Abstract

Transport of pollutants is a serious environmental concern, where accurate and effective mathematical models are essential for developing viable mitigation programs. In this work, this study proposes new formulation of advection dispersion equations of fractional order and employ them to model the highly complex advection dispersion phenomena. The derivative using the Modified Atangana–Baleanu–Caputo (MABC) fractional derivative is an advanced extension of the classical Atangana Baleanu derivative and provides greater flexibility in describing memory and nonlocal effects. To solve the resulting problem numerically, we utilize the framework of physics informed neural networks (PINNs), in which the governing physical laws serve as the building blocks of a deep learning model. This approach enables the derivation of highly accurate and fast convergent semi-analytical solutions. The main contributions of this work are threefold: (1) the development of specific PINNs algorithm to solve fractional differential equations in the MABC sense; (2) an extensive performance analysis demonstrating higher precision and computational efficiency compared to conventional numerical and perturbative methods; and (3) validation through a variety of case studies, confirming the robustness and applicability of the proposed approach in different contexts. Several numerical examples are provided to illustrate the effectiveness of the approach, and the results are compared with existing methods to justify both the efficiency and feasibility of the proposed scheme.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fractional calculus (FC) is a subdivision of mathematical analysis which extends the conventional definition of several integer order derivatives and integrals to arbitrary real or complex orders. Even though the conceptual underpinning of fractional calculus was developed almost at the same time as classical (integer-order) calculus. Historically, the development of fractional calculus was stunted by the lack of obvious physical and geometrical interpretations. As a result, it continued to be a relatively impractical curiosity throughout many decades. Over the past couple of decades, nevertheless, the nonlocal property of the fractional order derivatives, which is the ability to add memory and hereditable characteristics, seems to be especially suitable when representing a wide range of real-life events. Fractional differential equations have been placed more accurate and versatile modeling framework than their integer order equivalents due to their intrinsic nonlocal behavior that have been shown to make the fractional differential equations applicable across a range of different fields including medicine, engineering, physics, chemistry, and biology1,2,3,4,5,6.

In recent years, as interest in fractional calculus has grown, there has been an explosion in the number of different definitions of fractional derivatives promulgated in the literature, each seeking to define a different kind of physical and mathematical behavior. The most well-known is the Caputo fractional derivative, introduced by Michele Caputo in 19677 which is useful in practical initial value problems. However, one of the major shortcomings of this operator is that it features a single kernel that has the tendency of being ill-suited to analytical tractability as well as numerical implementation. As a solution to this shortcoming, Caputo and Fabrizio put forward a non-singular fractional derivative inspired by an exponential kernel8. Even though this change removes the problem of singularity, it has restrictions, as the exponential kernel places limit especially to processes that do not necessarily show exponential decay. To overcome this shortcoming, a more generalized one was proposed by Atangana and Blaenau in terms of Mittag Leffler function as the kernel, which gives a non-singular derivative9. In development of this framework, Refai and Blaenau recently added an upgrade, which is referred to modified Atangana Blaenau Caputo (MABC) derivative11. The new operator retains the beneficial properties of its ancestors and presents a better flexibility and descriptive potential to complicated systems, especially those that cannot be effectively described through the initial version of the Atangana Blaenau operators. A generalized results regarding MABC derivative have been investigated in12. The MABC derivative effect is examined numerically through finite difference method to process the advection dispersion equation13, discrete Chebyshev polynomials14, and nonlinear partial differential equations (NPDEs)15,16,17,18,19. The nonlinear partial differential equations are important in different areas of science and engineering such as physics, electronics, information technology, computer science, fiber optics, mechanics, electrical engineering, plasma physics, nonlinear optics, and communication system20,21,22,23,24.

