Abstract

The koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) is an endangered species in parts of Australia, in part due to chlamydial infections. Treatment is difficult due to the hepatic metabolism of the koala, and the critical reliance on a gut microbiota for survival. This study aimed to identify new compounds for treatment of Chlamydia infections by screening a drug re-purposing library. Screening was conducted using an in vitro cell culture model prior to in vivo mouse infection model testing of two candidates identified from the in vitro screen. One lead, bisoprolol fumarate, showed an impact on chlamydial infection and burden in vitro and in vivo. Whilst the mechanism of action may not support progressing this lead further, the approach to screening the library and list of candidates may enable identification of other new koala treatments. This study demonstrates the potential to apply drug re-purposing to koala treatment and presents a list of candidates that could be explored further.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Australia’s iconic native marsupial species, the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus), is declining in population in large regions due to habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, and disease1. The koala population is now estimated to be approximately 330 000, from an estimated peak population of millions1. Koala were added to the Australian Environmental Protection Biodiversity Conservation Act in 20122for populations in the northern half of Australia. Koala population stability is a priority for both preservation of the species but also the economic value of the associated tourism industry, estimated at up to $3.2 billion Australian dollars3. One contributing factor to the decline is chlamydiosis caused by infection with the obligate intracellular bacterial pathogen, Chlamydia4. Chlamydia are obligate intracellular Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. The organism undergoes a bi-phasic developmental cycle, consisting of extracellular infectious forms that are non-replicative (elementary bodies). A second intracellular, replicative forms (reticulate bodies, found inside specialized intracellular vacuoles) that undergo multiple rounds of replication and eventually re-differentiate into the infectious form5,6. Chlamydia (C.) pecorum has been reported in many mainland koala populations4. There have been previous reports of Chlamydia (C.) pneumoniaeinfections in koala but these seem to be isolated events (reviewed7,). C. pecoruminfections in koala share many hallmarks of the biology and disease presentation that have been reported for chlamydial diseases in other animal hosts, notably ocular and urogenital diseases (reviewed8,). In the case of ocular disease, infection is within the epithelia of the conjunctiva of the eye, which leads to chronic conjunctivitis and keratoconjunctivitis, which can result in corneal scarring and may progress to blindness9. Reproductive tract infection and symptomatic presentations have been detected throughout the male and female reproductive tract with inflammation, scarring and infertility resulting from the tissue damage9. Urinary disease in the koala can impact the urethra, bladder, ureters and kidneys resulting in urethritis, cystitis, urethritis, or pyelonephritis. These are painful and can lead to urinary incontinence. This incontinence results in visible urine staining of the fur in the rump region, referred to as ‘wet-bottom’ 9. The infection and disease prevalence varies by population7.

Koalas are specialized Eucalyptus folivores who exhibit unique physiological, reproductive and dietary characteristics, including the ability to ingest and metabolize toxic plant metabolites such as phenolic compounds and terpenes10. The unusual metabolism results in limited efficacy of antibiotic treatment. As their efficient hepatic metabolism has been proposed to increase the rate of elimination of some therapeutic drugs11. A particular concern with the treatment of the koala is that antibiotic-induced dysbiosis of the gut microbiome can be fatal. This makes antibiotic approaches to treat infected koalas difficult to test. Further, some antibiotic treatments can be ineffective in clearing chlamydial infections of the lower genital tract12. Currently the most effective and commonly used antibiotic therapy for koalas with urinary-genital tract infections is systemically administered chloramphenicol (chloramphenicol 150; Delvet, Seven Hills, NSW, Australia)13. This antibiotic has been observed clinically in koalas to have fewer detrimental effects on their specialized gut microbiota, compared to other medications13. However, this treatment does not always effectively clear infections, even after lengthy durations of treatment. Whilst chloramphenicol is the most commonly used antibiotic, with a 60 mg/kg dosage for 14–28 days working well (95% successful treatment14 on a subset of koalas with a positive prognosis, it has severe side effects including caeco-colic dysbiosis (gut microbiome impacts), and bone marrow depression14. Enrofloxacin has proven ineffective with treatment failure observed in animals, and laboratory minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing, establishing susceptibility is higher than the conventional dosage regimen15,16. Doxycycline, florfenicol, and penicillin G have all also been tested in vivo or in vitro with little evidence to support proceeding with these antibiotics (reviewed, 7). Vaccination has been explored17,18 and shows promising indications. The vaccine has not yet been widely implemented. Overall, additional therapeutic approaches are needed to treat chlamydia infections in koala. Here a drug re-purposing library was screened to identify new possible treatments for koalas with chlamydial infection19.

