Abstract

Angiogenesis is a pivotal mechanism driving tumor proliferation, and the epigenetic regulation of angiogenesis represents a cutting-edge area of current research in multiple myeloma (MM). High-throughput sequencing was carried out to detect the cargos of exosomes from clinical serum and U266 cells, then GSE108824 database was analyzed for the finding of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). The intersect set was made based on the three gene sets. The clinical features of Metastasis-Associated Lung Adenocarcinoma Transcript 1 (MALAT1)were verified through GEO and clinicopathological data analyses. Cell viability, tube formation assay, level of MALAT1 and VEGFA were used to evaluate the effect of U266 exosome pretreated with or without paeoniflorin (PF) on angiogenesis in HUVEC cells. Subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice were established by injection of U266 cells and exosomes derived from U266 cells which pretreated with or without PF. Tumor size, HE staining, analysis of MALAT1 and VEGFA levels, as well as IHC staining for VEGFA, CD31, and Ki67 were performed to evaluate the in vivo effects of PF. The interactions between MALAT1, VEGFA, and microRNAs were demonstrated by TargetScan, MiRanda databases and Luciferase reporter assay. Furthermore, network pharmacology and RROMO, Genecards, AnimalTFDB, JASPAR databases were combinedto predict transcription factors (TF) associated with MALAT1 and analyze the binding sites between PF and these transcription factors. The validation of PF effect on TF was conducted by WB and PCR. Clinical studies indicated a notable positive correlation between MALAT1 level and VEGFA, CD31 expression, moreover, the high MALAT1 level is closely related to poor prognosis of MM. We demonstrated that MALAT1 was the highest expression linear RNA in U266 exosomes and could be transported to HUVEC cells through exosomes, promoting HUVEC cells differentiation and angiogenesis by stimulating VEGFA expression. The tube formation could be blocked if we knockdown the MALAT1 in U266 exosome. It was also proved that this pathological process can be blocked by PF in vitro and in vivo experiments. The ceRNA mechanism in MALAT1/miR-17/VEGFA was predicted and then confirmed by luciferase reporter assay. 2548 PF target genes were retrieved from databases, and the intersections with MALAT1-related differentially expressed proteins, mRNA and TF gene were identified Venn diagaram. MEF2A binding sites were predicted JASPAR, finally molecular docking showed strong affinity between PF and MEF2A (-16.5 kcal/mol).Then the effect of PF on MEF2A/MALAT1 was confirmed by WB or PCR test. To summarize, our study revealed that myeloma cells can increase angiogenesis by releasing exosome to influence the endothelial cells. The MALAT1 from myeloma cells is the crucial factor in this pathological process. PF can obstruct this process by intervening in the MEF2A/MALAT1 in myeloma cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant neoplasm characterized by clonal proliferation of plasma cells in the bone marrow. In recent years, researchers have increasingly recognized the pivotal role of angiogenesis in the pathogenesis, progression, and drug resistance of MM1,2. Angiogenesis not only facilitates tumor growth by ensuring an adequate supply of oxygen and nutrients but also serves as a conduit for cancer cell dissemination3. Therefore, investigating the regulatory mechanisms underlying angiogenesis in MM holds profound clinical significance: (1) Studies have revealed abundant angiogenic activity within the bone marrow microenvironment of multiple myeloma patients, with significantly increased vascular density compared to normal counterparts, underscoring its crucial involvement in disease development4. (2) Members of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family represent key regulators of angiogenesis, with markedly elevated expression levels observed in multiple myeloma that closely correlate with patient prognosis5,6. (3) Additionally, other factors such as matrix metalloproteinases7 and platelet-derived growth factors actively participate in orchestrating the intricate process of angiogenesis8. Exosomes released by multiple myeloma cells have been demonstrated to facilitate angiogenesis through the modulation of vascular endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and lumen formation9,10. Furthermore, the interplay between VEGF and other signaling molecules within exosomes also contributes to the regulation of angiogenesis11,12. Although thalidomide, lenalidomide and other drugs have been proven to treat multiple myeloma by inhibiting angiogenesis, there are still few studies on the intervention of angiogenesis by regulating exosomes.

Paeoniflorin (PF), an active compound derived from the peony plant, has been extensively investigated for its potential in tumor treatment. Research has demonstrated that PF exhibits antitumor activity by inhibiting the growth and proliferation of tumor cells and inducing programmed cell death (apoptosis) with other drugs or radiation13,14. Moreover, it can effectively suppress the invasion and metastasis capabilities of tumor cells, thereby impeding their spread15. PF also possesses antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which contribute to reducing inflammatory responses in cancer patients while enhancing immune system function16. Furthermore, studies have revealed that PF enhances chemotherapy efficacy by increasing sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs and improving tumor response17,18. Additionally, PF exerts its anti-tumor effects through modulation of various signaling pathways involved in tumorigenesis such as PI3K/Akt19, MAPK20, and NF-κB pathways21. Although there have been reports indicating that PF can improve neurons apoptosis22, suppress angiogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis23 and glioblastoma24, effectively inhibit the expression of MMP-2 by up-regulating miR-29b, thereby exerting inhibitory effects on MM cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis25, no research has been conducted on the therapeutic potential of PF in exosome derived from multiple myeloma cells. Therefore, we designed the present study to explore the role of aberrant lncRNA in MM-derived exosomes on MM angiogenesis and the pharmacological mechanisms underlying PF regulation of MM tumor progression (Fig. 1).

