Abstract

To assess the impact of synkinesis on voice restoration in idiopathic vocal fold paralysis (IVFP) patients with different disease courses, a cohort of 130 IVFP patients (comprising 71 males and 59 females; 78 cases with left-sided paralysis and 52 cases with right-sided paralysis) was categorized into two groups according to their disease courses (group 1: < 3 months, group 2: 3–6 months). Each group was subsequently subdivided based on the presence or absence of synkinesis according to the laryngeal electromyography (LEMG) results, as evaluated by two physicians who are board‐certified in electrodiagnostic medicine. The specific information of the IVFP patients were blinded to both the two evaluators, and the LEMG results evaluated by them were also blinded to each other. Then the analysis revealed that the individuals in the group 2 (45 cases) demonstrated significantly greater maximum phonation time (MPT) and maximum sound pressure level (SPLmax) compared to those in the group 1 (85 cases) (MPT, 8.34 ± 7.35 s vs 5.55 ± 4.29 s, t = − 2.008, P = 0.049; SPLmax, 94.53 ± 14.72 dB vs 87.88 ± 9.82 dB, t = − 2.101, P = 0.040). Furthermore, the group 2 exhibited a higher prevalence of synkinesis than that in the group 1 (35.56% vs 14.12%, P = 0.005). Notably, within the group 2, the patients with synkinesis had significantly lower MPT values (4.10 ± 1.79 s vs 8.20 ± 5.84 s, t = − 2.569, P = 0.019), as well as higher amplitudes of paralytic recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) compared to those without synkinesis (7.71 ± 8.35 mV vs 1.70 ± 1.31 mV, t = − 2.493, P = 0.023). Conversely, in the group 1, no significant differences were observed in the comparison of MPT values or amplitudes of RLN between the individuals with synkinesis and those without synkinesis (MPT, 6.01 ± 5.83 s vs 5.46 ± 4.01 s, t = − 0.334, P = 0.740; the amplitudes of RLN, 2.62 ± 2.35 mV vs 2.74 ± 3.14 mV, t = 0.104, P = 0.917), which were analyzed by Bonferroni (a multiple-comparison correction method, m = 2, ɑ = 0.025), and the P value less than 0.025 represents a significant difference in such condition. These findings suggest that synkinesis adversely affects voice restoration in the IVFP patients with a disease course of 3–6 months, indicating that the IVFP patients should accept diagnosis and treatment within 3 months after onset to improve their voice qualities, avoiding the adverse effects caused by synkinesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the absence of traumatic, malignant, iatrogenic, or other identifiable causes of vagus or recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury, a diagnosis of idiopathic vocal fold paralysis (IVFP) is assigned to the patients exhibiting clinical and symptomatic evidence of vocal fold paralysis1. IVFP is characterized by a distinct clinical presentation, involving relatively minor denervation changes in the affected laryngeal muscles and exerting a lesser impact on the quality of life compared to iatrogenic vocal fold paralysis2. Yan et al. demonstrated short-term improvements in the phonation among the IVFP patients following RLN stimulation. However, the variations in vocal parameters among the IVFP patients with different disease courses have not been thoroughly investigated3.

Stanisz et al. proposed that in the unilateral vocal fold paralysis (UVFP) patients within 1–3 months of onset, RLN experiences a significant denervation, with nerve regeneration typically reaching the laryngeal muscles by approximately a 3-month mark4. Furthermore, they observed that the regenerative potential becomes apparent in the UVFP patients with a disease course of more than 3 months, often accompanied by synkinesis4. Synkinesis refers to the misdirected and aberrant reinnervation that occurs during the repair process of RLN injury, resulting in abnormal muscle movements. This condition is characterized by the random distribution of regenerated nerve fibers to antagonistic vocal fold muscles, which may compromise the recovery of intrinsic laryngeal muscle function5. The patients with synkinesis often exhibit near-complete restoration of turn frequency in thyroarytenoid muscle (TA) and lateral cricoarytenoid (LCA) muscle but continue to experience voice impairment, a phenomenon consistent with the mechanism of aberrant reinnervation6. Although stroboscopic laryngoscopy, voice analysis, and laryngeal electromyography (LEMG) could be used to detect abnormalities in the IVFP patients, the role of synkinesis in the IVFP patients with different disease courses remains unclear. Consequently, this study aims to investigate the impact of synkinesis on voice restoration in the IVFP patients with different disease courses, as determined by the LEMG results.

