Abstract

As global conventional natural gas resources are increasingly depleted, shale gas, a key form of unconventional natural gas, has gained significant attention due to advancements in extraction technologies. This study investigated shale samples from the Yanchang Formation of the Ordos Basin. Mechanical tests were conducted on shale specimens with bedding orientations of 0°, 45°, and 90°, including static tests (uniaxial compression, triaxial compression, Brazilian splitting) and dynamic impact tests (SHPB), facilitating a comprehensive analysis of strength, deformation, and failure modes under various loading conditions. The results indicate pronounced anisotropy in shale’s mechanical behavior. Dynamic compressive strength increases with strain rate, exhibiting a distinct U-shaped relationship with bedding angle. Based on experimental data, an enhanced HJC constitutive model is proposed, replacing the conventional strain rate term with a dynamic increase factor (DIF). This modification significantly improves predictions of material behavior under high-strain-rate loading. Moreover, the refined HJC model outperforms both the RHT and HJC models in characterizing shale behavior under high-strain-rate conditions. The findings provide essential mechanical parameters and a robust constitutive framework to support efficient and environmentally sustainable shale gas extraction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The depletion of conventional natural gas resources globally has heightened the significance of unconventional gas reserves1,2. By 2018, China’s shale gas production had surged, positioning it as the second-largest producer worldwide3. Shale reservoirs are primarily composed of clay minerals, with substantial amounts of brittle minerals4. This mineral composition—characterized by brittle constituents and thin laminations—imparts brittle mechanical properties to shale. Additionally, shale exhibits low porosity and permeability. Despite this, it contains significant kerogen capable of storing large quantities of natural gas, with some hydrocarbons existing in adsorbed form due to the very low porosity5. This rock structure, combined with the presence of adsorbed hydrocarbons, poses considerable challenges for efficient shale gas extraction. Jiang et al.6 proposed an innovative approach involving in-situ methane detonation to fracture shale formations. This method generates numerous efficient pathways for gas migration near the wellbore, enhancing shale gas extraction. Consequently, understanding the dynamic mechanical properties and failure mechanisms of shale is crucial.

Hydraulic fracturing is the primary method for shale gas production, employing pressurized fluid to induce artificial fractures in the reservoir, thus improving permeability in low-porosity shale formations7. Wells treated with hydraulic fracturing exhibit significantly higher production rates than non-fractured wells8,9. However, fracturing fluids often contain chemical additives—such as biocides and friction reducers—that pose potential environmental risks10,11. These additives may migrate into aquifers during operations, leading to groundwater contamination.

In contrast, in-situ methane detonation fracturing has gained increasing attention as a viable alternative12. This technique involves injecting a combustion enhancer into the wellbore, where it mixes with desorbed methane to form a combustible gas mixture. Upon ignition, the detonation generates a shockwave that creates multiple macroscopic fractures in the reservoir, further extending these fractures through the expansion of high-pressure explosive gases. Due to its efficiency and reduced environmental impact, this fracturing method holds significant promise as a more sustainable alternative with broad application potential.

In petroleum engineering, considerable research has focused on the mechanical properties of shale, given their critical role in hydrocarbon extraction. Using triaxial compression tests, Qi et al.13 investigated shale samples with varying dip angles and water contents, leading to the development of a damage model based on their experimental findings. Their results indicate that shale brittleness decreases progressively with increasing water content. Higher confining pressure mitigates the anisotropy in damage evolution due to bedding orientation and water saturation. Ma et al.14, combining CT imaging with uniaxial compression data from Wufeng-Longmaxi Formation samples, proposed a damage constitutive model to describe hydrated shale. Their model simulations showed less than a 10% deviation in peak stress compared to experimental stress–strain curves. Song et al.15 introduced an anisotropic constitutive model for shale, requiring only five independent elastic parameters and four strength parameters, thereby simplifying the calibration process. This model demonstrated strong agreement with experimental data from shale samples collected at three different sites.

Ma et al.16 developed a damage constitutive model that incorporates the residual shear strength of shale, enabling accurate representation of the material’s mechanical response before and after peak stress. Guo et al.17 conducted in-situ high-temperature triaxial tests on Sichuan Basin shale, creating a strength degradation model that integrates temperature dependence based on the Geological Strength Index (GSI). This model effectively captures the ascending branch and peak region of the stress–strain curve, though it is less accurate in the post-peak softening phase. It partially reflects the thermo-mechanical behavior of shale under coupled thermal and mechanical conditions.

Gao et al.18 performed SHPB experiments at various temperatures and impact velocities, developing a dynamic strength damage model based on the D-P failure criterion, which simultaneously accounts for temperature and strain rate effects. With appropriate parameter adjustments, the model accurately represents the temperature-insensitive peak stress behavior of shale.

While constitutive models for shale under static and thermodynamic conditions are well-established, they often fall short in capturing mechanical responses under high strain rates. Emerging detonation fracturing technologies, which rely on shock waves to alter reservoir structures, require models that simulate dynamic loading conditions. Due to its distinct lamination structure, shale exhibits significant anisotropy, which differentiates it from conventional rocks. However, the influence of bedding angle on this anisotropic behavior is often inadequately addressed in current constitutive models.

Wan et al.19 explored the dynamic mechanical behavior of naturally jointed schist and developed Holmquist-Johnson–Cook (HJC) constitutive models for different bedding orientations. They determined model parameters for specific angles by fitting experimental data. The Zhou-Wang-Tang (ZWT) model has also been applied to capture the rate-dependent nonlinear viscoelasticity of shale at various bedding angles. Luo et al.20 conducted triaxial SHPB testing on shale specimens with varying orientations and introduced an enhanced ZWT damage model to describe the material’s dynamic response under confining pressure. Notably, the ZWT model, originally developed for soft viscoelastic materials such as polymers and rubbers21, has been adapted to shale.

