Abstract

In order to solve the key problems affecting the safety of the project, such as the collapse of the support part and break in the air of the reinforced concrete chimney during the blasting demolition, this paper carried out systematic monitoring and theoretical analysis based on the 180 m chimney demolition project. Based on the characteristics of the stress–strain carve of concrete, the progressive failure mechanism of the supporting part under blasting load is revealed, the static equilibrium equation considering the stress–strain distribution of the section is established, and the chimney instability discriminant model with the ratio of gravity moment to resistance moment as the core is proposed. The fracture dynamic model of the chimney above the blasting notch is further constructed, and the propagation characteristics of stress wave and the amplification law of dynamic strain along the elevation under impact load are clarified. The research shows that the support part is prone to compression failure under large eccentric compression, and the minimum residual bearing capacity must not be lower than the weight of the chimney, which is the key to prevent collapse. The dynamic strain in the middle of the chimney caused by the touchdown impact is higher than that at the bottom, and the elevation amplification effect increases with the increase of the chimney height, resulting in the most dangerous section position migrating from the middle and lower part to the middle and upper part. The instability criterion and fracture mechanism proposed in this study have important theoretical support and engineering guidance value for the safety control of blasting demolition of high-rise structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tall reinforced concrete chimneys are mainly demolished by blasting operation. Normally, A chimney will fall due to gravity after a perforation, opening in the bottom, explosive charge and blasting. For the blasting process of tall chimneys of about 180 m, some chimneys experience severe compression collapse at the bottom followed by breakage in the middle, called “bottom collapse” and “middle break”. In this case, the direction of collapse of the chimneys may be uncontrolled (Fig. 1). Both phenomena will lead to serious accidents.

The mechanical mechanisms involved in chimney collapse are complex. For the problem of the destruction mechanism of the residual wall in the chimney notch area, Chu Huaibao1 observed the force characteristics of the concrete at this location and concluded that the redistribution of stress and the formation of the neutral axis after the formation of the blast notch require a time of 0.5–3.0 s. Zheng Bingxu2 observed six reinforced concrete chimney notches and concluded that the residual walls of the notches were subjected to sudden self-weight loading after blasting, which would cause the bottom of the chimney to collapse in compression, showing large eccentric compression brittle fracture characteristics. Zheng Bingxu3 also analysed the compressive range of the residual wall section, that the notch angle should be 210°–230°. Xu Pengfei4 believes that the residual wall should not be crushed within 2–3 s after the formation of the blast notch, which is a condition to ensure that the chimney is smoothly tipped. Yan Zhixin5 established a model to calculate the stresses on the cross section of the residual wall and introduced a coefficient to consider the transient adjustment of the stresses.

For the phenomenon of “chimney breaking in two”, Yang6 established the calculation model of the internal force and the ultimate bearing capacity of the chimney section. He concluded that chimneys with a height of more than 150 m may fracture at about 1/3 of the height from the top after a 40° tilt. In addition, the higher the chimney, the earlier the failure occurs. Yan Zhixin7 concluded that the location and time of chimney failure are related to the shape of the opening and the material properties. Tang Hai8 concluded that chimneys are mainly subjected to bending damage and may also fracture in multiple sections. Hou Jixuan9 concluded that the fracture location of chimneys with uniformly varying wall thickness is 1/3 from the top, while chimneys with non-uniformly varying wall thickness generally fracture at a lower location.

For the dynamic response characteristics of chimneys, Yunjian Wang10 experimentally investigated the effects of stress wave period and intrinsic period of chimneys on the fracture location. Pallarés11 analyzed the damage phenomenon of masonry chimneys under seismic action by using a three-dimensional finite element model, and obtained the damage modes, maximum stresses and displacement characteristics of the structure. Wolf12 investigated the response characteristics of nuclear power plant chimneys under seismic and impact loading. Wilson13 proposed a nonlinear dynamic analysis method based on the response characteristics of 10 chimneys under seismic loading. Huang14 proposed a three-dimensional pushover analysis method for the dynamic response of chimneys. Minghini15 analyzed the seismic damage process of brick chimneys and elucidated the mechanism of damage of the upper part of the chimneys.

