Abstract

Salt is essential for life, though excessive intake disrupts the balance of body fluids in multicellular organisms like humans. We wondered what happens when body fluids circulate in a single cell. To address this question, we studied the effects of excessive salt on the network-forming giant cell of the slime mold Physarum polycephalum. We analyse the phenotypic and transcriptomic responses during exposure of plasmodia to various concentrations of sodium chloride. Morphological observations revealed alterations in the tubular network architecture, including reduced network vein diameter and changes in typical peristaltic contraction frequency. Transcriptomic analysis identified more than 2000 differentially expressed genes, with a significant upregulation of ion transporters, membrane proteins and stress-related pathways, alongside with a downregulation of genes involved in metabolic degradation. These findings suggest that P. polycephalum mitigates salt stress by regulating ion homeostasis, adjusting cytoskeletal dynamics and modulating gene expression related to cellular defence mechanisms. Possible alterations of the secreted slime coat and corresponding mechanical feedback mechanisms are discussed. The insights into the salt stress responses of P. polycephalum help to understand the salt response of a protist that is evolutionary basal to animals and fungi.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stress represents an unfavorable condition of life which deviates from an energetically optimal state and redirects energetic resources from growth to a stress response. Since environmental stress can be repeatedly encountered throughout the life cycle, organisms escape actively or evolved fine-tuned responses or even some sort of habituation to stress. These responses may range from immediate physicochemical adjustments to more complex regulatory reactions, including shifts in gene expression patterns. Among the various factors, one of the most common inducers of stress responses in terrestrial organisms is osmotic stress, caused by low water potential during desiccation or by exposure to high ionic strength such as exerted by solutions of salts. Responses to osmotic stress have been studied in many multicellular and unicellular eukaryotes, where it includes common signalling responses1. Typically, the phenotypes of the studied organisms remain – at least with moderate levels of osmotic stress – largely shape-invariant. Here we study a group of unicellular protists known as plasmodial slime moulds (Myxogastria), which can vary in their phenotypes depending on the environmental conditions2.

Typically, the model species Physarum polycephalum develops a macroscopic and multinucleate plasmodium. The resulting giant cell develops a network of interconnected vein-like segments. The fluid cytoplasm – including organelles and nuclei—is freely transported through the veins by a process commonly known as shuttle streaming. The effective mixing of granular cytoplasmic content is achieved by peristalsis, i.e., radially symmetric contractions of the veins. This mechanism results in exceptional acceleration of content with maximum speeds reaching 1 mm per second. By wave-like propagation of the peristaltic contractions, the entire organism extends also at the growing periphery. As peristalsis is mixing the contents in the cellular network, the entire organism adjusts its vein architecture efficiently with the location food sources or inhibitory cues3,4,5,6. This responsiveness helped plasmodial slime molds to enormous popularity and inspired interdisciplinary research about decentralized decision making and shortest path problems, including maze solving7.

Plasmodia of P. polycephalum usually avoid elevated sodium chloride concentrations by circumnavigation of gradients8, but they may overcome this aversion when salt is associated with a food reward. Feeding experiments demonstrated that slime molds can habituate to salt after exposure. They are then able to actively cross salt gradients to reach food9. Broussard et al.10 found that the habituated plasmodia contained ten times more salt than naïve slime moulds. There is thus a link between the salt concentration in the organism with a sort of memory or habituation. While it has not been shown where salt is preferentially concentrated in the plasmodium, it is clear that the organism learned to cope with the excess of salt. However, the transcriptomic reaction underlying the reactions to salt stress remained unexplored. So far, transcriptomic studies of slime molds focused on the developmental transition from the plasmodial (diploid) stage to the formation of sporocarps for production of meiotic spores (haploid state). This research revealed differential expression of genes associated with chromatin remodelling and meiotic recombination11,12. Recent research in spatial transcriptomics by Gerber et al.13 has provided unprecedented insights into gene expression regulation of P. polycephalum by showing that gene expression is spatially heterogeneous within the plasmodial network. The localised transcriptional responses suggest that nuclei act as mobile processors depending on local conditions for their transcriptional response. This suggests a fine-tuned regulatory system under naïve conditions, but it remained unclear what systemic transcriptional response is more generally elicited by environmental factors, e.g., when osmotic stress distributed throughout the entire plasmodial network. Also, the relationship between transcriptional changes in P. polycephalum and corresponding structural adaptations of the cytoplasmic network has yet to be studied. Here, we examine how P. polycephalum responds to salt stress, by analysing structural modifications in its tubular network as well as corresponding changes in gene expression. By identifying transcriptional shifts that correlate with morphological adaptations, we elucidate mechanisms that enable P. polycephalum to tolerate and mitigate osmotic stress.

