Abstract

This study developed an efficient extraction process for flavonoids from Broussonetia papyrifera leaves using the response surface methodology. The optimized flavonoids exhibited remarkable antioxidant activity, effectively scavenging DPPH, hydroxyl, and ABTS radicals. UPLC-MS/MS analysis preliminarily identified numerous flavonoid compounds in the extract.. The extract also demonstrated potent broad-spectrum antibacterial efficacy against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Candida albicans. These findings indicate that the extracted flavonoids may serve as natural antioxidants and antimicrobials in the food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics industries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) L’Hér. ex Vent. is native to China and the subtropical regions of Southeast and East Asia1. Its roots, bark, and fruits have long been used in traditional Chinese medicine. The species has medicinal, edible, and fodder applications and is valued for its nutrient and bioactive content. Its leaves, rich in amino acids, represent a valuable unconventional feed source for animals2. The plant also contains polysaccharides, proteins, flavonoids, phenylpropanoids, and other polyphenols3. In traditional Chinese medicine, dried twigs, leaves, and roots are prescribed for diuresis, tonification, and edema reduction4.

Flavonoids, a major class of natural polyphenols, include quercetin, kaempferol, catechin, luteolin, and apigenin5. They have been reported to slow aging, alleviate oxidative stress and inflammation, protect the blood–brain barrier, and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, immune disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease6,7,8. In animal husbandry, the use of flavonoids has received increasing attention. They are considered potential green feed additives because of their antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and other biological properties, which may reduce the use of traditional antibiotics and improve animal health and production performance9,10. To efficiently extract flavonoids, modern technologies such as ultrasound-assisted extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, and enzymatic extraction have been widely applied, substantially improving extraction efficiency and product purity11,12.

The traditional extraction methods of flavonoids include solvent extraction, crystallization, microfluidic technology, vacuum extraction, Soxhlet extraction and so on. However, these methods have problems such as long extraction time, expensive extraction equipment, low extraction efficiency, and the need for high purity solvents. Ultrasonic assisted extraction technology is to quickly enter the solvent under ultrasonic action based on the presence, polarity and solubility of other active ingredients in the substance to obtain a multi-component mixture, and then obtain the active substance monomer through appropriate separation and purification techniques. At present, this method has been widely used in the extraction and separation of active ingredients in natural products. Combining ultrasonic waves with traditional solvent extraction has the advantages of reducing extraction time, targeted heating, reducing solvent consumption, and high extraction rate, making it an effective method for extracting total flavonoids13. Currently, ultrasound has been used to extract a variety of plant flavonoids14,15. The study found that compared with the traditional Soxhlet extraction method, ultrasonic assisted extraction of total flavonoids can shorten the extraction time and improve the yield16. Ultrasonic assisted extraction technology can effectively avoid the damage of active ingredients by high temperature, and its extraction efficiency is mainly affected by key parameters such as ultrasonic frequency, time, and temperature. Therefore, determining appropriate ultrasonic extraction parameters is key to improving extraction efficiency. Meanwhile, the integration of ultrasonic technology with other emerging technologies will become a research hotspot. With the continuous innovation of scientific research technologies, ultrasonic extraction technology will demonstrate broader application prospects in fields such as food processing, pharmaceutical R&D, and chemical production17.

Although previous studies have examined the antioxidant activity of B. papyrifera leaves and the extraction process of total flavonoids, effective extraction and comprehensive evaluation remain at an exploratory stage. In particular, optimization of extraction parameters and systematic evaluation of the antioxidant and antibacterial potential of flavonoids to maximize their yield have not been fully resolved.

Materials and methods

Materials

B. papyrifera leaves were collected from the campus of Yellow River Institute of Science and Technology in September 2022. Botanical identification and confirmation of the leaves as being Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) L’Hér. ex Vent was performed by Professor Wang Li (Department of Pharmacy, School of Medicine, Yellow River Institute of Science and Technology). This species is currently preserved in the Herbarium of Huanghe University of Science and Technology (designation No. 20220622). Rutin (standard compound), antioxidant assay reagents, and the microbial strains Escherichia coli (ATCC 25,922), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25,923), and Candida albicans (ATCC 10,231) were provided by the Microbiology Laboratory of the Medical College of the same institution.

Determination of the total flavonoid content in B. papyrifera leaves

The total flavonoid content in the leaves was determined by NaNO2–Al(NO3)3 colorimetry18,19. The calibration curve yielded a linear regression equation Y = 9.7522X—0.0128 (R2 = 0.9993), displaying linearity from 0 to 0.06 mg/mL. The total flavonoid yield was calculated using the following formula:

Note: C is the total flavonoid concentration (expressed in mg/mL); V is the fixed volume (expressed in mL); M is the mass (expressed in g); N is the dilution multiple.

