Abstract

This study aimed to analyze the correlations between the induction (Δ) of higher-order aberrations (HOAs) and the effective optical zone (EOZ) in keratorefractive lenticule extraction (KLEx) and wavefront-guided laser in situ keratomileusis (WG-LASIK), and to examine the effect of EOZ size on these correlations. This retrospective observational study included patients treated with KLEx and WG-LASIK for myopia or myopic astigmatism between 2018 and 2022. ΔHOAs and EOZ parameters were analyzed using Scheimpflug imaging at one month after surgery. Correlation analysis and multivariate linear regression between EOZ parameters and ΔHOAs were performed. A total of 271 eyes were included, of which 141 underwent KLEx and 130 underwent WG-LASIK. In eyes with smaller EOZ areas (≤ 24.9 mm²), EOZ decentration in KLEx showed positive correlations with Δcoma and Δvertical coma (correlation coefficient (ρ) = 0.551 and 0.524, respectively). EOZ decentration on the Y-axis in KLEx also correlated positively with Δvertical coma (ρ = 0.540), while in WG-LASIK, EOZ decentration on the X-axis correlated with Δcoma (ρ = 0.522) under similarly small EOZ areas. EOZ size parameters significantly contributed to Δspherical aberration in both procedures (p < 0.001). Conversely, these correlations were either not observed or significantly smaller in eyes with larger EOZ areas (> 24.9 mm²). In conclusion, maintaining a sufficiently large EOZ postoperatively is crucial. Moreover, precise surgical centration is vital for patients with smaller EOZ sizes, to reduce the induction of HOAs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Refractive surgery is one of the most commonly performed elective procedures, known for its highly predictable outcomes1. A review of 97 articles published since 2008 on laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) reported that over 98.6% of patients achieved final target refraction within ± 1.0 diopter2. Despite the excellent refraction outcome, night vision complaints (NVCs) remained a significant issue post-LASIK. According to Pop et al., 26% of LASIK patients experienced NVCs one month after surgery3. These symptoms were closely linked to the induction (Δ) of higher-order aberrations (HOAs) by the conventional ablation profile of LASIK4,5,6.

To address this, two advanced surgical procedures had gained popularity: wavefront-guided LASIK (WG-LASIK) and keratorefractive lenticule extraction (KLEx). WG-LASIK minimizes HOAs through customized aspheric ablation profiles based on whole-eye aberration data, while KLEx reduces flap-induced HOAs due to its flapless, minimally invasive procedure7,8. Despite advancements in these techniques, NVCs persisted in patients undergoing WG-LASIK and KLEx. Hannan et al. reported that over 20% of patients experienced moderate to severe difficulty with glare, halo and starbursts one month post-WG-LASIK9. In the case of KLEx, fluctuation in vision and glare affected 73.1% and 65.5% of patients, respectively, at least 3 months after surgery10.

The optical zone had also been implicated in NVCs in refractive surgery patients11. Effective optical zone (EOZ), the actual ablated corneal region providing functional vision, had been studied in both WG-LASIK and KLEx12,13. Given that both optical zone and HOAs were associated with night vision complaints4,5,6,11, analyzing the EOZ and its correlation with ΔHOAs was important. Moreover, previous studies had suggested that a larger EOZ may increase tolerance to EOZ decentration, reducing ΔHOAs14. However, only one study had compared EOZ and ΔHOA across different surgical modalities. Moshirfar et al. examined the correlation between EOZ and HOAs among femtosecond LASIK (FS-LASIK), photorefractive keratectomy and KLEx15, but the study had a relatively small sample size in each group and did not focus on customized FS-LASIK, which represents a notable gap in the current literature.

To address this gap, the purpose of our study was to identify differences in EOZ size, decentration and shape between KLEx and WG-LASIK, and their correlations with ΔHOAs. Additionally, we aimed to examine the impact of EOZ size on these correlations.

