Abstract

Both column screw fixation (BCSF) technique offers a novel minimally invasive approach for the management of acetabular posterior column fractures. A body of research has been established in this area, encompassing data on screw diameter, insertion angles, and even the feasibility of placing two screws. This study further investigates the anatomical feasibility of the BCSF technique (including composition of the pathway, the pathway area, the maximum permissible screw diameter, and the optimal insertion angles) through a 3D reconstruction study, providing an evidence-based foundation for its clinical application. In this study, pelvic CT data were collected from 200 healthy adults (100 males and 100 females). By utilizing Mimics 21.0 software, three-dimensional pelvic models were reconstructed to simulate the BCSF procedure for posterior column acetabular fractures. The maximum cross-sectional area of the pathway, the maximum allowable screw diameter, and the longest feasible screw length were all measured. In addition, the research analyzed the optimal screw insertion trajectories. An irregular three-dimensional configuration was displayed by the screw insertion safe zone. The pathway comprises a pentagonal structure. Quantitative analysis revealed that the left pelvis had a safe passage area of (132.1 ± 33.76 mm²), permitting screws with maximum dimensions of (145.57 ± 10.74 mm) in length and (8.92 ± 1.41) mm in diameter, while the right pelvis demonstrated slightly larger parameters (area: 139.66 ± 38.01 mm²; maximum screw length: 143.09 ± 10.47 mm; and diameter: 9.29 ± 1.47 mm). Compared to (36.89 ± 7.14°) and (41.89 ± 4.40°) for right-sided procedures, optimal insertion angles were measured at (37.32 ± 5.62°) centrolateral tilt and (42.55 ± 4.32°) cephalad tilt for left-sided approaches. Male specimens exhibited significantly greater safe passage dimensions than females (p < 0.0001), in which analogous sex-related differences were presented within maximum screw diameters and lengths. In contrast, cephalad tilt angles showed no statistically significant gender variation (p > 0.05). This study defines the anatomical safe zone for BCSF technique in posterior column acetabular fractures. The established optimal screw trajectory enhances fixation strength and fracture stability as it enables the clinical use of larger-diameter screws. The patient-specific three-dimensional preoperative planning is recommended to be performed, which can ensure precise screw placement and maximize surgical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Posterior column involvement occurs in 15–30% of acetabular fractures, which encompasses both elementary and associated fracture patterns1,2. Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is mainly used to treat displaced and unstable acetabular fractures3. Lag screws fixation technique or combined lag screws with plates are the classic fixation methods4,5,6. Percutaneous minimally invasive fixation has emerged as the preferred treatment option for elderly patients and selected cases characterized by non-displaced or minimally displaced fractures, percutaneous reducible patterns, or situations where anatomical reduction is attainable via limited surgical approaches7,8.

Both retrograde and anterograde lag screw techniques are involved in the current surgical approaches for acetabular posterior column fixation. Anterograde screw fixation through the iliac fossa represents a widely used technique for posterior column fractures. Typically necessitating an anterior surgical incision, this approach is frequently combined with the lateral window of the ilioinguinal, pararectus, or lateral rectus approaches9,10. Even for experienced surgeons, safe and correct placement of anterograde posterior column screws remains challenging10.

The ischial tuberosity has been established as the entry point for percutaneous retrograde lag screws, whereas this method exhibits notable limitations, including risks of iatrogenic neurovascular injury, technically demanding patient positioning, and procedural complexity. The majority of the literature reported11,12 that with the patient in the supine position, simultaneous hip and knee flexion is required to both optimize access to the sciatic tuberosity and precisely identify the nail entry point, while minimizing risk to the sciatic nerve. A prone or lateral position has also been reported13.

In 2001, Starr et al14. introduced the “Magic screw” technique, representing an innovative minimally invasive approach for treating acetabular posterior column fractures. This method encompasses an entry point positioned superior to the gluteal pillar adjacent to the acetabular dome, with the screw trajectory directed toward the ischial spine, thereby generating an osseous pathway posterior to the hip joint15.

