Abstract

This study aimed to investigate clinical medical students’ perceived knowledge, attitudes, and academic performance in pharmacology blended learning. This cross-sectional study surveyed Fujian Medical University clinical students in January 2024. It assessed perceived knowledge, attitude (questionnaire), self-efficacy (GSE-6), and procrastination (PASS). A total of 502 valid questionnaires were included in the analysis. Among them, 266 (52.99%) were male, with a mean age of 20.96 ± 0.63 years. The mean scores for perceived knowledge, attitude, and final grades were 16.25 ± 3.85 (possible range: 0–20), 31.11 ± 3.27 (possible range: 9–45), and 78.85 ± 9.20 (possible range: 0–100), respectively. The structural equation model demonstrated that perceived effectiveness of teaching methods had direct influences on both perceived knowledge (β = 0.389, p < 0.001) and attitude (β = 0.308, p < 0.001). Attitude was directly affected by both perceived knowledge (β = 0.163, p < 0.001) and GSE-6 (β = 0.109, p = 0.022). Additionally, attitude (β = − 0.365, p = 0.001) and GSE-6 (β = − 0.500, p < 0.001) directly affected PASS, while attitude directly affected final grades (β = 0.426, p = 0.001). Clinical students showed adequate pharmacology perceived knowledge but suboptimal attitudes toward blended learning, suggesting improved perceived effectiveness of teaching methods could enhance education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past decades, numerous innovative teaching and learning methods have been developed and promoted to optimize the benefits of modern medical curricula. Among these, several approaches have been particularly effective in addressing the challenges of pharmacology education within integrated medical programs, including team-based learning, problem-based learning, personalized learning, and the use of integrative technologies1. Blended learning represents a dynamic hybrid approach to education, seamlessly merging the advantages of online and traditional perceived effectiveness of teaching methods2. It combines online and offline courses, integrates mixed teaching techniques, and embraces the flipped classroom concept, all facilitated by Internet technology for comprehensive student progress monitoring3. Encouraged by the state, educators are motivated to leverage information technology to enhance their teaching prowess, explore innovative pedagogical models, and embrace diverse strategies like blended learning, thereby forging a novel online teaching paradigm that harmoniously merges online and offline elements4. Numerous studies have confirmed the advantages of blended learning in medical education. For example, a meta-analysis demonstrated that blended learning consistently yielded better perceived knowledge acquisition outcomes than traditional health education methods5. Furthermore, blended learning and associated educational activities have been shown to enhance students’ learning motivation and interest6.

Pharmacology is an essential and compulsory component of clinical medicine and pharmacy majors that is pivotal in equipping students with vital perceived knowledge about drugs7,8. Within the medical college curriculum, this discipline focuses on elucidating the pharmacological properties of the drugs, thus providing a foundation for their appropriate use in future clinical practice9. However, pharmacology remains a challenging subject for medical students, requiring students to grasp the fundamental principles of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics and gain relevant perceived knowledge specific to various drugs within a restricted timeframe10. Consequently, many students experience heightened stress and challenges in assimilating the extensive pharmacological perceived knowledge expected of them11,12.

The perceived knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) survey is a valuable research tool employed to assess a particular group’s comprehension, beliefs, and behaviors on a specific topic, functioning as a diagnostic instrument to reveal the extent of perceived knowledge, prevailing attitudes, and their real-world manifestations. Within the context of health literacy, the KAP model is grounded in the premise that perceived knowledge significantly influences attitudes, which in turn shape behavioral choices and actions13,14,15. In the field of medical education, the achievement of learning outcomes among medical students has paramount importance for both students and educators16. At present, while several studies have investigated students’ cognition and self-efficacy in blended learning for medical nutrition17 and the effectiveness of Moodle-based blended teaching in medical statistics18, there remains a perceived knowledge gap concerning how clinical medical students engage with blended learning specifically in pharmacology—a subject known for its complexity and high cognitive demand. This presents an opportunity for targeted interventions tailored to this challenging discipline.

