Abstract

The erythrocyte-derived extracellular vesicles and nanoerythrosomes show high similarities due to their same origins supporting their prosperous applicability for new generations of nanocarrier systems. By the addition of a representant erythrocyte-membrane lipid which is the saturated dipalmitoyl-phosphocholine (DPPC), different morphological and structural changes occurred in function of the increasing DPPC ratio. The integration of guest DPPC molecules, expressed in weight ratio extending to an order of magnitude, yields the formation of standalone nanoerythrosomes (NERYs), while the integration of DPPC molecules is significantly reduced into red blood cell derived extracellular vesicles (RBCEVs) causing aggregations of these EVs. Despite the induced severe and different changes in morphological and structural characteristics, both systems show systematic changes in spectroscopical signals displaying quasi proportional alterations in their spectroscopical protein to lipid ratios. Sample series with controlled different amount of added lipid (DPPC) provide the observance of the correlation between spectroscopic and stoichiometric protein to lipid ratios. Independently from the selected spectroscopic lipid-determination (regarding to carbon-hydrogen and carbonyl vibrations), a linear relationship was observed between the spectroscopic and stoichiometric ratios in both erythrocyte systems (NERYs, RBCEVs) and the determination of an approximative lipid concentration comes to be possible without any lipid analytic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The majority of the human cells are the micrometre-sized respiratory gas transporter erythrocytes1,2,3. The interfacial region of these red blood cells (RBCs) disposes of all chemical components of structural and organizational units, membrane complexes which are necessary for long circulation, transport, and cell communications in the fluid blood tissues4,5.

The circulating bioreactor erythrocytes permanently inspire the elaboration of new sensor or drug delivery systems for medical purposes, where the active guest molecules are encapsulated into the erythrocytes or attached to their outer surface6,7,8,9. Essentially, the cell-membrane of erythrocytes assure the proper biological, chemical and physical functions, therefore their membrane derived vesicle-like particles have turned into the focus of pharmaceutical-medical interest10,11. The erythrocyte-derived double lipid-walled vesicle-like objects are represented by natural red blood cell extracellular vesicles (RBCEVs) and artificial nanoerythrosomes (NERYs).

The red blood cells produce multivesicular bodies (MVBs) in their one - two-day maturation period from reticulocytes to erythrocytes, then extracellular vesicles (RBCEVs) are released permanently during their 120-day lifespan via shedding of cell membranes12,13. The extracellular vesicles may contain further substances depending on normal and abnormal conditions differently14,15,16,17. Consequently, the determination of all characteristic RBCEV components ─ belonging to carbohydrates, nucleic acids, proteins, lipids, and their metabolic derivates ─ is of paramount importance and recommended in guidelines for extracellular vesicle research by the International Society for EVs (ISEV)18. Especially, the membrane protein and lipid content, and their ratios are informative parameters because these ratios are influenced slightly or severely by the prehistory of active RBCEVs carrying pathological information about the complete human host organism19.

The nanoerythrosomes (NERYs) are obtained from cell-membranes of still living erythrocytes, known as ghosts, by their hypotonic treatment20,21,22. After the consecutive preparation steps, extrusion or sonication, and addition of further substances, the NERYs take on artificial behaviours but preserve their characteristic membrane components whereby these vesicle-like objects proved to be highly biocompatible and suitable for coating other artificial nanoparticles.

The protein and lipid characterization of RBCEVs and NERYs are executed with sophisticated state-of-art apparatuses and commercial analytical methods, too, which are under permanent ameliorations including instrumental and methodical developments with new computational, even artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms using advantages of multimodal approaching23,24,25,26. There is, however, a demand for non-destructive and label-free analytical rapid techniques in the EV research for medical diagnose27. The spectroscopical tools provide the mentioned requirements in a great part, beyond that small sample amounts are needed and relative simple investigations can be carried out in a short time24,28. For the determination of lipid and protein, and their ratios, the Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier-Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) and the Raman spectroscopy are coming into the practice24. Here we focus on the ATR-FTIR method, proposed first by Navarro et al., which proved to be a rapid method based on distinctive characteristic absorption bands of protein and lipid providing qualitative and semi-quantitative information about the EVs main components29,30. For protein identification the intensity of amide I protein band, around 1650 cm− 1, is convenient while for lipid quantification the integrated intensity of C-H stretching vibrations in 3040–2700 cm− 1 or carbonyl (C = O) stretching of lipid-related ester bonds in 1725–1740 cm− 1 are applicable. The spectroscopic protein to lipid ratio, however, suffers from experimental problems, uncertainties in the probed submicron environment because of the heterogeneity in optical density.

The addition of artificial lipids to vesicle-systems is inspired not only to shape their peculiar surface patterns, but also for modifying their size and loading capacities31,32. In this work synthetic phospholipid (DPPC, selected from the characteristic lipid components of ghosts, e.g. phosphatidylcholines PCs, phosphatidylethanolamines PEs, phosphatidylserines PSs, sphingomyelins SMs) was added to erythrocyte derived vesicle-systems to tailor their characteristics. Here, we show the similarities, and deviations as well, in the changes of their morphological and structural features. The creation of series having systematically increased DPPC provided the revelation of the relationship between the spectroscopic and stoichiometric ratios giving a further information for estimation to protein to lipid composition in the study of nanoerythrosomes and extracellular vesicles.

Results

Protein and lipid analyse of erythrocyte cell-membranes (ghost) and extracellular vesicles of erythrocytes (RBCEVs)

Recently, a great number of qualitative and quantitative characteristic data of red blood cell membranes and their derived particles are reported33,34. In case of ghosts, these data are in accordance with our earlier published results, concluding that the skeletal membrane proteins, e.g. Spectrins, Ankyrin and Band-3, are the most abundant protein species in ghosts32. In this work, however, the global, for unique chemical component less sensitive analytical methods are considered to determine the concentration of main components and their ratios. The erythrocyte membrane is composed of approx. 50 weight% protein, and 40 weight% lipid which widely accepted estimation to protein to lipid ratio35,36. For protein and lipid analysis, Bradford, microBCA and SPV assays were used, and the results are summarized in Table 1.

