Abstract

Zika Virus (ZIKV) is a mosquito-borne virus that can cause serious health problems, including birth defects and neurological complications. Unfortunately, there are no antivirals currently approved for its treatments. In this study, we tested a library of 348 chemical compounds to find potential candidates that could block ZIKV infection. Seven compounds showed strong antiviral activity in laboratory experiments. Among them, Cephalotaxine, Docusate Sodium, and Saikosaponin B2 were the most effective. However, Docusate Sodium may pose safety risks at higher doses, and Saikosaponin B2 has poor solubility, which could limit its use as a drug. To better understand how these compounds work, molecular docking was employed to predict interactions between the active compounds and two important ZIKV proteins: NS5 and the NS2B-NS3 protease complex. The docking results supported the in vitro findings, revealing strong binding affinities, particularly for Saikosaponin B2. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed stable binding of Saikosaponin B2 and Aloperine to NS5, with Saikosaponin B2 showing greater stability and consistent interactions. Drug-likeness and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) analysis indicated that while some compounds possess favorable pharmacokinetic properties, others may require structural optimization. Overall, this study identifies several promising lead compounds for further preclinical development and highlights the utility of integrating in vitro screening with computational modeling to accelerate antiviral drug discovery against ZIKV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a mosquito-borne flavivirus that has emerged as a significant global health concern due to its association with severe neurological complications, including microcephaly1 in newborns and Guillain-Barré syndrome2 in adults. It was first found in 1947 in the Zika Forest of Uganda and has since spread throughout Africa, Asia, the Americas, and the Pacific Islands, establishing its pandemic potential. A major outbreak in Brazil in 2015 led the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare it a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) in 20163, following the rise in microcephaly cases in ZIKV-affected regions. Even though cases have declined recently, ZIKV is still a “silent virus” with the potential for resurgence, as noted by recent reports from the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization4 and the Pan American Health Organization5. There are currently no approved antiviral treatments or vaccines to mitigate the virus’s impact on public health. However, due to the limited commercial interest in emerging arboviruses like ZIKV, traditional antiviral development pipelines are often resource- and time-intensive. This creates a critical gap in timely therapeutic discovery.

To address this challenge, drug discovery for ZIKV and related viral infections requires a multidisciplinary approach that combines computational and experimental strategies to efficiently identify and assess potential therapeutic candidates. Combining in vitro and in silico techniques has proven to be a powerful strategy for accelerating drug development. High-throughput screening (HTS) enables the systematic evaluation of large chemical libraries to identify compounds with antiviral potential, whereas in silico approaches, such as molecular docking, can show how these compounds interact at a molecular level. These complementary methodologies not only accelerate drug discovery but also help in the development of targeted antiviral therapies.

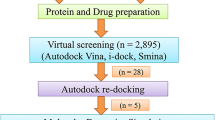

In our study, we took an integrated approach by combining high-throughput screening (HTS) and in silico analysis to repurpose existing drugs. We tested a diverse antiviral compound library of 348 compounds for their ability to inhibit ZIKV replication in vitro. These compounds target key viral enzymes, including HCV protease, HIV protease, integrase, and reverse transcriptase. The library consists of structurally diverse, bioactive compounds, including several FDA-approved agents. The most promising hits from our screening were then further subjected to in silico analyses, including molecular docking against key ZIKV non-structural proteins, active-site prediction, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and drug-likeness assessments. While in vitro screening identified active compounds, molecular docking was used as a complementary tool to analyze potential interactions with key viral proteins and help prioritize candidates for further research. Since molecular docking provides only static binding predictions, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were additionally performed to account for protein flexibility and validate the stability of ligand binding. We focused particularly on the ZIKV NS5 and NS2B-NS3 proteins6 for molecular docking because they play crucial roles in viral replication and pathogenicity, making them attractive therapeutic targets. For MD simulations, NS5 was selected as the representative target, with Saikosaponin B2 chosen as the top-binding compound and Aloperine as a representative moderate binder with protonation-dependent behavior. These selections enabled us to compare stable versus variable binding profiles under dynamic conditions.

This transition from in vitro to in silico techniques offers a time- and cost-efficient approach. By focusing on the most promising candidates early in the process, this strategy minimizes the need for unnecessary animal and clinical testing, thereby reducing both development time and cost. Moreover, integrating biological efficacy with computational predictions provides a comprehensive understanding of each compound’s therapeutic potential.

Results

Identification of hit compounds from high-throughput screenings

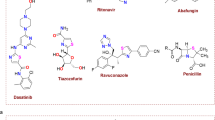

The high-throughput screening of 348 compounds identified seven promising candidates with significant protective effects against ZIKV-induced cell death, as determined by the crystal violet assay (Fig. 1). Inhibition was assessed in triplicate using crystal violet staining. Retention of staining was interpreted as an indication of viable cells and protection from virus-induced cytopathic effects. In all screening experiments, Remdesivir and DMSO were included as positive and negative controls, respectively. Compounds were classified based on the number of wells showing stain retention: strong inhibition (100%) if all three wells remained stained, intermediate inhibition (~ 67%) if two wells were stained, and weak inhibition (~ 33%) if only one well was stained. The absence of staining in all wells was classified as no inhibition (0%). This scoring system follows established CPE-based antiviral screening protocols7. Based on this classification, Cephalotaxine, Docusate Sodium, and Saikosaponin B2 were identified as strong inhibitors, NGI-1 and Aloperine as intermediate inhibitors, and AEBSF-HCl and Probucol as weak inhibitors. The strong inhibitors—Cephalotaxine, Docusate Sodium, and Saikosaponin B2—were selected for further in vitro evaluation due to their consistent antiviral activity observed across screening rounds. While this method provides a semi-quantitative assessment and does not yield statistical significance, it allows for reliable and comparative evaluation of antiviral activity across tested compounds due to the use of replicates and controls. We acknowledge this limitation and propose the inclusion of quantitative follow-up assays in future studies.