Material and methods

Cultivation of Physarum polycephalum

Experiments were carried out with the Japanese strain of Physarum polycephalum, kindly provided by Andy Adamatzky (Bristol) in its sclerotial state in 2011 (originally from Hakodate University, Japan) and maintained in culture in our lab since then. The plasmodial stage was cultivated in the dark at 22 °C, with humidity levels in closed Petri dishes typically exceeding 95% (measured using minaturized datalogger inside the Petri dishes). To investigate the growth and adaptation of P. polycephalum under different salt concentrations, plasmodia were initially grown in 90 mm Petri dishes (Sarstedt, 92 × 16 mm, no. 82.1473.001) containing 1.2% salt-free water-agar (Roth, Agar–Agar Kobe I, no. 5210). Growth was allowed to proceed until the plasmodium covered the majority of the agar plate, typically within five days. On the first day of culture, sterile oat flakes ("Kölln Flocken", Peter Kölln GmbH & Co. KGaA, Germany) were added after being briefly soaked in sterile Milli-Q water (Milli-Q IQ7000, Merck) to facilitate colonization by the plasmodia. Oat flakes were introduced under sterile conditions.

Once established, agar blocks fully covered with plasmodium were transferred to fresh 1.2% water-agar medium supplemented with different concentrations of sodium chloride (NaCl, Roth, no. 3957): 0, 25, 50 and 75 mM. We did not use NaCl-soaked oat flakes nor salty agar bridges as in other studies9, because we wanted to achieve a uniform exposure of the entire growing plasmodium to salt stress. Starting from the first day of transfer, growth was monitored daily by photographing the plates. 50 mM NaCl was selected for subsequent experiments, as it significantly affected architecture but did not cause extreme inhibition, unlike 75 mM NaCl, which substantially delayed growth.

Experimental design and growth monitoring

The primary objective of this study was to identify molecular-level adaptations of P. polycephalum to a saline environment while minimising miscellaneous extraneous stress. This approach ensured that observed changes in gene expression were specific to salt exposure rather than general stress responses. To assess these phenotypic adaptations, we monitored the development of P. polycephalum over several weeks, capturing photographs at 24- and 48-h post-exposure to the saline medium. These time points were chosen as they represent the period in which noticeable morphological changes and potential transcriptional shifts occur.

During the first week, growth progression was documented at 24 h and 48 h for each NaCl concentration. The plasmodium was maintained by transferring it to fresh medium every two days. This process was repeated for four weeks, with additional photographs taken after the third transfer. As growth differences between the second and third weeks were minimal, only data from weeks 1, 2 and 4 were included to illustrate the progression of the growth.

Tubular network analysis

To achieve high-resolution P. polycephalum tubular network imaging, we cultivated the plasmodium on a Gelrite-based (GELRITE®, ROTH, no. 0039) medium rather than traditional agar. Gelrite provides a highly transparent substrate, improving visualisation and measurement accuracy. Tubular network analysis was conducted under control conditions (1.2% Gelrite, 0 mM NaCl) and salt stress conditions (1.2% Gelrite, 50 mM NaCl). Measurements commenced 24 h after transferring P. polycephalum to the growth medium. First, we analysed the plasmodial front, the most metabolically active region guiding directional growth. After an additional 24 h, once the slime mould had expanded across the culture dish, we measured the entire venous network under both normal and saline conditions.

For this purpose, images were acquired at 2-s intervals over a total duration of 1 h using a monochrome industrial camera (The Imaging Source, DMK 23UP031). The diameter and contraction/expansion (frequency) of the veins were analyzed over time using MATLAB (R2022, MathWorks).

To minimize measurement noise, a non-local means filtering algorithm was applied with a filter intensity of 8, a template window size of 5 pixels, and a search window size of 21 pixels. The venous contraction/expansion frequency was estimated using Welch’s method with a 90% overlap and subsequently corrected according to the methodology described by Cerna and Harvey14). Statistical differences between groups were determined using Student’s t-test.

