Abstract

This study presents an innovative approach for unveiling the hidden relationships between natural frequency patterns and structural parameters in grid-form frames. By analyzing vibrational characteristics, we determine key features, namely the number of vertical beams, boundary conditions, and aspect ratios. Extensive finite element analysis generates a dataset, mapping the natural frequencies as features against structural parameters as labels reveals distinct, streamlined clusters in the feature hyperspace, highlighting an underlying order in the system’s dynamics. An advanced classification and interpolation model navigates these spectral trajectories to predict structural parameters accurately, even in the presence of damage or different materials. This study offers new insights into the intrinsic dynamics of complex structures, inviting further exploration into the subtle interplay between vibrational characteristics and structural identity. These findings open new avenues for research, potentially transforming the understanding of structural behavior in practical engineering applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The precise determination of structural parameters is fundamental to advancing dynamic analysis and predictive modeling. Across engineering disciplines, the challenge of identifying unknown or altered structural characteristics is pervasive, arising from aging infrastructure, design modifications, or incomplete documentation. Successfully addressing this challenge enables critical advancements in structural optimization, high-fidelity model updating, and robust data interpretation. By providing a reliable foundation for digital models, accurate parameter identification also enhances data fusion techniques, ultimately leading to more resilient and predictable structural performance.

Traditional model-based inverse methods have long served as reliable approaches for parameter identification, offering well-understood theoretical foundations and direct physical interpretability. For instance, Yang et al.1 employed Bayesian identification with an interface device to recover unknown substructures, though this approach requires specialized hardware and physical access. Complementing these methods, data-driven approaches leverage machine learning to extract diagnostic patterns directly from operational data. Xu et al.2 demonstrated acoustic anomaly detection by fusing filter-bank features with load information for real-time monitoring. Similarly, Tong et al.3 achieved robust fault diagnosis by converting vibrations to Gramian Angular Field images using dual-attention networks. Extending these concepts, Vu-Huu et al.4 utilized multi-objective optimization to generate engineering-feasible parameter ensembles for improved design and inverse mapping.

The power of identifying characteristic signatures for parameter estimation is exemplified by the “data-driven fingerprint” method in nanoelectromechanical mass spectrometry5, where vibrational frequency shifts serve as unique fingerprints for mass identification without requiring complex device modeling. We extend this fundamental principle to structural frame analysis, adapting pattern-recognition methodology for more efficient parameter identification of common engineering structures. For this purpose, references6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 will be reviewed, which analyze various parameters affecting natural frequencies and vibrational characteristics, and utilize the resulting signatures to identify structural parameters across different structural classes.

Recent advances in vibration-based techniques have paved the way for the reliable extraction of key structural and material properties through inverse analysis. For example, Aryana et al.6 introduced a formulation based on a second order Taylor expansion to express the inverse eigenvalue problem for modifying the structure’s dynamic behavior. Their method, which identifies and locally modifies the most sensitive regions of a finite element model, demonstrated that significant changes in natural frequencies can be achieved with minimal induced error. Building on this foundational study, Türker et al.7 later demonstrated that correlating experimental flexural vibrations with theoretical models could accurately identify both the mass distribution and elastic modulus of fixed-end beams. In a similar manner, Ihesiulor et al.8 applied computational intelligence methods to detect and localize delamination in composite laminates by analyzing shifts in natural frequencies, even under noisy conditions. Extending this approach, Khan et al.9 developed a convolutional neural network framework to classify and predict various in-plane and through-the-thickness delaminations in smart composite laminates. The model achieved over 90% classification accuracy by automatically extracting discriminative features from vibration spectrograms. Geuzaine et al.10 established guidelines for determining the axial force, flexural rigidity, and rotational end stiffness in slender, tensioned cables using analytical approximations derived from measured low-frequency responses. Similarly, Salehi et al.11 refined the estimation of boundary conditions in railway bridges using artificial neural networks. Their sensitivity analysis on a finite-element model significantly reduced the error between computed and measured modal frequencies, highlighting the critical influence of boundary conditions on dynamic behavior.

Goldfeld et al.12 proposed an exact element method–based procedure for identifying the continuous stiffness distribution in beams by monitoring selective modal frequency shifts. Representing the stiffness profile as a polynomial function, their approach used a sensitivity matrix derived from a healthy beam model and was validated against both analytical predictions and experimental data. In contrast, Sha et al.13 addressed crack localization in beams by introducing a two‐step probabilistic framework that employs Bayesian data fusion of relative frequency changes, effectively handling both single and multiple damage scenarios without the need for mode shape information. Similarly, Heshmati et al.14 demonstrated that artificial neural networks trained on finite element–generated frequency data can reliably detect horizontal cracks in steel beams, underscoring the promise of machine learning in damage localization while also emphasizing that the quality of the simulation data remains critical. Lee et al.15 combined finite element model updating with deep learning by calibrating a reference model from measured modal frequencies and training networks on simulated damage‐induced frequency shifts. In this work, experimental validation on three‐story frame structures demonstrated the method’s excellent reliability.

Dynamic identification techniques have also reached large-scale structures. Hernández-Montes et al.16 introduced a Bayesian approach for identifying the structural parameters of cultural-heritage buildings using ambient vibration data. They combined frequency and modal information via a probabilistic modal assurance criterion and applied it successfully to a sixteenth-century monastery to quantify uncertainties in key finite-element model parameters. Building on this theme, Wu et al.17 used a surrogate-assisted multi-objective slap-swarm algorithm with a Gaussian process model for vibration-based parameter identification of concrete dams, achieving accurate estimations and significant computational savings. Complementing these studies, Gioffrè et al.18 solved the inverse problem of tie-rod mechanical properties in historical masonry by merging experimental vibration measurements with uncertainty-informed probabilistic modeling, yielding robust tensile-force and stiffness estimates crucial for structural resilience. Finally, Naranjo-Pérez et al.19 developed a Finite Element Method (FEM) updating approach based on free-vibration structural parameter identification. The method embeds experimental modal properties within a maximum likelihood optimization accelerated by a novel combinative algorithm, and was demonstrated on both a laboratory footbridge and a complex heritage structure to significantly reduce simulation time without compromising parameter accuracy.

Based on these efforts, Zhang et al.20 developed an impulse excitation technique using square specimens to establish a robust relationship between modal frequencies and elastic parameters, facilitating the inverse identification of both Poisson’s ratio and Young’s modulus. Finally, Mahat et al.21 introduced a frequency-informed modal analysis that nondestructively evaluates the elastic properties of solid materials with high precision.

Understanding the dynamic response of structures is crucial for ensuring their safety and longevity. A key aspect of this behavior is the system’s natural frequency, which governs its inherent vibrational characteristics. When external forces coincide with a structure’s natural frequency, resonance can amplify displacements and potentially lead to catastrophic failure. To mitigate this risk, accurately determining natural frequencies is an essential need that has driven the development of methodologies ranging from classical analytical formulations to modern computational tools. Analytical and semi-analytical methods, such as Rayleigh–Ritz method, offer foundational insights but are limited by idealized geometries and simplifying assumptions22. For intermediate complexity problems, the extended Kantorovich method reduces partial differential equations to ordinary differential equations for efficient eigenvalue solutions, yet struggles with highly nonlinear or intricate geometries23. Generalized differential quadrature method then emerged, approximating derivatives via weighted sums and delivering high accuracy with fewer grid points for relatively smooth problems24. In contrast, the finite element method subdivides structures into a detailed mesh of finite elements, effectively handling complex geometries, irregular domains, and nonlinear materials. By directly computing mode shapes and resonant frequencies through discretized eigenvalue analysis25, FEM has become the gold standard for structural dynamics, as evidenced by its widespread application to frames, beams, composites, shells, and sandwich panels. Moreover, many works have been undertaken using these methods26,27,28,29,30,31.