Materials and methods

Patients and clinical specimens

Six MM patients who were admitted to the Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine were enrolled in the study. Five healthy adult volunteers were included in the experiment as healthy controls (HCs). The peripheral blood of the subjects was collected with a vacuum coagulation tube, and the serum was obtained after centrifugation (5 min, 2500 rpm) and stored at -80 °C.

During the period from 2020 to 2023, bone marrow tissue samples and clinical data were collected from newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients at the Hematology Department of the Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine and the Hematology Department of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Each bone marrow biopsy tissue sample was immediately fixed with 4% formalin and embedded in paraffin after removal.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration revised in 2008, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. All experimental methods were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital (2020 Ethics Review-KY-010) and the Second Affiliated Hospital (2023 Ethics Review-KY-001).

Materials

NOD-SCID mice were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Ethics number: AWE-2019-038) and following the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals for Research Purposes. U266 and HUVEC cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Virginia, USA). PF was purchased from Winherb Medical Science Co., Ltd. (purity: 98.96%, 23180-57-6, Shanghai, China). A cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (lot No. E-BC-K138-F, China). Antibodies against MEF2A(12382-1-AP) were purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc (Rosemont, USA).

Isolation of exosomes

250 µL of clinical serum samples were mixed with 63 µL ExoQuick exosome precipitation solution (System Bioscience, Palo Alto, CA, USA), followed by incubation for 30 min on ice and centrifugation (30 min,1500×g). The supernatant was aspirated and centrifuged for another 5 min. Afterwards, the pelleted exosomes were isolated.

U266 cell exosomes were purified by differential centrifugation and purification procedures. Cells were incubated with exosome-free FBS for 48 h, then the conditioned medium was centrifuged (2000×g, 20 min) using an ultracentrifuge (Beckman Optima L-100XP) and the supernatant was collected. Desquamated vesicles and other large vesicles were removed from the supernatant using a 0.22-µm filter (Merck Millipore, Germany). After centrifugation of the supernatant (20000×g, 70 min), the exosomes were resuspended in PBS and ultracentrifuged again (170000×g, 90 min) to collect exosomes.

Validation of exosomes by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA)

The exosomes that were separated from the serum were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, cleaned with PBS, and then allowed to sit at room temperature for 20 min on formvar-/carbon 200-mesh copper grids. Following five minutes of fixing the samples in 1% glutaraldehyde, we washed the grids three times with ultrapure water before staining them for five minutes with uranyl oxalate. The samples were then treated with 4% uranyl acetate and 2% methylcellulose in a 1:9 ratio on ice and allowed to dry before being examined with transmission electron microscopy (Hitachi, HT7700) to detect the exosomes.

The NanoSight NS300 system (NanoSight, Amesbury, UK) was used to assess the size distribution and concentration of exosomes based on their Brownian motion and light scattering properties. Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBs) without any nanoparticles was used to dilute the sample 150–3000 times until it reached a concentration of 1–20 × 108 capsules per milliliter for the analysis. A high-sensitivity sCMOS camera set up with the NanoSight NS300 system was used to measure each sample three times, recording and tracking every visible particle. NTA software (NanoSight version 2.3) was used to evaluate the data, and the Stokes-Einstein equation was used to determine the exosome numbers and size distribution.

PBS and HEK-293 cells (Human Embryonic Kidney) exosomes were set as negative control and positive control, respectively (Fig. S1). After successful extraction and identification of exosomes, the following high-throughput sequencing was carried out by Cloud-Seq Biotech (Shanghai, China).

The differentially expressed non-coding RNAs were identified by intersecting the GEO dataset with sequencing data of exosomes derived from clinical serum specimens and U266 cells

The GSE108824 dataset was queried in the GEO database using “multiple myeloma” as a keyword, and a volcano plot was generated to elucidate the differentially expressed genes (DEGs). By intersecting with non-coding RNA sequencing results of clinical serum- and U266-derived exosomes, MALAT1 was identified as a candidate biomarker.

RNA fluorescent in situ hybridization (RNA-FISH)

The expression levels and subcellular localization of MALAT1 in bone marrow samples and HUVECs were assessed using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis. GFP-labeled MALAT1 probes, synthesized by Beijing Dingguo Changsheng Biotech Co., Ltd., were utilized for the FISH analysis. All fluorescence images were captured using a confocal laser scanning microscope. The probe sequence is 5’ AACCCACAAACTTGCCATCTACTAT 3’.

Cells culture and treated

To verify the effect of U266 exosomes on MALAT1 of HUVEC cells and angiogenesis, exosomes derived from U266 cells were extracted. The HUVEC cells were divided into four groups: (1) Control group, (2) EXO group (co-cultured with U266 exosomes), (3) Lnc MALAT1 knockdown group (transfected with si-MALAT1), (4) EXO + Lnc MALAT1 knockdown group (co-cultured with U266 exosomes after transfection of si-MALAT1).

To detect the effect of paeoniflorin intervention exosomes on angiogenesis, the U266 cells were divided into four groups for exosome isolation: (1) the exosome group, (2) the PF-treated exosome group with different doses of PF (50, 100, and 200 µM) administered to the cells for 12 h before exosome isolation. After isolating the exosomes using the aforementioned method, they were co-incubated with HUVEC cells.

