Abstract

Effective monitoring of marine activities is essential for optimizing the marine operations, ensuring the safety and protecting the marine environment. However, the existing monitoring approaches still have the problems of low intelligence, high cost and poor reliability. This article attempts to employ autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) to develop a ubiquitous monitoring system for marine activities. Particularly, it mainly includes AUVs, human operator, onshore cameras, and wireless communication networks. With the wireless communication networks, the human operator in the control center assigns monitoring tasks to AUVs and onshore cameras. After that, the cameras mounted on AUVs and shore collect the images of surface target (e.g., ship or buoy), such that the target attitudes can be estimated by using deep learning technology. For underwater target (e.g., shipwreck or drowning person), sonars are mounted on AUVs to carry out water depth detection. Finally, experimental results are provided to verify the effectiveness of our system. These results provide evidence that the AUV-assisted monitoring system can improve the reliability and reduce the cost over the manual monitoring system.

Similar content being viewed by others

The oceans cover more than 70% of the Earth’s surface and are vital to global climate regulation, economic activities, and food security1. However, the increasing human activities, such as shipping, fishing, and offshore energy extraction, coupled with climate change, have placed unprecedented pressure on marine ecosystems2,3. For example, there were at least 2400 incidents in maritime ports as reported by the data from 20224. For that reason, the effective monitoring of marine activities is essential to address these challenges, ensuring the sustainable use of ocean resources and the protection of marine biodiversity. Specifically, the key areas of marine activity monitoring include ship tracking, port operations and security, shipwreck detection and recovery, search and rescue operations for drowning persons, and related maritime activities.

Traditionally, the marine monitoring has been carried out through human visual inspections or radar5. However, human visual inspections depend on the experience, skill, and judgment of the inspector, which may lead to potential variability in the results. Besides that, human vision can only detect surface-level problems, and it cannot provide long-term monitoring especially in harsh underwater environment. On the other hand, the radar-based system cannot monitor subsurface conditions, which is expensive to install, maintain and operate. For the aforementioned reasons, the unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are increasingly applied for marine monitoring. Particularly, UAVs are remotely controlled or fly autonomously based on pre-programmed flight plans or real-time data, and they can provide more cost-effective solution for monitoring large areas compared to traditional human inspection methods. In view of this, an UAV-driven solution for assisting structural health monitoring solution was developed in ref.6, where the structural health monitoring practices were developed to asset management framework. In ref.7, UAVs were employed to monitor the ship exhaust emissions, where the collected data on UAVs can be transmitted wirelessly to the ground station. In order to extend battery life, ships can be adopted to act the mobile supply bases of UAVs, and hence, the joint routing and scheduling solution was developed to monitor the pollution from vessels8. A LabVIEW-based online monitoring and safety evaluation system for UAVs was designed in ref.9, and its aim was to offer a flight guarantee for autonomous flying. Nonetheless, the UAV-based monitoring systems suffer from the limited battery life and payload capacity10,11, which are not sufficient for large-scale or continuous monitoring of vast marine areas. In addition, UAVs are sensitive to weather conditions. For example, the strong winds, heavy rain, or poor visibility (such as fog) can limit their performance or prevent flights altogether, resulting in missed monitoring opportunities and compromised data quality12. These properties limit the application fields of UAVs in the monitoring of marine activities.

Based on the above considerations, some researchers attempt to employ autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) to monitor the maritime activities. Compared with the UAV-based monitoring system, AUVs can inspect the hulls of ships to identify corrosion, damage, or biofouling (e.g., the accumulation of marine organisms on the hull). This helps reduce the need for expensive dry-docking or manual inspections, providing more frequent and detailed assessments. Meanwhile, AUVs can monitor the condition of marine region, including checking for sedimentation, pollution levels, and overall water quality. Inspired by this, an AUV-assisted sequence algorithm for towed force estimation was developed13. In ref.14, an AUV prototype was designed to support the protection challenges. Followed by this, a swarm of AUVs were employed to measure the submesoscale dynamics15, which can measure the underlying horizontal flows within the swarm. Based on the idea of mean-shift exploration, a swarm strategy for terrestrial vehicle was developed to assemble highly complex shapes16. However, the proposed solutions in refs.13,14,15,16 focused on the motion control of vehicles, and they ignored the sensing, communication and control abilities of vehicles during the monitoring procedure. As far as we know, the marine environment is harsh, which makes it hard to accurately acquire the sensing information of marine targets. On the other hand, surface and subsurface wireless communications are often limited, which make real-time data transmission challenging. Although the seafloor telecom cables can be deployed to sense the underwater activities17,18, the telecom cables have poor mobility ability, which may significantly reduce the application domain for dynamic environment. With consideration of the harsh underwater environment, how to systematically design the AUV-assisted monitoring system for marine monitoring is largely unsolved.

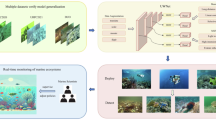

Here, we propose a ubiquitous monitoring solution for marine activities by using the cooperation of AUVs, as depicted by Fig. 1a. The main idea is summarized as follows: when AUVs are on water surface, they recognize the surface target (e.g., ship or buoy) with the onshore cameras, such that the target attitudes can be estimated by using deep learning technology; when AUVs are under the water surface, they detect the underwater target (e.g., shipwreck or drowning person) with the onshore sonars. Meanwhile, the radio and acoustic waves are both adopted to ensure the bilateral communication between human operator and AUVs. Finally, the effectiveness of the our solution is verified by the experimental results. Compared with existing marine monitoring systems, the main contributions of our solution can be provided as follows: (1) Systematical design of the AUV-assisted monitoring system. Key components include AUVs, human operator, onshore cameras, and wireless communication networks. The proposed system can recognize the surface target attitudes, and more importantly, it can detect the underwater target with the assistance of human in a boat/vessel on water offshore; (2)Data Interaction Logic. Our system employs a hierarchical data exchange framework that ensures real-time data integrity via multi-channel redundant transmission; (3) On-line recognition algorithm. With regard the the dynamic ocean environment, we establish the target dataset to offline train the YOLOv8-obb network, such that an on-liner recognition algorithm is developed to estimate the state of target; (4) Teleoperation control of AUVs. A remote teleoperation controller is developed to drive AUVs to the neighboring areas of monitoring target with the help of human on the loop, making it an essential tool for complex underwater missions; (5) Integration with the open-source artificial intelligence (AI) model DeepSeek. In order to enhance the autonomous decision-making capability and environmental adaptability of the marine monitoring system, the DeepSeek19 is leveraged to assist the monitoring operators in judgment, comprehension, and reasoning tasks. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first integrated solution that simultaneously solves the sensing, communication and control for the ubiquitous monitoring of marine activities via the cooperation of AUVs.

