Abstract

Lime is an important ingredient in lime concrete, with a carbon content of 0.76 kg CO2/kg. As the global consumption of structural concrete increases, studies are being performed to substitute lime with byproducts such as coconut fibre ash. A collection of waste materials in the form of ash or powder has been recognised to have positive effects on the mechanical properties of concrete and its embodied carbon. However, engineering properties in lime concrete are found to be positively affected by many lime composite materials. While previous studies have made Coir Fibre Ash (CFA) well-known in cementitious material, its potential usage in lime concrete has not yet been explored from a modern applications standpoint. Instead of using the well-established empirical modelling testing approach, such as the further Response Surface Methodology (RSM), the key mechanical characteristics of lime concrete amended with CFA cannot be accurately modelled. This article employs an empirical approach to investigate the impacts of substituting lime with CFA across a range of percentages, including 3%, 6%, 9%, 12%, 15%, and 18% in lime concrete. Compressive strength (CS), flexural strength (FS), splitting tensile strength (STS), and modulus of elasticity (MOE) were investigated as potential outcomes of CFA incorporation into concrete. Embodied carbon was calculated, with RSM applied to refine the model to within a margin of error. Samples were collected at 7, 14, and 28 days. CFA was shown to have a beneficial effect on CS, FS, STS, and MOE up to 6%; however, due to the prevalence of silica dioxide in CFA and the high quantity of CaO in lime, no further improvement was seen beyond that point. Moreover, embodied carbon and eco-strength productivity indicated considerable improvement in modified lime concrete, confirming high sustainability. All the study’s variables were determined to have statistically significant correlations. Concrete’s CS, FS, STS, and MOE may be predicted with great accuracy using just the value of CFA as lime composites, thanks to the findings of a response surface methodology (RSM) followed by an optimization process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Binders are essential components of concrete, one of the most widely used building materials in the world. In most cases, cement is utilised as the binder in concrete, although lime is also often employed because of its inexpensive cost and the delay in setting time it offers1. Limestone rocks are mined for their natural calcite content, which is subsequently refined into a powder for use in building. It’s also a common element in the Earth’s crust2,3. Calcium oxides make up more than 70% of lime and are responsible for its unique binding properties4,5. It may be used in building projects that need just a moderate amount of strength and can save money6. Because of its unique chemical properties and less reliance on industrial processes, its incorporation into building projects is also associated with a lower embodied carbon content than cement7,8. Lime may be used as a binder in concrete; however, even for inexpensive uses, it’s preferable to have a stronger, more long-lasting material9.

In one study, RSM was used to optimize the compressive strength of CFA-modified concrete by varying the percentage of CFA, lime, and water. The results showed that a maximum compressive strength was obtained through a CFA percentage of 5%, lime percentage of 15%, and water-binder ratio of 0.3510. Another study used RSM to explore the flexural strength of CFA-modified concrete by varying the CFA and lime percentages11. The outcomes exhibited that the determined flexural strength was reached with 6% CFA and 14% lime. The outcomes exhibited that a determined modulus of elasticity was reached with 6% CFA, 14% lime, and a water-binder ratio of 0.4. Overall, these studies demonstrate the usefulness of RSM in optimizing the properties of CFA-modified concrete and identifying the optimal mix design of CFA and lime to achieve desired mechanical properties11.

The addition of water to lime triggers a chain reaction known as hydration, which causes the lime and aggregate to bond. Because of its inherent nature, lime drastically lowers concrete’s compressive strength12. To solve this challenge, there is a need to identify both theoretical and practical approaches to replacing lime with materials that have similar or the same effects13. Lime concrete requires a binder concentration of at least 20% to retain its form. Several naturally occurring materials may fall short when compared to lime. It plays a crucial role in scientists’ efforts to find inexpensive ecological materials13,14. Findings from the quest for other materials to reduce concrete’s dependency on lime and make it more ecologically responsive have been positive15. Based on current understanding, researchers are beginning to investigate the topic of environmentally useless garbage7,16. To fortify the sustainability of the lime concrete production and mitigate the environmental damage caused by the sector’s explosive growth in recent decades, owing to the increasing usage of lime, studying naturally existing resources is crucial17. The natural fibre coir is obtained from the coconut husk. It is a kind of plant debris that has dried out sufficiently to be burned18,19. Coir Fibre Ash is the ash left over after the burning of many tons of coir fibre each year, all over the world11,20. Recent studies have shown that agro waste is a plentiful resource that may be used as a CFA because of its lignocellulosic nature21,23,23. Once again, this waste product finds economic use as a lime substitute in the building sector. Historically, the material composition of CFA has suggested qualities that are like those often seen in SCMs.

Multiple studies have shown CFA’s usefulness as a concrete additive. Researchers have observed that including CFA in concrete as an SCM improves the material’s mechanical characteristics. The concrete’s compressive strength improved when CFA was added at concentrations lower than 20%24,25. However, the study regarding the application of CFA in a lime-based concrete remains underexplored, and the advanced methods like Response Surface Methodology, which can help find the best mix, have rarely been utilised for this purpose. The proposed study employed RSM to determine the optimal CFA concentration in lime concrete systematically. Moreover, the environmental consequences of replacing lime with CFA need more in-depth investigation to balance material performance and ecological benefits26,27. To address this, our study employs Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to carefully model and optimise the effect of varying amounts of CFA on the mechanical properties of lime concrete. We aim to find the optimal CFA content that replaces lime without forfeiting strength, develop reliable models that connect mix proportions to performance, and validate these models to ensure their accuracy for practical use. This approach goes beyond simply observing results, providing a predictive framework that supports confident design of environmentally friendly lime concrete.

Sustainability analysis

Sustainability is critically important for concrete as a building material. With the development of technologies, concrete has already received significant attention for its overlooked role in reducing its ecological impact. It is one of the main rationales of existing studies that have utilised CFA along with lime in concrete13,25. Further, the sustainability is linked with the creation of a major impact on expanding the use of CFA as a construction material. Following the objectives of this study and aspects of sustainability, a detailed review was conducted, and its summary is presented in Table 1. The major aspects observed from 20 studies are indicated from the perspective of change in mechanical properties and sustainability of concrete28,29. The existing trends imply that the concrete’s compressive strength, flexural strength, and tensile strength increased with the addition of CFA in variable quantities. The critical aspect of analysis is that it points out the possible outcomes of using CFA in concrete, and when lime is also present in it. It is clearly observed that the concrete involving CFA can bring sustainability. Lime already improves the environmental compatibility of concrete by restoring the cement, and adding CFA can potentially increase the mechanical properties as well11,30,31. It is also observed that none of the studies have used RSM for the development of models for predicting CFA in the presence of lime as a binder. This supports the rationale for this study while also providing the latest overview of research trends indicating positive impacts on concrete mechanical properties and sustainability.

