Abstract

Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) is an additive manufacturing process that builds parts by layer-by-layer spreading and selective laser melting of metal powders. The characteristics of the powder bed are closely related to laser parameters and the particle size distribution of the metal powder. However, the actual stacking height of the powder bed changes dynamically due to shrinkage during powder spreading, melting, and solidification. This study investigates the actual stacking height of metal powders by analyzing powder flow behavior during falling, spreading, melting, and solidification using the Discrete Element Method (DEM) and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). The results show that height shrinkage caused by powder spreading can be eliminated by increasing the gap between the blade and the working platform from 0 μm to 20 μm. The shrinkage rates due to solidification and liquid metal flow were found to be 8.5% and 31.5%, respectively. Furthermore, mathematical models relating the actual stacking height to layer thickness, number of layers, and solidification shrinkage were established, providing a theoretical foundation for LPBF processes with larger layer thicknesses, as well as for support structure design, printing accuracy, and allowance planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LBPF) is an mature additive manufacturing technology, with excellent performance in strength, precision, density based on layer-by-layer powder spreading1,2. The characteristics of the powder bed formed after the powder spreading directly affect the laser process parameters and part quality3, size precision and part structure4. Nan5,6 used the discrete element method (DEM) to analyse transient powder flow and jamming during powder spreading and the results showed that transient jamming in narrow gaps and size segregation in the spreading heap, the latter brought about by particle convection/circulation, adversely affect the uniformity of the spread layer. The segregation extent decreases with the increase of gap height or decrease of roller rotational speed. Liao7 studied the particle motion parameters such as powder bed morphology evolution, particle kinetic energy and pressure and the results showed that powder layer thickness has a significant impact on the density and uniformity of the powder bed. The density increases with the increase of layer thickness and eventually stabilizes. Meanwhile, a rough powder spreading surface can also effectively improve the powder spreading quality under the condition of small layer thickness parameters, mainly by affecting the movement of the layer of particles in direct contact with the powder spreading surface to reduce powder layer accumulation defects.Pan8,9,10 studied the molten pool structure evolution, temperature flow behavior and overlapping behavior in LBPF process by mesoscopic numerical simulations.The results show that the molten pool structure presents various forms, namely deep-concave, double-concave, planar, protruding, and ideal planar structures. In the early stage of forming, the molten pool exhibits a deep-concave shape under the action of multiple driving forces; while in the later stage of forming, it presents a protruding shape due to the influence of tension gradient. The flow of molten metal inside the pool is mainly driven by laser impact force, gravity of the molten metal, surface tension, and recoil pressure.

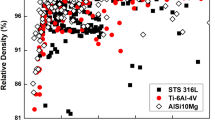

Traditionally, a fixed powder layer thickness 30 μm is applied to LPBF process11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Sujith11 used experiments and discrete element method (DEM) simulations to analyse powder bed homogeneity, and the study showed that a larger first layer thickness can improve the bulk density, but it cannot eliminate the segregation effect. In this work, the thickness of the first layer was increased by 100 μm and 150 μm with the fixed powder layer thickness of 30 μm for other layers. Jovid12 stuied the creep response and cavitation damage evolution in an additively manufactured Al-7.5Ce-4.5Ni-0.4Mn-0.7Zr (wt%) alloy with peak-aging and overaging treatments were investigated in the 300–400 °C range with the fixed powder layer thickness of 30 μm and laser parameters(laser power of 370 W, scanning speed of 1300 mm/s, hatch spacing of 0.19 mm).Fanciulli13 develop a thermoelectric generator based on catalytic combustion by additive manufacturing with with the fixed powder layer thickness of 50 μm. The compact size, the light weight, the simple design and the reliability in continuous operating conditions are all promising features of the device. Zhou14 utilized LPBF technology to fabricate FeCoCrNiMn high-entropy alloys (HEAs), and this study delved into the effects of various printing parameters, namely laser power, scanning speed, and hatch spacing, on the solidification parameters with the fixed powder layer thickness of 25 μm.Kolomy15 produced maraging steel (MS) M300 parts by LPBF and rolling, and the results show that after direct aging heat treatment, the microstructure of MS M300 fabricated by LPBF consists of martensite, dispersed precipitates and reversed austenite, and the component exhibits the highest milling forces.To improve the forming efficiency, the larger layer thickness above 100 μm has become a research hotspot22,23. However, the unknown relationship between the increasing powder layer thickness and the original powder particle size will inevitably affect the LPBF process forming parts. Additionally, researchers have ignored spreading shrinkage and metal solidification shrinkage, assuming that the height of each descent for the substrate (the layering thickness) and the distance between the top surface of parts and the working platform (the actual metal powder stacking height) are equal. Due to the spreading and solidification of metal powder24,25, actual powder stacking thickness changes dynamically on each layer.Wischeropp26 measured actual powder layer height and packing density in a single layer in LPBF by experiments, results showed that the actual powder after spreading is significantly higher than that of working platform.

