Abstract

To address the invert heave issue in large-span tunnels traversing fully weathered, water-rich cretaceous mudstone in western China’s complex geological zones, the asymmetric invert heave mechanism was investigated and corresponding treatment measures were proposed using the reservoir-underpass section of the Shaofang Yakou Tunnel as a case study. A combined approach of field monitoring, geological investigation, and finite element numerical simulation was employed. The results indicate that the tunnel’s flat structural geometry induces stress concentration at the arch foot. The bearing capacity of the fully weathered mudstone at the tunnel base decreases to 50 kPa upon water-induced softening, compounded by a hydraulic head pressure of 84 m, leading to a maximum left invert heave of 174 mm. An integrated treatment strategy of “drainage holes for pressure relief + grouted steel pipe reinforcement + reinforced concrete connecting beams” was developed to mitigate this. Post-implementation monitoring confirmed stabilized tunnel deformation, with residual heave reduced to less than 3 mm. The proposed technology effectively suppresses floor heave progression and offers a reference for analogous water-rich soft rock tunnel projects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As critical infrastructure for mountain crossings, tunnels account for a growing proportion of transportation networks1,2,3. When constructed in geologically complex formations with poor-quality surrounding rock, groundwater accumulation at the tunnel invert induces the softening of underlying strata4,5,6. This process consequently induces structural defects, including invert heave and cracking7, which are particularly prevalent in large-span tunnels traversing fully weathered, water-rich mudstone-shale interbeds. Certain invert heave phenomena exhibit time-dependent creep behavior, in which post-construction heave deformation progressively exceeds the ultimate bearing capacity of the invert structure2,8,9. This mechanical deterioration ultimately leads to differential displacement and poses severe operational safety risks10,11.

Based on this research foundation, scholars have conducted extensive investigations into tunnel invert heave issues. Zhong et al.12 investigated the Taoshuya Tunnel through field surveys and geological investigations, identifying the principal mechanisms of floor heave and deriving continuum-mechanics-based formulations for heave induced by rock stratum buckling, swelling, and rheological deformation. Butscher13 investigated the swelling behavior of clay–sulfate rocks by linking micro-scale molecular processes with macro-scale deformation, showing that excavation-induced groundwater flow alterations accelerate the anhydrite–gypsum transformation and induce tunnel invert heave. Shi et al.14 conducted long-term monitoring of deformation patterns and internal forces in tunnel inverts, systematically analyzing the underlying deformation mechanisms. Fan et al.15 investigated hydraulic pressure characteristics and mechanical responses in lining structures of water-rich karst tunnels. Zhao et al.16 proposed three optimized waterproofing and drainage solutions for invert heave and related defects in karst tunnels within water-rich regions. Feng et al.17 employed comprehensive methodologies, including field investigations, numerical simulations, and in-situ monitoring to study failure mechanisms and remediation measures for floor heave in high-speed railway tunnels through interbedded rock formations under high geostress conditions. Li et al.18 conducted biaxial-graded loading tests on stratified rock specimens to investigate deformation mechanisms and failure progression in tunnel floor heave within layered rock masses. Wang et al.19 utilized combined scale model experiments and numerical simulations to examine stress redistribution in surrounding rocks and supporting structures during moisture-induced swelling of mudstone in loess-mudstone tunnels under cold region conditions. Zhou et al.20 developed a moisture-enhanced loess tunnel model to investigate the evolutionary mechanisms of inverted heave development. Chen et al.9 investigated asymmetric water infiltration-induced invert failures in loess highway tunnels, proposing an integrated remediation strategy combining “steel pipe pile reinforcement at arch footings” with an “optimized tunnel drainage system”. Feng et al.21 employed field testing and numerical modeling to characterize water pressure distribution and lining deformation patterns in water-rich tunnels traversing fault zones. Luo et al.22 established the evolutionary mechanism of intense rainfall-induced invert failures through field investigations and physical modeling, subsequently recommending corresponding mitigation measures. Although considerable progress has been made in understanding tunnel floor heave, most existing studies have primarily focused on symmetric uplift or general soft-rock swelling phenomena. In contrast, the specific problem of asymmetric invert uplift in large-span tunnels beneath reservoir sections has not been systematically investigated. This knowledge gap is particularly critical for tunnels constructed in fully weathered, water-rich Cretaceous mudstone, where reservoir-induced seepage significantly exacerbates the softening and swelling of the surrounding rock.

