Abstract

Evaluating the influence that alterations in land use/land cover (LULC) have on habitat quality and landscape patterns is essential to promote regional sustainable development. This research simulates the LULC trends of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region in 2035 and 2050 under three scenarios and subsequently evaluates changes in habitat quality using the FLUS-InVEST model. Additionally, Geodetector is employed to pinpoint the principal causes influencing fluctuations in habitat quality. The following results are obtained: (1) During 2000–2023, substantial alterations occurred in LULC, with habitat quality declining by 0.041. The transition to ecological land improved habitat quality, while the transformation of cultivated land to construction land posed a severe threat to habitat quality. (2) Under Business as Usual (BAU) scenario, the average habitat quality is projected to be 0.341 in 2035 and 0.337 in 2050, with degraded areas becoming increasingly fragmented and continuously expanding. Under Cultivated Land Priority (CLP) scenario, the average habitat quality decreases by 0.003 from 2023 to 2050. This scenario slows urban expansion, and the intensity of habitat degradation is reduced compared with the BAU scenario. Conversely, Ecological Priority (EP) scenario shows an increase in habitat quality with lower landscape fragmentation. (3) DEM is the predominant determinant of habitat quality spatial heterogeneity, with an explanatory power of 0.324. Notably, the interaction between DEM and NDVI demonstrates the strongest explanatory power (q = 0.497). These findings provide a reliable basis for scientifically formulating future LULC policies and accurately implementing ecological protection strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urbanization is a universal phenomenon in global modernization and a significant indicator for measuring social progress and the degree of economic development1. It is reported that the proportion of urban residents is projected to reach 68% by 2050, an increase of 13% compared with 20182. Such a significant growth trend means that more regions around the world will experience rapid urbanization in the future. China’s urbanization process entered a rapid development phase after the reform and opening-up. Compared with 1978, China’s urbanization rate increased by 45.99% in 20203, which would result in land encroachment, substantial alterations to land use/land cover (LULC)4, and a significant decline in eco-environment quality5. Meanwhile, human activities associated with urbanization have led to notable ecosystem degradation6, thus affecting the fundamental ecological processes and the resilience of ecosystems to disturbances4,7. Therefore, in the context of urbanization, the fragmentation and complexity of landscape patterns4, environmental pollution8 and urban heat island9,10 caused by human activities will increase the pressure on regional ecological balance maintenance and habitat quality preservation, which has become a common problem faced by rapid economic development. How to promote urbanization while protecting the ecological environment and achieving coordinated development is a challenge faced by countries around the world.

Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs (InVEST) model is extensively applied in the ecosystem services domain. Primarily designed for quantitative and visual assessment, it integrates with geographic information system (GIS) technology to assess ecosystem service functions11,12. The main application area of the InVEST model covers many major river basins13,14,15, important urban agglomerations16,17, ecologically fragile areas18, islands19, and nature protected areas20,21. Its application contents mainly involve habitat quality22,23, soil conservation24, carbon storage25,26, water conservation27, and so on. Chen et al.23 applied InVEST model to evaluate coastal wetlands, discovering that the habitat quality of coastal areas in Jiangsu Province dropped to the lowest level during 2011–2015 due to wastewater discharge. The study by He et al.27 clarified the spatiotemporal patterns of soil and water conservation in the northern Qinling Mountains, which showed a declining trend between 1980 and 2000, followed by an upward trend. A study has shown that publications applying the InVEST model focus on habitat quality (29.5%), annual water yield (22.3%), and carbon storage (19.9%), which can be considered to reflect trends in future research28.

Habitat quality denotes the capacity of ecosystems to furnish appropriate conditions for the survival and reproduction of organisms, and the maintenance of their ecological functions. It serves as an essential criterion for evaluating ecosystem vitality and biodiversity29. Landscape pattern constitutes a direct and effective manifestation of changes in land types, playing an essential role in sustaining regional growth and offering insights into the comprehensive health of an ecosystem30. A spatial association exists between habitat quality and the characteristics of landscape patterns31. Wang et al.2 also found that the type, distribution, and fragmentation of habitat played important roles in habitat quality. Against the backdrop of ecological degradation trends, it is essential to forecast habitat quality and landscape patterns under different scenarios32. Recently, more and more domestic and foreign researchers have applied various models to fields such as LULC change simulation and landscape dynamics analysis. Combined with FLUS model33, CA model34, Markov model21, and CLUE-S model35, InVEST model can systematically predict and evaluate habitat quality in multiple scenarios. However, these models exhibit inherent limitations. CA model insufficiently considers the influence of several macro factors on the simulation results and exhibits strong scale dependence36; the Markov model only focuses on the probability of a specific LULC type being converted to other types, but fails to account for the spatial changes; and the CLUE-S model exhibits a strong reliance on data and shows poor adaptability to extreme scenarios33. In contrast to traditional models, the FLUS model uniquely combines macro-level forecasting and micro-scale simulation, thereby contributing to evaluating the habitat quality under future LULC scenarios37,38,39. By integrating spatially explicit algorithms and socioeconomic drivers, this approach can capture the complex feedback mechanisms between human activities and LULC, thus providing a comprehensive framework for evaluating how LULC transitions influence biodiversity conservation and ecosystem health.

Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration serves as the third economic growth pole and also China’s “capital economic circle”. In recent years, its rapid development has led to the destruction of the habitat pattern of the local ecosystem, weakened ecosystem service functions, and posed a serious threat to biodiversity. Therefore, this research aims primarily to (1) examine the variations in habitat quality and landscape pattern from 2000 to 2023; (2) conduct simulations of LULC changes under various scenarios for the years 2035 and 2050; and (3) explore the habitat quality changes along with the main driving factors. These results are conducive to the balanced development between regional social economy and ecological protection.

Data and methods

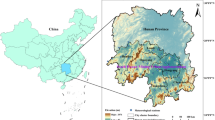

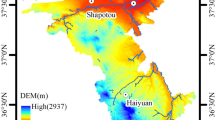

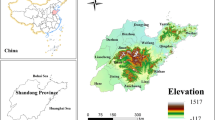

Study area

Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region is situated in northern China (Fig. 1), with an area of 21.8 × 104 km2, which is around 2.3% of China’s territory. It is the political and economic center, with 109.7 million people by the end of 2022. In 2024, the gross domestic product (GDP) reached 11,539.4 billion yuan, representing a 5.2% growth from the previous year. Along with the rapid development of the economic level, the resource and environmental problems have become more and more prominent40, mainly including air pollution, water resource shortage and ecological vulnerability41,42,43. Recently, the built-up area of this region has expanded rapidly, totaling 4709.6 km2 in 2018, which accounts for 8.1% of the national built-up area31. To promote regional coordinated development, an efficient and dense rail transportation network has also been gradually built. These dense and diffuse land use patterns have seriously damaged the habitat structure of the ecosystems, endangering habitat quality and biodiversity.