This study aimed to investigate the perceived knowledge, attitudes, and academic performance of pharmacology blended learning among clinical medical students.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted at Fujian Medical University between January 16, 2024, and February 16, 2024. Informed consent was obtained from all participating students. The Biomedical Research Ethics Review Committee of Fujian Medical University approved this study. The study involved third-year clinical medicine students enrolled in a blended teaching program. In addition, the curriculum design incorporates blended learning principles, utilizing a combination of online and offline teaching approaches as informed by related literature.

Blended teaching program design

The pharmacology course was conducted over one academic semester using a blended teaching approach that combined in-person lectures with online learning modules. For the 5-year clinical medicine students, the course was delivered during the fall semester of 2022, and final grades were finalized in January 2023. For the “5 + 3” integrated program students, the course was conducted in the spring semester of 2023, and final grades were finalized in July 2023. The survey was administered after obtaining ethical approval in January 2024, approximately 1 year and 6 months after course completion for the two groups, respectively. The blended teaching program was implemented in three stages: pre-class, in-class, and post-class. Pre-class, students accessed online materials via the MOOC platform, completed preparatory assignments and quizzes, joined discussions, and reviewed relevant literature to support self-directed learning. In-class sessions combined review and new content: students’ preparation was checked through on-site quizzes, key concepts were reinforced via flipped classroom activities (interactive Q&A, student presentations), and instructors addressed knowledge gaps. Group-based clinical case discussions further developed application skills and teamwork. Post-class, students revisited core concepts, explored extended content (including recent pharmacological research), shared study strategies, and engaged in online teacher-student and peer interactions to consolidate learning. The pharmacology course comprised 64 teaching hours (40 min each), including 50 h of in-person lectures and 14 h of online chapter videos. The online resources included 52 videos from the national excellent online open courses of Soochow University and 36 videos recorded by our school’s teaching staff, covering the full content of the Pharmacology textbook (People’s Medical Publishing House). These materials were hosted on the iCourse China University MOOC platform (www.icourse163.org). The chapter videos served mainly as supplementary content and were integrated into in-person lectures to ensure systematic and coherent delivery. All participants received this blended teaching program, including both in-person lectures and the designated chapter videos.

Questionnaire

The self-administered questionnaire was developed based on the Ninth Edition of Pharmacology19 and previous studies5,20,21,22. For instance, the perceived knowledge component was based on the 9th edition of Pharmacology, focusing primarily on fundamental concepts of pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics related to commonly used clinical drugs. As this section used self-assessment items (Very knowledgeable/Heard about/Unclear), it reflects students’ perceived knowledge rather than objectively tested knowledge. The attitude dimension of our questionnaire was independently designed to explore relevant attitudes and thoughts. Furthermore, we have included pertinent scales in the overall survey to enhance the assessment.

The final questionnaire was divided into several distinct sections (Supplement material): the demographic information section, which collected data such as student ID, age, gender, class type, residential status, and living expenses, etc.; the perceived knowledge dimension, which consisted of 10 questions, each scored on a three-point scale, where 2 points indicated “Very knowledgeable”, 1 point indicated “Heard about”, and 0 points reflected “Unclear”. Attitude dimension, which included 9 questions, evaluated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (5 points) to strongly disagree (1 point). Attaining scores of > 70% of the maximum in each section indicated adequate perceived knowledge and a positive attitude. As there is currently no unified cut-off standard for KAP scoring in this context, the 70% threshold was adopted based on its common use in previous KAP studies23,24.

Perceived effectiveness of pharmacology perceived effectiveness of teaching methods, which included four questions, also rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 to 5), with the total score ranging from 4 to 20. The general self-efficacy scale (GSE-6), which was used to assess self-efficacy, scores ranging from 6 to 24. The scale is a six-item abbreviated version of the General Self-Efficacy Scale25, which has demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties across various cultures and in both non-clinical and clinical samples, as well as good concurrent and predictive validity26; The Chinese version of the GSE-6 used in this study was adapted from previously validated Chinese translations, with minor wording adjustments for cultural and contextual relevance to medical students. procrastination assessment scale-students (PASS)27, determined by summing scores from the first two items related to six academic tasks. The total score ranged from 12 to 60 points and was treated as a continuous variable in this study, where higher scores indicated a greater tendency toward academic procrastination (problematic behavior), while lower scores reflected more proactive academic behaviors. Students’ final grades were also recorded using their unique student ID number.