Gao26 provided an analytical framework by introducing the random factor method and interval factor method. In this approach, the structural parameters are separated into deterministic and random parts, and analytical expressions for natural frequencies and mode shapes are derived using the Rayleigh quotient and algebra synthesis of random variables. Following this, Ansari et al.27 adopted a semi-analytical method for double-walled carbon nanotubes by integrating Eringen’s nonlocal elasticity with the classical Donnell shell theory. They implement the Rayleigh–Ritz technique with a polynomial series representation to solve the governing differential equations. Similarly, Fallah et al.28 utilized a semi-analytical approach by applying the extended Kantorovich method along with an infinite power series solution to analyze the free vibration behavior of moderately thick functionally graded plates on an elastic foundation.

Based on these analytical and semi-analytical methods, later studies incorporate more advanced numerical techniques to address complex geometries and material uncertainties. Tornabene et al.29 extended the analytical concepts to doubly-curved shells with variable thickness by using a local generalized differential quadrature method that integrates higher-order equivalent single layer theories, thereby enhancing the accuracy of dynamic response predictions. In a further advancement, Tomar et al.30 combined higher order shear deformation theory with stochastic finite element methods to tackle material uncertainties in skewed, sandwich functionally graded plates, allowing for a comprehensive quantification of vibration and bending behaviors under uncertainty. Continuing this trend, Furtmüller31 introduced a novel finite plate element tailored for concrete–cross-laminated timber composite plates that employs a higher-order plate theory to capture the characteristic zig-zag deformations in timber layers. By accounting for the partial interaction between concrete and timber and reducing computational complexity compared to traditional continuum models, this approach demonstrates the evolving capability of finite element methods to analyze advanced composite structures with both static and dynamic accuracy.

By using these developments in dynamic analysis methods, especially FEM, many studies have examined the dynamic behavior of frame structures particularly the relationship between natural frequencies and the structures’ geometric and material parameters32,33,34,35,36,37,38.

Senba et al.32 investigated the vibration reduction in variable geometry trusses by optimizing motion plans to avoid resonance during payload manipulation. Their finite element model adjusted trajectories and variable member lengths to effectively reduce vibration amplitudes and stresses. In parallel, Sofi et al.33 addressed the parameter uncertainties by evaluating the bounds of natural frequencies through an improved interval analysis method that transforms the generalized interval eigenvalue problem into two deterministic eigenvalue problems, accurately capturing the variability in truss and beam structures.

Pham et al.34 proposed a fuzzy finite element framework to analyze the free vibration response of functionally graded semi-rigid frame structures. Their approach features a novel Timoshenko beam element that accounts for connection rigidity, along with a response-surface-based fuzzy analysis using the α–cut strategy and first-order Taylor’s approximation to incorporate uncertainties in material properties, dimensions, and connection conditions. Similarly, Gonenli et al.35 investigated the effect of crack location on the buckling and dynamic stability of thin plate structures that behave as frame systems. Although their study primarily focuses on plate frames, the FEM model directly relates to the analysis of frame structures under damage conditions. Xu et al.36 further extended FEM applications by developing a direct numerical simulation procedure that integrates Floquet theorem and harmonic balance methods, enabling the assessment of dynamic instability in frame structures, including complex behaviors such as multi-mode coupling and flexural–torsional deformations.

In addition, Alaei et al.37 utilized FEM in a parametric study on Persian brick masonry arches, which can be considered arch-type frame structures. Their work examined the influence of various geometric parameters and support conditions on natural frequencies, leading to the formulation of an empirical equation validated by experimental modal analysis. Complementing these studies, Jafari-Talookolaei et al.38 addressed the free vibration analysis of general planar frame structures composed of laminated composite beam members. They introduced a comprehensive displacement field that captures shear deformation, rotary inertia, material coupling, and warping effects, with FEM results showing excellent agreement with 3D ANSYS simulations. Collectively, these studies demonstrated the versatility of the finite element method in accurately modeling and analyzing the dynamic behaviors of a wide range of frame and frame-like structures.

Despite the extensive body of literature on the influence of structural parameters on vibrational behavior, a comprehensive review of recent studies reveals that dedicated and efficient data-driven frameworks for directly identifying these parameters from measured dynamic responses remain largely unexplored. This gap is particularly evident in frame structures, where accurately defining physical parameters is crucial for reliable modeling. We propose a direct, pattern-based approach to identify structural parameters from free-vibration signatures, establishing a foundation for scalable applications. Developing such a method not only enhances optimization in structural design39 and supports data fusion techniques for damage diagnosis, but also improves data preprocessing, providing a more accurate representation of the structure’s true condition40.

In the following section, we introduce the mathematical formulation of the frame structure using a finite element method. This section details the FE formulation and presents a novel Gaussian damage function developed specifically for applying damage to beams. Next, we introduce a new clustering method designed to group spatial data points that form streamline-like patterns. After validating our FE approach and the Gaussian damage function through calibration with beam data, we proceed to discuss the FE-generated dataset. Here, we explore the relationship between structural parameters and the natural frequencies of the frame. Building on these findings, we propose a predictive model that estimates the frame parameters from its natural frequencies, using the previously introduced clustering method. This model is evaluated via a modified split-test method to identify sensitive parameter combinations that are challenging to predict solely from natural frequency data. Finally, we assess the robustness of our model by applying damage to these sensitive areas, demonstrating its high accuracy in the presence of environmental variations and structural uncertainties.

Problem definition

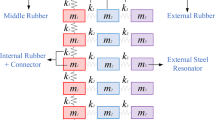

The grid form of the frame structure being investigated in the current work is shown in Fig. 1a. As can be seen the structure is composed of \(N-1\) identical sub-frames, where \(N\) is the number of vertical beams and the \({i}^{th}\) vertical beam is numbered above it. Except for the last vertical beam, all sub-frames have two horizontal beams across them at the bottom and top. Using this fact, we name each member in the structure by \(bea{m}_{i,j}\), where \(i\) represent a vertical beam index running from 1 through \(N\) and \(j\) can be 1, 2 or 3. Here, \(bea{m}_{i,1}\) corresponds to the \({i}^{th}\) vertical beam, and \(bea{m}_{i,2}\) and \(bea{m}_{i,3}\) correspond to the bottom and top horizontal beam in front of the \({i}^{th}\) vertical beam, respectively. The vertical beams have a length \({L}^{v}\), and the distance between two vertical beams is denoted as \({L}^{h}\). Therefore, the total length of the structure is \(L={L}^{h}\times \left(N-1\right)\). In the following sections, we use the aspect ratio constant \(AR={L}^{h}/{L}^{v}\) to specify the lengths of the horizontal and vertical beams41. Additionally, from Fig. 1b we can see all beams have identical rectangular cross-section with width \(b\) and height \(h\). Four different arbitrary boundary conditions are considered for this investigation, as shown in Fig. 1c. Each boundary condition is defined by the parameter \(\it \text{BC}\), where \(BC=1\) to \(BC=4\) represent the following boundary conditions, respectively:

-

1.

\(BC=1\): All corners of the frame are simply supported.

-

2.

\(BC=2\): All corners are clamped.

-

3.

\(BC=3\): The two bottom corners are clamped, and the two top corners are simply supported.

-

4.

\(BC=4\): The two bottom corners are clamped, and the other two corners are free.