Data sources

The indicators were chosen for normalization, including digital elevation model (DEM), slope, aspect, average annual precipitation (PRE), average annual temperature (TEM), normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), population (POP), GDP, distance to major transportation routes (roads and railways), and distances from city, county, and town centers (as displayed in Supplementary Table 1). Specifically, six natural environment factors and eight socio-economic factors were utilized to model future LULC patterns. The LULC types include cultivated land (CuL), forest land (FL), grassland (GL), water area (WA), construction land (CoL), and unused land (UL), and we used high-resolution remote sensing images to correct blurred boundaries. Spatial and statistical processing of these datasets was conducted using ArcGIS 10.8 software, incorporating functionalities such as Euclidean distance computation, slope and aspect analysis, image segmentation, masking operations, and reclassification. All spatial data were normalized to Krasovsky_1940_Albers projection system, and a resolution of 250 m was achieved through resampling techniques.

Research method

FLUS model was utilized to simulate LULC trends for 2035 and 2050. This simulation was carried out across three distinct scenarios. An examination of LULC transfer matrix was conducted for Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region spanning 2000–2050. Additionally, habitat quality and landscape pattern were analyzed using InVEST and Fragstats models, respectively. Furthermore, Geodetector analysis was integrated to establish the determinants of alterations in habitat quality. The methodological framework of FLUS-InVEST is presented in Fig. 2.

Multi-scenario predictive analysis

Three scenarios were designed, including Business as Usual (BAU), Cultivated Land Priority (CLP), and Ecological Priority (EP) scenarios, which could cover different development paths, achieve comprehensive and comparable predictions, and provide multiple references for decision-making. We planned to select the long-range plan target (2035) and 2050 as the forecast periods. The BAU scenario refers to a situation where LULC patterns develop in accordance with historical natural trends, driving factors such as population growth and economic development maintain their current rates of change, and no additional policy interventions are implemented. It provides a critical reference for evaluating the effectiveness of policy-oriented scenarios, thereby highlighting the potential consequences of unregulated development (e.g., fragmented urban sprawl, inefficient agricultural land conversion). The CLP scenario aims to protect cultivated land and basic farmland, strictly restricts all types of cultivated land occupation, and enables in-depth analysis of regional cultivated land change trends under policy intervention. This scenario incorporates strict regulatory mechanisms, such as cultivated land red line protection and special protection of permanent basic farmland, reflecting the urgent needs for food security and sustainable agricultural development. In contrast, EP scenario focuses on ecological protection goals, strengthens ecological constraints, strictly restricts the conversion of ecologically sensitive land types (especially forests, water bodies, and wetland ecosystems) and places environmental sustainability at the forefront, and aims to maintain ecological integrity, enhance ecosystem service functions, and protect biodiversity.

FLUS model calculates the suitability probability based on artificial neural network (ANN). Subsequently, the comprehensive probability is derived through roulette selection, with land use simulation results generated in the final step. The molar neighborhood of 3 × 3 is used as the neighborhood range. With reference to the relevant research33, the neighborhood influence factor parameters of various classes are finally determined. Three different conversion cost matrices were designed, as displayed in Supplementary Table 2. By applying LULC data of 2005, the LULC distribution pattern in 2020 was simulated and subsequently validated against the actual LULC of 2020, showing an overall accuracy of 83.32%.

Landscape pattern analysis

The structural stability of an ecosystem primarily depends on landscape heterogeneity and landscape connectivity44. The higher the landscape heterogeneity and connectivity, the more complex the habitat becomes, leading to greater ecosystem stability. Therefore, we utilized the Fragstats 4.2 model to analyze landscape pattern characteristics at both class and landscape levels, including number of patches (NP), patch density (PD), patch cohesion index (COHESION), largest patch index (LPI), mean patch area (Area_Mn), contagion (CONTAG), Shannon’s diversity index (SHDI), Shannon’s evenness index (SHEI), and landscape division index (DIVISION) (as shown in Supplementary Table 3).

Habitat quality analysis

Only when the survival resources and conditions are suitable can biodiversity be guaranteed. Habitat quality (Qxj) is calculated by the following formulas:

Equations (1) (2) and (3) where Hj is the habitat suitability of habitat type j; Dxj represents degree of habitat quality degradation of unit x in type j; k is usually 1/2 of maximum Dxj; z is generally 2.5; y is raster element in the stress factor r; ry represents stress factor in land use type y; irxy represents the degree of influence of r in y on habitat x; βx and Sjr reprsent the reachability of threat source to x and the sensitivity of ground class y to r, respectively. dxy and dr max are the linear distance between x (habitat) and y (stress factor) and the maximum range of r. Taking into account the actual conditions and incorporating relevant literature33, the parameters required for habitat quality analysis are displayed in Tables 1 and 2.

The contribution rate of habitat is a quantifiable indicator that serves the purpose of systematically measuring the amount to which land-type conversions affect habitat quality by assessing changes induced by different LULC transitions. The formula is as follows:

Equation (4) Hi and Hj represent habitat quality before and after change, respectively; Si is the changing land area; St refers to the total area.

Driving factors analysis

Geodetector utilizes statistical principles to reveal the driving forces through four modules, thus analyzing spatial stratified heterogeneity45,46. We employed factor detector and interaction detector with habitat quality as a dependent variable, and natural factors and socioeconomic factors as independent variables, including DEM (X1), TEM (X2), PRE (X3), NDVI (X4), net primary productivity (NPP) (X5), potential evapotranspiration (PET) (X6), soil type (X7), POP (X8), GDP (X9), nighttime light index (X10), distance from the town center (X11), and distance from the main road (X12). The research aimed to explore the explanatory power of each driving component on habitat quality, together with the extent of interaction. The explanatory power is contingent upon q, which follows the formula proposed by Li et al.15. The value of q approaches 1, signifying that the impact of this variable on habitat quality is more pronounced.