Single-factor experiment for the extraction of total flavonoids in B. papyrifera leaves

The collected fresh B. papyrifera leaves were dried in an oven, crushed, and sieved through a 20-mesh sieve to obtain B. papyrifera leaf powder and saved. The extraction yield of total flavonoids from B. papyrifera leaves was evaluated by using a single-factor experimental design as described elsewhere14,15. A single-factor experimental design was employed to investigate the effects of extraction time (i.e., 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 min), extraction temperature (i.e., 30, 40, 50, 60, 70 °C), solid-to-liquid ratio (i.e., 1:10, 1:20, 1:30, 1:40, 1:50 g/mL), and ethanol volume fraction (i.e., 50, 60, 70, 80, 90%). Each factor was tested independently across the specified levels.

Response surface method optimization experiment

Based on the results of the single-factor experiments, a response surface optimization experiment was designed using the Design-Expert 10.0 software. The total flavonoid yield served as the response variable. The experimental design matrix is presented in Table 1.

Identification of flavonoid constituents

To comprehensively characterize the chemical profile of the flavonoids present in the B. papyrifera leaves extract, a qualitative analysis was performed using ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem high-resolution mass spectrometry (UPLC-Orbitrap-MS).

The collected fresh B. papyrifera leaves were dried in an oven, crushed and sieved through a 20-mesh sieve to obtain B. papyrifera leaf powder. The powdered B. papyrifera leaves were extracted with 83% ethanol at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:35 (g/mL) using ultrasound-assisted extraction at 54.7 °C for 24.3 min. The resulting filtrate was collected, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The remaining extract was used for subsequent experiments.

The extracted sample were analyzed using a UPLC-Orbitrap-MS system (UPLC, Vanquish; MS, HFX). UPLC conditions: The analytical conditions were as follows, UPLC: column, Waters HSS T3(100 × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm); column temperature, 40 °C; flow rate, 0.3 mL/min; injection volume, 2 μL; solvent system, phase A were Milli-Q water (0.1% formic acid), phase B were acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid); gradient program, 0 min phase A/phase B (100:0, v/v), 1 min phase A/phase B (100:0, v/v), 12 min phase A/phase B (5:95, v/v), 13 min phase A/phase B (5:95, v/v), 13.1 min phase A/phase B (100:0, v/v), 17 min phase A/phase B (100:0, v/v). MS conditions: HRMS data were recorded on a Q Exactive HFX Hybrid Quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometer equipped with a heated ESI source (Thermo Fisher Scientific) utilizing the Full-ms-ddMS2 acquisition methods. The ESI source parameters were set as follows: sheath gas pressure, 40 arb; aux gas pressure, 10 arb; spray voltage, + 3000 v/-2800 v; temperature, 350℃; and ion transport tube temperature, 320℃. The scanning range of the primary mass spectrometry was (scan m/z range) 70–1050 Da, with a primary resolution of 70,000 and secondary resolution of 17,500.

External antioxidant experiment

Ability to remove DPPH-free radicals

Based on the methods of Zhang et al.20,21 with some modifications, 3 mL aliquots of the total flavonoid solution (derived from B. papyrifera leaves) at different mass concentrations were accurately transferred into test tubes, to which 3 mL of the DPPH solution was added. The mixtures were incubated in the dark for 30 min, and the absorbance (A₁) was measured at 517 nm. Using the same procedure, the absorbance values A2 and A0 were determined. Vitamin C (VC) was used as a positive control. The IC50 value was calculated as follows:

Ability to remove hydroxyl-free radicals

Based on the methods of Zhao et al.20,21 with modifications, 2 mL aliquots of each different mass concentration of the total flavonoid solution were accurately transferred into test tubes, to which 2 mL each of FeSO₄ solution, salicylic acid–ethanol solution, and H2O2 solution were added sequentially. The mixture was mixed well and allowed to react for 30 min. The absorbance (A₁) was measured at 510 nm. Using the same procedure, the absorbance values A2 and A0 were determined. VC was used as a positive control. The IC50 value was calculated as follows:

The ability to remove ABTS-free radicals

Based on the method of Chai et al.20,21 with some modifications, ABTS and K2S2O₈ were accurately weighed into a 25-mL volumetric flask. The reagents were mixed at a volume ratio of 1:1, protected from light, and stored at room temperature for 12–16 h to prepare the ABTS stock solution. Subsequently, the stock solution was diluted with anhydrous ethanol until its absorbance at 734 nm reached 0.7 ± 0.02, yielding the ABTS working solution.