Hence, taking the case of large-scale asymmetric uplift occurring in the inverted arch of a large-span tunnel beneath a reservoir section as the engineering context, this study systematically analyzes the genesis mechanisms of the uplift phenomenon. A finite element numerical model is subsequently established to simulate the tunnel construction process using the finite element method. Through numerical analysis, the characteristics of asymmetric inverted arch uplift are elucidated, based on which targeted rehabilitation measures are proposed. The effectiveness of these measures is validated through field monitoring data, ultimately serving as a reference for the design and construction of large-span tunnel projects in analogous geological conditions.

General overview

Project overview

The Shaofangyangkou Tunnel, part of the Chuxiong-Dali Expressway (reconstruction and expansion project), is a bidirectional six-lane separated tunnel with a design speed of 100 km/h. The right tunnel span is from K121 + 372 to K123 + 970 (total length 2,598 m), while the left tunnel spans from ZK121 + 415 to ZK124 + 050 (total length 2,635 m). The lateral distance between the two tunnels ranges from 23 to 28 m. The tunnel is located in Shidong Village, Jiangpo Town, Muding County, with a straight plan alignment throughout. The left tunnel is situated on a composite slope of 1.1% (2,528 m) and −2.2% (70 m), while the right tunnel follows a gradient of 1.09% (2,485 m) and −2.2% (150 m). Notably, the tunnel features a maximum excavation span of 17.15 m and a maximum excavation height of 11.68 m, classified as a flat-topped tunnel profile. The maximum burial depth is 165 m, and the tunnel incorporates two vehicular cross-passages and five pedestrian cross-passages. The support lining system employs a reinforced structure, primarily utilizing SF5a and SF5c linings. Key project parameters, including the geological longitudinal section, lining design details, and main support specifications, are illustrated in Figs. 1, 2, and Table 1, respectively.

Tunnel distress conditions

The tunnel was completed in May 2019. By mid-February 2020, longitudinal cracks were observed in the concrete pavement and cable trench near K122 + 700 of the right tunnel. Significant asymmetric invert uplift occurred along the left side of the right tunnel section K122 + 520–K122 + 900, with moderate deformation in the central area and minimal change on the right side. The maximum uplift displacement of 174 mm (above design elevation) was recorded at K122 + 700. Nine convergence measurements revealed that the secondary lining at K122 + 700 exhibited the largest horizontal convergence, accumulating to 5.92 mm. The deformation primarily manifested as asymmetric invert uplift, as illustrated in Figs. 3, 4 deformation observation data shows that the inverted arch uplift has not converged.

During the excavation, the surrounding rock of this section of the tunnel was extremely poor, which is completely weathered mudstone with sandstone. The advanced prediction shows that all of them are V2-graded surrounding rock. Because the tunnel is located directly below the Shaofangba Reservoir, the water level elevation is 1898 m, the tunnel elevation is 1814 m, and the vertical height difference is 84 m. There is a risk of water penetration during tunnel excavation. Measures such as strengthening advanced support, strengthening initial support and secondary lining have been taken on site. When the tunnel is excavated, a three-dimensional free surface is formed, and groundwater seeps into the tunnel face through joint fissures and accumulates at the inverted arch. At the same time, since this section is a reverse slope construction, the surrounding rock of the inverted arch is soaked for a long time after the groundwater is accumulated, resulting in a rapid decrease in the bearing capacity of the surrounding rock of the inverted arch. The plane position relationship between the reservoir and the tunnel is shown in Fig. 5.

