Abstract

Efficient task scheduling in cloud computing is crucial for managing dynamic workloads while balancing performance, energy efficiency, and operational costs. This paper introduces a novel Reinforcement Learning-Driven Multi-Objective Task Scheduling (RL-MOTS) framework that leverages a Deep Q-Network (DQN) to dynamically allocate tasks across virtual machines. By integrating multi-objective optimization, RL-MOTS simultaneously minimizes energy consumption, reduces costs, and ensures Quality of Service (QoS) under varying workload conditions. The framework employs a reward function that adapts to real-time resource utilization, task deadlines, and energy metrics, enabling robust performance in heterogeneous cloud environments. Evaluations conducted using a simulated cloud platform demonstrate that RL-MOTS achieves up to 27% reduction in energy consumption and 18% improvement in cost efficiency compared to state-of-the-art heuristic and metaheuristic methods, while meeting stringent deadline constraints. Its adaptability to hybrid cloud-edge architectures makes RL-MOTS a forward-looking solution for next-generation distributed computing systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cloud computing has become a key part of modern computer infrastructure. It lets a wide range of applications access computational resources on demand and in a scalable way1. Cloud service providers (CSPs) use virtualized environments to offer a variety of services, including Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS), and Software as a Service (SaaS), to fulfill the needs of different users2. But the fact that workloads in the cloud are getting more complicated and changing all the time makes it very hard to manage resources, especially when it comes to scheduling tasks3. Efficient task scheduling is very important for making the best use of resources, keeping prices low, and making sure that the QoS is high. It also helps with the growing problem of data center energy use4. As cloud computing evolves with the addition of edge computing and hybrid architectures, the necessity for smart and flexible scheduling solutions becomes even more clear4.

Task scheduling optimizes performance and efficiency in cloud computing by distributing computational activities to physical server-based virtual machines (VMs). Several studies have used adaptive scheduling to improve energy efficiency and cost. Live migration strategies improve energy efficiency and resource balance in virtualized data centers5, while improved particle swarm optimization speeds convergence and allocation efficiency in complex scheduling scenarios6. Cloud–edge energy usage and latency can be balanced using joint communication and job offloading7. Recent reinforcement learning approaches based on deep Q-networks have shown significant adaptation for dynamic and uncertain scheduling situations8. For sustainable system management under dynamic workloads, multi-objective coordination models including energy and cost optimization have worked9.

The use of machine learning, especially Reinforcement Learning (RL), in task scheduling has shown promise in overcoming these problems10. RL methods like Q-learning and DQNs let systems learn the best scheduling policies by interacting with their surroundings and adjusting to changes in workload and resource availability11.

The importance of efficient task scheduling in cloud computing cannot be overstated, as it directly impacts the performance, cost, and sustainability of cloud services12. With the global cloud computing market projected to grow significantly, driven by increasing demand for data-intensive applications such as artificial intelligence (AI), big data analytics, and Internet of Things (\(IoT\)) services, optimizing resource allocation is critical for CSPs to remain competitive13,14. Moreover, the energy consumption of data centers, which accounts for a substantial portion of global electricity usage, underscores the need for energy-efficient scheduling strategies to reduce environmental impact and operational costs15. The proposed RL-MOTS framework addresses these imperatives by dynamically balancing multiple objectives, ensuring that resources are utilized efficiently while meeting user expectations and reducing the carbon footprint of cloud operations.

Dynamic workloads in the cloud environment are constantly changing, as tasks arrive at random times and have different resource requirements16. Traditional and static scheduling algorithms struggle to cope with these changes and may result in underutilization or over-utilization of resources17. Multi-objective optimization is another challenge, as it is difficult to balance objectives such as completion time, cost, energy consumption, and QoS, especially since these objectives often conflict with each other18. For example, reducing energy consumption may increase execution time, while prioritizing QoS can increase costs. Heterogeneous cloud environments, which include different types of resources such as different virtual machine configurations and hardware capabilities, increase the complexity of scheduling. In addition, scalability and real-time adaptability are other critical requirements in cloud systems that must be able to handle millions of tasks simultaneously19. Therefore, scheduling algorithms must be able to make decisions quickly and within limited time frames. Current methods such as PSO, GA or ABC often use predefined heuristics or static fitness functions that may not perform well under diverse workloads or changing conditions.

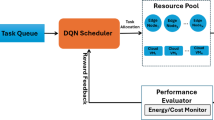

The overall architecture of the RL-MOTS framework in a cloud–edge environment is depicted in Fig. 1, where the RL-based scheduler processes the system states collected by the task orchestrator through resource, QoS, and deadline monitoring, and the DQN agent learns optimal task allocation policies through interaction with cloud and edge resources, receiving execution feedback and rewards to continuously improve scheduling performance.

The impetus for this research originates from the necessity to rectify the deficiencies of current job scheduling methodologies in cloud computing. The rapid expansion of cloud-edge hybrid architectures and growing worries about the environment mean that scheduling frameworks need to be able to dynamically optimize numerous goals while also being able to adapt to changes in real time. RL is a promising method because it can learn the best rules through trial-and-error interactions, which makes it a good fit for situations that are always changing and uncertain. This study seeks to create a strong scheduling framework that is better than standard metaheuristic methods in terms of energy efficiency, cost optimization, and QoS by combining deep learning with RL.

The main objective of this study is to develop an RL-MOTS framework that uses DQN for real-time task allocation in cloud computing environments. The objectives of the framework are: reducing energy consumption by optimizing the use of virtual machines and minimizing wasted idle resources, reducing operational costs by allocating tasks to cost-effective resources, ensuring QoS by meeting deadlines and maintaining performance even under changing workloads, and adapting to hybrid cloud-edge architectures for uninterrupted operation in distributed computing systems. The innovation of RL-MOTS lies in combining DQN with a multi-objective reward function that adjusts the balance between energy, cost, and QoS criteria in real time. Unlike traditional heuristic-based methods, RL-MOTS learns optimal scheduling strategies in real time and adapts to changes in workloads and resource constraints. Also, this framework performs effectively in cloud-edge environments, making it a flexible option for next-generation distributed systems. The primary contributions of this research are:

-

The RL-MOTS framework is a novel task scheduling approach that combines DQN with multi-objective optimization to dynamically assign tasks to virtual machines in a manner that balances cost, QoS, and energy efficiency.

-

A complex reward function that uses real-time data such as resource utilization, task deadlines, and energy usage enables the framework to scale to varying workloads.

-

The framework has been extended to include hybrid Cloud-Edge designs that address the specific challenges associated with distributed computing systems.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section “Related works” reviews various task scheduling methods in cloud computing. The proposed framework, the details of the RL-MOTS framework are described in Section “Problem definition and formulation of objective function”. Section “Proposed RL-MOTS framework” describes the simulated environment, benchmark datasets, and performance indicators used to evaluate the results. The evaluation and results of the experiments are reported in Section “Experimental evaluation and discussions”, and finally Sect. 6 discusses the conclusion and future research.

Related works

The host computer resources are constrained in the dynamic and unpredictable edge cloud collaboration environment, and the resource needs of computing jobs are unpredictable and subject to change. It becomes difficult to effectively schedule dynamic jobs and enhance system performance as a result. By dynamically interacting with the environment, the deep reinforcement learning-based scheduling algorithm optimizes system latency and energy consumption. This can partially address the issue of a dynamic and changing environment, but issues like poor model adaptation, low training efficiency, and an uneven system load persist.