Construction of mouse model

The NOD-SCID (20 ± 2 g) mice were divided into a control group and an intervention group. When the U266 cells were cultured in the logarithmic growth phase, they were collected and subcutaneously inoculated on the right side of the mice at a density of 1 × 107 cells/mouse. Matrix glue was added during inoculation to promote tumor formation. After 7 days of tumor formation, when the subcutaneous size reached 100 mm3, exosomes pretreated with or without different doses of PF (25, 50, and 100 µM) were injected intratumorally in the intervention group every three days. On the 19th day, subcutaneous tumors were harvested from both groups for analysis. The control group received an intratumoral injection of normal saline in an equal volume to that used for exosome injection in the intervention group. Tissue embedding, sectioning, Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for CD31 and VEGFA and microvessel density (MVD) were performed to assess tumor proliferation. The experimental animals were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (200 mg /kg).

Cell viability assays

The cells were plated into 96-well plates at 2 × 104 cells per well in 100 µl of growth medium (RPMI-1640+10% FBS+1% P/S), and then cultivated for 2 h. 10 µL CCK-8 was treated into each well for further 1 h. After that, the OD value was measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader.

PKH26 staining

The PKH26 dye (100µL) was mixed with Diluent C (100µL). Subsequently, exosomes derived from MM cells (50 µg) were added to the mixture and incubated for 3 min. To halt the reaction, 0.5% exosome-free FBS was added and incubated for 5 min. The labeled exosomes were then washed twice with PBS before being co-cultured with recipient cells in the plate for 12 h before imaging.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from the cultured cells (2 × 106 cells/well) using Trizol RNA isolation reagents. cDNA synthesis was performed using 10 µg of total RNA with a reverse transcription kit. The PCR was performed 3 times. The primers used were 5′- GCGCAAAGTGCTTACAGTGC-3′(miR-17,forward),5′-AGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATT-3′(miR-17,reverse), miR-17 RT-Primer is 5′- GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACCTACCT − 3′, 5′- CCGCTGCTATTAGAATGC-3′ (MALAT1,forward), and 5′- CTTCAACAATCACTACTCCAA − 3′(MALAT1, reverse), 5′- GTCCCTCTTGGAATTGGAT − 3′(VEGFA, forward), and 5′- TGTATGTGGGTGGGTGTGTC − 3′(VEGFA, reverse). The relative mRNA levels were normalized to ACTB, the primers used for ACTB were 5′-TGACGTGGACATCCGCAAAG-3′ (ACTB, forward) and 5′-CTGGAAGGTGGACAGCGAGG-3′ (ACTB, reverse). The relative mRNA expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assa4 analysis (EILSA)

The levels of VEGF from cells and mice were detected using ELISA kits (Thermo, EHVEGFACL and ERVEGFACL, USA). Briefly, the sample to be tested and the standard were added to the corresponding enzyme plate for incubation. After the chromogenic antibody was added, the reaction was terminated by adding a termination solution to the enzyme plate. The OD value was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo, USA).

Tube formation assay

A total of 4 × 104 HUVECs were seeded in a 12-well plate and treated with PBS or different exosomes for 24 h. For tube formation, Matrigel was used to coat 96-well plates and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min to allow the Matrigel to polymerize. After treatment with PBS or different exosomes, a total of 4 × 104 HUVECs were seeded in the Matrigel-coated wells. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. After 12 h, tube formation was visualized with a microscope and determined by measuring the number of tubes. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Construction of the competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network of MALAT1

Cytoscape (Version 3.8.2) was used to build the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network of MALAT1. The top 20 mRNAs with the strongest ability to bind these miRNAs were predicted using TargetScan after the top five miRNAs with the best ability to bind MALAT1 were predicted using MiRanda.

Luciferase reporter assay

The wild-type plasmids of VEGFA mRNA binding MALAT1 or miR-17 were cloned into a psiCHECK2 dual-luciferase plasmid and co-transfected with miR-17 agomir; the wild-type plasmids of MALAT1 binding miR-17 were also cloned into a psiCHECK2 dual-luciferase plasmid and co-transfected with miR-17 agomir into 293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000. After 48 h of transfection, luciferase activities were measured using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, E2920).

Immunohistochemistry

The tumor tissues were fixed with formaldehyde, decolorized, washed, embedded, and sectioned. After incubation with primary antibody at 37 °C and incubation with biotin-labeled secondary antibody at room temperature, the tissues were finally placed in 3,3-N-diamino biphenyl tetrahydrate substrate solution. The protein expression was quantitatively detected by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 image analysis and measurement system, and the average area and average integral optical density of protein expression were calculated.

Evaluation of microvessel density (MVD)

CD34-labeled microvessels were used to estimate the degree of angiogenesis. The slides were scanned under 100× magnification to locate the areas with the maximum number of microvessels (hotspots). The microvessel numbers in each field were measured at 400× magnification, and the average value was obtained as the MVD in each field.

RNA pulldown assay

After biotinylated wild-type or mutant MALAT1 was synthesized using a T7 Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), it was treated with RNase-free DNase I (Roche) and purified using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Following incubation of whole cell lysate with purified biotinylated transcripts, the complexes were separated using streptavidin agarose beads (Invitrogen). The protein pulled down by MALAT1 was detected through western blotting.

PF and TF predicted targets, molecular Docking

The targets of PF were predicted using PharmMapper, TCMSP, PubChem, and BATMAN-TCM databases. Subsequently, the three-dimensional molecular structure of PF was retrieved from the PubChem database. The sequence of MALAT1 justice chain was obtained through the NCBI platform, with the 2 kb sequence upstream of the transcription initiation site considered as the promoter region. The RROMO database was utilized for the prediction of transcription factors associated with MALAT1. Genecards and AnimalTFDB databases were combined to obtain a comprehensive list of transcription factors, which was then intersected with PF targets resulting in the identification of four targets: U2AF2, HMGB2, CDC5L, and MEF2A. JASPAR was employed to predict the binding sites between MALAT1 and transcription factors, revealing that only MEF2A exhibited binding sites with MALAT1. The structure of MEF2A protein was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), followed by molecular docking analysis performed using AMdock.

