Abstract

Whether postoperative radiotherapy (RT) is required for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) after breast-conserving surgery (BCS) remains controversial. In this study, we aimed to analyze the association between postoperative RT and survival outcomes in DCIS patients and develop nomograms to predict these outcomes. Using data on 50,580 DCIS patients obtained from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database, the Chi-squared tests revealed that DCIS patients with younger age, partial mastectomy, larger tumor size, negative estrogen receptor (ER) status, and higher nuclear grade, were more likely to receive postoperative RT. Additionally, Postoperative RT could improve the overall survival (OS), disease-specific survival (DSS), and disease-free survival (DFS) across most patient subgroups, although no significant association was observed in DSS among older patients or those with smaller tumor size. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses identified that age, tumor size, ER status, and nuclear grade were independent predictors for DSS and DFS. Based on these findings, we further constructed a nomogram, which demonstrated strong discriminative ability and good calibration as validated by C-index and calibration curve. A predictive online tool was created to visualize personalized DSS and DFS prediction for DCIS patients with different treatment regimens (https://nordaraail.github.io/breast-calculator/). Our study suggests that postoperative RT is associated with improved survival in most DCIS patients. The nomograms showed good performance in predicting the DSS and DFS of DCIS patients, and our online tool well visualized the DSS and DFS prediction to support clinical decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is a non-invasive form of breast cancer characterized by the proliferation of malignant epithelial cells confined within the ductal basement membrane, without invasion into the surrounding stroma1. It represents a heterogeneous condition, ranging from indolent, low-grade lesions with minimal risk of progression to high-grade lesions that may harbor or rapidly evolve into invasive breast cancer. Historically, DCIS is usually diagnosed by surgical removal of a suspicious breast mass, and comprises only 1–2% of all breast cancers2. However, with the widespread adoption of screening mammography, the incidence of DCIS has risen dramatically over the past 30 years. In 2023, approximately 55,720 new cases of DCIS were diagnosed in the United States, accounting for about 20% of all newly detected breast cancers3. Evidence from histopathological studies supports the notion that DCIS is a precursor lesion to invasive breast cancer (IBC)4, with a continuum of molecular and morphological changes observed during progression. The histological feature of DCIS is the proliferation of malignant epithelial cells surrounded by an intact basement membrane (BM) of the ducts5. The transition from DCIS to invasive disease involves the breakdown of the basement membrane and loss of surrounding myoepithelial cells, allowing tumor cells to infiltrate adjacent tissues6. Despite this understanding, there are currently no validated biomarkers that reliably predict which DCIS lesions will progress to invasive cancer. This lack of prognostic tools contributes to clinical challenges in risk stratification and optimal treatment selection, might resulting in overtreatment.

Standard treatment options for DCIS include mastectomy, breast-conserving surgery (BCS) alone, BCS with postoperative radiotherapy (RT), BCS with endocrine therapy, and BCS with both RT and endocrine therapy7. While mastectomy achieves excellent local control, the role of postoperative RT after BCS remains controversial. Several randomized clinical trials proved that the addition of RT after BCIS can significantly reduce the recurrence rates of DCIS patients8,9,10. Four large randomized trials also showed that RT halved the risk of ipsilateral events, while no significant effect was found on breast cancer mortality11. Nevertheless, the toxicities of RT cannot be ignored. Apart from commonly experienced side effects such as fatigue, skin reactions, and pain12, other severe toxicities like symptomatic radiation pneumonitis and radiation-related heart disease can also be caused13,14. Psychological burden and reduced quality of life may also accompany the increase frequency of side effects15. Thus, the recommendation of postoperative RT requires comprehensive consideration and should be weighed against potential radiation-associated toxic effects16. However, despite these side effects, the higher recurrence rate of BCS alone relative to BCS + RT, coupled with a 50% risk of invasive recurrence, has made people reluctant to advise against RT17. Therefore, accurate risk stratification method needs to be developed to screen out patients who are at high risk of recurrence and most likely to benefit from RT and those in whom it may be safely omitted.

