Abstract

To meet the demands of helicopter transmission systems characterized by diverse configurations and high-speed, heavy-load operating conditions, the meshing characteristics of helical face gears integrated non-orthogonal, offset, and profile-shifted were studied. Geometric contact and load contact analysis models suitable for such non-orthogonal, offset, and profile-shifted helical face gears were established. Combined with Blok’s flash temperature formula, a tooth surface flash temperature analysis model was developed. The influences of installation errors, offset distance, profile-shifted coefficient, and helix angle on the meshing characteristics of the tooth surface were analyzed. The results show that among installation errors, the shaft angle error is the most sensitive. As the offset distance increases, the tooth surface contact stress decreases, while the root bending stresses of both gears initially increase and then decrease. When the profile-shifted coefficient increases, the root bending stress of the profile-shifted pinion decreases, whereas that of the INOPS helical face gear increases. Increasing the helix angle reduces both the tooth surface contact stress and the root bending stress of the profile-shifted pinion, but increases the root bending stress of the INOPS helical face gear. The flash temperature exhibits an increasing trend with distance along the meshing line and is significantly affected by the profile-shifted coefficient and the offset distance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Face gears have attracted widespread attention in related research fields due to their outstanding performance. Scholars have conducted in-depth studies on face gear transmission systems, covering multiple aspects such as tooth-surface generation, meshing mechanisms, strength calculation, and dynamic analysis. Litvin and his research team have made significant contributions to face gear transmission technology, including the geometric design issues of straight tooth face gears, emphasizing the crucial effects of gear tooth root undercut and tooth tip sharpening on tooth width. They proposed meshing a pinion with 1 to 3 fewer teeth than the shaper cutter with the face gear, which promotes the transformation of the original line contact mode into a point contact mode. This change effectively improves the load distribution along the tooth surface while maintaining stable meshing performance1,2. Additionally, they suggested enhancing root bending strength by replacing the sharp tip of the shaper cutter with a rounded corner and studied the effect of having a larger pressure angle at the pitch circle on the working tooth flank compared to the non-working flank to improve load capacity3,5. Tan proposed a novel face gear transmission model that uses a conical involute pinion meshing with a face gear, where the shaft angle is not 90 degrees, thus expanding the application range of face gear6,7. Wojnarowski et al. constructed a finite element model of face gear transmission based on Hertz contact strength theory, providing theoretical support for engineering applications8. Barone et al. developed software for 3D modeling and contact analysis of face gears9. Based on this software, Chung et al. established a face gear transmission model and analyzed the influence of assembly errors on tooth surface meshing characteristics10. Kissling et al. analyzed the geometric tooth profile and contact strength of face gears11. Guingand et al. used Design of Experiments (DOE) methods to predict the tooth width of face gears, providing two simple formulas for designing complex face gears12. He et al. carried out in-depth studies on the characteristics of installation errors in face gear transmissions, analyzing the impact of installation errors on transmission performance and exploring methods and strategies to reduce these errors13. Guo Hui et al. studied the bending strength of face gear transmission by contact finite element method, analyzed the stress distribution in the transmission process, discussed the influence of material properties and size parameters, and studied the effective methods to improve the bending strength14. Zhao et al. employed computer simulation technology, using mathematical models and numerical computation methods to solve the meshing trajectory of face gears. Compared with traditional analytical methods, their approach offers higher accuracy and a broader range of applications15. Fang et al. researched the design, manufacturing, and stress process analysis of arc tooth face gears. They established mathematical models for arc tooth face gears and provided tooth surface equations and design parameters. Through comparative analysis, they demonstrated advantages of arc tooth face gears such as high load capacity, high transmission efficiency, and long service life. They also presented manufacturing methods, including principles, steps, and parameters for machining arc tooth face gears. Finally, they developed finite element models for arc tooth face gears and performed both static and dynamic analyses16,17. Saribay et al. elaborated in detail on the geometry and kinematic characteristics of conjugate meshing face gear pairs and analyzed the bending stress during transmission18,19. Ram et al. proposed a face gear optimization design method based on a genetic algorithm, treating face gear design parameters as chromosomes and the load capacity as the fitness function. Through iterative optimization by the genetic algorithm, the design parameters were continuously refined to improve load capacity20.

In terms of optimization and novel design approaches, Peng developed a novel herringbone tooth face gear transmission system without a relief groove and established corresponding tooth surface calculation and contact models21. Subsequently, Peng et al. combined characteristics of face gears and ruled surfaces to propose an unfoldable ruled surface face gear transmission. They elucidated its geometric and kinematic properties, and through mathematical modeling and numerical computation, conducted an in-depth anaysis of the contact performance during the load-bearing process of the unfoldable ruled surface face gear transmission22. Fu et al. designed a non-orthogonal, offset, modified face gear machining method based on a modification grinding wheel. They analyzed the gear’s geometric and contact characteristics and conducted simulation studies on its meshing performance23. Zschippang et al. introduced a semi-analytical method combining Hertz contact theory with finite element compliance analysis to rapidly calculate the load distribution and stress in face gear meshing. They also developed a calculation method to estimate friction losses on the meshing tooth surfaces of face gears, which was experimentally validated for effectiveness under low-speed conditions24,25 Lu et al. addressed the edge contact problem in face gears by proposing a tooth tip rounding and tip relief optimization method. They established a simulation model to analyze the effects on meshing forces and contact stresses, and determined the optimal rounding radius and tip relief angle26. He et al. developed an analytical model for face gear contact and bending stresses based on fundamental parameters, combining Hertzian theory and the 30° tangential method. They derived simplified strength calculation formulas, which were verified by finite element analysis for accuracy27. Lin et al. proposed a non-typical face gear pair for intermittent reciprocating mechanisms, establishing a coupled rigid-flexible motion model for the tooth surface. They analyzed the effects of parameters on tooth root undercutting and tooth tip sharpening, revealing the principle of continuous intermittent contact for this gear type under various parameters28. Zhao et al. developed the theory of meshing and curvature interference boundary lines for orthogonal face gears, revealing the characteristics and intersection rules of these boundaries. They derived a formula for the undercut-free root diameter and provided its estimation method29. Hochrein et al. proposed two methods applicable for calculating contact stresses in face gear transmissions with arbitrary helix angles and offsets, verifying their accuracy and applicability through comparative case studies30. Maeda et al. studied face gears meshing with offset involute helical pinions and proposed a new method based on constant velocity meshing and a straight meshing line, simplifying tooth surface design and avoiding complex calculations; the validation results were consistent with traditional methods31. Shen et al. proposed a precise finite element modeling method for face gear transmission assembly considering the coupling of installation errors. Using discrete tooth surface points and assembly rotation angles, they achieved high-precision modeling and analyzed the load-bearing contact characteristics32. Zhu et al. introduced a method for analyzing tooth root bending stresses during the meshing process of orthogonal face gears. By combining tooth contact analysis (TCA) and load tooth contact analysis (LTCA), the tooth surface load distribution and root stresses were determined, with results consistent with finite element and experimental data, while improving computational efficiency33.

