Abstract

This study examined how parents’ attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) tendencies, boredom proneness, and parenting styles are associated with their children’s ADHD tendencies and boredom proneness, which have been scarcely studied empirically. Middle-class individuals aged 30–50 years with children in the first-to-third year of elementary school were recruited, and data from 301 parent–child pairs were analyzed. Parents reported their own ADHD tendencies, boredom proneness, and parenting styles, as well as their child’s ADHD tendencies, boredom levels, and academic performance. Data on parents’ educational background and income levels were also collected as supplementary information. Mothers’ and fathers’ ADHD tendencies, boredom proneness, and parenting styles were differentially associated with their children’s ADHD tendencies and boredom proneness. High ADHD tendencies in children were effectively explained by maternal responsiveness. Additionally, paternal responsiveness interacted with a child’s ADHD, significantly increasing the child’s boredom level, while maternal control appeared to have an inhibitory effect on boredom. This was among the first to demonstrate the influence of parental variables on children’s ADHD tendencies and boredom proneness. These findings contribute to a better understanding of how parental factors are associated with children’s ADHD tendencies and boredom proneness, and may help inform coping strategies for children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and boredom proneness have both been recognized as important factors influencing childhood mental health and cognitive development1,2,3. Recent studies suggest a conceptual and behavioral overlap between the two constructs, particularly in their shared associations with low sustained attention, impulsivity, and difficulty with goal-directed behavior4,5,6. Both ADHD and a heightened tendency toward boredom may shape children’s academic trajectories, social functioning, and long-term developmental outcomes7,8,9. Despite increasing interest in these traits among adults, relatively little is known about how ADHD tendencies and boredom proneness manifest and interact during childhood—a period when such traits begin to emerge and may be particularly responsive to environmental factors. Importantly, while ADHD is generally regarded as a more stable neurodevelopmental trait, boredom proneness may be more modifiable, particularly through environmental support and regulatory strategies10,11. This distinction highlights the potential value of understanding how boredom functions in relation to ADHD tendencies during early development. To lay the groundwork for future intervention strategies, the present study explores how parental variables are associated with children’s ADHD tendencies and boredom proneness during early elementary school years, a developmental window that has received relatively little empirical attention.

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by symptoms of inattention, disorganization, and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity12 leading to impairment in various contexts. Epidemiological studies indicate that ADHD is more prevalent in boys than in girls9and frequently persists into adulthood. Individuals with pronounced ADHD symptoms often experience greater difficulties in executive functioning13, which may contribute to the development of other mental health disorders and adverse life outcomes, including poor academic performance, challenges in employment and interpersonal relationships, and behavioral problems9. The global prevalence of ADHD in children, as reported in 2018, is estimated to be approximately 3–5%9, while the prevalence among Japanese children is presumed to range from 3 to 7%, although definitive epidemiological data remain insufficient14. Additionally, some researchers have suggested that a significant proportion of individuals with ADHD in Japan remain undiagnosed until adulthood, resulting in a lack of appropriate treatment15. Early identification of ADHD is essential, as it presents an opportunity to mitigate secondary adverse consequences, such as depression and maladaptive behavior. To provide effective psychobehavioral support to children with ADHD in the early stages of identification, it is necessary to explore factors associated with ADHD tendencies that may guide interventions.

Although heritability is known to account for a substantial proportion of ADHD risk—with multiple susceptibility genes exerting stronger influences than environmental factors16 — accumulating evidence indicates that environmental contexts, such as parenting style, also play a role in shaping both the manifestation and the broader etiology of symptoms17. Rather than reflecting a categorical distinction, ADHD is increasingly understood to arise from probabilistic contributions of genetic predispositions and environmental influences in dynamic interaction. In this study, we conceptualize parenting styles using a widely accepted two-dimensional framework that distinguishes between responsiveness (e.g., warmth, emotional support, and sensitivity to the child’s needs) and control (e.g., behavioral regulation, supervision, and discipline), as outlined in foundational theoretical models18,19.