The advection dispersion equation (ADE) is based on the divergence of the transport of the solutes. It has been used extensively to describe the migration of contaminants in porous media. Based on the assumption of Brownian motion, the classical ADE is anchored on the Fick law and is therefore ideal in modeling the Fickian transport processes. Nevertheless, an increasing accumulation of both empirical and theoretical evidence has grown to show that real-world transport of contaminants in porous mediums may not follow this assumption, but is rather non-Fickian or anomalous in nature and cannot be adequately described by conventional ADEs. Fractional advection dispersion equations (FADEs) have been suggested to overcome these deficiencies as an alternative that works effectively. FADEs complement this by embracing fractional derivatives, which allow modeling a more realistic representation of anomalous diffusion and memory effects that naturally exist in complex subsurface systems. Creation of these models is also a mathematically challenging problem, though it is, however, a relatively different problem to the actual solution to the FADEs especially with realistic boundary and initial conditions that is, such requires numerical methods that are specialized. The existence and uniqueness of solutions of some initial value and boundary value problems for the fractional advection dispersion equation have been analyzed by Dimache et al.25.

Extensive research efforts have been conducted on the achievement of FADE solution methods. As an example, Benson et al.26 examined fractional models that could be related to three experimental datasets of contaminant transport and suggested the use of the finite difference method to solve them numerically. In27, the variable transformation, Mellin and Laplace transforms were employed for the same purpose. In the study, Sun et al.28,29 have discussed the use of FADEs in hydrological systems and how useful it can be in modeling anomalous solute transport. Allwright and Atangana30,31,32 solved fractal and fractional versions of the ADE in groundwater transport and brought in such numerical schemes as the finite difference method, the upwind Crank Nicholson and the weighted upwind downwind methods. See also33,34,35,36,37,38 and the references therein. Analytical, numerical, and computational approaches used in the literature for the investigation of different problems39,40,41,42,43.

This analysis aims to process the following FADE in MABC derivative sense:

subject to:

Unlike the classical ABC operator, the MABC derivative employs a Mittag–Leffler kernel that models memory effects with non-exponential decay, improving realism in anomalous transport. For more information regarding recent developments in the theory and applications of the ABC derivative and its modifications, see44,45,46.

The Eq. 1 models the balance between fractional temporal changes represented by w the variable concentration, dispersion \(\beta\), advection \(\alpha\) and external influence g. The model focuses on contaminant transport in groundwater and porous media, where non-Fickian diffusion dominates. While our proposed MABC–PINNs framework focuses on pollutant transport in porous media, similar approaches applied to general fractional diffusion problems have been explored in47,48,49,50.

We make use of the capabilities of a recently developed algorithm, known as Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs)51,52, to approximate functions and solve the proposed model. The neural network architecture incorporates the underlying physical laws directly into its loss function. The properties of the MABC derivatives are employed to construct a customized loss formulation. At selected collocation points, the governing equation is enforced along with the initial and boundary conditions, thereby transforming the problem into an optimization task. The resulting system of nonlinear equations is then solved using numerical solvers, yielding precise and efficient solutions.

Modified fractional operator

As observed in the previous section, the physical and geometrical interpretations of fractional derivatives have not yet reached a consensus, which has led to the development of various definitions in the literature. The definitions of some fundamental concepts that we now bring will have significant role in elaborating the theoretical framework utilized in this research.

Definition 1

9,10 Suppose \(g \in H^1(0,T)\), \(\theta \in (0,1)\) and \(\mathcal {C}(\theta )\) is a normalize function with \(\mathcal {C}(0) = \mathcal {C}(1) = 1\). The ABC derivative is given by

where,

called the Mittag Leffler function.

A new formulation has been proposed by Refai and Blaenau11 and corresponds to the ABC derivative, which is obtained as the result of the integration by parts on Eq. 3 accompanied by the characterization of the Mittag Leffler (ML) function. This extended derivative generalizes the framework of ABC derivative to a larger functional space that making it more applicable to more complex models.

Definition 2

11 Suppose \(g \in L^1(0,T)\), \(\theta \in (0,1)\) and \(\mathcal {C}(\theta )\) called the normalize function with \(\mathcal {C}(0) = \mathcal {C}(1) = 1\). The \(\theta\)-order MABC derivative is defined by

where \(\mu _{\theta } = \frac{\theta }{1-\theta }\), and

is the linear ML mapping presented in53.

Definition 3

11 Suppose \(g^{(n-1)} \in L^1(0,T)\), the MABC derivative of order \(n-1< \gamma < n\) is defined by

where \(\gamma = \theta + n - 1\).

