Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a growing global health problem. We aimed to evaluate the ability of body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), and waist-height ratio (WHtR) to detect type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) among adults in Northern Sudan. A multi-stage sampling survey was conducted in Northern Sudan. The information was obtained on the sociodemographic and anthropometric indices (BMI, WC, and WHtR). A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and a multivariate binary analysis were performed. Among the 396 adults included in the study, 201 (50.8%) were male, and 195 (49.2%) were female. The median (interquartile, IQR) for age, BMI, WC, and WHtR were 45.0 (33.3‒55.8) years, 26.5(22.5‒30.5) kg/m2, 84.0(73.8‒95.0) cm, and 0.46 (0.40‒0.53), respectively. The median values of BMI, WHtR, and WC were higher in females than in males. Of the total, 107 (27.0%) adults had T2DM. The median (IQR) of BMI, WC, and WHtR were significantly higher in adults with T2DM than in those without T2DM. BMI (AUC = 0.55, cutoff = 25.17 kg/m2, sensitivity = 0.68, specificity = 0.48, PPV = 32.6, NPV = 80.2), WHtR (AUC = 0.62, cutoff = 0.44, sensitivity = 0.74, specificity = 0.40, PPV = 34.4, NPV = 84.8), and WC (AUC = 0.63, cutoff = 79.28 cm, sensitivity = 0.78, specificity = 0.47, PPV = 35.3, NPV = 85.1), had poor predictability in detecting T2DM in adults. In multivariate analysis, being female (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 1.66, 95.0% CI 1.01‒2.73), increased age (AOR 1.04, 95% CI 1.03‒1.06), and increased WC (AOR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01‒1.04) were associated with T2DM. BMI and WHtR were not associated with T2DM. BMI, WC, and WHtR showed poor predictive value for detecting T2DM among adult Sudanese.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most common chronic diseases associated with significant morbidities, mortalities, and economic burdens1,2. It has been estimated that around half a billion people are living with DM worldwide, and this figure is expected to increase to 12.2% (783.2 million) in 20451,3. T2DM is the most common type of diabetes, accounting for over 90% of all diabetes worldwide1. A higher prevalence of DM was reported in high-income countries (11.1%) compared to low-income countries (5.5%), and in urban (12.1%) than rural areas (8.3%)3. Half of adults (20–79 years old) with DM were unaware of their diabetes status (44.7%; 239.7 million); almost 90% of people with undiagnosed DM live in low- and middle-income countries, in particular among the African population (53.6%)1,4,5. Patients with undiagnosed DM had considerable complications related to DM, such as microvascular and macrovascular complications5. In North Africa, it has been reported that the prevalence ranged from 2.6% in rural Sudan to 20.0% in urban Egypt6. Likewise, a higher prevalence of undiagnosed DM (18–75%) was reported in Northern Africa, with a higher prevalence of chronic complications related to T2DM6. On the other hand, maintaining reasonable glycaemic control is the cornerstone of preventing or modifying DM-related complications7. Thus, screening for T2DM, especially among higher-risk groups, is of paramount importance and may improve T2DM prognosis and minimize its complications. It is worth mentioning that some microvascular complications are two-to-three-fold higher in youth with T2 DM compared to those with type 1 DM of a similar age group8.

Body mass index (BMI) has been widely used as a convenient and straightforward measure of adiposity and obesity in many epidemiological studies, despite limitations in assessing body fat distribution or differentiating between body fat and lean mass9. There was substantial supporting evidence indicating that visceral adiposity, rather than overall body adiposity, is associated with metabolic complications10. Hence, anthropometric indices such as BMI, mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC), waist circumference (WC), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) are widely advocated to assess visceral adiposity10. Visceral adiposity is associated with cardiometabolic syndrome: insulin resistance, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hyperuricemia11. Weight, WC, and BMI are the most reliable indices for predicting T2DM in low- and middle-income countries12. WC, WHR, and WHtR are used to assess body fat distribution and obesity, as they are simple, practical, and low-cost tools13. Several previous studies have demonstrated the significant utility of these valuable anthropometric indices for screening and diagnosing T2DM across different populations worldwide14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