Results

Hardware design

As shown in Fig. 1b, the hardware design of the proposed monitoring system mainly consists of AUVs, human operator, onshore cameras, and wireless communication networks.

Ubiquitous monitoring of marine activities . (a) Description of the monitoring system. (b) Experimental setup, including AUVs, human operator, onshore cameras, and communication network. (c) Block diagram of our monitoring, where human operator makes remote operations based on the collected measurements.

-

1)

AUV. Note that the collective motion of biology can create adaptable, efficient, and robust swarms capable of performing diverse tasks in various environments20,21. Particularly, each biological system (such as bird, fish and insect) interacts with its neighboring individuals to perform complex and intelligent behavior, which enable the transition from individual intelligence to collective intelligence. Inspired by this, we adopt the cooperation of AUVs to perform the monitoring task. Specifically, the size of AUV in our system is 75cm\(\times 57\)cm\(\times 55\)cm, and its weight is 90kg. It includes buoyancy modules, searchlight, thrusters, control cabin, camera and detection sonar. Specifically, the buoyancy modules allow AUV to achieve neutral buoyancy, maintain depth control, optimize energy usage, and remain stable throughout its mission. The searchlight can provide a maximum brightness of 2200 lumens, and its role is to enhance visibility during AUV operations. Six thrusters (i.e., two vertical thrusters and four horizontal thrusters) are deployed on each AUV, which enable AUV to move through the water, control its speed, direction, and orientation, and carry out complex monitoring tasks. Each thruster is driven via a pulse-width modulation (PWM) control signal generates by the STM32 processor, allowing fine adjustment of thrust magnitude. Of note, each thruster provides 8 kgf of thrust, and it allows the AUV to reach a maximum speed of 4 knots. The roles of camera and detection sonar are to detect the target (i.e., the surface and underwater targets) by optic and acoustic measurements, respectively. Note that the sonar is produced by AOHI22, which has a maximum operating frequency of 1.2MHz, a maximum number of beams of 512, a horizontal beam angle of 130\(\vphantom{0}^{\circ }\)/130\({^{\circ }}\), and a vertical beam angle of 20\(\vphantom{0}^{\circ }\)/20\(\vphantom{0}^{\circ }\). In addition, the entire AUV is powered by a power supply with an output of 24V.

In the control cabin, the Jetson Nano development board functions as the high-level control unit of the AUV, responsible for real-time image processing, sensor fusion. The STM32 processor serves as the low-level controller, executing thruster control, sensor data acquisition, and safety monitoring. A master–slave architecture is established between the Jetson Nano and STM32 via serial communication, enabling real-time command execution and feedback. This architecture ensures deterministic response in time-critical tasks while allowing the Jetson Nano to handle computationally intensive operations. It provides the necessary computational power for real-time data processing and computer vision tasks in an energy-efficiency way. In order to drive the thrusters and receive the measurement data, the STM32 processor is also installed on AUV. Additionally, the GPS (Global Positioning System), IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit), depth sensor and ranging sonar, are jointly employed to capture the real-time motion of AUV.

-

2)

Human Operator. The measured data and video stream are first decoded, and then be displayed by the host computer in a real-time way. Of note, the human operator analyzes this information to make real-time decision. Specifically, the human operator interacts with the underwater remote environment through the manipulator, which allows the precise control in hazardous marine environment. Notably, the control commands are initiated by the human operator, and then be transmitted back to the AUV by wireless bridges. Accordingly, the underwater teleoperation can be accomplished.

-

3)

Onshore Camera. As shown by Fig. 1a, onshore cameras are deployed to monitor the coastal surface target. The cameras are produced by Hikvision23, with 400w pixels and 360-degree rotation with internal servos. The onshore cameras collect images of the target’s baseline (e.g., the ship waterline) and transmit them to the host computer, through which host computer can estimate target’s attitude via the embedded deep learning model.

-

4)

Telecommunication Network. The following three transmission channels are adopted in our system: (a) the wired transmission is employed to achieve data transmission between onshore cameras and host computer; (b) the umbilical communication is employed to achieve data transmission between AUV and cable car; (c) the wireless bridges are employed to achieve data transmission between cable car and host computer. For the wired transmission, it adopts IEEE standard 802.3 protocol24, whose maximum transmission rate can reach 1000Mb/s. For the umbilical communication, it adopts IEEE standard 1901.1 protocol25, with a frequency band of 30mhz and a maximum transmission rate of up to 500Mb/s. The bridge equipment uses a 6db omnidirectional antenna to transmit data. Based on this, a self-organizing network configuration can be constructed, whose broadband peak frequency is 120Mbps. This hybrid communication method of wired and wireless to ensure communication reliability. When communication interference or temporary disconnection occurs, a redundant failover mechanism switches the active channel based on signal quality monitoring.

Software design

As shown in Fig. 1c, the software design includes the self-localization of AUVs, the target attitude monitoring, the monitoring environment three dimensional (3D) reconstruction, the construction of management platform, and the integration with DeepSeek model.

Communication effectiveness at Tangshan Port in China. (a) Deployment of the communication equipments. (b) Communication rate test when the relative distance from AUV to the host computer is 100 m. (c) Data transmission integrity test. (d) Communication qualities when the relative distance is from 100 to 2000 m.