Questionnaire reliability and quality control

A preliminary pilot study was conducted with a limited sample of 63 participants to test the reliability of the questionnaire, revealing strong internal consistency with an overall Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.818. In addition, the internal consistency of each subscale was examined using Cronbach’s α. The results showed good reliability for the perceived knowledge section (Cronbach’s α = 0.913) and the perceived effectiveness of pharmacology teaching methods section (Cronbach’s α = 0.834), while the attitude section showed acceptable but relatively lower reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.634). Item—total correlation analysis further confirmed that most items within each subscale contributed positively to the overall scale score. These results suggest that the questionnaire had acceptable internal consistency for use in this study. For data collection, an online questionnaire was developed using the “Wenjuanxing” within WeChat, accompanied by the generation of a QR code for easy access and completion by participants via WeChat. In order to uphold data quality and completeness, all questionnaire items were designated as mandatory. Rigorous quality control measures were implemented by the research team, involving reviews of questionnaire completeness, internal consistency, and overall reasonability to ensure the reliability of survey results.

Sample size

The sample size was determined using the formula for estimating a single population proportion: n = [(Zα/2)2 × P(1 − P)]/d2. Due to the lack of prior KAP research on blended learning among Chinese medical students, we assumed a baseline awareness rate of 50% for PND. With a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error, the calculated minimum sample size was 384 participants. The theoretical sample size was 480 which includes an extra 20% to allow for invalid cases.

Statistical analysis

Stata 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Continuous variables were described using mean ± standard deviation (SD), and between-group comparisons were performed using t-tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA). Categorical variables were presented as n (%). Pearson correlation analysis was employed to assess the correlations between perceived knowledge, attitudes, perceived effectiveness of teaching methods, GSE-6, PASS, and final grades (overall score). Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to validate the following set of hypotheses: (1) perceived effectiveness of teaching methods exert a direct impact on both perceived knowledge and attitudes; (2) perceived knowledge directly influences attitudes and final grades; (3) Attitudes have a direct influence on PASS; (4) GSE-6 directly affects attitudes and PASS; (5) PASS directly affects final grades. Two-sided p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Model fit was evaluated using Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI).

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 685 third-year, first-semester students from seven 5-year clinical medicine classes and 184 third-year, second-semester students from three 8-year clinical medicine classes were invited to participate. Of these, 467 and 173 questionnaires were returned, respectively, yielding 640 collected responses. Participation was voluntary, and all students provided informed consent before completing the survey. Among the 640 collected questionnaires, 138 were excluded based on the following criteria: 24 students declined to participate; 22 had missing values; 6 had anomalous school numbers or class information; 20 had duplicate school numbers; 62 had unmatchable or zero final grades; 3 were identified as outliers due to abnormal ages (24, 26, and 34 years old, while all other participants were under 23); and 1 consistently selected option C for all KAP items. After these exclusions, 502 valid questionnaires were included in the final analysis. Among these, 266 (52.99%) were male, 355 (70.72%) were enrolled in a 5-year graduate program, with a mean age of 20.96 ± 0.63 years. Among these, 333 (66.33%) were not class cadres. Regarding their self-reported learning preferences, 255 (50.8%) preferred a combination of online and offline learning, 208 (41.4%) preferred purely offline learning, and 39 (7.8%) preferred purely online learning. These preferences reflected students’ general study habits and were not equivalent to the blended teaching model (in-person plus chapter videos) implemented in this pharmacology course. Moreover, 451 (89.84%) had plans to pursue postgraduate education (Table 1). Grade distributions by learning mode are also presented in Table S1, showing no significant difference among students preferring different learning modes (p = 0.597).

