Abstract

The mechanical torsion drive mode used in existing looms results in high energy consumption and low efficiency during the weft insertion process due to mechanical impact, making it unsuitable for the weaving requirements of high-speed and ultra-wide fabrics. Based on the “zero loss” concept of magnetic suspension, this article proposes a magnetic suspension non-contact coupling method for weft insertion. It introduces a new magnetic suspension gripper configuration and clamping drive device, increasing the weft insertion speed to 40.0 m/s and reducing energy consumption to 7.2% of that of mechanical drives. The article explains the fundamental working principle of magnetic suspension weft insertion, establishes a dynamic model of projectile weft insertion, and conducts a systematic magneto-mechanical analysis. To enhance weft insertion performance and mitigate adverse effects caused by hysteresis nonlinearity and external interference, a lag-lead correction control strategy is proposed. Using control performance indices as objectives, a Bode diagram is drawn within the parameter design space to optimize performance. Tests demonstrate that the lag-lead correction method increases the system phase margin to 81.2°, shortens the dynamic response time of the magnetic suspension gripper weft insertion to 0.001 s, and maintains weft insertion trajectory accuracy within ± 0.1 mm, effectively suppressing trajectory deviations caused by hysteresis nonlinearity. The research results have established a comprehensive theoretical framework and engineering implementation plan, providing an innovative technical pathway for the automation upgrade of textile machinery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional gripper looms remain the most widely used machinery in the textile industry for weaving fabrics. Weaving machines are classified into four groups based on their weft insertion systems: gripper, projectile, rapier, and jet (i.e., air and water jet) looms. Among these, the gripper and projectile weft insertion systems have reached their performance limits due to low weaving speeds. The maximum projected mechanical efficiency for gripper looms is only about 13%, and the projectile speed has also reached its limit. Therefore, a new high-speed, high-efficiency direct-drive weft insertion principle must be developed to enhance the overall performance of the loom.

The electromagnetic weft insertion on looms was first proposed in the 1970 s, utilizing a basic two-stage energizing solenoid to drive the weft feeder and achieve weft insertion. Luo et al.¹ proposed a loom design that drives the gripper using the electromagnetic force generated by an electromagnetic coil. These methods introduced electromagnetic driving mechanisms into gripper weft insertion, which can improve weaving efficiency; however, the designs were relatively preliminary, and no detailed mechanism design or control strategies were presented.

Existing research on magnetic suspension theory and technology primarily focuses on magnetic suspension trains, bearings, power equipment, and high-speed precision devices. Farhan Ashad, Johnson Martin, Hanson Kyle designed an ultra-high speed bearingless motor for significant rated power2.Yoo, Seong JongKim et al. proposed a data-driven self-sensing technique for active magnetic bearing3. Can Wang et al. gave the application of model predictive control for magnetic suspension4. Zhang Zhengqiang and Ma Zhenwei dealt with the complex position tracking control problem of magnetic levitation system with parameter uncertainty and external disturbance5. Hu and Wu derived the electromagnetic coil current curve formula for hybrid magnetic suspension systems, which holds significant theoretical value for studying the mechanism of direct-driving weft insertion6.

This paper studies a new driving mechanism of magnetic suspension frictionless weft insertion, traditional magnetic suspension gripper adopts a torsion shaft to convert mechanical energy into kinetic energy, with a weft insertion rate of only approximately 23.3 m/s. A novel magnetic suspension gripper and weft insertion system designed by our research group, with the weft insertion rate of the gripper can reach nearly 43.35 m/s, significantly enhancing weft insertion efficiency and demonstrating strong practical implications7.

The structure of the paper is as follows: the concept of frictionless gripper weft insertion, utilizing a new driving method, is employed to quantify the magnetic suspension force and achieve stable weft insertion. Building on this foundation, the motion of the gripper and its control characteristic equation are derived.

Methods

Principle of magnetic suspension

Magnetic suspension is a non-contact technology that reduces maintenance costs and is energy efficient due to the absence of friction. This technology represents the future of transportation, non-contact actuators, precision engineering. However, open-loop magnetic suspension systems are highly nonlinear and unstable, making the design of a simple and effective controller for such systems very challenging.