RNA extraction, library preparation and sequencing

Biomass of P. polycephalum was collected from a 1.2% water-agar medium after four days of growth using a sterilised spatula. Samples were stored in Eppendorf tubes at -80 °C until RNA extraction. A total of six samples were processed: three control samples (C) grown in a salt-free medium and three treatment samples (T) exposed to 50 mM NaCl.

Total RNA was extracted using a phenol/chloroform protocol. Briefly, samples were homogenised with sterile pistils and an extraction buffer (0.2 M Tris–HCl, pH 9; 0.4 M LiCl; 25 mM EDTA; 1% SDS) was added along with an equal volume of phenol (1:1). After vortexing and centrifugation at 21,630 rcf (RT, room temperature), the supernatant was extracted twice, first with phenol and then with chloroform, followed by a final centrifugation step. The RNA was initially precipitated using 8 M LiCl for 20 min at 4 °C, followed by a secondary precipitation with 3 M sodium acetate and ice-cold 100% ethanol at 4 °C overnight. The resulting RNA pellet was recovered by centrifugation (20 min, 4 °C, 21,630 rcf), subsequently washed with 80% ethanol, air-dried, and resuspended in 25 µL of Milli-Q water.

Macrogen Europe© performed library preparation and sequencing. RNA integrity and purity were assessed using an Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer (or 2200 TapeStation). Libraries were prepared using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA LT Sample Prep Kit and sequencing was carried out on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, generating 151 bp paired-end reads.

Transcriptome analysis

Bioinformatic analyses, including de novo transcriptome assembly and differential gene expression (DEG) analysis, were performed by Macrogen Europe©. Raw sequencing reads were processed using Trimmomatic15 to remove adapter sequences and low-quality reads. The filtered reads were then assembled de novo using Trinity16 with default parameters.

To refine the assembled transcriptome, the longest contigs were filtered and clustered into non-redundant transcripts using CD-HIT-EST17. Open reading frames (ORFs) of at least 100 amino acids were predicted and extracted using TransDecoder (v3.0.1).

For DEG analysis, trimmed reads were aligned to the assembled transcriptome reference using Bowtie (v1.1.2)18, and transcript abundances were estimated using RSEM. Low-quality transcripts were filtered and DEGs were identified using fold-change criteria (|fc|≥ 2) and a raw p-value < 0.05. Hierarchical clustering was performed using the Euclidean distance method with complete linkage to group similar samples and contigs.

Functional annotation was conducted using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO) databases19,20,21. Data visualisation, including DEG representation, was performed in RStudio (v1.4.1103).

Results

Salt tolerance

Exposure to saline media did not generally impair the ability of Physarum polycephalum to grow and spread on a Petri dish. Within 24 h, regardless of NaCl concentration, the plasmodium successfully explored the entire surface (Fig. 1). However, after 48 h, noticeable differences arose, particularly at higher salt concentrations.

Growth dynamics of Physarum polycephalum under different salt concentrations. Time-lapse analysis of P. polycephalum expansion and tubular network formation over 24- and 48-h following transfer to media with varying NaCl concentrations (0, 25, 50 and 75 mM). The images illustrate the morphological changes and growth patterns observed at each salt concentration, highlighting differences in network density, expansion rate and structural organisation in response to osmotic stress.

It took the plasmodia generally longer to explore the entire agar surface at higher salt concentrations. While coverage was rapid in the 0 mM NaCl condition in the range of one day, the process was delayed at 50 and 75 mM NaCl. The plasmodium also developed surface-detaching coralloid structures at these concentrations, a phenomenon often associated with nutrient depletion22. From the second week onward, the growth rate remained consistently slower across all salt-exposed conditions (25, 50 and 75 mM NaCl). The plasmodial network retained a more dispersed and less structured morphology, similar to that observed in the early stages at 50 and 75 mM NaCl. With the slower growth rate at 50 and 75 mM NaCl, slowed and the tubular network displayed a less structured architecture, i.e., fewer prominent major veins developed compared to the naïve and 25-mM conditions. This reduction in large veins coincided with a shift in growth pattern, where the expansion of plasmodia changed from unidirectional to more isotropic expansion.