Descriptive statistics of main variables

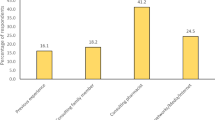

The mean perceived knowledge score was 16.25 ± 3.85 (possible range: 0–20), the mean attitude score was 31.11 ± 3.27 (possible range: 9–45), the mean perceived effectiveness of teaching methods score was 15.47 ± 3.12 (possible range: 4–20), the mean GSE-6 score was 15.97 ± 2.78 (possible range: 6–24), the mean PASS score was 31.07 ± 8.38 (possible range: 12–60). Gender-stratified analysis showed that female students scored significantly higher than male students in final academic final grades (80.17 ± 8.56 vs. 77.69 ± 9.60, p = 0.002). Minor gender differences were also observed in several knowledge and attitude items, as well as academic grade (Table S2). Participants generally perceived themselves as having a strong understanding of pharmacology; over 69% rated themselves as “Very knowledgeable” on key topics such as pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics. However, familiarity with new drug development and recent pharmacological advances was lower, with 42.43% indicating only basic awareness (Table S3). Regarding attitudes, 87.32% agreed that pharmacology is crucial for their future clinical practice, and 92.63% favored integrated teaching approaches that link theory with practical application. Although 67.93% expressed concerns about the effectiveness of online learning, 82.14% appreciated the blended learning model for its flexibility and support of independent study, while 78.45% preferred traditional face-to-face teaching for its interactive benefits (Table S3). Perceived effectiveness of teaching methods and the specific option distribution for GSE-6 and PASS are also detailed in Table S3.

Correlation analysis

The Pearson correlation analysis revealed that perceived knowledge had a positive correlation with attitude (r = 0.331, p < 0.001), perceived effectiveness of teaching methods (r = 0.32, p < 0.001), and GSE-6 (r = 0.1218, p = 0.0063). Conversely, it was negatively correlated with PASS (r = − 0.1052, p = 0.0184). The attitude was positively correlated with perceived effectiveness of teaching methods (r = 0.3747, p < 0.001), GSE-6 (r = 0.1236, p = 0.0056), and final grades (r = 0.1347, p = 0.0025), while negatively correlated with PASS (r = − 0.1501, p = 0.0007). Similarly, perceived effectiveness of teaching methods were positively correlated with GSE-6 (r = 0.124, p = 0.0054) and negatively correlated with PASS (r = − 0.1458, p = 0.0011). Lastly, GSE-6 had a negative correlation with PASS (r = − 0.1935, p < 0.001) (Table S4).

Structural equation modeling results

The SEM demonstrated highly favorable model fit indices, with RMSEA = 0.055, SRMR = 0.030, TLI = 0.888, and CFI = 0.960, indicating a good model fit (Table S5), where perceived effectiveness of teaching methods exerted a direct influence on both perceived knowledge (β = 0.389, p < 0.001) and attitude (β = 0.308, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the attitude was directly affected by both perceived knowledge (β = 0.163, p < 0.001) and GSE-6 (β = 0.109, p = 0.023). Additionally, attitude (β = − 0.365, p = 0.001) and GSE-6 (β = − 0.500, p < 0.001) directly impacted PASS. Finally, the attitude had a direct positive effect on final grades (β = 0.426, p = 0.001) (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Discussion

Our results showed that clinical medical students had adequate perceived knowledge and a suboptimal attitude toward pharmacology blended learning and relatively good academic performance in pharmacology learning. Here, “suboptimal attitude” refers to the relatively lower mean scores observed in the attitude dimension, indicating moderate endorsement of the value and applicability of blended pharmacology learning rather than strong enthusiasm or active engagement. Fostering a positive attitude may be essential as it directly impacts academic performance. Additionally, it may be beneficial to focus on boosting students’ self-efficacy beliefs in their ability to excel in pharmacology.