In summary, there have been a lot of studies on the instability, collapse, movement process and seismic response of reinforced concrete chimney blasting demolition, but there are few theoretical studies and predictions on the bottom collapse and middle break of chimney in the process of blasting demolition. In this paper, through the observation of the movement and fracture process of a 180 m high reinforced concrete chimney, the squat and early air fracture phenomena of chimney blasting demolition are analyzed and discussed, and the methods of judging or predicting instability, squat and early fracture are studied.

Case studies

Blasting design

The height of the demolished reinforced concrete chimney is 180 m, and the cubic compressive strength of the concrete is 30 MPa. The outer radius of the bottom of the chimney is 9250 mm with a thickness of 500 mm and the outer radius of the top is 3050 mm with a thickness of 200 mm. The axial reinforcement of the chimney cross-section is a double-layer reinforcement, with the outer vertical reinforcement Φ22mm@200 mm and the inner vertical reinforcement Φ16mm@200 mm; the outer ring reinforcement Φ18mm@200 mm; and the inner ring reinforcement Φ14mm@200 mm. There are 2 flue openings at the bottom of the chimney, the height of bottom edge of flue opening 1 is + 0.46 m, the height is 5.32 m, and the width is 5.40 m. There are two flue openings at the bottom of the chimney, flue opening 1 has an elevation of + 0.46 m, a height of 5.32 m and a width of 5.40 m; flue opening 2 has an elevation of + 7.50 m, a height of 5.32 m and a width of 5.40 m as shown in Fig. 2.

The blasting design of the chimney was carried out according to the ‘Safety Regulations for Demolition Blasting’ (GB13533-92). The blast opening was trapezoidal in shape, as shown in Fig. 2. The arc of the bottom edge of the opening is 216°, the height is 6.0 m, the bottom edge is 34.9 m. The elevation of the bottom edge is 0.5 m. The two sides of the opening are mechanically cut out of two triangular windows, the bottom edge is 2.0 m, and the opening angle is 30°. A total of 612 holes were drilled in the blast opening area, with a total charge of 124 kg of emulsion explosives, and the explosives in the holes were detonated simultaneously.

Monitoring design

In order to monitor the collapse process of the chimney, a dynamic photogrammetric system was placed at the blast opening of the chimney. The system consists of an industrial camera (with an acquisition frequency of 5000 Hz), a datum ruler, measurement markers, software and a computer. The system tracks a target point and measures the distance, speed and acceleration of its movement. Two miniature cameras (100 Hz frame rate) were used to monitor the deterioration of the concrete in the lower part of the chimney.

Process of bottom collapse

The monitoring videos show the following stages of destruction of the remaining reinforced concrete wall adjacent to the blast opening:

-

a.

Approximately 0.5 s after detonation, 2 cracks began to expand from the corners of the triangular windows in both sides of the blast opening. The angle between the initial expanded direction the horizontal plane is about 45° (Fig. 3a).

-

b.

Approximately 1.2 s after detonation, the crack extended horizontally along the chimney wall. Both left and right cracks extended towards the symmetry axis of the remaining wall (Fig. 3b).

-

c.

Approximately 2.0 s after detonation, the left and right cracks were fully joined (Fig. 3c).

-

d.

Approximately 4.0 s after initiation, the remaining chimney wall adjacent to the blast opening was crushed (Fig. 3d) and the chimney stopped moving downwards. At this stage, the concrete debris was continuously extruded and no stress cracks were observed. Therefore, the bottom wall of the chimney was damaged by compression.

-

e.

After the chimney collapsed, some of the rebar and concrete of the remaining wall was completely separated. Some vertical rebar was still connected to the foundation and was folded several times. The rest was broken. (Fig. 3e).

Photogrammetric monitoring of the top of the chimney showed that the movement process and the corresponding changes in the blast opening zone can be divided into the following stages (Figs. 4, 5 and 6):

-

a.

Approximately 1.8 s after the detonation, the chimney began to move downwards with increasing displacement and velocity. At this stage, the weight of the chimney was greater than the load-bearing capacity of the remaining wall at the bottom. The damage to the remaining wall increased over time and its load-bearing capacity gradually decreased.

-

b.

Approximately 2.1 s after detonation, the downward acceleration of the chimney increased suddenly. At this point, the residual load-bearing capacity of the wall was minimized, and extensive damaged concrete was extruded.