The HJC model, originally proposed for concrete, includes damage parameters that simulate material degradation and crack propagation, making it particularly relevant to fracture technology. Given shale’s typically brittle failure behavior, the HJC model provides a more suitable framework for capturing its macroscopic failure. Both the HJC and Riedel-Hiermaier-Thoma (RHT) models are widely regarded as effective for simulating high-strain-rate behavior in brittle materials and are commonly used in dynamic mechanical models for rocks22,23,24.

However, Jiang et al.25 noted that the original HJC and RHT models fail to accurately capture rate effects at very high strain rates, with predicted peak stresses often significantly underestimating experimental values. Xie et al.26 suggested that replacing the strain rate term in the HJC model with a dynamic increase factor (DIF) would improve the characterization of strain rate sensitivity. The DIF can be expressed in various forms, including piecewise and exponential functions of the logarithm of strain rate.

The Ordos Basin in China hosts high-quality shale gas resources27. This study focuses on the dynamic mechanical behavior of naturally fractured shale from the Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin, providing practical insights for enhancing the efficiency and environmental sustainability of shale gas development. Through Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar (SHPB) testing, the dynamic mechanical properties of shale with specific bedding orientations were evaluated. Static and dynamic tests on shale from different bedding planes offer valuable references for the completion process of shale gas wells in the Yanchang Formation. The results revealed distinct mechanical properties in Yanchang Formation shale compared to commonly studied Longmaxi Formation shale. Calibration of parameters for various dynamic constitutive models showed that the HJC model with DIF more accurately describes the mechanical behavior of bedded shale. The enhanced HJC model is recommended for numerical simulations throughout various stages of the shale gas well lifecycle.

Experimental methods

Shale sample

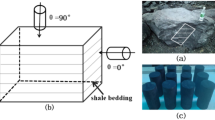

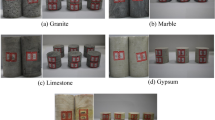

Shale specimens sourced from the Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin were prepared for subsequent analysis. Large, geometrically intact cores with uniform bedding were selected and processed into standard cylindrical specimens28. For uniaxial and triaxial compression tests, cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 100 mm were fabricated. For both SHPB and Brazilian splitting tests, cylindrical specimens measuring 50 mm in diameter and 25 mm in height were prepared (Table 1). To obtain constitutive parameters at various angles, interpolation can be used for angles not directly tested, with calibration of the 45° parameters enhancing the accuracy of interpolation. Shale specimens were prepared with three distinct bedding orientations relative to the machined end face: 0°, 45°, and 90° (Fig. 1). Prior to testing, the shale samples were dried in an oven, and the machined end face served as the load application surface during mechanical testing.

SHPB testing

The SHPB setup consists of an air gun, a projectile, an incident rod, a transmission rod, and an absorption rod. Pneumatic pressure from the air gun is used to launch the projectile, which impacts the incident rod, generating an incident elastic stress wave. A pulse shaper attached to the front end of the incident rod produces a smooth, bell-shaped wave, ensuring stable loading of the specimen. The specimen is positioned between the incident and transmission rods, with petroleum jelly applied to its end faces to reduce frictional effects on the results29. Over a very short time interval, the stress wave is reflected multiple times within the specimen until it reaches stress equilibrium. The absorption rod captures the energy transmitted through the transmission rod, preventing reflected waves from returning to the specimen and transmission rod. Strain signals captured by gauges placed at the midpoints of the incident and transmission bars are transmitted to a dynamic strain amplifier and displayed on an oscilloscope (Fig. 2).

The shale specimens were subjected to stress waves generated by the SHPB system, with graded gas pressures used to impact the system. Pressure levels were determined based on existing research methodologies and preliminary tests, resulting in six pressure gradients: 0.08 MPa, 0.10 MPa, 0.12 MPa, 0.15 MPa, 0.20 MPa, and 0.24 MPa30. The measured strain signals from the incident and transmission bars were processed using the three-wave method31, allowing for the derivation of strain rates and stress–strain responses of the shale specimens Table 2.

Based on one-dimensional elastic stress wave theory, the strain rate, stress, and strain of the specimen can be determined from the measured strain signals in the incident and transmission bars. The mechanical properties of the specimen are calculated as shown in Eq. (1).

In the given equation, \(c_{s}\) represents the elastic wave velocity within the bar under uniaxial stress conditions, while E and A denote the elastic modulus and cross-sectional area of the bar, respectively. The variables \(\varepsilon_{i}\), \(\varepsilon_{r}\), and \(\varepsilon_{t}\) correspond to the incident, reflected, and transmitted strain signals measured by the strain gauges.

Uniaxial compression test

Experiments were performed using the RMT-150C multi-functional mechanical testing system, as shown in Fig. 3. This system offers a maximum axial load capacity of 1000 kN and supports confining pressures up to 50 MPa. It is capable of conducting various mechanical tests, including uniaxial compression, Brazilian splitting (indirect tensile), and triaxial compression tests. All quasi-static mechanical tests in this study were carried out using the RMT-150C system. Each test is conducted with three replicate experiments.