In this study, we leveraged data from SEER database to investigate the influence of clinicopathological factors on RT selection and its association with survival outcomes in DCIS patients. To enhance clinical applicability, we also developed an online decision-support tool to facilitate personalized risk assessment and assist doctors and patients in making decisions regarding postoperative RT.

Methods

Data source

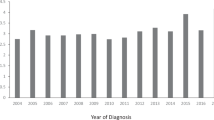

The clinical data and survival outcomes regarding 50,580 patients initially diagnosed with DCIS between 1998 and 2015 were obtained from the SEER database of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (http://seer.cancer.gov/). Baseline characteristics and clinicopathologic variables were collected, including age at diagnosis, race, surgical method, tumor size, estrogen receptor (ER) status, progesterone receptor (PR) status, nuclear grade, and survival data.

Patient selection

The inclusion criteria are listed as follows: female, 1998–2015 diagnosed as DCIS, with only one primary tumor or only one primary tumor as the first malignant cancer diagnosis, undergone partial mastectomy or subcutaneous mastectomy. Within the SEER database’s surgical codes, “subcutaneous mastectomy” is categorized at the same hierarchical level as “partial mastectomy”, which are classified as forms of BCS in this study. We excluded patients whose ER or PR expression status were unknown, with bilateral breast cancer lesions, with unknown race, tumor size and nuclear grade. The study outcomes included overall survival (OS), disease-specific survival (DSS), and disease-free survival (DFS) (median length of follow up = 56 months). OS was defined as the time from diagnosis to death from any cause. DSS was defined as the time from diagnosis to death, specifically from breast cancer. DFS was defined as the time from diagnosis to the first event, which was either the development of an ipsilateral second primary breast tumor (used as a surrogate endpoint for ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence, IBTR) or death from any cause. It is important to note that this definition of DFS does not specifically capture regional or distant recurrence events.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software and SPSS version 22. The differences in clinicopathological features between BCS and BCS + postoperative RT groups were analyzed via Pearson Chi-squared test. Logistic regression was used for screening out predictors of clinical RT selection. Univariate Cox regression was used to identify independent risk factors based on P values. All factors that were statistically significant in univariate analysis were entered into the multivariable Cox regression analysis, calculating by hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All tests were two-sided, and the value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Predictive nomograms were formulated based on the results of multivariable Cox regression analysis using R software. The concordance index (C-index) and calibration curve were utilized to evaluate the discrimination of nomograms.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 50,580 DCIS patients were included in this study. Among all patients, 34,832 (68.9%) patients received postoperative RT, while 15,748 (31.1%) patients did not. The patient selection process and reasons for exclusion are summarized in Fig. 1. The comparison of the population demographics, clinicopathological features, and treatment between two groups are presented in Table S1. Chi-squared test revealed statistically significant differences (all P < 0.001) in the distribution of all examined variables between the two treatment groups. Specifically, patients who received postoperative RT were more likely to be younger (56.8% of patients in the BCS + RT group were ≤ 60 years old, compared to 46.8% in the BCS alone group), undergo partial mastectomy (99.8% vs. 94.8%), have larger tumor size (46.8% had tumors > 10 mm vs. 40.8%), have ER-negative status (14.6% vs. 10.5%), have PR-negative status (24.4% vs. 18.7%), and have higher nuclear grade (Grade 3: 46.4% vs. 32.0%). The racial composition also differed significantly between the groups. Logistic regression analysis indicated that younger age, partial mastectomy, larger tumor size, negative ER status, and higher nuclear grade were significantly associated with a higher likelihood of receiving postoperative RT (Table S2).