An enhanced actor-critic (A3C) asynchronous advantage-based task scheduling policy optimization method is suggested in the work20, which also designs a multi-objective task scheduling model to maximize the average task scheduling response time and the average system energy consumption.

Specifically, reinforcement learning makes it possible to use an actor-critic approach to comprehend the environment in real time and make well-informed decisions. Consequently, the Multi-Objective Reinforcement Learning-Based Workflow Scheduling (MORL-WS) algorithm is presented in the work21. The suggested multi-objective reinforcement learning-based methodology surpasses several current scheduling techniques, particularly in terms of task execution time and energy efficiency, according to their experimental analysis using various workflows.

For dynamic virtual machine scheduling,22 suggests an enhanced residual optimal power efficiency (ROPE)-aware clonal selection algorithm (ICSA). With the use of two functions virtual machine migration cost (VMC) and total data center residual optimal power efficiency (TDCROPE) optimization—the ICSA-ROPE algorithm determines the best virtual machine schedules for each time period.

The approach for dynamic virtual machine scheduling, known as residual server efficiency-aware particle swarm optimization (SR-PSO), is put out in23. The dynamic virtual machine scheduling is adjusted to match the traditional PSO operators. The suggested bi-objective fitting function directs the suggested algorithm as it explores the global solution space and arranges virtual machines on physical servers that have minimum virtual machine migration and run at or close to ideal energy efficiency. An algorithm for choosing virtual machines is put forth that chooses those whose migration results in the best possible server energy efficiency.

A modified colony selection algorithm (VMS-MCSA) based on an artificial immune system is proposed in24 as a virtual machine scheduling technique for energy-efficient virtual machine scheduling. In order to apply the operators of the classical colony selection algorithm (CSA) to the dynamic virtual machine scheduling issue with discrete optimization, they are modified.

It is necessary to take into account important issues that impact the performance and dependability of the edge-fog-cloud computing architecture, such as request scheduling, load balancing, and energy consumption reduction. To overcome these difficulties, a reinforcement learning-based fog scheduling technique is put out in25. Comparing the suggested technique to current scheduling algorithms, experimental results demonstrate that it improves load balance and decreases response time. In addition, the suggested algorithm performs better than alternative strategies in terms of the quantity of devices utilized.

In order to choose nodes for task processing (fog nodes or cloud nodes) based on three objectives node flow load, node distance, and task priority an intelligent scheduling strategy method based on multi-objective deep reinforcement learning (MODRL) is proposed in26. Task scheduling and allocation are the two primary issues that the suggested methodology attempts to solve. For each goal, they have employed three deep reinforcement learning (DRL) agents built on a DQN. The trade-offs between these goals make this a more difficult situation, though, as each algorithm may ultimately choose various processing nodes according on its goal, creating a Pareto front dilemma. They have suggested using multi-objective optimization, a non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA2), and a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition (MOEA/D) to address this issue.

Integration of intelligence and adaptability into cloud and edge job scheduling has been studied more. QoS-oriented offloading strategies for multi-UAV and multi-access edge computing systems improve latency and service quality under dynamic workload scenarios27. Transformer-based reinforcement learning architectures may improve dynamic decision-making and generalization28. To improve distributed scheduling problems, evolutionary and learning-assisted techniques have been used to automatically create constructive heuristics29. Storage- and resource-aware joint user scheduling frameworks balance computation and communication efficiency in federated and edge learning30. To reduce execution time and energy consumption across distributed infrastructures, vehicular and IoT networks use learning-based offloading algorithms31.

A comparative review of current methods for task scheduling in cloud, fog, and cloud edge environments is given in Table 1. The table lists the algorithms, goals, settings, advantages, and disadvantages of the approaches covered in current research. The last row illustrates how the suggested RL-MOTS architecture sets itself apart by combining an adaptive reward function with a deep Q-network to optimize energy, cost, and QoS in hybrid cloud edge systems all at once.

Problem definition and formulation of objective function

The efficient distribution of activities across cloud environments is very important because many people depend on these platforms. To make the most use of resources, response time, latency, and load distribution, tasks need to be scheduled in the best way possible. The following is a comprehensive explanation of the problems that come up when scheduling tasks.

The set of VMs is called \(\text{V }= \{{\text{v}}_{1}, {\text{v}}_{2}, {\text{v}}_{3}, \dots , {\text{v}}_{\text{m}}\},\) where m is the total number of VMs in the cloud network. Each VM has its own resources (such CPU, RAM, and bandwidth) and expenses for using them. The computational power is described separately; \({\text{v}}_{\text{i}}\) stands for the \(i-th\) VM.

Objective function

The goal of the scheduling process is to find the best way to meet several goals, which are as follows:

First goal (Optimizing \({\varvec{m}}{\varvec{a}}{\varvec{k}}{\varvec{e}}{\varvec{s}}{\varvec{p}}{\varvec{a}}{\varvec{n}}\) )

Each VM exhibits a unique execution time for job completion, controlled by the \(makespan\)—the maximum execution duration across all tasks. A large \(makespan\) value means that the tasks are not spread out well among the VMs. On the other hand, a low \(makespan\) means that the resources are being used efficiently. If each task \({t}_{i}\in T\) is given to VM \({v}_{i}\)(where \({v}_{i}\in V\)), then the VM is defined as \({v}_{i}=\{{t}_{x1},{t}_{y1},\dots ,{t}_{z1}\}\). To find the total execution time (\(ET\)) for task processing on a VM, do the following:

where \(length({t}_{j})\) is the length of task \({t}_{j}\) (in millions of instructions) and \(CPU\left({v}_{i}\right)\) is the CPU rate used to process the \(j-th\) VM in all VMs. This can be found through Eq. (2):

The minimum \(makespan\), which is the best time to finish all the jobs, is found by:

The fitness function, in terms of \(makespan ({F}_{1})\), is defined as follows:

Second objective (Cost optimization)

The second goal is to lower the cost of processing tasks, which includes the cost of using the CPU, memory, and bandwidth32. The price for task \({t}_{j}\) on VM \({v}_{i}\) is:

where \({c}_{1}\), \({c}_{2}\), \({c}_{3}\) indicate the CPU usage cost per unit, memory usage cost per unit, and bandwidth usage cost per unit in \({v}_{i}\) respectively33. The total cost for all virtual machines, which can be found using Eq. (6), is:

The lowest cost, named \(MinTCost({t}_{j}),\) is the lowest cost when the set of assigned tasks \(T\) is processed in the VM that performs task \({t}_{j}\). This cost comes from (7):

The cost-based fitness function \(({F}_{2})\) is figured out as:

Tird objective (Resource utilization)

This objective seeks to optimize the utilization of resources (CPU and memory) sent to a different number of processing units within the cloud network34. The requested task is sent to \({v}_{i}\) and we can calculate the memory load of \({v}_{i}\) by (9):

