Abstract

Cultural heritage preservation has garnered global attention. Museum artifact classification, a core task, faces challenges related to insufficient multimodal information collaboration and a scarcity of high-quality annotated data. Traditional methods and single-modality deep learning models struggle to achieve both efficiency and accuracy. To address this, this paper proposes a museum artifact classification model (VBG Model) based on cross-modal attention fusion and generative data augmentation. This model constructs an integrated multimodal framework through task-oriented refactoring of the Vision Transformer (ViT), BERT, and a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). ViT extracts global visual features from artifact images, while BERT mines the historical and cultural semantics of text. A bidirectional interactive attention fusion layer achieves precise feature alignment. The GAN generates diverse samples, forming a closed “generation-feedback-optimization” loop to alleviate data scarcity. Experiments on the MET and MS COCO datasets demonstrate exceptional performance: the VBG Model achieves 92% classification accuracy, 0.85 mAP, and 88% F1 score for the former, while the latter achieves 90% accuracy, 0.83 mAP, and 86% F1 score for the latter. These performance indicators outperform competing models such as ResNet and DenseNet. Ablation experiments confirm that cross-modal fusion and generative data augmentation modules are essential; removing either module results in a 5%-9% drop in accuracy. The current model still has room for improvement in terms of training time and generated image quality. Future work will focus on optimizing performance through lightweight design and multi-scale fusion, enhancing the ability to distinguish similar artifacts and providing technical support for digital artifact management and cultural heritage preservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the tide of the times of cultural heritage protection and inheritance, museums are important carriers of cultural treasures, and the accurate classification of their collections is a key link in achieving efficient management and knowledge mining1.However, traditional cultural relics classification methods mostly rely on manual labeling, which has problems such as low efficiency, strong subjectivity, and difficulty in large-scale processing2.Deep learning has demonstrated significant advantages in the field of cultural relics classification due to its powerful automatic feature extraction capabilities3,4.It can autonomously learn feature patterns from massive cultural relic images and text data, avoiding the limitations of hand-crafted features in traditional methods and greatly improving classification efficiency and accuracy5.

However, existing deep learning models still have obvious shortcomings when applied to museum cultural relic classification. On the one hand, cultural relic data naturally has multimodal properties, and single-modal deep learning models are difficult to fully capture the complete information of cultural relics6. The existing cross-modal fusion methods still have technical bottlenecks in feature alignment and semantic association, and cannot give full play to the synergistic advantages of multimodal data. On the other hand, due to the uniqueness and preciousness of cultural relics, it is extremely difficult to obtain high-quality annotated data7. The scarcity of data can easily lead to model overfitting and insufficient generalization ability, making it difficult to cope with the complex and changeable cultural relic forms and background interference in real scenes8. The existence of these problems has made the performance of current deep learning technology in cultural relics classification tasks not yet ideal, and new technical solutions are urgently needed to fill the research gap4.

This study is committed to designing a multimodal cultural relics classification model (VBG Model) based on the fusion and collaboration of BERT, Vision Transformer (ViT) and Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), aiming to break through the limitations of traditional methods, achieve deep fusion and data enhancement of cross-modal data, and thus improve the accuracy and robustness of museum cultural relics classification. The model consists of three core modules: BERT9 is responsible for processing text data related to cultural relics and mining the semantic information contained therein; Vision Transformer (ViT)10 focuses on feature extraction of image data and captures the visual details of cultural relics; GAN10 enhances the diversity of data sets through data generation, optimizes model training effects, and improves the adaptability of models in complex scenarios.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

-

A bidirectional attention fusion mechanism combining ViT and BERT is proposed to address the lack of feature alignment in traditional cross-modal models for cultural relic classification, deepening the connection between visual details and textual semantics.

-

A closed-loop “generation-feedback-optimization” framework combining GANs and bimodal modules is constructed, providing a new model training paradigm for multimodal classification in the context of scarce cultural relic data.

-

The research results can not only be directly applied to the digital management of museum cultural relics, promoting the intelligent development of cultural heritage preservation, but also provide valuable insights for other fields involving multimodal data processing and scarce data classification, such as medical image analysis and ancient document recognition.

The structure of this paper is as follows: The second part reviews the research in related fields and analyzes the achievements and limitations of existing studies; the third part elaborates in detail on the architectural design and working principles of the VBG model; the fourth part validates the performance of the model through experiments and conducts an in-depth analysis of the results; finally, the fifth part summarizes the research findings and looks ahead to future research directions.

Related works

Museum relic classification research

As a key link in the digital protection of cultural heritage, the classification of museum artifacts has long attracted academic attention. Early studies mostly used traditional machine learning methods, such as support vector machines (SVM) and random forests, to manually extract visual features such as color and texture of artifact images, or process text descriptions using bag-of-words models to achieve the classification of artifacts11. However, these methods rely on artificially designed features, and the efficiency and accuracy of feature extraction are difficult to guarantee when faced with complex and changeable artifact forms. Taking the classification of bronze artifacts as an example, traditional methods often cause classification errors due to feature extraction bias when identifying artifacts with severe rust and blurred patterns12. With the rise of deep learning, CNNs have made significant breakthroughs in the task of classifying artifact images with their powerful image feature learning capabilities13. For example, network structures such as ResNet and DenseNet can effectively extract deep semantic features of artifact images by deepening the network layer, thereby improving classification accuracy14. In the classification of ceramic artifacts, CNN-based models can accurately capture subtle differences such as glaze color and shape, and the classification accuracy is significantly improved compared to traditional methods.

However, most existing studies focus on single-modal data, make insufficient use of text descriptions of cultural relics, and lack effective strategies for dealing with data scarcity15. Many museums’ text records of cultural relics contain rich information such as historical background and production process. These text information combined with image data can provide a more comprehensive basis for classification, but current research has failed to fully tap this potential16,17. At the same time, due to the preciousness and uniqueness of cultural relics, it is difficult to obtain a large amount of annotated data, and insufficient model training data leads to limited generalization ability18. The VBG Model proposed in this study will fully explore the potential information of cultural relic images and texts through the combination of Vision Transformer (ViT) and BERT, and use GAN to solve the problem of data scarcity, providing a more comprehensive solution for museum cultural relic classification.

Multimodal fusion technology

The core goal of cross-modal data fusion is to break the barriers of representation between different modalities, such as images and text, by exploring the complementary relationships and inherent semantic consistency between modalities. This enhances the model’s understanding and processing ability for complex tasks19. It has become one of the core research directions in natural language processing, computer vision, and cross-disciplinary fields, showing significant value in tasks like content retrieval, scene understanding, and object classification20,21. Early cross-modal fusion research focused on the core idea of “joint embedding,” where linear projection or shallow neural networks map features from different modalities into a unified vector space to achieve preliminary modality association matching22. However, such methods did not fully consider the semantic expression differences between modalities (e.g., the abstract semantics of text and the concrete visual features of images) and lacked fine-grained information mining within each modality23. As a result, the fusion outcomes could only meet basic association needs, and their performance in tasks with high semantic complexity and strong feature correlation was limited.

