Abstract

High-accuracy fish-species identification is a key prerequisite for adaptive, disease-reducing precision feeding in automated polyculture systems. However, severe underwater degradation–light fluctuation, turbidity, occlusion, and species similarity–cripples biomass and fish-count accuracy, while conventional CNN-based methods lack biological priors to recover lost semantic cues. To overcome these limitations, this study proposes a knowledge-augmented framework that integrates a Fish Multimodal Knowledge Graph (FM-KG) with deep visual recognition. Unlike existing approaches that rely solely on pixel-level restoration or visual features, the proposed FM-KG fuses multi-source biological and environmental information to encode species-specific semantics. Its semantic embeddings drive a Semantically-Guided Denoising Module (SGDM) that restores degraded images by emphasizing biologically meaningful structures, while a Knowledge-Driven Attention Dynamic Modulation Layer (K-ADML) adaptively re-weights spatial and channel attention according to inter-species relations within the knowledge graph. A downstream classifier then performs fine-grained species recognition. Experiments on aquaculture datasets demonstrate that the proposed framework consistently outperforms state-of-the-art underwater image enhancers and recognizers, particularly under low signal-to-noise and severe blur conditions. This work establishes a semantically grounded, knowledge-enhanced paradigm for mitigating information loss in aquatic vision, providing a foundation for robust and intelligent aquaculture automation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Accurate species recognition is the cornerstone of any intelligent aquaculture system. Real-time identification of fish species and behavioral monitoring enables data-driven feeding strategies, ensuring that dynamic adjustments can be made according to the biomass ratios of polyculture species. This not only supports individualized feeding and reduces feed iste but also enhances feed conversion efficiency and mitigates the risk of disease outbreaks caused by water pollution. Achieving such precise management fundamentally relies on high-confidence recognition models capable of robust performance in practical aquaculture environments.

Despite its importance, underwater species recognition remains extremely challenging. Complex light variations, turbidity, occlusion, and morphological similarities between species significantly impair the accuracy of biomass estimation and counting. Compared to air, water exhibits exponentially stronger absorption and scattering of light, which reduces contrast, blurs structural details, and distorts colors (e.g., blue–green shifts) in captured images1. In addition, suspended particles, plankton, and dynamic lighting conditions introduce both random and structured noise2, further eroding critical diagnostic cues such as fin ray topology, subtle pigmentation, precise contours, and body patterning. These degradations undermine the reliability of automated recognition systems and limit the scalability of current aquaculture monitoring solutions.

The rapid progress of deep learning offers promising opportunities to overcome these obstacles. Deep learning-based monitoring methods have demonstrated remarkable adaptability in harsh environments, where traditional techniques struggle. The categorization of such methods includes semi-supervised approaches, exemplified by3, and generative techniques like4. Moreover, unsupervised pre-training strategies such as5 have shown the potential to extract reliable features even from noisy or incomplete data. These advances suggest that carefully designed deep learning architectures can provide a pathway toward robust species recognition in complex underwater settings.

Building upon this potential, most existing underwater fish image analysis pipelines adopt a sequential “enhancement-then-recognition” paradigm. In the enhancement stage, approaches based on physical imaging models (e.g., dark channel prior2, underwater light transmission equations1), as well as data-driven convolutional neural networks (CNNs)6,7 and generative adversarial networks (GANs)8, attempt to restore latent clear images at the pixel level. However, these methods generally lack high-level semantic understanding, optimizing primarily for low-level statistical features. In heavily degraded scenarios, this often results in over-smoothing of critical biological details or the introduction of artifacts, exacerbating recognition ambiguity. In the recognition stage, even high-performing models such as ResNet or YOLO–successful on benchmarks like ImageNet and COCO–suffer steep performance drops on low-quality underwater imagery9. The root cause lies in a “semantic gap” induced by physical degradation: the systematic disruption of the link between pixel-level observations and species-level biological concepts (e.g., “barbels of Cyprinidae,” “black spots of Epinephelus spp.”), preventing models from extracting reliable discriminative features.

In contrast, ichthyologists interpreting degraded imagery can leverage their internalized biological knowledge: even without visible caudal fin textures, they can infer missing traits from body proportions, head profiles, and known habitat priors. This suggests that equipping computational models with a queryable, reasoning-enabled “fish knowledge brain” could break the performance ceiling of purely data-driven approaches. A multimodal knowledge graph (MMKG), with its structured “entity–relation–entity” triples, is well-suited to encode cross-modal ichthyological priors, encompassing taxonomic hierarchies, morphological descriptions (text), representative phenotypic images, habitat associations, and genetic markers10. Injecting this structured knowledge into deep models in a differentiable manner enables a paradigm shift from “blind” pixel restoration to “semantically guided” repair and enhancement.

Based on this insight, this study proposes an Underwater Degraded Image Semantic Enhancement and Recognition Framework driven by a Fish Multimodal-information Knowledge Graph (FM-KG), integrating structured domain knowledge with deep learning to achieve semantically guided denoising and feature enhancement. The main contributions are as follows:

-

Construction of a domain-specific FM-KG through systematic integration of heterogeneous sources including FishBase, the China National Freshwater Aquatic Germplasm Resources Database, UFD2022, and FishNet, combined with a cross-modal entity alignment and relation extraction pipeline. The resulting FM-KG covers 1,418 bony fish species, 112,763 high-quality phenotypic images, and 27,942 phenotype–habitat association triples, providing structured priors for subsequent semantic guidance.

-

Proposal of a semantically guided denoising module (SGDM) that introduces semantic embedding vectors from FM-KG as conditional priors into a denoising network, enabling selective preservation and restoration of regions critical for species identification while suppressing noise.

-

Development of a knowledge-driven attention dynamic modulation layer (K-ADML) that leverages “species–key feature” relation weights in FM-KG to construct a learnable modulation matrix for dynamically adjusting channel and spatial attention distributions in convolutional feature maps, thereby enhancing the visibility of biologically important traits such as fins, scales, and patterns.

-

Introduction of semantic gap quantification metrics, including Cross-modal Retrieval Accuracy (CMRA) and Fine-grained Attribute Alignment Accuracy (FAAA), in addition to conventional image quality and classification accuracy, to evaluate the ability of a model to bridge the semantic gap from both image–knowledge consistency and attribute-level semantic fidelity perspectives.

Related works

This section reviews the research progress in underwater image processing, underwater object recognition, and the application of knowledge graphs in visual tasks, and analyzes the advantages and limitations of existing methods.

Underwater image enhancement and denoising

Underwater imaging suffers from inherent light attenuation, scattering, and interference from suspended particles, resulting in multiple degradations such as low contrast, color casts, blur, and noise. According to the degree of reliance on prior assumptions and model structures, existing methods can be broadly categorized into three types: physics-based, non-physical prior-based, and deep learning-based methods.

Physics-based methods

These methods are grounded in the Jaffe-McGlamery imaging model11, which describes underwater image formation as the combination of direct light from the object, backscattered light, and forward-scattered light. Based on this model, researchers estimate parameters and perform inverse modeling to restore image clarity. For example, Rahmati et al. introduced the Dark Channel Prior (DCP) and its variants into underwater scenes. By assuming that at least one color channel in a local non-sky region approaches zero, the background light and transmission map are estimated using the prior, and a clear image is reconstructed2. However, the diversity of underwater scenes (e.g., some fish have naturally vivid colors) often invalidates these priors, leading to color distortion or artifacts.

Non-physical prior-based methods

These methods do not rely on explicit imaging models but aim to improve visual perception through pixel-level operations. Representative techniques include global/local histogram equalization, Gray-World white balancing, and Retinex variants. They have low computational complexity and strong real-time performance, making them convenient for deployment on lightweight embedded platforms. Nevertheless, these methods generally perform global adjustments, often neglecting local details. Additionally, their parameters usually require manual tuning, making adaptation to complex underwater environments difficult.