According to the IDF, Sudan is among the countries with a DM prevalence above 12%1. This was supported by recently published studies indicating high prevalence in northern Sudan (19.1%)22 and eastern Sudan (20.8%)23. Recent data demonstrated a considerable percentage of newly diagnosed T2DM (10.0‒31.3%) and markedly higher prevalence of uncontrolled T2DM (80.0‒84.3%)23,24. Several studies from Sudan reported higher prevalences of overweight and obesity in the general population in northern Sudan (36.37% and 24.53%)22, (33.6% and 26.8%)25, and in eastern Sudan (26.5% and 32.7%)23. Likewise, a population-based survey conducted in Sudan showed a higher prevalence of overweight (39.9%) and obesity (24.5%) among individuals with T2DM25. A higher prevalence of obesity among patients with T2DM was reported in eastern Sudan (32.2%)26. Among other countries, Sudan lacks accurate data and well-established, sophisticated health systems to assess and provide comprehensive management for this patient group6. Moreover, Sudan is among the countries with the least diabetes-related health expenditure (USD) per person with T2DM (less than 250 dollars per year)1. Additionally, no data on the accuracy of anthropometric indices in screening for T2DM in Sudan have been published. Moreover, obesity may be influenced by ethnicity, genetic, and epigenetic factors, which may be reflected in anthropometric measurements across different populations27. Hence, in clinical settings, to assess non-communicable diseases, the cutoff point might be adjusted to increase the screening test’s sensitivity and enhance the ability to identify potentially significant health outcomes28.

Moreover, some studies have highlighted Africa’s unique racial composition, genetics, culture, socioeconomic factors, dietary patterns, geography, environment, and political structures, as well as the need for Africa-specific studies to address the risk factors associated with T2DM29,30. Additionally, understanding the specific relationships between potentially modifiable risk factors, such as biological, behavioral, and psychosocial factors, and T2DM in African populations is of paramount value for effective primary prevention and earlier detection efforts to modify the prognosis29,30. However, no prior studies have evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of anthropometric indices in identifying T2DM among Sudanese adults. Hence, to address all points mentioned above, we conducted this study to assess the ability of BMI, WC, and WHtR to detect T2DM among Sudanese adults in Wad Hamid locality, northern Sudan.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Almatamah Health Authority, Sudan, under reference #9, 2021. All participants recruited for the study signed written informed consent forms after proper explanations regarding the study and its aims. The authors had a direct follow-up to ensure all necessary measures, including participants’ privacy, confidentiality, and safety, were taken, such as excluding personal identifiers during data collection.

It was a cross-sectional study targeting Sudanese adults aged 18 and above from September 1 to December 31, 2022. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were strictly followed for study31. A written informed consent form was gathered from all participants, indicating their acceptance of participation in the study. A multi-stage sampling study was conducted in Wad Hamid city, a locality in the River Nile State in Northern Sudan. The residents of Wad Hamid are Arab tribes, and minorities are Nubian and African tribes, who have a long history of living along the Nile River in Northern Sudan. Wad Hamid locality is one of the four localities (the smallest administrative unit in Sudan) in the River Nile State. Initially, random sampling was performed, and the locality was divided into four sectors based on their population size. A lottery method was used to randomly select all adult participants in households in these four sectors. If no candidates were available in a selected household, or household members refused to participate or met any exclusion criteria, the next household was an alternative.

Inclusion criteria

All healthy adult Sudanese citizens, both male and female, residing in the study area and aged 18 years or above, agreed to participate with written informed consent. Moreover, all participants with T2DM on diet control or glucose-lowering drugs were included.

Exclusion criteria

Age below 18 years, individuals with chronic diseases (based on participants interview regarding diagnosis, specialty follow up, medical report and current medications) such as chronic kidney diseases and heart failure, critically ill patients with severe acute illness, those on hormonal or chronic medication (e.g. steroids), those who had any apparent congenital dysmorphism, and those with missing data and who refused to participate in the study. In addition to T1DM, pregnant women, patients with hemoglobinopathies, or current medications like steroids and hormonal contraceptives were excluded, too.

Participants

Each participant who signed the informed consent forms was interviewed using a comprehensive questionnaire, designed based on data collection tools from previous studies22,23,25,26. The sociodemographic characteristics were obtained in the same questionnaire: age in years, sex, marital status, job, education, smoking habits, drug history, and family history of T2DM. The anthropometric indices: weight, height, WC, BMI, and WHtR) and sociodemographic characteristics were obtained in the same questionnaire: age in years and sex. Two senior-trained nurses were assigned to collect the anticoagulated venous blood sample (5 mL) and mix it gently before sending it immediately to measure HbA1c.