The present study detected significant variations in key metrics regarding pharmacology blended learning among medical students. There was a gender-related variation in perceived knowledge scores, with females demonstrating slightly better results than males, which is consistent with existing research suggesting that gender differences in academic performance can manifest across various disciplines28,29. This difference may be related to gender differences in cognitive and learning styles, as female students have been reported to show higher levels of academic engagement, self-regulated learning behaviors, and conscientiousness in health professional education contexts. Despite these differences in perceived knowledge acquisition, the similar attitudes and overall final grades between genders suggested that perceived knowledge level does not directly translate to differences in overall academic performance or perceptions towards the subject. Although the gender differences detected in knowledge, attitude items, and academic final grades reached statistical significance, the magnitude of differences was relatively small. Therefore, the practical implications appear limited, and such variations may reflect subtle differences in learning strategies, self-regulation, or academic engagement rather than meaningful disparities in educational outcomes. Besides, students in the longer, 8-year program had higher perceived knowledge scores compared to their peers in the 8-year program, which could be due to the more rigorous academic environment and deeper engagement with the subject matter typically found in extended programs, enhancing understanding and retention. Class cadres, often taking on leadership and organizational roles, scored higher in perceived knowledge assessments. The additional responsibilities and engagement with academic content may enhance their motivation and access to educational resources, supporting better performance. Moreover, our findings revealed a clear trend where students with higher academic rankings consistently showed superior perceived knowledge scores. This phenomenon could be attributed to the higher intrinsic motivation and more effective learning strategies common among top-performing students30. Our results indicated that different learning modes have varying effectiveness on students’ final grades. Although blended learning models are increasingly popular, the mixed results suggest that their success might heavily depend on how well the methods match individual learning styles and the specific implementation of the curriculum31.

In the study on pharmacology blended learning, evident variations were observed in medical students’ perceived knowledge perceptions. Some students demonstrated a strong grasp of fundamental pharmacological concepts, while others expressed uncertainty or confusion about specific aspects of blended learning. These findings underscore the need for tailored educational strategies. Institutions should prioritize reinforcing essential pharmacological perceived knowledge to optimize clinical practice, fostering more profound understanding and relevance. Additionally, addressing concerns related to online learning fatigue, the dynamics of blended teaching, and raising awareness of the benefits of blended learning can enhance the overall educational experience, ultimately better equipping future healthcare professionals32,33.

Concerning attitude, many medical students held strong convictions regarding the importance of pharmacology as a foundational course for their future clinical practice. Moreover, many agreed with the challenges inherent in mastering pharmacology and the additional time and effort it demands. Notably, a substantial majority shared concerns about the practical applicability of pharmacology perceived knowledge and advocated for integrated perceived effectiveness of teaching methods that bridge theory with clinical practice34. Additionally, many acknowledged the benefits of staying updated with the latest research findings and clinical guidelines. A significant percentage of students positively accepted blended online and offline teaching. Furthermore, the belief in the enhanced convenience, flexibility, and opportunities offered by blended teaching is widespread. However, students indicate a lack of acceptance for fully online teaching while demonstrating a positive appreciation for blended online and offline teaching models, with a willingness to engage in the in-person components of this blended approach. These findings highlight the multifaceted nature of students’ attitudes toward pharmacology education and underscore the need for educators to adapt instructional methods to accommodate varying preferences and concerns, ultimately enhancing the effectiveness of clinical practice-oriented education.

