Abstract

This study presents a novel control strategy for the regulation of engine speed in nonlinear four-cylinder spark ignition (SI) engines by integrating a proportional–integral–derivative controller with a filter (PID-F) tuned using the flood algorithm (FLA). The approach leverages the dual-phase exploration and exploitation mechanism of FLA to determine optimal controller parameters efficiently, addressing the nonlinear and time-varying behavior of SI engines. A modified objective function is formulated to penalize overshoot and cumulative tracking error simultaneously, ensuring rapid transient response and precise steady-state accuracy. The proposed control framework is modeled and validated in MATLAB/Simulink and benchmarked against existing tuning techniques, including the Simulink PID tuner and selected metaheuristic optimizers such as the whale optimization algorithm, sinh-cosh optimizer, and cuckoo search. Comparative analyses demonstrate the superiority of the FLA-optimized PID-F controller in achieving stable, robust, and noise-resilient speed regulation under varying load and disturbance conditions. The findings establish the FLA as an efficient and scalable optimization tool for real-time controller tuning in automotive applications, contributing to a practical and computationally efficient solution for advanced engine control systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spark ignition (SI) engines remain an integral part of various industries due to their versatility, reliability, and cost-effectiveness1. Predominantly used in automobiles, motorcycles, power tools, small aircraft, boats, and lawn equipment, SI engines offer a high power-to-weight ratio, faster acceleration, and smoother operation compared to their diesel counterparts1. The widespread availability of gasoline and the relative simplicity of the engine design also make them the preferred option for light-duty applications2. With the growing demand for efficiency and lower emissions, optimizing the performance of SI engines has become increasingly important.

A key aspect of SI engine performance is speed control. Maintaining a stable engine speed ensures fuel efficiency, reduces emissions, and prevents engine wear. However, SI engine speed control is a challenging task due to the nonlinear behavior of the engine dynamics, time-varying parameters, and sensitivity to load disturbances3. These challenges make it difficult to design a robust control system that can adapt to various operating conditions. Poor speed control can lead to engine instability, excessive fuel consumption, and suboptimal performance, making it critical to develop optimized control strategies4.

Literature review

Numerous control strategies have been developed to address the complexity of spark ignition (SI) engine speed control, given the nonlinearities, uncertainties, and dynamic behaviors inherent in these systems. In the literature, advanced robust control methods such as H-infinity control5, linear quadratic regulator (LQR)6, and model predictive control (MPC)7 have been explored extensively. These methods are recognized for their ability to handle system uncertainties, disturbances, and nonlinear characteristics, which are crucial for maintaining optimal engine performance. H-infinity control offers a systematic approach to manage system robustness, while LQR provides an optimal feedback mechanism to minimize a cost function related to engine dynamics. Meanwhile, MPC has gained prominence due to its predictive capability and constraint-handling features, making it particularly useful for applications where precise control is required. Despite their robustness and adaptability, these advanced controllers often involve complex mathematical formulations and significant computational overhead, posing challenges in real-time implementation. In addition, sliding mode control (SMC) and adaptive control techniques have also been utilized to address the nonlinearities and time-varying behaviors characteristic of SI engines8. SMC, with its inherent robustness, can effectively mitigate disturbances and maintain stability. However, the chattering phenomenon, which is prevalent in SMC, can lead to excessive wear in mechanical components. Similarly, adaptive control methods, which adjust controller parameters in real time based on system feedback, are adept at handling time-varying system dynamics. Nonetheless, the real-time computational burden associated with these adaptive strategies can complicate their practical deployment in resource-constrained environments.

In contrast, proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controllers9,10 and their variants, such as fuzzy adaptive PID11,12, fractional order PID (FOPID)13 and PID with filters14, multi resolution (MRPID)15,16 are widely adopted in industrial applications due to their simplicity, ease of implementation, and low computational requirements17,18. PID controllers are valued for their ability to provide balanced performance across a wide range of operating conditions. While variants such as FOPID extend the capabilities of traditional PID controllers by introducing fractional calculus, they also come with added complexity in both design and implementation. The FOPID controller requires the determination of additional parameters (the fractional orders of the integral and derivative actions), making the tuning process more intricate. Furthermore, the computational load associated with fractional-order control can become significant, especially in real-time applications where rapid responses are crucial. These limitations often hinder the practical application of FOPID in systems with stringent performance and computational constraints. In contrast, the PID with filters, as proposed in this study, offers an effective balance between enhanced noise attenuation and computational simplicity, making it particularly suitable for spark ignition engine speed control. However, their effectiveness heavily depends on the precise tuning of the proportional, integral, and derivative gains. Improper tuning can result in undesired outcomes such as excessive overshoot, persistent steady-state error, and slow transient responses. Therefore, the challenge lies in determining the optimal PID parameters to meet the specific dynamic requirements of complex systems like SI engines.

Several methodologies have been developed for PID tuning. Traditional methods such as Ziegler-Nichols19, Cohen-Coon20 and internal model control21 provide initial estimates for PID parameters. However, these methods often fall short in addressing the complexities of nonlinear systems such as spark ignition engines. For example, Ziegler-Nichols assumes a linear system response, which is rarely valid in highly nonlinear environments. This oversimplification can lead to excessive overshoot, poor transient responses, and inadequate disturbance rejection under dynamic operating conditions. Similarly, the Cohen-Coon method, while more robust in certain cases, struggles to handle time-varying dynamics and external disturbances, necessitating frequent manual recalibration. Techniques like root locus22 and Lyapunov stability23 have been applied to ensure system stability, but these are limited in handling nonlinearity and time-varying conditions. In addition, the design and optimization of PID controllers within Simulink environments have been greatly improved by leveraging automated tools and techniques, offering a strong foundation for the implementation of the proposed methodology24. Nonetheless, despite these advancements, various methods may still face constraints when applied to complex or time-sensitive systems, where both rapid convergence and precise accuracy are essential.

With the growing demand for optimized performance, metaheuristic algorithms have gained prominence in tuning PID controllers due to their ability to efficiently navigate complex solution spaces and address nonlinearities. Methods such as the whale optimization algorithm (WOA)25,26,27, cuckoo search algorithm (CS)28, sinh-cosh optimizer (SCHO)29, electric eel foraging optimizer (EEFO)30, and the grey wolf optimizer (GWO)31 provide flexible approaches for finding near-optimal control parameters in complex systems like spark ignition engines. These algorithms are widely adopted because they balance exploration and exploitation, often leading to superior performance compared to traditional tuning methods. However, these metaheuristic algorithms are not without their limitations. For example, metaheuristic algorithms such as WOA and GWO have shown significant promise in addressing nonlinearities and complexities in PID tuning. However, WOA often experiences slower convergence in intricate solution spaces due to its heavy reliance on exploitation in later stages of optimization. This can result in suboptimal solutions, especially when the search space is highly complex32. GWO, while effective in balancing exploration and exploitation, can suffer from local optima trapping and lacks the robustness required for real-time applications in highly dynamic environments. Both methods also involve computational overheads, particularly when applied to systems requiring rapid adaptability, which limits their practical use in real-time spark ignition engine speed control32. Similarly, CS and SCHO, while effective in certain contexts, may lack the precision needed for fine-tuning control parameters, often requiring substantial computational resources to reach an optimal solution28. Although EEFO has shown robustness in some applications, it occasionally suffers from premature convergence and a lack of diversity in the solution space, limiting its adaptability in dynamic, nonlinear systems30.

