Abstract

To evaluate immune response and safety of a bivalent mRNA booster (ancestral/BA.4/5) vaccine in individuals who had received inactivated COVID-19 vaccine with different heterologous boost regimens. A prospective open-label study of bivalent ancestral/Omicron BA.4/5 was conducted. Healthy participants (age > 18) who completed two doses of inactivated COVID-19 vaccine and received any of these booster vaccines (Ad26.COV2.S, ChAdOx1, or mRNA-based) at least 12 months prior were enrolled. Immunogenicity data (anti-Spike (S) IgG, neutralization antibody titer (NT50) against ancestral and XBB.1.5, and S-specific IFN-γ T- cells) was obtained at baseline, Day 28±7, and Day 90±14. Of 190 participants enrolled; 57 received Ad26.COV2.S, 66 received ChAdOx1, and 67 received mRNA vaccine as the third dose, respectively. Following bivalent mRNA vaccination, anti-S IgG rose at Day 28, and declined at Day 90. In contrast, the NT50 titers against ancestral peaked at Day90. The NT50 against XBB.1.5 peaked at Day 28 with the highest fold rise in the mRNA vaccine subgroup (29.16 [19.55–43.49]), followed by the ChAdOx1 (20.94 [14.18–30.92]), and the Ad26.COV2.S subgroups (13.04 [8.61–19.74]). Geometric concentration of T-cells producing IFN-γ rose comparably in all three subgroups. Bivalent mRNA ancestral/BA.4/5 vaccine enhanced humoral immunity against both ancestral and Omicron XBB1.5, and T-cell immunity in inactivated COVID-19 vaccine primed with different heterologous boost participants. The study was registered at WHO platform: Thai Clinical Trial Registry (TCTR20230811004).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) vaccines are effective in preventing symptomatic infection, reduce morbidity and mortality1,2,3. Vaccine effectiveness varies among various vaccines with different platforms4,5. It has been shown that heterologous prime-boost vaccination induces stronger immune responses than homologous prime-boost strategy6,7 However, despite prompt vaccination campaign and early vaccine rollout, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) has evolved over time, leading to numerous outbreaks since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic8,9,10. Consistent with the global epidemiology, the largest outbreak in Thailand occurred during the 5th wave from January to June 2022, driven by the Omicron variant11,12. Many vaccine companies have adapted their vaccine designs to improve vaccine efficacy against variants of concern. For instance, bivalent mRNA vaccines such as BNT162b2 ancestral/BA.4/5 and Spikevax ancestral/BA.4/5 became available in 2022 to better target Omicron variant. Authorities in many countries recommended boosting immune response with additional vaccine dose; however, data on optimal timing is still limited. In addition, data on heterologous boost with bivalent mRNA vaccines in individuals primed with inactivated COVID-19 vaccines, which were available in many countries in Asia initially, is scarce. Furthermore, presence of hybrid immunity also likely has an impact of boosting effect which further complicates appropriate vaccine recommendation6. This study aimed to evaluate the vaccine responses both humoral and T-cell response to a booster bivalent mRNA ancestral/BA.4/5 COVID-19 vaccine in those who have previously received two doses of inactivated COVID-19 vaccines (CoronaVac or BBIBP-CorV) followed by a third dose of any of the three different platforms (Ad26.COV2.s, ChAdOx1, or mRNA) at least one year prior.

Methods

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University (MUTM 2023-028-01) The study was registered at WHO platform: Thai Clinical Trial Registry (TCTR20230811004). All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. All study procedures involving participants and the handling and analysis of their specimens were conducted in accordance with institutional, national, and international guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki, ICH GCP. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.”