Results

Comparative analysis of the voice parameters in the IVFP patients with different disease courses

Initially, a cohort of 130 IVFP patients was analyzed, consisting of 71 males and 59 females, in which 78 cases were left-sided paralysis and 52 cases were right-sided paralysis. The distribution of age, gender ratios (male to female), and laterality ratios (left side to right side) were found to be comparable between the group 1 (85 cases with a disease course of less than 3 months) and the group 2 (45 cases with a disease course of 3 to 6 months). This indicates that the demographic characteristics of the IVFP patients were consistent across different disease courses. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that among the various indicators assessed, only the maximum phonation time (MPT) values and the maximum sound pressure level (SPLmax) values were significantly higher in the group 2 compared to those in the group 1 (MPT: 8.34 ± 7.35 s vs 5.55 ± 4.29 s, t = − 2.008, P = 0.049, Cohen´s d = − 0.522; SPLmax: 94.53 ± 14.72 dB vs 87.88 ± 9.82 dB, t = − 2.101, P = 0.040, Cohen´s d = − 0.591). Conversely, the voice handicap index (VHI) score was lower in the group 2 (47.88 ± 29.04) than that in the group 1 (51.71 ± 28.72), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (t = 0.461, P = 0.646, Cohen´s d = 0.133). Additionally, no significant differences were observed between the two groups in other indicators such as dysphonia severity index (DSI) (0.19 ± 3.10 vs − 2.95 ± 7.49, t = − 1.673, P = 0.099, Cohen´s d = − 0.457), the highest fundamental frequency (F0max) (370.20 ± 124.18 Hz vs 331.71 ± 135.82 Hz, t = − 0.979, P = 0.332, Cohen´s d = − 0.289), the lowest fundamental frequency (F0min) (126.29 ± 34.72 Hz vs 118.54 ± 47.50 Hz, t = − 0.618, P = 0.539, Cohen´s d = − 0.174), and the minimum sound pressure level (SPLmin) (54.00 ± 4.12 dB vs 56.21 ± 5.80 dB, t = 1.442, P = 0.154, Cohen´s d = 0.408) (Table 1).

Comparative analysis of the LEMG results in the IVFP patients with different disease courses

Regarding the LEMG results, the amplitudes of the paralytic RLN and the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle (PCA) or TA in the group 1 did not significantly differ from those in the group 2 (RLN: 2.72 ± 3.00 mV vs 3.92 ± 5.76 mV, t = − 0.860, P = 0.399, Cohen´s d = − 0.302; PCA: 0.47 ± 0.28 mV vs 0.37 ± 0.13 mV, t = 1.523, P = 0.133, Cohen´s d = 0.412; TA: 0.42 ± 0.25 mV vs 0.34 ± 0.11 mV, t = 1.716, P = 0.091, Cohen´s d = 0.339). Similarly, comparisons in the latencies of RLN and in the action potential durations (APDs) of TA between the group 1 and the group 2 revealed no significant differences (the latencies of RLN: 1.77 ± 0.98 ms vs 2.30 ± 1.69 ms, t = − 1.285, P = 0.212, Cohen´s d = − 0.436; the APDs of TA: 9.56 ± 2.64 ms vs 8.24 ± 3.85 ms, t = 1.376, P = 0.181, Cohen´s d = 0.438) (Table 2). Furthermore, the latencies and amplitudes of the superior laryngeal nerve (SLN), as well as the APDs and amplitudes of the cricothyroid muscle (CT) in the group 2, were comparable to those in the group 1 (the latencies of SLN: 2.04 ± 1.24 ms vs 2.01 ± 1.13 ms, t = 0.085, P = 0.932, Cohen´s d = 0.022; the amplitudes of SLN: 8.27 ± 7.29 mV 6.90 ± 5.14 mV, t = 0.779, P = 0.439, Cohen´s d = 0.204; the APDs of CT: 10.71 ± 3.10 ms 9.23 ± 4.03 ms, t = 1.502, P = 0.143, Cohen´s d = 0.435; the amplitudes of CT: 0.52 ± 0.21 mV 0.49 ± 0.28 mV, t = 0.514, P = 0.609, Cohen´s d = 0.137) (Table 2). However, the APDs of PCA in the group 2 were significantly shorter than those in the group 1 (8.24 ± 3.05 ms vs 10.29 ± 2.77 ms, t = 2.667, P = 0.010, Cohen´s d = 0.721) (Table 2). These findings indicate that the disease course has a minimal impact on the LEMG results, influencing not only on the RLN and SLN, but also on the associated innervated muscles, with the exception of the APDs about PCA.

The influence of synkinesis on the voice restoration in the IVFP patients with different disease courses