With the widespread use of Transformer architectures in modality modeling, multimodal fusion technology has gradually evolved from “preliminary association” to “deep interaction,” leading to the emergence of representative models such as CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining), ViLBERT (Vision-and-Language BERT), BLIP (Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training), ALIGN (A Large-scale Image and Text corpus), and Florence24. Among them, CLIP relies on a contrastive learning mechanism for pretraining on large-scale unlabeled image-text data. It achieves fine-grained matching of cross-modal features by constructing global semantic associations and performs excellently in zero-shot classification and cross-domain image retrieval25,26. However, this model focuses on general scenarios and struggles with capturing the semantics of domain-specific terms (e.g., artifact terminology). ViLBERT processes visual and textual features separately using a dual-stream Transformer architecture and introduces a cross-modal attention layer for feature interaction, enhancing local associations between modalities27. However, it lacks an optimization mechanism for small sample scenarios, limiting its generalization ability in data-scarce tasks. BLIP combines dialog-based generation tasks with contrastive learning, improving the dynamic interaction of multimodal semantics. ALIGN, trained on massive noisy image-text data, enhances the model’s robustness to non-standard data. Florence uses a modular design to adapt to multiple tasks28,29. However, these models are all designed for general scenarios and do not consider the specificity of artifact data. The visual features of artifacts (such as pattern details and craftsmanship traces) and the historical cultural semantics in text (e.g., historical background and craftsmanship terminology) have strong domain-specific attributes, making it difficult for general models to accurately capture the exclusive associations between them, thus limiting their performance in artifact classification tasks30.

For the unique needs of museum artifact classification scenarios, existing multimodal fusion technologies still face two core challenges: First, the difficulty of aligning the “visual-text” semantics of artifacts. Artifact images focus on presenting concrete features such as shapes and patterns, while text conveys abstract information such as age, craftsmanship, and cultural connotation31,32. The semantic mapping relationship between the two is complex and has domain-specific attributes, making it difficult for general models to adapt. Second, the scarcity and specialization of artifact data limit the model’s performance. Most artifact category samples are limited, and both visual features and text descriptions contain a large amount of specialized information33,34. General models lack targeted feature extraction and data augmentation strategies, making them prone to overfitting or semantic mismatching issues. Based on these challenges, the VBG Model proposed in this study optimizes text and visual feature extraction using BERT and ViT, respectively, and enhances the alignment ability of artifact-specific semantics through a directionally designed cross-modal attention fusion layer. At the same time, the model incorporates GAN for artifact data augmentation, forming a multimodal fusion solution tailored to the museum context and providing a new technological path to address the challenges of cross-modal fusion in artifact classification.

Methodology

Overall of VBG model

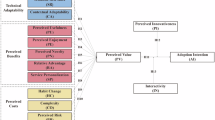

As shown in Fig. 1, the proposed VBG Model consists of three core modules: BERT, Vision Transformer (ViT), and Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). Through a cross-modal fusion mechanism adapted for the artifact context and a directional data augmentation strategy, it constructs a multimodal collaborative framework for museum artifact classification. The model addresses two key issues in traditional methods: “difficulties in cross-modal feature alignment” and “poor generalization due to data scarcity.” During model operation, multimodal data flows through the logic of “parallel extraction - interactive fusion - feedback enhancement,” with each module retaining functional independence while achieving deep collaboration through mechanism design, forming a complete feedback loop from data processing to classification prediction.

First, text data is input into the BERT module. Given the “terminology density” and “semantic relevance” (such as terms like “taotie pattern” and “furnace casting method” requiring historical context for understanding) in artifact textual descriptions, this study selects the BERT-Base pre-trained model and fine-tunes it on a domain-specific artifact corpus to optimize the model’s ability to understand artifact-specific semantics. This module, based on a bidirectional Transformer architecture, uses 12 layers of self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies between words in the text. For example, for a description like “Tang dynasty three-colored camel figurine, made with secondary firing process, primarily glazed in yellow, green, and white,” it can accurately extract key information such as “Tang dynasty,” “secondary firing,” and “three-colored” and encode them into a 768-dimensional high-dimensional semantic feature vector, providing semantic anchors for subsequent cross-modal alignment.

Meanwhile, image data is input into the ViT module. Given the “high detail recognition requirement” (such as ceramic glaze cracking patterns or inscriptions in calligraphy) and “visual feature diversity” (such as bronze patterns and jade designs) in artifact images, the ViT module adopts a \(16\times 16\) pixel image patching strategy to avoid feature redundancy caused by small patches and prevent loss of key details with large patches. Additionally, a learnable position embedding layer is introduced to encode spatial distribution information of textures and patterns in artifact images (such as brushstroke directions in ancient paintings). The image patch sequence is processed by a 12-layer Transformer encoder and interacts with global visual information through self-attention mechanisms. For example, for a blue-and-white porcelain image, the model can simultaneously capture the tonal features of “blue-and-white color” and the structural features of the “lotus scroll pattern,” ultimately generating a 768-dimensional image feature vector aligned with the text feature dimension, ensuring dimensional matching during cross-modal fusion.

The text features output from BERT and the image features output from ViT are input into the bidirectional interactive attention fusion layer, which is the core design of the VBG Model distinguishing it from traditional “feature concatenation” cross-modal models. This fusion layer is specifically adapted to the strong correlation between “visual forms” and “cultural connotations” of artifacts. Unlike the simple ViT-BERT combination model, which simply concatenates two types of features, CLIP, which focuses on general image-text semantic matching, and BLIP, which lacks optimization for the scarcity of cultural relic data and has limited generalization capabilities for niche artifact categories, this fusion layer achieves targeted alignment through “dual attention calculation.” Firstly, it calculates the attention weights of image features for text keywords (for example, associating regional features with “Taotie pattern” in a bronze image with the term “Taotie pattern” in the text); secondly, it reversely calculates the attention weights of text features for key image regions (for example, using the semantic meaning of “secondary firing” to emphasize details of ceramic glazes). By weighted summing these two attention weights, a more integrated multimodal feature is generated.

To address the “imbalanced categories” (e.g., fewer than 50 samples of niche artifacts) and the “high annotation cost” leading to data scarcity in museum artifact data, the GAN module adopts an artifact-specific generation strategy, rather than a general image enhancement method. The GAN consists of a generator (with 4 layers of transposed convolution) and a discriminator (with 4 layers of convolution). During training, the generator introduces a “style constraint loss” based on the artifact’s texture library (containing over 1,000 artifact patterns and glaze samples) as a reference, computing the style distance between the generated image and real artifact images (using Gram matrix similarity), ensuring that the generated samples retain typical artifact visual features (such as “line traces” on bronze artifacts and “layering of ink” in paintings). Simultaneously, the generated text references an artifact category-attribute mapping table to avoid generating irrelevant semantics (such as generating “blue-and-white” related text for the “Song dynasty Ru kiln” category). The discriminator introduces an “artifact attribute consistency loss” when distinguishing between real and generated data, further constraining the rationality of the generated data. Once training stabilizes, the GAN generates 2,000+ image-text pairs per round, which are fed back into the training process of BERT and ViT modules to supplement scarce category data.