Given these challenges, the proposed study focuses on the flood algorithm (FLA) for optimizing the controller parameters. Unlike the aforementioned algorithms, FLA has shown particular effectiveness in avoiding local optima by maintaining a balanced search mechanism between exploration and exploitation33. This approach allows FLA to systematically explore the solution space, ensuring rapid convergence without falling into premature stagnation. Moreover, FLA’s computational efficiency makes it particularly suited for real-time control applications where resource constraints are critical33. In practical applications such as spark ignition engine control, the optimization process must not only be efficient but also capable of providing solutions within strict time limits. To ensure this, FLA’s computational efficiency can be enhanced by using techniques such as reducing the search space to focus on the most influential parameters, minimizing the number of iterations through adaptive stopping criteria, and utilizing parallel computing. These strategies ensure that the optimization process can meet real-time response requirements while maintaining solution quality. Additionally, since the objective function has been modified in this study, the computational cost per iteration may vary depending on the complexity of the modified function. While the number of iterations remains consistent, the computational burden could increase as the problem size or the complexity of the objective function increases. Future studies could investigate how this modified FLA performs with larger problem sizes to assess its scalability in more complex systems.

Research gap and motivation

Various studies have explored different control strategies for spark ignition engine speed control, focusing on robustness, stability, and optimization techniques. However, the following gaps are identified in the existing literature:

-

While robust controllers like H-infinity and MPC have been extensively studied, many approaches have focused on a specific subset of operating conditions rather than a comprehensive analysis across varying loads and environmental conditions.

-

Comparative analyses of the results obtained from different controller designs and optimization techniques are limited in scope, making it difficult to assess their relative effectiveness under diverse conditions.

-

Tuning methodologies for PID controllers have been widely explored, but there is a lack of focus on applying metaheuristic algorithms like the flood algorithm to spark ignition engines. Most studies rely on traditional methods that may not provide optimal performance in complex, nonlinear systems.

-

The effect of overshoot and steady-state error in SI engine speed control has not been extensively addressed. Many existing approaches focus on system stability but overlook critical performance metrics such as overshoot minimization and damping speed.

-

There is limited exploration of the potential of combining modified objective functions with advanced optimization techniques to improve the transient response and steady-state behavior of SI engine speed control systems.

Motivated by these gaps, we propose a novel approach that incorporates the flood algorithm for the optimal tuning of PID controllers in spark ignition engine speed control. By employing a modified objective function, we aim to minimize overshoot, reduce steady-state errors, and achieve rapid damping, ensuring superior performance under varying load and environmental conditions.

Contribution and paper organization

The novelty of this research lies in the introduction of the FLA for the optimal tuning of a PID-F controller applied to the nonlinear spark-ignition engine speed control problem which is an area where FLA has not previously been employed. In addition, a customized objective function has been formulated to penalize both overshoot and cumulative tracking error, ensuring a well-balanced transient and steady-state response. This formulation differs from traditional integral error-based indices by directly incorporating an overshoot term that improves dynamic smoothness and damping. The proposed combination of the FLA optimizer with the PID-F architecture thus represents a novel and computationally efficient framework for achieving noise-resilient and robust speed regulation in spark ignition engines. The contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

-

A novel performance-optimized controller design is proposed for PID with a filter for spark ignition engine speed control, utilizing the FLA for the first time.

-

The application of FLA with a modified objective function in this study allows for significant improvements in performance, including minimized overshoot, reduced steady-state errors, and enhanced system damping. These attributes make FLA especially advantageous for complex, nonlinear systems like spark ignition engines, where traditional methods and other metaheuristic algorithms often struggle to provide consistently optimal results.

-

The proposed controller design is validated through simulations and compared with other optimization techniques such as SCHO, WOA, CS and Simulink PID Tuner.

-

The paper presents a comprehensive analysis of the controller’s robustness across varying operating conditions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 provides an overview of the FLA, detailing its structure and optimization process. Section 3 covers the design of the PID with filter controller, explaining its role in system stability and control. Section 4 focuses on the modeling of the four-cylinder spark ignition engine speed control system, outlining the key parameters and system dynamics. Section 5 introduces the novel control methodology proposed in this study. Section 6 verifies the statistical performance of the FLA. Section 7 presents the comparative nonlinear simulation results, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed controller. Finally, Sect. 8 concludes the paper, summarizing the key findings and suggesting directions for future research.

Overview of flood algorithm

The flood algorithm is a novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithm inspired by the natural phenomena of flooding and water flow in river basins. It simulates the dynamic, often chaotic, behavior of water during flood events to address complex optimization problems. This approach is particularly effective in solving nonlinear and multi-modal problems, such as tuning the parameters of PID controllers in systems requiring high precision and adaptability. By mimicking the unpredictable but systematic movements of water masses, FLA provides a robust framework for both global exploration and local exploitation, leading to the discovery of optimal solutions.

Mathematical modeling of FLA

FLA operates through two primary phases: the regular movement phase and the flooding phase33. These phases are mathematically modeled to guide the search for optimal solutions effectively. Firstly, in the regular movement phase for phase 1, the population of potential solutions is directed toward the best-known solution at each iteration, similar to how water naturally flows toward the lowest point in a landscape. The position update rule for each solution is described by the following equation:

where \(\:{S}_{new}^{i}\) represents the updated position of the \(\:it\:\)solution, \(\:{S}_{best}\) denotes the best solution discovered thus far, \(\:{S}^{j}\) refers to a randomly chosen solution and \(\:rand\) is a random number ranging from 0 to 1. This formulation directs the solutions toward the current optimal solution while preserving diversity within the population.

Secondly, in the flooding phase for phase 2, random disturbances are introduced to escape local optima and explore new regions of the search space. The likelihood of a flood event is governed by the water depletion coefficient, \(\:{P}_{k}\), which gradually decreases over time as the algorithm approaches convergence. The water depletion coefficient is expressed as:

where \(\:Iter\) represents the current iteration number and \(\:{Iter}_{max}\) is the maximum number of iterations allowed. During a flood, the positions of the solutions are updated to simulate the turbulent movement of water masses, as shown in the following equation:

where \(\:randn\) represents a normally distributed random number that introduces stochasticity into the search process, \(\:{P}_{k}\) controls the intensity of the disturbance based on the current iteration. This phase introduces randomness into the search, allowing for a broader exploration of the solution space and helping the algorithm escape local optima.