The microBCA method indicates smaller BSA-equivalent values than the Bradford method in both the ghost and the RBCEV samples. For lipids, the Sulfo-Phospho-Vanillin (SPV) assay presents approximately similar concentration value to that of estimated one, based on the value of Bradford assay, and supposing 50:40 proteins to lipids weight ratio. Considering the analytical measured and estimated values, comparable protein to lipid ratios can be derived for ghost sample (P (Bradford assay)/L (SPV assay) = 1.14 and P (Bradford assay)/L(estimated) = 1.25). The analytical assessments indicate that RBCEV sample is more diluted one than ghost. Using the estimated lipid values (0.8×Bradford value), the P/L ratios result in similar composition to that of ghost as P (Bradford assay)/L(estimated) = 1.25. Here, the Bradford and microBCA assays match well, at the same time SPV assay shows significantly smaller value than that calculated by 0.8×Bradford value. So, P (Bradford assay)/L (SPV assay) ratio is high (1.58).

Morphological and structural features of phospholipid (DPPC) containing nanoerythrosomes (NERYs)

The erythrocyte ghost membranes, prepared freshly, show different morphological forms. Beside large sheets, unilamellar nearly spherical vesicle-like objects appear in wide size range, demonstrated in Fig. 1A. The regular spherical forms, known as nanoerythrosomes (NERYs) formed spontaneously, are also frequently observable in the electron-micrographs. The surface of ghosts, and NERYs are speckled with small entities which are membrane proteins and protein aggregates. The gentle ultrasonication induces the disruption of large ghost sheets into smaller ones, while the intensive ultrasonication treatment results in small spherical NERYs and at the same time proteins and protein aggregates of ghosts turn into the medium. As the ultrasonication may influence the ghosts, extrusions of the mixtures of DPPC containing ULV and ghost were used to shape NERYs37. The increase of DPPC to ghost-protein weight ratios, studied at 0.5×, 1×, 2×, 5×, 10× added DPPC, cause significant changes in the surface morphologies of NERYs shown in the freeze-fractured electron-micrographs of representant samples in Fig. 1B, C, D. In case of 1×added DPPC, uniform spherical NERYs are observable in Fig. 1B. The surface pattern and the size-range of particles are like that of the systems having 0.5× and 2× added DPPC, indicating the similar and complete integration of added DPPC molecules into ghost. However, it is worth mentioning, some planar entities, DPPC stacks with protein particles, can also appear occasionally shown by the inset in Fig. 1B. The increased 5× DPPC ratio alters the morphology significantly and beside the standalone NERYs, tightly packed smaller and larger particles are visible (Fig. 1C). Some parts of extra added DPPC are separated and form sheets covering the groups of NERYs. Standalone NERYs do not show regular spherical forms, they exhibit angular shapes with outer surface patterns shown by insets in Fig. 1C. The investigated highest (10×) DPPC ratio results in a more homogeneous morphological formation (Fig. 1D). Typical polygonal-like ─ network of skeletal membrane protein aggregates ─ cover the outer surface of NERYs. Some NERYs are entirely broken through by freeze-fractioning, and the revealed areas how that the inner surfaces are smooth and hardly covered by proteins concluding that “inside out” changes occurred from ghost membrane to NERYs formations, dominantly.

Surface morphology of freeze-fractured ghosts and NERYs observed with electron-microscope. Morphology of ghosts without homogenization (A), NERYs formed from ghosts after 1×DPPC addition and extrusion (B), NERYs formed from ghosts after 5×DPPC addition and extrusion (C), NERYs formed from ghosts after 10×DPPC addition and extrusion (D).

Significant and monotonous changes appear in the small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) one-dimensional patterns of the NERYs and their modified forms, due to the presence of 1×, 2×, 5×, 10× excess DPPC, presented in Fig. 2. The descending character of the beginning section of the curves is the scattering consequence of the whole vesicular objects and their smaller parts, e.g. proteins, protein aggregates, attached to their outer surfaces31,38. The form factor of a phospholipid bilayer, squarely indicative of the presence of bilayer formations, appears in the q ~ 0.5–2 nm− 1 range and centred at q ≈ 1 nm− 1 scattering variable. In the case of small added DPPC ratio, the intensity of the form factor is still significantly reduced while it turns into a more expressed form, when the ratio of added DPPC increased. In case of 10×excess DPPC sample, beside the main peak, two further satellite peaks of bilayer form factor (at q ~ 2, and q ~ 3 nm− 1) appear, approximating the form factor of pure hydrated DPPC system and showing that the bilayers of NERY-10× DPPC system are rich in DPPC (a complete analyse of DPPC ULV system can be seen in39. This observation agrees with our earlier studies where the complex layer thicknesses of the complex unilamellar shell of DPPC loaded NERYs was deduced by completion of ‘2 Gaussian’ model31. The description of the form factor of DPPC loaded NERYs resulted in a wide asymmetrical unilamellar structure (~ 11 nm) composed from an approx. 4 nm thick, in DPPC rich, double bilayer and an outer protein corona, modelled by a third spherical shell.

The ghosts do not undergo significant first order phase transitions in the temperature range between 20 and 50 °C due to the complexity of miscible membrane lipids40. This state also exists in cases of lower ratios of excess DPPC, while the NERY system with 10×excess DPPC indicates the characteristic chain-melting first-order main phase transition to a small extent. This 10×DPPC to NERY ratio can be considered as the highest limit when the guest DPPC molecules can integrate into the host ghost membrane, reported in our earlier works32.

IR spectra of nanoerythrosomes (NERY) and their DPPC loaded forms (NERY-1×DPPC, NERY-2×DPPC, NERY-5×DPPC, NERY-10×DPPC): the C-H stretching bands (A) and the vicinity of the amide I and amide II bands (B). All spectra are normalized to the amide I band intensity. For better visualization, spectra are shifted vertically in panel B.