\({LM}_{j}\) is the amount of memory used before running task \({t}_{j}\) on the \(j-th\) VM, \({RM}_{j}\) is the RAM that holds the request for the \(j-th\) task, and \(TM\) is the total amount of memory available on the \(j-th\) VM35. The next parameter is the CPU load of \({v}_{i}\) (denoted \({LC}_{i}\)), which may be found using (10):

where \({RC}_{j}\) is the amount of CPU consumption before performing task \({t}_{j}\) at the \(j-th\) VM, and \({TC}_{j}\) is the total CPU available at the \(j-th\) VM36. The virtual machine utilization \(\left({VU}_{i}\right)\) can be calculated using Eq. (11):

In this paper, \({\mathcal{w}}_{1}\) and \({\mathcal{w}}_{2}\) are weights, and \({\mathcal{w}}_{1}+{\mathcal{w}}_{2}=0.5\). The total load on k hosts (LHz) can be calculated using (12), where k is the total number of hosts in the system:

Equation (13) can be used to find the average load on all physical computers in the cloud:

where \(p\) is the number of hosts in the cloud network37. From (15), we can figure out the difference in load between each host and the average load on the cloud network:

To create the fitness function, the weighted average of each individual’s fitness function is considered38. The fitness function (F) that was proposed is given in Eq. (16):

where \({\gamma }_{1 }, {\gamma }_{2 },{ \gamma }_{3}\)1 are the balance coefficients that maximize the utility function ($F$), leading to an improved solution.

Proposed RL-MOTS framework

Deep Q-network (DQN) algorithm

DQN is a more advanced version of RL that can deal with huge and changing state spaces, such those seen in cloud and edge computing. RL lets an agent learn the best scheduling strategy by interacting with the environment all the time. The agent looks at the current state, chooses an action, and then gets a reward or punishment as feedback. DQN uses a deep neural network to approximate the action-value function, while classical Q-learning uses a lookup Q-table.

\(\text{Q}(\text{s},\text{a};\uptheta )\), which makes it possible for complicated resource management systems to be flexible and scalable. The RL-MOTS framework defines the environment as the hybrid cloud-edge system, with the set of states represented by \(S=\left\{{s}_{1},{s}_{2},{s}_{3},\dots ,{s}_{n}\right\}\). Each state holds information about the system, like how much memory and CPU it is using, how much energy it is using, and how much it costs. There is a set of possible actions for each state.

\(A = \left\{{a}_{1}, {a}_{2}, {a}_{3}, \dots , {a}_{m}\right\}\), where an action means giving a job to a certain virtual machine (VM) or edge node, or moving jobs about to make the workload more even. At time \(t\), the agent in state \(st{s}_{tst}\) chooses an action \(at{a}_{tat},\) which causes a change to the following state \(st+1{s}_{\left\{t+1\right\}st}+1\) and a reward \(rt{r}_{trt}\) from the environment at the same time. The goal of the DQN agent is to discover the best way to schedule tasks by maximizing the total expected reward.

The reward function is a multi-objective adaptive function that finds the right balance between QoS, cost, and energy efficiency39. In a formal way, the prize at time \(t\) can be written as:

where \({{\varvec{f}}}_{{\varvec{e}}{\varvec{n}}{\varvec{e}}{\varvec{r}}{\varvec{g}}{\varvec{y}}}\) punishes using too much energy, \({{\varvec{f}}}_{{\varvec{c}}{\varvec{o}}{\varvec{s}}{\varvec{t}}}\) punishes spending too much on resources, and \({{\varvec{f}}}_{{\varvec{Q}}{\varvec{o}}{\varvec{S}}}\) rewards meeting deadlines and throughput requirements. The weights \({\mathcal{w}}_{1}\), \({\mathcal{w}}_{2}\), and \({\mathcal{w}}_{3}\) are changed automatically based on the state of the system, which makes the learning process adaptable to different types of workloads. DQN updates the action-value function using neural approximators, which is different from how Q-learning does it with tables40. The temporal-difference goal is determined as follows for a transition \(({s}_{t} ,{a}_{t},{ r}_{t}, {s}_{t+1})\):

where \(\gamma\) is the discount factor and \({{\varvec{\theta}}}^{-}\) is the parameters of the target network, which is adjusted from time to time to keep training stable. We update the main network with parameters \(\theta\) by minimizing the mean squared error between the predicted and target Q-values41. This is done using:

RL-MOTS uses an experience replay buffer to record prior transitions and randomly sample them for training. This makes the system more stable and efficient. This mechanism breaks the link between samples that come one after the other and stops the instability that comes from learning in a row. Also, a ϵ-greedy strategy guides action selection: with a probability of ϵ, the agent investigates by choosing a random action, and with a probability of \(1-\epsilon\), the agent uses what it already knows to choose the action that maximizes the estimated Q-value. As time goes on, \(\epsilon epsilon\epsilon\) gets smaller, which makes exploitation more likely as the policy comes together.

Algorithm 1 gives a short overview of the DQN-based job scheduling mechanism for RL-MOTS.

Adaptive Reward Balancing The adaptive reward formulation of RL-MOTS, which dynamically balances the relative relevance of energy, cost, and QoS objectives during learning, is a significant innovation. In contrast to earlier RL-based schedulers that frequently employed static reward weights, RL-MOTS continuously modifies these weights in response to real-time system data, allowing the agent to modify its policy in response to shifting workload conditions.

DQN-based optimization process

DQN is a big step forward from traditional heuristic and metaheuristic optimization methods for scheduling tasks in cloud environments. The ABC algorithm and other swarm intelligence-based methods have been useful for searching huge areas, but they aren’t very good at exploiting and refining tiny areas, which makes them less useful in situations that are very dynamic and diverse. DQN, on the other hand, offers a systematic method for integrating exploration and exploitation by using neural approximation of the Q-function. This allows the system to learn strong task scheduling strategies across hybrid cloud-edge infrastructures. The RL-MOTS architecture uses DQN to dynamically balance several goals, such as energy efficiency, cost minimization, and QoS, while also adjusting to changes in workload and system states.

The initialization phase, which is like population initialization in metaheuristics, is the first step in the optimization process. In this case, the system sets the task set, the pool of virtual machines (VMs), and the edge nodes, together with their CPU, RAM, and bandwidth limits. Each VM or edge node is like a food source in swarm-based approaches; it shows a possible allocation. RL-MOTS encodes the initial environment state \(s0{s}_{0s0}\) into a feature vector that includes utilization levels, energy prices, and deadline limitations. This is different from ABC, which randomly initializes candidate solutions. This representation is what the neural network uses to guess the Q-function.