In the preliminary study, the feasibility of a novel BCSF technique for posterior column fixation was established. Our results demonstrated an optimal safe corridor extending from a point 3.0 cm from the widest portion of the iliac tubercle in the direction toward anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the center of the lesser sciatic notch16. A study by Öztürk et al.17, which analyzed pelvic CT data from 400 adults with Fujifilm-Synapse 3D software, has confirmed that the both column fixation corridor (BCFC) constitutes a universally valid and consistent osseous pathway in both genders and is suitable for the placement of two screws in pelvic and acetabular surgery. Through their innovative fluoroscopic approach for this anatomical corridor, subsequent validation by Öztürk et al.18 not only reproduced excellent clinical outcomes but also streamlined the technique’s clinical implementation, hence further confirming its efficacy in minimally invasive fracture treatment.

A body of research has been established in this area, encompassing data on screw diameter, insertion angles, and even the feasibility of placing two screws17,18,19. This study aims to further investigate the composition of the pathway, the pathway area, the maximum permissible screw diameter, and the optimal insertion angles using three-dimensional pelvic models. To bridge these knowledge gaps, a comprehensive research project consisting of four methodological components was developed: (1) Creation of three-dimensional pelvic models that utilized Mimics software; (2) Virtual screw insertion into bilateral acetabular posterior columns, with entry points established approximately 3.0 cm from the widest portion of the iliac tubercle in the direction toward ASIS and trajectories directed toward the center of the lesser sciatic notch; (3) Visualization of safe pathways through transparent pelvic models, with multiplanar verification (axial, coronal, and sagittal) of intraosseous screw placement, followed by quantitative measurements of channel dimensions, maximum screw parameters and the longest screw length; and (4) Precise angular measurements of the safe trajectory, which incorporated both centrolateral tilt and cephalad tilt angles. In our investigation, gender-based comparative analyses of these anatomical parameters were further included, and the findings from this study established an evidence-based framework for the safe and effective clinical application of this technique.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qilu Hospital (Qingdao), Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University (Protocol No: KYLL-KS-2024073). It complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to study enrollment, written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The pelvic CT (Computer Tomography) scans from 200 healthy adult volunteers (100 males and 100 females) acquired between May 2024 and November 2024 were retrospectively analyzed. The mean age was 45.2 years (range: 19–65) for male participants and 44.7 years (range: 20–60) for female participants. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) normal pelvic anatomy; (2) age between 18 and 70 years; and (3) complete imaging dataset available. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) history of pelvic or acetabular fractures (acute or healed); and (2) pelvic deformities or congenital abnormalities, metabolic bone diseases, primary or metastatic bone malignancies, severe degenerative osteoarthritic changes, etc.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of the pelvis

After being stored in.dicom format, the CT images were imported into the interactive medical image control system Mimics 21.0 software (Materialise, Belgium). Through selecting “Advanced segment” and choosing “CT bone”, the pelvis was extracted via steps including “Bone selection,” “Mask threshold,” and “Finishing.” Finally, the “Calculate part” function was leveraged to reconstruct the three-dimensional model of the pelvis.

Establishing the pathway

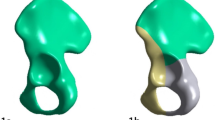

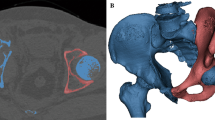

Under the “Analyze” function, a virtual screw was placed through harnessing the “Cylinder” tool to simulate fixation of the acetabular posterior column. The safe trajectory was defined as follows: the entry point was approximately 3.0 cm from the widest portion of the iliac tubercle in the direction toward ASIS and directed toward the center of the lesser sciatic notch16. To visualize the safe pathway, the pelvis was rendered transparent (Fig. 1). Irregular shapes were revealed by the cross-sections of each pathway. The pathway comprises a pentagonal structure. The screw position was verified in the axial, coronal, and sagittal planes, which ensured that it remained entirely within the bone (Fig. 1). The cases that met any of the following criteria were considered failures and excluded: (1) screw perforation of the cortical bone; and (2) screw intrusion into the joint space, which damaged the articular surface. A screw was regarded as well-positioned (i.e., within the safe zone) only if its whole path, from the entry point to the exit point, remained completely within the bone.

This study elected to perform measurements and analyses of the BCFC on both hemipelves. This approach was taken to evaluate the universal applicability of the technique in the presence of potential intra-individual anatomical variations and to establish a more robust data foundation for its safe application.

