Abstract

Comparative metabolomics may shed light on host immunity and biology in oral candidiasis (oral thrush). Untargeted metabolomic analyses were performed on oral rinses collected from 26 primary oral candidiasis patients (OT), 12 patients after antifungal treatment (AT), and 12 unaffected individuals (C). Host immune modulation metabolites against oral candidiasis, Candida virulence and antifungal properties were identified. The upregulation of C17 sphinganine, L-leucine, monoacylglycerol, phosphatidylethanolamine, and spermine, in OT and AT groups, highlights the role of host immunity in Candida clearance. The altered sphingolipid levels suggest disrupted membrane integrity and immune function, while dysregulated amino acid, purine, and glutathione metabolism reflect oxidative stress and inflammation. Antifungal metabolites, specifically dichloroacetate, 1-monopalmitin, and undecane-2-one, were significantly upregulated in the OT group; conversely, fatty acids (palmitic amide, linoleamide, stearamide, and pentadecanal) were downregulated. Metabolomic similarities between oral candidiasis and xerostomia were evident, with shared markers such as L-valine, L-leucine, D-proline and 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid. Increases in lipid metabolites, carboxylic acids, and amino acids, particularly L-leucine and hypoxanthine in patients upon resolution of oral candidiasis following antifungal treatment suggests fungal clearance, immune activation and recovery from oxidative stress. Some metabolites identified in oral candidiasis patients have reported roles in oral carcinogenesis, however, the findings remain observational and warrant further validation. Our results demonstrate that oral candidiasis is associated with distinct metabolomic alterations compared with healthy controls, and that antifungal therapy reshapes the oral metabolic profiles via complex host–microbiome–fungal metabolic pathways. The identification of oral candidiasis-associated metabolites also highlights their potential as non-invasive biomarkers and therapeutic targets for oral healthcare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oral candidiasis (commonly known as oral thrush) is an opportunistic infection caused by the overgrowth of Candida species, particularly Candida albicans, on the oral mucosa1. C. albicans is a clinically significant yeast that normally coexists harmoniously with resident oral microbiota2,3. Early diagnosis of oral candidiasis, often based on clinical examination of oral lesions, medical history, and assessment of risk factors, is particularly important for elderly and immunocompromised patients4. Current clinical classification of oral lesions broadly categorized oral candidiasis into primary and secondary forms. While primary oral candidiasis (including pseudomembranous, erythematous, and hyperplastic types) is confined to oral and perioral tissues, and may present as acute or chronic lesions, secondary oral candidiasis occurs as systemic candidal infection, involving dissemination beyond the oral region5,6,7. Laboratory confirmation of candidiasis can be performed through isolation of Candida yeasts on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) or CHROMagar Candida® agar8. Gram-stained oral smears, potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations, and Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)-stained histological sections enable the visualization of fungal hyphae and pseudohyphae, which are important diagnostic features of mucosal Candida infections9.

Dysbiosis—arising from disturbances in the host immune system, oral microbiota, or environmental conditions of the oral cavity—are significant predisposing factors for the development of oral candidiasis10. Emerging evidence suggests that C. albicans plays an active role in oral health and disease by modulating dynamic inter-kingdom fungal-microbiota interactions11. A recent study reported that human microbiota also interacts directly with the host through metabolites12. These host–pathogen interactions may result in stress conditions that often lead to metabolic reprogramming supported by host immune responses13.

Metabolomics is a large-scale systematic analysis (or ‘fingerprinting’) of metabolites or small molecules (< 1,500 Daltons) in the blood, urine, saliva, biological fluids, and tissues14,15. The oral metabolome is rich in low molecular weight molecules, including lipids, amino acids, vitamins, organic acids, thiols, carbohydrates, and their derivatives, which are produced by both the host and microbes. Some of these oral metabolites have been recognized as important indicators of certain physiological or pathological states of oral diseases, as reported for dental caries16, periodontal disease17, and oral cancer18. Notably, the metabolic plasticity of C. albicans has been reported to promote Candida virulence and survival to thrive in the complex host environment and adapt to the cellular responses of the host19.The metabolic interactions between innate immune cells and C. albicans yeast-hyphal morphogenesis, and modulation of host immune responses have been documented20.

The abundance or depletion of oral metabolites, including carbohydrates, amino acids, and lipids is essential for understanding the interconnection between immunometabolism and fungal infections14,17,20. A recent study of the oral metabolome have identified some significantly elevated metabolites, including tyrosine, choline, phosphoenolpyruvate, histidine, 6-phosphogluconate, octanoic acid and uridine monophosphate, in the unstimulated saliva of Japanese oral candidiasis patients21. The profiling of oral metabolites is also useful for non-invasive monitoring of patients’ immune status during HIV infection as reported by Ghannoum et al.22. Emerging evidence suggests Candida yeasts, particularly C. albicans, may contribute to the development of oral cancer via diverse mechanisms including carcinogenic metabolite production, immune modulation, biofilm formation, microbiome disruption, oncogenic pathway activation, and chronic inflammation23.

Despite these advances, only limited studies have investigated the oral metabolic profiles during oral candidiasis21. To the best of our knowledge, the metabolic alterations in oral samples following antifungal treatment remains largely unexplored. This represents a critical knowledge gap, as antifungal therapy not only targets fungal clearance but may also reshape the broader host–microbiome metabolic landscape, with potential implications for disease persistence, recurrence, and long-term oral health.

Here, we hypothesize that oral candidiasis is associated with distinct metabolomic alterations compared with healthy controls, and that antifungal therapy reshapes these metabolic profiles. Specifically, we propose that antifungal treatment influences host–microbiome–fungal metabolic pathways, thereby revealing biomarkers of disease activity and treatment response. By addressing this hypothesis, our study aims to (i) identify metabolites linked to fungal–host interactions, (ii) clarify the metabolic consequences of antifungal therapy, and (iii) explore possible associations between oral metabolites, Candida infection, and oral carcinogenesis.

Results

Subjects’ characteristics

Oral rinse samples collected as described in a previous study24 were processed for metabolomics analysis. A total of 26 patients, including 12 adults (18 – 64 years old) and 14 elderly patients (≥ 65 years old), who were clinically diagnosed with active oral candidiasis were recruited into the OT group (n = 26). The lesions were clinically classified as primary oral candidiasis based on the current classification of oral candidiasis5,6,7. The distribution of clinical variants of oral lesions (pseudomembranous, erythematous, hyperplastic, and Candida-associated lesions) is shown in Supplementary Table 1. Among these active oral candidiasis patients, 12 returned for oral reassessment two weeks after completion of antifungal treatment (AT group). In addition, 12 individuals who had no signs and symptoms of oral candidiasis were recruited as controls (C group).

A researcher-administered data collection form was used to record the sociodemographic details of study participants. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects, including lifestyle, oral health, clinical condition, and types of oral candidiasis lesion, have been reported previously24 where a significant association between oral candidiasis and xerostomia was demonstrated [Χ2(1) = 10.08, p < 0.001] (Supplementary Table 1).

Oral metabolome profiles of OT, AT, and C groups

Oral metabolites extracted from both supernatant and pellet fractions of oral rinse samples were analyzed by Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS). Oral metabolites exhibiting fold-change ≤ −1.5 or ≥ 1.5 and p-value of < 0.05 were considered significantly downregulated or upregulated, respectively. Oral metabolites that exhibited significant differences were predominantly detected in the supernatant fraction (n = 226) of the oral rinse samples, while only 37 metabolites were detected in the pellet fraction. In addition, 32 metabolites were found in both pellet and supernatant fractions (Table 1). Significant oral metabolites detected were predominantly lipids (51%), followed by amino acids, carboxylic acids, alkaloids, benzenes, carbohydrates, and others (Fig. 1a). Fatty acyls (FA, 40%) constituted the most predominant lipid components, followed by prenol lipids (17%) (Fig. 1b).

There were 41 significantly upregulated (p < 0.05) and 254 significantly downregulated oral metabolites (p < 0.05) in OT group compared with the C group. Comparison between the OT and AT groups revealed significant upregulation of 52 metabolites (p < 0.05) and downregulation of 243 metabolites (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, 55 metabolites were significantly upregulated, but 240 metabolites were significantly downregulated in the AT group compared with the C group (Supplementary Table 2).

Among OT samples from patients presenting with different clinical variants of oral candidiasis lesions, the highest number of oral metabolites was detected in samples from patients with pseudomembranous candidiasis (287 metabolites), whereas the lowest number of oral metabolites was recorded in samples from patients with Candida-associated lesions, namely median rhomboid glossitis (143 metabolites) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 3). A total of 95 oral metabolites were shared amongst all types of oral candidiasis patients, as determined based on the “modified 80% rule”25,26 (i.e. the core oral candidiasis metabolome).