The bedding structure and internal matrix of shale can exhibit varying degrees of development and pre-existing damage. Consequently, a single test is inadequate for characterizing the static mechanical properties of shale at a specific bedding angle. The testing protocol involved conducting multiple experiments on rock samples for each orientation. Outliers with significant deviations were excluded, and the average of the remaining valid results was used as the representative value.

The elastic modulus (E) and Poisson’s ratio (ν) for the shale specimens were determined using Eqs. (2) and (3), respectively.

In the constitutive model, the parameters \({\upsigma }_{{\text{a}}}\) and \(\sigma_{b}\) represent the stress values at the initial and final points of the linear elastic stage in the stress–strain curve, respectively, while \({\upvarepsilon }_{{\text{a}}}\) and \({\upvarepsilon }_{{\text{b}}}\) correspond to the strain values at these points.

Triaxial compression test

The triaxial tests applied a uniform confining pressure gradient ranging from 5 to 25 MPa to ensure multiple pressure levels and clear differential values. The confining pressure was initially increased at a rate of 2 MPa/min. Upon reaching the target confining pressure, axial loading was initiated under displacement control with a constant rate of 0.001 mm/min. A detailed summary of the testing parameters is provided in Table 3.

Using the experimental data, the cohesion and internal friction angle of the shale specimens were determined based on the Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion.

The peak stress and confining pressure of the shale specimen are denoted by \(\sigma_{1}\) and \(\sigma_{3}\), respectively. The cohesion and internal friction angle are represented by \(c\) and \(\varphi\) in Eq. (4).

Brazilian split test

Brazilian splitting tests were performed on standardized disc-shaped samples measuring 50 mm in diameter and 25 mm in thickness, with a constant displacement rate of 0.02 mm/min. The axial load and displacement of the specimen were recorded using a load head sensor. By varying the clamping angles, multiple tensile strengths corresponding to different bedding orientations and indirect tensile stress directions were obtained. Each test is conducted with three replicate experiments. The ultimate load of the shale specimens was determined from the Brazilian splitting test, and the tensile strength was calculated using Eq. (5).

In Eq. (5), \({\upsigma }_{{\text{t}}}\) and \({\text{F}}_{{\text{N}}}\) represent the tensile strength and ultimate load of the specimen, respectively. \({\text{d}}\) is the specimen diameter, and \({\text{t}}\) is its thickness.

Analysis and discussion

The mechanical behavior of shale is primarily influenced by its jointing patterns, a key characteristic of this lithology. However, systematic studies on the mechanical properties of shale from the Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin remain scarce. Analyzing both the static and dynamic mechanical behavior of these shales is crucial for guiding local shale gas development. Shales from the Yanchang Formation are noted for their low maturity and well-developed natural fractures, commonly observed in core samples and thin sections, with fracture widths typically ranging in the tens of micrometers27. This section examines the mechanical properties and failure modes of these samples under confining pressure, based on data from static and dynamic tests conducted on Yanchang Formation shales.

Dynamic mechanical analysis

Strength properties

Table 4 presents the stress–strain data of the specimens processed using the three-wave method, with corresponding curves shown in Fig. 4.

The dynamic compressive strength of shale exhibits a positive correlation with strain rate, indicating that higher strain rates lead to increased peak stresses during dynamic tests. Additionally, the dynamic compressive strength shows a U-shaped dependence on bedding angle, with elevated values observed at both low and high angles, as demonstrated in Fig. 5.

At a bedding angle of 0°, the peak stress increased by 1.183 MPa per unit strain rate (1 s–1), corresponding to an average rise of 102.33 MPa, or a 106% enhancement relative to the bullet pressure reference. For the 45° bedding angle, the peak stress increased by 0.731 MPa per unit strain rate, translating to an increase of 85.95 MPa, or 141%, compared to bullet pressure. At 90°, the increase was 0.683 MPa per unit strain rate, corresponding to a 76.69 MPa (62.5%) rise relative to bullet pressure.

The percentage increase in strength was smaller for the 0° and 90° bedding orientations, while the 45° orientation showed a significantly higher percentage increase. This trend aligns with the dynamic mechanical behavior reported by Sun et al.32 for Longmaxi Formation shales at different bedding angles.

At an equivalent strain rate, the Yanchang Formation shale displayed a dynamic compressive strength nearly 20 MPa lower than that of the Longmaxi Formation shale at 0°. At the 45° orientation, the Yanchang Formation shale exhibited a notably lower dynamic compressive strength—about 60 MPa less than the Longmaxi Formation. In contrast, the strength at 90° was comparable between the two formations. These results suggest that the extensive development of microfractures in the Yanchang Formation significantly reduces dynamic compressive strength, especially when shear failure predominates.

Under varying strain rates, shale specimens with a 0° bedding orientation showed the greatest increase in dynamic strength, whereas those with a 90° orientation exhibited the smallest increase. This difference stems from the distinct failure mechanisms associated with each orientation.

For specimens with a 90° bedding angle, the joint planes are oriented parallel to the propagating stress wave, resulting in failure dominated by matrix brittle cleavage and tensile fracture. At higher strain rates, matrix hardening within the thin bedding sections leads to an increase in peak stress.

In specimens with a 0° bedding angle, tensile failure is the dominant failure mode. As strain rates increase, the peak stress intensity shows more significant enhancement. This effect is driven by two primary mechanisms: the prevalence of microfractures oriented parallel to the bedding planes and the energy absorption from viscous mineral components located between the bedding structures.

In specimens with a 45° bedding angle, the acute angle between the bedding planes and the shock wave direction, combined with widespread microfractures within the bedding plane, reduces the shale’s shear strength. Under unconfined conditions, failure is strongly influenced by slip along the bedding planes, resulting in an initial strength considerably lower than the peak stresses observed in specimens where the stress wave is oriented either parallel or perpendicular to the bedding.