Methods

Study design and in vitro screening model

An in vitro screening study was conducted to examine a drug re-purposing library (Sellekchem, Cat. No L1300) for compounds effective against C. pecorum. Leads identified during the in vitro screening were progressed to an in vivo model. A selection process was followed as outlined in Fig. 1A. The first step was to conduct a single dose high throughput screen of the library of 3065 compounds. This selection round used a stringent threshold of 0% infection (no detectable inclusions after drug treatment) to shortlist only the most promising candidates to progress to the next stage. This screen was conducted in vitro on McCoy B (source ATCC: CRL-1696) cell cultures infected with C. pecorum at a multiplicity of infection of 1.0 (MOI), with the drugs added at 4 h post infection (h PI) at 200 µM. Cultures were fixed and screened for visible inclusions at 44 h PI, consistent with past protocols20,21. The strain previously referred to as C. pecorum G was used in this study22. The fixed cell cultures were screened in 96 well plates using the INCEL high content analyser (GE Healthcare). Immunocytochemistry for HtrA, alpha-tubulin, with DAPI to stain the nucleus was conducted to enable detection of inclusions20,21. Analysis and counting of the inclusions present with visible host cells (controls to ensure the monolayer was not impacted) was conducted using an imageJ algorithm in FIJI23. 43 candidates were selected in this first screening round with the basis that no inclusions but clear host cell monolayer consistent with the untreated wells was maintained. These candidates were then screened with a dose series. The dose series experiment consisted of a cell culture infection model, with the candidate drugs added at 4 h PI, and visible inclusions determined at 44 h PI. The dose series used was 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 150, 200 µM. Candidates that resulted in a dose responsive reduction in inclusions and were effective at lower doses were selected. 24 candidates were shortlisted from the second stage of the screen, these are listed in Supplementary Table S1 according to the selection criteria listed below. Combined, this screening and selection process resulted in six candidates any of which could have potentially progressed to further investigation, as listed in Supplementary Table S1. Two candidates were selected to be examined further using the in vivo model. The in vivo model is conducted with the mouse strain of chlamydia (C. muridarum). To confirm activity against this strain the in vitro protocol (as outlined above) was repeated on the selected candidates with C. muridarum culture. C. muridarum (strain: Weiss) infections to McCoy B cells were treated with a dose series of the two lead compounds and monitored for impact on the inclusions. This in vitro method was as outlined above.

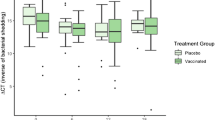

A. Selection protocol to identify potential candidates in the drug repurposing library. The figure shows a summary of the selection protocol that was followed to identify candidates from the re-purposing drug library. B-E: Anti-chlamydial in vitro efficacy of the candidates (bisoprolol fumarate and gemfibrozil, x axis dose series in µM). Relative to positive controls that were untreated and 20% DMSO: Saline controls. C. pecorum and C. muridarum was tested in McCoy B cell culture and % inclusions per field of view assessed. F. in vivo model showing vaginal shedding of infectious chlamydia with intraperitoneal injections of the candidates. Relative to positive controls that were untreated and 20% DMSO: Saline controls. G. Assessment of total infectious yield for statistical significance (Area under the curve (AUC), y axis), and treatment conditions indicated on the x axis.