Initially, there was a high level of concordance between the evaluations of synkinesis status made by two independent otolaryngologists (Cohens kappa = 0.84, P < 0.01), thereby ensuring the inter-rater reliability for subsequent analyses. Furthermore, the IVFP patients exhibited varying degrees and proportions of synkinesis contingent upon their disease courses. Notably, the individuals in the group 2 displayed a significantly higher prevalence of synkinesis (16/45, 35.56%) than that in the group 1 (12/85, 14.12%) (χ2 = 8.002, P = 0.005), with a positive correlation observed between the disease course and the synkinesis status (R = 0.627, P < 0.001). Subsequently, the MPT and F0max values varied significantly among the IVFP patients with different disease courses and synkinesis statuses (MPT, F = 2.786, P = 0.047, partial eta square = 0.111; F0max, F = 6.758, P = 0.012, partial eta square = 0.097). However, no interaction effect was found between the disease course and the synkinesis status on the MPT or F0max (MPT, Finteraction = 0.778, Pinteraction = 0.381, partial eta square = 0.011; F0max, Finteraction = 1.741, Pinteraction = 0.195, partial eta square = 0.028). Additionally, within the group 2, individuals with synkinesis exhibited significantly lower MPT values compared to those without synkinesis (4.10 ± 1.79 s vs 8.20 ± 5.84 s, t = − 2.569, P = 0.019), but no significantly difference was observed in the group 1 (6.01 ± 5.83 s vs 5.46 ± 4.01 s, t = − 0.334, P = 0.740), analyzed by Bonferroni (a multiple-comparison correction method, m = 2, ɑ = 0.025), and the P value less than 0.025 represents a significant difference in such condition. However, within the group 2, the F0max values in the individuals with synkinesis (293.67 ± 87.71 Hz) were almost the same as those without synkinesis (421.22 ± 121.90 Hz) (t = 2.200, P = 0.047), and this situation also applies to the group 1 (344.13 ± 128.79 Hz vs 329.29 ± 138.55 Hz, t = − 0.280, P = 0.781). Moreover, no significant differences were identified in the other voice parameters, including the DSI (F = 1.370, P = 0.260, partial eta square = 0.062), the F0min (F = 0.800, P = 0.499, partial eta square = 0.037), the SPLmax (F = 1.878, P = 0.143, partial eta square = 0.083), the SPLmin (F = 0.783, P = 0.508, partial eta square = 0.038), and the VHI score (F = 0.472, P = 0.703, partial eta square = 0.023), across the individuals with different disease courses and synkinesis statuses (Table 3). These findings suggest that the impact of synkinesis on voice parameters is limited for the IVFP patients with a disease course of less than 3 months.

The influence of synkinesis on the LEMG results in the IVFP patients with different disease courses

Initially, the latencies and amplitudes of the paralytic RLN in IVFP patients varied significantly across different disease courses and synkinesis statuses (the latencies of RLN, F = 3.691, P = 0.016, partial eta square = 0.150; the amplitudes of RLN, F = 4.382, P = 0.007, partial eta square = 0.173). Notably, there were significant interaction effects on the latencies and amplitudes of RLN between the disease course and the synkinesis (the latencies of RLN, Finteraction = 8.184, Pinteraction = 0.006, partial eta square = 0.115; the amplitudes of RLN, Finteraction = 7.331, Pinteraction = 0.009, partial eta square = 0.104), rendering comparisons in the latencies and amplitudes of the paralytic SLN, as well as the APDs and amplitudes of the paralytic CT, TA, and PCA, inappropriate among the IVFP patients with different disease courses and synkinesis statuses (the latencies of SLN, F = 1.498, P = 0.223, partial eta square = 0.065; the amplitudes of SLN, F = 0.425, P = 0.736, partial eta square = 0.019; the APDs of CT, F = 1.594, P = 0.199, partial eta square = 0.068; the amplitudes of CT, F = 0.791, P = 0.503, partial eta square = 0.035; the APDs of TA, F = 2.429, P = 0.124, partial eta square = 0.124; the amplitudes of TA, F = 1.947, P = 0.131, partial eta square = 0.082; the APDs of PCA, F = 1.509, P = 0.224, partial eta square = 0.118; the amplitudes of PCA, F = 1.603, P = 0.197, partial eta square = 0.070). Furthermore, in the IVFP patients with a specific disease courses (< 3 months or 3–6 months), the latencies and amplitudes of the paralytic RLN in the individuals with synkinesis and those without synkinesis were compared. Specifically, the amplitudes of the paralytic RLN in the individuals with synkinesis (7.71 ± 8.35 mV) were significantly higher than those without synkinesis (1.70 ± 1.31 mV) in the group 2 (t = − 2.493, P = 0.023), but no significantly difference was observed in the group 1 (2.62 ± 2.35 mV vs 2.74 ± 3.14 mV, t = 0.104, P = 0.917), analyzed by Bonferroni (a multiple-comparison correction method, m = 2, ɑ = 0.025), and the P value less than 0.025 represents a significant difference in such condition (Table 4). In addition, in the group 2, the latencies of the paralytic RLN in the individuals with synkinesis (1.47 ± 0.28 ms) were almost the same as those without synkinesis (2.78 ± 1.99 ms) (t = − 2.245, P = 0.045), and this situation also applies to the group 1 (2.38 ± 1.23 ms vs 1.65 ± 0.89 ms, t = − 1.993, P = 0.052). This suggests that synkinesis may influence the amplitudes of the paralytic RLN in the IVFP patients with a disease course of more than 3 months.

Discussion

In the present study, it was observed that the IVFP patients with a disease course of 3–6 months did not experience a restoration of vocal fold movement. Nevertheless, these patients exhibited improved voice parameters, as demonstrated by significantly higher MPT and SPLmax values, which are indicative of sound vibration amplitude. These findings imply that recovery from vocal fold paralysis may lead to satisfactory vocal outcomes independent of the restoration of mobility in the affected vocal fold6. Furthermore, existing research indicates that although reinnervation alone may not fully restore the physiological motion of the vocal fold, it can enhance glottic competence during phonation by improving muscle bulk and tone7. Indeed, synkinesis is not invariably a counterproductive phenomenon. Frequently, synkinetic innervation can also ameliorate glottic insufficiency even in the absence of vocal mobility, by maintaining muscle tone and mass8. This results in the medialization of the paretic vocal fold and consequently explains the improved vocal outcomes observed in the IVFP patients with synkinesis9.