Regarding perceived effectiveness of teaching methods, a notable portion of the surveyed medical students found in-person classroom teaching and watching chapter videos highly beneficial. However, their primary endorsement lies within the in-person components of blended learning models. These findings suggest that traditional perceived effectiveness of teaching methods, such as classroom instruction, still appeal significantly to students. Simultaneously, acknowledging the utility of video-based learning materials and assessment tools underscores the importance of diverse instructional resources. Regarding students’ self-efficacy beliefs, a considerable percentage were confident in their ability to overcome obstacles, persist in goal attainment, and handle unforeseen situations adeptly. This valuable trait of self-efficacy can positively influence academic success and future clinical practice. On the contrary, findings related to procrastination revealed areas of concern, with a notable proportion of students admitting to frequent procrastination across various academic tasks, which is consistent with other research35,36. Recognizing procrastination as problematic indicates room for interventions to enhance time management and study habits. The intention expressed by students to reduce procrastination underscores the potential for interventions and support systems to improve academic outcomes and, subsequently, clinical preparedness. These results collectively emphasize the importance of a multifaceted approach to medical education that addresses perceived effectiveness of teaching methods and students’ self-efficacy and time management skills to enhance clinical practice readiness.

SEM further confirmed that perceived effectiveness of teaching methods directly influenced perceived knowledge and attitude. Both perceived knowledge and GSE-6 directly influenced the attitude, and both attitude and self-efficacy directly impacted PASS. Finally, attitude exhibited a direct positive effect on academic final grades, whereas the direct paths from perceived knowledge and PASS to final grades were non-significant, and no multicollinearity was detected among the main variables (all VIF < 5). This pattern may be partially explained by conceptual overlaps among these constructs or by unmeasured factors such as prior academic ability or learning motivation. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted with caution and considered exploratory in nature. Nevertheless, the observed association highlights the potential importance of fostering a positive attitude as part of strategies to support students’ academic success. These findings collectively emphasize the need for educational interventions that promote the perceived effectiveness of teaching methods, foster a positive attitude, and enhance self-efficacy to mitigate procrastination tendencies, ultimately leading to improved clinical practice readiness37. Notably, the non-significant paths from perceived knowledge and PASS to final grades may reflect indirect effects (e.g., via attitude) or be attenuated by the time lag between course completion and the survey. These findings should be interpreted as exploratory. They also have implications for curriculum design: blended pharmacology learning could be optimized by aligning online videos with in-person content, incorporating interactive case discussions and formative assessments to enhance engagement, and providing instructor training to ensure effective integration of online and offline components.

Furthermore, considering that higher PASS scores indicated greater academic procrastination tendencies, which may negatively affect learning outcomes, targeted pedagogical strategies should be implemented to mitigate these effects. Such strategies could include incorporating structured learning schedules and progress monitoring, providing timely feedback and formative assessments, and fostering self-regulated learning skills through mentorship and peer support. These interventions may help reduce students’ procrastination tendencies and enhance their engagement in blended pharmacology learning.

Despite the concurrent preference for traditional methods, the positive attitude toward blended learning raises intriguing questions. Understanding the specific aspects of blended learning that resonate with students and how these preferences might evolve could be the focus of future research38. In addition, the relatively weak correlation between perceived knowledge and self-efficacy is an avenue for deeper investigation. Research into the nuanced interplay between these variables in medical education may unveil insights that could be used to guide curriculum development and student support strategies.

This study has several limitations. It has a cross-sectional design, providing only a snapshot of the relationships and outcomes at a specific time. This design does not allow for the assessment of causality or changes over time. Additionally, the study relies on self-administered questionnaires, which are subject to response bias and may not accurately reflect the students’ actual perceived knowledge, attitudes, or behaviors. Furthermore, the study was conducted among third-year clinical medical students from a single university, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to medical students in other years or from different institutions. Future studies involving more diverse samples across multiple universities and academic years are needed to enhance the external validity of the results. In addition, there was a time lag between the completion of the pharmacology courses and the administration of the survey. This lag may have affected students’ recollection and engagement, and should be considered a potential source of bias. Moreover, the analysis did not control for potential confounding variables (e.g., gender, program length, cadre status, academic rank, and residence) or account for possible class/instructor clustering effects, which may have influenced the observed associations. Finally, the preference-based comparison may not fully reflect the actual impact of different teaching modes on academic performance, as all participants received blended teaching. Further studies with distinct teaching modes and larger, multicenter samples are needed to confirm these findings. In addition, although several quality control measures were applied, the possibility of acquiescence bias due to self-reported responses cannot be fully excluded.