The 25 mM NaCl condition induced minimal changes during the first week, while 75 mM NaCl consistently led to slower and altered growth patterns across all weeks, suggesting excessive stress that could result in nonspecific changes in gene expression. To ensure that subsequent analyses captured significant yet specific molecular responses, we therefore chose 50 mM NaCl for further analyses. The 50 mM NaCl concentration provided an intermediate effect, inducing notable morphological and behavioural changes without severely impairing growth.

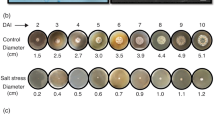

In addition to a general assessment of network appearance, we quantitatively examined the peristaltic contraction frequency and vein diameter in the network (Fig. 2). Under saline conditions, P. polycephalum exhibited a lower overall frequency of vein contractions compared to control conditions, though values were slightly higher in the frontal zone. The average vein diameter also decreased under salt exposure as a structural adaptation to osmotic stress. This decrease reconciles with the network uniformization and loss of dominating veins.

Phenotypic characterisation of the P. polycephalum tubular network under salt stress. Box plots showing the vein diameter variation (Δ [µm]) and estimated pulsation frequency (Hz) in P. polycephalum under control (purple) and saline conditions (blue). The top row represents measurements taken at the plasmodial front, while the bottom row corresponds to the entire trailing tubular network. Asterisks (***, p < 0.05) indicate significant differences between conditions.

Differential gene expression analysis

The de novo transcriptome analysis yielded 17,785 contigs (transcripts) from an initial dataset of 96,508, following filtering and removal of low-quality sequences. Statistical analysis identified 2236 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) based on the criteria |fc|≥ 2 and raw p-value < 0.05. Among these, 1027 genes were up-regulated, while 1209 were down-regulated (Fig. 3a/b).

Transcriptomic analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in P. polycephalum under salt stress. (a) Volcano plot showing differentially expressed contigs between P. polycephalum grown in control (0 mM NaCl) and salt-stressed (50 mM NaCl) conditions. Yellow dots represent significantly up-regulated genes, while blue dots indicate significantly down-regulated genes (|FC|≥ 2, raw p-value < 0.05). (b) Bar plot depicting the total number of up-regulated (1027 genes) and down-regulated (1209 genes) transcripts in the salt-treated condition. (c) Hierarchical clustering heatmap of 2236 DEGs, illustrating expression patterns across control (JAP_C) and salt-stressed (JAP_T) samples. The colour gradient represents Z-score normalised expression values, with yellow indicating up-regulation and blue indicating down-regulation.

Hierarchical clustering analysis of DEGs (Fig. 3c) revealed a clear distinction between samples grown in 50 mM NaCl (treatment group) and those in salt-free conditions (control group).

This result confirmed that osmotic stress induces distinct transcriptomic changes in P. polycephalum, aligning with observed phenotypic adaptations. To further explore functional shifts, we focused on the 40 most differentially expressed genes (Fig. 4), comprising the top 20 up-regulated and top 20 down-regulated genes.

Top 20 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in P. polycephalum under salt stress. Bar plot representing the 10 most up-regulated (yellow) and 10 most down-regulated (blue) genes based on fold change (|FC|≥ 2). Up-regulated genes include cytochrome proteins, transcription regulators and membrane-associated proteins, while down-regulated genes include enzymes involved in macromolecule degradation, such as glucosidases, peptidases and chitinase.

Up-regulated genes and ion transport mechanisms

Many up-regulated genes encode cytochrome proteins, transcriptional regulators and membrane-associated components. Notably, importins and transmembrane proteins such as "transmembrane protein 86B" were significantly overexpressed. Many up-regulated genes were involved in molecular and ion transport, likely reflecting cellular adaptations to the increased intracellular sodium concentration caused by exposure to NaCl.

Specifically, four DEGs encoded membrane transport pumps that regulate sodium ion homeostasis (Fig. 5). Two of these genes were up-regulated, while two were down-regulated. The up-regulated genes included a Na/H pump (GO:0,015,385, localised in the Golgi apparatus). This pump facilitates sodium sequestration within Golgi vesicles while exchanging protons into the cytosol, potentially helping maintain intracellular pH balance.