Failure modes

Energy absorption and conversion are key factors in understanding the failure behavior of rocks under compression. Peng et al.33 proposed that rock failure results from instability caused by energy conversion. Understanding how energy conversion varies with foliation angles is essential for elucidating the failure mechanisms of shale specimens. Using data from SHPB tests, the incident, reflected, transmitted, and absorbed energy for each specimen were calculated (Table 5). For example, with an incident energy of approximately 145 J corresponding to a bullet pressure of 0.1 MPa, the energy characteristics and failure modes of the Yanchang Formation shale were analyzed (Fig. 6).

As shown in Fig. 6, the failure behavior of shale samples varies significantly with bedding angle. The calculations reveal that absorbed energy decreases progressively as the bedding angle increases. Shale with a 0° bedding angle absorbs the most energy, while samples with a 90° orientation absorb the least. Energy dissipation occurs primarily during specimen failure. Sun et al.32 suggested that shale exhibits reduced energy dissipation with decreasing strength. At a bullet pressure of 0.1 MPa, shale with 90° bedding demonstrated slightly higher strength and less fragmentation compared to shale with 0° bedding. The number and extent of fractures also influence energy absorption. The failure mechanism of 0° bedding differs from the cleavage failure produced by 0° bedding. This process involves greater deformation and more severe fragmentation. Consequently, shale with 0° bedding absorbed the most energy, followed by shale with 45° bedding, while 90° bedding absorbed the least.

Shale specimens with both 0° and 90° bedding angles exhibit tensile splitting failure modes. Shale with 0° bedding fails primarily through matrix-dominated tensile fractures, where the propagation of major cracks is minimally influenced by the bedding structure. At elevated strain rates, the specimen fractures into two dominant pieces, accompanied by considerable fine debris. In contrast, shale with 90° bedding undergoes tensile fracture normal to the bedding orientation, with multiple cracks propagating along the bedding planes, leading to structural failure. As strain rates increase, the number of parallel main cracks rises, and fragmentation intensifies until the specimen is completely broken into fine fragments.

At low strain rates, shale with a 45° bedding angle exhibits predominantly shear failure, with principal cracks extending along the bedding planes. As strain rates increase, the failure mechanism transitions to a tensile-shear mixed mode34.

Static mechanical analysis

Uniaxial compression test

The results of the uniaxial compression tests are summarized in Table 6, with the corresponding stress–strain curves shown in Fig. 7.

Experimental observations indicate that the mechanical properties of Yanchang Formation shale exhibit significant anisotropy relative to bedding orientation. Specifically, the compressive strength follows a distinct U-shaped trend as the bedding angle varies, while the elastic modulus consistently increases with higher bedding angles.

These findings confirm that both uniaxial compressive strength and elastic modulus are highly sensitive to changes in bedding orientation. Due to the significantly weaker mechanical strength of the bedding planes compared to the shale matrix, specimens with inclined bedding fail rapidly under loading, resulting in a marked reduction in overall load-bearing capacity. Moreover, because of the weaker bedding planes, specimens with a 0° bedding orientation exhibit greater deformability and higher failure strain than those with a 90° bedding orientation.

Uniaxial compression tests reveal that shale specimens with varying bedding angles exhibit contrasting failure mechanisms, primarily shear and tensile failure. The progressive failure patterns observed at 0°, 45°, and 90° bedding angles are sequentially illustrated in Fig. 8.

The fracture behavior of the 0° bedding shale specimen differs from conventional single-inclined-plane shear failure. Due to the substantially weaker mechanical strength of the bedding cementation planes compared to the matrix, crack propagation is guided by these planes, leading to a combined failure mechanism35.

For the specimen with a 45° bedding angle, a typical single-inclined-plane shear failure occurs. Following shear failure, rapid sliding along the cementation plane causes the specimen to lose its load-bearing capacity quickly, resulting in a compressive strength considerably lower than that at the other two bedding angles.

For the specimen with a 90° bedding angle, the axial compression behavior resembles that of a non-bedded material. Under uniaxial compression, lateral deformation induced by the Poisson effect leads to interfacial tensile failure. The failure mode is characterized by a vertically penetrating failure surface along the cementation plane.

Triaxial compression test

Figure 9 presents the stress–strain curves from triaxial compression tests conducted on shale specimens. The results demonstrate a positive correlation between compressive strength and confining pressure, with significant variation across different bedding angles. Compressive strengths at 0° and 90° are notably higher than those at 45°. At a 90° bedding angle, the compressive strength approaches that of the rock matrix. Under both unconfined and increasing confining pressure conditions, compressive strength follows a U-shaped variation with respect to bedding angle.

The application of confining pressure suppresses fracture propagation along weak bedding planes, resulting in a failure mode dominated by the rock matrix. However, the bedding structure continues to influence the spatial distribution of residual fractures (Fig. 10). For specimens with a 0° bedding angle, failure under moderate confining pressure occurs via single-inclined-plane shear, while at higher confining pressures, it transitions to conjugate shear failure. In specimens with a 45° bedding angle, failure under confining pressure manifests as single-inclined-plane shear. For specimens with a 90° bedding angle, failure is characterized by tensile splitting, but confining pressure restricts lateral deformation, leading to a conjugate failure mode.

Brazilian disc test for tensile strength

The test data included axial load and axial displacement measurements recorded by the loading head sensor. The tensile strength of the specimen was calculated using Eq. (5) (Table 7).

