Abstract

Prior studies have validated a novel index, designated as the cholesterol-HDL-glucose (CHG) index, which has emerged as a promising biological marker for abnormalities in lipid metabolism and insulin resistance. At present, however, there is an absence of data demonstrating its capacity to predict the risk of CMD. The objective of this study is to evaluate the comparative efficacy of the CHG index and the triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index in predicting cardiovascular metabolic disease (CMD) risk. This study was conducted on a cohort of 6471 participants from CHARLS. A binary logistic regression analysis was performed using R software, utilizing restricted cubic spline techniques to evaluate the dose–response relationship. The evaluation of predictive performance was carried out through the use of receiver operating characteristic curves. To quantify the improvements in predictive capability, two important indices were calculated: Net Reclassification Improvement and Integrated Discrimination Improvement were used to assess the enhancements in our predictive models. Finally, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. An increase in each unit of CHG and TyG was associated with a 83% and 46% rise in the risk of CMD, respectively. The occurrence of CMD in the highest quartile for the CHG index (OR = 1.69, 95% CI 1.42–2.00) increased by 69%, while the TyG index (OR = 1.61, 95% CI 1.36–1.92) exhibited an increase of 61%. A linear correlation was identified between the two indices and the risk of CMD. The predictive capabilities and incremental predictive value of both indices were found to be analogous. The CHG index exhibited a substantial linear positive correlation with CMD, demonstrating assessment capabilities for CMD risk that were analogous to those of the TyG index.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiometabolic diseases (CMD) are a global public health concern1. With significant changes in economic development and lifestyle, the prevalence of these diseases is rapidly increasing in China2,3. CMD refers to a group of disorders that initially manifest as insulin resistance (IR), advancing to metabolic syndrome and prediabetes, and eventually leading to hypertension, type 2 diabetes (T2D), a range of cardiovascular diseases (CVD), and stroke4. The risk factors for this disease include unhealthy lifestyle choices (e.g., lack of exercise, low dietary fiber intake, alcohol consumption, smoking, and poor diet), hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemi4,5.The identification of high-risk groups for CMD at an early stage, along with the execution of relevant preventive strategies, is essential for reducing the detrimental effects tied to CMD6,7,8. Consequently, recent studies have focused on identifying biomarkers that can facilitate the early detection of CMD.

It has been established that IR is a critical component in the pathogenesis of CMD4,5,6,7,8,9. Therefore, fasting plasma glucose(FPG) has been identified as a significant indicator for CMD10. However, the role of lipids should not be underestimated11. Consequently, the triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index, which integrates both triglycerides and glucose levels, has been frequently utilized to anticipate various associated diseases12,13. A study based on the NHANES database from 2001 to 2018 indicates that the TyG index is positively correlated with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality. An increase in the TyG index by one unit was associated with a 16% rise in the probability of all-cause mortality (HR = 1.16, 95% CI 1.03–1.31, P = 0.017). Similarly, cardiovascular mortality exhibited a 39% surge (HR = 1.39, 95% CI 1.14–1.71, P = 0.001)14. The predictive value of the TyG index in metabolic-related diseases has been affirmed by numerous studies15. A recent study has validated a novel biomarker, designated as the cholesterol-HDL-glucose (CHG) index, which has been shown to possess superior diagnostic efficacy for T2D when compared to the TyG index16. Additionally, the CHG index has been observed to demonstrate a diagnostic value for CVD that is comparable to that of the TyG index. However, a distinguishing feature of the CHG index is its linear relationship, which differs from that observed in the TyG index17. It has been established that, in addition to the established framework of IR, the progression of CMD is increasingly recognized as being driven by oxidative stress18. The various components of the CHG index have been demonstrated to be effective promoters of systemic oxidative stress. This provides a rationale for the potential association between CHG and CMD. However, the extant literature has yet to investigate the comparison of the CHG index and the TyG index regarding their diagnostic effectiveness for CMD, in order to determine if the CHG index may be a superior option for diagnosing CMD compared to the TyG index.

This research intends to employ a comprehensive nationwide project known as the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) to evaluate the predictive efficacy of the CHG and TyG indices concerning CMD within China’s middle-aged and elderly demographic. The aim of this study is to: First, it will evaluate the predictive capability of the CHG index for broader composite cardiovascular disease outcomes, including multiple components such as diabetes, hypertension, and stroke, in middle-aged and elderly Chinese populations. Second, it will directly compare the CHG index with the well-established TyG index to determine if the CHG index offers any advantages. These evaluations provide more comprehensive and universally applicable evidence to support the clinical application of the CHG index. Compared to existing studies, this research features broader outcome measures, a specific target population, and a longer follow-up period.

