Abstract

This study investigates the quantum dynamics of three-level Stark-shifted atomic systems under the influence of a Nonlinear Kerr Medium (NLKM), focusing on the interplay between Quantum Fisher Information (QFI), Von Neumann Entropy (VNE), and photon-mediated interactions. By analyzing the temporal evolution of QFI (quantifying parameter estimation precision) and VNE (measuring quantum entanglement (QE), we demonstrate how Kerr nonlinearity (\(\chi\)), Stark shifts (\(\beta\)), phase (\(\phi\)), and photon numbers govern system behavior. Key findings reveal that lower \(\chi\) values (e.g., \(\chi =0.3\)) induce oscillatory QFI decay and rapid VNE growth, driven by atomic motion and NLKM interactions, with QFI peaks inversely correlated to VNE dips. Higher \(\chi (\text{1,3})\) stabilizes both metrics, suppressing decoherence and entanglement fluctuations. Elevated photon numbers enhance stability by strengthening field-atom correlations, reducing oscillation amplitudes (particularly at low \(\chi\)), and mitigating quantum fluctuations. The Stark effect (SE) amplifies energy-level shifts, while phase adjustments introduce asymmetries in quantum interference. These results highlight the system’s tunability via \(\chi , \beta . \phi\), and photon density. They position it as a versatile platform for quantum metrology and information processing, where precision, entanglement stability, and photon-mediated coherence are critical. Kerr interactions suppress long-time coherence and entanglement, while when \(\chi =0\), Stark shifts can induce mild, transient quantum correlations. These dynamics are essential for controlling entanglement in cavity QED systems, especially when precise metrological performance is desired.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The interaction of a two-level atom with a single quantized mode under the rotating-wave approximation (RWA) is the Jaynes–Cummings model (JCM), capturing cyclic photon absorption–emission and atom–field energy exchange1. The JCM has been widely explored in theory and experiment, yielding core insights into atom–field dynamics2,3. Building on this, three-level atoms coupled to one- or two-mode cavities have become central in quantum optics for their richer structure and applications to quantum information and communication4,5. Cascade and related three-level configurations enable coherent-control phenomena such as electromagnetically induced transparency, state transfer, and photon blockade6,7,8,9,10. Foundational studies analyzed three-level atoms interacting with quantized fields under RWA in ideal cavities11, and generalized JCM-type frameworks treated non-resonant one- or two-mode couplings12, including multiphoton processes, field-dependent couplings, Kerr nonlinearity (NLKM), and non-correlated two-mode fields13,14,15,16,17. Further advances include modified homotopy solutions for three-level wavefunctions18, general solutions with gravity19, atomic motion in JCM settings20, QE dynamics in three-level atoms21, momentum-eigenstate interactions with NLKM22, and SU(3) Lie-algebra approaches for internal/external dynamics under an atomic gravity field23.

Quantum entanglement (QE) describes nonclassical correlations that persist over distance, allowing one subsystem to affect another instantaneously at the state level24,25,26,27. In realistic devices, open quantum structures and external conditions crucially shape QE but also induce decoherence, degrading coherence and destroying quantum information28,29,30.

To assess environmental impact on quantum information, quantum metrology estimates system parameters before and after noisy channels to optimize precision31,32. Within this framework, quantum Fisher information (QFI) provides the fundamental precision bound and a common yardstick to compare metrological strategies33. While much work has treated QFI without noise34,35, dissipative processes dominate practical settings36,37; Kraus-operator descriptions capture how dissipation modifies states and their QFI38.

The von Neumann entropy (VNE) \(S\left(\rho \right)=-\mathbf{T}\mathbf{r}(\rho \text{log}\rho )\) quantifies mixedness and, for bipartite pure states, sensitively tracks entanglement via reduced states39. In atom–field or field–mechanical platforms, VNE illuminates subsystem entanglement and coherence dynamics4, revealing decoherence, entanglement generation, and revival–collapse behavior in multipartite three-level systems with quantized radiation and optomechanics40, and serving as a diagnostic across cavity and circuit QED, including Kerr media and Stark shifts41.

The Kerr effect—an intensity-dependent refractive index—enables nonlinear phase shifts that facilitate entanglement generation and control42,43. In optomechanics, Kerr nonlinearity can enhance light–mechanics QE, underscoring its utility for state engineering34. The Stark effect (SE) shifts/splits levels under external fields and can be harnessed to control and generate entangled states44,45, e.g., dynamic SE producing photon–atom QE in driven systems46.

The Kerr nonlinearity parameter governs field self-interaction, reshaping photon-number statistics and affecting QE and decoherence; our parameter choices lie within experimentally accessible cavity-QED and photonic-crystal regimes, spanning weak to moderate nonlinearity47,48,49. The Stark-shift (SS) parameter encodes virtual-transition-induced level shifts tied to detuning and field strength; in our three-level configuration it alters effective detuning and coupling and is modeled as a diagonal atomic term, with values selected to match experimental reports50,51,52.

We therefore study QE dynamics in a three-level atom subject to SE and NLKM, with and without atomic motion, and analyze their combined impact on QFI and VNE over time. We find that SS markedly influences QFI and, in the absence of motion, more strongly modulates VNE. The paper is organized as follows: Sect. “Hamiltonian model” introduces the proposed system and QFI; Sect. “The VNE” presents VNE; Sect. “Discussions and numerical outcomes” details the system model with SE and NLKM with discussion to experimental feasibility and implementation; Sect. “Conclusions” Concludes the main resluts.

Quantum fisher information (QFI)

The Quantum Fisher Information (QFI) is a fundamental quantity in quantum estimation theory that quantifies the sensitivity of a quantum state with respect to changes in a parameter \(\theta\). It plays a central role in determining the ultimate precision bounds in parameter estimation tasks via the quantum Cramer–Rao bound53. For any unbiased estimator \(\widehat{\theta }\) of a parameter \(\theta\) encoded in a quantum state \({\rho }_{\theta }\), the variance satisfies:

where \({\mathbf{F}}_{Q}\left[{\rho }_{\theta }\right]\) is the quantum Fisher information54.

If the state is pure, \({\rho }_{\theta }={\psi }_{\theta }{\psi }_{\theta }^{*},\) the QFI is given by:

This formulation reflects the statistical distinguishability between nearby quantum states and is connected to the concept of quantum fidelity55.

For a mixed state with spectral decomposition \({\rho }_{\theta }=\sum_{k}{p}_{k}\left|{\psi }_{\theta }\rangle \langle {\psi }_{\theta }\right|,\) the QFI becomes:

Alternatively, using the symmetric logarithmic derivative (SLD) operator \({L}_{\theta }\)

When the parameter \(\theta\) is encoded through a unitary operator:

where \(G\) is the Hermitian generator, then for a pure state:

QFI quantifies how much information a quantum state carries about a parameter \(\theta .\) It is invariant under \(\theta\)-independent unitary operations and is convex:

In quantum optics and cavity QED, QFI is used to analyze entanglement, phase sensitivity, and decoherence under the influence of factors such as Kerr nonlinearity, atomic motion, and Stark shifts56.

Von neumann entropy (VNE)

The von Neumann entropy (VNE) is a central concept in quantum information theory, measuring the degree of mixedness or uncertainty in a quantum state. It serves as a quantum analog of the classical Shannon entropy and is crucial in analyzing QE, decoherence, and thermodynamic behavior in quantum systems39.

For a quantum state described by a density operator \(\rho\) acting on a Hilbert space \({\mathbf{H}}\), the VNE is defined as:

This quantity vanishes for pure states (where \({\rho }^{2}=\rho\)), and attains a maximum for maximally mixed states39.