For each member of the frame, we considered the displacement field based on Timoshenko beam theory that is shown in Fig. 1d. The following equations represent these displacement fields34:

In these expressions, \(u\) and \(w\) denote the displacements parallel to the \(x\)-axis and \(z\)-axis, respectively. The term \(\phi\) represents the bending rotation of the cross-section. The variables \({u}_{0}\) and \({w}_{0}\) correspond to the displacements along the mid-plane of the beam.

Mathematical formulation

Build on the considered displacement field, the non-zero strains associated with them can be formulated as follows:

In this context, \({\varepsilon }_{x}\) and \({\varepsilon }_{xz}\) represent the axial normal strain and the transverse shear strain, respectively. The associated normal stress \({\sigma }_{x}\) and shear stress \({\tau }_{xy}\) can be determined using the linear elastic constitutive equations:

where \(\kappa\) denotes the shear correction factor, which is \(\kappa =5/6\) for a rectangular cross-section. Additionally, \(E\) and \(G\) represent the elastic (Young’s) modulus and the shear modulus of the material, respectively. These two moduli are related through the following formula:

where \(\upsilon\) is the Poisson’s ratio. The total kinetic energy \(T\) of the entire beam can be formulated as:

Here, \(\rho\) represents the material density, and \(L\) denotes the length of the beam. The parameters \(A\) and \(I\) correspond to the cross-sectional area and the moment of inertia of the beam, respectively. The strain potential energy \(U\) of the beam is expressed as:

Finite elements formulation

In this section, we use the previously described kinetic and potential energy formulations for a single beam to derive the mass and stiffness matrices of the defined elements. By applying a formulation to reduce the stiffness matrix, we assemble these matrices into a global matrix. This allows us to determine the natural frequencies of the structure. Figure 2 presents the element details that is used to discretizing the beam in this work. Figure 2a shows the element with a total length of \(Le\), has three nodes where two of them are at the ends of the element and one is in the middle. Each node has three degrees of freedom, represented as \({u}_{i}\), \({w}_{i}\) and \({\phi }_{i}\) corresponding to the node \(i\) (\(i=\text{1,2},3\)).

Figure 2b shows the intrinsic coordinate \(\xi =(2x-Le)/Le\) of the considered element. The displacement components \(u\) and \(w\), along with the bending rotation \(\phi\), are interpolated in this coordinate using the following expressions25:

The shape functions \({\Phi }_{i}\left(\xi \right)\), where \(i=\text{1,2},3\), represent the Lagrangian interpolation polynomials corresponding to each node of the element. These functions are formulated as follows25:

We define the element’s degrees of freedom vector, denoted by \(\left\{\delta \right\}\), as follows:

Here, the superscript \(T\) denotes the transpose of a vector or matrix. By applying the shape functions, we establish a relationship between the beam’s displacements and rotations and the nodal degrees of freedom, leading to the following expression:

An effective approach for calculating the stiffness and mass matrices of the element is the energy method. To derive these matrices for the beam element under consideration, we substitute Eq. (10) into (5) and (6), which leads to the following expression:

Here, \( \{\dot{\delta}\}\) denotes the velocity vector of the beam element, and \(\left[Me\right]\) and \(\left[Ke\right]\) are the element’s mass and stiffness matrices, respectively. These matrices are calculated as follows:

Frame share the same material and cross-sectional properties, except for their lengths, which may differ between vertical and horizontal beams and can be expressed by \(i\ \text{and} \ j \) indices of each member. This variation in length leads to distinct mass \(\left[Me\right]\) and stiffness \(\left[Ke\right]\) matrices for vertical and horizontal members. Now the assembled mass matrices of each member \({\left[M\right]}_{ij}\) can be calculated. To model a damaged beam, stiffness matrix of the beam members needs to be calculated after applying stiffness reduction method to their elements14. The following expression calculates the stiffness matrix of the \({n}^{th}\) element of \(bea{m}_{i,j}\) in the frame:

where parameter \({\alpha }_{ij}^{n}\) quantifies the loss of stiffness in the \({n}^{th}\) element of the \(bea{m}_{i,j}\). In this work, we use a developed gaussian damage function to calculate the parameter \(\alpha\). Based on three parameter Gaussian damage function used in42, we introduce the following four parameters to define a damage in beam:

-

1.

Damage location (\(\mathfrak{L}\)): Normalized center location of the damage along the beam. Here, \(\mathfrak{L}=0\) corresponds to the damage at the beginning of the beam, while \(\mathfrak{L}=1\) indicates damage at the end of the beam.

-

2.

Damage severity (\(\mathfrak{S}\)): presents losing stiffness in element \(0<\mathfrak{S}<1\), where \(\mathfrak{S}=0\) indicates no loss in stiffness, and \(\mathfrak{S}=1\) signifies that the stiffness of the element becomes zero.

-

3.

Damage width (\(\mathfrak{W}\)): presents the length of the damaged region normalized by the total length of the beam, over which the beam’s stiffness is most significantly affected.

-

4.

Damage dispersal (\(\mathfrak{D}\)): It indicates that the damage disperses beyond the initial damage region. Higher values of \(\mathfrak{D}\) results in stiffness to be reduced just in \(\mathfrak{W}\) region, and low values of this parameter lead to more smooth damage reduction along the beams.

Using these new four parameters,\({\alpha }^{n}\) for the corresponding \({n}^{th}\) element in the beam can be calculated using the following expression:

where \({\overline{\mathfrak{W}}} = \lfloor{\mathfrak{W}}/Le\rfloor\) represent number of damaged elements; also \(n_{s} = \lfloor{\mathfrak{L}}\left( \frac{L}{Le} \right) - {\overline{\mathfrak{W}}}/2\rfloor\) and \(n_{e} = \lfloor{\mathfrak{L}}\left( \frac{L}{Le} \right) + {\overline{\mathfrak{W}}}/2\rfloor\) indicate the starting and ending element index of the damaged region, respectively. Figure 3 illustrated these above parameters and method, where also middle element of damage \(n_{m} = \left\lfloor {{\mathfrak{L}}\left( {\frac{L}{{Le}}} \right)} \right\rfloor\), is presented.

Similar to the previous section, the following section uses these four parameters with subscript \(i,j\), which defines them for \(bea{m}_{i,j}\) in the frame structure.

After calculating the assembled stiffness and mass matrices of each frame member, the assembled stiffness and mass matrices of the entire frame can now be obtained. To do this, it is essential to consider the continuity conditions of the degrees of freedom at the beam’s joint section. As illustrated in Fig. 4, each vertical beam is connected at both ends to two horizontal beams in such a way that the end nodes of the vertical beam align precisely with the corresponding nodes on the horizontal beams.