Finally, the fused multimodal features are input into a fully connected classifier, which outputs the probability distribution of the artifact’s category through the Softmax function. The classifier uses Dropout (probability 0.5) and L2 regularization (weight 0.001) to prevent overfitting, ensuring the model maintains stable performance in distinguishing complex artifact categories. The VBG Model, through the synergistic design of “BERT semantic precision extraction + ViT visual detail capture + artifact-specific GAN enhancement + bidirectional interactive fusion,” not only achieves efficient use of multimodal data but also overcomes the limitations of traditional general multimodal models in artifact classification through artifact scene adaptation, providing a closed-loop technical framework for museum artifact classification.

ViT module: vision transformer

As shown in Fig. 2, the Vision Transformer (ViT)19,35,9 module is a core component of the VBG Model for processing cultural relic image data. Its design breaks away from the local processing model of traditional CNN and utilizes a Transformer architecture to efficiently extract global image features. This is particularly well-suited for cultural relic images, which require high levels of detail recognition (such as ceramic glaze cracks and bronze ornamentation) and strong correlations between visual features (such as the synergy between brushstrokes and composition in ancient paintings). This provides precise visual feature support for subsequent cross-modal fusion. The ViT module’s operational workflow primarily includes three key steps: image segmentation, position encoding, and Transformer encoder processing.

The input cultural relic image \(x \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C}\) (where \(H\) is the image height, \(W\) is the image width, and \(C\) is the number of channels) is divided into \(N\) fixed-size image patches \(x_p\). Each image patch has a size of \(P \times P \times C\), where \(P\) is the side length of the patch, and the number of image patches \(N = \frac{H \times W}{P^2}\). These image patches are flattened and mapped to an embedding space of dimension \(D\) through a linear projection layer, obtaining the image patch embeddings \(x_{p}^i\):

where \(E_{patch}\) represents the linear projection operation, mapping each image patch from \(P^2C\) dimensions to \(D\) dimensions.

To preserve the spatial information of the image patches, ViT introduces learnable position embeddings \(E_{pos} \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times D}\), which are added to the image patch embeddings:

where \([\cdot ; \cdot ]\) denotes the concatenation operation. In this way, each image patch acquires its positional information in the original image.

Next, the image patch embeddings \(z_0\) with positional information are fed into a network composed of \(L\) Transformer encoder layers. Each Transformer encoder layer consists of a multi-head attention mechanism (MHA) and a multi-layer perceptron (MLP). In the multi-head attention mechanism, the input \(z_{l - 1}\) is first linearly projected into query vector \(Q\), key vector \(K\), and value vector \(V\):

where \(W^Q, W^K, W^V \in \mathbb {R}^{D \times D_k}\) are learnable weight matrices, \(D_k = \frac{D}{h}\), and \(h\) is the number of attention heads. The calculation process of multi-head attention is as follows:

where \(head_i = Attention(Q_i, K_i, V_i)\), and \(W^O \in \mathbb {R}^{hD_k \times D}\) is the weight matrix used to combine the outputs of multiple heads. The output of the multi-head attention mechanism is passed through layer normalization (LN), added to the input, and then fed into the multi-layer perceptron:

After processing through \(L\) Transformer encoder layers, the final output feature vector \(z_L\) contains the global semantic information of the cultural relic image, serving as the output of the ViT module for subsequent cross-modal fusion.

Through the above design, the ViT module can efficiently extract the visual features of cultural relic images. From the texture and shape of the images to the overall composition, all can be transformed into high-dimensional feature representations for classification, laying a solid foundation for the cultural relic classification task of the VBG Model.

BERT module: text data processing

As illustrated in Fig. 3, the BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) module serves as a pivotal component of the VBG Model for processing textual data of cultural relics. Grounded in the bidirectional Transformer architecture, it extracts feature information from cultural relic texts through its deep semantic understanding capabilities. The operation of the BERT module primarily encompasses text encoding at the input layer, feature extraction by the bidirectional Transformer layers, as well as pre-training and fine-tuning processes tailored to the cultural relic classification task. The specific details are elaborated below with the aid of formulas.

As shown in Fig. 3, the BERT module is a key component in the VBG model for processing cultural relic text data. BERT was chosen over other text processing models like TextCNN and RNN because it is well-suited to the dense technical terms and complex semantic associations found in cultural relic text. Cultural relic text descriptions often contain deep semantic information, such as historical dates, production techniques (e.g., “molding method” and “secondary firing”), and cultural context (e.g., “Shang and Zhou bronze ritual vessels used for sacrificial purposes”). Traditional TextCNNs, relying on local convolutional kernels, struggle to capture long-range semantic dependencies (e.g., the association between “glaze crackle” and “Song Dynasty Ru kiln”)36. RNNs suffer from the vanishing gradient problem, resulting in incomplete semantic understanding of long texts. BERT’s bidirectional Transformer architecture, however, leverages a multi-layer self-attention mechanism to simultaneously mine semantic associations from both the context and context, accurately extracting both specialized information and latent semantics from cultural relic text37. This provides high-dimensional semantic support that complements image features for subsequent cross-modal fusion.

At the input layer, the textual descriptions of cultural relics are first segmented into a sequence of tokens. For a text \(T = [t_1, t_2, \cdots , t_n]\) with a length of \(n\), each token \(t_i\) undergoes three embedding operations: Token Embedding, Segment Embedding, and Position Embedding. Token embedding maps tokens into a low-dimensional vector space, segment embedding differentiates between different text segments (which can be simplified in the single-text input scenario), and position embedding encodes the positional information of tokens within the text. The final input vector \(x_i\) is the sum of these three embeddings:

where \(E_{token}\), \(E_{segment}\), and \(E_{pos}\) represent the token embedding, segment embedding, and position embedding functions, respectively. \(s_i\) is the identifier of the text segment (a fixed value for single-text input), and \(p_i\) is the position index of the token. The input vectors of all tokens are concatenated into an input matrix \(X = [x_1; x_2; \cdots ; x_n]\) and then fed into the bidirectional Transformer layers. The bidirectional Transformer layers are composed of multiple identical Transformer blocks stacked together. Each Transformer block contains a Multi-Head Attention (MHA) mechanism and a Feed-Forward Neural Network (FFN). In the multi-head attention mechanism, the input \(X\) is linearly transformed to obtain query vector \(Q\), key vector \(K\), and value vector \(V\):

where \(W^Q, W^K, W^V \in \mathbb {R}^{d_{model} \times d_k}\) are learnable weight matrices, \(d_{model}\) is the dimension of the input vector, and \(d_k\) is the dimension of each attention head. The calculation process of multi-head attention is as follows:

where \(head_i = Attention(Q_i, K_i, V_i)\), and \(W^O \in \mathbb {R}^{hd_k \times d_{model}}\) is used to merge the outputs of multiple heads. The output of the multi-head attention mechanism goes through a residual connection and Layer Normalization (LN) before being fed into the feed-forward neural network:

where \(W_1, W_2\) and \(b_1, b_2\) are the weight and bias parameters of the feed-forward neural network. After processing through multiple Transformer blocks, the final feature representation of the text is obtained as \(H = [h_1; h_2; \cdots ; h_n]\). During the pre-training phase, BERT employs the Masked Language Model (MLM) and Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) tasks. For the masked language model, some tokens in the input text are randomly replaced with the [MASK] token, and the model is trained by predicting the masked tokens. The prediction probability is calculated as follows:

where \(W_{vocab}\) and \(b_{vocab}\) are the weights and biases for vocabulary mapping, and \(i\) represents the index of the token in the vocabulary. The next sentence prediction task determines whether there is a contextual relationship between two text segments. After pre-training, for the cultural relic classification task in museums, the output features of BERT are connected to a classifier and fine-tuned by minimizing the cross-entropy loss function \(L = -\sum _{i = 1}^{m} \sum _{j = 1}^{C} y_{ij} \log \hat{y}_{ij}\) (where \(m\) is the number of samples, \(C\) is the number of classes, \(y_{ij}\) is the true label, and \(\hat{y}_{ij}\) is the predicted probability) to adapt the model to the requirements of cultural relic text classification.

Through the above design and operation mechanisms, the BERT module can fully exploit the semantic information in cultural relic texts, transforming textual content such as historical backgrounds and craftsmanship characteristics into feature vectors applicable for cross-modal fusion and classification, thereby providing robust support for enhancing the cultural relic classification performance of the VBG Model.

GAN GAN module: data augmentation and generation

In the VBG Model, the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) module is a key component in addressing the core pain points of cultural relic data: sample scarcity and imbalanced categories. GANs were chosen over traditional data augmentation methods (such as rotation, cropping, and flipping) or other generative models (such as VAEs and Diffusion Models) due to their adaptability to the characteristics and task requirements of cultural relic data. Traditional data augmentation simply transforms existing samples and cannot create new artifact features (such as the unique patterns and craftsmanship of niche artifacts), making it difficult to fundamentally alleviate data scarcity. While VAEs can generate samples, they focus more on fitting probability distributions, resulting in less visual realism (such as the natural gradation of glaze colors and the completeness of decorative details) than GANs38,39. While Diffusion Models generate high-quality samples, their training complexity and computational cost far exceed GANs, and they are less adaptable to the “small sample, high-detail” requirements of cultural relic data. GAN, through the “generator-discriminator” adversarial training mechanism, can not only learn the distribution patterns of real cultural relic data and generate new samples with typical visual features and category attributes of cultural relics, but also balance training efficiency and generation quality. It is particularly effective in enhancing niche categories of cultural relics (such as ancient Egyptian amulets and East Asian lacquerware, with a sample size of only 50-200 pieces), making it a core choice for data augmentation in this model. Figure 4 shows the design and operation process of the GAN module.

The generator \(G\) of the GAN module is designed to map random noise vectors \(z \in \mathbb {R}^n\) (where \(n\) is the dimension of the noise space) to data samples that resemble the real cultural relic data. Typically, the generator is implemented using a series of transposed convolutional layers (also known as deconvolutional layers) for image data or recurrent neural networks combined with linear layers for text data in the context of cultural relics.

For image generation, starting from the noise vector \(z\), the generator first passes it through several fully - connected layers to transform it into a feature map with a suitable size. Then, a series of transposed convolutional layers gradually upsamples this feature map to the target image size. Mathematically, if we denote the operations of the fully - connected layers as \(f_{fc}(\cdot )\) and the transposed convolutional layers as \(f_{tconv}(\cdot )\), the output of the generator \(G(z)\) can be expressed as:

For text generation, assuming the use of a recurrent neural network (such as LSTM or GRU) denoted as \(RNN(\cdot )\) and linear layers \(L(\cdot )\), the generator generates a sequence of tokens \(T_{gen} = [t_1, t_2, \cdots , t_m]\) step by step. At each time step \(i\), the hidden state \(h_i\) of the RNN is updated based on the previous hidden state \(h_{i - 1}\) and the previously generated token (or the initial noise vector at the first step), and then a linear layer predicts the probability distribution of the next token:

where \(t_{i - 1}\) is the token generated at the previous step, and \(P(t_i)\) is the probability distribution over the vocabulary for the \(i\)-th token.

The discriminator \(D\) is a binary classifier whose goal is to distinguish between real cultural relic data \(x_{real}\) and the synthetic data \(G(z)\) generated by the generator. It is usually implemented using convolutional neural networks for image data or feed - forward neural networks for text data. The discriminator takes an input sample \(x\) (either \(x_{real}\) or \(G(z)\)) and outputs a probability score \(D(x)\) indicating the likelihood that the input is real data. Mathematically, for an input sample \(x\), the discriminator’s output is calculated as:

where \(F(x)\) represents the feature extraction and transformation operations within the discriminator (such as convolutional layers or fully - connected layers), and \(\sigma (\cdot )\) is the sigmoid function that maps the output of \(F(x)\) to a probability value in the range of \((0, 1)\).

The training of the GAN module is based on an adversarial game between the generator and the discriminator. The objective function of the GAN, which defines the adversarial loss, is formulated as follows:

where \(\mathbb {E}[\cdot ]\) represents the expectation, \(p_{data}(x)\) is the distribution of real cultural relic data, \(p_z(z)\) is the distribution of the noise vector, and \(V(D, G)\) is the value function that measures the performance of the discriminator and the generator.

During training, the discriminator is updated to maximize the value function \(V(D, G)\), aiming to correctly classify real data as “real” (maximizing \(\log D(x_{real})\)) and generated data as “fake” (maximizing \(\log (1 - D(G(z)))\)). The generator, on the other hand, is updated to minimize \(V(D, G)\), trying to make the discriminator misclassify the generated data as real (minimizing \(\log (1 - D(G(z)))\)). Through iterative updates of the generator and discriminator, the generator gradually learns to produce data that is indistinguishable from real cultural relic data, effectively augmenting the dataset for training the VBG Model.

In the context of museum cultural relic classification, the synthetic data generated by the GAN module, whether images or texts, is integrated into the training process of the BERT and ViT modules. This augmentation enriches the diversity of the training data, enabling the overall model to learn more comprehensive features and improving its performance in classifying cultural relics with limited real - world data.