If \(\rho\) has the spectral decomposition:

then the VNE becomes:

where \(\left\{{\lambda }_{i}\right\}\) are the eigenvalues of \(\rho\). This form is particularly useful in numerical simulations4.

In bipartite systems, VNE is often applied to the reduced density matrix to quantify QE entropy. For a composite system \(AB\) in pure state \({\rho }_{AB}\), the entanglement between subsystems \(A\) and \(B\) is given by:

where \({\rho }_{A}={\mathbf{T}\mathbf{r}}_{B}({\rho }_{AB})\) is the partial trace over subsystem \(B.\) A nonzero VNE of \({\rho }_{A}\) indicates entanglement57. In quantum optical systems, such as a three-level atom interacting with quantized cavity fields, VNE is used to study the evolution of quantum correlations and decoherence. Oscillations in entropy often reflect the phenomena of collapse and revival, indicating periodic entanglement and disentanglement40. The VNE also serves as a bridge between quantum statistical mechanics and thermodynamics. In open quantum systems, an increase in entropy typically signals a loss of coherence and flow of information to the environment. Moreover, VNE plays a role in defining thermal equilibrium states and entropy production rates in dissipative systems58.

Hamiltonian model

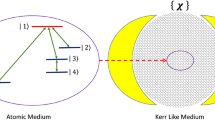

We study the system of moving 3-level atoms interacting with the coherent field in the presence of the combined effect of the SE and NLKM, specifically the cascade configuration of the system (see Fig. 1).

A three-level cascade atom (labeled A) interacting with a coherent field inside a Kerr medium. The atomic energy levels are shown in a cascade configuration, with a Stark shift \({D}_{S}.\) The system is with atomic motion environment. S could denote the state of the system. F typically refers to the coherent field inside the cavity.

Assuming the RWA, the system \({\widehat{H}}_{T}\), is given by53

where \({\widehat{H}}_{Atom-Field}\) shows the atom not interacting and field Hamiltonian, and \(\hat{H}_{I}\) represents the coupling portion. Our writing for \(\hat{H}_{Atom - Field}\) will be

where the jth level’s \({\widehat{\sigma }}_{j,j}=\left|j\rangle \langle j\right|\) represents atomic population operator. atomic population operators, we’re referring to the operators that describe transitions between different energy levels of the atom. These transitions play a crucial role in QE dynamics. The index \(j\) is now explicitly defined to label discrete atomic energy levels, ranging from \(j=1\) to \(j=N,\) where \(N\) denotes the number of atomic levels considered in the model. This formulation allows the theoretical treatment to extend beyond two-level atoms (\(N=2\)) to more complex configurations, such as three-level ladder-type (\(N=2\)) and cascade-type multilevel atoms4,51,59. The term \({\omega }_{j}\) is introduced as the transition frequency associated with the jth energy level. It quantifies the energy separation between successive atomic states, in line with standard atomic physics notations4,51,59. The variable \(\nu\) is identified as the frequency of the single-mode quantized cavity field that interacts with the atom. The coupling between the atom and the field is modeled using the bosonic creation (â†) and annihilation (\(\widehat{a}\)) operators, consistent with canonical treatments in cavity QED51,59,60,61. The integer \(N\) also serves to set the upper limit of summations in the Hamiltonian model, facilitating analysis across different atomic configurations, including ladder-, V-, and \(\Lambda - type\) systems4,62. Key physical parameters have now been formally introduced:

It depicts a two-level atom when (\(N=1,\) and the 3-, 4-, and 5-level atoms when (\(N=3, 4\) and 5.

When it comes to SE and NLKM, the \(\hat{H}_{I}\) is provided by

\(\chi\) is the parameter of NLKM, \(\beta\) is the parameter of SE. These parameters play essential roles in modulating the system’s dynamics and have been defined by prior literature on nonlinear optics and Stark-shifted cavity systems54,63,64 and the detuning parameter is described as

where \({\Delta }_{s}\) detuning between atomic transitions and cavity field. The coupling constant between the atom and the field is denoted as \(g\), while \(\Omega \left(t\right)\) represents the shape function of the cavity-field mode39. The atom’s motion is assumed to occur along the z-axis for specific considerations of interest. In the presence of atomic motion \(p\ne 0\) and in the absence of atomic motion \(p=0.\)

The velocity of the atom is represented by \(\nu ,p\) corresponds to half the number of wavelengths of the cavity mode, and \(L\) denotes the cavity’s length along the z-direction. By setting the atom’s velocity as \(\nu =\frac{gL}{\pi },\) we arrive at the following result.

To achieve maximum precision in determining the phase shift parameter, the optimal input state is considered as follows

Here, \(\left|1\rangle \right.\) and \(\left|0\rangle \right.\) represent the states of the atom, while \(\alpha\) denotes the coherent state of the input field, expressed as follows

We analyze a phase gate that operates on a single atom and applies a phase shift

The state \(\left|\Psi (0)\rangle \right.\) is derived by applying the single-atom phase gate to the initial optical state \({\left|\Psi (0)\rangle \right.}_{\text{Opt}}\)

Following the phase gate operation, the system interacts with a field. In the time-independent scenario, the wave function is described using the transformation matrix \(\widehat{U}(t)\) as expressed

The density matrix (DM) can be explicitly expressed as

In this manner, the QFI for a bipartite density operator \({\rho }_{AB}\) can be defined concerning \(\phi\), as described by64

here, \(L(\phi ,t)\) represents the quantum score, also known as the symmetric logarithmic derivative (SLD), and can be determined as described by65

In quantum estimation theory, the symmetric logarithmic derivative (SLD) \({\mathbf{L}}(\varphi )\) is defined through the relation:

where \(\rho (\phi )\) is a density matrix that depends smoothly on a parameter \(\phi\) to be estimated.

This equation is not derived from first principles but is defined to ensure the symmetric and Hermitian structure of the quantum analog to the classical Fisher Information.

In classical statistics, the Fisher information is defined as:

where \(p\left(x|\phi \right)\) is a probability distribution dependent on parameter \(\phi\).

The quantum version replaces \(p\left(x|\phi \right)\) with the density matrix \(\rho (\phi )\) and replaces the logarithmic derivative with an operator \(\mathbf{L}(\phi )\), which is chosen to satisfy the symmetric condition.

This definition ensures that the quantum Fisher information:

is real, non-negative, and reduces to the classical case when the density matrix is diagonal in a known basis.

The SLD equation is essential for evaluating the ultimate precision bounds of parameter estimation in quantum systems. It bridges classical and quantum estimation theory by generalizing the concept of the logarithmic derivative to operator form while preserving symmetry and Hermiticity.

Likewise, the VNE is described as

where \({r}_{i}\) represent eigenvalues of the atomic DM \({\rho }_{A}=-{\mathbf{T}\mathbf{r}}_{{\varvec{B}}}({\rho }_{AB})\)

We have done the numerical calculations as the system is bigger to solve analytically; we used computational languages and software for the numerical calculations. We have described clearly the Hamiltonian of the system and the interaction Hamiltonian. We also mention the state and also the formulas for QE quantifiers like QFI and VNE. To quantify QE, we construct the density matrix, and this density matrix is solved numerically. With the help of this density matrix, Eigen vectors and Eigen values of the density matrix are calculated. These eigenvectors and eigenvalues are used to calculate QFI and VNE, but this whole calculation is numerical. We have included a comprehensive explanation of the computational framework used to model the system dynamics.