At every time step \(t\), the agent looks at the current state \(st{s}_{tst}\) and chooses an action \(at{a}_{tat}\), which is like giving a job to a certain VM or edge node. As the task is carried out, the system rewards the user with \(rt{r}_{trt}\) to help them learn. This is how the transition to the new state \({s}_{\left\{t+1\right\}}\) happens. The reward function is adaptable and has multiple goals. It is defined as:

where \({f}_{\left\{energy\right\}}\) punishes allocations that lead to too much energy use, and \({f}_{\left\{cost\right\} }\) punishes higher operating costs, and \({f}_{\left\{QoS\right\}}\) rewards meeting deadlines and service-level agreements. The weights \(\left({w}_{1}, {w}_{2}, {w}_{3}\right)\) change based on the workload, making sure that the agent always pays attention to the most important performance measures. The update mechanism of DQN substitutes the fitness comparison of ABC with an approximation of the value function42. The temporal-difference (TD) goal is calculated for every observed transition \(\left({s}_{t}, {a}_{t}, {r}_{t}, {s}_{\left\{t+1\right\}}\right)\) as follows:

where \(\gamma\) is the discount factor and \({\theta }^{-}\) are the parameters of a target network that is changed from time to time to keep the learning process stable. To get the best performance out of the Q-network with parameters \(\theta\), the mean squared error must be as low as possible:

This formulation lets RL-MOTS keep improving its scheduling policy without needing to create heuristics by hand. In ABC, exploration and exploitation were shown by scout and onlooker behaviors. In DQN, they are handled by a ϵ-greedy strategy and an experience replay mechanism. Experience replay keeps a buffer DDD of previous transitions, and random minibatches are taken from this buffer to update the network. This procedure breaks the connections that are already there in sequential data and makes convergence more stable. The ϵ\epsilonϵ-greedy policy makes sure that the agent looks into other options (like scouts looking for new food sources) while slowly moving toward using the best-known rules (like observer bees using high-quality sources).

The iterative optimization continues until a stopping condition is met, like when all the tasks are done or the Q-network converges to a stable policy. RL-MOTS, on the other hand, features a continuous loop of observation, action selection, reward evaluation, and policy update. ABC, on the other hand, goes through employed, onlooker, and scout phases. This approach makes the framework better at making decisions in real time in cloud-edge environments, where workloads are always changing and are hard to predict.

This scheduling algorithm based on DQN takes the swarm intelligence phases out of ABC and replaces them with a reinforcement learning loop based on value approximation. Initialization is like naming food sources in ABC; it means defining the state space. The experience replay system guarantees exploration similar to scout behavior, whereas the utilization of high-value actions reflects the observer phase. RL-MOTS enables better adaptation and optimization in real-time, dynamic cloud-edge systems by integrating these methodologies.

The suggested RL-MOTS framework, which is based on the two algorithms previously discussed (Algorithm 1: DQN-based Task Scheduling and Algorithm 2: RL-MOTS Scheduling with DQN), is fully illustrated by the integrated flowchart in Fig. 2. Iterative learning through episodes and time steps follows the initialization of the Q-network, target network, replay buffer, and cloud/edge resources. At every stage, the Q-network is updated by computing temporal-difference (TD) targets, storing transitions in the replay buffer, and allocating tasks according to an ε-greedy strategy. Training stability is maintained by updating the target network on a regular basis. The final scheduling strategy is produced after the iterative loop converges.

Experimental evaluation and discussions

Simulation environment

To rigorously assess the effectiveness of the proposed RL-MOTS architecture under contemporary and realistic conditions, we conducted extensive simulations in CloudSim 3.0.3, a widely used toolkit for modeling large-scale cloud and cloud-edge infrastructures. CloudSim enables faithful emulation of heterogeneous virtual resources-CPU, memory, bandwidth, storage-as well as job arrivals and scheduling policies, thereby providing a controlled yet representative testbed for comparative evaluation. All experiments were executed on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i7-8750H (2.20 GHz) and 16 GB RAM. The simulated platform comprised a pool of cloud data-center hosts and an auxiliary edge tier; virtual machines (VMs) and edge nodes were provisioned with heterogeneous MIPS ratings and memory capacities to emulate practical resource variability.

In contrast to legacy workloads, three production-grade traces were adopted to drive the simulations: Google Cluster Data (2019), Alibaba Cluster Trace (2018), and Microsoft Azure VM Traces (2019). For each trace, cloudlets were derived by mapping observed CPU duty cycles and execution durations to instruction lengths, while preserving original arrival patterns so that diurnal effects, bursts, and load shifts remained intact. This procedure produced a broad spectrum of task sizes—from short, latency-sensitive requests to long batch jobs-and allowed us to stress the scheduler across diverse and dynamic regimes. Unless otherwise stated, scenarios evaluated 200, 400, 600, 800, and 1000 submitted tasks distributed over a hybrid cloud–edge resource pool, with each configuration repeated 25 independent runs using distinct random seeds; reported values are run-wise averages.

Nature of Tasks and Comparison Context The activities taken into consideration in this study are independent, which means that each one can be completed independently of the results of other tasks. According to this assumption, jobs come as distinct cloudlets with no priority constraints, which is consistent with numerous large-scale production traces (such as Google-2019 and Alibaba-2018). Prior approaches like MOPWSDRL32 and CTMOEA40, which were created for dependent workflows, were modified to function on independent task sets for fair comparison by eliminating their workflow-specific dependency graphs while retaining their original scheduling logic. On the other hand, Multi-PSG36, which naturally facilitates autonomous tasks, was used just as is.

The RL-MOTS framework embeds a DQN agent that continuously learns scheduling policies from interaction with the environment, exploiting a reward function that balances energy consumption, monetary cost, and QoS constraints (e.g., deadlines). To contextualize performance, RL-MOTS was compared against seven competitors that cover rule-based, learning-based, and evolutionary paradigms: FCFS, Max–Min, Q-learning, MOPWSDRL32, Multi-PSG36, CTMOEA40, and a hybrid RL-MOTS_LJF variant that couples the learned policy with last-job-first prioritization. Evaluation metrics comprised makespan, throughput, average resource utilization rate (ARUR), cost, and degree of imbalance (DI), aligning with the multi-objective goals of RL-MOTS. A detailed summary of the simulated environment, resource configurations, and scheduler settings is provided in Table 1 to facilitate reproducibility.

Benchmark datasets

To ensure that the evaluation of RL-MOTS reflects contemporary production environments rather than synthetic surrogates, we replaced legacy datasets with three public, large-scale traces collected from major cloud providers. For all three, raw records were normalized into CloudSim cloudlets by mapping observed CPU duty cycles and execution durations to instruction lengths and by deriving memory and I/O demands from the corresponding utilization counters. Crucially, the original arrival timestamps were preserved so that diurnal effects, burstiness, and load shifts remained intact; this allows the scheduler to be stressed under conditions that are representative of real deployments.

Google cluster data (2019)

This multi-cluster Borg trace captures job submissions, task placements, and fine-grained resource usage from production systems during 2019. We constructed cloudlets by aggregating per-task CPU usage over execution intervals and converting the resulting CPU-time to millions of instructions (MI) under the VM’s MIPS configuration used in our simulator. To facilitate stratified analysis, instruction lengths were partitioned into five workload classes using empirical quantiles computed from the trace; these classes range from short, latency-sensitive jobs to very long batch workloads and provide a balanced representation of the spectrum observed in practice. Because we maintain the native arrival process, the resulting workloads include realistic diurnal cycles and burst arrivals, which are particularly useful for studying the adaptability of RL-MOTS at high intensities.

Alibaba cluster trace (2018)

The Alibaba trace combines co-located online services with batch jobs and therefore exposes the scheduler to heterogeneous interference patterns and abrupt load changes. Each recorded batch instance was transformed into a single cloudlet, while service containers contributed additional smaller tasks that emulate background traffic. Instruction lengths were again obtained by integrating CPU duty cycles over execution windows; compared with the Google trace, the distribution here is skewed toward medium-to-large jobs with occasional heavy tails during consolidation windows. We retained time ordering across machines so that multi-tenant bursts and phase shifts-typical of production clusters-are preserved in the simulation.