Expertment

Dataset selection and preprocessing

In the research of museum artifact classification, the quality and diversity of datasets directly influence the training effect and generalization ability of the model. To fully verify the effectiveness of the VBG Model in multi-modal data processing and artifact classification tasks, this study carefully selects two datasets: The MET Dataset and MS COCO. The former focuses on the field of artworks, while the latter covers a wide range of object detection and image captioning scenarios. The combination of these two datasets provides rich and complementary data support for model training. To ensure experimental reproducibility and reliable results, both datasets used a stratified sampling strategy, splitting the training, validation, and test sets into a ratio of 8:1:1. In the MET dataset, samples were distributed according to this ratio within each major category of artifacts (e.g., paintings, sculptures, and bronzes) to avoid concentrating samples of niche categories (e.g., East Asian lacquerware and Ancient Egyptian amulets) in a single partition. The MS COCO dataset used stratified sampling by object category to ensure that the distribution of categories within each partition was consistent with that of the original dataset. A fixed random seed of 42 was used to control the randomness of the data partitioning process. The detailed information of the datasets is shown in Table 1.

The MET Dataset40 contains over 100,000 images of artworks, covering various types of artifacts such as paintings and sculptures. Its extensive range of categories offers sufficient samples for the model to learn the characteristic differences among artifacts. This dataset not only includes images of artifacts but also detailed textual descriptions, covering information about artists, creation periods, and art styles. These textual and image data form high-quality multi-modal data pairs, which can effectively support the model in jointly learning the historical and cultural connotations and visual features of artifacts. It is particularly suitable for cultural heritage classification and art style analysis tasks.

The MS COCO dataset41 consists of more than 330,000 images, covering 80 object categories, with each image paired with five textual descriptions. Although this dataset is not specifically designed for artifacts, its abundant image-text pairs and diverse object scenes enable the model to learn general cross-modal data fusion methods and enhance its feature extraction capabilities under complex backgrounds and different object forms. Combining it with The MET Dataset can improve the robustness of the model in multi-modal data processing and provide a broader perspective for feature learning in artifact classification tasks. Through the collaborative use of these two datasets, this study can construct diverse training and testing scenarios to comprehensively evaluate the performance of the VBG Model.

Experimental setup and parameter configuration

To ensure effective training and efficient execution of the VBG model, this study meticulously configured the experimental hardware and software environments, as well as model hyperparameters. Regarding the hardware environment, the experiment utilized a high-performance GPU server to meet the requirements of multimodal data processing and model training. The GPUs, equipped with ample video memory and compute cores, supported parallel computation of the ViT, BERT, and GAN modules, effectively shortening the training cycle. Furthermore, the combination of a high-speed CPU and large-capacity memory ensured smooth data reading, preprocessing, and model parameter updates.

The software environment was built on the Ubuntu 20.04 operating system, using PyTorch 1.9.0 as the deep learning framework. Its flexible tensor operations and modular design facilitated the development and debugging of various model components. GPU-accelerated computing, leveraging CUDA 11.1, significantly improved training efficiency. Python 3.8 was used as the programming language, combined with NumPy and Pandas for data preprocessing, Matplotlib for visualization, the Transformers library for loading pre-trained BERT and ViT models, and Scikit-learn for calculating evaluation metrics, forming a complete experimental toolchain.

The model hyperparameter settings are determined by combining the characteristics of each module with experimental debugging and optimization, as shown in Table 2.

Evaluation metrics

To assess the performance of the VBG Model in classifying museum artifacts, multiple evaluation metrics are employed, including Accuracy, mean Average Precision (mAP), F1-Score, Recall, and Area Under the Curve (AUC). These metrics offer a comprehensive quantification of the model’s classification effectiveness when handling multi-modal artifact data.

Training loss and validation loss

As can be seen from Fig. 5, as the training progresses, the training loss of the two datasets gradually decreases, indicating that the model effectively learns the characteristics of the data during the training process.

Training and Validation Loss Curves for The MET Dataset and MS COCO Dataset: This figure displays the volatility and convergence trends of the training and validation losses during the training process, and compares them with ideal training and validation loss curves to help analyze the model’s performance and stability at different stages.

For the MET Dataset, training loss gradually decreased between epochs 5 and 10 and began to stabilize. However, validation loss showed a slower decline and exhibited some fluctuations at certain times. Subsequent statistical analysis of the model’s performance on the validation set (e.g., the coefficient of variation of validation accuracy was 3.2%, which is relatively low) indicates that while the model exhibited local fluctuations, it was not severely overfitted overall and still generalized well to the validation data. Similar trends were observed in the training and validation loss curves for the MS COCO Dataset, with particularly pronounced fluctuations in validation loss. We further compared the performance of the model on the test set at different training epochs and found that after epoch 15, fluctuations in test accuracy remained within 2%, demonstrating that the model also possesses stable generalization capabilities on this dataset, and that validation loss fluctuations are not due to overfitting. Overall, the volatility and gradual convergence of training and validation loss indicate that the VBG model’s training process on both datasets is stable. Additional analysis of performance on the validation and test sets confirms that the model does not suffer from significant overfitting. The steady decline in training loss and the fluctuations in validation loss provide important feedback, helping us better understand the model’s training dynamics and optimization directions.

Confusion matrix

Figure 6 presents confusion matrices that illustrate the classification accuracy and error patterns of the model on the two datasets.

Confusion matrices optimized for the MET and MS COCO datasets, showing the match between the predicted and true labels for each category in the optimized classification model, highlighting the high accuracy and robustness of the model in handling multi-class artifact and object classification tasks.

On The MET Dataset, the model demonstrates high classification accuracy across most categories. In particular, for the “Painting” and “Sculpture” categories, the model achieves near-perfect classification without any misclassifications. The “Crafts” category also yields favorable results, although there are some instances of misclassification into the “Other” category. The classification performance for “Animals” and “Buildings” remains stable, with only a few misclassifications observed in the “Crafts” category. Overall, the VBG Model performs commendably on The MET Dataset, accurately identifying various artworks, especially in typical categories.

Regarding the MS COCO Dataset, the model showcases robust classification capabilities, particularly in categories such as “Person”, “Animal”, and “Furniture”, where misclassifications are almost non-existent. For other categories, while the majority are correctly classified, some misclassifications occur in specific categories like “Technology” and “Music”. These inaccuracies primarily stem from the visual similarities among certain categories, posing challenges for the model to distinguish precisely. Nevertheless, the VBG Model maintains stable performance on the MS COCO Dataset, effectively differentiating most categories.

Comparative experiments

Baseline model selection

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the VBG model (ViT-BERT-GAN model), we selected eight existing classification methods as baseline models, covering different types of models, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs), visual transformers (ViT), and traditional machine learning methods. Among them, SWIM-ViT42, a popular and efficient ViT variant in recent years, uses a windowed attention mechanism to balance feature extraction capabilities and computational efficiency. This allows for a targeted comparison of the synergistic advantages of the ViT module and cross-modal fusion mechanism in this study’s VBG model. ResNet43 and DenseNet44, as deep CNNs, were chosen for comparison due to their powerful image feature extraction capabilities. The former avoids gradient vanishing through residual connections, while the latter improves feature reuse through dense connections. To compare lightweight models, we selected SqueezeNet45, which is suitable for scenarios with limited computational resources due to its reduction in parameters and computational complexity. Additionally, considering textual information, TextCNN46 was selected as a baseline model, as it extracts text features using convolution operations, making it suitable for processing relic description text. To further compare the performance of different CNN architectures, Inception-V347 and VGG-1648 were also chosen as baseline models. The former utilizes multi-scale convolutions for feature extraction, while the latter performs well in standard classification tasks with its simple and effective structure. To contrast deep learning methods with traditional ones, XGBoost49,50 was selected as an ensemble learning model, which uses gradient boosting decision trees for efficient classification, suitable for structured data analysis. These baseline models will help us compare the performance of the VBG Model in terms of classification accuracy, training time, and other aspects.