Study design and study population

An open-label prospective study of bivalent Spikevax Ancestral/Omicron BA.4/5 was conducted at the Vaccine Trial Centre, Bangkok, Thailand from June to October 2023. Healthy adult participants (age > 18) who completed two doses of inactivated COVID-19 vaccine and received any of these booster vaccine (Ad26.COV2.S, ChAdOx1, or mRNA platform more than 12 months prior, were enrolled. Participants with recent (within four months) or current COVID-19 infection, confirmed or suspected immunodeficient state, acute polyneuropathy, contraindication to intramuscular injections or blood draws, major active psychiatric illness, recent COVID-19 vaccination within three months, recent vaccination (14 days for non-live vaccine and 28 days for live vaccine), recent immunoglobulins infusion within three months, or blood transfusion within four months were excluded.

Participants were allowed to have four vaccine doses before enrolment. All participants were administered intramuscular Spikevax bivalent Ancestral/Omicron BA.4/5.

Data collection

There were three study visits for each participant: Day 0 (V1), Day 28 ± 7 (V2), and Day 90 ± 14 (V3). Demographic data, medical history, previous vaccination history, and previous COVID-19 infection history were collected at V1. Diary card used to record local and systemic reactogenicity and solicited safety data for the first 7 days post-injection (as shown in supplementary tables) and all vaccine safety data collection continued and reviewed at V2 and V3. For each visit, 20 mL blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes, processed within 2 h, and stored at − 80 °C until analysis.

Immunogenicity

IgG antibodies to full-length pre-fusion spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 (anti-S RBD IgG) levels were quantified using a validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Roche Diagnostics. Elecsys® Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S assay; 2023.) expressed in ELISA units (U)/mL and converted to binding antibody units (BAU)/mL using the WHO international standard correlation factor (0.97) (at the Central Lab, Hospital for Tropical Diseases, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University). Seropositivity for anti-S IgG was defined as > 0.8 BAU/mL per WHO standard (Roche Diagnostics Elecsys® Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S assay). Vaccination-induced neutralizing antibody inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 was quantified by SARS-CoV-2 Pseudovirus neutralization assay (PNA) and defined as 50% neutralizing titer (NT50) against Pseudovirus bearing spike proteins of Ancestral strain, and Omicron XBB.1.5 from baseline, at 28 and 90 days (at the National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (BIOTEC), Thailand). 60% of the collected blood samples at all time points were subjected for SARS-CoV-2 T-cell responses using an interferon-gamma release ELISA assay (Euroimmun, Lubeck, Germany) (Thammasat University Laboratory)6. All labs meet international standards by employing validated protocols and adhering to the applicable cGLP and biosafety guidelines.

Data analysis

The study aimed to recruit approximately 200 participants with an equal number of participants in each subgroup based on the vaccine platform received at dose three i.e., Ad26.COV2.S, ChAdOx1, or mRNA. Data was analyzed according to these subgroups and further stratified by the presence of hybrid immunity. Participants who reported symptomatic COVID-19 infection before bivalent mRNA vaccine administration were defined as having hybrid immunity. Baseline demographics were reported using descriptive statistics. Safety data analyses included unsolicited adverse events (AEs) at Day 28, and serious adverse events as well as adverse events of special interests, which included immune-mediated medical condition and AEs associated with COVID-19 infection, throughout the entire study period. Per protocol population defined by all subjects who received bivalent mRNA vaccine and had no major protocol deviations that were determined to potentially interfere with the immunogenicity assessment of the study product was used for immunogenicity analysis. Anti-S IgG results were summarized with 95% Clopper-Pearson confidence interval (95%CI), geometric mean concentrations (GMC), and geometric mean fold rise (GMFR) from baseline. NT50 results were summarized with 95%CI, geometric mean titer (GMT), GMFR from baseline against ancestral and Omicron XBB.1.5 SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus. At baseline GMC and 95%CI was adjusted for age; At other visits, GMC/GMT and 95%CI were adjusted for age and baseline log-antibody concentration/titer. Data was analyzed, and tables/figures were generated using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