The time evolution of the atom–field-mechanical system is governed by the Schrodinger equation:

where \(\hat{H}\) is the total Hamiltonian incorporating field modes, mechanical oscillator, Kerr nonlinearity, Stark shift, and atom–field coupling, including atomic motion, to numerically solve this equation, we discretize the time domain using a fixed step size \(\Delta t\) and propagate the wavefunction using the numerical method. The algorithm offers a good balance between accuracy and computational efficiency for systems with moderate stiffness and nonlinearity. The time evolution operator is constructed numerically without resorting to approximations such as the rotating-wave approximation (unless explicitly stated for comparison). Since the field resides in infinite-dimensional Fock spaces, we truncate the photon and phonon numbers to finite dimensions \({N}_{f}\) and \({N}_{m}\), respectively. Convergence tests were performed by gradually increasing these dimensions (up to \({N}_{f}={N}_{m}=20\)) until the trace of the evolved density matrix remained unified within numerical precision (\(<{10}^{-6}\) deviation). The initial atom–field state is assumed to be a direct product of pure states, typically with the atom in a ground or excited state and the fields in vacuum or coherent states. These conditions are encoded as column vectors in a composite Hilbert space. All simulations were performed using numerical languages and software on a system equipped with computer support. At each time step, we compute relevant quantum quantifiers such as QFI and VNE using standard definitions. The reduced density matrices are obtained via partial tracing over unwanted subsystems using custom matrix reshaping routines.

In our system, QFI quantifies the sensitivity of a quantum state to a slight change in an external parameter (e.g., phase or coupling strength), and serves as a powerful indicator of quantum coherence and parameter-estimation potential54. The state’s maximum susceptibility to the parameter of interest determines the upper bound of QFI in a finite-dimensional Hilbert space. For a pure state \(|\Psi \rangle\), the QFI with respect to a parameter \(\theta\) is given by:

which can attain a maximum value of

where \(\Delta H\) is the standard deviation of the generator \(H\) of \(\theta\).

For our model, this bound is constrained by the Hilbert space dimension, photon number truncation, and atom–field coupling. When entanglement is maximized and coherence is strong, QFI approaches this bound, reflecting optimal metrological utility. The minimum value of QFI is zero, which occurs when the quantum state is completely insensitive to changes in the estimated parameter. Physically, this corresponds to fully mixed or stationary states lacking coherent evolution, such as those arising from strong decoherence or saturation.

The VNE

VNE Eq. (30) is a measure of quantum mixedness and entanglement for subsystems. In our bipartite atom–field system, the VNE of the reduced density matrix captures the degree of QE between the subsystems. The lower bound of VNE is \({S}_{min}=0\), which occurs when the atom and field are in a pure, separable state. This corresponds to an initial unentangled configuration or perfect revival in systems exhibiting collapse-revival dynamics. The upper bound depends on the dimension \(d\) of the reduced subsystem and satisfies \({S}_{max}=\text{log}(d)\). In our simulations, this maximum reflects a maximally mixed reduced state, where the entanglement between atom and field is strongest and individual subsystem coherence is lost39,66.

These bounds are now explicitly discussed in the manuscript, with numerical plots contextualized relative to these theoretical extremes. The discussion gives readers a more meaningful interpretation of the entropic and metrological dynamics observed across different parameter regimes. \(\phi\) refers to the phase parameter associated with the initial quantum state or the dynamical control phase in the field-atom coupling, and \(p\) characterizes the atomic motion mode index, indicating the number of spatial half-wavelengths within the cavity field experienced by the moving atom. This arises from the time-dependent coupling term \(\text{sin}\left(\frac{p\pi \nu t}{L}\right)\). \(\chi\) is the nonlinear Kerr parameter, representing the strength of the self-phase modulation induced by a nonlinear optical medium embedded in the cavity. These parameters influence the coherence and entanglement dynamics of the system but do not correspond to environmental decoherence channels in the conventional sense. In the updated text, we have revised the use of the term environment to avoid ambiguity. The term does not refer to a thermal reservoir or open-system dissipation in this context. Instead, it refers to external, field-controllable physical influences such as cavity nonlinearity (\(\chi\)), atomic motion modulation (\(p\)), and phase offset (\(\phi\)), that shape the effective dynamics of the atom–field system without introducing irreversible decoherence. This distinction has been emphasized to avoid confusion with Lindblad-type dissipative environments or thermal reservoirs used in open quantum systems theory67,68.

The parameter \(\phi\) in our model governs the initial phase coherence of the system and is often associated with the relative phase in atomic superpositions or between quantum field modes. The choice of \(\phi =0\) represents a fully aligned phase configuration typically corresponding to constructive interference or maximum coherence between the atom and field modes. \(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\) introduces a nontrivial phase \ shift that partially breaks this coherence, offering insight into the role of quantum interference and phase sensitivity in the system. These two representative values provide a physically meaningful contrast between the maximally coherent case and a phase-shifted configuration where entanglement dynamics, QFI, and entropy may evolve differently. This approach is consistent with prior studies in phase-sensitive quantum systems54,55,60. We agree that a broader scan of \(\phi \in [\text{0,2}\pi ]\) can reveal a richer structure in the system’s dynamics, including Periodic modulations in quantum coherence and entanglement, Phase-induced suppression, or enhancement of collapse-revival patterns. Nonlinear behavior in quantum quantifiers, such as QFI and concurrence, is due to phase interference effects. We have now briefly commented on this in the discussion section, and we plan to extend this investigation in future work by treating \(\phi\) as a tunable parameter in a continuous phase sweep. The quantum dynamics are susceptible to the choice of initial state: For the atom, initializing in a superposition state vs. a pure ground or excited state can strongly affect early-time coherence and QE buildup. For the field, replacing a vacuum state with a coherent state or squeezed state alters photon number statistics and the field’s back-action on the atom. These variations can shift the position of QE peaks, modify the long-time behavior of entropy, and enhance or suppress QFI depending on how the atom–field coupling interacts with the field quantum fluctuations69,70,71. In summary, while \(\phi =0\) and \(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\) provide meaningful baselines, we acknowledge the richness introduced by broader parameter choices and have clarified these points in the revised manuscript.

Our simulations present time in dimensionless in dimensionless units \(\tau =gt\), where \(g\) is the effective atomic field coupling constant. To translate these into physical timescales, we consider a realistic value of the coupling strength for a \(\Xi -\) type atom inside a high-finesse optical cavity, typically \(g\sim 1\) Hz, consistent with experimental data for rubidium atom cavities72.

Thus, one unit of \(\tau =1\) corresponds to a physical time:

If our figures range from \(\tau =0\) to \(\tau =181\) without \(p\) and \(\tau =0\) to \(\tau =20\) with \(p=1\) which is well within the coherence times of both trapped atoms and cavity fields in modern optical or superconducting QED systems73,74,75.

The atomic motion term \(\text{sin}\left(\frac{p\pi \nu t}{L}\right)\), where \(\nu \sim {10}^{2} m/s\) and \(L\sim 1cm,\) results in modulation periods of a few microseconds accessible within experimental setups employing moving atoms or optically guided atomic beams76,77.

Similarly, when normalized, the nonlinear Kerr parameter \(\chi\) and Stark shift \(\beta\) correspond to experimentally tunable nonlinearities around \(\sim 10^{3}\) Hz, achievable through Kerr media embedded in cavity walls, AC Stark shift control via off-resonant lasers. These regimes have been realized in photonic crystal cavities, superconducting circuits, and cold-atom platforms. Specifically, the coupling strength g is assumed to be 1 Hz, consistent with experimentally accessible values in cavity QED systems. This leads to a time unit conversion of

This addition helps contextualize the timescales of quantum evolution and ensures that the results can be interpreted within real-world laboratory settings. To enhance the simulation’s physical relevance, we have now explicitly listed the parameter values used in the numerical calculations. These include realistic values such as atomic field coupling constant \(g = 1\), Kerr nonlinearity parameter \(\chi =0.3, 1, 3\) with Stark shift parameter \(\beta =0.3, 1, 3\), atomic velocity \(\upsilon = 100\,\) m/s, and Cavity length \(L = 1\,\) cm.