As the algorithm progresses, it models the effect of soil permeability, which influences the likelihood of a flood. The flood probability \(\:{P}_{flood}\) is calculated based on the cost function values, with better solutions corresponding to lower permeability and thus reducing water loss. This relationship is expressed as:

where \(\:{f}_{min}\) is the best cost function value found so far, \(\:{f}_{max}\) is the worst cost function value found so far. The flood probability reflects the algorithm’s ability to maintain diversity while converging toward the global optimum.

FLA continuously alternates between the regular movement and flooding phases, striking a balance between exploration (searching for new solutions) and exploitation (refining existing solutions). Weaker solutions are discarded over time, while stronger solutions are retained and new ones are introduced, mimicking the natural rise and fall of water levels in a river basin. This iterative process enables FLA to efficiently navigate the search space, ensuring that the algorithm does not become trapped in local optima and that it converges toward global solutions. To provide better appreciation, related notations of FLA, an additional table can be found under notations section.

PID with filter controller

The PID controller is a fundamental control strategy extensively utilized in various industrial and engineering applications due to its simplicity and effectiveness in handling different dynamic systems34. However, in real-world scenarios, the derivative action in a conventional PID controller can be highly sensitive to high-frequency noise, which may result in instability and oscillations. To address this issue, a PID with filter (PID-F) controller is employed, where a low-pass filter is incorporated into the derivative term35. This filtering reduces noise sensitivity, enhancing the controller’s performance and stability. The transfer function of the PID with filter controller can be expressed in Eq. (5).

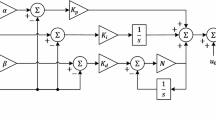

where \(\:{K}_{P}\) is the proportional gain, influencing the system’s responsiveness to errors, \(\:{K}_{I}\) is the integral gain, which eliminates steady-state errors by accounting for the accumulation of past errors,\(\:\:{K}_{D}\) is the derivative gain, improving system stability by predicting future errors, \(\:\eta\:\) is the filter coefficient, which controls the high-frequency noise attenuation in the derivative action, \(\:s\) is the Laplace variable. By integrating the filter term \(\:\eta\:s/\left(s+\eta\:\right)\) into the derivative component, the controller effectively suppresses high-frequency noise, enhancing system performance. This modification maintains the beneficial effects of derivative control in improving transient response while mitigating issues related to noise amplification and instability. As can be seen in Fig. 1, it is presented the block diagram of a feedback control system utilizing a PID-F controller. In this control loop, the system’s objective is to minimize the error between the desired setpoint (reference input) and the actual system output. The PID-F controller processes this error and generates a control signal to drive the system toward the setpoint. By using the PID-F controller, the feedback system achieves a more stable and robust performance, especially in environments with high noise levels or rapid fluctuations. The incorporation of the filter within the derivative term allows for improved noise rejection and a more reliable control response, leading to faster convergence to the desired setpoint while minimizing oscillations as shown in Sect. 6.

Modeling of four-cylinder spark ignition engine speed control system

The speed control system of a nonlinear four-cylinder spark ignition engine can be effectively modeled by considering the rotational dynamics of the engine, air-fuel mixture dynamics, and throttle response24,36. These components are key to accurately representing the engine’s behavior and designing an appropriate control strategy. The system is modeled and simulated in MATLAB/Simulink to evaluate its dynamic behavior under the control of the PID-F controller. The air mass flow through the throttle is modeled using the choked flow equation as shown in Eq. (6).

where \(\:{\dot{m}}_{air}\) is the air mass flow rate, \(\:{A}_{th}\) is the effective throttle area (nonlinear function of throttle position),\(\:\:R\) is the gas constant. \(\:{p}_{a}\) and \(\:{T}_{a}\) are the ambient pressure and temperature, respectively. Assuming the isothermal conditions, the dynamics of the intake manifold pressure can be expressed in Eq. (7).

where \(\:{T}_{m}\) is the manifold temperature, \(\:{V}_{m}\) is the manifold volume and \(\:{\dot{m}}_{intake}\) is the air mass flow rate entering the engine. Then, the mean value of the fuel-air mixture entering the engine cylinders is approximated as:

where \(\:{\eta\:}_{v}\) is the volumetric efficiency, \(\:{V}_{d}\) engine displacement volume and \(\:{\omega\:}_{eng}\) is the engine speed in rad/s.\(\:\:{\dot{m}}_{intake}={\dot{m}}_{mix}/(1+{\Phi\:}{(F+A)}_{s})\), where \(\:{(F+A)}_{s}\) represents the stoichiometric fuel to air ratio and \(\:{\Phi\:}\) is the fuel to air ratio normalized by the stoichiometric fuel to air ratio, also known as the equivalence ratio. Typically, the generated engine torque (\(\:{T}_{engine}\)) depends nonlinearly on the engine speed, the mass flow rate into the cylinders, the equivalence ratio and the spark advance as shown in Eq. (9).

Lastly, the rotational dynamics of the engine’ speed are modeled as shown in Eq. (10).

where \(\:J\) is the engine’s moment of inertia, \(\:{\omega\:}_{eng}\left(t\right)\) is the angular velocity (engine speed), \(\:{T}_{engine}\left(t\right)\) is the engine torque, and \(\:{T}_{load}\left(t\right)\) is the load torque. This equation describes how the engine speed changes in response to the difference between the engine’s generated torque and the load torque, considering the rotational inertia and frictional effects. By integrating the equations for engine speed dynamics, air-fuel torque generation and throttle dynamics, a comprehensive model of the engine speed control system can be formulated.

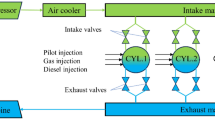

The above mathematical model forms the basis of the Simulink model depicted in Fig. 2, which integrates the engine dynamics with the PID-F controller optimized through FLA. As shown within the respective figure, the system begins with a speed reference input, which defines the desired engine speed. The error signal, calculated as the difference between the actual engine speed and the reference, is processed by the PID-F controller to generate a control signal (\(\:U\left(s\right)\)). This signal adjusts the throttle area, directly influencing the airflow into the engine manifold and the air charge. The air charge is then delayed during the induction to power stroke process, after which it contributes to the combustion stage, where the engine torque is generated based on the engine speed (\(\:N\)) and air charge. The generated torque is then combined with load and engine torque in the vehicle dynamics block to model the rotational behavior of the engine. External disturbances and noise are introduced to the system to simulate real-world operational challenges and evaluate the controller’s robustness.

The feedback loop ensures continuous adjustment of the control signal to minimize the error and maintain the desired speed, ensuring stability and adaptability across varying conditions. This diagram comprehensively depicts the interactions between the control and physical subsystems, emphasizing the PID-F controller’s role in achieving accurate and robust speed regulation. The initial design of the control system was carried out using the Simulink PID tuner37. This tuning process provided a set of preliminary control parameters to analyze the system’s response.