The most important application of face gear transmission lies in the aerospace field, particularly in helicopter transmission systems. Existing research has mainly focused on orthogonal straight-tooth face gears, limiting the scope of applications. Compared with conventional straight face gears, helical face gears have a higher contact ratio and load-carrying capacity, providing smoother meshing and lower noise. To meet the requirements of helicopter transmission systems characterized by compact structures, diverse configurations, and high-speed heavy-load conditions, a helical face gear considering non-orthogonal, offset, and profile-shifted is designed. The design of a non-orthogonal, offset, and profile-shifted helical face gear transmission enables flexible arrangement of power input directions, allowing the construction of power-splitting systems with almost arbitrary input–output angles and configurations, thereby providing diverse and adaptable layout options for overall power transmission system design in the aerospace field. Based on tooth surface contact analysis and load contact analysis methods, axial displacement errors, shaft angle errors, and offset errors occurring during gear assembly are comprehensively considered. Numerical models of TCA and LTCA for integrated non-orthogonal, offset, and profile-shifted (INOPS) helical face gear are established, and a full-tooth flash temperature model is derived to quantitatively analyze the effects of offset distance, profile-shifted coefficients, and helix angle on the gear pair’s geometric contact characteristics, load contact behavior, and flash temperature characteristics. The proposed modeling approach shows broad adaptability and covers various types of helical face gear transmissions involving non-orthogonal, offset, and profile-shifted features, providing a unified research framework for the modeling and analysis of complex gear systems.

The principle of TCA for INOPS helical face gear transmission

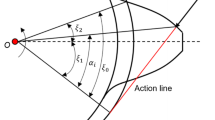

Regarding the tooth surface generation process of the INOPS helical face gear, this paper refers to existing research34 and based on gear meshing principles, utilizes a profile-shifted helical gear shaper cutter to generate the INOPS helical face gear. A full tooth surface model of the INOPS helical face gear is constructed. The processing principle is shown in Fig. 1. The profile-shifted helical gear shaper cutter and the INOPS helical face gear are respectively fixed to movable coordinate systems \({S_S}\) and \({S_{\text{2}}}\); the auxiliary coordinate system \({S_m}\) is fixed on the frame. Wherein, \({\omega _s}\) and \({\omega _2}\) are respectively the angular velocities of the profile-shifted helical gear shaper cutter and the INOPS helical face gear rotating around their respective axes. Non-orthogonal: the intersection angle between pinion and face gear axes is not 90°. Profile-shifted means that the profile-shifted helical gear shaper cutter for machining the INOPS helical face gear and profile-shifted pinion have the same profile-shifted coefficient, and the distance between the cross section of the gear shaper cutter shaft and the gear shaft \({z_2}\) is E, which is called offset distance. Helical gear refers to the helical gear shaper cutter for machining face gear, which has the same spiral angle and the angle \({\gamma _m}\) is the complementary angle of the shaft angle \(\gamma\), providing a theoretical basis for the contact analysis and flash temperature analysis of the INOPS helical face gear pair.

In practical applications of gear transmission systems, due to the comprehensive influence of manufacturing errors, assembly deviations and operating load, installation errors in face gear transmission are inevitable. Therefore, in the analysis of tooth surface contact, it is necessary to incorporate the influence of errors into the coordinate system. Based on this, an engagement coordinate system for the face gear pair is established to accurately describe the meshing characteristics of the gear pair, as shown in Fig. 2. The profile-shifted pinion and the INOPS helical face gear are fixed to coordinate systems \({S_1}\) and \({S_2}\), respectively, with their rotation angles represented by \({\phi _1}\) and \({\phi _2}\). The two tooth surfaces achieve continuous tangential contact within the coordinate system \({S_f}\) fixed to the frame. To systematically account for assembly errors of the gear pair, auxiliary coordinate systems \({S_q}\), \({S_e}\), and \({S_d}\) are introduced to quantify the offset error \(\Delta E\), the shaft angle error \(\Delta \gamma\), and the axial displacement error \(\Delta q\), respectively. Additionally, C is defined as the difference between the radius of the pitch circle of the profile-shifted helical shaper cutter and that of the profile-shifted pinion.

In the coordinate system \({S_f}\), the contact equation between the INOPS helical face gear and the profile-shifted pinion can be described by the following equation:

In the equation, \({{\mathbf{M}}_{{f_1}}}\) and \({{\mathbf{M}}_{{f_2}}}\) represent the homogeneous coordinate transformation matrices from coordinate systems \({S_1}\) to\({S_f}\) and from \({S_2}\) to \({S_f}\), respectively. \({{\mathbf{L}}_{{f_1}}}\) and \({{\mathbf{L}}_{{f_2}}}\) denote the base vector transformation matrices.