High-throughput screening was performed to identify compounds that protect Vero cells from ZIKV-induced cytopathic effect. Vero cells were infected with Zika virus (100 TCID₅₀/well) and treated with 348 antiviral compounds at a final concentration of 10 µM in 96-well plates. After 6 days of incubation, cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet to assess protection from ZIKV-induced cytopathic effect (CPE). Wells retaining crystal violet stain indicated viable, protected cell monolayers, while unstained wells reflected virus-induced cell death. Compounds were categorized based on the number of replicate wells protected: strong (3/3 wells stained), intermediate (2/3), weak (1/3), or inactive (0/3).

Effective concentration and cytotoxicity of hit compounds

EC₅₀ and CC₅₀ assays were performed in triplicate for reproducibility on the three strongest inhibitors identified. Cephalotaxine showed a sharp transition from 0% inhibition at 25µM to 100% inhibition at 50 µM (Fig. 2a). The EC₅₀ was estimated to be approximately 37.5µM based on midpoint interpolation, but a confidence interval could not be calculated due to the binary nature of the response. Its CC50 exceeded 300µM, resulting in a selectivity index (SI) of approximately 7.5, indicating a favorable therapeutic index and a moderate safety margin.

Docusate Sodium exhibited an EC₅₀ of 2.35µM (95% CI: 1.55–3.56µM) and a CC₅₀ of 8.19µM (95% CI: 6.42–10.44µM), yielding a selectivity index (SI) of 3.49 (estimated range: 1.80–6.73) (Fig. 2b). This suggests a narrow therapeutic window and raises concerns regarding potential cytotoxicity at effective doses. Saikosaponin B2 showed inconsistent antiviral activity across replicates, likely due to solubility issues, which limit its further evaluation in subsequent assays.

Dose–response effects of Cephalotaxine and Docusate Sodium were evaluated in ZIKV-infected Vero cells. Vero cells were infected with ZIKV (100 TCID₅₀/mL) and treated with increasing concentrations (0.2–100µM) of each compound for 6 days. Cell viability was assessed using crystal violet staining, and dose–response curves were generated from triplicate data.

-

a.

Cephalotaxine showed a binary inhibition profile, with no antiviral activity observed at concentrations ≤ 25µM and complete inhibition at ≥ 50µM, resulting in an estimated EC₅₀ of ~ 37.5µM.

-

b.

Docusate Sodium demonstrated a sigmoidal dose–response curve, with an EC₅₀ of 2.35µM (95% CI: 1.55–3.56µM) and a CC₅₀ of 8.19µM (95% CI: 6.42–10.44µM), yielding a selectivity index of 3.49.

Antiviral activity and cytotoxicity are represented by blue and red curves, respectively.

Receptor-ligand preparation and active site prediction

The receptor proteins (Zika virus NS5 protein, PDB ID: 5WZ3; NS2B-NS3, PDB ID: 5GXJ) and ligands retrieved from PubChem were successfully prepared for docking (Fig. 3a). Following the initial preparation using UCSF Chimera, the structures were further optimized using SwissDock’s ‘Prepare Protein’ and ‘Prepare Ligand’ tools. The optimized receptor and ligand files were then used for docking simulations by AutodockVina via SwissDock web server.

Active site prediction was conducted using SCFBio, which identified key binding pockets in the NS5 protein and NS2B-NS3. The predicted binding sites were used to define the docking grid parameters, with the grid box centered at XYZ coordinates 42.652, 10.301, 73.434 Šfor NS5 (Fig. 3b) and at -10.382, 33.219, -40.330 Šfor NS2B-NS3 (Fig. 3c) with the size of 30 ų. All compounds were docked with a sampling exhaustivity of 16, while Saikosaponin B2 was docked with an exhaustivity of 8 due to its high molecular weight.

Receptor-ligand preparation, active site prediction, and docking grid definition for ZIKV NS5 and NS2B-NS3 proteins. (a) Prepared receptor protein structures (ZIKV NS5 and NS2B-NS3) and ligand structures used for molecular docking studies. (b) Active site prediction of ZIKV NS5 protein using SCFBio, highlighting key binding pockets and docking grid placement. The docking grid was centered at XYZ coordinates (42.652, 10.301, 73.434 Å). (c) Active site prediction for the ZIKV NS2B-NS3 complex. The docking grid for NS2B-NS3 was defined at XYZ coordinates (-10.382, 33.219, -40.330 Å). Both docking grids had dimensions of 30 ų.

Molecular docking analysis

Molecular docking was performed to evaluate the binding affinities and interaction profiles of seven selected hit compounds against two critical Zika virus (ZIKV) targets: the NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (PDB ID: 5WZ3) and the NS2B-NS3 protease (PDB ID: 5GXJ). The binding energies ranged from − 5.02 to − 9.06 kcal/mol for NS5 (Table 1) and − 5.47 to − 8.13 kcal/mol for NS2B-NS3 (Table 2), with Saikosaponin B2 demonstrating the strongest affinities for both targets (–9.06 kcal/mol and − 8.13 kcal/mol, respectively).