When a superconductor is placed in a magnetic field generated by a superconducting coil, an induced current appears on the surface of the superconductor according to Faraday’s law of induction. Based on electromagnetic theory, the magnetic field produced by this induced current opposes the applied magnetic field, resulting in a force between the superconductor and the coil8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19.

New magnetic suspension gripper

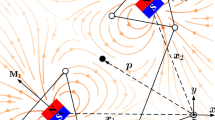

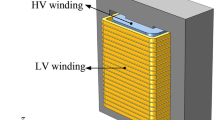

The design of the magnetic suspension gripper is illustrated in Fig. 1. The new magnetic suspension gripper system comprises the gripper body, permanent magnet modules for coupled weft insertion secondary propulsion, a gripper clip, thin-film sensors, and control chips, as shown in Fig. 1(a). The magnetic levitation gripper is mounted on a permanent magnet track and driven by a three-phase excitation winding, which propels the weft along the magnetic levitation track, as depicted in Fig. 1(b).

The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 2, it is operated in an environment maintained at 25℃ ± 2℃. The gap between the projectile shuttle and the weft insertion track is controlled within 2.5 to 5.0 mm. The system runs continuously for 8 h, with a temperature increase of no more than 45 K.

The test platform guide rail consists of hollow electromagnetic coil windings. A permanent magnet is attached to the lower surface of the suspended gripper. The gripper is ejected from the external coil into the weaving track. At this point, the electromagnetic device generates an electromagnetic force to control the weft insertion gap and couples the gripper for high-speed weft insertion.

The traditional mechanical torsion gripper driving device is roughly manufactured and lacks any control mechanism. The torsion gripper uses elastic potential energy to drive the gripper, which holds the weft yarn for insertion, and is decelerated by the shuttle box at the end. After completing one pick, the gripper returns from the outside to its initial position for the next weft insertion, and this process repeats. The weft insertion speed is 20–25 m/s, the weft insertion width is only 5.4 m, and the weft insertion efficiency is low, as shown in Fig. 3(a).

A magnetic suspension gripper for double-direction weft insertion is proposed in this paper. The gripper clamping device is shown in Fig. 3(b), it is fixed at the end of the weft guide rail. Cylinder 1 is connected to the driving motor. The controller operates the motor, causing push rod 2 to move toward cylinder 1, which in turn drives connecting plate 4 to move. The two connecting plates 4 form a clamp that secures the weft guide in place. The startup and positioning adjustments of the clamping device are managed entirely by the control system, which simultaneously initiates the reverse drive.

When the yarn is fed to the gripper, the gripper enters the weft insertion track and moves through it at high speed. The electromagnetic force between the electromagnetic coil array and the permanent magnet gripper maintains the gripper’s balance, enabling frictionless weft insertion. Upon reaching the braking area, the gripper decelerates to complete the braking process, and the weft is cut, thus completing the electromagnetically driven suspension weft insertion process, as shown in Fig. 3(c).

Compared to the traditional mechanical torsion gripper system, the new clamping device features a simpler structure. after detecting the gripper, it performs braking and reverse driving, with the entire process being automatically controlled.

At the same time, the energy consumption of traditional torsional drives during single weft insertion is 0.024 W, while the energy consumption of the magnetic suspension gripper under single drive conditions is 5.88 × 10−8W/mm², with the total energy consumption of the entire coil can be calculated as: 1.73 × 10−3W. Notably, there is no impact or wear, which significantly enhances driving efficiency and weft insertion speed7. The comparison of the heat loss in the torsion shaft and the electromagnetic coil during a single weft insertion is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Main characteristics

Figure 5 shows the control diagram of the magnetic suspension gripper system. The system primarily consists of position sensors, controllers, power amplifiers, and the magnetic suspension gripper. The position sensor can be used for real-time position detection. The proactively report frame rates is 0.5-250HZ adjustable (affected by the amount of data subscribed).

An experimental rig has been constructed, incorporating both active and passive magnetic suspension gripper sensor systems. To ensure smooth weft insertion and prevent wire pulling, the magnetic suspension gripper system is equipped with bluetooth model sensors and DSP processor embedded within the gripper body. These sensors are capable of detecting minute deviations in the gripper’s position and transmitting this data instantaneously to the control terminal. The control terminal, in turn, adjusts the electromagnetic force generated by the coils, thereby maintaining the gripper’s stability and preventing it from straying from the predetermined path. This real-time feedback mechanism ensures precise weft insertion, enhancing weaving accuracy and efficiency.