Method

Research population

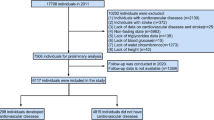

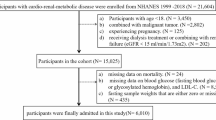

The information utilized in this research was obtained exclusively from the CHARLS project, which has been collecting data since 2011 from more than 17,000 individuals throughout China. This encompasses fundamental demographic traits of the participants and their families, along with details regarding intra-family transfer payments, health conditions, and additional related factors13,19.The baseline data for this project began in 2011, with follow-up data released every 2–3 years. To date, the fifth follow-up data for the year 2020 has been publicly released. The oversight of this project is managed by Peking University, which has obtained approval from its Medical Ethics Committee (IRB00001052-11015) and adheres to the standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants have provided their signatures on the informed consent forms. For additional details, please refer to the website http://charls.pku.edu.cn/. In 2011, the collection of blood data from participants engaged in the project took place, with trained personnel obtaining fasting venous blood samples from individuals who had refrained from eating for a minimum of 12 hours. All biomedical testing protocols were meticulously carried out by certified specialists, and the samples were maintained at optimal concentrations at 4 °C before being promptly dispatched to the Clinical Testing Center at You’anmen, Capital Medical University (Beijing Central Laboratory) for comprehensive diagnostic evaluation13,20,21. The present study constitutes a national cohort study. The data from respondents in 2011 (Wave 1) were selected as the baseline, with individuals under the age of 45 and those with a prior diagnosis of CMD (diabetes, stroke, hypertension, and heart problems) at the time of the interview excluded. The baseline data was associated with the corresponding ID numbers in the follow-up data (2020, Wave 5), and any missing data related to CMD was excluded. (Figure 1)

Assessment of the CHG index and TyG index

Assessment of new-onset CMD

This study used the baseline data from the CHARLS database from 2011(Wave1), and after a 10-year follow-up period, the data from 2020(Wave5) was used as follow-up data. These follow-up cohorts were linked together through ID numbers.The information regarding CMD was derived from the questionnaire “Has a doctor diagnosed you with any of the following conditions, which you should read one at a time?” If the respondent answered “yes,” the interviewer would inquire about each specific condition, allowing the respondent to choose “yes” or “no” for each question. We primarily focus on four key questions: the number one question pertains to “hypertension,” the number three question involved “diabetes or hyperglycemia,” the number seven question targeted “myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, angina, congestive heart failure, or other heart troubles,” and the number eight question related to “stroke.” If the patient answered “no” to all four of these questions, it can be determined that the patient did not have CMD. Conversely, if the patient answered “yes” to any one or more of these four questions, they were classified as having CMD. Cases that had already been diagnosed with CMD were excluded from the study in baseline data,and the research subjects were defined as the newly diagnosed CMD population up to the follow-up cutoff in 202024.

Assessment of covariates

The present study incorporated a range of demographic, lifestyle, and blood biochemical factors as covariates. These included gender, age, marital status (married/single), education level (middle school and above/middle school and low), smoking habits (yes/no), alcohol consumption (yes/no), and several parameters from venous blood tests. The body mass index (BMI) is calculated by dividing the weight (in kilograms) by the square of the height (in meters squared)10. .

Statistical analysis

Initially, normality tests were performed on continuous variables. The subjects that satisfied the criteria for a normal distribution were reported as means, accompanied by their respective standard deviations (SD). Conversely, for variables that failed to exhibit a normal distribution, medians were indicated with interquartile ranges (IQR). Categorical variables were represented as percentages.For comparisons between groups of normally distributed variables, the t-test was employed; for variables with a skewed distribution, the Mann–Whitney U test was utilized; and for categorical variables, chi-square tests were applied. A comprehensive analysis was conducted using a binary logistic regression model to explore the variations in the relationships between the CHG index and the TyG index in relation to the incidence of newly developed CMD. To assess multicollinearity among independent variables, we calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF) for all models. Conventional wisdom dictates that a VIF less than 5 indicates an acceptable level of multicollinearity, a VIF less than 10 indicates a moderate level, and a VIF greater than 10 suggests that severe multicollinearity may affect the stability of parameter estimates. Furthermore, we conducted stratified multivariable regression analyses to evaluate subgroups, as well as interaction analyses. We employed the restricted cubic spline (RCS) method as a means to visually represent the dose–response relationship between the CHG index and the TyG index with the incidence of new-onset CMD. In order to compare the incremental predictive values of both indices, the incremental predictive models of the CHG index and the TyG index were integrated into the traditional model. The objective of this study was to determine whether the predictive efficacy for CMD could be improved by including these relevant indices alongside traditional risk factors. To this end, a comparison was made between the two sets of models. The values for were computed as follows: Net Reclassification Improvement (NRI) and Integrated Discrimination Improvement (IDI). To evaluate the models’ predictive performance after adjusting for covariates, adjusted ROC curves were generated using multivariable logistic regression models. This analysis was performed using the pROC package (version 1.19.0.1) in R, and for each model the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated with 95% confidence intervals using DeLong’s method. The optimal cut-off points were determined using the Youden index. The corresponding sensitivity and specificity at the optimal cut-off point are reported for each model. Finally, separate sensitivity analyses were conducted on each component of CMD (diabetes, stroke, heart attack, and hypertension). The results were validated using the E-value method and Rosenbaum sensitivity analysis to ensure the robustness of the findings. All statistical operations were executed using R version 4.5.1 (2025–06-13 ucrt). For the missing data, the mice package was employed for multiple imputations. During this process, we employed a range of packages, including forestploter, nortest, rms, tidyverse, and ggplot2. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate significant statistical significance.