Figure 3 shows the time response of the engine speed obtained with the Simulink PID tuner. In the figure, the red dashed line represents the reference speed, while the blue line depicts the engine’s speed response under the PID-F controller designed by the tuner. The response analysis reveals that the system exhibits a normalized percent overshoot of \(\:12.3712\%\) and a normalized settling time of \(\:3.9817\:s\). Although these results indicate that the system achieves a reasonable level of performance, there remains room for enhancement in terms of both reducing the overshoot and shortening the settling time. To further optimize the system’s dynamic performance, the next phase of this study aims to develop an improved control strategy. By refining the PID-F controller design, the objective is to achieve a more responsive and stable engine speed control system, thereby minimizing deviations from the desired speed reference and enhancing overall performance.

Novel control methodology

A novel control methodology is proposed to enhance the dynamic performance of the four-cylinder spark ignition engine speed control system. The new approach involves optimizing the controller parameters using a customized objective function designed to minimize both overshoot and steady-state errors, thereby achieving rapid damping and improved system stability. The proposed objective function is defined in Eq. (11) below.

where \(\:{t}_{final}\)=50 s, \(\:{N}_{os}\) represents the normalized percent overshoot, \(\:{\upphi\:}\) is the balancing coefficient, set to 0.02 in this study, \(\:e\left(t\right)\) denotes the error between the reference input and the system output over time. This objective function effectively balances the trade-off between minimizing overshoot (\(\:{N}_{os}\)) and reducing the total error (\(\:\underset{0}{\overset{{t}_{final}}{\int\:}}\left|e\right(t\left)\right|dt\)), ensuring a more stable and efficient control response. The coefficient \(\:{\upphi\:}\) allows for flexibility in emphasizing either the overshoot minimization or the error reduction, depending on the system’s requirements. The parameter tuning for the PID-F controller is carried out under the following constraints: \(\:0.001\le\:{K}_{P}\le\:0.1\), \(\:0.001\le\:{K}_{I}\le\:0.1\), \(\:0.0005\le\:{K}_{D}\le\:0.005\) and \(\:100\le\:\eta\:\le\:2000\). The upper and lower bounds for the PID controller parameters were chosen based on the system’s dynamic behavior, particularly the spark ignition engine’s response characteristics. Wider bounds were chosen to allow the algorithm sufficient flexibility in exploring a range of possible solutions and to avoid local optima; however, this choice increases the computational burden, as the larger search space requires more iterations to converge to an optimal solution. Narrower bounds would speed up the optimization process but could limit the system’s ability to find an optimal set of parameters, especially in complex systems with nonlinear behavior. Therefore, the current bounds represent a compromise between ensuring accurate optimization and keeping the computational cost manageable for real-time applications. Unlike conventional indices such as the integral of time-weighted absolute error (ITAE) or the integral of squared error (ISE), the proposed objective function explicitly incorporates both the normalized overshoot and the cumulative absolute error terms to control the transient and steady-state behaviors simultaneously. This formulation allows the optimizer to directly minimize overshoot while ensuring sustained error reduction throughout the response. The balancing coefficient was selected after empirical evaluation to achieve an optimal trade-off between response speed and stability. Larger values of \(\:{\upphi\:}\) were observed to accelerate convergence but introduced slight oscillations, whereas smaller values improved damping at the cost of slower response. Therefore, the chosen weighting ensures a smooth transient performance with minimal overshoot and negligible steady-state deviation, aligning with the nonlinear and time-varying characteristics of spark-ignition engine dynamics.

The optimization process utilizes the FLA mechanism, with a flood swarm size (\(\:{N}_{pop}\)) of 30, performing 25 runs and a maximum iteration number (\(\:{Iter}_{max}\)) of 50 to ensure a comprehensive search for the optimal controller parameters. Figure 4 illustrates the comprehensive workflow of the FLA applied to optimize the PID-F controller parameters for the spark ignition engine speed control system. The process begins with the initialization of the swarm and its parameters, where candidate solutions (representing PID-F parameters) are assigned randomly within predefined bounds. The engine speed control system, modeled as a four-cylinder spark ignition engine, receives these parameters and computes the control signal based on the error between the speed reference and the actual engine speed. The generated control signal adjusts the throttle angle, influencing the engine dynamics and generating an objective function value for each candidate.

The core of the FLA optimization process is depicted in the loop, where the swarm members are iteratively updated. Each candidate solution is evaluated based on the objective function, aiming to minimize key performance metrics such as overshoot, rise time, and steady-state error. The FLA mechanism updates the swarm by comparing the costs (objective function values) of the current and newly generated members. If a newly added member outperforms an existing one or even the best-performing member, their positions are exchanged to refine the solution space. This dynamic adjustment helps the algorithm balance exploration and exploitation, avoiding local optima. The process continues until the stopping criterion is met, such as reaching the maximum number of iterations or achieving a satisfactory convergence rate. Once the loop ends, the best-performing solution and its corresponding PID-F parameters are reported. This flowchart highlights how the FLA systematically optimizes the controller’s parameters through iterative refinement and adaptive exploration, ensuring robust performance in the engine speed control system.

Verification of the statistical performance of FLA

This section provides a detailed statistical analysis of the proposed FLA by comparing its performance with other optimization algorithms, namely the SCHO, WOA, and CS. The evaluation is conducted through various statistical metrics and non-parametric tests to demonstrate the effectiveness of the FLA in achieving optimal control performance.

Compared algorithms

To verify the effectiveness of FLA, a comparative analysis is performed against SCHO, WOA, and CS algorithms. Table 1 outlines the parameter settings for each algorithm used in the comparison. In all cases, the maximum number of iterations (\(\:{Iter}_{max}\)) is set to 50, and the population size (\(\:Npop\)) is fixed at 30. These parameters were chosen based on extensive simulations to ensure a balance between computational efficiency and solution quality. It is worth noting that reducing the population size or the number of iterations could shorten the computation time. However, this would likely result in a decrease in the quality of the solution, potentially leading to suboptimal control performance. Therefore, the selected settings represent a trade-off that was found to provide optimal parameter tuning for the PID-F controller within the simulated environment.

The SCHO, WOA, and CS were selected as benchmark algorithms based on their proven efficiency, stable convergence, and successful implementation across a wide range of control-engineering and optimization problems. Although several newer metaheuristics exist, these methods remain among the most reliable and computationally efficient frameworks for fair benchmarking. Their inclusion ensures a balanced comparison, highlighting the advantages of the proposed FLA in terms of convergence behavior, robustness, and solution accuracy within a similar computational budget.