The magnetic suspension gripper model

The electromagnetic suspension system uses magnetic fields to transfer energy. In most cases, these magnetic fields are generated by electrical energy. As the distance between the electromagnetic coil and the permanent magnetic shuttle changes, the strength of the magnetic field also varies, causing the suspension system to become unstable. By applying appropriate feedback, the excitation current is adjusted, resulting in a corresponding change in the magnetic force. This converts the unstable equilibrium point into a stable one, ensuring high-speed, non-friction suspension gripper weft insertion.

Due to the complexity of the control algorithm used by the magnetic suspension system controller, the control theory must be simplified to continuously enhance its performance. In this paper, the relationship between electromagnetic force and clearance is analyzed based on the fundamental calculation formula of electromagnetic force. First, the permanent magnet force is calculated. When the permanent gripper operates alone and the offset distance reaches a certain degree, the permanent magnet force is computed20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Next, the electromagnetic circuit at the position of the suspension gripper is simulated to determine the current required to balance the permanent magnet force. Finally, a dynamic model was established to derive a mathematical representation of the system.

During weft insertion processing, the control of the magnetic suspension gripper is influenced by the electromagnetic repulsion force\(\:\:\varvec{F}(\varvec{i},\varvec{x})\) and its own gravitational force mg acting in the vertical direction along the track. The dynamic mechanical equation in the vertical direction can be expressed as:

By defining the vertical upward direction as positive, the air gap distance between the gripper and the coil array is set to be \(\:\varvec{x}\). The magnetic resistance of the magnetic circuit is primarily generated in the air gap formed between the coil and the gripper. The reluctance is given by:

Where, all the symbols and parameter units are consistent with the references to abbreviations and acronyms.

Since the system directly uses electromagnetic coils to form tracks without built-in iron cores, the core material is typically a high-permeability substance, with a relative permeability ranging from thousands to tens of thousands. In contrast, the relative permeability of air \(\:\mu\:\approx\:1\). As a result, the magnetic reluctance of the core is much smaller than that of the air gap and can often be neglected, especially in the presence of an air gap. Therefore, the first term on the right side of Eq. (2) can be ignored, allowing the equation to be simplified as follows:

Where, all the symbols and parameter units are consistent with the references to abbreviations and acronyms.

As the Kirchhoff’s law in the magnetic circuit:

Where, all the symbols and parameter units are consistent with the references to abbreviations and acronyms.

Ideally, assuming that the magnetic flux through each coil is the same, the total flux linkage in the coil is:

Where, all the symbols and parameter units are consistent with the references to abbreviations and acronyms.

According to Biot-Savart’s law, the magnetic induction generated at any point in space is proportional to the current intensity in the circuit. The area enclosed by the circuit is proportional to the magnetic flux \(\:\varvec{\psi\:}\) and \(\:\varvec{i}\):

Where, all the symbols and parameter units are consistent with the references to abbreviations and acronyms.

The electromagnetic coil instantaneous inductance is:

Where, all the symbols and parameter units are consistent with the references to abbreviations and acronyms.

The energy \(\:{W}_{m}(i,\:x)\) stored in the magnetic coil is:

Where, the units of the parameters are the same as those in the equation above.

Equation (8) represents the magnetic energy above the electromagnetic coil. The permanent magnet component of the gripper utilizes soft magnetic silicon steel instead of traditional neodymium iron boron material. It is designed as a sheet with a thickness of only 1 mm, significantly reducing eddy current losses. Additionally, the silicon steel exhibits minimal hysteresis effects and low hysteresis losses, making it well-suited for alternating magnetic fields. Therefore, eddy current losses and hysteresis effects in the permanent magnetic spindle are neglected in the calculations. The flux cross-sectional area of the entire air gap above the coil is transformed into the cross-sectional area of the permanent magnet gripper, and the repulsive force of the permanent magnet gripper is given by:

Where, all the symbols and parameter units are consistent with the references to abbreviations and acronyms. Where, \(\:K\) is set to be \(\:\:-\left({\mu\:}_{0}s{N}^{2}\right)/4\), the above equation can be simplified as:

From Eq. (10), it can be seen that the electromagnetic force \(\:\varvec{F}(\varvec{i},\:\varvec{x})\) and the air gap x between the permanent magnet gripper are inversely and nonlinearly proportional, which is also the source of instability in the magnetic suspension system.