Methods

This study included consecutive patients who underwent either KLEx with small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) procedure or WG-LASIK at Taipei Chang Gung Memorial Hospital by Dr. Chi-Chin Sun between November 2018 and November 2022, with at least one-month postoperative follow-up. We excluded patients with (1) history of refractive/ocular surgeries, ocular diseases other than refractive errors, or autoimmune diseases; (2) insufficient postoperative follow-up; (3) incomplete medical records, and (4) other ocular surgeries during the follow-up period. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the institutional review board (IRB no.: 202401177B0) of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

Ophthalmic examinations

Preoperative comprehensive examinations were conducted for each eye to evaluate the eligibility for refractive surgery. All patients also completed a postoperative follow-up for at least one month. We performed history taking, manifest refraction measurement, non-contact intraocular pressure assessment, scotopic pupil size measurement, slit-lamp and fundoscopic examinations, corneal tomography examination and HOAs assessment before and one month after surgery. Additional EOZ evaluation was conducted one month postoperatively. Scotopic pupil size was measured using the Hartmann-Shack aberrometer (iDesign; J&J Vision, Santa Ana, CA). Corneal tomography data, including central corneal thickness (CCT), thinnest corneal thickness (TCT), mean keratometry (Km), anterior corneal Q-value, and angle kappa, were obtained using the Pentacam HR (Oculus, Wetzlar, Germany).

Measurements of HOAs

Wavefront aberrations of the total cornea were measured using Pentacam HR (Oculus, Wetzlar, Germany). Data within a 6.0 mm zone centered at the corneal vertex (CV) were collected preoperatively and at one month postoperatively up to the sixth order. Zernike analysis provided root-mean-square values for total HOA, coma (\(\:{Z}_{3}^{1}\), \(\:{Z}_{3}^{-1}\), \(\:{Z}_{5}^{1}\), \(\:{Z}_{5}^{-1}\)), vertical coma (\(\:{Z}_{3}^{-1}\), \(\:{Z}_{5}^{-1}\)), horizontal coma (\(\:{Z}_{3}^{1}\), \(\:{Z}_{5}^{1}\)), spherical aberration (SA, \(\:{Z}_{4}^{0}\)), trefoil (\(\:{Z}_{3}^{3}\), \(\:{Z}_{3}^{-3}\), \(\:{Z}_{5}^{3}\), \(\:{Z}_{5}^{-3}\)), oblique trefoil (\(\:{Z}_{3}^{3}\), \(\:{Z}_{5}^{3}\)), and horizontal trefoil (\(\:{Z}_{3}^{-3}\), \(\:{Z}_{5}^{-3}\)). ΔHOAs was calculated by subtracting the preoperative HOA from the postoperative HOA.

Measurement of EOZ

The EOZ was defined using the tangential curvature difference map (TCDM) generated from Pentacam13,16,17. The colored area representing zero curvature difference displayed on the TCDM of corneal topography before and one month after surgery was identified as the EOZ. Image J software (version 1.54; National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD) was used to analyze the EOZ of each eye. To begin, three investigators (THT, ETL, BCC) isolated EOZ from TCDM with a color threshold, and the images were then transformed into binary format. The EOZ parameters, classified into size, decentration, and shape, were then extracted and analyzed using relevant functions within ImageJ. Size parameters included area (mm2), perimeter (mm), major axis (mm) and minor axis (mm). Changes in optical zone area relative to planned optical zone (POZ) were expressed as the optical zone reduction ratio (RR = EOZ/POZ, %). Decentration parameters were calculated based on the distance between the centroid of measured EOZ to corneal vertex (CV) from the Pentacam. These parameters included decentration (mm, absolute decentration distance between centroid and CV), Y-decentration (mm, positive value means centroid superior to CV and negative value means centroid inferior to CV), and X-decentration (mm, positive means centroid nasal to CV and negative value means centroid temporal to CV). Acircularity was calculated by dividing the perimeter of EOZ by the perimeter of a circle with equal area to EOZ, quantifying the shape deviation from a circular EOZ.

KLEx procedure

All KLEx surgeries were performed using the VisuMax 500-Hz laser system (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Germany). The pulse energy was set at 140nJ, with a POZ of 6.0–7.0 mm centered on CV, a cap diameter between 7.0 and 8.0 mm, and a cap thickness of 100–120 μm. A 3.0 mm incision was made at the 11 o’clock position in all eyes. Postoperatively, the cornea was irrigated with balanced salt solution, and patients were prescribed topical 1% prednisolone acetate ophthalmic suspension (Prednicone; Winston) and 0.5% levofloxacin ophthalmic solution (Cravit; Santen) four times daily for two weeks.