Next, 1 mL aliquots of the total flavonoid solution (derived from B. papyrifera leaves) at different mass concentrations were accurately transferred. To each aliquot, 2.0 mL of the ABTS-working solution was added. The solutions were mixed well and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 10 min. The absorbance at 734 nm (A₁) was measured. Using the same procedure, the absorbance values A2 and A0 were determined. VC served as a positive control. The IC50 value was calculated as follows:

In vitro bacteriostatic experiment

Bacterial solution preparation

Each of the three bacterial strains was inoculated into nutrient broth and cultured for 24 h at 37 °C with 120 rpm agitation.

Determination of MIC

A modified method based on the literature22,23 was used to determine the MIC of total leaf flavonoids against S. aureus, E. coli, and C. albicans using serial dilution. Briefly, eight test tubes were prepared, each containing 3 mL of nutrient broth. To tube 1, 1 mL of the sample solution (100 mg/mL) was added and mixed thoroughly. Then, 1 mL was transferred from tube 1 to tube 2, mixed well, and this serial dilution was repeated sequentially through tube 5. Tube 6 served as a negative control (growth control), tube 7 as a positive control (penicillin), and tube 8 as a sterility control (nutrient broth only). Subsequently, 500 μL of the bacterial suspension was added to each of the tubes 1–7. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the MIC was recorded as the lowest extract concentration, showing no turbidity in the culture medium.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated three times. Data were processed and visualized using GraphPad Prism 5 and Design-Expert 10 software. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed with a 95% confidence level.

Results and analysis

Single-factor test results

Effect of extraction time on total flavonoid yield

Figure 1a shows that the total flavonoid extraction rate increased from 10 to 30 min but decreased between 30 and 50 min. The maximum yield (5.88%) was observed at 30 min. This trend could be attributed to the initial absorption of ultrasonic energy by leaf cells, which elevates intracellular temperatures and facilitates flavonoid dissolution. However, prolonged ultrasound exposure (> 30 min) likely degrades flavonoids, reducing the overall yield24. Consequently, ultrasonic extraction times of 20, 30, and 40 min were selected for response surface optimization.

Effect of extraction temperature on total flavonoid yield

Figure 1b shows that total flavonoid yield increased at 30 °C–50 °C but decreased at 50 °C–70 °C, peaking at 50 °C (5.25%). This trend suggests that within a moderate temperature range, thermal acceleration of molecular mobility enhances flavonoid dissolution from leaf tissues. However, elevated temperatures (> 50 °C) may reduce yield due to thermal degradation of flavonoid compounds and volatilization of ethanol, which decreases extraction efficiency25. Therefore, temperatures of 40 °C, 50 °C, and 60 °C were selected for subsequent response surface optimization.

Effect of solid-to-liquid ratio on total flavonoid yield

Figure 1c shows that total flavonoid yield increased progressively from solid-to-liquid ratios of 1:10–1:30 g/mL, then stabilized between 1:30 and 1:50 g/mL. The maximum yield (4.65%) occurred at 1:30 g/mL. At lower ratios, limited contact between leaf tissue and solvent restricted flavonoid dissolution, reducing yield. Higher ratios improved solvent–material contact, promoting dissolution until saturation was reached. Beyond this point, further increases in the ratio provided no significant improvement because flavonoids were fully dissolved26. Consequently, ratios of 1:20, 1:30, and 1:40 g/mL were selected for subsequent response surface optimization.

Effect of ethanol volume fraction on total flavonoid yield

Figure 1d indicates that total flavonoid yield increased from 50 to 80% ethanol concentration but decreased between 80 and 90%. The maximum yield (4.95%) was observed at 80% ethanol. At lower ethanol concentrations (< 80%), flavonoid dissolution from leaf material was incomplete. Increasing ethanol concentration improved dissolution and yield. However, above 80%, decreased solution polarity promoted dissolution of nonpolar compounds while reducing the extraction efficiency of highly polar flavonoids, consequently lowering the total yield27. Therefore, ethanol concentrations of 70%, 80%, and 90% were selected for subsequent response surface optimization.

Response surface optimization

Experimental results and analysis of the response surface

Based on the single-factor experiment results, a four-factor, three-level response surface methodology design was employed to optimize the total flavonoid extraction from leaf material. The experimental design matrix and corresponding results are presented in Table 2.

Analysis of variance and fitting of quadratic multiple regression equations

Quadratic multivariate regression analysis of the data in Table 2 was performed using Design-Expert 10 software. The regression equation is as follows:

Y = 5.5 + 0.32A − 0.15B + 0.35C + 0.19D − 0.17AB − 0.025AC − 0.13AD − 0.14BC − 0.29BD − 0.033CD − 0.37A2 − 0.33B2 − 0.44C2 − 0.50D2.