After the electromagnetic coil is powered, it can be modeled as a series connection of a resistor \(\:\varvec{R}\) and an inductor \(\:\varvec{L}\). The quivalent circuit follows Kirchhoff’s voltage law:

Where, \(\:\varvec{U}\left(\varvec{t}\right)\:\)is magnetic equivalent circuit voltage, all the symbols and parameter units are consistent with the references to abbreviations and acronyms. When the gripper injects the weft horizontally during weft insertion, the vertical acceleration must be zero. Therefore, the upward electromagnetic force acting on the gripper is equal to its own weight,

that is:

where, \(\:F({i}_{0},{x}_{0})\) is the electromagnetic repulsion force at the equilibrium position, the air gap \(\:{x}_{0}\) is at equilibrium, and the balance current is \(\:{i}_{0}\).

As mentioned above, the equation arrays for the magnetic suspension gripper in the electromagnetic-mechanical system are established:

Due to the complex nonlinear relationship among the electromagnetic force \(\:\varvec{F}\) in the electromagnetic system, the instantaneous current \(\:\varvec{i}\), and the air gap \(\:\varvec{x}\), the system is expanded and linearized using a Taylor series around the equilibrium point \(\:({i}_{0},{x}_{0})\).

Where, all the parameter units are consistent with the above equations. This force balances the gravitational force on the gripper, so:

It is defined as follows:

The complete descriptive Eq. (14) can be represented:

Where, all the symbols and parameter units are consistent with the references to abbreviations and acronyms.

From Eq. (15), by applying the Laplace transform, the system function under the current control mode is obtained:

Where, x(s) is the Laplace transform of x, and i(s) is the Laplace transform of i. The above transfer function corresponds to the suspension gripper, the position of the suspension gripper is detected by the control sensor at any time to generate a proportional excitation control current. The system input is defined as the current \(\:{U}_{in}\), and the system output is the voltage \(\:{U}_{out}\), which is reflected by x. Simultaneous Eqs. (12) and (16) yield the output Eq.

In this paper, the model described above is validated by comparing it with experimental measurements, and the experimental parameters meet the actual requirements. The parameters of the actual magnetic suspension system are listed in Table 1.

The transfer function of the system was calculated using MATLAB.

The system parameters depend on specific characteristics. In practice, the design of the electromagnetic coils is optimized by evaluating the specified technical requirements and adjusting the system accordingly.

The system interference is always an irregular pulse signal. The Bode diagram of the original magnetic suspension gripper system is shown in Fig. 6. It can be seen that the phase margin is 0 degrees at a cutoff frequency of approximately 32.3 rad/s, indicating that the system is unstable, as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7 shows that, in the time domain, the system is divergent and cannot return to its original trajectory when subjected to irregular pulse signal interference, the magnetic suspension gripper system is unstable. To achieve stable state, the current in the electromagnetic coil must be compensated and controlled to counteract changes in the suspension gripper’s air gap through system feedback and adjustment.

Simulation and results

The typical speed of existing mechanical grippers ranges from 20 to 25 m/s, and the weft insertion width is only 5.4 m, and the weft insertion efficiency is low. To achieve the integration of three key challenges in high-end magnetic levitation loom equipment under multi-field coupling—such as electromagnetic fields, thermal fields, load disturbances, and graft displacement—at high speeds (weft insertion rates of 40 m/s or higher), rapid response (adjustment time under 0.001 s), and precise steady-state control (overshoot less than 10%, reciprocating weft trajectory accuracy within 1%) over an ultra-wide range (greater than 20 m),

It is essential to optimize the design based on complex coupled fields and establish a unified timing comprehensive field for analysis. Therefore, the weft guide conditions for the given system require that dynamic overshoot remain below 10%, and the stable response time of the high-speed operating clamp be limited to 0.001 seconds28,29,30,31,32.