These values are drawn from recent experimental literature and added to the Numerical Setup subsection to make the simulation parameters transparent and experimentally grounded.

We have strengthened the manuscript by adding citations to several key experimental studies demonstrating our model components’ practical feasibility. These references validate the following elements: Strong atomic cavity coupling72, Controlled atomic motion within high-finesse optical cavities76,77, Realization of Kerr nonlinearity in photonic and circuit-QED platforms75 and long coherence times allowing microsecond-scale quantum dynamics73. These additions support the claim that the system studied is theoretically sound and experimentally viable with current quantum optics technology. Our theoretical results are within a physically meaningful and experimentally realizable framework.

Discussions and numerical outcomes

We consider both the three-level system’s static and moving cases and the presence of the coherent field. The system’s level is SE with strength \(\beta\) in the presence of NLKM. We solve the system dynamics numerically and have chosen a \(0.1\)-time step size.

A. VNE and QFI of three-level stationary stark shifted atomic systems under the influence of NLKM

QFI measures the information that an observable random variable carries about an unknown parameter, used to quantify the sensitivity of a quantum state to changes in a parameter. Subplots of Fig. 2, (a) and (b) show QFI versus time for two-phase values: \(\phi =0\) and \(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\). Each curve represents different NLKM parameter values:\(\chi =0.3\) (red), \(1\) (blue), and \(3\) (green). QFI decreases over time for all three values, with a more pronounced decrease for lower \(\chi\) values. VNE quantifies the amount of QE in a state. Subplots (c) and (d) show VNE versus time for the same phase values. Each curve represents different \(\chi\) values: \(0.3\)(red), \(1\)(blue), and \(3\)(green). VNE increases over time for all \(\chi\) values, with a more pronounced increase for lower \(\chi\) values. The SE refers to the shifting and splitting of spectral lines due to an external electric field (\(\beta =0.3\)). NLKM parameter \(\chi\) represents the strength of non-linear interaction.

Lower \(\chi\) values lead to a higher increase in VNE, indicating stronger QE, while higher \(\chi\) values result in slower growth, indicating weaker QE. QFI is crucial in quantum metrology for estimating a parameter, with higher QFI indicating more extractable information. Higher \(\chi\) values stabilize the quantum state against decoherence, slowing QFI decay over time. The SE (\(\beta =0.3\)) influences energy levels and phases, affecting sensitivity to parameter changes. VNE measures the degree of QE. Lower \(\chi\) values enhance QE, leading to a steeper increase in VNE.

Higher \(\chi\) values result in slower QE dynamics. The applied electric field (\(\beta =0.3\)) shifts energy levels and alters phase, influencing QE generation and evolution by changing energy state interactions. QFI decreases over time due to decoherence, with a faster decrease for lower \(\chi\) values and a slower decrease for higher \(\chi\) values. VNE increases over time, indicating growing QE, with a quicker increase for lower \(\chi\) values and a slower increase for higher \(\chi\) values. At \(\phi =0\), the initial phase doesn’t introduce additional complex phases, and the system’s intrinsic dynamics drive the decrease in QFI. At \(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\), additional phase shifts affect interference patterns and sensitivity. The SE and NLKM interactions shape QE and information metrics, with phase introducing complexity into the system’s evolution.

In Fig. 3, subplot (a)\(\phi =0\), \(\beta =0.3\), \(1\), and \(3\), QFI starts around \(0.98\) and decreases over time, with more significant fluctuations for higher \(\beta\). Subplot (b)\(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\): Similar to (a) but with a slightly more pronounced QFI decrease. Subplot (c)\(\phi =0\): VNE fluctuates around \(0.1\), with larger fluctuations for higher \(\beta\). Subplot (d): Similar to (c) at \(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\) but with slightly more pronounced volatility. The SE leads to significant fluctuations in both QFI and VNE, indicating its impact on sensitivity and QE dynamics. This analysis helps us understand how external fields and nonlinear effects influence precision and QE in quantum systems. QE, where particles remain connected regardless of distance, is vital for quantum computing and cryptography. VNE measures QE, with higher values indicating more QE. Nonlinearities and external fields cause QE to fluctuate, often correlating with QFI changes. Both QFI and VNE are linked to QE. High QFI usually corresponds to high VNE. The Kerr nonlinearity and SE modulate QE, causing fluctuations in both measures. Understanding these relationships optimizes quantum systems for quantum metrology and information processing. Graphs show QFI and VNE varying over time and with different \(\beta\) values. Higher \(\beta\) results in more significant QFI and VNE changes, indicating stronger external fields enhance QE and sensitivity. Utilizing highly entangled states with high QFI allows precision measurements beyond classical limits. Analyzing QE and sensitivity changes with external parameters tailors quantum systems for specific tasks.

This study investigates the influence of the Stark shift parameter \(\beta\) on two key quantum information quantifiers, QFI and VNE, for a cascade-type three-level atom interacting with a quantized radiation field. Two scenarios are examined: one without atomic motion and another incorporating time-dependent nuclear motion in the coupling strength. Surprisingly, results show that varying \(\beta\) from \(0.3\) to \(3\) has a negligible impact on both QFI and VNE in both cases. A physical explanation rooted in entanglement theory is presented.

Without atomic motion, the atom–field interaction is static and governed by field mode coupling. The Stark shift parameter \(\beta\) is introduced to shift the energy levels of the excited atomic states. However, it is observed from the QFI and VNE plots that all curves corresponding to \(\beta =0.3, 1, 3\) overlap perfectly. The Stark shift modifies only the energy level spacing, not the coupling structure between states. The atom–field resonance is preserved, and small shifts do not disrupt the coherent exchange of excitations. QFI and VNE, as global quantities, are sensitive to state distinguishability and mixedness. If the Stark shift does not change the spectrum of the reduced density matrix, these quantities remain invariant, highlighting their broad applicability in quantum systems.

In cascade three-level atomic systems interacting with quantized fields, both in static and motional regimes, the Stark shift parameter \(\beta\) has negligible influence on QFI and VNE within the moderate range tested. This result is physically consistent with the fact that Stark shifts alter level energies but not the quantum coherence structure driving entanglement or parameter sensitivity Fig. 4.

B. VNE and QFI of three- level moving stark shifted atomic systems under the influence of NLKM

This graph depicts the behavior of QFI and VNE as a function of time under different conditions of the Kerr nonlinearity parameter \(\chi =0.3, 1\) and \(3\) the phase \(\phi =0, \frac{\pi }{4}\). The key features are influenced by atomic motion, the SE parameter \(\beta =0.3\), and QE in NLKM. (a) QFI for \(\phi =0\) and (b) QFI for \(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\): Higher QFI values imply better precision. For \(\chi =0.3\) (red line), QFI shows periodic oscillations with sharp dips, indicating significant influence of the NLKM and atomic motion. For \(\chi =1\) (blue line) and \(\chi =3\) (green line), QFI stabilizes at high values, reflecting lesser sensitivity to the atomic motion or nonlinear effects. (c) VNE for \(\phi =0\) and (d) VNE for \(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\): VNE quantifies QE, with higher values indicating stronger QE. The red line (\(\chi =0.3\)) exhibits pronounced oscillations in VNE, showing substantial variations in QE over time, corresponding to periodic coupling between subsystems mediated by the NLKM and atomic motion. For \(\chi =1\) and \(\chi =3\), VNE remains relatively low, indicating weaker QE.