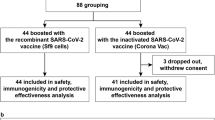

A total of 196 potential participants were screened. Of these, 58 received Ad26.COV2.S, 69 received ChAdOx1, and 69 received mRNA platform vaccine as their third dose (Fig. 1). An attempt was made to recruit an equal number of participants in the three subgroups. However, since Ad26.COV2.S was not widely available in Thailand, slightly fewer participants were screened for this group. Ultimately, six individuals were deemed ineligible and were not enrolled, resulting in a total of 190 participants included in the study. This consisted of 57, 66, and 67, in the Ad26.COV2.S, ChAdOx1, and mRNA vaccine subgroups, respectively (Fig. 1). All patients except one in the mRNA vaccine subgroup completed Day 90 study visit. Demographics of the study participants were summarized in Table 1. higher proportion of female participants were enrolled across groups, 66.7% of participants in the ChAdOx1 subgroup received vaccine dose 4 before study enrolment, whereas 14% and 43.3% of Ad26.COV2.S and mRNA vaccine subgroups received dose 4 respectively. Almost all participants (77/81, 95.1%) who had four doses had mRNA vaccine as their fourth dose (Table 1). Nevertheless, mean time since last dose was similar across all three subgroups (15.1 to 17.2 months, Table 1). There were 52.6%, 54.5% and 51.5% participants in each of three subgroups reported history of COVID-19 infection (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). The mean time since last infection was 11 ± 4.2, 10.6 ± 3.9, and 12.3 ± 2.9 months, respectively. There was no reported symptomatic COVID-19 infection during the study period.

Humoral immune response

GMC (95% CI) of anti-S IgG at baseline before bivalent mRNA vaccination was 5,091.43 (3,713.95–6,979.80), 5,617.86 (4,476.63–7,050.04), and 5,763.49 (4,615.08–7,197.68) BAU/mL, for the Ad26.COV2.S, ChAdOx1, and mRNA vaccine boosted subgroups, respectively (Fig. 2). Following bivalent (Ancestral/BA.4/5) mRNA vaccination, anti-S IgG rose by 6.62 (4.46–9.26), 7.81(6.07–10.06), and 7.52 (5.81–9.73) folds at Day 28. The anti-S IgG concentration declined at Day 90 but was still higher than baseline by 3.36 (2.51–4.50), 4.04 (3.16–5.16), and 4.37 (3.37–5.67) folds, respectively (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Geometric Mean Concentration (GMC) of 2a) Anti-Spike IgG and Geometric Mean Titer (GMT) of 50% Neutralization Titer (NT50) against 2b) Ancestral SARS-CoV-2 and 2c) XBB.1.5, per protocol analysis. Each dot represents an individual participant’s data. The upper and lower ends of the whisker box indicate the 95% confidence interval (CI). Error bars represent the range. The mean values and 95% CIs are presented in the table below each plot. The mean fold rise values are also shown as numerical values with x. V1 - visit 1 or on day1, V2 - visit 2 or on day 28, and V3 - visit 3 or on day 90. *p-values were not calculated, as this study was not designed for hypothesis testing between groups.

NT50 titers against ancestral strain increased at Day 28 and further increased at Day 90 to 8.86 (7.42–10.57), 8.18 (6.24–10.72), 10.98 (7.87–15.32) folds from baseline (Table 2; Fig. 2). Interestingly, NT50 titers against XBB.1.5 increased at Day 28 from baseline with the trend of highest fold rise in the mRNA vaccine subgroup (GMFR 29.16 (19.55–43.49) folds), followed by the ChAdOx1 (20.94 (14.18–30.92) folds) and the Ad26.COV2.S subgroups (13.04 (8.61–19.74) folds)(Table 2; Fig. 2). However, at Day 90, NT50 titers declined from Day 28 though higher than the baseline values (Table 2; Fig. 2). P-values were not calculated, as this study was not designed for testing between groups. Overall, there was not a significant difference in anti-S IgG, NT50 (Ancestral) and NT50 (XBB.1.5) in participants who had received ChAdOx1 booster compared to participants previously received mRNA-based vaccine as third dose (Fig. 3). In addition, NT50 (XBB.1.5) trended to be higher at Day 28 and Day 90 following bivalent mRNA vaccination (GMR 0.82 (0.63–1.06) and 0.79 (0.55–1.12), Fig. 4) in participants with reported prior symptomatic COVID-19 infection than those without. The importance of time since last infection in the hybrid subgroup was also explored. There did not appear to be a significant difference in humoral immune response between time since last infection of < 12 months vs. ≥12 months (Supplementary Tables 1–4). Although the GMR values suggested trend toward higher responses in the mRNA subgroup compared to vector-based subgroups, the study was not powered to test statistical significance between groups. Thus, these findings are presented as descriptive trends only.