System revision

Based on the given conditions: (1) dynamic overshoot ≤ 10% and (2) response time limited to 0.001 s—the system should be adjusted according to the relationship between overshoot and phase margin:

where: \(\:{M}_{r}\): resonance peak, \(\:{t}_{s}\): system response time, \(\:\gamma\:\): phase margin, \(\:{\omega\:}_{cutoff}\): cutoff frequency of compensated system. From the above, the phase margin should be achieved \(\:{\upgamma\:}\ge\:65.4^\circ\:\), and the cutoff frequency should be 3416.5 rad/s. RC network can be implemented to achieve system revision in practical applications, with a cutoff frequency \(\:{\omega\:}_{cutoff}\) of 3416.5 rad/s.

Based on performance metrics such as system steady-state accuracy, phase margin, and response time, the revision method is as follows:

-

(1)

Bode diagram of the original system is plotted, and the phase margin is calculated.

-

(2)

The expected amplitude-frequency characteristics are determined according to the specified requirements.

-

(3)

The revision transfer function is calculated by subtracting the initial amplitude-frequency characteristic curve from the desired amplitude-frequency characteristic curve.

-

(4)

The system has been verified to meet performance requirements following the revision.

The specific numerical calculation steps are as follows:

-

(1)

The revision method is determined based on the initial system amplitude-frequency response shown in Fig. 4, where:

The initial system cutoff frequency is \(\:{\omega\:}_{cutoff0}=32.3rad/s\).

The initial system phase margin is \(\:{\gamma\:}_{0}=0degree\).

The initial system does not meet the stability requirements.

-

(2)

The lag-lead method is determined by the system and the expected revision frequency \(\:{\omega\:}_{cutoff}=3416.5rad/s\).

-

(3)

The revision transfer function \(\:{G}_{c}\left(s\right)\) is determined as follows:

Based on the given conditions: \(\:\gamma\:\ge\:65.4^\circ\:\), phase angle of the revision system is calculated as:

attenuation factor \(\:a=(1+sin({\phi\:}_{m}\left)\right)/(1-sin({\phi\:}_{m}\left)\right)=35.71\:\Rightarrow\:\:\sqrt{a}=5.98\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:10lg\left(a\right)\:=\:15.53\).

On the bode diagram: A, B points are designed at expected cutoff frequency position (ωcutoff = 3416.5), as shown in Fig. 8.

\(\:\sqrt{\text{a}}\) multiplier was pulled at point B to determine the coordinates of points C and D in the amplitude-frequency diagram.

where, frequency at point C: \(\:{{\upomega\:}}_{\text{c}}=\sqrt{\text{a}}\cdot\:{{\upomega\:}}_{\text{c}\text{u}\text{t}\text{o}\text{f}\text{f}}=1.79\times\:{10}^{4}\text{r}\text{a}\text{d}/\text{s}\), frequency at point D: \(\:{{\upomega\:}}_{\text{D}}={{\upomega\:}}_{\text{c}\text{u}\text{t}\text{o}\text{f}\text{f}}/\sqrt{\text{a}}=502\text{r}\text{a}\text{d}/\text{s}\).

The frequencies at points E and F on the Bode diagram are defined relative to the frequency at point C. Since the frequencies at positions E and F correspond to the lag compensation section, they can be significantly different from the system frequency at the time of selection. The frequency at position E can be taken as \(\:{\omega\:}_{E}=0.001\cdot\:{\omega\:}_{cutoff}\approx\:3.6rad/s\). The frequency at position F is calculated as follows: \(\:{{\upomega\:}}_{\text{t}\text{e}\text{m}\text{p}}=({{\upomega\:}}_{\text{c}\text{u}\text{t}\text{o}\text{f}\text{f}0}\times\:{{\upomega\:}}_{\text{c}\text{u}\text{t}\text{o}\text{f}\text{f}0})/{{\upomega\:}}_{\text{c}\text{u}\text{t}\text{o}\text{f}\text{f}}\approx\:2.67\text{r}\text{a}\text{d}/\text{s}\Rightarrow\:{{\upomega\:}}_{\text{F}}=({{\upomega\:}}_{\text{D}}\times\:{{\upomega\:}}_{\text{E}})/{{\upomega\:}}_{\text{t}\text{e}\text{m}\text{p}}\approx\:564.8\text{r}\text{a}\text{d}/\text{s}\).The transfer function of the compensator is determined as:

Finally, an open-loop gain is added to reduce the steady-state error of the system. Through actual testing, the open-loop gain is determined to be \(\:K\) = 4.5.