Results

Participant baseline characteristics

This study included 6471 individuals. By the conclusion of the 10-year follow-up in 2020, 1515 participants were identified as having CMD, which resulted in an incidence rate of 23.41%. The median age of the affected population was significantly higher at 57 years compared to 55 years in the non-affected group, with a higher prevalence among females than males.As shown in Table 1, the proportion of single individuals in the CMD group was significantly higher. Additionally, this group exhibited higher levels in indicators such as BMI, TyG, triglyceride(TG),C-reactive protein(CRP), CHG and so on, apart from having lower levels of HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) compared to the non-CMD population,all P < 0.05.In addition, we conducted a quartile analysis of the CHG and TyG indices.The findings indicated a significant correlation between higher TyG index levels and an increased proportion of females, as well as a greater number of smokers and drinkers, elevated levels of total cholesterol (TC), BMI, FPG and TG, alongside a reduction in HDL-C levels and a higher incidence of CMD, with all P values being less than 0.05. (Table S1).The quartile analysis results of the CHG index indicated that elevated CHG levels were significantly associated with an increase in the number of drinkers, a rise in urban population, and higher levels of TC, BMI, FPG, TG, LDL-C, and CRP, as well as a decrease in HDL-C levels and an increased incidence of CMD,all P < 0.05, (Table S2).

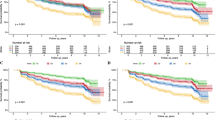

Association between CHG and TyG indices and new-onset CMD

Table 2 illustrates that significant correlations exist between both the CHG index and the TyG index with CMD, where the correlation for the CHG index is marginally greater than that of the TyG index.In the fully adjusted model, for each one-unit increase in CHG, the risk of CMD increases by 83%, while a one-unit increase in TyG corresponds to a 46% increase in the risk of CMD. In Model 3, when comparing Group Q4 to Group Q1, the occurrence of CMD for the CHG index rose by 69% (OR = 1.69, 95%CI 1.42–2.00, P < 0.001), whereas the TyG index demonstrated an increase of 61% (OR = 1.61, 95%CI 1.36–1.92, P < 0.001).Figu’re. 2 illustrates the RCS curves of the CHG index and the TyG index . The results indicated that after adjusting the full model (Model 3), both the TyG index (Poverall < 0.001, Pnon−linear = 0.179) and the CHG index (Poverall < 0.001, Pnon−linear = 0.126) exhibited significant linear relationships with the incidence of CMD.The results of the multicollinearity diagnosis indicated that the VIF values for all models were significantly below the critical value of 10. (Table S3,Figure S1).

Predictive value of CHG and TyG indices for newly diagnosed CMD

Figure 3 illustrates the ROC curves of the CHG index and the TyG index along with their AUC values. The results indicated that the AUC of both the CHG index and the TyG index was equal, both being 0.573. From the information in Table 3, it can be observed that the accuracy of the CHG index (Accuracy = 59.9%) was slightly higher than that of the TyG index (Accuracy = 50.4%).The DeLong test demonstrated that the discrepancy in the AUC of the CHG and TyG indices was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The reasons for the reduced AUC of the TyG and CHG indices in the context of CMD may be attributed to the following factors: 1. The construct of CMD emerges from the interplay of multiple genetic and environmental factors, rendering a solitary biomarker an inadequate representation of its intricacy. 2. A substantial overlap existed in the distribution of TyG and CHG between the case and control groups, thereby impeding their discriminatory capacity.(Figure S2-C). We then constructed adjusted ROC curves to evaluate the predictive capabilities of each indicator and model, accounting for covariates. As shown in Figure S2-A, the baseline model adjusted for BMI, age, gender, smoking status and alcohol consumption status had an AUC value of 0.600 (95% CI 0.584–0.616, cut-off: 0.233, sensitivity: 0.558, specificity: 0.609). Adding the TyG and CHG indices to the baseline model increased the adjusted AUC to 0.616 (95% CI 0.600–0.632, cut-off: 0.237, sensitivity: 0.554, specificity: 0.628), and incorporating the full model with 11 parameters yielded an AUC of 0.619(95% CI 0.603–0.636, cut-off: 0.235, sensitivity: 0.568, specificity: 0.618). These results suggest that, even after comprehensive adjustment for demographic and lifestyle factors, both indices modestly improve the ability to discriminate between individuals at risk of CMD. Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) demonstrated that the addition of CHG and TyG provided incremental value, supporting their use in risk assessment models, particularly at low to moderate decision thresholds, and suitable for early intervention decisions.(Figure S2-B).We then calibrated the model, and the results indicated that the inclusion of the CHG or TyG index improved the calibration of the model, making its predictions more reliable. (Table S4, Figure S3).

