Abstract

To evaluate structural and microvascular changes in the macular retina and choroid of patients with chronic primary angle-closure glaucoma (CPACG) following trabeculectomy, using ultra-widefield swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography (UWF SS-OCTA). This prospective observational study included 40 eyes from CPACG patients undergoing trabeculectomy and 42 eyes from age- and sex-matched healthy controls. UWF SS-OCTA was used to quantify macular parameters including superficial vascular density (SVD) values, ganglion cell complex (GCC) thickness values, choroidal thickness (CT) values, choriocapillaris flow density (CCD) values, and choroidal vascularity index (CVI) values at baseline, 1 week, and 1 month postoperatively. At baseline, the CPACG group showed significantly reduced SVD, GCC thickness, and CVI values, along with diffusely increased CT values compared to healthy controls. After trabeculectomy, IOP was significantly reduced at both 1 week and 1 month. SVD and CVI values significantly improved by 1 month postoperatively, suggesting early microvascular recovery. CT values peaked at 1 week and declined by 1 month, while CCD values showed no significant changes. GCC thickness values remained stable postoperatively, indicating irreversible neuroaxonal damage. CPACG patients exhibit concurrent retinal–choroidal structural impairment and microcirculatory dysfunction. Trabeculectomy leads to partial reversal of microvascular deficits, particularly in SVD and CVI values. However, the irreversibility of neural damage highlights the necessity for early detection and timely intervention in CPACG management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glaucoma is an irreversible neurodegenerative disease of the retina and optic nerve, primarily characterized by retinal ganglion cell (RGC) apoptosis, thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL), and visual field loss. It is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide1,2. Chronic primary angle-closure glaucoma (CPACG) is one of the main causes of irreversible visual impairment in China. The core pathophysiological mechanism involves progressive synechial closure of the anterior chamber angle, leading to impaired aqueous humor outflow, pathologically elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), and subsequent optic nerve damage and visual field defects3, posing a serious threat to visual health in the Chinese population.

Trabeculectomy, a classic and commonly performed IOP-lowering procedure for primary angle-closure glaucoma, involves the partial excision of the trabecular meshwork and the inner wall of Schlemm’s canal to create a new outflow pathway beneath a scleral flap. This reduces aqueous outflow resistance, stabilizes the intraocular environment, and lowers IOP, thereby relieving optic nerve damage4. However, some studies have reported that despite effective postoperative IOP control, a subset of patients continues to experience progressive visual field loss5,6,7. Therefore, identifying additional factors beyond IOP that contribute to visual field deterioration after trabeculectomy is of great clinical importance. Previous studies have revealed structural and vascular differences in the retina and choroid between CPACG patients and healthy controls5,8. Moreover, several investigations have demonstrated that various ocular structures exhibit reversible changes after IOP reduction in glaucoma, such as reversal of lamina cribrosa deformation and optic disc cupping9,10,11. This raises an important question: in CPACG patients with well-controlled IOP following trabeculectomy, do the retinal and choroidal structures and microcirculation of the posterior pole undergo similar dynamic or reversible changes?

In recent years, optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) has been increasingly used to evaluate posterior segment changes in glaucoma following trabeculectomy. However, few studies have focused specifically on the macular region, and data on macular microstructural and microvascular changes after surgery in CPACG patients remain scarce. The latest ultra-widefield swept-source OCTA (UWF SS-OCTA) technology offers high-speed, wide-range scanning with automated segmentation and measurement, minimizing operator-dependent variability. Moreover, its use of long-wavelength light improves signal penetration through the retinal pigment epithelium, enabling clearer visualization of choroidal blood flow and more accurate quantification of choroidal structural and vascular parameters, thus enhancing the assessment of posterior segment microcirculation12.

Therefore, this prospective observational study, conducted in Northeast China, aimed to dynamically monitor changes in macular retinal and choroidal parameters in CPACG patients using UWF SS-OCTA at three time points: preoperatively, and at 1 week and 1 month postoperatively. The objective was to investigate postoperative microcirculatory alterations, identify potential patterns of microvascular remodeling, and provide objective evidence to enhance the evaluation system for surgical outcomes in glaucoma.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This was a prospective observational study. Between March 2023 and December 2024, patients diagnosed with CPACG who were scheduled to undergo trabeculectomy at the Department of Ophthalmology, the Second Hospital of Jilin University, were consecutively enrolled. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Jilin University (Approval No. 2024 − 133) and conducted in strict accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians prior to any treatment.

In this prospective observational study, we enrolled 40 patients (40 eyes) with CPACG who were receiving more than one antiglaucoma medications but had not achieved the target IOP. The inclusion criteria were as follows1: gonioscopically confirmed closure of the anterior chamber angle2; presence of glaucoma-related optic neuropathy and corresponding visual field defects3; sustained elevation of intraocular pressure (IOP > 21 mmHg for ≥ 6 months); and4absence of symptoms or signs of acute attacks. The exclusion criteria were as follows1: presence of acute angle-closure glaucoma, primary open-angle glaucoma, or secondary glaucoma2; eye trauma, or surgeries excluding uncomplicated cataract surgery3; non-glaucomatous optic neuropathy, such as ischemic optic neuropathy or optic neuritis4; high refractive error (spherical equivalent ≤ − 6.00 D or ≥ + 3.00 D)5; unreliable visual field tests (false-positive rate > 15% or fixation loss rate > 20%)6; coexisting ocular conditions potentially affecting OCTA imaging, such as severe cataract, diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, uveitis, or central retinal vein occlusion7; serious systemic diseases including malignancies, hematologic disorders, hepatic or renal dysfunction, or autoimmune diseases.

For the control group, 42 healthy volunteers (42 eyes) with similar age and sex distribution were recruited from the physical examination center of the Second Hospital of Jilin University during the same period. Healthy subjects were required to have an IOP ≤ 21 mmHg and normal visual field test results, with no evidence of any ocular disease or serious systemic disorder.

At baseline, all participants underwent comprehensive ophthalmic examinations, including best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) assessed with a Snellen chart, IOP measured using a non-contact tonometer, gonioscopy, axial length (AL) measurement, visual field measurement, and fundus examination. Subsequently, UWF SS-OCTA imaging was performed using the YG-100 K PRO device (TowardPi Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China).

Postoperative follow-up was conducted at 1 week and 1 month after surgery. At each follow-up visit, patients with CPACG underwent comprehensive ophthalmic examinations and UWF SS-OCTA imaging.

Surgical procedure

All trabeculectomies were performed by two experienced ophthalmic surgeons (J.Z. and Y.G.). To prevent postoperative infection, patients were instructed to instill 0.5% levofloxacin eye drops four times daily starting 3 days before surgery. The surgical procedure included the creation of a fornix-based conjunctival flap and a 4 × 3 mm rectangular scleral flap in the superior quadrant, with a thickness of one-third to one-half of the full scleral thickness. A sponge soaked in mitomycin C at a concentration of 0.3–0.4 mg/mL was placed beneath the scleral flap and on the scleral bed for 3 min, depending on patient age and conjunctival condition. Subsequently, a 1.5 × 0.5 mm block of limbal tissue beneath the scleral flap was excised, followed by a peripheral iridectomy. The scleral flap was closed with 2 to 4 interrupted 10 − 0 nylon sutures to control aqueous humor outflow and maintain anterior chamber depth. The conjunctival flap was then sutured in a watertight fashion. Postoperatively, a combination of 0.5% levofloxacin and 0.1% dexamethasone eye drops was administered to enhance anti-inflammatory management.

Ultra-Widefield Swept-Source optical coherence tomography angiography

UWF SS-OCTA imaging was performed using a 400 kHz swept-source system (TowardPi Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The device was equipped with a 1060 nm vertical-cavity surface-emitting laser and offered an axial resolution of 3.8 μm, a transverse resolution of 10 μm, and a scan depth of 6 mm. Full-thickness vascular visualization was achieved through a high-order moment amplitude decorrelation algorithm combined with a three-dimensional reflectance-space threshold segmentation method13,14. AI-assisted segmentation was applied to identify all retinal and choroidal boundaries, including Bruch’s membrane (BM) and the choroid–sclera interface (CSI). When necessary, manual edits were performed to correct segmentation errors. En face OCT and OCTA images based on the automatically or manually refined retinal and choroidal slabs were generated for visualization15.

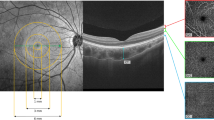

As shown in Fig. 1A, the retinal superficial vascular complex (SVC) was segmented from the internal limiting membrane (ILM) to the junction between the inner plexiform layer (IPL) and inner nuclear layer (INL). Retinal ganglion cell complex (GCC) thickness was defined as the sum of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL), ganglion cell layer (GCL), and IPL, measured from the inner border of the RNFL (immediately beneath the ILM) to the IPL–INL junction. On B-scans, the visually appreciable extent approximately overlapped with the SVC16. The choroid was defined as the region between the BM and the CSI, and choroidal thickness (CT) as the perpendicular distance from the BM to the CSI. Using a built-in algorithm, the choriocapillaris slab was delineated from Bruch’s membrane (BM) to 29 μm below the BM, whereas the large and medium choroidal vessel layer (LMCVL) was defined from 29 μm below the BM to the CSI (Fig. 1B-C)16,17.

Segmentation of macular subregions, structure, and microvasculature. (A) Retinal SVC, defined as the area between the two green segmentation lines. (B) LMCVL, defined as the area between the two green segmentation lines. (C) Choriocapillaris, defined as the area between the two green segmentation lines.

Vascular density (VD) was defined as the percentage of the analysis area occupied by the microvascular network, including retinal superficial vascular density (SVD) and choriocapillaris density (CCD). The choroidal vascularity index (CVI) was defined as the ratio of luminal (vascular) volume to total choroidal volume, providing a more objective, flow-independent descriptor of choroidal vascularity than CCD18.

Macular topography followed the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) grid centered on the fovea, comprising three concentric areas: the central 1-mm circle (foveal region), an annulus from 1 to 3 mm (parafoveal region), and an annulus from 3 to 6 mm (perifoveal region). The parafoveal and perifoveal rings were further subdivided into four quadrants—superior (S), inferior (I), nasal (N), and temporal (T) (Fig. 2)19. Based on this grid, both structural and vascular images were partitioned into nine subfields (Figs. 2 and 3). The final analysis included the following parameters: SVD, GCC thickness, CT, CVI, and CCD.

Illustration of the macular ETDRS grid for retinal and choroidal analysis. The macular region was divided into three concentric rings with diameters of 1 mm, 3 mm, and 6 mm centered on the fovea. Sectors are defined as follows: C1, central fovea (0–1 mm); S3, superior sector within 1–3 mm; S6, superior sector within 3–6 mm; I3, inferior sector within 1–3 mm; I6, inferior sector within 3–6 mm; N3, nasal sector within 1–3 mm; N6, nasal sector within 3–6 mm; T3, temporal sector within 1–3 mm; and T6, temporal sector within 3–6 mm.

ETDRS-based grid segmentation of macular structure and perfusion. The upper panels show parameter maps without the ETDRS grid; the lower panels show the same maps with the ETDRS grid applied. (A) En face OCTA of the retinal SVC. (B) Quantitative SVC perfusion map (red = higher flow/perfusion; blue = lower). (C) Quantitative retinal GCC thickness map (red = thicker; blue = thinner).

All OCTA images were independently reviewed by two senior ophthalmologists (J.Z. and Y.G.). Images with poor overall quality and a quality score ≤ 8 were excluded prior to analysis. To minimize segmentation-related bias, particularly in eyes with markedly thin retinas, OCTA metrics were cross-checked against the corresponding B-scan images after automated slab generation, with manual correction when necessary.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages [n (%)], and comparisons between groups were conducted using the chi-square (χ²) test. Continuous variables were first tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Variables with a normal distribution were analyzed using independent-samples t-tests and presented as mean ± standard deviation (\(\:\stackrel{\text{-}}{\text{x}}\)±s). Non-normally distributed variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test and expressed as median and interquartile ranges [M (P25, P75)].

For repeated measurements, generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to model the data. Multiple comparisons were corrected using the Bonferroni method. A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

Demographic and ocular characteristics

After strict screening procedures, a total of 40 eyes from patients with CPACG and 42 eyes from healthy controls were included in the final analysis. Table 1 summarizes the baseline demographic and ocular characteristics of all participants, including age, sex, laterality, IOP, AL, and mean deviation (MD) of the visual field. Comparative analysis showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, sex, or eye laterality (P > 0.05), indicating good comparability of baseline characteristics. However, the CPACG group exhibited significantly higher IOP, shorter AL, and more severe visual field defects compared to the control group (P < 0.05).

Retinal and choroidal parameter analysis at baseline

Comparisons of retinal parameters between the two groups are presented in Table 2. In the CPACG group, the SVD values were significantly reduced across all macular regions compared to the healthy controls (P < 0.05). Additionally, the CPACG group showed a significant reduction in average macular GCC thickness, as well as in GCC thickness values at the C1, T3, S3, I3, T6, S6, and I6 subregions (P < 0.05). Choroidal parameter comparisons are shown in Table 3. CT values were significantly increased in all macular regions in the CPACG group compared to the healthy controls (P < 0.05). However, no statistically significant differences were observed in CCD between the two groups (P > 0.05). In contrast, CVI values were significantly reduced in all macular regions in the CPACG group (P < 0.05).

To minimize segmentation-related bias, particularly in eyes with markedly thin retinas, OCTA metrics were cross-checked against the corresponding B-scan images after automated slab generation. Using the retinal SVC as an example, we illustrate macular microcirculation. Figure 4 presents SVD images from three subjects: Fig. 4A, a 63-year-old healthy female with no visual-field defect; Fig. 4B, a 59-year-old female with CPACG and a visual-field MD of −10.45 dB; and Fig. 4C, a 64-year-old female with CPACG and an MD of −17.62 dB. The upper row shows automatically segmented OCTA en face images, where macular microcirculation appears best in Fig. 4A, intermediate in Fig. 4B, and poorest in Fig. 4C. For comparison, the lower row shows images based on manual slab delineation guided by structural OCT B-scans, confirming the same pattern: vessel density is highest in Fig. 4A and lowest in Fig. 4C.

Representative images illustrating macular retinal SVD in three subjects: one healthy control and two CPACG patients with different disease severities. The upper panels show OCTA images, where yellow areas indicate non-perfusion regions. The lower panels show the corresponding OCT B-scans, with the retinal SVC defined as the area between the two green segmentation lines. (A) A 63-year-old healthy female without visual field defects, showing a dense capillary network with minimal non-perfusion areas and high vascular density. (B) A 59-year-old female with CPACG (mean deviation = − 10.45 dB), showing a moderately dense capillary network, medium-sized non-perfusion areas, and moderate vascular density. (C) A 64-year-old female with CPACG (mean deviation = − 17.62 dB), showing a sparse capillary network, extensive non-perfusion areas, and reduced vascular density.

Longitudinal changes in retinal and choroidal parameters following trabeculectomy

All 40 CPACG patients successfully underwent trabeculectomy without any notable complications. One patient was excluded due to poor OCTA image quality at 1 week postoperatively, and three patients were lost to follow-up at 1 month due to personal reasons. Ultimately, data from 36 eyes of 36 CPACG patients were included in the final analysis. The mean preoperative IOP was 22.06 ± 3.68 mmHg. After trabeculectomy, IOP significantly decreased to 14.38 ± 3.53 mmHg at 1 week and to 12.68 ± 3.99 mmHg at 1 month postoperatively. Compared with baseline, the reductions in IOP at both postoperative time points were statistically significant (P < 0.05), while the difference between the 1-week and 1-month measurements was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Longitudinal changes in retinal parameters after trabeculectomy are shown in Table 4. The average macular SVD, as well as SVD values in the C1, T3, S3, N3, I3, and N6 regions, showed significant increases over time (P < 0.05). Specifically, compared with baseline, the average SVD and SVD values in the C1, T3, S3, N3, I3, and N6 regions were significantly higher at 1 month postoperatively (P < 0.05). Compared with the 1-week time point, the average SVD and the SVD values in the C1, T3, S3, N3, and I3 regions were also significantly increased at 1 month (P < 0.05). However, no significant changes in SVD were observed between the preoperative and 1-week postoperative time points (P > 0.05). Additionally, longitudinal changes in macular GCC thickness after surgery were not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Longitudinal changes in choroidal parameters are presented in Table 5. CT showed significant temporal variation across all macular regions (P < 0.001), displaying a trend of initial increase followed by a decrease. Compared with baseline, average CT and CT values in the T3, S3, N3, I3, T6, S6, N6, and I6 regions were significantly increased at 1 week postoperatively (P < 0.05). Compared with 1 week, average CT and CT values in the T3, S3, I3, T6, S6, and N6 regions were significantly reduced at 1 month (P < 0.05). However, CT values at 1 month did not significantly differ from baseline (P > 0.05). No significant longitudinal changes in CCD were observed after surgery (P > 0.05). CVI values exhibited significant temporal variation across all macular regions (P < 0.001), showing a trend of initial decrease followed by an increase. Although there was a decreasing trend in CVI at 1 week postoperatively compared with baseline, the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). By contrast, at 1 month postoperatively, the average CVI and CVI values in the N3, T6, S6, and N6 regions were significantly higher than those at baseline (P < 0.05). Additionally, all regional CVI values were significantly increased at 1 month compared to 1 week postoperatively (P < 0.05).

Discussion

The traditional postoperative evaluation system for CPACG primarily centers on IOP and visual field assessment. However, both parameters have significant limitations in reflecting microcirculatory status following surgery. By leveraging OCTA technology, we quantitatively analyzed macular parameter values, including SVD values, GCC thickness values, CT values, CCD values, and CVI values. These metrics not only offer potential novel indicators for surgical outcome evaluation but also help reveal microvascular remodeling patterns in CPACG patients, thereby deepening our understanding of glaucoma-related hemodynamics from a microcirculatory perspective.

The macular region, located at the center of the retina, contains more than 50% of RGCs and is responsible for central vision. The GCC, situated in the inner retinal layers, represents an integrated structural and functional unit of RGCs and serves as a surrogate indicator of RGC loss. The macular blood supply mainly originates from the SVC to meet the high metabolic demands of RGCs, and the SVD reflects the perfusion status of the macular microcirculation20,21. Previous studies have demonstrated reduced macular vessel density and GCC thickness in patients with both open-angle glaucoma (POAG) and primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG), findings consistent with our results22,23,24,25. This can be attributed to the persistent elevation of IOP in CPACG, which exerts direct mechanical compression on the superficial retinal layers, leading to structural damage. From a hemodynamic perspective, sustained high IOP induces oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, resulting in capillary constriction and reduced blood flow. Additionally, fluctuations in IOP can mechanically compress retinal vessels, further diminishing SVD26. In our study, the most pronounced GCC thinning was observed in the inferior macular sector of CPACG patients. This may be explained by the fact that the inferior macular region contains dense bundles of nerve fibers projecting to the inferior optic disc, characterized by long axonal paths and high energy requirements. A large amount of ATP is needed to maintain axonal transport, rendering this region particularly vulnerable to vascular dysregulation and ischemia. When IOP increases or perfusion decreases, RGCs in this area are prone to axonal transport failure and apoptosis due to insufficient energy supply, resulting in marked GCC thinning. This pathological pattern aligns with the “crowding hypothesis,” which posits that regions with densely packed nerve fibers and higher metabolic demands are more susceptible to glaucomatous damage23,27.

Numerous studies have confirmed that ocular perfusion can improve following glaucoma surgery once IOP is well controlled5,8,28. Consistent with this, our findings demonstrated a postoperative upward trend in macular SVD values at both 1 week and 1 month after trabeculectomy, with a statistically significant improvement at 1 month compared to baseline. Gillmann et al. reported a significant increase in parafoveal vessel density at 2 months after selective laser trabeculoplasty in POAG patients29. Similarly, Ch’ng et al. found a significant increase in parafoveal vessel density at 3 months following different glaucoma surgeries in POAG30. The variation in the timing of blood flow improvements may be attributed to differences in pathophysiological mechanisms between PACG and POAG. Another possibility is that the CPACG patients in our study had higher preoperative IOP, and previous research has shown that greater preoperative IOP and larger postoperative reductions are associated with more pronounced improvements in ocular perfusion31. The increase in SVD values observed after trabeculectomy in CPACG patients may result from two main mechanisms. First, a reduction in IOP can relieve mechanical compression28, reduce vascular collapse and hypoperfusion, and facilitate the reopening of retinal capillaries—a key contributor to the observed increase in SVD values. Second, endothelial function recovery may promote sustained capillary perfusion, further enhancing SVD values32. Thus, we hypothesize that trabeculectomy may partially reverse the retinal microvascular impairment caused by CPACG. However, although SVD values showed an upward trend at 1 week postoperatively, the difference was not statistically significant. This may be due to persistent inflammation triggered by chronic high IOP and surgical trauma, resulting in the release of inflammatory mediators, increased vascular permeability, tissue edema, and OCTA signal attenuation—factors that could obscure true perfusion recovery33. Additionally, vascular endothelial recovery and remodeling may not have been completed by 1 week postoperatively. As inflammation resolves over time, SVD values increase significantly. Long-term follow-up and mechanistic studies are warranted to clarify the trajectory of SVD value changes and evaluate their clinical value as a postoperative biomarker.

GCC thickness values, a quantitative indicator of RGCs and their axons, reflect structural integrity of the optic nerve, which is known to be irreversible once damaged. In this study, GCC thickness values showed no significant changes before and after surgery. Although a slight postoperative increase was observed, it is unlikely to be clinically meaningful. The increase may result from transient local inflammation and edema caused by surgical trauma, leading to pseudo-thickening on OCTA images, particularly at 1 week postoperatively, with gradual resolution by 1 month. Another possible explanation is that corneal edema in the early postoperative period may reduce signal clarity and cause boundary segmentation errors, rather than indicating true structural restoration33. Supporting this, Raghu et al. reported a temporary increase in RNFL thickness 1 week after trabeculectomy, which returned to baseline by 3 months, further affirming the irreversibility of glaucomatous neurodegeneration34. Whether this transient change has any clinical significance remains debatable and warrants longer-term investigation to clarify the long-term behavior of GCC thickness values.

The choroid is a highly vascularized tissue composed of a dense vascular network and interstitial stroma. Our study revealed that the macular CT was significantly increased in patients with CPACG, which is consistent with the characteristic pathophysiological features of this disease. Current evidence generally supports the notion that choroidal thickening serves as an initiating factor in the mechanism of angle closure. Expansion of the choroid increases posterior chamber pressure, pushing the lens–iris diaphragm forward and resulting in anterior chamber angle closure35. Subsequently, the elevated IOP may further lead to choroidal venous congestion and edema, forming a positive feedback loop that exacerbates the pathological process36. This mechanism differs from that of POAG, in which the anterior chamber angle remains open and the major pathology lies in increased resistance within the trabecular meshwork outflow pathway. Some studies have reported decreased choroidal thickness in patients with POAG37,38,39. In contrast, Li et al. and Mwanza et al. found no significant difference in macular choroidal thickness between POAG and normal eyes40,41. Our study revealed a significant increase in CT values during the early postoperative period, peaking at 1 week, in line with findings from Silva et al. and Bouillot et al.42,43. Several mechanisms may underlie this response: surgical trauma and inflammatory cytokine release may disrupt tight junctions in the blood–choroid barrier, allowing protein leakage into the stroma, reducing osmotic pressure gradients, and causing fluid retention and choroidal swelling. In addition, postoperative filtration bleb formation and enhanced uveoscleral outflow may increase perivascular interstitial fluid flow, further contributing to extravascular fluid accumulation44. Moreover, the sudden drop in IOP may relieve venous compression, leading to reperfusion and vascular dilation, accelerating thickening of CT values45,46. Therefore, both luminal and stromal expansion may account for the prominent increase in CT values at 1 week. As postoperative inflammation subsides and barrier integrity is restored, osmotic gradients normalize and fluid is reabsorbed via the lymphatic system, resulting in a subsequent decrease in CT values. This dynamic remodeling process has been validated by multiple studies42,43,47.

As the ratio of luminal area to total choroidal area, CVI values are more sensitive than CT values in detecting changes in the vascular-to-stromal proportion48. Our results showed that the CVI was significantly lower in patients with CPACG compared with healthy controls. A reduction in CVI generally results from a decrease in the luminal area and an increase in the stromal area. Wang et al. reported that the CVI was significantly reduced in both POAG and PACG eyes. Specifically, the luminal area was markedly decreased in POAG, whereas the stromal area was significantly increased in PACG49. In addition, choroidal hypoperfusion secondary to intraocular hemodynamic disturbances may also contribute to the reduction in CVI. Loss of choroidal microvasculature has been observed in both POAG and PACG eyes, further exacerbating the decline in CVI49,50. Our findings showed a slight decrease in CVI values during the early postoperative period, possibly due to dominant stromal swelling. With inflammation resolution and accelerated fluid clearance, CVI values gradually increased. Although direct evidence of CVI value changes after glaucoma surgery is limited, Takamatsu et al. reported relatively greater increases in choroidal vascular thickness than stromal thickness at 1 month postoperatively51. Similarly, Kojima et al. attributed early postoperative choroidal thickening primarily to an increase in vascular luminal area52. These studies support our observations.

The CCD reflects the vascular perfusion status of the choriocapillaris layer. Our results showed a downward trend in CCD among patients with CPACG; however, the difference compared with healthy controls was not statistically significant. Similarly, Lun et al. evaluated macular choriocapillaris parameters in healthy subjects and patients with POAG and found no significant differences between the two groups53. This may be explained by the fact that the macular region receives the majority of RGC blood supply from the SVC54. In addition, the CCD value did not show a significant change after trabeculectomy, suggesting that the choriocapillaris may maintain stable blood flow through local autoregulatory mechanisms, making it less susceptible to fluctuations in IOP and alterations in ocular microcirculation55.

In our cohort, although most patients exhibited a marked postoperative reduction in IOP with concurrent recovery of SVD and CVI values, a small subset (five cases) showed persistently elevated IOP and no improvement in macular microcirculation at the 1-month follow-up. None of these patients demonstrated visual field progression during this short observation period; however, they were considered for secondary trabeculectomy. The coexistence of sustained high IOP and stagnant microvascular perfusion strongly suggests that mechanical compression on ocular vessels remained unresolved, thereby impeding circulatory recovery. Given the limited follow-up duration, it remains uncertain whether the absence or even deterioration of postoperative microcirculatory improvement could serve as a predictor of future visual field loss. Longer longitudinal studies are warranted to clarify this potential prognostic association.

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first longitudinal investigation to quantitatively evaluate macular retinal microvascular and choroidal remodeling in patients with CPACG following trabeculectomy, using the advanced imaging modality of UWF SS-OCTA. Our study provides new insights into the distinct pathophysiological features and postoperative recovery patterns of this glaucoma subtype. Specifically, we demonstrate a clear dichotomy between the reversible nature of microcirculatory dysfunction (SVD and CVI) and the irreversible neuroaxonal damage reflected by GCC thickness. This study confirmed the beneficial effect of trabeculectomy on macular microcirculation and provides theoretical support for early surgical intervention in patients with CPACG.

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, and all participants were recruited from a single tertiary center, which may introduce selection bias and limit generalizability due to differences in surgical standardization. Future multicenter studies with larger cohorts are needed to validate these findings. Second, the follow-up period was relatively short, restricting our ability to assess the long-term evolution and stabilization of retinal and choroidal structures and microcirculation in CPACG. Extended follow-up will be necessary to fully characterize dynamic vascular remodeling and late-onset changes. Lastly, for ethical and clinical reasons, patients continued their topical antiglaucoma medications preoperatively. Although no such medications were used postoperatively, we cannot completely rule out potential bias introduced by prior medication use.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that patients with CPACG exhibit coexisting structural damage and circulatory impairment in the macular retina–choroid region, as evidenced by significantly reduced macular GCC thickness values, SVD values, and CVI values. In contrast, CT values were diffusely increased, which may reflect an inherent anatomical characteristic of chronic angle-closure glaucoma.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in this study are all available in the article. Contact the corresponding author for additional information.

References

Lee, S. S. & Mackey, D. A. Glaucoma - risk factors and current challenges in the diagnosis of a leading cause of visual impairment. Maturitas 163, 15–22 (2022).

Guo, Y., Zhao, J., Hou, S. & Chen, Z. Exploring the effect of SGLT2 inhibitors on the risk of primary open-angle glaucoma using Mendelian randomization analysis. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 13946 (2025).

Nongpiur, M. E., Ku, J. Y. & Aung, T. Angle closure glaucoma: a mechanistic review. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 22 (2), 96–101 (2011).

Lim, R. The surgical management of glaucoma: A review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 50 (2), 213–231 (2022).

James, C. B. Effect of trabeculectomy on pulsatile ocular blood flow. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 78 (11), 818–822 (1994).

Ehrnrooth, P., Puska, P., Lehto, I. & Laatikainen, L. Progression of visual field defects and visual loss in trabeculectomized eyes. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 243 (8), 741–747 (2005).

Kotecha, A. et al. Optic disc and visual field changes after trabeculectomy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50 (10), 4693–4699 (2009).

Berisha, F. et al. Effect of trabeculectomy on ocular blood flow. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 89 (2), 185–188 (2005).

Pederson, J. E. & Herschler, J. Reversal of glaucomatous cupping in adults. Arch. Ophthalmol. 100 (3), 426–431 (1982).

Lee, E. J., Kim, T. W. & Weinreb, R. N. Reversal of lamina cribrosa displacement and thickness after trabeculectomy in glaucoma. Ophthalmology 119 (7), 1359–1366 (2012).

Gietzelt, C. et al. Structural reversal of disc cupping after trabeculectomy alters Bruch membrane Opening-Based parameters to assess neuroretinal rim. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 194, 143–152 (2018).

Xiao, B., Song, Y., Yan, M., Ye, Y. & Huang, Z. Quantitative analysis of choroidal vascular structures and anatomical changes in pachychoroid spectrum diseases using ultra-widefield SS-OCTA. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 344 (2025).

Zhang, W. et al. Advanced ultrawide-field optical coherence tomography angiography identifies previously undetectable changes in biomechanics-related parameters in nonpathological myopic fundus. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 920197 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Choroidal vessel density in major depressive disorder using swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography. J. Affect. Disord. 344, 79–85 (2024).

Wu, Y. et al. Early detection of retinal and choroidal microvascular impairments in diabetic patients with myopia. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 13, 1609928 (2025).

Wang, J. et al. Assessment of retinal and choroidal microcirculatory alterations following radiofrequency catheter ablation in atrial fibrillation patients using swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 13, 1612303 (2025).

Tang, C. et al. Interocular differences in choroidal thickness and circulation in anisomyopic adults and their association with myopia severity. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 12, 1641704 (2025).

Agrawal, R. et al. Exploring choroidal angioarchitecture in health and disease using choroidal vascularity index. Prog Retin Eye Res. 77, 100829 (2020).

Wu, H. et al. Assessment of choroidal vascularity and choriocapillaris blood perfusion in anisomyopic adults by SS-OCT/OCTA. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 62 (1), 8 (2021).

Kur, J., Newman, E. A. & Chan-Ling, T. Cellular and physiological mechanisms underlying blood flow regulation in the retina and choroid in health and disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 31 (5), 377–406 (2012).

Scuderi, G., Fragiotta, S., Scuderi, L., Iodice, C. M. & Perdicchi, A. Ganglion cell complex analysis in glaucoma patients: what can it tell us? Eye Brain. 12, 33–44 (2020).

Köse, H. C. & Tekeli, O. Comparison of microvascular parameters and diagnostic ability of optical coherence tomography angiography between eyes with primary angle closure glaucoma and primary open angle glaucoma. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 40, 103114 (2022).

Lommatzsch, C., Rothaus, K., Koch, J. M., Heinz, C. & Grisanti, S. OCTA vessel density changes in the macular zone in glaucomatous eyes. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 256 (8), 1499–1508 (2018).

Wu, J. H. et al. Association of macular OCT and OCTA parameters with visual acuity in glaucoma. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 107 (11), 1652–1657 (2023).

Wu, J. H., Moghimi, S., Nishida, T., Mahmoudinezhad, G. & Weinreb, L. M. Z. Association of macular vessel density and ganglion cell complex thickness with central visual field progression in glaucoma. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 107 (12), 1828–1833 (2023).

Coviltir, V., Burcel, M. G., Baltă, G. & Marinescu, M. C. Interplay between ocular ischemia and glaucoma: an update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25(22), 12400 (2024).

Hood, D. C., Raza, A. S., de Moraes, C. G., Liebmann, J. M. & Ritch, R. Glaucomatous damage of the macula. Prog Retin Eye Res. 32, 1–21 (2013).

Park, H. L. et al. Microvasculature recovery detected using optical coherence tomography angiography and the rate of visual field progression after glaucoma surgery. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 62 (15), 17 (2021).

Gillmann, K., Rao, H. L. & Mansouri, K. Changes in peripapillary and macular vascular density after laser selective trabeculoplasty: an optical coherence tomography angiography study. Acta Ophthalmol. 100 (2), 203–211 (2022).

Ch’ng, T. W. et al. Effect of surgical intraocular pressure Lowering on retinal structures - nerve fibre layer, foveal avascular zone, peripapillary and macular vessel density: 1 year results. Eye (Lond). 34 (3), 562–571 (2020).

In, J. H., Lee, S. Y., Cho, S. H. & Hong, Y. J. Peripapillary vessel density reversal after trabeculectomy in glaucoma. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 8909714 (2018).

Alarcon-Martinez, L. et al. Neurovascular dysfunction in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 97, 101217 (2023).

Ahmadzadeh, A., Schmidt, B. S., Bach-Holm, D. & Kessel, L. Early inflammation control after trabeculectomy by steroid and Non-steroidal eye drops: A randomized controlled trial. Ophthalmol. Ther. 12 (2), 969–984 (2023).

Raghu, N., Pandav, S. S., Kaushik, S., Ichhpujani, P. & Gupta, A. Effect of trabeculectomy on RNFL thickness and optic disc parameters using optical coherence tomography. Eye (Lond). 26 (8), 1131–1137 (2012).

Quigley, H. A. What’s the choroid got to do with angle closure? Arch. Ophthalmol. 127 (5), 693–694 (2009).

Zhang, X. et al. The effect of change in intraocular pressure on choroidal structure in glaucomatous eyes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58 (7), 3278–3285 (2017).

Sacconi, R. et al. SD-OCT choroidal thickness in advanced primary Open-Angle glaucoma. J. Glaucoma. 26 (6), 523–527 (2017).

Betzler, B. K., Siat, D. J. Y., Agrawal, R., Dorairaj, S. & Ang, B. C. H. Comparison of peripapillary choroidal thickness between primary Open-angle Glaucoma, normal tension Glaucoma, and normal eyes: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Ophthalmol. Glaucoma. 7 (4), 359–371 (2024).

Kutluksaman, B., Yavas, G. F., Inan, S., Dogan, M. & Inan, U. U. Choroidal thickness and its correlations with ocular parameters in primary Open-angle glaucoma. Beyoglu Eye J. 4 (3), 179–189 (2019).

Li, F., Huo, Y., Ma, L. & Tang, G. Correlation analysis between macular choroidal thickness and visual field mean defect in primary Open-Angle glaucoma. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 5574950 (2021).

Mwanza, J. C., Hochberg, J. T., Banitt, M. R., Feuer, W. J. & Budenz, D. L. Lack of association between glaucoma and macular choroidal thickness measured with enhanced depth-imaging optical coherence tomography. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52 (6), 3430–3435 (2011).

Silva, D. et al. Changes in choroidal thickness following trabeculectomy and its correlation with the decline in intraocular pressure. Int. Ophthalmol. 39 (5), 1097–1104 (2019).

Bouillot, A. et al. Changes in choroidal thickness and optic nerve head morphology after filtering surgery: nonpenetrating deep sclerectomy versus trabeculectomy. BMC Ophthalmol. 19 (1), 24 (2019).

Nickla, D. L. & Wallman, J. The multifunctional choroid. Prog Retin Eye Res. 29 (2), 144–168 (2010).

Kara, N. et al. Changes in choroidal thickness, axial length, and ocular perfusion pressure accompanying successful glaucoma filtration surgery. Eye (Lond). 27 (8), 940–945 (2013).

Januleviciene, I. et al. Effect of trabeculectomy on ocular hemodynamic parameters in pseudoexfoliative and primary Open-angle glaucoma patients. J. Glaucoma. 24 (5), e52–e56 (2015).

Kadziauskiene, A., Kuoliene, K., Asoklis, R., Lesinskas, E. & Schmetterer, L. Changes in choroidal thickness after intraocular pressure reduction following trabeculectomy. Acta Ophthalmol. 94 (6), 586–591 (2016).

Singh, S. R., Vupparaboina, K. K., Goud, A., Dansingani, K. K. & Chhablani, J. Choroidal imaging biomarkers. Surv. Ophthalmol. 64 (3), 312–333 (2019).

Wang, D. et al. Comparison of the choroid in primary open angle and angle closure glaucoma using optical coherence tomography. J. Glaucoma. 32 (11), e137–e44 (2023).

Rechtman, E. & Harris, A. Choroidal blood flow regulation and possible implications to glaucoma. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 36 (2), 111–112 (2008).

Takamatsu, Y. et al. Relationship between changes in the choroidal structure and blood flow of the macula after trabeculectomy. Transl Vis. Sci. Technol. 10 (14), 30 (2021).

Kojima, H. et al. Changes in choroidal area after intraocular pressure reduction following trabeculectomy. PLoS One. 13 (8), e0201973 (2018).

Lun, K. et al. Investigating the macular choriocapillaris in early primary open-angle glaucoma using swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 999167 (2022).

Tan, B. et al. Techniques for imaging the choroid and choroidal blood flow in vivo. Exp. Eye Res. 247, 110045 (2024).

Milani, P. et al. The macular choriocapillaris flow in glaucoma and Within-Day fluctuations: an optical coherence tomography angiography study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 62 (1), 22 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Editage (www.editage.cn) for their assistance with English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YJG and ZQC conceptualized the study. JZ obtained ethical approval and collected the data. YJG performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. ZQC provided critical review and revision of the manuscript. All authors actively participated in the research, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Jilin University (Approval No. 2024 − 133) and conducted in strict accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians prior to any treatment.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, Y., Zhao, J. & Chen, Z. Longitudinal quantitative assessment of macular retinal and choroidal remodeling after trabeculectomy in chronic primary angle-closure glaucoma using ultra-widefield SS-OCTA. Sci Rep 15, 45280 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29643-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29643-6