Geometric Mean Ratio (GMR) comparing humoral immunogenicity (Anti-S IgG, 3a; NT50 against ancestral, 3b; NT50 against Omicron XBB.1.5, 3c) after boosting of bivalent mRNA COVID-19 vaccine between mRNA-based vs. Ad26.COV2.S vector-based or between mRNA-based vs. ChAdOx1 vector-based vaccine at dose 3, per-protocol analysis. A GMR value of less than 1.0 indicates that the previously received mRNA platform vaccine has a better response to the bivalent booster than the previously received vector-based vaccine.

T cell response

Median IFN-γ production from T-cells following Spike peptide stimulation was 1,851.51 (1,612.59–2,389.94) mIU/mL and rose to 5,277.24 (4,377.17–6,133.8) at Day 28 then declined to 3,501.51 (2,560.48–4,181.70) at Day 90. Median T-cell response appeared to be the highest in the group who received mRNA vaccine as third dose; however, the 95% CI was wide 2,714.69 to 7,007.90 mIU/mL (Fig. 5). Among participants with previous symptomatic infection, T-cell response did not appear to be different between time since last infection of < 12 months vs. ≥12 months (Supplementary Table 5).

Median of IFN-γ production from SARS-CoV-2 specific T cells. Each dot represents an individual participant’s data. The upper and lower ends of the whisker box indicate the 95% confidence interval (CI). Error bars represent the range. V1 - visit 1 or on day1, V2 - visit 2 or on day 28, and V3 - visit 3 or on day 90.

Safety data

There were five severe adverse events reported from five patients during the first 28 days (Table 3). None was related to the bivalent mRNA vaccine and resolved within the follow-up period without sequelae. There were no fatal or potentially life-threatening events were reported, no serious adverse events or adverse events of special interests reported throughout the entire study period.

Discussion

In this study, we reported that the bivalent mRNA vaccine enhanced both humoral and T-cell mediated immune responses in inactivated vaccine primed participants boosted with three different vaccines – Ad26.COV2.S, ChAdOx1, and mRNA vaccine, with the effect being more pronounced in the mRNA subgroup. We found that functional antibody against the ancestral strain continued to rise at three months post vaccination, unlike anti-S IgG which had already waned at three months. Additionally, we observed trend toward higher fold change in NT50 against XBB.1.5 at Day 28 following the bivalent vaccination particularly those with a history of previous COVID-19 infection and waned by Day 90, suggesting immune imprinting effects despite initial high fold-rise at Day 28. Variance of T-cell response was wide but appeared to be stable overtime without significant waning at three months, especially those previously receiving monovalent mRNA vaccine.

The observed difference in kinetics of binding antibody and neutralizing antibody titers against ancestral SARS-CoV-2, i.e., NT50 continued to increase at Day 90 while anti-S IgG peaked at Day 28 and waned at Day 90, was consistent with the existing literature and likely due to the natural B-cell maturation process13 Moriyama et al. showed that while total antibody titers declining, neutralization potency per antibody to ancestral SARS-CoV-2 improved overtime, indicative of antibody response maturation14.