Deep learning-based methods

With the emergence of large-scale synthetic and real underwater datasets, deep learning methods have rapidly become mainstream due to their end-to-end mapping capability. These approaches can be further divided into convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs).

In CNN-based approaches, researchers design various convolutional architectures to learn mappings from degraded images to clear images. For instance, Yang et al. proposed a lightweight LAFFNet model to directly regress clear images using CNNs7. Li et al. proposed WaterNet, which uses a gated fusion network to combine the advantages of white balance, gamma correction, and histogram equalization preprocessing to directly estimate physical parameters12. Kasat et al. designed PRIDNet, a deep CNN that incorporates noise estimation, multi-scale denoising, and feature fusion, with channel attention to enhance denoising performance13. While these methods achieve strong results on specific datasets, their generalization is limited, and they struggle to recover semantic information in severely degraded images.

Beyond traditional CNNs, GANs have been widely applied due to their strong image generation capability. For example, Zhu et al. employed CycleGAN for unpaired underwater image enhancement14, and Islam et al. proposed FUNIE-GAN, a fully convolutional conditional model with multiple loss functions (including content, style, and perceptual losses) to achieve high-quality real-time underwater image enhancement15. However, although GANs can generate visually realistic results, they still face challenges in detail fidelity and semantic consistency, sometimes producing “hallucinated” textures that do not reflect reality.

In summary, existing enhancement/denoising methods mainly focus on pixel-level visual quality, treating underwater images as content-agnostic signals and largely ignoring fish-specific color patterns, morphological priors, and ecological semantics. When the goal shifts to “recovering fine-grained discriminative features lost due to degradation,” these methods often perform inadequately. This content-agnostic approach is fundamentally why they struggle with deeper challenges such as semantic information restoration.

Underwater fish recognition

Underwater fish recognition is essentially a fine-grained image classification or object detection task. Early studies relied on hand-crafted features such as SIFT, SURF, and HOG, combined with classifiers like SVM or Adaboost. These methods are sensitive to image quality and require extensive domain expertise for feature design.

With the rise of deep learning, CNN-based models have become the mainstream for fish recognition. Researchers transfer CNN models pretrained on large-scale datasets such as ImageNet (e.g., AlexNet, VGG, ResNet, EfficientNet) to fish recognition tasks, achieving significantly better performance than traditional methods. For example, Tamou et al. applied transfer learning for classification on publicly available datasets such as Fish4Knowledge16. Waghumbare et al. adopted a “enhance-then-recognize” cascade approach to address underwater image quality issues17. Ruan et al. designed an improved CNN network, DeformableFishNet, to enhance image resolution for detection tasks18. However, as previously mentioned, the enhancement process itself may introduce noise or information loss, causing errors to accumulate along the processing chain.

Currently, the main challenges in underwater fish recognition include:

-

Dataset limitations: Existing datasets, such as Fish4Knowledge (F4K), LifeCLEF, DeepFish, and UIEB, are limited in scale, species coverage, class balance, and annotation quality12,18,19,20,21.

-

High inter-species similarity: Differences between closely related species are often subtle, e.g., fin count or spot patterns. Conventional CNNs tend to overfit global textures and insufficiently attend to critical local regions.

-

Complex environmental interference and occlusion: Vegetation, turbid water, and overlapping schools of fish result in incomplete targets, causing instance-level detection and segmentation errors in traditional detect-then-recognize pipelines.

These challenges highlight a core bottleneck: existing models primarily learn at the pixel-feature level and fail to acquire and utilize stable, interpretable biological knowledge of fish. Effective, targeted incorporation of fish biological knowledge is required to improve feature extraction and separation efficiency in discriminative underwater scenarios.

Knowledge graphs and their applications in visual tasks

A knowledge graph (KG) encodes entities in the real world and their semantic relationships in the form of a graph structure, thereby constructing a computable and inferable semantic network22. With the development of knowledge graph embedding (KGE) techniques, models such as TransE, DistMult, and ConvE have successfully mapped discrete symbolic knowledge into low-dimensional continuous vectors, enabling knowledge to be directly computed and utilized by machine learning models23,24,25,26.

In recent years, knowledge graphs have been systematically introduced into computer vision tasks, providing models with prior knowledge and significantly enhancing reasoning capability. In the field of scene graph generation, Chen et al. proposed a “Knowledge-Embedded Routing Network,” which propagates messages through the knowledge graph via a routing mechanism and leverages statistical correlations among objects to “regularize the semantic space”27. Zhang et al. employed a knowledge graph to enforce global consistency on object relations, effectively suppressing semantically contradictory pseudo-relations and ensuring the rationality of generated graphs28. In image captioning tasks, Shi et al. incorporated object attributes and commonsense interactions through knowledge graphs to enrich the content and plausibility of generated descriptions29, while Niu et al. exploited commonsense constraints from knowledge graphs to improve narrative coherence and ensure alignment with real-world knowledge30. In zero-shot or few-shot scenarios, Zhong et al. leveraged class hierarchies or attribute similarities provided by knowledge graphs (e.g., “cat” and “tiger” both belonging to the “felid” family) to enable semantic transfer31. Similarly, Kenneth Marino et al. applied knowledge graphs in the remote sensing domain to efficiently match geographical details32, thereby reducing reliance on large-scale annotated datasets.

Particularly, multimodal knowledge graphs (MMKGs) integrate visual information such as images and videos as one modality of entities or attributes, fused with other modalities such as text, to build richer and more comprehensive knowledge systems33,34. The construction of MMKGs involves key techniques such as entity alignment35,36, relation extraction, and multimodal information fusion37. In addition, graph neural networks (GNNs), such as GCN and GAT, are capable of effectively capturing the topological structure of knowledge graphs and play a crucial role in embedding learning and information fusion within MMKGs38.

Although knowledge graphs have demonstrated great potential in general vision tasks, their application in the specific and challenging domain of underwater image recognition remains very limited–particularly in using KGs to actively guide low-level processes such as denoising and feature enhancement39. Existing studies mainly focus on high-level semantic reasoning, with few attempts to inject knowledge-driven priors into pixel-level denoising and feature-level enhancement. This paper pioneers the exploration of employing knowledge graphs as guidance to proactively intervene in underwater image degradation restoration and representation enhancement, offering an innovative perspective for knowledge-driven modeling in underwater visual tasks.

Methods

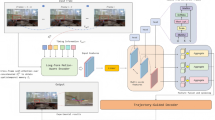

To address the degradation of fish recognition performance in underwater scenarios caused by severe image quality deterioration, this study proposes an end-to-end recognition framework that integrates a Fish Multimodal Knowledge Graph (FM-KG). This section introduces the construction of FM-KG, the overall architecture of the recognition framework, as well as the methods for semantic-guided denoising, attention-based dynamic modulation, and image recognition optimization. As shown in Fig1.

Data collection

The FM-KG data used in this study primarily consists of knowledge-embedded image data. Constructing a high-quality and large-scale domain-specific knowledge graph forms the cornerstone of this research methodology. The preparation and construction process of FM-KG follows the standardized pipeline of data collection, knowledge extraction, and knowledge graph storage and embedding40.

During data source preparation, the following heterogeneous datasets are integrated:

-

FishBase: The world’s largest online fish database, containing 65,300 fish images and 36,100 records of taxonomic status, morphological descriptions, and ecological habits. After filtering, it provides detailed descriptions for 870 fish species and 8,975 high-definition (HD) underwater images of these species.