To accurately predict the actual powder stacking height after spreading and to clarify the relationship between layer thickness and original powder particle size, this study systematically investigates the dynamic characteristics of powder spreading, melting, and solidification shrinkage. The shrinkage caused by powder spreading and metal solidification was quantified using DEM and CFD simulations. Furthermore, the relationship between actual stacking height, layer thickness, number of layers, and solidification shrinkage was established.

Materials and numerical simulation

Gas-Atomized AlCu5MnCdVA powder is provided by AVIC Maite Powder Metallurgy Technology (Beijing) Co., LTD. The physical parameters of the powder were reported by AVIC, including angle of response (43°), apparent density (1.44 g/cm3), tap density (1.75 g/cm3), etc. The particle size distribution ranged from 15 μm to 60 μm with D90 57 μm, as shown in Fig. 1. And the compositions of AlCu5MnCdVA is shown as Table 1.

Temperature-dependent thermo-physical properties (density, specific heat, surface tension, thermal conductivity, viscosity) were calculated with JMatPro® and are plotted in Fig. 2, and other thermal properties are shown in Table 2.

Discrete element model of LPBF powder spreading

Figure 3 showed the discrete element model of powder spreading in LPBF process. To improve the simulation efficiency, the model integrates two spreading processes with layer thickness H = 30 μm and 50 μm. After the powder dropping finishing (the number of particles is 2500), the blade begins to push powder to substrate from left to right, and the powder spreading of two layer thickness of 30 μm and 50 μm finishes successively. The blade moving speed is V = 20 mm/s with time step is 1E-06 s.

(1)Discrete element methods

The dynamics of particles during spreading is calculated using Newton equation of motion:

Where, \(\:{m}_{i}\) and \(\:{\mathbf{I}}_{i}\) are the mass and inertia moment of the particle, respectively; \(\:{v}_{i}\) and \(\:{\omega\:}_{i}\)are the translation velocity and angular velocity of the particle, respectively;\(\:{\mathbf{F}}_{c,i}\)is the interaction force between the particle and the particle or the wall; \(\:{\mathbf{M}}_{\text{c},i\:}\)is the torque caused by contact force.

(2)Contact model

Particle motion inevitably causes collisions between particles, leading to the generation of force between particles. The acceleration of particles and the velocity and displacement can be obtained by Newton’s second law. The elastic contact force during particle contact is calculated by Hertz-Mindlin model, while the adhesion force is calculated by JKR theory:

Where, \(\:\varGamma\:\) is the adhesive surface energy (0.9 mJ/m2); E * is the equivalent Young’s modulus; a is the contact radius.

The discrete element simulation of the powder spreading process was applied by Altair® EDEM™, AlCu5MnCdVA particle physical properties were obtained using Generic EDEM Material Model Database(GEMM) and Open Powder Wizard, as shown in Tables 3 and 4.

To study the influence of powder flow state on actual stacking height of the metal powder and eliminate the decrease height caused by powder spreading, the distance between the blade and the working platform is increased from 0 μm to 20 μm, and four powder spreading schemes in Table 5 are designed.

Mesoscopic numerical simulation model of LPBF powder melting and solidification

After powder spreading, laser begins to scan the powder, metal powder goes through melting and solidification after absorbing the laser energy. Figure 4 showed the mesoscopic numerical model of LPBF powder melting and solidification.The metal powder bed geometry is initialized from DEM simulation(Altair® EDEM™), and the melting and solidification process after laser irradiation adopts CFD simulation (Flow-3D™).

As shown in Fig. 4, the model of LPBF mainly includes substrate (1000 μm × 800 μm× 165 μm) and metal powder bed. The calculation domains was 1000 μm × 800 μm × 500 μm, using the volume of fluid method (VOF) method with mesh cells dimension size 5 μm. Figures 4 and 5 showed three-pass “S-type” laser scanning diagram, and LPBF process parameters was shown in Table 6.

Results and discussion

The volume change of metal powder in spreading and solidification process directly affects the actual stacking height of powder, mainly including the following five stages, and Fig. 6 showed the shrinkage zone diagram of metal powder in LPBF process, and the total height change of the powder bed during LPBF is the sum of five sequential contributions:

(1) Spreading stage: Due to the uneven particle size distribution, the powder spreading space (1000 μm × 400 μm × H) after the substrate dropping cannot be completely filled. The gray area A shown in Fig. 6 (a) and (b) is the area where the powder is not filled. The actual stacking height Hi of the powder after spreading is lower than layer thickness H, and the shrinkage height is marked as θ1.

(2) Stacking stage: Since metal powders are spherical and there are gaps between powders after spreading, the actual stacking volume of powder is smaller than original space volume. As shown in Fig. 6 (a) and (b), the purple area B is the area where the powder is not filled. And the shrinkage height is marked as θ2.

(3) Melting stage: the temperature increases sharply, the spacing between atoms increases, causing the height rise and expansion, marked as θ3. Due to the very short time, θ3 is ignored.

(4) Liquid metal flow stage: at the beginning of melting, liquid metal enters and fills the pores (purple area B), causing the height of liquid metal to decrease, marked as θ4. This area is consistent with θ2, and the calculation is no longer repeated.

(5) Liquid metal cooling stage: after complete melting, the temperature drops sharply to room temperature. Before reaching the solidification temperature, the state is mainly divided into liquid shrinkage, solid-liquid coexisting shrinkage and solid shrinkage. The inter-atomic spacing decreases, resulting in a decrease in height, marked as θ5.

Therefore, the total shrinkage height of metal powder during the whole LPBF process is simplified as below:

Shrinkage caused by powder spreading \(\:{{\uptheta\:}}_{1}\)

Figure 7 showed the six typical states of the powder spreading process in Scheme 1, in which the color represents the speed, red represents the maximum speed of 30 mm/s. A stable powder bed was formed after powder spreading in Fig. 7(f).

Figure 8 showed the height decreasing behavior of the powder stacking height caused by the powder spreading. This is mainly due to the fact that the particle size of the powder is between 15 and 60 μm, and the falling height of the substrate(layer thickness H) is 30 μm. Therefore, the powder bed cannot completely fill the blank area above the substrate, resulting in the metal actual stacking height lower than 30 μm.

To reduce the jamming phenomenon and eliminate the decrease height θ1 caused by powder spreading, the distance between the blade and the working platform is increased from 0 μm to 20 μm, and four powder spreading schemes in Table 3 are designed. Figure 9 showed the morphological characteristics in terms of top view and front view of the metal powder beds for the four powder spreading schemes. Figure 10 showed the powder bed morphology and void fraction, which are 82.47%, 80.92%, 64.67% and 61.28%, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 9(a), in the height direction, the metal powder bed in Scheme 1 was lower than the layer thickness of the substrate descent. When the distance between the working platform and the blade was increased to 20 μm, the upper surface of the metal powder bed in Scheme 2 to Scheme 4 exceeded the platform. As shown in Fig. 9(b), due to the mutual extrusion among the blade, platform, and metal powder in Scheme 2, the metal powder splattered, which resulted in obvious empty powder area in the metal powder bed and uneven distribution of the metal powder bed. As shown in Fig. 9(c), during the return stroke of the blade, since the height of the metal powder bed exceeded the plane of the platform after one-way powder spreading, collision, extrusion, and splattering occurred during the empty return of the blade. Consequently, the final powder bed in Scheme 3 had a relatively large empty powder area. Therefore, Scheme 4 was selected as the optimized powder spreading process scheme.

Figure 11 showed the powder stacking morphology of Scheme 4 with the distance between the blade and the working platform 20 μm. The powder bed after powder spreading not only reduced the splash and empty powder area caused by powder jamming as shown in Fig. 9(b), but also eliminated the metal powder height shrinkage θ1 caused by traditional powder spreading, as shown in Fig. 11(b). The actual height of the powder after spreading was equal to layer thickness, that is θ1 = 0.