Against NS5, Cephalotaxine showed a moderate binding energy of − 6.35 kcal/mol, forming one hydrogen bond with SER341 and additional interactions with SER476 and ASP343. Docusate Sodium had a relatively weak binding energy (–5.02 kcal/mol) and, although it formed hydrogen bonds with ASN290 and GLY282 and several hydrophobic interactions, it displayed an unfavorable negative–negative steric clash with ASP343. Saikosaponin B2 demonstrated high binding energy (–9.06 kcal/mol) and formed four hydrogen bonds (SER476, SER390, ASP344, VAL284), though it lacked hydrophobic or π interactions. NGI-1 bound with an energy of − 6.72 kcal/mol, with no hydrogen bonds but stabilizing hydrophobic interactions at SER476, CYS389, TYR287, and ILE477. AEBSF-HCl had a binding energy of − 5.40 kcal/mol, forming a hydrogen bond with GLN283, but exhibited an unfavorable donor–donor interaction between THR286.A and TYR287.A. Probucol, with a relatively high binding affinity (–7.27 kcal/mol), formed no hydrogen bonds, relying instead on hydrophobic interactions with TYR287 and TRP475. Aloperine bound with − 6.26 kcal/mol, forming a hydrogen bond with TRP475 and additional hydrophobic contacts.

For the NS2B-NS3 protease, Saikosaponin B2 again showed the best binding (–8.13 kcal/mol), forming hydrogen bonds with PRO104.A, TYR294.B, and TYR314.B, and other interactions with ARG31.A and LEU292.B. Docusate Sodium bound with − 5.47 kcal/mol, forming a hydrogen bond with TYR314.B and several stabilizing contacts including ALA134.A, VAL38.A, and ARG31.B. Probucol had a strong affinity of − 8.00 kcal/mol, forming hydrogen bonds with GLN37.A and TYR314.B, as well as hydrophobic interactions with key residues. NGI-1 showed moderate binding (–6.55 kcal/mol) without hydrogen bonding, but engaged in multiple polar and hydrophobic interactions. Aloperine had a binding affinity of − 6.00 kcal/mol, forming hydrogen bonds with TYR314.B and LEU292.B. AEBSF-HCl displayed a binding energy of − 5.84 kcal/mol, with a hydrogen bond to PRO133.A, but was affected by an unfavorable donor–donor clash between GLY135.A and THR136.A. Lastly, Cephalotaxine showed poor binding (–6.18 kcal/mol) with no hydrogen bonds and only weak hydrophobic contacts, indicating limited interaction with this protease.

In summary, Saikosaponin B2, Probucol, and Aloperine demonstrated the most favorable binding characteristics across both viral targets. Compounds like AEBSF-HCl and Docusate Sodium displayed specific steric clashes or unfavorable interactions that may compromise their stability in the active site. Cephalotaxine, despite moderate binding to NS5, showed minimal interaction with NS2B-NS3, suggesting limited dual-target potential.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted to investigate the binding characteristics of two antiviral agents, Saikosaponin B2 and Aloperine, against the NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (PDB: 5WZ3). Both ligands remained within the binding pocket throughout the simulation, although Aloperine exhibited slightly greater positional changes compared to Saikosaponin B2, likely due to its smaller size. Relative to the initial docking pose of Saikosaponin B2, the ligand formed additional hydrogen bonds with Lys119, Glu173, Tyr287, Asp344, Cys389, and His478, while losing interactions with Asp344 and Ser476. Furthermore, the ligand established an additional π-sigma interaction with Tyr287 and hydrophobic interactions with Arg161, Phe165, and Val284, enhancing its stabilization within the pocket (Fig. 4a-c). For Aloperine, the ligand formed a salt bridge with Asp344 alongside a hydrogen bond, while losing its interaction with Trp475. Additional van der Waals interactions with surrounding residues including Tyr287, Cys389, and Ile477 contributed to its stability in the pocket (Fig. 4d-f). These MD simulation results suggest a shift in binding mode due to structural adaptations during the simulation. RMSD profiles demonstrated that both ligands remained stably throughout the simulation trajectory, with Saikosaponin B2 exhibiting lower positional fluctuations compared to Aloperine, consistent with its larger and more complex molecular structures (Fig. 4g). RMSF analysis revealed localized flexibility within loop regions, particularly among residues surrounding the binding pocket, where Saikosaponin B2 induced greater stabilization relative to Aloperine (Fig. 4h). These findings highlight the potential of Saikosaponin B2 as a more stable antiviral candidate.

Computational models of Saikosaponin B2 and Aloperine with NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. (a–c) Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation model of Saikosaponin B2 bound to NS5 RNA polymerase (PDB: 5WZ3). (a) Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation model with stabilized interactions in the binding pocket. (b) 2D diagram of (a), highlighting key residues Lys119, Glu173, Tyr287, Asp344, Cys389, His478 and Tyr287. (c) Overlay of the initial docking pose (gray white) and the MD simulation pose (ligand: cyan; protein: blue). (d–f) Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation model of Aloperine bound to NS5 RNA polymerase (PDB: 5WZ3). (d) Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation model with stabilized interactions in the binding pocket. (e) 2D diagram of (d), emphasizing interaction with Asp344. (f) Overlay of the initial docking pose (gray white) and the MD simulation pose (ligand: yellow; protein: yellow). (g–h) Root mean square deviation (RMSD) and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) values are presented for NS5 RNA polymerase residues, comparing apo state (gray), Aloperine-bound (orange), and Saikosaponin B2-bound (blue). (g) Saikosaponin B2 exhibits slightly lower RMSD values compared to Aloperine, with averages of 3.87 ± 1.41 Å and 3.94 ± 0.90 Å, respectively (2.92 ± 0.94 Å for apo form). (h) The overall fluctuations were reduced in the ligand-bound systems compared to the apo form. Saikosaponin B2 exhibited lower fluctuations across most residues relative to Aloperine, indicating enhanced stabilization through more extensive binding interactions.