Selection criteria

To determine which candidates to test using the in vivo model a set of criteria was determined by the authorship team. The criteria included eliminating established antibiotics or antimicrobials as these are likely to risks of gut microbiome dysbiosis severe to koala. Hormone based drugs were eliminated from further consideration for the following reasons. Hormonal therapies have a range of impacts on chlamydial biology24,25. These impacts are transient in nature, could involve induction of chlamydia persistence24,25. This means that hormones are unlikely to effectively clear the bacterial infection. In the context of chlamydia, persistence is a third form of the developmental cycle that arises under unfavourable conditions, as it is morphologically distinct, and is a non-culturable (e.g. not infectious) but is viable and can restore to an infectious form26. Previously reported adverse toxicity or severe side effects identified in past literature or product information sheets was also used to rule out drugs from further analysis (Supplementary materials Table S2). Such side effects may be tolerable for treatments for serious and potentially fatal diseases like cancer, but the authors agree they would not be appropriate to treat chlamydial infections in koalas. The shortlisting of candidates from each step considered all of these selection criteria. Combined, these criteria with the in vitro data showing dose dependent reduction in inclusion vacuoles was used to determine candidates which all could have progressed for further investigation in vivo. Candidates representing distinct mechanisms of action and both had what the authors considered to be the least documented adverse impacts were selected to progress.

In vivo model

The in vivo study was conducted as previously described on 6-week-old progesterone synchronised female mice, BALBc, sourced from the Animal Resource Centre Australia20,21. The study design was a case-control study to monitor response to treatment. The sample size was estimated based on previous published experiments with 10 mice included per group27,28. There was no randomisation or blinding in the study, all investigators were aware of the different treatments at use. Treatment and vehicle control animals were monitored and animal welfare checks were routinely implemented. Purified C. muridarum (strain: Weiss) was administered (5 × 104 IFU/20 µL of SPG) into the vaginal vault to initiate the infection. Intraperitoneal injections of bisoprolol fumarate or gemfibrozil (Sigma Aldrich) were administered daily (5 mg/kg/day; for day 2–10 of the mouse model). Intravaginal lavage samples were collected in SPG and analysed for shedding of viable chlamydia, as previously reported20 (Fig. 1F, G). Statistical analysis was performed using the Graph-Pad Prism 9 software (Graph-Pad, CA, USA). The total infectious units shed from the animals were analysed by converting the data in Fig. 1F to an ‘area under the curve’ as has been previously reported for this model29. The total area under the curve for each treatment condition was compared using ordinary one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test relative to the untreated control (Fig. 1G). The in vitro experimental data was also tested using this software, dose responses were compared using ordinary one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test to compare each dose to control (Fig. 1B and E). All animal experiments were conducted with the approval from the University of Technology Sydney Animal Care and Ethics Committee (ACEC ETH22-7172) and in accordance with the guidelines described by the Australian National Health and Medical Research council code of conduct for animals. The study was conducted and is reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org/).

Results

The screening protocol step described in the Materials and Methods (outlined Fig. 1A) resulted in a shortlist of 24 candidates that showed a high anti-chlamydial impact at 200 µM. These candidates also showed a dose responsive reduction in inclusion vacuoles during an experiment to determine the impact of the drug in a a dose series in cell culture (Supplemental Material, Table S1). The candidates identified included many different compound types. The screening identified known antibiotics, and hormone-based products, both of which are expected to impact chlamydial growth. Six candidates were progressed from this list for further investigation in this study based on the selection criteria outlined in the Materials and Methods section (Supplemental Material, Table S1). These candidates were bisoprolol fumarate, carvedilol, gemfibrozil, ivacaftor (VX-770), tiagabine, and zafirlukast. These candidates, outlined in Supplementary Table S1, had a range of primary treatment applications and drug mechanisms. 2 candidates were selected to test using the in vivo model (gemfibrozil and bisoprolol fumarate), as outlined in the selection criteria in the materials and methods section.

The in vivo mouse model uses C. muridarum, so we confirmed in vitro activity against C. pecorum and C. muridarum (Fig. 1B-E). Both candidates showed a greater impact on reduction of inclusions for C. muridarum in McCoy B cell culture than C. pecorum, with dose dependent reductions in chlamydial inclusions apparent.

The mouse model of in vivo intravaginal infection with C. muridarum was conducted using intraperitoneal treatment with both drugs. The in vivo study identified that bisoprolol fumarate (shown in Fig. 1G) significantly reduced the burden of viable chlamydial infection in the mouse model. The clearance observed was not as effective as that reported with antibiotic therapy such as azithromycin30. Gemfibrozil did not have a notable effect on the infection in this in vivo model.