Laryngeal synkinesis is a complex and frequently misdiagnosed clinical condition. When there is a lack of correlation between symptoms and clinical examination, or when paradoxical vocal fold movement is observed, synkinesis should be considered. The diagnosis of synkinesis should be confirmed by LEMG, which typically reveals a recruitment pattern in TA that is more pronounced during deep inhalation than phonation. Munin defined synkinesis in LEMG as exhibiting greater recruitment during inhalation compared to continuous phonation in the paralytic TA, and the reverse pattern in the paralytic PCA10. This diagnostic criterion has been employed in our study. The phenomenon of synkinetic reinnervation has been well-documented in controlled animal studies11. Pitman et al. reported consistent reinnervation in a rat model 12 weeks following RLN injury12. Furthermore, Nagai demonstrated that, compared to an untreated group, the group treated with basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) exhibited a significant increase in muscle volume and vascular area in the lateral TA 3 months post-transplantation13. Moreover, leading theories regarding the etiologies of IVFP predominantly suggest a post-viral neuropathy, akin to that observed in Bell’s Palsy14.Accordingly, we sought evidence from studies on Bell’s Palsy as a reference. Kim posited that the patients experiencing sudden severe Bell’s Palsy should be administered oral steroids promptly and received physical therapy, including neuromuscular retraining therapy, within 3 months to minimize synkinesis prior to its onset15. This approach aligns with Jalali’s methodology for assessing primary outcomes (complete recovery) and secondary outcomes (synkinesis) in both short-term (less than 3 months) and intermediate/long-term (more than 3 months) periods post-randomization16. This rationale underpinned our decision to use a 3-month disease course as the threshold for studying synkinesis. However, the impact of synkinesis on voice parameters may differ among the IVFP patients with different disease courses. Notably, the individuals with a disease course of 3–6 months exhibited a significantly higher incidence of synkinesis. In this cohort, the patients with synkinesis demonstrated significantly lower MPT values compared to those without synkinesis, suggesting that synkinesis are largely ineffective or even detrimental to voice restoration for the IVFP patients with a disease course of 3–6 months17. This observation is consistent with the hypothesis that the presence of adductor synkinesis may adversely affect the prognosis for vocal fold motion recovery, categorizing it as poor18. Conversely, for the IVFP patients with a disease course of less than 3 months, no significant differences were observed in voice parameters, including MPT, DSI, F0max, F0min, SPLmax, SPLmin, and VHI, between the individuals with synkinesis and those without synkinesis. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that in the IVFP patients who have experienced the condition for less than 3 months, the incidence of synkinesis is significantly lower (14.12%) due to the relatively milder RLN injury during the early stages19. As a result, the differences in voice outcomes between the individuals with synkinesis and those without synkinesis are less pronounced. In cases of chronic RLN paralysis, the intrinsic laryngeal muscles may undergo varying degrees of atrophy, synkinesis, or a combination thereof. Persistent denervation and pathological reinnervation often occur simultaneously, exacerbating each other to varying degrees20. Consequently, the advantages of voice restoration, which are attributed to the reduced loss of denervated potential and the enhanced normal regenerative potential in the IVFP patients without synkinesis, surpass the adverse effects associated with the abnormal regenerative potential in those with synkinesis. This accounts for the observed overall increase in MPT and SPLmax in the IVFP patients with a disease course of 3–6 months18. In fact, synkinesis is most commonly observed in UVFP patients with nonsurgical etiologies. Patients with synkinesis will have near-complete restoration in the TA-LCA turn frequency but still experience voice impairment, confirmed by the fact that their glottal gap and acoustic parameters were not better than those patients without synkinesis, a finding that is compatible with the mechanism of aberrant reinnervation20,21. However, patients with synkinesis have better disease-related quality of life than those without synkinesis9. Therefore, the patients with synkinesis should be considered a specific subset of UVFP patients with distinct clinical presentation and full restoration of recruitment, but impaired voice presentations. As a result, specific therapeutic plans should be tailored for these patients17. These findings suggest that synkinesis adversely affects voice restoration in the IVFP patients with a disease course of 3–6 months, indicating that the IVFP patients should accept diagnosis and treatment within 3 months after onset to improve their voice qualities, avoiding the adverse effects caused by synkinesis.