WG-LASIK procedure

Preoperative calculations for ablation profiles were made using a Hartmann-Shack aberrometer (iDesign; J&J Vision, Santa Ana, CA), and flaps were created with a 150-kHz intralase femtosecond laser (iFS, J&J Vision, Santa Ana, CA). A superior hinge of the flap was made with a diameter of 9.0 mm and a thickness of 100–120 μm. After the flap was lifted, ablation was performed using the VISX Star S4 IR excimer laser (J&J Vision, Santa Ana, CA), with a planned optical zone (POZ) of 6.0–7.5 mm centered on the pupil, and an ablation zone of 8.0 mm. X-Y-Z tracking and iris registration for torsional tracking were performed in all eyes. Postoperatively, the cornea was irrigated with balanced salt solution, and patients were prescribed the same postoperative regimen as for SMILE.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS software (version 26; IBM Inc., Chicago). Sample size calculation focused on our primary endpoint, the correlation between the ΔHOAs and EOZ parameters. The estimated sample size was calculated using the Fisher’s z-transformation with the following formula:

\(\:n={\left(\frac{{Z}_{\frac{\alpha\:}{2}}+{Z}_{\beta\:}}{0.5\text{ln}\left(\frac{1+r}{1-r}\right)}\right)}^{2}+3\), based on a significance level of 0.05, power of 0.8 and a large effect size (correlation coefficient (ρ)=0.5), resulting in a minimum required sample size of 29 for each surgical group. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess normal distribution for the population, revealing a non-parametric distribution. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages, while continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Group differences for continuous data were analyzed using Mann-Whitney tests, and categorical variables were compared using Chi-square tests.

Subgroup analysis of ΔHOAs and EOZ parameters was conducted based on a fixed POZ size, set at 6.8 mm for KLEx and WG-LASIK patients. Spearman’s correlation test was used to evaluate the relationships between EOZ parameters and ΔHOAs. EOZ parameters were categorized into two clinically meaningful subgroups: size-related parameters (RR, major axis, and minor axis) and decentration-related parameters (decentration, absolute X- and Y-decentration), and were independently adjusted using the Bonferroni correction to control type I error (α), with correlations considered statistically significant at p-value < corrected α. To further evaluate the independent effects of the variables, stepwise multivariate linear regression was conducted to identify the EOZ parameters that independently contributed to each ΔHOA.

Results

Preoperative patient characteristics

Our study included 271 eyes from 136 patients: 141 eyes from 71 patients underwent KLEx (mean age: 31.1 ± 6.2 years), and 130 eyes from 65 patients underwent WG-LASIK (mean age: 29.1 ± 4.8 years). Preoperative characteristics for both groups were detailed in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the KLEx and WG-LASIK groups in terms of sex, age, spherical diopters (SDs), cylindrical diopters (CDs), spherical equivalents (SEs), Km, scotopic pupil size, CCT, TCT, Q value, angle kappa, and HOAs. Notably, the KLEx group had a smaller POZ compared to the WG-LASIK group (6.61 ± 0.23 mm vs. 6.92 ± 0.25 mm, p < 0.001).

Comparison of ΔHOAs and EOZ parameters one month after surgery

Supplementary Table S1 presented the postoperative induction of HOAs and EOZ parameters for the KLEx and WG-LASIK groups. The KLEx group exhibited higher postoperative increases in total HOA, coma, vertical coma, and spherical aberration compared to the WG-LASIK group (p = 0.002, p = 0.011, p = 0.01, p < 0.001, respectively). Additionally, superior Y-decentration of the EOZ was significantly greater in the KLEx group (p < 0.001). In contrast, EOZ size parameters and acircularity were greater in the WG-LASIK group (p < 0.001).

We selected patients from our cohort who had a POZ of 6.8 mm, as shown in Table 2. The induction of HOAs did not significantly differ between the two groups. Regarding EOZ parameters, area reduction ratio was significantly less in the KLEx group compared to the WG-LASIK group (p = 0.027). Additionally, both the minor axis and superior Y-decentration were significantly greater in the KLEx group (p < 0.001). Conversely, acircularity was greater in the WG-LASIK group (p < 0.001).

Correlation analysis between ΔHOAs and EOZ parameters

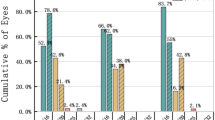

Both surgery groups were subcategorized into larger and smaller EOZ groups for correlation analysis based on the first quartile of EOZ area (24.9 mm²) in the WG-LASIK group, ensuring all groups met the minimum sample size requirement. For EOZ size parameters, major and minor axes exhibited significant negative correlations with ΔSA in both surgeries when EOZ ≤ 24.9 mm² (ρ < −0.5; p < 0.001). These correlations were not observed in patients with larger EOZ. Detailed comparisons were shown in Fig. 1.