Clinical medical students had adequate perceived knowledge and a suboptimal attitude toward pharmacology blended learning and relatively good academic performance in pharmacology learning. Perceived effectiveness of teaching methods should be improved through interactive online modules and case-based learning to enhance pharmacology education for medical students.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Fasinu, P. S. & Wilborn, T. W. Pharmacology education in the medical curriculum: Challenges and opportunities for improvement. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 12, e1178 (2024).

Yang, Z. Research on college English classroom teaching model based on adaptive genetic algorithm. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 9527070 (2022).

Xu, D. Exploration on the application path of college English MOOCS teaching under the background of internet of things. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 4572432 (2022).

Ding, J., Ji, X., Zhu, K. & Zhu, H. Application effect evaluation of hybrid biochemistry teaching model based on WeChat platform under the trend of COVID-19. Medicine (Baltimore). 102, e33136 (2023).

Vallée, A., Blacher, J., Cariou, A. & Sorbets, E. Blended learning compared to traditional learning in medical education: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e16504 (2020).

Jafri, L., Majid, H., Siddiqui, H. S., Islam, N. & Khurshid, F. Blended learning mediated fostering of students’ engagement in an undergraduate medical education module. MedEdPublish (2016) 8, 127 (2019).

Wu, Y. Y. et al. Application and evaluation of the flipped classroom based on micro-video class in pharmacology teaching. Front. Public Health. 10, 838900 (2022).

Juhi, A., Pinjar, M. J., Marndi, G., Hungund, B. R. & Mondal, H. Evaluation of blended learning method versus traditional learning method of clinical examination skills in physiology among undergraduate medical students in an Indian Medical College. Cureus. 15, e37886 (2023).

Arcoraci, V. et al. Medical simulation in pharmacology learning and retention: A comparison study with traditional teaching in undergraduate medical students. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 7, e00449 (2019).

McHugh, D., Yanik, A. J. & Mancini, M. R. An innovative pharmacology curriculum for medical students: promoting higher order cognition, learner-centered coaching, and constructive feedback through a social pedagogy framework. BMC Med. Educ. 21, 90 (2021).

Bieri, J. et al. Implementation of a student-teacher-based blended curriculum for the training of medical students for nasopharyngeal swab and intramuscular injection: Mixed methods pre-post and satisfaction surveys. JMIR Med. Educ. 9, e38870 (2023).

Taramarcaz, V. et al. a short intervention and an interactive e-learning module to motivate medical and dental students to enlist as first responders: Implementation study. J. Med. Internet Res. 24, e38508 (2022).

Khalid, A. et al. Promoting health literacy about cancer screening among Muslim immigrants in Canada: Perspectives of Imams on the role they can play in community. J. Prim. Care Community Health. 13, 21501319211063052 (2022).

Koni, A. et al. A cross-sectional evaluation of knowledge, attitudes, practices, and perceived challenges among Palestinian pharmacists regarding COVID-19. SAGE Open Med. 10, 20503121211069280 (2022).

Shubayr, M. A., Kruger, E. & Tennant, M. Oral health providers’ views of oral health promotion in Jazan, Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 23, 214 (2023).

Liang, J. C., Chen, Y. Y., Hsu, H. Y., Chu, T. S. & Tsai, C. C. The relationships between the medical learners’ motivations and strategies to learning medicine and learning outcomes. Med. Educ. Online. 23, 1497373 (2018).

Regmi, A., Mao, X., Qi, Q., Tang, W. & Yang, K. Students’ perception and self-efficacy in blended learning of medical nutrition course: A mixed-method research. BMC Med. Educ. 24, 1411 (2024).

Luo, L. et al. Blended learning with Moodle in medical statistics: An assessment of knowledge, attitudes and practices relating to e-learning. BMC Med. Educ. 17, 170 (2017).

Baofeng, Y. & Jianguo, C. Pharmacology 9th edn. (People’s Medical Publishing House, 2018).