The oscillatory behavior in QFI and VNE, especially for \(\chi =0.3\), indicates dynamic interactions between atomic motion and the NLKM. This motion induces periodic QE and precision QFI modulations, particularly at low \(\chi\). QE plays a pivotal role in enhancing QFI. Peaks in QFI often align with dips in VNE, suggesting a trade-off between the precision of parameter estimation.

In Fig. 5, the NLKM \(\chi =0.3\) introduces a non-linear term into the Hamiltonian, meaning that the interaction strength between the atoms depends on their quantum state. This non-linearity leads to state-dependent phase shifts that influence the atomic dynamics. Imagine that the atomic system is in a cavity where the non-linearity of the medium bends the “optical paths” of the atoms in a way that depends on their quantum states. This bending causes oscillatory behavior in the quantum coherence and QE. The oscillations in QFI and VNE emerge from the interplay between the NLKM-induced non-linearity and the periodic atomic motion. High QFI values (> 0.96): The system is coherent mainly, meaning the quantum state retains well-defined phase relationships. Periodic Dips: As the atomic motion evolves, interactions in the Kerr medium and external fields periodically modulate the state coherence, causing temporary reductions in QFI. Phase Dependence (\(\phi =0\) vs.\(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\)): Changing \(\phi\) adjusts the interference pattern of the atomic wave functions, slightly shifting the oscillations. For the zero value of QE, the system is predominantly in a pure quantum state, suggesting minimal interaction between subsystems.

The spikes in VNE correspond to moments when the atomic motion and non-linear interactions temporarily increase QE between different system parts (e.g., between atomic internal states or field modes in the Kerr medium). The SE \(\beta =0.3, 1\) and \(3\) shifts atomic energy levels due to an external electric field. The parameter \(\beta\) quantifies the strength of this shift. Physically, \(\beta\) modifies the system’s time evolution by introducing energy level differences. Small \(\beta =0.3\), the energy shifts are small, so the atomic motion and coherence oscillations are less disturbed. This results in smoother dynamics, as seen in the red curves. Large \(\beta =3\) corresponds to higher the green curves reflect these more pronounced dynamics. The atomic system evolves under the competing influences of the Kerr medium’s non-linearity and the SE. Physically, this is akin to a pendulum swinging in a medium that changes its properties depending on the pendulum’s state.

The high QFI indicates the pendulum’s motion remains regular and predictable, making the system highly sensitive to phase or energy shifts. Small spikes in VNE represent transient moments when the pendulum’s motion briefly entangles with other degrees of freedom, such as the medium or another pendulum. Changing \(\phi\) adjusts the initial conditions of the system’s dynamics, similar to starting a pendulum swing from different angles. In the graphs at \(\phi =0\), the oscillations appear slightly simpler and more symmetric at \(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\); a phase offset introduces subtle asymmetries or shifts in the QFI and VNE oscillation patterns. Atomic motion: Drives periodic coherence and QE dynamics. NLKM medium (\(\chi =0.3\)) introduces non-linearity, leading to periodic modulation of quantum properties. The SE \(\beta\) alters energy levels, influencing the amplitude and frequency of the oscillations. QFI shows high coherence and is suitable for quantum metrology. VNE: Shows minimal QE, indicating a predominantly pure state with transient increases in QE. This interplay demonstrates a quantum system where coherence dominates, with QE emerging briefly during atomic motion cycles. The physical system is highly controllable via \(\beta\), \(\chi ,\) and \(\phi ,\) making it ideal for precision quantum sensing or fundamental quantum dynamics studies.

When atomic motion is introduced, the interaction term becomes time-dependent

This leads to periodic modulation of coupling, giving rise to collapse and revival phenomena in both QFI and VNE. However, even in this dynamic regime, the variation of \(\beta\) does not produce observable differences in the quantifiers. Atomic motion dominates the dynamics, overshadowing any static shifts induced by \(\beta\). The Stark shift terms act diagonally and contribute only to global phase factors, which do not affect the reduced density matrix’s eigenvalues. Since entanglement and sensitivity are governed by coherent exchange mechanisms, which refer to the exchange of quantum information in a consistent and predictable manner, and these mechanisms remain unaffected, QFI and VNE do not change. In cascade three-level atomic systems interacting with quantized fields, both in static and motional regimes, the Stark shift parameter \(\beta\) has negligible influence on QFI and VNE within the moderate range tested. This result is physically consistent with the fact that Stark shifts alter level energies but not the quantum coherence structure driving entanglement or parameter sensitivity.

C. VNE and QFI of three- level moving stark shifted atomic systems under the influence of NLKM with increasing photon numbers

The Fig. 6, a visual representation of the temporal evolution of Quantum Fisher Information (QFI) and Von Neumann Entropy (VNE) under varying non-Kerr medium parameters (\(\chi =\text{0.3,1},3\)) and a SE parameter \(\beta =0.3\), is a key element in understanding the dynamics of the system. It provides a clear illustration of the relationships being discussed. \(\alpha =12\) is a coherent state parameter describing the number of photons (\(\alpha ={\left|n\right|}^{2}\)). The top panels illustrate QFI for phase values \(\phi =0\) and \(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\), while the bottom panels depict VNE under identical conditions. At \(\chi =0.3\) (red curve), pronounced oscillations in QFI reflect dynamic fluctuations in quantum sensitivity, persisting over extended periods and indicating a non-equilibrium state. As \(\chi\) increases to \(1\) (blue) and \(3\) (green), QFI stabilizes, suggesting that stronger nonlinear Kerr interactions suppress oscillations and enhance resistance to decoherence, thereby promoting robust quantum states for precision metrology. Similarly, VNE, a measure of QE, exhibits marked oscillations at \(\chi =0.3\), signaling intermittent coherence loss and unstable QE. Higher \(\chi\) values (\(1\) and 3) stabilize VNE, demonstrating that enhanced Kerr nonlinearity mitigates QE fluctuations, preserving coherence for quantum information tasks. Elevated photon counts amplify QE by intensifying field-atom interactions, strengthening quantum correlations. This results in stabilized QFI and VNE, with reduced oscillation amplitudes, particularly at low \(\chi =0.3\).

Thus, high photon numbers alleviate quantum fluctuations, bolstering system reliability. The Kerr effect nonlinearity suppresses oscillations and stabilizes coherence, while the SE induces minor energy shifts that modulate QFI and VNE without significant destabilization. Their synergy governs the system’s quantum correlation dynamics, with Kerr’s dominance ensuring steady states. Stabilized VNE (high QE) correlates with steady QFI (enhanced sensitivity). Low \(\chi\) regimes exhibit erratic fluctuations in both, indicating fragile quantum states. Conversely, elevated \(\chi\) fosters resilience, maintaining QE and sensitivity critical for quantum technologies requiring consistent performance. Increasing \(\chi\) and photon numbers enhance system stability by curbing fluctuations. At the same time, the interplay of Kerr and SEs fine-tune quantum behavior, underscoring their roles in advancing quantum sensing and information applications.