A Optimal screw trajectory demonstrating fixation of the acetabular posterior column using a single maximum-diameter virtual screw. B Transparent pelvic rendering revealing the irregular cross-sectional morphology of the safe osseous channel; C anatomical landmarks color-coded for orientation: Yellow: Medial wall of the iliac crest; Purple: Posterior column lateral wall; Blue: Lateral wall of the iliac crest; Pink: Medial acetabular rim; Black: Posterior column medial wall; D E F Confirmation in the coronal, axial, and sagittal planes that the placement screws are all in the channel.

Data measurement

In the “View”, “Reslice” was selected, the safety channel was adjusted, and the maximum diameter of the inserted screw was measured. “Area” was selected in the “Measure”, and the area of the channel was measured (Fig. 2a); and “Distance” in “Measure” was selected to measure the length of the longest screw placed (Fig. 2b). Through simulated screw placement, the screw angles (centrolateral tilt angle and cephalic tilt angle) for this safe channel are measured (Fig. 2c). The centrolateral tilt angle was defined as the lateral angulation relative to the axial plane, using ASIS-ischial tuberosity line as the reference plane. The cephalic tilt angle was defined as the inclination in the sagittal plane relative to the operative table plane, with the patient in a standard supine position.

Of course, the shape of the pelvis exhibits significant variations, and not all pelvises have this safe passage (Fig. 2d).

a Measure the area of the channel and the maximum diameter screw that can be inserted; b Measure the maximum length of the maximum diameter screw; c Measure the angle of the channel for insertion of the screw in the supine position. d A female patient with a very narrow passage in which screws could not be placed.

Data measurement and statistical analysis

To ensure measurement reliability and minimize observer bias, all morphometric parameters were independently measured twice by trained researchers, with the average values employed for final analysis. Before data collection, all evaluators completed comprehensive training that included study objectives and experimental protocols, fundamental principles of pelvic radiographic anatomy, and standardized operation procedures for Mimics 21.0 software.

Using SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), the complete dataset was systematically recorded and analyzed with the following statistical approach: continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x̄ ± SD).

Inter-group comparisons (male vs. female) were performed through leveraging independent samples t-test for normally distributed data, the Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric distributions, and a two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In the study, the anatomical feasibility of screw placement was evaluated, which revealed the following measurements. The left pelvic passage area was measured as 132.1 ± 33.76 mm² (range: 60.56–217.98 mm²), while the right was measured as 139.66 ± 38.01 mm² (range: 62.76–232.56 mm²). The maximum allowable screw length was 145.57 ± 10.74 mm for the left passage and 143.09 ± 10.47 mm for the right, respectively. Regarding screw diameter, the left passage accommodated screws up to 8.92 ± 1.41 mm compared to 9.29 ± 1.47 mm on the right. The left corridor could accommodate a maximum screw diameter of 11 mm, whereas the right corridor could accommodate a screw up to 12 mm in diameter. In the female left pelvis, 5% (5/100) of the channels had a maximum screw insertion diameter of less than 6.5 mm; similarly, in the female right pelvis, 3% (3/100) of the channels had a maximum screw insertion diameter of less than 6.5 mm. In the male pelvis, all channels had a maximum screw insertion diameter greater than 6.5 mm.

For optimal trajectory, the left pelvic passage allowed a centrolateral tilt of 37.32 ± 5.62° and a cephalic tilt of 42.55 ± 4.32°, whereas the right passage allowed 36.89 ± 7.14° of centrolateral tilt and 41.89 ± 4.40° of cephalic tilt (Tables 1 and 2).

In the study, significant sex-based anatomical variations in pelvic channel dimensions were identified. Men exhibited larger safe passage areas than women, with statistically significant differences in both the left (p < 0.0001) and right (p < 0.0001) pelvic channels. Besides, the maximum allowable screw length was significantly longer in men for both the left and right sides (p < 0.0001). Similarly, the maximum screw diameter that could be accommodated was larger in male pelves than in female pelves, in which these differences also demonstrated statistical significance (Table 1).

Compared to women, men displayed significantly greater centrolateral tilt angles for screws placed in the right pelvic channel (p < 0.05, Table 2). However, cephalic tilt angles showed no significant sex-based differences, with similar measurements observed for both left and right pelvic channels in men compared to women (Table 2).

