Abstract

Oxidative stress is a key driver of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), often linked to reduced activity of catalase, a major antioxidant enzyme. In AD, catalase is not only less active but also found as part of harmful protein aggregates with amyloid-β in brain plaques. Finding safe molecules that can boost catalase activity and stop it from aggregating could, therefore, offer a new strategy to lower disease progression. In this study, we examined two natural organosulfur compounds from garlic—S-allyl cysteine (SAC) and Alliin—for their effects on catalase. We found that both compounds significantly increased catalase activity in a concentration-dependent manner by stabilizing its structure and enhancing its thermodynamic stability. Furthermore, Molecular docking and Simulation studies revealed that SAC and Alliin bind at an allosteric site, promoting structural compaction and enhancing stability. Importantly, these compounds also reduced the tendency of catalase to form amyloid-like aggregates, a feature directly relevant to AD pathology. Our findings provide new mechanistic insights into how SAC and Alliin act on catalase—both stabilizing the enzyme and resulting in an increase in its activity along with lowering its aggregation propensity. This suggests that SAC and Alliin may serve as promising, natural candidates for therapeutic intervention in Alzheimer’s disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurological disorder that causes memory loss, confusion and changes in a person’s behaviour1,2. It primarily affects older adults and is the most common form of dementia3,4. The pathophysiology of AD is characterized by the accumulation of extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregates and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated Tau protein in the brain leading to the mitochondrial dysfunction that results in an increased oxidative stress5,6,7,8. The increase in oxidative stress is considered to be an early event in AD pathology9,10 as it contributes to membrane damage, cytoskeleton alteration and cell death11. Therefore, it is believed that increased production of ROS may act as an important mediator of synaptic loss and eventual progression of disease pathology12. Cells have various safety mechanisms comprising of various enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems to maintain ROS concentrations below thresholds that would otherwise induce cellular toxicity. These antioxidant systems play a critical role in neutralizing free radicals and their antecedents, preventing their formation, and sequestering metal ions that catalyse oxidative reactions13,14. These antioxidant enzymes include, catalase, peroxiredoxin, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidases and thioredoxin and other non-enzymatic molecules are vitamin A, C,E, flavonoids, carotenoids, glutathione, polyamines, polyphenols, bilirubin etc15,16,17. Among these enzymatic antioxidants, catalase stands as one of the most crucial enzyme, due to its exceptionally high catalytic efficiency among other antioxidant enzymes13. Indeed, a single catalase enzyme is capable of decomposing millions of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) molecules into water and oxygen each second. The remarkable turnover rate of the enzyme highlight its critical function in maintaining cellular homeostasis by mitigating oxidative damage13,18 .Catalase deficiency has been reported to be associated with peroxisomal AD, primary reason is believed to be because of its peroxisomal localisation or its interaction with inhibitor brain metabolite myo-inositol19,20,21. Experimental studies demonstrate that Aβ directly binds to heme moiety of catalase, inhibiting its enzymatic activity and leading to intracellular accumulation of H₂O₂22. Alternatively, this binding results in certain conformational changes that is favourable for the enhanced formation of Aβ amyloids. Histopathological evidence further shows that catalase co-localizes with senile plaques in AD brains, suggesting its sequestration and functional inactivation in vivo23,24. Such interactions compromise neuronal redox balance, thereby amplifying oxidative stress and contributing to progressive neurodegeneration. Importantly, animal models reveal that enhancing catalase activity, particularly in mitochondria, not only mitigates oxidative stress but also reduces Aβ burden and improves cognitive outcomes25,26. Alternatively supplementation of active catalase to Aβ-challenged cells has been shown to protect cells from Aβ toxicity by decreasing levels of H₂O₂ and reducing protein and lipid oxidation27,28. These findings highlight catalase as both a mediator of oxidative injury and a potential therapeutic target in AD. Therefore, molecules that can activate catalase activity and inhibit its aggregation are promising candidates for the therapeutic intervention of AD.

For centuries, different herbs and plant-based remedies have been employed in the management of neurodegenerative diseases. In recent decades, many herbs and medicinal plants extract have shown their antioxidant effect through enhance antioxidant enzyme activity including catalase which are Lavandula stoechas (L.), Elatostema papillosum, Evolvulus alsinoides (Linn.), Psychotria calocarpa, Bauhinia coccinea, Rosmarinus officinalis, Bacopa floribunda, Allium Sativum, Syzygium antisepticum, Ginkgo Biloba etc29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Organosulfur compounds, abundant in dietary sources such as garlic and cruciferous vegetables, are recognized for their antioxidant38,39, anti-inflammatory40 and neuroprotective properties41,42,43. Several studies indicate that certain organosulfurs from aged garlic extract can modulate redox homeostasis by interacting with multiple antioxidant enzymes including catalase, superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, both in-vitro and in-vivo models44,45. Other studies have also reported that certain organosulfurs help to maintain mitochondrial integrity under stress conditions46. Furthermore, certain organosulfurs such as SAC, are also known to reduce amyloid burden and improve neuronal survival47,48. However, till date there is no report of the effect of organosulfurs on the functional activity of major antioxidant -enzyme catalase and its aggregation behaviour. Since, catalase emerges as a key enzymatic target for the redox homoeostasis and reducing Aβ burden, investigating the effect of organosulfurs on catalase has been an important intellectual curiosity. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanisms underlying this increasing antioxidant activity by garlic extract and their compound remain largely unexplored. In this study, we have made the systematic investigation of the effect of the most abundant organosulfur compound in SAC and Alliin on the structural and functional activity of catalase and their ability to modulate aggregation propensity of catalase. We discovered that these organosulfur compounds enhance catalase activity via structural stabilization with disfavouring unfolding of catalase even in stressful condition. This study reveals a promising therapeutic role for these organosulfur compounds in AD through their influence on the interaction between antioxidant enzymes and oxidative stress.

Results

Organosulfurs, SAC and alliin accelerate the activity of catalase

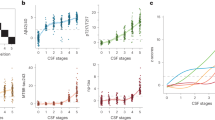

Both bovine (Bos taurus) and human (Homo sapiens) catalases belong to the heme-containing catalase family (EC 1.11.1.6) and share over 95% sequence identity. Structural studies reveal that their active-site geometry is nearly identical, as shown by crystal structures of bovine catalase (PDB: 1TGU) and human catalase (PDB: 7VD9). Importantly, the key catalytic residues—His, Tyr and Asn —are conserved in both species, ensuring that they operate through the same mechanism and maintain essentially the same structural features at the active site. To investigate the effect of organosulfurs on catalase activity, we, first of all, measured the time-dependent decomposition of H2O2 by bovine-catalase in the presence of different concentrations of SAC and Alliin (Fig. 1A and C). It is observed in Fig. 1 that H2O2 in the absence of catalase do not decompose significantly. However, upon addition of catalase there is gradual decrease in the absorbance yielding a hyperbolic curve indicative of catalase mediated hydrolysis of H2O2. In the presence of the SAC or Alliin, there is further acceleration of H2O2 decomposition. Concomitantly, there is an increase in the specific activity of the enzyme catalysis (Fig. 1B and D). We have again estimated the rate of enzyme-dependent hydrolysis by analysing the slope of the first few initial points of the hydrolysis reaction (Table S1). It is seen in the table that as expected, there is an increase in the rate of the enzyme-mediated catalysis in the presence of the organosulfurs in a concentration dependent manner. The results indicate that both organosulfur compounds SAC and Alliin accelerate functional activity of catalase (Figs. 2,3,4,5).

Catalase activity assay in absence and presence of organosulfur (SAC and Alliin). Time dependent catalase-mediated hydrolysis of H2O2 in presence of SAC (A) and Alliin (C). Panels (B and D) represents the specific activity vs. concentration of SAC and Alliin respectively. The standard mean error (± SEM) of phanel 1 A ranged from 0.006 to 0.002 while standard mean error (± SEM) of phanel 1 C ranged from 0.005 to 0.001.

Effect of organosulfurs on Vmax

The enzymatic activity of catalase in degrading hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was investigated by monitoring initial reaction velocities (Vo) across a range of substrate concentrations (Figs. 6,7,8). As expected, the reaction follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics, with Vo increasing in a hyperbolic manner as substrate concentration increased, eventually approaching a plateau indicative of enzyme saturation (Fig. 9). As shown in Table S2, in absence of organosulfur compounds, catalase exhibited a maximum reaction velocity (Vmax) of approximately 0.68 µmol/min and a Michaelis constant (Km) of around 2.2 mM. These values represent the baseline catalytic performance and substrate affinity of the enzyme under standard conditions. To assess the modulatory effect of organosulfur compounds on catalase activity, the enzyme was pre-incubated for 2 h with 500 µM of SAC or Alliin. Post-incubation, significant alterations in enzymatic kinetics were observed. Specifically, SAC treatment resulted in an increased Vmax of approximately 0.83 µmol/min, while Alliin led to a slightly higher increase, with Vmax reaching nearly 0.92 µmol/min. These enhancements in maximum velocity suggest that organosulfur treatment facilitates a higher catalytic turnover, possibly by stabilizing the active conformation of the enzyme or promoting more efficient product release. Concomitantly, the apparent substrate affinity of catalase improved, as evidenced by subtle decrease in Km. Upon SAC treatment, Km decreased to 2.0 mM, and with Alliin, a further reduction to 1.9 mM was observed. The lower Km values indicate that catalase bound hydrogen peroxide more readily in the presence of organosulfurs, suggesting either a structural change that enhances substrate recognition or a reduction in the energy barrier for enzyme-substrate complex formation. Taken together, the observed increase in Vmax and simultaneous slight decrease in Km imply a significant enhancement of catalase efficiency upon organosulfur treatment. These combined effects strongly suggest that organosulfurs act as positive modulators of catalase activity, potentially through allosteric mechanisms or subtle conformational changes that favour catalysis.

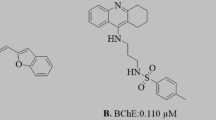

Both SAC and alliin bind to an allosteric site of catalase

Catalase is best known for its heme active site, where it breaks down hydrogen peroxide at an exceptionally fast rate. However, research has shown that its activity is not controlled by this site alone. The enzyme also carries other regions that can influence how it works49. For example, catalase binds NADPH at a site away from the heme, which helps protect the enzyme and keep it stable50,51. Since catalase is a tetramer, surface pockets and the interfaces between its subunits can also act as control points, where small molecules may bind and subtly change how efficiently the enzyme works52. In addition, certain cysteine residues make catalase sensitive to the local redox state, and compounds like nitric oxide and metal ions calcium, magnesium and manganese are known allosteric regulators of catalase, with these features we investigated if SAC and Alliin also regulate catalase activity by binding to an allosteric site53,54. To study for this possibility, First of all, using sitemap, we identified five potential binding sites with site scores of 0.917, 0.907, 0.901, 0.876, and 0.556 for sites 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively (See Table S3). We then performed systematic docking of SAC and Alliin at each of the binding pocket using Glide tool. The respective docking scores and glide energy are shown in Table 1. As depicted from the docking scores and glide energy values for all the site the highest binding energy with docking score were observed to be site 2 common to both SAC and Alliin. Figure 2 also shows the 3D and 2D poses of catalase upon binding at site 2. It is seen in Fig. 2A and C that both SAC and Alliin binds at a common site (site 2) away from the active site indicating the possibility of behaving as allosteric ligands of catalase. Figure 2B and D also suggest that SAC binds to the site 2 by forming 3 hydrogen bonds with different residues namely, Asn213, Tyr215, and Asn149. In case of Alliin, the hydroxyl (–OH) and carbonyl (C = O) functional groups of Alliin formed strong hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues, including Arg203, Asn149, and Tyr215. These polar interactions contribute significantly to the specificity and stabilization of the ligand within the binding cleft. These results indicate that both organosulfur compounds strongly bind to the same site of the catalase with different binding affinities. Interestingly, many residues of this site including Tyr 215, Asn 213 etc. overlap with the NADPH binding pocket indicating that organosulfurs act as protective agent for catalase against oxidative damage by allosterically stabilising the enzyme and maintaining its activity, in a manner a bit similar to NADPH.

MD stimulation studies

An MD simulation for 100ns was performed for both catalase-organosulfur complexes (Catalase-SAC and Catalase-Alliin), as shown in Figs. 3 and 4 respectively. The stability of the system was assessed using root mean square deviation (RMSD) and RMSF values. It is seen in Figs. 3A and 4A that the system achieved the equilibrium conformation after 5ns. The reference protein (without any bound ligand) showed a very stable RMSD profile (average 0.92 Å). The protein-bound SAC and Alliin also showed stable RMSD fluctuations over run-length of average 0.87 Å and 0.88 Å respectively. These RMSD profile (Figs. 3A and 4A) indicates that catalase in its unbound state and catalase in complex with both SAC and Alliin remain stable during the simulation. However, in presence of both SAC and Alliin, RMSD fluctuations slightly reduces, suggesting that both organosulfur stabilizes the protein structure. These mild fluctuations indicate that both compound might restrict local flexibility without disrupting the overall fold. The root mean square fluctuation RMSF profile (Figs. 3B and 4B) was used to analyse the mean fluctuation of each residue, providing insights into the flexibility of catalase both in unbound and bound with organosulfur compound. In the presence of both organosulfur, catalase remains structurally stable. Both compound slightly reduces fluctuations in some regions, suggesting stabilization of certain residues. However, specific regions exhibit increased flexibility possibly due to ligand-induced conformational changes. There is highest fluctuation particularly in the loop or surface-exposed regions, which might increase substrate accessibility or stability of catalase with some peaks correspond to secondary structure elements (lower RMSF, such as α-helices and β-sheets). Furthermore, SASA (Figs. 3C and 4C) was analyse for the MD output structures and plotted as a function of time. All the systems showed stable simulation, indicating small increase in SASA with SAC and Alliin suggests that both compound slightly increase solvent exposure, possibly by inducing minor conformational changes and localized expansion at their binding site of protein. However, the overall stability of the protein is not compromised since SASA fluctuation remain within a normal range. This minor structural expansion could influence enzyme activity or stability of protein which might be the result of increase enzyme activity in presence of both organosulfur compound. The radius of gyration values (Rg) (Figs. 3D and 4D) calculated for the MD output structures further shows a stable radius of gyration profile, indicating subtle conformational changes with no significant structural expansion/compression of the system in the course of simulation. From both analysis, we can conclude that SAC and Alliin binding brings slight increase solvent exposure, possibly by loosening local interactions or inducing small structural rearrangement without effecting global structure of catalase. We then monitored the number of stable hydrogen bonds (Figs. 3E and 4E) between protein and ligands using the default hydrogen bond angle (120°) and distance (3.5 Å) throughout the simulations. SAC maintains a dynamic but stable interaction with catalase, forming 2–3 H bonds consistently throughout the simulation. In case of Alliin, the number of H-bonds fluctuates significantly, reaching up to 6 H-bonds at some points suggesting initial strong interaction between Alliin and catalase, possibly as the ligand settles into a stable binding pose. The number of H-bonds decrease after 10ns fluctuating mostly between 1 and 3 bonds, indicate a partial rearrangement of SAC within the binding site or weaker interactions. Other non-covalent interactions (i.e. hydrophobic, Van der waals) also contribute to stabilizing SAC, Alliin binding along with H-bond. From both MDS data and 2D and 3D docking structure suggested that both organosulfur compound maintained several H-bonds while maintaining intense van der Waals and hydrophobic contacts with other amino acid residue of the binding site of the protein.

Organosulfurs bring about conformational alterations in catalase

Binding of the organosulfur compounds to catalase might result in the structural alteration in the enzyme appropriate for proper catalysis. Using multiple spectroscopic techniques, we analysed the conformational changes in the enzyme. Far-UV CD measurements revealed that there is increase in the secondary content of the protein in the presence of both SAC and Alliin (Fig. 5A and E ). Table S4 also shows the calculated percent secondary structural components of catalase in the absence and presence of the organosulfurs. It is seen in Table S4 that there is little increase in α-helix and eventual decrease in the anti-parallel and parallel beta-sheets indicating reshuffling of secondary structural components. Our results on near-UV CD depicts that there is gross increase in the tertiary structure of the protein (Fig. 5B and F). Figure 5C and G also shows that there is observed hyperchromicity at around 295 nm upon addition of the organosulfurs suggesting that the tryptophan chromophores have been accommodated in a more non-polar micro-environment upon addition of the organosulfurs. We further analysed for (8-Anilinonaphthalene-1-sulphonic acid) ANS binding propensity to look for changes in the exposed hydrophobic clusters present in the protein surface. It is observed in Fig. 5D and H, that catalase in its native conformation binds to ANS and this binding is further enhanced upon addition of the organosulfurs. The results indicates that some of the hydrophobic clusters that were present in the surface of the protein have been packed in the interior of the protein making them inaccessible to the solvent.

Conformational status of catalase in presence of SAC and Alliin. Far UV CD (A, E), near-UV CD (B, F), tryptophan fluorescence (C, G), ANS binding assay (D, H). Major spectra properties for representing Far UV CD, Near-UV CD, intrinsic and extrinsic florescence. Upper and Lower panel represent spectra for SAC and Alliin respectively. Spectra and results shown are representative of at least three independent measurements.

SAC and alliin increases Tm of catalase

Increase in the structural stability of the enzyme could be associated with the increased thermodynamic stability of the enzyme. To investigate for this, we have measured heat-induced denaturation profile of the catalase in the absence and presence of different concentrations of SAC and Alliin as indicated in Fig. 6A and B. These denaturation profiles are evaluated for the thermodynamic parameters (Tm and ΔHm) using Eq. 1 and are given in Table 2. It is seen in the table, in case of SAC, there is 2–3 °C increase in the Tm of catalase with a parallel increase in the ΔHm values. Similarly, in the presence of Alliin, Tm value of catalase have been raised to 2–5 °C with concomitant increase if the ΔHm values. Results indicate that SAC and Alliin increases thermal stability of catalase.

SAC and alliin suppress catalase aggregation

To investigate if organosulfur compounds affect aggregation propensity of catalase, we have incubated the native catalase at 55 °C and measured its time-dependent oligomerization process by monitoring the change in light scattering intensity. It is observed in the Fig. 7A and C that the oligomerisation process follows a sigmoidal curve indicative of conventional protein aggregation process. It is also seen in this figure that there is a concentration-dependent decrease in light scattering intensity for both the organosulfurs as indicated by the nature of the hyperbolic curve relative to the control. We have also analyzed the curves for aggregation kinetic parameters lag time, Kapp and If (Table 3). It is seen in the table that there is increase lag phase (nucleation phase) and concomitant decrease in the rate of oligomerisation (kapp) .This effect on lag phase and Kapp results in large decrease in the magnitude of final aggregates formation. Figure 7B and D also show that there is complete co-relation of the disappearance of oligomers in increase organosulfur concentration. We have also examined the morphology of oligomers formed upon addition of organosulfurs using Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). Figures 8A and B show that catalase oligomers are amyloidogenic in nature and treatment with organosulfur compounds results in the large reduction in the magnitude of the aggregates formed. We have also confirmed the observations on TEM using Thioflavin T (ThT) binding assay. ThT is a dye that can specifically bind to the cross beta sheets formed by the amyloid oligomers and therefore, is a signature of amyloidogenic aggregates. It is seen in the Figs. 8C and D that there is a concentration-dependent decrease in ThT fluorescence intensity upon addition of SAC and Alliin. The findings indicate that both SAC and Alliin exhibit significant anti-aggregating potential.

Aggregation profiles of catalase in presence of organosulfurs. Time-dependent aggregation kinetics monitored by observing changes in the light scattering intensity at 360 nm in absence and presence of SAC (A) and Alliin (C). Plot of Precent disaggregation of catalase vs. concentration of SAC (B) and Alliin (D) respectively.

Discussion

Oxidative stress is a well-recognized contributor to Alzheimer’s disease, and reduced catalase activity in patients has been attributed to inhibition by myo-inositol or Aβ binding21,22. In this context, our findings in Fig. 1 indicate that SAC and Alliin enhance catalase activity in a concentration-dependent manner are significant, as they suggest that organosulfurs may counteract this loss of enzymatic defense and help restore redox balance. Mechanistically, docking (Fig. 2) and MD simulation studies (Figs. 3 and 4) revealed that SAC and Alliin bind to an allosteric site on catalase, providing a structural basis for the observed increase in activity. Importantly, spectroscopic analyses (Fig. 5) demonstrated that this binding induces conformational stabilization and structural compaction of catalase, reducing solvent-exposed hydrophobic clusters. Such stabilization is known to improve protein thermodynamic stability55, and in our study correlated strongly with enhanced catalytic efficiency, indicating that organosulfurs increase the functional pool of catalase by shifting the equilibrium toward its active, native state. Beyond activity enhancement, our data in Fig. 7 also show that SAC and Alliin decrease the aggregation propensity of catalase.

Since catalase oligomers have been implicated in AD plaques and may exacerbate Aβ-driven toxicity22,24, this anti-aggregation effect is particularly relevant. Together, these findings suggest a dual mechanism: organosulfurs not only boost catalase activity but also stabilize its structure against aggregation, thereby preserving its antioxidant function under pathological conditions. While previous studies have demonstrated the catalase-activating potential of organosulfurs, Our work provides novel mechanistic insights by identifying the allosteric binding site, structural compaction, and stabilization of catalase as the basis of enhanced activity. These structural details offer a deeper understanding of how organosulfurs modulate catalase function, beyond what has been previously reported. Protein structural compaction is generally associated with enhanced thermodynamic stability, which increases the availability of the functionally active fraction of enzymes55,56. In line with this, we observed (Fig. 6) that SAC and Alliin stabilize catalase by increasing its thermal transition temperature (Tm) and enthalpy of unfolding (ΔHm), leading to an ∼18–20% rise in free energy of unfolding (ΔGD°) compared to the native enzyme (Table 2). This stabilization strongly correlated with enhanced catalytic efficiency, as reflected by a near-perfect relationship between ΔGD° and specific activity (R² = 0.98) (Figure S1) and by the increase in Vmax coupled with a reduction in Km in the presence of organosulfurs (Fig. 9 and Table S2). These results indicate that SAC and Alliin enhance catalase activity by promoting its thermodynamic stability and shifting the equilibrium toward the folded, active state.

Beyond activity, catalase aggregation itself has been suggested to contribute to AD pathology, as catalase can form oligomers and interact with Aβ, potentially exacerbating oxidative stress and neuronal dysfunction22,23,24. Protein stabilizers are known to suppress such aggregation by preventing the formation of aggregation-prone intermediates. Consistent with this, we found that SAC and Alliin reduced catalase aggregation in a concentration-dependent manner, extending the lag phase of nucleation and decreasing the overall oligomer load (Fig. 7 and Table 3 ). Light scattering, TEM, and ThT fluorescence assays (Fig. 8) further confirmed that these organosulfurs lowered the formation of amyloid-like catalase aggregates. Since catalase oligomers have been identified within AD plaques, this anti-aggregation effect may have direct pathological relevance. Furthermore, as catalase can facilitate Aβ oligomerization23, inhibition of its aggregation by SAC or Alliin may also mitigate Aβ-associated plaque toxicity. Supporting this, earlier studies shows that catalase supplementation reduces H2O2 accumulation and protects neurons against Aβ toxicity28. Thus, our findings suggest a dual role of organosulfurs in AD: by stabilizing catalase structurally and functionally, they enhance its antioxidant activity while simultaneously reducing its aggregation and its potential to promote Aβ oligomerization.

Garlic’s organosulfur compounds SAC and Alliin—have drawn attention because they act on several levels in the human body. On the most basic level, they are powerful antioxidants: SAC is water-soluble, stable, and directly scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS), while also boosting the activity of the body’s own defense enzymes. Alliin, the stable compound in fresh garlic, is converted into Allicin and further metabolites when garlic is crushed; these downstream molecules also mop up free radicals and limit lipid peroxidation57. But their impact goes beyond antioxidant work. In the brain, SAC can cross the blood–brain barrier, where it calms overactive immune cells (microglia), stabilizes mitochondria (the cell’s energy hubs), and reduces aggregation of amyloid-β—an important driver of Alzheimer’s disease. Animal studies consistently show SAC improves memory and learning, making it a promising neuroprotective candidate58. In the cardiovascular system, clinical trials of aged-garlic extract (rich in SAC) have shown lower blood pressure, better arterial elasticity, and slower growth of vulnerable plaques, likely by modulating inflammatory pathways such as TLR4–NF-κB in addition to ROS reduction59 In muscles, preclinical studies reveal SAC limits denervation-induced wasting by suppressing oxidative stress and proteolysis60; while encouraging, it is not yet an approved therapy for muscular dystrophy.

Thus, beyond above mentioned well-known effects of organosulfurs, our findings highlight a novel mechanism whereby SAC and Alliin stabilize catalase structurally, increase its thermodynamic stability, and critically, inhibit its aggregation propensity. This dual action—activation and anti-aggregation—represents a novel therapeutic avenue that links organosulfurs to both catalytic protection and aggregation control in AD.

Conclusion

Our study shows that two natural compounds found in garlic, SAC and Alliin, not only boost the activity of catalase but also make it more stable and less prone to harmful aggregation. Since catalase dysfunction and aggregation are linked to oxidative stress and plaque formation in Alzheimer’s disease, restoring its activity could help slow down disease progression. Mechanistically, SAC and Alliin binds to an allosteric site of the catalase and also increase its thermodynamic stability thereby producing more active fractions in their presence.

What makes our findings important is the dual action of SAC and Alliin—they enhance the beneficial function of catalase while at the same time preventing its aggregation, which is often seen in Alzheimer’s pathology. This dual effect provides a new rationale for using SAC and Alliin as natural, safe, and accessible therapeutic agents. While current treatments for Alzheimer’s mostly focus on symptoms, our results suggest that dietary or drug-based interventions with compounds like SAC and Alliin may help address one of the root causes of the disease—oxidative stress and toxic protein build-up.

In the future, further animal and clinical studies will be needed to confirm these benefits and explore how organosulfurs can be developed as supportive therapies, possibly in combination with existing Alzheimer’s drugs.

Material and method

Materials

Commercially lyophilized powdered of catalase (from bovine erythrocytes), ThT and ANS were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. Potassium chloride, di-potassium hydrogen phosphate and potassium di-hydrogen phosphate were purchased from Merck, India. H2O2, were also procured from Sigma. Phytochemical S-allyl-cysteine and Alliin were purchased from Cayman company and Sigma Aldrich respectively. These and other chemicals, which were of analytical grade and were used without further purification.

Preparation of protein stock solutions and determination of concentrations

The stock solutions of catalase were prepared in 0.05 M degassed potassium phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 and were filtered using 0.2 μm Millipore syringe filter. Protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically using molar extinction coefficient (ε405) value of 3.24 × 105 M− 1cm− 1. H2O2 solution, prepared in 0.05 M phosphate buffer of pH 7.0, was always fresh and its concentration was determined using a molar extinction coefficient (ε240) value of 40 M− 1cm− 1. The stock solution of SAC and Alliin were prepared in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. pH values of all samples were found not to be significantly changed upon addition of the additives. Concentration of ANS was determined experimentally using ε, the molar absorption coefficient value of 5,000 M− 1 cm− 1 at 350 nm and was filtered before use to remove insoluble particles.

Methodology

Measurement of catalase activity

Activity measurement of catalase was carried out by spectrophotometric method, using Agilent Cary UV/vis spectrophotometer, wherein a decrease in the absorbance of the substrate, H2O2 was monitored in the presence of catalase61,62. For monitoring the effect of organosulfur compounds on catalase activity, catalase at a concentration of 10nM was preincubated in different concentration of SAC and Alliin. A reaction was initiated upon addition of H2O2 to the reaction mixture and the catalase mediated degradation of substrate (H2O2) was measured by monitoring the changes in the absorbance of H2O2 at 240 nm for 15 min. The progress curve was analyzed for their rate substrate decomposition by catalase in absence and presence of additives.

Calculation of specific activity

Specific activity of the enzyme was calculated by dividing the enzyme activity divided by the total protein concentration (mg of protein in unit volume). For this the final OD at the end of the 15 min was converted into its molar concentration by using molar ellipticity of H2O2 ( 43.6 dmol− 1cm− 1). The measured enzyme activity (in unit time) is divided by the total enzyme concentration.

Measurement of Vmax and Km

To estimate Vmax and Km of the enzyme-catalysed reaction, catalase was titrated with different substrate (H2O2) concentrations (1 mM, 2 mM, 4 mM, 6 mM, 8 mM, 12 mM and 15 mM) and time-dependent progress curves were collected. Each progress curve was analysed for reaction rate constant (ko) by analysing slope of the linear dependence of first few points. We then calculated initial velocity, Vo with the help of the relation:

Vo = ko [ES] (where ES is equivalent to the total enzyme concentration).

A plot of Vo versus substrate concentration was further constructed and their relation was analysed using Michaelis-Menten equation to yield Vmax and Km as shown below.

where Vo is the initial velocity of the enzyme, S is substrate concentration, and Vmax is the maximum velocity of the enzyme, Km is Michaelis constant (substrate concentration at which V = Vmax/2). For estimating the effect of organosulfurs, catalase was incubated in organosulfur solutions for 2 h before the beginning of the hydrolysis reaction.

Docking studies

The crystal structure of human catalase with PDB ID 7VD9 was selected for the docking studies. The crystal structure with heme moiety in the binding site was optimised using the protein preparation wizard in Maestro Glide. The structure of ligands SAC, Alliin (Pubchem CID 9793905;87310) were optimized using the ligprep module of Maestro. First of all, we detect sitemap to find out docking possible site of the protein. Then, docking studies were performed using the software Maestro Glide with five different grid box covering the different sites of the whole protein structure and result were analysed based on Docking score and Glide energy.

MD simulation

Molecular dynamics MD simulations were carried out using the GROMACS 2022.4 software63. First, Water molecules and docked ligand were removed from the x-crystallographic structure. The topology of the catalase was generated by using the Chimera27 force field. The input files of both protein and ligand were merged manually. Then the protein-ligand complex was placed in a triclinic box which is 1 nm apart from the periodic boundaries. The TIP3P (transferable intermolecular potential with 3 points) model was used and was solvated by 24,595 solvents. Further, the system was neutralized by 22 Na+ ions64,65. The prepared model system was minimized at increasing temperature 1–300 K using the steepest descent method and lasted < 1000 steps. Next, the system was equilibrated using NPT and NVT method for 1ns63. The LINCS algorithm was used to adjust the constrain of hydrogen bonds66. Particle-mesh Ewald (PME) summation was used to calculate electrostatic interactions and the coulomb interaction was set to be 1.2nm67. Then, the stability of catalase and catalase-organosulfur complexes was assessed using various parameters such as RMSD, RMSF, Rg, SASA, hydrogen bond. The results of complexes were compared with the control (without Ligand or apo form) of catalase. The MDS was performed for the 100 ns to assess the interaction and stability of the molecules.

Conformational studies

Fluorescence studies

For tryptophan fluorescence, we used 0.5 mg/ml concentration of catalase protein by dissolving in 0.05 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Then protein samples were incubated overnight in presence of 200 µM and 500 µM of all SAC and Alliin. Samples were excited at 295 nm and tryptophan fluorescence were recorded in a 5 mm quartz cell between in the range of 300 nm to 500 nm at 25 °C using Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer equipped with a single cell Peltier. The excitation and emission slit width used for fluorescence assay is of 10 nm. For ANS binding assay, catalase (0.5 mg/ml) in 0.05 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 was incubated overnight in presence of two different concentration of SAC and Alliin and (200 µM and 500 µM) at room temperature. Working concentration of ANS was kept 16-fold than that of protein concentration. ANS was added 30 min prior to the measurement of the samples. Samples were excited at 360 nm and ANS binding spectra were recorded in a 5 mm quartz cell in the wavelength range 400 nm and 600 nm at 25 °C with an excitation and emission slit width of 10 nm at a scanning speed of 100 nm/min in a Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer.

Circular dichroism (CD) measurement

Catalase at the working concentration of 0.75 mg/ml were incubated overnight in presence of 200 µM and 500 µM of organosulfurs SAC and Alliin. For secondary structure estimation, far-UV spectra were recorded in the wavelength range 190 to 240 nm in the cuvette cells with pathlength 0.1 cm. For protein tertiary structure measurement, near-UV spectra was recorded in the wavelength range from 250 to 320 nm with 0.5 cm path length cuvettes. CD spectral measurements were made in a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter equipped with a Peltier-type temperature controller with at least three accumulations and all necessary blanks were subtracted from each of the sample reading.

Aggregation studies

Light scattering measurements

The light scattering method used depend on the fact that the scattering intensity is highly dependent on the particle/aggregate size. Therefore, the formation of aggregates/fibrils can be detected by monitoring the increased in the scattering intensity with respect to the time. Catalase samples (0.75 mg/ml) were incubated overnight in presence of 100 µM, 200 µM, 500 µM and 1000 µM concentrations of organosulfurs, SAC and Alliin at room temperature. The aggregation profiles were monitored by measuring the changes in the light scattering intensity at 360 nm at 55 °C for 10 min using Cary Eclipse Fluorescence spectrophotometer equipped with a single cell Peltier controller. Aggregation kinetic parameter (lag time, kapp and If) were determined by analysing the light scattering intensity versus time curves using the following equation,

Where I is the light scattering intensity at time t and t0 is the time at 50% maximal light scattering, I0 and If represent the initial base line and final plateau line, respectively and b is a constant. Thus, the apparent rate constant, kapp for the formation of aggregates is given by 1/b and the lag time is given by t0-2b68,69. Each curve was independently analyzed for the respective kinetic parameters and the mean was calculated.

ThT binding assay

For ThT fluorescence assay, catalase (0.75 mg/ml) samples were incubated overnight at room temperature in absence and presence of different concentrations (100–1000 µM) organosulfur, SAC and Alliin. Thereafter, treated samples were subjected to heat treatment for 7 min at 55 °C for to induce formation of high order oligomers (amyloid-like fibril formation). Upon cooling down the sample, 30 µM ThT dye was added 30 min prior to the measurement of samples in a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer. The measurements were carried out in the wavelength range of 470–600 nm at 25 °C with an excitation and emission slit width of 10 nm at a scanning speed of 100 nm/min. For the measurement, samples were excited at 450 nm and spectra was recorded in a 5 mm quartz cell.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

To confirm the presence of protein aggregates, catalase samples were incubated at 55 °C in the presence and absence of organosulfurs, SAC and Alliin. A droplet of the sample (12ul) was placed and kept for drying on a copper grid for 5 min (at RT). Prior to drying, negative staining was done by adding 1% uranyl acetate solution onto the copper grid. Transmission electron micrographs of the catalase samples were recorded on FEI Tecnai G2-200 kV HRTA transmission electron microscopy (Netherland) (equipped with digital imaging) facility available at AIIMS, New Delhi and digital images were visualized at different magnifications.

Thermal denaturation studies

Catalase protein sample (0.75 mg/ml) in 0.05 M potassium phosphate buffer, 7.4 were incubated overnight in presence of SAC and Alliin at room temperature. Then, thermal denaturation studies were carried out in a Jasco V-660 UV/Visible spectrophotometer equipped with a Peltier-type temperature controller at a heating rate of 1 °C per minute. This scan rate was found to provide adequate time for equilibration. Each sample was heated from 20 °C to 80 °C. The change in absorbance with increasing temperature was followed at 292 nm using appropriate blanks. Measurements were repeated at least three times. Each heat-induced transition curve was analysed for Tm and ΔHm using a non-linear least-squares method according to the relation.

Where y(T) is the optical property at temperature T (Kelvin), yN(T) and yD (T) are the optical properties of the native and denatured protein molecules at T, K respectively and R is the gas constant. In the analysis of the transition curve, it was assumed that a parabolic function describes aN+bNT+cNT2 and yD(T) = aD+bDT+cDT2, where aN, bN, cN, aD, bD and cD are temperature independent coefficients)

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in a minimum of three independent replicates. The mean values from these replicates were calculated, and standard errors were analysed. These standard errors are either represented as error bars in the figures or reported as ± standard deviation. Statistical significance (p-values) was determined using one-way ANOVA in GraphPad Prism software.

Data availability

All data produced or examined in this study are available within this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Selkoe, D. J. Alzheimer’s disease: Genes, Proteins, and therapy. Physiol. Rev. 81, 741–766 (2001).

Jönsson, L. et al. Determinants of costs of care for patients with alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Geriat Psychiatry. 21, 449–459 (2006).

Fratiglioni, L. et al. Incidence of dementia and major subtypes in europe: A collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurologic diseases in the elderly research group. Neurology 54, S10–15 (2000).

Isik, A. T. Late onset Alzheimer’s disease in older people. CIA 307 (2010) doi:10.2147/CIA.S11718.

Cutler, R. G. et al. Involvement of oxidative stress-induced abnormalities in ceramide and cholesterol metabolism in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 2070–2075 (2004).

Arimon, M. et al. Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation are upstream of amyloid pathology. Neurobiol. Dis. 84, 109–119 (2015).

Mielke, M., Vemuri, P. & Rocca, W. Clinical epidemiology of alzheimer’s disease:assessing sex and gender differences. CLEP 37 https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S37929 (2014).

Eckert, A. et al. Elevated vulnerability to oxidative stress-induced cell death and activation of caspase‐3 by the Swedish amyloid precursor protein mutation. J. Neurosci. Res. 64, 183–192 (2001).

Finkel, T. & Holbrook, N. J. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature 408, 239–247 (2000).

Perry, G. et al. Oxidative damage in alzheimer’s disease: the metabolic dimension. Intl J. Devlp Neurosci. 18, 417–421 (2000).

Halliwell, B. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), oxygen radicals and antioxidants: where are we now, where is the field going and where should we go? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 633, 17–19 (2022).

Zhu, X. et al. Oxidative stress signalling in alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1000, 32–39 (2004).

Chelikani, P., Fita, I. & Loewen, P. C. Diversity of structures and properties among catalases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. (CMLS). 61, 192–208 (2004).

Dröge, W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 82, 47–95 (2002).

Nimse, S. B. & Pal, D. Free radicals, natural antioxidants, and their reaction mechanisms. RSC Adv. 5, 27986–28006 (2015).

Mirończuk-Chodakowska, I., Witkowska, A. M. & Zujko, M. E. Endogenous non-enzymatic antioxidants in the human body. Adv. Med. Sci. 63, 68–78 (2018).

Birben, E., Sahiner, U. M., Sackesen, C., Erzurum, S. & Kalayci, O. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organ. J. 5, 9–19 (2012).

Chance, B., Sies, H. & Boveris, A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol. Rev. 59, 527–605 (1979).

Kou, J. et al. Peroxisomal alterations in alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 122, 271–283 (2011).

Semikasev, E., Ahlemeyer, B., Acker, T., Schänzer, A. & Baumgart-Vogt, E. Rise and fall of peroxisomes during Alzheimer´s disease: a pilot study in human brains. Acta neuropathol. commun. 11, 80 (2023).

Ali, F. et al. Brain Metabolite, Myo-inositol, inhibits catalase activity: A mechanism of the distortion of the antioxidant defense system in alzheimer’s disease. ACS Omega. 7, 12690–12700 (2022).

Habib, L. K., Lee, M. T. C. & Yang, J. Inhibitors of Catalase-Amyloid interactions protect cells from β-Amyloid-Induced oxidative stress and toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 38933–38943 (2010).

Lovell, M. A., Ehmann, W. D., Butler, S. M. & Markesbery, W. R. Elevated thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances and antioxidant enzyme activity in the brain in alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 45, 1594–1601 (1995).

Pappolla, M. A., Omar, R. A., Kim, K. S. & Robakis, N. K. Immunohistochemical evidence of oxidative [corrected] stress in alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol. 140, 621–628 (1992).

Wu, Y. H. & Hsieh, H. L. Effects of redox homeostasis and mitochondrial damage on alzheimer’s disease. Antioxidants 12, 1816 (2023).

Mao, P. et al. Mitochondria-targeted catalase reduces abnormal APP processing, amyloid production and BACE1 in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease: implications for neuroprotection and lifespan extension. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 2973–2990 (2012).

Behl, C. Hydrogen peroxide mediates amyloid β protein toxicity. Cell 77, 817–827 (1994).

Nell, H. J. et al. Targeted Antioxidant, Catalase–SKL, reduces Beta-Amyloid toxicity in the rat brain. Brain Pathol. 27, 86–94 (2017).

Mettupalayam Kaliyannan Sundaramoor, P. Kilavan Packiam, K. In vitro enzyme inhibitory and cytotoxic studies with evolvulus alsinoides (Linn.) Linn. Leaf extract: a plant from ayurveda recognized as Dasapushpam for the management of alzheimer’s disease and diabetes mellitus. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 20, 129 (2020).

Mangmool, S., Kunpukpong, I., Kitphati, W. & Anantachoke, N. Antioxidant and anticholinesterase activities of extracts and phytochemicals of syzygium antisepticum leaves. Molecules 26, 3295 (2021).

Alishir, A. & Kim, K. H. Antioxidant phenylpropanoid glycosides from Ginkgo Biloba fruit and identification of a new phenylpropanoid Glycoside, Ginkgopanoside. Plants 10, 2702 (2021).

Avcı, A. et al. Effects of Garlic consumption on plasma and erythrocyte antioxidant parameters in elderly subjects. Gerontology 54, 173–176 (2008).

Durak, İ. et al. Effects of Garlic extract consumption on blood lipid and oxidant/antioxidant parameters in humans with high blood cholesterol. J. Nutr. Biochem. 15, 373–377 (2004).

Ali Reza, A. S. M. et al. In vitro antioxidant and cholinesterase inhibitory activities of elatostema papillosum leaves and correlation with their phytochemical profiles: a study relevant to the treatment of alzheimer’s disease. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 18, 123 (2018).

Kamli, M. R., Sharaf, A. A. M., Sabir, J. S. M. & Rather, I. A. Phytochemical screening of Rosmarinus officinalis L. as a potential anticholinesterase and Antioxidant–Medicinal plant for cognitive decline disorders. Plants 11, 514 (2022).

Oyeleke, M. B. & Owoyele, B. V. Saponins and flavonoids from Bacopa floribunda plant extract exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects on amyloid beta 1-42-induced alzheimer’s disease in BALB/c mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 288, 114997 (2022).

Kim, Y. J. et al. Simultaneous quantification of four marker compounds in bauhinia coccinea extract and their potential inhibitory effects on alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Plants 10, 702 (2021).

Liu, J., Chandaka, G. K., Zhang, R. & Parfenova, H. Acute antioxidant and cytoprotective effects of Sulforaphane in brain endothelial cells and astrocytes during inflammation and excitotoxicity. Pharmacol. Res. Perspec. 8, e00630 (2020).

Iciek, M., Kwiecień, I. & Włodek, L. Biological properties of Garlic and Garlic-derived organosulfur compounds. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 50, 247–265 (2009).

Ruhee, R. T., Roberts, L. A., Ma, S. & Suzuki, K. Organosulfur compounds: A review of their Anti-inflammatory effects in human health. Front. Nutr. 7, 64 (2020).

Nillert, N. et al. Neuroprotective effects of aged Garlic extract on cognitive dysfunction and neuroinflammation induced by β-Amyloid in rats. Nutrients 9, 24 (2017).

Song, H. et al. Bioactive components from Garlic on brain resiliency against neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2019.8389 (2019).

Tedeschi, P. et al. Therapeutic potential of allicin and aged Garlic extract in alzheimer’s disease. IJMS 23, 6950 (2022).

Wang, X., Yang, Y. & Zhang, M. The vivo antioxidant activity of self-made aged Garlic extract on the d -galactose-induced mice and its mechanism research via gene chip analysis. RSC Adv. 9, 3669–3678 (2019).

Lee, Y. M. et al. Antioxidant effect of Garlic and aged black Garlic in animal model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr. Res. Pract. 3, 156 (2009).

Caro, A. A. et al. Effect of garlic-derived organosulfur compounds on mitochondrial function and integrity in isolated mouse liver mitochondria. Toxicol. Lett. 214, 166–174 (2012).

Gupta, V. B. & Rao, K. S. J. Anti-amyloidogenic activity of S-allyl-l-cysteine and its activity to destabilize alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils in vitro. Neurosci. Lett. 429, 75–80 (2007).

Kosuge, Y. et al. S-allyl-l-cysteine selectively protects cultured rat hippocampal neurons from amyloid β-protein- and tunicamycin-induced neuronal death. Neuroscience 122, 885–895 (2003).

Hansberg, W. Monofunctional Heme-Catalases. Antioxidants 11, 2173 (2022).

Putnam, C. D., Arvai, A. S., Bourne, Y. & Tainer, J. A. Active and inhibited human catalase structures: ligand and NADPH binding and catalytic mechanism 1 1Edited by R. Huber. J. Mol. Biol. 296, 295–309 (2000).

Kirkman, H. N. & Gaetani, G. F. Mammalian catalase: a venerable enzyme with new mysteries. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 44–50 (2007).

Zámocký, M. & Koller, F. Understanding the structure and function of catalases: clues from molecular evolution and in vitro mutagenesis. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 72, 19–66 (1999).

Palma, J. M. et al. Plant catalases as NO and H2S targets. Redox Biol. 34, 101525 (2020).

Purwar, N., McGarry, J. M., Kostera, J., Pacheco, A. A. & Schmidt, M. Interaction of nitric oxide with catalase: structural and kinetic analysis. Biochemistry 50, 4491–4503 (2011).

Privalov, P. L. & Gill, S. J. Stability of Protein Structure and Hydrophobic Interaction. in Advances in Protein Chemistry vol. 39 191–234 Elsevier, (1988).

Oda, K. & Kinoshita, M. Physicochemical origin of high correlation between thermal stability of a protein and its packing efficiency: a theoretical study for Staphylococcal nuclease mutants. BIophysics 12, 1–12 (2015).

Chung, L. Y. The antioxidant properties of Garlic compounds: allyl Cysteine, Alliin, Allicin, and allyl disulfide. J. Med. Food. 9, 205–213 (2006).

Hashimoto, M., Nakai, T., Masutani, T., Unno, K. & Akao, Y. Improvement of Learning and Memory in Senescence-Accelerated Mice by S-Allylcysteine in Mature Garlic Extract. Nutrients 12, 1834 (2020).

Gasparello, J. et al. Aged Garlic extract (AGE) and its constituent S-Allyl-Cysteine (SAC) inhibit the expression of Pro-Inflammatory genes induced in bronchial epithelial IB3-1 cells by exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein and the BNT162b2 vaccine. Molecules 29, 5938 (2024).

Gupta, P. et al. S-allyl cysteine: A potential compound against skeletal muscle atrophy. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 1864, 129676 (2020).

Hadwan, M. H. Simple spectrophotometric assay for measuring catalase activity in biological tissues. BMC Biochem. 19, 7 (2018).

Iwase, T. et al. A simple assay for measuring catalase activity: A visual approach. Sci. Rep. 3, 3081 (2013).

Abraham, M. J. et al. High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1–2. GROMACS, 19–25 (2015).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Jorgensen, W. L., Chandrasekhar, J., Madura, J. D., Impey, R. W. & Klein, M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 (1983).

Hess, B., Bekker, H., Berendsen, H. J. C. & Fraaije, J. G. E. M. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 18, 1463–1472 (1997).

Darden, T., York, D. & Pedersen, L. Particle mesh ewald: an N ⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092 (1993).

Nielsen, L. et al. Effect of environmental factors on the kinetics of insulin fibril formation: Elucidation of the molecular mechanism. Biochemistry 40, 6036–6046 (2001).

Mittal, S. & Singh, L. R. Macromolecular crowding decelerates aggregation of a β-rich protein, bovine carbonic anhydrase: a case study. J. Biochem. 156, 273–282 (2014).

Acknowledgements

S.Y., K.S., and L.R.S., would like to thank CSIR for providing financial support to S.Y. in the form of fellowship (09/476(0100)2020-EMR-I).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.R.S. and K.S. conceived idea and design of experiment. S.Y., K.S., A.G., P.A. and A.K. performed experiments and curate data. S.Y., K.S. A.G. and L.R.S. wrote manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yumlembam, S., Singh, K., Gupta, A. et al. S-allyl cysteine and alliin enhance catalase activity and prevent aggregation to counter oxidative stress in alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep 16, 486 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30035-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30035-z