Statistical metrics and wilcoxon’s test

To thoroughly assess the performance of the algorithms, several statistical metrics, including the best, worst, average, standard deviation (SD), and median values of the objective function, are calculated and presented in Table 2. The results indicate that FLA achieves the lowest values for all metrics, highlighting its superior optimization capability. Furthermore, to determine the statistical significance of the performance differences, the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test is employed. This test is used to compare paired samples and identify whether there is a significant difference in their distributions. It is particularly useful when the data do not necessarily follow a normal distribution, making it ideal for the performance comparison of optimization algorithms38.

Table 3 presents the p-values obtained from the comparison of FLA with SCHO, WOA, and CS. The results indicate that FLA outperforms the other algorithms with statistically significant differences. The p-values are less than 0.05, which is the commonly accepted threshold for statistical significance39. This implies that the observed differences in performance are unlikely to have occurred by chance, confirming that FLA is the most effective algorithm in this study.

Boxplot analysis

The box-plot comparison of objective function values obtained using the FLA, SCHO, WOA, and CS are shown in Fig. 5. The boxplots illustrate the distribution of objective function values across multiple runs for each algorithm, providing a visual comparison of their performance and robustness. The red line in each box indicates the median value, representing the central tendency of the results, while the blue box spans the interquartile range, capturing the variability of the middle 50% of the data. The whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values within 1.5 times the interquartile range, highlighting the spread and consistency of the solutions. The lower median and narrower interquartile range observed for the FLA in Fig. 5 can be attributed to its robust optimization mechanism. FLA’s dual-phase approach (combining directed search during the regular movement phase and stochastic exploration during the flooding phase) allows the algorithm to consistently identify near-optimal solutions while avoiding local optima. This balance between exploration and exploitation reduces variability in the optimization results across multiple runs. Furthermore, FLA’s adaptive strategies, such as the use of a convergence-based stopping criterion, ensure that the algorithm efficiently terminates once the solution stabilizes. These features collectively contribute to the narrower interquartile range, indicating high consistency in the objective function values, and a lower median, reflecting superior optimization performance. By contrast, other algorithms, such as WOA and CS, often exhibit wider interquartile ranges due to their reliance on less adaptive exploration strategies, which may lead to suboptimal convergence in some runs. These statistical metrics collectively highlight the robustness of FLA in consistently identifying optimal or near-optimal solutions across diverse problem instances, reinforcing its suitability for dynamic and complex optimization tasks.

Convergence analysis

The convergence curves behavior of each algorithm is analyzed to assess their optimization efficiency over iterations. Figure 6 displays the convergence curves of FLA, SCHO, WOA, and CS, plotting the objective function value against the iteration number. The respective plot demonstrates a rapid initial decline in the objective function, followed by gradual stabilization as the algorithm approaches the optimal solution.

The adaptive stopping criterion effectively identifies this stabilization phase and terminates the optimization process early, as indicated by the plateau in the convergence curve. This reduces computational overhead while preserving the quality of the obtained solution. It is evident from the figure that FLA converges to the lowest objective function value compared to the other algorithms, demonstrating its ability to find the better optimal solution.

Computational runtime and real-time feasibility

To assess the computational efficiency of the compared algorithms, average runtimes were measured across 25 independent executions under identical simulation conditions. The average computation times were 639.43 s for FLA, 880.15 s for SCHO, 767.80 s for WOA, and 949.49 s for CS. These results demonstrate that the proposed FLA achieves the shortest computation time, operating approximately 27% faster than SCHO, 17% faster than WOA, and 33% faster than CS. The efficiency gain primarily arises from FLA’s dual-phase search structure and adaptive flood probability, which prevent unnecessary function evaluations and facilitate rapid convergence.

In practical terms, the optimization is performed offline to determine the optimal controller gains, while the online control stage relies solely on the tuned PID-F structure. Consequently, the computational demand during real-time execution is minimal and equivalent to that of a conventional PID controller. This ensures full compatibility with existing automotive electronic control units (ECUs), which typically operate with control-loop sampling times on the order of milliseconds. Given its low-complexity implementation and potential for parallelization, the proposed FLA-based tuning framework is thus entirely feasible for real-time deployment in embedded engine-control systems.

Comparative nonlinear simulation results

This section presents a comprehensive comparison of the nonlinear simulation results obtained using various optimization algorithms, including the FLA, SCHO, WOA, CS and the Simulink PID tuner. The performance is evaluated in terms of closed-loop response, steady-state error, reference tracking, disturbance rejection, noise attenuation and error-integral performance metrics.

Closed-loop response

The parameters obtained through different optimization algorithms are summarized in Table 4. The table lists the proportional (\(\:{K}_{P}\)), integral (\(\:{K}_{I}\)), derivative (\(\:{K}_{D}\)), and filter (\(\:\eta\:\)) parameters for each method: FLA, SCHO, WOA, CS, and the Simulink PID tuner. On the other hand, Fig. 7 shows the time response of the engine speed for the different algorithms with a reference speed of 3000 rpm. Among the results, the FLA-based control provides the best response, closely tracking the reference speed with minimal deviation. In contrast, the Simulink PID tuner yields the worst performance, with significant deviations from the desired speed. To provide a clearer comparison, Fig. 8 offers a zoomed view of the time response around critical points, highlighting the differences in performance between the algorithms.

It is important to note that the parameters obtained from the Simulink PID Tuner were derived directly from the automatic tuning process without any additional user-assisted adjustments. The tuner’s built-in algorithm first linearizes the system model and then automatically computes the proportional, integral, derivative, and filter coefficients. To maintain reproducibility and objectivity, no manual fine-tuning or heuristic correction was applied to these parameters. Although several user-assisted trials were conducted for verification, the resulting performance did not surpass the default auto-tuned configuration. Therefore, the results presented in this study correspond strictly to the default parameters provided by the Simulink PID Tuner, ensuring a transparent and fair comparison with the proposed FLA–based PID-F controller.

Zoomed view of Fig. 7.

As can be seen in Table 5, it is compared the normalized overshoot percent (\(\:{N}_{os}\) (%)), normalized rise time (\(\:{N}_{rise}\) (s)) and normalized settling time (\(\:{N}_{set}\) (s)) (within a ± 2% tolerance band) for each method. The FLA-based control is the only approach that achieves zero overshoot, indicating a highly stable response. Additionally, the rise time and settling time for FLA are considerably lower than those of the other algorithms, further demonstrating its superior dynamic performance.

It should be noted that the overshoot, rise-time, and settling-time metrics presented in Table 5 are reported in normalized percentage form for consistency across all comparative methods. The corresponding actual peak engine speeds were 3000.0000 rpm (FLA), 3000.1355 rpm (SCHO), 3000.2579 rpm (WOA), and 3000.7962 rpm (CS) for a 3000 rpm reference. These values confirm that the small percentage overshoots are genuine results of the controller precision and not artifacts of normalization. The use of a high-resolution simulation environment and precise solver configuration further ensured that the computed performance indices accurately reflect the system’s transient dynamics.