Drug-likeness and oral bioavailability of hit compounds

Evaluating the drug-likeness and oral bioavailability of candidate molecules is a critical step in the early stages of drug development, as compounds with poor pharmacokinetic profiles often fail during clinical translation. One of the most widely used criteria to assess drug-likeness is Lipinski’s Rule of Five (RO5), which predicts oral bioavailability based on physicochemical properties such as molecular weight (≤ 500 Da), hydrogen bond donors (≤ 5), hydrogen bond acceptors (≤ 10), and lipophilicity (LogP ≤ 5). A compound is considered to have acceptable drug-like characteristics if it does not violate more than one of these rules8. As summarized in Table 3, Cephalotaxine, Docusate Sodium, NGI-1, AEBSF-HCl, and Aloperine complied with RO5, exhibiting no more than one violation each. In contrast, Saikosaponin B2 and Probucol exceeded RO5 criteria, with three and two violations respectively, suggesting potential challenges in oral absorption and bioavailability. Similar violations have been reported for natural products or complex polyphenolic structures that often fall outside RO5 despite bioactivity9,10.

To further evaluate oral drug-likeness, bioavailability radar plots were generated using SwissADME. These radars offer a visual assessment of six key properties: lipophilicity (LIPO), size (SIZE), polarity (POLAR), solubility (INSOLU), flexibility (FLEX), and saturation (INSATU)11. As shown in Fig. 5, Cephalotaxine, NGI-1, AEBSF-HCl, and Aloperine fit well within the optimal bioavailability range, indicating favorable drug-like characteristics. Docusate Sodium met five criteria but exceeded the flexibility threshold, which may influence its binding affinity or metabolic stability12.

Saikosaponin B2 showed deviations in polarity and molecular size, consistent with prior observations that saponins often exhibit poor membrane permeability due to their large, highly polar structures13. This high polarity may hinder its ability to cross lipid membranes, despite strong in vitro efficacy. Probucol’s partial data availability (LIPO and INSATU only) limited comprehensive evaluation, although the compound’s high lipophilicity and low saturation suggest poor solubility and bioavailability, which aligns with earlier pharmacokinetic findings14.

ADMET properties of hit compounds

The results of ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) shown in Table 4 are computed using pkCSM webserver15. ADMET properties play significant roles in the early stage of drug discovery and development, as high-quality drug candidates must possess both sufficient efficacies against the therapeutic target and appropriate ADMET properties at a therapeutic dose16. Regarding absorption, all compounds showed a range of water solubility values, with most compounds having moderate solubility. The water solubility values ranged from − 2.087 to -3.759 log mol/L, suggesting that most compounds may have reasonable solubility. Among these, Cephalotaxine, NGI-1, and Aloperine exhibited high intestinal absorption, with percentages of 93.72%, 95.18%, and 93.14%, respectively, indicating favorable oral bioavailability. However, Docusate Sodium and Saikosaponin B2 demonstrated low intestinal absorption (22.24% and 25.425% respectively), which could limit its effectiveness as an oral drug. In terms of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate activity, Saikosaponin B2, Probucol, and Aloperine were identified as P-gp substrates, suggesting that they may face efflux at the cell membrane, potentially limiting absorption. Caco-2 permeability values were also assessed, with Cephalotaxine, NGI-1, and AEBSF-HCl showing high permeability (log Papp values of 1.221, 1.383, and 1.234, respectively), while Saikosaponin B2 showed poor permeability (-0.237), which could result in limited absorption.

For distribution, the volume of distribution (Vd) ranged from − 0.662 (Docusate Sodium) to 1.299 (Aloperine). Cephalotaxine, NGI-1, and Aloperine exhibited favorable distribution, while Docusate Sodium had low distribution in tissues. Regarding blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, Cephalotaxine and Aloperine showed good BBB penetration (0.19 and 0.913, respectively), suggesting they could cross the blood-brain barrier, while other compounds had very low permeability, indicating poor potential for CNS penetration. The CNS permeability of compounds also mirrored these trends, with Cephalotaxine and Aloperine showing more favorable CNS permeability, while the rest exhibited lower CNS penetration potential. The fraction unbound in human plasma was generally moderate across compounds, with NGI-1 showing the highest value (0.471), which could be an indicator of better target engagement.

For metabolism, Cephalotaxine, Docusate Sodium, NGI-1, and Probucol were identified as CYP3A4 substrates, suggesting that these compounds would be metabolized by the CYP3A4 enzyme, potentially leading to drug-drug interactions. None of the compounds were inhibitors of major CYP enzymes such as CYP2D6, CYP2C19, or CYP1A2, except AEBSF-HCl, which is an inhibitor of CYP1A2, suggesting a lower likelihood of metabolic inhibition for other compounds. Regarding excretion, the total clearance values varied significantly, with Docusate Sodium showing the highest clearance (2.111 log ml/min/kg) and Probucol showing the lowest clearance (-0.103 log ml/min/kg), indicating that compounds with low clearance may stay longer in the body, which could affect their pharmacokinetic profile.

In terms of toxicity, Cephalotaxine, NGI-1, and AEBSF-HCl were predicted to be hepatotoxic, while the other compounds showed no significant hepatotoxic effects. Saikosaponin B2 and Probucol exhibited potential hERG II inhibition, which could result in cardiac toxicity. Furthermore, AEBSF-HCl was predicted to have AMES toxicity, indicating mutagenic potential. The oral rat acute toxicity (LD50) values were relatively high across the compounds (2.168–2.959 mol/kg), suggesting that all compounds are relatively non-toxic in terms of acute oral toxicity. Lastly, Aloperine showed potential skin sensitization, while the others were not predicted to cause skin sensitization.

Overall, the ADMET analysis provides valuable insights into the pharmacokinetic properties and potential safety concerns of the hit compounds, guiding their future investigation for development into therapeutic agents.

Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the potential of various compounds for the development of effective antiviral agents against the Zika virus (ZIKV). By combining high-throughput screening, in vitro evaluation, molecular docking analysis, drug-likeness assessments, and ADMET profiling, we have identified several promising hit compounds that may serve as leads for therapeutic development.

The high-throughput screening (HTS) of 348 compounds identified seven hit compounds with varying degrees of antiviral activity against ZIKV, as assessed by the crystal violet assay. Among these, three compounds—Cephalotaxine, Docusate Sodium, and Saikosaponin B2—were classified as strong inhibitors based on their ability to protect cells from ZIKV-induced cytotoxicity. The antiviral activity of Cephalotaxine was consistent with a previously reported EC50 value of 40 μm17, validating our screening results. Docusate Sodium exhibited strong antiviral effects (EC50 = 2.35 µM), though its low CC50 (8.19 µM) indicates a narrow therapeutic window, raising concerns about cytotoxicity at higher concentrations. Saikosaponin B2 showed inconsistent antiviral activity across replicates, likely due to solubility or permeability issues. Two compounds—NGI-1 and Aloperine—classified as intermediate inhibitors, while Probucol and AEBSF-HCl showed weak antiviral effects. Although weaker hits may lack independent therapeutic potency, they still hold potential as scaffolds for structural refinement or as adjuncts in combination therapies.

Molecular docking studies were conducted against two key ZIKV proteins: NS5 and NS2B-NS3. To validate the reliability of our docking results, we included known antiviral compounds as positive controls. Sofosbuvir is an FDA-approved nucleotide polymerase inhibitor that has previously been shown to have anti-ZIKV activity. Similarly, Niclosamide is a broad-spectrum antiviral that interferes with the interaction between the viral NS3 protease and its cofactor NS2B, effectively blocking protease function in flaviviruses. Our docking results found that both compounds showed strong binding affinities (− 7.8 kcal/mol), similar to previously reported values of − 7.4 kcal/mol for Sofosbuvir18, and − 7.5 kcal/mol for Niclosamide19, supporting the validity of our docking approach. In contrast, negative controls Acyclovir and Amantadine, selected from our compound library due to their lack of reported anti-ZIKV activity, showed significantly weaker binding energies (− 5.4 and − 5.3 kcal/mol, respectively), further confirming the specificity of our results. Among the hits, Saikosaponin B2 exhibited the strongest binding to both proteins, suggesting it may be a promising candidate for further optimization. It formed hydrogen bonds with key residues such as SER476, SER390, VAL284, and ASP344 in NS5, and PRO104.A, TYR294.B, and TYR314.B in NS2B-NS3, along with stabilizing hydrophobic interactions. Docusate Sodium, while exhibiting low affinity (− 5.02 and − 5.47 kcal/mol), engaged in hydrogen bonding with both targets, including ASN290 and GLY282 in NS5 and TYR314 in NS2B-NS3, indicating meaningful interaction. Cephalotaxine formed a hydrogen bond with SER341 of NS5 and showed moderate binding. NGI-1 demonstrated moderate docking scores driven primarily by hydrophobic contacts. Probucol also showed strong binding to NS2B-NS3 (− 8.00 kcal/mol), supported by hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions. Aloperine displayed selective, modest interactions, while AEBSF-HCl showed the weakest binding and steric clashes with active site residues.

MD simulations supported the docking predictions by demonstrating that both ligands remained bound to NS5 throughout the trajectory. Saikosaponin B2 not only retained key contacts but also formed additional stabilizing interactions, resulting in lower positional fluctuations compared to Aloperine. The protonation-dependent behavior of aloperine further highlighted the importance of ionization states and structural plasticity of NS5 in ligand accommodation. These findings strengthen the docking results and point to Saikosaponin B2 as the more promising candidate for further development.

Drug-likeness was evaluated using Lipinski’s Rule of Five. Cephalotaxine, NGI-1, AEBSF-HCl, and Aloperine, adhered to the rule, suggesting favorable oral bioavailability. Saikosaponin B2 and Probucol violated multiple parameters, including size, polarity, and flexibility, indicating possible challenges in membrane permeability and absorption. While these violations suggest a need for further optimization, they do not exclude these compounds from being viable leads for development.

ADMET properties revealed that Cephalotaxine, NGI-1, and Aloperine showed favorable absorption and BBB permeability. In contrast, Docusate Sodium and Saikosaponin B2 exhibited poor intestinal absorption and low permeability, suggesting further modifications for effective oral administration. Most compounds were identified as substrates of the CYP3A4 enzyme, raising the possibility of drug-drug interactions. AEBSF-HCl showed predicted hepatotoxicity and mutagenicity. Saikosaponin B2 and Probucol raised concerns about hERG II inhibition, which may affect cardiac safety.

These toxicity predictions align with known data of structurally related compounds. Cephalotaxine’s analogue, harringtonine, is associated with hepatotoxic effects such as elevated liver enzymes and jaundice20. Saikosaponin B2’s saponin structure is known to disrupt membranes and may affect ion channels like hERG21. Probucol is experimentally linked to QT prolongation via increased degradation of hERG protein22.

Despite strong docking scores of Saikosaponin B2, its poor in vitro reproducibility and unfavorable ADMET profile limit its immediate potential. The high polarity and large molecular size of Saikosaponin B2 point to potential challenges in absorption and cellular uptake, as shown in SWISSADME bioavailability radar. However, several optimization strategies could be explored to enhance its drug-likeness. These include deglycosylation to reduce polarity and molecular weight, chemical modification of the triterpenoid backbone to improve lipophilicity, or advanced drug delivery approaches such as nanoparticle encapsulation or liposomal formulations23,24. Such modifications may improve its pharmacokinetic properties while retaining antiviral activity, making it a viable lead for further development.