Incremental predictive values of CHG index and TyG index for newly diagnosed CMD

The conventional model we evaluated was the fully adjusted version (Model 3), which included both the CHG index and the TyG index to determine if they improve the predictive capacity for CMD. The results of categorical NRI (0.10, 0.20, and 0.30) obtained using the bootstrap method with 1000 iterations were follows. The results indicated that the overall improvement in predictive value with the CHG index [IDI = 0.97(95% CI 0.51–1.58),P < 0.001] was slightly superior to that of the TyG index [IDI = 0.88(95% CI 0.47–1.41)P < 0.001], while the reclassification ability of the TyG index [NRI = 6.89(95% CI 4.10–10.00),P < 0.001] was marginally higher than that of the CHG index [NRI = 6.12(95% CI 2.92–9.24),P < 0.001]. (Table 4). Figure 4 depicts the ROC curve demonstrating the enhanced prediction of CMD incidence following the inclusion of the CHG and TyG indices, along with the visual outcomes of their IDI. However, the results of the categorical NRI suggested that this improvement was not fully captured within the predefined fixed risk threshold framework. The results of the continuous NRI (significantly positive) indicated that the new model consistently improved risk prediction overall. This did not negate the incremental value of the model; rather, it emphasized that continuous NRI may be more robust when evaluating such improvements. (Table S5, Figure S4).

The respective ROC curve for the incremental predictive value of the base model and the base model plus CHG and TyG indices for predicting the incidence of CMD and the distribution map of IDI and its 95%CI .(A) represents ROC curve of base model vs base model plus CHG and TyG indices; (B) represents the distribution map of IDI for TyG; (C) represents the distribution map of IDI for CHG . (D) represents the Comparison of different model performance; E and F Reclassification Heatmap of Base Model vs Base + CHG by Predicted Risk Categories in Events(E) and Non-events(F).

Subgroup analysis

To clarify whether the aforementioned correlation results were influenced by other factors such as age, gender, BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption and education and so on, we conducted a subgroup analysis. Further interaction tests indicated that no significant interactions were found between the subgroups and the CHG and TyG indices, all P > 0.05 (Fig. 5).

Sensitivity analysis

To evaluate the reliability of the research results, we performed an E-value analysis. The findings suggested that the strength of the CHG index’s robustness surpassed that of the TyG index.The increase in CMD risk by approximately 43% associated with the CHG index was robust. and the CHG indicators yield E values for the three models of 2.199, 2.200, and 2.222, while the minimum E values were 1.973, 1.973, and 1.992. This indicated that in order for the observed associations to become statistically non-significant, an unmeasured confounding factor must be concurrently associated with both CHG and newly developed CMD, with each associated risk ratio (RR) being at least 2.199, 2.200, and 2.222 respectively. Similarly, the E values given by the TyG index for the three models were 1.796, 1.808, and 1.813, while the minimum E values were 1.659, 1.668, and 1.673, respectively. (Table S6).The Rosenbaum sensitivity analysis further validated the robustness of our research findings(Figure S5).In addition, we conducted a separate sensitivity analysis of the components of CMD(diabetes stroke,heart attack and hypertension), and the results indicated that the CHG and TyG indices have the strongest and most consistent association with type 2 diabetes, which aligns with their biological mechanisms as surrogate markers of insulin resistance. There is also a significant and robust positive correlation with hypertension. However, the association with stroke and myocardial infarction is much weaker. (Table S7).