Materials and methods

Material composition and properties

Fine and coarse aggregates met the standards set by ASTM C33-18, and both were sourced regionally51. Lime concrete was made by mixing different amounts of CFA with the lime (3%, 6%, 9%, 12%, 15%, and 18%) during manufacture. It was determined that using less than 3% or more than 20% CFA was not feasible52,53. Compared to previous studies, which often use a 5% or 4% margin of error, a 3% margin of error was used.

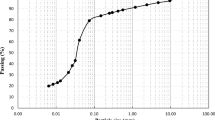

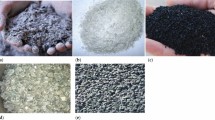

Fine aggregate may be any size between 0.4 and 2.52 mm, whereas coarse aggregate was typically from 10 mm to 30 mm. Air lime (main binding material) was sourced from the local Perak, Malaysian market. Its fineness modulus was 2.92, and its specific gravity was 2.68. Its loss on ignition was 33.5%50,54. Figure 1 shows the treatment of coir fibre ash. The coir fibers were first washed with distilled water, dried at 105 °C for 24 h, and then subjected to controlled burning at 600 °C for 3 h in a muffle furnace to obtain coir fiber ash (CFA). The CFA was ground to pass through a 75 μm sieve before use as a supplementary cementitious material. In Table 2, the chemical makeup of air lime and CFA is shown. The choice of a water-binder ratio of 0.30 indicates that for every unit of binder (in this case, lime), 0.30 units of water were used in the mixture. This fraction is a vital reason in concrete mix design because it completely influences the workability, strength, and endurance of the resulting concrete. The ratio of W/B is usually lower, which in turn increases the strength and durability of concrete. With respect to self-compacting mixtures, it is worth noting that an appropriate water-to-binder (W/B) ratio is crucial, as it helps the mixture flow and fill formwork without requiring excessive vibration. The addition of a water-reducing superplasticiser is a normal procedure in concrete mix design, especially in designing self-compacting properties. Superplasticisers are additives which enhance the workability of lime mortars by ensuring that cement particles disperse, lowering the required water content to ensure sufficient flowability55. This not only improves the self-compacting characteristic of the concrete but also helps to bring down the water-binder ratio. In this study, high-range superplasticizer water-reducing admixtures were employed, e.g. Lignosulfonates (LS). The choice of LS is based on its effectiveness in improving the flow characteristics of concrete blends. The 1.0% plasticizer concentration signifies that 1.0% of the total weight of lime used in the mix was dedicated to the superplasticizer. This concentration is typically determined based on the desired workability and flow characteristics of the concrete mixture. The addition of the superplasticizer at this concentration is intended to reduce the viscosity of the mixture, allowing it to flow more freely and self-compact.

RSM mix design and material proportioning

This research methodology is adopted on the air lime concrete (Air lime as a main binder) made of seven mixtures blended with 0%, 3%, 6%, 9%, 12%, 15% and 18% of CFA as a replacement for lime in the mixture. From seven mixtures, one mixture was prepared with air lime only and the remaining six mixtures were made of different contents of CFA. However, the 1:1.15:3.20 mix ratio with a 0.30 water-binder ratio of lime concrete was used in this research work. Moreover, the three lime concrete experiments were cast for compressive strength (CS), splitting tensile strength (STS) and flexural strength (FS) of lime concrete incorporating many contents of CFA as a substitute for lime in the mixture. Besides, the modulus of elasticity was computed based on compressive strength output at 28 days. Moreover, Response surface methodology (RSM) is a mathematical method for establishing and validating the relationship between independent variables and outcomes56,57. The goal of this study is to find out how the 0%, 3%, 6%, 9%, 12%, 15%, and 18% CFA independent variables affect the mechanical properties of the concrete45,58,59. It involves the following stages: (1) design experimentations using central composite design (CCD), (2) undertake research to gather responses (compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, flexural strength, and modulus of elasticity), (3) establish the RSM mathematical method, and (4) verify the proposed models and optimise the variables. All outcomes were modelled using a central composite surface design with = 1 and a polynomial equation of the second order. A CCD was performed to recommend 13 appropriate experimental trials that were evaluated for their mechanical properties. The type of superplasticizer used was a high-range water reducer, such as Lignosulfonates (LS). Lime concrete with varying concentrations of CFA was experimented with, and its hardened attributes were compared to60,61. Many different RSM formulas exist, each with its own unique CFA to lime to water ratio. Experimenting with various mixes led to the discovery of the reactions62,64,64. Table 3 presents the seven different mix proportions of the concrete samples made for mechanical property testing.

Mixing and testing

Mixing

Lime concrete mixing was performed in accordance with BS 1881 guidelines. Mixing time was 10 min for all the mixes. CA and FA were tested before their use in mixing to optimise the mixing time and use the water content more accurately. Superplasticizer was also considered for adjusting water content because lime already has a high-water requirement in the presence of CFA46,65. All samples underwent standard temperature-controlled water bath curing during the curing process.

Mechanical properties tests

Each lime concrete mix was tested for compressive strength; the size of the mould was 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm, and for split-tensile strength, concrete was molded into cylinders measuring 12 inches in length and 6 inches in diameter. For flexural strength testing, rectangular beams with dimensions of 18 inches in length, 6 inches in width, and 6 inches in height were prepared as samples for each mix.

Seven different mix ratios were made for the compressive strength test, one for each of the following changes in CFA: 3%, 6%, 9%, 12%, 15%, and 18%. The loading pattern was conducted using a universal testing equipment with a 500 kN capability in line with BS 188166. Each sample was tested at 7, 14, and 28 days to assess its compressive strength.

A splitting tensile strength (STS) test was performed using the 500 kN universal testing machine, and with a custom-designed tensile testing arrangement. These cylinders were prepared based on the BS method of enhancing the tensile strength of concrete. To avoid any damage, the loading rate47,67. The tensile behaviour of concrete was adequately evaluated thanks to the testing of the samples for 7, 14, and 28 days.

The ASTM C78 protocol for testing flexural strength was followed. Flexural strength testing was performed by adjusting the testing unit and preparing custom beams for bending68. The study was repeated at 7, 14, and 28 days. Change in embodied carbon and eco-strength effectiveness was also assessed to justify the environmental aspect of using CFA in lime concrete. Experimental setup and testing of samples can be seen in Fig. 2.