Considering that, at the non-shared nodes, the mass and stiffness matrices of the horizontal and vertical beams do not interact with each other, we define the transformation matrix \(\left[T\right]\) to map the degrees of freedom of the two end nodes of the vertical beam to those of the horizontal beams. This transformation is presented below38:

Importantly, the transformation matrix \(\left[T\right]\) is consistent across all vertical beams. Since only the degrees of freedom at the two end nodes require modification, while the intermediate nodes maintain their displacement fields unchanged, the matrix \(\left[T\right]\) for these intermediate nodes effectively becomes an identity matrix \(\left[I\right]\) whose size corresponds to the number of intermediate degrees of freedom. If \({\left[K\right]}_{i,j=1}\) and \({\left[M\right]}_{i,j=1}\) represent the total stiffness and mass matrices of the vertical beam, the modified stiffness \(\bar{{{\left[K\right]}}}_{i,j=1}\) and mass \(\bar{{{\left[M\right]}}}_{i,j=1}\) matrices can be obtained as:

After using these matrices to obtain the overall mass and stiffness matrices of the frame, we can move on to discretizing the equations of motion for free vibration, which are as follows:

In these equations, \(\left[K\right]\) and \(\left[M\right]\) denote the global stiffness and mass matrices, respectively, while, \(\{\ddot{\Delta }\}\) and \(\left\{\Delta \right\}\) represent the total acceleration vector and the vector of degrees of freedom. Assuming a general solution of the form \(\left\{\Delta \right\}=\left\{{\Delta }_{0}\right\}{e}^{i\omega t}\) for Eq. (19), we arrive at the following equation:

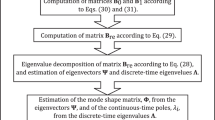

Here, \(\omega\) denotes the system’s natural frequency, and \(\left\{{\Delta }_{0}\right\}\) is the associated mode shape. The nontrivial solutions of Eq. (20) emerge from resolving the determinant equation \(\text{det}\left(\left[K\right]-{\omega }^{2}\left[M\right]\right)=0\). This process leads to the extraction of the system’s vibrational characteristics. Figure 5 illustrates the flowchart of the finite element (FE) model of the frame, highlighting its inputs and outputs to enhance the understanding of how the final mathematical expressions function.

Streamline clustering methodology

Clustering algorithms play a pivotal role in identifying intrinsic structures within datasets, particularly in scenarios where data points exhibit directional or flow-like patterns. In this paper, we propose a novel streamline clustering algorithm designed to detect clusters that align with directional trends originating from a user-specified initial point based on cosine similarity computation algorithms43. Traditional centroid-based clustering methods often prioritize compactness or density, which may fail to capture anisotropic or trajectory-oriented structures. Algorithm 1 constructs a streamline cluster \(L\) around an initial point \(p\), iteratively extending it bidirectionally while enforcing directional consistency among neighboring points.

The algorithm begins by initializing the ordered cluster \(L\) with the user-specified point \(p\) (Line 02). The cluster expands bidirectionally by dynamically capturing geometrically aligned neighbors at its current endpoints, \({p}^{h}\) and \({p}^{t}\) where the superscripts \(t\) and \(h\) stand for ‘tail’ and ‘head’. At each iteration, the algorithm identifies \(m\) nearest neighbors to \({p}^{h}\) and \({p}^{t}\) within the dataset \(X\), restricted to points ahead of \({p}^{h}\) (\(X>{p}^{h}\)) or behind \({p}^{t}\) (\(X<{p}^{t}\)) to enforce ordered growth (Lines 05–06). For each neighbor \({N}_{i}^{h}\) or \({N}_{i}^{t}\), direction vectors \({V}_{i}^{h}={N}_{i}^{h}-{p}^{h}\) and \({V}_{i}^{t}={N}_{i}^{t}-{p}^{t}\) are computed to quantify alignment. Subclusters \({l}_{i}^{h}\) and \({l}_{i}^{t}\) are then formed by grouping neighbors whose direction vectors exhibit near-parallelism, determined by a cosine similarity threshold (Lines 07–14). Specifically, if the normalized dot product (Lines 12,13), the vectors are deemed collinear, and their corresponding points are merged into the same subcluster. The subcluster with the largest membership at each end is appended (for the head) or prepended (for the tail) to \(L\), ensuring incremental extension along the most consistent local direction (Lines 16–17). This bidirectional expansion repeats until \(L\) stabilizes in size (Line 18), indicating that no further aligned points can be incorporated. By prioritizing geometric alignment over raw proximity, the algorithm captures directional trends inherent to the data, making it particularly effective for flow-like structures where clusters follow smooth, contiguous paths.

Results and discussion

Convergence and validation

In this section, a convergence test is conducted for both the intact frame and the damaged beam. Additionally, to verify the accuracy of the proposed formulations and also the developed computer programs, the results for both the intact and damaged frame and beam are compared with those obtained from the commercial ANSYS software. All subsequent analyses use a beam with a rectangular cross-section made of steel, with the following material and geometric properties: \(E=200\text{ GPa},\rho =7850 \text{kg}/{\text{m}}^{3}, \upsilon =1/3, L={L}_{h}=1\text{ m},h=0.05\text{ m},b=0.1\text{ m}\).

Figure 6 presents the convergence results for a frame with \(N=6\), \(BC=1\) and \(AR=1\). Convergence was monitored using the frequency deviation, defined as \(100\times \left|{{\omega }_{j}^{i}-\omega }_{j}^{i-1}\right|/{\omega }_{j}^{i-1}\), where ‘\(j\)’ corresponds to the mode number and ‘\(i\)’ denotes the current iteration as the number of elements per beam increases from ‘\(i-1\)’ to ‘\(i\)’. As shown, the frequency deviation decreases logarithmically as the number of elements increases. A mesh density of 50 elements per beam was selected for all subsequent analyses, as the rate of change in the results beyond this point becomes negligible.

Now that the frame model has converged, its accuracy is validated by comparing the first three natural frequencies with those obtained from ANSYS. Table 1 presents these results for a frame with \(AR=1\), considering two different numbers of vertical beams and four types of boundary conditions.

A convergence study was conducted for a cantilever beam incorporating the damage function. The damaged case, characterized by the parameters (\({\mathfrak{S}}=0.5, {\mathfrak{W}}=0.2, {\mathfrak{L}}=0.5,{ \mathfrak{D}=1}\)), is presented in Fig. 7. The results demonstrate a similar convergence trend to the intact frame; the change in frequency becomes negligible beyond approximately 50 elements per beam, as the response stabilizes with no significant further variation. Consequently, a mesh density of 50 elements per beam was adopted for all subsequent damaged beam analyses to maintain consistency and computational efficiency.

Since no existing studies directly address a Gaussian damage function model for beams, we validated the present model using ANSYS simulations. The simulations were first conducted for a cantilever beam, whose properties are detailed at the beginning of this section. Table 2 lists the first three natural frequencies of the intact cantilever beam, as calculated using both ANSYS and present method.

To model the damage in ANSYS, we represent the beam with 50 separate sections, each corresponding to an element in our current FE model, then Young’s modulus of these sections is updated based on the corresponding element Young’s modulus in FE model. We considered previous cantilever beam with nine different damage scenarios for validation. The losses in Young’s modulus of these scenarios per element are represented by their \({\alpha }^{n}\) values in Fig. 8 for \({n}^{th}\) element in the beam.

As can be seen the considered scenarios are composed of varying between three different values for damage location (\({\mathfrak{L}}=0.2, 0.5, 0.8\)) and damage dispersal (\({\mathfrak{D}}=100, 10, 1\)) and two other damage parameters are as follows: \({\mathfrak{S}}=0.75, {\mathfrak{W}}=0.1\). Table 3 presents the first three natural frequencies of corresponding to these damage scenarios calculated by ANSYS and present method. Notably, the clamped end corresponds to element one, while the free end corresponds to element 50.

Another validation was conducted for a damaged frame with two different numbers of vertical beams, each subjected to two different damage widths. The first three natural frequencies are listed in Table 4 for a model with fixed parameters (\(AR=1, BC=1, {\mathfrak{S}}=0.75, {\mathfrak{D}}=1000,{ \mathfrak{L}= 0.5}\)) and compared against ANSYS results, where the damage was applied on \(bea{m}_{\text{1,2}}\). As can be seen, the results of the present work closely match those obtained from ANSYS for all intact and damage cases, demonstrating strong validation of the proposed approach.