The metabolomic profiling in this study showed the sharing of 232 oral metabolites among the three study groups (OT, AT, and C). Figure 3 is a Venn diagram showing the distribution of common and unique metabolites in each group. Some of the unique metabolites in the oral rinse samples of the OT group include FA (10-oxo-nonadecanoic acid, 14-methyl-8-hexadecen-1-ol, 15-methyl-octadecanoic acid, pipericine, sciadonic acid), sterol lipids (24-Nor-5β-chol-22-ene-3α,7α,12α-triol), polyketides (chamuvaritin), alkaloids (10-Deoxysarpagine), benzenes (phenyltoloxamine), and N,N,N',N'-Tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (TMPD). On the other hand, benthamitin (polyketide), piperolein B (benzene), and Pro Arg Asp (organic amino compounds) were unique metabolites found in the oral rinse samples of the AT group.

Multivariate analysis of oral metabolites

Unsupervised PCA was performed to determine outliers, as well as the similarity, homogeneity, and trends in the overall patterns of oral metabolite profiles for the study groups27 (Fig. 4a,b). The score plot in (Fig. 4a) demonstrated a clear separation and distinct clustering for the OT (-100 > PC1 > 100 and -40 > PC2 < 30; blue), C (-125 > PC1 > 100 and PC2 < 60; green), and AT metabolites (PC1 < -50 and -125 > PC2 < -50; red), reflecting distinct uniqueness in the oral metabolome profiles of each study group. The AT oral metabolome profiles formed a distinct cluster compared with those of OT and C, suggesting a specific impact of antifungal treatment to the oral microbiome. On the other hand, the comparison of metabolites in all age groups (young, adult and elderly) revealed a wide clustering with a high mean Euclidean distance (i.e., tightest clustering). No distinct clustering was observed among the adult and elderly age groups, indicating minimal effect on the overall composition of oral metabolites (Fig. 4a).

Three dimensional PCA plots illustrated: (a) metabolite differences in active oral candidiasis (OT group, blue), antifungal treated (AT group, red) and unaffected control (C group, green); (b) metabolite differences in OT samples from patients with various oral manifestations (n = 26); and (c) metabolite differences in OT samples with/without xerostomia and controls. Axes represented the principal components of the PCA, with numbers indicating the percentage of variance explained by each component. OT + X: OT group with xerostomia (n = 13, green); OT-X: OT group without xerostomia (n = 13, blue).

Figure 4b shows the distribution of the oral metabolites among OT samples from patients with various clinical presentations (i.e., angular cheilitis, denture stomatitis, erythematous candidiasis, median rhomboid glossitis, and pseudomembranous candidiasis). The contribution ratio of PC1 was 41% higher than that of PC4 (5.2%). Interestingly, dispersing and non-specific clustering plot patterns of oral metabolites were noticeable for OT samples from patients with different clinical manifestations of oral candidiasis. The PCA score plot in (Fig. 4c) revealed a clear separation and close clustering of the oral metabolome profile of OT samples from patients with and without xerostomia and C, suggesting a clear influence of xerostomia on oral metabolome composition. Most of the oral metabolites in OT samples from patients with xerostomia and OT samples from patients without xerostomia converged at similar parts of the score plots. These distributions were indicative of the similarity between oral samples from OT group irrespective of xerostomia status.

Differentially expressed metabolites

Lipid metabolism

Significantly expressed (p < 0.05) oral metabolites in each study group were presented by heat map analysis (Table 2, Supplementary Figs. 1–6). Clustering of the metabolites was conducted using Pearson correlation analysis (coefficient value, |r|> 0.9). Comparison between the groups (OT vs. C and AT vs. C) showed significant downregulation of sphingolipids (i.e., ceramides, sphinganine, phytosphingosine, and xestoaminol C) in the OT and AT groups, except for C17 sphinganine, which was significantly upregulated in the OT and AT groups as compared to the C group, respectively (p < 0.05). The significant downregulation of sphingolipids (i.e., ceramides, sphinganine, and phytosphingosine) was also recorded in OT group, specifically for those presenting with xerostomia (pseudomembranous and erythematous candidiasis, and denture stomatitis) as compared to OT samples without xerostomia (median rhomboid glossitis and angular cheilitis) (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5).

Hierarchical non-clustering heat map analysis of oral sphingolipid metabolites demonstrated metabolite abundances across i) study groups: OT (green), AT (purple), and C (orange); ii) xerostomia status: yes (light blue), no (green), and unknown (blue); and iii) types of oral candidiasis. The magnitude of association coefficients between metabolites was indicated by color intensity, with blue representing decreasing trends, and red representing increasing trends.

Significantly elevated levels of FA (including undecane-2-one, 10-oxo-nonadecanoic acid, 20-oxo-heneicosanoic acid, 11,12-dihydroxy arachidic acid, 11-amino-undecanoic acid, and R-nostrenol) and lower levels of cerotic acid(d3), 2-ethyl-dodecanoic acid, and digitoxic acid were detected in OT and AT groups as compared with C (p < 0.05). In addition, eicosanoyl-EA, nonanoic acid, 3-amino-, (R)-, and 17-phenyl trinor Prostaglandin E2 serinol amide were significantly upregulated in the AT group following antifungal treatment and in the C group, compared with OT (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, regardless of the variation in the clinical manifestations of oral candidiasis, dodecanamide, linoleamide, palmitic amide, and stearamide were significantly downregulated in OT samples from patients with xerostomia, whereas undecane-2-one, 2,4-Dimethyl-2-pentacosenoic acid and 2-Methyl-2-hexacosenoic acid were significantly upregulated in OT samples from patients with xerostomia (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Additionally, the expression of most glycerolipids and glycerophospholipids (i.e., phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidylinositol (PI) and phosphatidylserine (PS)) metabolites were widely scattered. Numerous oral metabolites were significantly downregulated in the OT group compared with C and AT (p < 0.05) except for glycerolipids [i.e., 1-Monopalmitin and monoacylglycerol (MG(0:0/18:0/0:0)] and glycerophospholipids [i.e., phosphatidic acid (PA(O-20:0/16:0) and phosphoethanolamine (PE(17:2(9Z,12Z)/22:6(4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z,19Z))], which were significantly upregulated in the OT group compared with C (p < 0.05). However, following antifungal treatment (AT group), PE(19:0/0:0), PG(20:5(5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z)/0:0), and TG(18:1(9Z)/22:1(13Z)/22:3(10Z,13Z,16Z))[iso6] were significantly upregulated (p < 0.05). Interestingly, most glycerolipids and glycerophospholipids were significantly downregulated regardless of the clinical manifestation of oral candidiasis and xerostomia status (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Similarly, emmotin A, limonoate, and monocyclic botryococcane (phenylpropanoids) as well as 6-deoxyerythronolide B and 4,5-di-O-methyl-8-prenylafzelechin-4beta-ol (polyketides) were significantly upregulated in the AT group compared with OT and C (p < 0.05). On the other hand, stigmatellin Y, trans-resveratrol-d4, clausarinol, and 4-hydroxycoumarin were significantly downregulated in both OT and AT groups compared with C (p < 0.05). In addition, chapelieric acid methyl ester and monocyclic botryococcane were significantly upregulated in OT (i.e., angular cheilitis, denture stomatitis, and median rhomboid glossitis) samples from patients with xerostomia compared with OT samples from patients without xerostomia (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 3). Sterol lipids, i.e., eplerenone and estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,6 beta,17 beta-triol triacetate were significantly upregulated in the OT compared with C (p < 0.05), especially in MRG patients with xerostomia (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Amino acid metabolism

Amongst amino acid metabolites, a significant upregulation of D-proline, L-leucine, and L-valine was exclusively detected in the OT samples (p < 0.05), regardless of patients’ xerostomia status and the clinical manifestation of oral candidiasis, whereas a significant downregulation of L-valine was noted in the AT group compared with the C group (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Carbohydrate metabolism

Compared with C group, a significant upregulation of dichloroacetate, a carboxylic acid metabolite, was detected in both OT and AT (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, a significant downregulation of 4-Methylaminobutyrate was noted in the OT samples from patients with denture stomatitis, whereas a significant upregulation was noted in the AT group (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 6). Comparison between OT and AT oral metabolites in this study shows a significant downregulation of most carbohydrate metabolites (i.e., armillarin, L-rhamnulose, netilmicin, and chivosazole E) (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Alkaloids

Hypoxanthine and symlandine (alkaloids) were significantly downregulated in the OT samples in this study but upregulated in the AT group (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Metabolites associated with active primary oral candidiasis and antifungal activity

Table 3 is a list of significantly upregulated and downregulated oral metabolites which have been reported to play a role either in Candida growth, interaction with host, pathogenicity28 or the modulation of host immune response against Candida yeasts19,29. Seven metabolites (C17 sphinganine, D-proline, L-leucine, monoacylglycerol, phosphatidic acid, phosphatidylethanolamine and spermine) were significantly upregulated in both OT and AT groups compared with C (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, L-valine was significantly upregulated in the OT group but downregulated in the AT group compared with C (p < 0.05), respectively, as shown in (Fig. 6a). In addition, following antifungal treatment, sphinganine, and spermidine were significantly upregulated in the AT group compared with the C (p < 0.05). This study also observed a significant downregulation of ceramide, phytosphingosine, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylserine, and triacylglycerol in both OT and AT groups, compared with C (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6b).

Differential expressions of oral metabolites across study groups. (a) Seven metabolites were significantly upregulated in both the OT and AT groups compared with controls, while one metabolite (valine) showed opposing regulation between OT and AT relative to controls; (b) Twenty metabolites were significantly downregulated in both OT and AT compared with controls, while five metabolites exhibited opposite trends (downregulated in OT but upregulated in AT).

Nine significantly differentially expressed oral metabolites identified in this study have been reported to possess antifungal properties against Candida yeasts (Table 4). Three metabolites, i.e., dichloroacetate, 1-monopalmitin, and undecane-2-one, exhibited a significant upregulation in the OT group, while a significant downregulation of linoleamide, palmitic amide, stearamide, oleamide, cyclohexylammonium, and isolimonic acid was observed in the OT group as compared to C (p < 0.05; Fig. 7).

Interestingly, following antifungal treatment (AT vs C), a significant upregulation of lipid metabolites (i.e., emmotin A, eicosanoyl-EA, and limonoate), carboxylic acids (i.e., 4-Methylaminobutyrate), and alkaloids (i.e., hypoxanthine and symlandine) was noted in the AT group (p < 0.05; Fig. 8), corresponding with a significant downregulation of amino acids (L-valine), glycerolipids (monoacylglycerol and phosphatidylethanolamine), and amine (spermine) (p < 0.05; Table 4).

Significant upregulation of lipids (17-phenyl trinor Prostaglandin E2 serinol amide, Eicosanoyl-EA, Limonoate, and Hypoxanthine), carboxylic acids (Emmotin A, 4,5-Di-O-methyl-8-prenylafzelechin-4beta-ol and 4-Methylaminobutyrate) and alkaloid (Symlandine), in the AT group compared with controls following antifungal treatment.

Metabolic pathway analysis

In this study, metabolic pathway enrichment and topology analyses from all discriminant metabolites were systematically performed to identify the most relevant metabolic pathways based on pathway impact and adjusted p-value for each pathway30. The increase in the impact value and the significance of these metabolic pathways with the occurrence of active oral candidiasis reflects the stepped-up exacerbation in metabolic dysregulation of oral candidiasis.

Mapping of the annotated oral metabolites onto KEGG pathways identified the functional role of metabolites associated with active oral candidiasis. All metabolic pathways (ninety pathways) that were identified in OT, C, and AT groups and the associated oral metabolites are summarized in the supplemental Table S4. Figure 9 shows the pathway analysis plot (a) and the enrichment analyses (b) of oral metabolites comparing different study groups (OT vs. C, AT vs. C, and OT vs. AT), highlighting specific pathways associated with active oral candidiasis. Similar metabolic pathway diagrams were observed across all study groups, as the pathways generated through MetaboAnalyst analysis reflected the involvement of shared metabolites common to all groups.

Pathway (a) and enrichment (b) analyses of oral metabolites across all study groups. (a) Pathways identified by over-representation analysis (ORA) were visualized by circles, with the circle size indicating pathway impact (arbitrary scale). Circle color denoted unadjusted p—values (y-axis) from enrichment analysis: red, p < 0.075; orange, p < 0.1, yellow, p < 0.2. The x-axis indicated pathway impact (based on topology analysis), and the y-axis indicated pathway enrichment. Larger and darker nodes represented pathways with more hits, higher impact, and greater enrichment.

Table 5 shows the metabolic pathways that were significantly enriched in all study groups. Metabolic pathways with impact value > 0.1 or- log (p) > 10 are considered the most relevant pathways involved in the conditions under study. Sphingolipid metabolism; valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis; arginine and proline metabolism; beta-alanine metabolism; glutathione metabolism; phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis; valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation pathways exhibited significant difference (p < 0.05) between OT group and AT/C, suggesting that these pathways were significantly altered during oral candidiasis and following antifungal treatment. Among these pathways, sphingolipid metabolism, glycerolipid metabolism, and glycerophospholipid metabolism are associated with lipid metabolism; while another eight pathways were involved in various amino acid metabolisms, i.e., valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis and degradation; phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis; arginine and proline metabolism; tyrosine metabolism, D-amino acid metabolism, beta-alanine metabolism and pantothenate and Coenzyme A (CoA) biosynthesis, and purine metabolism (impact = 0.016), which is involved in nucleotide metabolism.

The pathway analyses also highlighted the enrichment of the following oral metabolites in OT, AT, and C groups (Supplementary Table 4 b):-

-

(i)

Sphinganine and phytosphingosine in sphingolipid metabolism;

-

(ii)

L-valine and L-leucine, in valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis and degradation pathways; and L-valine in pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis pathway;

-

(iii)

Spermidine and spermine in beta alanine and glutathione metabolisms;

-

(iv)

D-proline in the arginine and proline metabolisms;

-

(v)

4-Hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid, which is associated with phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis and ubiquinone and other terpenoid-quinone biosynthesis pathways;

-

(vi)

Phosphatidylethanolamine in Glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis pathway.

Discussion

The oral cavity is an ecological niche exhibiting complex and dynamic interactions among salivary components, host immune factors, resident oral microbiota, and opportunistic pathogens31. Changes in the oral metabolome during microbial interactions or corresponding host defense can provide important insights on the biological processes affecting oral candidiasis18,27. Our study highlights key metabolite classes—including lipids, amino acids, polyamines, and glycerophospholipids—that participate in fungal–host interactions, antifungal responses, and potentially carcinogenesis (Table 6).

Lipid metabolism and sphingolipids

Oral lipid metabolites have been shown to have association with the modulation of host responses to Candida pathophysiology during active oral candidiasis (Table 6). The critical role of lipid metabolism in host immune responses against fungal pathogens has been widely reported75,76. Host sphingolipids are essential regulators of immune response against Candida infection33,76, while fungal sphingolipids contribute to pathogenicity and modulation of fungus–host interactions32,38. As phagocytosis of C. albicans requires an intact sphingolipid biosynthetic pathway77, impairment in the host sphingolipid metabolism has been associated with insufficient clearance of Candida infection36. The breakdown of sphingolipids can alter signaling complexes localized within lipid rafts, leading to aberrant neutrophil functions and inflammatory responses, via the release of bioactive molecules, including ceramide, sphingosine, and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), a precursor of phytosphingosine39. S1P receptors activate lymphocyte egression from lymphoid organs, triggering immune response, especially humoral immunity39,40. The immunomodulatory effects of sphingosines eventually lead to the disruption of microbiota and activation of the host defense mechanism33. In our study, ceramides were downregulated during oral candidiasis, while phytosphingosine levels decreased after antifungal therapy (Table 6). The downregulation of ceramides may reflect rapid degradation of ceramides and activation of host immune responses, which could lead to microbial dysbiosis in the host. On the other hand, phytosphingosine reduction post-treatment may suggest a gradual reduction in ceramide degradation and restoration of immune homeostasis following clearance of Candida infection36.

The enrichment of sphinganine and phytosphingosine in sphingolipid metabolism hints at their involvement in the phagocytic function and resolution of inflammation in both host innate and adaptive immune responses77,78. Altered sphingolipid profiles could therefore serve as biomarkers for infection status and treatment response, with early detection potentially enabling preclinical diagnosis of oral candidiasis or underlying immunocompromised states.

Amino acid metabolism

In this study, several amino acids metabolic pathways, including arginine/proline, valine/leucine/isoleucine, alanine, glutathione, and aromatic amino acids—were found to be enriched in oral candidiasis, with notably elevated L-leucine levels observed in oral samples of patients following antifungal therapy (Table 3). Amino acids can affect host physiology by serving as sources of nitrogen and carbon, providing energy for various cell types (e.g., lymphocytes, fibroblasts, and enterocytes)41,46. Dysbiosis in oral microbiota, for instance, in periodontitis, can lead to protein degradation due to increased host protease activity resulting from tissue degradation in the oral cavity42. Free amino acids (e.g., leucine) play essential roles in the activation, differentiation, and rapid proliferation of T cells through mTORC1 signaling79, especially Th1 and Th17 cells, which is important for the clearance of Candida infections43,46. Specific amino acids, such as L-leucine and L-valine, may serve as early indicators of mucosal immune dysregulation or candidiasis-related inflammation.

Polyamines

An elevation of spermine and spermidine was demonstrated in oral samples of antifungal-treated patients in this study. Both polyamines have been correlated with key cellular processes including apoptosis, proliferation, differentiation, metabolism, signal transduction, homeostasis, regulation of gene and protein synthesis, and cell repair functions49,50,80,81,82. Spermine plays an essential role in maintaining the host-microbiome interface by co-modulating NLRP6 inflammasome signaling83, promoting epithelial IL-18 secretion, alteringt cytokine production via augmented IL-10 production, and the suppression of IL-12 p40, T-helper (Th)1 cytokines, and interferon-γ84. These signals are translated to antimicrobial responses to maintain stable microbial homeostasis80,81. The elevated levels of spermine and spermidine in oral samples of patients after antifungal treatment suggest recovery, and clearance of Candida infection. Given their consistent post-treatment increase, spermine and spermidine could serve as markers of treatment response and mucosal healing.

Glycerophospholipids

Downregulation of phosphatidylserine (PS) was observed in oral candidiasis, whereas phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) was upregulated in patients after antifungal therapy. PE, a product generated from the decarboxylation of PS, is a metabolic-related membrane glycerophospholipid involved in the synthesis of glycerophosphocholine (GPC) and promotion of GPC cycling62,85. In this study, the downregulation of PS in oral candidiasis patients may be due to the dysregulated biosynthetic pathway of glycerophospholipids75 or oral candidiasis-induced host cell disruption8. PE upregulation has been reported to promote the function of glucose transporter 3 (GLUT3), and mediate the cellular glucose uptake and glucose redistribution as a potential source of energy for cell survival86,87. These shifts highlight glycerophospholipids as possible non-invasive markers of immune restoration after treatment.

Antifungal metabolites

Antifungal metabolites in the oral cavity have been reported to inhibit Candida growth by acting against its cell wall, cell membrane, or hyphae55,88. In this study, fatty acids, glycerolipid, carboxylic acids, organonitrogen compound, and furan with antifungal properties89 were significantly expressed in the oral rinse samples of OT and AT groups compared with C group (Table 7).

Interestingly, undecane-2-one was upregulated in OT oral rinse samples and downregulated in AT group following the clearance of Candida infection (Table 4). Undecanoic acid, a saturated medium-chain fatty acid, has been reported as the most fungitoxic compound of the C7:0 – C18:0 acid series, affecting the expression of fungal virulence genes95. The upregulation of monoglycerides (specifically 1-monopalmitin) in the OT and AT groups compared to the C group suggests active antifungal activity against Candida96,97 attributing to their unique chemical structure (lipophilic acyl groups and two hydrophilic hydroxyls (-OH) groups of the glycerolipid molecule) and excellent amphiphilic properties98. The acyl group facilitates effective chemical binding with the lipid membrane, resulting in pore formation, membrane destabilization, and disintegration. The damage to the ionic balance causes cytoplasm disorganization, which eventually leads to the death of the fungi99.

Among the oral metabolites, dichloroacetate (DCA) has low toxicity and has been used to enhance the effects of antimicrobial and chemotherapy drugs100. In this study, DCA was upregulated in OT group, but downregulated in the AT group, suggesting its role in the clearance of oral candidiasis. Chapela et al.93 reported the synergistic effects of DCA with fluconazole on the growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Apart from phagocytosis and killing, monocytes and macrophages are responsible for the production of proinflammatory cytokines during Candida infection101. DCA has been reported to skew the glycolytic flux by enhancing pyruvate dehydrogenase activity, thereby decreasing the conversion of pyruvate into lactate and facilitates its entry into the TCA cycle. The glycolysis inhibition has been associated with the downregulation of C. albicans-induced IL-1β, TNFα, and IL-6 production in human monocytes102. Hence, in addition to antifungal property, DCA also exhibits an immunomodulatory effect via innate immune response in patients with oral candidiasis.

The downregulation of cyclohexylammonium, which is an ammonium ion resulting from the protonation of the amino group of cyclohexylamine, was noted in OT group. Cyclohexylamine, an inhibitor of spermidine synthase, has been shown to inhibit C. albicans growth in vitro, resulting in the depletion of cellular polyamines94. However, it is yet to be determined whether cyclohexylammonium also exhibits antifungal activity. Interestingly, isolimonic acid, a potent inhibitor of E. coli biofilm103, was downregulated in OT group, though was upregulated in AT group, after antifungal therapy. The downregulation of Escherichia coli biofilm inhibitors might not have any significant impact on host defense since Candida yeasts dominate the oral cavity during oral candidiasis. However, after antifungal therapy, as in the case of AT patients, its level was upregulated upon restoration of the oral microbiota to normal composition.

The antifungal properties of fatty acids and glycerolipids (e.g., 1-monopalmitin, undecanoic acid) suggest a protective host response104, potentially useful as diagnostic or prognostic markers. Additionally, DCA’s dual role (antifungal and immunomodulatory)91,105, makes it a promising adjunct therapy, especially for patients with resistant Candida or chronic inflammation.

Dysregulated metabolic pathways during oral candidiasis

The dysregulated metabolic pathways during oral candidiasis (Table 5, Fig. 9a) were further investigated using MetaboAnalyst 6.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/). Dysregulation of sphingolipid metabolism, particularly involving sphinganine and phytosphingosine has been implicated in cell membrane architecture maintenance, proliferation, and the lipid signaling cascade39,54,61,65. The activation of the lipid signaling pathway results in either the synthesis or release of ceramides from intracellular reserves35. The activity of ceramidases contributes to the formation of sphingosine (and sphingomyelin) that functions in an array of intracellular signaling or maintenance of cell membrane architecture106. Sphingomyelins and ceramides have been associated with apoptosis during nutrient starvation, while serving as important signaling molecules for cell differentiation and polarity35,107. Hence, targeting sphingolipid metabolism may help regulate the host immune response and improve Candida clearance, offering a potential non-antifungal approach for immunomodulatory therapy.

Other dysregulated metabolic pathways (Table 5, Fig. 9a) include those associated with valine, leucine, isoleucine, arginine, and proline whereby protein degradation provides an abundant source of nitrogen for cell proliferation108. In this study, higher levels of L-valine and L-leucine were identified from oral candidiasis patients, compared to controls (Table 3). Coincidentally, higher levels of gamma-glutamyl-leucine were also found in primary Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) patients109. Our finding also indicates the upregulation of D-proline (Table 3) in the arginine and proline metabolisms; and downregulation of 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid (Supplementary Table 2), which is a key intermediate in multiple KEGG pathways, including phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis; ubiquinone and other terpenoid-quinone biosynthesis; and isoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis. The dysregulation of these metabolites suggests shifts in amino acid metabolisms and mitochondrial functions including roles in electron transport and antioxidant defense110,111. Additionally, dysregulated amino acid metabolite profiles (e.g., glutamine, serine, tryptophan) observed in this study (Supplementary Table 2) may result from their utilization for fungal growth, immune modulation, and alteration of microbial activity. The inability of saliva to effectively control metabolic changes in oral microenvironment108,112, for instance, in the event of xerostomia, makes it a key predisposing factor in the development of oral candidiasis.

Beta alanine metabolites have been associated with high glycolytic activity, tumor aggressiveness in breast cancer, hypoxia, hypoglycemia, ischemia, and oxidative stress damage to neural cells113. Glutathione plays a central role in the cellular defense against free radicals, with its networks acting as a key regulator in inflammatory processes. In this study, increased levels of spermine in the oral rinses of oral candidiasis patients suggests elevated cellular energetic stress or oxidative stress (Table 5), as the metabolite has been linked to cell growth, metabolism, and stress responses,49,50,80,81,82. To mitigate this effect, cells utilize glutathione, which establishes a direct link between polyamine metabolism and antioxidant defense114. Taken together, these findings point to amino acid metabolism as a central metabolic signature of oral candidiasis. Targeting amino acid metabolic fluxes could be promising in disrupting oral candidiasis.

Impact of antifungal treatment

This study demonstrated significant increase of lipid metabolites (i.e., emmotin A, eicosanoyl-EA, and limonoate), carboxylic acids (i.e., 4-Methylaminobutyrate and L-alpha-amino-1H-pyrrole-1-hexanoic acid), alkaloids (i.e., hypoxanthine and symlandine), amino acids (i.e., L-leucine) and other class of metabolites (i.e., 3-isochromanone, 3-methylcyclopentene, 5-valerolactone, dihydro isorescinnamine, isolimonic acid, and metoprolol acid) following antifungal treatment (Supplementary Table 2). The upregulation of the lipid metabolites (i.e., emmotin A, eicosanoyl-EA, and limonoate) may reflect a breakdown of fungal cell components. Carboxylic acids are intermediates of central carbon metabolic pathways (including acetic, propionic, citric, and lactic acid) with potent antimicrobial potential115. Consistent with this, Gutierrez et al.116 found that cefoperazone treatment in mice led to increased levels of certain carboxylic acids, including hexanoic acid, which suppressed the growth and morphogenesis of C. albicans.

The higher level of L-leucine among individuals after antifungal intervention in this study may indicate tissue repair or activation of the immune response117, resulting from altered host and microbial metabolisms when bacteria re-colonize the ecological niche left vacant by Candida yeasts. Metabolomics analysis of fecal metabolites of clindamycin-treated mice showed increased concentrations of isoleucine for 21 days following clindamycin treatment, likely due to its metabolism being influenced by microbial species, whose levels are altered for an extended period following antibiotic treatment118. Meanwhile, fluconazole has been reported to affect the gut microbiota, increase the expression level of proinflammatory cytokines, and stimulate the innate immunity in mice119.

In summary, the antifungal treatment for oral candidiasis resulted in a metabolic shift, as evidenced by increases in lipid metabolites, carboxylic acids, and amino acids in the AT group. Additionally, elevated L-leucine and hypoxanthine levels observed in the AT group also reflect immune activation and recovery from oxidative stress after antifungal treatment, highlighting the dynamic interaction and metabolic response of the host and microbial community in the oral environment.

Exploration of metabolites associations with oral carcinogenesis

While several metabolites identified in oral candidiasis patients have been reported in the literature to play roles in oncogenic signaling or cellular stress responses, our findings are limited to observational associations. Longitudinal metabolomic monitoring of metabolites could be useful for early risk stratification of oral precancerous lesions or carcinogenesis in patients with chronic candidiasis. Literature reviews show that bioactive sphingolipids play an important role in the development, progression, metastasis, and drug resistance of various types of cancer120. Ceramides are central mediators of sphingolipid metabolism and signaling pathways, which play a dual role in cancer121. It can act as precursor that promotes tumorigenesis, as well as exert anti-tumor effects by promoting apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and autophagy121. Dysregulated ceramide metabolism is frequently observed in oral cancer and plays a role in promoting uncontrolled cancer cell growth and survival122. Increased levels of lipid byproducts may signal microbial stress responses during chronic inflammation. A significantly reduced level of fatty acid amides (including linoleamide, oleamide, palmitic amide, and stearamide) with potential antifungal and immunomodulatory roles123,124 was observed in the oral rinse of oral candidiasis patients in this study (Table 7). Research has shown that oleamide analogues, such as linoleamide, can induce apoptosis in human bladder, urinary, breast, and colon cancer cells, and exhibit antiproliferative, antiangiogenic, and antimetastatic properties124,125. A significant decrease in oleamide levels has also been reported in the saliva of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) patients126. While there is no direct evidence linking these fatty acid amides to cancer, dysregulation of lipids has been reported in cancer-associated inflammation and metabolism127.

Interestingly, amongst the oral metabolites detected in the oral candidiasis patients in this study, downregulation of sciadonic acid was observed. Sciadonic acid, a unique polyunsaturated fatty acid, has been detected in human breast cancer but not in adjacent healthy tissue128, however, there is no clear evidence linking it to tumor promotion or suppression. The present study also demonstrated a significant upregulation of salivary levels of spermine in the oral candidiasis patients (Table 3). Notably, elevated levels of polyamines (such as spermine) have been associated with tumor transformation and progression129 and various cancers130.

Metabolic reprogramming of amino acids is pivotal in cancer biology whereby cancer cells alter their metabolisms to support growth (through nutrient uptake and utilization), and to create a favorable environment for energy production, nucleic acid synthesis, signaling pathway regulation, redox balance maintenance, and epigenetic modifications131,132. The downregulation of 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid (Supplementary Table 2), which is associated with the dysregulation of phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis, was observed in oral candidiasis patients in this study. The observed metabolic changes, particularly involving amino acid biosynthesis—may indicate an underlying metabolic state that could predispose to cancer-related processes133. Additionally, dysregulation of proline metabolism134 has been reported to support cancer growth and survival, while beta-alanine metabolic pathway has been associated with tumor aggressiveness in breast cancer, hypoxia, and oxidative stress damage to neural cells135.

Known for its antifungal effects, 1-monopalmitin (Table 4) has demonstrated notable anticancer potential, especially in lung cancer, by suppressing cell proliferation, triggering apoptosis, and possibly influencing signaling pathways136. Coumarins (i.e., Hydroxycoumarin) also have gained interest for their potential use in photochemotherapy and other therapeutic applications in cancer treatment through the caspase dependent apoptosis137. Dichloroacetate exhibits promising anticarcinogenic activity, primarily due to its ability to target key metabolic enzymes, ion transport mechanisms, and oncogenic signaling pathways that govern cancer cell survival and proliferation138. Hydroquinidine, a naturally occurring ion channel blocker, demonstrates potent anti-cancer effects by suppressing cell growth, migration, and proliferation, while promoting apoptosis across multiple cancer cell lines, including lung, breast, and ovarian cancers139,140. Hence, understanding the anti-cancer potential of oral metabolic profiles not only broadens our insight into oral-systemic health connections but also opens new avenues for biomarker discovery and preventive strategies against oral and systemic cancers.

Clinical significance of the study

This study demonstrates that oral candidiasis is associated with distinct metabolomic alterations compared with healthy controls, accompanied by intricate underlying biological processes involving host immune responses, Candida virulence, and microbial interaction. Oral metabolites play a pivotal role in maintaining health within the oral ecosystem and can affect the pathogenic mechanism underlying oral candidiasis, through a diverse array of metabolites12. The metabolites identified in this study are associated specifically with host immune modulation against oral candidiasis, Candida virulence and antifungal activities19. While antifungals act directly by facilitating Candida clearance and indirectly, driving metabolic and microbial shifts in the oral region, the intervention has shown an impact on the progression and pathogenicity of oral candidiasis. This is reflected by the profiling of metabolites that are essential in reducing Candida burden, activating host immune responses, and promoting recovery from oxidative stress19,20. The identification of oral candidiasis-associated metabolites highlights their potential as valuable biomarkers for early detection, prognosis, and therapeutics. Elucidating these metabolic alterations not only deepens the insight into Candida pathophysiology but also supports the development of personalized, non-invasive diagnostic approaches that potentially improve clinical outcomes of oral candidiasis.

Limitation and future perspectives

This study identifies substantial differences in metabolomics profiles of oral rinse samples, with altered signatures of sphingolipids, amino acids, and other compounds in oral candidiasis patients. Significant changes in the metabolomics fingerprints observed in oral rinse samples in this study are primarily related to the overgrowth of Candida in the oral cavity and secondly, due to by-products of the host and oral microbiota. Hence, the metabolic shift may be associated with cross-kingdom interactions between host, fungi, and bacteria in different manners. However, the results should be interpreted with caution due to several limitations. The small sample size in this study may reduce statistical power and restrict the ability to capture the full biological variability inherent to metabolomic data. Additionally, the origin of oral metabolites might have derived from essential constituents of patients’ saliva, the breakdown of the host tissues, or the bacterial/fungal components. There is also limited evidence in the literature, especially from animal models or longitudinal dynamic microbiota studies that fully elucidates the roles of oral metabolites in metabolic recovery after antifungal treatment for oral candidiasis. Thus, the findings presented here should be considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating.

Future endeavors should be directed towards real time analysis of oral metabolomes in patients with larger sample size, different clinical variants of oral candidiasis, longitudinal assessment integrating the metabolic contribution of human and oral microbiota and host immunity, and comparisons between oral candidiasis and other fungi- or bacteria-related oral diseases, to refine the validity of metabolic biomarkers for the diagnostics of oral candidiasis. Additionally, further investigation should also explore other possible impairments to oral mucosae and/or salivary glands, and potential sources of metabolites in the oral cavity, such as exogenous compounds and sloughing from both host and oral microbiota. The mechanistic roles of specific oral metabolites in host-microbiota interactions during and after antifungal therapy also warrant further investigation by incorporating longitudinal microbiome-metabolome studies to clarify causal links and establish the clinical and translational significance of the metabolic changes.

Our study revealed a different metabolic profile compared to a previous study21 that analyzed salivary metabolome of patients diagnosed with oral candidiasis. This could be attributed to variances related to patients, such as diet, lifestyle, and exposure to medication and environment, as well as variations in experimental protocols, including sample type, size, processing procedures, and analytical platforms, which can affect the interpretation of metabolite expression levels.

Conclusion

Metabolomics analyses in this study revealed the diversity and complex interplay of oral metabolites in patients with active oral candidiasis and following antifungal therapy. These metabolites, some of which are known to play key roles in Candida pathophysiology and fungal-host interactions in oral candidiasis, help elucidate the mechanisms underlying dysbiosis and the dysregulation of metabolic pathways in oral candidiasis. Importantly, several of these metabolites—such as sphingolipids, amino acid derivatives, and polyamines—not only reflect host immune activity and Candida virulence but also show promise as early screening markers or therapeutic targets. Their consistent alterations in both infection and post-treatment phases highlight their potential utility in monitoring disease progression and treatment efficacy. These insights pave the way for the development of non-invasive, metabolite-based diagnostic/prognostic tools, and targeted therapies, ultimately contributing to more personalized and preventative approaches in oral healthcare.

Methods

Subjects’ recruitment and clinical evaluation

The study protocol was approved by the Universiti Malaya Medical Research Ethics Committee (UMREC no: 2019103–7894). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Subjects were recruited consecutively from patients attending the clinics and wards of Faculty of Medicine and Faculty of Dentistry, Universiti Malaya, from February 2020 until March 2021. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject before participation in this study. All data pertaining to the demographic, socioeconomic, and health status of the subjects were collected using a brief questionnaire. The inclusion criteria for subjects were: i) patients presenting clinical manifestations of oral candidiasis (OT group); ii) oral candidiasis patients who returned for a follow-up reassessment two weeks after completion of antifungal treatment (AT group); and iii) unaffected individuals with no clinical manifestation of oral mucosal disease (e.g., xerostomia) (Control, C group). The exclusion criteria were as follows, i) OT group: subjects who were on antifungal therapy in the preceding six weeks prior to the study; ii) AT group: subjects who did not come for follow-up treatment; and iii) C group: subjects who have clinical signs of oral mucosal diseases (e.g., xerostomia or reduced saliva production).

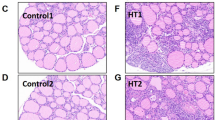

The age group of participants was categorized in accordance with the Department of Statistics, Malaysia, parameters i.e., young ages for 0 to 14 years, working ages for 15 to 64 years, and elderly for 65 years and above141. The malnutrition risk of patients was classified into either low (0 points), medium (1 point) or high risk (2 or more points) with the total scores ranging from 0 – 6 using the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool, taking into account the Body mass index (BMI) score (> 20 kg/m2: 0 point; 18.5—20 kg/m2: 1 point; < 18.5 kg/m2: 2 points), weight loss score (unplanned weight loss of 5%: 0 point; 5–10%: 1 point; > 10%: 2 points) and acute disease effect score (0 or 2)142. The diagnosis of xerostomia in patients for analysis was carried out based on a Clinical Oral Dryness Score, which categorized patients into 4 groups with the status of no (0–1), mild (2–4), moderate (5–7) or severe (8–10) xerostomia143,144. The status of the oral candidiasis in patients was confirmed by the attending physician using visual diagnosis and microscopic examination of the specimen with Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining9 in the diagnostic laboratory at the Faculty of Dentistry.

Sample collection

Subjects were advised to refrain from eating for at least 1 h prior to sample collection in the clinic, as described previously24. A dentist checked the oral hygiene of the subjects prior to sample collection to assess the manifestation of oral candidiasis lesions (presence of red sores, white spots, and sensation). Each subject was asked to gargle and rinse their mouth with sterile normal saline (0.9% solution of NaCl; Ain Medicare, Malaysia) for 1 min followed by expectoration into a sterile 50 mL centrifuge tube. Oral rinse samples (10 mL) were collected and immediately placed on ice. As sample preservation is important, the samples were always kept on ice during transportation to the laboratory. Samples were collected and transported to the laboratory for processing on the same day. All samples were stored at − 80 °C until further processing. Frozen samples were thawed and centrifuged (Daihan Scientific Co., Ltd, Korea) at 9,600 g for 10 min at 4°C145. Both pellet and supernatant fractions were used for metabolomics analysis.

Oral metabolites extraction

Oral metabolites from the supernatant of oral rinse samples was extracted according to leakage-free cold methanol quenching protocol146 with minor modification. Briefly, 40 mL of cold (-80 ºC) absolute methanol was added to a 10 mL supernatant sample (4:1, v/v)147. The mixture was vortexed for 5 min followed by incubation in ice for 1 h and centrifugation at 8,000 g, 4 ºC for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and left to dry in a Labconco Refrigerated Centrivap concentrator (Kansas City, MO, USA) at 4 °C. Quality control sample was prepared by pooling and mixing equal volumes of the extracted supernatant from each sample.

Oral metabolites were extracted from the cell pellet using a modified version of the chloroform–methanol extraction protocol148. Briefly, 300 µL of chloroform–methanol (2:1, v/v) was added to the cell pellet (3:1, v/v). The mixture was vortexed for 1 min followed by incubation at room temperature for 1 h. Next, to induce metabolites phase separation, chloroform (100 μL) and water (100 μL) were added followed by incubation at room temperature for 10 min, and centrifugation at 10,000 g at 4ºC for 10 min. The upper aqueous and lower organic phases were collected and dried at 4 °C in Labconco Refrigerated Centrivap concentrator (Kansas City, MO, USA).

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC–MS)

Chromatographic analysis was performed using an Agilent LC 1200 Series controlled by Agilent Mass hunter Workstation Acquisition (B.02.01). The separation was performed at 40 °C using Agilent ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 separation column 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm (Agilent Technologies SA, USA) with (A) 0.1% formic acid in water, (B) 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (ACN). The gradient was started from 0 – 36 min with increasing percentage of B from 5 to 95%, The LC condition was re-equilibrated for 12 min. The sample was reconstituted with 50 μL of mobile phase A:B (95:5, v/v), the injection volume was 2 µL and the flow rate was set at 0.25 mL/min.

The mass spectrometry was operated in electrospray ionization (ESI), positive mode of Accurate Mass 6520 6520 Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (Q-TOF). The capillary voltage of 4,500 V, nebulizer gas pressure (nitrogen) of 160 kPa, ion source temperature of 200 °C, dry gas flow of 7 L/minute at source temperature, and spectral rate of 3 Hz for MS1 and 10 Hz for MS2 were used. ESI conditions included spraying voltage, 3.0 kV; gas temperature, 300 °C; drying gas flow, 8 L/min; nebulizer pressure, 35 psig; VCap, 3500 V; fragmentor voltage, 175 V; and skimmer voltage, 65 V.

Data processing and statistical analysis

Patient-related factors (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, smoking, risk of malnutrition, usage of antimicrobial wash, denture usage, intake of topical/inhalational corticosteroid, antibiotic treatment, concurrent bacterial infection, and diabetes) in OT vs. C, AT vs. C and OT vs. AT subjects were assessed through the Pearson Chi-Square test (Supplementary Table 1).

The pellet and supernatant oral rinse samples collected from the subjects were combined and analyzed for detection and profiling of untargeted human and fungal metabolites in the oral cavity of oral candidiasis patients. Briefly, all acquired chromatograms were extracted and processed using MassHunter Qualitative Analysis software (version B.05.00) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Extraction of unknown features from raw data was carried out using the Molecular Feature Extraction (MFE) algorithm. The data generated was subsequently imported into the Mass Profiler Professional (MPP) software (version B.12.61) for binning, aligning, and creating a consensus for each feature. For normalization, entities were baselined to the median of all samples. Compound identification was done by querying the calculated neutral mass of each feature against the METLIN version 3 Personal Metabolite Database for matching compounds within a mass tolerance window of a maximum of 10 ppm and Molecular Formula Generation software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Identified compounds were eventually cross-referenced against the databases to confirm their occurrence in human metabolome database (HMDB), Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway database, PubChem compound database and LIPID MAPS® using exact molecular weights based on accurate mass, isotope ratios, abundances, and spacing with the removal of redundant molecular features. In metabolomics, there is an “80% rule” which states that variables with missing values in more than 20% of samples may be removed from the data analysis. Hence, to decrease the risk of reducing sample size and losing potential differential metabolites, “modified 60% rule” was proposed in this study so that metabolites can be excluded from the analysis when the proportion of non-missing elements are accounted for less than 60% among each study group but the metabolite is kept in the analysis if it has a non-zero value for at least 70% in the samples of any one study group25,26. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with an asymptotic p-value of 0.05 to determine the statistical significance between the three groups at a confidence interval of 95%, and metabolites were also compared between groups by fold change in relative intensity. The metabolic pathway analysis of potential biomarkers of oral candidiasis was executed using computational platform metabolomics pathway analysis (MetPA) in MetaboAnalyst 6.0 (www.metaboanalyst.ca) to determine the role of each oral metabolite and discover the changed pathways149 (Supplementary Table 2).

All demographic data collected were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26.0 computer software. Multivariate statistical analysis was performed to identify significant relevant oral metabolites which mostly discriminated against all tested groups. The data sets of samples were analyzed by ANOVA for comparison of the three study groups.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and/or its supplementary materials.