The analysis of the quadratic multivariate regression model is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3 shows that the model has an F value of 9.57 and a P value of < 0.01, indicating that it is significant. The lack-of-fit term has a P value of 0.2204, indicating that model error is not significant. A (solid-to-liquid ratio), B (extraction time), C (extraction temperature), and D (ethanol volume fraction) significantly affect the total flavonoid yield of structural leaves (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.05, respectively). The quadratic terms A2, B2, C2, and D2 are significant (P < 0.01). The order of influence of each factor is D > C > A > B. These results indicate that the model is suitable for optimizing the extraction process of total flavonoids from leaf material.

Interaction analysis

Figure 2 illustrates the interactions between factors A–D. The steepness of the response surface reflects the relative influence of each factor on total flavonoid yield from leaf material, whereas contour line density reflects the strength of factor interactions, with elliptical patterns indicating significant interactions20. Specifically, the B × D interaction significantly affected flavonoid yield (P < 0.05), whereas other factor interactions were not significant.

Verification test

Based on the response surface model analysis, the optimal extraction conditions were identified as follows: solid-to-liquid ratio, 1:34.95 g/mL; extraction time, 24.34 min; temperature, 54.71 °C; and ethanol concentration, 82.70%. Under these conditions, the predicted total flavonoid yield from leaf material was 5.75%. For practical application, the parameters were adjusted as follows: solid-to-liquid ratio, 1:35 g/mL; extraction time, 24.3 min; temperature, 54.7 °C; and ethanol concentration, 83%. Triplicate verification experiments produced an average total flavonoid content of 5.69% ± 0.04% (mean ± SD), closely matching the predicted value and confirming the model’s predictive validity.

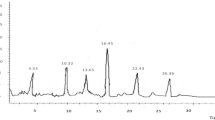

Analysis of flavonoids by LC–MS/MS

UPLC-Orbitrap-MS analysis was employed to profile the constituents of the B. papyrifera leaf extract (Fig. 3a and b). The raw data were processed using Progenesis QI software (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA), enabling the tentative identification of 101 flavonoid compounds through database comparisons (Table 4).

Flavonoids are ubiquitous plant compounds with rich and diverse biological activities, such as antioxidant28, antibacterial29, anti-inflammatory30, and antiviral actions31. Their multiple physiological functions make them widely applicable in medicine, food, and agriculture32. We preliminarily identified flavonoids including apigenin, luteolin, isovitexin, naringenin, vitexin, luteoloside, and vitexin-4’’-rhamnoside, which aligns with our earlier findings33.

In vitro antioxidant activity of total flavonoids from leaf material

Oxidative stress is a physiological condition caused by an imbalance between prooxidants and antioxidants, typically manifested as excessive production of reactive species34. Under normal circumstances, the production and scavenging of free radicals are maintained in dynamic equilibrium. Disruption of this balance leads to the accumulation of free radicals, which can damage biological molecules such as proteins, DNA, and lipid peroxides, causing diseases such as atherosclerosis35, cardiovascular disease36, diabetes37, tumors38, and cancer39. Antioxidants can effectively neutralize free radicals, preventing the onset and progression of such diseases.

Because oxidative stress is a complex process, the DPPH, hydroxyl, and ABTS assays were employed to evaluate the antioxidant activity of total flavonoids from B. papyrifera leaves.

As shown in Fig. 4a, when the mass concentration of total flavonoid extract from B. papyrifera leaves was 0.0125–1 mg/mL, the DPPH radical scavenging rate showed an overall upward trend. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50 value) of total flavonoids against DPPH free radicals was 0.072 mg/mL using software analysis. This activity was substantially higher than that of total flavonoids from Cedrus deodara pollen (0.53 mg/mL)40 but lower than that of African locust bark extract (0.0074 mg/mL)41.

As shown in Fig. 4b, when the concentration of total flavonoids from B. papyrifera leaves was 0.1875–3 mg/mL, the hydroxyl radical scavenging rate exhibited an overall increasing trend. The IC50 of total flavonoids against hydroxyl radicals was 1.53 mg/mL. Although this activity was substantially higher than that of total flavonoids from Murraya tetramera leaves (13.85 mg/mL)42, it was lower than that of total flavonoids from Moxa (0.185 mg/mL)43.

As shown in Fig. 4c, the ABTS radical scavenging rate of the total flavonoid extract from B. papyrifera leaves also demonstrated an overall increasing trend within a mass concentration of 0.1875–3 mg/mL. The IC50 of total flavonoids against ABTS radicals was 0.48 mg/mL. Although this activity was significantly higher than that of total flavonoids from Epimedium (78.259 mg/mL)44, it was lower than that of total flavonoids from dandelion (0.306 mg/mL)45. Overall, these results demonstrate that total flavonoids from B. papyrifera leaves are effective scavengers of DPPH, hydroxyl, and ABTS radicals.