Recent reports indicate that the patients with severe RLN injury are more susceptible to synkinesis. The incidence of complete RLN injury is higher among the patients with synkinesis compared to those without synkinesis, suggesting a direct correlation between the severity of RLN injury and the likelihood of synkinesis21. In the IVFP patients with a disease course of 3–6 months who have not yet regained vocal fold movement, more severe RLN damages and synkinesis are evident. However, the impact of synkinesis on the amplitudes of RLN varies based on the disease courses. Specifically, in the IVFP patients with a disease course of less than 3 months, the individuals with synkinesis exhibit lower amplitudes of RLN compared to those without synkinesis. In contrast, among the IVFP patients with a disease course of 3–6 months, those with synkinesis demonstrate significantly higher amplitudes of RLN. Furthermore, a significant interaction effect exists between synkinesis and disease course on the amplitudes of RLN. This indicates that in the early stages of RLN injury among IVFP patients, there is a more frequent occurrence of reduced amplitudes of RLN22. This phenomenon may be attributed to factors such as the absence of a myelin sheath or axonal degeneration, coupled with a lower degree of synkinesis in IVFP23. Denervation potentials were frequently observed in the PCA and TA of the UVFP patients with a disease course of 1 to 3 months24. In contrast, regenerative phenomena, such as synkinesis, were more prevalent in the patients with a disease course of more than 3 months25. This observation elucidates the phenomenon whereby the amplitudes of RLN are elevated, while the amplitudes of PCA and TA are diminished. This finding aligns with the perspective that in chronic RLN paralysis, the intrinsic laryngeal muscles are variably affected by atrophy, synkinesis, or a combination thereof18.

It is well-established that the amplitude of RLN is inversely proportional to the extent of RLN injury, whereas prolonged latency is directly proportional to the severity of injury, indicating impaired conduction characterized by reduced conduction velocity26,27. In the IVFP patients with a disease course of less than 3 months, although instances of synkinesis have been observed, the majority of nerve endings at the injured site have not yet effectively reached their target laryngeal muscles, such as PCA and TA28. Consequently, the amplitudes are reduced for the IVFP patients with synkinesis. In contrast, for the IVFP patients with a disease course of 3–6 months, particularly those with synkinesis, regenerated nerve fibers at the injured site have aberrantly and sufficiently reached the laryngeal muscles. As a result, nerve conduction in these patients has progressively recovered, leading to significantly higher amplitudes of RLN compared to those without synkinesis29.

Certainly, this study is subject to several limitations. Primarily, the assessment of synkinesis remains complicated and contentious, with no established consensus currently available. The methodology employed in this study involved the predominant research approaches for determining synkinesis, categorizing any observed synkinesis in any group of laryngeal muscles, specifically the TA or PCA, as part of the synkinesis group. Conversely, absence of such findings classified subjects into the non-synkinesis group. This approach may result in inclusion criteria that are either insufficiently stringent or overly broad. Additionally, the limited number of the IVFP patients with synkinesis and the absence of detailed classification in synkinesis subtypes necessitate further investigation to elucidate the differential impacts of these subtypes on voice parameters and LEMG results. Lastly, the study includes relatively fewer cases of the IVFP patients with a disease course of more than 6 months, as the majority of patients fall within this timeframe, potentially introducing bias in analysis of synkinesis and influencing the overall research conclusions.

In conclusion, for the IVFP patients with a disease course of less than 3 months, although synkinesis occurs infrequently, the nerve regeneration at the injured site leads to an incomplete and ineffective "nerve-muscle" interface. However, in the IVFP patients with a disease course of 3–6 months, those with synkinesis demonstrated a significant increase in the amplitudes of RLN. Despite these observations, the MPT values continued to decline significantly in the IVFP patients with synkinesis compared to those without synkinesis. This further underscores the detrimental impact of synkinesis on voice restoration for the IVFP patients with a disease course of 3–6 months.

Materials and methods

Subjects

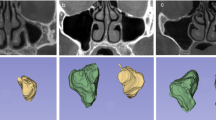

The IVFP patients underwent a thorough diagnostic assessment, incorporating stroboscopic laryngoscopy, computerized voice analysis, and LEMG during their initial consultation at the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, between March 2018 and May 2025. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study were consistent with those outlined in our previous publication30. Specifically, all the suspected IVFP patients were required to undergo brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), chest CT, thyroid ultrasound, and either electronic gastroscopy or esophageal barium X-ray examinations to rule out tumor lesions in these regions. Additionally, a detailed inquiry into the patient’s recent history (within the past 3 months) of tracheal intubation, trauma, or surgery was conducted. For the suspected cases, three-dimensional reconstruction of CT for the cricoarytenoid joint was performed to exclude conditions such as cricoarytenoid joint dislocation. Data collected include variables such as gender, affected side, age at diagnosis, etiology, and the interval between symptom onset and medical evaluation (disease course). Subsequently, all the IVFP patients were categorized into two distinct cohorts based on their disease courses: group 1 consisted of individuals with a disease course of less than 3 months, whereas group 2 comprised those with a disease course of more than 3 months. Furthermore, within each cohort, the patients were further subdivided into two subgroups based on their LEMG results with synkinesis or those without synkinesis (Fig. 1).

Flowchart for comparing the LEMG results of the IVFP patients. Group 1, the IVFP patients with a disease course of less than 3 months; group 2, the IVFP patients with a disease course of 3 to 6 months. IVFP, idiopathic vocal fold paralysis; LEMG, laryngeal electromyography; APD, action potential periods; CT, cricothyroid muscle; DSI, dysphonia severity index; F0min, lowest fundamental frequency; F0max, highest fundamental frequency; MPT, maximum pronunciation time; PCA, posterior cricoarytenoid muscle; RLN, recurrent laryngeal nerve; SLN, superior laryngeal nerve; SPLmin, minimum sound pressure level; SPLmax, maximum sound pressure level; TA, thyroarytenoid muscle; VHI, voice handicap index.