Result of system revision

Once the revision network and parameters are determined, the open-loop transfer function after revision is shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 10 shows the Bode diagram of the system with the lag-lead modification. The cutoff frequency \(\:{\omega\:}_{cutoff}\), reaches nearly 3410 rad/s, satisfying the specified requirements. The phase margin is 81.2°, indicating that the system is stable. As illustrated in Fig. 11, and based on the lag-lead modification, the system can be transitioned from an unstable to a stable state by selecting appropriate attenuation coefficients and time parameters. Furthermore, in the stable state, the response time is reduced to approximately 0.001 s. This allows the magnetic suspension gripper to quickly return to its equilibrium position after external disturbances, with the steady-state error maintained within a 10% range.

At this stage, the surface pressure of the sheet shuttle and the characteristics of the surrounding flow field during high-speed weft guidance of the magneto-floating sheet shuttle are further analyzed. The surface pressure on the shuttle and the characteristics of the surrounding flow field are illustrated by the average flow shown in Fig. 12. Due to the blocking effect of the shuttle head on the incoming airflow, the airflow velocity in front of the shuttle head decreases, causing an increase in pressure. A strong high-pressure zone forms at the tip of the shuttle head and radiates outward. Beyond a certain distance, the positive pressure influenced by this high-pressure zone dissipates and approaches zero, as depicted in Fig. 12.

The surface pressure and temperature distribution of the gripper during weft insertion are shown in Fig. 13.

As shown in Fig. 13 (a), during the horizontal weft insertion with velocity at approximately 40.0 m/s, the maximum total pressure experienced is 103,825.40 Pascals, which is nearly equivalent to one atmosphere of pressure. This pressure is primarily concentrated at the tip of the shuttle’s head, the pressure in this region is higher than in other areas of the gripper. Aside from the high-pressure zone at the nose tip, the pressure distribution across the rest of the gripper is relatively uniform, which helps ensure the stability and accuracy of the gripper during the weft insertion process. The surface temperature of the magnetic suspension gripper is 294 K, with a uniform temperature distribution and no localized overheating, as shown in Fig. 13(b). This indicates that the magnetic suspension system maintains good thermal stability during high-speed operation, further confirming its stability and reliability under such conditions.

Figure 14(a) shows the weft insertion trajectory of the magnetic suspension gripper over 10 times. The trajectory error is maintained within ± 0.1 mm, demonstrating good repeatability and stability, and meeting the requirements for high-precision positioning.The comparison of weft insertion velocity between the new magnetic suspension gripper and the traditional torsion gripper is shown in Fig. 14(b).

As shown in Fig. 14(a), the accuracy of the weft insertion track reaches ± 0.1 mm, and the response time is within 0.001 s, shown in Fig. 11. The weft insertion speed of the magnetic suspension gripper reaches 40.0 m/s or higher in Fig. 14(b). Additionally, the stability and accuracy of the magnetic suspension shuttle during high-speed operation are significantly superior to those of the traditional torsion shaft gripper. The speed curve is smoother, allowing for more precise control of the insertion position and speed of the weft yarn, which reduces fabric defects and enhances product quality.

Conclusion

The magnetic suspension gripper is an innovative weaving mechanism that utilizes the non-contact feature of magnetic levitation to achieve efficient and rapid weft insertion. This paper presents a new model of a magnetic suspension weft insertion gripper, explains the fundamental working principle of the suspension gripper, and preliminarily establishes a dynamic model for the magnetic suspension system. The dynamic model of the magnetic suspension gripper is further refined through compensation using a correction network. Based on the lag-lead correction, by selecting appropriate attenuation coefficients and time parameters, the system can be stabilized from an unstable state. The magnetic levitation projectile shuttle achieves a weft insertion accuracy of ± 0.1 mm and an extremely short response time of approximately 0.001 s, providing a strong guarantee for high-speed weaving.

Future research will further investigate the horizontal components of the electromagnetic driving forces and their interactions with factors such as air resistance and orbital friction. Additionally, the coupling effects between the horizontal and vertical directions, especially under high-speed motion conditions, may induce complex dynamic responses, thereby affecting the stability and performance of the entire system. We will address these theoretical gaps by developing more comprehensive mathematical models and conducting in-depth numerical simulations to clarify the dynamic characteristics of the magnetically suspended projectile shuttle in both horizontal and vertical directions. This will improve weft insertion accuracy and efficiency, thereby advancing textile machinery technology.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- m :

-

Mass(kg)

- g :

-

Acceleration due to gravity(m/s2)

- x:

-

air gap length (m).