Discussion

In this study, the safe passage for fixing the posterior column of the acetabulum with screws through the iliac crest is defined as follows. The entry point was approximately 3.0 cm from the widest portion of the iliac tubercle in the direction toward ASIS and directed toward the center of the lesser sciatic notch. The pathway comprises a pentagonal structure. The cross-section of this passage embraces an irregular shape, delineated by the medial wall of the iliac crest, the posterior column lateral wall, the lateral wall of the iliac crest, the medial acetabular rim, and the posterior column medial wall. In contrast, the traditional antegrade passage through the iliac fossa and the retrograde passage through the ischial tuberosity are approximately triangular in cross-section. Compared to these conventional approaches, the newly described passage exhibits a significantly more complex anatomical structure.

Both the size of the safe passage and the feasibility of screw insertion are determined by multiple factors. A narrower safe passage area restricts the allowable screw diameter and may preclude screw insertion in extreme cases. The participants in this study were primarily recruited from northern China. Pelvic morphological traits—including size, angles, diameters, and other dimensions—are shaped by multiple factors such as ethnicity, geographic locality, genetics, and environmental conditions. Consequently, variations in the origin of samples may directly impact the generalizability of the study results. Comparative data demonstrated anatomical variations of different bones between the Asian and European ethnicities20,21,22,23. Regarding the pelvic region, Arima et al22. showed that Asians have a significantly smaller pelvic incidence and a smaller sacral slope compared with Caucasians. Wagner et al23. showed that the Japanese pelvises have significantly smaller diameters of S1 corridors, resulting in more pelvises with a critical S1 corridor for trans-sacral implant positioning compared to Europeans. Ahrend et al24. studied one hundred clinical CTs of adult pelvises of Malay, Chinese and Indian descent, and the results showed that principal component analysis displayed large variability regarding the pelvic shape and size. Given the significant anatomical variability among individuals, preoperative planning must consider pelvic morphology and fracture line positioning, which can facilitate the selection of screws of appropriate diameter and length for optimal fixation.

Jung et al25. utilized Mimics software to create virtual 3D models of 178 hemipelves based on pelvic CT data and measured the safe zone for anterograde screw fixation in the iliac wing and the maximum screw diameter that could be inserted into this area. According to their study, the safe zone was triangular, in which the average area was 670.4 mm² (range: 374.8–1084.5 mm²) and the average maximum screw diameter was 7.4 mm (range: 5.0–10.0 mm). In this study, the measured areas were Left pelvic passage: 132.1 ± 33.76 mm² (range: 60.56–217.98 mm²) and Right pelvic passage: 139.66 ± 38.01 mm² (range: 62.76–232.56 mm²). This safe passage area is significantly smaller than that of the anterograde tension screw passage through the iliac fossa. Spanning the anterior and posterior columns, the fixation channel exhibits a relatively long trajectory. A discrepancy was observed between the cross-sectional areas of the left and right pelvic corridors, which may be attributed to measurement variations. The left or right pelvic passage area in males is larger than the safe passage area in females, primarily due to larger pelvic bones in males compared to females.

By recruiting 59 Chinese subjects without pelvic and acetabular injuries for CT scans, Feng et al26. determined the safe zone for anterograde screw fixation through the iliac fossa of acetabular posterior column fractures. The author identified that the average maximum diameter of virtual screws is 16.81 mm (14.20–20.40 mm), the average maximum diameter of male virtual screws is 17.54 mm (14.40–20.40 mm), while the average maximum diameter of female virtual screws is 15.75 mm (14.20–19.80 mm), which exhibited a statistically significant difference. Attias et al27. gathered CT data from 13 patients with acetabular fractures, reconstructed a three-dimensional model of the pelvis, and simulated the fixation of the acetabular posterior column with a virtual screw via the iliac fossa. The average maximum diameter of the virtual screw was measured as 11.4 mm (9.4 to 13.3), and the average maximum length was measured as 96.4 mm (101.6 to 85.9).

Through imaging, Yu et al28. examined percutaneous retrograde screw fixation of the posterior column channel of the acetabular, with a total of 100 pelvic cases included in the study. Compared to those in females, the length and maximum screw diameter that can be accommodated in the retrograde channel of the posterior column of the acetabular in males were larger. In the author’s research results, it is revealed that the posterior column channel of the acetabular is triangular in shape from the lower part of the acetabular to the greater sciatic notch area. The diameters of the acetabular posterior column channel in males and females are (17.21 ± 1.41 mm) and (15.54 ± 1.51 mm), respectively, which indicates that the acetabular posterior column channel has sufficient space to accommodate larger diameter screws. Hence, the author suggests that 7.3 mm screws should be utilized for rear column fixation regardless of gender.