-

National freshwater aquatic germplasm resource bank & National Marine Aquatic Germplasm Resource Bank: Authoritative Chinese databases and literature collections, which provide more detailed information about native Chinese fish species compared to FishBase. After filtering, they provide detailed descriptions of 335 fish species and 2,975 HD underwater images.

-

Public image datasets: Additional underwater fish image data are collected and organized from FishNet, Fish4Knowledge, and UDF2022 datasets, aligned using species’ scientific names as identifiers.

-

Chinese Fish Fauna literature: The most comprehensive repository of fish species in China, providing detailed taxonomic status, morphological descriptions, and ecological habits of Chinese native fish species, complementing the textual data from FishBase.

-

Self-constructed image dataset: Underwater activity videos of specific species are recorded using self-installed underwater cameras in artificial aquaculture environments. A small number of underwater fish images are then extracted through frame sampling.

After data deduplication and organization, and ensuring proper alignment between textual knowledge and image data, the final dataset comprises 1,418 species of bony fish, 112,763 high-quality phenotypic images, and 27,942 species descriptions. In Table1, the abbreviations are as follows: Total Img – total raw images; Sp. Count – number of species in the dataset; Sp. Descr – species with valid phenotypic descriptions for knowledge graph construction; Phen. Triplets – number of phenotypic knowledge triplets; Dedup. Sp. – number of unique species after deduplication; Filt. Img – number of filtered valid images aligned with knowledge graph entries; Filt. Triplets – number of filtered valid phenotypic triplets after deduplication.

Construction and training of the Fish Multimodal Knowledge Graph (FM-KG)

The construction and training of the Fish Multimodal Knowledge Graph (FM-KG) aims to organize heterogeneous fish-related data into a hierarchical knowledge structure, learn vector representations of entities and relations, and provide semantic priors for downstream tasks such as species classification and taxonomy-aware inference. The FM-KG is constructed following a hierarchical biological taxonomy, where entities are organized from high-level categories (Kingdom–Phylum–Class–Order–Family–Genus) down to the leaf nodes representing individual Species. Each Species entity is enriched with multiple types of attribute information, including morphological features, textual descriptions, and visual exemplars. The core entity and relation types are defined as follows:

-

Entity types (Entities):

-

TaxonomicLevel: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species (hierarchical entities; leaf nodes are Species)

-

Attribute nodes:

-

* MorphologicalFeature (e.g., fins, scales, colors, patterns)

-

* Description (textual information)

-

* Image (visual exemplar)

-

GeographicLocation

-

Habitat

-

Relation types (Relations):

-

is_a: taxonomic relation, e.g., “Cyprinidae is_a Order Cypriniformes”

-

has_part: part-whole relation, e.g., “Carp has_part dorsal fin”

-

has_attribute: linking Species to attribute nodes, e.g.,

-

* “Carp has_attribute dorsal fin (MorphologicalFeature)”

-

* “Carp has_attribute textual description (Description)”

-

lives_in: habitat relation, e.g., “Carp lives_in freshwater”

-

distributed_in: geographical distribution relation, e.g., “Carp distributed_in East Asia”

-

has_visual_exemplar: linking Species to Image entities

The main steps of FM-KG construction include entity alignment, relation extraction, and knowledge graph embedding, which together enable the integration of multimodal information and facilitate semantic reasoning.The overall workflow of FM-KG construction and training is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Entity alignment

Since data originate from heterogeneous sources (e.g., the FishBase English name “Common Carp” and the Chinese Fish Fauna name “Liyu” referring to the same species), inconsistencies in entity naming exist across knowledge bases. To address this, we adopt an alignment method that integrates both semantic and structural information, linking entities that refer to the same real-world object38. The alignment process involves four steps:

-

Multimodal feature representation: For each entity, we extract names, textual descriptions, attribute values, and associated images. Text is encoded using BERT-base-Chinese, while images are encoded with ResNet-50.

-

Neighbor screening and subgraph construction: Candidate neighboring entities in another knowledge base are selected using string similarity of names (e.g., Jaro–Winkler distance) and key attribute matching (e.g., scientific names). Two knowledge subgraphs are then constructed, each centered on the target entity and its candidate neighbors.

-

Graph Attention Network (GAT) interaction: A GAT model is applied to both subgraphs for embedding learning. By aggregating information from neighboring nodes, GAT captures local structural context. Multiple rounds of cross-graph interaction are performed to allow information flow and enhance alignment.

-

Alignment decision: The final alignment is determined by computing the Euclidean distance between the embeddings of the two central entities in the shared vector space, followed by iterative optimization under a co-training framework.

Relation Extraction

Relation extraction is performed under a joint extraction framework that simultaneously identifies entities and their relations, thereby automatically generating new relation triples from unstructured text descriptions37. The process includes:

-

Data annotation: A total of 4,000 morphological description texts are randomly sampled, and 12 categories of relations are manually annotated, resulting in 18,573 triples used as seed corpus for model training.

-

Model design: The model employs BERT as the encoder to obtain deep semantic representations of text. On top of BERT, two parallel decoders are built: (i) a Conditional Random Field (CRF) layer for sequence labeling, serving as a Named Entity Recognition (NER) module; and (ii) an attention-based classification layer to determine the relation type between identified entity pairs.

-

Multimodal enhancement: Visual information is leveraged to support relation extraction. When a textual description mentions a morphological feature, associated representative images are retrieved, and their visual features are extracted. A gated fusion mechanism integrates visual features into textual representations, thereby improving the model’s ability to understand and classify visually related relations such as “color” and “shape.”

Knowledge graph embedding

The constructed Fish Multimodal Knowledge Graph (FM-KG) is a large-scale, graph-structured dataset encompassing hierarchical taxonomic entities, morphological attributes, textual descriptions, and visual exemplars. To facilitate its integration with neural network models, a multimodal knowledge graph embedding approach based on a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) is employed39. This approach jointly embeds entities and relations into a shared low-dimensional vector space, while simultaneously incorporating textual and visual features associated with each entity. The resulting entity embeddings (E_species) and relation embeddings (E_relations) capture richer semantic information and serve as prior knowledge to guide downstream tasks, such as species classification and hierarchical inference.

Classifier training

In the classifier training stage, the focus is on guiding visual feature extraction using semantic priors derived from the Fish Multimodal Knowledge Graph (FM-KG). Input images are first processed by a convolutional neural network (CNN) to generate multi-level feature maps capturing local edges, texture patterns, and overall morphological structures. Underwater conditions, such as light attenuation, turbidity, and background clutter, often introduce noise that can degrade feature quality. To mitigate this, semantic embeddings of species and their relations obtained from the FM-KG are incorporated to provide biologically meaningful guidance, as shown in Fig. 3.

The core mechanism for integrating knowledge into visual features is the Knowledge-driven Adaptive Dynamic Modulation Layer (K-ADML). K-ADML dynamically modulates both channel- and spatial-attention distributions in convolutional feature maps based on “species–key-feature” relations extracted from FM-KG. Formally, let \(\textbf{F} \in \mathbb {R}^{C \times H \times W}\) denote the CNN feature map, where C is the number of channels and H, W are the spatial dimensions. The species–key-feature relation matrix \(\textbf{R} \in \mathbb {R}^{S \times K}\), where S is the number of species and K is the number of key morphological features, encodes the importance of each feature for a given species.

For a target species \(s^{*}\), the corresponding feature importance vector \(\textbf{r}_{s^{*}} \in \mathbb {R}^{K}\) is retrieved. A learnable modulation matrix \(\textbf{M} \in \mathbb {R}^{C \times H \times W}\) is constructed as:

where \(\textbf{W}_c \in \mathbb {R}^{C \times K}\) and \(\textbf{W}_s \in \mathbb {R}^{H W \times K}\) are learnable projection matrices for channel and spatial modulation, \(\textbf{1}_{H \times W}\) and \(\textbf{1}_C\) are all-one vectors for broadcasting, and \(\sigma\) is the sigmoid function. The feature map is then modulated by element-wise multiplication:

This operation emphasizes biologically relevant regions such as fin contours, body stripes, and color patterns, while suppressing irrelevant background noise.