Turning to spectroscopical study, the intensity of the characteristic -CH2 stretching vibrations of the lipid acyl chains increases with lipid amounts, also accordingly as it is observable in spectra (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, a continuous shift of the positions of the antisymmetric and symmetric -CH2 stretching band is observed, reaching the dominance of typical band positions of pure DPPC (νasCH2 at 2917 cm− 1 and νsCH2 at 2849 cm− 1) at extra 10 × DPPC (in NERY-10×DPPC sample). (IR spectral data of native ghost and NERY are in Supplementary Information S1 the assignations of major bands are summarized in Table S1.) The presence of lipid is further confirmed by increasing of other IR bands, characteristic for DPPC. The sharp band at 1467 cm− 1, related to deformation of methylene groups of lipid acyl chain (δCH2) is not shifted, but the carbonyl stretching of lipid-related ester bonds (νC=O), again, show a continuous displacement, strengthening the incorporation of the DPPC into the parent ghost membrane (IR spectrum of reference pure hydrated DPPC is shown in Supplementary Information S2.)

More drastic effect is observable regarding the amide I and amide II of the native ghost. The amide I is mainly related to carbonyl bands of peptide bonds from protein backbone, while the amide II is a combination of N-H deformation and C-N stretching. Even at the lowest amount of DPPC added, the shift of the amide I peak (from 1653 to 1657 cm− 1) refers to a slight remodelling of protein environment (Fig. 3B). Indeed, the sheet-like conformations are gradually decreasing (indicated by the diminishing shoulder of amide I band at 1635 cm− 1, characteristic of β-sheet secondary structures) and the proportional increase of amide I/amide II band intensities also corroborates the alteration in protein microenvironment.

For further analysis, the integrated intensity of C-H stretching bonds (CH2/CH3) from 3020 to 2800 cm− 1 and that of lipid-related carbonyl (C = O) from 1740 to 1725 cm− 1 were used to calculate spectroscopic quantity. The protein amount was observed by area under amide I band (determined by Gauss fitting).

Correlation between spectroscopic and stoichiometric protein to lipid ratios in nanoerythrosomes (NERYs)

The integrated intensity of protein ─ amide I band provides a solid quantitative determination for the main constituent covering its every conformational forms. The CH2/CH3 vibration intensity, although not strictly characteristic of lipids, because of the same groups the proteins, are proportionally increased as the added DPPC multiplied. The ratio of these integrated intensities gives the spectroscopic ratio in each case having different lipid with added DPPC and the same protein amounts. The probed amounts, their dried but still hydrated forms, vary and produce alterations in the optical density, but the relationship between the amide I and CH2 bands proved to be stable within ± 5–7% despite the uncertainty of the ATR-IR method. The stoichiometric protein to lipid ratios were calculated at every sample by the next formula using the measured protein, estimated lipid concentrations (0.8×Bradford value, shown in Table 1) and the added DPPC amounts:

where \(\:{V}_{sample}\) is volume of the sample, \(\:{m}_{protein}\) is mass of the protein in \(\:{V}_{sample}\), determined by protein assay, \(\:{m}_{membrane\:lipid}\) is mass of natural lipid in \(\:{V}_{sample}\), determined by lipid assay or estimated, \(\:{m}_{added\:DPPC,\:\:i}\) is mass of solid DPPC added systematically to the system.

Plotting the spectroscopic P/L ratios in function of stoichiometric ratios, a semi-linear correlation with \(\:{R}^{2}=0.9667\) value can be obtained by CH2/CH3 lipid determination shown in Fig. 4A. In closer inspection we observed that in case of high amount of added DPPC (e.g. 10×, or 20× excess DPPC) a definite declination occurred from the semi-linear trend. This finding indicates that the dominant presence of one component may change the optical density severely whereby a linear relationship between the spectroscopic and stoichiometric ratios cannot exist in a narrow stoichiometric range close to zero and at significantly over 1. Considering this finding, a better correlation \(\:({R}^{2}=0.9810)\) can be obtained by neglecting the first data belonging to 10×DPPC. In next, we show the spectroscopy ─ stoichiometry correlations in Fig. 4B, when the lipid ratios are expressed by the spectroscopic signal of carbonyl groups of lipid ester. Although this signal is strictly lipid specific, its determination goes with a relative higher error range. Its small value results in a ─ approximately with one magnitude ─ higher P/L values related to that of the P/L values determined by CH2/CH3 bands (Fig. 4/A) and showing a better correlation as it can be observed in Fig. 4B.

Here, we have also used the 0.8×Bradford value for lipid estimation and obtained \(\:{R}^{2}=0.9842\:\)value for the correlation. In case of a higher lipid concentration (3.53 mg/mL), determined by SPV assay, the equation of the correlation lines is slightly changed in both relationships of spectroscopic to stoichiometric ratios and the \(\:{R}^{2}\) values are increase to \(\:0.9847\) and \(\:0.9889\) in cases of CH2/CH3 and C=O considerations, respectively.

Morphological and structural characteristics of phospholipid (DPPC) containing extracellular vesicles (RBCEVs)

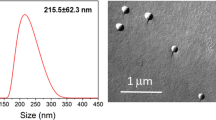

The preparation of RBCEVs results in a more diluted dispersion related to ghost systems and well-dispersed standalone EVs can be observed in freeze-fractured images (Fig. 5A). Spherical nearly monodisperse objects in 100–200 nm size-range appear in electron-micrographs. On their outer surface a considerable number of closely packed proteins, protein aggregates can be observed (inset in Fig. 5A). Noteworthy, the inner surface of RBCEVs is typically smooth and small particles, protein aggregates cannot be revealed in the unilamellar forms broken through entirely. The extra added DPPC perturbs or drastically shapes the morphology of RBCEVs depending on DPPC to proteins of native EVs ratio. 1×added DPPC, similarly to 0.5× and 2×cases, slightly modifies the morphology of RBCEVs; in some cases, elongated vesicles appear instead of spherical forms (Fig. 5B). The surface protein patterns become heterogeneous, and the protein aggregates are visible on the inner surface of EVs (insets in Fig. 5B). Although different creations formed, up to 2×added DPPC range a complete integration of DPPC molecules into RBCEVs can be concluded. 5×DPPC ratio influences the RBCEV-morphology more significantly shown in Fig. 5C. The increased DPPC ratio causes separations in the system, and sheets, rich in DPPC molecules, form elongated particles, or cover and frequently connect the groups of RBCEVs resulting larger aggregates as it is observable in right sided inset of Fig. 5C. A small number RBCEVs are packed in layer or layers causing the formations of oligolamellar creations (left sided inset in Fig. 5C). The high (10×) DPPC ratio results in total changes in the morphology (Fig. 5D). Standalone RBCEVs are hardly observable, unregular groups of particles appear which are covered with extended sheets. Moreover, the laterally extended sheets, certainly periodically packed stacks of lipid bilayers, are separated and do not show the integration with the RBCEVs.