Although docking offers insight into binding potential, it does not replicate the cellular environment. Biophysical methods like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) could further confirm binding interactions and affinity in future studies.

This study has several limitations. First, while high-throughput screening was conducted in triplicate and across three independent rounds, formal assay validation metrics such as Z′-factor calculation were not implemented. The screen relied on a single positive control (Remdesivir) and a negative control (DMSO), and additional standard antivirals were not included. Second, the classification of hit compounds into strong, intermediate, and weak inhibitors was based on semi-quantitative scoring of cytopathic effect (CPE) using crystal violet staining, a method commonly used in early-stage antiviral screening. However, this approach lacks statistical validation and should be supplemented with more quantitative assays in future studies. In addition, docking predictions were not confirmed experimentally through enzymatic assays or biophysical binding analyses such as Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Microscale Thermophoresis (MST). Third, drug-likeness and ADMET properties were predicted in silico using SwissADME and pkCSM tools; no in vivo pharmacokinetic or toxicity data are yet available. Future work will aim to address these limitations by incorporating additional validation steps, mechanistic assays, and in vivo analyses to support lead optimization.

In conclusion, this study identifies several promising antiviral candidates against ZIKV through integrated screening and computational analysis. Cephalotaxine, NGI-1, and Aloperine demonstrated favorable efficacy and pharmacokinetics. Saikosaponin B2 showed stable binding in molecular dynamics simulations and Docusate Sodium, despite some limitations, may benefit from structural or formulation-based optimization. These findings provide a foundation for the continued development of targeted antiviral therapies for ZIKV.

Materials and methods

Cells and virus

Vero cells (ATCC® CCL-81™), derived from the kidney epithelial cells of the African green monkey, were used for Zika virus (ZIKV) propagation and antiviral testing. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (w/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution at 37 °C and 5% CO2 atmosphere to ensure optimal growth.

The ZIKV strain used in this study was the MR766 strain, a prototype Zika virus originally isolated in Uganda, obtained from the National Culture Collection for Pathogens, Republic of Korea. Virus propagation was carried out in Vero cells using DMEM supplemented with 3% FBS and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution under optimal conditions of 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Compounds sources

An initial antiviral screen was performed using the Antiviral Compound Library (96-well format, #CAS: L7000-Z399195, Selleckchem, Houston, USA), which includes a diverse collection of 348 compounds. Each compound was tested at a final concentration of 10µM for initial screening against ZIKV. For positive control, Remdesivir (CAS No.: 1809249-37-3) obtained from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, USA) was used in a concentration gradient of 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, and 3.125µM, prepared in duplicates. Remdesivir was co-administered with the virus to assess its inhibitory effect on viral replication under comparable conditions.

The three hit compounds (strong inhibitors), Cephalotaxine (CAS No.: 24316-19-6), Docusate Sodium (CAS No. : 577-11-7), and Saikosaponin B2 (CAS No.: 58316-41-9), were obtained from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, USA) and diluted in DMSO to a final concentration of 7.5mM according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

High-throughput screening for in vitro evaluation of antivirals against Zika virus

The initial phase of this study involved a high-throughput screen of 348 antiviral compounds to identify potential inhibitors of ZIKV replication in Vero cells. One day prior to infection, cells were seeded at a density of 1.2 × 10⁶ cells per pate in 96-well plates and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO₂. Compounds were tested at a final concentration of 10µM, simultaneously with ZIKV infection at a dose of 100 TCID₅₀ per well.

After 6 days of incubation, cell viability was assessed using crystal violet staining. The assay was performed in triplicate, with Remdesivir and DMSO serving as positive and negative controls, respectively. Uninfected cell controls were included on each plate to establish baseline viability.

Due to time and resource constraints, additional standard antiviral controls and formal assay validation metrics, such as Z’-factor calculation, were not implemented. We acknowledge this as a limitation of the current study. Nevertheless, each compound was tested across three independent rounds to ensure reproducibility. Compounds that consistently protected cells from virus-induced cytopathic effects were classified as potential inhibitors and selected for further evaluation.

Cytopathic effect (CPE)-based scoring using crystal violet staining has been employed in several antiviral screening studies for its simplicity, scalability, and suitability for high-throughput formats. Although this is a semi-quantitative method, it enables effective prioritization of active compounds in primary screening. A similar CPE-based approach was recently used in a SARS-CoV-2 drug discovery protocol7.

Determination of effective and cytotoxic concentrations of hit compounds

The 50% effective concentration (EC50) and 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) values of only three strong inhibitors were determined using Vero cells cultured in 96-well plates. Vero cells were seeded at a density of 1.2 × 106 cells per plate one day before infection. Following this, serial dilutions of Cephalotaxine, Docusate Sodium, and Saikosaponin B2 (50µM-0.2µM) were prepared in DMEM and added to the monolayer of cells. At the same time, cells were infected with 100 TCID50/mL of ZIKV and incubated for 6 days at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Wells with virus infection and wells containing only cells were designated as virus control and cell control, respectively. For CC50 evaluation, cells not infected with the virus were exposed to serial dilutions of the antivirals Cephalotaxine, Docusate Sodium, and Saikosaponin B2, ranging from 50µM to 0.2µM. After an incubation period of 6 days, crystal violet was used to assess cell viability.

Nonlinear regression analysis (four-parameter logistic model) was used to calculate EC₅₀ and CC₅₀ values based on triplicate data. Confidence intervals (95%) were calculated from the log-transformed regression estimates. Cephalotaxine’s EC₅₀ was estimated manually as the midpoint between the lowest inactive and the lowest fully active concentration due to its binary dose-response pattern.