Diabetes mellitus

Adults were considered to have T2DM if they were already diagnosed before with T2DM by a physician, and were on diet control or glucose-lowering drugs during the time of the study, or if their HbA1c ≥ 6.5% as per the guidelines and recommendations of the “International Diabetes Federation guideline for non-pregnant adults”32. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) was used as an anticoagulant for the collected venous blood sample (5 mL), which was then mixed gently and sent directly for laboratory investigations. HbA1c was tested using an Ichroma machine following the manufacturer’s instructions (Chuncheon-si, Gang-won-do, 24398, Republic of Korea). Calibration was stable for at least fifty days. The process was under the control of two primary investigators, and the central laboratory measures.

Four trained medical officers interviewed participants during the study period, and eight trained paramedical staff collected blood samples, measured participants’ anthropometric indices, and recorded these measurements on the questionnaire sheet. To improve the accuracy of the collected data, key quality control measures include using certified medical personnel, adopting standard operating procedures, ensuring equipment is robust and well-calibrated, and training all staff to meet specific measurement standards and inter-observer reliability targets, under the direct supervision of two primary investigators.

Anthropometric measurements

Generally, all measurements were checked twice to get the averages for the study. A third reading was performed when significant differences were observed between the first two readings across all measures.

Weight and height measurements

We ensured that all participants wore light clothing and no shoes while measuring weight and height. The well-calibrated scales of standard procedures were used to measure participants’ weights in kilograms, adjusted to zero before each measurement and to the nearest 100 g. The participants were asked to stand straight, with their backs against the wall and their feet together, allowing their heights to be measured to the nearest 0.1 cm.

BMI

BMI was calculated by dividing participants’ weight (kg) by their height (m2).

WC

The participants adopted a relaxed standing position and were directed to fold their arms. Seca 203 tape (made in Germany) was used for measuring WC. Then WC was measured in centimeters with a non-stretchable tape held at the level of the navel while the subject was standing without clothing at the end of the normal expiration at the midpoint between the superior border of the iliac crest and the lower margin of the least palpable chest rib33.

WHtR

WHtR was calculated by dividing WC (in centimeters) by height (in centimeters).

Sample size

The sample size of 396 participants was calculated based on the assumption that 25.0% of adults would have T2DM, as reported previously34, and that anthropometric measures (BMI and WC) would have a sensitivity of 90.0% to detect T2DM. It is expected to have 80% power and a difference of 5% (α = 0.05)35.

Statistical analysis

IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences® (SPSS®) for Windows, version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., New York, United States), was used to analyze the Data. Frequencies (%) were adopted to express the proportions. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of continuous data (age, height, weight, BMI, WC, WHtR, and HbA1c readings), which showed nonnormal distributions; therefore, they were reported as medians (interquartile ranges [IQR]). Medians were compared between the two groups using the Mann–Whitney U test. Correlations between anthropometric indices and HbA1c levels were assessed. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to determine the predictive power of various body composition indices for T2DM diagnosis among Sudanese adults. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) was used to assess the predictive power of these anthropometric indices for detecting T2DM. The obtained AUCs were classified according to their power: 1 indicates a perfectly accurate test; > 0.9 is excellent, 0.8–0.9 is good, 0.7–0.8 is acceptable, < 0.7 is considered poor, and ≤ 0.5 suggests that the test has no discriminatory ability36. Optimal anthropometric index cutoff values for predicting T2DM were chosen based on the most considerable value obtained from the Youden index (J = SE + Sp–1)37. Sensitivity, specificity, Youden index, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) were computed to assess the validity of the different anthropometric indices for predicting T2DM. The acceptable value of sensitivity and specificity of the screening tools adopted in this study was 70.0%38. Multivariate binary analysis was performed with T2DM as the dependent variable and age, sex, and anthropometric measurements as independent variables. Multicollinearity was checked using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF < 4), and none was detected. The goodness-of-fit test (Hosmer–Lemeshow Test) showed a good fit. A p-value of < 0.05 was used to indicate the significance level for all performed tests.

Results

General characteristics

Among the 396 adults included in the study, 201 (50.8%) were male and 195 (49.2%) were female. Of 396 adults, 267 (67.4%) had an education level beyond secondary, 182 (46.0%) were employed, and 297 (75.0%) were married. Eighty-two (20.7%) adults were smokers, and 146(36.9%) had a family history of DM. The median (IQR) for age, BMI, and WC were 45.0 (33.3‒55.8) years, 26.5 (22.5‒30.5) kg/m2, and 84.0 (73.8‒95.0) cm, respectively (Table 1).

The median values for BMI, WHtR, and WC were higher in females than in males (Table 2). Of the total adults, 107 (27.0%) were identified with T2DM. The median (IQR) of BMI, WC, and WHtR were significantly higher in adults with T2DM than in those without T2DM (Table 1). There was no correlation between BMI, WHtR, and HbA1c levels. There was a positive correlation between WC and HbA1c (Table 3).