-

(1)

Self-Localization of AUVs. The role of the localization unit is to provide the real-time position information of AUVs. When AUVs are on the water surface, GPS is adopted to acquire the position information, and its accuracy is within 0.1 m. When AUVs are under the water surface, underwater GPS produced by WaterLinked is adopted. Of note, the Time Difference of Arrival (TDOA) algorithm is conducted by underwater GPS, where four receivers are installed on the baseline of T-shaped structure to receive localization signals from the AUVs. Besides that, IMU serves as a supplementary localization unit, especially when the signals from GPS or underwater GPS are not well received due to the environmental noises. It is noted that the Kalman filtering algorithm is conducted by the IMU.

-

(2)

Target Attitude Monitoring. The procedure of target attitude monitoring includes the following three steps: (a) Construct the preprocessed and labeled target baseline datasets, through which the offline models of YOLOv8-obb network and decoder coding network can be constructed; (b) Collect the target baseline images by the cameras mounted on AUVs and shore; (c) Acquire the positions of baseline within the images and identificate them by using the YOLOv8-obb model, such that the target’s draft values are obtained; (d) With the above draft values, one estimates the attitude of target by difference calculation.

-

(3)

Monitoring Environment 3D Reconstruction. The role of the 3D reconstruction is to create a detailed, accurate, and interactive 3D model of the monitoring environment. This allows us to accurately document potential defects and visualize the environment in a highly intuitive and interactive way. To this end, the Unity 3D (U3D) software is employed to reconstruct the monitoring environment, and its procedure consists of two main parts: (a) Offline environment setup. A 3D model of the monitoring environment is constructed by using satellite map and on-site photographs; (b) Online recognition and recording. The optical and acoustic data collected by AUVs are used to identify and annotate potential defects, (e.g., cracks and exposed reinforcement bars). Clearly, the above implementation makes it convenient to monitor long-term structural integrity and detect any defects in marine monitoring environment.

-

(4)

Management Platform. The role of the management platform is to control the entire system and realize monitoring of the marine activities. Its functions include data visualization/recording, AUV motion control, safety precaution, and database storage. To this end, the QT software24 is employed to set the management platform, and its procedure consists of four main parts: (a) Software interface design. Using Qt Designer, one uses the layout manager to design interface (e.g., video streams display windows, control buttons and data windows), and then, the User Interface Compiler(UIC) tool is used to convert the interface into C++ code for convenience of debug; (b) Data processing and analysis. The data from onshore cameras and AUVs are displayed on the interface, while the human operator analyses the data and sends out the control comments to AUVs; (c) Data logging and security alerts. A record is embedded into the management platform, such that the data from draft, sensors, sonar and cameras can be displayed; (d) Monitoring environment database. In order to bridge the gap between the environment and the 3D reconstruction, the MySQL software is employed to set up the monitoring environment database.

-

(5)

Integration with the DeepSeek Model. It integrates DeepSeek to augment operator capabilities in critical judgment, situational understanding, and operational reasoning. Specifically, DeepSeek supports mission planning by generating adaptive patrol routes based on environmental conditions and historical detection data. Its framework comprises four key components: (a) Comprehensive data integration. According to the maritime monitoring regulations, one builds a unified database that synthesizes AUV information and the monitoring environment; (b) Intelligent data inter-connectivity. One deploys a standardized MCP (Model Context Protocol) interfaces to facilitate seamless, high-bandwidth data exchange between the central control system and DeepSeek’s AI engine, such that the instantaneous processing of monitoring data and dynamic terminal status information can be ensured; (c) AI-driven decision support. The host system generates intelligent operational recommendations through DeepSeek-processed analytics, and hence, it is presented via an intuitive visual interface that enables effective human-AI collaboration for critical decision cycles; (d) Continuous optimization. One implements an adaptive closed-loop system that progressively refines monitoring protocols, ensuring optimal coordination between AUVs while maintaining operational resilience. This synergistic integration of advanced AI with marine monitoring infrastructure can deliver transformative improvements in both operational intelligence and dynamic environmental responsiveness across all maritime domains.

Recognition of the ship waterlines. (a) Waterline shape for the bulk carrier. (b) Establishment of the ship waterline dataset. (c) Precision-confidence curve for the classification model. (d) Recall-confidence curve for the classification model. (e) Segmentated image. (f–h) The recognized waterline regions of ship at different positions. (i) Recognized ship waterlines.

Experimental results for the surface ship

We first give the experimental results in port, whose aim is to monitor ship attitude and port basin.

-

Effectiveness of the communication network. The experiment setup is conducted in Tangshan Port, which is an important deep-water port for the northern region of China. The port water depth ranges from 12–15 m, and wave heights below 0.5 m, indicating a relatively calm surface state. The visibility in air was approximately 2 km, while the underwater optical visibility was estimated at 2–3 m, suitable for camera-based recognition tasks. The deployment of the communication equipments is shown in Fig. 2a, where the initial distance between AUV and host computer is 100 m. Based on this, the data transmission rate from AUV to the control center is shown in Fig. 2b. We can find that the communication rate is larger than 9.8 Mbp/s. Besides that, we also test the data transmission integrity, which is an important index to evaluate the network quality and data integrity. From Fig. 2c, the sequence numbers are presented to track the ordered transmission and reliability of data, where the packet loss rate is very small since the curves of receiver windows size, the sending data and the acknowledged sequence number are almost coincident. That means the communication quality can be ensured. In order to further verify the reliability of telecommunication, we adjust the communication distance from 100 to 2000 m at Bohai Sea Qinhuangdao area. Correspondingly, the communication qualities (i.e., Signal-to-Noise Ratios (SNRs)) at different distances are shown in Fig. 2d. Clearly, the quality of the communication network can be guaranteed in the port area, since the maximum port berth in Tangshan Port is 1.5 km. The above results reflect the communication effectiveness of our monitoring system.