Baessler, F. et al. Delirium: Medical students’ knowledge and effectiveness of different teaching methods. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 27, 737–744 (2019).

Flaherty, G., Fitzgibbon, J. & Cantillon, P. Attitudes of medical students toward the practice and teaching of integrative medicine. J. Integr. Med. 13, 412–415 (2015).

Zhao, Y. M., Liu, S. S. & Wang, J. Application of data-driven blended online-offline teaching in medicinal chemistry for pharmacy students: A randomized comparison. BMC Med. Educ. 24, 738 (2024).

Che, R. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of cervical spondylosis in the general public. Sci. Rep. 15, 32870 (2025).

Shi, Z. & Chen, Y. B. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward chronic pain in older adults among health sciences students: A cross-sectional study. J. Pain Res. 18, 4611–4622 (2025).

Scholz, U., Doña, B. G., Sud, S. & Schwarzer, R. Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 18, 242 (2002).

Romppel, M. et al. A short form of the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE-6): Development, psychometric properties and validity in an intercultural non-clinical sample and a sample of patients at risk for heart failure. Psychosoc. Med. 10, Doc01 (2013).

Solomon, L. J. & Rothblum, E. D. Academic procrastination: frequency and cognitive-behavioral correlates. J. Couns. Psychol. 31, 503 (1984).

Gorth, D. J., Magee, R. G., Rosenberg, S. E. & Mingioni, N. Gender disparity in evaluation of internal medicine clerkship performance. JAMA Netw. Open. 4, e2115661 (2021).

Joji, R. M. et al. Perception of online and face to face microbiology laboratory sessions among medical students and faculty at Arabian Gulf University: A mixed method study. BMC Med. Educ. 22, 411 (2022).

Lee, J. H. Structural relationships between cognitive achievement and learning-related factors among South Korean adolescents. J. Intell. 10, 81 (2022).

Al-Roomy, M. A. The relationship among students’ learning styles, health sciences colleges, and grade point average (GPA). Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 14, 203–213 (2023).

Bransen, D., Govaerts, M. J. B., Panadero, E., Sluijsmans, D. M. A. & Driessen, E. W. Putting self-regulated learning in context: Integrating self-, co-, and socially shared regulation of learning. Med. Educ. 56, 29–36 (2022).

Jepkosgei, J., Nzinga, J., Adam, M. B. & English, M. Exploring healthcare workers’ perceptions on the use of morbidity and mortality audits as an avenue for learning and care improvement in Kenyan hospitals’ newborn units. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22, 172 (2022).

Carpenter, G., Harbin, H. T., Smith, R. L., Hornberger, J. & Nash, D. B. A promising new strategy to improve treatment outcomes for patients with depression. Popul. Health Manag. 22, 223–228 (2019).

Patria, B. & Laili, L. Writing group program reduces academic procrastination: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Psychol. 9, 157 (2021).

Zhou, Y. & Wang, J. Internet-based self-help intervention for procrastination: Randomized control group trial protocol. Trials 24, 82 (2023).

Chen, X. & Cheng, L. Emotional intelligence and creative self-efficacy among gifted children: Mediating effect of self-esteem and moderating effect of gender. J. Intell. 11, 17 (2023).

İlçin, N., Tomruk, M., Yeşilyaprak, S. S., Karadibak, D. & Savcı, S. The relationship between learning styles and academic performance in TURKISH physiotherapy students. BMC Med. Educ. 18, 291 (2018).

Funding

This study was supported by the Fujian University Education and Teaching Research Project (No. FBJY20230219).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SY C and C C carried out the studies, collected data, and drafted the manuscript. LX W and J Y performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. JM X and NW Z participated in data acquisition, analysis, or interpretation and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The Biomedical Research Ethics Review Committee of Fujian Medical University approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from all participating students. The study was carried out in accordance with the applicable guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, S., Chen, C., Wu, L. et al. Perceived knowledge and attitude towards blended learning in pharmacology among medical students. Sci Rep 16, 496 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30060-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30060-y