-

c.

2.1 s–3.1 s after detonation, the chimney’s acceleration gradually decreased, but its displacement and velocity continued to increase. At this time, the remaining wall was still damaged, but its load-bearing capacity was gradually increasing. This indicated that the contact area was gradually increasing, i.e., the damaged concrete below was being replaced by a larger area of undamaged concrete above. This was due to the fact that the unfolded residual wall was an inverted trapezoid.

-

d.

3.1 s after the detonation, the chimney velocity reached a maximum value of 5.96 m/s. At this time, the load-bearing capacity of the remaining wall was equal to the weight of the chimney.

-

e.

3.1 s–3.6 s after the detonation, the average velocity gradually decreased, indicating that the chimney had started to decelerate. At this time, the load-bearing capacity of the remaining wall was greater than the weight of the chimney and was gradually increasing, i.e., the area of the contact surface of the collapse was still increasing.

-

f.

At 3.6 s after detonation, the chimney’s acceleration reached a minimum value. At this point, the chimney was in a significant state of overweight and the physical strength of the chimney was almost twice its weight.

-

g.

3.6 s–4.1 s after detonation, the average velocity of the chimney gradually become 0, the displacement reaches a maximum value of about 7.6 m.

-

h.

After 4.1 s of detonation, the chimney continued to rotate in the direction of collapse and its displacement, velocity and acceleration continued to change.

The movement of the chimney showed that it underwent some weightless and overweight process. This process must cause the dynamic response of the chimney.

Process of middle break

About 2 s after the end of the collapse process at the bottom of the chimney (Fig. 7a) (about 6.4 s after the detonation), the damage of the wall occurred at the 101 m elevation. The video shows that the concrete at this location was crushed and dropped, which is similar to the damage process of the concrete at the bottom of the chimney (Fig. 7b). It can be inferred that the main cause of the breakage in the middle of the chimney should be the compression damage of the concrete. After the chimney broke into two halves, it continued to rotate in the set direction. About 8 s after detonation, the upper and lower parts of the chimney were separated and had different trajectories (Fig. 7c). About 12.5 s after detonation, the upper part of the chimney fell to the ground. About 14 s after detonation, the lower part of the chimney fell to the ground (Fig. 7d).

Prediction model of chimney instability bottom collapse

The evolution process of support zone during bottom collapse

According to the stress characteristics of the chimney support area and the field observation results, and considering the full stress–strain curve characteristics of the concrete compression failure process (Fig. 8), the instability process of the support area can be divided into the following four stages.

-

(1)

Stress transient adjustment after detonation.

When the blasting notch is formed, the stress transient adjustment will occur in the support area, and the load borne by the blasting notch will be quickly transferred to the concrete in the support area.

-

(2)

The flexural capacity of the normal section of the support area reaches the peak.

After the stress transient adjustment is completed, the retained support area becomes a large eccentric compression member (Fig. 9a). Steel and concrete will exert the maximum bearing capacity of the material to resist overturning moment and vertical pressure. According to the stress and deformation characteristics of large eccentric compression members, the stress and strain are the largest at the farthest distance from the neutral axis on the cross section of the support zone. At the same time, because the yield strain of concrete is much lower than the yield strain of steel bar, the concrete in the support zone near the directional window is first compressed and yielded, and the resistance moment of the whole section reaches the peak or near the peak (Fig. 9b). If the resistance moment of the support area is greater than the overturning moment, the concrete will not be further damaged, and the chimney will not be successfully toppled. If the resistance moment of the support area is less than the overturning moment, the concrete will be further damaged, and the chimney can continue to rotate.

-

(3)

The compressive bearing capacity of the normal section of the support area reaches the peak.

When the chimney collapses, with the increase of its rotation angle, the strain on the cross section of the support area will continue to increase, and the position of the neutral axis will change. When the neutral axis of the support area disappears, the cross section of the whole support area is in a state of compression. From the characteristics of the total stress–strain curve of concrete, it can be seen that after the concrete reaches the yield state, its bearing capacity will continue to decrease with the increase of strain until it reaches a certain residual strength and becomes a plastic material. Therefore, when the neutral axis just disappears, the compressive stress distribution of concrete on the section corresponds to its strain, which is at different stress values of the full stress–strain curve of concrete, and the section of the support area reaches its maximum vertical bearing capacity (Fig. 9c).