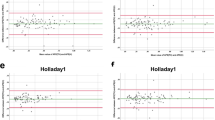

Regarding the correlations between EOZ decentration and ΔHOAs, stronger and more significant associations were observed in patients with smaller EOZ areas in both surgery groups. In KLEx patients with EOZ ≤ 24.9 mm², EOZ decentration showed significant positive correlations with Δcoma and Δvertical coma (ρ = 0.551, 0.524; p < 0.001). Absolute Y-decentration was correlated with the Δvertical coma (ρ = 0.540; p < 0.001). In WG-LASIK patients with EOZ ≤ 24.9 mm², absolute X-decentration was correlated with Δcoma (ρ = 0.522, p = 0.002). Detailed comparisons are shown in Fig. 2.

Multivariate linear regression analysis between ΔHOAs and EOZ parameters

The multivariate regression models between ΔHOAs and significantly correlated EOZ parameters were performed. Nine significant models (model p < 0.001) with adjusted R² > 0.20 were listed in Table 3, all within the smaller EOZ groups. In the EOZ ≤ 24.9 mm² group, EOZ minor axis was a significant contributing factor to Δtotal HOA (p < 0.001 in KLEx and p = 0.007 in WG-LASIK) and to ΔSA (both p < 0.001) in both surgeries.

Among KLEx patients, EOZ decentration was significantly associated with Δtotal HOA, Δcoma, Δvertical coma, and ΔSA (p < 0.001). Additionally, the EOZ minor axis contributed to Δcoma and Δvertical coma (both p < 0.001), while absolute X-decentration was associated with Δhorizontal coma (p < 0.001). EOZ major axis was included in the models for Δhorizontal coma (p = 0.004) and ΔSA (p < 0.001). In the WG-LASIK group, absolute X-decentration was correlated with Δtotal HOA (p = 0.003), Δcoma, and Δhorizontal coma (p < 0.001).

Postoperative visual outcomes in KLEx and WG-LASIK

Visual and refractive outcomes in KLEx and WG-LASIK were shown in Supplementary Figure S1. There was no statistical difference in UDVA, CDVA, and SEs between the two groups (p = 0.291, p = 0.577, p = 0.619, respectively). Both surgical procedures demonstrated good refractive outcomes including safety, efficacy, predictability and post-operative 6-month stability.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated the correlations between ΔHOAs and EOZ parameters, as well as the effect of EOZ area on these correlations. Regression models were also proposed to identify significant EOZ parameters contributing to ΔHOAs. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating relationships ΔHOAs and EOZ parameters between KLEx and customized WG-LASIK.

Preoperatively, there was no statistically significant differences between the two surgery groups except that the POZ was significantly larger in the WG-LASIK group. Our retrospective cohort reflected real-world data where POZ was not set at a fixed value, and the flap-lifting excimer laser ablation in WG-LASIK allowed for easier design of a larger POZ compared to KLEx, which likely led to significantly less Δtotal HOAs, Δcoma, Δvertical coma, and ΔSA in the WG-LASIK group. This aligns with previous findings suggesting that smaller attempted optical zone might lead to a greater HOA induction18,19,20. Conversely, EOZ size parameters were greater in the WG-LASIK group, attributable to the same reason.

In the POZ-matched subgroup analysis, ΔHOA did not differ significantly between WG-LASIK and KLEx, corroborating the results of a previous contralateral-eye randomized controlled trial21. Conversely, WG-LASIK produced a larger proportional reduction in the EOZ area, consistent with reports that FS-LASIK induces greater EOZ shrinkage than KLEx15,22,23,24,25. This difference is likely attributed to the higher peripheral energy loss of excimer-laser ablation and the associated corneal-remodeling response22,23,25,26. Although several studies have described a larger absolute EOZ after KLEx22,23,24,25, we observed no overall difference in EOZ size, apart from a shorter minor axis in WG-LASIK eyes. This axis asymmetry aligns with the circular lenticule geometry of KLEx versus the aspheric ablation profile of WG-LASIK. The stronger postoperative remodeling associated with LASIK likely exacerbates this asymmetry, contributing to the greater EOZ acircularity noted after excimer-laser treatment. Liu and colleagues documented a similar pattern24.