Results and discussion

Analysis and prediction of LULC

LULC from 2000 to 2023 and multi-scenario simulation for future LULC

Since 2000, LULC of study region has been in a dynamic state of change, but the structure of LULC types has remained mostly unchanged. Cultivated land, forest land, and grassland remained the primary LULC types, constituting the main ecological space of the region (Fig. 3a). By 2023, the coverage of cultivated land reached 43.9%, mainly distributed in the southern and eastern parts of Hebei Province. 21.1% of land was covered by forest, the majority of which was situated in Yanshan and Taihang mountain ranges, in addition to the Bashang region in Zhangjiakou. Grassland coverage amounted to 33,607.6 km2, predominantly found in Chengde, Zhangjiakou, and Baoding. The area of cultivated land was continuously declining, with 94,866.1 km2 in 2023, representing a reduction of 13.2% compared to 2000. Similarly, the area of grassland has also consistently declined, showing a decrease of 4.8% since 2000. By contrast, forest area has shown an increasing trend, with a total expansion of 846.3 km2. The total increase in construction land area was 14,316.7 km2, with the fastest growth rate occurring between 2005 and 2010, at 35.2%. The water area experienced a continuous decline during 2000–2015, followed by a steady increase thereafter, with an overall growth of 1862.5 km2. The growth rate peaked at 26.3% during the period from 2015 to 2020 (Fig. 3b).

FLUS model was employed to make projections regarding LULC patterns for 2035 and 2050 (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1). Under BAU scenario, a notable growth occurs in construction land, frequently encroaching upon neighboring cultivated land and forest land, which is bound to cause substantial damage to production and ecological spaces. In contrast, CLP scenario’s enforcement of stringent cultivated land protection policies leads to a larger proportion of cultivated land relative to BAU and EP scenarios, underscoring the significance of balancing LULC for the maintenance of food security. Ecological landscapes exhibit notable differences across the various scenarios, particularly in the EP scenario, showing a gradual increase in grassland coverage over time (as shown in Supplementary Table 4), which can enhance the utilization rate of ecological land and generate greater ecological benefits. Across all scenarios, grasslands consistently serve as critical transitional zones, underscoring their multifunctional significance in land use planning. Thus, implementing appropriate grassland management strategies is imperative to facilitate sustainable transitions among diverse land use types while safeguarding ecological integrity and socioeconomic resilience.

LULC change analysis during 2000–2050

During 2000–2023, the area without LULC change accounted for approximately 82.5% of the region (as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 2). The construction land area experienced a substantial increase, primarily originating from cultivated land conversion, and was evenly spread between the central and southern regions. Water area increased by 1862.5 km2 during 2000–2023, mainly distributed in the coastal areas of Tianjin, Tangshan, and Cangzhou (as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3). To be specific, between 2000 and 2005, 1307.1 km2 of cultivated land was converted to construction land, while a total of 132.1 km2 of forest and grassland were transformed into construction land. Between 2005 and 2010, notable mutual conversions occurred among cultivated land, forest land, and construction land. Forest was converted to cultivated land, reaching 610.6 km2. By contrast, the areas of cultivated land converted into forest and construction land were 1017.7 km2 and 8175.0 km2, respectively. Concurrently, 747.0 km2 of water area was transformed to construction land, leading to a rapid expansion to 26,178.2 km2. This phenomenon was closely linked to the rapid advancement of urbanization and economic growth. LULC changes exhibited a phase of stability during the period from 2010 to 2015. However, the total area of cultivated land reduced by 2622.3 km2, with 1104.6 and 1140.3 km2 converted to forest and grassland during 2015–2020, respectively, reflecting the important ecological civilization construction initiatives. During 2020–2023, construction land expanded by 4086.5 km2, predominantly converted from cultivated land, aligning with regional coordinated development strategies. It is necessary to fully consider the demand for construction land driven by urbanization and economic development, reasonably determine the scope and speed of construction land expansion, and avoid excessive occupation of cultivated land and ecological land. In future land use planning, farmland protection should be given a more prominent position. The red line for farmland protection should be strictly delineated, and efforts should be made to strengthen the protection of farmland quality and the control of farmland quantity. Moreover, the speed and direction of LULC changes vary in different time periods. Therefore, it is essential to strengthen the dynamic monitoring and assessment of LULC changes, and promptly revise and improve land use plans.

The alterations in LULC type areas and proportions under various scenarios relative to 2023 are shown in Fig. 4a-c. Under BAU scenario, cultivated land area drops by 230.0 km2 (0.2%) in 2035, alongside reductions in grassland and water areas. In contrast, both forest and construction land are anticipated to expand by 648.6 and 1221.4 km2, respectively. New construction land expansion is primarily concentrated near Tianjin Binhai New Area. Under CLP scenario, the cultivated land area is anticipated to expand by 5526.8 km2. Compared with BAU scenario, this scenario significantly changes the conversion pattern of LULC types through optimizing land use planning and policy regulation, which effectively curbs the disorderly loss of cultivated land, and avoids the problem of compressed grain production space caused by blind afforestation or urban expansion. In addition, it improves the feasibility of transforming forest land into cultivated land. These results show that under CLP scenario, 1962.7 km2 of forest is successfully converted to cultivated land, which facilitates the protection of food security and promotes optimal use of land resources alongside balanced development of ecosystems. Under EP scenario, forest land and grassland areas will expand by 649.8 and 502.1 km2, respectively, mostly converted from cultivated land. Construction land expands moderately, indicating effective implementation of ecological conservation policies.

According to Fig. 4d-f, it is projected that the land use structure will not undergo significant changes by 2050. Cultivated land area only increases under the CLP scenario, by 6355.7 km2 (6.7%) (Fig. 4g-h), while it decreases under the other two scenarios. Forest land area shows an upward trend across all three scenarios, whereas water area declines in each scenario. Under EP scenario, forest land and grassland areas expand by approximately 1151.5 km2 and 1841.6 km2, respectively, primarily in the western and northern mountainous regions, and Bashang Plateau. Construction land undergoes substantial growth under BAU scenario, increasing by 16.0% compared to that in 2023.