Discussion

Here we screened a drug re-purposing library in vitro and identified a range of expected and new compounds that impacted the formation of visible inclusions during a chlamydial cell culture infection model. We have provided shortlisted candidates from each stage of the screening process as Supplementary Table S1, so other investigators can progress any compounds of interest. The identification of known antibiotics in the screening process validates that the approach used was effective. The study is intended only as a pilot study to demonstrate the process and provide a list of candidates that could be explored further. Nonetheless, the screening protocol we implemented was effective to identify new candidates that could be further explored to treat koalas with chlamydial infections.

It is worth noting a comprehensive approach using a series of computational and experimental approaches has been recently published to identify novel candidates for chlamydial treatment31. This protocol used a computational approach to screen an electronic library of compounds, whereas here we used an existing library of compounds specifically available for re-purposing studies. The recently published protocol used a somewhat similar approach of screening for visible inclusions whilst checking for host cells to be maintained, although it used a high throughput approach and multiple doses were tested rather than the protocol here of shortlisting with a high threshold for single dose to select candidates to complete a dose series31. A further unique feature of the recently published work is the in vitro comparison of the drug efficacy against multiple chlamydial species. This protocol is an exciting contribution to the field, and interestingly a fatty acid synthesis protein was one of the discoveries of the possible target candidates for future drug development in this comprehensive process31.

One of the limitations in our study was to progress only two compounds to the mouse model. It may be that other candidates in the short list will have higher efficacy against chlamydia in the mouse and other in vivo contexts, but only two compounds were elected to be screened for the purpose of this study. Another limitation of the study is the selection of which two candidates to proceed. The authors shortlisted based on the range of criteria described in the methods, but it is certainly possible that any of the final six candidates were worthy of in vivo investigation. There is no laboratory animal model for C. pecorum infection and treatment studies that adequately mimic the biology of the koala. The use of C. muridarum and the mouse model can only provide limited insights into the likely efficacy of these drugs against C. pecorum and the koala and this should be considered a limitation. The use of multiple species and host cell lines in the recently presented larger study presents possible approaches to address such limitations in future31.

To select candidates to pursue further, an analysis of available data relating to each candidate was conducted. This included reviewing the literature, product information sheets where available, and product reports available in the public domain. The scope of this review was to understand possible mechanisms and to rule out those with previously reported adverse toxicity, side effects, hormonal therapies and established antibiotics or antimicrobials. Hormonal therapies were excluded because hormone concentration changes are known to impact chlamydial growth in vitro, but this is likely to be transient or through the induction of persistence26, so we elected to exclude these from further investigation for this study. We did not feel there was value in identification of known antibiotics or antimicrobials, given the potential for fatal impacts on the gut microbiome. Severe toxicity or adverse impacts that may be considered acceptable in some contexts would not be appropriate in the application to koala treatment for infection.

The two candidates are well known and long used human therapeutics. Bisprolol fumerate is a widely used beta-blocker (beta 1 adrenic receptor blocker) to treat hypertension and used in heart failure32. As McCoy B cell lines are a unique cell derived from a fibroblast cell type, we do not expect that this cell type would express beta-adrenoceptor, the target of bisoprolol fumarate. Thus, one explanation for this compound impacting chlamydial growth might be previously reported off target impacts on membrane fluidity that have been detected for other beta blockers33. The mechanism relating to the membrane fluidity is not fully elucidated but could well impact the chlamydial inclusion membrane and hence chlamydial infectivity or growth progress. Gemfibrozil was not significantly impactful on chlamydia infection during the in vivo study. This drug impacts on cellular lipid metabolism, specifically depleting intracellular fatty acid stores, via PPAR-alpha receptors34, a mechanism anticipated to directly impact on McCoy B cells as PPAR isoforms are expressed on fibroblasts. It is well established that the pathogen uses host cell fatty acids and lipids, so the identification of gemfibrozil could be considered to be consistent with literature35 relating to biological resources required by chlamydia. There are no prior reports to our knowledge of either of these two drugs having an impact on chlamydial growth. Genomic analysis does show differences between C. trachomatis (where much of the biological work has been conducted) and C. pecorum36. There are no biological or pathogenesis studies yet publish that explore fatty acid and lipid sequestering from host cells for C. pecorum. Therefore, it is unknown if the same host cell dependencies for lipids and fatty acids exist between the two species. The work here included only in vitro analysis on C. pecorum. There is no established koala cell line available for chlamydia culture, so it was also in a mouse model cell line commonly used in the chlamydia field. This needs to be considered in light of the data as the drugs could be acting indirectly via a host cell target. Additionally, the in vivo model study was conducted using C. muridarum. This is an important consideration as phylogenetically C. muridarum and C. trachomatis are more closely related than C. pecorum is to either of these two species37.