Matrix \({{\mathbf{M}}_{{f_1}}}\) can be expressed as:

Matrix \({{\mathbf{M}}_{{f_2}}}\) can be expressed as:

By applying rotational projection transformations on the coordinate axes to Eq. (1), a nonlinear system consisting of 5 equations and 7 unknowns can be obtained. When the rotation angle \({\phi _1}\) of the profile-shifted pinion is selected as the input value and assigned at regular increments, the other unknown quantities can be solved, thus obtaining the contact path of the INOPS helical face gear pair.

The geometric transmission error function of the face gear transmission system is defined as:

In the equation, \({\phi _{10}}\) and \({\phi _{20}}\) represent the initial rotation angles of the two gear surfaces, respectively; \({N_1}\), and \({N_2}\) denote the number of teeth of the two gears, respectively.

The principle of LTCA for INOPS helical face gear transmission

Load contact model of INOPS helical face gear transmission

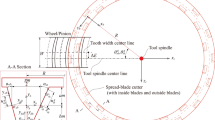

LTCA is an approach that integrates the finite element method and mathematical programming to examine the contact features of gear pairs. By accurately simulating the meshing process of multiple tooth pairs with high precision, this method can precisely describe the contact mechanism between tooth surfaces, effectively determine the contact point locations, load distribution, and transmission error—thus providing a critical basis for the design and optimization of gear systems. Based on the study of tooth contact analysis, a three-dimensional finite element model of the gear pair incorporating installation errors was developed using digital modeling technology, as shown in Fig. 3.

Before establishing the LTCA model for the INOPS helical face gear transmission, several critical preparatory steps must be completed to ensure the model’s accuracy and reliability. Initially, the flexibility coefficients of the operational tooth surface nodes of the INOPS helical face gear pair are computed via the finite element method, and the normal flexibility matrix \({\mathbf{F}}\) at the discrete points along the contact line is derived. Second, based on the previous tooth contact analysis results, the initial contact gap vector \({\mathbf{w}}\) between the tooth surfaces of the profile-shifted pinion and INOPS helical face gear is computed. These preparations provide essential data support for further analysis of load distribution, contact stress and transmission error.

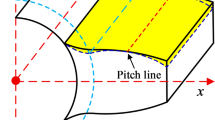

Assuming the profile-shifted pinion is fixed and a load P is applied to the tooth surface, the gear pair undergoes elastic deformation, resulting in a normal displacement Z on the face gear tooth surface. Due to localized elastic deformation, the original point contact area transitions into a surface contact mode. If the lateral width of the instantaneous contact ellipse is neglected, the contact can be simplified to a line contact along the major axis of the ellipse to facilitate the contact analysis calculations. As shown in Fig. 4, in the load analysis model of the INOPS helical face gear pair, it is assumed that tooth pairs I and II may enter the meshing state simultaneously. The contact curve illustrates the characteristics of the tooth surface in the normal section along the major axis of the contact ellipse. Point i represents the current instantaneous contact location, i.e., the center of the contact ellipse, while point j denotes several discrete measurement nodes selected along the major axis direction. The deformation coordination equation after displacement can then be defined as:

In the equation, \({{\mathbf{p}}_k}={[{p_1},{p_2},...,{p_{2n}}]^{\text{T}}}\) represents the normal contact load distributed at each discrete measuring point along the principal axis of the contact ellipse; \({{\mathbf{d}}_k}={[{d_1},{d_2},...,{d_{2n}}]^{\text{T}}}\) represents the normal gap at the corresponding location formed due to elastic deformation of the tooth surface under external loading; \({{\mathbf{Z}}_k}=Z{[1,1,...,1]^{\text{T}}}\) indicates the normal elastic displacement of the gear teeth.

In the principal direction, the normal contact loads \({p_{j\text{I}}}\) and \({p_{j\text{II} }}{\text{ }}(j=1,2, \ldots ,n)\) at the discrete points of the two tooth pairs must satisfy the following static equilibrium equation:

The non-embedding condition to be satisfied when the gear teeth are in contact is:

Based on the above analysis, the mathematical formulations of the mathematical programming model for the load-bearing contact problem of the INOPS helical face gear transmission are expressed as:

This nonlinear programming model includes known variables \({\mathbf{F}}\), P, and \({\mathbf{w}}\), and unknown variables \({\mathbf{p}}\), \({\mathbf{d}}\), and \({\mathbf{Z}}\). Here, \({X_j}{\text{ }}(j=1,2,...,2n+1)\) is an artificial auxiliary variable, \({\mathbf{X}}={\left[ {{X_1},{X_2}, \ldots ,{X_{2n}}} \right]^{\text{T}}}\), \({\mathbf{e}}\) is a 2n-dimensional unit column vector, and \({p_j} \geqslant 0,{\text{ }}{d_j} \geqslant 0,{\text{ }}{Z_j} \geqslant 0,{X_j} \geqslant 0\) is used to describe the boundary contact constraint conditions.

By solving the nonlinear programming model, the instantaneous normal displacement Z of the gear tooth under load can be obtained. Based on this, the load transmission error generated during the meshing process of the INOPS helical face gear can be further derived, expressed as follows:

In the equation, \({{\mathbf{\omega }}_2}\) denotes the angular velocity vector of the INOPS helical face gear during the meshing process, while \({{\mathbf{R}}_2}\) and \({{\mathbf{n}}_2}\) represent the position vector and the normal vector of the INOPS helical face gear, respectively.