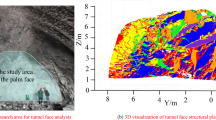

According to the geological sketch and advanced geological prediction of the tunnel face (see Fig. 6).

The left side of the tunnel face is completely weathered mudstone, and the right side is completely to moderately weathered sandstone. After soaking, the bearing capacity of the left inverted arch foundation is only about 50 kPa, which is muddy and semi-flowing. The water content is 90%, and the bearing capacity of the foundation is very low. The bearing capacity of the fully weathered sandstone section of the right inverted arch foundation of the tunnel is about 150 kPa after water immersion, and the bearing capacity is about three times that of the left inverted arch foundation. Following the completion of the tunnel’s secondary lining construction, progressive invert uplift was observed, with the maximum displacement reaching 17.4 cm at the left invert of the right tunnel section K122 + 700. This deformation caused structural failure in the reinforced sidewalls of the cable trench and exhibited no signs of stabilization, posing imminent operational safety risks that necessitated immediate remediation measures.

Analysis of tunnel distress causes

Mechanism of invert uplift

The primary factors influencing tunnel invert uplift include:

-

1)

Structural Configuration: Non-circular, large-span flat profiles induce stress redistribution during excavation, subjecting the lining to compressive forces from the surrounding rock. Exceeding structural bearing capacity triggers distress, particularly at the arch foot’s small-radius curvature—a critical zone combining high bending moments, axial forces, and construction joints between the secondary lining and invert.

-

2)

Hydrogeological Effects: Prolonged water saturation from reservoir-seepage fractures degrades the physical–mechanical properties (cohesion, internal friction angle) of the foundation rock, reducing bearing capacity and confinement while increasing structural loading.

-

3)

Expansive Clay Mineralogy: Water-sensitive expansive minerals in foundation strata induce volumetric swelling, generating sustained post-lining deformation and extrusion pressures.

-

4)

Hydrostatic Pressure: Continuous groundwater accumulation beneath the invert imposes persistent hydraulic loading.

-

5)

Geostress Conditions: High in-situ stress-to-rock strength ratios exacerbate structural demands.

-

6)

Dynamic Loads: Operational vibrations (seismic/vehicular) accelerate fatigue degradation.

-

7)

Post-excavation, the transition from triaxial to biaxial stress states creates a weakened damage zone through stress redistribution and concentration. Within this zone, shear stress at any material plane reaches critical failure thresholds when equaling residual shear strength.

Numerical simulation

Large-scale finite element software is used. As shown in Fig. 7, the model is 160 m wide and 269 m high, with horizontal constraints on both sides and vertical and horizontal constraints at the bottom.

The formation is simulated by the Mohr–Coulomb constitutive model, and the specific parameters are shown in Table 2.

Calculation parameters of numerical analysis. The simulation steps are carried out according to the actual project, using the three-step reserved core soil excavation method. Firstly, the upper step is excavated circumferentially, and the initial support is applied. The upper step is excavated in the middle step, the middle step is initially supported, the core soil is excavated, the lower step is excavated, the lower step is initially supported, the inverted arch is excavated, the inverted arch is initially supported, and the secondary lining is applied. Through comprehensive analysis, the main reasons for the asymmetric uplift disease of the tunnel invert arch in this project are as follows:

-

1)

The tunnel is a flat structure. The tunnel span is large, with a maximum span is 17.14 m, and a maximum height is 11.68 m. The force of the inverted arch foot is unfavorable, but for the general geological conditions, there is generally no disease. When encountering extremely soft rock, due to the small arc radius of the arch foot, the bending moment axial force here is large, and the inverted arch uplift and other diseases are prone to occur.

-

2)

In this tunnel, the surrounding rock of the left inverted arch basement of the tunnel is completely weathered mudstone. After soaking in water, the surrounding rock decreases rapidly, resulting in a significant reduction in the residual shear strength of the surrounding rock, a decrease in the anti-uplift capacity of the surrounding rock, and a decrease in the surrounding constraint capacity. The right inverted arch basement of the tunnel is mostly sandstone. After soaking in water, the reduction is small, and the shear strength of the surrounding rock decreases little.