Determination of the MIC of total flavonoids from leaf material

Bacterial drug resistance has emerged as a critical threat to livestock health and sustainability, making the development of novel antibacterial drugs a major research focus. However, antibiotic development is hampered by long development cycles, high costs, and significant challenges, which have led to growing interest in plant-derived bioactive compounds. Flavonoids, a major class of polyphenolic secondary metabolites, are widely distributed across the plant kingdom46. Their broad spectrum of biological activities, including anticancer47, antibacterial48, and antiviral49 properties, combined with advantages such as extensive natural sources, low tendency to induce resistance, and favorable safety profile, have made them the subject of intense research worldwide. Flavonoids exert antibacterial effects through multiple mechanisms, including cell membrane disruption, inhibition of energy metabolism, and impairment of nucleic acid synthesis50. They also enhance antibiotic sensitivity. Synergistic interactions between flavonoids and antibiotics improve treatment efficacy against drug-resistant bacteria, highlighting their potential as candidates for developing novel therapeutic agents to combat antimicrobial resistance51. Their antibacterial properties, which have been well-documented for their significant inhibitory effects52, encompass three primary modes of action: direct bactericidal effects, antibiotic synergism, and reduction of bacterial virulence53. Direct inhibition involves multiple mechanisms, including disruption of cell membrane permeability and structure, inhibition of nucleic acid and protein synthesis, suppression or eradication of biofilms, interference with energy metabolism, and inhibition of bacterial motility54,55,56.

To investigate the antimicrobial activity of total flavonoids from B. papyrifera leaves, this study examined their effects against S. aureus, E. coli, and C. albicans. The results showed that the MIC values were 25 mg/mL for both S. aureus and E. coli, and 100 mg/mL for C. albicans (Table 5). The inhibitory activity of these flavonoids against S. aureus was lower than that reported for total flavonoids from Dichondra repens57, whereas activity against E. coli was higher. Additionally, the anti-C. albicans activity was weaker than that of the total flavonoids from Bidens parviflora58. Previous research has reported that aqueous extracts of B. papyrifera leaves inhibit S. aureus and E. coli with MICs of 125 and 250 mg/mL, respectively59, indicating that total flavonoids from B. papyrifera possess significantly greater antimicrobial potency than the aqueous extract. Additionally, alcoholic extracts of B. papyrifera bark have been reported to inhibit C. albicans60. In summary, these findings indicate that total flavonoids from B. papyrifera leaves are potent antimicrobial agents.

Gutiérrez-Venegas et al.61 investigated the antibacterial activity of flavonoids such as apigenin, catechin, luteolin, morin, myricetin, naringenin, quercetin, and rutin. Their study demonstrated that these compounds inhibited Streptococcus pyogenes, Enterococcus faecalis, E. coli, and S. aureus. Specifically, apigenin was active against E. coli and S. aureus, whereas catechin inhibited S. aureus. Luteolin, naringenin, morin, quercetin, and rutin also inhibited C. albicans.

Upon bacterial contact, particularly in the presence of metal ions, many antioxidants (especially polyphenols like tea polyphenols and curcumin) are oxidized, generating large quantities of reactive oxygen species (ROS). This exogenous ROS surge overwhelms the bacterial antioxidant defense system, causing a rapid rise in intracellular ROS. Elevated ROS levels damage cellular components, including membranes, DNA, proteins, and enzymes, leading to bacterial dysfunction and death62,63,64. The strong antioxidant activity of total flavonoids from B. papyrifera leaves identified in this study provides a mechanistic basis for their antimicrobial efficacy.

Conclusion

This study investigated the extraction, antioxidant, and antibacterial properties of total flavonoids from B. papyrifera leaves and determined the following optimal extraction conditions: solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:35 g/mL, extraction time of 24.3 min, temperature of 54.7 °C, and ethanol concentration of 83%. The comprehensive UPLC-MS/MS profiling revealed a rich and diverse composition of 101 flavonoids, providing a chemical basis for the observed bioactivities. In vitro antioxidant assays revealed strong radical scavenging activity, with IC50 values of 0.072 mg/mL for DPPH, 1.53 mg/mL for hydroxyl, and 0.48 mg/mL for ABTS radicals. Antimicrobial testing revealed MIC values of 25 mg/mL against both S. aureus and E. coli and 100 mg/mL against C. albicans, confirming significant bioactivity. These findings highlight the strong potential of B. papyrifera leaf flavonoids as natural antioxidants and antimicrobial agents, with promising applications in the food industry as preservatives, in pharmaceuticals as complementary therapeutic agents, and in veterinary medicine as green feed additives to improve animal health and reduce antibiotic use. However, these findings are solely based on in vitro assays. Further in vivo studies are necessary to evaluate their bioavailability, safety, and efficacy. Future research should also focus on isolation and identification of specific flavonoid compounds, elucidation of their mechanistic studies on their bioactivities, and development of practical formulations for commercial application. Overall, this study provides a scientific basis for the valorization of B. papyrifera leaves and contributes to the sustainable utilization of plant resources in functional product development.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reason-able request.