Dataset description

Following the successful validation of the FE model, which demonstrated high accuracy in predicting the natural frequencies of the frame structures, we are now well-positioned to investigate their vibrational behavior. To begin our analysis, the material and geometric properties of the validated beam model were held constantly. Table 5 introduce Dataset \(X\), which comprises the first five natural frequencies(\(\text{rad/s}\)) of 2400 specific frame structures. By systematically varying three parameters (6 distinct quantities of \(N\), four types of \(BC\), and 100 values of the \(AR\) uniformly distributed between 0.41 and 2.1), the first five natural frequencies of these structures, along with their three corresponding varying parameters, are compiled in \(X\). The material and geometric properties of the validated beam model were held constant and can be seen in this table.

With dataset \(X\) established, we now turn to analyzing its vibrational characteristics in the following section.

Frame vibrational characteristics

In this section, we aim to analyze the introduced dataset \(X\) to understand the relationship between variable parameters and natural frequencies, and work toward predicting these parameters based on the natural frequencies. Figure 9a represents the distribution of the five natural frequencies for all structures in \(X\), displayed using both box plots and violin plots. It can be inferred that higher-order natural frequencies exhibit a larger distribution width and significantly larger mean values. Additionally, for each natural frequency, the distribution shows a higher density at lower values, with similar patterns observed across all frequencies. Figure 9b illustrates the parameter sensitivity analysis of the first five natural frequencies by quantifying their variance distributions across three distinct parameter sets:

\(\to\) Variance of natural frequencies across all values of \(N\), with \(AR\) and \(BC\) held constant.

\(\to\) Variance of natural frequencies across all values of \(N\), with \(AR\) and \(BC\) held constant.

\(\to\) Variance of natural frequencies across all values of \(AR\), with \(N\) and \(BC\) held constant.

\(\to\) Variance of natural frequencies across all values of \(AR\), with \(N\) and \(BC\) held constant.

\(\to\) Variance of natural frequencies across all values of \(BC\), with \(N\) and \(AR\) held constant.

\(\to\) Variance of natural frequencies across all values of \(BC\), with \(N\) and \(AR\) held constant.

A preliminary analysis reveals that parameter \(N\) exerts the strongest influence on natural frequency variations, followed by \(AR\), with \(BC\) showing the least impact.

Notably, in the first natural frequency, the influence of parameter \(N\) exhibits a pronounced divergence from parameters \(AR\) and \(BC\). This distinct separation suggests that \(N\) may function as a dominant driver of variability in the first natural frequency. To examine this, Fig. 10 shows the distribution of the normalized first natural frequency (\({\omega }_{1}/{\omega }_{1,max}\) ) compared with those for each of the six \(N\) values.

It can be observed from this figure that larger \(N\) values are concentrated in the lower range of the normalized first natural frequency, while smaller \(N\) values correspond to higher \({\omega }_{1}\) values. Additionally, the density peak in the \({\omega }_{1}\) distribution appears to correlate statistically with the distribution of the \(N\) parameter. In Fig. 11, we investigate whether the \(N\) parameter can be inferred from the distribution peaks of the normalized first natural frequency. Figure 11a represents the histogram of \({\omega }_{1}/{\omega }_{1,max}\) which provides higher resolution to distinguish distribution peaks. Notably, this histogram reveals six distinct peaks region (\({S}_{1},\dots ,{S}_{6}\)) corresponding to the six \(N\) values, a feature that could not be clearly resolved in the earlier distribution plots of \({\omega }_{1}\). Figure 11b displays the normalized observation for each of the six \(N\) values across the peak regions \({S}_{1}\) to \({S}_{6}\).

As can be seen, the \(N\) values can be distinguished based on the first natural frequency \({\omega }_{1}\); however, this method lacks accuracy for higher \(N\) values due to the high density of \({\omega }_{1}\) within the corresponding domain. Building on the similar peak patterns observed across all natural frequencies in Fig. 9a, we hypothesized that the correlation between \(N\) values and these peaks could also extend to the four additional natural frequencies and help us to reach better accuracy for finding \(N\) values.

Unlike the first natural frequency, which exhibits a strong correlation with \(N,\) higher-order frequencies show a weaker discernible link to \(N\). Instead, the influence of the two other parameters \(AR\) and \(BC\) dominates their behavior, as demonstrated in Fig. 9b. To clarify these attributes, Fig. 12 shows the sensitivity of the first five natural frequencies to parameters \(AR\) and \(BC\), for six different values of \(N\), separately.

From this Figure, we observe that the effects of \(AR\) and \(BC\) on certain natural frequencies can be distinguished. However, the natural frequency to which these parameters’ impacts are separable depends on the value of \(N\). For example, at \(N = 3\), the first three natural frequencies exhibit clear separation between \(AR\) and \(BC\) driven effects. In contrast, at \(N = 8\), the same frequencies show overlapping influences of \(AR\) and \(BC\), requiring classification methods to disentangle their contributions. To visualize how these patterns govern the natural frequencies, we plot them in a three-dimensional space in Fig. 13. This figure comprises 10 subfigures, each corresponding to one of the 10 combinations of three natural frequencies selected from the five of them, labeled systematically as \({C}_{1}\) to \({C}_{10}\).

As can be distinguished from these ten sub-figures, the dataset exhibits a striking resemblance to streamlined curves or trajectories within the feature space. These visualizations suggest distinct geometric patterns that organize the data into coherent, unlabeled structures. To advance our goal of identifying structural labels derived from the natural frequency combinations, the subsequent section will employ clustering techniques to partition these curves into meaningful groups. By uncovering clusters, we aim to systematically associate them with structural labels, characterize their relationships to the natural frequencies, and identify correlations that may map these groups to specific structural configurations. This approach will enable data-driven classification of the system’s underlying structural identity. Figure 14 shows the workflow of the clustering method that is used.

As it can be seen in this method, after assigning arbitrary labels to each sample in \(X\), we used Algorithm 1 to find the streamlines locally around a random point in each of ten plots (\({C}_{1},\dots ,{C}_{10}\)). After finding these local streamlines ‘\(L\)’ and storing them into the cluster repository ‘\({L}_{R}\)’, the elements of \(L\) are removed from \({X}_{i}\), where \({X}_{i}\) is the dataset corresponding to plot \({C}_{i}\) for \(i=1,\dots ,10\). This loop continues until \({X}_{i}\) is empty, and the computation is applied to all \(i\) from one to ten. At the end, all clusters that were stored in \({L}_{R}\) are merged based on their arbitrary labels. This step aims to prevent duplication in clusters if two clusters have the same members. This step also helps in joining the separated sharp-angled streamlines when connectivity of those can be observed from another cluster in \({L}_{R}\). Figure 15 project the results of applying discussed clustering method to \(X\) in \({C}_{1}\).

As can be seen, 24 clusters have been found as streamlines with this methodology, which can be recognized in above figures by the specific color and index adjust to them in right side. Although the high density of the points in lower values of natural frequencies, makes the observation of the clusters in these regions almost impossible, but in Table 6, the properties of these cluster across some examinations of their true labels, makes a clear presentation of them.

At first glance, we can find out that the variance of \(N\) and \(BC\) labels on each cluster are zero or so close to zero, representing that the streamlines identified through the current clustering method each correspond to specific labels of \(BC\) and the \(N\) which can be found out by the mean values of these labels in corresponding cluster. In another word, for a given combination of boundary conditions and vertical beam count, all structural aspect ratios generate a streamline within the frequency plot. By analyzing the size of these 24 streamlines, it is evident that each has a size of approximately 100 which corresponds to the number of aspect ratios included in the dataset for a specific combination of \(N\) and \(BC\). Figure 16a illustrates the correlation between changes in \(AR\) and shifts in the first natural frequencies for each of the 24 unique combinations of vertical beams and boundary conditions. As shown in all 24 streamlines, the \(AR\) exhibits a strong correlation with natural frequencies, with correlation coefficients consistently exceeding 0.8.