Results

Mechanical properties

Compressive strength

As can be seen in Fig. 3, according to the findings of compressive strength testing, the control trial (CL) reaches a compressive strength of 12.00 MPa after 7 days, 16.19 MPa after 14 days, and 23.23 MPa after 28 days. A minimum of 22 MPa is mandatory for structural applications after 28 days of curing for ACI 318. Conversely, up to 6% CFA, increasing the CFA content, enhanced compressive strength. As measured by CFA3L, compressive strength increased by 28.71% between 7 and 14 days and by 74.35% between 14 and 28 days, resulting in a total gain of 124.41% over 28 days. Similarly, CFA6L showed increments of 16.17%, 64.23%, and 90.78% respectively. Lime microstructure is continuously evolving upwards, as seen by the rising tendency48,69,70. Combining the chemical components of CFA with lime boosts its compressive strength. The development of calcium silica hydrate has resulted in a stronger connection between the different components of concrete71,72. The standard error of the manuscript is found to be nearly 0.05, which is significant enough to have a better impact on the accuracy. Maximum compressive strength for CFA9C came in at 24.17 MPa, which is not very outstanding but is still above average. However, when CFA was added to the mix at a concentration of 12%, the concrete’s internal structure was radically changed, rendering it less ductile and unable to handle the load7,19,73. After 7 days, the compressive strength of CFA12L concrete increased by 12.02% at 14 days and showed a further rise of 56.93% at 28 days, resulting in an overall improvement of 75.54% compared to the 7-day strength. This significant early-age strength enhancement at the 7-day mark in CFA12L can be attributed to the finely ground Coir Fibre Ash (CFA), which appears to optimise strength during the initial curing period. However, it’s noteworthy that further increases in CFA content, as seen in CFA15L and CFA18L, did not result in additional improvements in compressive strength. Increasing CFA content introduces higher porosity and weaker particle packing, which possibly leads to a less dense microstructure and reduced load-bearing capacity74. In contrast, when CFA was added at a 6% concentration, an impressive comprehensive strength of 26.90 MPa was achieved. This noticeable strength boost is primarily attributable to the exceptional fineness of CFA particles, surpassing other components in filling the voids within the concrete matrix, particularly up to a 9% CFA content, where it serves as an effective pozzolan. The strength of concrete reduces when additional CFA is included due to the diluting effect of CFA on the lime in concrete11. Waqar et al.11 carry out the same type of finding.

Flexural strength

The use of CFA has been shown in studies to boost flexural strength. Figure 4 shows that the control sample exhibited a progressive rise in flexural strength, with a 21.94% increase from 7 to 14 days, a further 23.53% rise from 14 to 28 days, and an overall improvement of 50.63% between 7 and 28 days. During the 28-day post-curing period, the flexural strength is more than the 3.00 MPa minimum required by ACI. A further study found that there was a proportional increase in flexural strength for every three-percentage-point rise in CFA. The flexural strength of CFA3L increased by 17.55% from 7 to 14 days, followed by a further 28.51% rise between 14 and 28 days, resulting in an overall improvement of 51.06% over the 28 days. The fact that CFA may boost lime concrete’s flexural strength demonstrates that the concrete’s crystalline structure, wherein many of lime’s chemical components were experiencing physical change, has been strengthened. CFA concentrations of 6 per cent had the desired effect on behavior. The flexural strength of CFA9L increased by 20.62% from 7 to 14 days, by 25.21% from 14 to 28 days, giving an overall improvement of 51.03% over 28 days. The inability of either CFA15L or CFA18L to improve the flexural strength of lime concrete indicates a breakdown of the binder. With such a high silica concentration, the CFA has very little opportunity to contribute to the chemical reactions49,75,76. Because lime is also deficient in compounds besides calcium oxide, a significant proportion of silicone dioxide (SiO2) remained in concrete after the lime components had reacted with the whole quantity of calcium10,77,78. Due to CFA9L, the flexural strength of concrete increased from 3.56 MPa after 28 days to 3.62 MPa. The enhancement in strength properties is attributable to the fineness of CFA relative to the lime used to fill the voids left by all the other elements that make up concrete11. The standard error is nearly 0.05, which signifies the acceptability of the results. The reduction in flexural strength monitored following the insertion of 12% Coir Fibre Ash (CFA) in the concrete mixture can be primarily attributed to the highest CFA concentration used. At this level, CFA tends to absorb an excessive quantity of water, resulting in the disposition of a relatively rigid concrete mixture. This excessive water absorption can lead to a suboptimal mixture, characterised by inadequate workability and increased susceptibility to segregation, ultimately contributing to the observed decline in flexural strength. In essence, the imbalance between water content and CFA concentration at this level negatively impacted the mixture’s cohesiveness and, consequently, its flexural strength. The same type of investigation was conducted by Waqar et al.11.

Split tensile strength

Since lime primarily provides compressive binding force, split tensile strength (STS) is lacking in lime concrete. Figure 5 depicts the control sample exhibited a progressive increase in STS, with a 38.94% rise between 7 and 14 days, a further 45.22% improvement between 14 and 28 days, resulting in an overall gain of 101.77% over the 28-day curing period. With an STS of over 1.8 MPa after 28 days of curing, as specified by the ACI, the concrete meets all requirements. It was also shown that the STS dropped with a 3% rise in CFA. The STS of CFA3L increased by 31.96% between 7 and 14 days, followed by an additional 42.97% rise from 14 to 28 days, resulting in an overall improvement of 88.66% over the 28-day curing period. The first thing to note here is that calcium oxide coming from CFA enhances the tensile strength of lime concrete79,80. Lime requires a strong binding force13,27. Conversely, the STS performed with a diminishing trend as the amount of Coir Fibre Ash (CFA) was increased because of a decrease in the binder concentration. STS of CFA6L was the greatest, which was 2.31 MPa in a 28-day curing regime. This occurrence can be ascribed to the interface between CFA and the chemical components of lime during the curing process. CFA serves to reinforce the bond between these components by reacting with them and filling in gaps that may occur as the lime expands during curing. Furthermore, CFA6L’s maximum tensile strength was established, indicating its peak performance under the given conditions. It is of note that the flexural strength of CFA-modified concrete is strongly correlated with tensile strength and compressive strength, with a standard error of 0.05, and the results are also statistically significant, showing a consistent tendency. Moreover, as the CFA replacement percentage increased by 6%, reflecting improved material durability, the STS also exhibited enhancement. Specifically, the STS increased from 2.28 to 2.31 MPa after passing 28 days of exposure to CFA6C in a controlled laboratory setting. This augmentation in STS can be ascribed to the greater specific surface area of CFA associated with cement, allowing it to effectively occupy any remaining voids in the concrete matrix. Importantly, the rise in CFA content may lead to a decrease in the concentration of calcium hydroxide available for product formation due to the consumption of calcium hydroxide by CFA during the chemical reactions that enhance concrete strength.