Substantial increase in NT50 against XBB.1.5 compared to NT50 against the ancestral strain following bivalent ancestral/BA.4/5 vaccination is intriguing. This rise is likely due to the absence of prior exposure to XBB.1.5 in most participants, as indicated by the very low baseline GMT (Fig. 2.3). Other study reported that bivalent (ancestral/BA.4/5) booster induced neutralizing antibodies against Omicron sub lineages but lowest to XBB.115. Although we did not measure neutralizing antibodies against Omicron sub lineages in our study, it was possible that NT50 titers could have been higher against earlier Omicron sub lineages such as BA.4-BA.5. It was reported that inactivated vaccine can induce broadly neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants which might partially explain NT50 results in our study where all participants were primed with inactivated vaccines16.

Notably, our study observed a higher NT50 titer against XBB.1.5 in participants with a history of symptomatic infection – most of whom were infected during the Omicron BA.1 outbreak, this suggests that Omicron-primed immunity may enhance the response to the Omicron-specific mRNA vaccine more effectively than previous exposure to the ancestral Spike epitope through vaccination alone. Recent work has shown that antibody responses to Omicron variants are dominated by pre-existing immunity resulting from prior exposure to ancestral strain, due to immune imprinting, rather than priming Omicron-specific naïve B cells17. In addition, repeated vaccination decreased breadth of the antibody response18 as shown by relative reduction in the reactivity of the sera with the other variants compared to the ancestral strain, was observed after the second boosting vaccination against the ancestral strain. Longitudinal monitoring of anti-S IgG subclasses following three doses of mRNA monovalent vaccination showed that IgG4 became dominant with repeated vaccine doses. This was accompanied by reduced fragment crystallizable (Fc) gamma receptor-mediated effector functions such as antibody dependent cell phagocytosis19. Another study of a man who was hypervaccinated with over 200 vaccine doses within a period of 29 months revealed that hypervaccination increases the quantity, but not the quality of the adaptive immunity20. Together, it is conceivable that vaccination against new variants would enhance both quantity and quality of the adaptive immunity than repeated vaccination with the same antigenic epitope.

Our immunogenicity data in individuals receiving heterologous prime-boost vaccines showed that despite time since last vaccine dose or last infection was longer than twelve months, there were still high levels of anti-S IgG, NT50 titers, and S-specific T cell response before the bivalent booster (Figs. 2 and 4), unlike studies in countries where people received mRNA-based vaccine only21. This suggests that heterologous prime-boost strategy may allow a longer interval between boosters as there was a stronger immune response than homologous prime-boost strategy, consistent with other report22. The magnitude of the response observed in our study is comparable to that reported in other studies evaluating bivalent vaccine responses following heterologous prime-boost strategies with approximately one-year vaccine intervals23and homologous prime-boost strategies with shorter intervals, such as six months24. This suggests longer vaccine interval in the heterologous prime-boost strategy could be considered, although further research especially the data on vaccine effectiveness is needed.

Given that there is no clear correlate of protection against SARS-CoV-2, we cannot conclude based on our immunogenicity data if the bivalent mRNA booster in our setting where individuals were primed with inactivated vaccine would confer a strong vaccine effectiveness. In the US where most of the population had mRNA vaccines as primary series and again boosted with mRNA vaccines as 3rd or 4th dose, vaccine effectiveness following bivalent boosters against hospitalization or death waned from approximately 67.4% after 2 weeks to 38.4% after 20 weeks25. In contrast, the vaccine effectiveness of boosted BNT162b2 vaccine in individuals previously primed with two doses of Sinovac-CoronaVac offered high levels of protection against severe or fatal outcomes (97.9% [97.3–98.4]) after eight weeks4. Furthermore, another study in Hong Kong reported increased vaccine effectiveness against Omicron BA.4 infection in people receiving bivalent Ancestral/BA.4/5 vaccine as 4th dose following three doses of Sinovac-CoronaVac previously versus individuals who received homologous four doses of Sinovac-CoronaVac26. Thus, vaccine effectiveness may be different in countries where there was a great mix of vaccine platforms given to population from dose one to dose four.