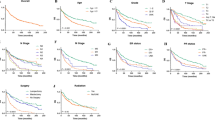

Identification of prognostic variables and subgroup analysis

Univariate Cox regression analysis was conducted with detailed results presented in Table S3. Postoperative RT was significantly associated with improved outcomes in OS (HR = 0.712, 95% CI: 0.666–0.761, P < 0.001), DSS (HR = 0.560, 95% CI: 0.466–0.672, P < 0.001) and DFS (HR = 0.509, 95% CI: 0.466–0.557, P < 0.001). Protective factors included positive ER status and PR status, which were associated with improved outcomes across all endpoints. Conversely, several risk factors were observed: older age was linked to worse OS and DSS; larger tumor size was associated with poorer OS and DFS; and higher nuclear grade was connected to worse DSS and DFS. Notably, some factors exhibited endpoint-specific associations: higher nuclear grade paradoxically showed a protective effect on OS, while older age unexpectedly demonstrated a protective association with DFS.

We further included all variables significant in univariate analysis into multivariate analysis, excluding PR due to its high collinearity with ER, and most associations remain statistically significant (Table S4). The multivariate analysis, which provides a more robust assessment by adjusting for potential confounders, confirmed that postoperative radiotherapy was independently associated with improved survival across all endpoints (OS: HR = 0.689, 95% CI: 0.644–0.737, P < 0.001; DSS: HR = 0.533, 95% CI: 0.443–0.641, P < 0.001; DFS: HR = 0.498, 95% CI: 0.455–0.545, P < 0.001). In this adjusted model, nuclear grade was no longer significantly associated with OS, indicating that its prognostic impact may be mediated by other clinical factors. However, nuclear grade remained significantly associated with DSS and DFS (DSS: HR = 1.347 for grade 3 vs. grade 1, P = 0.043; DFS: HR = 1.367 for grade 3 vs. grade 1, P < 0.001), suggesting a more pronounced independent role in recurrence risk.

To further validate the protective role of postoperative RT, we performed subgroup analysis stratified by other key clinical variables. Statistically, postoperative RT was associated with reduced risk of recurrence and mortality across most subgroups (Table 1). However, in the elderly patients (> 80 years) and small tumor size (≤ 2 mm) subgroups, no statistically significant association in DSS was observed (HR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.503–1.435, P = 0.543; HR = 1.088, 95% CI: 0.521–2.272, P = 0.822, respectively). Kaplan-Meier curves for DSS in these subgroups are shown in Figure S1. Additionally, lower hazard ratios associated with RT were observed in ER-negative patients for both OS and DSS, though this trend was not evident for DFS (Table 1).

Identification of independent prognostic variables

We performed multivariate Cox regression analyses separately for DCIS patients receiving BCS alone and those receiving BCS with postoperative RT to identify independent predictors within each group. For OS, older age and larger tumor size were independent risk factors in the BCS-only group. In the BCS + RT group, only older age remained significantly associated with worse OS (Table 2). For DSS, older age, larger tumor size, negative ER status, and higher nuclear grade were all risk factors in the BCS-only group. In the BCS + RT group, older age remained an independent risk factor, while larger tumor size (2–10 mm) appeared to be a protective effect (HR < 1). Nevertheless, as a whole, tumor size did not show statistical significance in BCS + RT group (P = 0.058, Table 3). In the DSS analysis (Table 3), no significant benefit was observed for patients aged 61–70 years (P = 0.322) or based on ER status (P = 0.469) within the BCS + RT group. For DFS, larger tumor size, negative ER status, and higher nuclear grade were associated with poorer outcomes in both groups, while older age served as a protective factor (Table 4). Additionally, the benefit for high nuclear grade (Grade 3) in the BCS + Postoperative RT group was of borderline statistical significance in the DFS analysis (P = 0.052, Table 4).

Construction of nomogram model and online tool for clinical use

Based on the multivariate Cox models for DSS and DFS, we developed distinct nomograms to estimate individualized survival probabilities for DCIS patients with and without postoperative RT (Fig. 2).