Due to the small concentration of RBCEVs, synchrotron small angle X-ray scattering measurement was necessary to obtain information about the layer structure of these vesicular objects41,42. The scattering patterns of the RBCEVs, having from 0 up to 2×DPPC added lipid, show similar shapes, where the bilayer form factor is centred at q ~ 1 nm− 1, as it can be observed in Fig. 6A. The shapes of the whole scattering curves slightly differ presumably because the added DPPC lipids are integrated into the systems modifying the nanostructures. However, these curves resemble that of NERYs having added DPPC in small ratio, as it was shown in Fig. 2. Significant structural changes can be observed in the further two systems having higher added lipid ratios. RBCEV-5×DPPC system exhibits a diffuse Bragg reflection signal, instead of bilayer form factor, at q ~ 1 nm− 1 scattering variable which indicates the local existence of \(\:d=2\pi\:/q\cong\:6.3\:nm\) periodicity which characteristic for the stacks of fully hydrated DPPC system. Since only the first order appears, DPPC domains, with small sizes and/or oligolamellar arrangements, exist. RBCEV-10×DPPC system already shows Bragg reflections in three orders at q ~ 1, 2, 3 nm−1, displaying \(\:d\cong\:6.3\:nm\) periodicity of multilamellar lipid arrangements. These structural observations fully agree with the morphological observations (Figs. 5C,D) and show the limited integration of added DPPC lipid into RBCEVs which is significantly lower than that in ghost (NERY) systems.

Small angle X-ray patterns of red blood cell derived extracellular vesicles (RBCEV) and their DPPC loaded forms (RBCEV-1×DPPC, RBCEV-2×DPPC, RBCEV-5×DPPC, RBCEV-10×DPPC). For better visualization, the curves of loaded systems are multiplied. (A) DSC curves with chain melting signals of DPPC containing RBCEVs samples. The heat flow values are normalized to the DPPC amounts, clearly showing the significant changes in molar chain melting enthalpy of DPPC (B).

Besides SAXS study, the calorimetrical investigations provide further data about the lack of DPPC integration into RBCEVs in cases of higher DPPC ratios. The chain melting signals are present, which are RBCEVs to DPPC ratio dependent, clearly witnessing about the separation of DPPC domains (Fig. 6B).

IR spectra of erythrocyte-derived extracellular vesicles (RBCEV) and their DPPC loaded forms (RBCEV-1×DPPC, RBCEV-2×DPPC, RBCEV-5×DPPC, RBCEV-10×DPPC): the C-H stretching bands (A) and the vicinity of the amide I and amide II bands (B). All spectra are normalized to the amide I band intensity. For better visualization, spectra are shifted vertically in panel B.

Similarly to NERY, the addition of DPPC to RBCEVs results in increases of typical antisymmetric and symmetric CH2 stretching bands as it is observable in Fig. 7A. We must note, however, that the position of the lipid bands shifts significantly even with very small amounts of DPPC added. This agrees with TEM, SAXS and DSC experiences that in case of high DPPC addition independent lipid layers are formed, sometimes enveloping or packing vesicles indicating the effect of DPPC dominancy on the protein conformation.

Despite that both NERY and RBCEV samples derived from RBC membranes, their composition is not identical. RBCEVs lack cytoskeletal-linked molecules (spectrins, e.g.) and have lower membrane protein content, but they retain residual haemoglobin and metabolic proteins. Moreover, due to their production and their release into extracellular space results in a protein corona. It is interesting to note that there is no shift in typical amide I and amide II protein bands positions in the IR spectra (Fig. 7B). The amide I/amide II ratio is also increasing only for high DPPC ratio where oligolamellar structure, layered lipid formations were detected.

Correlation between spectroscopic and stoichiometric protein to lipid ratios in extracellular vesicles (RBCEVs)

Similarly to NERYs in case of RBCEVs also two kinds of integrated intensities were applied for lipid determination. Consequently, we have obtained two different relationships for spectroscopic and stoichiometric correlation using the previously mentioned calculations.

The spectroscopic P/L ratios in function of stoichiometric ratios exhibits a semi-linear correlation (\(\:{R}^{2}=0.9457)\), based on the asymmetric vibration of C-H bonds for lipid determination, presented in Fig. 8A. When the lipid amounts are expressed by the spectroscopic signal of carbonyl groups of lipids, higher P/L values are obtained, due to the difference of the integral intensities of characteristic functional groups, and another P/L correlation line (\(\:{R}^{2}=0.9948)\:\)is obtained as it observable in Fig. 8B. We must emphasize that the estimated lipid of RBCEVs (0.8×Bradford value) was used for stoichiometric calculations. Using the result of SPV assay, the linear correlations are lower than those in the previous cases (\(\:{R}^{2}=0.9359\) for C-H lipid determination, and \(\:{R}^{2}=0.9945\) for C=O lipid determination) indicating uncertainties with the SPV assay application.

On the level of artificial intelligence, let us the linear correlation acting and fitting the approximate EV-membrane lipid concentration without any lipid analytic (e.g. SPV assay). We can start with close to zero estimated RBCEV lipid amounts in the calculated stoichiometric ratios (marked as \(\:{m}_{membrane\:lipid}\) in the formula). In this case the spectroscopic – stoichiometric data-pairs show a descending trend while the overestimated lipid amounts result in an upward trend. The linear correlation of data-pairs fits with an optimal lipid amount which can be considered as membrane lipid amount of RBCEVs, determined by IR spectroscopy. Executing this procedure, we can obtain the highest correlation (\(\:{R}^{2}=0.9956\)) which determines a lipid concentration of RBCEV = 0.72 mg/mL. This computed value fits well with the estimated value (0.8×Bradford = 0.8×0.89 mg/mL = 0.71 mg/mL). (The change of correlation value in function of the probed virtual lipid amount is presented in Supplementary Information S3.)