Druggable Zika virus target selection and ligand preparation

To identify druggable Zika virus targets, viral proteins were analyzed for their roles in replication and pathogenicity, focusing on non-structural (NS2B-NS3, NS5) proteins. The crystal structures of Zika Virus NS5 (PDB ID: 5WZ3) and Zika Virus NS2B-NS3 (PDB ID: 5GXJ) were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB)25. Under standard protocol, the protein structures were treated as receptors. Receptor preparation for docking was performed using the Dock Prep tool in UCSF Chimera26. The process included the removal of non-essential molecules (e.g., water), added hydrogens, assigned charges, and structure optimization. The prepared protein structures were further optimized using the ‘Prepare Protein’ tool in SwissDock27.

All 7 hit compounds from in vitro HTS studies were selected as ligands for further docking studies. These ligands were retrieved from PubChem, where 3D conformers were available for most compounds. For those without 3D structures, the 2D structures were converted into 3D models using OpenBabel28. The resulting 3D structures were then prepared using either the Dock Prep tool in UCSF Chimera, where hydrogen atoms were added, charges were assigned, and structures were optimized for docking or uploaded as SMILES strings for conversion and preparation directly on SwissDock. The SMILES were obtained from ChemSpider29 and saved for use in docking.

Active site prediction and molecular docking

Active site prediction for the ZIKV target proteins—NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (PDB ID: 5WZ3) and NS2B-NS3 protease (PDB ID: 5GXJ)—was performed using SCFBio30. The predicted active sites were then used to define the docking grid parameters. Grid center coordinates were set as follows: for NS5, X = 42.652, Y = 10.301, Z = 73.434 Å; for NS2B-NS3, X = -10.382, Y = 33.219, Z = -40.330 Å.

Moleclar docking was performed using AutoDockVina via the SwissDock web platform. Target proteins were prepared using the “Prepare Protein” tool, which removed heteroatoms and added polar hydrogens. Ligands were either optimized via the “Prepare Ligand” feature or uploaded as SMILES strings for conversion and protonation. The exhaustiveness parameter was set to 16 for all ligands except Saikosaponin B2, for which it was reduced to 8 due to its high molecular weight.

Docking poses were ranked based on their binding affinity (ΔG, kcal/mol), number and geometry of hydrogen bonds, and presence of favorable hydrophobic and π interactions. Unfavorable interactions such as donor–donor or negative–negative clashes were also considered during pose selection. For each ligand, the pose with the most favorable interaction profile—characterized by lower binding energy and optimal engagement with key active site residues—was selected for visualization and further analysis.

Interaction profiles of the selected ligand–protein complexes were analyzed using UCSF Chimera and Discovery Studio Visualizer. Hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, π–π stacking, electrostatic interactions, and any steric clashes were identified. Two-dimensional (2D) interaction diagrams were generated in Discovery Studio and compiled as Supplementary Figures S1–S14, covering ligand interactions with NS5 (S1–S7) and NS2B-NS3 (S8–S14).

Molecular dynamics simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed to investigate the binding stability and interaction profiles of protein complexes with two ligands: Saikosaponin B2 and Aloperine. The simulations were conducted using the NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (PDB: 5WZ3). Based on the reported sequence, the missing loop was modeled, and protein structure was prepared using the Prepare Protein module in Discovery Studio 2024 (Accelrys, Inc.) with the CHARMm forcefield, involving the addition of hydrogens and removal of water molecules from the active site. The protein-ligand complexes, derived from docking results, were prepared using the Discovery Studio 2024. Each complex was parameterized with the CHARMm force field and placed in an orthorhombic simulation box, ensuring a minimum distance of 7 Å between the solute and box edges. The systems were solvated with explicit TIP3P water molecules, and appropriate counterions were added to neutralize charges. Energy minimization was performed using Smart Minimizer algorithm, followed by heating protocol to reach 300 K. Equilibration was then carried out at a constant temperature (300 K) for 1 ns, and the final configurations were exported in Discovery Studio formats.

Production MD simulations were run for 1 ns under periodic boundary conditions using Discovery Studio 2024. Data were recorded every 2 ps, with long-range electrostatics handled by the Particle-Mesh Ewald (PME) method31. The systems were maintained in an NPT ensemble at a constant temperature (300 K) and pressure (1 atm) throughout the simulations.

Trajectory analyses were performed to evaluate the root mean square deviation (RMSD)32, root mean square fluctuation (RMSF)33, and key interaction profiles between NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (PDB: 5WZ3) and the ligands (Saikosaponin B2 and Aloperine). These simulations provided detailed insights into the comparative binding behaviors and interaction dynamics of the two ligands with proteins.

Drug-likeness and ADME/T profiling

ADMET analysis was performed on the seven hit compounds to evaluate their drug-likeness and pharmacokinetic properties. The physicochemical properties of these compounds were computed using tools like SwissADME11 and pkCSM15. These compounds were assessed for Lipinski’s “rule of five” criteria8, ensuring they had a molecular weight ≤ 500Da, fewer than 10 hydrogen bond acceptors, fewer than 5 hydrogen bond donors, and logP values ≤ 5. Additionally, their pharmacokinetic properties, including absorption, solubility, and partition coefficient, were predicted to assess their potential as oral drugs.

Data analysis and interpretation

EC50 and CC50 values were calculated using non-linear regression analysis of dose-response curves in GraphPad Prism 9. The docking results were visualized and analyzed using UCSF Chimera and Discovery Studio Visualizer to evaluate key ligand-protein interactions, including hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, and optimal binding conformations. ADMET analysis conducted using SwissADME and pkCSM evaluated physicochemical properties, pharmacokinetics, and compliance with Lipinski’s “rule of five.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included within this manuscript.