Mathematically, the MABC derivative generalizes the ABC derivative by introducing a flexible kernel parameter \(\mu _{\theta }\), providing improved stability and physical interpret-ability9. The Laplace transform and convolution property were employed to establish the modified power ABC operator with non-singular kernels. The related boundedness was also studied in12. The discrete version of the MABC operator including both the discrete nabla derivative and its counterpart nabla integral have been derived by54. The infinite series representations for the modified derivative has been investigated by Al-Refai et al.55. They also presented the modified derivatives for the Dirac delta functions, provided by numerical illustrations.

The methodology

Here we go ahead to make use of the Physics Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), as used alongside with the related derivative functions, to derive approximate solutions to the fraction advection dispersion equation (FADE) with a MABC derivative.

Modified physics informed neural networks (PINNs)

This algorithm gives the construction and train physics informed neural networks (PINNs) process, in which the special focus is on the data input and the training strategy. The input variables are extracted and next supplied to the input layer through a process of feature extraction before they pass through the network. First, the weights and biases which were usually random and were often logically provided through uniform probability distribution depend on the intensity of connection between the neurons and affect the output of the network. As this input data spreads across the network, every neuron node in the hidden layers carries out weighted summation containing an associated bias term and the output is undergoing an activation function to create some intermediate outputs51,52.

In the current research, our chosen architecture of PINN is the use of two hidden layers, respectively consisting of six and nine neurons. It is the choice of this arrangement because it was tested empirically and proved to be more effective than a simpler one-layer network, as well as more complex three layer designs. The loss function is the mean squared error (MSE) contrasting the network predictions and the target values. The weights are updated via gradient descent, and the optimization process continues to a point where the performance requirements are observed52,53,54.

Fractional operations in fractional differential equations (FDEs) have the nonlocal and memory dependent characteristic which adds the extra complexity in the use of PINNs. In this effort to overcome these difficulties, we generalize the loss to one involving fractional derivatives in a way that the solution fulfills the given initial and boundary conditions. Relying directly on the underlying physical laws, the PINNs provide a strong and efficient alternative to traditional numerical methods, as the latter can be computationally expensive if large amounts of resources are required.

The general framework of the typical PINN is described in a step-by-step manner below:

Formal algorithm

Step 1: Neural network architecture

Input: The input to the neural network is the independent variable \(t\), which could represent time or spatial coordinates.

Network Design: The neural network is constructed with:

-

One or more hidden layers.

-

Nonlinear activation functions (e.g., tanh) applied to the hidden layers.

-

A final output layer that represents the approximation of the unknown function. The tanh activation function provides smooth gradients and bounded nonlinearity, which improves convergence in fractional-order PINNs.

Weights and Biases: The network consists of trainable parameters: weights and biases, which are denoted by \(\theta\).

Output: The output of the neural network is the approximate solution \(u_\theta (t)\), where \(\theta\) represents the parameters of the neural network.

Step 2: Physics Informed Loss Function

The central idea of PINNs is to embed the governing equations directly into the loss function to guide the training of the neural network.

-

i.

Residual of the differential equation: For a given collocation point \(t_i\), calculate the residual of the differential equation:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Residual}(t_i) = \mathcal {L}(w_{\text {NN}}(t_i; \theta )) - g(t_i). \end{aligned}$$This ensures the neural network is learning a solution that satisfies the governing equation.

-

ii.

Boundary/initial condition loss: Enforce the boundary and initial conditions by calculating:

$$\begin{aligned} BC\ Loss = \sum _{i=1}^{N_b} \left| w_{\text {NN}}(t_i; \theta ) - w(t_i) \right| ^2. \end{aligned}$$Where \(t_i\) are the boundary or initial points and \(u(t_i)\) are the known boundary/initial values.

-

iii.

Total loss function: The total loss function is the combination of the residual and the boundary/initial condition.

Step 3: Generate Training Data

-

i.

Collocation points: Sample points \(t_i \in [a, b]\) from the domain to evaluate the residual and compute the loss. These points are typically chosen uniformly or based on adaptive sampling techniques (e.g., random sampling or clustering methods).

-

ii.

Boundary/initial points: Ensure that the boundary or initial points are included in the data set for enforcing the boundary conditions.