Western blot

Total proteins were extracted from collected cells through lysis, followed by separation on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The separated proteins were then transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane and incubated with the primary antibody in skim milk three buffer saline. After washing off the secondary antibody, protein detection was performed and analyzed for exposure using an imaging machine.

Statistical analysis

The experimental results were subjected to statistical analysis using SPSS 19.0 and GraphPad Prism 8.0 (Dotmatics, USA). If the data in each group followed a normal distribution and exhibited homogeneity of variance, quantitative data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (\(\bar{x}\) ± s). Differences between two groups were assessed using the t-test, while differences among multiple groups were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance. Statistical significance was considered for differences with P values less than 0.05.

Results

The clinical significance of MALAT1 and its correlation with angiogenesis

High-throughput sequencing showed that there were 10,106 differentially expressed.

lncRNAs in the MM group compared with the HC group, of which 30,683 were upregulated and 11,757 were downregulated (|logFC| <1.5). Then we analyzed and summarized the identified lncRNAs based on length, location and category (Fig. 2A-C). To further validate the clinical significance of lncRNAs, we analyzed the GEO database (GSE108824) and 406 differently expressed genes (DEGs) were screened out (|logFC| <1.5, P < 0.05) (Fig. 2D). Based on the DEGs and the high-throughput sequencing data of U266 exosomes (Fig. 2E), Lnc MALAT1 was chosen.

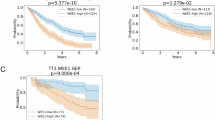

The clinical significance of MALAT1 and its correlation with angiogenesis. (A) LncRNAs were distributed on 22 autosomes and sex chromosomes (X, Y). (B) The lncRNA categories to which each of the 2052 circRNAs belongs. (C) Distribution of the lncRNAs based on the predicted sequence length. (D) Volcano plot of DEGs from GEO5900 dataset. (E) The top 10 expression lncRNAs in U266 exosomes. (F) KM curve analysis comparing MALAT1 high-risk and low-risk groups. (P < 0.0001). (G) The accuracy of MALAT1 in predicting the death outcome of MM patients. (H, I) Analysis of MALAT1 FISH in high-risk and low-risk groups of MM patients. (J) CD31 and VEGFA IHC images of MM patients’ BM. (K) Analysis of MVD and VEGFA level in high-risk and low-risk groups. (L) MALAT1 expression positively correlated with MVD and VEGFA levels. Three independent experiments were performed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Subsequently, based on the MALAT1 data from our patients, Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated that higher expression levels of MALAT1 were associated with poor outcomes (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, we observed an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) of 0.876 (Fig. 2G). Additionally, FISH examination revealed a significant abundance of MALAT1 in the bone marrow of high-risk multiple myeloma patients (Fig. 2H, I). IHC results and linear regression analyses revealed that MALAT1 can significantly positively relative to MVD (R2 = 0.853, P < 0.001) and VEGFA expression (R2 = 0.726, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2J-L). We also explored the relationship between clinical characteristics and survival rate by univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis. Univariate Cox regression analysis showed that hemoglobin (HGB) < 100 g/L, ISS stage, MVD ≥ 45, and MALAT1 ≥ 79.24 had significant negative effects on the survival rate (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

The MALAT1 derived from MM exosomes exhibits the ability to enhance angiogenesis

To investigate whether MALAT1 in exosomes derived from MM cells promotes angiogenesis, HUVECs were cultured with exosomes isolated from U266 cells. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed that the exosomes exhibited disc-shaped structures measuring 30–150 nm in size (Fig. 3A). Additionally, nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) confirmed an average diameter of approximately 100 nm for the exosomes (Fig. 3B). To assess the uptake of MALAT1-containing exosomes by HUVECs, PKH26 dye was used to label the exosomes while GFP was employed to label MALAT1; subsequently, co-culturing experiments were conducted with HUVEC cells. Confocal microscopy images depicted yellow signals predominantly localized within the cytoplasm of recipient cells, indicating that MALAT1 could be transported into HUVEC cells by exosomes, this observation was further validated through qPCR analysis (Fig. 3C, E).

Mechanistic study of MALAT1 derived from U266 enhance angiogenesis in HUVECs. (A) The shapes and sizes of serum exosomes were observed by TEM. (B) The average diameter and concentration of exosomes were calculated by NTA.(C) The intercellular trafficking of MALAT1 is facilitated by exosomes, which are taken up by HUVEC cells. This process was observed using isolated exosomes labeled with PKH26 dye and MALAT1 labeled with GFP. (D) The cell viability assays were performed on HUVEC cells, both with and without MALAT1 knockdown, following co-culture with exosomes. (E) MALAT1 level was tested by PCR. (F) VEGFA level was tested by PCR. (G) VEGFA level was tested by ELISA. (H) Tube formation assays were performed on HUVEC cells, both with and without MALAT1 knockdown, following co-culture with exosomes.(I) The ceRNA network diagram illustrating the interaction between MALAT1, miRNAs, and target mRNA genes.(J)The direct interaction between miR-17 and MALAT1 as well as VEGFA was confirmed through dual-luciferase reporter assays.Three independent experiments were performed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

We then transfected HUVEC cells with si-MALAT1 and co-incubated them with exosomes derived from U266 cells. Cell viability experiments demonstrated that exosomes enhanced the differentiation of both MALAT1 knockdown and non-knockdown HUVEC cells by upregulating the expression level of MALAT1 (Fig. 3D, E). Exosomes significantly augmented the expression of VEGFA as well (Fig. 3F, G). Consequently, Tube formation assays revealed an increased number of tube formations in HUVEC cells upon the addition of exosomes (Fig. 3H).