Stress analysis process of INOPS helical face gear transmission

Based on the theory of elasticity, the maximum contact stress \({\sigma _H}\) at the center of the contact ellipse in the load-bearing contact of the INOPS helical face gear can be calculated by the following equations:

In the equation, \(a^{\prime}\) and \(b^{\prime}\) represent the lengths of the major and minor semi-axes of the contact ellipse; material parameters \({\mu _1}\) and \({\mu _2}\) denote the Poisson’s ratios of the gear pair; \({E_1}\) and \({E_2}\) are their respective elastic moduli; \(A^{\prime}\) and \(B^{\prime}\) are geometric parameters at the contact point; \({k_{11}}\), \({k_{12}}\), \({k_{21}}\) and \({k_{22}}\) represent the principal curvatures of the two gear tooth surfaces at the contact point; \(\sigma\) is the angle between the principal curvature directions; \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are correction coefficients, whose values can be obtained by interpolation from the parameter table \(\theta ={\cos ^{ - 1}}({{{B^\prime }} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{B^\prime }} {{A^\prime }}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{A^\prime }}})\).

To achieve high-precision stress analysis in the root region of the face gear pair, an improved stress solution method integrating finite element response and interpolation calculation, proposed by Fang et al.17, is employed. The procedure includes: first, applying a standard normal load at the working tooth surface nodes under finite element discretization to obtain the stress influence matrix of the tooth surface mesh; then, using a two-dimensional interpolation algorithm to perform stress mapping at discrete points within the region, forming the stress influence matrix of discrete points along the contact line; next, combining with Eq. (8) to solve for the load distribution, resulting in the load distribution matrix; subsequently, deriving the root bending stress process matrix through the stress superposition mechanism; and finally, introducing the Fourth Strength Theory to equivalently correct the six stress components within each element.

The principle of full tooth surface flash temperature analysis for INOPS helical face gear transmission

Full tooth surface flash temperature analysis model

Based on the Blok flash temperature formula specified in the ISO standard35, for face gear transmissions with strip-shaped Hertzian contact zones, a specific tooth surface flash temperature formula can be applied to characterize the temperature increased in the gear tooth contact region. The computational expression for the tooth surface flash temperature is given as:

In the equation, W represents the load distribution density in the contact area; \({\mu _m}\) denotes the average friction coefficient at the contact point of the gear pair; \({v_{t1}}\) and \({v_{t2}}\) are the tangential velocities of the profile-shifted pinion and the INOPS helical face gear along the contact line, respectively; \({B_1}\) and \({B_2}\) are the thermal contact conductance coefficients at the contact interface for the profile-shifted pinion and the INOPS helical face gear, respectively; \({\gamma _1}\) and \({\gamma _2}\) represent the angles between the line velocity directions of the two gears (for simplification in analysis, the values \({\gamma _1}={\gamma _2}=0.5\pi\) are used); and \(b^{\prime}\) is the length of the short axis of the contact ellipse.

To perform flash temperature analysis of the instantaneous contact region of the INOPS helical face gear in the reference frame \({S_f}\), a segmented discretization strategy is applied along the major axis of the contact ellipse to spatially discretize the gear tooth surface. The procedural steps are illustrated in Fig. 5.

The instantaneous contact point \({M^i}\) on the gear tooth surfaces of the two gears is determined by the position vector \({{\mathbf{r}}_M}\) and the unit normal vector \({{\mathbf{n}}_M}\). \({M^{ij}}\) denotes the j-th discrete point along the i segment of the major axis, while the actual contact points after elastic deformation are represented by \(M_{1}^{{ij}}\) and \(M_{2}^{{ij}}\), respectively. Accordingly, the expression for the tooth surface flash temperature \(\theta _{f}^{{ij}}\) of the INOPS helical face gear at the discrete point \({M^{ij}}\) is given by:

In the equation, \({W^{ij}}\) represents the load distribution density at the discrete contact point; \(\mu _{m}^{{ij}}\) denotes the average friction coefficient at that point; \(\gamma _{1}^{{ji}}\) and \(\gamma _{2}^{{ji}}\) indicate the angles between the line velocity directions of the profile-shifted pinion and the INOPS helical face gear at the discrete point, respectively; \(v_{{t1}}^{{ij}}\) and \(v_{{t2}}^{{ji}}\) represent the tangential velocities of the corresponding gears; and \({(b^{\prime})^i}\) denotes the length of the minor semi-axis of the i-th contact ellipse.

Determination of relevant parameters for full tooth surface flash temperature calculation

In the process of solving Eq. (15), the calculation methods for each parameter are provided sequentially. The parameter \({(b^{\prime})^i}\) can be calculated according to Eq. (12); the thermal contact coefficients B1 and B2 can be determined based on Eqs. (A.11) and (A.12) in the ISO standard; meanwhile, the average friction coefficient \(\mu _{m}^{{ij}}\) must be determined according to Eq. (22) of the ISO standard. However, before applying this formula, the equivalent radius of curvature \(\rho _{{red}}^{{ij}}\) of the gear pair must be clearly defined. Therefore, the following text will specifically elaborate on the method for determining the equivalent radius of curvature.

-

(1)

Load density.

In the analysis of load distribution characteristics of gear pairs, for discrete points along the major axis of the contact ellipse, if the load borne by the point is defined as \({p^{ij}}\), then the load density \({W^{ij}}\) at that point can be calculated by the following equation:

In the equation, \({L^{i,j}}\) represents the spatial position distribution of the selected discrete measurement points along the major axis of the contact ellipse; n denotes the total number of discrete nodes divided along the i-th contact path direction.

-

(2)

Tangential velocity and the corresponding directional angle.