-

(4)

Formation or bottom collapse of plastic hinge in support zone.

Under the action of overturning moment, the strain of concrete will continue to increase, so in general, the whole support area will eventually become ‘plastic hinge’. At this time, the concrete in the support area only has residual bearing capacity (Fig. 9d–f). When the weight of the chimney is less than or equal to the residual bearing capacity of the support area, the chimney is uniformly damaged, slowly sits down and continues to rotate. When the weight of the chimney is greater than the vertical residual bearing capacity of the support area, the chimney will obtain a certain vertical acceleration and then accelerate the bottom collapse and rotate synchronously. However, due to the fast speed and short duration of the bottom collapse, the deflection angle of the chimney during the bottom collapse process is generally small.

Force and instability discrimination of support area

In order to improve the reliability of blasting cut design, it is necessary to compare and identify the instability of different design schemes when demolishing chimney by blasting. In order to simplify the calculation, the traditional instability discriminant mechanical model usually assumes that the tension zone and the compression zone fully reach the ultimate bearing state, which is significantly different from the actual stress state of the support zone. The stress and strain near the neutral axis of the supporting area are small, and the strain is the largest at the front and rear edges (but the stress is not necessarily the largest).

In a short time after the initiation, the cylinder wall of the support area is in a low strain state. Therefore, it can be considered that the vertical strain at the neutral axis is 0, and the strain of the concrete on both sides of the neutral axis is linear with the distance from the neutral axis. That is, the yield strain of the outer edge of the concrete compression zone is εc, which will gradually decrease to 0 at the neutral axis.

As shown in Fig. 10a, it is assumed that the radian corresponding to the unilateral compression zone (1/2 of the compression zone) on the cross section of the chimney support zone is β, and its initial radian in the polar coordinate system is α. The radian corresponding to the unilateral tension zone (1/2 of the tension zone) is π/2 − α − β, and its initial radian is α + β. Assuming that the outer radius of the cylinder wall is r1 and the inner radius is r2, the concrete strain εφ at the polar angle α + φ in the compression zone can be expressed as:

In the formula: \(\overline{r}\) ̄is the average value of the outer radius r1 and the inner radius r2 of the cylinder wall, and φ is the polar angle radian value of a point in the cross section of the support area.

The radian of the micro-element of the cylinder wall in the support area is dφ, and the area of the micro-element is \(\delta \overline{r}d\phi\). The resultant force Ppc of the vertical pressure on the compression zone is:

In the formula: δ is the thickness of the tube wall in the support area, Ec is the elastic modulus of concrete.

Similarly, when the polar angle of a single steel bar in the support area is known, the pressure, tension and resultant force of a single steel bar can also be obtained. However, in the process of blasting design, the positioning of the steel bar is difficult, and the calculation of the force of the steel bar is also complicated. Therefore, the steel mesh can be equivalent to a thin-walled cylinder for calculation. When ignoring the thickness of the protective layer of the steel bar, after the steel mesh is equivalent to the steel cylinder, the equivalent wall thickness δs1 and δs2 of the steel cylinder can be expressed as:

In the formula, As1 and As2 are the cross-sectional area of the outer and inner vertical main reinforcements at the bottom section of the support area, and Δs1 and Δs2 are the spacing between the outer and inner reinforcements.

Similar to the formula (2), the vertical force Pps of the inner and outer steel tube is obtained as follows:

In the formula: Es is the elastic modulus of steel bar.

Similarly, the vertical tension Ptc of the concrete in the tension zone of the support area is:

The vertical tension Pts of the steel bar in the tensile zone is:

It should be pointed out that the exposed steel skeleton in the cut area after blasting also has a certain bearing capacity, but in engineering practice, the height of the blasting cut is often high, and the explosion load will cause the vertical steel bar to bend. Therefore, when the vertical bearing capacity of the steel skeleton in the cut area after blasting is low, the contribution of the vertical bearing capacity can be ignored.

It is assumed that after the stress is readjusted, the chimney is in a critical instability state, and the strain at the edge of the compression zone just reaches the yield strain. At this time, the chimney is in a static equilibrium state and no accelerated rotation occurs. The resultant force of the weight G of the chimney and the vertical force of the support zone is 0, and the equilibrium equation is obtained:

In the formula: G is the total weight of the chimney.