MALAT1 sponges miR-17 to promote VEGFA expression

To determine whether MALAT1 affects VEGFA, a key gene in angiogenesis, by affecting miRNA expression, we first predicted candidate miRNAs targeted by MALAT1 and top 5 miRNAs were selected (miR-17, miR-140, miR-205, miR-15, miR-29). Then, we constructed ceRNA nets by predicting MALAT1, miRNA and target mRNA by TargetScan, and VEGFA was seen in the figure (Fig. 3I). It has been reported that miR-17 is involved in the regulation of angiogenesis as a downstream of MALAT126. Therefore, miR-17 was selected and we first investigated whether MALAT1 directly binds to miR-17. One binding site was selected from 15 binding sites between MALAT1 and miR-17 to construct a luciferase reporter plasmid encoding truncated MALAT1. We transfected miR-17 mimics into HEK293T cells and observed that the luciferase activities of MALAT1 and VEGFA were significantly decreased after adding miR-17 mimics (Fig. 3J). These data suggest that MALAT1 acts as a sponge for miR-17, promoting VEGFA expression, and thereby increasing HUVEC differentiation and tube formation.

Effect of PF on angiogenesis by regulating MALAT1 level of MM exosomes

The MALAT1 level of cells after co-culture with HUVEC was examined in Fig. 4A, following pretreatment of exosomes with varying doses of PF. CCK8 experiments revealed a significant decrease in the MALAT1 level (P < 0.05) upon treatment with a high dose of PF, as depicted in Fig. 4B. Consequently, the tubular formation of HUVEC cells (Fig. 4C, D) and VEGFA expression (Fig. 4E, F) were significantly reduced due to the impact on U266 exosomes by PF.

PF inhibit angiogenesis by decrease the MALAT1 level of exosomes. (A) The MALAT1 level was assessed using PCR in different dosage groups treated with PF, the medium-dose PF treated group was selected for further investigation based on the level of MALAT1. (B) The cell viability assays were conducted on HUVEC cells, following co-culture with exosomes which derived from U266 cells after treated with or without a medium dose of PF. (C, D) Tube formation assays were performed on HUVEC cells. (E, F) VEGFA level was tested by PCR or ELISA. Three independent experiments were performed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

PF exerted potent anti-angiogenesis and antitumor effects on animal model

We established a xenograft model of MM by subcutaneously injecting U266 cells with or without exosomes to further validate the in vivo anti-angiogenic and anti-tumor effects of PF. Compared to the EXO group, the tumor volume was significantly reduced in the treatment groups receiving different doses, particularly when co-cultured with exosomes pretreated with medium- and high-dose PF (Fig. 5A, P < 0.05). Furthermore, as depicted in Fig. 5B, the MALAT1 level in the treatment group was markedly lower than that in the EXO group (P < 0.01), indicating that PF effectively suppressed tumor growth by reducing MM exosomal MALAT1 levels. In addition, according to the results of HE staining, tumor cells in each group were arranged in sheets diffusely, and compared with the model group, the mitotic number and weight in the treatment group were significantly reduced (Fig. 5C, D), indicating that PF had a strong tumor suppressor effect. PCR, ELISA and IHC staining were performed on VEGFA, and it was found that the expression level of VEGFA in the treatment group was significantly lower than that in the EXO group (Fig. 5E-H, P < 0.01). Ki-67 data also showed that PF could reduce the tumor burden (Fig. 5G, H, P < 0.01). For the MVD test, compared with the EXO group, PF reduced the levels of CD31 and MVD (Fig. 5G, H, P < 0.01). Consistent with the results of in vitro experiments, in vivo studies have shown that PF has anti-myeloma effects, and its anti-cancer mechanism is related to the induction of anti-angiogenesis.

Effect of PF on mice model. (A) Compared to the EXO group, the tumor volume was significantly reduced when injected with exosomes pretreated with medium and high dose PF. (B) MALAT1 level was tested by PCR. (C) HE staining of the excised tumors from different experimental groups. (D) The tumor weight was analyzed in different experimental groups. (E, F) VEGFA level was tested by PCR or ELISA. (G, H) The evaluation of Ki67, CD31, and VEGFA IHC images in tumor tissues.(I) Analysis of MVD level in different experimental groups.Three independent experiments were performed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Mechanistic study of PF intervention on MALAT1 of exosomes by network Pharmacological analysis

A total of 2,548 PF-related target genes were retrieved from the PharmMapper, TCMSP and BATMAN-TCM databases based on the structure from PubChem (Fig. 6A). To obtain the intersection of PF target genes, a Venn diagram analysis was conducted based on differentially expressed proteins pulled down by MALAT1 for PF target genes, mRNA, and TF gene (Fig. 6B). According to the predicted binding sites of MALAT1 and transcription factors by JASPAR, the binding site representing MEF2A was displayed (Fig. 6C). Subsequently, molecular docking results demonstrated a strong binding affinity (-16.5 kcal/mol) between PF and MEF2A (Fig. 6D). Furthermore, qRT-PCR and Western blot results confirmed that PF effectively suppressed the expression levels of both MEF2A and MALAT1 in U266 cells (Fig. 6E, F).