According to Eq. (1), the spatial position vector \({{\mathbf{r}}_M}\) and the unit normal vector \({{\mathbf{n}}_M}\) of the two meshing tooth surfaces at the contact point \({M^i}\) can be calculated. Therefore, the position vector of the discrete point \({M^{ij}}\) along the major axis of the contact ellipse can be expressed as:

Starting from the discrete measurement point \({M^{ij}}\), a line is drawn along the unit normal vector \({{\mathbf{n}}_M}\), which intersects the profile-shifted pinion and the INOPS helical face gear tooth surfaces at points \(M_{1}^{{ij}}\) and \(M_{2}^{{ij}}\), respectively. The position vector and the unit normal vector at point \(M_{1}^{{ij}}\) are expressed as:

The position vector and the unit normal vector at point \(M_{2}^{{ij}}\) are expressed as:

The absolute velocity vectors of the profile-shifted pinion tooth surface \({\Sigma _1}\) at point \(M_{1}^{{ij}}\) and the absolute velocity vector of the INOPS helical face gear tooth surface \({\Sigma _2}\) at point \(M_{2}^{{ij}}\) are respectively given by:

The corresponding tangential velocity vectors are expressed as:

The relative sliding velocity between the profile-shifted pinion and the INOPS helical face gear is expressed as:

At the discrete point \({M^{ij}}\), the angle between the tangential velocity vectors of the profile-shifted pinion and the INOPS helical face gear is denoted by the parameter \(\gamma _{k}^{{ij}}(k=1,2)\) and defined as:

-

(3)

Composite curvature radius.

During the meshing process of the two gears, the curvature values along the major axis of the contact ellipse are significantly smaller than those in other directions and are usually simplified. Therefore, the calculation of the composite curvature only considers the curvature variation along the minor axis. According to Eqs. (18) to (21), the position vectors of discrete points along the major axis of the contact ellipse are first determined, which precisely describe the spatial locations of these discrete points. Based on the previously mentioned principal curvature relationships of the mating surfaces, the curvature radius parameters at the discrete positions along the major axis of the contact ellipse for the profile-shifted pinion and the INOPS helical face gear are derived, denoted as \(\rho _{1}^{{ij}}\) and \(\rho _{2}^{{ij}}\), respectively. Their calculation expressions are as follows:

The composite radius of curvature at the discrete points along the major axis of the contact ellipse is expressed as:

Calculation examples and analysis

On the basis of the above theoretical formulas, a simulation analysis flowchart illustrated in Fig. 6 was developed to analyze the full-face contact features of the INOPS helical face gear pair, and the simulation analysis is conducted using the design parameters listed in Table 1 as input.

Geometric contact characteristic analysis

Based on the basic parameters in Table 1, geometric contact analysis of the INOPS helical face gear transmission was conducted under the condition of limiting tooth width. By projecting the tooth surface and its contact path along the axial direction onto the transverse section plane, the contact pattern is illustrated in Fig. 7, and the geometric transmission error is obtained as shown in Fig. 8.

As seen in Fig. 7, the contact trajectory extends along the tooth height direction and forms a clear inclination angle with the INOPS helical face gear root line. The curvature radius of the trajectory is close to zero, thus it can be approximated as a straight line. As the gear pair continues to mesh, the contact point gradually shifts from the tooth tip region toward the tooth root region. Moreover, since the number of cutter teeth exceeds that of the profile-shifted pinion by 2–3 teeth, the INOPS helical face gear pair is characterized by non-conjugate tooth surfaces. Nevertheless, the geometric transmission error of the tooth surfaces remains zero, suggesting that the instantaneous transmission ratio remains stable during the entire meshing process.

The influence of the shaft angle on the minimum inner radius and maximum outer radius of the INOPS helical face gear is significantly greater than that of the offset distance, profile-shifted coefficient, and helix angle34, Fig. 9 illustrates that the shaft angle has a crucial influence on the minimum inner radius and maximum outer radius of the INOPS helical face gear. When analyzing the influence of shaft angle variation alone, all other parameters must remain constant. However, in practice, changes to the shaft angle necessitate corresponding adjustments to the INOPS helical face gear’s inner and outer radii to ensure normal meshing of the gear pair. Even when the shaft angle remains fixed, the contact characteristics can vary significantly if the INOPS helical face gears have different inner and outer radii, as shown in Fig. 10. Therefore, subsequent analysis will focus solely on the effects of offset distance, profile-shifted coefficient, and helix angle on meshing performance.

Influence of internal and external radius on geometric contact pattern (\(\gamma =73{\text{ }}^\circ ,x=0.1,\beta =6{\text{ }}^\circ\)): (a) \({L_{\text{1}}}=247{\text{ mm}},{L_{\text{2}}}=267{\text{ mm}}\), (b) \({L_1}=249{\text{ mm}},{L_2}=269{\text{ mm}}\), (c) \({L_1}=251{\text{ mm}},{L_2}=271{\text{ mm}}\)

Based on this, the present study further focuses on analyzing the effects of offset distance, profile-shifted coefficient, and helix angle on the shape and distribution of the contact pattern, as illustrated in Figs. 11, 12 and 13. Based on the preceding analysis, the permissible ranges for the shaft angle and the inner and outer diameters are established as follows: \(\gamma =83{\text{ }}^\circ\), \({L_1}=235{\text{ mm}}\), \({L_2}=255{\text{ mm}}\), \(B=20{\text{ mm}}\).

Influence of the offset distance on the geometric contact pattern: Increasing the offset distance causes the contact pattern of the INOPS helical face gear pair to move toward the inner end, with the contact path becoming more perpendicular to the tooth root. A greater offset distance reduces the contact area, which can lower the load-carrying capacity. However, when the offset distance reaches 20 mm, the number of contact points remains at 14, suggesting that the offset distance has minimal influence on the contact ratio.

Influence of the profile-shifted coefficient on the geometric contact pattern: The geometric contact pattern shows little sensitivity to the profile-shifted coefficient, with its shape and location on the tooth surface remaining almost unchanged. With positive modification, the INOPS helical face gear pair has 14 meshing positions per cycle, while negative modification results in 15 positions, indicating that a negative profile-shifted coefficient can effectively increase the contact ratio of the gear pair.

Influence of the helix angle on the geometric contact pattern: As the helix angle increases, the geometric contact area of the face gear moves toward the outer edge of the tooth surface, and the contact path becomes more steeply inclined. The INOPS helical face gear pair maintains 14 meshing positions per cycle, suggesting that a larger helix angle can improve the contact ratio of the INOPS helical face gear pair.