Steady-state error

The steady-state error is a critical parameter for evaluating the accuracy of a control system in tracking a reference input over time. Figure 9 illustrates the engine speed response for different control algorithms over a 50-second simulation, compared to the reference speed of 3000 rpm. The figure highlights how each algorithm performs in minimizing the steady-state error, especially as the system settles. At the end of the simulation (\(\:{t}_{final}=50\) second), the steady-state errors for each control method are calculated as follows FLA: 9.3439\(\:\times\:{10}^{-7}\) rpm, SCHO: 2.6014\(\:\times\:{10}^{-5}\) rpm, WOA: 1.6640\(\:\times\:{10}^{-5}\) rpm, CS: 3.2858\(\:\times\:{10}^{-6}\) rpm and Simulink PID Tuner: 0.1839 rpm.

The results indicate that the FLA-based controller achieves the smallest steady-state error, almost reaching zero, which demonstrates its exceptional precision in maintaining the desired engine speed. In contrast, the Simulink PID tuner exhibits a significantly larger steady-state error, as evidenced by the noticeable oscillations in its response in Fig. 9. These oscillations around the reference speed highlight the inability of the PID tuner to consistently track the target value. The markedly lower steady-state error produced by the FLA-based controller underscores its superior capability in ensuring accurate speed regulation. This finding emphasizes the effectiveness of using FLA for parameter optimization in PID-F control, enabling the system to maintain the desired speed with minimal deviation.

Reference tracking

Figure 10 presents the reference-tracking performance of the proposed FLA-based PID-F controller when subjected to multiple step-wise changes in the engine speed reference. The simulation evaluates how effectively the controller adapts to different operational points, reflecting realistic variations in driver demand or load conditions. As seen in the figure, the controller output (solid blue line) closely follows the desired reference trajectory (dashed red line) across all transitions. During the initial acceleration phase, the engine speed rapidly rises from 2000 rpm to 3000 rpm with a smooth transient and no observable overshoot, indicating well-damped system behavior. When the reference decreases sharply to 1500 rpm at around 10 s, the controller promptly adjusts without oscillation or delay, maintaining stable convergence toward the new setpoint. A subsequent increase to 2500 rpm at 20 s is also tracked accurately, demonstrating consistent performance across both acceleration and deceleration phases.

This behavior confirms the strong adaptability and robustness of the FLA-tuned controller in handling abrupt reference variations while preserving smooth and precise control. The absence of overshoot and steady-state error across all reference levels reflects the controller’s ability to maintain dynamic balance between responsiveness and stability. Such characteristics are essential for real-world engine management systems, where the control input must continuously adapt to rapid changes in throttle position, load, and environmental conditions without compromising efficiency or smoothness.

Disturbance rejection and noise attenuation

Figure 11 illustrates the disturbance-rejection and noise-attenuation capability of the proposed FLA-based PID-F controller through four subplots, each highlighting a specific aspect of the system’s dynamic response under realistic operating perturbations. In the first subplot, the overall engine-speed response is shown under the combined influence of disturbances and noise. The controlled output follows the reference command closely, exhibiting a smooth transient behavior and negligible steady-state error. Even after the introduction of external disturbances, the engine speed quickly returns to the reference value, confirming the controller’s strong resilience and effective rejection of undesired deviations.

The second subplot depicts the reference input profile, where the desired engine speed transitions from 2000 rpm to 3000 rpm. This step-wise change represents a typical acceleration phase in real driving conditions. The FLA-based control strategy responds promptly to this change, maintaining stable convergence and ensuring that the actual engine speed aligns with the reference trajectory throughout the transient period. The third subplot displays the disturbance signal applied at approximately 10 s, representing a sudden torque disturbance equivalent to 5–10% of the nominal operating range (0 to − 200 rpm). Following this injection, only minor and short-lived fluctuations are observed in the engine speed response. The controller swiftly compensates for the disturbance and re-establishes the reference speed without overshoot or oscillation. This behavior highlights the algorithm’s strong disturbance-rejection ability and its capability to sustain smooth operation even under abrupt load variations. The fourth subplot presents the noise input, varying randomly between − 1 rpm and + 1 rpm to emulate sensor and measurement noise. Despite these continuous fluctuations, the control output remains exceptionally stable, indicating that the incorporated derivative filter and optimized gain structure effectively suppress noise propagation into the system output. This noise-attenuation characteristic is particularly valuable in practical engine-control applications, where sensor imperfections and electrical interference are unavoidable. Overall, Fig. 11 demonstrates that the proposed FLA-tuned PID-F controller possesses a high degree of robustness against both transient disturbances and persistent noise. Its ability to maintain smooth, accurate, and stable performance under such conditions underscores its suitability for real-world engine-speed regulation, where operating environments are frequently affected by unpredictable external and internal perturbations.

Error-based performance indexes

To comprehensively evaluate the control performance of the proposed FLA optimized PID-F controller, four error-integral performance indexes are employed: Integral Absolute Error (IAE), Integral Squared Error (ISE), Integral Time Absolute Error (ITAE), and Integral Time Squared Error (ITSE). These metrics provide insights into how effectively the control system minimizes errors over time38,40. The equation for IAE performance index is defined in Eq. (12).

IAE measures the total absolute error over the duration of the simulation. Lower IAE values indicate better overall performance in minimizing errors throughout the control process. The equation for ISE performance index is defined in Eq. (13).

ISE emphasizes larger errors due to the squaring term, making it useful for identifying systems that can effectively reduce significant deviations from the setpoint. A smaller ISE value signifies better control accuracy and robustness. The equation for ITAE performance index is defined in Eq. (14).

ITAE gives more weight to errors occurring later in the process, penalizing slower responses. Lower ITAE values reflect faster error correction and improved system response over time. The equation for ITSE performance index is defined in Eq. (15).

Similar to ITAE, ITSE places greater emphasis on errors that persist over time, but it focuses more on larger errors due to the squared term. A smaller ITSE value indicates the controller’s effectiveness in rapidly reducing both the magnitude and duration of errors. Table 6 presents the values of these performance indexes obtained for the FLA-optimized controller, as well as the other algorithms (SCHO, WOA, CS, and Simulink PID tuner). The results clearly show that the FLA-based control method achieves the lowest values across all four metrics, highlighting its superior ability to minimize error, respond promptly, and maintain system stability.

Conclusion and future work

This study presented a comprehensive control framework for regulating the speed of a nonlinear four-cylinder spark ignition engine using a FLA–optimized PID-F. The proposed methodology introduced the FLA as a novel metaheuristic optimizer for PID-F tuning, enabling effective parameter adjustment under nonlinear and time-varying engine dynamics. A modified objective function was formulated to simultaneously penalize overshoot and cumulative tracking error, ensuring a rapid transient response with minimal steady-state deviation. Through extensive MATLAB/Simulink simulations, the FLA-optimized PID-F controller demonstrated superior dynamic performance compared to benchmark algorithms such as the SCHO, WOA, CS, and the Simulink PID tuner. The FLA-based design achieved zero overshoot, the fastest rise and settling times, and minimal steady-state error, while maintaining robustness under noise and disturbance conditions. The findings were supported by non-parametric statistical tests (Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test) and error-integral indices (IAE, ISE, ITAE, and ITSE), which consistently confirmed the algorithm’s superiority in convergence stability, precision, and consistency. Moreover, the disturbance rejection and reference tracking analyses validated the controller’s adaptability to variable operating conditions, further emphasizing its robustness and reliability.