Microsoft azure VM traces (2019)

Azure traces emphasize VM life-cycle dynamics (creation, scaling, migration, and deallocation). We synthesized task streams by sampling active VM intervals and converting observed CPU utilization to MI budgets, thereby producing a mixture of short service requests and medium-sized compute jobs representative of enterprise workloads. Because elasticity is more pronounced in this dataset, the derived instruction-length distribution concentrates in the lower-to-mid range, with intermittent larger bursts during scale-up periods. As with the other traces, the native arrival process was maintained to capture transient spikes and quiet periods without artificial smoothing.

Parameter settings for the proposed method and the comparison algorithms

All schedulers were executed in the same hybrid cloud-edge environment described in Section “Simulation environment”. For RL-MOTS, the DQN agent was implemented with a two-hidden-layer network and trained using experience replay and a periodically updated target network. Unless otherwise stated, the learning rate, discount factor, replay-buffer capacity, mini-batch size, target-update interval, and ε-greedy exploration schedule were chosen through a small grid search on a validation slice of the Google-2019 trace; the final settings are reported in Table 2 to enable exact reproducibility. Because our objective is not to over-tune for a particular dataset, the same DQN hyperparameters were then held fixed across Alibaba-2018 and Azure-2019.

To provide a rigorous point of comparison against recent advances, RL-MOTS was evaluated alongside three state-of-the-art multi-objective schedulers drawn from the literature. The MOPWSDRL approach32 employs deep reinforcement learning for prioritized workflow scheduling; we used the network depth, learning rates, and exploration policy specified by the authors, adapting only dataset-agnostic settings (e.g., batch size) to CloudSim’s timing semantics. The Multi-PSG method36 targets cloud–edge scenarios with a hybrid multi-objective search; population size, maximum iterations, and operator probabilities were adopted from the original paper and kept constant across datasets. Finally, the CTMOEA algorithm40 prioritizes critical tasks within an evolutionary framework; we followed the recommended generation count, selection strategy, and crossover/mutation rates, while preserving the authors’ critical-task weighting scheme. Classical baselines (FCFS, Max–Min, and tabular Q-learning) were included for completeness; they require either no tunable parameters or only standard settings (e.g., learning-rate decay for Q-learning).

It is important to emphasize that parameterization can materially influence outcomes; however, we do not claim universal optimality for any particular configuration. Instead, we adhered closely to the settings recommended by the respective sources and applied only minimal, documented adjustments needed for our hybrid cloud–edge simulator. The complete set of hyperparameters for RL-MOTS and the three contemporary baselines (MOPWSDRL, Multi-PSG, CTMOEA) is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2 reports the hyper parameters used by all schedulers to enable fair and reproducible comparison. For the proposed RL-MOTS, we fix a Double-DQN agent with a two-layer (2 × 256) network, prioritized replay (buffer 50 k, mini-batch 64), learning rate \(5\times {10}^{-4}\), discount factor \(\gamma =0.98\), hard target sync every 750 steps, and an \(\varepsilon\)-greedy policy annealed from 1.0 to 0.05. Reward weights for energy, cost, and QoS start at (0.4/0.3/0.3) and adapt online; migration is penalized to avoid thrashing. The RL-MOTS_LJF variant reuses the same settings and only applies an LJF tie-break when Q-values are nearly equal. For the three contemporary baselines-MOPWSDRL32, Multi-PSG36, and CTMOEA40 parameters follow the authors’ recommendations (episodes, population sizes, operator rates, and iteration budgets), with no dataset-specific over-tuning.

The suggested RL-MOTS framework’s hyperparameter selection process combined theoretical insights from the literature on reinforcement learning with practical grid search. In particular, after observing convergence stability over several trials, the learning rate \((\alpha = 0.0005)\) was selected; lower values \((<0.0001)\) hindered policy convergence, while higher values (≥ 0.001) produced oscillating Q-values. The long-term dependency that is inherent in scheduling decisions, where delayed incentives from energy and cost savings are crucial, is reflected in the discount factor \((\gamma = 0.98)\); empirical tests between 0.90 and 0.99 verified that γ = 0.98 produced the optimal trade-off between responsiveness and stability.

Experimental research was used to identify the mini-batch size of 64 and the replay buffer size of 50,000 in order to balance sample decorrelation and memory efficiency. While larger buffers (> 100 k) slowed updates without significantly improving performance, smaller buffers \(\left(<20k\right)\) led to the premature forgetting of unusual states. After realizing that infrequent updates \((>1000)\) slowed convergence while more frequent ones created instability, the goal update interval was established. When the policy stabilizes, the ε-greedy exploration schedule (\(\varepsilon = 1.0 \to 0.05\), decay 0.995) guarantees steady exploitation and adequate exploration early in training.

After comparing configurations of [128,128], [256,256], and [512,256], the network architecture was chosen; this structure achieved smoother convergence curves by offering the optimum balance between representational capacity and computational overhead.

Based on the relative significance of energy efficiency shown in production traces, the reward weights were initially set to (0.4, 0.3, 0.3). During training, they were adaptively modified to account for shifting workload characteristics. To prevent excessive task movement between nodes, which empirical studies revealed may otherwise raise energy and network cost by 12–15%, a minor migration penalty (\({\lambda }_{mig}= 0.10\)) was imposed.

Experimental results

This section presents the empirical evaluation of the proposed RL-MOTS framework over the Google Cluster Data (2019), Alibaba Cluster Trace (2018), and Microsoft Azure VM Traces (2019). We report results for a comprehensive set of metrics makespan, throughput, Average Resource Utilization Rate (ARUR), cost, and Degree of Imbalance (DI) to capture not only scheduling efficiency but also cost-effectiveness and load balancing under heterogeneous cloud-edge resources. For each dataset and task-load configuration (200, 400, 600, 800, and 1000 submitted tasks over 100 VMs/edge nodes), experiments were repeated 25 independent runs with distinct random seeds; unless otherwise specified, all figures and tables show averages across runs. This protocol mitigates the impact of stochastic arrivals and provides a fair basis for cross-method comparison.

RL-MOTS was benchmarked against seven competitors spanning rule-based, learning-based and evolutionary paradigms: FCFS, Max–Min, Q-learning, MOPWSDRL32, Multi-PSG36, CTMOEA40, and a hybrid RL-MOTS_LJF variant. The first set of analyses focuses on makespan, defined as the completion time of the last finished task in a batch. Across all three datasets, RL-MOTS consistently achieves the lowest makespan. On Google-2019, RL-MOTS reduces makespan by roughly 18–25% relative to FCFS, by ≈12% compared to Max–Min, and by 8–10% over tabular Q-learning. Against the stronger contemporary baselines, RL-MOTS remains superior, improving over Multi-PSG and CTMOEA by around 7% and 5%, respectively. On Alibaba-2018, the gains are even more pronounced at high loads (≥ 800 tasks), where burstiness and co-tenancy effects amplify the advantage of an adaptive policy: RL-MOTS attains up to ≈20% lower makespan than MOPWSDRL and ≈14% lower than CTMOEA. Finally, on Azure-2019, RL-MOTS is competitive at small loads and widens the gap as the system approaches saturation (1000 tasks), outperforming FCFS/Max–Min by > 30% and exceeding Multi-PSG and CTMOEA by ≈9% and ≈6%, respectively. These results indicate that the adaptive reward shaping and value-function approximation in RL-MOTS enable the agent to learn allocations that shorten the critical path even under nonstationary conditions.