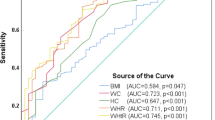

For the total adults (both males and females), BMI (AUC = 0.55, cutoff = 25.17 kg/m2, sensitivity = 0.68, specificity = 0.48, PPV = 32.6, NPV = 80.2), WHtR (AUC = 0.62, cutoff = 0.44, sensitivity = 0.74, specificity = 0.40, PPV = 34.4, NPV = 84.8), and WC (AUC = 0.63, cutoff = 79.28 cm, sensitivity = 0.78, specificity = 0.47, PPV = 35.3, NPV = 85.1) had poor predictability in detecting T2DM in adults (Table 4; Fig. 1).

When the results were dissected according to sex into males and females, for males, BMI (AUC = 0.59, cutoff = 23.0 kg/m2, sensitivity = 0.78, specificity = 0.41, PPV = 30.9, NPV = 81.7) and WHtR (AUC = 0.67, cutoff = 0.44, sensitivity = 0.67, specificity = 0.44, PPV = 33.9, NPV = 87.0) had poor predictability in detecting T2DM. WC had a slightly higher AUC (AUC = 0.65; cutoff = 80.5 cm; sensitivity = 0.80; specificity = 0.56, PPV = 36.8, NPV = 89.5) (Table 4).

In females, BMI (AUC = 0.50, cutoff = 25.3 kg/m2, sensitivity = 0.74, specificity = 0.39, PPV = 33.9, NPV = 77.9), WHtR (AUC = 0.56, cutoff = 0.45, sensitivity = 0.78, specificity = 0.39, PPV = 34.8, NPV = 81.7), and WC (AUC = 0.59, cutoff = 79.9 cm, sensitivity = 0.86, specificity = 0.31, PPV = 34.7, NPV = 84.3) had poor predictability in detecting T2DM in females’ adults (Table 4).

The univariate analysis indicated that increased age and WC were associated with T2DM. In multivariate analysis, being female (AOR 1.66, 95.0% CI 1.01‒2.73), increasing age (AOR 1.04, 95% CI 1.03‒1.06), and increased WC (AOR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01‒1.04) were associated with T2DM; BMI and WHtR were not associated with T2DM (Table 5).

Discussion

The current study showed that BMI, WC, and WHtR were significantly higher in females than in males. Over the quarter, (27.0%) of adults had T2DM, and females were at higher risk of having T2DM (AOR = 1.66). The higher prevalence of T2DM reported in our study concords with a global increase in T2DM, particularly in Africa1, and is supported by recently published studies evaluating the prevalence of T2DM among Sudanese adults23,24. Additionally, the increased life expectancy due to improved medication, improved awareness, lifestyle changes, and health facilities for early detection of T2DM might be contributing factors23. In the current study, females were at a higher risk of T2DM. A higher prevalence of T2DM among females was reported in previous studies conducted in Sudan, which showed that overweight, obesity, and T2DM were more prevalent in Sudanese females than males23,26. Rapid urbanization may enhance the prevalence of obesity in African countries39. Likewise, another study documented the pronounced obesity among women in developing countries40. Additionally, obese females tend to have lower rates of physical activity when compared to males41. Moreover, biological and social factors, levels of physical activity, sociocultural beliefs, and urbanization enhance the influence of gender differences40,42.

Our study revealed that BMI, WC, and WHtR, and their associated cut-off points, were significantly higher in female participants than in male participants. This is similar to results reported in recent publications from different African countries: South Africa19,20,21, Egypt18, and Ghana43. The higher cut-off points of the anthropometric indices seen among females in this study may be explained by the higher prevalence of obesity among females compared to males documented in different regions of Sudan, Khartoum, Northern, and River Nile States. Obesity in women (43.6%) is higher than in men (21.8%)25. In Eastern Sudan, women are 36.6%, men 21.6%28, and from Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, to the border of Egypt in Halfa city, females than males (36.7%) than men (17.6%)44. Not only Sudan but also adults from North Africa had a similar higher prevalence of overweight and obesity in females than in males45. Rapid urbanization may contribute to a higher prevalence of obesity in African countries39,46.