Among different heterologous boosting regimens, the mRNA subgroup showed the highest immune response, while the Ad26.COV2.S subgroup elicited the lowest response to bivalent mRNA vaccination, though the difference did not show statistically significant. This outcome may be confounded by the lower proportion in the Ad26.COV2.S subgroup with four prior vaccine doses (14%) compared to the mRNA (43.3%), and the ChAdOx1 (66.7%) subgroups with this more individuals in the ChAdOx1 subgroup had received 4 doses, while Ad26.COV2.S subgroup had received mostly 3 doses prior to study dose. This imbalance may have influenced the observed immune responses and might influence the interpretation of subgroup comparisons.

Similarly, our finding of T-cell response with insignificant waning at three months after booster is consistent with other reports27,28,29. In fact, our study showed that T-cell response was durable even more than 12 months since last vaccination or last infection as shown in the values of IFN-γ production from stimulated T-cells at baseline visit before bivalent mRNA vaccination. Nevertheless, this interpretation should be approached with caution, given the wide 95% CI observed in our study (Fig. 5). The wider 95% CI observed in the mRNA subgroup which reflects the greater variability in individual T-cell responses due to small sample size and/or duration of COVID-19 infections prior to receiving the bivalent mRNA vaccine [30].

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. The classification of hybrid immunity relied on a history of symptomatic COVID-19 infection, which may have led to misclassification if asymptomatic infections before enrollment were missed. As this was a single-center study with modest subgroup sizes. In addition, only a small number of participants received the booster less than 12 months after their last vaccination or infection, restricting our ability to evaluate the impact of interval length on immunogenicity. However, the study results are in line with the other publications as cited earlier.

Conclusion

Boosted immune response with bivalent mRNA vaccine was shown in all subgroups who had different heterologous prime-boost regimens. Having previous COVID-19 infection improved NT50 titers against XBB.1.5 but not anti-S IgG and NT50 against ancestral following bivalent mRNA vaccination. T-cell response did not wane as fast as humoral immune response. Overall, The results provide immunological evidence that bivalent mRNA vaccines can enhance humoral and cellular responses in individuals previously primed with inactivated vaccines, including against Omicron XBB.1.5. These data may inform vaccine strategies targeting emerging variants of concern; however, clinical protection was not directly assessed in this study.

Data availability

Data could be shared upon request to the corresponding author at punnee.pit@mahidol.ac.th.

References

Sheikh, A., Robertson, C. & Taylor, B. BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine effectiveness against death from the delta variant. N Engl. J. Med 385, (2021).

Sritipsukho, P. et al. Comparing real-life effectiveness of various COVID-19 vaccine regimens during the delta variant-dominant pandemic: a test-negative case-control study. Emerg Microbes Infect 11, (2022).

Watson, O. J. et al. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis 22, (2022).

McMenamin, M. E. et al. Vaccine effectiveness of one, two, and three doses of BNT162b2 and coronavac against COVID-19 in Hong kong: a population-based observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 1435–1443 (2022).

Kudlay, D., Svistunov, A. & Satyshev, O. COVID-19 vaccines: an updated overview of different platforms. Bioeng 9, (2022).

Muangnoicharoen, S. et al. Heterologous Ad26.COV2.S booster after primary BBIBP-CorV vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 infection: 1-year follow-up of a phase 1/2 open-label trial. Vaccine https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.05.010 (2024).

Jara, A. et al. Effectiveness of homologous and heterologous booster doses for an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a large-scale prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 10, (2022).