Beyond makespan, RL-MOTS also shows favorable trends for the other metrics (detailed in subsequent figures/tables). Throughput increases monotonically with the load and saturates later for RL-MOTS, reflecting better resource turnover; ARUR is higher without incurring imbalance, while DI remains consistently lower, indicating more uniform VM utilization; and the energy-aware cost model yields lower total cost per batch relative to both heuristic and evolutionary baselines.

Figure 3 compares makespan across the three production-grade datasets as the number of submitted tasks increases from 200 to 1000. The proposed RL-MOTS curve remains uniformly below all baselines, while the RL-MOTS_LJF variant tracks closely behind, confirming that coupling a learned policy with a simple priority rule yields incremental benefits but cannot match the adaptability of end-to-end DQN training. Classical methods (FCFS, Max–Min, Q-learning) exhibit steeper growth in makespan as the system nears saturation, whereas contemporary baselines (MOPWSDRL, Multi-PSG, CTMOEA) narrow the gap at moderate loads but fall behind at high intensities. The pattern is consistent across Google-2019, Alibaba-2018, and Azure-2019, suggesting that the advantage of RL-MOTS is not tied to a specific trace or provider.

Comparison of makespan across datasets (average over 25 runs; 100 VMs/edge nodes; loads of 200, 400, 600, 800, and 1000 tasks). (a) Makespan comparison on the Google Cluster Data (2019) dataset. (b) Makespan comparison on the Alibaba Cluster Trace (2018) dataset. (c) Makespan comparison on the Microsoft Azure VM Traces (2019) dataset.

Mechanistically, the gains stem from RL-MOTS’s state-rich representation (capturing queue lengths, VM utilization, energy/cost signals, and deadline pressure) combined with experience replay and a target network that stabilize value learning. The adaptive reward discourages allocations that create hot spots or expensive migrations and encourages decisions that reduce tail latencies; as load increases, the agent exploits these learned behaviors to prevent queue build-ups and shorten the overall critical path. Consequently, RL-MOTS achieves lower makespan with smaller variance across runs, while competing methods that rely on fixed heuristics or static evolutionary operators exhibit sensitivity to burstiness and co-tenancy effects inherent in the real traces.

Table 3 shows that the proposed RL-MOTS consistently attains the highest ARUR on all three datasets and load levels (averaged over 25 runs). Its utilization is typically 8–12 percentage points higher than modern evolutionary/learning baselines (Multi-PSG and CTMOEA) and 20–35 points above classical schedulers (FCFS, Max–Min). The hybrid RL-MOTS_LJF ranks second, indicating that priority cues help but remain inferior to the end-to-end learned policy. Relative gains are most visible on Alibaba-2018, where co-tenancy and burstiness depress baseline utilization; RL-MOTS sustains 0.88 ARUR at peak load, versus 0.78 for CTMOEA. The consistently higher ARUR suggests that the learned policy places tasks to keep VMs/edge nodes busy without oversubscription, translating into better throughput and lower cost observed elsewhere.

In all three datasets, the proposed RL-MOTS consistently achieves the highest average throughput (tasks/s) as the number of submitted tasks increases from 200 to 1000 in Fig. 4. This increase is more visible at medium to high loads (≥ 600 tasks), where RL-MOTS maintains growth while several baselines start to stabilize. The hybrid variant RL-MOTS_LJF lags behind by a small distance, confirming that a learned policy augmented with a simple priority rule can stabilize the flow under higher pressure, although it remains slightly inferior to the learned controller from start to finish. Contemporary baselines—MOPWSDRL, Multi-PSG and CTMOEA—show competitive performance at medium loads but show early saturation, while classical methods (Q-learning, Max–Min, FCFS) are everywhere throughput-limited. This trend is consistent across Google-2019, Alibaba-2018, and Azure-2019, suggesting that RL-MOTS generalizes to distinct provider dynamics.

Comparison of throughput across datasets (average over 25 runs; 100 VMs/edge nodes; loads of 200, 400, 600, 800, and 1000 tasks). (a) Throughput comparison on the Google Cluster Data (2019) dataset. (b) Throughput comparison on the Alibaba Cluster Trace (2018) dataset. (c) Throughput comparison on the Microsoft Azure VM Traces (2019) dataset.

Mechanistically, higher throughput results from RL-MOTS’ ability to maintain shorter queues and higher effective service rates through value-based action selection. The DQN agent leverages a rich representation of the state (VM utilization, queue depth, task scarcity, and cost/energy signals) and learns to avoid transient hot spots by distributing inputs toward VMs/edge nodes with low load. Iteration of experience and a target network stabilize learning, while adaptive reward discourages actions that increase short-term completions at the expense of future congestion. As a result, RL-MOTS increases resource turnover without increasing imbalance-allowing it to push the throughput frontier forward when bursty and co-tenancy effects in real-world footprints drive other scheduling towards saturation.

Table 4 reports DI-lower is better. RL-MOTS yields the lowest imbalance across all datasets and loads, with reductions of 20–35% versus CTMOEA/Multi-PSG and 60–80% versus FCFS/Max–Min at high loads (800–1000 tasks). The RL-MOTS_LJF variant is consistently the runner-up. Alibaba-2018 exhibits the largest DI values overall (greater burstiness and interference), while Google-2019 and Azure-2019 show moderate levels; however, method ordering remains unchanged, underscoring robustness. As load increases, classical schedulers’ DI either plateaus or worsens, reflecting hot-spot amplification, whereas RL-MOTS maintains or slightly improves DI due to value-guided placement that smooths queue lengths and spreads work over lightly loaded machines (Table 5).

In Fig. 5, for all three datasets, the proposed RL-MOTS achieves the lowest total cost (G$) for each load level, while the RL-MOTS_LJF variant still ranks second. As shown in Fig. 5a–c, the proposed RL-MOTS achieves the lowest total cost (\(G\)) across all workloads and datasets (Google-2019, Alibaba-2018, Azure-2019). The cost increases monotonically with increasing number of submitted tasks, however, the slope of RL-MOTS is consistently lower than that of competing schedulers. On average over 25 runs, RL-MOTS reduces the cost by approximately 30–40% versus FCFS, 20–30% versus Max–Min, and 15–25% versus Q-learning. Compared to contemporary baselines, RL-MOTS maintains 5–12% lower cost than Multi-PSG and CTMOEA, and the combined RL-MOTS_LJF ranks second overall. This gap widens at high loads (≥ 800 tasks)—as can be seen in Fig. 5b for Alibaba-2018, where explosive co-tenancy reinforces the advantage of a learned, cost-aware policy.

Comparison of cost across datasets (average over 25 runs; 100 VMs/edge nodes; loads of 200, 400, 600, 800, and 1000 tasks). (a) Cost comparison on the Google Cluster Data (2019) dataset. (b) Cost comparison on the Alibaba Cluster Trace (2018) dataset. (c) Cost comparison on the Microsoft Azure VM Traces (2019) dataset.