-

Effectiveness of the motion controller for AUV. After receiving the monitoring request, AUVs require to reach the desired monitoring area by the motion controller. To test its effectiveness, the target point is set to be \(119^\circ\) 24’ 37” E and \(39^\circ\) 46’ 46” N at the port waterway, as shown in Fig. 3a. Without loss of generality, the average wind is 3 beaufort scale. An obstacle (i.e., the ship in Fig. 3a) is set in our scenario. Accordingly, the trajectories for one AUV are shown in Fig. 3b. The detection data for the obstacle with the sonar are shown in Fig. 3c. From Fig. 3a–c, we can find the tracking control can be accomplished. The obstacle can be effectively detected, and more importantly, the obstacle collision can be avoided since all the relative distances are larger than zero meter. Besides that, we set the desired depth is \(-5\) m, and hence, the depth control for the AUV is verified by Fig. 3d. Clearly, AUV has the diving ability to monitor the port basin at a specific depth.

-

Recognition of the ship waterlines. Taking the bulk carrier as an example (see Fig. 4a), we establish the dataset of ship waterlines, where some selected images are shown in Fig. 4b. Specifically, the collected data includes video streams, 20 hours of continuous video clips and image frames from AUV, and 5000 annotated frames with visible waterlines. Based on this, the offine training is conducted, where the evaluation indexes such as Precision-Confidence and Recall-Confidence curves are shown in Fig. 4c–d, respectively. From Fig. 4c, one knows the trade-off between recognition precision and confidence can be balanced by the offline model. Meanwhile, the trade-off between recall and confidence can also be balanced, as depicted in Fig. 4d. Before implementing the online recognition, the collected image is segmentated, as shown in Fig. 4e. After that, the online identification operation is implemented by the cameras. The waterline regions at different positions are recognized by Fig. 4f–h. The recognized ship waterline is shown in Fig. 4i.The average accuracy of the recognition model in identifying ship water gauges reaches 92.4%, and the frame processing rate remains at 28 FPS. Clearly, the recognition algorithm can effectively recognize the ship waterlines. That means the ship attitudes can be indirectly estimated, i.e., the ship has a draught of 8.5 m.

-

Effectiveness of port basin 3D reconstruction. The 3D reconstruction of port basin plays an important role in reducing the risks and enhancing the overall functionality of port facilities. For considering this, we acquire the offline Google map of Tangshan Port, as shown in Fig. 5a. Meanwhile, some on-site images are also employed, as provided by Fig. 5b–c. In order to capture features such as exposed rebar or cracks in the port basin, we simulate a scenario with exposed rebar in the water tank (see Fig. 5d), and then, the feature-related dataset (see Fig. 5e) can be established. Correspondingly, the recognized deficiency by using sonar in the water tank can be shown in Fig. 5f. After that, AUV is employed to collect visual and acoustic data from the port basin, as shown in Fig. 5g–h. Finally, the U3D software is adopted to generate the 3D model of port basin, as shown in Fig. 5i.

-

Construction of the management platform. To enable real-time visualization and decision support, we construct a management platform for the ubiquitous monitoring of ship and port basin. Specifically, it displays sensor data, video streams from AUVs and onshore cameras, as shown in Fig. 6. By integrating real-time data, automation, and analytic, the constructed management platform can enhance the operational performance, reduce the costs, and provide better services to human operator.

Effectiveness of port basin 3D reconstruction. (a) offline Google map of Tangshan Port. (b) On-site image such as the portal cranes. (c) On-site image such as the scheduling center office. (d) Exposed rebar in the water tank. (e) Feature-related dataset, which contains datasets of structural features such as cracks, corrosion, and exposed rebars in underwater infrastructures. (f) Recognized deficiency by using sonar in the water tank. (g) Visual data from the port basin. (h) Acoustic data from the port basin. (i) 3D model of port basin with the U3D software.

The upper-left section of the platform is used to display the raw and altered image from AUVs and onshore cameras; the upper-middle section is the image processing operation area; the upper-right section displays AUV parameters data, autonomous movement target point settings, and ship waterline recognition results; the lower section shows the 3D attitude of the ship.

Experimental results for the underwater target

We give the experimental results in pool, whose aim is to evaluate sonar-based target detection capability. Figure 7a,b illustrates the experimental setup, where a yellow drum serves as the simulated underwater target. This test scenario effectively mimics real-world conditions applicable to underwater search and rescue operations, particularly for locating drowning victims.

-

Effectiveness of the DeepSeek-based motion control. DeepSeek runs on the shore-based host, assisting operators with mission planning and task prioritization by analyzing real-time data from multiple AUVs. Chosen for its lightweight, modular design and high inference speed, it’s fine-tuned on marine data (sonar imagery, navigation logs, operational records) to improve domain awareness and terminology handling. The model integrates with the AUV control system via standardized APIs; latency, stability, and resource use are continuously monitored, with automatic fallback to manual control on anomalies. Communications are protected by multi-layer security, and the model executes in an isolated environment to mitigate cyber risks. Overall, DeepSeek boosts autonomy and efficiency—enabling smoother multi-AUV coordination, faster task reallocation, and reduced operator workload without increasing onboard compute. The experiment setup is conducted in Yanmin Pool at Yanshan University. By using DeepSeek model, one enters into the text of “Emergency alert! Dispatch patrol units immediately!”. After that, the DeepSeek model replies the text of “Received, patrol has been initiated!”, as shown in Fig. 7c. Specifically, AUVs construct a maintainable contextual dialogue list, which includes the monitoring tasks, the sensing data, and the decisions for each dialogue round. Along with this, AUVs integrate the DeepSeek decisions into control commands, through which AUVs are derived to detect the existence of target, as shown in Fig. 7d.

-

Effectiveness of the sonar-based detection capacity. Following the pre-programmed search patterns illustrated in Fig. 7d, AUV conducts a systematic sonar sweep of the designated monitoring zone. The onboard sonar successfully identifies the target object at T+03:55 (mission elapsed time), with the acquisition confirmed by visual returns as depicted in Fig. 7e. These results confirm the effectiveness of our monitoring system for underwater target.