Discussion

Previous research has established that there is a connection between the TyG index and several type of CMD. A study conducted by Yanjuan Chen and colleagues revealed a notable link between the TyG index and CMD (HR = 1.41, 95% CI 1.27–1.57), diabetes (HR = 1.51, 95% CI 1.34–1.70), stroke (HR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.22–1.51), and coronary artery disease (HR = 1.35, 95% CI 1.22–1.50). Moreover, the research indicated a linear dose–response association with the risk of CMD (P_non−linear = 0.358)25. In our study, the likelihood of CMD increased by 46% for every unit increase in TyG. In the fully adjusted model, the Q4 group exhibited a notable positive association with the TyG index of 61% compared to the Q1 group (OR = 1.61, 95% CI 1.36–1.92, P < 0.001). Additionally, a significant linear dose–response relationship concerning the risk of CMD was observed (Poverall < 0.001, Pnon−linear = 0.179). However, the existence of this positive linear relationship remains controversial. Research by Amirhossein Yadegar and his colleagues found that, in individuals with T2D, the relationship between the TyG index and the risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) was characterised by a U-shaped curve rather than a linear dose–response pattern. This suggests that extremely low or exceedingly high TyG levels are associated with a higher likelihood of CAD than moderate levels. It is well understood that a high level of TyG increases the risk of CAD due to elevated blood glucose and lipids. In contrast, the authors suggested that low TyG levels may lead to sympathetic nervous system activation, increased adrenaline and vasoconstriction due to hypoglycaemia. However, a consensus has yet to be reached on this matter26. A separate study confirmed a linear correlation between obesity status, as indicated by the TyG index, and the likelihood of adverse long-term cardiovascular outcomes in young and middle-aged individuals in the United States27. Therefore, the authors speculate that the correlation between the TyG index and CMD is indisputable; however, the strength and type of this association may also be influenced by the population of the sample, disease classification, and certain confounding factors. Further validation through large-scale global multicenter studies with unified standards is needed.

This research presents CHG as a new marker and evaluates its effectiveness in diagnosing CMD, compared to the TyG index, among the middle-aged and elderly Chinese population. Previous research on the CHG index is scarce. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, it was first applied by Amin Mansoori et al., who utilized the CHG index for the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, demonstrating its diagnostic value that surpasses that of the TyG index16. As CHG includes the TC to HDL ratio, this factor has been confirmed as an important predictor of type 2 diabetes28,29, reflecting the significant impact of obesity and dyslipidaemia on the development of the condition30,31. In contrast, although the fasting FPG utilized in the TyG index is recognized as a risk element for T2D32, it is considerably affected by multiple influences, including diet and medication.Thanks to its potential to better reflect glycemia-driven microvascular damage, the CHG index demonstrated a diagnostic value distinct from the TyG index regarding diabetic microvascular complications33. Another study focused on diagnosing CVD found that the CHG index considers not only lipid parameters, but also blood glucose levels. Cox regression analysis showed that the CHG index had a higher hazard ratio (HR) than the TyG index, suggesting that the CHG index might be a better predictor of CVD risk17. Therefore, compared to other indices, the CHG index is a simple and cost-effective measure that serves as a suitable indicator for identifying IR and abnormal lipids metabolism which also demonstrates good economic effects. In a fasting condition, CHG is obtained and does not necessitate the evaluation of the Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) or insulin levels, which makes it an effective option for evaluating insulin resistance and dyslipidemia16,17. Furthermore, oxidative stress and inflammatory responses are also involved in the progression of CMD34,35.Studies show a link between high TyG index levels and diseases characterized by pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative conditions36. Although current research on the relationship between the CHG index and inflammation in vivo is still insufficient, it can be inferred that this correlation is inevitable17. This is because, compared to the TyG index (which is based on triglycerides and blood glucose), the CHG index integrates a broader range of metabolic pathways. These include: 1.glucose metabolism homeostasis; 2. atherogenic lipid burden(through total cholesterol, which is upregulated in states of energy surplus); and 3. impaired reverse cholesterol transport capacity (through high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, which decreases in states of insulin resistance and inflammation).