The correlations between the spectroscopic and stoichiometric protein to lipid ratios are different in the erythrocyte derivates due to deviations in protein and lipid patterns of the two systems. (The comparison of the correlations for NERY and RBCEV samples is shown in Supplementary Information S4).

Conclusion

The ghosts and their spherical shaped variant, the nanoerythrosomes (NERYs), and red blood cell derived extracellular vesicles (RBCEVs) exhibit similar morphological features. After the addition of a representant erythrocyte-membrane lipid ─ saturated phospholipid (DPPC) ─ different morphological and structural changes occurred in function of the increasing DPPC ratio. The integration of guest DPPC molecules, expressed in weight ratio, extends to an order of magnitude in nanoerythrosomes (NERYs), while the integration of DPPC molecules is significantly reduced into red blood cell derived extracellular vesicles (RBCEVs) indicating a significantly limited possibility to vary these EVs. Apart from the induced changes in morphological and structural characteristics, both systems show systematic changes in spectroscopical signals displaying quasi proportional alterations in their spectroscopical protein to lipid ratios. The study of series with controlled amount of added lipids, providing all advantages of the standard addition method, make possible the revelation of the correlation between spectroscopic and stoichiometric protein to lipid ratios. This correlation is very sound and indicates a linear relationship between the spectroscopic and stoichiometric point-pairs. Even minor changes in laboratorial preparations can cause deviations in the presented relationships, therefore the measurement of a concrete calibration curve is recommended. Moreover, the increase in number of point-pairs is advantageous, especially in a narrow range, close to the stoichiometric ratio = 1, where the added lipid amounts are small values. Independently from the selected spectroscopic lipid-determination (based on C-H or C = O vibrations), a simple approximation can be achieved for the stoichiometric protein to lipid ratio in the knowledge of protein content or in case of its estimation. The proposed correlation line, determined in the case of a representant system, can assure the calibrations curve whereby effects of any perturbations (e.g. change in storage time, milieu, physico-chemical conditions) in stoichiometric ratio and the determination of lipid concentration come to be estimable for other, compositional similar systems, with direct spectroscopical methods.

Experimental

Chemicals

1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (United States). Physiological salt solution (9 g NaCl solved in 991 g Millipore water) was used for erythrocyte isolation and purification. Their membranes were prepared in hypotonic TRIS buffer medium (5.0 mM TRIS, pH: 7.6). The final haemoglobin free erythrocyte membrane, known as ghost, was stored in PBS buffer (10 mM; 8 g NaCl, 0.2 g KCl, 1.8 g Na2HPO4∙2H2O, 0.312 g NaH2PO4∙2H2O for 1 L PBS solution, the final pH = 7.4 value was adjusted by HCl). All listed salts were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (United States).

Ghost and nanoerythrosomes (NERYs) preparation protocols

In preparing the multilamellar vesicle (MLVs), DPPC was mixed with water yielding a homogeneous, concentrated suspension, approximately 15 w/w %. This form was frequently vortexed and homogenised by repeating a heating (50 °C) and cooling (4 °C) cycle twenty times. Finally, it was vortexed and extruded using a Mini Extruder (Avanti Lipids, Al, United States) sequentially through membranes of pore sizes 1000, 400, 200 and finally, 100 nm, forty-one times at each pore size to reach unilamellar vesicles (ULVs).

The preparation of nanoerythrosomes (NERYs) started with ghost preparation. Freshly collected anticoagulated blood was donated by healthy volunteers, 24 ml from one donor at a time using 6 ml K3EDTA tubes (Vacuette, Greiner Bio-One, Austria). The use of human blood samples was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Hungarian Health Scientific Council (ETT TUKEB 6449-2/2019). Cellular components were sedimented from whole blood by centrifugation (2200×g, 15 min, swing-out rotor, 14 mL Eppendorf tube, Hermle Z327 K centrifuge, Germany). The plasma and the white blood cell containing buffy coat were removed and the erythrocyte pellet was suspended in physiological NaCl solution and washed three times. After the last sedimentation, the red blood cells were lysed in hypotonic 5 mM TRIS buffer, stirred in 40× buffer volume below 4 °C. The erythrocyte ghost membrane was sedimented with a Beckman Avanti J-25 I centrifuge (JA-20 rotor, United States, average 34000xg, 30 min, 4 °C). To achieve haemoglobin-free ghosts, the membrane pellet was resuspended in hypotonic TRIS buffer again and centrifuged. Afterwards it was washed in PBS buffer two times and centrifuged (Beckman, Avanti J-25 I centrifuge, average 34000xg, 30 min, 16 °C). The final ghost membrane pellet was suspended in PBS; its protein content was determined by Bradford protein assay and was used as a stock solution for nanoerythrosome (NERY) preparation. The ghost membrane aliquots were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at approx. −80 °C.

For nanoerythrosome preparation the ghost membrane suspension was inserted in a bath sonicator (Elmasonic S10, 30 W) in glass vial for 15 s at the room temperature, with pre-set power level and continuous operation (37 kHz, in 1.5 ml glass vial, sample volume 200 µl). This gently sonicated ghost suspension was mixed with the calculated amount of DPPC (in ULVs form) to reach a final DPPC to protein of ghost weight ratios at desired ratios (0.5:1, 1:1, 2:1, 5:1, 10:1). The mixture was vortexed and extruded using a Mini Extruder (Avanti Lipids, Al, US) sequentially membranes of pore sizes 1000, 400, and finally through 200 nm to obtain homogeneous NERYs.

Red blood cell derived extracellular vesicles (RBCEVs) preparation protocols

RBCEVs were prepared from fresh blood, collected from healthy volunteers into blood collection vacuum tubes containing EDTA anticoagulant (Greiner Bio-One, VACUETTE® TUBE 6 mL K3E K3EDTA). Cellular components were separated by centrifugation (HERMLE Z 327 K, swing-out rotor, 800×g for 15 min at 4 °C): the red blood cells (RBCs, pellet) and plasma (supernatant) were collected separately, while the white blood cell-containing buffy coat was removed. The RBCs underwent washing steps at least three times using 0.9% NaCl physiological saline solution (800×g for 10 min at 4 °C), then a total volume of 3 mL washed RBCs was diluted to 9 mL with PBS and stored at 4 °C for 7 days. Our earlier findings showed that after one week of storage in PBS, predominantly monodisperse EVs were formed43.