Voice handicap index (VHI)

The Chinese adaptation of VHI was employed to assess self-reported voice disorders among all the IVFP patients31. Participants were directed to allocate scores across three domains: functional (F), physiological (P), and emotional (E), wherein higher scores signified a more remarkable perceived impact on the voice disorder. Thus, an increased cumulative score denoted a more severe subjective evaluation of the voice disorder for the IVFP patients.

Objective acoustic evaluation of voice and calculation of dysphonia severity index (DSI)

A systematic evaluation of vocal acoustics and the calculation of dysphonia severity index (DSI) were conducted in a controlled setting, with ambient noise levels maintained below 40 dB. The DIVAS voice analysis software, developed by XION Company in Germany, was utilized for this assessment. Participants were equipped with a headset microphone positioned 30 cm from the mouth. Following the establishment of relaxation and controlled breathing, participants were instructed to sustain vowel "a" for 2 s, repeated three times. The highest quality sound sample from these repetitions was selected for further analysis. The parameters extracted for analysis included stable segment parameters such as fundamental frequency (F0) and fundamental frequency perturbation (Jitter), as well as MPT, F0max, F0min, SPLmax, SPLmin, and the lowest sound intensity (I-Low). The DSI score was automatically computed by the DIVAS software. A more negative DSI value indicates a greater severity of hoarseness, whereas a less negative DSI value denotes a lower severity of hoarseness.

Stroboscopic laryngoscope

The stroboscopic laryngoscope was utilized to investigate alterations in hypopharyngeal, supraglottic, glottic, and subglottic structures, as well as to evaluate changes in fundamental frequency, vibration amplitude, mucosal wave, symmetry of arytenoid cartilage, with a specific focus on paradoxical vocal fold movement. The instrument employed for this study was the ENDOSTROB, produced in Berlin, Germany.

Laryngeal electromyography (LEMG)

LEMG examination. The LEMG was conducted by two physicians who are board‐certified in electrodiagnostic medicine. It should be noted that the specific information of the IVFP patients were blinded to both the two physicians, and the LEMG results evaluated by them were also blinded to each other. In this study, LEMG signals were obtained using a 37 mm concentric needle electrode in conjunction with the surface-ground electrode adhered to the forehead. The Synergy EMG system (CareFusion, Middleton, WI) was utilized, with filter settings ranging from 20 Hz to 10 kHz. Motor unit recruitment tracings were recorded with sweep speeds of 10 ms per division and a gain of 200 μV per division. For each test, we initially observed the insertional activity and the spontaneous activity. Abnormal LEMG results were defined as the existence of spontaneous activities (such as fibrillation, positive sharp wave, and repetitive discharge), > 30% polyphagia, or decreased interference pattern (reduced, discrete, or no interference pattern). We then performed semiquantitative motor unit analysis and recruitment analysis, specifically when the rise time of a motor unit action potential was less than 0.6 ms, indicating a close proximity to the recorded motor unit30.

Needle electromyography for the laryngeal muscles For the purpose of detecting the electromyography for the laryngeal muscles, the patient’s neck was extended, and 1 to 2 ml of 2% lidocaine hydrochloride were injected into the subcutaneous tissue at the needle-insertion sites. In the case of the CT, the muscle is identified at a distance of 1 cm from the midline. The needle is then angled laterally towards the cricoid cartilage, and the CT function was evaluated by conducting a glissando upward /e/ at normal loudness. As for the TA, the electrode is inserted at a superior angle of 45° and a lateral angle of 20° through the cricothyroid membrane. The TA is typically situated at a depth of 2 cm. The patient was then asked to produce three series of /e/ sounds at three different intensities (low, moderate, and the highest possible), with each /e/ lasting at least 400 ms and each inter-/e/ interval lasting about 200 ms. The maximal sustained /e/ sound is used to represent a contraction of the TA at the highest intensity. Multiple fields were documented for each muscle, with a minimum of three fields recorded. Subsequently, the patient’s neck was rotated by ninety degrees, and a concentric needle electrode was inserted through the posterior aspect of the lamina in the cricoid cartilage. The patient was then instructed to inhale deeply to verify the accurate placement of the concentric needle electrode in the PCA30.

Needle electromyography for the laryngeal nerves Needle electromyography was performed to assess the injured degrees of the laryngeal nerves, with the concentric needle electrodes positioned into the CT and TA serving as the recording electrodes. An additional concentric needle electrode was employed as the stimulating electrode, which was inserted through the thyrohyoid membrane. It was then directed downwards along the path of SLN until reaching the level above the cricothyroid membrane for SLN evaluation. Alternatively, it was inserted 1 cm below the lateral aspect of the cricothyroid membrane and directed upwards along the tracheoesophageal groove until reaching the level of the cricothyroid membrane for evaluation of RLN. The stable compound muscle action potential was obtained by the recording electrode when electric stimulation was administered through the stimulating electrode, regardless of the intensity of stimulation for the SLN and RLN. Subsequently, the latencies and amplitudes of SLN and RLN, reflected by the recording electrodes on both the left and right sides, were compared to determine the affected side of SLN and RLN. Furthermore, the electromyographic characteristics of the IVFP patients were analyzed and compared30.