Moreover, our research is the inaugural study to evaluate the predictive significance of the CHG index in comparison to the TyG index for CMD. Although their AUCs are equal, the accuracy of the CHG index was higher than that of the TyG index. Furthermore, under the premise of fully adjusting the model as a conventional model, we first calculated the NRI and IDI to compare the incremental predictive value of the CHG index and the TyG index for CMD. The results showed that the predictive value of the CHG index [IDI = 0.97 (95% CI 0.51–1.58), P < 0.001] was slightly superior to that of the TyG index [IDI = 0.88 (95% CI 0.47–1.41), P < 0.001]. However, the reclassification ability of the TyG index [NRI = 6.89 (95% CI 4.10–10.00), P < 0.001] was slightly higher than that of the CHG index [NRI = 6.12 (95% CI 2.92–9.24), P < 0.001].Due to the lack of prior research data as a reference, we cannot be completely certain that the CHG index had a predictive value for CMD that surpasses that of the TyG index. However, it can be confirmed that the CHG index was at least comparable to the TyG index. The importance of this is that the CHG index could improve the diagnostic potential of CMD when used alongside other metrics, much like the TyG index.Previous studies have confirmed that the TyG index, when combined with obesity indicators such as BMI, waist circumference (WC), and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), demonstrated superior predictive performance for various health outcomes in the general population compared to the TyG index alone. A global study with a 10-year follow-up involving a multi-ethnic population revealed that among the female cohort, the HR for the occurrence of CMD in the highest quartiles of TyG index, triglyceride-glucose-body mass index(TyG-BMI), triglyceride-glucose-waist circumference (TyG-WC) index, and triglyceride-glucose-waist to height ratio(TyG-WHtR) index were 1.78 (95% CI 1.41–2.25), 3.26 (95% CI 2.51–4.24), 3.13 (95% CI 2.41–4.06), and 3.19 (95% CI 2.47–4.12), respectively. The AUC of the ROC curve for the TyG combined index was significantly higher than that of the TyG index alone, demonstrating excellent performance in identifying individuals at risk for CMD37.Similar situations have also been observed with the triglyceride-glucose-body roundness index(TyG-BRI) index. Some studies have integrated TyG index and body roundness index (BRI) into a composite index that can capture metabolic status and obesity-related risks. Compared to using any single component alone, this dual biomarker shows a stronger association with CVD risk38.The study by Amin Mansoori et al. also compared the predictive values of Cholesterol-HDL-Glucose-body mass index(CHG-BMI), Cholesterol-HDL-Glucose-waist circumference (CHG-WC) index, and the individual CHG index for T2D, yielding contrasting results. The AUC for diagnosing T2D using CHG-BMI was 0.735 (95% CI 0.726, 0.744), while the AUC for CHG-WC was 0.790 (95% CI 0.781, 0.798), both of which were lower than that of the individual CHG index, which had an AUC of 0.864 (95% CI 0.857, 0.871)16.Amin Mansoori et al. did not provide a detailed explanation for this phenomenon in their work. We speculate that the core of the TyG index is to assess IR, with obesity (especially abdominal obesity) being the primary cause of IR. In contrast, the CHG index focuses more on disturbances in cholesterol metabolism and abnormal blood glucose levels. Although it is related to metabolic syndrome, its direct association with obesity is not as strong and direct as that of TyG with obesity. Therefore, CHG and obesity appear to be two related but relatively independent risk dimensions. Of course, this hypothesis should be further validated by subsequent research. The CHG index can be calculated using low-cost routine blood tests, providing a practical tool for the early identification of high-risk individuals for CMD in community and primary healthcare settings in China. Incorporating it into basic public health screening will assist community doctors or general practitioners in implementing targeted lifestyle interventions and enhancing follow-up, thereby supporting nationwide primary prevention efforts for CMD and alleviating its associated medical burden.

This study has several strengths: First, it is the first to validate the correlation and predictive value of the CHG index with CMD, and by comparing it with the TyG index, it confirms that the CHG index may become a new biomarker for assessing CMD. Secondly, this study employed a prospective research methodology and various statistical methods to develop a comprehensive assessment model, which included binary logistic regression, RCS, ROC, NRI, and IDI models. This multifaceted approach not only diversified the analysis and deepened the conclusions but also enhanced the reliability of the research findings through employing various types of sensitivity analysis, including E-values, Rosenbaum, and others. In addition, the data we used came from the CHARLS project, which was based on a nationwide random survey in China and provides up to 10 years of follow-up tracking. This data accurately represents the current situation of the elderly population in China. Of course, our research also has some limitations. Firstly, the information regarding CMD from CHARLS is based on self-reports from participants and lacks clear diagnostic criteria. For various reasons, there may be a certain degree of deviation from the actual prevalence of the disease. This misclassification is likely to be non-differential, meaning that participants’ understanding of their future disease status is unlikely to be influenced by their baseline biomarker levels. Additionally, due to the lack of detailed information on the participants’ medication history, physical activity and diet, we cannot rule out the potential impact of these factors on the research results. Secondly, due to the limitations of the CHARLS database survey population, we need to further investigate whether these results are applicable to other populations and younger demographics. Thirdly, the exclusion of certain biomarkers, such as renal function indicators and FPG levels, from the model is due to considerations of causality and over-adjustment. However, this still constitutes a methodological limitation that may affect the comprehensiveness of the model. Finally the discriminatory power of the TyG and CHG indices was relatively low, severely limiting their utility as standalone screening tools. Further development of combined indices may be necessary.