The current study showed that BMI, WC, and WHtR have limited discriminatory ability for detecting T2DM. A similar poor discriminatory range was reported in recently published clinical studies in African countries, such as Ethiopia, Cameroon, and Nigeria14,15,47. On the other hand, some recently published studies in Africa documented a wide range of discriminatory ability for these robust anthropometric indices in detecting T2DM among the African population18,19,21,43. The variation in the discriminatory ability of these indices may be explained by the fact that the distribution of fat tissue is the crucial factor in developing insulin resistance, independently of the degree of obesity, in particular, the ectopic fat deposition in the liver of obese patients is considered a significant marker of insulin resistance and glucose deregulation48. Moreover, T2DM is a multifactorial disease caused by oligo- and polygenic genetic and non-genetic factors arising from an imbalance between energy intake and output, as well as other lifestyle-related factors such as diet, regular exercise, and social beliefs49,50. This offers a better understanding of T2DM as a multifaceted disease, and its characteristics are essential for managing patients50. Identifying the best anthropometric measurement for predicting T2DM remains contentious. Several previous studies have shown that BMI was the best predictor of T2DM risk among adults compared to WC and WHtR, e.g., in Nigeria15, Egypt18, South Africa19,20,21, Jordon16, and China17. Analysis of biobank data from 450,000 British participants over 10 years revealed that BMI was the most significant predictor of T2DM among males, and WC was the most significant predictor among females46. In contrast, some African studies identified WC, WHtR, and BMI as the best anthropometric indices for detecting T2DM, in order16,20,21,43,48. Several studies worldwide reported no significant differences among the anthropometric indices (WC, WHtR, and BMI) and found them to be similar in predicting T2DM51,52,53,54,55. The outcome of these studies comparing the predictive power of anthropometric indices for T2DM has yielded conflicting results; hence, using a combination of these measurements is a robust predictor and preferable to using them individually9,56,57. Moreover, variations between the current study’s findings and those of other studies might be attributable to many factors, including population distinctiveness, cultural dynamics, ethnic groups, physical activities, sampling techniques, data-collection methods, and differences in operational definitions47. Additionally, IDF recommends the use of pre-specified cut-off points for BMI, WC, WHR, and WHtR to standardize comparisons within and between populations and ethnic groups, as the current cut-off points adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO) and IDF slightly underestimate the screening of T2DM among other ethnicities, especially in men1.

Our study demonstrated that anthropometric indices are poor screening tools for T2DM in resource-limited settings, particularly given the marked increase in T2DM prevalence in low- and middle-income countries. In fact, these indices remain practical screening tools in low-resource settings despite limited accuracy demonstrated in this study. The result obtained in our study might be explained by the fact that some participants were diagnosed and on lifestyle management or anti diabetic medications that influence obesity and ultimately affect the anthropometric indices58,59. Additionally, T2DM is type 2 diabetes, which is multifaceted, 49 and genetic differences among racial/ethnic groups could also provide some explanation for the results obtained in this study60. However, these anthropometric indices are simple, easily obtainable, low-cost, noninvasive measures of population screening and early detection of malnutrition. 61,62 Additionally, traditional measures like BMI, WC, and WHtR, as well as novel indices such as novel [a-body shape index (ABSI), abdominal volume index (AVI), body adiposity index (BAI), body roundness index (BRI), conicity index (CI), and Clinical Universidad de Navarra-Body Adiposity Estimator (CUN-BAE)] anthropometric indices, had similar performance in detecting T2DM20,63,64. Moreover, the traditional anthropometric indices have a significant ability to predict the incidence of T2DM over the years65 assess glycemic control66, screen for metabolic syndrome in non-overweight/obese subjects67 the current cardiometabolic risk factors and over 10 years among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus68,69, and all-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD)-related mortality in this group of patients70. Interestingly, anthropometric indices may mitigate the burden of T2DM and its complications in low- and middle-income countries12.

This study’s limitations include reliance on experience from a single center and the fact that diet, exercise, stress, treatment, and genetics are known confounders of anthropometric measures of obesity and T2DM. Moreover, we used HbA1c alone as the diagnostic tool for T2DM. Additionally, methodological constraints, such as selection bias risk and potential confounding factors, may bias associations.

Conclusion

In the current study, BMI, WC, and WHtR were poorly predictive of T2DM in adult Sudanese. Combined indices or alternative metrics (e.g., body adiposity index or body roundness index) might provide better discrimination. Moreover, we encourage further studies to evaluate these anthropometric indices in Sudan to detect T2DM.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available (because the manuscript is still under peer review), but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- MUAC:

-

Mid-upper arm circumference

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- WHtR:

-

Waist-height ratio

- WHR:

-

Waist–hip ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- ROC:

-

Receiver-operating characteristic curve

References

Magliano, D. J., Boyko, E. J. & IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th edition scientific committee. IDF DIABETES ATLAS [Internet], 10th edn. (International Diabetes Federation, 2021). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK581934/

Heald, A. H. et al. Estimating life years lost to diabetes: outcomes from analysis of National diabetes audit and office of National statistics data. Cardiovasc. Endocrinol. Metab. 9, 183–185 (2020).