Decentration patterns varied between the procedures, with KLEx showing more superonasal EOZ and WG-LASIK more inferotemporal EOZ. Greater superior vertical decentration was observed in the KLEx group, consistent with previous studies15,25,27. This decentration is likely due to involuntary Bell’s phenomenon during the docking phase and the absence of eye-tracking technology27. Horizontally, our results were consistent with those of Moshirfar’s study, which also used TCDM for EOZ measurement: KLEx exhibited more nasal decentration, whereas LASIK showed temporal decentration. As they proposed—and as supported by our data—this pattern reflects the choice of reference axis. Both EOZ and HOA were referenced to the corneal vertex (CV), yet WG-LASIK was centrated on the pupil, which lies naturally inferotemporal to the CV. Consequently, the resulting EOZ in WG-LASIK appears decentered15.

EOZ or POZ size had been shown to negatively associate with the induction of HOAs, especially SAs15,19,20,22,24,28,29. Similar to previous studies, EOZ size parameters including major and minor axis showed significant negative correlations with ΔSA in both surgeries based on our analysis, consistent with the idea that smaller optical zones can misalign rays passing through the treated cornea, inducing SA15. In terms of EOZ decentration, it had been shown to positively correlated with the induction of coma, particularly vertical coma in KLEx surgery7,16,28,30,31. Disrupted ocular path due to decentered EOZ could lead to image distortion, resulting in coma induction. Our findings aligned with this, showing that in the KLEx group, EOZ decentration significantly correlated with Δcoma and Δvertical coma, while absolute y-decentration correlated with Δvertical coma.

In WG-LASIK, the correlations between EOZ parameters and ΔHOAs were much weaker, likely due to the idea that larger POZ/EOZ areas increased tolerance to EOZ decentration14. Subgroup analysis based on EOZ size provided supporting evidence on the theory, indicating that smaller EOZ areas were associated with stronger correlations between EOZ size or decentration and ΔHOAs in both surgery groups. The result suggested that surgical centration was more important in patients with anticipated small EOZ.

Multivariate regression analysis identified significant factors contributing to the induction of HOAs, particularly in smaller EOZ subgroups. EOZ size parameters were crucial factors for ΔSA, while decentration parameters significantly influenced the induction of coma, aligning with past studies7,15,16,19,20,22,24,28,29,30,31. In KLEx patients, the EOZ minor axis was the strongest contributing factor to Δtotal HOA, Δcoma, Δvertical coma, and ΔSA among all size parameters. We hypothesize that the minor axis, delineating the shortest optical zone border, may contribute to ΔHOAs due to the misalignment of light rays at this border, potentially exacerbating the induction of aberrations, which may impact overall visual quality. In clinical practice, patients with higher corneal astigmatism undergoing excimer laser refractive surgery may be at increased risk for a more eccentric postoperative EOZ32. In such cases, careful consideration is required, as a smaller minor axis could lead to greater ΔHOAs. In addition, absolute X-decentration contributed to Δhorizontal coma in both groups and was additionally associated with Δtotal HOA and Δcoma in WG-LASIK. The greater impact observed in WG-LASIK likely reflects centration differences, as KLEx was centered on the corneal vertex using triple marking centration methods, whereas LASIK POZ was pupil-centered.

Several limitations were identified in our study. First, there was variation in the POZ size between the two surgical groups. This discrepancy reflects real-world practice, where a larger POZ size in WG-LASIK is associated with improved ΔHOA outcomes. To address this, we conducted multiple subgroup analyses to account for its potential impact. Second, the study was retrospective in design and limited by a short follow-up period. However, previous research indicates that EOZ size stabilized shortly after procedures such as KLEx and FS-LASIK, remaining relatively consistent beyond the initial one-week period25. Future prospective studies are still warranted to validate our findings.

In conclusion, our study is the first to investigate EOZ parameters and analyze the correlations between ΔHOAs and EOZ in both KLEx and WG-LASIK. Our results indicated that ΔHOAs were comparable between KLEx and WG-LASIK with the same POZ. Notably, KLEx patients exhibited more superonasal EOZ decentration and regular EOZ shapes compared to WG-LASIK patients. In addition, ensuring a sufficiently large EOZ post-surgery and achieving precise surgical centration are crucial to minimizing ΔHOAs, particularly in patients with suboptimal EOZ sizes.