Conclusions

The CHG index has been linked to an increased risk of CMD in middle-aged and older adults in China, with a clear linear correlation observed. Although the CHG and TyG indices have different strengths and weaknesses when it comes to assessing the risk of newly developed CMD, the CHG index is still comparable to the TyG index in this respect.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the CHARLS offial website: https://charls.pku.edu.cn/.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BRI:

-

Body roundness index

- TyG:

-

Triglyceride-glucose index

- TyG-BMI:

-

Triglyceride-glucose-body mass index

- CHG:

-

Cholesterol-HDL-glucose index

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- WHtR:

-

Waist-to-height ratio

- TyG-WC:

-

Triglyceride-glucose-waist circumference index

- TyG-WHtR:

-

Triglyceride-glucose- waist-to-height ratio index

- FPG:

-

Fasting plasma glucose

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- CMD:

-

Cardiometabolic diseases

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- CHARLS:

-

China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic splines

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- NRI:

-

Net Reclassification Improvement

- IDI:

-

Integrated Discrimination Improvement

- AUC:

-

Area under curve

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- IR:

-

Insulin resistance

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- HOMA-IR:

-

Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- T2D:

-

Type 2 diabetes

- DCA:

-

Decision Curve Analysis

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factor

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

References

Li, Y. et al. Metformin use correlated with lower risk of cardiometabolic diseases and related mortality among US cancer survivors: evidence from a nationally representative cohort study. BMC Med. 22(1), 269. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-024-03484-y (2024).

Zhang, D. et al. Multimorbidity of cardiometabolic diseases: Prevalence and risk for mortality from one million Chinese adults in a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 9(3), e024476. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024476 (2019).

He, L. et al. Correlation of cardiometabolic index and sarcopenia with cardiometabolic multimorbidity in middle-aged and older adult: A prospective study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 15, 1387374. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1387374 (2024).

Mutalub, Y. B. et al. Gut microbiota modulation as a novel therapeutic strategy in cardiometabolic diseases. Foods. 11(17), 2575 (2022).

Garg, A. et al. Association of family history of cardiometabolic diseases (CMDs) and individual health behaviours: Analysis of CARRS study from South Asia. Indian Heart J. 74(4), 307–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2022.05.004 (2022).

Rees, K. et al. Mediterranean-style diet for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3(3), CD009825. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009825.pub3 (2019).

Diab, A., Dastmalchi, L. N., Gulati, M. & Michos, E. D. A. Heart-healthy diet for cardiovascular disease prevention: Where are we now?. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 19, 237–253. https://doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S379874 (2023).

Handelsman, Y. et al. Early intervention and intensive management of patients with diabetes, cardiorenal, and metabolic diseases. J. Diabetes Complic. 37(2), 108389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2022.108389 (2023).

Kosmas, C. E. et al. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J. Int. Med. Res. 51(3), 3000605231164548. https://doi.org/10.1177/03000605231164548 (2023).

Wei, Q. et al. Associations between the cardiometabolic index and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease acorss different glucose metabolism statuses: Insights from NHANES, 1999–2020. Lipids Health Dis. 24(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-025-02508-7 (2025).

Jin, Y. et al. Serum/plasma biomarkers and the progression of cardiometabolic multimorbidity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 11, 1280185. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1280185 (2023).

Yan, H. et al. Associations between cardiometabolic indices and the risk of diabetic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23(1), 142. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02228-9 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index in the prediction of new-onset arthritis in the general population aged over 45: The first longitudinal evidence from CHARLS. Lipids Health Dis. 23(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02070-8 (2024).

Liu, Q. et al. Association of the triglyceride-glucose index with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with cardiometabolic syndrome: A national cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02152-y (2024).

Gounden, V., Devaraj, S. & Jialal, I. The role of the triglyceride-glucose index as a biomarker of cardio-metabolic syndromes. Lipids Health Dis. 23(1), 416. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02412-6 (2024).

Mansoori, A. et al. A novel index for diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus: Cholesterol, high density lipoprotein, and glucose (CHG) index. J. Diabetes Investig. 16(2), 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.14343 (2025).

Mo, D., Zhang, P., Zhang, M., Dai, H. & Guan, J. Cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, and glucose index versus triglyceride-glucose index in predicting cardiovascular disease risk: A cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 24(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-025-02675-y (2025).

Barteková, M. et al. Natural and synthetic antioxidants targeting cardiac oxidative stress and redox signaling in cardiometabolic diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 169, 446–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.03.045 (2021).

Ma, N. et al. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health disorder in China: A nationwide study from CHARLS. J. Affect Disord. 355, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.03.110 (2024).