Infectious Diseases Society of America. COVID-19 variant update. https://www.idsociety.org/covid-19-real-time-learning-network/diagnostics/covid-19-variant-update/

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern as of 30 August 2024. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/variants-concern

American Medical Association. Genetic variants of SARS-CoV-2—What do they mean? https://jamanetwork.com/

World Health Organization. Thailand country profile. https://www.who.int/countries/tha

World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19–29 June (2022). https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---29-june-2022

Yang, Y. et al. Longitudinal analysis of antibody dynamics in COVID-19 convalescents reveals neutralizing responses up to 16 months after infection. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 423–433 (2022).

Moriyama, S. et al. Temporal maturation of neutralizing antibodies in COVID-19 convalescent individuals improves potency and breadth to Circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants. Immunity 54, (2021).

Zou, J. et al. Neutralization of BA.4–BA.5, BA.4.6, BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1, and XBB.1 with bivalent vaccine. N Engl. J. Med. 388, 854–857 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Inactivated vaccine-elicited potent antibodies can broadly neutralize SARS-CoV-2 Circulating variants. Nat Commun 14, (2023).

Tortorici, M. A. et al. Persistent immune imprinting occurs after vaccination with the COVID-19 XBB.1.5 mRNA booster in humans. Immunity 57, 904–911e4 (2024).

Horndler, L. et al. Decreased breadth of the antibody response to the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 after repeated vaccination. Front Immunol 14, (2023).

Irrgang, P. et al. Class switch toward noninflammatory, spike-specific IgG4 antibodies after repeated SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Sci Immunol 8, (2023).

Kocher, K. et al. Adaptive immune responses are larger and functionally preserved in a hypervaccinated individual. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24, e272–e274 (2024).

Suthar, M. S. et al. Durability of immune responses to the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine. Med. 3, (2022).

Kim, D. I. et al. Immunogenicity and durability of antibody responses to homologous and heterologous vaccinations with BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1 vaccines for COVID-19. Vaccines (Basel) 10, (2022).

Hyun, H. J. et al. Neutralizing activity against BQ.1.1, BN.1, and XBB.1 in bivalent COVID-19 vaccine recipients: comparison by the types of prior infection and vaccine formulations. Vaccines (Basel) 11, (2023).

Collier, A. Y. et al. Immunogenicity of BA.5 bivalent mRNA vaccine boosters. N Engl. J. Med 388, (2023).

Lin, D. Y. et al. Durability of bivalent boosters against Omicron subvariants. N Engl. J. Med. 388, 1818–1820 (2023).

Jiang, J. et al. Assessing the impact of primary-series infection and booster vaccination on protection against Omicron in Hong kong: a population-based observational study. Vaccines (Basel). 12, 1014 (2024).

Taus, E. et al. Persistent memory despite rapid contraction of Circulating T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Front Immunol 14, (2023).

Stieber, F. et al. Durability of COVID-19 vaccine induced T-cell mediated immune responses measured using the quantiferon SARS-CoV-2 assay. Pulmonology 29, (2023).

Guerrera, G. et al. BNT162b2 vaccination induces durable SARS-CoV-2–specific T cells with a stem cell memory phenotype. Sci Immunol 6, (2021).

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank National Research Council of Thailand and Mahidol University for funding supports. We also would like to thank all the staff at the Vaccine Trial Centre for their due diligence.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) and Mahidol University [Fund No. N42A660809].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM study conception and design, data collection, data interpretation, manuscript drafting; SL- data management, data analysis, visualization, JC first manuscript draft writing, data analysis and interpretation; VL-data collection, data interpretation; AJ data collection, analysis, data validation and interpretation; SN data collection, data interpretation, validation; WP data collection; SK- data collection; NT- data collection; CD-data collection and validation; PP study conception and design, data interpretation, study guarantor, grant awardee. All authors critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Mahidol University Institutional Research Ethics Board (MUTM 2023-028-01).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muangnoicharoen, S., Lawpoolsri, S., Cowan, J. et al. Immune responses after two inactivated COVID-19 vaccine doses, a heterologous third dose and subsequent boosting with bivalent mRNA in adults. Sci Rep 15, 45555 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29686-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29686-9