Modulus of elasticity (MOE)

Elasticity was further quantified by calculating the modulus of elasticity (MOE), which demonstrated that larger MOE values suggested lower flexibility. Strain occurs whenever there is a deformation in the specimen’s shape owing to compression forces44,81,82. The standard error in the results is around 3 GPa, indicating uniformity in all samples and thus significant results. Based on an established pattern in mechanical characteristics, it was discovered that MOE is correlated with compressive strength. The following Eq. 1 was used to determine MOE49.

Additionally, this implies that individuals who consistently experience failures will be a minority with distinct characteristics. As depicted in Fig. 6, after a 28-day curing period, the Modulus of Elasticity (MOE) for CFA6L measures 26.10 GPa. In contrast, the control group exhibited a lower MOE of 24.10 GPa at the same point in time. This remarkable enhancement in MOE can be credited to the higher concentration of calcium oxide (typically exceeding 60%) present in Coir Fibre Ash (CFA). Nonetheless, it’s significant to note that the inclusion of CFA also led to a decrease in the flexibility of the lime concrete, contributing to this effect. It’s important to highlight that MOE did not exhibit an increase with the incorporation of CFA9L, CFA12L, CFA15L, or CFA18L. This may be due to excessive content of CFA, the microstructure being discontinuous, and creating weak zones that fail to distribute load uniformly. This reduces stiffness and results in a lower elastic modulus83. Further, this can be attributed to the limitation in CFA’s reactivity within lime concrete, capped at 6%. While there is some stiffening observed at this level, it is also accompanied by a propensity for more brittle failure, which is a critical consideration in assessing the material’s behavior.

Sustainability assessment

Embodied carbon

Table 4 shows that the embodied carbon factors were taken from the accessible writings for the environmental evaluation of one cubic meter of concrete.

Figure 6 displays the total embodied carbon of each mix, and replacing the substance of lime with CFA (coir fiber ash) has significantly reduced the carbon. According to the findings, replacing lime in concrete with CFA up to 18% decreases the embodied carbon by 4.44%. For all the data samples, the standard error is less than a hundredth of 1, indicating significant results. The net embodied carbon decreased progressively with increasing CFA content, showing reductions of 0.74%, 1.48%, 2.22%, 2.96%, 3.70%, and 4.44% for CFA3%, CFA6%, CFA9%, CFA12%, CFA15%, and CFA18%, respectively, compared to the control mix.

Eco-strength efficiency

The assessment of the eco-strength efficiency of concrete relies on the compressive strength, which is considered a crucial mechanical property of concrete. Equation 2 is used to compute the eco-strength competence of any concrete mixture. According to the findings, it has been found that CFA6% has the highest eco-strength efficiency of 0.05411 MPa/KgCO2/m3. CFA6%, in which 6% of lime is replaced with CFA, is an ideal concrete mix for sustainability, as indicated in Fig. 7. Statistical tolerance (0.005) or errors in the results are not very high, as it is clear from the error bars. Mixes with reduced cement content have extremely greater eco-strength effectiveness compared to the control mix, except CFA12%, CFA15%, and CFA18%.

Correlation analysis

The correlation evaluation was supervised to understand the relativity of data and also to determine the impact of variation done in CFA quantity on the strength characteristics of lime concrete. The most important variables were CS28, FS28, TS28, and ME28, representing the compressive strength, flexural strength, split tensile strength, and modulus of elasticity, respectively. These have significant correlations with the variables causing the changes32,89,90. The following Fig. 8 presents the overall outcomes of the correlation analysis.

It is because of this fact that identifying the correlation as statistically significant is important for confirming the validity of data, strengthening the need for RSM analysis, and confirming the impact of adding CFA to lime concrete at different proportions. The CFA has indicated negative correlations with other variables. A scatter plot matrix is presented in which the linear trend of the data clearly indicates significant results. Values that are away from the linear trend line have a slightly lower correlation, but they still effectively explain the links between variables11,37,91. However, all the correlations observed in the analysis were greater than 0.7. This indicates high acceptability of data from the perspective of analysis92,94,94. The Spearman correlation color map is also presented in Fig. 9. The graph indicates the distribution of correlations in the matrix. The results are satisfactory because the color map shows more significant blocks of data with high correlation. This qualifies the data for RSM analysis and also confirms its validity in terms of having an impact on the change in CFA quantity in lime concrete.

RSM modelling and optimization

RSM and analysis of variance

RSMs may be employed to create response surface models that can then be examined using ANOVA. RSM takes into consideration the mechanical properties of the CFA-modified lime concrete mixtures throughout the modeling and optimization processes. As a result of these results, it is presented (3) through (6) in a coded form. The presented equations in words of the coded elements may be used to produce predictions about the result for a range of values of the relevant independent variables80,95. The magnitude of a factor may be represented as a positive or negative integer, depending on the sign of the factor. By comparing the coefficients, it was found that the encoded Equation faithfully represents the weights of the variables. The results of the ANOVA are shown in Table 5.

Analysis of Variance results are significant as they are performed at the highest acceptable value of confidence, where the 5% probability was only considered in the analysis. Since all of these models had probabilities lower than 0.05, they might be considered significant. The significance measured from the results of RSM indicates the best explanation of variation in dependent variables, which are strength characteristics. The coefficient of regression is highly important in terms of determining the model’s validity. The findings indicate that the data fully fit the model, which ultimately increases its prediction accuracy for all mechanical characteristics of lime concrete59,62. However, a looser fit is indicated by a lower number. The model stability assessment statistics, including R2 values, are shown in Table 6. The R2 values of all four models are rather high (CS: 92.40, STS: 92.40, FS: 94.66, and MOE: 92.48). As a supplementary tool, “Adeq. Precision” provides numerical representations of signal-to-noise ratios. This ratio would perfectly be greater than 4, if possible. Table 6 of the Model Verification Parameters displays the CS, STS, FS, and MOE for an Adeq. Precision of CFA as a lime replacement material was 16.53%, 16.53%, 19.02%, and 16.80%, respectively. If the numbers are indeed huge, the models seem to be rather effective, and they may be used to make predictions of events with some degree of accuracy.