The determination of the maximum screw diameter depends on the cortical bone thickness and medullary canal diameter of the target bone region, which should be measured based on a 3D reconstruction. The previous study indicates that pelvic cortical bone is relatively thin, and the Mimics software could not accurately extract cortical bone thickness. Therefore, this study did not account for cortical bone thickness in measurements. Instead, the maximum screw diameter was determined by closely aligning the screw with the outer cortical bone surface without penetration. A safety margin of 1–2 mm should be maintained between the screw’s outer edge and the inner cortical surface. In osteoporotic cases, this margin should be increased to 3 mm to reduce breach risk. Consequently, clinically applicable screw diameters should be smaller than our measured maximum values. In this study, it is seen that the maximum diameter of screws capable of being inserted into the left pelvic channel was (8.92 ± 1.41) mm (range: 6.0–11.0 mm), and the maximum diameter of screws that can be inserted into the right pelvic channel was (9.29 ± 1.47) mm (range: 5.5–12.0 mm), both of which were smaller than the maximum diameters of screws inserted into the other two traditional channels. Besides, the maximum diameter of screws inserted into males is larger than that of screws inserted into females, and the results obtained in the current study are consistent with previous research findings. Due to narrower anatomical dimensions, particular caution is warranted when using this corridor in female patients, where the risk of cortical breach or extraosseous screw penetration may be higher.

However, Öztürk et al.17 analyzed pelvic CT data from 400 adults, and Measurements revealed the following average values for female and male pelvises, respectively: virtual placement of anterior screws thicknesses were 6.5 ± 0.8 mm and 7.9 ± 0.9 mm. The results of that study were lower than ours, which we attribute to our more accurate depiction of the channel’s shape and area.

Some scholars also generate relatively small research results. According to Jung et al25., the safe area for fixing the posterior column of the acetabular with anterograde tension screws through the iliac fossa is triangular, and the average maximum diameter of the screws is only 7.4 mm (range, 5.0–10.0 mm). Mu et al29. studied 30 adult semi pelvic specimens and 5 complete pelvic specimens. It was found that the axial projection point of the posterior column of the acetabular was determined on the iliac fossa of the pelvic specimens, and the length of the anterograde tension screw of the posterior column of the acetabular was measured to be 104.8 ± 4.2 mm. The bone thickness around the screw was approximately 3.25 ± 4.25 mm after inserting a 6.5 mm diameter tension screw anterograde into the posterior column of the acetabular, and 6.5 mm diameter tension screws were inserted into the rear columns on both sides of the other five complete samples. The author believes that no problem exists in the insertion of 6.5 mm screws once the path is determined. It is found by the researchers that the reasons for this phenomenon include differences in pelvic morphology, the application of screws with specific diameters, and different experimental methods. In this study, a diameter greater than 6.5 mm was achieved in the majority of cases, providing robust internal fixation.

In this study, the longest screw that can be inserted into the left and right pelvic channel is (145.57 ± 10.74) mm and (143.09 ± 10.47) mm, respectively, which is much longer than the length of screws used within the other channels in clinical practice. Cavali et al9. clinically used anterograde screws with an average length of 100.4 mm (60–130). By studying 30 adult semi pelvic specimens and 5 complete pelvic specimens, Mu et al29. measured that the length of the anterograde tension screw was 104.8 ± 4.2 mm. Researchers imply that the insertion of such a long screw requires detailed preoperative planning, selecting screws of appropriate diameter and length, and avoiding damage to nerves and blood vessels, especially the obturator artery and vein, obturator nerve, and sciatic nerve, etc., during the screw insertion process, therefore laying the foundation for achieving satisfactory clinical efficacy.