The nomogram for predicting patient prognosis treated with or without postoperative RT. (A) Nomogram for predicting 5-year and 10-year DSS of DCIS patients treated with BCS. (B) Nomogram for predicting 5-year and 10-year DSS of DCIS patients treated with BCS + postoperative RT. (C) Nomogram for predicting 5-year and 10-year DFS of DCIS patients treated with BCS. (D) Nomogram for predicting 5-year and 10-year DFS of DCIS patients treated with BCS + postoperative RT.

Figure 2 presents the nomograms developed to predict 5-year and 10-year DSS and DFS for DCIS patients treated with BCS alone (A, C) and those receiving BCS plus postoperative radiotherapy (B, D). Each nomogram incorporates the key independent prognostic factors identified through multivariate Cox regression analysis. To utilize the nomogram, clinicians first locate the patient’s value for each prognostic factor on the corresponding axis and draw a vertical line upward to the ‘Points’ axis to determine the score for that variable. The sum of these individual scores is then calculated and located on the ‘Total Points’ axis. Finally, by drawing a vertical line downward from this total score to the survival probability axes, clinicians can obtain the predicted 5-year and 10-year DSS or DFS probabilities for the individual patient. These visual prediction tools facilitate personalized risk assessment and enhance clinical decision-making regarding postoperative radiotherapy for DCIS patients. Due to the overwhelming influence of age on OS, a nomogram for OS was not constructed. C-index showed that these nomograms had good discriminative performance (Table S5). Calibration curves showed close agreement between predicted and observed survival probabilities at 5 and 10 years (Fig. 3), indicating good calibration abilities of the nomograms.

The calibration curve for evaluating the performance of nomograms in predicting DSS and DFS probabilities of DCIS patients treated with or without postoperative RT. (A) The calibration curve for evaluating the performance of nomogram in predicting 5-year and 10-year DSS probability of DCIS patients treated with BCS. (B) The calibration curve for evaluating the performance of nomogram in predicting 5-year and 10-year DSS probability of DCIS patients treated with BCS + postoperative RT. (C) The calibration curve for evaluating the performance of nomogram in predicting 5-year and 10-year DFS probability of DCIS patients treated with BCS. (D) The calibration curve for evaluating the performance of nomogram in predicting 5-year and 10-year DFS probability of DCIS patients treated with BCS + postoperative RT.

To enhance clinical utility, we developed a prediction online tool (available at: https://nordaraail.github.io/breast-calculator/). This tool allows clinicians and patients to input key variables, such as age, tumor size, ER status, and nuclear grade, and obtain personalized survival curves along with 5- and 10-year estimates for DSS and DFS under both treatment scenarios (with or without RT). The difference in predicted survival probabilities from these nomograms could be used to estimate the predicted survival difference associated with postoperative RT.

Discussion

The role of postoperative RT following BCS in DCIS patients remains a subject of clinical debate. While multiple randomized trials have demonstrated that whole breast RT (WBRT) significantly reduces the risk of ipsilateral recurrence18, no consistent OS benefit has been established19. Furthermore, mild and severe side effects of RT have also been reported, which may impair the quality of life20. Given that not all DCIS lesions progress to invasive disease, there is a growing concern about overtreatment. Therefore, we explored the impact of postoperative RT on OS, DSS, and DFS of DCIS patients, and constructed nomograms and a prediction online tool to enable individualized treatment decisions.