-

3)

Groundwater is enriched under the inverted arch, and there is head pressure. Groundwater exerts pressure on the inverted arch structure, increasing the load.

-

4)

Through the analysis of the composition of the surrounding rock of the tunnel basement, the bearing capacity of the foundation is very low, while the bearing capacity of the right foundation is slightly higher, so the disease mainly occurs on the left side of the tunnel. Because of this situation, the large finite element software is used for numerical analysis to simulate the actual terrain formation, and analyze the plastic zone and stress situation, and the tunnel invert arch uplift deformation distribution map and plastic zone distribution map are shown in Figs. 8 and 9.

Tunnel disease treatment measures

Treatment measures

Based on the analysis of the causes of the inverted arch uplift, as shown in Fig. 10, the corresponding treatment measures are as follows:

-

1)

The left foundation is reinforced by a micro steel flower tube, and the bearing capacity of the base rock mass is improved by combining the small pipe to consolidate the base rock mass. The reinforcement depth of the steel pipe pile needs to cross the plastic zone and anchor in the deep stable rock mass to form the vertical pull-out force and resist the vertical uplift deformation, consolidating the rock mass, enhancing the base constraint, and resisting the uplift.

-

2)

Drainage holes are installed. Due to the seepage of the reservoir water flow, after the secondary lining is completed, there is still water under the inverted arch, and there is local water pressure squeezing the inverted arch, which increases the uplift disease of the inverted arch. Therefore, a dredging hole is set every 5 m. The flow from the drainage holes into the tunnel ditch through the blind ditch so that the waterway is unobstructed and the lining structure is prevented from squeezing.

-

3)

The reinforced concrete coupling beam is installed in the inverted arch layer and is anchored with the secondary lining to form a statically determinate structure, which forms a whole with the micro steel flower tube and works together.

-

4)

The position of the ditch and cable trench at the small arc of the left arch foot of the tunnel is filled with reinforced concrete to increase the stiffness and resistance capacity at the small arc of the left arch foot.

Remediation effectiveness analysis

The field monitoring data (Fig. 11) shows that, after the implementation of the treatment project (Fig. 12), the tunnel invert exhibited an initial uplift deformation of 1.3 – 3.0 mm. Furthermore, cumulative deformation measurements at multiple sections (Table 3) confirm that the uplift value remained within a small range.

The observation data show that the deformation shows typical convergence characteristics within an aging period of about 30 days, and the final deformation tends to be stable. The overall stability of the tunnel lining structure indicates that the treatment measures are effective. For the large-span flat tunnel structure with weak surrounding rock, measures such as strengthening support, strengthening arch foot stiffness, and early base consolidation can be taken during excavation. If the geological conditions are worse than those of the V2-grade surrounding rock, the tunnel’s inner contour can be optimized to deepen the inverted arch, and the thickness and reinforcement of the secondary lining can be strengthened to enhance the overall bending resistance of the tunnel structure. However, if all optimization measures focus on the inner contour and deepen the inverted arch, the cost will be greatly increased. Therefore, according to the conditions of this stratum, this treatment scheme is the most economical way, that is, to find the problem and then deal with it, solving the problems of poor bearing capacity of the foundation and weak bending resistance of the arch foot, and to carry out targeted reinforcement. After half a year of operation, it was found that the inverted arch disease no longer developed, indicating the effectiveness of the treatment.

Conclusions

The pathogenesis of inverted arch uplift in large-span tunnels constructed within fully-weathered, water-saturated Cretaceous mudstone formations was investigated. Through integrated field monitoring, laboratory testing, and numerical simulation, targeted remediation strategies were formulated. The main conclusions are as follows.

-

1)

In the construction of large-span tunnels in fully weathered water-rich Cretaceous mudstone, especially in the construction of the reservoir section, groundwater enrichment under the inverted arch, and there is water head pressure. At the same time, the surrounding rock is softened. The groundwater squeezes the inverted arch structure of the tunnel and increases the inverted arch load. The softening of the surrounding rock leads to the weakening of the surrounding constraints of the tunnel, which is not conducive to the stress of the tunnel structure, resulting in the tunnel being prone to floor heave deformation.