By utilizing a 3D-printed pelvic specimen model, the author of this study previously inserted a 3.00 mm Kirschner wire into the channel during the process of surgery. It was found that the position and length of the Kirschner wire could be visualized when the C-arm machine was in the entrance position, iliac oblique position at 60°, exit position, and perpendicular to this channel. This study measured the centrolateral tilt angle and cephalic tilt angle of the screw. The centrolateral tilt angle and cephalic tilt angle of the screw inserted into the left pelvic channel were (37.32 ± 5.62)° and (42.55 ± 4.32)°, respectively, and the centrolateral tilt angle and cephalic tilt angle of the screw inserted into the right pelvic channel were (36.89 ± 7.14)° and (41.89 ± 4.4)°, respectively. Through the combination of these two, a more precise insertion of screws and a theoretical basis for the clinical use of this channel are both provided. With the patient in a standard supine position, we recommend use ASIS-ischial tuberosity line as the reference plane to define the centrolateral tilt angle and the cephalic tilt angle was defined as the inclination in the sagittal plane relative to the operative table plane.

The limitations of this study are as follows: (1) Significant anatomical variations exist among pelves and this study encompassed a relatively small sample size, which indicates that future studies should expand the sample size to minimize potential errors. These results highlight the need for additional validation via multicenter studies in diverse populations. In this study, a diameter greater than 6.5 mm was achieved in the majority of cases and the BCFC constitutes a universally valid and consistent osseous pathway; (2) The current screw trajectory planning was simulated using digital software and hence further validation through cadaveric experiments is necessary. Besides, the clinical applicability remains unproven. Several practical limitations, including the effects of soft-tissue interference, the physical presence of reduction instruments, and the technical difficulties associated with achieving optimal fluoroscopic views in a live surgical setting, must be considered.; (3) Future research will focus on developing surgical guides to enable a more minimally invasive approach while enhancing procedural safety; and (4) To evaluate the mechanical properties of this novel screw pathway and compare its biomechanical performance with traditional fixation techniques, the biomechanical testing will be performed in the next phase.

Conclusions

This study defines the anatomical safe zone for BCSF technique in posterior column acetabular fractures. By establishing safe screw corridor, clinicians can achieve stronger fixation and improved stability using larger-diameter screws. To ensure optimal screw placement, individualized preoperative 3D reconstruction simulations should be performed.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the present study are available from the author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BCSF:

-

Both column screw fixation

- ORIF:

-

Open reduction and internal fixation

- ASIS:

-

Anterior superior iliac spine

- BCFC:

-

Both column fixation corridor

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Mauffrey, C. et al. The epidemiology and injury patterns of acetabular fractures: are the USA and China comparable? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 472 (11), 3332–3337 (2014).

Giannoudis, P. V., Grotz, M. R., Papakostidis, C. & Dinopoulos, H. Operative treatment of displaced fractures of the acetabulum. A meta-analysis. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 87 (1), 2–9 (2005).

Shen, L., Ye, K., Tang, J. & An, Z. Comparative study of the 3D morphological differences in associated both-column acetabular fractures between elderly and young adults. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 145 (1), 169 (2025).

Lundin, N., Berg, H. E. & Enocson, A. Complications after surgical treatment of acetabular fractures: a 5-year follow-up of 229 patients. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 33 (4), 1245–1253 (2023).

Stavrakakis, I. M. et al. Sciatic nerve injury after acetabular fractures: a meta-analysis of incidence and outcomes. Eur. J. Trauma. Emerg. Surg. 48 (4), 2639–2654 (2022).

Huang, J. H. et al. Surgical treatment for both-column acetabular fractures using pre-operative virtual simulation and three-dimensional printing techniques. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 133 (4), 395–401 (2020).

Krappinger, D., Freude, T., Stuby, F. & Lindtner, R. A. Acetabular fractures in geriatric patients: epidemiology, pathomechanism, classification and treatment options. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 144 (10), 4515–4524 (2024).

McCormick, B. P. et al. Treatment modalities and outcomes following acetabular fractures in the elderly: a systematic review. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 32 (4), 649–659 (2022).

Cavalié, G. et al. Clinical and radiological outcomes of antegrade posterior column screw fixation of the acetabulum. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 108 (4), 103288 (2022).

Boni, G., Pires, R. E., Sanchez, G. T. & Giordano, V. Antegrade posterior column screw fixation for acetabular fractures: it’s time to standardize the surgical technique. Injury 54 Suppl 6, 110579 (2023).