Analysis of the quasi-static mechanical properties of shale specimens revealed the following trends: at a bedding angle of 45°, the elastic modulus increased by 14.8% compared to the 0° bedding, while compressive strength decreased by 47.6% and tensile strength dropped by 15.2%. In contrast, specimens with a 90° bedding angle showed a 181.6% increase in elastic modulus and a 42.1% increase in compressive strength, but a 43.9% reduction in tensile strength, relative to those with a 0° bedding angle. The weakly cemented interfaces between bedding planes are identified as the primary factors influencing the static mechanical properties and failure modes of shale Fig. 11.

The 0° bedding specimen fails through a primary fracture cutting across its central region, with subsidiary cracks extending along the bedding. In the 45° specimen, the initial main crack deflects toward the bedding plane, continuing along it until complete penetration occurs. Failure in the 90° specimen is characterized by an arcuate main fracture crossing the central zone and further propagating parallel to the bedding orientation.

Determination of shale HJC constitutive model parameters

HJC model

Widely used in dynamic analyses, the HJC model effectively characterizes the behavior of materials under high strain-rate deformation36. It consists of three primary components: a yield surface equation, an equation of state, and a damage evolution equation.

Equation (6) defines the strength plane of the HJC model. Here, \(\sigma^{*}\) represents the normalized equivalent stress, defined as the ratio of equivalent stress \(\sigma\) to quasi-static uniaxial compressive strength \({\text{f}}_{{\text{c}}}\); \(p^{*}\) is the normalized pressure, defined as the ratio of pressure \({\text{p}}\) to \({\text{f}}_{{\text{c}}}\); \(\dot{\varepsilon }^{*}\) denotes the normalized strain rate, defined as the ratio of strain rate \({\dot{\varepsilon }}\) to the reference strain rate \(\dot{\varepsilon }_{0}\); \({\text{D}}\) indicates the damage level; and \({\text{A}}\), \({\text{B}}\), \({\text{C}}\), and \({\text{N}}\) are strength surface parameters. \({\text{S}}_{{{\text{max}}}}\) represents the maximum normalized equivalent stress.

Equation (10) represents the damage evolution equation of the material, where damage accumulation is influenced by both volumetric strain and equivalent plastic strain. These four sets of equations describe the relationship between hydrostatic pressure P and volumetric strain \({\upmu }\) during different deformation phases. The equation of state is divided into three consecutive stages: elastic compression, plastic compaction, and the fully compacted response: (1) Elastic compression stage: \(P < P_{crush}\); Compaction deformation stage: \(P_{crush} < P < P_{lock}\); Post-compaction deformation stage: \(P > P_{lock}\)

Here, \({\text{K}}\) denotes the elastic bulk modulus; \(\mu_{plock}\) represents the dimensionless volumetric strain at which the material reaches the “locked” state, and \(P_{lock}\) is the corresponding pressure at that state; \({\text{K}}_{{\text{i}}} {\text{(i = 1,2,3)}}\) are pressure constants; and \(\overline{\mu }\) denotes the corrected volumetric strain.

Improved HJC model

The fundamental HJC strength equation incorporates a rate-dependent strength amplification term during dynamic response, determined by fitting SHPB and quasi-static strength test data. Since the fitted equation assumes a linear relationship between strengthening and the natural logarithm of strain rate, the fit becomes less accurate for materials exhibiting significant dynamic strengthening. At low strain rates, the discrepancy caused by the strength amplification term is minimal. However, as strain rate increases, the insufficient fit between parameters and experimental results leads to larger simulation errors. Experiments indicate that shale experiences slow strength growth at low strain rates and rapid growth at high strain rates. The segmented DIF introduces a two-stage dynamic strength amplification model based on impact tests. DIF parameters ensure accuracy at low strain rates while controlling errors as strain rates increase.

Replacing the strain rate term in the HJC model with a DIF improves the accuracy of the material’s mechanical behavior representation under high strain rates. Various formulations have been proposed to modify the strength enhancement term, such as using an exponential form or a piecewise function of strain rate in logarithmic coordinates. Based on SHPB experimental results for shale, a piecewise DIF expression is adopted, with distinct formulas applied in the low- and high-strain-rate regions. Consequently, the strength surface equation is modified as shown in Eq. (11).

The basic mechanical parameters include density (ρ), uniaxial compressive strength (\({\text{f}}_{{\text{c}}}\)), tensile strength (T), shear modulus (G), and bulk modulus (K). The values of \({\text{f}}_{{\text{c}}}\) and T are determined through uniaxial compression tests and Brazilian splitting tests, respectively Fig. 12.

The DIF is expressed as a piecewise linear function of \(\lg \dot{\varepsilon }^{*}\). Under high strain rate conditions \((\dot{\varepsilon }^{*} > 180s^{ - 1} )\), the strain rate sensitivity parameters m and n are fitted using the strain rate \(\dot{\varepsilon }^{*}\) and normalized stress \(\sigma^{*}\) obtained from SHPB experiments (Fig. 13). Since the normalized stress approaches 1 at the lowest tested strain rate, the DIF in the low strain rate region is defined as a linear function connecting the quasi-static reference point (\(\sigma^{*} = 1\)) to the fitted curve in the high strain rate regime. The parameters for the improved HJC model (Table 8, 9) and the RHT model (Table 10) are summarized below.

The shear modulus G and bulk modulus K are calculated using Eq. (12).

Based on uniaxial compression and Brazilian splitting tests, key mechanical parameters of shale at various bedding angles were derived using standard formulas, as summarized in Table 8.