The mechanism PF on MALAT1. (A) The structure of PF.(B) The Venn plot of intersection genes of MALAT1 pull down gene, TF gene and PF target genes. (C) The binding site between MALAT1 and MEF2A was displayed. (D) The docking sites of PF between MEF2A. (E) WB analysis of MEF2A level in U266 cells treated with or without PF. (F) MALAT1 level in U266 cells treated with or without PF.Three independent experiments were performed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

The introduction of new drugs in recent years has significantly improved the treatment outcomes for multiple myeloma; however, it remains an incurable disease. Finding novel therapeutic strategies to enhance the long-term survival of patients with multiple myeloma, particularly those with relapsed and refractory disease, remains a prominent concern in the field. It is established that MM cells can act on endothelial cells via cell–cell contact or delivery of soluble substances able to create an advantageous milieu27,28. MM cells produce components like miRNAs29,30, angiogenesis-correlated proteins28 to stimulate angiogenesis.

The long non-coding RNA MALAT1 exhibits aberrant expression in various tumors and plays a crucial role in tumorigenesis and developmental processes.MALAT1 has been shown to regulate angiogenesis by regulating the angiogenic factor, VEGF31, the upregulation of MALAT1 can promote angiogenesis causing poor overall survival in breast cancer32, ovarian cancer33. The aberrant expression of MALAT1 in multiple myeloma is closely associated with the processes of proliferation, angiogenesis, and immune evasion. MALAT1 exerts regulatory control over cell proliferation and apoptosis in multiple myeloma34, while also promoting tumorigenesis and angiogenesis through the regulation of microRNA-15a/16-VEGFA axis35. Transcription factors can specifically bind to DNA and regulate RNA transcription, which is a crucial mechanism for the regulation of lncRNA. The expression of MALAT1 can be modulated by transcription factors or actively participate in the biological processes regulated by these factors. For instance, it interacts with PRC1 and PRC2 subunits as well as SP1 to promote proliferation and metastasis of renal36, bladder37, and lung cancer cells38. Additionally, under stress conditions, MALAT1 can regulate hypoxia-inducible factor 2α (HIF2α)39.

MEF2A, a transcription factor, plays a crucial role in various biological processes, including tumor angiogenesis. FGF12 regulates the BMP-induced phenotypic change by promoting phosphorylation of MEF2a (myocyte enhancer factor 2a) through p38MAPK signaling, thereby modulating the expression of MEF2a target genes involved in cell proliferation and differentiation40. The inhibition of MEF2A levels by miR-144-3p significantly suppresses the proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis of MM cells41.

In this study, we initially conducted a comprehensive search for differentially expressed lncRNAs by high-throughput sequencing of the GEO database (Fig. 2A-D). Additionally, we integrated our own patients’ exosomal lncRNA sequencing data (Fig. 2A-C), DEGs from the GEO database (Fig. 2D), and the U266 exosome sequencing results (Fig. 2E) to identify MALAT1 as our research target by intersecting these two datasets. Furthermore, in conjunction with our clinical data, we examined the expression of MALAT1 in bone marrow biopsy specimens (Fig. 2H), revealing a significantly lower long-term survival rate among patients with high MALAT1 expression (Fig. 2F). Moreover, there was a positive correlation between MALAT1 expression and levels of bone marrow MVD and VEGFA in patients (Fig. 2L). To verify the role of MALAT1 in exosomes secreted by myeloma cell line U266 in promoting angiogenesis, we first conducted a tracing analysis of MALAT1 in exosomes and found that it could be endocytosed by HUVEC cells (Fig. 3C). After knocking down MALAT1 in HUVEC cells and co-incubating with exosomes, exosomes could restore the viability of HUVEC cells, the level of MALAT1 and VEGFA (Fig. 3). Moreover, under the intervention of exosomes, the tuber number was significantly increased (Fig. 3H). The role of MALAT1 in regulating VEGFA expression and promoting myeloma angiogenesis has been confirmed by the above clinical studies and in vitro experiments. LncRNA often plays a role by competitively adsorbing mRNA with miRNA42, so we took the ceRNA mechanism as a breakthrough point to find the molecular mechanism of MALAT1 regulating VEGFA. MiR-17 has been identified to be closely related to angiogenesis in gastric cancer, glioblastoma, etc43,44. A previous study revealed that MALAT1 performed the task of a miR-17 sponge to regulate the expression of VEGF to increase the proliferation, migration, and tube formation of HCVECs. Consistent with previous research, we confirmed that MALAT1 could regulate the expression of VEGFA by interfering with the level of miR-17 by bioinformatics analysis and luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 3I, J).

PF can inhibit angiogenesis, reduce rheumatoid arthritis inflammation45, and regulate VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling pathway to inhibit angiogenesis, thereby reducing diabetic retinopathy46 and stabilizing atherosclerotic plasques47. Exosomes were extracted from U266 cells treated with varying concentrations of PF in the in vitro experiment and co-incubated with HUVEC cells. Results showed that exosomes pretreated with medium and high concentrations of PF had significantly lower levels of MALAT1 and VEGFA compared to the EXO group (Fig. 4A, E, F), as well as a significantly reduced tube number (Fig. 4C, D). In the in vivo experiment using a subcutaneous tumor-bearing mouse model established by injecting U266 cells, it was found that exosomes pretreated with medium and high concentrations of PF had significantly worse tumorigenic effects and MVD levels than those in the EXO group (Fig. 5A-D, G), which was closely associated with VEGFA level.

With the aid of network pharmacology, the targets of PF, MALAT1 pull-down targets, and the transcription factor dataset were intersected (Fig. 6B). The interaction sites between MEF2A and MALAT1 were predicted using the JASPAR website (Fig. 6C). And molecular docking analysis revealed binding sites between PF and MEF2A (Fig. 6D). Subsequently, experimental evidence validated that PF effectively decreased MALAT1 expression by interfering with MEF2A (Fig. 6E, F).