By adjusting the distance between the blade and the working platform to 20 μm, θ1 for scheme 4 was eliminated and scheme 4 was selected as the optimized powder spreading scheme for the subsequent study of actual metal powder stacking.

Shrinkage caused by solidification of liquid metal θ5

In general, there are two-time heating and cooling trends in each area inside the molten pool, which are respectively the heating caused by the first-pass laser scanning, and the reheating caused by the second-pass laser scanning adjacent molten track. The temperature evolution of the molten pool was mainly divided into six stages: heating stage, liquid cooling stage, solid-liquid coexistence stage, solid cooling stage, reheating stage and cooling stage.The temperature evolution curve during LPBF process was shown as Fig. 12.

Figure 12 showed the temperature variation of the LPBF process at typical locations A and B, respectively. Point A was located at the center of the first-pass molten pool and Point B was located at the edge of the first-pass molten pool. Curves A-B-C-D-E-F-G was the temperature curve of Location A, and H-I-J-K-L-M-N is the temperature curve of Location B. Additionally, the temperature change after Point E and Point L (0.007 s) was due to the reheating caused by the adjacent second-pass laser scanning. Table 7 showed the temperature and time of the typical points for Location A and Location B.

As shown in curve A-B-C-D-E-F-G, the temperature rose rapidly to melting point temperature from 298 K at 1.109 × 10− 3 S (Point A) to 1726 K at 1.122 × 10− 3 S(Point B), and the temperature rise rate reached 1.15 × 107 K/S. For the process time of powder melting and solidification(Point B to Point D), it took only about 1.248 × 10− 3 S. In the solid-liquid coexistence zone(Point C to Point D), temperature dropped from 922.72 K to 802.21 K, with the cooling rate 1.11 × 105 K/S. Additionally, after complete solidification (Point D), laser beam moved away and the temperature dropped to 496 K at 7.17 × 10− 3 S with the cooling rate reached 6.38 × 104 K/S.

Figure 13 showed the average expansion coefficient of AlCu5MnCdVA alloy at different temperatures calculated by JMatPro, and the shrinkage θ5 caused by solidification of liquid metal is 8.5%.

Shrinkage caused by liquid metal flowing θ4

Fig. 14 showed the structural evolution of LPBF with three-pass adjacent molten tracks. To study height shrinkage caused by liquid metal flowing θ4, four typical positions were selected , as shown in Fig.14 (g).

(1) overall morphology of shrinkage in molten track(X-Z section)

As shown in Fig. 15, after absorbing laser energy, the metal powder started to melt into a liquid state, flow, and then solidified. The black area in Fig. 15(b) represented the solidified structure. Figure 15(c) showed a comparison between the original powder height and the height of the solidified part, with the red color indicating the overall shrinkage height. Compared with the original powder, the solidified molten tracks exhibited a wavy shape. Due to laser impact, the height at the front end decreased sharply. The overall shape of the molten tracks was related to the powder particle size and stacking state. Additionally, the height shrinkage shown in Fig. 15(c) mainly resulted from two factors: the shrinkage caused by the molten metal flowing into the spherical voids of the original powder bed after melting and the shrinkage caused by the solidification of the metal powder.

(2) overall morphology of shrinkage in molten molten (Y-Z section)

As shown in Fig. 16, compared with the original powder, the solidified molten pool in section D was concave, due to the action of recoil force and Marangoni effect. Additionally, molten track 2 was located in the middle of the three melting tracks, both sides of molten track 2 remelted twice, which was another reason for the concave shape.

As shown in Fig. 17, the total average percentage of shrinkage height of Al-Cu alloy was about 40%(θ4 + θ5, θ5=8.5%). So, shrinkage caused by liquid metal flow θ4 was 31.5%.

Mathematical model of powder spreading process based on solidification shrinkage and kinetics

By optimizing the process parameters, the metal shrinkage caused by the non-uniform particle size distribution was eliminated (\(\:{{\uptheta\:}}_{1}\)=0). Additionally, by mesoscopic numerical simulation, the metal shrinkage during melting and solidification is about 0.4 (\(\:{{\uptheta\:}}_{4}+{{\uptheta\:}}_{5}\)). Therefore, the total shrinkage rate of metal in the LPBF process was simplified as follows:

Mathematical model of actual powder stacking height based on solidification shrinkage and dynamics

Considering the effect of metal powder shrinkage, the actual stacking height of metal powder varies dynamically with the number of layers, material and layer thickness. Figure 18 showed the powder stacking process evolution model from the first layer to the layer i.