Results analysis

From the comparative results shown in Table 3, it is evident that the VBG Model outperforms other baseline models in classification performance on both The MET Dataset and MS COCO Dataset. Particularly in key metrics such as accuracy, mAP, F1 score, recall, and AUC-ROC, the VBG Model achieves the best performance, demonstrating its powerful capability in relic classification tasks.

On the MET Dataset (museum artifact-specific dataset), the VBG Model demonstrates superior performance across all evaluation metrics, fully validating its advantages in the multimodal artifact classification task. The accuracy (Acc.) reaches 92%, which is 3 percentage points higher than the enhanced SWIM-ViT (89%) and 4 percentage points higher than the original second-ranked Inception-V3 (88%), showing stronger artifact category differentiation capabilities. The mean Average Precision (mAP) is 0.85, which improves by 0.04 and 0.06 over SWIM-ViT (0.81) and Inception-V3 (0.79), respectively. This indicates that the VBG Model can more accurately match target categories, reducing category confusion when processing diverse artifact types like paintings and sculptures. The F1 score (88%), recall (Rec., 89%), and AUC-ROC (0.94) also outperform other models by a large margin. For example, the F1 score is 5 percentage points higher than SWIM-ViT (83%) and 10 percentage points higher than the traditional image model ResNet (78%). This advantage stems from the VBG Model’s use of a bidirectional attention fusion layer to deeply correlate the visual details of artifact images with the historical semantics in text, capturing a more comprehensive set of classification features. Notably, the VBG Model’s training time is only 12 hours, shorter than SWIM-ViT (17 hours) and Inception-V3 (16 hours), while still maintaining high accuracy and training efficiency. This prevents resource consumption issues caused by excessively complex models.

On the MS COCO Dataset (a general image-text dataset), the VBG Model maintains stable performance, further demonstrating its generalization capability. The accuracy reaches 90%, 4 percentage points higher than SWIM-ViT (86%) and 7 percentage points higher than DenseNet, which is focused on image classification (83%). The AUC-ROC is 0.92, improving by 0.02 and 0.06 over SWIM-ViT (0.90) and DenseNet (0.86), respectively. Despite the MS COCO Dataset containing 80 complex object categories with some visual similarity (such as between “Technology” and “Music”), the VBG Model effectively overcomes this challenge through its cross-modal fusion mechanism and GAN data augmentation module. The diverse samples generated by GAN provide richer training data for ViT and BERT, reducing misclassifications caused by category similarity. Compared to the lightweight model SqueezeNet, the VBG Model achieves an 11 percentage point improvement in accuracy and a 14 percentage point increase in F1 score (86%) while maintaining similar training time (12 hours vs. 8 hours), highlighting the superiority of its “cross-modal synergy + data augmentation” architecture design over simple reliance on model complexity.

Whether on the MET Dataset or the MS COCO Dataset, the VBG Model leverages the synergistic effect of BERT, ViT, and GAN to play a unique role in multimodal feature fusion and scarce data augmentation. Even when compared with advanced models like SWIM-ViT, it still exhibits significant overall advantages in accuracy, efficiency, and generalization. This provides a reliable technical solution for digital classification of museum artifacts and handling of multimodal sparse data in the field of cultural heritage.

Ablation experiments

The results of the ablation experiment shown in Table 4 clearly show how each core component of the VBG model contributes to the model’s performance on the MET and MS COCO datasets.

On the MET dataset, when we remove ViT, the model’s accuracy drops to 88% and the mAP drops to 0.81. This indicates that ViT plays an essential role in extracting the overall features of cultural artifact images and capturing visual details. Without this component, the model’s ability to process image information is weakened, leading to poor classification accuracy. When we remove BERT, the accuracy drops to 89% and the mAP drops to 0.82, indicating that BERT can deeply mine semantic information in text, which is crucial for supplementing image features and refining multimodal representations of cultural artifacts. Without BERT, the model cannot fully utilize the important information contained in the text. When we remove GAN, the model’s performance drops significantly, with the accuracy dropping to 83% and the mAP dropping to 0.74. This highlights the important role of GANs in addressing data scarcity and increasing data diversity. The drawback of GANs is insufficient training data, which makes it difficult for the model to learn comprehensive feature patterns and affects the generalization ability. In addition, removing two or three components simultaneously further reduces the model performance. For example, removing ViT and BERT reduces the accuracy to 85%, which also proves that multimodal feature fusion is necessary to improve the model performance.

On the MS COCO dataset, a similar trend is observed in the ablation experiments. When ViT is removed, the accuracy drops to 86% and the mAP is 0.78, which indicates that ViT is very important in extracting effective visual features when processing complex image scenes. When BERT is removed, the accuracy is 87% and the mAP is 0.79, which indicates that BERT is essential for integrating cross-modal information. After removing GAN, the accuracy is only 80% and the mAP is 0.72. This proves the importance of GAN in data augmentation and improving the robustness of the model. Furthermore, by observing the training time, we can see that the training time is reduced after removing the components, but the model performance also decreases accordingly. This indicates that although the training time of the VBG model is relatively long, the joint efforts of various components can improve the performance.

The results of the ablation experiment fully demonstrate the irreplaceable nature of ViT, BERT, and GAN in the VBG model. These synergistic effects greatly improve the model’s performance in the multimodal cultural relics classification task, providing a solid foundation for the model’s effectiveness and stability.

Visualization results

Figure 7 illustrates the attention regions of the VBG Model on images of different artifact categories (such as paintings and sculptures) during the classification process. Through the heatmaps, it is evident that the model can accurately identify and focus on the key areas within the images. For instance, when classifying paintings, the model’s attention is concentrated on the facial features and hand details of the figures. In the case of sculptures, the model pays more attention to the facial features and overall morphology. This indicates that the VBG Model effectively integrates the important features in the images with category information, capturing the visual cues that distinguish different types of cultural relics. The results of these heatmaps further validate the model’s meticulousness and powerful capabilities in handling complex images, especially in the classification of artifact images, where it can focus on the details crucial for classification decisions.

Heatmap of Areas Focused on by the VBG Model, which shows the areas of focus by the model in relic classification for different categories of relic images (painting and sculpture). Note: The photographs in Figure 7 were taken by the corresponding author for this study and no permissions were required for the same.