Differential expression of sodium membrane transport pumps in P. polycephalum under salt stress. (a) Up-regulated sodium transporters located in the plasma membrane and vacuolar membrane, facilitating sodium ion efflux to maintain intracellular ion homeostasis (fold changes: 3.86, 2.96). (b) Down-regulated sodium transporters in the plasma membrane, likely reducing sodium influx to prevent further intracellular accumulation (fold changes: -2.34, -2.60). Arrows indicate the direction of sodium ion movement across the membrane.

Further upregulation affected a sodium/bicarbonate pump (GO:0,035,735), that is found in the plasma membrane. This transporter is homologous to Slc4a11 in Mus musculus and plays a role in bicarbonate and sodium ion extrusion, essential for sustaining redox homeostasis under stress conditions.

Down-regulated genes and energy conservation

Sodium ion homeostasis was also affected by down-regulation of two other, sodium/calcium (GO:0,005,432) and sodium/hydrogen-potassium (GO:0,006,814) membrane pumps.

Further, several down-regulated genes were involved in the breakdown of certain macromolecules, including chitinase, glucosidases and peptidases. This suggests that P. polycephalum might suppress certain intracellular degradation pathways to avoid additional osmotic imbalance. Reducing the breakdown of polysaccharides could prevent further accumulation of osmotically active sugars, stabilising intracellular osmotic pressure. Additionally, suppressing these metabolic processes likely serves as an energy conservation strategy, redirecting cellular resources toward stress adaptation mechanisms such as ion transport and vesicular trafficking.

Functional annotation: GO and KEGG pathway enrichment

Functional annotation of 28,435 contigs using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases provided insights into biological processes affected by salt stress (Fig. 6). GO analysis revealed that the most enriched molecular functions were catalytic activity (41.04%), protein binding (37.59%), and transport activity (4.07%). Within the cellular component category, highly represented terms included "part of cell" (39.99%), “organelle” (12.94%), "part of membrane" (10.76%) and “membrane” (9.88%), reinforcing the role of membrane-associated processes in the stress response.

Functional annotation of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases. (a) GO term distribution for DEGs identified in P. polycephalum exposed to 50 mM NaCl, categorised into molecular function, cellular component and biological process. The pie charts illustrate the most represented GO terms within each category. (b) Top 20 KEGG pathways enriched in DEGs, ranked by proportion of DEGs associated with each pathway. Bar length and colour intensity indicate pathway significance. The most enriched pathways include autophagy, lysosomal activity, glycan degradation, RNA transport and ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, reflecting cellular responses to osmotic stress.

Biological process enrichment emphasised, metabolic processes (31.94%), biological regulation (16.53%), cellular processes (14.75%), response to stimuli (4.36%), and finally cellular component organisation/biogenesis (3.34%).

KEGG pathway analysis identified 324 metabolic pathways of salt stress effects (Fig. 6). The most prominent pathways included autophagy and lysosomal activity, supporting intracellular recycling under stress. Specifically, two SNARE genes—SXT7 (fc = 2.57, p = 0.046) and SYP7 (fc = 2.28, p = 0.035), showed elevated expression in P. polycephalum exposed to 50 mM NaCl. Further enriched was glycan degradation, which may be linked to extracellular matrix modifications, as well as RNA transport and degradation, possibly reflecting regulatory adjustments in gene expression. Also, ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis as a mechanism for targeted protein degradation to remove damaged or misfolded proteins was enriched.

These findings indicate that P. polycephalum responds to salt stress through ion homeostasis regulation, cytoskeletal adjustments, metabolic suppression and enhanced proteostasis, allowing it to mitigate osmotic pressure effects and maintain cellular function.

Discussion

Our experiments demonstrate that salt stress significantly alters the organisation and expansion of the tubular network in Physarum polycephalum. These structural changes correlate with corresponding shifts in gene expression shifts. The propagation and shape of the plasmodial network of P. polycephalum is adjusted by coordination of cytoplasmic streaming patterns which transports cellular signals throughout the giant cells. When P. polycephalum was exposed to high salt concentrations, we observed a reorganisation of the tubular network (Fig. 1), including a shift from unidirectional to isometric expansion and a decrease in overall movement and contraction frequency. This result suggest that the cellular mechanics are influenced by changes in ionic charge. Differences occur in the plasmodial front, where pulsation frequency increases with salt load, and also in the rear vein network, where we observed a decrease in pulsation frequency and vein diameter. Because we studied growth on agar plates with uniform salt concentrations, the behaviour may differ in previous research about habituation to salt stress with a different experimental design, where expansive growth was measured on narrow, 15 mm wide bridges soaked in salt9. We do not exclude that the latter design could favour directed growth across a zone of stress after transcriptomic and structural reactions occurred.