The created response models are evaluated using the plots shown in Figs. 10, 11 and 12, and 13. These plots compare the normalized response to the residual with the actual response to the residual. Visual representations of CS, FS, STS, and MOE metrics for evaluating model quality and adequacy are shown. The estimated values are within reasonable ranges, and the graphs are consistent46,63. A residual range of minus two to plus two is acceptable96,98,99,99. Many of the values are also within the desirable range, as shown in Fig. 9a. On the other hand, in Fig. 9b, the data points are more dispersed, but the overall pattern remains straight. The importance of the connection between the normal and predicted plots helps clarify the capability of the response model in CS. Alike patterns can be seen in Figs. 11a, b, 12a, b, and 13a, b, demonstrating that the response models of FS, STS, and MOE meet minimum requirements.

Optimization

Finding the appropriate values for each variable is a challenge when building response models using RSM. This led to the independent variable in the model being optimized. Objective functions in optimization provide targets for variables and their relative significance52. The analogous procedure was used to get the best possible number between zero and one. With an increasing desirability value, the response objective function yields more desirable results, and the enhanced consequences increasingly matter in establishing the dependent variable. Table 7 presents examples of optimization tasks6,89,100. Clearly, the aims of optimization vary across dependent variables, and this is reflected in the outcomes of lime concrete combined with CFA as lime replacement material. Responses are maximized in CS and FS, while they are minimized in STS and MOE via the optimization process. For the optimization system to find the optimal answer, it must be given the conditions for success. A similar procedure was used to determine the optimal number between zero and one50,53,60. Figure 14 shows a ramp of the optimal solution. Maximum values for CS and the FS were 34.94 and 5.56, respectively, after using the optimization technique79,101. There are a minimum acceptable STS and MOE of 3.42 and 29.60, respectively. Figure 15 illustrates how the 95.20% desirable results imply highly applicable outcomes even though there is some variation in the model and response method. The optimization approach led to the intended results (Fig. 16).

It was important to determine the accuracy of optimization results in the practical context. Therefore, a short experimentation process was followed in which the guessed assessments were matched with trial results involving CFA at an adequate percentage obtained from the model102. The rest of the results are presented in Table 8 below, and the equation used is based on the differentiation of experimental and predicted values.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study supports constructive intuitions into the use of CFA as a supplement to lime-based concrete. The addition of CFA has been shown to boost the mechanical properties of lime concrete, with Mix CFA6C containing 6% CFA demonstrating the greatest improvements.

-

Among the various mixtures tested, Mix CFA6C, containing 6% CFA, exhibited the most substantial enhancements in mechanical properties.

-

The correlation analysis and regression coefficient affirm the reliability and precision of the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) model in predicting the mechanical properties of CFA-modified lime concrete. The standard deviation falls within acceptable ranges, reinforcing the validity of the results.

-

It is examined that extreme percentages of CFA can adversely affect the internal structure of lime concrete, diminishing its binding characteristics. However, up to 6% CFA incorporation is sustainable and contributes to increased concrete rigidity, as evident from the rise in MOE.

-

These findings hold expressive consequences for the progression of sustainable building practices and offer opportunities for cost optimization in lime concrete formulations with CFA supplementation.

-

The study contributes novel insights by examining the relationship between CFA and lime content, particularly over the 7, 14, and 28-day curing periods in CFA-modified lime concrete.

-

The RSM model demonstrates remarkable accuracy in forecasting the mechanical attributes of lime concrete with CFA, and experimental verification underscores the result’s validity, with an error rate below 5%.

-

The research underscores the effective decline in embodied carbon and the enhancement of eco-strength effectiveness in CFA-modified lime concrete, highlighting the sustainability potential of CFA utilization in lime concrete.

-

In summary, this study advances the understanding of CFA’s role in sustainable construction practices and underscores the prospects for further exploration in this field.

Limitations

Although the RSM used in this examination is beneficial with good insights, the method does have some limitations that should be mentioned. One is that RSM is responsive to experimental differences such as environment and precision of measurement. The accuracy of the model on such factors could be influenced by minor deviations in them. Second, RSM presupposes that the factors and responses are linearly related in the experiment design space. Alternatively, in practice, the non-linear interaction can be present, which can also weaken the accuracy of the model in its predictions. In addition, the use of RSM is more or less limited within the experimental range under investigation. The data should be cautious in extrapolating the predictions over the tested regions because the accuracy of the model decreases in extrapolated regions. The success of RSM also hinges on the careful selection of input factors, and neglecting crucial variables can result in incomplete models. Lastly, conducting experiments for RSM can be resource-intensive in terms of time and materials. Such limitations can be contemplated when utilizing RSM in further research and real-life applications: the results should be interpreted appropriately.

Recommendations

-

Further research should explore the potential of Coir Fibre Ash (CFA) in lime concrete beyond the studied range. Investigating the effects of CFA percentages above 18% and below 3% can provide insights into the optimal CFA content for various construction applications.

-

Given the potential non-linear interactions in lime concrete with CFA, future studies may benefit from employing non-linear modeling techniques. This approach can better capture complex relationships between variables, enhancing the accuracy of predictions.

-

Extend testing to longer curing periods, such as 60 or 90 days, to evaluate the long-term outcomes of CFA on lime concrete’s mechanical properties. This can provide valuable data for projects with extended construction timelines.

-

Evaluate the broader environmental impact of CFA-modified lime concrete, including life cycle assessments and embodied energy calculations. This can quantify the sustainability benefits in terms of reduced carbon emissions and resource conservation.

-

Conduct field trials and case studies to validate the laboratory findings in real construction scenarios. Measure the workability, durability, and functioning of CFA-modified lime concrete in actual building projects to ensure its practical feasibility.

-

These recommendations aim to guide future research and application of CFA in lime concrete, contributing to more sustainable and efficient construction practices.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author through the email address [mohsen.alawag@taiz.edu.ye].

References

Onyelowe, K. C. et al. Estimating the strength of soil stabilized with cement and lime at optimal compaction using ensemble-based multiple machine learning. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 15308. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66295-4 (2024).

Kavya, H. M. et al. Effect of coir fiber and inorganic filler on physical and mechanical properties of epoxy based hybrid composites. Polym. Compos. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.26103 (2021).

Ahmad-Lone, I. & Bawa, E. A. Utilization of fly-ash and coir fibre in soil reinforcement. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 6, 488 (2018).

Wang, B., Yan, L. & Kasal, B. A review of coir fibre and coir fibre reinforced cement-based composite materials (2000–2021). J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130676 (2022).