The formula (2), (4)–(6) are substituted into the formula (7) and simplified to obtain:

Equation (8) is a transcendental equation without analytical solution. In order to facilitate the engineering application, the Taylor series is used to expand the trigonometric function. After simplification, the approximate solution of β is obtained as follows:

In the formula:

In the process of engineering design, after the initial determination of α, the radian β corresponding to the middle compression zone of Eq. (8) can be solved by trial algorithm, or β can be calculated by approximate solution (9), so as to determine the position of the neutral axis and further check whether the chimney can lose stability.

Similarly, under the same basic assumption as Eq. (7), let θ = α + β, the resistance moment Mpc generated by the concrete in the 1/2 compression zone is:

After the steel bar is equivalent to a steel cylinder, the resistance moment Mps generated by the steel bar in the 1/2 compression zone is:

The ultimate resistance moment Mts produced by the steel bar in the 1/2 tension zone is:

When the chimney is to break the static equilibrium state and accelerate the rotation, the overturning moment formed by gravity is greater than the resistance moment. Ignoring the resistance moment generated by the concrete in the tensile zone, the instability condition of the chimney is:

The overturning instability coefficient f is defined as:

The instability coefficient f of the chimney can be calculated from (10)–(12) and (14).

According to the stress–strain characteristics of concrete and its distribution on the cross section of the support zone, when the concrete at the edge of the support zone just enters the plastic state, f = 1; Assuming that all the compression zone enters the plastic state and the concrete material is ideal elastic–plastic material, f = 2; Assuming that half of the compression zone enters the plastic state and the concrete is an ideal elastic–plastic material, f = 1.5. Obviously, f = 1.5–2 can meet the requirements of instability. When f > 2, the overturning moment is too large, which may lead to rapid crushing of the support area and bottom collapse.

Chimney sitting prediction

When the chimney opening is blasted, the stress field at the bottom is transiently adjusted. The load on the opening is transferred to the rest of the wall. This part of the chimney wall will resist the weight and moment of the chimney. If the resisting moment of the remaining wall is less than the applied moment, the concrete will be damaged and the chimney will rotate and collapse. As the chimney rotates, the concrete at the ‘fulcrum’ is continuously crushed and becomes a ‘plastic hinge’. At this point, the concrete wall will yield to the bending moment, leaving the concrete at the crushed surface with only residual strength. (The concrete on the crushed surface will only reach its ultimate strength if there is no further damage to the rest of the wall).

Therefore, if the weight of the chimney is greater than the vertical residual bearing capacity of the remaining wall, the remaining wall will collapse and the chimney as a whole will accelerate downwards and rotate simultaneously. The discriminating criterion for the collapse of the chimney bottom is expressed as follows:

where σcr is the residual concrete strength and s is the cross-sectional area of the remaining wall.

The blast opening of the stack is generally positive trapezoidal and the remaining wall is inverted trapezoidal (Fig. 10). If the area of the bottom surface of the remaining wall is smin and the area of the top surface is smax, the relationship between the collapse state of the remaining wall and its load-bearing capacity can be described as the following three cases:

-

(1)

If the weight of the chimney is greater than the maximum residual bearing capacity of the remaining wall, the remaining wall will collapse violently and disappear completely. This can be expressed by the following inequality:

$$mg > s_{{{\text{max}}}} \sigma_{{{\text{cr}}}}$$(16) -

(2)

If the weight of the chimney is greater than the minimum residual bearing capacity of the remaining wall and less than its maximum residual bearing capacity, the remaining wall will partially or completely collapse. This can be expressed by the following inequality:

$$s_{{{\text{min}}}} \sigma_{{{\text{cr}}}} < mg < s_{{{\text{max}}}} \sigma_{{{\text{cr}}}}$$(17) -

(3)

If the weight of the chimney is less than the minimum residual bearing capacity of the remaining wall, the remaining wall will collapse slightly or not collapse at all. This can be expressed by the following inequality:

$$mg < s_{{{\text{min}}}} \sigma_{{{\text{cr}}}}$$(18)

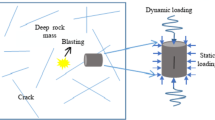

Prediction model of middle break

Many engineering cases have shown that tall chimneys generally break after the collapse of the remaining wall adjacent to the blast opening. Therefore, the dynamic response of the chimney can explain its failure mechanism.