Data availability

All data available upon formal request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- KLEx:

-

Keratorefractive lenticule extraction

- WG-LASIK:

-

Wavefront-guided laser in situ keratomileusis

- POZ:

-

Planned optical zone

- CCT:

-

Central corneal thickness

- TCT:

-

Thinnest corneal thickness

- KM:

-

Mean keratometry

- µ:

-

Chord distance (mm)

- µ(x) & µ(y):

-

x & y deviation of CV from PC (mm)

- RMS:

-

Root mean square

- HOA:

-

Higher order aberration

- SA:

-

Spherical aberration

References

Kim, T. I., Barrio, A. D., Wilkins, J. L., Cochener, M., Ang, M. & B. & Refractive surgery. Lancet 393, 2085–2098. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33209-4 (2019).

Sandoval, H. P. et al. Modern laser in situ keratomileusis outcomes. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 42, 1224–1234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2016.07.012 (2016).

Pop, M. & Payette, Y. Risk factors for night vision complaints after LASIK for myopia. Ophthalmology 111, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.022 (2004).

Chalita, M. R., Chavala, S., Xu, M. & Krueger, R. R. Wavefront analysis in post-LASIK eyes and its correlation with visual symptoms, refraction, and topography. Ophthalmology 111, 447–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.06.022 (2004).

Villa, C., Gutierrez, R., Jimenez, J. R. & Gonzalez-Meijome, J. M. Night vision disturbances after successful LASIK surgery. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 91, 1031–1037. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2006.110874 (2007).

Sharma, M., Wachler, B. S. & Chan, C. C. Higher order aberrations and relative risk of symptoms after LASIK. J. Refract. Surg. 23, 252–256. https://doi.org/10.3928/1081-597X-20070301-07 (2007).

Tian, H., Gao, W., Xu, C. & Wang, Y. Clinical outcomes and higher order aberrations of wavefront-guided LASIK versus SMILE for correction of myopia: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Acta Ophthalmol. 101, 606–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.15638 (2023).

Fuest, M. & Mehta, J. S. Advances in refractive corneal lenticule extraction. Taiwan. J. Ophthalmol. 11, 113–121. https://doi.org/10.4103/tjo.tjo_12_21 (2021).

Hannan, S. J. et al. Comparison of the 1st generation and 3rd generation wavefront-guided LASIK for the treatment of myopia and myopic astigmatism. Clin. Ophthalmol. 17, 3579–3590. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S434037 (2023).

Schmelter, V. et al. Determinants of subjective patient-reported quality of vision after small-incision lenticule extraction. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 45, 1575–1583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2019.06.012 (2019).

Fan-Paul, N. I., Li, J., Miller, J. S. & Florakis, G. J. Night vision disturbances after corneal refractive surgery. Surv. Ophthalmol. 47, 533–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0039-6257(02)00350-8 (2002).

Elshawarby, M. A., Saad, A., Helmy, T., Seleet, M. M. & Elraggal, T. Functional optical zone after wavefront-optimized versus wavefront-guided laser in situ keratomileusis. Med. Hypothesis Discov Innov. Ophthalmol. 10, 129–137. https://doi.org/10.51329/mehdiophthal1431 (2021).

Huang, Y., Zhan, B., Han, T. & Zhou, X. Effective optical zone following small incision lenticule extraction: a review. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 262, 1657–1665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-023-06263-2 (2024).

Lee, H. et al. Relationship between decentration and induced corneal higher-order aberrations following small-incision lenticule extraction procedure. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59, 2316–2324. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.17-23451 (2018).

Moshirfar, M. et al. Comparing effective optical zones after myopic ablation between LASIK, PRK, and SMILE with correlation to higher order aberrations. J. Refract. Surg. 39, 741–750. https://doi.org/10.3928/1081597X-20231016-02 (2023).

Sun, L. et al. Changes in effective optical zone after small-incision lenticule extraction in high myopia. Int. Ophthalmol. 42, 3703–3711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-022-02367-6 (2022).

Liang, C. & Yan, H. Methods of corneal vertex centration and evaluation of effective optical zone in small incision lenticule extraction. Ophthalmic Res. 66, 717–726. https://doi.org/10.1159/000529922 (2023).