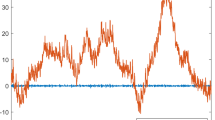

LEMG analysis We developed a Matlab-based program to analyze the raw LEMG data. Firstly, we binned the raw LEMG data in each 200 ms epoch for the TA and PCA, and in each 50 ms epoch for the CT. An automatic algorithm was used to localize the timing of each turn and its amplitude. Specifically, a turn was defined by the change in polarity, with an amplitude of at least 100 µV before and after the change, to exclude peaks inherent to noise. The turn frequency was computed for each epoch as the number of turns divided by epoch duration, and the mean turn amplitude was computed as the mean of the absolute turn-amplitude values. For the CT, TA and PCA, we averaged the turn frequencies for the epochs whose turn frequency ranked among the top three epochs to yield a peak frequency turn index2.

Laryngeal synkinesis

Laryngeal synkinesis encompasses both adductive and abductive synkinesis. Adductive synkinesis is characterized by the TA recruitment during a sniff that is equal to or over its recruitment during phonation. In contrast, abductive synkinesis is identified by any significant activity of the PCA during phonation, as proposed by Isabella and Lin4,9. For all the IVFP patients, the laryngoscope recordings and LEMG results pertaining to synkinesis were documented and judged blindly, and the patients were classified into the synkinesis group if synkinesis was detected in any laryngeal muscle group, specifically in the TA or PCA. Conversely, if no synkinesis was observed, they were categorized into the non-synkinesis group. Ensuring consistency and indisputability in the evaluation of synkinesis confirmed by the LEMG results from the two otolaryngologists is essential. In instances of disagreement regarding the synkinesis status, a third expert is consulted to provide a definitive conclusion. Ultimately, the assessments of synkinesis status conducted by the two otolaryngologists undergo consistency evaluation to ascertain the inter-rater reliability.

Ethical statement

Ethical considerations were rigorously upheld throughout the study, with all participants providing written informed consent in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Furthermore, the research was granted approval by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiao tong University (Approval No. 2022031).

Statistical analysis

The data analysis for this study was performed utilizing SPSS version 23.0, a statistical software package developed by the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) in the United States. To compare the rates of synkinesis among the IVFP patients with different disease courses, the Chi-square test was utilized. Additionally, the temporal association between the synkinesis and disease course was assessed using Spearman rank correlation analysis. Data exhibiting normal distribution and homogeneity of variance were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. These data were analyzed using the independent-sample t-test for comparisons of voice parameters and LEMG results among the IVFP patients with different disease courses, and a two-way ANOVA for comparisons of voice parameters and LEMG results among those with different disease courses and synkinesis statuses. If the results analyzed by the two-way ANOVA were significant (P < 0.05), Bonferroni (a multiple-comparison correction method, m = 2, ɑ = 0.025), was adopted for analysis of the indicators in the IVFP patients with a specific disease course, between the individuals with synkinesis and those without synkinesis, and the P value less than 0.025 represents a significant difference in such condition. The consistency of the two experts’ judgments on the synkinesis status was evaluated using the Cohen’s kappa coefficient. Statistical significance was established at a threshold of P < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Stonebraker, C. et al. Demographics, management, and outcomes associated with idiopathic vocal fold paralysis: A systematic review. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 172, 1856–1865. https://doi.org/10.1002/ohn.1195 (2025).

Chang, W. H. et al. Quantitative electromyographic characteristics of idiopathic unilateral vocal fold paralysis. Laryngoscope. 126, E362–E368. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25944 (2016).

Yan, J. et al. Immediate effect of recurrent laryngeal nerve stimulation in patients with idiopathic unilateral vocal fold paralysis. Acta Otolaryngol. 144, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2024.2306961 (2024).

Stanisz, I. et al. Diagnostic limitation of laryngostroboscopy in comparison to laryngeal electromyography in synkinesis in unilateral vocal fold paralysis. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 278, 2387–2395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-021-06714-8 (2021).

Mueller, A. H. et al. Complementary reinnervation in unilateral vocal fold paralysis. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 10, e70104. https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.70104 (2025).

Tracy, L. F. et al. Vocal fold motion recovery in patients with iatrogenic unilateral immobility: Cervical versus thoracic injury. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 128, 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489418808306 (2019).

Razura, D. E. et al. Posterior cricoarytenoid muscle chemodenervation can improve voice in recalcitrant dysphonia in unilateral vocal fold paresis with synkinesis. J. Voice. S0892–1997(24), 00390–00394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2024.11.007 (2024).

Krasnodebska, P. et al. Vocal fold electromyography in patients with endoscopic features of unilateral laryngeal paralysis. Otolaryngol. Pol. 78, 18–22. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0053.8704 (2024).

Lin, R. J. et al. Effect of intralaryngeal muscle synkinesis on perception of voice handicap in patients with unilateral vocal fold paralysis. Laryngoscope. 127, 1628–1632. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26390 (2017).