RBCEVs were isolated from the supernatant of RBC suspension, by two consecutive centrifugations (HERMLE Z 327 K, swing-out rotor, 1500×g for 10 min and 2850×g for 30 min at 4 °C, respectively). The aliquoted supernatant was than pelleted (Eppendorf 5415R, F45-24-11 rotor, 16000×g for 30 min at 4 °C), and the pellets were resuspended in 0.5 mL of PBS. To escape soluble proteins, a purification step with size exclusion chromatography (SEC) was performed using a 3.5 mL gravity column filled with Sepharose CL-2B gel (17014001, GE Healthcare, Sweden).

Based on the RBCEVs’ protein content, DPPC were quantified corresponding to the desired protein to lipid ratios (1:0.5, 1:1, 1:2, 1:5, 1:10) using a chloroform stock solution. According to the lipid film hydration method44, the solvent was evaporated and the lipid thin films were hydrated with the RBCEV solutions. The resulting suspensions were subjected to ultrasonication for 5 min and extruded, similar to DPPC-ghost mixtures.

Protein quantification by Bradford assay (UV-Vis)

Protein quantification was performed using Bradford colorimetric assay. A standard curve was prepared with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, cat A9418-10G, Sigma-Aldrich) at final concentrations (mg/mL) of 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1 in PBS. 250 µL Bradford reagent (cat B6916-500 mL, Sigma) was mixed with 10 µL of sample in UV-transparent 96-well plate. Absorbance was measured at 595 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Synergy 2 MultiMode Microplate Reader) operated by Gen5 3.11 Software.

Protein quantification by microBCA assay (microBCA)

Protein quantification by microBCA assay was performed using the Micro BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). A standard curve was prepared with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, cat A9418-10G, Sigma-Aldrich) at final concentrations (µg/mL) of 0, 5, 10, 25, 50, 75, 125, 250, 500, 750, 1000, and 1500 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Dulbecco’s PBS (10x), cat PBS-10XA, Capricorn Scientific, diluted to 1x, pH 7.4, 0.2 μm filtered). 50 µl of sample was mixed with 50 µl of working reagent in UV-transparent 96-well plate, after 2 h of incubation at 37 °C absorbance was measured at 562 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Synergy 2 MultiMode Microplate Reader) operated by Gen5 3.11 Software.

Lipid quantification by Sulfo-Phospho-Vanillin assay (SPV)

Lipid content in REV and ghost samples was determined using Sulfo-Phospho-Vanillin (SPV) assay. A DOPC liposome stock solution (1 mg/mL in PBS) was used to prepare a 2-fold serial dilution series, ranging from 16 to 0.25 µg in a final volume of 40 µL. 40 µL standard or sample was mixed with 200 µL of 96% sulfuric acid and incubated at 90 °C for 20 min in a fume hood. Following a 5-minute cooling step at 4 °C, 120 µL of vanillin reagent (prepared in 17% phosphoric acid) was added. A total of 280 µL from the reaction mixture was then transferred to a UV-transparent 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a BioTek Synergy 2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader operated by Gen5 3.11 Software. Lipid concentrations were calculated based on the standard curve.

Transmission electron microscopy combined with freeze fracture (FF-TEM)

Approximately 1 µl droplets of the samples were used for freeze fracturing. The samples were pipetted onto a golden sample holder and rapidly frozen in liquid freon, then put into liquid nitrogen. First etching for 1 min at −110 °C than fracturing was performed at −100 °C in a Balzers freeze-fracture device (Balzers BAF 400D, Balzers AG, Liechtenstein). A replica was made from the fractured surface with vaporized platinum then carbon. The replica was washed with surfactant solution and distilled water, and it was transferred to 200 mesh copper grids for transmission electron microscopic (MORGAGNI 268D, FEI, The Netherlands) examination45.

Small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS)

Small-angle X-ray scattering measurements of NERY samples were performed using CREDO, an in-house transmission geometry set-up46,47. Samples were filled into thin-walled quartz capillaries of 1.2 mm average outer diameter. After proper sealing, these were placed in a temperature-controlled aluminum block, which was inserted into the vacuum space of the sample chamber. Measurements were done using monochromatized and collimated Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.1542 nm wavelength), and the scattering pattern was recorded in the range of 0.2–5.0 nm−1 in terms of the scattering variable, q (q=(4π/λ)sinΘ), where 2Θ is the scattering angle and λ is the X-ray wavelength). The total measurement time was 2.5 h for each sample. To be able to assess sample and instrument stability during the experiment, the exposures were made in 5-minute units, with frequent sample change and reference measurements. These individual exposures were corrected for beam flux, geometric effects, sample self-absorption, and instrumental background, as well as calibrated into physical units of momentum transfer (q, nm−1) and differential scattering cross-section (absolute intensity, cm−1×sr−1). The average of the corrected and calibrated 5-minute scattering patterns was azimuthally averaged to yield a single one-dimensional scattering curve for each sample.

Measurements of RBCEVs were done using monochromatized and collimated radiation of 8 keV photon energy at the SAXS beamline of ELETTRA. The scattering patterns were recorded in the range of 0.1–5 nm−1 in terms of the scattering variable, using a Pilatus 1 M two-dimensional positive sensitive CMOS hybrid pixel detector (Dectris Ltd, Baden, Switzerland). To be able to assess sample stability during the experiment, twenty exposures, each 1 s long, were made and repeated for each sample. The relevant aqueous medium was measured before and after the measurement series. The individual exposures were corrected for beam flux, geometric effects. The background scattering curve was subtracted in the case of the measurements of nanoerythrosomes. The corrected scattering patterns were azimuthally averaged to yield one-dimensional scattering curves for each sample. For the rapid measurements, µDrop system was used to avoid the sedimentation of samples, typically occurred in case of presence of high DPPC concentrations (RBCEV-5×DPPC, RBCEV-10×DPPC).