Training is performed in an end-to-end manner using a joint loss function:

where \(\mathcal {L}_{\text {cls}}\) is the standard classification loss and \(\mathcal {L}_{\text {sem}}\) is a semantic consistency loss that encourages alignment between the enhanced visual features and the knowledge graph embeddings. Weighting factors \(\lambda _1\) and \(\lambda _2\) balance classification accuracy and semantic alignment, with typical values chosen empirically (e.g., \(\lambda _1 = 1.0\), \(\lambda _2 = 0.5\)), following practices in multimodal image and video learning41.

Through this integration of CNN feature extraction, knowledge-driven modulation, and joint optimization, the classifier learns representations that are both visually discriminative and semantically grounded, achieving robust performance under challenging underwater conditions.

Hierarchical inference for practical application

In the deployment stage, the trained classifier is applied to unlabelled underwater images to perform hierarchical inference according to the biological taxonomy. Initially, feature representations are extracted from input images using a convolutional neural network (CNN). These features are dynamically modulated by the Knowledge-driven Adaptive Dynamic Modulation Layer (K-ADML), which integrates semantic priors derived from the Fish Multimodal Knowledge Graph (FM-KG). This modulation highlights biologically meaningful regions while suppressing irrelevant background information, ensuring that the subsequent inference is guided by both visual and semantic cues.

The “species–key-feature” relation weights in FM-KG form the semantic foundation of K-ADML. Let \(\textbf{R} \in \mathbb {R}^{S \times K}\) represent the species–feature relation matrix, where each element \(r_{s,k}\) indicates the importance of morphological feature k for species s. For an input image associated with a target species \(s^*\), its corresponding relation vector \(\textbf{r}_{s^*} \in \mathbb {R}^{K}\) is retrieved. Two projection matrices, \(\textbf{W}_c\) and \(\textbf{W}_s\), learn to map this semantic vector into channel and spatial domains, respectively. The attention modulation matrix \(\textbf{M}\) is computed as:

where \(\sigma\) denotes the sigmoid activation that normalizes the modulation strength. The resulting \(\textbf{M}\) acts as a dynamic attention map, reweighting both channels and spatial positions in the CNN feature map \(\textbf{F}\) through element-wise multiplication:

This operation injects knowledge-derived feature importance into the feature extraction process, allowing the network to emphasize discriminative biological traits such as fin shape, color pattern, and scale texture.

Hierarchical inference then proceeds in a top-down manner, traversing the taxonomic hierarchy (Class \(\rightarrow\) Order \(\rightarrow\) Family \(\rightarrow\) Genus \(\rightarrow\) Species). At each level, candidate categories are refined by combining the modulated visual features with semantic embeddings retrieved from FM-KG. Iterative probability refinement is applied to stabilize predictions: the posterior probability distribution over candidate species is repeatedly updated based on semantic consistency and visual alignment until convergence. The category with the highest final probability is selected as the recognition result.

Through the explicit use of relation-weight-driven attention computation in K-ADML, combined with knowledge-guided hierarchical reasoning, the framework achieves robust, interpretable, and biologically consistent predictions under complex underwater conditions.

Experimental

Construction of the experimental image dataset

To ensure the scientific rigor and reproducibility of model training and evaluation, we carefully designed the acquisition, filtering, degradation, and partitioning of image data. Following the data sources described in Section 3.1, raw images are first de-duplicated, metadata-completed, and format-normalized, resulting in a collection of 112,763 high-resolution phenotype images covering 1,418 common freshwater and marine fish species. Based on these data, we further applied manual filtering with the constraints of “complete lateral contour,” “clear fin rays,” and “simple background.” This yielded approximately 80,000 high-quality lateral-view fish images, denoted as \(I_{clean}\), which serve as the ground-truth anchors for all subsequent experiments.

To construct the corresponding low-quality image dataset, we adopted a dual-pathway strategy combining synthetic degradation and real-world acquisition, thereby balancing data controllability with ecological realism.

-

First, in the synthetic pathway, we degraded \(I_{clean}\) using the underwater optical imaging model proposed by McGlamery 11. Specifically, attenuation–scattering kernels are applied under varying depth conditions (0–15 m) and turbidity levels (0–10 NTU). In addition, Poisson–Gaussian mixed noise is introduced to simulate sensor dark current and readout noise. This process generated degraded images \(I_{noisy}\) that are pixel-wise aligned with \(I_{clean}\), forming large-scale denoising training pairs \((I_{noisy}, I_{clean})\).

-

Second, in the real-world acquisition pathway, we incorporated 50,000 naturally degraded underwater images from the public UDF2022 dataset as external supplements. Moreover, we conducted an in-situ data collection campaign using a Hikvision CVA industrial-grade underwater camera at a closed-loop aquaculture base in Fangshan District, Beijing. A continuous 3-hour video sequence is recorded at 25 fps, followed by lens distortion correction, color-temperature normalization, and key-frame extraction, resulting in an additional 20,000 low-quality real-world images. The synthetic and real datasets complement each other in terms of color shift, contrast attenuation, and suspended particle noise distribution, which significantly enhances the generalization capacity of the proposed framework.

-

Finally, the complete dataset is stratified and randomly partitioned into training, validation, and testing subsets with a ratio of 7:1.5:1.5. Stratification is based on a three-dimensional combination of species, water-body type, and imaging device, ensuring statistical consistency across subsets in terms of category distribution and environmental conditions.

Environment and settings

All experiments are implemented under the PyTorch 2.5 framework with CUDA acceleration. On the hardware side, both training and inference are conducted on a high-performance computing node equipped with four NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPUs, each with 24 GB memory. The AdamW optimizer is adopted to alleviate overfitting caused by weight decay. The initial learning rate is set to \(1\times 10^{-4}\) and gradually decayed to \(1\times 10^{-6}\) using a cosine annealing schedule. The batch size is fixed at 64. The models are trained in an end-to-end manner for 200 epochs, corresponding to approximately 125k iterations. The overall loss function is a weighted sum of three components: reconstruction loss, classification loss, and semantic consistency loss, where explicit weighting is used to balance the convergence of different supervisory signals.

Evaluation metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the proposed FM-KG driven semantic enhancement framework for underwater image recognition, we considered three dimensions: image enhancement quality, recognition performance, and the effectiveness of semantic gap bridging.

Image enhancement quality metrics

-

Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR). PSNR measures the ratio between the maximum possible signal power and the power of corrupting noise that affects its fidelity, based on pixel-wise mean squared error (MSE). A higher PSNR indicates lower distortion. It is commonly expressed in logarithmic decibels (dB):

$$\begin{aligned}&M S E=\frac{1}{W \times H \times C} \sum _{i=0}^{W-1} \sum _{j=0}^{N-1} \sum _{k=0}^{C-1}\left[ I_{\text{ clean } }(i, j, k)-I_{\text{ noisy } }(i, j, k)\right] ^2 \\&P S N R=20 \cdot \log 10\left( \frac{2^B-1}{M S E}\right) \end{aligned}$$where W, H, and C denote image width, height, and channels, respectively.