Also in Fig. 16b, for each of the 24 combinations of \(N-BC\), a multivariate linear model is fitted from the five natural frequencies to \(AR\), and plotted predicted versus actual \(AR\) as a single semi-transparent scatter. As it can be seen, the cloud of all points lies tightly about the dashed line; also, the overall RMSE is 0.021. RMSE is root mean square error for interpolation results for \(AR\) predictions, defined by following formulation39:

where \(m\) is total number of the prediction’s cases for \(AR\), also \(A{R}_{i}\) and \({\overline{AR} }_{i}\) are true \(AR\) labels and predictions of it in prediction case \({i}^{th}\) respectively. These diagnostics indicate that the relationship is essentially linear over the sampled range.

These robust relationships imply that, for a given combination of \(N\) and \(BC\), if the natural frequency and \(AR\) of two points in the frequency plot are known, the value of a third point between them can be predicted using simple linear interpolation. Specifically, either the \(AR\) or natural frequency of the intermediate point can be estimated based on the linear trend established by the two known data points. Based on these findings, we introduce an algorithm in the next section that, given the input natural frequency, can determine or predict these three parameters.

Model development and sensitivity analysis

From our original dataset \(X\), we generate a new dataset \(XL\) containing predicted structural properties. This \(XL\) dataset comprises 24 sub-datasets, each corresponding to specific values of \(N\) and \(BC\). Within each sub-dataset, there are 100 samples representing 100 distinct aspect ratios for the given \(N\) and \(BC\) defined in Table 5. Thus, \(XL\left(N,BC\right)\) encapsulates the five natural frequencies and their corresponding aspect ratios for 100 structures with the specified \(N\) and \(BC\). Figure 17 illustrates our methodology for estimating the structural properties from the input natural frequencies \({\Omega }_{input}\), which consist of the first five natural frequencies of the structure.

In this flowchart, the input natural frequencies \({\Omega }_{input}\) are first projected onto each of the ten \({C}_{i}\) combinations. For each \({C}_{i}\) the Euclidean distance between the input point and every \(N-BC\) entry in the corresponding \(XL\left(N,BC\right)\) sub-dataset is calculated. These distances are then stored in \({D}_{i}\left(N,BC\right)\). Subsequently, we identify the minimum values of \(N\) and \(BC\) across the summation of \({D}_{i}\) for all \(i\). These minimums are denoted as \(\overline{N }\) and \(\overline{BC }\) representing our predictions for the number of vertical beams and boundary conditions of the input natural frequency structure. Next, within the sub-dataset \(XL\left(\overline{N },\overline{BC }\right)\), we locate the two natural frequencies and aspect ratios closest to \({\Omega }_{input}\). Using linear interpolation between these two nearest points and the input \({\Omega }_{input}\), we estimate the aspect ratio of the frame structure, denoted as \(\overline{AR }\).

To establish performance baselines and contextualize the efficacy of our proposed model, we employed two widely recognized machine learning algorithms; Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machines (SVM). Table 7 evaluates the performance of the proposed model using a 70% training and 30% testing split of the \(XL\) dataset. No validation split was required, as the model lacks tunable hyperparameters. The accuracy represented the percentage of true classification results, and RMSE for evaluation of interpolation in \(AR\) predictions. Since each streamline corresponds to a unique \(N-BC\) combination, the training data must include all 24 streamlines to ensure robust classification. Data was partitioned uniformly across streamlines to preserve their integrity, as removing any subset risks fragmenting streamlines and disrupting the interpolation process for \(AR\) prediction.

The proposed model demonstrates outstanding performance in predicting structural properties from frequency signatures. For classification, it attains 100% accuracy for both the \(N\) and the \(BC\), substantially outperforming the comparative SVM and RF classifiers. In the interpolation stage for \(AR\) prediction the model achieves an extremely low RMSE indicating a marked improvement in precision. Overall, these findings demonstrate the model’s superior accuracy across both classification and interpolation tasks. This design of uniform split-test inherently precludes standard cross-validation methods42; consequently, to further assess model performance under varying data conditions, we tested non-standard split sizes with smaller training percentages and larger test splits to previous analysis in Fig. 18.

The dual-axis plot illustrates in Fig. 18a, demonstrates interplay between classification errors for \(\overline{N }\) and \(\overline{BC }\), and RMSE of \(\overline{AR }\) as training data size increases. \(\overline{N }\) achieves 0% error just below 10% training data size, while \(\overline{BC }\) errors vanish entirely before 25% training data size. Simultaneously, the right y-axis tracks the RMSE for \(\overline{AR }\), which decreases from \(0.1\) to \({10}^{-3}\), demonstrating the interpolation stage’s refinement with additional training. The green dashed line which is RMSE of \(\overline{AR }\) when \(\overline{N }\) and \(\overline{BC }\) are correctly classified, consistently lies below the solid line which is RMSE including misclassified cases, underscoring that residual \(\overline{AR }\) errors are primarily due to misclassification of \(N-BC\), not interpolation flaws. By 25% training data, both RMSE lines converge, as \(\overline{N }\) and \(\overline{BC }\) errors have already reached zero.

Figure 18b evaluates the impact of input parameters on prediction results in Fig. 18a for all training set size tests. The two top sub-figures show that most classification errors arise from inputs with \(N=\text{5,6}\) and \(BC=\text{1,2}\), suggesting ambiguity in these configurations’ frequency signatures. Third sub-figure down these two, represent the RMSE of \(\overline{AR }\) (\(y\)-axis) In all tests that is done in Fig. 18a across by input \(AR\) range (\(x\)-axis). For example, each small bar shown in this figure that has unique values for \(AR\) in \(x\)-axis, represents RMSE of \(\overline{AR }\) for all testes in Fig. 18a that have similar \(AR\) input as inputs. We can see that RMSE peaks at \(AR=0.5\dots 0.75\) and \(AR=1.0\dots 1.25\), highlight structural geometries where interpolation struggles. In the next sections, we conduct a robust test on these critical and sensitive structural parameter combinations by introducing simulated damage and structure that is made by different materials, evaluating the model’s performance under real-world-like scenarios.

Model robustness assessment under structural damage

The model’s ability to maintain accuracy under such perturbations is critical for practical deployment. Unlike previous tests, which focused on data scarcity, here we simulate physical degradation in sensitivity-prone configurations which is applying damage to them. This evaluates how natural frequency distortions impact predictions. To quantify these distortions, we introduce the Frequency Shift Index named FSI, a metric defined as the normalized root mean square of percentage changes in natural frequencies, calculated as:

where \({\omega }_{i}^{{\text{base}}{\text{line}}}\) and \({\omega }_{i}^{\text{current}}\) are \({i}^{th}\) natural frequencies of non-damaged and damaged structures with similar variable labels (\(N, BC, AR\)).

Table 8 present prediction results across two sensitive parameter combinations under increasing damage severity, quantified by FSI. The damage applied on \(bea{m}_{\text{1,2}}\) of each structure, other damage parameters considered as follow: \({\mathfrak{L}}=0.5, {\mathfrak{W}}=0.1, {\mathfrak{D}}=10\).

The results in this table reveal two critical trends. First, no classification errors are observed for \(N\) and \(BC\) across all tested damage severities. Second, we can see that difference between \(\overline{AR }\) and actual values of \(AR\) correlate to increasing damage severity and FSI values, but the \(\overline{AR }\) remain remarkably close to the actual values across all cases.