References

Millsop, J. W. & Fazel, N. Oral candidiasis. Clin. Dermatol. 34, 487–494 (2016).

Alrayyes, S. F. et al. Oral candidal carriage and associated risk indicators among adults in Sakaka. Saudi Arabia BMC Oral Health 19, 86 (2019).

Mun, M., Yap, T., Alnuaimi, A. D., Adams, G. G. & McCullough, M. J. Oral candidal carriage in asymptomatic patients. Aust. Dent. J. 6, 190–195 (2016).

Akpan, A. & Morgan, R. Oral candidiasis. Postgrad. Med. J. 78, 455–459 (2002).

Axéll, T., Samaranayake, L. P., Reichart, P. A. & Olsen, I. A proposal for reclassification of oral candidosis. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 84(2), 111–112 (1997).

Samaranayake, L. P. & Yaacob, H. B. Classification of oral candidosis. In Oral Candidosis (eds Samaranayake, L. P. & MacFarlane, T. W.) (Oxford: Wright, 1990).

Scully, C., El-Kabir, M. & Samaranayake, L. P. Candida and oral candidosis: a review. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 5(2), 125–157 (1994).

Lewis, M. A. O. & Williams, D. W. Diagnosis and management of oral candidosis. Br. Dent. J. 223, 675–681 (2017).

Davenport, J. C. & Wilton, J. M. A. Incidence of immediate and delayed hypersensitivity to Candida albicans in denture stomatitis. J. Dent. Res. 50(4), 892–896 (1971).

Wang, Y. Looking into Candida albicans infection, host response, and antifungal strategies. Virulence 6, 307–308 (2015).

Chin, V. K., Lee, T. Y., Rusliza, B. & Chong, P. P. Dissecting Candida albicans infection from the perspective of C. albicans virulence and omics approaches on host-pathogen interaction: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 1643 (2016).

Zhang, Y., Chen, R., Zhang, D., Qi, S. & Liu, Y. Metabolite interactions between host and microbiota during health and disease: Which feeds the other?. Biomed. Pharmacother. 160, 114295 (2023).

O’Neill, L. A., Kishton, R. J. & Rathmell, J. Guide to immunometabolism for immunologists. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 553–565 (2016).

Wang, J. H., Byun, J. & Pennathur, S. Analytical approaches to metabolomics and applications to systems biology. Semin. Nephrol. 30, 500–511 (2010).

Guijas, C., Montenegro-Burke, J. R., Warth, B., Spilker, M. E. & Siuzdak, G. Metabolomics activity screening for identifying metabolites that modulate phenotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 316–320 (2018).

Havsed, K. et al. Bacterial composition and metabolomics of dental plaque from adolescents. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, 716493 (2021).

Barnes, V. M. et al. Global metabolomic analysis of human saliva and plasma from healthy and diabetic subjects, with and without periodontal disease. PLoS ONE 9, e10518 (2014).

Ishikawa, S. et al. Identification of salivary metabolomic biomarkers for oral cancer screening. Sci. Rep. 6, 31520 (2016).

Weerasinghe, H. & Traven, A. Immunometabolism in fungal infections: the need to eat to compete. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 58, 32–40 (2020).

Traven, A. & Naderer, T. Central metabolic interactions of immune cells and microbes: prospects for defeating infections. EMBO Rep. 20, e47995 (2019).

Adachi, T. et al. A preliminary pilot study: Metabolomic analysis of saliva in oral candidiasis. Metabolites 12, 1294 (2022).

Ghannoum, M. A. et al. Metabolomics reveals differential levels of oral metabolites in HIV-infected patients: toward novel diagnostic targets. OMICS A J. Integ. Biol. 17, 5–15 (2013).

Talapko, J. et al. A putative role of Candida albicans in promoting cancer development: a current state of evidence and proposed mechanisms. Microorganisms 11(6), 1476 (2023).

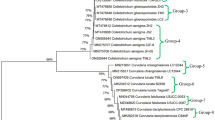

Karajacob, A. S. et al. Candida species and oral mycobiota of patients clinically diagnosed with oral thrush. PLoS ONE 18, e0284043 (2023).

Yang, J., Zhao, X., Lu, X., Lin, X. & Xu, G. A data preprocessing strategy for metabolomics to reduce the mask effect in data analysis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2, 4 (2015).

Bijlsma, S. et al. Large-scale human metabolomics studies: A strategy for data (pre-) processing and validation. Anal. Chem. 78, 567–574 (2006).

Worley, B. & Powers, R. Multivariate analysis in metabolomics. Curr. Metabolomics 1(1), 92–107 (2013).

Brown, A. J., Brown, G. D., Netea, M. G. & Gow, N. A. Metabolism impacts upon Candida immunogenicity and pathogenicity at multiple levels. Trends Microbiol. 22, 614–622 (2014).

Neumann, A. et al. Lipid alterations in human blood-derived neutrophils lead to formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 93, 347–354 (2014).

Assenov, Y., Ramírez, F., Schelhorn, S. E., Lengauer, T. & Albrecht, M. Computing topological parameters of biological networks. Bioinformatics 24, 282–284 (2008).

Duran-Pinedo, A. E. & Frias-Lopez, J. Beyond microbial community composition: functional activities of the oral microbiome in health and disease. Microbes Infect. 17, 505–516 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Functions of sphingolipids in pathogenesis during host–pathogen interactions. Front. Microbiol. 12, 701041 (2021).

Wu, Y., Liu, Y., Gulbins, E. & Grassmé, H. The anti-infectious role of sphingosine inmicrobial diseases. Cells 10, 1105 (2021).

Veerman, E. C. et al. Phytosphingosine kills Candida albicans by disrupting its cell membrane. Biol. Chem. 391, 65–71 (2010).

Lee, M., Lee, S. Y. & Bae, Y. S. Functional roles of sphingolipids in immunity andtheir implication in disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 55, 1110–1130 (2023).

Tafesse, F. G. et al. Disruption of sphingolipid biosynthesis blocks phagocytosis of Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005188 (2015).

Singh, A. & Del Poeta, M. Lipid signalling in pathogenic fungi. Cell. Microbiol. 13, 177–185 (2016).

Liu, X. H. et al. Metabolomics analysis identifies sphingolipids as key signaling moieties in appressorium morphogenesis and function in Magnaporthe oryzae. MBio 10, e01467-e1519 (2019).

Chalfant, C. E. & Spiegel, S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and ceramide 1-phosphate: expanding roles in cell signaling. J. Cell Sci. 118, 4605–4612 (2005).

Urbanek, A. K. et al. The role of ergosterol and sphingolipids in the localization and activity of Candida albicans’ multidrug transporter Cdr1p and plasma membrane ATPase Pma1p. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 9975 (2022).

Wu, G. et al. Proline and hydroxyproline metabolism: implications for animal and human nutrition. Amino Acids 40, 1053–1063 (2011).

Krishnan, N., Dickman, M. B. & Becker, D. F. Proline modulates the intracellular redox environment and protects mammalian cells against oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 44, 671–681 (2008).

Liao, X. H., Majithia, A., Huang, X. & Kimmel, A. R. Growth control via TOR kinase signaling, an intracellular sensor of amino acids and energy availability, with crosstalk potential to proline metabolism. Amino Acids 35, 761–770 (2008).

Grahl, N. et al. Mitochondrial activity and Cyr1 are key regulators of Ras1 activation of C albicans virulence pathways. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005133 (2015).

Devries, M. C. et al. Leucine, not total protein, content of a supplement is the primary determinant of muscle protein anabolic responses in healthy older women. J. Nutr. 148, 1088–1095 (2018).

Holeček, M. Branched-chain amino acids in health and disease: metabolism, alterations in blood plasma, and as supplements. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.) 15, 33 (2018).

Kingsbury, J. M. & McCusker, J. H. Cytocidal amino acid starvation ofSaccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans acetolactate synthase (ilv2{Delta}) mutants is influenced by the carbon source and rapamycin. Microbiology (Reading, England). 156, 929–939 (2010).

Garbe, E. & Vylkova, S. Role of amino acid metabolism in the virulence of human pathogenic fungi. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 6, 108–119 (2019).

Sagar, N. A., Tarafdar, S., Agarwal, S., Tarafdar, A. & Sharma, S. Polyamines: Functions, metabolism, and role in human disease management. Med. Sci. (Basel) 9, 44 (2021).

Zhang, M., Borovikova, L. V., Wang, H., Metz, C. & Tracey, K. J. Spermine inhibition of monocyte activation and inflammation. Mol. Med. 5, 595–605 (1999).

Hesterberg, R. S., Cleveland, J. L. & Epling-Burnette, P. K. Role of polyamines in immune cell functions. Med. Sci. 6, 22 (2018).

Tang, G., Xia, H., Liang, J., Ma, Z. & Liu, W. Spermidine is critical for growth, development, environmental adaptation, and virulence in Fusarium graminearum. Front. Microbiol. 12, 765398 (2021).