References

Li, Y. et al. Medicinal potential of Broussonetia papyrifera: Chemical composition and biological activity analysis. Plants (Basel). 14(4), 523 (2025).

Zhao, M. et al. Hybrid Broussonetia papyrifera fermented feed can play a role through flavonoid extracts to increase milk production and milk fatty acid synthesis in dairy goats. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 794443 (2022).

Wang, G. W., Huang, B. K. & Qin, L. P. The genus Broussonetia: a review of its phytochemistry and pharmacology. Phytother. Res. 26(1), 1–10 (2012).

Chao-yan, Q. & Dai-lian, N. Research progress on chemical constituents and pharmacological effects of Broussonetia Papyrifera. World Latest Med. Inf. 19(96), 66–67 (2019).

Liga, S., Paul, C. & Péter, F. Flavonoids overview of biosynthesis, biological activity, and current extraction techniques. Plants (Basel) 12(14), 2732 (2023).

Serafini, M., Peluso, I. & Raguzzini, A. Flavonoids as anti-inflammatory agents. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 69(3), 273–288 (2010).

Wang, J. et al. Extraction and purification of total flavonoids from Zanthoxylum planispinum Var. Dintanensis leaves and effect of altitude on total flavonoids content. Sci Rep. 15(1), 7080 (2025).

Adhikary, K. et al. Phytonutrients and their neuroprotective role in brain disorders. Front. Mol. Biosci. 12, 1607330 (2025).

Saleh, S. Y., Younis, N. A., Sherif, A. H. & Gaber, H. G. The role of Moringa oleifera in enhancing fish performance and health: a comprehensive review of sustainable aquaculture applications. Vet. Res. Commun. 49(6), 308 (2025).

Lu, Q. et al. Effects of a commercial buckwheat rhizome flavonoid extract on milk production, plasma pro-oxidant and antioxidant, and the ruminal metagenome and metabolites in lactating dairy goats. J. Dairy Sci. 108, 12241–12256 (2025).

Tang, Z., Wang, Y., Huang, G. & Huang, H. Ultrasound-assisted extraction, analysis and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from the rinds of Garcinia mangostana L.. Ultrason Sonochem. 97, 106474 (2023).

Cheng, J. et al. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction of total flavonoids from Zanthoxylum bungeanum residue and their allelopathic mechanism on Microcystis aeruginosa. Sci Rep. 14(1), 13192 (2024).

Yusoff, I. M., Mat Taher, Z., Rahmat, Z. & Chua, L. S. A review of ultrasound-assisted extraction for plant bioactive compounds: Phenolics, flavonoids, thymols, saponins and proteins. Food Res Int. 157, 111268 (2022).

Wang D, Lv J, Fu Y, Shang Y, Liu J, Lyu Y, Wei M, Yu X. Optimization of Microwave-Assisted Extraction Process of Total Flavonoids from Salicornia bigelovii Torr. and Its Hepatoprotective Effect on Alcoholic Liver Injury Mice. Foods. 13(5), 647, (2024).

Li, J., Li, B., Shi, X., Yang, Y. & Song, Z. Extraction methods and sedative-hypnotic effects of total flavonoids from Ziziphus jujuba Mesocarp. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 18(9), 1272 (2025).

Molina, G. A., González-Fuentes, F., Loske, A. M., Fernández, F. & Estevez, M. Shock wave-assisted extraction of phenolic acids and flavonoids from Eysenhardtia polystachya heartwood: A novel method and its comparison with conventional methodologies. Ultrason Sonochem. 61, 104809 (2019).

Shangguan, Y. et al. Response surface methodology-optimized extraction of flavonoids from pomelo peels and isolation of naringin with antioxidant activities by Sephadex LH20 gel chromatography. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 7, 100610 (2023).

Park, N., Cho, S. D., Chang, M. S. & Kim, G. H. Optimization of the ultrasound-assisted extraction of flavonoids and the antioxidant activity of Ruby S apple peel using the response surface method. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 31(13), 1667–1678 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Ultrasound-assisted optimization extraction and biological activities analysis of flavonoids from Sanghuangporus sanghuang. Ultrason Sonochem. 117, 107326 (2025).

Yang, S., Li, X. & Zhang, H. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from Tenebrio molitor. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 28526 (2024).

Mao, B., Lu, W. & Huang, G. Ultrasound-assisted enzymatic extraction, process optimization, and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from sugarcane peel. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 5009 (2025).