Step 4: Optimization Process

-

i.

Optimization algorithm: Use optimization algorithms (e.g., Adam, L-BFGS, or other gradient-based optimizers) to minimize the total loss \(\mathcal {L}(\theta )\).

-

ii.

Training: The training process involves updating the weights and biases \(\theta\) of the neural network iteratively to reduce the loss. The process continues until convergence, or a predefined number of epochs are reached.

-

iii.

Monitoring: Track the residual and boundary errors during the training to ensure that the neural network is effectively learning the solution.

Step 5: Evaluate and Validate the Solution

-

i.

Test the model: After training, evaluate the neural network’s performance on a test set of collocation points and boundary conditions. This provides insight into the generalization ability of the model.

-

ii.

Comparison with Analytical/Numerical Solutions: If available, compare the solution from the trained PINN model with exact analytical solutions or solutions obtained via traditional numerical methods (e.g., finite difference, finite element, or spectral methods).

-

iii.

Error metrics: Compute error metrics such as Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) or Maximum Absolute Error (MAE) to quantify the accuracy of the PINN solution:

$$\begin{aligned} RMSE = \sqrt{ \frac{1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N_k} \left| u_{NN}(t_i; \theta ) - u(t_i) \right| ^2 }. \end{aligned}$$

Step 6: Update Weights and Biases

The weights and bias are adjusted in the following ways at the conclusion for each iteration:

In the context where (new) refers to the current iteration and (old) denotes the previous iteration, \(g_k\) represents the gradient for weights and bias, \(\alpha\) is the parameter chosen to minimize the performance function in the equation above, and the term \(M_k^{-1}\) denotes the inverse Hessian matrix. r represents the weight in the output layer, and c the bias.

Step 7: Check for Convergence

-

i.

Calculate the mean square error (MSE):

$$MSE = \frac{\sum _{i=1}^{n}(y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2}{N}.$$ -

ii.

If the MSE is less than or equal to a predefined threshold \(\varepsilon\), finalize the weights and biases and terminate training. Otherwise, proceed to the next iteration.

Step 8: Iterate

-

i.

Adjust learning rates \(\alpha\) or regularization parameters \(\beta\) dynamically if convergence is slow or oscillatory behavior is observed.

-

ii.

Return to Step 2 and continue training until convergence criteria are met.

Step 8: Iterate

-

i.

Adjust learning rates \(\alpha\) or regularization parameters \(\beta\) dynamically if convergence is slow or oscillatory behavior is observed.

-

ii.

Return to Step 2 and continue training until convergence criteria are met.

Collocation points were uniformly sampled within the problem domain, with denser sampling near the boundaries. Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) was also tested to ensure robustness of the solution.

Applications

In this part, we introduce the (PINN) approach to numerically solve, with MABC derivative, the AD problem in Eqs. 1, 2. Applying the modified PINN algorithm for fractional equations to both sides of Eq. 1, the process unfolds as follows:

Algorithm steps

Step 1: Define the neural network structure

-

i.

Design a neural network \(N(t, \theta )\), where \(\theta\) are the trainable parameters (weights and biases).

-

ii.

Use input t (time domain) and output u(t) as the predicted solution.

Step 2: Physics informed loss components

To enforce the equation and initial conditions:

-

i.

Fractional derivative loss:

$$\begin{aligned} \mathcal {L}_{frac} = \left\| \, {}^{\text {MABC}}_{0}D_{t}^{\theta } w(y,t) - \left[ \beta w_{yy}(y,t) - \alpha w(y,t) + g(y,t) \right] \, \right\| ^2. \end{aligned}$$(8)Compute the MABC derivative numerically using quadrature and finite differences.

-

ii.

Boundary/initial condition loss:

$$\begin{aligned} \mathcal {L}_{bc} = \left\| M(t_0, \theta ) - u(t_0) \right\| ^2. \end{aligned}$$(9)

Step 3: Integral approximation

Discretize the \(\beta w_{yy}(y,t) - \alpha w(y,t) + g(y,t)\) using numerical quadrature (e.g., trapezoidal rule or Gauss Legendre quadrature).