Dorighetto Cogo, A. J. et al. Spermine modulates fungal morphogenesis and activates plasmamembrane H+-ATPase during yeast to hyphae transition. Biol. Open 27, bio029660 (2018).

Papackova, Z. & Cahova, M. Fatty acid signaling: the new function of intracellular lipases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 3831–3855 (2015).

Pan, J., Hu, C. & Yu, J. H. Lipid biosynthesis as an antifungal target. J. Fungi (Basel) 4, 50 (2018).

Sandager, L. et al. Storage lipid synthesis is non-essential in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6478–6482 (2002).

Small, D. M. The effects of glyceride structure on absorption and metabolism. Ann. Rev. Nutr. 11, 413–434 (1991).

Gácser, A. et al. Lipase 8 affects thepathogenesis of Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 75, 4710–4718 (2007).

Bagnat, M., Keränen, S., Shevchenko, A., Shevchenko, A. & Simons, K. Lipid rafts function in biosynthetic delivery of proteins to the cell surface in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97, 3254–3259 (2000).

Martin, S. W. & Konopka, J. B. Lipid raft polarization contributes to hyphal growth in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cel. 3, 675–684 (2004).

Vance, J. E. Phospholipid synthesis and transport in mammalian cells. Traffic 16, 1–18 (2015).

O’Donnell, V. B., Rossjohn, J. & Wakelam, M. J. Phospholipid signaling in innate immune cells. J. Clin. Invest. 128(7), 2670–2679 (2018).

Hasim, S. et al. Influence of phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine on farnesol tolerance in Candida albicans. Yeast 35, 343–351 (2018).

Rella, A., Farnoud, A. M. & Del Poeta, M. Plasma membrane lipids and their role in fungal virulence. Prog. Lipid Res. 61, 63–72 (2016).

Dugail, I., Kayser, B. D. & Lhomme, M. Specific roles of phosphatidylglycerols in hosts and microbes. Biochimie 141, 47–53 (2017).

Nie, J. et al. A novel function of the human CLS1 in phosphatidylglycerol synthesis and remodeling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1801, 438–445 (2010).

Su, X. & Dowhan, W. Regulation of cardiolipin synthase levels in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 23, 279–291 (2006).

Han, T. L., Cannon, R. D. & Villas-Boas, S. G. Metabolome analysis during the morphological transition of Candida albicans. Metabolomics 8, 1204–1217 (2012).

De Craene, J. O., Bertazzi, D. L., Bär, S. & Friant, S. Phosphoinositides, major actors in membrane trafficking and lipid signaling pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 634 (2017).

Balla, T. Phosphoinositides: Tiny lipids with giant impact on cell regulation. Physiol. Rev. 93, 1019–1137 (2013).

Konopka, J. B. Plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate is necessary for virulence of Candida albicans. MBio 13, e0036622 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. The role of phosphatidylserine on the membrane in immunity and blood coagulation. Biomark. Res. 10, 4 (2022).

Hasegawa, J. et al. A role of phosphatidylserine in the function of recycling endosomes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 24, 783857 (2021).

Chen, Y. L. et al. Phosphatidylserine synthase and phosphatidylserine decarboxylase are essential for cell wall integrity and virulence in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 1112–1113 (2010).

Matos, G. S., Fernandes, C. M. & Del Poeta, M. Role of sphingolipids in the host-pathogen interaction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1868, 159384 (2023).

Singh, A. & Del Poeta, M. Sphingolipidomics: An important mechanistic tool for studying fungal pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 7, 501 (2016).

Bryan, A. M., Del Poeta, M. & Luberto, C. Sphingolipids as regulators of the phagocytic response to fungal infections. Mediators Inflamm. 2015, 640540 (2015).

Hartel, J. C., Merz, N. & Grösch, S. How sphingolipids affect T cells in the resolution of inflammation. Front Pharmacol. 13, 1002915 (2022).

Ren, W. et al. mTORC1 signaling and IL-17 expression: defining pathways and possible therapeutic targets. Eur. J. Immunol. 46, 291–299 (2016).

Handa, A. K., Fatima, T. & Mattoo, A. K. Polyamines: bio-molecules with diverse functions in plant and human health and disease. Front. Chem. 6, 10 (2018).

Pegg, A. E. Functions of polyamines in mammals. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 14904–14912 (2016).

Ilmarinen, P., Moilanen, E., Erjefält, J. S. & Kankaanranta, H. The polyamine spermine promotes survival and activation of human eosinophils. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 136, 482–4.e11 (2015).

Levy, M. et al. Microbiota-modulated metabolites shape the intestinal microenvironment by regulating NLRP6 inflammasome signaling. Cell 163, 1428–1443 (2015).

Haskó, G. et al. Spermine differentially regulates the production of interleukin-12 p40 and interleukin-10 and suppresses the release of the T helper 1 cytokine interferon-gamma. Shock 14, 144–149 (2000).

Vance, J. E. & Steenbergen, R. Metabolism and functions of phosphatidylserine. Prog. Lipid Res. 44, 207–234 (2005).

Maratou, E. et al. Glucose transporter expression on the plasma membrane of resting and activated white blood cells. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 37, 282–290 (2007).

Hresko, R. C., Kraft, T. E., Quigley, A., Carpenter, E. P. & Hruz, P. W. Mammalian glucose transporter activity is dependent upon anionic and conical phospholipids. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 17271–17282 (2016).

Bergsson, G., Arnfinnsson, J., Steingrímsson, O. & Thormar, H. In vitro killing of Candida albicans by fatty acids and monoglycerides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 3209–3212 (2001).

Shareck, J., Nantel, A. & Belhumeur, P. Conjugated linoleic acid inhibits hyphal growth in Candida albicans by modulating Ras1p cellular levels and downregulating TEC1 expression. Eukaryot. Cell. 10, 565–577 (2011).

Lee, J. H., Kim, Y. G., Khadke, S. K. & Lee, J. Antibiofilm and antifungal activities of medium-chain fatty acids against Candida albicans via mimicking of the quorum-sensing molecule farnesol. Microb. Biotechnol. 14, 1353–1366 (2021).

Altieri, C., Cardillo, D., Bevilacqua, A. & Sinigaglia, M. Inhibition of Aspergillus spp. and Penicillium spp by fatty acids and their monoglycerides. J. Food Prot. 70, 1206–1212 (2007).

Odds, F. C., Brown, A. J. & Gow, N. A. Antifungal agents: Mechanism of action. Trends Microbiol. 11, 272–279 (2003).

Chapela, S., Congost, C., Alonso, M., Burgos, H. & Stella, C. Synergistic effect of dichloroacetate and fluconazole on the growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Pharmacol. Clin. Toxicol. 10, 1162 (2022).

Pfaller, M. A., Riley, J. & Gerarden, T. Polyamine depletion and growth inhibition in Candida albicans and Candida tropicalis by alpha-difluoromethylornithine andcyclohexylamine. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 26, 119–126 (1988).

Rossi, A. et al. Reassessing the use of undecanoic acid as a therapeutic strategy for treating fungal infections. Mycopathologia 186, 327–340 (2021).

Prasad, R., Shah, A. H. & Rawal, M. K. Antifungals: Mechanism of action and drug resistance. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 892, 327–349 (2016).

Seleem, D., Chen, E., Benso, B., Pardi, V. & Murata, R. M. In vitro evaluation of antifungal activity of monolaurin against Candida albicans biofilms. PeerJ 4, 1–17 (2016).

Jumina Nurmala, A. et al. Monomyristin and monopalmitin derivatives: Synthesis and evaluation as potential antibacterial and antifungal agents. Molecules 23, 3141 (2018).

Vandeputte, P., Ferrari, S. & Coste, A. T. Antifungal resistance and new strategies to control fungal infections. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 1–26 (2012).

James, M. O. et al. Therapeutic applications of dichloroacetate and the role of glutathione transferase zeta-1. Pharmacol. Ther. 170, 166–180 (2017).

Netea, M. G., Joosten, L. A., van der Meer, J. W., Kullberg, B. J. & van de Veerdonk, F. L. Immune defence against Candida fungal infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 630–642 (2015).

Domínguez-Andrés, J. et al. Rewiring monocyte glucose metabolism via C-type lectin signaling protects against disseminated candidiasis. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006632 (2017).

Vikram, A., Jesudhasan, P. R., Pillai, S. D. & Patil, B. S. Isolimonic acid interferes with Escherichia coli O157:H7 biofilm and TTSS in QseBC and QseA dependent fashion. BMC Microbiol. 12, 261 (2012).

Guimarães, A. & Venâncio, A. The potential of fatty acids and their derivatives as antifungal agents: a review. Toxins (Basel) 14(3), 188 (2022).