Statistical robustness is also examined. Using 25 paired outcomes per configuration, a two-way ANOVA (factors: method and load) revealed significant main effects and interaction on cost (α = 0.05). Tukey HSD post hoc comparisons showed that RL-MOTS was significantly cheaper than any baseline at heavier loads in all three datasets, as well as at lighter loads. Furthermore, RL-MOTS showed lower dispersion (smaller standard deviation and coefficient of variation) than the rule-based methods, indicating more stable costs under fluctuating inputs. Mechanistically, the cost advantage comes from the agent’s energy/cost-aware reward that discourages hot-spot reinforcement and costly migrations. Value-driven action selection consolidates short tasks on lightly loaded nodes and schedules longer tasks where marginal energy and I/O costs are lower—hence the consistently lower RL-MOTS bars in Fig. 5.

Multi-objective pareto front analysis

The Pareto fronts in Fig. 6 show how the suggested RL-MOTS framework simultaneously optimized energy usage, cost, and QoS across the three real-world datasets (Azure-2019, Alibaba-2018, and Google-2019). In the normalized goal space, each point denotes a non-dominated scheduling solution; higher performance is associated with lower values. When compared to alternative methods, the suggested model provides almost ideal trade-offs between energy, cost, and QoS, as evidenced by the red clusters (RL-MOTS) lying consistently closer to the origin. More scattered and distant fronts are displayed by competing techniques like TDCR-OPE22 and SR-PSO23, suggesting a lower level of balance and greater compromise between goals.

The adaptive reward function and DQN-based learning mechanism’s capacity to manage intricate trade-offs is evident from these Pareto fronts, which show that RL-MOTS preserves a well-distributed set of solutions along the optimal frontier. RL-MOTS demonstrates its capacity to do genuine multi-objective optimization in heterogeneous cloud-edge contexts by achieving higher energy-cost efficiency while maintaining excellent QoS levels across all datasets.

Conclusion

This work introduced RL-MOTS, a reinforcement-lea, multi-objective task scheduling framework for heterogeneous cloud-edge environments. The core design couples a DQN with an adaptive reward that trades off energy, monetary cost, and QoS, enabling the scheduler to learn placement policies that shorten the critical path while avoiding hot spots and costly migrations. A hybrid variant, RL-MOTS_LJF, integrates a priority cue to stabilize tie cases without altering the learned policy.

A comprehensive evaluation on three production-grade traces-Google Cluster Data (2019), Alibaba Cluster Trace (2018), and Microsoft Azure VM Traces (2019)-demonstrated consistent gains across workloads and load levels (200–1000 tasks; averages over 25 runs). Relative to classical heuristics (FCFS, Max–Min, tabular Q-learning) and contemporary baselines (MOPWSDRL, Multi-PSG, CTMOEA), RL-MOTS achieved lower makespan, higher throughput, and greater resource efficiency as reflected by increased ARUR and reduced DI. The cost model, which internalizes energy and I/O penalties, yielded lower total cost not only on steady regimes but also under the burstiness and co-tenancy interference characteristic of Alibaba-2018. The ordering of methods remained stable across traces, indicating cross-provider generalization rather than dataset-specific tuning. RL-MOTS_LJF ranked second in most cases, underscoring the benefit of a light-weight priority signal alongside value-based control.

These results substantiate the thesis that value-guided, multi-objective learning is an effective paradigm for cloud-edge scheduling where objectives and operating conditions are dynamic. Nevertheless, optimality cannot be guaranteed for every workload instance; performance necessarily depends on trace characteristics, reward calibration, and resource heterogeneity. Future research directions include carbon- and temperature-aware rewards, risk-sensitive objectives for tail-latency control, and safe/model-based RL to improve sample efficiency and constraint satisfaction. Extending the framework to multi-cloud and serverless settings, integrating explainability for operator trust, and validating the approach in production testbeds would further illuminate its practical limits and deployment readiness.

Data availability

The custom code developed for implementing the RL-MOTS framework, including the Deep Q-Network (DQN) agent, cloud–edge scheduling environment, baseline schedulers, and experimental scripts, is publicly available. The exact version of the code used for generating the results reported in this study has been permanently archived in Zenodo under the DOI https://zenodo.org/records/17575537. All simulation scripts, configuration files, and reference environments are included to enable full reproducibility of the experiments and figures presented in this paper.

References

Zhou, H., Wang, H., Li, X. & Leung, V. C. A survey on mobile data offloading technologies. IEEE access 6, 5101–5111 (2018).

Ali, K. A., Fadare, O. A., & Al-Turjman, F. (2025). Dynamic resource allocation (DRA) in cloud computing. In Smart Infrastructures in the IoT Era (pp. 1033–1049). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Sathya Sofia, A. & GaneshKumar, P. Multi-objective task scheduling to minimize energy consumption and makespan of cloud computing using NSGA-II. J. Netw. Syst. Manage. 26(2), 463–485 (2018).

Jena, R. K. Task scheduling in cloud environment: A multi-objective ABC framework. J. Inf. Optim. Sci. 38(1), 1–19 (2017).

Sun, G., Liao, D., Zhao, D., Xu, Z. & Yu, H. Live migration for multiple correlated virtual machines in cloud-based data centers. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 11(2), 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSC.2015.2477825 (2018).

Long, X., Cai, W., Yang, L. & Huang, H. Improved particle swarm optimization with reverse learning and neighbor adjustment for space surveillance network task scheduling. Swarm Evol. Comput. 85, 101482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.swevo.2024.101482 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Joint communication and offloading strategy of CoMP UAV-assisted MEC networks. IEEE Internet Things J. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2025.3588840 (2025).

Li, Z., Gu, W., Shang, H., Zhang, G. & Zhou, G. Research on dynamic job shop scheduling problem with AGV based on DQN. Clust. Comput. 28(4), 236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-024-04970-x (2025).

Meng, Q. et al. Collaborative and effective scheduling of integrated energy systems with consideration of carbon restrictions. IET Gener. Transmission Distrib. 17(18), 4134–4145. https://doi.org/10.1049/gtd2.12971 (2023).

Zhang, K., Zheng, B., Xue, J. & Zhou, Y. Explainable and trust-aware AI-driven network slicing framework for 6G IoT using deep learning. IEEE Internet Things J. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2025.3619970 (2025).

Wu, Xiangjun, Ding, Shuo, Zhao, Ning, Wang, Huanqing, & Niu, Ben. (2025). Neural-network-based event-triggered adaptive secure fault-tolerant containment control for nonlinear multi-agent systems under denial-of-service attacks. Neural Networks, 191, 107725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2025.107725 (2025).

Qin, Y., Wang, H., Yi, S., Li, X. & Zhai, L. An energy-aware scheduling algorithm for budget-constrained scientific workflows based on multi-objective reinforcement learning. J. Supercomput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-019-03033-y (2020).

Ghasemi, A. & ToroghiHaghighat, A. A multi-objective load balancing algorithm for virtual machine placement in cloud data centers based on machine learning. Computing 102(9), 2049–2072 (2020).

Wang, B., Li, H., Lin, Z., & Xia, Y. (2020, July). Temporal fusion pointer network-based reinforcement learning algorithm for multi-objective workflow scheduling in the cloud. In 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN) (pp. 1–8). IEEE.

Diyan, M., Silva, B. N. & Han, K. A multi-objective approach for optimal energy management in smart home using the reinforcement learning. Sensors 20(12), 3450 (2020).