The Fig. 7 illustrates the behavior of QFI and VNE over time for different values of the NLKM parameter \(\chi =(\text{0.3,1},3)\) with the SE (Self-Interaction Energy) considered at \(\beta =0.3,\) \(\alpha =12\) is a coherent state parameter describing the number of photons,\(\alpha ={\left|n\right|}^{2}\). The influence of atomic motion is also considered, contributing to the observed oscillations and fluctuations in the plotted curves. For the QFI plots (top row), the red curve (\(\chi =0.3\)) exhibits strong oscillations, indicating pronounced fluctuations in quantum sensitivity. These oscillations suggest that, at lower \(\chi\) values, the quantum state is highly susceptible to changes in external parameters. For higher values of \(\chi\) (blue and green curves corresponding to \(\chi =1\) and \(\chi =3\)), QFI stabilizes, implying that the system becomes more robust against fluctuations. Introducing a phase shift (\(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\)) does not significantly alter the overall behavior, as similar trends are observed for both cases. In the VNE plots (bottom row), which measure QE, the red curve (\(\chi =0.3\)) again exhibits significant fluctuations. These oscillations indicate a dynamic QE evolution attributed to atomic motion affecting the quantum state. As \(\chi\) increases, the QE fluctuations are suppressed, resulting in more stable quantum correlations. The blue and green curves corresponding to \(\chi =1\) and \(\chi =3\) display much more minor variations, indicating that higher nonlinearity in the medium helps maintain stable QE over time. Atomic motion plays a crucial role in the observed behavior. It introduces additional fluctuations in the quantum state, which are more prominent at lower \(\chi\) values. This is evident in the strong oscillatory nature of the red curve for both QFI and VNE.

However, as \(\chi\) increases, the system exhibits greater resistance to these fluctuations, leading to smoother and more predictable behavior. The presence of large photon numbers has a stabilizing effect on QE. When the number of photons in the field is high, the interaction strength between the atomic system and the field increases, leading to stronger correlations. This results in an enhancement of QFI and VNE, making the system more suitable for quantum applications such as precision measurements and quantum communication. Large photon numbers also reduce the amplitude of oscillations, particularly for \(\chi =0.3,\) thereby mitigating the instability observed at lower values of \(\chi\). The NLKM and SEs play significant roles in shaping QFI and VNE. The NLKM introduces nonlinearity into the system, which helps suppress QE fluctuations and stabilizes quantum coherence. As \(\chi\) increases, both QFI and VNE become more stable, highlighting the role of Kerr nonlinearity in preserving quantum information. Conversely, the SE shifts the energy levels of the atomic system, leading to modifications in the QE dynamics.

At \(\beta =0.3,\) these modifications are moderate but contribute to the observed oscillatory behavior, particularly for lower \(\chi\) values. The relationship between QFI, VNE, and QE is evident in the figure. As indicated by increased VNE, a higher degree of QE corresponds to greater quantum sensitivity, reflected in QFI. When \(\chi\) is small, QFI and VNE experience strong oscillations, indicating a fragile quantum state susceptible to decoherence. As \(\chi\) increases, both quantities stabilize, suggesting that higher nonlinearity in the medium preserves QE and ensures robustness in the quantum system. This stability is essential for practical quantum technologies, where maintaining QE over time is critical for reliable performance.

This Fig. 8 displays the behavior of Quantum Fisher Information (QFI) as a function of time t, under varying values of the Kerr nonlinearity parameter \(\chi\) and Stark shift parameter \(\beta\), in the absence of atomic motion (\(p = 0\)). The figure is organized into four panels. The upper row (a) and (b) investigates the effect of different Kerr nonlinearities \(\chi =\text{0.3,1},3\) on QFI, keeping \(\beta = 0\). The lower row (c) and (d) explores the influence of Stark shift values \(\beta =\text{0.3,1},3\) on QFI, with Kerr nonlinearity switched off (\(\chi =0\)); both rows compare the impact under two-phase values: \(\phi =0\) (left column) and \(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\)) (right column).

QFI for a three-level atom interacting with a cavity field in the absence of atomic motion (p = 0). The top panels (a) and (b) display the effect of Kerr nonlinearity (\(\chi =\text{0.3,1},3\)) with Stark shift = 0, for phase values \(\phi =0\) and \(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\), respectively. The bottom panels (c) and (d) show the impact of Stark shift (\(\beta =\text{0.3,1},3\)) with no Kerr nonlinearity (\(\chi =0\)) under the same phase conditions.

In the upper panels (a) and (b), with \(\beta =0\), we observe that increasing \(\chi\) reduces the QFI over time. Specifically, for \(\chi =0.3,\) the QFI exhibits strong oscillations with relatively high amplitude, indicating significant temporal variation in the system’s sensitivity to parameter estimation. As \(\chi\) increases to \(1\) and then 3, the oscillations diminish, and the QFI decays more smoothly, approaching a lower steady-state value. This behavior reflects a suppression of quantum coherence (the property of a quantum system to be in a superposition of states) and parameter sensitivity with increasing nonlinearity. The degradation in QFI implies reduced utility for quantum metrology, suggesting a weakening of quantum entanglement between subsystems since high QFI is usually associated with highly entangled or nonclassically correlated states.

In the lower panels (c) and (d), where \(\chi =0,\) the Stark shift \(\beta\) instead modulates the QFI; here, the QFI values are significantly lower than in the upper row, showing peak values that do not exceed \(0.6\), and decaying toward zero with time. This suppression is more pronounced for lower values of \(\beta\), whereas higher \(\beta\) values seem to sustain moderately higher QFI oscillations over longer times. These oscillations are indicative of dynamic QE generation and decay. However, the overall reduced QFI levels imply a system more prone to classicality, where QE is transient and less robust. Comparing \(\phi =0\) with \(\phi =\frac{\pi }{4}\), the latter appears to induce subtle changes in the QFI envelope and modulation frequency, but the overall trends remain consistent: Kerr nonlinearity degrades QFI in the top panels, and Stark shift variations yield low-amplitude but discernible oscillatory behavior in the bottom panels. Phase \(\phi\) thus introduces a relative coherence factor, influencing the interference pattern between atomic and field components, which indirectly affects QE dynamics but does not qualitatively change the system’s sensitivity in the absence of atomic motion.

In conclusion, this figure demonstrates that in the absence of atomic motion, Kerr nonlinearity and Stark shift modulate QFI in distinct ways: Kerr interactions suppress long-time coherence and entanglement, while Stark shifts can induce mild, transient quantum correlations. These dynamics are critical for controlling entanglement in cavity QED systems, especially when precise metrological performance is desired.

Experimental feasibility and implementation

In traditional optical cavity QED systems, Fabry-Pérot cavities with mirror separations of a few millimeters (\(1 - 5\)\(mm\)) have been successfully used to trap single atoms and enable strong atom–field coupling51,73. Within these cavities: Stationary atoms can be localized using optical dipole traps or conveyor-belt lattices inside the cavity mode volume. Atomic motion can be introduced and controlled by releasing atoms from a magneto-optical trap and allowing them to freely traverse the cavity mode region with a controlled velocity \(\nu \sim {10}^{2}\) m/s. The mode profile of the cavity field (e.g.\(\text{sin}\left(\frac{p\pi \nu t}{L}\right)\)) is then sampled dynamically by the moving atom, producing the time-dependent coupling used in our model. The Stark shift is routinely implemented in cavity QED experiments by exposing the atom to a far-detuned auxiliary laser field, which induces an AC Stark shift proportional to the local field intensity78,79,80. This allows Dynamic control of \(\beta\) via laser intensity or detuning site-dependent tuning in lattice-confined or standing-wave-modulated systems. In circuit QED, the Stark shift analog arises from frequency dressing of superconducting qubits through off-resonant microwave fields81, enabling tunable detuning effects analogous to optical Stark shifts. A Kerr medium is introduced in optical QED systems using Nonlinear crystals such as \({\chi }^{(3)}-\) media embedded into the cavity, atomic ensembles in EIT configurations with strong nonlinear response82. In circuit QED, Kerr-type interactions are easily achieved using Josephson junctions or transmon qubits coupled to resonators. These provide a natural platform to realize Intrinsic Kerr nonlinearities, Tunable self-phase modulation using drive amplitude, and qubit-cavity detuning83. The complete model combining Stark shift, Kerr nonlinearity, and motional degrees of freedom can thus be engineered modularly. In optical QED by combining moving atoms in a cavity with controlled Stark fields and a nonlinear medium. In circuit QED, coupling superconducting artificial atoms (qubits) to nonlinear resonators with external drive fields simulating motion and phase shift dynamics. Kerr nonlinearity and Stark shift modulate QFI in distinct ways: when \(\beta =0\), Kerr interactions suppress long-time coherence and entanglement, while when \(\chi =0,\) Stark shifts can induce mild, transient quantum correlations. These dynamics are critical for controlling entanglement in cavity QED systems, especially when precise metrological performance is desired.