Discussion

AUVs are employed in this work to achieve ubiquitous monitoring of marine activities. Different from the simple motion control of AUVs, we systematically design the AUV-assisted monitoring system for marine activities toward human-in-the-loop, such that the human intelligence and abilities can be brought to bear on complex underwater tasks. Our system is inspired by the basis idea in ref.27, but it is fundamentally different from the solution in ref.27. Particularly, the main differences can be summarized as follow: (1) Sensing unit. The radar is adopted in the above literature to obtain the point cloud data, however the radar cannot be applied to underwater environment due to light scattering and absorption. For that reason, the sonar is used in our system to detect the underwater target; (2) Communication unit. The electromagnetic wave communication is adopted in ref.27 to guarantee the communication transmission, however it cannot be used in underwater system, and hence, the acoustic communication is employed in our system to guarantee the communication transmission; (3) Localization unit. GPS is used to achieve vehicle localization in ref.27, but GPS signals are entirely blocked in underwater environment. For that reason, the UGPS is adopted in our system to achieve precise underwater localization by TDOA algorithms; (4) Control unit. Autonomous vehicles only need to consider two-dimensional planar motion,while AUVs need to consider three-dimensional spatial motion. Therefore, the three-dimensional motion planning is considered in our system, which is ignored in ref.27. Meanwhile, our system not only boosts the capability to handle unforeseen or dynamic situations but also optimizes human resources, ensuring effective and intelligent oversight of AUV operations. Therefore, our system is fundamentally different from ref.27.

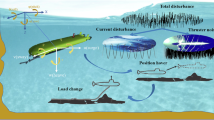

Air-surface-underwater integration cross-domain monitoring system. UAVs perform aerial monitoring and provide wide surface coverage, while they also act as the relay nodes for data to the shore-based center. USVs conduct surface monitoring, while they relay the aerial and underwater data. AUVs perform underwater tasks such as harbor basin exploration through swarm collaboration. Accordingly, the control center integrates global information to optimize task planning and remote control.

Our system can also be applied to the other application scenarios, such as marine monitoring28, off-shore exploration29, submarine rescue30, cooperation navigation31,32, pipeline patrol33 and tsunami warning34. Nevertheless, there are still some unsolved issues for the ubiquitous monitoring of marine activities. For example, our system lacks the air space monitoring ability, and hence, it cannot monitor the surface element of a target, e.g., the deck of a ship. Thereby, it is necessary to employ UAVs, unmanned surface vessels (USVs), and AUVs to cooperatively achieve the monitoring task, as depicted by Fig. 8. Based on the above consideration, we discuss some important yet unresolved issues in the cross-domain swarm collaboration monitoring process, as well as directions worthy of further exploration in the future.

-

Development of Cross Domain Swarm Standards. The cross-domain swarm monitoring of marine activities can comprehensively utilize various technologies and resources. It can overcome the limitations of a single field, achieve efficient collaboration of multiple tasks, and bring unprecedented opportunities for marine monitoring. However, different fields may adopt different technical standards and specifications, while each field may have unique operational processes and regulations. At the same time, different countries or organizations have different management standards and legal provisions for cross domain swarm. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a unified framework and standardized protocols for cross domain cooperation. By developing unified technical interfaces, the integration/collaboration between different fields can be promoted. As a result, the overall efficiency and availability of cross domain swarm systems can be improved.

-

Integrated Architecture of Sensing, Communication and Control . At present, the sensing, communication, and control functions of cross-domain swarm are designed independently. That means the related devices compete with each other in energy consumption and frequency band. Due to their size limitations, it is hard to improve the perception and communication interaction functions. Note that the sensing, communication and control have similarities in working principles, system architecture, signal processing, and operating frequency bands. The above property brings possibilities for integrated design of sensing, communication control. Mealey35 first proposed the integration idea of radar detection and communication in the 1960s. With consideration of the marine characteristics, how to design an integrated exploration and control architecture for cross domain swarm remains a challenge to be solved in recent years.

-

Cross-Media Communication Technology. In order to ensure the communication, it is necessary to interact with various types of manned/unmanned platforms, such as UAVs, USVs and AUVs. Therefore, the various communication methods such as underwater acoustics, optics, electromagnetism, and others can be integrated to enhance the reliability and transmission speed of cross medium communication. On the other hand, one can develop the relay-based communication technology, where the effective information communication with other unmanned platforms can be achieved. The implementation of the above functions requires to overcome multiple technologies, such as optoelectronic conversion technology, radio frequency conversion technology, protocol conversion and relay technology.

-

Cross Domain Swarm Driven by Artificial Intelligence. Driven by the artificial intelligence technology, cross domain swarm can achieve more efficient and intelligent applications. For example, various platforms can make intelligent decisions through machine learning and inference algorithms. Meanwhile, it can enhance the coordination ability with other platforms to achieve better overall results. In addition, the artificial intelligence technology can enable cross domain swarm platforms to have intelligent perception and data analysis capabilities, thereby extracting valuable information and helping them make more accurate and timely decisions. However, it is not possible to mechanically transplant artificial intelligence technology into cross domain swarm. Instead, we should fully consider the characteristics and requirements of cross domain swarm, through the cross-domain swarm in combination with the advantages and limitations of artificial intelligence technology can be effectively guaranteed.

-

Application Platform in Real Ocean Environment. Till now, most of the results are verified through simulation software. While the simulations are incredibly valuable, the real ocean testing is still required to verify the performance of ship and port basin monitoring in dynamic environments. For example, the search and rescue missions should be verified in real lake or ocean environment36, rather than on the simulation software. This helps uncover problems that may not have been anticipated during simulation (e.g., the sensor calibration issues, the network interference, or the regulatory constraints). However, it is hard or costly to perform the real-world testing. To this end, researchers should bridge the gap between simulation results and practical deployment. Meanwhile, the collaboration and data sharing with maritime organizations could also be a way to carry out these tests more effectively.