P. polycephalum apparently employs efficient osmoregulatory mechanisms to tolerate environments of increased salt. One likely mechanism is the secretion of excess sodium ions into the extracellular slime layer, reducing intracellular sodium accumulation. Experiments already suggested active excretion when the slime molds recover from salt exposure10, after previous experiments indicated that prolonged exposure to repellent substances, such as salt, may reduce aversive response over time9. We suppose this might be possible by long term shifts of transcriptomic patterns reflecting acclimation, but this was not the scope of the present study. Also, whether such transcriptomic shifts may correlate with chromatin modifications and epigenetic memory formation, as found in other organisms23, or yet unexplored mechanisms, still remains to be studied.

Transcriptomic analysis revealed an upregulation of genes encoding cytochromes and membrane-associated proteins (Fig. 6). Additionally, several sodium transport pumps were overexpressed, enabling the active expulsion of Na+ ions from the cell or their sequestration into Golgi vesicles for removal (Fig. 6). The sodium influx into the Golgi apparatus likely plays a crucial role in maintaining cytoplasmic sodium homeostasis, while also contributing to pH regulation by preventing excessive intracellular acidification24. Furthermore, the Na/Ca pump was down-regulated, likely to prevent additional sodium influx and retain intracellular calcium, which is essential for maintaining actin cytoskeleton integrity and cellular dynamics25. Preventing the loss of Calcium ions could provide a first mechanism to maintain peristaltic contractions and enabling habituation. Another down-regulated pump, the Na/H–K pump, typically pumps protons or potassium into the cell while expelling sodium. Its suppression may counteract the acidification effect of the up-regulated Na/H and Na/HCO₃ pumps, thus maintaining intracellular ionic balance.

In addition to changes in membrane transport proteins, we observed the enrichment of pathways related to molecular degradation and stress adaptation, such as autophagy and lysosomal transport (Fig. 6). Analysis also showed the involvement of the SNARE protein pathway in the salt response, which is involved in vesicular fusion and transport, thus contributing to the maintenance of cellular homeostasis under stress conditions26 (Fig. 7). This suggests the critical role of functioning vesicular trafficking in stress adaptation and maintaining homeostasis under saline conditions.

SNARE-mediated vesicular transport pathway in P. polycephalum under salt stress. Illustration of SNARE protein interactions involved in vesicular fusion and transport. Green-labelled genes are present in P. polycephalum, while blue-labelled genes are up-regulated in response to salt stress. Up-regulated SNARE proteins (Stx7 and Syp7) suggest an increased vesicular trafficking activity, likely contributing to stress adaptation and cellular homeostasis maintenance. Obtained from KEGG database (map04130) and modified with BioRender. (https://BioRender.com/okxoe43).