Lingzhi, H. E. et al. Optimization of ultrasonic extraction process and antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effect of total flavonoids from Plolygala fallax Hems. Anim. Husb. Vet. Med. 55(03), 55–61 (2023).

Qisheng, W. et al. T studies on the extraction process, antioxidant and antibacterial activity of Gelidium amansii ethanol extract. J. Chin. Inst. Food Sci. Technol. 23(01), 171–183 (2023).

Yali, S. et al. Study on the extraction methods of Tartary buck wheat flavononoids and their content determination. Chin. Condim. 44(3), 141–145 (2019).

Wu, Y. C. et al. Natural deep eutectic solvents as new green solvents to extract anthraquinones from Rheum palmatum L. RSC Adv. 8(27), 15069–15077 (2018).

Yue, G. A. O. et al. Optimization of extraction process of polyphenols from Zanthoxylum bungeanum leaf by response surface methodology and its antioxidant activities. Food Res. Dev. 43(6), 68–74 (2022).

Han, X., Qiao, Z. & Baoqin, W. Response surface optimization of ultrasound-microwave-assisted extraction of total flavonoids and the antioxidant activity of Murraya paniculata (L.) Jack. Spec. Wild Econ. Anim. Plant Res. 45(1), 50–57 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Citrus flavonoids and their antioxidant evaluation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62(14), 3833–3854 (2022).

Manna, T. et al. Flavonoids interfere with biofilm formation by targeting diguanylate cyclases in multidrug resistant Vibrio cholerae. Sci. Rep 15(1), 39312 (2025).

Kurhaluk, N., Buyun, L., Kołodziejska, R., Kamiński, P. & Tkaczenko, H. Effect of phenolic compounds and terpenes on the flavour and functionality of plant-based foods. Nutrients 17(21), 3319 (2025).

Ma, Y., Wang, L., Lu, A. & Xue, W. Synthesis and biological activity of novel oxazinyl flavonoids as antiviral and anti-phytopathogenic fungus agents. Molecules 27(20), 6875 (2022).

Fengyu, W. A. N., Yubo, H. A. N., Lifei, W. U. & Xin, W. A. N. G. The biological activity of flavonoids and their application progress in animal production. China Feed. 17, 7–13 (2025).

Huang, X. et al. Broussonetia papyrifera ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice by modulating the TLR4/NF-κB and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. PLoS ONE 20(5), e0322710 (2025).

Jomova, K. et al. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Chronic diseases and aging. Arch Toxicol. 97(10), 2499–2574 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Comparative study on the effects of algal oil DHA calcium salt and DHA on lipid metabolism and oxidative stress in high-fat diet-induced mice. Food Funct. https://doi.org/10.1039/d5fo02090e (2025).

Xu, T. et al. Oxidative stress in cell death and cardiovascular diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 9030563 (2019).

Dong, N., Lu, X. & Qin, D. Hypoglycemic effect of enzymatically extracted Cichorium pumilum Jacq polysaccharide (CGP) on T2DM mice via PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 329(Pt 1), 147711 (2025).

Moghadam Aghajari, H. & Asle-Rousta, M. Eucalyptol alleviates lead-induced nephrotoxicity in rats by suppressing oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis, and enhancing the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-025-04831-7 (2025).

Fuchs-Tarlovsky, V. Role of antioxidants in cancer therapy. Nutrition 29(1), 15–21 (2013).

Anqi, X., Wanyu, L., Mengfan, W. & Bin, L. Optimization of extraction process of total flavonoids from Cedar Pine pollen and its antioxidant activity evaluation. Chin. Tradit. Pat. Med. 47(08), 2530–2534 (2025).

Mathisen, E., Diallo, D., Andersen, Ø. M. & Malterud, K. E. Antioxidants from the bark of Burkea africana, an African medicinal plant. Phytother Res. 16(2), 148–153 (2002).

Hui-ting, Z., Rui, C., Wen-ya, C., Ning, Z. & Li-ni, H. Optimization of extraction process of total flavonoids from Murraya Tetramera Huang by response surface methodology and study on its antioxidant activity. Chem. Eng. 39(05), 85–90 (2025).

Heng, Y. A. O., Yu-dong, D. A. N. G., Shi-bo, W. U., Meng-meng, W. A. N. G. & Bao-lan, L. I. U. Study on the optimization of extraction process and antioxidant activityof total flavonoids from moxa floss. Chem. Eng. 38(10), 95–99 (2024).

Lingzhi, W., Ping, C., Zhenhua, G. & Honglei, Z. Study on response surface optimization of ultrasonic-assistedextraction of total flavonoids from Epimedium and its antioxidant activity. Feed Res. 48(04), 92–97 (2025).