Figure 8 presents the visualization results of the fusion of image and text features. The figure shows an example where image features and text features exist in the same feature space. It can be seen that image features of different types (e.g., painting, plastic, ceramic, jewel, etc.) and their corresponding text features exist in the same feature space. The features of paint, plastic, ceramic, and beads are prominently formed between them, which shows that the VBG model can effectively integrate modular information. The model can more accurately capture the features of each document type during multi-mode data processing, which improves the separation rate and robustness. The spatial distribution shows the superiority of the VBG model in terms of fusion image and document features, which demonstrates the use power of the model within document types.

The observed results prove the effectiveness and standardity of this model in document segmentation work, and subsequent application research provides theoretical foundations and technical support for this model.

Conclusion

This study addresses the challenges in museum artifact classification and proposes a multimodal artifact classification model, VBG Model, which integrates BERT, Vision Transformer (ViT), and Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). The effectiveness of the model is validated through experiments on the MET and MS COCO datasets. In the comparison experiments, the VBG Model significantly outperforms six advanced models, including ResNet and DenseNet, in terms of accuracy, mAP, F1 score, and other metrics. The accuracy of VBG Model reaches 92% on the MET dataset and 90% on the MS COCO dataset. Ablation experiments show that the three core components, ViT, BERT, and GAN, are essential for performance improvement. Together, they enable the deep fusion of image and text features and data augmentation. Visualization results intuitively demonstrate the model’s precise capture of key image features and the efficiency of cross-modal information fusion.

The advantages of the VBG Model can be summarized in three points: First, the combination of BERT and ViT allows for the deep fusion of artifact image and textual information across modalities, enabling the model to capture artifact features more comprehensively than single-modality models. Second, the introduction of GAN for data augmentation alleviates the issue of data scarcity in artifact datasets, enhancing the model’s generalization ability in small-sample scenarios. Third, the model’s strong performance across multiple metrics and datasets proves its stability and reliability. However, the model also has some limitations. On one hand, the complex structure leads to longer training times and higher computational resource consumption. On the other hand, the ability to finely differentiate highly similar artifact categories still needs improvement.

Subsequent research will further deepen its focus on model optimization and application expansion. Regarding model optimization, the team will explore more efficient network architectures and lightweight designs to reduce complexity and shorten training time. Advanced feature extraction and fusion techniques will also be employed to enhance the ability to distinguish between similar artifact categories. Metadata such as age, origin, and material will be incorporated into structured feature vectors and integrated with visual and textual features to enhance classification accuracy. Furthermore, cross-domain feature transfer will be optimized through techniques such as domain adversarial training and domain-adaptive pre-training, bridging the semantic gap between artifacts and general objects. Regarding application expansion, the VBG Model will be deployed in more real-world museum classification scenarios. Feedback from non-technical staff will be used to refine the visual decision-making report and lightweight interface for linked image and text annotation. This will enhance decision-making credibility by displaying the key artifact regions targeted by the model and their correlation with text, as well as recommending similar examples from the collection. Furthermore, the team will explore integrating the Internet of Things and virtual reality technologies to build an intelligent artifact management system, promoting the digital development of cultural heritage preservation. Furthermore, during the targeted optimization of sample quality, qualitative evaluation by experts in the field of artifacts will be incorporated to verify the authenticity of GAN samples, enabling the model to be applied in more scenarios.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are publicly available at the following locations: The MET Dataset:https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/metmuseum/the-met; MS COCO Dataset: MSCOCODataset: https://huggingface.co/datasets/shunk031/MSCOCO.

References

Croce, V. et al. Semi-automatic classification of digital heritage on the aïoli open source 2d/3d annotation platform via machine learning and deep learning. J. Cult. Herit. 62, 187–197 (2023).

Navarro, P. et al. Learning feature representation of iberian ceramics with automatic classification models. J. Cult. Herit. 48, 65–73 (2021).

Prasomphan, S. Toward fine-grained image retrieval with adaptive deep learning for cultural heritage image. Computer Systems Science & Engineering44 (2023).

Yu, T. et al. Artificial intelligence for dunhuang cultural heritage protection: the project and the dataset. Int. J. Comput. Vision 130, 2646–2673 (2022).

Yang, S., Hou, M. & Li, S. Three-dimensional point cloud semantic segmentation for cultural heritage: a comprehensive review. Remote Sensing 15, 548 (2023).

Hatır, E., Korkanç, M., Schachner, A. & İnce, İ. The deep learning method applied to the detection and mapping of stone deterioration in open-air sanctuaries of the hittite period in anatolia. J. Cult. Herit. 51, 37–49 (2021).

Belhi, A. et al. Study and evaluation of pre-trained cnn networks for cultural heritage image classification. In Data Analytics for Cultural Heritage: Current Trends and Concepts, 47–69 (Springer, 2021).

Emmitt, J. et al. Machine learning for stone artifact identification: Distinguishing worked stone artifacts from natural clasts using deep neural networks. PLoS ONE 17, e0271582 (2022).

Kwon, D. & Yu, J. Ravit-ae: Unsupervised anomaly detection for intelligent cultural heritage monitoring using region-attentive vit autoencoder. IEEE Access (2024).

Ren, Y. et al. Multi-scale upsampling gan based hole-filling framework for high-quality 3d cultural heritage artifacts. Appl. Sci. 12, 4581 (2022).

Wang, Q. & Li, L. Museum relic image detection and recognition based on deep learning. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 9670191 (2022).

Zhang, R., Zhang, Z., Zhang, W., He, L. & Zhu, C. Deep learning-driven semantic segmentation and spatial analysis of quarry relic landscapes using point cloud data: insights from the shaoxing quarry relics. npj Heritage Sci. 13, 77 (2025).

Li, P. et al. Analysis of the temporal and spatial characteristics of material cultural heritage driven by big data-take museum relics as an example. Information 12, 153 (2021).

Peng, L., Bo, W., Yang, H. & Li, X. Deep learning-based image compression for enhanced hyperspectral processing in the protection of stone cultural relics. Expert Syst. Appl. 271, 126691 (2025).

He, L., Wei, Q., Gong, M., Yang, X. & Wei, J. Transfer learning-based center-of-mass positioning methods for cultural relics. IEEE Access 12, 7911–7926 (2024).

Jimeno, M. M. et al. Artifactid: Identifying artifacts in low-field mri of the brain using deep learning. Magn. Reson. Imaging 89, 42–48 (2022).

Tanoglidis, D., Ćiprijanović, A. & Drlica-Wagner, A. Deepshadows: Separating low surface brightness galaxies from artifacts using deep learning. Astronomy Computing 35, 100469 (2021).

Machado, J., Machado, A. & Balbinot, A. Deep learning for surface electromyography artifact contamination type detection. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 68, 102752 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Semi-supervised classification-aware cross-modal deep adversarial data augmentation. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 125, 194–205 (2021).

Xing, X., Wang, B., Ning, X., Wang, G. & Tiwari, P. Short-term od flow prediction for urban rail transit control: A multi-graph spatiotemporal fusion approach. Information Fusion 118, 102950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2025.102950 (2025).