When the bottom of the chimney collides with the foundation, dynamic compressive stresses and strains are inevitably generated at the contact surface and propagate to the top in the form of waves. According to the Saint–Venant principle, the localized concentrated stresses at the bottom of the chimney will evolve into relatively uniform stresses in the distant zone. Therefore, the unit cell away from the blast opening can be analyzed by simplifying the model to a one-dimensional straight rod with variable cross-section. Furthermore, only one stress wave propagation process is considered in the middle of the chimney, processes such as wave incidence and reflection at the boundary can be neglected. Therefore, a microelement in the middle section of the chimney is analyzed as shown in Fig. 10.

According to D’Alembert’s principle, the equilibrium equation for the microelement can be expressed as:

where, σ is the vertical stress in the cross-section and A is the cross-sectional area.

Assuming that the chimney cross-section varies continuously with the chimney height L, it can be expressed as:

where: κ, λ are coefficients, x is the height of the section from the ground and L is the total height of the chimney.

After inserting Eq. (20) into Eq. (19), simplifying and omitting higher order terms, Eq. (19) is reduced to:

Further simplification gives:

Assuming that reinforced concrete is a linear elastic material, the fluctuation equation is obtained by inserting \(\sigma { = }E_{{\text{c}}} \frac{\partial u}{{\partial x}}\) into Eq. (22).

where, cp is the sonic wave speed in reinforced concrete, \(c_{{\text{p}}} { = }\sqrt {E_{{\text{c}}} /\rho }\).

The top of the chimney is a free boundary and its strain is always 0. Then the boundary condition at the top of the chimney is:

The displacement of the chimney at t = 0 is 0. The velocity of the chimney at the moment t is vt. Then the boundary condition at the bottom of the chimney is:

It is assumed that the chimney is moving with a velocity v0 at t = 0 and will gradually decrease to 0. Based on the characteristics of the downward movement of the chimney (Fig. 5), a trigonometric function is fitted to vt as:

where, t0 is the time taken for the chimney velocity to decrease from v0 to 0.

The chimney is accelerated by the force of gravity and the residual bearing force of the remaining wall. During the acceleration phase of the chimney movement, the area in contact with the foundation is close to smin. Its acceleration a is:

Let the height of the chimney bottom collapse be h. According to the relationship between distance, velocity and acceleration of motion, v0 can be expressed as:

Inserting Eq. (27) into Eq. (28) gives:

During the reduction of the velocity of the chimney from v0 to 0, it is assumed that the foundation provides a deceleration resistance F. This is derived from the principle of conservation of momentum:

During the reduction of the chimney velocity from v0 to 0, F is reduced from the ultimate bearing capacity of the remaining wall to the weight of the chimney. During the deceleration phase of the chimney movement, the area in contact with the foundation approaches smax. Therefore, F is taken as an average value:

where σc is the compressive strength of concrete, η is the dynamic improvement coefficient of the compressive strength of concrete.

Inserting Eq. (31) into Eq. (30) gives:

Equation (23) can be solved using Eqs. (24), (25), (26), (29) and (32) as boundary conditions. After obtaining the solution, the vertical strain \(\frac{\partial u}{{\partial x}}\) in the chimney section at height x can be obtained. If the strain is greater than the compressive yield strain within a certain range, it can be determined that the chimney will break.

Validation of the prediction model

Validation case

The predictive model was validated on another 180 m chimney in Qinghai Province, China, with the structural parameters shown in Tables 1, 2 and 3. A positive trapezoidal blast opening was used in the chimney, located at the bottom of the chimney at an elevation of 0.5 m.

The judgment of bottom collapse

The weight of the chimney is:

Thus, the residual load-bearing capacity of the remaining wall satisfies the following conditions:

The analysis showed that the collapse of the remaining wall at the bottom of this chimney would occur. The most unfavorable result would be that the blast opening would close completely during the collapse process, preventing the chimney from falling successfully.

The judgment of middle break

Based on the ratio of the weight of the chimney to the load bearing capacity of the remaining wall, the collapse displacement is assumed to be 4 m. Calculated results of v0 and t0 are shown in Table 4.