Many degraded cellular components, glycoproteins, and polysaccharides, are components of the excreted extracellular slime layer27, which also includes granular matter, such as pigment or starch granules (unpublished observations). The slime coat serves multiple functions in Myxogastria, beyond protection against desiccation. Previous work demonstrated that the traces of their own slime could be interpreted as a spatial memory mechanism, because the slime contains inhibitory signals for the extending plasmodial fronts (auto-avoidance;28). However, the slime also seems to be in volved in allorecognition (hetero-avoidance;29,30). It would therefore be interesting to have more detailed insights about composition and structure of the extracellular slime, but so far there is limited knowledge, and we still lack information about the macromolecular arrangement of the slime and the role of extracellular ions on the viscosity of the slime. However, transcriptomic data also indicated an alteration in catalytic activity and glycan degradation pathways (Fig. 6), suggesting that the macromolecular composition and thus viscosity of secreted slime could be modified in response to salt stress31. We argue that changes in glycan degradation may well influence network expansion and mechanics through a mechanical feedback mechanism that further modifies plasmodial architecture and movement patterns. In other organisms, environmental changes, such as chemical composition or water content variations, broadly impact cell mechanics (including cytoskeletal organisation), which feeds back to shifts in gene expression32. The specific changes will of course depend on the type of organism. For example, unicellular organisms, although lacking multicellular complexity, exhibit rapid responses involving the overexpression of genes associated with osmotic balance, ionic homeostasis, and the detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS)33, and they are also able to show distinct mechanisms for responding to different grades of salinity34. In contrast, multicellular organisms display more complex responses, including tissue-specific adaptations such as the preferential accumulation of sodium in plant roots and the regulation of photosynthesis in leaves35,36, as well as cell-type–specific mechanisms, for example, the changes observed in the renal cells of tilapia37. In general, similar responses can be observed in both unicellular and multicellular organisms, each adapted to its specific characteristics. Nevertheless, our findings suggest a complex interplay between mechanics, transcription and excretion play an important role in P. polycephalum (Fig. 8). The complexity of multicellular model systems may complicate the study of involved feedback mechanisms. We therefore suggest unicellular slime mold plasmodia as a system to more deeply study such biological principles that have evolved prior to the emergence of multicellular life forms in fungal and animal kingdoms.

Proposed feedback mechanism in slime mold plasmodia. The relationship between mechanics, transcription and excretion in P. polycephalum is depicted as a cyclic regulatory system. The observed changes in movement and growth rate (“mechanics”) are directly linked to transcriptional adjustments (“transcription”), which in turn influence the composition and secretion of extracellular slime (“excretion”). These processes continuously interact and regulate each other, forming a self-sustaining feedback loop throughout the organism’s life cycle.

Data availability

The data for this study have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) at EMBL-EBI under accession number PRJEB94288.

References

Yaakoub, H. et al. The high osmolarity glycerol (HOG) pathway in fungi. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 48, 657–695 (2022).

Leontyev, D. V., Schnittler, M., Stephenson, S. L., Novozhilov, Y. K. & Shchepin, O. N. Towards a phylogenetic classification of the Myxomycetes. Phytotaxa 399, 209–238 (2019).

Dussutour, A., Latty, T., Beekman, M. & Simpson, S. J. Amoeboid organism solves complex nutritional challenges. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 4607–4611. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912198107 (2010).

Patino-Ramirez, F., Boussard, A., Arson, C. & Dussutour, A. Substrate composition directs slime molds behavior. Sci. Rep. 9, 15444. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50872-z (2019).

Reserva, R. L., Micompal, M. T. M. M., Mendoza, K. C. & Confesor, M. N. P. Excitable dynamics of Physarum polycephalum plasmodial nodes under chemotaxis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 550, 171–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBRC.2021.02.133 (2021).

Westendorf, C., Gruber, C. J., Schnitzer, K., Kraker, S. & Grube, M. Quantitative comparison of plasmodial migration and oscillatory properties across different slime molds. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/aad29d (2018).

Nakagaki, T., Yamada, H. & Tóth, Á. Maze-solving by an amoeboid organism. Nature 407, 470–470. https://doi.org/10.1038/35035159 (2000).

Adamatzky, A. Routing Physarum with repellents. Eur. Phys. J. E 31, 403–410 (2010).

Boisseau, R. P., Vogel, D. & Dussutour, A. Habituation in non-neural organisms: evidence from slime moulds. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 283, 20160446. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.0446 (2016).

Boussard, A., Delescluse, J., Pérez-Escudero, A. & Dussutour, A. Memory inception and preservation in slime moulds: the quest for a common mechanism. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 374, 1774. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2018.0368 (2019).

Barrantes, I., Leipzig, J. & Marwan, W. A next-generation sequencing approach to study the transcriptomic changes during the differentiation of Physarum at the single-cell level. Gene Reg. Syst. Biol. 6, 127–137. https://doi.org/10.4137/GRSB.S10224 (2012).

Glöckner, G. & Marwan, W. Transcriptome reprogramming during developmental switching in Physarum polycephalum involves extensive remodelling of intracellular signaling networks. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12250-5 (2017).

Gerber, T. et al. Spatial transcriptomic and single-nucleus analysis reveals heterogeneity in a gigantic single-celled syncytium. Elife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.6974 (2022).