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

For differential scanning calorimetric experiments, a Setaram µDSC 3 EVO (Lyon, France) apparatus was used. The sample-amounts were typically between 15 and 20 mg, the reference was an empty cell (1000 µL standard Hastelloy vessel). To reduce sampling bias, all samples were heated to 45 °C and the amounts to be measured were taken out from the homogeneous sample-states and were pipetted into the measurement cell. The heating protocol started with an incubation at 10 °C, then followed with four consecutive cycles, from 20 °C to 60 °C and cooling back, with two different scan rates, first a faster 1 °C/min and then a slower 0.5 °C/min one, repeated three times for better resolution. The heating and cooling cycles showed appreciable differences indicating significant kinetic effects during the phase transition courses. In this work the heating cycles were considered for thermodynamical characterization. The heating cycles with slow scan rate have been found similar, the second and third repetition being fully in accordance with each other. The thermograms were deconvoluted by using Calisto Processing v2.14 (AKTS, Switzerland)48.

ATR-infrared spectroscopy

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy using attenuated total reflection technique (ATR-FTIR) was used to characterize the protein and lipid composition of the nanoerythrosomes (NERYs) and extracellular vesicles (RBCEVs). 3 µL of sample was pipetted and dried under mild N2 flow on the top of the diamond ATR element (single reflection Golden Gate accessory, Specac Ltd, UK) fitted into a Varian 2000 FT-IR spectrometer (Varian Inc, USA). Co-addition of 64 individual scans with a nominal spectral resolution of 2 cm− 1 was used for spectrum collection. Protein to lipid ratios were calculated using the integrated intensity of C-H stretching vibration bands (from 3020 cm− 1 to 2800 cm− 1), the integrated intensity of lipid-related carbonyl band (from 1770 to 1700 cm− 1) and the integrated intensity of protein amide I band (around 1650 cm− 1). For the latter we used a Gauss fit to avoid the contribution of any non-vesicular materials like aggregated proteins or amino acids. This approach allows for the exclusion of false values caused by additional band components from amino acids (around 1599 cm⁻¹) and aggregated proteins (around 1620 cm⁻¹)30,31,32. All spectral manipulations were performed using the GRAMS/32 software package (Galactic Inc, USA).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request. Correspondence and requests for these materials should be addressed to A. B. or J.M.

References

Saucedo, L. Red blood cells. In Getting To Know your Cells 7–12 (Springer International Publishing, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-30146-9_2.

De Oliveira, S. & Saldanha, C. An overview about erythrocyte membrane. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 44, 63–74. https://doi.org/10.3233/CH-2010-1253 (2010).

Wickramasinghe, S. & Erber, W. Normal blood cells. In Blood and Bone Marrow Pathology 3–18 (Elsevier, 2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-3147-2.00001-8.

Smith, J. E. Structure, Function, and pathophysiology. Vet. Pathol. 24, 471–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/030098588702400601 (1987).

Daniels, G. Functions of red cell surface proteins. Vox Sang. 93, 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1423-0410.2007.00970.x (2007).

Biagiotti, S., Paoletti, M. F., Fraternale, A., Rossi, L. & Magnani, M. Drug delivery by red blood cells. IUBMB Life. 63, 621–631. https://doi.org/10.1002/iub.478 (2011).

Berikkhanova, K. et al. Drug-loaded erythrocytes: modern approaches for advanced drug delivery for clinical use. Heliyon 10, e23451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23451 (2024).

Villa, C. H., Anselmo, A. C., Mitragotri, S. & Muzykantov, V. Red blood cells: supercarriers for drugs, biologicals, and nanoparticles and inspiration for advanced delivery systems. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 106, 88–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2016.02.007 (2016).

Chen, M. et al. Red blood cells: a potential delivery system. J. Nanobiotechnol. 21, 288. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-023-02060-5 (2023).

GlassmanP.M. et al. Vascular drug delivery using carrier red blood cells: focus on RBC surface loading and pharmacokinetics. Pharmaceutics 12, 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12050440 (2020).

Guido, C. et al. Erythrocytes and nanoparticles: new therapeutic systems. Appl. Sci. 11(5), 2173 (2021).

Stevens-Hernandez, C. J., Bruce, L. J. & Maturation, R. Membranes 12 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes12030311. (2022).

Chiangjong, W., Netsirisawan, P., Hongeng, S. & Chutipongtanate, S. Red blood cell extracellular vesicle-based drug delivery: challenges and opportunities. Front. Med. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.761362 (2021).

Yazdanbakhsh, K., Lomas-Francis, C. & Reid, M. E. Blood groups and diseases associated with inherited abnormalities of the red blood cell membrane. Transfus. Med. Rev. 14, 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1053/tmrv.2000.16232 (2000).

Zhu, K. et al. Hybrid liposome–erythrocyte drug delivery system for tumor therapy with enhanced targeting and blood circulation. Regenerative Biomaterials. 10, rbad045. https://doi.org/10.1093/rb/rbad045 (2023).

Jeppesen, D. K., Zhang, Q., Franklin, J. L. & Coffey, R. J. Extracellular vesicles and nanoparticles: emerging complexities. Trends Cell Biol. 33, 667–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2023.01.002 (2023).

Herrmann, I. K., Wood, M. J. A. & Fuhrmann, G. Extracellular vesicles as a next-generation drug delivery platform. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 748–759. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-021-00931-2 (2021).

Welsh, J. A. et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): from basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicle. https://doi.org/10.1002/jev2.12404 (2024).

Osteikoetxea, X. et al. Improved characterization of EV preparations based on protein to lipid ratio and lipid properties. PLoS ONE. 10, e0121184. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121184 (2015).

Nguyen, P. H. D., Jayasinghe, M. K., Le, A. H., Peng, B. & Le, M. T. N. Advances in drug delivery systems based on red blood cells and their Membrane-Derived nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 17, 5187–5210. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.2c11965 (2023).

Wu, P. et al. Biomimetic recombinant of red blood cell membranes for improved photothermal therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-021-00949-7 (2021).

Lejeune, A. et al. Nanoerythrosome, a new derivative of erythrocyte ghost: Preparation and antineoplastic potential as drug carrier for Daunorubicin. Anticancer Res. 14, 915–919 (1994).