Munin, M. C. et al. Consensus statement: Using laryngeal electromyography for the diagnosis and treatment of vocal cord paralysis. Muscle Nerve. 53, 850–855. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.25090 (2016).

Goto, T. et al. Effects of early local administration of high-dose bFGF on a recurrent laryngeal nerve injury model. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 52, 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-023-00647-4 (2023).

Pitman, M. J. et al. Embryologic innervation of the rat laryngeal musculature–a model for investigation of recurrent laryngeal nerve reinnervation. Laryngoscope. 123, 3117–3126. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24216 (2013).

Nagai, H. et al. Effect of fascia implantation and controlled release of basic fibroblast growth factor for muscle atrophy in rat laryngeal paralysis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 167, 319–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998211052895 (2022).

Rubin, F. et al. Idiopathic unilateral vocal-fold paralysis in the adult. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 135, 171–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2018.01.004 (2018).

Kim, D. R. et al. Neuromuscular retraining therapy for early stage severe Bell’s palsy patients minimizes facial synkinesis. Clin. Rehabil. 37, 1510–1520. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692155231166216 (2023).

Jalali, M. M. et al. Pharmacological treatments of Bell’s palsy in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 131, 1615–1625. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29368 (2021).

Pei, Y. C. et al. Implications of synkinesis in unilateral vocal fold paralysis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 157, 1017–1024. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599817721688 (2017).

Zealear, D., Li, Y. & Huang, S. An implantable system for chronic in vivo electromyography. J. Vis. Exp. 158, 10–3791. https://doi.org/10.3791/60345.10.3791/60345 (2020).

Kaneko, M. et al. Regenerative effects of basic fibroblast growth factor on restoration of thyroarytenoid muscle atrophy caused by recurrent laryngeal nerve transection. J. Voice. 32, 645–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.09.019 (2018).

Foerster, G. & Mueller, A. H. PCA atrophy and synkinesis as the main factors for persistent vocal fold immobility in RLN paralysis. Laryngoscope. 131, E1244–E1248. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29195 (2021).

Lin, R. J. et al. Innervation status in chronic vocal fold paralysis and implications for laryngeal reinnervation. Laryngoscope. 128, 1628–1633. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.27078 (2018).

Hu, R., Xu, W. & Cheng, L. The causes and laryngeal electromyography characteristics of unilateral vocal fold paralysis. J Voice. 37, 140.e13-140.e19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.11.022 (2023).

Sadoughi, B. & Andreadis, K. Evaluation of laryngeal motor neuropathy using transcranial magnetic stimulation-mediated evoked potentials. Laryngoscope. 132(Suppl 10), S1–S12. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.30062 (2022).

Smith, L. J. & Munin, M. C. Utility of laryngeal electromyography for establishing prognosis and individualized treatment after laryngeal neuropathies. Muscle Nerve. 71, 833–845. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.28207 (2025).

Foerster, G. et al. Crumley’s classification of laryngeal synkinesis: A comparison of laryngoscopy and electromyography. Laryngoscope. 131, E1605–E1610. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29275 (2021).

Bhatt, N. K. et al. Compound motor action potential duration and latency are markers of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. Laryngoscope. 127, 1855–1860. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26531 (2017).

Baertsch, H. C., Cvancara, D. & Bhatt, N. K. Utilizing novel recurrent laryngeal motor nerve conduction studies to characterize the aging larynx: A pilot study. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 8, 739–745. https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.1071 (2023).

Bhatt, N. K., Kao, W. T. K. & Paniello, R. C. Compound motor action potential measures acute changes in laryngeal innervation. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 127, 661–666. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489418784973 (2018).

Mau, T., Husain, S. & Sulica, L. Pathophysiology of iatrogenic and idiopathic vocal fold paralysis may be distinct. Laryngoscope. 130, 1520–1524. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28281 (2020).

Liu, X. H. et al. A comparative analysis of laryngeal nerve damage in patients with idiopathic vocal cord paralysis exhibiting different paralytic sides. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 9, e1205. https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.1205 (2024).

Ozemir, I. A. et al. Importance of latency and amplitude values of recurrent laryngeal nerve during thyroidectomy in diabetic patients. Int. J. Surg. 35, 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.10.001 (2016).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Fund of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiao tong University (Program No. YJ (ZD) 202302 and Program No. YJ(YB)202302), and the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaan’ xi Province (Program No. 2025JC-YBMS-983).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiao-Hong Liu completed majority of research, participated in conception and design, original draft, conceptualization and data curation. Nan-Cao and Meng-Xie participated in experiment design, data collection and analysis, writing original draft. Na-Li, Min-Juan Yang and Xiao-Ying Du, collected samples, analyzed data and wrote part of original draft. Xiao-Yong Ren, contributed in designing experiments and writing-review. The corresponding author, Hua-Nan Luo, were major contributors in funding acquisition, designed experiments, writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, XH., Nan-Cao, Meng-Xie et al. The impact of synkinesis on voice restoration in idiopathic vocal fold paralysis patients with different disease courses. Sci Rep 16, 106 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29300-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29300-y