Sun, H. et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 183, 109119 (2022).

Ogurtsova, K. et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults for 2021. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 183, 109118 (2022).

Gedebjerg, A. et al. Prevalence of micro- and macrovascular diabetes complications at time of type 2 diabetes diagnosis and associated clinical characteristics: A cross-sectional baseline study of 6958 patients in the Danish DD2 cohort. J. Diabetes Complications. 32, 34–40 (2018).

Bos, M. & Agyemang, C. Prevalence and complications of diabetes mellitus in Northern Africa, a systematic review. BMC Public. Health. 13, 387 (2013).

Nathan, D. M. The diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study at 30 years: overview. Diabetes Care. 37, 9–16 (2014).

Dabelea, D. et al. Association of type 1 diabetes vs type 2 diabetes diagnosed during childhood and adolescence with complications during teenage years and young adulthood. JAMA 317, 825–835 (2017).

Guh, D. P. et al. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public. Health. 9, 88 (2009).

Tchernof, A. & Després, J. P. Pathophysiology of human visceral obesity: an update. Physiol. Rev. 93, 359–404 (2013).

Zalesin, K. C., Franklin, B. A., Miller, W. M., Peterson, E. D. & McCullough, P. A. Impact of obesity on cardiovascular disease. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 37, 663–684 (2008).

Simmons, S. S. Strikes and gutters: biomarkers and anthropometric measures for predicting diagnosed diabetes mellitus in adults in low- and middle-income countries. Heliyon 9, e19494 (2023).

Lam, B. C. C., Koh, G. C. H., Chen, C., Wong, M. T. K. & Fallows, S. J. Comparison of body mass index (BMI), body adiposity index (BAI), waist circumference (WC), waist-To-Hip ratio (WHR) and waist-To-Height ratio (WHtR) as predictors of cardiovascular disease risk factors in an adult population in Singapore. PLoS One. 10, e0122985 (2015).

Mbanya, V. N., Kengne, A. P., Mbanya, J. C. & Akhtar, H. Body mass index, waist circumference, hip circumference, waist-hip-ratio and waist-height-ratio: which is the better discriminator of prevalent screen-detected diabetes in a Cameroonian population? Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 108, 23–30 (2015).

Muhammad Yakubu, I., Kaoje, S. & Jabbe, Y. T. & Abdullahi Abubakar, A. Best anthropometric predictors of fasting blood sugar, prediabetes, and diabetes. Diabetes Updat 6, (2020).

Alkhalidy, H. et al. Obesity measures as predictors of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases among the Jordanian population: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 12187 (2021).

Bai, K., Chen, X., Song, R., Shi, W. & Shi, S. Association of body mass index and waist circumference with type 2 diabetes mellitus in older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 22, 489 (2022).

Nesnawy, S., Gamal, M., Abd-Elkhalik, L. F., Elbanna, E. Y., Taha, H. & M. & Determining the best predictive anthropometric assessment tool for Type-2 diabetes mellitus: A case-control study in Egyptian adults. Egypt. J. Heal Care. 13, 1498–1510 (2022).

Sekgala, M. D., Sewpaul, R., Opperman, M. & McHiza, Z. J. Comparison of the ability of anthropometric indices to predict the risk of diabetes mellitus in South African males: SANHANES-1. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 3224 (2022).

Sekgala, M. D., Sewpaul, R., Kengne, A. P., Mchiza, Z. & Peer, N. Clinical utility of novel anthropometric indices in identifying type 2 diabetes mellitus among South African adult females. BMC Public. Health. 24, 2676 (2024).

Castle, A. C. et al. Identifying sex-specific anthropometric measures and thresholds for dysglycemia screening in an HIV-endemic rural South African population. PLOS Glob Public. Heal. 3, e0001698 (2023).

Bushara, S., Noor, S., Ibraheem, A. A., Elmadhoun, W. & Ahmed, M. Prevalence of and risk factors for hypertension among urban communities of North sudan: detecting a silent killer. J. Fam Med. Prim. Care. 5, 605 (2016).

Omar, S. M., Musa, I. R., ElSouli, A. & Adam, I. Prevalence, risk factors, and glycaemic control of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Eastern sudan: a community-based study. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 10, 2042018819860071 (2019).