- \(\:F(i,\:x)\) :

-

Electromagnetic repulsion force acting on the gripper(N)

- \(\:R\left(x\right)\) :

-

Magnetic resistance of equivalent magnetic circuit(H-1).

- \(\:{l}_{length}\) :

-

Magnetic core length (meter)

- s :

-

Cross-section area of the coil and suspension gripper (m2)

- i :

-

Current in the solenoid (Ampere)

- N :

-

Electromagnetic coil turns

- ϕ :

-

Magnetic flux (wb)

- \(\:\psi\:(i,x)\) :

-

Chain number of magnetic flux (wb·n)

- L :

-

Electromagnetic coil inductance(H)

- \(\:{W}_{m}(i,x)\) :

-

Storage energy in system (Joule)

- \(\:\varvec{U}\left(\varvec{t}\right)\:\) :

-

Magnetic circuit equivalent voltage(Voltage)

References

Shengmei, L., Bo, Z., Le, T. & Zhihong, M. Study of a electromagnetic weft insertion in textile machine. Adv. Mater. Reserach. 70 (11), 498–501 (2012). https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.591-593.498

Farhan Ashad, J., Martin, H. & Kyle Design of an ultra-high speed bearingless motor for significant rated power. IEEE Energy Conversion Congrress and Exposition 2020:246–253 https://doi.org/10.1109/ECCE44975.2020.9236181 (2020).

Yoo, S. et al. Data-driven self-sensing technique for active magnetic bearing. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 22 (6), 1031–1038. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12541-021-00525-x (2021).

Can Wang, M. et al. Vibration suppression with shaft torque limitation using explicit MPC-PI switching control in elastic drive systems. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 62 (11), 6855–6867. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2015.2438055 (2015).

Zhang, ZhengqiangMa, Z. Adaptive control of a voltage-controlled magnetic levitation system with K-filter. Proceedings of The 15th IEEE Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA 2020). :1276–1281. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIEA48937.2020.9248284 (2020).

Yefa, H. & Huachun Wu. &. Flow Field Numerical Simulation and Hemolytic Prediction for Axial Flow Maglev Blood Pump. China Mechanical Engineering, 24 (3), 399–403 https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-132X.2013.03.024. (2013).

Li Zhu, JiaqingWang, X. W. Chi Zhang. Structure and performance analysis of magnetic suspension gripper driving system. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12632-0 (2025).

Yang, Z. J., Kunitoshi, K. & Kanae, S. Adaptive robust output-feedback control of a magnetic levitation system by K-filter approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 55 (1), 390–399. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISIC.2004.1387707 (2018).

Lin, F. J., Chen, S. Y. & Shyu, K. K. Robust dynamic sliding-mode control using adaptive RENN for magnetic levitation system. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks. 20 (6), 938–951. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNN.2009.2014228 (2019).

Gutierrez, H. M. & Ro, P. I. Magnetic servo levitation by sliding-mode control of nonaffine systems with algebraic input invertibility. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 52 (5), 1449–1455. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2005.855651 (2015).

Shieh, H. J., Siao, J. H. & Liu, Y. C. A robust optimal sliding mode control approach for magnetic levitation systems. Asian J. Control. 12 (4), 480–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/asjc.210 (2015).

Ataslar-Ayyildiz BanuKarahan, OguzhanYilmaz, Serhat. Control and robust stabilization at unstable equilibrium by fractional controller for magnetic levitation systems. Fractal Fract. 5 (3), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract5030101 (2021).

Lin, F., Teng, L. & Shieh, P. Intelligent adaptive back stepping control system for magnetic levitation apparatus. IEEE Trans. Magn. 43 (5), 2009–2018. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2006.890325 (2017).

Wang Dini, M., Fanwei, M. & Shengya Linearization method of nonlinear magnetic levitation system. Math. Probl. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/9873651 (2020). 2020:9873651.

Peterson, K. S., Grizzle, J. W. & Stefanopoulou, A. G. Nonlinear control for magnetic levitation of automotive engine Vales. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 14 (2), 346–354. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCST.2005.863669 (2016).