Step 4: Loss function

Combine the loss components:

Where \(\mu _{bc}\) is a weighting factor to balance the contributions of the physics loss and the boundary conditions. To account for the long-tail characteristics of fractional derivatives, an adaptive weighting function \(\omega (y,t)\) was introduced into the loss term, imposing stronger penalties near the boundary layers and improving accuracy in high-gradient regions.

Step 5: Training

-

i.

Generate collocation points \(t_i \in [a,b]\) to train the model.

-

ii.

Use an optimizer (e.g., Adam or L-BFGS) to minimize the loss:

$$\begin{aligned} \theta ^* = \arg \min _{\theta } \mathcal {L}(\theta ). \end{aligned}$$(11) -

iii.

Update \(\theta\) iteratively during training.

Step 6: Prediction

After training, the neural network \(N(t, \theta ^*)\) serves as the approximation of w(t).

Step 7: Validation and error analysis

-

i.

Compute the RMSE to evaluate the accuracy of the solution:

$$\begin{aligned} RMSE = \sqrt{ \frac{1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N} \left| u(t_i) - M(t_i, \theta ) \right| ^2 }. \end{aligned}$$(12) -

ii.

Compare the predicted solution with the exact or numerical solution (if available).

Examples

Of the proposed method, two of the illustrative examples are provided to demonstrate its effectiveness and correctness. In both of them, the findings of the developed and implemented machine learning based approach are contrasted with those published in the current literature.

Example 1

We consider the fractional order ADE with the MABC derivative that was proposed in56:

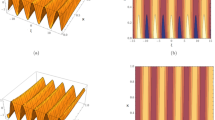

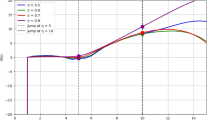

In case \(\theta = 0.6\), the analytic solution for mentioned question is \(w(y,t) = t^2 \sin (\pi y)\). When the analytical solution is applied to replace the solution of the original fractional differential equation, it yields the source term g(x, t). Figure 1 shows the numerical and exact solutions together with the absolute error. It is described in Table 1 with its numerical value and the absolute error. Besides, Table 1 contains a comparison between the findings produced by the suggested approach and those described in56. It can be seen that by both Fig. 1 and Table 1, the proposed approach is a good way to get a good applicable approximation of the exact solution and, thus, very useful and highly reliable.

Table 1 represent to numeric results with the absolute error and also includes a comparison with the results reported in56 and57. It demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Illustration of compare results with \(\theta = 0.6\) for Example 1.

Example 2

Consider the given fractional order ADE with MABC derivative57.

The analytic solution of FADE for \(\theta = 0.5\) is \(w(y,t) = t^4 y^2 (y^3 - 2.5y^2 + 2y - 0.5)\). The exact, numerical solutions and the absolute error is provided in Fig. 2. The presentation of the numerical results is in Table 2 and it further reveals the precision and efficiency of the offered strategy. In addition, Table 2 provides the comparative cross-check between the output achieved with the current method and the works done in57 that proves the efficacy of the present method and its competitive performance.

Compared with spectral and finite element methods, the proposed MABC–PINN framework provides comparable accuracy while significantly reducing computational cost and eliminating the need for dense spatial discretization.

Illustration of compare results with \(\gamma = 0.5\) and \(\kappa = 0.7\) for Example 2.

Conclusions

The fractional order \(\theta\) in the MABC derivative physically represents the strength of memory in pollutant transport; smaller values of \(\theta\) indicate stronger nonlocal effects and slower decay of system memory. In this study, a fractional model was developed to address the advection dispersion problem associated with contaminant transport. The model incorporates the MABC derivative, a recent extension of the Atangana Balaena framework designed to better capture nonlocal and memory dependent behaviors. To obtain numerical solutions to the resulting FADE, we employed an efficient method based on PINNs. Through this approach, the governing differential equation is transformed into a system of algebraic equations, facilitating solution via standard optimization techniques. The key advantages of the proposed methodology include its straightforward implementation and relatively low computational cost. To assess the validity and performance of the approach, several benchmark examples were considered, with results compared against those obtained using existing numerical methods. The numerical findings confirm the accuracy, robustness, and efficiency of the PINN based technique in solving FADEs with MABC derivatives. As a direction for future research, the proposed PINN framework may be extended to the numerical treatment of partial differential–algebraic equations involving MABC derivatives, thereby broadening its applicability to more complex systems. The proposed framework is directly applicable to environmental models, such as groundwater and soil contaminant dispersion. Future extensions will address coupled PDE–algebraic systems and time-dependent boundary conditions.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

References

Noor, A. A., Mohammed, O. H. & Yousif, A. A. A hybrid technique for approximating the solution of fractional order integro-differential equations. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 8, 100552 (2023).