During the assembly phase of the gear pair, installation errors directly affect the tooth surface contact pattern and its spatial positioning, while abnormal contact pattern shapes can reveal potential types of errors. Taking the INOPS helical face gear pair from Table 1 as the analysis subject, a TCA meshing simulation model is established incorporating axial displacement error, profile-shifted pinion offset error, and shaft angle error. The simulation results are presented in Fig. 14.

Influence of installation errors on geometric contact pattern (\(\beta =6{\text{ }}^\circ ,x=0.1,E= - 10{\text{ mm}}\)): (a) \(\Delta q=0.1{\text{ mm}}\), (b) \(\Delta E=0.3{\text{ mm}}\), (c) \(\Delta \gamma =0.03{\text{ }}^\circ\), (d) \(\Delta q={\text{-}}0.1{\text{ mm}}\), (e) \(\Delta q=-0.1{\text{ mm}},\Delta \gamma =0.03{\text{ }}^\circ\), (f) No installation errors.

Figure 14 shows that when a single positive installation error is present in the gear system—such as offset error \(\Delta E\), shaft angle error \(\Delta \gamma\), or axial displacement error \(\Delta q\), the geometric contact region generally shifts toward the outer edge of the gear tooth surface. When multiple errors occur simultaneously, proper adjustment of assembly parameters can greatly improve the distribution of contact patterns, as illustrated in Fig. 14e. Notably, for the INOPS helical face gear pair designed under ideal conditions, even with geometric deviations during assembly, the basic meshing motion path remains unchanged and the geometric transmission error stays at zero, ensuring a constant instantaneous transmission ratio throughout the meshing cycle.

Load contact characteristics analysis

Figure 15 shows the LTCA simulation results of the INOPS helical face gear pair, based on the design parameters in Table 1. The material properties are defined with a Young’s modulus of 206 GPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3, and a load torque of 400 N·m is applied to the INOPS helical face gear. The results show a periodic alternation between single-tooth and double-tooth engagement, causing noticeable jumps in the load distribution coefficient, contact stress, and root bending stress during the transition between meshing phases. The maximum fluctuation of the load transmission error reaches 7.00″. When the load distribution coefficient is less than 1, the system enters the double-tooth contact region. Stress distribution curves reveal that during double-tooth contact, both contact pressure and peak root bending stress are relatively low. In contrast, during single-tooth load phases, the maximum contact stress reaches 1349.36 MPa, with root bending stresses of 73.72 MPa for the INOPS helical face gear and 50.75 MPa for the profile-shifted pinion. Additionally, at the beginning of meshing, the unit load density along the main axis of the first contact ellipse reaches 418.96 N/mm, attributed to the base pitch difference between the loaded gears.

Figures 16, 17 and 18 systematically present the response trends of the peak contact stress and peak root bending stress of the INOPS helical face gear pair under varying conditions of offset distance, profile-shifted coefficient, and helix angle. The findings suggest that all the above parameters have a notable influence on the maximum stress of the INOPS helical face gear pair.

The analysis results from Fig. 16 indicate that as the offset distance gradually increases, the peak contact stress on the tooth surface initially decreases slightly, then shows a marked declining trend, followed by a slow reduction. At the same time, the peak bending stresses at the tooth roots of the INOPS helical face gear and profile-shifted pinion show a trend of rising first and then falling. Therefore, in order to effectively improve the bending fatigue strength of the gear tooth root and the contact fatigue strength of the tooth surface, we recommend increasing the offset distance.

The analysis results from Fig. 17 shows that with the gradual increase of the profile-shifted coefficient, the contact stress on the tooth surface and the peak bending stress at the tooth root of the profile-shifted pinion tend to decrease, while the peak bending stress at the tooth root of the INOPS helical face gear increases correspondingly. This indicates that applying negative modification helps enhance the bending fatigue resistance of the INOPS helical face gear root, whereas positive modification is more beneficial for improving the fatigue strength of the profile-shifted pinion root and the meshing tooth surface. Therefore, in order to balance the strength of INOPS helical face gear and profile-shifted pinion, positive profile-shifted coefficients should be given priority in designing the profile-shifted of INOPS helical face gear pair.

As can be seen from the analysis results in Fig. 18, with the increase of helix angle, the peak of contact stress on the tooth surface and the peak of bending stress at the small root show a decreasing trend, while the peak of bending stress at the large root gradually increases. This trend shows that properly reducing the helix angle is beneficial to improve the bending fatigue resistance of the tooth root of INOPS helical face gear; conversely, increasing the helix angle better enhances the fatigue strength of the profile-shifted pinion root and the contact region. Therefore, in order to balance the force between the INOPS helical face gear and profile-shifted pinion, increasing the screw angle should be given priority.

Full tooth surface flash temperature characteristics analysis

In the simulation of thermal characteristics for high-speed aerospace gear systems, considering that helicopter main reducers often operate under high-frequency and high-speed conditions, this study selects an input speed of 20,000 r/min for the profile-shifted pinion to closely approximate practical working conditions. To more accurately reflect the meshing thermal effects, the simulation sets the INOPS helical face gear pair components with a surface roughness of 0.8 μm, a thermal contact conductance of 13.8 N/(mm s0.5 °C), and an operating temperature of 100 °C. The lubricant’s dynamic viscosity is set to 10 mPa s. Other parameters are kept consistent with the standard example provided in Fig. 16. The resulting flash temperature distribution on the tooth surface is shown in Fig. 19.

Simulation results of full-face flash temperature characteristics for INOPS helical face gear transmission: (a) Full-face relative sliding velocity distribution; (b) Full-face average friction coefficient distribution; (c) Mean flash temperature at discrete points; (d) Full-face flash temperature distribution.