Almobaied Moayed, Al-Nahhal Hassan, S. et al. Design a robust Proportional-Derivative Gain-Scheduling control for a magnetic levitation system. Mathematics 11 (19), 4040. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11194040 (2023).

Wang, Y. & Marshall, R. A. &S Cheng.Physics of electric launch. Beijing: China, 136–200. ISBN: 7-03-012821-4. (2018).

Ram, RanashreeThomas, M. & Joy Experimental and computational studies on the efficiency of an induction coilgun. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 48 (10), 3392–3400. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2020.3007551 (2020).

19 et al. Design and evaluation of the driving coil on induction coilgun. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 43 (5), 1203–1207. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2015.2404925 (2015).

20, Du, Z., Zhan, T., Ruan, J. & Weimin, G. Research on electromagnetic performance affected by shielding enclosure of a coil launcher. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 51 (5), 1077–1083. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2013.2246840 (2023).

Liu, J. R. S. & &Zhang, Y. Application of fe-becm in field analysis of induction coil gun. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 49 (1), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2010.2051164 (2021).

Guan Shaohua, Guan, Xiaocun, W. & Baoqi Analysis of the influence of system parameters on launch performance of electromagnetic induction coil launcher. Energies 15 (20), 7803. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15207803 (2022).

Yousefi, A. A. M. R.Moghadam. Uniaxially aligned microwire networks for flexible transparent electrodes using a novel electrospinning set-up. Sol. Energy. 188, 1111–1117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.07.007 (2019).

Batka Ondrej, S., Josef & Beran Jaroslav. Optimizing the shape of the spinning electrode for needleless coaxial electrospinning. Appl. Sciences-Basel. 14 (11), 4638. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14114638.( (2024).

Lai, H. J. & PengyangWang, Z. Study on type of magnetic suspension rotor groove and wear of drop touchdown bearing. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 18 (1) https://doi.org/10.1080/19942060.2024.2422065 (2024).

Wan, L. C. & GuofangSheng Mingwei. Adaptive chattering-free terminal sliding-mode control for full-order nonlinear system with unknown disturbances and model uncertainties. Int. Adv. Robotic Syst. 17 (3), 172988142092529. https://doi.org/10.1177/1729881420925295 (2020).

Zhang, D. Q. & HaiyanSun, Y. Model-Independent robust control for electromagnetic suspension systems of Maglev vehicles. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 34 (8). https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2024.3420213 (2024).

Mykhailyshyn, R. S. & VolodymyrFey, A. Gripping device for textile materials. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 20 (4), 2397–2408. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASE.2022.3208796 (2023).

Sun YougangHe, Z. & Xu, J. Dynamic analysis and vibration control for a Maglev vehicle-guideway coupling system with experimental verification. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 188, 109954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2022.109954 (2023).

Zhang, G. B. J., QianjunDong, D. & Wei A compact electromagnetic dual actuation positioning system with a 10 mm range and nanometer resolution. Actuators 12 (3), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/act12030132 (2023).

Xiang Huoyue, T., Xiangfu, L., Yongle, Z. & Min Dynamic interaction analysis of high-speed Maglev train and guideway with a control loop failure. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 22 (10), 2241012. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219455422410127 (2022).

Bellahcene, Z., Mohamed, B. & Mouloud, D. Assali Khaled. Adaptive neural network-based robust H∞ tracking control of a quadrotor UAV under wind disturbances. International Journal of Automation and Control 15 (1), 28–57 https://doi.org/10.1504/IJAAC.2021.111747 (2020).

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to all the reviewers’ comments for the manuscript. We believe all the constructive and positive comments from the referees and your side will help improve the quality of the manuscript. Thanks for your careful work and kind help!

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Li Zhu. Associate Professor, School of Mechanical Engineering and Automation, Wuhan Textile University, mainly engaged in intelligent manufacturing. In this paper, construction of the magnetic suspension gripper was designed by him, the calculation and simulation of the magnetic suspension gripper was calculated and simulated, as well as the design of the revision system.Xiaoguang Wu. Professor, School of Mechanical Engineering and Automation, Wuhan Textile University. In this paper, the basic concept of the magnetic suspension gripper was proposed by him, and the ideas and methods for this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, L., Wu, X. Study on working mechanism and control method of new magnetic suspension gripper. Sci Rep 15, 45019 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29293-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29293-8