Manisha, M. et al. A novel investigation of the hepatitis B virus using a fractional operator with a non-local kernel. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 8, 100577 (2023).

Az-Zo’bi, E. A., Alomari, M., Afef, Kallekh & Inc, Mustafa. Dynamics of generalized time-fractional viscous-capillarity compressible fluid model. Opt. Quantum Electro. 56(4), 629 (2024).

Shyamsunder, Sanjay, B. & Kamlesh, J. A study of the hepatitis B virus infection using Hilfer fractional derivative. Proc. Inst. Math. Mech. 48, 100–117 (2022).

Sanjay, B. et al. A generalized study of the distribution of buffer over calcium on a fractional dimension. Appl. Math. Sci. Eng. 31(1), 2217323 (2023).

Manisha, M. et al. A novel fractionalized investigation of tuberculosis disease. Appl. Math. Sci. Eng. 32(1), 2351229 (2024).

Caputo, M. Linear models of dissipation whose Q is almost frequency independent-II. Geophys. J. Int. 13(5), 529–539 (1967).

Caputo, M. & Fabrizio, M. Applications of new time and spatial fractional derivatives with exponential kernels. Prog. Fract. Differ. Appl. 2(1), 1–11 (2016).

Atangana, A. & Baleanu, D. Caputo–Fabrizio derivative applied to groundwater flow within confined aquifer. J. Eng. Mech. 143(5), D4016005 (2017).

Eriqat, T., Oqielat, M. N., El-Ajou, A., Ogilat, O. & Momani, S. Approximate Solutions of the Fractional Zakharov-Kuznetsov Equation Using Laplace-Residual Power Series Method. In Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics, 467-484 (2024).

Al-Refai, M. & Baleanu, D. On an extension of the operator with Mittag–Leffler kernel. Fractals 30(05), 2240129 (2022).

Rahman, G., Samraiz, Muhammad, Yildiz, C., Abdeljawad, T. & Alqudah, M. A. New generalized results for modified Atangana–Baleanu fractional derivatives and integral operators. Eur. J. Pure Appl. Math. 18(1), 5697–5697 (2025).

Chawla, R., Deswal, K., Kumar, D. & Baleanu, D. A novel finite difference based numerical approach for Modified Atangana–Baleanu Caputo derivative. AIMS Math. 7(9), 17252–17268 (2022).

Partohaghighi, M., Mortezaee, M., Akgül, A. & Eldin, S. M. Numerical estimation of the fractional advection-dispersion equation under the modified Atangana–Baleanu–Caputo derivative. Results Phys. 49, 106451 (2023).

Sweilam, N., Khater, K. & Asker, Z. Modified Atangana–Baleanu–Caputo derivative for non-linear hyperbolic coupled system. Front. Sci. Res. Technol. 10(1), 53–65 (2025).

Iqbal, M. et al. On the exploration of periodic wave soliton solutions to the nonlinear integrable Akbota equation by using a generalized extended analytical method. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 34708 (2025).

Iqbal, M. et al. Periodic structures of solitons and shock wave solutions in the fractional nonlinear Shynaray-IIA equation via a generalized analytical method. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 38017 (2025).

Alammari, M., Iqbal, M., Ibrahim, S., Alsubaie, N. E. & Seadawy, A. R. Exploration of solitary waves and periodic optical soliton solutions to the nonlinear two dimensional Zakharov–Kuzetsov equation. Opt. Quantum Electron. 56(7), 1240 (2024).

Alshehery, S. et al. Construction of periodic wave soliton solutions for the nonlinear Zakharov–Kuznetsov modified equal width dynamical equation. Opt. Quantum Electron. 56(8), 1381 (2024).