Substituting v0 and t0 into Eq. (26) and solving the Eq. (23) by coupling Eqs. (24), (25), (26) gives the displacement \(u\left( {x,t} \right)\) and the strain \(\frac{{\partial u\left( {x,t} \right)}}{\partial x}\) distribution along the chimney (As shown in Fig. 11). The calculation results show that with the increase of the cross-sectional elevation of the chimney, the axial peak strain increases first and then decreases. Suppose a strain amplification factor ξ. ξ = arbitrary section peak strain/bottom peak strain. For heights between 60 and 110 m, ξ > 1.2. The maximum value of ξ is at 90 m, where ξmax = 1.34. Therefore, the probability of breaking at this location is high.

Blasting results

After detonation at the bottom of the chimney, the cracks spread rapidly horizontally from the edge of the opening. The remaining concrete wall was then crushed and collapsed. The collapse took approximately 4 s (Fig. 12). The collapse height was approximately 8 m, including 5 m of the remaining wall and 3 m of the intact cylinder wall.

At the end of the collapse, at a height of about 90 m, the chimney broke into two parts. The upper half continued to rotate in its original direction. The lower half did not collapse further (Fig. 13).

Discussion

From the above case of air fracture induced by the 180 m high chimney sitting down, it can be seen that the impact load generated by the sitting down can cause damage or even fracture of the chimney. In order to analyze the fracture risk of other common reinforced concrete chimneys, five typical chimneys were analyzed. It is assumed that the maximum velocity of the collision base of the chimney is 3 m/s, and the velocity drops to 0 after 0.06 s. Ignoring the gradual attenuation of the additional dynamic strain along the chimney axis, the calculation results (Table 5) show that the maximum dynamic strain amplification factor ξ of the chimney increases from 1.093 to 1.728 with the increase of the chimney height. The higher the chimney, the greater the dynamic strain amplification coefficient, and the greater the risk of fracture. And with the increase of the chimney height, the relative height of the maximum dynamic strain amplification coefficient of the chimney also increases, from the middle and lower part of the chimney to the middle and upper part of the chimney. In fact, when considering the attenuation of additional dynamic strain with propagation distance, the possibility of aerial fracture of high chimney is higher, while the possibility of aerial fracture of low chimney is lower.

From the above analysis, it can be seen that avoiding chimney sit-down or avoiding hard landing is an important measure to prevent the early air fracture of the chimney. The following methods can be used:

-

(1)

Optimize the shape of blasting cut, change the trapezoidal cut into triangular cut or trumpet cut, so that the cross-sectional area of the support area gradually transitions to the entire ring section, increase the ultimate bearing capacity of the support area, and avoid the support area being crushed by the instantaneous overall collapse;

-

(2)

The central angle of the blasting cut should be optimized. When the overturning condition is satisfied, the residual bearing capacity of the support area should be considered, and the speed of the bottom collapse should be reduced by increasing the cross-sectional area of the support area;

-

(3)

If necessary, the concrete in the support area should be strengthened to improve its compressive strength.

Conclusions

When blasting chimneys is over 150 m, the phenomenon of collapse at the bottom and breakage in the middle often occurs. This is a difficult engineering problem that affects the safety and effectiveness of the blast. Based on typical engineering cases, the characteristics of bottom collapse and middle break are analyzed and the mechanisms of these two phenomena are studied, and the following conclusions are reached.

-

(1)

The traditional chimney blasting design method holds that the ultimate bearing capacity of the axial compression of the support area is greater than the weight of the chimney, which can prevent the crushing of the support area. However, the support area is actually in the state of large eccentric compression. Therefore, the stability condition of the axial compression of the normal section cannot be used as the criterion for sitting down.

-

(2)

The compressive failure of the concrete in the support zone under the action of large eccentric compression is inevitable. The minimum residual bearing capacity of the support zone is less than the weight of the chimney, which is a necessary condition for the determination of the bottom collapse.

-

(3)

At the end of the bottom collapse stage of a concrete chimney with a height of more than 100 m, the bottom end of the chimney collides with the foundation to produce an impact load, and the strain value induced in the middle of the chimney may be greater than the failure strain at the bottom end, that is, the induced dynamic strain elevation amplification effect. This phenomenon is the main reason for the early fracture of the chimney.