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, postoperative RT is not mandatory for all DCIS patients21. Different from invasive ductal carcinoma, radiation is believed to be beneficial for DCIS but may not always be necessary. In this study, of 50,580 DCIS patients were included, 34,832 received RT, reflecting its widespread use despite the absence of universal indication. We observed significant differences in clinicopathological characteristics between patients who did and did not receive RT. Logistic regression analysis revealed that younger age, larger tumor size, negative estrogen receptor (ER) status, higher nuclear grade, and partial mastectomy were significantly associated with RT use, which align with the commonly recognized risk factors for local recurrence22. Various clinical trials suggested that receiving RT after BCS reduced the ipsilateral recurrence. An observational study of 1,048 cases demonstrated that postoperative RT was associated with a reduced risk of ipsilateral recurrence in DCIS but no survival benefit23. A meta-analysis of four published randomized controlled trials showed that though addition of postoperative RT to lumpectomy did not reduce overall mortality, it decreased the ipsilateral breast and regional recurrence by almost half24. Consistent with previous studies, our analyses showed that postoperative RT was an independent protective factor in OS, DSS, and DFS. These findings suggest that RT can not only reduce the risk of local recurrence but is also associated with improved survival in the overall DCIS population. However, given the generally favorable prognosis of DCIS, the absolute survival association of RT may not be as obvious as reflected in the HR value.

Independent risk factors for worse OS and DSS included older age, larger tumor size, and negative ER status. For DFS, larger tumor size, ER negativity, and higher nuclear grade were independent risk factors. These calculated adverse predictors were consistent with the Van Nuys Prognostic Index (VNPI)25. Notably, older age appeared as a protective factor for DFS, and higher nuclear grade was not an independent risk factor for OS and DSS, suggesting its prognostic impact may be context-dependent. Our stratified analyses results further validated that postoperative RT was associated with reduced recurrence and mortality in most patient subgroups. However, no significant DSS association was observed in older patients or those with smaller tumor size, which aligns with previous study suggesting limited utility of RT in low-risk populations26. Considering the population recommended for radiotherapy in the previous literature (young age, premenopausal status, lymphovascular infiltration, high grade, large tumor size)27, our results support the notion that certain subgroups, particularly patients with older age (> 80 y) and small tumor size (≤ 2 mm), may be candidates for RT de-escalation. Additionally, lower hazard ratios associated with RT were observed in ER-negative and high nuclear grade subgroups for DSS. This suggests that patients with biologically aggressive features may derive greater survival association from adjuvant RT, reinforcing the importance of integrating tumor biology into decision-making.

An intriguing finding from our analysis warrants specific discussion: among patients treated with BCS alone, older age (71–80 and > 80 years) was associated with a lower hazard of DFS events compared to the youngest patients (≤ 60 years), as indicated by hazard ratios below 1.0 in Table 4. This observation appears paradoxical, given that age is generally not considered protective against tumor recurrence. Several interrelated factors may account for this result. First, the most plausible explanation involves the critical concept of competing risks. DFS is a composite endpoint that includes both ipsilateral recurrence (used as a surrogate for IBTR) and death from any cause. Older patients have a higher baseline risk of non-breast cancer-related mortality (e.g., cardiovascular disease, other age-related illnesses). These competing mortality events lead to earlier censoring of follow-up, thereby reducing the opportunity to observe recurrence events. Consequently, the conventional Cox proportional hazards model may underestimate the true recurrence risk in older adults by treating non-recurrence deaths as censored observations rather than informative events. Second, age-related disparities in clinical management, such as underuse of adjuvant systemic therapy and less intensive follow-up due to comorbidities or life expectancy considerations, may lead to under-detection of recurrences, particularly subclinical or asymptomatic cases, thereby artificially lowering observed event rates. Third, residual or unmeasured confounding factors, including differences in tumor biology, functional status, socioeconomic factors, or treatment adherence, may also influence the observed association. Our analysis, while adjusted for key clinical variables, cannot fully account for all such factors, especially those not captured in administrative or registry datasets. These issues underscore a limitation of using DFS in populations with vastly different mortality risks and suggests that for evaluating pure recurrence risk, especially in elderly populations, alternative statistical methods such as cumulative incidence functions accounting for competing risks would be more appropriate.