Under the BAU scenario, the significant expansion of construction land will lead to severe habitat fragmentation and loss, thereby resulting in a decline in species richness. The decrease in water area may increase the risks of water resource shortages and pollution. The shrinkage of grasslands can reduce the capacity for soil erosion control and carbon sequestration, exacerbating the impacts of land degradation and climate change. Although the area of forest land expands, unregulated afforestation may homogenize plant communities and reduce habitat heterogeneity. The CLP scenario avoids blind afforestation and unordered urban expansion, protects contiguous agricultural landscapes, and thus ensures the survival of farmland organisms. This scenario prioritizes food production while also protecting soil fertility and water cycle regulation capabilities, ensuring agricultural sustainability. Under the EP scenario, the increase in forest and grassland areas has significantly enhanced ecosystem service functions, including carbon sequestration, climate regulation, and soil conservation. In addition, contiguous natural habitats are also conducive to species migration, population recovery, and gene exchange.

Changes in landscape patterns

The temporal variations in class-level landscape metrics related to cultivated land are shown in Fig. 5a. Between 2000 and 2015, the Area_Mn showed downward trends, revealing intensified fragmentation of cultivated land through divergent spatial configuration patterns. The highest LPI was exhibited in cultivated land, which also signified that cultivated land was the primary LULC type. The NP value in CLP scenario is lower than that in BAU and EP scenarios, suggesting that the cultivated land protection policy reduces the fragmentation degree. Meanwhile, the fragmentation under the CLP scenario weakens over time, contrary to the BAU and EP scenarios. The class-level landscape metrics for forest land and grassland are illustrated in Fig. 5b-c. From 2023 to 2035, the NP value for forests significantly decreases, while Area_Mn and COHESION increase, indicating a reduction in forest fragmentation. The NP value for grassland under EP scenario is lower than that in BAU and CLP scenarios, which implies that the implementation of ecological protection policy decreases grassland fragmentation and may enhance inter-species communication and improve ecosystem stability. Figure 5d displays the temporal variations in landscape metrics of construction land. Between 2023 and 2035, the NP value shows a significant decrease, while the COHESION and Area_Mn values exhibit opposing trends, suggesting a slight reduction in fragmentation after 2023, and a higher fragmentation degree of construction land under the CLP scenario.

From a landscape perspective, NP and PD decreased from 2000 to 2005, while the Area_Mn value increased, indicating a reduction in landscape fragmentation during this period. However, from 2005 to 2023, the upward trends in NP and PD, as well as the downward trend of Area_Mn all reflected an increase in landscape fragmentation. There is a significant negative correlation between the degree of landscape fragmentation and the ecosystem service value47, and the intensification of fragmentation will directly lead to a decline in regional plant diversity and soil microbial diversity48. Goncalves-Souza et al.49 also found that habitat fragmentation typically led to a reduction in biodiversity at the patch scale. However, in cases where habitat loss is minimal, moderate fragmentation is beneficial for species with colonization advantages to survive in smaller patches, thereby increasing biodiversity50. Moreover, recent studies have shown that habitat fragmentation exerts a dual impact on ecosystem resilience, and the direction and intensity of this impact exhibit significant differences among different biomes51. Meanwhile, forest fragmentation has a distinct threshold effect on ecological resilience; beyond the threshold, ecosystem resilience declines significantly52. Over the 2000–2023 period, the declining CONTAG suggested that the landscape formed multi-type dense patterns with reduced spatial aggregation. The values of SHDI and SHEI increased, demonstrating enhanced land use diversity, more uniform landscape distribution, and improved resistance to disturbances (Table 3). From the spatial pattern of landscape separation degree (as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 4), during the period from 2000 to 2023, the peak value of landscape separation degree demonstrated an increase followed by a decline. The northern region showed significant fragmentation, in contrast to urban areas where human activities are frequent, which showed a low fragmentation degree. An increasing fragmentation degree was exhibited in the southern region, comprising roughly 52% of the overall area. This was mainly because of the vigorous promotion of economic development, which ignored the landscape connectivity function, resulting in landscape fragmentation. Under the CLP scenario, NP, PD, and CONTAG are higher than those in the other two scenarios, but the reverse trend is noted for the other metrics, which indicates that the fragmentation degree is the highest under CLP scenario, and the lowest under EP scenario. Comparisons between 2035 and 2050 reveal no significant changes in metrics under the same scenario, which indicates that the landscape pattern will remain relatively stable in the coming period. However, it is still necessary to continuously monitor potential influencing factors to foster the sustainable growth of the ecological environment.

Effects of LULC change on habitat quality

Habitat quality grades were divided into Ⅰ (0–0.1), Ⅱ (0.1–0.3), Ⅲ (0.3–0.7), Ⅳ (0.7–0.8), and Ⅴ (0.8–1.0) (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5). According to this classification criterion, the distribution of habitat quality categories and average values from 2000 to 2023 were obtained, as shown in Table 4. Between 2000 and 2023, the average habitat quality exhibited a persistent declining trend (from 0.387 to 0.341) until 2020, after which it began to recover, increasing to 0.346. The highest value was observed in 2000 at 0.387, a peak that primarily reflected the residual integrity of natural habitats before the accelerated expansion of anthropogenic land uses in subsequent decades. Notably, the overall habitat quality remained at a relatively low level, likely constrained by existing pressures such as fragmented agricultural expansion, minor urban encroachment, and localized ecosystem degradation. Although the areas of different habitat grades continued to fluctuate, the relative proportions of these categories remained largely stable. The proportion of Grade Ⅰ continued to increase, while the proportion of Grade Ⅴ continuously declined from 2000 to 2020, especially during 2005–2010. A reversal emerged only in 2023, when the proportion of Grade Ⅴ areas exhibited an increasing trend.

Grade Ⅰ areas were relatively concentrated, mainly distributed in regions with higher levels of urbanization. The largest area was occupied by Grade Ⅱ, which highly overlapped with regions of frequent human activities such as farmland and construction land, indicating significant human impact and relatively severe damage to the ecological environment integrity. Areas with Grade Ⅲ and Ⅳ habitat quality were more dispersed, with surface vegetation mainly consisting of forests and grassland. High-value habitat quality areas (Grade V) were concentrated in mountainous regions, showing a high degree of overlap with high DEM values, suggesting minimal human impact and vegetation coverage dominated by forest land.

The habitat quality changes are displayed in Fig. 6. To be specific, there were 31,172.2 km2 of areas with improved habitat quality, 76,084.9 km2 with unchanged quality, and 108,426.2 km2 with degraded habitat quality during 2000–2010, indicating an overall trend of degradation in habitat quality during this period. Between 2010 and 2023, the areas with improved habitat quality expanded by 27,201.1 km2 compared to the 2000–2010 period. Overall, the habitat quality in 2023 was still worse than that in 2000.