When the M-C criterion follows a linear relationship, the normalized cohesion strength is expressed as the ratio of the square root of the sum of the squares of the intercept divided by the square root of the sum of the squares of the slope, and then divided by twice the compressive strength37. Ignoring the strength modification term due to the dynamic compressive strength factor, the strength surface equation for the HJC model is as follows:

The quasi-static strength surface equation includes three material constants that must be determined. These constants can be evaluated by first substituting triaxial compression test data into the equation, which allows for the calculation of parameter A and a series of coordinate points in the \({\upsigma }^{*} {\text{ - p}}^{*}\) coordinate system. These points are then fitted using known equations to obtain the three constants, as shown in.

The damage parameters \({\text{D}}_{{1}}\), \({\text{D}}_{{2}}\), and \(\varepsilon_{f\min }\)are determined by Eq. (14). It is typically assumed that \({\text{D}}_{{2}} { = 1}\); \(p^{*} = 1/6\). \(\varepsilon_{f\min }\) is taken as the ultimate strain of shale specimens from uniaxial compression tests.

Among the pressure parameters, \({\text{P}}_{{{\text{crush}}}}\) and \({\upmu }_{{{\text{crush}}}}\) represent the crushing pressure and crushing volumetric strain, respectively. \({\text{P}}_{{{\text{lock}}}}\) and \({\upmu }_{{{\text{lock}}}}\) denote the ultimate pressure and corresponding strain during the transition phase. \({\text{K}}_{{\text{i}}} {\text{(i = 1,2,3)}}\) are pressure constants, with values referenced from the original HJC model. \({\text{P}}_{{{\text{lock}}}}\) adopts the recommended value from the original HJC model. The remaining parameters are calculated using Eq. (15).

\(\rho_{g}\) and \(\rho_{0}\) represent the density of the material in its initial state and the density in its compacted state, respectively.

Model verification and validation

Model setup

LS-DYNA utilizes an efficient explicit time integration algorithm and offers robust capabilities for coupling nonlinear physical fields, making it ideal for simulating dynamic events such as impacts and explosions. To accurately capture material strain during dynamic response, an LS-DYNA model of the SHPB experimental setup was developed (Fig. 14).

In the SHPB experiment, the incident wave produced by the bullet’s impact on the input bar is shaped by a pulse shaper to approximate an ideal half-sine wave. For numerical efficiency, it is more practical to directly apply the experimentally measured incident wave to the end of the input bar, rather than explicitly simulating the bullet impact.

Monitoring points were placed on both the input and transmission bars to record strain histories. These data enable the derivation of the stress–strain response of the specimen using the three-wave method. A non-reflective boundary condition was applied at the far end of the transmission bar to simulate the damper used in the experiments, thereby preventing spurious wave reflections from interfering with the incident and transmitted stress signals.

The interface between the compression bars and the specimen was modeled using an erosion-based surface contact algorithm. To evaluate the performance of the improved HJC model under dynamic loading, corresponding parameters for the RHT model were also calibrated against experimental results (Table 10) for comparison. The "erosion surface contact" setting ensures that stress propagates smoothly even after contact surface elements fail, a feature commonly used in SHPB simulations to better replicate experimental conditions.

A mesh sensitivity study was conducted, leading to the selection of element sizes of 5 mm for the pressure bars and 1.25 mm for the specimen (Table 11).

Numerical simulation results and discussion

The strain history data acquired from monitoring points were separated into incident, transmitted, and reflected waves. The stress–strain curves, processed using the three-wave method, are shown in Fig. 15, 16. These curves represent simulation results for three different bedding angles.

For shale with a 0° bedding angle, both the HJC(DIF) and RHT constitutive models closely match the experimental results when the strain rate is below 188 s–1. The peak stresses and overall curves produced by both models are nearly identical. As the impact velocity of the projectile increases, the strain rate of the shale specimen also rises. When the strain rate exceeds 203 s–1, the numerical results from the two models diverge significantly. The RHT model shows a notably slower increase in stress. Although the initial slope of the stress–strain curve aligns with experimental data, the slope decreases markedly in the middle phase, resulting in a peak stress substantially lower than the experimental value. This indicates that the RHT model fails to accurately simulate the behavior of 0° bedding shale under high strain rates.

In contrast, the modified HJC model matches the experimental results well throughout both the initial and middle stages. The stress–strain response predicted by the HJC(DIF) model closely correlates with the experimentally measured behavior. These results demonstrate that replacing the original strain rate term in the HJC model with a DIF effectively captures the stress enhancement under high strain rates.

Similar trends are observed for shale with bedding angles of 45° and 90°. At lower impact velocities, both the RHT and HJC models produce results consistent with experimental data. However, as impact velocity increases, the RHT model significantly underestimates the stress. In contrast, the modified HJC model more accurately represents the strain rate effects under dynamic loading across all bedding angles.

The RHT model, a complex concrete model, considers three limit surfaces that jointly determine element strength. Many key parameters are interdependent and difficult to obtain directly through experiments. Acquiring true parameter values via orthogonal experiments and simulations is challenging. As such, concrete approximate materials can achieve ideal results when using reference-recommended values, but the simulation performance deteriorates when applied to non-concrete analogous materials. Shale’s damage mechanism differs from that of concrete, and using concrete-type failure evolution equations may lead to strength reduction. The failure process driven by shale anisotropy and strain rate effects requires modifications to the RHT constitutive model, particularly the hardening equation, strain rate effect equation, and damage equation.