Undeniably, due to limitations of experimental conditions, an in-depth mechanism by which PF affects MALAT1 via MEF2A has not been elucidated. In our future work, we intend to perform ChIP-qPCR to verify the binding of MEF2A to the promoter of MALAT1 and detect the changes of MALAT after knockdown or overexpression of MEF2A and the intervention of PF.

Conclusions

Angiogenesis plays an important role in the pathogenesis and development of multiple myeloma. An in-depth study of the mechanism of angiogenesis regulation, finding and developing new anti-angiogenic drugs will help improve the treatment effect of multiple myeloma patients and provide a better prognosis. This study confirmed that MALAT1 derived from U266 exosome promotes MM angiogenesis by regulating miR-17 to promote VEGFA level, while PF can reduce MM angiogenesis by targeting MEF2A to inhibit MALAT1 expression. However, the mechanism by which PF affects MALAT1 via MEF2A needs further investigation.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the data are in the confidential stage but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hose, D. et al. Induction of angiogenesis by normal and malignant plasma cells. Blood 114, 128–143 (2009).

Ribatti, D., Nico, B. & Vacca, A. Importance of the bone marrow microenvironment in inducing the angiogenic response in multiple myeloma. Oncogene 25, 4257–4266 (2006).

Ribatti, D., Nico, B., Crivellato, E., Roccaro, A. M. & Vacca, A. The history of the angiogenic switch concept. Leukemia 21, 44–52 (2007).

Rajkumar, S. V. et al. Bone marrow angiogenesis in 400 patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, multiple myeloma, and primary amyloidosis. Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 2210–2216 (2002).

Vacca, A. et al. Bone marrow neovascularization, plasma cell angiogenic potential, and matrix metalloproteinase-2 secretion parallel progression of human multiple myeloma. Blood 93, 3064–3073 (1999).

Ria, R. et al. Endothelial differentiation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells from patients with multiple myeloma. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 1678–1685. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4071 (2008).

Ribatti, D. & Vacca, A. Multiple myeloma bone marrow angiogenesis. In Multiple Myeloma. A New Era of Treatment Strategies (eds. Podar, K. & Anderson, K. C.) 138–148 (Bentham Science, 2012).

Coluccia, A. M. L. et al. Validation of PDGFR and c-Src tyrosine kinases as tumor/vessel targets in patients with multiple myeloma: preclinical efficacy of the novel, orally available inhibitor dasatinib. Blood 112, 1346–1356 (2008).

Miaomiao, S. et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived exosome microRNA-21 promotes angiogenesis in multiple myeloma. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 9671 (2023).

Tian, X. et al. Exosome-derived miR-let-7c promotes angiogenesis in multiple myeloma by polarizing M2 macrophages in the bone marrow microenvironment. Leuk. Res. 105, 106566 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Multiple myeloma exosomes Establish a favourable bone marrow microenvironment with enhanced angiogenesis and immunosuppression. J. Pathol. 239 (2), 162–173 (2016).

Li, B. et al. piRNA-823 delivered by multiple myeloma-derived extracellular vesicles promoted tumorigenesis through re-educating endothelial cells in the tumor environment. Oncogene 38 (26), 5227–5238 (2019).

Nie, X. H. et al. Paeoniflorin regulates NEDD4L/STAT3 pathway to induce ferroptosis in human glioma cells. J. Oncol. 2022, 6093216 (2022).

Kim, T. W. P. & Induces, E. R. Stress-Mediated apoptotic cell death by generating Nox4-Derived ROS under radiation. Gastric Cancer Nutrients. 15 (24), 5092 (2023).

Su, Z. et al. Paeoniflorin inhibits colorectal cancer cell stemness through the miR-3194-5p/catenin beta-interacting protein 1 axis. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 39 (10), 1011–1021 (2023).

Kim, T. W. Paeoniflorin induces ER Stress-Mediated apoptotic cell death by generating Nox4-Derived ROS under radiation in gastric cancer. Nutrients 15 (24), 5092 (2023).

Jan, K., Hassan, N., James, A., Hussain, I. & Rashid, S. M. Exploring molecular targets in cancer: unveiling the anticancer potential of Paeoniflorin through a comprehensive analysis of diverse signaling pathways and recent advances. J. Biol. Methods. 11 (2), e99010014 (2024).

Zhu, W. et al. Paeoniflorin alleviates necroptosis in acute kidney injury induced by cisplatin and Lansoprazole through targeting TNFAIP3. Int. Immunopharmacol. 164, 115340 (2025).

Cao, C. et al. Deciphering the action mechanism of Paeoniflorin in suppressing pancreatic cancer: a network Pharmacology study and experimental validation. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 1032282 (2022).

Wu, T. et al. The active components and potential mechanisms of Wuji Wan in the treatment of ethanol-induced gastric ulcer: an integrated metabolomics, network Pharmacology and experimental validation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 326, 117901 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Paeoniflorin increases the anti-tumor efficacy of Sorafenib in tumor-bearing mice with liver cancer via suppressing the NF-kappab/PD-l1 axis. Heliyon 10 (2), e24461 (2024).

Zhu, Y. et al. Paeoniflorin effect of Schwann Cell-Derived exosomes ameliorates dorsal root ganglion neurons apoptosis through IRE1alpha pathway. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2021, 6079305 (2021).