One approach to future applications of the compounds identified here could be combination therapies to increase the efficacy38. This could include combinations of novel leads, or combinations with lower doses of known antibiotics, to reduce the broad impact of the antibiotics on the koala gut microbiota, whilst still reducing the chlamydial infection. This might be worth further investigations in future. Overall, this pilot study demonstrates the potential for re-purposed therapies to treat koala chlamydial infections.

Data availability

All data and materials are within the manuscript and Supplementary Table S1.

Abbreviations

- h PI:

-

Hours post infection

- MOI:

-

Multiplicity of infection

- IFU:

-

Inclusion forming units

References

Government, N. (2016). http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/animals/TheKoala.htm.

The koala-. Saving our National Icon (Commonwealth of Australia, 2011).

https://www.savethekoala.com/our-work/the-koala-is-worth-3-2-billion-30000-jobs/

Polkinghorne, A., Hanger, J. & Timms, P. Recent advances in Understanding the biology, epidemiology and control of chlamydial infections in Koalas. Vet. Microbiol. 165, 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.02.026 (2013).

Ouellette, S. P., Lee, J. & Cox, J. V. Division without binary fission: cell division in the FtsZ-Less Chlamydia. J. Bacteriol. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00252-20 (2020).

Adbelrahman, Y. M. & Belland, R. J. The chlamydial developmental cycle. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29, 949–959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsre.2005.03.002 (2005).

Quigley, B. L. & Timms, P. Helping Koalas battle disease - Recent advances in chlamydia and Koala retrovirus (KoRV) disease Understanding and treatment in Koalas. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 44, 583–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuaa024 (2020).

Borel, N., Polkinghorne, A. & Pospischil, A. A. Review on chlamydial diseases in animals: still a challenge for pathologists? Vet. Pathol. 55, 374–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300985817751218 (2018).

Jelocnik, M., Gillett, A. & Hanger, J. Chlamydiosis in koalas 496–506 (CSIRO Publishing, 2019).

Jones, B. R., El-Merhibi, A., Ngo, S. N. T., Stupans, I. & McKinnon, R. A. Hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes belonging to the CYP2C subfamily from an Australian marsupial, the Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C: Toxicol. Pharmacol. 148, 230–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpc.2008.05.020 (2008).

GOVENDIR, M. et al. Plasma concentrations of Chloramphenicol after subcutaneous administration to Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) with chlamydiosis. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 35, 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2885.2011.01307.x (2012).

GRIFFITH, J. E., HIGGINS, D. P., LI, K. M., GOVENDIR, M. & KROCKENBERGER, M. B. & Absorption of Enrofloxacin and Marbofloxacin after oral and subcutaneous administration in diseased Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 33, 595–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2885.2010.01169.x (2010).

Black, L. A. et al. Pharmacokinetics of Chloramphenicol following administration of intravenous and subcutaneous Chloramphenicol sodium succinate, and subcutaneous Chloramphenicol, to Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 36, 478–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvp.12024 (2013).

Govendir, M. et al. Plasma concentrations of Chloramphenicol after subcutaneous administration to Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) with chlamydiosis. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 35, 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2885.2011.01307.x (2012).

Robbins, A., Loader, J., Timms, P. & Hanger, J. Optimising the short and long-term clinical outcomes for Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) during treatment for chlamydial infection and disease. PLoS One. 13, e0209679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209679 (2018).

Black, L. A., Higgins, D. P. & Govendir, M. In vitro activity of chloramphenicol, florfenicol and Enrofloxacin against chlamydia pecorum isolated from Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). Aust Vet. J. 93, 420–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/avj.12364 (2015).

Phillips, S., Quigley, B. L. & Timms, P. Seventy years of chlamydia vaccine Research - Limitations of the past and directions for the future. Front. Microbiol. 10, 70. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00070 (2019).

Phillips, S. et al. Immunisation of Koalas against chlamydia pecorum results in significant protection against chlamydial disease and mortality. NPJ Vaccines. 9, 139. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00938-5 (2024).