Figure 19 shows that the region near the pitch line (the 7th contact ellipse major axis) exhibits the lowest sliding velocity, which is nearly zero. The sliding velocity increases progressively with distance from the pitch line. At the 14th contact path on the ingress side, farthest from the pitch line, the sliding velocity reaches its maximum of 29.04 m/s. The friction coefficient maintains a relatively stable distribution across the contact strips, with a maximum value of 0.071 also occurring along the 14th contact trajectory. Temperature rise near the pitch line is close to 0 °C, while flash temperature increases in regions farther from the pitch line. Notably, at the major axes of the 1st and 14th contact trajectories—corresponding respectively to the tooth root and tooth tip areas—flash temperature spikes are observed. The peak flash temperature reaches 164.25 °C at the 14th contact trajectory, indicating that this location is the most likely site for gear tooth surface scuffing failure.

As shown in Figs. 20, 21 and 22, the offset distance, profile-shifted coefficient, and helix angle significantly affect the peak flash temperature on the INOPS helical face gear tooth surface. The peak flash temperature increases continuously with the offset distance. The profile-shifted coefficient first decreases and then increases the flash temperature. Increasing the helix angle effectively suppresses the flash temperature on the tooth surface. In summary, to control the peak flash temperature, it is necessary to reasonably coordinate these three geometric parameters in the design.

Conclusions

Analytical models for TCA, LTCA, and full-face flash temperature were developed for the INOPS helical face gear transmission system. Using these models, comprehensive numerical simulations were carried out to systematically examine the geometric meshing characteristics, load-carrying contact behavior, and full-face flash temperature distribution of the INOPS helical face gear pair. The main findings are as follows:

-

(1)

The introduction of an offset causes the contact pattern to form a certain angle relative to the root of the INOPS helical face gear teeth. As the offset distance increases, the contact area significantly decreases. The profile-shifted coefficient has negligible effect on the geometric contact pattern; its shape and distribution on the tooth surface remain stable, with the contact pattern direction slightly inclined to the tooth root reference plane. With the increase of the helix angle, the geometric contact pattern shifts notably toward the edge of the tooth surface, the trajectory inclination intensifies, and the INOPS helical face gear pair’s contact ratio increases.

-

(2)

Among the three main types of installation errors, the shaft angle error exhibits the lowest system tolerance and exerts the most significant influence on meshing characteristics, thus requiring prioritized precision control during assembly. When a single positive installation deviation occurs, the geometric contact patterns on both sides of the tooth surface shift synchronously toward the outer end of the gear tooth. In the presence of multiple error sources, reasonable adjustment of their combined parameters can effectively improve the distribution pattern of the tooth contact.

-

(3)

In the INOPS helical face gear pair, the peak contact stress and root bending stress are jointly influenced by offset distance, modification amount, and helix angle. With increasing offset distance, the peak stress in the contact region initially decreases gradually and then declines sharply; the root bending stress peaks of the profile-shifted pinion and INOPS helical face gear first increase and then tend to decrease. Therefore, appropriately increasing the offset distance can enhance the system’s contact strength and bending fatigue resistance. Increasing the profile-shifted coefficient and helix angle significantly reduces the profile-shifted pinion’s root bending stress and contact stress peaks, while the INOPS helical face gear’s root bending stress peak gradually increases.

-

(4)

Near the pitch line region, the relative sliding velocity is low, and temperature rise is minimal, remaining close to ambient conditions. Away from this region, the temperature rise becomes pronounced. Moreover, the maximum flash temperature on the tooth surface is sensitive to structural parameters, especially offset distance, profile-shifted coefficient, and helix angle; thus, careful selection of these key parameters during design is essential to control the risk of scuffing failure.

Data availability

Data are contained within the article.

References

Litvin, F. L., Fuentes, A., Zanzi, C., Pontiggia, M. & Handschuh, R. F. Face-gear drive with spur involute pinion: geometry, generation by a worm, stress analysis. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 191 (25–26), 2785–2813. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0045-7825(02)00215-3 (2002).

Litvin, F. L., Fuentes, A., Zanzi, C. & Pontiggia, M. Design, generation, and stress analysis of two versions of geometry of face-gear drives. Mech. Mach. Theory. 37 (10), 1179–1211. https:/doi.org/10.106/S0094-11 (2002).

Litvin, F. L., Egelja, A., Tan, J. & Heath, G. Computerized design, generation and simulation of meshing of orthogonal offset face-gear drive with a spur involute pinion with localized bearing contact. Mech. Mach. Theory. 33 (1–2), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0094-114X(97)00022-0 (1998).

Litvin, F. L., Fuentes, A. & Howkins, M. Design, generation and TCA of new type of asymmetric face-gear drive with modified geometry. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 190 (43–44), 5837–5865. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0045-7825(01)00201-8 (2001).

Litvin, F. L. et al. Design, generation and stress analysis of face-gear drive with helical pinion. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 194 (36–38), 3870–3901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2002.09.006 (2005).

Tan, J. Face gearing with a conical involute pinion: Part 2—The face gear: Meshing with the pinion, tooth geometry and generation. In Proc. ASME 2003 IDETC/CIE, Chicago, IL, USA, Sep. 2–6, 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1115/DETC2003/PTG-48038 (2003).

Tan, J. Face gearing with a conical involute pinion: Part 1—The conical involute gear: Definition, geometry and generation. In Proc. ASME 2002 IDETC/CIE, Montreal, QC, Canada, Sep. 29–Oct. 2, 553–562. https://doi.org/10.1115/DETC2002/MECH-34262 (2002).

Wojnarowski, J. & Onishchenko, V. Tooth wear effects on spur gear dynamics. Mech. Mach. Theory. 38 (2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0094-114X(02)00091-5 (2003).

Barone, S., Borgianni, L. & Forte, P. Evaluation of the effect of misalignment and profile modification in face-gear drive by a finite element meshing simulation. J. Mech. Des. 126 (5), 916–924. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1799844 (2004).

Chung, T. D. & Chang, Y. Y. An investigation of contact path and kinematic error of face-gear drives. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 13 (2), 4. https://doi.org/10.51400/2709-6998.2109 (2005).