Navrátilová, E., Tihlaříková, E., Neděla, V., Rovnaníková, P. & Pavlík, J. Effect of the preparation of lime putties on their properties. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 17260. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17527-3 (2017).

Peng, J., Feng, Y., Zhang, Q. & Liu, X. Multi-objective integrated optimization study of prefabricated building projects introducing sustainable levels. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 2821. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29881-6 (2023).

Syed, M., GuhaRay, A. & Garg, A. Performance evaluation of lime, cement and alkali-activated binder in fiber-reinforced expansive subgrade soil: A comparative study. J. Test. Eval. https://doi.org/10.1520/JTE20210054 (2021).

Venkatachalam, G. et al. Investigation of tensile behavior of carbon nanotube/coir fiber/fly ash reinforced epoxy polymer matrix composite. J. Nat. Fibers https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2022.2148151 (2023).

Haik, R., Bar-Nes, G., Peled, A. & Meir, I. A. Alternative unfired binders as lime replacement in hemp concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117981 (2020).

Banzibaganye, G., Twagirimana, E. & Kumaran, G. S. Strength enhancement of silty sand soil subgrade of highway pavement using lime and fines from demolished concrete wastes. Int. J. Eng. Res. Afr. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/JERA.36.74 (2018).

Waqar, A. et al. Effect of coir fibre ash (CFA) on the strengths, modulus of elasticity and embodied carbon of concrete using response surface methodology (RSM) and optimization. Results Eng. 17, 100883. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RINENG.2023.100883 (2023).

Li, J., Sun, Q., Zhai, D., Zu, Y. & Zhang, Q. Influence of the mass percentage of binders on the properties of LHC. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 27143. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78638-2 (2024).

Vashistha, P., Oinam, Y., Shi, J. & Pyo, S. Application of lime mud as a sustainable alternative construction material: A comprehensive review of approaches. J. Build. Eng. 87, 109114. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOBE.2024.109114 (2024).

Aziz, A. et al. Enhancing sustainability in self-compacting concrete by optimizing blended supplementary cementitious materials. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 12326. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62499-w (2024).

Garcia-Troncoso, N., Xu, B. & Probst-Pesantez, W. Development of concrete incorporating recycled aggregates, hydrated lime and natural volcanic pozzolan. Infrastructures https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures6110155 (2021).

Tan, T., Huat, B. B. K., Anggraini, V., Shukla, S. K. & Nahazanan, H. Strength behavior of fly ash-stabilized soil reinforced with coir fibers in alkaline environment. J. Nat. Fibers https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2019.1691701 (2021).

Yadav, J. S. & Tiwari, S. K. Behaviour of cement stabilized treated coir fibre-reinforced clay-pond ash mixtures. J. Build. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2016.10.006 (2016).

Nitish, S. S. S., De, S., Ramya, A. V. S. L. & Kumar, G. S. Comparative study on soil stabilization using industrial by products and coconut coir. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2040/1/012014 (2021).

Sharma, M. & Kumar, A. Soil stabilization using rice husk ash and coir fibre. Int. J. Innov. Res. Eng. Manag. https://doi.org/10.55524/ijirem.2022.9.4.13 (2022).

Kodicherla, S. P. K. & Nandyala, D. K. Influence of randomly mixed coir fibres and fly ash on stabilization of clayey subgrade. Int. J. Geo-Eng. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40703-019-0099-1 (2019).

Hasan, K. M. F., Horváth, P. & Alpar, T. Lignocellulosic fiber cement compatibility: A state of the art review. J. Nat. Fibers 19, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2021.1875380 (2021).

Rahim, M., Douzane, O., Tran-Le, A. D., Promis, G. & Langlet, T. Characterization and comparison of hygric properties of rape straw concrete and hemp concrete. Constr. Build Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.11.021 (2016).

Brose, A., Kongoletos, J. & Glicksman, L. Coconut fiber cement panels as wall insulation and structural diaphragm. Front. Energy Res. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2019.00009 (2019).

Kamaruddin, F. A., Anggraini, V., Huat, B. K. & Nahazanan, H. Wetting/drying behavior of lime and alkaline activation stabilized marine clay reinforced with modified coir fiber. Materials 13(12), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13122753 (2020).

Guruswamy, K. P. et al. Coir fibre-reinforced concrete for enhanced compressive strength and sustainability in construction applications. Heliyon 10(21), e39773. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2024.E39773 (2024).

Kazemi, R. & Mirjalili, S. An AI-driven approach for modeling the compressive strength of sustainable concrete incorporating waste marble as an industrial by-product. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 26803. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77908-3 (2024).

Vaičiukynienė, D. et al. Production of an eco-friendly concrete by including high-volume zeolitic supplementary cementitious materials and quicklime. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 188. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50761-6 (2024).

Wang, L., Lenormand, H., Zmamou, H. & Leblanc, N. Effect of variability of hemp shiv on the setting of lime hemp concrete. Ind. Crops Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113915 (2021).

Sáez-Pérez, M. P., Brümmer, M. & Durán-Suárez, J. A. Effect of the state of conservation of the hemp used in geopolymer and hydraulic lime concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122853 (2021).

Boobalan, S. C. & Sivakami-Devi, M. Investigational study on the influence of lime and coir fiber in the stabilization of expansive soil. Mater. Today Proc. 60, 311–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MATPR.2022.01.230 (2022).

Pederneiras, C. M., Veiga, R. & de Brito, J. Physical and mechanical performance of coir fiber-reinforced rendering mortars. Materials 14(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14040823 (2021).

Pereira, C. L. et al. Use of highly reactive rice husk ash in the production of cement matrix reinforced with green coconut fiber. Ind. Crops Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.04.038 (2013).

Lejano, B. et al. Experimental investigation of utilizing coconut shell ash and coconut shell granules as aggregates in coconut coir reinforced concrete. Clean. Eng. Technol. 21, 100779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clet.2024.100779 (2024).

Adekunle, A., Funmi, F. & Williams, O. Feasibility of using coconut fibre to improve concrete strength. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 11, 98–103 (2022).

Ahmad, W. et al. Effect of coconut fiber length and content on properties of high strength concrete. Materials https://doi.org/10.3390/MA13051075 (2020).

Ann-Adajar, M. et al. Compressive strength and durability of concrete with coconut shell ash as cement replacement. Int. J. Geomate 17, 183–190. https://doi.org/10.21660/2020.70.9132 (2020).

Khan, N., Sutanto, M. H., Khan, I., Khahro, S. H. & Malik, M. A. Optimizing coconut fiber-modified hot mix asphalt for enhanced mechanical performance using response surface methodology. Sci Rep 15(1), 15098. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98234-2 (2025).