Elmadhoun, W. M., Noor, S. K., Ibrahim, A. A. A., Bushara, S. O. & Ahmed, M. H. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and its risk factors in urban communities of North sudan: Population-based study. J. Diabetes. 8, 839–846 (2016).

Ali, Y. A., Almobarak, A. O., Awadalla, H., Elmadhoun, W. M. & Ahmed, M. H. Obesity among Sudanese adults with diabetes: a population-based survey. Ann. Transl. Med. 5, 252–252 (2017).

Omar, S. M., Taha, Z., Hassan, A. A., Al-Wutayd, O. & Adam, I. Prevalence and factors associated with overweight and central obesity among adults in the Eastern Sudan. PLoS One. 15, e0232624 (2020).

Keller, M., Svensson, S. I. A., Rohde-Zimmermann, K., Kovacs, P. & Böttcher, Y. Genetics and epigenetics in obesity: what do we know so far? Curr. Obes. Rep. 12, 482 (2023).

Ratsavong, K. et al. Waist-to-Height ratio as a key predictor for diabetes and hypertension in Lao PDR National health survey. Asia-Pac. J. Public. Heal. 37, 35–42 (2025).

Kengne, A. P. et al. Trends in obesity and diabetes across Africa from 1980 to 2014: an analysis of pooled population-based studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 1421–1432 (2017).

Peer, N., Kengne, A. P., Motala, A. A. & Mbanya, J. C. Diabetes in the Africa region: an update. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 103, 197–205 (2014).

Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 13, S31–S34. https://doi.org/10.4103/sja.SJA_543_18 (2019).

Magliano, D. J., Boyko, E. J. & committee, I. D. A. 10th edition scientific. IDF DIABETES ATLAS, 54–55 (2021).

World Health Organization. Physical status : the use of and interpretation of anthropometry, report of a WHO expert committee. (2025). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241208546, acessed 5/11/.

Bashir, A. O., Elimam, M. A., Elimam, M. A. & Adam, I. Snoring is associated with hypertension and diabetes mellitus among adults in North sudan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public. Health. 24, 974 (2024).

Bujang, M. A. & Baharum, N. Sample size guideline for correlation analysis. World J. Soc. Sci. Res. 3, 37 (2016).

Nahm, F. S. Receiver operating characteristic curve: overview and practical use for clinicians. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 75, 25–36 (2022).

Fluss, R., Faraggi, D. & Reiser, B. Estimation of the Youden index and its associated cutoff point. Biom J. 47, 458–472 (2005).

Glascoe, F. P. Screening for developmental and behavioral problems. Ment Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 11, 173–179 (2005).

Sartorius, B., Veerman, L. J., Manyema, M., Chola, L. & Hofman, K. Determinants of obesity and associated population Attributability, South africa: empirical evidence from a National panel Survey, 2008–2012. PLoS One. 10, (2015).

Kanter, R. & Caballero, B. Global gender disparities in obesity: a review. Adv. Nutr. 3, 491–498 (2012).

Alsulami, S. et al. Obesity prevalence, physical activity, and dietary practices among adults in Saudi Arabia. Front. Public. Heal. 11, 1124051 (2023).

Wardle, J. et al. Gender differences in food choice: the contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann. Behav. Med. 27, 107–116 (2004).

Frank, L. K. et al. Measures of general and central obesity and risk of type 2 diabetes in a Ghanaian population. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 18, 141–151 (2013).

Ahmed, M. H. et al. Prevalence and trends of obesity among adult Sudanese individuals: population based study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 11, S963–S967 (2017).

Toselli, S. et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in adults from North Africa. Eur. J. Public. Health. 24 (Suppl 1), 31–39 (2014).

Mbanya, J. C., Assah, F. K., Saji, J. & Atanga, E. N. Obesity and type 2 diabetes in Sub-Sahara Africa. Curr Diab Rep 14, (2014).

Woldegebriel, A. G. et al. Effectiveness of anthropometric measurements for identifying diabetes and prediabetes among civil servants in a regional city of Northern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. J. Nutr. Metab. (2020).

D’Adamo, E. & Caprio, S. Type 2 diabetes in youth: epidemiology and pathophysiology. Diabetes Care 34 Suppl 2, (2011).

Hansen, T. Type 2 diabetes mellitus–a multifactorial disease. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Sect. D Med. 57, 544–549 (2002).

Pearson, E. R. Type 2 diabetes: a multifaceted disease. Diabetologia 62, 1107–1112 (2019).