-

Structural Similarity Index (SSIM). SSIM evaluates the structural similarity between two images by jointly considering luminance, contrast, and structural components. The index ranges from 0 to 1, where values closer to 1 indicate better structural preservation:

$$\begin{aligned} \operatorname {SSIM}\left( I_{\text{ clean } }, I_{\text{ noisy } }\right) =\frac{\left( 2 \mu _{\text{ noisy } } \mu _{\text{ clean } }+C_1\right) \left( 2 \sigma _{\text{ noisy } } \sigma _{\text{ clean } }+C_2\right) }{\left( \mu _{\text{ noisy } } ^2+\mu _{\text{ clean } } ^2+C_1\right) \left( \sigma _{\text{ noisy } } ^2+\sigma _{\text{ clean } } ^2+C_2\right) } \end{aligned}$$(6)where \(\mu\) and denote mean intensity, \(\sigma\) denote standard deviation,.

-

Underwater Image Quality Measure (UIQM)42. UIQM is a no-reference metric specifically designed for underwater imagery, integrating human visual perception factors. It fuses three sub-metrics with weighted coefficients: Underwater Image Colorfulness Measure (UICM), Underwater Image Sharpness Measure (UISM), and Underwater Image Contrast Measure (UIConM):

$$\begin{aligned} U I Q M=c_1 \times U I C M+c_2 \times U I S M+c_3 \times U I C o n M \end{aligned}$$(7)where \(c_1, c_2, c_3\) are empirically determined weighting coefficients,\(c_1 = 0.15, c_2 = 0.25, c_3 = 0.6\) .

Recognition performance metrics

-

Accuracy: Measures the proportion of correctly identified items in the test samples. It is calculated as:

$$\begin{aligned} A=\frac{T P+T N}{T P+T N+F P+F N} \end{aligned}$$(8) -

Precision: Evaluates the correctness of the model’s predictions. It is defined as the proportion of predicted items that correctly match the input images:

$$\begin{aligned} P=\frac{TP}{TP+FP} \end{aligned}$$(9) -

Recall: Evaluates the extent of hallucinations in the model’s predictions. It is defined as the proportion of input items that are correctly predicted:

$$\begin{aligned} R=\frac{TP}{TP+FN} \end{aligned}$$(10) -

F1 Score: Combines precision and recall to assess the overall correctness of the model:

$$\begin{aligned} F_1=\frac{2 \times P \times R}{P+R} \end{aligned}$$(11)

Semantic gap bridging metrics

Traditional metrics such as PSNR and SSIM mainly focus on low-level pixel alignment and cannot effectively measure whether the model truly restores high-level semantic information. To evaluate semantic-level matching performance, dedicated metrics need to be designed43. Inspired by recognition performance metrics, two new metrics are proposed for quantifying the effect of semantic gap bridging:

-

Cross-Modal Retrieval Accuracy (CMRA): This metric measures how well the enhanced images semantically match the knowledge. Given a textual feature description from the FM-KG, a text-to-image cross-modal retrieval is performed. Let N be the total number of retrieved items, and \(TP_i\) denote the number of times the correct target image appears at rank i. CMRA is calculated as:

$$\begin{aligned} \operatorname {CMRA}(k)=\frac{\sum _{i=1}^k T P_i}{N} \end{aligned}$$(12)For control models, CMRA can also be computed by obtaining the similarity P between image features and textual description features. N is defined as the number of items with \(P \ge 20\%\), and \(TP_i\) counts the times the correct image appears within the top-i confidence ranks. In this case, the formula simplifies to:

$$\begin{aligned} \operatorname {CMRA}(k)=\frac{\operatorname {Count}\left( P \ge P_k\right) }{\operatorname {Count}(P \ge 0.2)} \end{aligned}$$(13) -

Fine-Grained Attribute Alignment Accuracy (FAAA): This metric evaluates the restoration of key biological features more precisely. A dedicated pre-trained evaluation model set is used to label fine-grained attributes. The pre-trained evaluation model is a small, independent CNN-based classifier called the Alignment Accuracy Exam Model (AAEM), trained to determine whether a specific attribute is present in an image. The AAEM training selects 10 key morphological attributes with clear visual correspondence from FM-KG (e.g., “dorsal fin”, “caudal fin”, “eye”, “stripe pattern”). For each attribute, 1000 representative images are manually annotated with bounding boxes. During testing, for an enhanced image \(I_\text {denoised}\) and a target attribute, the original image \(I_\text {clean}\) and the attribute are input to the AAEM. The following labels are defined:

-

If the attribute exists in \(I_\text {clean}\) and AAEM correctly recognizes it in \(I_\text {clean}\), the image is marked as TC.

-

If the attribute does not exist in \(I_\text {clean}\) and AAEM does not recognize it in \(I_\text {clean}\), the image is marked as NC.

-

For TC images, if AAEM correctly identifies the attribute in \(I_\text {denoised}\), it is counted as TP.

-

For NC images, if AAEM does not recognize the attribute in \(I_\text {denoised}\), it is counted as TN.

FAAA is then calculated as:

$$\begin{aligned} F A A A=\frac{T P+T N}{(T C+N C) \times c} \end{aligned}$$(14)where c is the number of evaluated attributes. Higher FAAA values indicate that the module successfully restores or enhances specific fine-grained biological features, demonstrating better biological feature enhancement performance.

-

Results

In this section, we systematically evaluate the performance of the FM-KG driven image recognition framework through comparative studies and ablation experiments.

Comparative experiments

To systematically validate the effectiveness of the proposed Semantic Enhancement and Recognition Framework for Low-Quality Underwater Fish Images based on a Multimodal Knowledge Graph, comparative experiments are conducted under consistent experimental settings with five representative baseline methods. All baselines share the backbone recognition network EfficientNet-B3 to ensure fairness. The five baseline groups are as follows:

-

Baseline-Raw: Recognition is performed directly on the original low-quality underwater images without any preprocessing. This represents the benchmark recognition performance of EfficientNet-B3.

-

WaterNet + E-B3: Images are enhanced using the WaterNet network, which directly estimates physical parameters for underwater image restoration12, followed by recognition with EfficientNet-B3. [Added] WaterNet represents a physical model-based enhancement strategy commonly used in underwater image processing.

-

FUNIE-GAN + E-B3: Images are first enhanced using the GAN-based FUNIE-GAN15 as a preprocessing module, and then fed into the recognition network. [Added] FUNIE-GAN exemplifies a GAN-based learning approach for underwater image enhancement, capturing complex visual features adaptively.

-

PRIDNet + E-B3: The fully convolutional denoising network PRIDNet, designed for underwater scenarios13, is applied to denoise the input images, followed by recognition. [Added] PRIDNet applies a fully convolutional denoising strategy, targeting noise removal and feature preservation in underwater imagery.

-

AquaYOLO (2025)44: The recently proposed AquaYOLO model is included as a state-of-the-art benchmark. It introduces CSP layers, enhanced convolutions, and multi-scale fusion mechanisms to strengthen feature extraction and object localization in complex aquatic environments. [Added] AquaYOLO is developed specifically for aquaculture monitoring, addressing challenges such as variable lighting, water clarity, and dynamic backgrounds. Evaluated on the DePondFi dataset (8,150 pond images with 50,000 annotations), AquaYOLO achieved strong detection performance (precision 0.889, recall 0.848, mAP@50 0.909), demonstrating its effectiveness as an accurate and affordable fish detection system for small-scale aquaculture.

These baseline methods are selected as classic and representative deep learning approaches in underwater image enhancement and recognition, covering different paradigms (physical model-based, GAN-based, fully convolutional denoising, and detection-oriented fusion networks) while using a consistent recognition backbone (EfficientNet-B3) to ensure fair comparison.

Image enhancement quality evaluation experiment

The image enhancement quality evaluation experiment compares the proposed SGDM module with several baseline enhancement and denoising networks. The performance of image enhancement is measured using PSNR and SSIM metrics, which quantify pixel-level fidelity, and the UIQM metric, which evaluates the overall visual quality of underwater images in terms of colorfulness, sharpness, and contrast. Under consistent experimental settings, the results are summarized in Table 2.