Kissling, U. & Beermann, S. Face gears: geometry and strength. Gear Technol. 1 (2), 54–61 (2007).

Guingand, M., Remond, D. & de Vaujany, J. P. Face gear width prediction using the DOE method. J. Mech. Des. 130 (10), 104502. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2965606 (2008).

He, P. & Liu, G. Tooth contact analysis of face-gear meshing. Mech. Sci. Technol. Aeroeng. 1, 92–95 (2008).

Gu, H., Zhao, N., Fang, Z. & Shen, Y. Research on bending strength of face-gear transmission based on contact finite element method. J. Aeroengine Power. 8, 1438–1442. https://doi.org/10.13224/j.cnkijasp.2008.08.006 (2008).

Zhao, N., Ceng, X., Guo, H. & Fang, Z. TCA of face gear drive and a new method for solving tooth contact path. Comput. Simul. 26 (1), 276–279 (2009).

Fang, Z., Cao, X. & Shen, Y. Tooth surface design and manufacture for arcuate tooth trace face-gear. J. Aeroengine Power. 25 (1), 224–227. https://doi.org/10.13224/j.cnkijasp.2010.01.005 (2010).

Fang, Z., Li, J., Peng, X., Cai, X. & Zhang, Z. Analysis of stress process for face gear with arcuate tooth pinion. J. Aeroengine Power. 27 (12), 2814–2820. https://doi.org/10.13224/j.cnkijasp.2012.12.025 (2012).

Saribay, Z. B. Tooth geometry and bending stress analysis of conjugate meshing face-gear pairs. Proc. IMechE, Part C 227(6), 1302–1314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0954406212457644 (2013).

Saribay, B., Bill, R. C., Smith, E. C. & Rao, S. B. Geometry and kinematics of conjugate meshing face-gear pairs. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 62 (3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4050/JAHS.62.032008G (2017).

Ram, G., Ajay, A. & Rajiv, S. Optimization of loaded meshed face gears design using genetic algorithm. J. Energy Technol. Policy. 4 (12), 54–60 (2014).

Peng, X., Li, A. & Guo, W. Face gear drive with double helical pinion and its meshing performance. Mech. Sci. Technol. Aeroeng. 36 (7), 1131–1135. https://doi.org/10.13433/j.cnki.1003-8728.2017.0724 (2017).

Peng, X., Hou, Y., Li, A. & Wang, X. Analysis of bearing contact of developable ruled surface face gear transmission. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. 57 (3), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.7652/xjtub202303008 (2023).

Fu, X., Fang, Z., Cui, Y., Hou, X. & Li, J. Modelling, design and analysis of offset, non-orthogonal and profile-shifted face gear drives. Adv. Mech. Eng. 10 (9), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1687814018798250 (2018).

Zschippang, H. A., Lanz, N., Küçük, K. A., Weikert, S. & Wegener, K. Face-gear drive: assessment of load sharing, transmission characteristics and root stress based on a quasi-static analysis. Mech. Mach. Theory. 151, 103914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2020.103914 (2020).

Zschippang, H. A., Weikert, S. & Wegener, K. Face-gear drive: meshing efficiency assessment. Mech. Mach. Theory. 171, 104765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2022.104765 (2022).

Lu, R., Chen, S., Jiang, P. & Liu, B. Contact performance optimization of face gear based on tooth top structure design. Aeroengine 48 (4), 93–97. https://doi.org/10.13477/j.cnki.aeroengine.2022.04.015 (2022).

He, F., Qian, W., Fu, X. & Peng, X. Simplified calculation of meshing strength of face gear pair. J. Mech. Strength. 45 (5), 1192–1198. https://doi.org/10.16579/j.issn.1001.9669.2023.05.024 (2023).

He, C., Zhang, J. & Lin, C. An analysis of the kinematical characteristics of an eccentric curve-face gear pair with compound motion. Machines 12 (3), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines12030162 (2024).

Zhao, Y. & Lou, H. Two types of boundary line of orthogonal face gear drives. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 45 (4), 764–770. https://doi.org/10.11990/jheu.202210027 (2024).

Hochrein, J. F., Otto, M. & Stahl, K. Face gear drives: nominal contact stress calculation for flank load carrying capacity evaluation. Mech. Mach. Theory. 195, 105573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2024.105573 (2024).

Maeda, N. Research on simplification of face gear tooth surface design. J. Adv. Mech. Des. Syst. Manuf. 18 (1), JAMDSM0006. https://doi.org/10.1299/JAMDSM.2024JAMDSM0006 (2024).

Weng, D., Shen, Y. & Xu, W. Analysis of bearing contact characteristics of face-gear drives with coupling installation errors. J. Mech. Transm. 48 (12), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.16578/j.issn.1004.2539.2024.12.006 (2024).

Zhou, W. et al. Theoretical and experimental research on tooth root bending stress of face gear. Proc. IMechE Part. C. 238 (14), 7172–7188. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544062241228009 (2024).

Fu, X. et al. Tooth surface design of double-pressure-angle helical face gear considering non-orthogonality, offset, and modification. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 39, 1399–1410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-025-0232-3 (2025).

Vullo, V. Scuffing load carrying capacity of cylindrical, bevel and hypoid gears: Integral temperature method. In Gears, Vol. 2: Analysis of Load Carrying Capacity and Strength Design, 383–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38632-0-8 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Research Program supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52265006), Guangxi Science and Technology program (No. AD23026183).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52265006) and the Guangxi Science and Technology Program (No. AD23026183).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.F. and S.L. conceived the article. H.H. and H.X. conducted the literature search. X.F., H.H. and S.Y. drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, X., He, H., Xu, H. et al. Meshing performance analysis of helical face gear drives with integrated non-orthogonal, offset, and profile-shifted. Sci Rep 16, 61 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29441-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29441-0