References

Rasmussen, S. A., Jamieson, D. J., Honein, M. A. & Petersen, L. R. Zika virus and birth defects — reviewing the evidence for causality. N Engl. J. Med. 374, 1981–1987 (2016).

Brasil, P. et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with Zika virus infection. Lancet 387, 1482 (2016).

Mehrjardi, M. Z. Is Zika virus an emerging TORCH agent? Virol. (Auckl). 8, 1178122X17708993 (2017).

Zika hasn’t. disappeared – here’s why it should stay on our radar. Gavi. https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/zika-hasnt-disappeared-heres-why-it-should-stay-our-radar (Accessed 2025).

Zika. a silent virus requiring enhanced surveillance and control. PAHO/WHO. https://www.paho.org/en/news/1-9-2023-zika-silent-virus-requiring-enhanced-surveillance-and-control (2023).

Feng, Y. Recent advances in the study of Zika virus structure, drug targets, and inhibitors. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1418516 (2024).

Ng, Y. L., Mok, C. K. & Chu, J. J. H. Cytopathic effect (CPE)-based drug screening assay for SARS-CoV-2. In SARS-CoV-2. Methods in Molecular Biology (eds Chu, J. J. H. et al.) vol. 2452, 379–391 (Humana Press, 2022).

Lipinski, C. A. et al. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 46, 3–26 (2001).

Veber, D. F. et al. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 45, 2615–2623 (2002).

Doak, B. C., Over, B., Giordanetto, F. & Kihlberg, J. Oral druggable space beyond the rule of 5: insights from drugs and clinical candidates. Chem. Biol. 21, 1115–1142 (2014).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7, 42717 (2017).

Waring, M. J. et al. An analysis of the attrition of drug candidates from four major pharmaceutical companies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 14, 475–486 (2015).

Xu, R., Ye, M. & Fan, G. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of saponins: novel strategies to improve their oral absorption. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 14, 89–95 (2016).

Hirayama, T. et al. Pharmacokinetics of probucol in hyperlipidemic patients. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 51, 548–554 (1992).

Pires, D. E. V., Blundell, T. L. & Ascher, D. B. PkCSM: predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 58, 4066–4072 (2015).

Guan, L. et al. ADMET-score – a comprehensive scoring function for evaluation of chemical drug-likeness. Medchemcomm 10, 148–157 (2018).

Lai, Z. Z., Ho, Y. J. & Lu, J. W. Cephalotaxine inhibits Zika infection by impeding viral replication and stability. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 522, 1052–1058 (2020).

Kumaree, K. K., Anthikapalli, N. V. A. & Prasansuklab, A. In silico screening for potential inhibitors from the phytocompounds of Carica papaya against Zika virus NS5 protein. F1000Research 12, 655 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Existing drugs as broad-spectrum and potent inhibitors for Zika virus by targeting NS2B-NS3 interaction. Cell. Res. 27, 1046–1064 (2017).

Synapse PatSnap. What are the side effects of harringtonine? PatSnap Synapse. https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-are-the-side-effects-of-harringtonine (2024).

Paarvanova, B., Tacheva, B., Savova, G., Karabaliev, M. & Georgieva, R. Hemolysis by saponin is accelerated at hypertonic conditions. Molecules 28, 7096. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28207096 (2023).

Shi, Y. Q. et al. Mechanisms underlying probucol-induced hERG-channel deficiency. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 9, 3695–3704. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S86724 (2015).

Hu, Q. R. et al. Methods on improvements of the poor oral bioavailability of ginsenosides: pre-processing, structural modification, drug combination, and micro- or nano-delivery system. J. Ginseng Res. 47, 694–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgr.2023.07.005 (2023).

He, Y. et al. Recent advances in biotransformation of saponins. Molecules 24, 2365. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24132365 (2019).

Berman, H. M. et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242 (2000).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Grosdidier, A., Zoete, V. & Michielin, O. SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W270–W277 (2011).

O’Boyle, N. M. et al. Open babel: an open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform. 3, 33 (2011).

Pence, H. E. & Williams, A. ChemSpider: an online chemical information resource. J. Chem. Educ. 87, 1123–1124 (2010).

Supercomputing Facility for Bioinformatics &. Computational Biology (SCFBio), IIT Delhi. Active Site Prediction Server. http://www.scfbio-iitd.res.in/dock/ActiveSite.jsp (Accessed 14 June 2025).

Huang, J. et al. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods. 14, 71–73 (2017).

Kroemer, R. T. et al. Assessment of docking poses: interactions-based accuracy classification (IBAC) versus crystal structure deviations. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 44, 871–881 (2004).

Dong, Y. W., Liao, M. L., Meng, X. L. & Somero, G. N. Structural flexibility and protein adaptation to temperature: molecular dynamics analysis of malate dehydrogenases of marine molluscs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 115, 1274–1279 (2018).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2021R1A2C2006961 and NRF-2020R1A5A2017476) and was conducted during the research year of Chungbuk National University in 2024.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B. and M.S.S: Conceptualization and Study Design, S.B. performed the high-throughput screening, antiviral assays, and molecular docking analysis, A.J. and B.K.K. assisted with in vitro assay development and data analysis. J.H.P., S.C.M., and J.R.L. contributed to compound preparation, virus propagation, and cytotoxicity testing. G.C.L., D.G.L., and S.H.A. supported in silico studies and ADMET profiling. S.C.S., G.M.K., and B.S.J. performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. S.B: Writing — Original draft preparation. S.C: Visualization. Y.H.B. and M.S.S: Writing— review and editing, Supervision. M.S.S: Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Batool, S., Chokkakula, S., Kim, B.K. et al. High-throughput in vitro screening and in silico analysis for Zika virus inhibitor identification. Sci Rep 15, 45501 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29585-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29585-z