Under BAU scenario, the decreased forest and grassland areas coupled with the expansion of construction land, accelerate habitat quality degradation, leading to significant ecological and environmental challenges. The average habitat quality is projected to be 0.341 in 2035 and 0.337 in 2050. From 2023 to 2050, the average habitat quality decreases by 0.009, with degraded areas becoming increasingly fragmented and continuously expanding. By 2050, degraded areas are expected to reach 30,192.4 km2, accounting for 14.0% of the total area. Meanwhile, regions maintaining stable or improved habitat quality show a contracting trend. The CLP scenario slows urban expansion, with average habitat quality values projected at 0.345 in 2035 and 0.343 in 2050. From 2023 to 2050, the average habitat quality decreases by 0.003, indicating weakened degradation intensity. Compared to the BAU scenario, areas with habitat quality improvement expand, reaching 21,520.3 km2 by 2050, which implies that strict prohibitions on occupying basic cultivated land and maximal restrictions on existing cultivated land conversion contribute positively to habitat quality improvement. Under EP scenario, average habitat quality is projected to be 0.343 in 2035 and 0.345 in 2050, showing subtle changes from 2023 to 2050. Compared to 2035, areas with improved habitat quality in 2050 increase by 932.0 km2, demonstrating that the restoration of cultivated land to forests and grasslands on barren hills effectively promotes environmental recovery.

Human activities significantly influence LULC change through multiple channels, including urban expansion, intensive agricultural development, industrial construction, and natural resource extraction. Conversely, the dynamic changes in LULC also act back on human systems through complex feedback mechanisms22. For instance, the sharp reduction of forests leads to a decline in carbon sequestration capacity, exacerbating climate warming; the degradation of wetlands results in the loss of hydrological regulation functions, increasing the risk of floods; the degradation of cultivated land threatens food security; and the reduction of ecological spaces caused by urban expansion directly affects the quality of human living environments. Changes in construction land, unused land, and cultivated land are the primary determinants influencing habitat quality53.

As displayed in Fig. 7, the transition of cultivated land to ecological land types contributed positively to habitat quality. This process reduced the damage and pollution caused by agricultural activities to land and water, thus increasing forest coverage and biodiversity. Additionally, the conversion of cultivated land to grassland mitigated the degradation of grassland caused by overgrazing and human activities. By contrast, the transformation of ecological land to alternative LULC types exerted a detrimental influence on the overall environmental balance. Notably, the conversion of cultivated land to construction land emerged as the most significant factor impeding habitat quality improvement, with a contribution coefficient of -0.8453%. This notable decline could be attributed to multiple intertwined factors, including accelerated land degradation, heightened soil erosion, and escalating tensions between human activities and land resource utilization. These findings were in line with Wu et al.54, which similarly emphasized the adverse ecological consequences of such land use shifts.

The expansion in construction land during this period was not an isolated phenomenon but rather a complex outcome shaped by various driving forces. Socio-economic development initiatives, rapid population growth, the ongoing acceleration of urbanization processes, and the implementation of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei coordinated development strategy collectively propelled this expansion. However, this rapid transformation came at a cost, as it posed significant challenges to regional sustainable development goals and exerted far-reaching impacts on the local ecological environment. Under EP scenario, habitat quality improved, but inhibited the development of urban production and living spaces. These findings were largely consistent with research conclusions on regions such as Gansu-Qinghai contiguous region and the Ebinur Lake Basin22,33. These effects underscore the necessity of adopting more balanced and sustainable LULC policies to mitigate potential negative consequences.

Analysis of driving factors of habitat quality

This study employed a multi-scenario simulation analysis approach to model the anticipated LULC patterns for 2035 and 2050, and subsequently investigated the evolutionary features of regional habitat quality under various scenarios from a spatial heterogeneity perspective. The simulation results demonstrate that the EP scenario can significantly enhance regional habitat quality indices, with its spatial optimization effects being particularly pronounced in the Yanshan-Taihang Mountain Ecological Barrier Zone. The research results hold important reference value for delineating ecological protection red lines and establishing cross-administrative regional ecological compensation mechanisms. However, it is important to recognize that the factors influencing habitat quality changes are complex and multifaceted55.

The contribution rates of driving factors to habitat quality were obtained by factor detection (Table 5). The main driving factors with higher explanatory power (q value) for habitat quality were DEM, nighttime light index, TEM, NPP, POP, NDVI, distance from town center, and PRE. This indicated that DEM was the primary influencing factor for habitat quality, with an explanatory power of 0.324. Higher-altitude areas with less human activity demonstrated better habitat quality, which was consistent with the research conclusions of Wang et al.56 and Xie et al.57. Topography could affect habitat quality through multiple pathways: (1) altitude directly determined the vertical differentiation of hydrothermal conditions, and environmental characteristics such as low temperature and strong ultraviolet radiation in high-altitude areas limited the invasion of non-native species and maintained the ecosystem originality; (2) slope and aspect indirectly regulated the composition and distribution of vegetation communities by changing surface runoff and soil development processes.

The second dominant factor was the nighttime light index, with an explanatory power of 0.283. To some extent, construction lands with higher nighttime light index typically showed poorer habitat quality. Areas with high light index values typically correspond to highly urbanized built-up areas, leading to severe fragmentation of natural habitats. These results were in line with the pattern that “the faster the urbanization process, the more pronounced habitat quality degradation”58. The rapid expansion of construction land area has become the main factor causing habitat quality degradation16. Therefore, scientific planning of construction land area is crucial for ensuring habitat quality in this region.

The interplay of multiple influences on alterations in habitat quality was examined by interaction detection (Fig. 8). These results indicated that the interaction of any two factors had a more substantial impact on habitat quality changes than individual factors alone. This phenomenon fully reflected the complexity of habitat quality change processes. Changes in each factor were constrained or promoted by other factors, collectively forming a complex network that jointly determined the dynamic changes in habitat quality.