Cannon, M. et al. Large-Scale drug screen identifies FDA-Approved drugs for repurposing in Sickle-Cell disease. J. Clin. Med. 9, 2276 (2020).

Lawrence, A. et al. Chlamydia Serine protease Inhibitor, targeting HtrA, as a new treatment for Koala chlamydia infection. Sci. Rep. 6, 31466. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31466 (2016).

Gloeckl, S. et al. Identification of a Serine protease inhibitor which causes inclusion vacuole reduction and is lethal to chlamydia trachomatis. Mol. Microbiol. 89, 676–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/mmi.12306 (2013).

Kollipara, A. et al. Genetic diversity of chlamydia pecorum strains in wild Koala locations across Australia and the implications for a Recombinant C. pecorum major outer membrane protein based vaccine. Vet. Microbiol. 167, 513–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.08.009 (2013).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 676–682 (2012).

Amirshahi, A. et al. Modulation of the chlamydia trachomatis in vitro transcriptome response by the sex hormones estradiol and progesterone. BMC Microbiol. 11, 150. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-11-150 (2011). doi:1471-2180-11-150 [pii].

Quispe Calla, N. E. et al. Medroxyprogesterone acetate and levonorgestrel increase genital mucosal permeability and enhance susceptibility to genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Mucosal Immunol. 9, 1571–1583. https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2016.22 (2016).

Wyrick, P. B. Chlamydia trachomatis persistence in vitro: an overview. J. Infect. Dis. 201 (Suppl 2), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1086/652394 (2010).

Bryan, E. R. et al. Prophylactic and therapeutic vaccination protects sperm health from chlamydia muridarum-induced abnormalities. Biol. Reprod. 108, 758–777. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolre/ioad021 (2023).

Carey, A. et al. A comparison of the effects of a chlamydial vaccine administered during or after a C. muridarum urogenital infection of female mice. Vaccine 29, 6505–6513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.012 (2011).

Carey, A. J., Cunningham, K. A., Hafner, L. M., Timms, P. & Beagley, K. W. Effects of inoculating dose on the kinetics of chlamydia muridarum genital infection in female mice. Immunol. Cell. Biol. 87, 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1038/icb.2009.3 (2009).

Phillips Campbell, R., Kintner, J., Whittimore, J. & Schoborg, R. V. Chlamydia muridarum enters a viable but non-infectious state in amoxicillin-treated BALB/c mice. Microbes Infect. 14, 1177–1185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2012.07.017 (2012).

Olander, M. et al. A multi-strategy antimicrobial discovery approach reveals new ways to treat chlamydia. PLoS Biol. 23, e3003123. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3003123 (2025).

Bazroon, A. A. & Alrashidi, N. F. Bisoprolol. (2023).

Mizogami, M., Takakura, K. & Tsuchiya, H. The interactivities with lipid membranes differentially characterize selective and nonselective beta1-blockers. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 27, 829–834. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0b013e32833bf5e4 (2010).

34 Todd, P. A., Ward, A. & Gemfibrozil A review of its pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use in dyslipidaemia. Drugs 36, 314–339. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-198836030-00004 (1988).

Yao, J. et al. Type II fatty acid synthesis is essential for the replication of chlamydia trachomatis. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 22365–22376. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.584185 (2014).

Bachmann, N. L. et al. Comparative genomics of koala, cattle and sheep strains of chlamydia pecorum. BMC Genom. 15, 667. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-667 (2014).

Nunes, A. & Gomes, J. P. Evolution, phylogeny, and molecular epidemiology of chlamydia. Infect. Genet. Evol. 23, 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2014.01.029 (2014).

Liu, Y. et al. Drug repurposing for next-generation combination therapies against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Theranostics 11, 4910–4928. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.56205 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This project has been supported by the NSW Government under the NSW Koala Strategy. Microscopy was conducted using the UTS Microbial Imaging Facility.

Funding

This project has been supported by the NSW Government under the NSW Koala Strategy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WMH, VM, JW, JT, CF, HN Conception or design of the work; CF, HN, SLQ, BF acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; all authors drafted, revised and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fleming, C., Nugent, H., Quinteros, S.L. et al. A pilot study of re-purposing drugs to treat koalas with chlamydia. Sci Rep 15, 45194 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29789-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29789-3