-

(4)

The higher the chimney, the more significant the dynamic strain elevation amplification effect, and the greater the risk of fracture. With the increase of the height of the chimney, the relative position of the maximum dynamic strain amplification factor of the chimney also changes, which will be moved from the middle and lower part of the chimney to the middle and upper part of the chimney.

Data availability

All data, models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chu, H. B., Xu, P. F., Ye, H. Y. & Yang, X. L. Collapse process and load-bearing process of reinforced concrete chimney during blasting demolition. J. Vib. Shock. 34, 183–186 (2015).

Zheng, B. X., Wei, X. L. & Chen, Q. S. Study on damage surveying of cutting-support of high reinforced concrete chimney demolished by blasting. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 25(SUPPL. 2), 3513–3517 (2006).

Zheng, B. X., Wei, X. L. & Chen, Q. S. Mechanical analysis of cutting-support destabilization of high reinforced concrete chimney. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 26(SUPPL. 1), 3348–3354 (2007).

Xu, P. F., Liu, D. S. & Zhang, Y. C. Numerical study on the directional blasting collapse process of chimney with high combined incision. J. Vib. Shock. 36(15), 265–270 (2017).

Yan, Z. X., Ye, Z. H., Liu, P. L. & Cao, X. H. Collapsing process of high reinforced concrete chimney in blasting demolition. J. Vib. Shock. 30(9), 197–201 (2011).

Yang, J. H., Ma, Y. Y., Lu, W. B., Shun, J. S. & Chen, M. Analysis of fracture mechanics for falling tall chimneys during demolition blasting. Rock Soil Mech. 32(2), 459–464 (2011).

Yan, Z. X., Ye, Z. H. & Liu, P. L. Collapsing process of chimney demolition by directional blasting. Explos. Shock Waves. 30(6), 607–613 (2010).

Tang, H., Liang, K. S. & Zhang, C. L. Mechanics analysis of fall-down process of chimney by blasting demolition. Blasting. 20(1), 9–11 (2013).

Hou, J. X., Li, Z. A., Guo, X. & Niu, Z. H. Mechanical analysis of the non-uniform falling chimney. Coll. Phys. 36(6), 50–51 (2017).

Wang, Y. J. Longitudinal shock test and analysis on chimney models. Mech. Eng. 22(2), 41–43 (2000).

Pallarés, F. J., Agüero, A. & Martín, M. Seismic behavior of industrial masonry chimneys. Int. J. Solids Struct. 43(7–8), 2076–2090 (2006).

Wolf, J. P. & Skrikerud, P. E. Collapse of chimney caused by earthquake or by aircraft impingement with subsequent impact on reactor building. Nucl. Eng. Des. 51(3), 453–472 (1979).

Wilson, J. L. Earthquake response of tall reinforced concrete chimneys. Eng. Struct. 25(1), 11–24 (2003).

Huang, W. & Gould, P. L. 3-D pushover analysis of a collapsed reinforced concrete chimney. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 43(11–12), 879–887 (2007).

Minghini, F., Milani, G. & Tralli, A. Seismic risk assessment of a 50 m high masonry chimney using advanced analysis techniques. Eng. Struct. 69, 255–270 (2014).

Funding

This study was sponsored by the 2022 Hubei Province Higher Educational Institutions Outstanding Young and Middle-aged Science and Technology Innovation Team Program, 2022 Municipal Colleges and Universities Industry—University—Research Achievements and 2021 Jianghan University Science and Technology Innovation Project. Key Research and Development Program of Hubei Province (2020BCA084, 2021BAD004); cXY202209, a production-study-research combination project of universities in Wuhan; science and Technology Innovation Project of Jianghan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.L. completed the whole thesis writing work; J.S. provided fund support and thesis guidance, as well as experimental scheme design work; X.H. was responsible for the overall planning and arrangement of the field test; Y.J. provided technical guidance and field test conditions; Y.Y. provided theoretical analysis; Y.X. was responsible for the draft. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Q., Sun, J., Jia, Y. et al. Observation and prediction of bottom collapse and middle break phenomena in the blasting demolition of high chimneys. Sci Rep 15, 45577 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29662-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29662-3