Wang, Y., Rimm, E. B., Stampfer, M. J., Willett, W. C. & Hu, F. B. Comparison of abdominal adiposity and overall obesity in predicting risk of type 2 diabetes among men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 81, 555–563 (2005).

Abe, M. et al. Comparison of body mass index and waist circumference in the prediction of diabetes: A retrospective longitudinal study. Diabetes Ther. 12, 2663–2676 (2021).

Wu, J. et al. A novel visceral adiposity index for prediction of type 2 diabetes and Pre-diabetes in Chinese adults: A 5-year prospective study. Sci. Rep 7, (2017).

Wei, J., Liu, X., Xue, H., Wang, Y. & Shi, Z. Comparisons of visceral adiposity index, body shape index, body mass index and waist circumference and their associations with diabetes mellitus in adults. Nutrients 11, (2019).

Fujita, M., Sato, Y., Nagashima, K., Takahashi, S. & Hata, A. Predictive power of a body shape index for development of diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia in Japanese adults: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 10, e0128972 (2015).

De Koning, L. et al. Anthropometric measures and glucose levels in a large multi-ethnic cohort of individuals at risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 53, 1322–1330 (2010).

Chiang, J. K. & Koo, M. Lipid accumulation product: a simple and accurate index for predicting metabolic syndrome in Taiwanese people aged 50 and over. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord 12, (2012).

Jagadeesh Chandra Prasad, P., Lavanya, Y., Nikhileswar Reddy, P., Shameera Banu, D. & Rajavardhana, T. Investigating the connection between diabetes drugs and weight loss in patients with type II diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health. 35, 102135 (2025).

Committee, A. D. A. P. P. et al. 8. Obesity and weight management for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of care in Diabetes–2025. Diabetes Care. 48, 167–S180 (2025).

Lutsey, P. L., Pereira, M. A., Bertoni, A. G., Kandula, N. R. & Jacobs, D. R. Interactions between Race/Ethnicity and anthropometry in risk of incident diabetes: the Multi-Ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 172, 197 (2010).

Costo-Muriel, C. et al. Association of subclinical carotid atherosclerosis assessed by High-Resolution ultrasound with traditional and novel anthropometric indices. Curr Probl. Cardiol 48, (2023).

Corrêa, M. M., Tomasi, E., Thumé, E., de Oliveira, E. R. A. & Facchini, L. A. Waist-to-height ratio as an anthropometric marker of overweight in elderly Brazilians. Cad Saude Publica 33, (2017).

Perona, J. S. et al. Waist circumference and abdominal volume index are the strongest anthropometric discriminators of metabolic syndrome in Spanish adolescents. Eur. J. Clin. Investig 49, (2019).

Khan, S. H., Shahid, R., Fazal, N. & Ijaz, A. Comparison of various abdominal obesity measures for predicting metabolic Syndrome, Diabetes, Nephropathy, and dyslipidemia. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 29, 1159–1164 (2019).

Hafezi, S. G. et al. Prediction of the 10-year incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus based on advanced anthropometric indices using machine learning methods in the Iranian population. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 214, (2024).

Oumer, A. et al. Waist-to-hip circumference and waist-to-height ratio could strongly predict glycemic control than body mass index among adult patients with diabetes in ethiopia: ROC analysis. PLoS One 17, (2022).

Wu, L. et al. Novel and traditional anthropometric indices for identifying metabolic syndrome in non-overweight/obese adults. Nutr. Metab. (Lond) 18, (2021).

Azeez, T. Anthropometric indices as predictors of 10-year cardiovascular risk among Sub-Sahara Africans with type 2 diabetes. J. Cardiovasc. Med. Cardiol. 8, 072–078 (2021).

Golabi, S., Ajloo, S., Maghsoudi, F., Adelipour, M. & Naghashpour, M. Associations between traditional and non-traditional anthropometric indices and cardiometabolic risk factors among inpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. J. Int. Med. Res 49, (2021).

Lim, R. B. T. et al. Anthropometrics indices of obesity, and all-cause and cardiovascular disease-related mortality, in an Asian cohort with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 41, 291–300 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.R.M. and I.A. conceived the study; I.R.M., O.E.O., and I.A. supervised the work, guided the analysis, and critically reviewed the manuscript; O.E.O., A.M.K., and I.A. prepared the analysis plan, performed the data analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the Health Authority in Almatamah, Sudan, provided ethical approval of the study (reference number #9, 2021). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Musa, I.R., Osman, O.E., Khair, A.M. et al. The ability of anthropometric indices in detecting type 2 diabetes mellitus in Sudanese adults: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 45513 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29989-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29989-x