As shown in Table 2, the proposed SGDM module achieves PSNR and SSIM scores comparable to the specialized denoising network PRIDNet, indicating that it effectively preserves low-level image details during denoising. WaterNet and FUNIE-GAN, by contrast, yield significantly lower PSNR and SSIM, reflecting the difficulty of general-purpose enhancement methods in restoring fine-grained structures under challenging underwater conditions. Beyond pixel-level restoration, SGDM attains the highest UIQM score, suggesting that the enhanced images are not only denoised but also visually more natural, with realistic color and contrast. This improvement is attributable to the semantic guidance provided by the Fish Multimodal Knowledge Graph (FM-KG), which emphasizes biologically meaningful regions such as fins, stripes, and body patterns, thereby preserving key morphological features while suppressing irrelevant noise.

In comparison, although PRIDNet performs well in PSNR and SSIM, it lacks semantic awareness and thus produces slightly less perceptually coherent images, and FUNIE-GAN tends to introduce over-enhancement artifacts. AquaYOLO, as a recent detection-oriented model optimized for aquatic environments, achieves balanced quantitative results with PSNR and SSIM values close to PRIDNet while obtaining a relatively high UIQM score of 3.02. This demonstrates that its multi-scale fusion and enhanced convolutional mechanisms contribute to improved perceptual quality and structural consistency. However, since AquaYOLO is primarily designed for object localization rather than fine-grained enhancement, it falls slightly behind the proposed framework in both pixel fidelity and perceptual naturalness.

Overall, the results demonstrate that integrating structured prior knowledge into the denoising process enables SGDM to achieve a balance between noise suppression, pixel fidelity, and semantic feature preservation, validating the effectiveness of knowledge-guided enhancement for underwater images.

Comparison of fish recognition performance

To evaluate both recognition performance and model efficiency, quantitative metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score are measured, along with the number of parameters and FLOPs for each model. Additionally, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are computed based on five independent runs to assess the robustness of the results.

As shown in Table 3, the proposed framework significantly outperforms all baseline methods across all evaluation metrics. Compared with Baseline-Raw, the accuracy improves by 14.53%, and it still exceeds the sequential “enhance-then-recognize” strategies by approximately 8%. AquaYOLO, as a recent detection-oriented model optimized for aquatic environments, achieves strong recognition performance but remains slightly inferior to the proposed framework due to its focus on object localization rather than fine-grained species discrimination.

The relatively narrow confidence intervals indicate that the reported performance is statistically stable and not sensitive to random initialization or data sampling. In addition to quantitative comparisons, qualitative visualizations including feature maps and attention heatmaps show that Baseline-Raw and WaterNet/FUNIE-GAN often focus on large or irrelevant regions, PRIDNet preserves low-level details but lacks semantic awareness, AquaYOLO highlights object regions effectively, and the proposed framework consistently emphasizes biologically meaningful regions such as fins, stripes, and eyes. These visualizations corroborate the quantitative results, demonstrating that the proposed knowledge-guided framework achieves both high-resolution restoration and precise semantic feature localization.

Comparison of semantic gap quantification metrics

The semantic gap quantification experiment evaluates CMRA using the overall textual feature input, and FAAA using 10 key morphological descriptors corresponding to four body parts (scales, tail, dorsal fin, etc.). The proposed framework is compared with four representative baseline methods under consistent experimental settings. The results are summarized in Table 4.

As shown in Table 4, the proposed framework demonstrates a significant advantage over all baseline methods in both CMRA and FAAA metrics, highlighting its effectiveness in bridging the semantic gap. The high CMRA score indicates that the enhanced images are highly consistent with the textual descriptions of species features, while the elevated FAAA score confirms that key morphological attributes, such as scales, tail, and dorsal fin patterns, are accurately restored at a fine-grained level. AquaYOLO achieves competitive performance due to its strong feature extraction and localization capability, yet its detection-oriented design limits fine-grained semantic alignment compared with the proposed framework. In comparison, baseline methods such as PRIDNet, although able to improve visual quality, lack explicit knowledge guidance, which limits their ability to recover semantically meaningful details. The remarkable performance of the proposed framework is attributed to the integration of the Fish Multimodal Knowledge Graph (FM-KG) with the Knowledge-driven Adaptive Dynamic Modulation Layer (K-ADML), which directs the model to focus on biologically relevant regions and relationships. By leveraging structured prior knowledge, the framework ensures that both low-level visual restoration and high-level semantic alignment are optimized simultaneously, effectively overcoming the limitations of traditional enhancement methods and achieving superior semantic consistency in challenging underwater environments.

To further validate the denoising capability and semantic consistency of the proposed framework, a quantitative comparison experiment was conducted for the Semantically-Guided Denoising Module (SGDM). Representative image samples were manually selected from the UDF2022 dataset, and quantitative evaluation was performed using the FAAA metric to assess the preservation of fine-grained morphological attributes after denoising. This experiment complements the qualitative visual analysis of SGDM and provides a more objective comparison across different denoising approaches. The results confirm that SGDM not only effectively suppresses noise under diverse underwater conditions but also maintains high semantic fidelity by preserving biologically relevant features such as scales, fin contours, and body texture.

As shown in Table 5, the proposed SGDM module substantially outperforms conventional denoising networks on both subsets. The significant improvement in FAAA demonstrates that SGDM not only removes underwater noise effectively but also preserves fine-grained semantic structures such as scale texture, fin edges, and body contour patterns. Compared with PRIDNet, which mainly focuses on low-level noise suppression, SGDM leverages semantic priors from the Fish Multimodal Knowledge Graph (FM-KG) to guide the restoration of biologically meaningful details. The consistent gains across different environmental domains (cold vs. tropical waters) further confirm the robustness and adaptability of the proposed semantically guided denoising design.

Ablation study based on the proposed methodology

To evaluate the contribution of each module in the proposed framework and its effect on fish recognition under different image degradation conditions, we design an ablation study guided by the three-stage methodology: Knowledge Graph Training, Classifier Training, and Hierarchical Inference.

Experimental variants. Three ablated variants are considered:

-

w/o SGDM: The Semantic-Guided Denoising Module is removed. Input images are directly processed for feature extraction and classification, bypassing semantic-aware denoising.

-

w/o K-ADML: SGDM is retained, but the Knowledge-driven Adaptive Dynamic Modulation Layer is removed. Features are passed to a standard classifier without attention modulation guided by the knowledge graph.

-

w/o KG: Both semantic guidance in SGDM and relational guidance in K-ADML are removed, resulting in a purely data-driven denoising-classification pipeline.

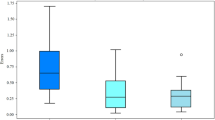

Input images are artificially corrupted with mild-to-moderate noise (SNR \(\ge 20\) dB) and severe noise (SNR \(< 10\) dB). Recognition performance and semantic restoration metrics (CMRA and FAAA) are reported in Tables 6 and 7.

Results under mild-to-moderate noise

Table 6 shows that under mild-to-moderate noise conditions, the full framework achieves the highest accuracy and semantic restoration scores. Removing SGDM or K-ADML leads to noticeable performance drops, particularly in semantic metrics (CMRA and FAAA), demonstrating the importance of semantic-guided denoising and attention modulation. The variant without any knowledge guidance (w/o KG) exhibits the lowest scores among ablated models, although still slightly better than the raw baseline.