Cerna, M. & Harvey, A. F. The fundamentals of FFT-based signal analysis and measurement (pp. 1–20). Application Note 041, National Instruments (2000).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 (2014).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnol. 29, 644–652. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1883 (2011).

Fu, L., Niu, B., Zhu, Z., Wu, S. & Li, W. CD-HIT: Accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 3150–3152. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565 (2012).

Langmead, B., Trapnell, C., Pop, M. & Salzberg, S. L. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10, R25. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25 (2009).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucl. Acids Res. 53, D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucl. Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Lee, J., Oettmeier, C. & Döbereiner, H.-G. A novel growth mode of Physarum polycephalum during starvation. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/aac2b0 (2018).

Bheda, P., Kirmizis, A. & Schneider, R. The past determines the future: Sugar source history and transcriptional memory. Curr. Genet. 66, 1029–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00294-020-01094-8 (2020).

Madshus, I. H. Regulation of intracellular pH in eukaryotic cells. Biochem. J. 250, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj2500001 (1988).

Furukawa, R. et al. Calcium regulation of actin crosslinking is important for function of the actin cytoskeleton in Dictyostelium. J. Cell Sci. 116, 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.00220 (2003).

Mizushima, N. Autophagy: Process and function. Genes Dev. 21, 2861–2873. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1599207 (2007).

Huynh, T. T. M., Phung, T. V., Stephenson, S. L. & Tran, H. T. M. Biological activities and chemical compositions of slime tracks and crude exopolysaccharides isolated from plasmodia of Physarum polycephalum and Physarella oblonga. BMC Biotechnol. 17, 76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12896-017-0398-6 (2017).

Reid, C. R., Beekman, M., Latty, T. & Dussutour, A. Amoeboid organism uses extracellular secretions to make smart foraging decisions. Behavior. Ecol. 24, 812–818. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/art032 (2013).

Masui, M., Yamamoto, P. K. & Kono, N. Allorecognition behaviors in myxomycetes respond to intraspecies factors. Biol. Open https://doi.org/10.1242/bio.060358 (2024).

Masui, M., Satoh, S. & Seto, K. Allorecognition behavior of slime mold plasmodium—Physarum rigidum slime sheath-mediated self-extension model. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/aac985 (2018).

Rosina, P. & Grube, M. A mathematical model to predict network growth in Physarum polycephalum as a function of extracellular matrix viscosity, measured by a novel viscometer. J. R. Soc. Interface https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2024.0720 (2025).

Tao, J., Li, Y., Vik, D. K. & Sun, S. X. Cell mechanics: a dialogue. Rep. Prog. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6633/aa5282 (2017).

Lv, H. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis of short-term responses to salt and glycerol hyperosmotic stress in the green alga Dunaliella salina. Algal Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2020.102147S (2021).

Fu, Y. et al. The genome and comparative transcriptome of the euryhaline model ciliate Paramecium duboscqui reveal adaptations to environmental salinity. BMC Biol. 22, 237. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-024-02026-5 (2024).

Formentin, E. et al. Transcriptome and cell physiological analyses in different rice cultivars provide new insights into adaptive and salinity stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 204. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00204 (2018).

Gautam, K. et al. RNA-Seq-based analysis of transcriptomic signatures elicited by mutations conferring salt tolerance in Cucurbita pepo. Plant Stress https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stress.2025.100775 (2025).

Huang, D. D. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics unveils cellular adaptations to high-salinity stress in kidneys of GIFT tilapia. Water Biol. Sec. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watbs.2025.100468 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support by FWF (I3613, "Learning in unicellular organisms") and by the University of Graz in the framework of the Colibri Field of Excellence. We are grateful to Doris Feiertag (Graz) for assistance in the lab.

Funding

The authors acknowledge funding by the Austrian Science Foundation FWF (I3613).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BSP and MG conceptualised and designed the study, including the experimental framework. BSP carried out the experiments. PR analysed the network vein properties. BSP and FFM performed data analysis and interpretation. BSP, PR and MG wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to reviewing and finalising the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sánchez-Parra, B., Rosina, P., Fernández-Mendoza, F. et al. Salt affects structure, function and transcriptome in the giant cells of slime molds. Sci Rep 16, 532 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29951-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29951-x