Boredom is recognized as a core characteristic of ADHD20,21. Studies on both humans and animals have demonstrated that excessive boredom can lead to harmful behaviors driven by the need for stimulation22,23. In human studies, a strong association has been observed between high boredom proneness and various maladaptive behaviors, including pathological gambling, internet addiction, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, depression, and substance abuse24,25,26. The negative impact of boredom on cognitive performance has also been widely discussed3,27. However, little is known about the underlying neural mechanisms or cognitive processes that contribute to the experience of boredom. In children, some studies suggest that higher levels of boredom are associated with poorer academic performance7, but research on the nature of daily boredom in childhood remains limited. The way children cope with boredom may influence their ability to develop interests and, ultimately, shape their future adaptability6,28. However, due to the scarcity of research on childhood boredom, the relative contributions of genetic and environmental factors, particularly in relation to ADHD tendencies, remain unclear.

It is important to distinguish boredom from clinical disorders. Boredom is a universal affective experience that most individuals encounter in daily life, though they differ in their trait-level proneness to it. While high levels of boredom proneness have been linked to a range of maladaptive outcomes, ADHD—though often conceptualized as a clinical disorder—comprises characteristics that also exist on a spectrum throughout the general population. Diagnoses are made when these traits reach clinically significant levels of impairment and persistence. Both ADHD and boredom proneness can thus be understood dimensionally, and in this study, we operationalize them as continuous, trait-like tendencies.

Given the limited empirical research on how these two traits emerge and interact during childhood, the present study examines their associations in early school-aged children. Specifically, we investigate how parental characteristics—including those more likely shaped by genetic influences (e.g., parental ADHD and boredom proneness) and those more likely reflective of environmental influences (e.g., parenting style)—are related to children’s ADHD and boredom tendencies. This approach enables an exploratory assessment of the relative contributions of inherited and contextual factors within a community sample. Given the significant deficiencies in research on the ADHD–boredom relationship, particularly in Japan, an additional objective of this study was to examine this relationship in parents themselves. Furthermore, in Japan, the majority of parental surveys have historically focused on mothers, with fathers rarely included in such studies29,30. By incorporating data from both fathers and mothers, this study seeks to provide new insights into potential differences in how parental ADHD and boredom tendencies, as well as parenting attitudes, are associated with children’s ADHD and boredom levels. Additionally, parents were asked to report their income and education levels, in addition to their child’s approximate academic achievement for reference.

Since this is among the first studies to address this specific constellation of variables, and given the absence of directly comparable prior work, we formulated preliminary hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that ADHD and boredom tendencies represent correlated trait-level dispositions, with ADHD tendencies being a stronger predictor of boredom proneness than the reverse. Second, we expected that children’s ADHD and boredom tendencies would be significantly associated with corresponding parental traits, although the relative contributions of maternal and paternal influences remain uncertain. Third, we hypothesized that children’s academic achievement may be negatively associated with both ADHD and boredom tendencies. Finally, we anticipated that parenting style—particularly levels of responsiveness and control—might be associated with children’s ADHD and boredom traits, but the magnitude and direction of these effects were considered exploratory.

Methodology

Participants and data collection process

An email containing an overview of the study, details of the honorarium, and an invitation to participate was distributed via a commercial survey company to registered parents of children in first through third grade. We targeted parents of children in grades 1 through 3 because the study aimed to examine associations between children’s ADHD tendencies, boredom proneness, and parent-related variables during early childhood— a developmental period that, despite its importance for later mental health and cognitive functioning, has been relatively understudied. Additionally, the ADHD-RS-IV used to assess children’s ADHD symptoms is validated for children aged 5 years and older. Furthermore, because preschool-aged children generally exhibit high levels of distractibility and restlessness, it is difficult to reliably assess individual differences in boredom proneness during that stage of development.