Iqbal, M. et al. Nonlinear behavior of dispersive solitary wave solutions for the propagation of shock waves in the nonlinear coupled system of equations. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 27535 (2025).

Iqbal, M. et al. Applications of nonlinear longitudinal wave equation with periodic optical solitons wave structure in magneto electro elastic circular rod. Opt. Quantum Electron. 56(6), 1031 (2024).

Gong, W., Zhang, Y., Zhu, M., Chen, T. & Zheng, Z. Dynamic control of multiple stratospheric airships in time-varying wind fields for communication coverage missions. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 166, 110514 (2025).

Ren, D. et al. Harmonizing physical and deep learning modeling: A computationally efficient and interpretable approach for property prediction. Scr. Mater. 255, 116350 (2025).

Iqbal, M. et al. Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique. Open Phys. 23(1), 20250198 (2025).

Dimache, A. N., Groza, G., Jianu, M. & Iancu, I. Existence and uniqueness of solution represented as fractional power series for the fractional advection–dispersion equation. Symmetry 16(9), 1137 (2024).

Benson, D. A., Wheatcraft, S. W. & Meerschaert, M. M. Application of a fractional advection-dispersion equation. Water Resour. Res. 36(6), 1403–1412 (2000).

Liu, F., Anh, Vo., Turner, I. & Zhuang, P. Time fractional advection–dispersion equation. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 13(1–2), 233–245 (2003).

Sun, L., Qiu, H., Wu, C., Niu, J. & Hu, B. X. A review of applications of fractional advection–dispersion equations for anomalous solute transport in surface and subsurface water. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Water 7(4), e1448 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Hierarchical fractional advection–dispersion equation (FADE) to quantify anomalous transport in river corridor over a broad spectrum of scales: theory and applications. Mathematics 9(7), 790–790 (2021).

Allwright, A. & Atangana, A. Augmented upwind numerical schemes for the groundwater transport advection–dispersion equation with local operators. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 87(9), 437–462 (2018).

Allwright, A. & Atangana, A. Augmented upwind numerical schemes for a fractional advection–dispersion equation in fractured groundwater systems. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst.-S 13(3), 443–466 (2020).

Allwright, A., Atangana, Abdon & Mekkaoui, Toufik. Fractional and fractal advection–dispersion model. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. - S 14(7), 2055–2055 (2021).

Lin, M. & Ou, Z. The analytical method of two-term time-fractional advection–dispersion–reaction models with sorption process. Alex. Eng. J. 114, 702–710 (2024).

Tajadodi, H. Variable-order Mittag–Leffler fractional operator and application to mobile–immobile advection–dispersion model. Alex. Eng. J. 61(5), 3719–3728 (2022).

Singh, J., Secer, A., Swroop, R. & Kumar, D. A reliable analytical approach for a fractional model of advection–dispersion equation. Nonlinear Eng. 8(1), 107–116 (2019).

Rahman, Riaz Ur et al. Dynamical behavior of fractional nonlinear dispersive equation in Murnaghan’s rod materials. Results Phys. 56, 107207–107207 (2024).

Pareek, N., Gupta, A., Agarwal, G. & Suthar, D. L. Natural transform along with HPM technique for solving fractional ADE. Adv. Math. Phys. 2021, 1–11 (2021).

Alshehry, Azzh Saad, Yasmin, H., Ghani, F., Shah, R. & Nonlaopon, Kamsing. Comparative analysis of advection–dispersion equations with Atangana–Baleanu fractional derivative. Symmetry 15(4), 819–819 (2023).

Iqbal, M., Seadawy, A. R., Lu, D. & Zhang, Z. Computational approaches for nonlinear gravity dispersive long waves and multiple soliton solutions for coupled system nonlinear (2+ 1)-dimensional Broer–Kaup–Kupershmit dynamical equation. Int. J. Geom. Methods Mod. Phys. 21(07), 2450126 (2024).

Jin, J., Chen, W., Ouyang, A., Yu, F. & Liu, H. A time-varying fuzzy parameter zeroing neural network for the synchronization of chaotic systems. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 8(1), 364–376 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. PATNAS: A path-based training-free neural architecture search. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 47(3), 1484–1500 (2025).