Beyond its simulation success, the proposed approach has strong practical relevance to automotive control systems. The PID-F architecture ensures full compatibility with existing electronic control units (ECUs), allowing seamless implementation without hardware modifications. Its inherent noise attenuation capability contributes to smoother torque generation and improved fuel efficiency—key factors in reducing emissions and extending engine life. Due to its algorithmic simplicity and model-independent tuning mechanism, the developed framework can also be extended to other powertrain systems, including hybrid and electric vehicles, for tasks such as motor-speed control, regenerative braking, and energy-management optimization.

For future studies, several promising directions are identified. First, hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) implementation and real-time validation will be pursued to assess the controller’s feasibility under realistic operating conditions. Next, broader experimental evaluations involving varying load disturbances, ambient temperatures, and fuel characteristics will be conducted to confirm robustness and stability. The integration of adaptive or self-learning mechanisms within the FLA may further enhance responsiveness to rapidly changing engine dynamics, ensuring consistently low overshoot and fast recovery. Additionally, the extension of this framework to advanced engine models such as variable valve timing or turbocharged systems, as well as the inclusion of disturbance observers and data-driven compensation strategies, could significantly improve accuracy and resilience. In addition, future studies may also examine the robustness of the proposed controller under broader and more realistic operating conditions, including variations in ambient temperature, fuel quality, and long-term component aging. Such analyses will provide deeper insight into the controller’s long-term stability and adaptability for real automotive environments.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \({S}^{i}\) :

-

Position vector of the i-th solution (candidate)

- \({S}_{new}^{i}\) :

-

Updated position of the i-th solution after movement or flooding

- \({S}_{best}\) :

-

Current best (minimum-cost) solution in the population

- \({S}^{j}\) :

-

Randomly selected solution distinct from ( Si )

- \(rand\) :

-

Uniform random number in the range [0, 1]

- \(randn\) :

-

Normally distributed random variable (mean = 0, variance = 1) introducing stochasticity

- \(S_{\max } ,S_{\min }\) :

-

Upper and lower bounds of the search space

- \({P}_{k}\) :

-

Water depletion coefficient controlling disturbance intensity

- \({P}_{flood}\) :

-

Flood probability derived from cost-function values

- \(Iter\) :

-

Current iteration number

- \({Iter}_{max}\) :

-

Maximum number of iterations allowed

- \(\text{f}\left({S}^{i}\right)\) :

-

Cost-function value of the i-th solution

- \(f_{\min } ,f_{max}\),:

-

Best and worst cost-function values in the population

- \({\dot{m}}_{\text{air}}\) :

-

Air mass flow rate through the throttle (kg/s)

- \({A}_{\text{th}}\) :

-

Effective throttle area (function of throttle angle, m2)

- \({p}_{a}\), \({T}_{a}\) :

-

Ambient pressure (Pa) and temperature (K)

- \(R\) :

-

Specific gas constant for air (J/kg·K)

- \({P}_{m}\), \({T}_{m}\) :

-

Intake manifold pressure (Pa) and temperature (K)

- \({V}_{m}\) :

-

Manifold volume (m3)

- \({\dot{m}}_{\text{intake}}\) :

-

Air mass flow rate entering the cylinders (kg/s)

- \({\dot{m}}_{\text{mix}}\) :

-

Air–fuel mixture mass flow rate (kg/s)

- \({\eta }_{v}\) :

-

Volumetric efficiency (dimensionless)

- \({V}_{d}\) :

-

Engine displacement volume (m3)

- \({\omega }_{\text{eng}}\) :

-

Engine angular speed (rad/s)

- \(\Phi\) :

-

Equivalence ratio (actual-to-stoichiometric fuel–air ratio)

- \((F/A{)}_{s}\) :

-

Stoichiometric fuel–air ratio (dimensionless)

- \(SA\) :

-

Spark advance angle (°)

- \({T}_{\text{engine}}\) :

-

Generated engine torque (N·m)

- \({T}_{\text{load}}\) :

-

Load torque (N·m)

- \(J\) :

-

Engine moment of inertia (kg·m2)

References

Papagiannakis, R., Rakopoulos, D. & Rakopoulos, C. Theoretical study of the effects of spark timing on the performance and emissions of a Light-Duty spark ignited engine running under either gasoline or ethanol or butanol fuel operating modes. Energies (Basel). 10, 1198. https://doi.org/10.3390/en10081198 (2017).

Sameeth Raj, R., Lesslins Raja Deva Doss, S., Surendar, N. & Gowthaman, S. Effect of Pre-Heated air on spark ignition engine fuelled with Petrol-Ethanol blends. Int. J. Recent. Technol. Eng. 8, 174–177. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijrte.D1038.1284S219 (2019).

Yildiz, Y., Annaswamy, A. M., Yanakiev, D. & Kolmanovsky, I. Spark-Ignition-Engine idle speed control: an adaptive control approach. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 19, 990–1002. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCST.2010.2078818 (2011).

Eker, E., Kayri, M., Ekinci, S. & Izci, D. A new fusion of ASO with SA algorithm and its applications to MLP training and DC motor speed control. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 46, 3889–3911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-020-05228-5 (2021).

Manikandan, G. et al. Genetic Algorithm Based Robust H ∞ Loop Shaping Control of SI Engines. In: 2021 International Conference on Emerging Smart Computing and Informatics (ESCI). 639–642 https://doi.org/10.1109/ESCI50559.2021.9396841 (IEEE, 2021).

Kang, M. & Shen, T. Experimental comparisons between LQR and MPC for spark-ignition engine control problem. In: 2017 36th Chinese Control Conference (CCC). 2651–2656 https://doi.org/10.23919/ChiCC.2017.8027763 (IEEE, 2017).

Pamminger, M., Hall, C. M. & Wallner, T. Model predictive combustion control of a gasoline compression ignition engine. Control Eng. Pract. 119, 104977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conengprac.2021.104977 (2022).

Amini, M. R., Shahbakhti, M. & Pan, S. Adaptive Discrete Second-Order Sliding Mode Control With Application to Nonlinear Automotive Systems. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4040208 (2018).

Kanungo, A., Mittal, M. & Dewan, L. Comparison of Haar and Daubechies wavelet based denoising for speed control of DC motor. In: 2020 First IEEE International Conference on Measurement. Instrumentation, Control and Automation (ICMICA). 1–4 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMICA48462.2020.9242877 (IEEE, 2020).