The parameters of the original HJC constitutive model, calibrated based on experimental results, were also applied to numerical simulations of SHPB experiments. Results show that the original HJC model shares similarities with the RHT model: it agrees well with experimental results under lower impact pressure conditions. However, as impact pressure increases, the peak stresses obtained from simulations consistently fall below experimental values, suggesting that the original HJC model cannot accurately simulate the mechanical properties of shale under high strain rates.

For shale with other bedding orientations, it is recommended to interpolate the parameters provided in this study through fitting to obtain appropriate constitutive values.

Discussion of model limitations

This study did not account for the impact of temperature variations on the mechanical properties of shale. In actual reservoir environments, temperature gradients and thermal stresses can significantly alter shale strength, deformation characteristics, and failure modes. Future research should involve thermo-mechanical coupling tests to improve the model’s applicability under varying temperature conditions. Additionally, the rock samples used in this experiment were dry, whereas shales in actual reservoirs are often saturated with water or hydrocarbon fluids. Fluid-rock interactions and pore pressure effects may significantly influence the dynamic response of shale, but current models do not yet incorporate these complex multiphysics coupling effects. While this model demonstrates good predictive capability under conventional dynamic loading and specific experimental conditions, its applicability under extreme environmental conditions and complex multi-field coupling scenarios requires further validation and expansion. Future research should focus on developing a more comprehensive constitutive framework that is suitable for a broader range of engineering conditions.

Conclusion

-

(1)

Yanchang Formation shale exhibits significant anisotropy under both static and dynamic loading conditions. The compressive strength and elastic modulus follow a U-shaped relationship with bedding angle, with the lowest values at 45° and the highest at 90°, where the strength approaches that of the intact rock matrix.

-

(2)

SHPB tests reveal a positive correlation between dynamic compressive strength and strain rate, with the extent of strengthening varying significantly across bedding angles. Specimens with 0° and 90° bedding primarily fail in tension. Shale with 0° bedding absorbs the most energy and undergoes pulverization, while specimens with 90° bedding absorb the least energy and fail primarily by cleavage. At low strain rates, 45° bedding specimens exhibit shear failure, transitioning to tensile-shear composite failure at higher strain rates. Energy dissipation is closely linked to crack development.

-

(3)

Incorporating the DIF into the HJC constitutive model significantly enhances its ability to capture the high-strain-rate mechanical behavior of shale. Numerical simulations confirm that the modified HJC model outperforms the RHT model under high-velocity impact, demonstrating superior predictive performance in the high-strain-rate regime.

-

(4)

This study provides essential mechanical parameters and a validated constitutive model to support fracture design, wellbore stability assessments, and dynamic response analysis for shale gas development in the Ordos Basin. The results offer valuable insights for advancing emerging technologies, such as in-situ methane detonation fracturing. The improved HJC constitutive model is recommended for numerical simulations throughout various life cycle stages of shale gas wells.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhao, Q. et al. Shale gas resources/reserves calculation method considering the space taken by adsorbed gas. Nat. Gas Geosci. 34(2), 326–333 (2023).

Zhao, J. Z. et al. A review of deep and ultra-deep shale gas fracturing in China: status and directions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 209, 115111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2024.115111 (2025).

Jiao, F. Theoretical insights, core technologies and practices concerning “volume development” of shale gas in China. Nat. Gas Industry. 39(5), 1–14 (2019).

Mou, Y. L. et al. Geochemical characteristics of the shale gas reservoirs in Guizhou Province. South China. Arab. J. Chem. 17(3), 105616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2024.105616 (2024).

Zhang, Y. F., Li, D. X., Xin, G. M. & Ren, S. R. A review of molecular models for gas adsorption in shale nanopores and experimental characterization of shale properties. ACS Omega 8(15), 13519–13538. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c01036 (2023).

Jiang, K., Deng, S. C., Jiang, X. F. & Li, H. B. Calculation of fracture number and length formed by methane deflagration fracturing technology. Int. J. Impact Eng 180, 104701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2023.104701 (2023).

Yu, S. Y., Zhou, Y., Yang, J. & Chen, W. Q. Hydraulic fracturing modelling of glutenite formations using an improved form of SPH method. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 227, 211842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoen.2023.211842 (2023).

Liu, Y. L. et al. Influence of natural fractures on propagation of hydraulic fractures in tight reservoirs during hydraulic fracturing. Mar. Pet. Geol. 138, 105505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2021.105505 (2022).

Hu, G. J., Mian, H. R., Hewage, K. & Sadiq, R. An integrated hazard screening and indexing system for hydraulic fracturing chemical assessment. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 130, 126–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2019.08.002 (2019).

Bamberger, M. & Oswald, R. E. Long-term impacts of unconventional drilling operations on human and animal health. J. Environ. Sci. Health, Part A 50(5), 447–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/10934529.2015.992655 (2015).

Siegel, K. R. et al. Impact of real-life environmental exposures on reproduction: Evidence for reproductive health effects following exposure to hydraulic fracturing chemical mixtures. Reproduction 168(4), e240134. https://doi.org/10.1530/rep-24-0134 (2024).

Wang, J. W. et al. Numerical study of the fracture propagation mechanism of staged methane deflagration fracturing for horizontal wells in shale gas reservoirs. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 230, 212209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoen.2023.212209 (2023).

Qi, X. Y., Geng, D. D., Xu, M. Z. & Ting, K. Experimental and damage model study of layered shale under different moisture contents. Int. J. Damage Mech 33(7), 527–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/10567895241245753 (2024).