Caviglia, H. et al. Percutaneous fixation of acetabular fractures. EFORT Open. Rev. 3 (5), 326–334 (2018).

Bozzio, A. E., Johnson, C. R. & Mauffrey, C. Short-term results of percutaneous treatment of acetabular fractures: functional outcomes, radiographic assessment, and complications. Int. Orthop. 40 (8), 1703–1708 (2016).

Levin, S. et al. Clinical outcomes in prone positioning for percutaneous fixation of posterior column acetabular fractures. Eur. J. Trauma. Emerg. Surg. 48 (5), 3721–3727 (2022).

Starr, A. J., Borer, D. S. & Reinert, C. M. Technical aspects of limited open reduction and percutaneous screw fixation of fractures of the acetabulum. Oper. Tech. Orthop. 11 (3), 218–226 (2001).

Li, J. et al. Establishment of fluoroscopy views and standardized procedure of percutaneous magic screw insertion for acetabulum fractures. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 19 (1), 332 (2018).

Sun, Y. et al. Study of anatomical parameters and intraoperative fluoroscopic techniques for transiliac crest anterograde lag screws fixation of the posterior column of the acetabulum. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18 (1), 697 (2023). Published 2023 Sep 18.

Öztürk, V. et al. Is the both column fixation corridor a universally valid and consistent fixation pathway in pelvic and acetabular surgery? J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 20 (1), 590 (2025). Published 2025 Jun 16.

Öztürk, V. et al. Fluroscopy-assisted transiliac antegrade lag screw placement technique in both columns of acetabulum: A novel procedure. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 110 (5), 103872 (2024).

Öztürk, V. et al. Is the innovative both column screw fixation technique a Biomechanical game-changer in the fixation of acetabular posterior column fractures? Int. Orthop. 49 (9), 2271–2280 (2025).

Peng, S. et al. Morphometric measurement of the patella on 3D model reconstructed from CT scan images for the Southern Chinese population. Chin. Med. J. 127 (1), 96–101 (2014).

Zarate-Kalfopulos, B., Romero-Vargas, S., Otero-CaMara, E., Correa, V. C. & Reyes Sanchez, A. Differences in pelvic parameters among Mexican, Caucasian, and Asian populations. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 16 (5), 516–519 (2012).

Arima, H. et al. Differences in lumbar and pelvic parameters among African American, Caucasian and Asian populations. Eur. Spine J. 27 (12), 2990–2998 (2018).

Wagner, D. et al. Critical dimensions of trans-sacral corridors assessed by 3D CT models: relevance for implant positioning in fractures of the sacrum. J. Orthop. Res. 35 (11), 2577–2584 (2017).

Ahrend, M. D. et al. Development of generic Asian pelvic bone models using CT-based 3D statistical modelling. J. Orthop. Translat. 20, 100–106 (2019).

Jung, G. H., Lee, Y., Kim, J. W. & Kim, J. W. Computational analysis of the safe zone for the antegrade lag screw in posterior column fixation with the anterior approach in acetabular fracture: A cadaveric study. Injury 48 (3), 608–614 (2017).

Feng, X. et al. Definition of a safe zone for antegrade lag screw fixation of fracture of posterior column of the acetabulum by 3D technology. Injury 47 (3), 702–706 (2016).

Attias, N. et al. The use of a virtual three-dimensional model to evaluate the intraosseous space available for percutaneous screw fixation of acetabular fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 87 (11), 1520–1523 (2005).

Yu, K. et al. The placement of percutaneous retrograde acetabular posterior column screw based on imaging anatomical study of acetabular posterior column corridor. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 17 (1), 492 (2022).

Mu, W. D., Wang, X. Q., Jia, T. H., Zhou, D. S. & Cheng, A. X. Quantitative anatomic basis of antegrade lag screw placement in posterior column of acetabulum. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 129 (11), 1531–1537 (2009).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YS JC performed the experiments and wrote this manuscript. YS JC XL FL collected and analyzed the data. YS FL revised and finalized the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qilu Hospital (Qingdao), Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University (Protocol No: KYLL-KS-2024073), and all participants in the study signed an informed consent form in writing.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Y., Chen, J., Li, X. et al. Safe passage analysis for both column screw fixation technique in posterior column acetabular fractures. Sci Rep 15, 44932 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29543-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29543-9