Xiong, C. C. et al. Investigating the impact of remnant cholesterol on new-onset stroke across diverse inflammation levels: Insights from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int. J. Cardiol. 405, 131946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2024.131946 (2024).

Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J. & Yang, G. Cohort profile: The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43(1), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys203 (2014).

Alizargar, J., Bai, C. H., Hsieh, N. C. & Wu, S. V. Use of the triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) in cardiovascular disease patients. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-019-0982-2 (2020).

Sun, Y., Ji, H., Sun, W., An, X. & Lian, F. Triglyceride glucose (TyG) index: A promising biomarker for diagnosis and treatment of different diseases. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 131, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2024.08.026 (2025).

Wang, Q., Pang, B., Wu, J., Li, C. & Niu, W. Reproductive factors and cardiometabolic disease among middle-aged and older women: A nationwide study from CHARLS. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1345186. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1345186 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Association between triglyceride-glucose index and the risk of cardiometabolic diseases in metabolically healthy obese individuals: A prospective cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 16, 1524786. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2025.1524786 (2025).

Yadegar, A. et al. Surrogate markers of insulin resistance and coronary artery disease in type 2 diabetes: U-shaped TyG association and insights from machine learning integration. Lipids Health Dis. 24(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-025-02526-5 (2025).

Chen, W. et al. Association between the insulin resistance marker TyG index and subsequent adverse long-term cardiovascular events in young and middle-aged US adults based on obesity status. Lipids Health Dis. 22(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-023-01834-y (2023).

Wada, M., Yano, S., Hamano, T., Nabika, T. & Kumakura, S. Effect of serum cholesterol on insulin secretory capacity: Shimane CoHRE study. PLoS ONE 11(2), e0149452. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149452 (2016).

Tangvarasittichai, S., Poonsub, P. & Tangvarasittichai, O. Association of serum lipoprotein ratios with insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Indian J. Med. Res. 131, 641–648 (2010).

Aguilar-Ballester, M. et al. Therapies for the treatment of cardiovascular disease associated with Type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(2), 660. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22020660 (2021).

Hyassat, D. et al. Dyslipidemia among patients with type 2 diabetes in Jordan: Prevalence, pattern, and associated factors. Front. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1002466 (2022).

Zhao, X. et al. Waist circumference glucose, a novel and effective predictor of type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 15, 1427785. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1427785 (2024).

Çatak, M., Konuk, ŞG. & Hepsen, S. The cholesterol-HDL-glucose (CHG) index and traditional adiposity markers in predicting diabetic retinopathy and nephropathy. J. Diabetes Investig. 16(8), 1487–1494. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.70086 (2025).

Liu, M. et al. Mechanisms of inflammatory microenvironment formation in cardiometabolic diseases: molecular and cellular perspectives. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1529903. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1529903 (2025).

Akhigbe, R. & Ajayi, A. The impact of reactive oxygen species in the development of cardiometabolic disorders: A review. Lipids Health Dis. 20(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-021-01435-7 (2021).

Zhang, P., Mo, D., Zeng, W. & Dai, H. Association between triglyceride-glucose related indices and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among the population with cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome stage 0–3: A cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 24(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-025-02642-7 (2025).

Yang, D., Li, X., Qu, C., Yi, J. & Gao, H. Comparison of triglyceride-glucose related indices in prediction of cardiometabolic disease incidence among US midlife women. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 19359. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03333-9 (2025).

Yang, Y., Cao, J. & Lyu, J. Association between changes in the triglyceride glucose-body roundness index and cardiovascular disease risk in middle-aged and elderly Chinese adults: A nationwide longitudinal study from 2011 to 2015. Front. Nutr. 12, 1560617. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2025.1599601 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the relevant researchers for generously sharing the CHARLS data included in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. T. contributed to the design of the research, the organization and analysis of data, supervised the project process, and drafted the initial manuscript. S. W. participated in the design of this study and supervised the project process. Y. Z. was involved in the formulation of the research methodology and drafted the initial manuscript. Y. L. contributed to the design of the statistical methods and conducted a rigorous review of the manuscript. All authors made significant, direct, and intellectual contributions to this study and consented to its publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement and informed consent statement

This study utilizes early research public data approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015). The research is a secondary analysis of publicly available CHARLS data. Since all participants signed a written informed consent form prior to joining the CHARLS study, the secondary analysis of the publicly anonymized dataset does not require institutional ethical review in accordance with the regulations of the Guangyuan Central Hospital Ethics Committee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, J., Wei, S., Li, Y. et al. Assessment of cholesterol-HDL-glucose index in anticipating risk of cardiometabolic diseases: a comparative study with triglyceride-glucose index. Sci Rep 15, 45356 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30024-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30024-2