Methods

AUV self-localization and motion control

As mentioned above, AUVs use GPS for surface localization and UGPS for underwater localization, which allow AUVs to determine their position information. After that, they employ proportional derivative (PD) controller for motion control. Particularly, the TDOA algorithm is utilized by the UGPS to estimate the position information of AUVs. To simplify without losing generality, we take AUV 1 as an example, through which the principle for self-localization of AUV 1 via UGPS can be provided as follows. When performing 3-D path planning, the influence of the surrounding marine environment is explicitly considered. The water surface defines the upper operational boundary of the AUV to prevent it from accidentally surfacing except when GPS localization is required. The seafloor defines the lower limit of navigation depth, which is obtained from depth sensors or bathymetric data to avoid ground collision. In addition, volumetric obstacles, such as submerged facilities or moored ships, are identified through sonar sensing and treated as restricted zones during route generation. These environmental boundaries ensure that the planned trajectory remains within a safe and navigable region of the underwater workspace.

Four transducers are carried by the buoy. We define \(t_{h}\) as the time stamp when AUV 1 broadcasts its localization request, and let the AUV position vector be \(\textbf{p}\in \mathbb {R}^3\). Similarly, we denote the time stamp when each transducer receives the signal as \(t_{i}\), where the known position of transducer \(i\in \{1,2,3,4\}\) is \(\textbf{r}_i\in \mathbb {R}^3\). By the principle of TDOA, the time difference between transducers i and j is

where \(c_{w}\approx 1,500\)m/s denotes the average underwater acoustic speed, and \(n_{i,j}\) denotes the measurement noise. Of note, \(n_{i,j}\) follows a zero-mean Gaussian distribution.

Using (1), the time-difference measurements are stacked as

where \(\widetilde{\textbf{t}}\) is the measurement vector, \(\varvec{\phi }(\textbf{p})\) is a vector-valued nonlinear function of the AUV position, and \(\textbf{w}\) is the noise vector with covariance matrix \(\textbf{S}\).

With the estimated position information, the current position vector of AUV 1 can be obtained. Then, AUV 1 is required to arrive at the neighboring areas of the ship. The PD controller calculates the error between the current position and the target position, through which the control input is adjusted to move the AUV towards the desired state. Specifically, the motion control of the AUV can be divided into position control and heading control. The goal of position control is to move AUV 1 from its current position to the target position. To this end, the error \(\textbf{p}_{\mathrm t}\) is given by

The PD controller output for position control is

where \(K_{p}\) and \(K_{d}\) are scalar gains, and \(\dot{\textbf{e}}(t)\) is the time derivative of the position error vector.

The goal of heading control is to drive the AUV to the desired heading \(\theta _{\mathrm t}\). Let the heading error be

Then the PD controller output for heading control is

where \(K_{p\theta }\) and \(K_{d\theta }\) are scalar gains for heading control.

Accordingly, the STM32 processor computes the pulse-width modulation (PWM) signals to drive the thrusters. Since the thruster power is proportional to the applied voltage, the PWM duty cycle is adjusted to change the thruster voltage. When necessary (e.g., in port emergencies), a human operator can directly modify the control signal. Through the above procedure, the control strategy can be applied by AUVs in the actual environment.

Target attitude monitoring

Target attitude monitoring includes baseline identification and attitude estimation. Specifically, the baseline recognition process consists of two stages: offline training and online recognition. In the offline training stage, a network model is trained to meet the target recognition requirements. In the online recognition stage, the real-time baseline detection is performed by using the trained model.

Before performing the offline training, we give the evaluation index of YOLOv8-obb network. It consists of four components: localization loss function \(L_{loc}\), object loss function \(L_{obj}\), regularization loss function \(L_{reg}\) and classification loss function \(L_{cls}\). The loss function is expressed as follows

where \(\lambda _{cls},\) \(\lambda _{loc},\) \(\lambda _{obj}\) and \(\lambda _{reg}\) denote the weight coefficients for each loss component. Specifically, \(\lambda _{cls}\) controls the contribution of the classification accuracy, \(\lambda _{loc}\) adjusts the influence of the localization precision, \(\lambda _{obj}\) determines the sensitivity to the presence of target objects, and \(\lambda _{reg}\) regularizes the network parameters.

In (7), the classification loss function \(L_{cls}\) is defined as

where C is the class of the detected object. \(P_{i}^{j}\) and \(\hat{P} _{i}^{j}\) are the predicted and actual probabilities, respectively.

In (7), the classification loss function \(L_{loc}\) is defined as

with

where \(IOU\left( A,B\right)\) is the intersection over union between the predicted bounding box and the ground truth bounding box. \(\rho ^{2}\left( A_{c},B_{c}\right)\) is the squared Euclidean distance between the center points of the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes. m is the diagonal distance of the minimal enclosing region that can contain both the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes. \(w^{gt}\) and \(h^{gt}\) are the width and height of ground truth bounding box, respectively. w and h are the width and height of the predicted bounding box, respectively.

In (7), the classification loss function \(L_{obj}\) is defined as

where \(y_{obj}\) is the object existence label, and \(\hat{p}_{obj}\) is the predicted object score.

Meanwhile, the classification loss function \(L_{angle}\) is defined as

with

where \(\theta\) is the predicted angle, and \(\theta ^{gt}\) is the ground truth angle.

The classification loss function \(L_{reg}\) is defined as

where \(\Xi\) is the parameter set in the neural network model, and it need to be optimized.

The above index can improve the detection accuracy and robustness of the model in dealing with target baseline. Meanwhile, it can enhance the generalization ability of the model by regularization to prevent overfitting. In the following, the whole procedure of ship attitude monitoring is provided in detail.