Symbol:

H

the height at which the substrate moves down each layer, which is the layer thickness of the laser process parameters, generally a fixed value.

Hi

the height between the top of the printed parts in layer i-1 and the top surface of working platform after the substrate moving down to H in layer i. Hi is the actual stacking height of powder after powder spreading on layer i with \(\:{{\uptheta\:}}_{1}\)=0.

ti

the height of metal powder after solidification in layer i.

\(\:\varDelta\:{\text{h}}_{\text{i}}\)

the shrinkage height of the powder after solidification in layer i.

δ

the ratio of the height after powder solidification to the height before powder solidification, \(\:{1-({\uptheta\:}}_{1}+{{\uptheta\:}}_{4}+{{\uptheta\:}}_{5})=0.\)6.

Therefore:

As shown in Fig. 18, the actual stacking height Hi was equal to the sum of the falling height of substrate (H) and the shrinkage of metal powder in layer i-1 (Hi−1\(\:\times\:\)(1-δ)).

This is a typical recursive problem:

The actual stacking height of metal powder after powder spreading:

The height of metal powder after solidification in layer i:

The shrinkage height of the powder after solidification in layer i:

Mathematical model of actual powder stacking height and layer number i

Traditionally, H is a constant value in LPBF, and the ratio δ is related to the material characteristics and particle size distribution. Therefore, the actual stacking height Hi of metal powder in layer i and the number of powder layers i are exponential functions:

Taking layer thickness H = 30 μm and δ = 0.6 as an example, the relationship between the actual stacking height of metal powder Hi and the number of spreading layers i was shown in Fig. 19. When the spreading layers reaches 10, the actual stacking height of metal powder gradually increases from 30 μm to 49.9947 μm. It is interesting to find that when the number of spreading layers reaches 25, the actual stacking height of metal powder remained 50 μm. Final stable metal powder stacking thickness Hs was 50 μm, which provides the theoretical reasons for the traditional printing requirements of powder particle size ranging from 15 μm to 53 μm.

To ensure the consistency of the internal quality of the parts, support should be added at the bottom of the parts, and the height of the support is at least 25×H (30 μm) = 750 μm. The support can be cut by machine processing or manual removal.

Mathematical model of stable metal powder stacking thickness and layer thickness H

To improve the forming rate, increasing the layer thickness H had become a research hotspot. Figure 20 showed the relationship between various layer thickness H (30 μm, 60 μm, 80 μm, 100 μm, 120 μm, 140 μm, 160 μm, 180 μm) and stable metal powder stacking thickness Hs.

It was interesting to find that stable metal powder stacking thicknesses Hs always reached in layer 25 and Hs was linear direct proportional function to the layer thickness H, which revealed the relationship between the maximum size acquirement of the metal powder and the layer thickness H in the larger layer thickness LPBF process.

Metal powder stacking thickness experiment

Experimental method

In this work, to reliably and conveniently verify the actual stacking height of the metal powder, and considering that it is impossible to measure the thickness from the upper surface of the printed part to the substrate after each layer (the actual powder stacking height for the next layer), the actual stacking thickness of the metal powder during printing is calculated as below:

Where: Hi is actual powder stacking height of the i layer, H is powder layer thickness, i is the number of spreading layers, Ti−1 is height of the printed part in (i − 1) layer.

The main steps of the metal powder stacking experiment are as follows:

(1)Select the metal powder printing parameters from Tables 1 and 2, totaling 27 groups, corresponding to 27 parts with different numbers of layers.

(2)Use a coordinate measuring machine (CMM) to measure the actual height of the printed parts in Tables 1 and 2.

(3)Calculate the actual powder stacking height for each layer using Formula (14).

(4)Compare the measured height from Step 3 with Formula (9) to verify its reliability.

Table 9 showed the 15 parameters for the metal powder stacking experiment, with the number of layers increasing from 1 to 300. Figure 21 showed the corresponding 3D model.