Tian, Z., Lee, A. & Zhou, S. Adaptive tempered reversible jump algorithm for Bayesian curve fitting. Inverse Probl. 40(4), 045024 (2024).

Iqbal, M. et al. Analysis of periodic wave soliton structure for the wave propagation in nonlinear low-pass electrical transmission lines through analytical technique. Ain Shams Eng. J. 16(9), 103506 (2025).

Iqbal, N., Botmart, T., Mohammed, W. W. & Ali, A. Numerical investigation of fractional-order Kersten–Krasil shchik coupled KdV–mKdV system with Atangana–Baleanu derivative. Adv. Contin. Discret. Model. 2022(1), 37 (2022).

Alshammari, M., Iqbal, N. & Ntwiga, D. B. A comparative study of fractional-order diffusion model within Atangana–Baleanu–Caputo operator. J. Funct. Spaces 2022(1), 9226707 (2022).

Iqbal, N. The fractional-order system of singular and non-singular thermo-elasticity system in the sense of homotopy perturbation transform method. Fractals 31(10), 2340166 (2023).

Jin, J. et al. A robust predefined-time convergence zeroing neural network for dynamic matrix inversion. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 53(6), 3887–3900 (2023).

Bo, Y., Tian, D., Liu, X. & Jin, Y. Discrete maximum principle and energy stability of the compact difference scheme for two-dimensional Allen–Cahn equation. J. Funct. Spaces 2022, 1–15 (2022).

Jin, J., Zhu, J., Zhao, L. & Chen, L. A fixed-time convergent and noise-tolerant zeroing neural network for online solution of time-varying matrix inversion. Appl. Soft Comput. 130, 109691–109691 (2022).

Batiha, I. M. et al. On discrete FitzHugh–Nagumo reaction-diffusion model: Stability and simulations. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 11, 100870 (2024).

Farea, A., Yli-Harja, O. & Emmert-Streib, F. Understanding physics-informed neural networks: Techniques, applications, trends, and challenges. AI 5(3), 1534–1557 (2024).

Luo, K. et al. Physics-informed neural networks for PDE problems: A comprehensive review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 58(10), 1–43 (2025).

Lotfi, E. M., Zine, H., Torres, M. & Yousfi, Noura. The power fractional calculus: First definitions and properties with applications to power fractional differential equations. Mathematics 10(19), 3594–3594 (2022).

Mohammed, P. O., Srivastava, H. M., Baleanu, Dumitru & Abualnaja, K. M. Modified fractional difference operators defined using Mittag–Leffler kernels. Symmetry 14(8), 1519–1519 (2022).

Al-Refai, M., Baleanu, Dumitru & Alomari, A. K. On the solutions of fractional differential equations with modified Mittag–Leffler kernel and Dirac Delta function: Analytical results and numerical simulations. PLoS ONE 20(6), e0325897–e0325897 (2025).

Partohaghighi, M., Mortezaee, M., Akgül, A. & Eldin, S. M. Numerical estimation of the fractional advection–dispersion equation under the modified Atangana–Baleanu–Caputo derivative. Results Phys. 49, 106451 (2023).

Chawla, R., Deswal, K. & Kumar, D. A novel finite difference based numerical approach for Modified Atangana–Baleanu Caputo derivative. AIMS Math 7(9), 17252–17268 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2025-23).

Funding

This research was funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, Project No. (TU-DSPP-2025-23).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EAA: Writing-Original draft preparation, Methodology. ASH: Visualization, Validation. MI: Conceptualization, Supervision. AA: Software, Data curation. MAT: Data curation, Writing-Reviewing & Editing. NEA: Investigation, Writing-Reviewing & Editing. FKAAH: Software, Data curation. NM: Formal analysis, Investigation. DB: Formal analysis, Writing-Reviewing & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Az-Zo’bi, E.A., Hussain, A.S., Iqbal, M. et al. Analytical and numerical solutions of MABC fractional advection dispersion models by utilizing the modified physics informed neural networks with impacts of fractional derivative. Sci Rep 15, 43366 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30065-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30065-7