Furthermore, a critical nuance emerged from our findings: no significant benefit in certain endpoints, notably DSS, was observed in specific subsets, including elderly patients, those with small primary tumors, and individuals aged 61–70. Several underlying factors may explain this lack of observed benefit. Firstly, these subgroups likely harbor tumors with less aggressive biology, resulting in a lower baseline risk of locoregional recurrence. Secondly, competing risks of non-cancer mortality, particularly prevalent in older populations, can overshadow a potential DSS advantage. Lastly, age-related declines in functional reserve and tolerance may lead to increased susceptibility to radiotherapy-related toxicities, potentially offsetting the survival gains. Consequently, our data may support the concept of treatment de-escalation in these identified lower-risk populations.

Our findings confirm that postoperative RT is associated with a significant reduction in the relative risk of recurrence and breast cancer-specific mortality. However, in the context of the generally favorable prognosis of DCIS, where the absolute risks of these events are low, the decision to recommend RT must be individualized. This decision requires a careful discussion with patients about the trade-off between the modest absolute benefit and the potential for treatment-related side effects. Darby et al. found that the incidence of major coronary events increased linearly with the mean dose to heart, increasing by 7.4% per gray with no apparent threshold28. Another retrospective study of 52,556 DCIS patients by Withrow R et al. reported that postoperative RT increased risk of ipsilateral second non-breast cancers and radiation-related second cancers29. Besides, breast RT is reported to be associated with radiation-associated atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma30. These risks underscore the urgent need for personalized risk stratification to avoid unnecessary treatment. Currently, several prognostic tools have been developed to predict IBTR in DCIS patients. Rudloff et al. constructed a nomogram integrating 10 clinicopathologic variables to provide individualized estimate of IBTR risk in DCIS patients undergoing BCS31. The Oncotype DX DCIS score is one of the first molecular assays for IBTR risk assessment, comprising the expression of seven cancer-related genes (Ki67, STK15, Survivin, Cyclin B1, MYBL2, PR, GSTM1) along with five reference genes (ACTB, GAPDH, RPLP0, GUSB, TFRC). Another genomic assay, the DCISionRT Decision Score (PreludeDx), combines immunohistochemical assessment of six biomarkers (HER2, Ki-67, COX-2, SIAH2, FOXA1, p16) with four clinicopathological factors (age, tumor size, lesion palpability, and margin status) to generate a Decision Score ranging from 0 to 1032. Despite their utility, most of these models focus exclusively on ipsilateral recurrence and lack integration of survival outcomes such as DSS and OS33. Besides, the ER status, a well-established independent risk factor for local recurrence34, is absent in some models.

In order to accurately predict the survival and recurrence of patients after receiving different treatment methods, separate multivariate COX regression analyses were performed for OS, DFS and DSS of patients treated with BCS and BCS + postoperative RT. Due to the overwhelming influence of age among all factors in OS, no nomogram was constructed for OS of DCIS patients. The DSS and DFS nomograms for DCIS patients treated with BCS or BCS + postoperative RT demonstrated good discrimination and calibration, and their clinical utility was enhanced through the development of an open-access online prediction tool. This tool enables clinicians and patients to visualize individualized survival probabilities under both treatment scenarios, facilitating shared decision-making and personalized risk-benefit discussions.

There are many advantages in our study, such as large cohort, stratified analysis, nomograms based on group calculations, and online tool for clinical use. Nonetheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the SEER database lacks key clinical variables such as surgical margin status, endocrine therapy use, and timing of recurrence. The distance from the surgical margin to the tumor, in particular, is a critical determinant of local recurrence risk in patients undergoing BCS without postoperative RT35. Second, HER2 status was not consistently available in SEER until 2010 and was therefore excluded from our analysis, despite its potential prognostic and predictive value. Third, due to the absence of direct localized recurrence records in the SEER database, ipsilateral second primary breast cancer events were utilized as a surrogate indicator for local recurrence. However, the lack of precise recurrence dates limits the accuracy of DFS calculations, which might introduce potential bias, potentially contributing to discrepancies between the DFS derived in this study and clinical trial benchmarks. Furthermore, clinicians are more likely to recommend RT to younger, healthier patients with fewer comorbidities and a longer life expectancy, which are factors linked to better overall survival regardless of treatment and not fully captured in the SEER database. Therefore, the observed OS association in our study may not a direct effect of RT, but rather a reflection of the underlying favorable baseline characteristics of the patients selected for this treatment. Fifth, the median follow-up time of 56 months in our cohort is a critical limitation, particularly for assessing outcomes in DCIS. Given the non-invasive nature of DCIS and its propensity for late recurrence over many years, this follow-up period is insufficient to evaluate long-term survival outcomes, especially OS. This short follow-up likely contributes to the discrepant OS finding between our study and RCTs with 10–15 years of follow-up. Finally, our nomograms have not yet undergone external validation, therefore, their applicability to other populations remains to be confirmed. Future investigations would benefit from multi-institutional validation, including additional information with a large cohort and long-term follow-up data, to obtain a more effective and accurate prediction model.

Conclusion

Based on these SEER database analyses, patients with younger age, larger tumor size, negative ER status, higher nuclear grade, and those undergoing partial mastectomy were more likely to demonstrate improved survival outcomes with RT. Postoperative radiotherapy demonstrated significant benefits in OS, DSS, and DFS across the majority of subgroups; however, no significant benefit was observed for certain endpoints (e.g., DSS) in specific subgroups (such as elderly patients, those with small tumor size, and patients aged 61–70), suggesting potential for treatment de-escalation in these lower-risk cohorts. The developed nomograms demonstrated strong predictive performance for DSS and DFS in DCIS patients treated with or without postoperative RT. An accompanying online tool enables individualized risk estimation, facilitating shared decision-making and personalized treatment planning for DCIS patients considering adjuvant radiotherapy.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Jing, W. et al. Progression from ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive breast cancer: molecular features and clinical significance. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 9 (1). (2024).

Swallow, C. J. et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: progress and controversy. Curr. Probl. Surg. 33 (7), 553–600 (1996).

Siegel, R. L. et al. Cancer statistics, 2023. Cancer J. Clin. 73 (1), 17–48 (2023).

Wellings, S. R. & Jensen, H. M. On the origin and progression of ductal carcinoma in the human breast. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 50 (5), 1111–1118 (1973).

Lopez-Garcia, M. A. et al. Breast cancer precursors revisited: molecular features and progression pathways. Histopathology 57 (2), 171–192 (2010).

Gibson, S. V. et al. Everybody needs good neighbours: the progressive DCIS microenvironment. Trends Cancer. 9 (4), 326–338 (2023).

Barrio, A. V. & Van Zee, K. J. Controversies in the treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ. Annu. Rev. Med. 68, 197–211 (2017).

Cuzick, J. et al. Effect of Tamoxifen and radiotherapy in women with locally excised ductal carcinoma in situ: long-term results from the UK/ANZ DCIS trial. Lancet Oncol. 12 (1), 21–29 (2011).

Donker, M. et al. Breast-conserving treatment with or without radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ: 15-year recurrence rates and outcome after a recurrence, from the EORTC 10853 randomized phase III trial. J. Clin. Oncology: Official J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 31 (32), 4054–4059 (2013).

Warnberg, F. et al. Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery for ductal carcinoma in situ: 20 years follow-up in the randomized SweDCIS trial. J. Clin. Oncology: Official J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 32 (32), 3613–3618 (2014).

Karlsson, P. Postoperative radiotherapy after DCIS: useful for whom? Breast. 34 Suppl 1 (S43–S46. (2017).

Armin, H. et al. Impacts of radiation therapy on quality of life and pain relief in patients with bone metastases. World J. Orthop. 15 (9). (2024).

Mingyu, Y. et al. Multimodal data deep learning method for predicting symptomatic pneumonitis caused by lung cancer radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 15 (0). (2025).

Chin, V. et al. Overview of cardiac toxicity from radiation therapy. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 68 (8), 987–1000 (2024).

Wengstrom, Y. et al. Effects of a nursing intervention on subjective distress, side effects and quality of life of breast cancer patients receiving curative radiation therapy–a randomized study. Acta Oncol. 38 (6), 763–770 (1999).

Speers, C. & Pierce, L. J. Postoperative radiotherapy after breast-Conserving surgery for Early-Stage breast cancer: A review. JAMA Oncol. 2 (8), 1075–1082 (2016).

Wilson, G. M. et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ: molecular changes accompanying disease progression. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 27 (1), 101–131 (2022).

Ryoko, S. et al. Efficacy of radiation boost after breast-conserving surgery for breast cancer with focally positive, tumor-exposed margins. J. Radiat. Res. 61 (3). (2020).

Wapnir, I. L. et al. Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 103 (6), 478–488 (2011).

Ouying, Y. et al. FLASH radiotherapy: Mechanisms of biological effects and the therapeutic potential in cancer. Biomolecules 14 (7). (2024).

William, J. G. et al. Breast Cancer, version 3.2024, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 22 (5). (2024).

Sagara, Y. et al. Paradigm Shift toward Reducing Overtreatment of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ of Breast. Front. Oncol. 7, 192. (2017).

Corradini, S. et al. Role of postoperative radiotherapy in reducing ipsilateral recurrence in DCIS: an observational study of 1048 cases. Radiat. Oncol. 13 (1), 25 (2018).

Garg, P. K. et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy versus observation following lumpectomy in ductal carcinoma in-situ: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Breast J. 24 (3), 233–239 (2018).

Ryan, P. et al. Predictors of residual disease after breast conservation surgery for ductal carcinoma in situ: A retrospective study. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 20 (3). (2024).

Hwang, S. H. et al. Clinical outcomes of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast treated with partial mastectomy without adjuvant radiotherapy. Yonsei Med. J. 53 (3), 537–542 (2012).

Montero, A. et al. Postmastectomy radiation therapy in early breast cancer: Utility or futility? Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 147, 102887. (2020).

Darby, S. C. et al. Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 368 (11), 987–998 (2013).

Withrow, D. R. et al. Radiotherapy for ductal carcinoma in situ and risk of second non-breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 166 (1), 299–306 (2017).

Lucas, D. R. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 133 (11), 1804–1809 (2009).

Rudloff, U. et al. Nomogram for predicting the risk of local recurrence after breast-conserving surgery for ductal carcinoma in situ. J. Clin. Oncology: Official J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 28 (23), 3762–3769 (2010).

Ezra, H. et al. Can molecular biomarkers help reduce the overtreatment of DCIS? Curr. Oncol. 30 (6). (2023).

Xu, F. et al. A novel nomogram for predicting prognosis and tailoring local therapy decision for ductal carcinoma in situ after breast conserving surgery. J. Clin. Med. 11 (17). (2022).

Thorat, M. A. et al. Prognostic value of ER and PgR expression and the impact of Multi-clonal expression for recurrence in ductal carcinoma in situ: results from the UK/ANZ DCIS trial. Clin. Cancer Research: Official J. Am. Association Cancer Res. 27 (10), 2861–2867 (2021).

Van Zee, K. J. et al. Relationship between margin width and recurrence of ductal carcinoma in situ: analysis of 2996 women treated with Breast-conserving surgery for 30 years. Ann. Surg. 262 (4), 623–631 (2015).

Funding

Supported by the Special Foundation for Taishan Scholars (No. tsqn202507348) and Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2024MH242).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y. W., J. Z., and Y. L. Data curation: Y. W. and Y. L. Formal analysis: J. Z. and Y. W. Investigation: J. Z. and Y. W. Supervision: Y. L. Writing - original draft: Y. W. and J. Z. Writing - review & editing: Y. W. and Y. L. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Zhang, J., Wu, Y. et al. Postoperative radiotherapy for ductal carcinoma in situ: survival prediction and clinical decision support using a nomogram-based approach. Sci Rep 16, 433 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30025-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30025-1