Ma, T. S., Yang, C. H., Chen, P., Wang, X. D. & Guo, Y. T. On the damage constitutive model for hydrated shale using CT scanning technology. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 28, 204–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2015.11.025 (2016).

Song, F., González-Fernández, M. A., Rodriguez-Dono, A. & Alejano, L. R. Numerical analysis of anisotropic stiffness and strength for geomaterials. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2022.04.016 (2023).

Ma, S. Q., Gutierrez, M. & Hou, Z. K. Coupled plasticity and damage constitutive model considering residual shear strength for shales. Int. J. Geomech. 20(8), 04020109. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)gm.1943-5622.0001721 (2020).

Guo, W. H. et al. Mechanical behavior and constitutive model of shale under real-time high temperature and high stress conditions. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 13(3), 827–841. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-022-01580-4 (2023).

Gao, W. L., Deng, G. Q., Sun, G. J., Deng, Y. J. & Li, Y. Dynamic mechanical properties of heat-treated shale under different temperatures. Appl. Sci. Basel 13(22), 12288. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132212288 (2023).

Wan, A. T., Tao, T. J., Tian, X. C., Xie, C. J. & Jia, J. Calculation method of HJC constitutive model parameters of natural joint angle slate. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 15271. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42544-w (2023).

Luo, N., Fan, X. R., Cao, X. L., Zhai, C. & Han, T. Dynamic mechanical properties and constitutive model of shale with different bedding under triaxial impact test. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 216, 110758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2022.110758 (2022).

Liu, W., Xu, X. Y. & Mu, C. M. Development of damage type viscoelastic ontological model for soft and hard materials under high-strain-rate conditions. Appl. Sci. Basel 12(17), 8407. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12178407 (2022).

Sun, B. et al. Research on deep-hole cutting blasting efficiency in blind shafting with high in-situ stress environment using the method of SPH. Mathematics 9(24), 3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9243242 (2021).

Sun, Y. Z. et al. A modified Holmquist-Johnson-Cook (HJC) constitutive model and its application to numerical simulations of explosions and impacts in rock materials. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 138, 103038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simpat.2024.103038 (2025).

Wu, G. L. & Wang, H. Nonlinear correction of elastic section in HJC constitutive model. Int. J. Impact Eng 189, 104955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2024.104955 (2024).

Jiang, K. et al. Dynamic constitutive modeling and numerical validation of composite toughened oil well cement for well cementing applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 456, 139193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.139193 (2024).

Xie, L. et al. Experimental study and theoretical analysis on dynamic mechanical properties of basalt fiber reinforced concrete. J. Build. Eng. 62, 105334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105334 (2022).

Gao, Z. D., Wang, Y. D., Gu, X. Y., Cheng, H. L. & Puppe, N. Characteristics and gas-bearing properties of Yanchang formation shale reservoirs in the southern ordos basin. Geofluids 2023, 5894458. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/5894458 (2023).

Huang, M. et al. A new representative sampling method for series size rock joint surfaces. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 9129. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66047-0 (2020).

Yao, W., Li, X., Xu, Y. & Wu, B. B. Preliminary Analysis of the End Friction Effect on Dynamic Compressive Strength of Rocks. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 57(10), 8899–8910. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-024-03950-2 (2024).

Wang, Z. X. et al. Dynamic mechanical properties of different types of rocks under impact loading. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 19147. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46444-x (2023).

Minju, Q., Xuan, Z., Yiding, W. & Guangfa, G. Analysis of stress, strain and Young’s modulus of specimens under propagation of the 1D linear elastic stress waves. Latin Am. J. Solids Struct. 20(11), e513. https://doi.org/10.1590/1679-78257848 (2023).

Sun, Q. et al. Study on the bedding effect and damage constitutive model of black shale under dynamic loading. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 38(7), 1319–1331 (2019).

Peng, K., Liu, Z. P., Zou, Q. L., Wu, Q. H. & Zhou, J. Q. Mechanical property of granite from different buried depths under uniaxial compression and dynamic impact: An energy-based investigation. Powder Technol. 362, 729–744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2019.11.101 (2020).

Feng, X. H. et al. Investigation on dynamic anisotropy of bedded shale under SHPB impact compression. Eng. Fract. Mech. 320, 111075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2025.111075 (2025).

Zhao, C., Zhang, R., Zhang, Q. Z., Du, S. G. & Yang, C. Y. Experimental study on the rift plane of granite under uniaxial compression. J. Appl. Geophys. 199, 104590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jappgeo.2022.104590 (2022).

Holmquist, T. J., Johnson, G. R., & Cook, W. H. (1993). A computational constitutive model for concrete subjected to large strains, high strain rates, and high pressures. In M. J. Murphy & J. E. Backofen (Eds.), Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Ballistics (591–600). National Defense Research Establishment, Sweden.

Wang, Z. L., Wang, H. C., Wang, J. G. & Tian, N. C. Finite element analyses of constitutive models performance in the simulation of blast-induced rock cracks. Comput. Geotech. 135, 104172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2021.104172 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2020YFA0711802). The authors would like to express their deepest gratitude for the generous support.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2020YFA0711802).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Q. L.: Theoretical derivation, Method validation, writing original draft, and the establishment of the numerical analysis model. S.C. D.: Editing and checking of manuscript, Theoretical derivation, Method validation. K. J.: Static Mechanics Experiments and Dynamic Mechanics Experiments. H.B.L.: Method validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Deng, S., Jiang, K. et al. Influence of bedding angles on dynamic properties of Yanchang shale and a DIF-based constitutive model. Sci Rep 16, 303 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29657-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29657-0