Seo, K. Y., Lee, J. B., Kang, J. J., Lee, E. S. & Kim, E. K. Comparison of higher-order aberrations after LASEK with a 6.0 mm ablation zone and a 6.5 mm ablation zone with blend zone. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 30, 653–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2003.09.039 (2004).

Ozulken, K. & Kaderli, A. The effect of different optical zone diameters on the results of high-order aberrations in femto-laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 30, 1272–1277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1120672119865688 (2020).

Fu, D., Wang, L., Zhou, X. & Yu, Z. Functional optical zone after small-incision lenticule extraction as stratified by attempted correction and optical zone. Cornea 37, 1110–1117. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000001669 (2018).

Chiang, B., Valerio, G. S. & Manche, E. E. Prospective, randomized contralateral eye comparison of Wavefront-Guided laser in situ keratomileusis and small incision lenticule extraction refractive surgeries. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 237, 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2021.11.013 (2022).

Hou, J., Wang, Y., Lei, Y. & Zheng, X. Comparison of effective optical zone after small-incision lenticule extraction and femtosecond laser-assisted laser in situ keratomileusis for myopia. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 44, 1179–1185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2018.06.046 (2018).

Damgaard, I. B. et al. Functional optical zone and centration following SMILE and LASIK: A prospective, randomized, contralateral eye study. J. Refract. Surg. 35, 230–237. https://doi.org/10.3928/1081597X-20190313-01 (2019).

Liu, S. et al. Comparison of the functional optical zone in eyes with high myopia with high astigmatism after SMILE and FS-LASIK. J. Refract. Surg. 38, 595–601. https://doi.org/10.3928/1081597X-20220725-01 (2022).

He, S. et al. Prospective, randomized, contralateral eye comparison of functional optical Zone, and visual quality after SMILE and FS-LASIK for high myopia. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 11, 13. https://doi.org/10.1167/tvst.11.2.13 (2022). Prospective.

Wei, P. et al. Changes in corneal volume at different areas and its correlation with corneal biomechanics after SMILE and FS-LASIK surgery. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 1713979. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1713979 (2020).

Vingopoulos, F., Zisimopoulos, A. & Kanellopoulos, A. J. Comparison of effective corneal refractive centration to the visual axis: LASIK vs SMILE, a contralateral eye digitized comparison of the postoperative result. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 47, 1511–1518. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000000687 (2021).

Ding, X., Fu, D., Wang, L., Zhou, X. & Yu, Z. Functional optical zone and visual quality after small-incision lenticule extraction for high myopic astigmatism. Ophthalmol. Ther. 10, 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-021-00330-9 (2021).

Zhou, C., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Fan, Q. & Dai, L. Comparison of visual quality after SMILE correction of low-to-moderate myopia in different optical zones. Int. Ophthalmol. 43, 3623–3632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-023-02771-6 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Mild decentration measured by a Scheimpflug camera and its impact on visual quality following SMILE in the early learning curve. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55, 3886–3892. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.13-13714 (2014).

Chan, T. C. Y. et al. Effect of corneal curvature on optical zone decentration and its impact on astigmatism and higher-order aberrations in SMILE and LASIK. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 257, 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-018-4165-8 (2019).

Moshirfar, M. et al. Correlational analysis of the effective optical zone with myopia, myopic astigmatism, and spherical equivalent in LASIK, PRK, and SMILE. Clin. Ophthalmol. 18, 377–392. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S440608 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jing-Yi Huang for the statistical consultation and wish to acknowledge for statistical and data analysis assistance and interpretation by the Centre for Big Data Analytics and Statistics, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou. Additionally, the authors would like to acknowledge the use of ChatGPT 4o, developed by OpenAI, for grammar and language editing assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. The authors have reviewed and verified the accuracy of the content.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ETL and THT collected the data, conducted the analysis, prepared the figures, and drafted the manuscript. WHL, NNC, and PCC contributed to data acquisition and assisted in analysis. CCS conceived the project, supervised the research, and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The research followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board (IRB no.: 202401177B0) of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

Consent to participate

This is an IRB-approved retrospective study; all patient information was de-identified, and the IRB of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital waived the requirement for informed consent. Patient consent was therefore not required, and patient data will not be shared with third parties.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, ET., Tsai, TH., Lin, WH. et al. Correlation between effective optical zone and higher-order aberrations in keratorefractive lenticule extraction and wavefront-guided laser in situ keratomileusis. Sci Rep 16, 529 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30070-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30070-w