Dybas, J. et al. Trends in biomedical analysis of red blood cells – Raman spectroscopy against other spectroscopic, microscopic and classical techniques. TRAC Trends Anal. Chem. 146, 116481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2021.116481 (2022).

Zini, J. et al. Infrared and Raman spectroscopy for purity assessment of extracellular vesicles. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 172, 106135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2022.106135 (2022).

Di Santo, R. et al. Advancements in Mid-Infrared spectroscopy of extracellular vesicles. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 305, 123346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2023.123346 (2024).

García-Barberán, V., Gómez, M. E., Del Pulgar, H. M., Guamán, A. & Benito-Martin The times they are AI-changing: AI-powered advances in the application of extracellular vesicles to liquid biopsy in breast cancer. Extracell. Vesicles Circ. Nucleic Acids. 6, 128–140. https://doi.org/10.20517/evcna.2024.51 (2025).

Kumar, M. A. et al. Extracellular vesicles as tools and targets in therapy for diseases. Sig Transduct. Target. Ther. 9, 27. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-024-01735-1 (2024).

Soares Martins, T. et al. FTIR spectroscopy and Blood-Derived extracellular vesicles duo in alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Disease. 98, 1157–1167. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-231239 (2024).

Navarro, S., Borchman, D. & Bicknell-Brown, E. Lipid-protein ratios by infrared spectroscopy. Anal. Biochem. 136, 382–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(84)90233-1 (1984).

Mihály, J. et al. Characterization of extracellular vesicles by IR spectroscopy: fast and simple classification based on amide and C H stretching vibrations. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Biomembr. 1859, 459–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.12.005 (2017).

Deák, R. et al. Physicochemical characterization of artificial nanoerythrosomes derived from erythrocyte ghost membranes. Colloids Surf., B. 135, 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.07.066 (2015).

Deák, R. et al. Nanoerythrosomes tailoring: lipid induced protein scaffolding in ghost membrane derived vesicles. Mater. Sci. Engineering: C. 109, 110428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2019.110428 (2020).

Bryk, A. H. & Wiśniewski, J. R. Quantitative analysis of human red blood cell proteome. J. Proteome Res. 16, 2752–2761. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00025 (2017).

Fye, H. K. S. et al. A robust mass spectrometry method for rapid profiling of erythrocyte ghost membrane proteomes. Clin. Proteom. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12014-018-9190-4 (2018).

Platt, D., Aging, B. & Heidelberg blood cells, Rheology, and Berlin, Heidelberg, (1988). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-71790-1

Schenkel-Brunner, H. & Vienna, S. Erythrocyte Membrane, in: Human Blood Groups, Vienna, : pp. 30–53. (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7091-6294-1_4

Bóta, A., Amenitsch, H. & Wacha, A. Lamellarity of ultrasound assisted formations of dipalmitoyl-lecithin vesicles. Ultrason. Sonochem. 112, 107187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2024.107187 (2025).

Guinier, A., Fournet, G., Walker, C. B. & Yudowitch, K. L. Small-angle Scattering of X-rays, Wiley New York, (1955). https://www.eng.uc.edu/~beaucag/Classes/Scattering/Guinier%20and%20Fournet%20SAXS(1955).pdf (accessed October 31, 2024).

Bóta, A. et al. Role of oligo(malic acid) on the formation of unilamellar vesicles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 532, 782–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2018.08.020 (2018).

Matsuki, H., Goto, M., Tada, K. & Tamai, N. Thermotropic and barotropic phase behavior of phosphatidylcholine bilayers. IJMS 14, 2282–2302. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14022282 (2013).

Haider, R. et al. µDrop: a system for high-throughput small-angle X-ray scattering measurements of microlitre samples. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 54, 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1107/s1600576720014788 (2021).

Austrian, S. A. X. S. & Elettra at (2021). https://www.elettra.trieste.it/elettra-beamlines/saxs.html (accessed December 9, 2021).

Bebesi, T. et al. Storage conditions determine the characteristics of red blood cell derived extracellular vesicles. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-04915-7 (2022).

Zhang, H. Thin-Film hydration followed by extrusion method for liposome Preparation. In Liposomes (ed. D’Souza, G. G. M.) 17–22 (Springer New York, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6591-5_2.

Meyer, H. W. & Richter, W. Freeze-fracture studies on lipids and membranes. Micron 32, 615–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-4328(00)00050-0 (2001).

Wacha, A., Varga, Z. & Bóta, A. CREDO: a new general-purpose laboratory instrument for small-angle X-ray scattering. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 47, 1749–1754. https://doi.org/10.1107/s1600576714019918 (2014).

Wacha, A. Optimized pinhole geometry for small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Cryst. 48, 1843–1848. https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600576715018932 (2015).

Marsh, D. Handbook of lipid bilayers 2nd edn (CRC, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1201/b11712

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Ms Teréz Kiss for the FF-TEM experiments and to Dr. András Wacha for laboratorial SAXS measurements.

Funding

The project was supported by the National Research, Development, and Innovation Office of Hungary under grants (K131657; A B., K 131594; J.M. and by the Project no. 2018 − 1.2.1-NKP-2018-00005 (A. B.). A. B. thanks the SAXS beamtime at ELETTRA (Trieste, Italy) in the frame of CERIC-ERIC research panel (proposal id 20212158). The Protein research program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MEDinPROT, A. B.) is acknowledged. The authors thank the support of the Serbian Hungarian Bilateral Research Program (2023 − 1.2.4-TÉT-2023-00119).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.B.; Methodology: A.B., J.M.; Investigation: A. B. (FF-TEM, SAXS, IR, DSC), J. M. (IR, DSC), I.K. (analyses), H. (A) (SAXS) Writing—Original Draft: A.B., J.M.; Visualization: A. (B) (Figures 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6/A, 8, SI 3, SI 4), J. M. (Figures 3 and 6/B, 7, SI 1, SI 2); Writing—review & editing: A. B., J.M., Z. V.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bóta, A., Ilyés, K., Amenitsch, H. et al. Correlation between spectroscopic and stoichiometric protein to lipid ratios in erythrocyte-derived extracellular vesicles and nanoerythrosomes. Sci Rep 16, 606 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30107-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30107-0