To study and measure the relationship between stable powder stacking thickness and the number of layers, the parameters in Table 10 were selected, focusing on parts printed from layer 15 to 30. Figure 22 showed the corresponding 3D model. Figure 23(a) showed the status of the blade and substrate before powder spreading. The distance from the blade to working platform was set to 20 μm, as shown in Fig. 23(b).

3D model for Table 2

Testing method

Figure 24 showed the printed square test parts. To accurately measure the actual thickness of the printed parts, the Coordinate Measuring Machine (CMM) was used to measure the thickness of all 27 printed parts in Tables 1 and 2, as shown in Fig. 25(a). Then, a wire-cutting machine was used to retain a 2 mm thick substrate, and the printed parts were cut along its cross-section. Figure 25 (b) showed the printed parts after cutting. The cross-sectional heights were again measured using a CMM. The average of the two measurements was taken as the actual printed height of the part.

Discussion of experimental results

The experimental measurements showed that the actual metal powder stacking thickness begined to fluctuate after about layers 20 and reached a stable value after more than 50 layers. This was mainly due to the influence of powder particle size distribution, laser-powder interaction, airflow, and printer precision. The surface roughness of the printed parts ranges to 20 μm. Considering the actual measurement data and the complexity of LPBF manufacturing, the measured data showed significant fluctuations. Therefore, to ensure the internal quality consistency of the part, supports should be added at the bottom of the part, with a height of at least 50 × H layers. During this height range, the actual powder stacking height fluctuates dynamically, leading to uneven quality of each printed layer. The supports should be removed later by machining or manual cutting.

Conclusions

In this work, the dynamic evolution rule of the metal powder actual stacking thickness in LPBF was systematically studied. With CFD and DEM simulation, five parameters of powder spreading and metal solidification that affect the actual metal powder stacking thickness were obtained. Additionally, the mathematical model of the actual stacking height based on metal powder spreading and solidification were obtained.

-

(1)

The total volumetric shrinkage (θ = 40%) is partitioned into 8.5% solidification contraction (θ₅) and 31.5% liquid infiltration (θ₄). Spreading-induced shrinkage (θ₁) can be eliminated by increasing the blade–platform gap to 20 μm for the powder studied.

-

(2)

For the specified material and fixed layer thickness, the actual stacking height (Hi) is an exponential function to the number of powder spreading layers i, \(\:{H}_{i}=H\times\:\frac{{1-\left(1-\delta\:\right)}^{i}}{\delta\:}\).

-

(3)

The stacking height reaches stable after approximately 25 layers, independent of H. This provides a theoretical justification for the common powder size range 15–53 μm and recommends a minimum support height of 25 H for quality consistency.

-

(4)

For the specified material and different layer thicknesses H, the stable metal powder stacking thickness Hs is a linear function with the layer thickness H,\(\:{H}_{s}=1.6667\times\:H\), which provides the theoretical requirements between the maximum size requirement of the metal powder and the layer thickness H in the larger layer thickness LPBF process.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Miao, G. X., Du, W. H., Pei, Z. J. & Ma, C. A literature review on powder spreading in additive manufacturing[J]. Additive Manufacturing,2022(58),103029.

Zhang, H. Yunzhong Liu.Microstructures and elevated temperature mechanical properties of AlSi12Cu4Ni2 fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. J. Manuf. Processes 2023, 90: 418–428 .

Chen, H. et al. A review on discrete element method simulation in laser powder bed fusion additive Manufacturing[J]. Chin. J. Mech. Engineering: Additive Manuf. Front. 1 (1), 13 (2022).

Sun, Y., Jiang, W. G. & Xu, G. G. Influence of the rough surface of the constituency laser melting forming area on the powder quality: discrete element simulation [J]. J. Mech. 53 (12), 3217–3227 (2021).

Nan, W., Pasha, M. & Ghadiri, M. Numerical Simulation of Particle Flow and Segregation during Roller Spreading Process in Additive manufacturing[J] (Powder Technology, 2020).

Nan, W. & Ghadiri, M. Numerical simulation of powder flow during spreading in additive manufacturing[J]. Powder Technol., 342. (2018).

Liao, F. Y. Powder Bed Spreading Process Research Based on Selective Laser Melting Technology [D] (Chongqing university, 2020).

