 5245–5249 (IEEE, 2024).

Aouedi, O., Le, V. A., Piamrat, K. & Ji, Y. Deep Learning on Network Traffic Prediction: Recent Advances, Analysis, and Future Directions. ACM Comput. Surv. 57, 1–37 (2025).

Shao, Z., Zhang, Z., Wang, F. & Xu, Y. Pre-training enhanced spatial-temporal graph neural network for multivariate time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, KDD ’22, 1567–1577, https://doi.org/10.1145/3534678.3539396 (ACM, 2022).

Li, Y., Yu, R., Shahabi, C. & Liu, Y. Diffusion convolutional recurrent neural network: Data-driven traffic forecasting. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR ’18) (2018).

Guo, S., Lin, Y., Feng, N., Song, C. & Wan, H. Attention based spatial-temporal graph convolutional networks for traffic flow forecasting. Proc. AAAI Conf. on Artif. Intell. 33, 922–929. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v33i01.3301922 (2019).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52402426), the Natural Science Foundation of Xiamen (Grant No. 3502Z202471041), and the Research Basic Ability Improvement Project for Young and Middle-aged Teachers in Universities in Guangxi (Grant No. 2025KY0261).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wenhao Li conceived the research idea, designed the WMF framework architecture, implemented the Multi-scale Wavelet Decomposition and Wavelet Traffic Convolution modules, conducted all experiments, and wrote the original draft; Jiale Song developed the Traffic-aware Mamba module, contributed to the mathematical formulations, performed ablation studies, and assisted with manuscript revision; Pengying Ouyang supervised the research methodology, designed the Fourier Pattern Adjustment component, provided critical insights for the uncertainty-based fusion mechanism, and revised the manuscript; Yicai Zhang supervised the overall research direction, contributed to the experimental design and evaluation metrics, provided funding acquisition, and critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Song, J., Ouyang, P. et al. Multi-scale Wavelet-Mamba framework for spatiotemporal traffic forecasting. Sci Rep 15, 45594 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29223-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29223-8