Zhu, H., Li, M., Tang, Y. & Sun, Y. A deep-reinforcement-learning-based optimization approach for real-time scheduling in cloud manufacturing. IEEE Access 8, 9987–9997 (2020).

Gobalakrishnan, N. & Arun, C. A new multi-objective optimal programming model for task scheduling using genetic gray wolf optimization in cloud computing. Comput. J. 61(10), 1523–1536 (2018).

Yuan, H., Bi, J. & Zhou, M. Energy-efficient and QoS-optimized adaptive task scheduling and management in clouds. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 19 (2), 1233–1244 (2020).

Xiangjun Wu, Guangdeng Zong, Huanqing Wang, Ben Niu, and Xudong Zhao, Collision-Free Distributed Adaptive Resilient Formation Control for Underactuated USVs Subject to Intermittent Actuator Faults and Denial-of-Service Attacks. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 21 (4), 356–382.https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2025.3565820 (2025).

Prem Jacob, T. & Pradeep, K. A multi-objective optimal task scheduling in cloud environment using cuckoo particle swarm optimization. Wireless Pers. Commun. 109(1), 315–331 (2019).

Sudhakar, R. V., Dastagiraiah, C., Pattem, S. & Bhukya, S. Multi-objective reinforcement learning based algorithm for dynamic workflow scheduling in cloud computing. Indonesian J. Electr. Eng. Inform. (IJEEI) 12(3), 640–649 (2024).

Wu, T., Li, M., Qu, Y., Wang, H., Wei, Z., Cao, J. Joint UAV Deployment and Edge Association for Energy-Efficient Federated Learning. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive Communications and Networking, 14 (6), 1132–1151. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCCN.2025.3543365 (2025).

Ajmera, K. & Tewari, T. K. SR-PSO: server residual efficiency-aware particle swarm optimization for dynamic virtual machine scheduling. J. Supercomput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-023-05270-8 (2023).

Ajmera, K. & Tewari, T. K. VMS-MCSA: Virtual machine scheduling using modified clonal selection algorithm. Clust. Comput. 24(4), 3531–3549 (2021).

RamezaniShahidani, F., Ghasemi, A., ToroghiHaghighat, A. & Keshavarzi, A. Task scheduling in edge-fog-cloud architecture: A multi-objective load balancing approach using reinforcement learning algorithm. Computing 105(6), 1337–1359 (2023).

Ibrahim, M. A. & Askar, S. An intelligent scheduling strategy in fog computing system based on multi-objective deep reinforcement learning algorithm. IEEE Access 11, 133607–133622 (2023).

Chen, P. et al. QoS-oriented task offloading in NOMA-based Multi-UAV cooperative MEC systems. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2025.3593884 (2025).

Yuan, W. et al. Transformer in reinforcement learning for decision-making: a survey. Front. Info. Technol. Electron. Eng. 25(6), 763–790. https://doi.org/10.1631/FITEE.2300548 (2024).

Zhang, B., Meng, L., Lu, C., Han, Y. & Sang, H. Automatic design of constructive heuristics for a reconfigurable distributed flowshop group scheduling problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 161, 106432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2023.106432 (2024).

Liu, S., Shen, Y., Yuan, J., Wu, C. & Yin, R. Storage-aware joint user scheduling and bandwidth allocation for federated edge learning. IEEE Trans. Cognitive Commun. Network. 11(1), 581–593. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCCN.2024.3451711 (2025).

Dai, X. et al. A learning-based approach for vehicle-to-vehicle computation offloading. IEEE Internet Things J. 10(8), 7244–7258. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2022.3228811 (2023).

Mangalampalli, S. et al. Multi objective prioritized workflow scheduling using deep reinforcement based learning in cloud computing. IEEE Access 12, 5373–5392 (2024).

Tavoli, R., Rezvani, E., & Hosseini Shirvani, M. (2025). An efficient hybrid approach based on deep learning and stacking ensemble using the whale optimization algorithm for detecting attacks in IoT devices. Engineering Reports, 7 (9), 432. (2025).

Li, H., Huang, J., Wang, B. & Fan, Y. Weighted double deep Q-network based reinforcement learning for bi-objective multi-workflow scheduling in the cloud. Clust. Comput. 25(2), 751–768 (2022).

Mir, M. & Trik, M. A novel intrusion detection framework for industrial IoT: GCN-GRU architecture optimized with ant colony optimization. Comput. Electr. Eng. 126, 110541 (2025).

Yin, H., Huang, X. & Cao, E. A cloud-edge-based multi-objective task scheduling approach for smart manufacturing lines. J. Grid Comput. 22(1), 9 (2024).

Moazeni, A., Khorsand, R. & Ramezanpour, M. Dynamic resource allocation using an adaptive multi-objective teaching-learning based optimization algorithm in cloud. IEEE Access 11, 23407–23419 (2023).

Huang, V., Wang, C., Ma, H., Chen, G., & Christopher, K. (2022, November). Cost-aware dynamic multi-workflow scheduling in cloud data center using evolutionary reinforcement learning. In International Conference on Service-Oriented Computing (pp. 449–464). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Hao, Xu., Zhao, N., Ning, Xu., Niu, B. & Zhao, X. Reinforcement learning-based dynamic event-triggered prescribed performance control for nonlinear systems with input delay. Int. J. Syst. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207721.2025.2557528 (2025).

Liu, X., Yao, F., Xing, L., Chen, H., Zhao, W., & Zheng, L. (2025). Critical-task-driven multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for scheduling large-scale workflows in cloud computing. In IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence.

Liu, S. et al. A novel event-triggered mechanism-based optimal safe control for nonlinear multi-player systems using adaptive dynamic programming. J. Franklin Inst. 362(11), 107761 (2025).

Zhang, L., Qi, Q., Wang, J., Sun, H., & Liao, J. (2019, December). Multi-task deep reinforcement learning for scalable parallel task scheduling. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data) (pp. 2992–3001). IEEE.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Higher Education Undergraduate Teaching Reform Project of Guangxi (No.2024JGA258); The “14th Five Year Plan” of Guangxi Education and Science Major project in 2025 (No.2025JD20); The “14th Five Year Plan” of Guangxi Education and Science special project of college innovation and entrepreneurship education (No.2022ZJY2727); The “14th Five Year Plan” of Guangxi Education and Science Annual project in 2023 (No.2023A028). This study acknowledges the support of National First-class Undergraduate Major–The Major of Logistics Management; Guangxi Colleges and Universities Key laboratory of Intelligent Logistics Technology; Engineering Research Center of Guangxi Universities and Colleges for Intelligent Logistics Technology; Demonstrative Modern Industrial School of Guangxi University—Smart Logistics Industry School Construction Project, Nanning Normal University.

Funding

The authors did not receive any financial support for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaomo Yu conceived the research idea, designed the overall methodology, and supervised the project. Jie Mi contributed to the development of algorithms, experimental design, and performance analysis. Ling Tang and Long Long were responsible for implementing the framework, conducting simulations, and data collection. Xiao Qin provided critical revisions, theoretical insights, and guidance to improve the quality of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, X., Mi, J., Tang, L. et al. Dynamic multi objective task scheduling in cloud computing using reinforcement learning for energy and cost optimization. Sci Rep 15, 45387 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29280-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29280-z