-

2)

The tunnel’s basement strata contain many expansive hydrophilic clay minerals. After soaking in water, the volume expands, resulting in expansion deformation and expansion extrusion. As a result, the pressure increases after the second lining is poured, squeezing the tunnel lining structure and endangering the tunnel’s long-term operational safety.

-

3)

The numerical simulation shows that under the composite stratum of fully weathered mudstone and sandstone, the floor heave deformation of the large-span flat-arched tunnel was characterized by a distinct asymmetric uplift pattern, with a maximum displacement of approximately 9.0 mm. Furthermore, the distribution of the plastic zone was most concentrated and severe at the left arch foot of the tunnel invert.

-

4)

The φ108 steel flower tube (9 m) is used to grout and reinforce the left foundation, and the base rock mass is consolidated by small pipe technology to enhance its integrity and stability. Secondly, the reinforced concrete coupling beam is installed in the inverted arch layer and anchored to the secondary lining structure to form a statically determinate structure and to improve the bearing capacity of the base rock mass. In addition, drainage holes are installed to discharge water and reduce pressure. This measure can significantly control the occurrence of invert heave and ensure the long-term stability and safety of the tunnel.

This study contributes to understanding invert arch uplift in large-span tunnels within fully weathered, water-rich Cretaceous mudstone formations, providing a valuable remediation strategy for similar projects. However, the proposed treatments are limited to specific geological conditions, particularly those under reservoir sections, and their applicability to other tunnel types remains uncertain. The long-term effectiveness of the treatment also requires further validation. Future research should focus on long-term monitoring and advanced modeling techniques to better predict tunnel behavior in varied conditions. Additionally, the development of automated monitoring and adaptive treatment strategies could enhance maintenance efficiency.

Data availability

Data will be made available at the request of the corresponding author.

References

Wang, Z. et al. Experimental study on mechanical behavior and countermeasures of mountain tunnels under strike-slip fault movement. Underground Space 21, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.undsp.2024.07.006 (2025).

Kong, C. et al. Analysis of mechanical properties and joint selection for secondary linings in drill and blast tunnels with prefabricated invert arch: Case study of a single-line railway tunnel. Tunnel. Underground Space Technol. 144, 105560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2023.105560 (2024).

Deng, Z. et al. Study on the field monitoring, assessment and influence factors of pipe friction resistance in rock. Tunnel. Underground Space Technol. 154, 106053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2024.106053 (2024).

Zhu, X., Zhang, Z., Feng, Y. & Yu, H. Damage mechanism of tunnel base heave under interlayer weakening effect in nearly horizontal layered rock. Tunnel. Underground Space Technol. 159, 106439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2025.106439 (2025).

Yue, J., Liang, Q., Zhang, T. & Fan, C. Research on mechanical response and time-space distribution of supporting structure of deep-buried tunnel in naturally water-rich loess. Tunnel. Underground Space Technol. 147, 105688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2024.105688 (2024).

Fang, X., Yang, J., Xiang, M., Zhang, X. & Li, L. Model test and numerical simulation on the invert heave behaviour of high-speed railway tunnels with rainstorm. Trans. Geotechn. 37, 100891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2022.100891 (2022).

Deng, Z. et al. Main engineering problems and countermeasures in ultra-long-distance rock pipe jacking project: Water pipeline case study in Chongqing. Tunnel. Underground Space Technol. 123, 104420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2022.104420 (2022).

Zhu, Y., Yang, H., Huang, M. & Wang, L. External hydraulic pressure and invert uplift study in a non-circular shallow tunnel. Tunnel. Underground Space Technol. 122, 104345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.104345 (2022).

Chen, C., Lai, H. & Liu, Y. Study on failure mechanism and treatment measures of inverted arch under asymmetric immersion of loess tunnel basement. Eng. Fail. Anal. 163, 108494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108494 (2024).