Move over, Table 9 evaluates the combined impact of \(bea{m}_{i,j}\) selection and damage location within the chosen beam on the model’s prediction accuracy. For this analysis, we selected two new identified critical configurations. The damage severity in this table is chosen to be \({\mathfrak{S}}=0.75\) where it has more impact on model results based on last table. other damage parameters are as follows: \({\mathfrak{W}}=0.1, {\mathfrak{D}}=10\).

It is noteworthy that due to the symmetry of the frame structure, applying damage to symmetrically equivalent beams yield identical natural frequency responses. To eliminate redundancy, only non-symmetric beam-location pairs are evaluated, as symmetric counterparts provide no additional frequency-distinctive information.

This table reveals that all \(\overline{N }\) and \(\overline{BC }\) are correct predictions. Therefore, damage at the center of beams produces the highest FSI values and results in \(\overline{AR }\) be less accurate. Similarly, damage to horizontal beams that are near corners of the frame, elevates FSI and \(\overline{AR }\) errors, suggesting geometric asymmetry near boundaries exacerbates frequency distortions. This confirms damage location critically impacts prediction reliability, particularly in edge cases.

Table 10 evaluates the influence of two additional damage parameters, damage width and dispersal on prediction accuracy. Two new structural configurations are examined in this table under identical damage conditions applied on \(bea{m}_{\text{1,2}}\) with following damage parameters: \({\mathfrak{L}}=0.5, {\mathfrak{S}}=0.75\).

Again, no errors occur in \(\overline{N }\) or \(\overline{BC }\) predictions in all considered cases with very close \(\overline{AR }\) value Relative to the actual value of \(AR\). However, we can see that damage weight strongly correlates with FSI values and \(\overline{AR }\) errors, similarly, damage dispersal amplifies errors but with lower impact.

Finally, we evaluate the robustness of our model under worst-case scenarios involving multiple simultaneous damages in Table 11 for the last two combinations of critical structure parameters. These scenarios, focus on cases where damages have the most significant impact on natural frequencies and model prediction errors, which are applying highly destituted damage with larger damage width and severity on center of the beams that is close to boundary conditions region. These damages are applied to four beams: \(bea{m}_{\text{1,2}}, bea{m}_{\text{2,1}}, bea{m}_{\text{2,2}}, bea{m}_{\text{3,1}}\), with other damage properties that are as follows: \({\mathfrak{L}}=0.5\text{, }{\mathfrak{S}}=0.75, {\mathfrak{W}}=0.2, {\mathfrak{D}}=1\).

This table demonstrates that even under high FSI values caused by severe damages, model all predictions for \(\overline{N }\) and \(\overline{BC }\) remains accurate and the interpolation results for \(\overline{AR }\) also stays Acceptably accurate considering the significant changes in natural frequencies.

Model robustness assessment under different materials

In this section, the model’s robustness is further assessed by applying it to structures made of two additional materials- stainless steel and aluminum- while maintaining identical frame geometries and boundary configurations. The corresponding results are presented in Table 12. The material properties used in this comparison are summarized in as follow: \(\text{Stainless steel}:E=193 {\text{Gpa}}, \rho =8000 \text{kg}/{\text{m}}^{3},\upsilon =0.3.\) Aluminum \(:E=69 {\text{Gpa}}, \rho =2700 \text{kg}/{\text{m}}^{3}, \upsilon =0.33\).

For reference, the baseline frame corresponds to the steel properties used in constructing the dataset from which the model was originally trained. The natural frequencies corresponding to each frame–material combination were computed and used as model inputs to evaluate the predicted results. The FSI for each case was also recalculated using the \({\omega }_{i}^{{\text{base}}{\text{line}}}\) with original steel properties as a reference to maintain consistency in comparison.

The results show that all cases were correctly classified with no misclassifications, and \(\overline{AR }\) predictions match the true values closely. Stainless steel shows slightly larger \(\overline{AR }\) prediction errors which is consistent with its higher FSI values and greater frequency shifts, whereas aluminum yields smaller deviations. In all cases, the predicted \(\overline{AR }\) remain acceptably close to actual values.

Conclusion

The identification of structural parameters in grid-form frames can be fundamentally re-envisioned by treating natural frequency data as a structured landscape of modal signatures. This work introduces a direct, three-phase computational methodology to navigate this landscape. In the first phase, a comprehensive modal map is generated via finite element analysis to capture the first five natural frequencies across diverse configurations. In the second phase, the intrinsic low-dimensional streamline topologies within this map are discovered and characterized, where each trajectory encodes a unique combination of the number of vertical beams (\(N\)) and boundary conditions (\(BC\)). Finally, a classification–interpolation model is deployed to instantly map a new set of frequencies to its corresponding streamline, identifying \(N\) and \(BC\), followed by precise interpolation along the trajectory to determine the aspect ratio (\(AR\)).

This pattern-based methodology presents a fundamental shift from conventional approaches by eliminating dependency on iterative inverse analysis and high-fidelity physical modeling, which are often susceptible to convergence issues and modeling inaccuracies. Instead, the framework learns the direct relationship between vibrational signatures and structural identity through a precomputed data-driven map. This bypasses the need for complex, error-prone characterization, offering a robust and computationally efficient pathway for parameter identification. By transforming a traditionally challenging inverse problem into a streamlined pattern-recognition task, this work provides a universally applicable foundation for rapid and scalable structural assessment, significantly advancing the practical implementation of non-destructive evaluation in structural health monitoring.

The practical application of this methodology is bounded by the scope of its training dataset, wherein a tolerable error can be defined based on the predefined parameter ranges it was designed to identify. Several avenues remain open for further investigation to enhance its robustness and scope. Future studies could integrate common sources of frequency shifts not considered here, such as material damping and environmental effects, into the pattern recognition model. Furthermore, the influence of different damage types and their interaction with geometric parameters presents a critical research direction. Ultimately, these findings establish a foundational stage for launching a new class of structural health monitoring techniques that leverage intrinsic modal patterns for efficient and direct structural assessment.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because further analyses are underway and we wish to avoid premature release, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yang, J., Liu, Y., Lu, X. & Wang, T. An adaptive measurement-based substructure identification framework for dynamic response reconstruction. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 239, 113277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2025.113277 (2025).

Xu, X., Deng, J., Lin, H., Li, Z. & Wen, H. Lightweight anomalous detection of hydro turbine operation sound using fusion network enhanced by load information. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 74, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2025.3533632 (2025).

Tong, A., Zhang, J. & Xie, L. Intelligent fault diagnosis of rolling bearing based on Gramian angular difference field and improved dual attention residual network. Sensors 24, 2156. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24072156 (2024).

Vu-Huu, T., Khatir, S. & Cuong-Le, T. Real-world steel frame optimization using a hybrid leader selection-based multi-objective flow direction algorithm. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. https://doi.org/10.1002/nme.70098 (2025).

Sader, J. E., Gomez, A., Neumann, A. P., Nunn, A. & Roukes, M. L. Data-driven fingerprint nanoelectromechanical mass spectrometry. Nat. Commun. 15, 8800. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51733-8 (2024).

Aryana, F. & Bahai, H. Sensitivity analysis and modification of structural dynamic characteristics using second order approximation. Eng. Struct. 25, 1279–1287. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0141-0296(03)00078-6 (2003).

Türker, T. & Bayraktar, A. Structural parameter identification of fixed end beams by inverse method using measured natural frequencies. Shock. Vib. 15, 505–515. https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/692962 (2008).