Results under severe noise

As seen in Table 7, the performance degradation is more pronounced under severe noise. The full framework still maintains superior recognition and semantic alignment. Removing SGDM significantly decreases all metrics, highlighting its critical role in preserving meaningful features under heavy degradation. The absence of K-ADML primarily affects FAAA, indicating the necessity of knowledge-driven attention for fine-grained morphological feature recovery. Without the knowledge graph guidance (w/o KG), the system loses its semantic reasoning capability, resulting in the lowest scores among all variants.

Qualitative analysis and visualization

This section presents qualitative visualizations to further demonstrate the denoising capability of the SGDM and the enhancement effect of the K-ADML module in practical applications. By comparing images before and after denoising, the reduction of noise and the improvement of attention precision can be clearly observed, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness and practical utility of these modules.

Qualitative denoising comparison of SGDM

Figure 4 shows visual comparisons under conditions of greenish color cast, turbid water, and near-background interference, with ROIs highlighting critical discriminative regions. As shown, SGDM effectively removes color cast and particle noise while preserving key morphological cues (such as body color, texture, fins, and scale edges) and suppressing background noise. In contrast, methods like PRIDNet, lacking knowledge guidance, tend to blur stripes and edge details, and WaterNet may excessively smooth foreground fish features in distant views, leading to lower FAAA scores, consistent with Table 4.

Attention visualization of K-ADML

Figure5 presents attention heatmaps produced by K-ADML. Guided by FM-KG relations (e.g., “Cyprinus carpio has serial dorsal fin” and “Herklotsichthys ovalis has green cycloid scale”), K-ADML accurately focuses attention on the biologically relevant regions of the species. Baseline models without knowledge guidance distribute attention across irrelevant regions: for example, carp dorsal fin features also include pelvic fins and algae-covered rocks, and the cycloid scales of Herklotsichthys ovalis also include ventral scales. The visualizations demonstrate that K-ADML highlights biologically meaningful areas, assigning high weights to exact locations used for species identification (e.g., scales and fins), whereas attention in baseline models is dispersed to less informative regions. These qualitative observations are consistent with the quantitative FAAA improvements reported in Table4.

Computational cost and inference speed

Table 8 presents the computational cost and real-time feasibility of the proposed SGDM + K-ADML framework compared with baseline CNNs. As expected, the addition of SGDM and K-ADML increases the total parameter count from 12.4M to 13.5M and the inference time per image from 18.6 ms to 23.0 ms. Consequently, the achievable frame rate decreases from 53.8 FPS to 43.5 FPS. Despite this increase in computational cost, the model maintains near-real-time processing capability, demonstrating that it is still feasible for deployment on resource-constrained platforms such as underwater robots.

Summary analysis

The ablation study confirms that each component of the three-stage methodology contributes uniquely: SGDM provides robust semantic-aware denoising, K-ADML enhances attention to discriminative biological features, and FM-KG offers structured knowledge priors that guide hierarchical inference. Collectively, these modules enable noise-robust and semantically interpretable underwater fish recognition.

Discussion

Although the proposed FM-KG-driven framework demonstrates superior performance across image quality, recognition accuracy, and semantic alignment metrics, several limitations remain under extreme underwater conditions.

Performance degradation in extreme visual environments

When underwater images suffer from severe turbidity, low illumination, or large-scale occlusion, both the visual features extracted by SGDM and the semantic modulation provided by K-ADML become less reliable. Under such conditions, the model tends to lose fine-grained morphological cues such as fin edges or scale textures, resulting in lower recognition confidence and decreased CMRA and FAAA values. This limitation arises primarily from the restricted generalization ability of the model when low-level signals are heavily distorted beyond the capacity of semantic priors to compensate.

Knowledge graph completeness and adaptability

The Fish Multimodal Knowledge Graph (FM-KG) currently encodes species-level morphological and attribute relationships but lacks environmental and behavioral dimensions, such as habitat, lighting, or motion patterns. Consequently, the model’s inference capability may be biased toward the static characteristics of species and less adaptive to variations caused by environmental changes or camera noise. This limitation highlights the need for dynamic knowledge graph expansion and adaptive learning mechanisms.

Computational complexity and deployment challenges

Although the integration of semantic guidance and dynamic attention modulation improves recognition accuracy, it also introduces additional computational overhead, which may limit real-time deployment in underwater robots or edge devices. Achieving a balance between recognition precision and efficiency remains an open challenge for practical applications.

Conclusions

Fish image recognition in complex underwater environments has long been constrained by the dual bottlenecks of image degradation and semantic information loss. Traditional “content-agnostic” image processing paradigms separate low-level signal restoration from high-level semantic understanding, resulting in irreversible loss of key discriminative features during denoising or reconstruction, and making it difficult to bridge the “semantic gap”.

The proposed Semantic Enhancement and Recognition Framework for Low-Quality Underwater Fish Images based on a Multimodal Knowledge Graph leverages structured biological priors as its core, realizing, for the first time, end-to-end knowledge-data collaborative modeling. Specifically, the Semantic-Guided Denoising Module (SGDM) performs intelligent denoising under species-level semantic priors while preserving critical features. The Knowledge-Driven Attention Dynamic Modulation Layer (K-ADML) further utilizes morphological relation triplets from the knowledge graph to dynamically modulate feature maps, successfully restoring fine-grained discriminative features lost due to image degradation and effectively bridging the “semantic gap”. Extensive experiments demonstrate that the proposed framework significantly outperforms existing methods across multiple dimensions, including image quality, recognition accuracy, and semantic restoration metrics such as Cross-Modal Retrieval Accuracy (CMRA) and Fine-Grained Attribute Alignment Accuracy (FAAA).

The core contribution of this study lies in providing a novel “knowledge-and-data” dual-driven solution to the problem of semantic loss caused by signal degradation in computer vision. It demonstrates the great potential of combining high-level abstract knowledge with low-level pixel processing, laying the foundation for constructing efficient and precise automated intelligent aquaculture systems.

Future directions for extension and exploration include:

-

Dynamic expansion and updating of the knowledge graph: Investigating incremental learning methods to enable FM-KG to automatically learn and augment knowledge from new data, achieving self-evolution.

-

Video analysis and behavior recognition: Extending the current single-frame approach to underwater video streams, leveraging knowledge of fish behavioral patterns in the knowledge graph for more complex behavior analysis and recognition.

-

Cross-species knowledge transfer: Exploring how phylogenetic relationships and similarities among species in FM-KG can facilitate knowledge transfer from data-rich species to data-scarce endangered species, supporting protective research for rare species.

-

Model lightweighting and edge deployment: Investigating model compression and knowledge distillation techniques for real-time monitoring scenarios, deploying the framework on underwater robots or other edge devices to enable online, in-field intelligent analysis.

In summary, Semantic Enhancement and Recognition Framework for Low-Quality Underwater Fish Images based on a Multimodal Knowledge Graph not only addresses the challenge of semantic detail loss under underwater image degradation, but also provides a reusable methodology and foundation for the emerging paradigm of “knowledge-data collaboration”. As knowledge graphs continue to evolve and their cross-modal capabilities broaden, the framework is poised to reach far beyond decision making in industrial aquaculture. It is expected to have a profound impact on key domains such as marine ecological monitoring, fisheries resource management, and endangered species conservation.

Data availability

The raw dataset supporting the findings of this study is now available and can be accessed through the link: https://freshwater.fishinfo.cn/datasets/FMKG/index.html. The databases which is processed and analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Berman, D., Levy, D., Avidan, S. & Treibitz, T. Underwater single image color restoration using haze-lines and a new quantitative dataset. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 43, 2822–2837. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2020.2977624 (2021).

Chen, W., Rahmati, M., Sadhu, V. & Pompili, D. Real-time image enhancement for vision-based autonomous underwater vehicle navigation in murky waters. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Underwater Networks & Systems (WUWNet), 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1145/3366486.3366523 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2020).