The invitation encouraged participation from both parents, when possible. Questionnaire packets and informed consent forms were sent via postal mail to 400 families (400 fathers and 400 mothers) in which both parents agreed to participate. A total of 355 fathers and 367 mothers returned completed questionnaires and signed consent forms by the designated deadline, yielding participation rates of 89% and 92%, respectively.

Because the study aimed to examine the relationship between paternal and maternal variables in relation to the same child, we included only data from parent pairs who completed items related to their own ADHD and boredom tendencies, as well as key child-related variables. Responses to private background items such as income and education level were not required for inclusion. As a result, the final analytic sample consisted of 301 father–mother pairs (602 individuals). Missing data were handled using listwise deletion. The proportion of excluded cases due to missing data was 0.592% for fathers and 0.599% for mothers, with no significant difference by parent gender. We also examined whether missingness was associated with socioeconomic status (SES); no significant SES differences were found between included and excluded households. Among the included group, the proportions of high and regular SES were 83.2% and 16.8%, respectively, compared to 83.1% and 16.9% in the excluded group.

Participants were predominantly middle-class fathers and mothers in their 30 s to 50s. In Japan, approximately 90% of individuals identify as middle class (Wang, 2020). Thus, although recruiting through a commercial survey company aligns with national demographic trends, the sample may not fully represent all Japanese families with young school-aged children, particularly those in single-parent households or outside the middle-class demographic. This limitation is addressed further in the Discussion section.

The mean ages of fathers, mothers, and children were 42.86 ± 5.43, 40.86 ± 4.69, and 8.28 ± 0.93 years, respectively. The gender distribution of children was nearly balanced (male: female = 149:152). Due to some participants opting not to disclose private information, the supplemental analysis included data from 597 participants for education level and 596 participants for income.

Approximately 62.24% of the families reported an annual income exceeding 6 million JPY, while 17.35% had an annual income exceeding 10 million JPY. Furthermore, 99.33% of the parents had attained at least a high school education, and 68.39% had earned a bachelor’s degree or higher. All participants were native Japanese speakers.

Survey content

The survey included the following questionnaires and scales:

-

Japanese version of the Boredom Proneness Scale (BPS): 28 items rated on a seven-point scale (1 = “not at all applicable”, 7 = “very applicable”)31,32,33.

-

Japanese version of the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale-V1.1: 18 items rated on a five-point scale (0 = “never”, 4 = “very often”)34.

-

Japanese Parenting Style Scale: 16 items rated on a four-point scale (1 = “not at all applicable”, 4 = “exactly applicable”)35,36.

-

Japanese version of the ADHD Rating Scale-IV for young children (aged ≥ 5 years): 18 items rated on a four-point scale (0 = “never” or “rarely seen”, 3 = “very often seen”)37.

-

One item assessing the child’s daily boredom level, rated on a seven-point scale (1 = “hardly bored”, 7 = “very often bored”).

-

One item assessing the child’s academic performance, rated on a four-point scale (1 = “generally poor”, 4 = “good”).

Structure and sample items of the psychological scales

Both the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale-V1.1 (ASRS-V1.1) and the ADHD Rating Scale-IV for young children (ADHD-RS-IV), originally developed in English, comprise two subscales: inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. However, these subscales are known to be highly correlated, and in both clinical and research settings, total scores are commonly used. Consistent with the present study’s aim of capturing overall ADHD tendencies, we utilized total scores for both scales in our analyses. The Boredom Proneness Scale (BPS), also originally developed in English, has been subjected to factor analyses in prior research, but the identified factor structures have varied considerably across studies. Given this inconsistency and the widespread use of the total score in the literature, we adopted the total score approach in this study as well. In contrast, the Japanese Parenting Style Scale (JPS), developed specifically in Japanese, consists of two clearly defined subscales: responsiveness and control. In line with standard practice in prior research, we analyzed these subscale scores separately. To illustrate the content of the psychological scales used, sample items from some of the measures are provided. For example, the ASRS includes the item “How often do you fidget or squirm with your hands or feet when you have to sit down for a long time?”, and the BPS includes “Many things I have to do are repetitive and monotonous” (True item). The Japanese version of the ADHD Rating Scale-IV, which is used for parent or teacher ratings of children, is subject to copyright restrictions that prevent public disclosure of item content. However, its content closely parallels that of the ASRS.

Further demographic details, along with information on data previously published elsewhere33,38, are available in Supplementary Material 1.

Reliability of the scales used in the analyses

We assessed the reliability of the scales used in this study, including the BPS, the adult ADHD assessment scale (ASRS-V1.1), the Parenting Style Scale (JPS), and the ADHD assessment scale for young children aged ≥ 5 years (ADHD-RS-IV). The alphas for the scales and subscales are summarized in Table 1. Cronbach’s α was not calculated for the single-item boredom measure, as internal consistency cannot be assessed for single-item scales.

For the BPS, the ASRS-V1.1, and the ADHD-RS-IV, total scores were used in the analyses. As the JPS consists of two distinct subscales—responsiveness and control—we verified that this structure was maintained in our dataset. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for these three scales and the subscales confirmed an acceptable level of internal consistency. Therefore, these values were used as variables in the analyses.

Ethical considerations

Participants were fully informed about the study’s objectives, participation procedures, incentives, data anonymity, and the planned publication of results during the distribution of the survey. Only couples who provided mutual consent were allowed to participate.

Households that agreed to participate received two sets of questionnaires (one for each parent) along with a survey request document. This document reiterated the same information provided during the web-based recruitment. Participants were instructed to complete and return the survey only if both parents consented to participation.

The study was conducted following approval from the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee of Ochanomizu University (approval date: 9 December 2021; approval number: 2021 − 152). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including both Japanese and international ethical standards for research involving human participants.

Statistical analyses

To examine factors influencing ADHD and boredom tendencies in children, we constructed a regression model using parental factors as independent variables, as well as children’s factors. Prior to regression analysis, all variables were standardized. Each set of parental data was linked to their corresponding child, maintaining within-family correspondence across all cases. While path or mediation analysis can offer insights into indirect relationships among variables, we did not adopt such approaches in the current study. Given the exploratory nature of this research and the absence of a well-established theoretical framework to justify directional paths among child, parent, and environmental factors, we opted instead for a data-driven regression approach to identify the most robust predictors.

For model optimization, we applied a backward stepwise selection approach, minimizing the Akaike information criterion using the “step” function in R. To ensure the absence of multicollinearity, we calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF) for all predictor variables, defined as 1/tolerance (where tolerance is 1 minus the R2of a variable regressed against all other predictors). All models yielded VIF values < 2.00, confirming that multicollinearity was not a concern.

All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.3.2). The data used in the present analyses are available in Supplementary Material 2.

Utilization of large language models

In the original manuscript, the language was reviewed by two professional editors who are native English speakers. For the revised manuscript, all English paraphrasing and grammar refinement were conducted using ChatGPT (a large language model developed by OpenAI) to ensure linguistic clarity and consistency throughout the text.

Results

Regarding descriptive statistics, the father’s variable was based on responses provided by the father, the mother’s variable was based on responses provided by the mother, and for the child’s variable, the average of the values reported by both parents was used. For subsequent analyses, including correlation and regression analyses, standardized values were employed for all variables.

Central influence of ADHD tendencies on parental and child factors

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of parental ADHD tendencies, boredom proneness, parenting styles, and children’s ADHD tendencies, boredom levels, and academic performance, collected through the questionnaire. The correlation matrix of these factors is presented in Table 3; Fig. 1.

Overview of parents’ and children’s factors. Correlation network illustrating the relationships between parents’ and children’s factors. Correlations with a coefficient ≥ 0.2 are connected by lines of equal length. The line’s thickness corresponds to the correlation strength (with thicker lines indicating a coefficient around or above 0.3). Blue lines represent positive correlations, while red lines indicate negative correlations. Refer to the Note in Table 3 for details on abbreviations.

Both parental and child ADHD tendencies emerged as central variables influencing other factors within the overall framework. A positive correlation was observed between ADHD tendencies and boredom levels, whereby parents with ADHD tendencies exhibited higher boredom proneness, mirroring the pattern observed in children. Additionally, parental ADHD and boredom proneness were reflected in their parenting styles, potentially diminishing the positivity of parenting as these tendencies intensified. Furthermore, in relation to elementary school academic performance, ADHD tendencies demonstrated a stronger correlation than boredom levels. These findings demonstrated the significant impact of ADHD tendencies on both parental and child-related factors.

Multiple regression analysis of child ADHD tendency

Given the central role of ADHD tendencies, we conducted a multiple linear regression analysis using the stepwise method to identify the factors most closely associated with children’s ADHD tendencies. Informed by previous research emphasizing the substantial role of innate-like or biologically influenced factors in ADHD39,40,41, along with the results of the present correlational analyses (Table 3; Fig. 1), the regression models were developed to incorporate the contributions of parental ADHD and boredom proneness.

Initially, separate multiple regression models were constructed to assess the contributions of fathers and mothers to their children. Each model included all main effects and their interaction terms to comprehensively evaluate potential explanatory relationships. In the maternal model, only the mother’s ADHD tendency emerged as a significant explanatory variable (β = 0.36, p < 0.001). In contrast, in the paternal model, both the father’s ADHD tendency (β = 0.23, p < 0.001) and boredom proneness (β = 0.12, p < 0.05) significantly predicted child ADHD tendencies (Table 4). In both models, being female was also identified as a significant explanatory variable. When comparing the explanatory power of the two models, the maternal model exhibited a higher coefficient of determination (Table 4; Fig. 2). Subsequently, a combined model was constructed by integrating the significant explanatory variables from both parental models (Table 4). This combined model (referred to hereafter as the parental model), which included the interaction between maternal and paternal ADHD tendencies (β = 0.13, p < 0.05), outperformed both separate models in overall explanatory power.

Performance of regression models for child ADHD. (A) Scatter plot showing the relationship between actual children’s ADHD tendencies and the values predicted by maternal ADHD tendencies. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval, (all variables were standardized before regression analysis; n = 301, p = 9.1 × 10-16 )., (B) Scatter plot of actual children’s ADHD tendencies against the values predicted by paternal ADHD and BPS. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval, (all variables were standardized before regression analysis; n = 301, p = 7.2 × 10-12 )., (C) Scatter plot of actual children’s ADHD tendencies versus predictions made by combining maternal ADHD and paternal ADHD with BPS. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval, (all variables were standardized before regression analysis; n = 301, p = 2.2 × 10-16 )., (D) Scatter plot of the actual ADHD values of children with the top 20 ADHD tendencies, (highlighted in gray in Fig. 2C) versus predictions made based on maternal responsiveness. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval, (all variables were standardized before regression analysis; n = 20, p = 9.1 × 10-5 ).

To more accurately assess the fit of the three models while accounting for potential overfitting, we evaluated model performance using cross-validated R² in addition to Multiple R² and Adjusted R². As with the other indices, the parental model yielded higher cross-validated R² values compared to the maternal and paternal models. Notably, the cross-validated R² values were slightly higher than the corresponding Multiple and Adjusted R² values, suggesting that the models were not overfitted and that their predictive performance remained stable across folds. Taken together, these results indicate that the parental model provides the most robust and generalizable account of the data.

However, similar to the individual parental models, the combined model demonstrated reduced predictive accuracy for children with high ADHD tendencies (represented in gray in Fig. 2C). Given this limitation, we conducted a segmented regression analysis to further investigate cases with particularly poor model fit. This analysis, applied to the residuals of the original model predicting ADHD symptoms, identified an inflection point at a standardized ADHD score of 1.701, corresponding to a raw ADHD-RS score of 26. