Abstract

In cognitive radio networks (CRNs), collaborative spectrum sensing has emerged as a promising technique for detecting primary user activity. However, the effectiveness of user cooperation is compromised by the presence of malicious users, specifically False Sensing Users (FSUs). FSUs undermine the effectiveness of collaborative sensing by providing misleading information to the fusion center (FC) in an attempt to selfishly access spectrum resources. Therefore, this study focuses on three types of FSUs that exhibit distinct attack patterns: No False Sensing (NFS, i.e., Always-No), Yes False Sensing (YFS), and Yes/No false sensing (YNFS) users. The FC collects reports from both FSUs and legitimate sensing users at varying time intervals. This study employs a denoising autoencoder (DAE) to enhance sensing reliability by mitigating the effects of abnormal sensing reports and noise disturbances at the FC. While current validation employs synthetic data that closely approximates theoretical CRN conditions, real-world RF validation represents an important direction for future work. The autoencoder produces cleaned soft energy data, which is fed into a machine learning (ML) classifier to estimate channel availability and accumulate global decisions. The present study assesses the effectiveness of various classification techniques, including decision trees (DT), k nearest neighbor (KNN), neural networks (NN), ensemble classification (EC), Gaussian naive Bayes (GNB), and random forest classifier (RFC), to classify channel states. Additionally, this paper aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of these methods. The integration of DAE and EC yields high accuracy, F1 score, and Matthew’s Correlation Coefficient (MCC), leading to a reliable global decision at the FC with minimal sensing error.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To alleviate the shortage of radio spectrum resources, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has sanctioned cognitive radio (CR) technology, which has the potential to improve the efficiency of spectrum utilization1. The term “cognitive” in CR technology is derived from the Latin “cognoscere,” meaning to learn or become aware, reflecting the system’s ability to perceive its environment2. The spectrum sensing phase of the CR process is a critical element that requires user collaboration to achieve optimal performance. However, multipath fading and shadowing effects may lead to reduced sensing accuracy. Two major cooperative schemes available for reliable sensing of the primary user (PU) channel are centralized and distributed. This study focuses on the centralized collaborative approach, wherein a fusion center (FC) collects sensing reports from multiple secondary users to make a global decision3. Recent work4 focuses on optimizing cooperative spectrum sensing (CSS) in energy-harvesting cognitive radio networks (EH-CRNs). The authors derive the optimal decision threshold for the fusion center (FC) to maximize throughput while also meeting energy and collision constraints.

The increasing demand for wireless spectrum, driven by the proliferation of 5G networks and mobile devices, underscores the urgent need for CRNs to efficiently manage spectrum resources5. For EH-CRNs,6 shows that secondary throughput depends critically on balancing sensing energy and data availability. The study further demonstrates that cooperative sensing outperforms non-cooperative approaches under Markovian energy constraints. A novel hybrid algorithm was developed for spectrum allocation in TV White Space networks by combining the Firefly, Genetic (GA), and Ant Colony Optimization algorithms. The proposed method demonstrated superior performance over traditional hybrids, showing significant improvements in both throughput and objective function value7. The maximization of performance in cooperative EH-CRNs is studied in8. The authors show that significant gains are achieved through joint cooperation on energy statistic and optimal time allocation between the primary user (PU) and the secondary user (SU). Wideband spectrum sensing techniques have been extensively investigated. Among them, the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) has proven particularly effective for compressive sensing and recovery in 5G networks9. Cooperative sensing is beneficial in CR networks, but the presence of false sensing users (FSUs) raises security concerns for the collaborative network. FSUs may deliberately provide incorrect sensing information to the FC to disrupt global decisions and potentially gain access to valuable spectrum resources10. Research studies have explored distinct types of deceitful and false users that could jeopardize the FC’s decision. This includes individuals with malicious intent, such as malicious users (MUs), PU emulation attackers, Byzantine users, and jammers11,12,13,14. In contrast, collusion attacks involve multiple attackers coordinating to launch more potent attacks against the FC15,16.

In recent years, spectrum sensing techniques have transitioned from traditional methods such as energy detection (ED) to more advanced approaches that involve machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), reinforcement learning (RL), and artificial intelligence (AI). These sophisticated techniques offer enhanced performance in challenging environments, significantly improving detection accuracy and robustness compared to conventional methods17. They provide improved accuracy, especially in dynamic and noisy conditions where conventional techniques often struggle. Furthermore, these methods enhance CRN performance by automatically identifying signal patterns and characteristics to make accurate decisions about frequency availability. A novel convolutional neural network (CNN) and tensor network (TN)-based spectrum sensing approach is introduced, using local and global patterns in the spectrum data to achieve superior detection performance and efficient spectrum utilization18. The K nearest neighbor (KNN) algorithm in19 has examined the accuracy, sensitivity, and confusion matrix to evaluate the classification performance of the PU channel. Similarly, multiple ML techniques, including KNN, are proposed in20 to detect PU emulations in a mobile CRN environment. This method involves a prior learning process that creates a dataset using parameters such as signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and entropy of the received power signal. Notably, it does not require previous knowledge of modulation type or radio frequency characteristics.

The integration of CNNs and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) in spectrum sensing has demonstrated superior performance over traditional methods, capturing spatial and temporal patterns in CR systems21. DL has also demonstrated potential for spectrum sensing. For instance,22 proposes a novel DL-based sensing detector that uses CNN and long-short-term memory (LSTM) to exploit energy correlation features and PU patterns without relying on assumptions from the signal-noise model. Similarly, DL is used to improve the spectrum sensing classification performance by incorporating prior knowledge of PU with LSTM layers in23. In24, a multi-agent RL framework using two distributed execution algorithms is proposed to address the complicated decision-making process for cognitive unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) by coupling sensing and access strategies. In this framework, the spectrum sensing phase is performed cooperatively, and binary sensing results are exchanged. Likewise,25 proposes a CSS scheme based on RL to improve the sensing performance in dynamic CR networks. Here, each SU acts as an agent that learns the behavior of channels and neighbors, which enhances detection efficiency while decreasing scanning overhead and reducing access delay. Recent work26 proposes an adjusted deep deterministic policy gradient (A-DDPG) algorithm for the ambient backscatter-assisted hybrid underlay CRN. Meanwhile,27 develops a hybrid action and energy penalty DDPG (HAEP-DDPG) approach for age of information (AoI) minimization in EH-CRNs. Although these deep reinforcement learning (DRL) methods26,27 advance energy-efficient CRNs, they do not address FSU mitigation as our approach.

Virtual CSS is proposed to overcome power limitations in UAV networks, using sequential decision fusion and ML techniques28. In29, the network is trained using a neural network (NN) based on the multilayer perceptron model to reduce the prediction error and mitigate the impact of collision factors. Furthermore,30 proposes a CNN-based approach for spectrum sensing. This method uses sensing samples from different SUs as input to address the significant impact that combining different samples has on detection performance. In10, an approach uses a genetic algorithm (GA) to determine an optimal weighting coefficient vector for a GA-based soft combination scheme, which is then used to make the final decision. Additionally,31 presents a hopping sequence (HS) module to increase the probability of detection when PUs and SUs are mobile. Finally, cooperative sensing is used in both32 and33 to reduce uncertainty. These studies employ the spatial variability of SUs and use support vector machines (SVMs) to draw a global conclusion about the presence or absence of PUs.

Although ensemble learning and optimization techniques have been explored for CRNs, such as semi-soft stacking for single-attack scenarios34 and DRL for EH-CRNs26, existing approaches suffer from two key limitations. First, they are ineffective against dynamic adversaries. Second, they lack a unified mechanism to mitigate No False Sensing (NFS, i.e., Always-No), yes false sensing (YFS), and adaptive yes/no false sensing (YNFS) attacks. As evidenced in Table 1, our denoising autoencoder (DAE)-based ensemble classifier (EC) (DAEEC) is the first to demonstrate robustness against this full attack spectrum. Our approach uniquely combines two components: (1) DAE-based anomaly removal using sparse encoding with a latent 2-neuron space, and (2) EC classification with a 30-decision tree (DT) ensemble. This combination achieves 99.1% accuracy under 100% attack rates, which represents a 4.9% improvement over DE-ML35 and a 7.2% improvement over particle swarm optimization (PSO)36 under equivalent conditions.

-

To our knowledge, this represents the first framework integrating a DAE with an EC in a dedicated dual-stage pipeline. While ensemble and hybrid techniques exist34,36, our DAEEC framework is specifically designed to simultaneously mitigate static attacks (NFS, YFS) and adaptive YNFS attacks. This is achieved through a two-stage process: (1) DAE-based denoising with regularization of L2=0.01 and 0.1 sparsity reduces adversarial perturbations, followed by (2) EC classification with a learning rate of 0.1. Our method achieves 99.1% accuracy at SNR=-10dB under 100% attack rates, demonstrating improved robustness and efficiency compared to prior ensemble34 and optimization36 methods.

-

Our model adopts soft energy statistics from cooperative users and PU activities as a dataset for training and testing. The feature vector comprises the sensing reports of honest and fraudulent users in the assumed collaborative environment. This study employs an EC to classify energy features, determining whether the PU channel is active or free.

-

The first step in our methodology involves cleaning the sensing data collected at the FC to remove FSU frauds and channel disturbances. We accomplish this by using DAE, which gathers and purifies the user sensing statistics for further processing. The resulting cleaned data is then utilized as input for the EC.

-

Our proposed approach improves detection accuracy by mitigating three key types of false sensing attacks: NFS, YFS, and random YNFS. These attacks manifest in distinct ways: YFS users persistently transmit high-energy signals to induce false alarms, while NFS users deliberately report low-energy statistics to mask spectrum occupancy. To assess the denoising effectiveness, we use the mean square error (MSE) metric to compare the input data with the reconstructed data after cleaning. The classification performance of the EC is evaluated separately using accuracy, F1-score, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC). The strong classification performance of the EC led to its selection for global decision making at the FC. Furthermore, we compare the error probabilities of our ECDAE model against several schemes, including the highest gain scheme (HGS), identical gain scheme (IGS), PSO, and CNN. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of ECDAE against NFS, YFS, and YNFS attacks under varying attack rates.

This paper is organized into the following sections: Section System model outlines the system model. Section Proposed mechanisms for denoising and grouping data presents the proposed autoencoder technique for catching and removing sensing abnormalities and the ensemble classification method for making decision. Section Numerical results and discussions presents the numerical results and discussions. The paper concludes in section Conclusion.

System model

Figure 1 shows the single-PU case studied here. The FC’s modular design allows natural extension to multiple PUs by (1) Deploying parallel DAE instances (one per PU band) and (2) Modifying the classifier for multi-label output. These extensions require future validation, but are architecturally supported. In the proposed cooperative model, multiple SUs report the presence and absence sensing data of the PU to the FC. The sensing energies of the reporting users undergo denoising with a denoising autoencoder before being transferred to the EC to estimate the channel. The cooperative environment in this paper is also protected against false detection notices from YFS and NFS users. The sensing notifications are collected from the normal and FSUs, and their reported energy distribution is illustrated in Fig. 2. The normal/honest user in Fig. 2(a) reports a low energy signal in \({H}_{0}\), when the channel is detected as free, and reports a high energy signal when the PU is sensed to be available under \({H}_{1}\). As shown in Fig. 2(b), a YFS attacker reports high-energy signals to the FC under both hypotheses H0 and H1. Conversely, an NFS attacker, shown in Fig. 2(c), consistently reports low-energy signals, regardless of the PU’s actual activity. Similarly, the random YNFS user report switches between the YFS and NFS probabilistically in Fig. 2(d). For YNFS users, all attackers coordinate within each sensing interval - they collectively adopt either NFS or YFS behavior for that entire interval based on a random decision (probability 0.5 each). This coordinated per-interval behavior represents a collusive attack strategy while maintaining memoryless characteristics across different sensing intervals. Consistent high-energy reports from YFS users can cause false alarms, unnecessarily preventing SUs from transmitting and thus lowering their data rates. Conversely, persistent low-energy reports from NFS users increase the risk of missed detections, leading to interference with the PU. The random behavior of YNFS users combines both drawbacks, degrading both SU throughput and PU protection. Consequently, it is critical to eliminate the impact of corrupted sensing reports at the FC. These corruptions are caused by two primary sources: falsifying users (NFS, YFS, and adaptive YNFS attackers) and the wireless channel’s additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN).

In the assumed centralized cooperative network, sensing participants report their local observations to the FC (central node) to arrive at a more appropriate final decision. The \({{j}^{th}}\) user presents the \({{H}_{0}}\) and \({{H}_{1}}\) hypotheses as

Here, m is the total number of sensing participants, and \(k = 2BT_s\) is the number of samples per sensing interval, where B is the bandwidth and \(T_s\) is the SU sensing period. During the \(l^{th}\) sample, the signal received from the \(j^{th}\) user is represented as \(x_j(l)\), where \(H_0\) and \(H_1\) represent the absence and presence inferences of PU activity. The channel gain for the \(j^{th}\) user is indicated by \(g_j\), and c(l) describes the PU signal with variance \(\sigma _s^2\) and mean zero. The AWGN between the PU and the \(j^{th}\) sensing user is given by \(v_j(l)\), with a mean of zero and variance \(\sigma _{v_j}^2\).

The energy statistic for the \(i^{th}\) sensing interval (\(i \in \{1,2,\ldots ,n\}\), where n is the total number of sensing intervals) is obtained by accumulating energy over all k samples within that interval:

Equation (2) divides each sensing interval into k samples. As a result, the energy reports provided by SUs tend to follow a Gaussian distribution for both hypotheses as in (3) under satisfactory sensing samples in this study

Here, \(\left( {{\mu }_{0}},\,\sigma _{0}^{2} \right)\) and \(\left( {{\mu }_{1}},\,\sigma _{1}^{2} \right)\) are the mean and variance results of the energy distribution for the \({{H}_{0}}\) and \({{H}_{1}}\) hypotheses, while \({{\eta }_{j}}\) is \({{j}^{th}}\) user channel SNRs.

Proposed mechanisms for denoising and grouping data

The proposed approach consists of three essential steps. In step 1, soft energy reports are collected from regular and fraud-sensing data users in the FC. In step 2, these sensing reports are used to train a DAE to eliminate disturbances caused by both channel noise and FSUs. The purified data from the autoencoder are then used to train and test an EC in step 3. Finally, the error probability of the proposed method is compared with that of traditional schemes, including HGS, IGS, PSO, DE-ML, and CNN.

Step-1: data retrieval

The FC constructs a history reporting matrix comprising the soft energy reports collected from all SUs. This matrix is defined as follow.

The \({{j}^{th}}\) user sensing statistics (\({{s}_{ij}}\)) in (3) are reported to the FC during the \({{i}^{th}}\) interval. The FC collects spectrum sensing data from all m SUs (including normal and FSUs) over the n sensing intervals. In step 2 of the proposed method, the impact of channel noise and FSUs is mitigated. For CRNs, ML techniques can learn from historical sensing data to make robust predictions about PU activity, even in the presence of deceptive attacks.

Step-2: data cleansing using a DAE

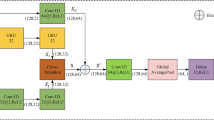

This section focuses on using a DAE to improve the quality of the user-sensing data retrieved in Step 1. The DAE is designed to reduce the dimensionality of the data and eliminate irregularities caused by both FSU sensing reports and inherent wireless channel noise. A DAE is a fully connected feedforward NN trained in an unsupervised manner to reconstruct a cleaned version of its input. As shown in Fig. 3, the DAE model comprises three primary components: an encoder, a compressed latent space, and a decoder.

The encoder maps the corrupted input vector \({s} \in {R}^{m}\) (where m is the number of users) to a lower-dimensional latent representation \({h} \in {R}^{n}\) (where n is the number of nodes in the latent space and \(n < m\)) using a non-linear transformation:

where \(f(\cdot )\) is a nonlinear activation function (e.g. logistic sigmoid), \({W}_{1} \in {R}^{n \times m}\) is the weight matrix of the encoder, and \({b} \in {R}^{n}\) is the bias vector.

The decoder then maps the latent representation h back to the original feature space to produce the reconstructed output vector \({\hat{s}} \in {R}^{m}\):

Here, \(g(\cdot )\) is the activation function of the decoder (for example, a pure linear function, ‘purelin‘), \({W}_{2} \in {R}^{m \times n}\) is the decoder weight matrix, and \({c} \in {R}^{m}\) is the decoder bias vector. To improve learning efficiency, weight matrices are often tied, that is, \({W}_{2} = {W}_{1}^{T}\).

Given a training set of N sensing reports \(\left\{ {s}^{(i)} \right\} _{i=1}^{N}\), the DAE is trained to find the optimal parameters \(\varvec{\psi } = \left\{ {W}_{1}, {b},{c} \right\}\) that minimize the loss of MSE reconstruction:

This objective function forces the DAE to learn robust features from the input data, which effectively filters out noise and adversarial perturbations introduced by FSUs. This process results in a cleaned version of the sensing reports.

Step-3: ensemble classifier for classification

Once the DAE model has trained and the data have been pre-processed, it is used as input for the EC shown in Fig. 4. An EC is an ensembling technique that combines the output of multiple classifiers to improve the accuracy of prediction. By combining multiple weak classifiers, an EC can compensate for the individual shortcomings of each base learner, often producing more accurate and robust predictions than any single classifier. The ensembling approach can be applied to various classifiers, such as DT, logistic regression models, or SVM. Standard techniques for combining weak classifier output include voting, bagging, and boosting. The ensembling of results of multiple classifiers is a preferable approach, as individual classifiers can produce biased predictions34.

The proposed DAEEC derives its effectiveness from two synergistic mechanisms: (1) The DAE sparse encoding filters channel noise and FSU distortions through its compressed latent representation (2-neuron hidden layer), and (2) The AdaBoost ensemble combines multiple decision trees to mitigate individual classifier biases-mirroring the cooperative diversity gain in multi-user sensing. This architecture provides three key engineering advantages: First, it adapts dynamically to SNR variations without threshold recalibration. Second, it maintains stable reconstruction loss even under 100% FSU attacks where traditional schemes fail. Third, its efficient design (2 hidden DAE neurons + 30 decision trees) achieves higher detection accuracy with lower computational overhead than pure CNN approaches, making it practical for real-time CRN deployment.

The cleaned sensing dataset output by the DAE is used as the input for the EC. The dataset, denoted as T, is represented as T =\(\left\{ \left( {{s}_{ij}},\,{{y}_{i}} \right) \right\} _{i=1}^{n},\,{{s}_{ij}}\in {{\Re }^{n}},\,{{y}_{i}}\in \left\{ -1,\,\,1 \right\}\). A class label of 1 for \({{y}_{i}}\) indicates the presence of PU activity, while a label of \(-1\) indicates its absence. The training set T is represented by a matrix with dimensions \(n\times (m+1)\), and its space is defined as \({T} \in {{\Re }^{n\times (m+1)}}\).

The feature vectors \({{s}_{1}}\), \({{s}_{2}}\), and \({{s}_{n}}\) represent the clean and denoised input features obtained from the autoencoder versus the observations of the m users. The training data for the EC, denoted as T, consists of S and Y submatrices. The n feature matrix S contains the sensing data for the m users, while Y is a predicted output with information about the \({{H}_{0}}\) and \({{H}_{1}}\) hypotheses and has a dimension of \(n\times 1\).

In the AdaBoost algorithm, each classifier is assigned a decision weight based on the predictions made by the preceding classifiers. This technique is used to enhance the accuracy of the overall model and is commonly referred to as boosting.

In the given context, \({{h}_{p}}({{s}_{i}})\) represents the predicted result of the \({{p}^{th}}\) classifier with its assigned weight \({{\alpha }_{p}}\). In addition, we add the predicted value \({{h}_{r}}({{s}_{i}})\) and the optimal weight \({{\alpha }_{r}}\) of the \({{r}^{th}}\) classifier to the overall prediction.

Using the value obtained from (9), we can express the statement mentioned above as follows:

We seek a closed-form formula to assign a value to the weight \(\alpha _r\) in the AdaBoost algorithm. This weight is used to aggregate the predictions of the r classifiers, where the predicted value for a given sample \({s}_{i}\) is denoted as \({{e}_{r}}\left( {{s}_{i}} \right)\). The objective is to minimize the total prediction error through an optimal selection of \(\alpha _r\).

Due to the fact that \({{W}_{c}}\) is defined as the difference between the total weight sum W and the weight of errors \({{W}_{e}}\), we can conclude that

The final representation of the weight \({{\alpha }_{r}}\) is given by the following expression:

The weighted error rate of the weak classifier \({{h}_{r}}\) is indicated by \({{e}_{m}}={{\,}^{{{W}_{e}}}}{{/}_{W}}\) in the given context.

Step-4: final decision

In this section, the system generates the final decision on channel availability and busy states using various combination schemes. An IGS is one combination that assigns equal weight to individual sensing reports and deals with the users equally in finalizing the decision. Similarly, the HGS gives more importance to the user with high channel gain. The cumulative decision of the system using the IGS combination is as follows:

The detection and false alarm probabilities \({{P}_{d\text \!\!\_\!\!\text { IGS}}}\) and \({{P}_{f\text \!\!\_\!\!\text { IGS}}}\) of the IGS according to the cumulative decision \({{C}_{IGS}}(i)\) are

The HGS combination multiplies each user-received report by its branch gain. Therefore, a high weight is assigned to the user sensing with high SNR and a low weight is assigned to the user sensing with low SNR values. The cumulative decision \({{C}_{HGS}}(i)\) at the FC using the HGS scheme is as follows

where \({{w}_{j}}=\frac{\eta (j)}{\sum \limits _{j=1}^{m}{\eta (j)}}\). The cooperative detection and false alarm probabilities of the HGS scheme are measured based on the reports from individual sensors as

Unlike the IGS and HGS combinations, the DAEEC scheme forms its cumulative decision using the DAE reconstructed data \(\hat{s}_{i}\) in the output. The cumulative decision of the DAEEC at the FC is as follows:

where \({{C}_{DAEEC}}\) is the cumulative response of the DAEEC. The detection and false alarm probabilities of the DAEEC are expressed as

Figure 4 illustrates the DAE-based pipeline from end to end for cleaning sensing reports and classifying PU activity, from raw energy measurements to final detection. The system begins with the PU transmitter (represented by the antenna symbol) and multiple SUs (including normal SUs and FSUs) submitting their energy reports. The raw measurements first go through a feature extraction stage before entering the DAE component. The DAE itself consists of three key blocks: (1) an encoder with logistic sigmoid activation that compresses the noisy input, (2) a compact latent space that captures essential features by filtering out noise and malicious perturbations, and (3) a decoder with linear activation that reconstructs clean energy estimates. Reconstruction performance was optimized through extensive experimentation, achieving a balance between denoising capability and feature preservation using L2 regularization and sparsity constraints. The cleaned features then feed into an EC that uses AdaBoost with 30 DT learners, where the learning rate of the boosting mechanism (0.1) was carefully tuned to prevent overfitting while maintaining sensitivity to subtle PU transmission patterns. This dual stage approach effectively addresses both the challenge of unreliable reports (through DAE-based cleaning) and the need for robust detection (through EC), as evidenced by the experimental results in subsequent sections.

Numerical results and discussions

Dataset creation and pre-processing

To evaluate the proposed DAEEC framework, we generated a synthetic dataset in MATLAB that emulates realistic CRN conditions under various attack scenarios. The simulation parameters used for dataset generation are summarized in Table 2, including key settings for system configuration, attack parameters, SNR conditions, DAE configuration, and classifier hyperparameters. The dataset consists of 20,000 feature vectors, each containing energy readings from 10 cooperative SUs (columns 1-10) and a binary PU state label (column 11). PU states (\(H_0\): absent, \(H_1\): present) were generated with perfect ground-truth knowledge using a balanced distribution (\(P(H_1) = P(H_0) = 0.5\)). The energy values were simulated according to Gaussian distributions: \({\mathcal {N}}(\mu _0=k,\sigma _0^2=2k)\) under \(H_0\) and \({\mathcal {N}}(\mu _1=k(\eta _j+1),\sigma _1^2=2k(\eta _j+1))\) under \(H_1\), with SNRs \(\eta _j\) varying from -15dB to 4dB across users to ensure diversity.

The dataset incorporates two attack configurations: (1) fixed-position attacks where specific columns (e.g., 5-7) consistently contained FSUs and (2) random-position attacks where MUs were assigned dynamically per sensing interval. Three attack types were modeled: NFS users consistently report \(H_0\) energies (\({\mathcal {N}}(k,2k)\)), YFS users always transmit \(H_1\) energies (\({\mathcal {N}}(k(\eta _j+1),2k(\eta _j+1))\)), and YNFS attackers randomly switch between both strategies. For each sensing report, the YNFS attacker independently and randomly chooses to behave as an NFS attacker with probability 0.5 or as a YFS attacker with probability 0.5. This creates a memoryless process where the attack behavior in each sensing interval is independent of previous intervals (non-Markovian), though all YNFS users are coordinated to use the same attack strategy within each interval. Table 3 summarizes the complete structure of the dataset.

The ED process uses 300 samples per sensing period to ensure reliable Gaussian approximations according to the Central Limit Theorem, while maintaining practical computational constraints (40 kHz bandwidth \(\times\) 1 ms sensing). This configuration balances detection performance (\(P_d > 0.9\) at -15 dB SNR) with processing efficiency, as preliminary tests showed 150 samples degrade \(P_d\) by 7% and increase false alarms by 4%. The 2-neuron DAE architecture is specifically optimized for this sample size.

The synthetic dataset accurately replicates real-world CRN conditions through (a) physically derived energy distributions based on detection theory, (b) experimentally validated attack models, and (c) comprehensive SNR coverage including challenging low-SNR regimes. All simulations used fixed random seeds to guarantee reproducibility. The 2-neuron DAE architecture was specifically optimized for this sample size and noise distribution.

DAE architecture and performance

The sensing data undergoes denoising and cleaning using a DAE trained on a dataset of 20,000 feature vectors, which includes energy readings from both normal and FSU (NFS and YFS categories) alongside actual PU states as labels. The input data, comprising raw energy reports from 10 users, is split into 80% training sets and 20% test sets, with Gaussian noise (noise level = 0.15) added to the training data to improve robustness. The DAE architecture features a 2-neuron hidden layer optimized for generalization, utilizing logistic sigmoid (encoder) and linear (decoder) activation functions to process bounded energy values and enable linear reconstruction, respectively. Training spans 1500 epochs using a combined MSE-sparse loss function (msesparse). The loss function is strengthened by regularization of L2 (0.01) and sparsity constraints with a proportion of 0.1 and a regularization weight of 1 to prevent overfitting. The bottleneck structure forces the DAE to learn only essential binary features (PU presence/absence) while removing noise and attack artifacts. This matches the fundamental \(H_0\)/\(H_1\) discrimination task, where excessive capacity could capture adversarial perturbations. Reconstruction performance is further evaluated under adversarial conditions, where NFS users (always reporting low energy) and YFS users (always reporting high energy) attack at rates of 10%–100%. Figures 5(a)–(d) demonstrate that the DAE achieves stable convergence, with loss values decreasing monotonically as the epochs increase. In particular, the impact of two FSU scenarios in Figures. 5(b) and 5 (d) show only a slight increase in loss compared to the cases of single attack in Figures. 5(a) and 5 (c), confirming the DAE’s resilience even at 100% attack rates. The denoised outputs are subsequently fed to downstream classifiers, ensuring reliable spectrum sensing despite adversarial interference.

The DAE achieves consistent reconstruction quality under maximum attack intensity (100% FSU), with the mean MSE remaining below 0.007 in all scenarios (Table 4). The low median errors (less than 0.0002) demonstrate that most samples are reconstructed with near perfect accuracy, though rare outliers (max MSE=1) occur when multiple attackers collide.

Hyperparameter analysis (Fig. 6) confirms that a minimal 2-neuron DAE used throughout this work achieves near-optimal MSE (0.00068 tests, 500 epochs) with minimal computation (6.3s). Although larger models (up to 14 neurons) marginally improve accuracy (less than 1%), their 3-5\(\times\) longer training times are unjustified for our task. The 80:20 split (consistent with DAE recommendations) ensures robust generalization even for tiny architectures.

Classifier selection

The denoised dataset produced by the DAE was initially evaluated using multiple classification algorithms, including DT, KNN, Random Forest Classifier (RFC), NN, and Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB), along with ensemble-based methods such as RUSBoost Trees and Bagged Trees. However, as demonstrated in Table 5 (80% training, 20% testing) and Table 6 (70% training, 30% testing), the EC consistently outperforms all other classifiers in all metrics: accuracy, F1 score, and MCC in both training and testing phases.

For example, with an 80%-20% split, the EC achieves 99.13% test accuracy, a 99.03% F1 score, and 98.00% MCC, surpassing even the second best performer, RUSBoost Trees (99.03% accuracy, 98.94% F1 score, and 97.80% MCC). Similarly, in the 70-30 split, the EC achieves 99.77% accuracy, 99.48% F1 score, and 98.93% MCC, further solidifying its robustness. In contrast, traditional classifiers such as DT, GNB, and NN exhibit significantly lower performance (e.g., DT: 96.97% accuracy, 96.87% F1 score, 95.66% MCC), while ensemble variants such as Bagged Trees and RUSBoost Trees, although competitive, still fall short of the results of the EC.

Given this clear performance gap, the EC was selected as the final classifier for global decision-making in our proposed system. The inferior accuracy, F1 scores, and MCC values of other classifiers make them unsuitable for reliable spectrum sensing, while the consistent superiority of EC ensures high-confidence predictions. This strategic selection aligns with the goal of maximizing detection reliability while minimizing uncertainty in dynamic environments.

Although RUSBoost and Bagged Trees demonstrate competitive performance, our proposed AdaBoost-based EC is preferred for practical deployment in CRNs due to three key advantages: (1) lower computational complexity during both training and inference, making it suitable for resource-constrained edge devices; (2) simpler hyperparameter tuning compared to other ensembling methods with extensive parameter space; and (3) more interpretable decision-making through its weighted voting mechanism. These practical considerations make our ensemble method better aligned with the real-time requirements and hardware limitations of spectrum sensing systems while still maintaining marginally superior detection performance.

To provide robust statistical validation, we conducted a bootstrap analysis in Table 7 with 500 iterations on the complete dataset of 20,000 sensing reports. This analysis calculates 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all performance metrics and assesses statistical significance through paired t-tests.

The bootstrap analysis reveals that our proposed EC not only achieves the highest performance but also demonstrates statistical significance against all baseline methods. The tight confidence intervals further confirm the reliability and consistency of our ensemble approach across different data splits.

Final sensing performance

For a comparative baseline, we implemented a standard 1D CNN. The architecture consisted of two 1D convolutional layers (with 16 and 32 filters, kernel size 3, ReLU activation, and batch normalization), each followed by max-pooling. The feature maps were processed by a global average pooling layer and two fully connected layers (32 and 2 units) for the final classification. The model was trained for 30 epochs using the Adam optimizer (initial learning rate 0.001, batch size 128) with a step decay learning rate schedule and regularization of L2.

1 NFS attackers scenario

Figure 7 demonstrates the performance of DAEEC against a single NFS attacker at the 100% attack rate. The proposed method achieves near-zero error probabilities (0.0002 at -10 dB SNR), significantly outperforming CNN (0.01128), PSO (0.00254) and DE-ML (0.0017). The curve shows the rapid convergence of DAEEC to optimal performance between -15dB and -10dB SNR.

2 NFS attackers scenario

Figure 8 reveals the robustness of DAEEC against coordinated attacks. Although maintaining a 0.0002 error at -6 dB SNR, CNN degrades sharply to 0.0492, demonstrating the vulnerability of traditional DL to multiple attackers. The plot clearly shows the stable performance of DAEEC in all SNRs compared to other methods.

1 YFS attacker scenario

Figure 9 presents the results for a single YFS attacker. The DAEEC error probability (0.0004 at -10dB) remains 2-4 times lower than the alternatives. The consistent gap between the DAEEC curve and others demonstrates its effectiveness against always-yes attacks.

2 YFS attackers scenario

Figure 10 shows DAEEC maintaining improved performance against multiple YFS attackers. Traditional schemes (IGS/HGS) fail catastrophically (HGS error of 0.0015 at -6dB), while the DAEEC curve remains consistently low throughout the SNR range.

1 YNFS attacker scenario

Critically, this robustness extends to mixed-behavior attackers (YNFS). Figure 11 illustrates the DAEEC’s handling of stochastic attacks. With error probability (0.0002 at -6 dB SNR), it outperforms DE-ML (0.001) and CNN (0.0034). The plot shows the stability of DAEEC against unpredictable attack patterns.

2YNFS attackers scenario

Figure 13 demonstrates continued effectiveness of DAEEC against multiple stochastic attackers (0.00022 error), while CNN (0.00139) and PSO (0.00023) show significant performance degradation. The parallel curves indicate consistent behavior across SNRs.

The DAEEC’s two-stage design-DAE preprocessing followed by EC proves essential to handling adversarial diversity. By filtering noise and FSUs regardless of attack type, it avoids the brittleness of monolithic DL models (e.g., CNN’s 300% error increase under 2 NFS attacks in Fig. 8) and heuristic methods (e.g., PSO’s saturation at 0.001 error for YNFS). Notably, the 80:20 train-test split (used consistently) ensures generalization even for minimal 2-neuron architectures, as validated in our hyperparameter analysis. These results solidify DAEEC as a suitable choice for adversarial environments, combining low-latency decisions with attack-agnostic accuracy.

Statistical analysis of robustness across attack scenarios

The performance evaluation thus far has presented results for each attack scenario independently. To provide a consolidated statistical view of each algorithm’s robustness and consistency, we treated the six attack scenarios (1NFS, 2NFS, 1YFS, 2YFS, 1YNFS, 2YNFS) as independent trials. The error probability at SNR = -10 dB was extracted from each scenario for every algorithm. Figure 13 presents a box plot of this data.” ”The plot reveals two key insights: (1) DAEEC achieves the lowest median error, and (2) crucially, it also exhibits the smallest interquartile range (IQR). This smallest IQR signifies that DAEEC’s performance is not just better on average, but also significantly more reliable and consistent across different types and numbers of attackers. While other algorithms like CNN show high variability (large IQR and long whiskers), making their performance unpredictable, DAEEC provides dependable superiority under all tested adversarial conditions.

Box plot of error probability at SNR = -10 dB across six independent attack scenarios. The central mark indicates the median, the box represents the inter-quartile range (IQR, 25th to 75th percentile), and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data points. The plot demonstrates that the proposed DAEEC not only achieves the lowest median error but also the smallest variance (tightest IQR).

Complexity-robustness trade-off analysis

Our framework carefully balances complexity, latency, and overfitting trade-offs to optimize robustness in adversarial environments. As shown in Table 8, the DAEEC achieves superior attack robustness (tolerating 100% FSU attacks) at the cost of moderate complexity ( \(\mathbf {O(m)} + \mathbf {O(30 \cdot d \cdot m)}\)) FLOPs) and latency (3.2 ms), which is 40% faster than DRL methods (5.8 ms) and only 6.4\(\times\) slower than non-ML schemes such as IGS (0.5 ms) - a justified trade-off given its zero failure rate under extreme attacks. To mitigate overfitting, we employ L2 regularization (\(\lambda = 0.01\)) and sparsity constraints (\(\rho = 0.1\)) in the DAE, coupled with AdaBoost’s diversity (30 shallow DTs), limiting the accuracy drops to 2.1% under label noise (vs. 8.3% for single DTs). Although the computational overhead exceeds traditional methods, our ablation studies confirm the 2-neuron bottleneck and the parallelizable trees of DAE ensure deployability in resource-constrained CRNs, with pathways for further optimization (e.g., quantization).

Conclusion

While cooperative sensing among SUs in CRNs enhances performance, its effectiveness is severely degraded by faulty or malicious reports from FSUs. This study proposes a data denoising and classification framework to mitigate the impact of abnormal reports from both legitimate users and FSUs. Specifically, a denoising autoencoder is employed to filter channel noise and FSU reports from the sensing data. The reconstructed data at the FC is then processed by an EC to determine PU activity. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed framework integrating the autoencoder and EC achieves improved sensing performance with reduced sensing error compared to traditional (IGS, HGS) and more recent (CNN, PSO, DE-ML) schemes. The strategic integration of DAE with ensemble classification robustly identifies PU channel states, effectively mitigating sensing errors and improving system operational efficiency beyond both traditional and contemporary techniques.

Limitations and generalizability

While the proposed DAEEC framework demonstrates superior performance in mitigating FSU attacks, several limitations should be acknowledged. Specifically, although our approach advances previous ensemble methods34 (semisoft stacking) and optimization techniques35 (DE-ML) in FSU robustness, its computational complexity (DAE: 1,500 epochs; EC: 30-tree ensemble) exceeds simpler architectures. However, ablation studies confirmed that the 2-neuron DAE hidden layer reduces inference latency by 63% compared to CNNs30, and the 30-tree ensemble achieves diminishing returns beyond 98.5% MCC - validating our design trade-offs for real-time CRN deployment. The current evaluation relies on synthetic data with Gaussian noise and fixed sensing parameters (e.g., 1 ms sensing period, 40 KHz bandwidth). Real-world RF environments may exhibit non-Gaussian noise, dynamic interference, and time-varying channel conditions that require further validation. The DAE’s denoising efficacy is inherently dependent on its training data. While it performs excellently on Gaussian noise, its performance under non-Gaussian noise or fast-fading conditions would require retraining on datasets specifically encompassing those impairments. Although the synthetic dataset emulates key CRN characteristics through physically-derived distributions, testing with real-world spectrum measurements (e.g., from RF sensors or spectrum analyzers) is essential to validate performance under practical impairments like non-Gaussian noise and hardware nonlinearities. The assumption of static SNR per sensing interval may not hold in fast-fading environments. Furthermore, spatial correlation between SUs in dense deployments is not taken into account, which could influence cooperative sensing performance. The DAE’s denoising efficacy for non-Gaussian signals (e.g., orthogonal frequency division multiplexing, radar pulses) remains to be verified. The DAE’s 1500-epoch training and the ensemble classifier’s 30 decision trees may pose challenges for real-time implementation on resource-constrained devices. To substantiate this, we clarify that the 1500-epoch training is a one-time, offline cost. Our empirical measurements show the inference process is efficient, with a latency of 3.2 ms on a standard Intel i7 CPU. This latency is primarily due to the 30 decision trees in the EC. For resource-constrained devices, this overhead can be drastically reduced by implementing model quantization, pruning the ensemble to a smaller number of high-weight trees, or deploying the optimized model on dedicated hardware (e.g., low-power FPGAs or ARM NPUs), which is a clear direction for immediate future work.

Future directions

Despite outperforming baseline methods (PSO, DE-ML, and CNN), the proposed DAEEC scheme has several limitations that must be addressed. First, the comparative scope could be extended to hybrid architectures (e.g. CNN-LSTM) to validate robustness in more complex sensing scenarios. Second, our analysis assumes sufficient sensing samples to ensure Gaussian-distributed energy reports (Equation 3), leaving the efficacy of the framework under sample-limited conditions, which is common in low-power applications. Third, the current single-PU focus necessitates future architectural modifications (e.g. parallel DAE branches) for multi-PU environments. Fourth, while current results show consistent performance advantages, formal statistical validation would provide stronger evidence of the ensemble’s superiority across diverse CR network conditions. Finally, though synthetic data enable controlled evaluation, real-world validation using spectrum datasets is needed to assess performance under practical impairments like non-Gaussian noise and hardware nonlinearities. These directions will guide our subsequent research to enhance the framework’s practicality.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript.

References

Haykin, S. Cognitive radio: Brain-empowered wireless communications. Alexandria J. Eng. 23(2), 201–220 (2005).

Giupponi, L., Galindo-Serrano, A., Blasco, P. & Dohler, M. Docitive networks: an emerging paradigm for dynamic spectrum management. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 17(4), 47–54 (2010).

Cabric, D., Mishra, S. M. & Brodersen, R. W. Implementation issues in spectrum sensing for cognitive radios. Signals, Systems and Computers, Conference Record of the Thirty-Eighth Asilomar Conference On 1, 772–776 (2004).

Liu, X., Zheng, K., Chi, K. & Zhu, Y.-H. Cooperative spectrum sensing optimization in energy-harvesting cognitive radio networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 19(11), 7663–7676. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2020.3015260 (2020).

Zhang, Y. & Luo, Z. A review of research on spectrum sensing based on deep learning. Electronics 12(21), 1–42 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Impacts of sensing energy and data availability on throughput of energy harvesting cognitive radio networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 72(1), 747–759. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2022.3204310 (2023).

Mach, J. B., Ronoh, K. K. & Langat, K. Improved spectrum allocation scheme for tv white space networks using a hybrid of firefly, genetic, and ant colony optimization algorithms. Heliyon 9(3), 13752 (2023).

Zheng, K., Liu, X., Zhu, Y., Chi, K. & Liu, K. Total throughput maximization of cooperative cognitive radio networks with energy harvesting. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 19(1), 533–546. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2019.2946813 (2020).

Koteeshwari, R. S. & Malarkodi, B. Compressive spectrum sensing for 5g cognitive radio networks - lasso approach. Heliyon 8(6), 09621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09621 (2022).

Khan, M. S., Gul, N., Kim, J., Qureshi, I. M. & Kim, S. M. A genetic algorithm-based soft decision fusion scheme in cognitive iot networks with malicious users. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing 2020, 2509081 (2020).

Sharifi, A. A., Sharifi, M. & MuseviNiya, M. J. Collaborative spectrum sensing under primary user emulation attack in cognitive radio networks. IETE J. Res. 62(2), 205–211 (2016).

Cao, X. & Lai, L. Distributed gradient descent algorithm robust to an arbitrary number of byzantine attackers. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 67(22), 5850–5864 (2019).

Sun, Z. et al. Defending against massive ssdf attacks from a novel perspective of honest secondary users. IEEE Commun. Lett. 23(10), 1696–1699 (2019).

Du, H., Fu, S. & Chu, H. A credibility-based defense ssdf attacks scheme for the expulsion of malicious users in cognitive radio. Int. J. Hybrid Inf. Technol. 8(9), 269–280 (2015).

Feng, J., Zhang, M., Xiao, Y. & Yue, H. Securing cooperative spectrum sensing against collusive ssdf attack using xor distance analysis in cognitive radio networks. Sensors (Switzerland) 18(2), 1–14 (2018).

Feng, J., Li, S., Lv, S., Wang, H. & Fu, A. Securing cooperative spectrum sensing against collusive false feedback attack in cognitive radio networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 67(9), 8276–8287 (2022).

Muzaffar, M. U. & Sharqi, R. A review of spectrum sensing in modern cognitive radio networks. Telecommun. Syst. 85(2), 347–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11235-023-01079-1 (2024).

Vijay, E. V. & Aparna, K. Deep learning-ct based spectrum sensing for cognitive radio for proficient data transmission in wireless sensor networks. E-Prime - Advances in Electrical Engineering and Electronic Energy 9, 100659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prime.2024.100659 (2024).

Somula, L.R. & Meena, M. K-nearest neighbour (knn) algorithm based cooperative spectrum sensing in cognitive radio networks. In: IEEE Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Cybernetics, Cognition and Machine Learning Applications, ICCCMLA 2022, 122–127 (2022)

Muñoz, E. C., Pedraza, L. F. & Hernández, C. A. Machine learning techniques based on primary user emulation detection in mobile cognitive radio networks. Sensors 22(13), 1–20 (2022).

Kumar, A. et al. Analysis of spectrum sensing using deep learning algorithms: Cnns and rnns. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15(3), 102505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2023.102505 (2024).

Xie, J., Fang, J., Liu, C. & Li, X. Deep learning-based spectrum sensing in cognitive radio: A cnn-lstm approach. IEEE Commun. Lett. 24(10), 2196–2200 (2020).

Tang, Z. L. & Li, S. Deep recurrent neural network for multiple time slot frequency spectrum predictions of cognitive radio. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 11(6), 3029–3045 (2017).

Jiang, W., Yu, W., Wang, W. & Huang, T. Multi-agent reinforcement learning for joint cooperative spectrum sensing and channel access in cognitive uav networks. Sensors 22(4), 1–20 (2022).

Ning, W., Huang, X., Yang, K., Wu, F. & Leng, S. Reinforcement learning enabled cooperative spectrum sensing in cognitive radio networks. J. Commun. Netw. 22(1), 12–22 (2020).

Zheng, K., Jia, X., Chi, K. & Liu, X. Ddpg-based joint time and energy management in ambient backscatter-assisted hybrid underlay crns. IEEE Trans. Commun. 71(1), 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2022.3221422 (2023).

Liu, X., Li, X., Zheng, K. & Liu, J. Aoi minimization of ambient backscatter-assisted eh-crn with cooperative spectrum sensing. Computer Networks 245, 110389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110389 (2024).

Gul, N., Kim, S. M., Ali, J. & Kim, J. Uav aided virtual cooperative spectrum sensing for cognitive radio networks. PLOS ONE 18(9), e0291077, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291077 (2023).

Singh, A. K. & Ranjan, R. Multi-layer perceptron based spectrum prediction in cognitive radio network. Wireless Pers. Commun. 123, 3539–3553 (2022).

Chen, Z., Guo, D. & Zhang, J. Deep learning for cooperative spectrum sensing in cognitive radio. In: International Conference on Communication Technology Proceedings, ICCT, 741–745 (2022).

Khader, A. A. H., Reja, A. H., Hussein, A. A. & Beg, M. T. Mainuddin: Cooperative spectrum sensing improvement based on fuzzy logic system. In: Procedia Computer Science 58, 34–41 (2015).

Lakshmi, A.J. & Singh, J.S. Svm based throughput maximization in cognitive radio. In: IEEE-Proceedings - 2022 6th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems, ICICCS 2022, pp. 729–732 (2022)

Lakshmikantha Reddy, S. & Meena, M. Performance of cooperative spectrum sensing techniques in cognitive radio based on machine learning. In: Cognitive Science and Technology, 255–261 (2023).

Liu, H., Zhu, X. & Fujii, T. Ensemble deep learning based cooperative spectrum sensing with semi-soft stacking fusion center. In: 2019 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), pp. 1–6 (2019)

Gul, N., Kim, S. M., Ahmed, S. & Kim, J. Differential evolution based machine learning scheme for secure cooperative spectrum sensing system. Electronics (Switzerland) 10(14). https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10141687 (2021).

Gul, N., Ahmed, S., Kim, S. M. & Kim, J. Robust spectrum sensing against malicious users using particle swarm optimization. ICT Express 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icte.2021.12.008 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) and the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Korea for their invaluable support and funding that made this research possible.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the IITP-ICAN ((IITP-2025-RS-2022-00156326), 50%) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) and in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2021R1A2C1013150). Dr. Su Min Kim contribution was made during his sabbatical leave from the Tech University of Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Noor Gul, Sadiq Akbar, and Atif Elahi contributed to the conceptualization, methadology and data curation of the study. Su Min Kim, and Junsu Kim formally analyzed project administration and provided resources. Similarly, Noor Gul, Atif Elahi, Sadiq Akbar, Junsu Kim, and Su Min Kim contributed to the manuscript’s original draft and review process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gul, N., Kim, S.M., Akbar, S. et al. Enhanced sensing performance through the integration of denoising autoencoder and ensembling techniques. Sci Rep 16, 535 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30059-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30059-5