Most interactions exhibited EB-type relationships, while some showed EN-type indicators. The overall interaction detection outcomes revealed that habitat quality changes were influenced by multiple indicators, highlighting the complexity and heterogeneity of these dynamics. The combined effect of DEM and NDVI had the most pronounced influence on habitat quality, with an explanatory power of 0.497, underscoring the crucial role of topographical features and vegetation conditions in shaping habitat quality, which was consistent with Li et al.16. Previous studies have also shown the correlation between fractional vegetation coverage and terrain as well as elevation59,60. Topographic features not only directly affected the physical structure of habitats but also indirectly influenced the growth and distribution of vegetation by affecting hydrothermal conditions, soil types, and other factors. As an important component of habitats, the vegetation condition not only provided food and habitats for organisms but also played a crucial role in soil conservation and climate regulation. The interaction between these two elements jointly determines the suitability and quality of habitats. In the future, planning schemes that are differentiated and ecological should be formulated based on the spatial differentiation characteristics of natural factors such as DEM and NDVI. In addition, attention should be paid to the key role of natural factors such as temperature and precipitation in vegetation restoration61,62. In contrast, the interaction between PET and GDP showed the least influential effect, explaining only 13.7% of the variation, indicating that while economic and hydrological factors played a role, their combined influence on habitat quality was relatively minor compared to other interacting variables.

Impact of policy and macroeconomics on habitat quality

Between 2000 and 2023, habitat quality of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region was also markedly influenced by the policy interventions and economic development. The implementation of key national strategies, particularly the coordinated development plan for Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region initiated in 2014, has driven substantial ecological restoration efforts, including afforestation projects and the establishment of ecological conservation redlines. These policies have enhanced the habitat quality in designated protected areas. However, rapid urbanization and industrial expansion, fueled by regional economic growth, have simultaneously exerted pressure on natural ecosystems, leading to habitat fragmentation in peri-urban zones. The introduction of market-based environmental mechanisms, such as cross-regional ecological compensation policies since 2018, has created new financial incentives for habitat protection. Nevertheless, economic development, as both a driver of environmental degradation and a source of funding for ecological restoration, has led to a complex spatiotemporal pattern of regional habitat quality changes, which requires a more comprehensive policy approach to balance conservation and development objectives.

Advantages and limitations of this research

The InVEST model can visually demonstrate the spatial variations in ecosystem services and has been widely applied in assessing habitat quality23 , water conservation27, and carbon storage26. Furthermore, when coupled with the FLUS model, it supports scenario simulations based on different management strategies (e.g., BAU, CLP and EP scenarios)63. Compared to other models, the FLUS model shows higher accuracy in LULC simulation and effectively addresses precision challenges in large-scale regional simulations64,65. We analyzed and forecasted the responses of habitat quality and landscape pattern to LULC changes in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region between 2000 and 2050 in this study, offering valuable insights for regional planning and habitat quality enhancement. However, some limitations also existed. The potential errors at the data level have not been fully considered. For example, the applicability of grid resolution to the spatial scale of this study area has not been fully evaluated. The uncertainty in LULC type prediction stems from multiple aspects, such as the selection of key driving factors, model parameter settings, deviations in socioeconomic scenarios, and uncertainties in policy interventions. The habitat quality module primarily considered anthropogenic threat factors, but partially neglected natural influences such as internal threats from natural predators and population competition. Additionally, the correlation and connection between habitat quality grades and environmental indicators are still unclear. In the future, it is necessary to fully evaluate the reliability of prediction results through multi-scenario simulation, parameter sensitivity analysis, and uncertainty quantification. What’s more, future research should concentrate on enriching and improving the indicator system construction, and clarifying the actual conditions corresponding to different habitat quality grades, so as to provide a more robust scientific basis for planning and decision-making.

Conclusions

Substantial alterations have transpired in the LULC patterns and habitat quality of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Between 2000 and 2023, cultivated land experienced significant loss, primarily being converted into ecological land types and construction land. Construction land area expanded by a total of 14,316.7 km2, indicating that the accelerating urbanization process led to increasingly significant conflicts between the growing demand for construction land and the preservation of natural land. In the future, strict restrictions should be imposed on the unordered conversion of cultivated land to construction land, farmland and ecological protection red lines should be delimited, and ecological compensation mechanisms as well as incentive policies for ecological restoration should be implemented. From a landscape perspective, the degree of landscape fragmentation decreased from 2000 to 2005, but it intensified from 2005 to 2023. Therefore, it is highly necessary to construct ecological corridors by means of vegetation restoration, water system connectivity, and other measures to enhance landscape connectivity. A decrease in habitat quality from 0.387 to 0.346 occurred in the period of 2000–2023. Specifically, it decreased during 2000–2015 but improved from 2015 to 2023. The conversion of cultivated land to ecological land, alongside the shift of construction land to other LULC types, exerted a positive effect on improving habitat quality. Conversely, the conversion of cultivated land to construction land constituted the primary threat to habitat quality, with a contribution rate of -0.8453%. By 2035 and 2050, the values of average habitat quality under EP scenario are projected to be 0.343 and 0.345, respectively, higher than those under BAU and CLP scenarios. Moreover, EP scenario shows lower values of NP and PD, indicating lower landscape fragmentation and significant improvement effects. Geodetector is employed to pinpoint the principal causes influencing fluctuations in habitat quality. DEM and nighttime light index are the main factors determining the habitat quality spatial heterogeneity, and the nonlinear interaction between DEM and NDVI demonstrates the strongest explanatory power. Therefore, the ecological priority strategy and zoned regulation constitute the key path to achieving high-quality development. These findings can provide a basis for scientifically formulating future LULC policies and accurately implementing ecological protection strategies.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Li, J. X. et al. Impacts of landscape structure on surface urban heat islands: A case study of Shanghai. China. Remote Sens. Environ. 115, 3249–3263 (2011).

Wang, H. N., Tang, L. N., Qiu, Q. Y. & Chen, H. X. Assessing the impacts of urban expansion on habitat quality by combining the concepts of land use, landscape, and habitat in two urban agglomerations in China. Sustainability 12, 4346 (2020).

Wu, C. & Wang, Z. J. Multi-scenario simulation and evaluation of the impacts of land use change on ecosystem service values in the Chishui River Basin of Guizhou Province. China. Ecol. Indic. 163, 112078 (2024).

Sun, X. M., Lian, A. X., Wang, Z. R., Cai, Y. & Dong, R. C. Structural, functional, and resilience dynamics of ecological networks in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area: Impacts of climate and urbanization. J. Environ. Manage. 393, 126990 (2025).

Sha, A. M., Zhang, J. J., Pan, Y. J. & Zhang, S. G. How to recognize and measure the impact of phasing urbanization on eco-environment quality: An empirical case study of 19 urban agglomerations in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 210, 123845 (2025).

Wang, H. et al. Trade-off among grain production, animal husbandry production, and habitat quality based on future scenario simulations in Xilinhot. Sci. Total Environ. 817, 153015 (2022).