Pan Lu, Zhang, C. L. et al. Molten pool structure and temperature flow behavior of green-laser powder bed fusion pure copper[J]. Mater. Res. Express ,9,016504,2022.

Lu, P. et al. Mesoscopic simulation of overlapping behavior in laser powder bed additive manufacturing[J]. Mater. Res. Express. 8 (12), 125801 (2021).

Pan Lu, Z. et al. Molten pool structure, temperature and velocity flow in selective laser melting AlCu5MnCdVA alloy[J]. Mater. Res. Express. 9 (4), 101088 (2020).

Sujith, R. J. et al. Numerical and experimental analysis of powder bed homogeneity through multi-layer spreading in additive manufacturing. Additive Manufacturing[J], (97), 104571 (2025).

Jovid, R. et al. Creep ductility limiting mechanisms in an additively manufactured Al-Ce-Ni-Mn-Zr alloy.Additive Manufacturing[J], 2025(112),104983.

Fanciulli, C. et al. Additive fabrication and experimental validation of a lightweight thermoelectric generator. Sci. Rep. 13, 10042 (2023).

Zhou, Z. et al. Effects of LPBF printing parameters on the columnar-to-equiaxed grain transition in FeCoCrNiMn alloys. Sci. Rep. 15, 21893 (2025).

Kolomy, S. et al. Comparative analysis of machinability and microstructure in LPBF and conventionally processed M300 Maraging steel. Sci. Rep. 15, 35980 (2025).

Rangapuram, M. et al. Multiphysics modeling and experimental validation of high-strength steel in laser powder bed fusion process[J]. Progress Additive Manuf., (6):9. (2024).

Li, Q., Jiang, W. G., Qin, Q. H. & Tu, Z. X. Duo-Sheng Li.Particle-scale computational fluid dynamics study on surface morphology of GH4169 superalloy during multi-laser powder bed fusion with low energy density.Journal of Manufacturing Processes,92:287–296. (2023).

Abrami, M. B. et al. Prediction of microstructure for AISI316L steel from numerical simulation of laser powder bed Fusion[J].Metals and materials international, 28(11):2735–2746. (2022).

Xu, R. & Nan, W. Analysis of the metrics and mechanism of powder spreadability in powder-based additive manufacturing. Additive Manufacturing[J],2023(17),103596.

Pauza, J. & Rollett, A. Simulation study of hatch spacing and layer thickness effects on microstructure in laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing using a Texture-Aware solidification Potts model. J. Materi Eng. Perform. 30, 7007–7018 (2021).

Holden, C., Hyer, C. M. & Petrie Effect of powder layer thickness on the microstructural development of additively manufactured SS316[J]. J. Manuf. Process. 76, 666–674 (2022).

Zhang, J., Yang, G. L. & Xu, X. Effect of coating thickness on density and surface morphology of selective laser melting 316L deposition layer [J]. Ploidy Surf. Technol., 51 (03): 286–295. (2022).

Wang, S., Liu, Y. D. & Qi, B. District laser melting and performance study the forming process of 316 l big thick [J]. Appl. Laser, 2017 5 (6): 801–807. The DOI: 10.14128 / j.carol carroll nki. Al. 20173705.801.

Shi, X. et al. Performance of high layer thickness in selective laser melting of Ti6Al4V. Materials 9 (12), 975 (2016).

Ding, H., Fu, H. Z. & Liu, Z. Y. Solidification shrinkage compensation and hot cracking tendency of alloys [J]. Acta Metall. Sin., 1997(09):921–926 .

Wischeropp, T. M. et al. Measurement of actual powder layer height and packing density in a single layer in selective laser. Melting[J] Additive Manuf., 28 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Anhui Top Manufacturing Technology Co., Ltd and Anhui HIT-3D Technology Co., Ltd.

Funding

This work was supported by Wuhu Metal Matrix Composite Laser Additive Manufacturing Engineering Technology Research Center(KJCXPT202203).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Pan Lu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Data curation, Writing-original draft. Liu Tong: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation. Liu Jiang-lin: Experimentation and Investigation. Zhang Heng-hua: Methodology, Data curation and Investigation. Zhang Mei: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Writing-review.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, P., Chen-lin, Z., Tong, L. et al. Exploring the actual stacking height of metal powder bed in laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Sci Rep 16, 2851 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29968-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29968-2