Zhao, H. & Liu, L. Mechanical behavior and mitigation strategies of rectangular subway tunnels in soil under multiple normal fault dislocations. Tunnel. Underground Space Technol. 158, 106431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2025.106431 (2025).

Liu, Y., Liao, S., Yang, Y. & Zhang, B. Data-driven and physics-informed neural network for predicting tunnelling-induced ground deformation with sparse data of field measurement. Tunnel. Underground Space Technol. 152, 105951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2024.105951 (2024).

Zhong, Z., Liu, X., Wang, D., Zheng, C. & Huang, M. Mechanism analysis of floor heave in Taoshuya tunnel and its prevention techniques. Chinese J. Geotechn. Eng. 34, 471–489 (2012).

Butscher, C., Huggenberger, P. & Zechner, E. Impact of tunneling on regional groundwater flow and implications for swelling of clay–sulfate rocks. Eng. Geol. 117, 198–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2010.10.018 (2011).

Shi, C., Lei, M., Peng, L., Yang, W. & Ding, Z.. In-situ monitoring and analysis of mechanical characteristics and deformation of bottom structure of tunnels. Chinese J. Geotechn. Eng. 34, 879–884 (2012).

Fan, H., Zhao, D., Lai, J. & Xie, Y. Water pressure and stress characteristics of lining structure in water rich karst tunnel. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 218, 012122 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/218/1/012122.

Zhao, D., Fan, H., Jia, L. & Song, Y. Research on waterproofing and drainage optimization scheme for karst tunnel lining in water-rich areas. Environ. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-021-09466-0 (2021).

Feng, J. et al. Study on failure mechanism and treatment measures of floor heave of high-speed railway tunnel in the interbedded surrounding rock with high geostress. Eng. Fail. Anal. 150, 107365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2023.107365 (2023).

Li, D., Peng, Z., Zhu, Q., Ma, J. & Gong, H. Experimental study on the floor heave and failure process of rock samples under biaxial step loading. Appl. Sci. 13, 12757. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132312757 (2023).

Wang, D. et al. Experimental and numerical investigation on the damage mechanism of a loess-mudstone tunnel in cold regions. Atmosphere 14, 1391. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos14091391 (2023).

Chang, Z. et al. Large-scale field tunnel model experience and time-dependent floor heave induced by humidification. Tunnel. Underground Space Technol. 145, 105615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2024.105615 (2024).

Feng, Z., Li, D., Wang, F., Zhang, L. & Wang, S. Field test and numerical simulation study on water pressure distribution and lining deformation law in water-rich tunnel crossing fault zones. Appl. Sci. 14, 7110. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14167110 (2024).

Luo, Y., Yang, J., Xie, Y., Fu, J. & Zhang, C. Investigation on evolution mechanism and treatment of invert damage in operating railway tunnels under heavy rainfall. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-024-03655-4 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the Talent Fund of Beijing Jiaotong University (Grant No. 2024XKRC035), National Natural Science Fund of China (Grant No. 52578458), Yunnan Communications Investment & Construction Group Technological Innovation Project of China (Grants Nos. YCIC-YF-2022-08, YCIC-YF-2022-14), Key Science and Technology Program of Yunnan Province (Grant No. 202402AC080003), Science and Technology Innovation Project of Yunnan Jiaotou Group Yunling Construction Co., Ltd. (Grant No. YLJS-KF-2024-06), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42307246) and the National Key R&D Program Funding of China (Grant No. 2023YFB2603902).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Junwu Chen: Conceptualization, Investigation and Writing—Original Draft. Zuowei Hao Methodology, Writing—Original Draft. Zhiyun Deng: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Review & Editing. Baoguo Liu: Conceptualization, Supervision, Visualization. Xiaomeng Shi: Visualization, Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Hao, Z., Deng, Z. et al. Analysis and treatment of invert uplift in a long span tunnel in weak mudstone. Sci Rep 16, 83 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29232-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29232-7