Wu, C. Research on flexural mechanical properties and mechanism of green ecological coir fiber foamed concrete (CFFC). Sci Rep 14(1), 17105. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67137-z (2024).

Alenezi, D. et al. Strength and water absorption behavior of untreated coconut fiber-reinforced mortars: Experimental evaluation and mix optimization. Constr. Mater. 5(3), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater5030069 (2025).

Wang, B., Yan, L. & Kasal, B. Long-term Pull-out behavior of coir fiber from cementitious material with statistical and microstructural analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 385, 131533. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CONBUILDMAT.2023.131533 (2023).

Ahmed, M., Khan, S., Bheel, N., Awoyera, P. O. & Fadugba, O. G. Developing high-performance low-carbon concrete using ground coal bottom ash and coconut coir fibre. Results Eng. 27, 106607. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RINENG.2025.106607 (2025).

Nawab, M. S. et al. A study on improving the performance of cement-based mortar with silica fume, metakaolin, and coconut fibers. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e02480. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CSCM.2023.E02480 (2023).

Tang, V. L., Vu, K. D., Dang, V. P., Nguyen, T. N. L. & Nguyen, D. T. Mechanical properties of building mortar containing pumice and coconut-fiber. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 982, 648–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19756-8_61 (2020).

Zaid, O. et al. A step towards sustainable glass fiber reinforced concrete utilizing silica fume and waste coconut shell aggregate. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 12822. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92228-6 (2021).

Singh, C. P. et al. Fabrication and evaluation of physical and mechanical properties of jute and coconut coir reinforced polymer matrix composite. Mater. Today Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.07.684 (2020).

Praveen, G. V. & Kurre, P. Influence of coir fiber reinforcement on shear strength parameters of cement modified marginal soil mixed with fly ash. Mater. Today Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.08.238 (2020).

Raj, B., Sathyan, D., Madhavan, M. K. & Raj, A. Mechanical and durability properties of hybrid fiber reinforced foam concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118373 (2020).

ShadheerAhamed, M., Ravichandran, P. & Krishnaraja, A. R. Natural fibers in concrete: A review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1055(1), 012038. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/1055/1/012038 (2021).

Pederneiras, C. M., Veiga, R. & de Brito, J. Physical and mechanical performance of coir fiber-reinforced rendering mortars. Materials https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14040823 (2021).

Ige, O. & Danso, H. Experimental characterization of adobe bricks stabilized with rice husk and lime for sustainable construction. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)mt.1943-5533.0004059 (2022).

ASTM C33/C33M—18. Standard Specification for Concrete Aggregates ASTM C33/C33M—18, in Annual Book of ASTM Standards (2018).

Murthi, P., Poongodi, K., Gobinath, R. & Saravanan, R. Evaluation of material performance of coir fibre reinforced quaternary blended concrete. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/872/1/012133 (2020).

Balagopal, V. & Viswanathan, T. S. Evaluation of mechanical and durability performance of coir pith ash blended cement concrete. Civ. Eng. Arch. https://doi.org/10.13189/cea.2020.080529 (2020).

Akhtar, M. E. & Elavenil, S. experimental study on coir blended concrete strengthened with fly-ash and granite powder. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 13, 8402 (2018).

Silva, B., Ferreira Pinto, A. P., Gomes, A. & Candeias, A. Fresh and hardened state behaviour of aerial lime mortars with superplasticizer. Constr. Build. Mater. 225, 1127–1139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.07.275 (2019).

Rezaifar, O., Hasanzadeh, M. & Gholhaki, M. Concrete made with hybrid blends of crumb rubber and metakaolin: Optimization using response surface method. Constr. Build. Mater. 123, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.06.047 (2016).

Mohammed, B. S. et al. Deformation properties of rubberized engineered cementitious composites using response surface methodology. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 45(2), 729–740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-020-00444-3 (2021).

Das, S. K. et al. Fresh, strength and microstructure properties of geopolymer concrete incorporating lime and silica fume as replacement of fly ash. J. Build. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101780 (2020).

Bumanis, G., Vitola, L., Pundiene, I., Sinka, M. & Bajare, D. Gypsum, geopolymers, and starch-alternative binders for bio-based building materials: A review and life-cycle assessment. Sustainability https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145666 (2020).

NarasimhaSwamy, P. A. N. V. L., VenuGopal, U. & Prasanthi, K. Experimental study on coir fibre reinforced flyash based geopolymer concrete with 12m & 10m molar activator. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 8, 2210 (2017).

Keerthi, M. & Prasanthi, K. Experimental study on coir fibre reinforced fly ash based geopolymer concrete for 10M. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 8, 464 (2017).

Ada, A. M. O. et al. Hygrothermal performance of hemp lime concrete embedded with phase change materials for buildings. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2069/1/012005 (2021).

Sharma, S. & Singh, J. Impact of partial replacement of cement with rice husk ash and proportionate addition of coconut fibre on concrete. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol. 8, 1806 (2017).

Ebrahimi-Besheli, A., Samimi, K., Moghadas-Nejad, F. & Darvishan, E. Improving concrete pavement performance in relation to combined effects of freeze–thaw cycles and de-icing salt. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122273 (2021).

Grist, E. R., Paine, K. A., Heath, A., Norman, J. & Pinder, H. Innovative solutions please, as long as they have been proved elsewhere: The case of a polished lime-pozzolan concrete floor. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2014.01.001 (2014).

BS:1881-1983: Part 122. BS 1881-122-(1983)-Testing concrete-Method for determination of water absorption. British Standard (2009).

Garikapati, K. P. & Sadeghian, P. Mechanical behavior of flax-lime concrete blocks made of waste flax shives and lime binder reinforced with jute fabric. J. Build. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101187 (2020).

ASTM International. ASTM C78. Annual Book of ASTM Standards (2010).

Walker, R. & Pavía, S. Moisture transfer and thermal properties of hemp-lime concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.04.081 (2014).

Strandberg-de Bruijn, P. & Johansson, P. Moisture transport properties of lime-hemp concrete determined over the complete moisture range. Biosyst. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2014.03.001 (2014).

Zerrouk, A., Lamri, B., Vipulanandan, C. & Kenai, S. Performance evaluation of human hair fiber reinforcement on lime or cement stabilized clayey- sand. Key Eng. Mater. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.668.207 (2016).

Sathiparan, N., Rupasinghe, M. N. & Pavithra, B. H. M. Performance of coconut coir reinforced hydraulic cement mortar for surface plastering application. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.03.058 (2017).