Step 1. Construction of the dataset

We choose different weather, sea conditions, and targets for data collection. Specifically, the dataset in our system consists of 500 images of the target’s baseline at the bow (shoreward and offshore) and stern (shoreward and offshore). After data cleaning, the dataset is split into 400 training images and 100 test images. Through the above operation, different parts of the images are labeled. To maintain timeliness under dynamically changing marine conditions, an incremental dataset updating mechanism is planned. The system periodically collects new samples from AUV and onshore cameras during missions, automatically evaluating data novelty through distribution drift detection. Newly acquired samples are annotated and merged into the existing dataset using an active learning pipeline, ensuring that the YOLOv8-obb model continues to generalize across varying water clarity, lighting, and seasonal variations.

Step 2. Model training

The training images is then fed into the YOLOv8-obb network model, with the input image size adjusted to \(640\times 640\) to maintain consistency in input dimensions. For the model after offline training, the precision-confidence and recall-confidence curves are jointly adopted to evaluate the performance. Note that the precision measures the proportion of true positive predictions among all positive predictions, and recall measures the proportion of true positive predictions among all actual positive instances. Thereby, the precision-confidence probability \(P_{\text { precision}}\) can be defined as

and the recall-confidence probability \(P_{\text {recall}}\) is defined as

where TP denotes the number of correctly predicted positive instances, FP denotes the number of incorrectly predicted positive instances, FN denotes the number of actual positive instances missed by the model, and TN denotes the number of correctly predicted negative instances.

Based on (16) and (17), the model parameters are adjusted, so that it can learn patterns, relationships, and structures inherent in the data.

Step 3. Online target baseline recognition

The trained coding and decoding network is used to segment the position of the target’s baseline in the image. To balance accuracy and real-time performance, the recognition module is designed with an adaptive processing strategy. In actual operation, when the computational load increases, the module will give priority to real-time response and use a lightweight model to process data at the same time. When the computing resources are stable, it is restored to a full-precision model. After that, the YOLOv8-obb network is used to identify the baseline. Based on it, the draft value of the target is calculated according to the mapping between the unit pixel and the actual distance.

Step 4. Target attitude estimation

Based on Step 3, we take the ship attitude estimation as an example. Particularly, the draft data (i.e., the data \(D_{BP}\) for the shoreward end of the bow, the data \(D_{SP}\) for the shoreward end of the stern, the data \(D_{BS}\) for the offshore end of the bow, and the data \(D_{SS}\) for the offshore end of the stern) can be received. After that, we conduct the target attitude estimation. Specifically, the pitch estimation refers to the difference in draft between the bow and stern of a target, indicating whether the target is leaning forward or backward. Then, it can be calculated by

and meanwhile, the roll estimation refers to the difference in draft between the port (near shore) and starboard (away from shore) sides, indicating whether the ship is tilted to port or starboard. Based on this, it is calculated by

By using the draft measurement of the hull, the trim and balance of the target can be estimated effectively, which provides data support for the safety of the target.

3D reconstruction of underwater environment

We used Google Satellite Offline Maps and images taken on-site to reconstruct the 3D scene of the underwater environment using Unity 3D. The Google Satellite Offline Maps provide geographic coordinates and terrain data for constructing the 3D scene of the underwater environment. The on-site images provide visual information for the 3D scene, helping to fill in the details that may be missing from the offline maps. The on-site images include important features such as the docks, ships, port boundaries, buildings, and the water surface. The terrain is created using Unity’s terrain tools, and external models (such as docks, ships, and gantry cranes) are imported to complete the underwater environment. Based on this, images or sonar data collected by AUVs will be displayed in the virtual environment. This data can provide a foundation for subsequent structural analysis and 3D modeling of the underwater environment.

Management platform design

It uses a combination of AUVs and shore-based cameras to monitor the attitude of surface/underwater target. AUVs are equipped with sonar for detecting underwater features and cameras for capturing images of the target’s baseline. The sonar provides images of underwater features, while the cameras capture the baseline of the target, further supplementing the sonar data with visual information. The AUVs are deployed to monitor the baseline on the offshore side of the target, while shore-based cameras are positioned on the dockside to monitor the visible baseline of the target. Data from both AUVs and shore-based cameras are transmitted to the host computer via wireless bridges and wired connections. This setup allows us to obtain images of the baseline from different directions. By applying baseline recognition algorithms and target attitude estimation algorithms, we can determine the real-time attitude of the target. We develop a user-friendly interface using Qt, which integrates data from the AUVs and shore-based cameras, providing a centralized monitoring platform for human operators. The platform displays real-time sensor data, the target’s attitude, and collected image information. The platform supports both automatic and manual control of the AUVs, allowing operators to manage the monitoring system with flexibility. Additionally, it includes real-time data logging and alert mechanisms to ensure the safety of the targets.

Data availability

The data used in this work are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Of note, the videos of the experiment are provided by https://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XNjQ1MTUzNjA5Ng==.html or https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CcSshY-f91I. The part code of the management platform design used in this study is publicly available at https://docs.google.com/document/d/1iKF9E3jUOoBztCP6b0kNJVE-BUI8IJrp/edit?usp=drive_link&ouid=101727128613007613971 &rtpof=true&sd=true

Code availability

The part code of the management platform design used in this study is publicly available at https://docs.google.com/document/d/1iKF9E3jUOoBztCP6b0kNJVE-BUI8IJrp/edit?usp=drive_link&ouid=101727128613007613971 &rtpof=true&sd=true.

References

Huang, X. et al. Emitting and controlling ultra-low frequency underwater acoustic waves using a marine vibration system with time interfacing. Commun. Eng. 4, 51 (2025).

Zhuang, Y. et al. A deep learning framework based on structured space model for detecting small objects in complex underwater environments. Commun. Eng. 4, 24 (2025).

Fitzpatrick, A. et al. Multi-modal sensor fusion towards three-dimensional airborne sonar imaging in hydrodynamic conditions. Commun. Eng. 2, 16 (2023).