Qin-yu, S., Zhi-yuan, D. & Yu-zhong, L. Study on optimization of extraction processand antioxidant activity of total flavonoids from dandelion. Feed Res. 47(19), 91–95 (2024).

Wen, K. et al. Recent research on flavonoids and their biomedical applications. Curr. Med. Chem. 28(5), 1042–1066 (2021).

Selvakumar, P. et al. Flavonoids and other polyphenols act as epigenetic modifiers in breast cancer. Nutrients 12(3), 761 (2020).

Dias, M. C., Pinto, D. C. G. A. & Silva, A. M. S. Plant flavonoids: chemical characteristics and biological activity. Molecules 26(17), 5377 (2021).

Badshah, S. L. et al. Antiviral activities of flavonoids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 140, 111596 (2021).

Tan, Z., Deng, J., Ye, Q. & Zhang, Z. The antibacterial activity of natural-derived flavonoids. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 22(12), 1009–1019 (2022).

Song, M. et al. Plant natural flavonoids against multidrug resistant pathogens. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 8(15), e2100749 (2021).

Debalke, D., Birhan, M., Kinubeh, A. & Yayeh, M. Assessments of antibacterial effects of aqueous-ethanolic extracts of Sida rhombifolia’s aerial part. Sci. World J. 2018, 8429809 (2018).

Musial, C., Kuban-Jankowska, A. & Gorska-Ponikowska, M. Beneficial properties of green tea catechins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(5), 1744 (2020).

Liang, J., Huang, X. & Ma, G. Antimicrobial activities and mechanisms of extract and components of herbs in East Asia. RSC Adv. 12(45), 29197–29213 (2022).

Bryan, J., Redden, P. & Traba, C. The mechanism of action of Russian propolis ethanol extracts against two antibiotic-resistant biofilm-forming bacteria. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 62(2), 192–198 (2016).

Bouchelaghem, S. et al. Evaluation of total phenolic and flavonoid contents, antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of Hungarian propolis ethanolic extract against Staphylococcus aureus. Molecules 27(2), 574 (2022).

Yewen, Z., Qingmin, Z., Deqi, J., Min, W. & Guifen, L. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction technology and antibacterialactivity of total flavonoids from Gerbera piloselloides (L.) Cass. China Feed 3, 29–33 (2022).

Mingchen, C., Mengxiang, & Xin, H. The antibacterial activity of total Flavonoids in Bidensbipinnata. . Tianjin U. Tradit. Chin. Med. 37(03), 239–241 (2018).

Li Qinmei, X. et al. In vitro bacteriostatic effect of Broussonetiapapyrifera L. (Paper mulberry) waterextract combined with antibiotics on multi-drug resistant bacteria. China Feed. 9, 126–131 (2020).

Hua, K. W., Wan-Qing, K., Zheng, C., Shi-Bing, Q. & Ye-Ping, C. Study on extraction and antibacterial activity of total flavonoids from Broussonetia Papyrifera Bark. J. Anhui Univ. Chin. Med. 34(03), 93–96 (2015).

Gutiérrez-Venegas, G., Gómez-Mora, J. A., Meraz-Rodríguez, M. A., Flores-Sánchez, M. A. & Ortiz-Miranda, L. F. Effect of flavonoids on antimicrobial activity of microorganisms present in dental plaque. Heliyon. 5(12), e03013 (2019).

Ren, X., Zou, L. & Holmgren, A. Targeting bacterial antioxidant systems for antibiotics development. Curr. Med. Chem. 27(12), 1922–1939 (2020).

Ungureanu, D. et al. Novel 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl-thiazole-coumarin hybrid compounds: synthesis, in silico and in vitro evaluation of their antioxidant activity. Antioxidants (Basel). 14(6), 636 (2025).

Callistus, I. I. et al. Mechanistic insight and in-vitro validation of ampicillin/scoparone-functionalized ZnO nanoparticles as antioxidant, and antimicrobial therapeutics against antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli. Bioorg Chem. 163, 108764 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Postgraduate Education Reform and Quality Improvement Project of Henan Province (YJS2023JD68); Henan Province Science and Technology Research Project (232102310421); Zhengzhou Basic Research and Applied Basic Research Project (ZZSZX202110); Henan Provincial Key Discipline Initiative (Grant No. 2023–414), sponsored by Department of Education of Henan Province, and Henan Provincial Department of Education Funding Program for Discipline and Specialty Development in Private Regular Institutions of Higher Education(Grant No. 2022–219).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XH was involved in the entire experimental process. AJ and SL were involved in the direction of the experiments and made significant contributions to the writing of the manuscript. CY, HZ, and CD were involved in analyzing and interpreting the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, X., Jia, A., Liu, S. et al. Extraction process and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of total flavonoids from Broussonetia papyrifera leaves. Sci Rep 16, 442 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30074-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30074-6