Conclusions

The dynamics of QFI and VNE in a three-level Stark-shifted atomic system under NLKM interactions demonstrate a delicate balance between quantum coherence and QE, governed by Kerr nonlinearity (\(\chi\)), Stark shifts (\(\beta\)), phase (\(\varphi\)), and photon numbers. Lower \(\chi\) values (\(0.3\)) lead to oscillatory QFI decay and rapid VNE growth, reflecting transient QE and sensitivity to atomic motion, while higher for \(\chi =\text{1,3}\) stabilizes both metrics, enhancing resistance to decoherence. Elevated photon numbers further amplify this stability: increased field-atom interactions strengthen quantum correlations, suppress oscillation amplitudes (notably at \(\chi =0.3\)), and mitigate quantum fluctuations, bolstering system reliability.

The SE sharpens oscillations through energy-level shifts, and phase adjustments modulate interference pathways. Critically, the inverse relationship between QFI peaks and VNE minima persists, highlighting a precision-entanglement trade-off. The synergy between Kerr nonlinearity, Stark shifts, and photon density underscores the system’s tunability. High photon counts and strong \(\chi\) not only enable robust coherence but also preserve the key features necessary for quantum sensing and communication, instilling a sense of potential for robust applications.

Conversely, low \(\chi\) regimes with transient QE may offer significant benefits for dynamic protocols requiring adaptive control. Future studies should explore photon statistics (e.g., squeezed or coherent states) and their interplay with \(\chi\) and \(\beta\). This work advances strategies for optimizing quantum technologies by leveraging nonlinearity, external fields, and photon-mediated interactions to engineer stable, high-performance systems, highlighting the adaptability and versatility of the system.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shore, B. W. & Knight, P. L. The jaynes-cummings model. J. Mod. Opt. 40, 1195–1238 (1993).

Alqannas, H. S. & Abdel-Khalek, S. Nonclassical properties and field entropy squeezing of the dissipative two-photon JCM under Kerr-like medium based on dispersive approximation. Opt. Laser Technol. 111, 523–529 (2019).

Rempe, G., Walther, H. & Klein, N. Observation of quantum collapse and revival in a one-atom maser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 353 (1987).

Scully, M. O. & Zubairy, M. S. Quantum Optics. Cambridge University Press (1997).

Fleischhauer, M., Imamoglu, A. & Marangos, J. P. Electromagnetically induced transparency: Optics in coherent media. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 633–673 (2005).

Agarwal, G. S. Quantum Optics. Cambridge University Press (2012).

Kiffner, M., Macovei, M., Evers, J. & Keitel, C. H. Vacuum-induced processes in multilevel atoms. Prog. Opt. 55, 85–197 (2010).

Scully, M. O. Enhancement of the index of refraction via quantum coherence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 1855 (1991).

Zhou, P. & Swain, S. Nonclassical effects in a three-level atom interacting with a two-mode cavity field. Phys. Rev. A 54, 4453 (1996).

Tanaś, R. & Kielich, S. Nonclassical effects in the radiation from three-level atoms. Opt. Commun. 50, 26–30 (1984).

Yoo, H.-I. & Eberly, J. H. Dynamical theory of an atom with two or three levels interacting with quantized cavity fields. Phys. Rep. 118, 239–337 (1985).

Li, X.-S. & Lin, D. L. Nonresonant interaction of a three-level atom with cavity fields. I. General formalism and level occupation probabilities. Phys. Rev. A 36, 5209 (1987).

Abdel-Hafez, A. M., Obada, A. S. F. & Ahmad, M. M. A. N-level atom and (N–1) modes generalized models and multiphons. Physica A 144, 530–560 (1987).

Abdel-Hafez, A. M., Obada, A.-S.F. & Ahmad, M. M. A. N-level atom and (N–1) modes: An exactly solvable model with detuning and multiphotons. J. Phys. A 20, L359 (1987).

Abdel-Hafez, A. M., Abu-Sitta, A. M. M. & Obada, A.-S.F. A generalized Jaynes-Cummings model for the N-level atom and (N–1) modes. Physica A 156, 689–712 (1989).

Abdel-Aty, M. Entanglement degree of a three-level atom interacting with pair-coherent states with a nonlinear medium. Laser Phys. 11, 871–878 (2001).

Obada, A. S. F., Hanoura, S. A. & Eied, A. A. Entanglement for a general formalism of a three-level atom in a Λ-configuration interacting nonlinearly with a non-correlated two-mode field. Laser Phys. 23, 055201 (2013).

Abdel Wahab, N. H. & Salah, A. A novel solution procedure for a three-level atom interacting with one-mode cavity field via modified homotopy analysis method. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 130, 92 (2015).

Abd El-Wahab, N. H. & Salah, A. The influence of the classical homogenous gravitational field on interaction of a three-level atom with a single mode cavity field. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 29, 1550175 (2015).

Liu, J.-R. & Wang, Y.-Z. Velocity-selective population and quantum collapse-revival phenomena of the atomic motion for a motion-quantized Raman-coupled Jaynes-Cummings model. Phys. Rev. A 54, 2444 (1996).

Faghihi, M. J., Tavassoly, M. K. & Hatami, M. Dynamics of QE of a three-level atom in motion interacting with two coupled modes including parametric down conversion. Physica A 407, 100–109 (2014).

Zait, R. A. & Abd El-Wahab, N. H. Nonresonant interaction between a three-level atom with a momentum eigenstate and a one-mode cavity field in a Kerr-like medium. J. Phys. B 35, 3701 (2002).

Osman, M. S. & Abdel-Gawad, H. I. Multi-wave solutions of the (2+1)-dimensional Nizhnik-Novikov-Veselov equations with variable coefficients. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 130, 1–11 (2015).

Bartlett, R. Alternating current and superconductivity QE of waves replaces nuclear fusion as the power source in stars. SSRN 4556339 https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13100.44166 (2023).

Feng, T., Song, Z., Wu, T., Lu, X. Li, L. QE source model pumped by low-power laser diode. In Infrared, Millimeter, Terahertz Waves and Applications (IMT2022) 12565, 362–370 (SPIE, 2023).

Sun, W.-Y., Wang, D., Fang, B.-L. & Ye, L. Quantum dynamics characteristic and the flow of information for an open quantum system under relativistic motion. Laser Phys. Lett. 15, 035203 (2018).

Goradia, S. G. The quantum theory of QE and Alzheimer’s. J. Alzheimers Neurodegener. Dis. 5, 01–03 (2019).

Little, D. Entangling the social: Comments on Alexander Wendt, quantum mind and social science. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 48, 167–176 (2018).

Bhattacharyya, S., Das, A., Banerjee, A. Chakrabarti, A. Comparative study of noises over quantum key distribution protocol. In Data Management, Analytics Innovation, 759–782 (Springer, 2023).

Lee, J. Y., You, Y.-Z. & Xu, C. Symmetry protected topological phases under decoherence. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.16323 (2022).

Khalid, U., Jeong, Y. & Shin, H. Measurement-based quantum correlation in mixed-state quantum metrology. Quantum Inf. Process. 17, 1–12 (2018).

Triggiani, D., Facchi, P. & Tamma, V. The role of auxiliary stages in gaussian quantum metrology. Photonics 9, 345 (2022).