Ihesiulor, O. K., Shankar, K., Zhang, Z. & Ray, T. Delamination detection with error and noise polluted natural frequencies using computational intelligence concepts. Compos. B Eng. 56, 906–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.09.032 (2014).

Khan, A., Ko, D.-K., Lim, S. C. & Kim, H. S. Structural vibration-based classification and prediction of delamination in smart composite laminates using deep learning neural network. Compos. B Eng. 161, 586–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.12.118 (2019).

Geuzaine, M., Foti, F. & Denoël, V. Minimal requirements for the vibration-based identification of the axial force, the bending stiffness and the flexural boundary conditions in cables. J. Sound Vib. 511, 116326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2021.116326 (2021).

Salehi, M. & Erduran, E. Identification of boundary conditions of railway bridges using artificial neural networks. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 12, 1223–1246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13349-022-00613-0 (2022).

Goldfeld, Y. & Elias, D. Using the exact element method and modal frequency changes to identify distributed damage in beams. Eng. Struct. 51, 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2013.01.019 (2013).

Sha, G., Radzieński, M., Cao, M. & Ostachowicz, W. A novel method for single and multiple damage detection in beams using relative natural frequency changes. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 132, 335–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2019.06.027 (2019).

Heshmati A, Saadatmorad M, Talookolaei R-AJ, Valvo PS, Khatir S. Damage identification in thin steel beams containing a horizontal crack using the artificial neural networks, 2023, p. 114–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-24041-6_9.

Lee, Y., Kim, H., Min, S. & Yoon, H. Structural damage detection using deep learning and FE model updating techniques. Sci. Rep. 13, 18694. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46141-9 (2023).

Hernández-Montes, E. et al. Bayesian structural parameter identification from ambient vibration in cultural heritage buildings: The case of the San Jerónimo monastery in Granada, Spain. Eng. Struct. 284, 115924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2023.115924 (2023).

Wu, Y., Kang, F., Zhang, Y., Li, X. & Li, H. Structural identification of concrete dams with ambient vibration based on surrogate-assisted multi-objective Salp swarm algorithm. Structures 60, 105956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.105956 (2024).

Gioffrè, M., Grigoriu, M. D. & Pepi, C. Uncertainty-informed identification of tie-rod mechanical properties in monumental buildings. Eng. Struct. 321, 118979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.118979 (2024).

Naranjo-Pérez, J. et al. Robust improvement of the finite-element-model updating of historical constructions via a new combinative computational algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 190, 103598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2024.103598 (2024).

Zhang, L., Zhang, W., Xu, H. & Ma, Y. A new method for identifying elastic parameters of isotropic materials based on square specimens. Sci Rep 14, 21051. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71111-0 (2024).

Mahat, S., Sharma, R., Jeong, H. & Liu, J. Natural frequency informed finite element modal analysis method for estimating elastic properties of solid materials. J. Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0231087 (2024).

Meirovitch, L. Analytical Methods in Vibrations (Macmillan, 1967).

Kerr, A. D. An extended Kantorovich method for the solution of eigenvalue problems. Int. J. Solids Struct. 5, 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7683(69)90028-6 (1969).

Bert, C. W. & Malik, M. Differential quadrature method in computational mechanics: A review. Appl. Mech. Rev. 49, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3101882 (1996).

Logan DL. A First course in the finite element method. Cengage Learning; 2011.

Gao, W. Natural frequency and mode shape analysis of structures with uncertainty. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 21, 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2006.05.007 (2007).

Ansari, R., Rouhi, H. & Sahmani, S. Calibration of the analytical nonlocal shell model for vibrations of double-walled carbon nanotubes with arbitrary boundary conditions using molecular dynamics. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 53, 786–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2011.06.010 (2011).

Fallah, A., Aghdam, M. M. & Kargarnovin, M. H. Free vibration analysis of moderately thick functionally graded plates on elastic foundation using the extended Kantorovich method. Arch. Appl. Mech. 83, 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00419-012-0645-1 (2013).

Tornabene, F., Fantuzzi, N. & Bacciocchi, M. The local GDQ method for the natural frequencies of doubly-curved shells with variable thickness: A general formulation. Compos. B Eng. 92, 265–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.02.010 (2016).

Tomar, S. S. & Talha, M. Influence of material uncertainties on vibration and bending behaviour of skewed sandwich FGM plates. Compos. B Eng. 163, 779–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.01.035 (2019).

Furtmüller, T. A finite element for static and dynamic analyses of concrete–cross-laminated timber composite plates. Eng. Struct. 328, 119704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2025.119704 (2025).

Senba, A., Oka, K., Takahama, M. & Furuya, H. Vibration reduction by natural frequency optimization for manipulation of a variable geometry truss. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 48, 939–954. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-013-0933-6 (2013).

Sofi, A., Muscolino, G. & Elishakoff, I. Natural frequencies of structures with interval parameters. J. Sound Vib. 347, 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2015.02.037 (2015).

Pham, H.-A., Truong, V.-H. & Vu, T.-C. Fuzzy finite element analysis for free vibration response of functionally graded semi-rigid frame structures. Appl. Math. Model 88, 852–869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2020.07.014 (2020).

Gonenli, C. & Das, O. Effect of crack location on buckling and dynamic stability in plate frame structures. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 43, 311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40430-021-03032-2 (2021).

Xu, C., Wang, Z. & Li, H. Direct FE numerical simulation for dynamic instability of frame structures. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 236, 107732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2022.107732 (2022).

Alaei, A., Hejazi, M., Vintzileou, E., Miltiadou-Fezans, A. & Skłodowski, M. The effect of geometric parameters on natural frequencies of Persian brick masonry arches. Structures 58, 105666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.105666 (2023).

Jafari-Talookolaei, R.-A., Sadripour, S. & Valvo, P. S. In-plane and out-of-plane vibration analysis of laminated composite frames with warping effects. Compos. Struct. 331, 117895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2024.117895 (2024).

Miller, B. & Ziemiański, L. Optimizing composite shell with neural network surrogate models and genetic algorithms: Balancing efficiency and fidelity. Adv. Eng. Softw. 197, 103740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2024.103740 (2024).

Zhang, B. et al. A review of methods and applications in structural health monitoring (SHM) for bridges. Measurement 245, 116575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2024.116575 (2025).

Karimi-Asrami, A. & Jafari-Talookolaei, R.-A. Free and forced vibration analysis of functionally graded porous frames. Eng. Comput. https://doi.org/10.1108/EC-10-2024-0981 (2025).

Dakhili, K., Schommer, S. & Maas, S. Automated damage assessment of prestressed concrete bridge beam based on sagging. Discov. Civ. Eng. 1, 59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44290-024-00065-z (2024).

Dongjiang, L., Leixiao, L. & Jie, L. A trajectory similarity computation method based on GAT-based transformer and CNN model. Sci. Rep. 14, 16173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67256-7 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ali Karimi-AsramiConceptualization; Methodology; Software; Validation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Resources; Data Curation; Writing - Original Draft.Ramazan-Ali Jafari-Talookolaei:Conceptualization; Methodology; Formal analysis; Resources; Writing - Review & Editing; Supervision; Project administration.Arman Mardani:Methodology; Data Curation; Writing - Review & Editing; Supervision; Project administration.Elyorjon Jumaev:Methodology; Investigation; Writing - Review & Editing.Orifjon MikhlievMethodology; Investigation; Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karimi-Asrami, A., Jafari-Talookolaei, RA., Mardani, A. et al. Identification of frame geometry and boundary conditions from free-vibration modal signatures. Sci Rep 16, 3279 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29390-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29390-8