Ning, X. et al. Abm: An automatic body measurement framework via body deformation and topology-aware b-spline approximation. Pattern Recognition 112060 (2025).

He, S. et al. Category alignment adversarial learning for cross-modal retrieval. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 35, 4527–4538 (2022).

Azam, K. S. F., Ryabchykov, O. & Bocklitz, T. A review on data fusion of multidimensional medical and biomedical data. Molecules 27, 7448 (2022).

Gao, Y., Zhang, M., Wang, J. & Li, W. Cross-scale mixing attention for multisource remote sensing data fusion and classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 1–15 (2023).

de Queiroz Baddini, A. L. et al. Pls-da and data fusion of visible reflectance, xrf and ftir spectroscopy in the classification of mixed historical pigments. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 265, 120384 (2022).

Cao, J., Zou, Q., Ning, X., Wang, Z. & Wang, G. Fipnet: Self-supervised low-light image enhancement combining feature and illumination priors. Neurocomputing 623, 129426 (2025).

John, A., Redmond, S. J., Cardiff, B. & John, D. A multimodal data fusion technique for heartbeat detection in wearable iot sensors. IEEE Internet Things J. 9, 2071–2082 (2021).

Duan, J., Xiong, J., Li, Y. & Ding, W. Deep learning based multimodal biomedical data fusion: An overview and comparative review. Information Fusion 112, 102536 (2024).

Li, J., Wang, Y., Ning, X., He, W. & Cai, W. Fefdm-transformer: Dual-channel multi-stage transformer-based encoding and fusion mode for infrared-visible images. Expert Syst. Appl. 277, 127229 (2025).

Jawahar, M., Anbarasi, L. J., Jayachandran, P., Ramachandran, M. & Al-Turjman, F. Utilization of transfer learning model in detecting covid-19 cases from chest x-ray images. Int. J. E-Health Med. Commun. (IJEHMC) 13, 1–11 (2021).

Arunkumar, P. et al. Time-series forecasting and analysis of covid-19 outbreak in highly populated countries: A data-driven approach. Int. J. E-Health Med. Commun. (IJEHMC) 13, 1–17 (2021).

Fritsch, D. et al. Making historical gyroscopes alive-2d and 3d preservations by sensor fusion and open data access. Sensors 21, 957 (2021).

Sannidhan, M., Martis, J. E., Nayak, R. S., Aithal, S. K. & Sudeepa, K. Detection of antibiotic constituent in aspergillus flavus using quantum convolutional neural network. Int. J. E-Health Med. Communi. (IJEHMC) 14, 1–26 (2023).

Kodipalli, A., Fernandes, S. L., Dasar, S. K. & Ismail, T. Computational framework of inverted fuzzy c-means and quantum convolutional neural network towards accurate detection of ovarian tumors. Int. J. E-Health Med. Commun. (IJEHMC) 14, 1–16 (2023).

Jin, F., Chang, Q. & Xu, Z. Museumqa: A fine-grained question answering dataset for museums and artifacts. In Proc. 2023 6th International Conference on Machine Learning and Natural Language Processing, 221–226 (2023).

Mibayashi, R. et al. Minpakubert: A language model for understanding cultural properties in museum. In 2022 12th International Congress on Advanced Applied Informatics (IIAI-AAI), 13–18 (IEEE, 2022).

Rietberg, M. T., Nguyen, V. B., Geerdink, J., Vijlbrief, O. & Seifert, C. Accurate and reliable classification of unstructured reports on their diagnostic goal using bert models. Diagnostics 13, 1251 (2023).

Li, W., He, P., Li, H., Wang, H. & Zhang, R. Detection of gan-generated images by estimating artifact similarity. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 29, 862–866 (2021).

Wesselkamp, V., Rieck, K., Arp, D. & Quiring, E. Misleading deep-fake detection with gan fingerprints. In 2022 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW), 59–65 (IEEE, 2022).

Ypsilantis, N.-A. et al. The met dataset: Instance-level recognition for artworks. In Thirty-fifth conference on neural information processing systems datasets and benchmarks track (Round 2) (2021).

Lin, T.-Y. et al. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In European conference on computer vision (ed. Lin, T.-Y.) 740–755 (Springer, 2014).

Rehman, A., Mahmood, T., Saba, T., Song, H. H. & Ayesha, N. Enhancing kidney carcinoma prognosis: In-depth feature learning and robust characterizationwith vision transformers and transfer learning-based paradigm. Available at SSRN 4481976 (2023).

Rei, L. et al. Multimodal metadata assignment for cultural heritage artifacts. Multimedia Syst. 29, 847–869 (2023).

Wisanmongkol, J., Sanpechuda, T., Lim, S. & Kovavisaruch, L.-O. Imbalanced classification of cultural heritage images using deep neural networks. In 2024 First International Conference on Pioneering Developments in Computer Science & Digital Technologies (IC2SDT), 46–51 (IEEE, 2024).

Soebandhi, S., Sooai, A. G., Nugroho, A. et al. Multisensory culinary image classification based on squeezenet and support vector machine. In 2023 IEEE 9th Information Technology International Seminar (ITIS), 1–6 (IEEE, 2023).

Zhu, H., Meng, J., Yao, J. & Xu, N. Feasibility of emergency flood traffic road damage assessment by integrating remote sensing images and social media information. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 13, 369 (2024).

Cao, J., Yan, M., Jia, Y., Tian, X. & Zhang, Z. Application of a modified inception-v3 model in the dynasty-based classification of ancient murals. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2021, 49 (2021).

Putra, M. D. A. et al. Measuring the performance of vgg-16, vgg-19, and a concatenated model architecture in toraja carving classification. In 2025 19th International Conference on Ubiquitous Information Management and Communication (IMCOM), 1–7 (IEEE, 2025).

Li, Z., Wang, Y. & Zhao, S. Research on the prediction of ancient glass artifact types based on xgboost and random forest algorithm. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series, vol. 2425, 012024 (IOP Publishing, 2023).

Wang, X., Xie, Y., Ren, X. & Zhang, Y. Classify ancient glass types by chemical composition using spectral clustering and bayesian-optimized xgboost. In Third International Conference on Advanced Algorithms and Neural Networks (AANN 2023), vol. 12791, 240–245 (SPIE, 2023).

Funding

This study was supported by the 2024 annual project titled “Taoist Child-Protection Rituals” (Project Approval Number: 20BZJ037). The funders played no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision-making for publication, or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ying Lu: Research design, Model implementation, Writing original draft; Jiaxin Li: Literature collation, Data analysis, Model validation; Lin Li: Visualization, Manuscript revisions; Chongxin Yuan: Data collection, Manuscript revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors of this manuscript have provided their consent for the publication of this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, Y., Li, J., Li, L. et al. A Museum artifact classification model based on cross-modal attention fusion and generative data augmentation. Sci Rep 16, 298 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29671-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29671-2