Kanungo, A., Mittal, M. & Dewan, L. Wavelet based PID controller using GA optimization and scheduling for feedback systems. J. Interdisciplinary Math. 23, 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720502.2020.1721708 (2020).

Kanungo, A., Kumar, P., Gupta, V., Salim, N. K. & Saxena A design an optimized fuzzy adaptive proportional-integral-derivative controller for anti-lock braking systems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 133, 108556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108556 (2024).

Kanungo, A., Choubey, C., Gupta, V., Kumar, P. & Kumar, N. Design of an intelligent wavelet-based fuzzy adaptive PID control for brushless motor. Multimed Tools Appl. 82, 33203–33223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-14872-6 (2023).

Izci, D., Ekinci, S., Zeynelgil, H. L. & Hedley, J. Fractional order PID design based on novel improved slime mould algorithm. Electr. Power Compon. Syst. 49, 901–918. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325008.2022.2049650 (2021).

Abualigah, L., Izci, D., Ekinci, S., Zitar, R. A. & Controller Optimizing Aircraft Pitch Control Systems: A Novel Approach Integrating Artificial Rabbits Optimizer with PID-F Int. J. Rob. Control Syst. 4 354–364. https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v4i1.1347. (2024).

Kanungo, A., Mittal, M. & Dewan, L. Critical analysis of optimization techniques for a MRPID thermal system controller. IETE J. Res. 69, 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/03772063.2020.1808092 (2023).

Kanungo, A., Mittal, M., Dewan, L., Mittal, V. & Gupta, V. Speed control of DC motor with MRPID controller in the presence of noise. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 124, 893–907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-021-09388-x (2022).

Ebrahimi, B. et al. A parameter-varying filtered PID strategy for air–fuel ratio control of spark ignition engines. Control Eng. Pract. 20, 805–815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conengprac.2012.04.001 (2012).

Chamsai, T., Jirawattana, P. & Radpukdee, T. Robust adaptive PID controller for a class of uncertain nonlinear systems: an application for speed tracking control of an SI engine. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/510738 (2015).

Ziegler, J. G. & Nichols, N. B. Optimum settings for automatic controllers. J. Fluids Eng. 64, 759–765. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4019264 (1942).

Cohen, G. H. & Coon, G. A. Theoretical consideration of retarded control. J. Fluids Eng. 75, 827–834. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4015451 (1953).

Rivera, D. E., Morari, M. & Skogestad, S. Internal model control: PID controller design. Industrial Eng. Chem. Process. Des. Dev. 25, 252–265. https://doi.org/10.1021/i200032a041 (1986).

Silva, N., Bispo, H., Brito, R. & Manzi, J. Robust stability analysis inspired by classical statistical principles. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 92, 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjce.21825 (2014).

Chang, W. D., Hwang, R. C. & Hsieh, J. G. A self-tuning PID control for a class of nonlinear systems based on the Lyapunov approach. J. Process. Control. 12, 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-1524(01)00041-5 (2002).

Weeks, R. W. & Moskwa, J. J. Automotive Engine Modeling for Real-Time Control Using MATLAB/SIMULINK. In: SAE Technical Papers. 295–309 https://doi.org/10.4271/950417 (SAE International, 1995).

Ekinci, S. & Izci, D. Whale optimization algorithm based controller design for air-fuel ratio system. In Handbook of Whale Optimization Algorithm (ed. Mirjalili, S.) 411–421 (Elsevier, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-32-395365-8.00035-X.

Mosaad, A. M., Attia, M. A. & Abdelaziz, A. Y. Whale optimization algorithm to tune PID and PIDA controllers on AVR system. Ain Shams Eng. J. 10, 755–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2019.07.004 (2019).

Mirjalili, S. & Lewis, A. The Whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 95, 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.008 (2016).

Gandomi, A. H., Yang, X. S. & Alavi, A. H. Cuckoo search algorithm: A metaheuristic approach to solve structural optimization problems. Eng. Comput. 29, 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00366-011-0241-y (2013).

Bai, J. et al. A Sinh Cosh optimizer. Knowl. Based Syst. 282, 111081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2023.111081 (2023).

Zhao, W. et al. Electric eel foraging optimization: A new bio-inspired optimizer for engineering applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 238, 122200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122200 (2024).

Hou, Y., Gao, H., Wang, Z. & Du, C. Improved grey Wolf optimization algorithm and application. Sensors 22, 3810. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22103810 (2022).

Asghari, K., Masdari, M., Gharehchopogh, F. S. & Saneifard, R. A chaotic and hybrid Gray wolf-whale algorithm for solving continuous optimization problems. Progress Artif. Intell. 10, 349–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13748-021-00244-4 (2021).

Ghasemi, M. et al. Flood algorithm (FLA): an efficient inspired meta-heuristic for engineering optimization. J. Supercomput. 80, 22913–23017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-024-06291-7 (2024).

Li, Y., Ang, K. H. & Kiam Heong, G. C. Y. PID control system analysis and design. IEEE Control Syst. 26, 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCS.2006.1580152 (2006).

Izci, D., Ekinci, S., Eker, E. & Demirören, A. Multi-strategy modified INFO algorithm: performance analysis and application to functional electrical stimulation system. J. Comput. Sci. 64, 101836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocs.2022.101836 (2022).

Moskwa, J. J. & Hedrick, J. K. Automotive Engine Modeling for Real Time Control Application., in: Proceedings of the American Control Conference. 341–346 https://doi.org/10.23919/ACC.1987.4789343 (1987).

MathWorks & Inc PID Controller Tuning in Simulink, Mathworks - Documentation 1–6. (2016) http://www.mathworks.com/help/slcontrol/gs/automated-tuning-of-simulink-pid-controller-block.html (2024).

Setiadi, H. et al. Design of spark ignition engine speed control using Bat algorithm. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. (IJECE). 11, 794. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijece.v11i1.pp794-801 (2021).

Woolson, R. F. Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Wiley Encyclopedia Clin. Trials https://doi.org/10.1002/9780471462422.eoct979 (2008).

Duarte-Forero, J., Obregón-Quiñones, L. & Valencia-Ochoa, G. Comparative Analysis of Intelligence Optimization Algorithms in the Thermo-Economic Performance of an Energy Recovery System Based on Organic Rankine Cycle. J. Energy Resour. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4049599 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Serdar Ekinci, Davut Izci: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Investigation, Writing—Original draft preparation. Cebrail Turkeri: Data curation, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing. Mohit Bajaj, Olena Rubanenko: Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ekinci, S., Izci, D., Turkeri, C. et al. Flood Algorithm-Tuned PID-F Controller with a Modified Objective Function for Robust and Noise-resilient Speed Control of Nonlinear SparkIgnition Engines. Sci Rep 15, 45481 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29231-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29231-8