New Data Reveals Risk of Maritime Incidents in Ports and Terminals, 22 Feb, 2023. https://gcaptain.com/new-data-reveals-risk-of-maritime-incidents-in-ports-and-terminals/

Tran, T. A. et al. Combining machine learning with high-content imaging to infer ciprofloxacin susceptibility in isolates of Salmonella Typhimurium. Nat. Commun. 15, 5074 (2024).

Tsaimou, C. N., Sartampakos, P. & Tsoukala, V. K. UAV-driven approach for assisting structural health monitoring of port infrastructure. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 19, 1–20 (2023).

Peng, X. et al. Remote detection sulfur content in fuel oil used by ships in emission control areas: A case study of the Yantian model in Shenzhen. Ocean Eng. 237, 109652 (2021).

Shen, L. et al. Synergistic path planning for ship-deployed multiple UAVs to monitor vessel pollution in ports. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 110, 103415 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Autonomous UAV safety oriented situation monitoring and evaluation system. Drones 8, 308 (2024).

Khalid, A. et al. Control schemes for quadrotor UAV: Taxonomy and survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 56, 124 (2023).

Adil, M. et al. A systematic survey: Security threats to UAV-aided IoT applications, taxonomy, current challenges and requirements with future research directions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 24, 1437–1455 (2023).

Xia, X., Fattah, S. M. M. & Babar, M. A. A survey on UAV-enabled edge computing: Resource management perspective. ACM Comput. Surv. 56, 78 (2023).

Choi, J-K., Sakai, H. & Tanaka, T. Autonomous towed vehicle for underwater inspection in a port area. Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Robotics Autom., 188–193 (2005).

McNelly, B. P., Albert, C. & Appler, J. D. Prototyping an autonomous underwater vehicle to support port protection challenges. OCEANS 2023, 1–7 (2023).

Jaffe, J. S. et al. A swarm of autonomous miniature underwater robot drifters for exploring submesoscale ocean dynamics. Nat. Commun. 8, 14189 (2017).

Sun, G. B. et al. Mean-shift exploration in shape assembly of robot swarms. Nat. Commun. 14, 3476 (2023).

Sladen, A. et al. Distributed sensing of earthquakes and ocean-solid Earth interactions on seafloor telecom cables. Nat. Commun. 10, 5777 (2019).

Lin, J. M. et al. Monitoring ocean currents during the passage of Typhoon Muifa using optical-fiber distributed acoustic sensing. Nat. Commun. 15, 1111 (2024).

DeepSeek-AI. DeepSeek-V2: A strong, economical, and efficient mixture-of-experts language model. (2024).

Slade, P. et al. On human-in-the loop optimization of human robot interaction. Nature 633, 8031 (2024).

Xiao, Y. et al. Perception of motion salience shapes the emergence of collective motions. Nat. Commun. 15, 4779 (2024).

Searobotix. Detection sonar data sheet. Searobotix.com. https://searobotix.com/oculus/ (Accessed 27 Dec 2024).

LCSC Electronics (Shanghai) Co. Onshore camera data manual. LCSC.com. https://www.lcsc.com/datasheet/lcsc_datasheet_2409191732_HIKVISION-DS-2DE2Q140MY-T-GL2-2-8mm_C41359978.pdf (Accessed 6 Jun 2024).

IEEE. IEEE Std 802.3-2008, IEEE Standard for Ethernet (2008). https://standards.ieee.org/standard/802_3-2008.html (Accessed 30 Dec 2024).

IEEE. IEEE Std 1901.1.1-2020, IEEE Standard Test Procedures for IEEE Std 1901.1 for Medium Frequency (less than 15 MHz) Power Line Communications for Smart Grid Applications (2020). https://standards.ieee.org/standard/1901_1_1-2020.html (Accessed 30 Dec 2024).

The Qt Company. Qt. Qt.io. https://www.qt.io/ (Accessed 10 Jun 2024).

Pendleton, S. D. et al. Perception, planning, control, and coordination for autonomous vehicles. Machines 5, 6 (2017).

Ratnarajah, L. et al. Monitoring and modelling marine zooplankton in a changing climate. Nat. Commun. 14, 564 (2023).

Lee, D., Balachandran, T., Cho, H.-W. & Haran, K. Exploring fully superconducting air-core machine topology for off-shore wind turbine applications. IEEE Trans. Magn. 55, 1–6 (2019).

Shlesinger, M. Search research. Nature 443, 281–282 (2006).

Yang, K., Zhang, Z., Cui, R. & Yan, W. Acoustic-optic assisted multisensor navigation for autonomous underwater vehicles. Ocean Eng. 297, 117139 (2024).

Zhang, Z., Shi, Y., Zhang, Z. & Yan, W. New results on sliding-mode control for Takagi-Sugeno fuzzy multiagent systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 49, 1592–1604 (2019).

Zhao, Y. et al. An oil and gas pipeline inspection UAV based on improved YOLOv7. Meas. Control 57, 1068–1086 (2024).

Selva, J. et al. Probabilistic tsunami forecasting for early warning. Nat. Commun. 12, 5677 (2021).

Mealey, R. M. A method for calculating error probabilities in a radar communication system. IEEE Trans. Space Electron. Telemetry 9, 37–42 (1963).

Serra, M. et al. Search and rescue at sea aided by hidden flow structures. Nat. Commun. 11, 2525 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Anastasiia Vasylchenkova for the valuable suggestions on this article, and Tangshan Port for providing the experiment conditions.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants 62222314 and U25A20472; in part by the Yanzhao Young Scientist Project of Hebei Province under Grant F2024203047; in part by the National Science Foundation of Hebei Province under Grant F2022203001, and in part by the Education Department Foundation of Hebei Province under Grant JCZX2025027.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.P.G. conceived the project. Y.H.J., and X.X.W. performed the experiments. J.Y., X.Y., and C.L.C. analyzed the data. J.Y, and Y.H.J wrote the article, and all authors provided feedback.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, J., Jiang, Y., Wang, X. et al. Ubiquitous sensing of marine activities via the cooperation of autonomous underwater vehicles. Sci Rep 16, 2430 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29532-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29532-y