Yan, J. et al. Research on multimodal techniques for arc detection in railway systems with limited data. Struct. Health Monit. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475921725133679714759217251336797 (2025).

Wang, X., Jiang, H., Zeng, T. & Dong, Y. An adaptive fused domain-cycling variational generative adversarial network for machine fault diagnosis under data scarcity. Inf. Fusion 103616 (2025).

Yang, H. et al. Csrm-mim: A self-supervised pre-training method for detecting catenary support components in electrified railways. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 11 (4), 10025-10037 (2025).

Hu, K., Weng, C., Zhang, Y., Jin, J. & Xia, Q. An overview of underwater vision enhancement: From traditional methods to recent deep learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10, 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse10020241 (2022).

Yang, H.-H., Huang, K.-C. & Chen, W.-T. Laffnet: A lightweight adaptive feature fusion network for underwater image enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 685–692 (2021).

Jiang, X. et al. An underwater image enhancement method for a preprocessing framework based on generative adversarial network. Sensors 23, 5774. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23135774 (2023).

Zheng, S., Wang, R. & Wang, L. Underwater fish object detection with degraded prior knowledge. Electronics 13, 2346. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13122346 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Acupuncture and tuina knowledge graph with prompt learning. Front. Big Data 7, 1346958. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdata.2024.1346958 (2024).

Ancuti, C.O., Ancuti, C., De Vleeschouwer, C., Neumann, L. & Garcia, R. Color transfer for underwater dehazing and depth estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), 695–699 (2017).

Li, C. et al. An underwater image enhancement benchmark dataset and beyond. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 29, 4376–4389. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2019.2955241 (2020).

Kasat, A., Rathod, T. & Ingle, M. Pridnet based image denoising for underwater images. International Journal of Recent Innovations in Trends and Computation and Communication 11, 2752–2759, https://doi.org/10.17762/ijritcc.v11i9.9362 (2023).

Zhu, J.-Y., Park, T., Isola, P. & Efros, A. A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2223–2232 (2017).

Islam, M. J., Xia, Y. & Sattar, J. Fast underwater image enhancement for improved visual perception. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 5, 3227–3234. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2020.2974710 (2020).

Ben Tamou, A., Benzinou, A. & Nasreddine, K. Targeted data augmentation and hierarchical classification with deep learning for fish species identification in underwater images. J. Imaging 8, 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging8080214 (2022).

Waghumbare, A., Dhake, K. & Singh, U. Classification of underwater sea species using convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the PuneCon 2023 IEEE Pune Section International Conference, 1–5 (2023).

Ruan, Z., Wang, Z. & He, Y. Deformablefishnet: A high-precision lightweight target detector for underwater fish identification. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1424619. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1424619 (2024).

Er, M., Chen, J., Zhang, Y. & Gao, W. Research challenges, recent advances, and popular datasets in deep learning-based underwater marine object detection: A review. Sensors 23, 1990. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23041990 (2023).

Fuad, T. R., Ahmed, S. & Ivan, S. Aqua20: A benchmark dataset for underwater species classification under challenging conditions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.17455 (2025).

Saleh, A. et al. A realistic fish-habitat dataset to evaluate algorithms for underwater visual analysis. Sci. Rep. 10, 14671. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71639-x (2020).

Hogan, A. et al. Knowledge graphs. ACM Comput. Surv. 54, 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1145/3447772 (2022).

Wang, Q., Mao, Z., Wang, B. & Guo, L. Knowledge graph embedding: A survey of approaches and applications. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 29, 2724–2743. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2017.2754499 (2017).

Bordes, A., Usunier, N., García-Durán, A., Weston, J. & Yakhnenko, O. Translating embeddings for modeling multi-relational data. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 26 (NIPS 2013), 2787–2795 (2013).

Dettmers, T., Minervini, P., Stenetorp, P. & Riedel, S. Convolutional 2d knowledge graph embeddings. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2018).

Yang, B., Yih, W.-t., He, X., Gao, J. & Deng, L. Embedding entities and relations for learning and inference in knowledge bases. In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 1923–1928 (2015).

Chen, T., Yu, W., Chen, R. & Lin, L. Knowledge-embedded routing network for scene graph generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2019), 6156–6164 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Knowledge-based scene graph generation with visual contextual dependency. Mathematics 10, 2525. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10142525 (2022).

Shi, B., Ji, L., Lu, P., Niu, Z. & Duan, N. Knowledge aware semantic concept expansion for image-text matching. In Proceedings of the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-19), 5182–5189 (2019).

Niu, G., Li, B. & Lin, Y. A survey of task-oriented knowledge graph reasoning: Status, applications, and prospects. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.11012 (2025).

Ji, Z. A decadal survey of zero-shot image classification. Sci. Sin. Inf. 49, 1299–1320. https://doi.org/10.1360/N112018-00312 (2019).

Marino, K., Salakhutdinov, R. & Gupta, A. The more you know: Using knowledge graphs for image classification. CoRR http://arxiv.org/abs/1612.04844 (2016).

Cui, X. et al. Mkgcn: Multi-modal knowledge graph convolutional network for music recommender systems. Electronics 12, 2688. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12122688 (2023).

Chen, Z. et al. Knowledge graphs meet multi-modal learning: A comprehensive survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.05391 (2024).

Chen, M., Tian, Y., Yang, M. & Zaniolo, C. Multilingual knowledge graph embeddings for cross-lingual knowledge alignment. In Proceedings of the 26th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-17), 1511–1517 (2017).

Sun, Z., Hu, W. & Li, C. Cross-lingual entity alignment via joint attribute-preserving embedding. In The Semantic Web – ISWC 2017, vol. 10599 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 272–288 (Springer, 2017).

Chen, Y. et al. A survey on multimodal knowledge graphs: Construction, completion and applications. Mathematics 11, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11081815 (2023).

Zhang, X., Zhang, W. & Wang, H. Cross-language entity alignment based on dual-relation graph and neighbor entity screening. Electronics 12, 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12051211 (2023).

Chen, Z. et al. Rethinking uncertainly missing and ambiguous visual modality in multi-modal entity alignment. In Payne, T. R. et al. (eds.) The Semantic Web – ISWC 2023, 121–139 (Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2023).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI 2015), 234–241 (2015).

Umirzakova, S., Muksimova, S., Mardieva, S., Baxtiyarovich, M.S. & Cho, Y.-I. Mira-cap: Memory-integrated retrieval-augmented captioning for state-of-the-art image and video captioning. Sensors 24, 8013 (2024).

Panetta, K., Gao, C. & Agaian, S. Human-visual-system-inspired underwater image quality measures. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 41, 541–551. https://doi.org/10.1109/JOE.2015.2469915 (2016).

Peng, H., Lu, X.-S., Xia, D. & Xie, X. A novel image restoration solution for cross-resolution person re-identification. Vis. Comput. 41, 1705–1717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00371-024-03471-7 (2025).

Vijayalakshmi, M. & Sasithradevi, A. Aquayolo: Advanced yolo-based fish detection for optimized aquaculture pond monitoring. Sci. Rep. 15, 6151 (2025).

Funding

Research reported in this publication is supported by the CAFS Basic Research Fund (2024A008)

and the Big Data Analysis and Decision Making Team Fund (2020TD85).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FengWei Zhang designed and conducted the experiments while drafting the manuscript; Jing Hu analyzed and discussed the results with FengWei Zhang; YingZe Sun organized funding and prepared data for the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, F., Hu, J. & Sun, Y. Underwater fish image recognition based on knowledge graphs and semi-supervised learning feature enhancement. Sci Rep 15, 45245 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29396-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29396-2