Kamaruddin, F. A. B., Huat, B. B. K., Anggraini, V. & Nahazanan, H. Modified natural fiber on soil stabilization with lime and alkaline activation treated Marine Clay. Int. J. Geomate https://doi.org/10.21660/2019.58.8156 (2019).

Nurfais, H., Affandy, N. A. & Nabilah, S. Effect of substitution of coconut coir waste on the compressive strength of non-structural concrete. Teknika Jurnal Sains dan Teknologi. 17, 183–190. https://doi.org/10.36055/tjst.v17i2.11443 (2021).

Mohammadifar, L. et al. Properties of lime-cement concrete containing various amounts of waste tire powder under different ground moisture conditions. Polymers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14030482 (2022).

Anggraini, V., Asadi, A., Farzadnia, N., Jahangirian, H. & Huat, B. B. K. Reinforcement Benefits of nanomodified coir fiber in lime-treated marine clay. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)mt.1943-5533.0001516 (2016).

Awodiji, C. T. G. & Onwuka, D. O. Re-investigation of the compressive strength of ordinary Portland cement concrete and lime concrete. Int. J. Geol. Agric. Environ. Sci. 4, 12 (2016).

Grist, E. R., Paine, K. A., Heath, A., Norman, J. & Pinder, H. Structural and durability properties of hydraulic lime-pozzolan concretes. Cem. Concr. Compos. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2015.07.001 (2015).

Prasad, D., Pandey, A. & Kumar, B. Sustainable production of recycled concrete aggregates by lime treatment and mechanical abrasion for M40 grade concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121119 (2021).

Hake, S. L., Damgir, R. M. & Patankar, S. V. Temperature effect on lime powder-added geopolymer concrete. Adv. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6519754 (2018).

Gerges, N. N., Issa, C. A., Khalil, N. J. & Aintrazi, S. Effects of recycled waste on the modulus of elasticity of structural concrete. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 16189. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65516-0 (2024).

Wang, Z., Bai, E., Xu, J., Du, Y. & Zhu, J. Effect of nano-SiO2 and nano-CaCO3 on the static and dynamic properties of concrete. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 907. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04632-7 (2022).

Königsberger, M. & Staquet, S. Micromechanical multiscale modeling of ITZ-driven failure of recycled concrete: Effects of composition and maturity on the material strength. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8060976 (2018).

Hammond, G. & Jones, C. The Inventory of Carbon and Energy (ICE). A BRIA guide Embodied Carbon (2014).

Robati, M. & Oldfield, P. The embodied carbon of mass timber and concrete buildings in Australia: An uncertainty analysis. Build. Environ. 214, 108944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.108944 (2022).

Thilakarathna, P. S. M. et al. Embodied carbon analysis and benchmarking emissions of high and ultra-high strength concrete using machine learning algorithms. J. Clean. Prod. 262, 121281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121281 (2020).

Kumar, R., Shafiq, N., Kumar, A. & Jhatial, A. A. Investigating embodied carbon, mechanical properties, and durability of high-performance concrete using ternary and quaternary blends of metakaolin, nano-silica, and fly ash. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28(35), 49074–49088. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-13918-2 (2021).

Zhu, H., Zhang, D., Wang, T., Wu, H. & Li, V. C. Mechanical and self-healing behavior of low carbon engineered cementitious composites reinforced with PP-fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 259, 119805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119805 (2020).

Acharya, P. K. & Patro, S. K. Use of ferrochrome ash (FCA) and lime dust in concrete preparation. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.05.042 (2016).

Shambharkar, R. et al. Utilization of fly ash & coir fiber in manufacturing of paver blocks. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Comput. 11, 27967 (2021).

Ganesan, S., OthumanMydin, M. A., MohdYunos, M. Y. & MohdNawi, M. N. Thermal properties of foamed concrete with various densities and additives at ambient temperature. Appl. Mech. Mater. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.747.230 (2015).

Haik, R., Peled, A. & Meir, I. A. The thermal performance of lime hemp concrete (LHC) with alternative binders. Energy Build https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2019.109740 (2020).

Bakis, A. The usability of pumice powder as a binding additive in the aspect of selected mechanical parameters for concrete road pavement. Materials https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12172743 (2019).

Haik, R., Peled, A. & Meir, I. A. Thermal performance of alternative binders lime hemp concrete (LHC) building: comparison with conventional building materials. Build. Res. Inf. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2021.1889950 (2021).

Grist, E. R., Paine, K. A., Heath, A., Norman, J. & Pinder, H. The environmental credentials of hydraulic lime-pozzolan concretes. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.01.047 (2015).

Bheel, N. et al. Utilization of millet husk ash as a supplementary cementitious material in eco-friendly concrete: RSM modelling and optimization. Structures 49, 826–841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.02.015 (2023).

Waqar, A. et al. Effect of volcanic pumice powder ash on the properties of cement concrete using response surface methodology. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41024-023-00265-7 (2023).

Khan, O. et al. Optimization of fresh and mechanical characteristics of carbon fiber-reinforced concrete composites using response surface technique. Buildings 13(4), 852 (2023).

Bheel, N. et al. Effect of calcined clay and marble dust powder as cementitious material on the mechanical properties and embodied carbon of high strength concrete by using RSM-based modelling. Heliyon 9, e15029 (2023).

Mileto, C. & López-Manzanares, F. V. Lime-based concrete and tile vaults during the valencian middle ages: Continuity and constructive evolution. Archeologia dell’Architettura https://doi.org/10.36153/aa25.2020.01 (2020).

Courard, L., Degée, H. & Darimont, A. Effects of the presence of free lime nodules into concrete: Experimentation and modelling. Cem. Concr. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2014.06.005 (2014).

Madrid, M., Orbe, A., Carré, H. & García, Y. Thermal performance of sawdust and lime-mud concrete masonry units. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.02.193 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2024-253).

Funding

This research was funded by Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia, Project No. (TU-DSPP-2024-253).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: N.S.Z., N.S.; Methodology: N.S.Z.; Formal analysis: A.W., A.O.B.; Investigation: M.A., A.M.A., N.S.Z.; Data curation: A.M.A., A.M.A.; Writing—Original draft: N.S., A.O.B.; Writing—review and editing: M.A., A.W., A.O.B.; Supervision: M.A., H.A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zada, N.S., Shafiq, N., Waqar, A. et al. Engineering attributes of coir fibre ash incorporated sustainable lime concrete. Sci Rep 15, 45623 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30132-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30132-z