Apellaniz, I., Kleinmann, M., Gühne, O. & Tóth, G. Optimal witnessing of the quantum fisher information with few measurements. Phys. Rev. A 95, 032330 (2017).

Beckey, J. L., Cerezo, M., Sone, A. & Coles, P. J. Variational quantum algorithm for estimating the quantum fisher information. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 013083 (2022).

Rath, A., Branciard, C., Minguzzi, A. & Vermersch, B. Quantum fisher information from randomized measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 260501 (2021).

Hu, L.-Y., Rao, Z.-M. & Kuang, Q.-Q. Evolution of quantum states via weyl expansion in dissipative channel. Chin. Phys. B 28, 084206 (2019).

Naikoo, J., Banerjee, S. & Srikanth, R. Quantumness of channels. Quantum Inf. Process. 20, 1–11 (2021).

Falaye, B. J. et al. Investigating quantum metrology in noisy channels. Sci. Rep. 7, 16622 (2017).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press (2010).

Phoenix, S. J. D. & Knight, P. L. Establishment of an entangled atom-field state in the Jaynes-Cummings model. Phys. Rev. A 38, 4173 (1988).

Joshi, A. & Puri, R. R. Quantum entropy and statistical properties of the radiation field in a nonlinear Jaynes-Cummings model. Phys. Rev. A 44, 2102 (1991).

Xiong, W., Jin, D.-Y., Qiu, Y., Lam, C.-H. & You, J. Q. Cross-Kerr effect on an optomechanical system. Phys. Rev. A 93, 023844 (2016).

Chen, J., Fan, X.-G., Xiong, W., Wang, D. & Ye, L. Nonreciprocal QE in cavity-magnon optomechanics. Phys. Rev. B 108, 024105 (2023).

Zhang, D. & Qiang, Z. Enhancing stationary optomechanical QE with the Kerr medium. Chin. Phys. B 22, 064206 (2013).

Pagel, D., Alvermann, A. & Fehske, H. Dynamic SE, light emission, and QE generation in a laser-driven quantum optical system. arXiv:1609.03788 (2016).

Anwar, S. J., Ramzan, M. & Khan, M. K. Effect of Stark- and Kerr-like medium on the QE dynamics of two three-level atomic systems. Quantum Inf. Process. 18, 192 (2019).

Agarwal, G. S. Quantum Optics. Cambridge University Press (2013).

Boyd, R. W. Nonlinear Optics. Academic Press (2020).

Milonni, P. W. & Eberly, J. H. Laser Physics. Wiley (2010).

Cohen-Tannoudji, C., Dupont-Roc, J. & Grynberg, G. Atom-Photon Interactions. Wiley (1992).

Haroche, S. & Raimond, J. M. Exploring the Quantum: Atoms, Cavities, and Photons. Oxford University Press (2006).

Shore, B. W. The Theory of Coherent Atomic Excitation. Wiley (1990).

Abdel-Khalek, S. Quantum fisher information for moving three-level atom. Quantum Inf. Process. 12, 3761 (2013).

Paris, M. G. A. Quantum estimation for quantum technology. Int. J. Quantum Inf. 7(Supp01), 125–137 (2009).

Braunstein, S. L. & Caves, C. M. Statistical distance and the geometry of quantum states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 3439 (1994).

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Quantum metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 010401 (2006).

Bennett, C. H., DiVincenzo, D. P., Smolin, J. A. & Wootters, W. K. Mixed-state entanglement and quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. A 54, 3824 (1996).

Breuer, H. P. & Petruccione, F. The Theory of Open Quantum Systems. Oxford University Press (2002).

Shore, B. W. Manipulating Quantum Structures Using Laser Pulses. Cambridge University Press (2011).

Gerry, C. C. & Knight, P. L. Introductory Quantum Optics. Cambridge University Press (2005).

Imamoğlu, A., Schmidt, H., Woods, G. & Deutsch, M. Strongly interacting photons in a nonlinear cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 1467 (1997).

Tanas, R. & Kielich, S. Quantum statistics of a nonlinear optical coupler. Opt. Acta 30, 1241–1255 (1983).

Chaturvedi, S. & Srinivasan, V. Stark effect and atomic energy shifts in the Λ system. Phys. Rev. A 21, 1809 (1980).

Lu, X., Wang, X. & Sun, C.-P. Quantum Fisher information flow and non-Markovian processes of open systems. Phys. Rev. A 82, 042103 (2010).

Barndorff-Nielsen, O. E., Gill, R. D. & Jupp, P. E. On quantum statistical inference. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 65, 775–816 (2003).

Vedral, V. The role of relative entropy in quantum information theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 197–234 (2002).

Breuer, H.-P. & Petruccione, F. The Theory of Open Quantum Systems. Oxford University Press (2002).

Rivas, Á. & Huelga, S. F. Open Quantum Systems: An Introduction. Springer (2012).

Zhang, W.-M., Feng, D. H. & Gilmore, R. Coherent states: Theory and some applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 62, 867 (1990).

Mølmer, K. Optical coherence: A convenient fiction. Phys. Rev. A 55, 3195 (1997).

Walls, D. F. & Milburn, G. J. Quantum information. In Quantum Optics 307–346 (Berlin, Heidelberg, 2008).

Hood, C. J., Lynn, T. W., Doherty, A. C., Parkins, A. S. & Kimble, H. J. The atom-cavity microscope: Single atoms bound in orbit by single photons. Science 287, 1447–1453 (2000).

Reiserer, A. & Rempe, G. Cavity-based quantum networks with single atoms and optical photons. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 1379 (2015).

Walther, H., Varcoe, B. T. H., Englert, B.-G. & Becker, T. Cavity quantum electrodynamics. Rep. Prog. Phys. 69, 1325 (2006).

Devoret, M. H. & Schoelkopf, R. J. Superconducting circuits for quantum information: An outlook. Science 339, 1169–1174 (2013).

Kuhr, S. et al. Deterministic delivery of a single atom. Science 293, 278–280 (2001).

Nussmann, S. et al. Submicron positioning of single atoms in a microcavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 173602 (2005).

Haroche, S. & Raimond, J.-M. Exploring the Quantum: Atoms, Cavities, and Photons. Oxford University Press (2006).

Ye, J., Vernooy, D. W. & Kimble, H. J. Trapping of single atoms in cavity QED. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 4987 (1999).

Boozer, A. D., Boca, A., Miller, R., Northup, T. E. & Kimble, H. J. Cooling to the ground state of axial motion for one atom strongly coupled to an optical cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 083602 (2006).

Koch, J. et al. Charge-insensitive qubit design derived from the Cooper pair box. Phys. Rev. A 76, 042319 (2007).

Schmidt, H. & Imamoglu, A. Giant Kerr nonlinearities obtained by electromagnetically induced transparency. Opt. Lett. 21, 1936–1938 (1996).

Kirchmair, G. et al. Observation of quantum state collapse and revival due to the single-photon Kerr effect. Nature 495, 205–209 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2024-08).

Funding

This research was funded by Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia (TU-DSPP-2024–08).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Jamal Anwar: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft. M. Ibrahim: Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – Review & Editing. M. Khalid Khan: Data Curation, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing. S. Abdel-Khalek: Theoretical Framework, Supervision, Programming, Writing – Review & Editing. Haifa S. Alqannas: Resources,Writing – Review & Editing. Mohamed Ridza Wahiddin: Supervision, Methodology, Writing – Final Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anwar, S.J., Ibrahim, M., Khan, M.K. et al. Quantum coherence in three-level systems under the combined effect of stark effect and non-linear Kerr medium. Sci Rep 16, 453 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29866-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29866-7