Hao, J. et al. Network pharmacology-based prediction of inhibiting leukocyte recruitment and angiogenesis of total glucosides of peony against rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 11 (10), 3085–3101 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Paeoniflorin inhibits EMT and angiogenesis in human glioblastoma via K63-Linked C-Met Polyubiquitination-Dependent autophagic degradation. Front. Oncol. 12, 785345 (2022).

Wang, S. Wenhua Liu.Paeoniflorin inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis of multiple myeloma cells via its effects on MicroRNA 29b and matrix metalloproteinase 2. Mol. Med. Rep. 14 (3), 2143–2149 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. LncRNA MALAT1 knockdown inhibits the development of choroidal neovascularization. Heliyon 9 (9), e19503 (2023).

Moschetta, M. et al. Bone marrow stroma and vascular contributions to myeloma bone homing. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 15, 499–506 (2017).

Kocemba, K. A. et al. The hypoxia target adrenomedullin is aberrantly expressed in multiple myeloma and promotes angiogenesis. Leukemia 27, 1729–1737 (2013).

Lee, J. Y. et al. Exosomal miR-1305 in the oncogenic activity of hypoxic multiple myeloma cells: A biomarker for predicting prognosis. J. Cancer. 12, 2825–2834 (2021).

Umezu, T. et al. Replenishing exosomes from older bone marrow stromal cells with miR-340 inhibits myeloma-related angiogenesis. Blood Adv. 1, 812–823 (2017).

Li, X. et al. Long Non-Coding RNA MALAT1 promotes Proliferation, Angiogenesis, and immunosuppressive properties of mesenchymal stem cells by inducing VEGF and IDO. J. Cell. Biochem. 118 (9), 2780–2791 (2017).

Ou, X. et al. MALAT1 and BACH1 are prognostic biomarkers for triple-negative breast cancer. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 15 (7), 1597–1602 (2019).

Qiu, J. J. et al. Exosomal metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 promotes angiogenesis and predicts poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 14 (14), 1960–1973 (2018).

Liu, H., Chi, Z., Jin, H. & Yang, W. MicroRNA miR-188-5p as a mediator of long non-coding RNA MALAT1 regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis in multiple myeloma. Bioengineered 12 (1), 1611–1626 (2021).

Yan, H. et al. Hu Y.MALAT1 regulates network of microRNA-15a/16-VEGFA to promote tumorigenesis and angiogenesis in multiple myeloma.Carcinogenesis 44 (10–11), 760–772 (2023).

Hirata, H. et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 promotes aggressive renal cell carcinoma through Ezh2 and interacts with miR-205. Cancer Res. 75 (7), 1322–1331 (2015).

Fan, Y. et al. TGF-β-induced upregulation of malat1 promotes bladder cancer metastasis by associating with suz12. Clin. Cancer Res. 20 (6), 1531–1541 (2014).

Li, S. et al. Long non-coding RNA metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 promotes lung adenocarcinoma by directly interacting with specificity protein 1. Cancer Sci. 109 (5), 1346–1356 (2018).

Sun, Q., Hao, Q. & Prasanth, K. V. Nuclear long noncoding rnas: key regulators of gene expression. Trends Genet. 34 (2), 142–157 (2018b).

Yeo, Y. et al. Suh W.FGF12 (Fibroblast growth factor 12) inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hypertension 76 (6), 1778–1786 (2020).

Tian, F., Wang, H., Ma, H., Zhong, Y. & Liao, A. miR-144-3p inhibits the proliferation, migration and angiogenesis of multiple myeloma cells by targeting myocyte enhancer factor 2A.Int. J. Mol. Med. 46 (3), 1155–1165 (2020).

Al-Hawary, S. I. S. et al. Highlighting the role of long non-coding RNA (LncRNA) in multiple myeloma (MM) pathogenesis and response to therapy. Med. Oncol. 41 (7), 171 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. LncRNA NEAT1 promotes gastric cancer progression through miR-17-5p/TGFβR2 axis Up-Regulated angiogenesis. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 705697 (2021).

Macharia, L. W. et al. The genotypic and phenotypic impact of hypoxia microenvironment on glioblastoma cell lines. BMC Cancer. 21 (1), 1248 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Paeoniflorin inhibits angiogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes and zebrafish embryos via the IL-6/STAT3 pathway. Drug. Des. Devel. Ther. 10, 2175–2183 (2016).

Liu, Y. C. et al. Paeoniflorin inhibits angiogenesis and alleviates diabetic retinopathy by regulating VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling pathway. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 1–9 (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. Paeoniflorin inhibits endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis by suppressing VEGF receptor 2 signaling. J. Cell. Biochem. 119 (12), 10164–10174 (2018).

Funding

Our work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.82074348, No. 82274491), the innovation and development joint project of Shandong Province Natural Science Foundation (ZR2023LZL009), and the Jinan clinical medical science and technology innovation plan (No. 202225014, 202328072).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CX conceived and designed this study. WJQ and ZJ collected and prepared the clinical samples. SRJ, YMY, WMY and FJQ performed the experiments. FJQ contributed to statistical and drafted the manuscript. CX provided constructive suggestions for the study. All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All experimental methods were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2020 Ethics Review-KY-010, AWE-2019-038) and the Second Affiliated Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2023 Ethics Review-KY-001).

Consent for publication

All authors have read the manuscript and agreed to publish it and declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, J., Wang, J., Zhang, J. et al. Paeoniflorin inhibits angiogenesis in multiple myeloma by decreasing the MEF2A level to downregulate the expression of lncRNA MALAT1 within exosomes. Sci Rep 16, 588 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30101-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30101-6