Ding, Y. K., Shan, B. Q. & Zhao, Y. Assessment of river habitat quality in the Hai River Basin, Northern China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. He. 12, 11699–11717 (2015).

Dhankar, S., Singh, G. & Kumar, K. Impacts of urbanization on land use, air quality, and temperature dynamics in Dehradun district of Uttarakhand, India: a comprehensive analysis. Front. Env. Sci. 12, 1324186 (2024).

Liu, C. et al. Research overview on Urban Heat Islands driven by computational intelligence. Land 13, 2176 (2024).

Anees, S. A., Mehmood, K. & Dube, T. Spatiotemporal analysis of surface Urban Heat Island intensity and the role of vegetation in six major Pakistani cities. Ecol. Inform. 85, 102986 (2025).

Wei, Y. P., Song, B. & Wang, Y. L. Designing cross-region ecological compensation scheme by integrating habitat maintenance services production and consumption-A case study of Jing-Jin-Ji region. J. Environ. Manage. 311, 114820 (2022).

Xu, J. J. et al. Monitoring of spatiotemporal changes in ecosystem service functions and analysis of influencing factors in Pingtan Island. Ecol. Indic. 158, 111590 (2024).

Lu, Y. & Qin, F. Improvements in the InVEST water purification model for detecting spatio-temporal changes in total nitrogen and total phosphorus discharges in the Huai river watershed. China. J. Environ. Manage. 366, 121918 (2024).

Zhang, K. L., Fang, B., Zhang, Z. C., Liu, T. & Liu, K. Exploring future ecosystem service changes and key contributing factors from a “past-future-action” perspective: A case study of the Yellow River Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 926, 171630 (2024).

Li, H. C. et al. A framework for dynamic assessment of soil erosion and detection of driving factors in alpine grassland ecosystems using the RUSLE-InVEST (SDR) model and Geodetector: A case study of the source region of the Yellow River. Ecol. Inform. 85, 102928 (2025).

Li, M. Y. et al. Evolution of habitat quality and its topographic gradient effect in northwest Hubei Province from 2000 to 2020 based on the InVEST model. Land 10, 857 (2021).

Ma, T. Q., Liu, R., Li, Z. & Ma, T. T. Research on the evolution characteristics and dynamic simulation of habitat quality in the southwest mountainous urban agglomeration from 1990 to 2030. Land 12, 1488 (2023).

García-Ontiyuelo, M., Acuña-Alonso, C., Valero, E. & Alvarez, X. Geospatial mapping of carbon estimates for forested areas using the InVEST model and sentinel-2: A case study in Galicia (NW Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 922, 171297 (2024).

Lei, J. R. et al. Spatiotemporal change of habitat quality in Hainan Island of China based on changes in land use. Ecol. Indic. 145, 109707 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Conservation outcome assessment of Wuyishan protected areas based on InVEST and propensity score matching. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 45, e02516 (2023).

Bacani, V. M. et al. Carbon storage and sequestration in a eucalyptus productive zone in the Brazilian Cerrado, using the Ca-Markov/Random Forest and InVEST models. J. Clean. Prod. 444, 141291 (2024).

Wei, Q. Q. et al. Temporal and spatial variation analysis of habitat quality on the PLUS-InVEST model for Ebinur Lake Basin. China. Ecol. Indic. 145, 109632 (2022).

Chen, Z., Chen, Y. J., Zhang, H. F., Zhang, H. & Xu, M. Understanding spatiotemporal changes and influencing factors in the habitat quality of coastal waters: A case study of Jiangsu Province, China (2006–2020). Ecol. Indic. 170, 113125 (2025).

Ekanayaka, H., Abeysingha, N. S., Amarasekara, T., Ray, R. L. & Samarathunga, D. K. The use of InVEST-SDR model to evaluate soil erosion and sedimentation in the closer catchment of a proposed tropical reservoir in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Sediment Res. 40, 253–268 (2025).

Rachid, L., Elmostafa, A., Mehdi, M. & Hassan, R. Assessing carbon storage and sequestration benefits of urban greening in Nador City, Morocco, utilizing GIS and the InVEST model. Sustain. Futures 7, 100171 (2024).

Wu, Q., Wang, L., Wang, T. Y., Ruan, Z. Y. & Du, P. Spatial-temporal evolution analysis of multi-scenario land use and carbon storage based on PLUS-InVEST model: A case study in Dalian. China. Ecol. Indic. 166, 112448 (2024).

He, S. et al. Water conservation assessment and its influencing factors identification using the InVEST and random forest model in the northern piedmont of the Qinling Mountains. J. Hydrol. Regional Studies 57, 102194 (2025).

Mukhopadhyay, A. et al. Global trends in using the InVEST model suite and related research: A systematic review. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 25, 389–405 (2024).

Liu, C. F. & Wang, C. Spatio-temporal evolution characteristics of habitat quality in the Loess Hilly Region based on land use change: a case study in Yuzhong County. Acta Ecol. Sinica 38, 7300–7311 (2018).

Song, Y. Y. et al. Land cover change and eco-environmental quality response of different geomorphic units on the Chinese Loess Plateau. J. Arid Land 12, 29–43 (2020).

Chang, Y. Y., Gao, Y., Xie, Z., Zhang, T. Z. & Yu, X. Z. Spatiotemporal evolution and spatial correlation of habitat quality and landscape pattern over Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. China Environ. Sci. 41, 848–859 (2021).

Zhang, T. J. & Chen, Y. N. The effects of landscape change on habitat quality in arid desert areas based on future scenarios: Tarim River Basin as a case study. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1031859 (2022).

Zhang, X., Tong, H. L., Zhao, L., Huang, E. W. & Zhu, G. F. Spatial and temporal dynamics and multi-scenario forecasting of habitat quality in Gansu-Qinghai contiguous region of the upper Yellow River. Land 13, 1060 (2024).

Li, G. Y., Cheng, G., Liu, G. H., Chen, C. & He, Y. Simulating the land use and carbon storage for nature-based solutions (NbS) under multi-scenarios in the three gorges reservoir area: Integration of remote sensing data and the RF-Markov-CA-InVEST model. Remote Sens. 15, 5100 (2023).

Tang, J. J., Yu, C., Zhang, W. W. & Chen, D. C. Habitat quality assessment and prediction in Suzhou based on CLUE-S and InVEST models. J. Environ. Eng. Technol. 13, 377–385 (2023).

Fu, F., Deng, S. M., Wu, D., Liu, W. W. & Bai, Z. H. Research on the spatiotemporal evolution of land use landscape pattern in a county area based on CA-Markov model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 80, 103760 (2022).

Wu, D. F. et al. Ecosystem services scenario simulation in Guangzhou based on the FLUS-InVEST model. Sci. Rep. 15, 14054 (2025).

Qin, Y. W. et al. Scenario-driven modeling of mountain ecosystems: land use-carbon dynamics simulation based on the coupled SD-FLUS-InVEST framework. Ecol. Model. 510, 111293 (2025).

Li, Z. Y. et al. Scenario-based assessment of urbanization-induced land-use changes and regional habitat quality dynamics in Chengdu (1990–2030): Insights from FLUS-InVEST modeling. Land 14, 1568 (2025).

Wang, C., Zhan, J. Y., Chu, X., Liu, W. & Zhang, F. Variation in ecosystem services with rapid urbanization: A study of carbon sequestration in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. China. Phys. Chem. Earth 110, 195–202 (2019).

Lv, F. R., Lu, Y. J. & Tang, H. P. Simulating the effect of haze management using system dynamics: a case study of Beijing. Front. Env. Sci. 12, 1400717 (2024).

Chang, H. Y. et al. Competitive and synergic evolution of the water-food-ecology system: A case study of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. China. Sci. Total Environ. 923, 171509 (2024).

Cui, Y. Y., Zhao, Y. X. & Li, X. C. Long-term time series estimation of impervious surface coverage rate in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urbanization and vulnerability assessment of ecological environment response. Land 14, 1599 (2025).

Xia, C. Y., Dong, Z. Y. Z. & Chen, B. Spatio-temporal analysis and simulation of urban ecological resilience: A case study of Hangzhou. Acta Ecol. Sinica 42, 116–126 (2022).

Luo, Y. et al. Spatial and temporal evolution of habitat quality and its shrinkage effect in shrinking cities: Evidence from Northeast China. Ecol. Indic. 161, 111919 (2024).

Zhou, J. et al. Driving mechanisms of ecosystem services and their trade-offs and synergies in the transition zone between the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and the Loess Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 171, 113148 (2025).

Li, K. & Zhang, B. Y. Analysis of the relationship between landscape fragmentation and ecosystem service value in northern Shaanxi. China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 30, 94537–94551 (2023).

Yan, Y. Z., Qi, Z. M. & Zhang, Q. Cross-scale effects of habitat fragmentation on local biodiversity and ecosystem multifunctionality in a fragmented grassland landscape. J. Ecol. 113, 1573–1584 (2025).

Gonçalves-Souza, T. et al. Species turnover does not rescue biodiversity in fragmented landscapes. Nature 640, 702–706 (2025).

Zhang, H. L., Chase, J. M. & Liao, J. B. Habitat amount modulates biodiversity responses to fragmentation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 1437–1447 (2024).

Su, Y. X. et al. Pervasive but biome-dependent relationship between fragmentation and resilience in forests. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 9, 1670–1684 (2025).

Fu, X. X. et al. Ecosystem resilience response to forest fragmentation in China: Thresholds identification. J. Environ. Manage. 380, 125180 (2025).

Wu, D., Zhu, K. W., Zhang, S., Huang, C. Q. & Li, J. Evolution analysis of carbon stock in Chengdu-Chongqing economic zone based on PLUS model and InVEST model. Ecol. Environ. Monit. Three Gorges 7, 85–96 (2022).

Wu, J. S., Li, X. C., Luo, Y. H. & Zhang, D. N. Spatiotemporal effects of urban sprawl on habitat quality in the Pearl River Delta from 1990 to 2018. Sci. Rep. 11, 13981 (2021).

Xiao, P. N., Zhou, Y., Li, M. Y. & Xu, J. Spatiotemporal patterns of habitat quality and its topographic gradient effects of Hubei Province based on the InVEST model. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 25, 6419–6448 (2023).

Wang, G. & Wang, J. W. Study on the impact of land use change on habitat quality in the coastal area of Dandong. J. Ecol. Environ. 30, 621–630 (2021).

Xie, Y. C., Gong, J., Zhang, S. X., Ma, X. C. & Hu, B. Q. Research on the temporal and spatial pattern of landscape biodiversity in the Bailong River Basin based on remote sensing and InVEST model. Geogr. Sci. 38, 979–986 (2018).

Bai, L. M., Xiu, C. L., Feng, X. H. & Liu, D. Q. Influence of urbanization on regional habitat quality: a case study of Changchun City. Habitat Int. 93, 102042 (2019).

Anees, S. A. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of vegetation cover: integrative machine learning analysis of multispectral imagery and environmental predictors. Earth Sci. Inform. 18, 152 (2025).

Anees, S. A. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics and environmental drivers of fractional vegetation cover in a Semi-Arid region using machine learning. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 156, 475 (2025).

Mehmood, K. et al. Spatial and temporal vegetation dynamics from 2000 to 2023 in the Western Himalayan regions. Stoch. Env. Res. Risk A. 39, 2309–2330 (2025).

Mehmood, K. et al. Exploring vegetation health in Southern Thailand under climate stress from temperature and water impacts between 2000 and 2023. Sci. Rep. 15, 30491 (2025).

Tang, J. J. et al. Impacts and predictions of urban expansion on habitat quality in the densely populated areas: A case study of the Yellow River Basin. China. Ecol. Indic. 151, 110320 (2023).

Lin, Z. Q. & Peng, S. Y. Comparison of multimodel simulations of land use and land cover change considering integrated constraints - A case study of the Fuxian Lake basin. Ecol. Indic. 142, 109254 (2022).

Lin, S. L. & Wang, F. Simulation and analysis of land use scenarios in Guangzhou based on the PLUS model and traffic planning scenario. J. Agric. Resour. Environ. 40, 557–569 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by Science and Technology Innovation Fund of Natural Resources Integrated Survey Command Center, China Geological Survey (No. KC20230005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Y. Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing, Visualization. X. Li: Methodology, Supervision, Funding acquisition. H.Z. Zhao: Formal analysis, Data curation. J.W. Li: Formal analysis, Visualization. Z.C. Zhao, J. Wu and W. Zhao: Writing-review & editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Li, X., Zhao, H. et al. Spatiotemporal variation, multi-scenario simulation, and driving factors analysis of habitat quality based on FLUS-InVEST and Geodetector models for Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, China. Sci Rep 16, 537 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30075-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30075-5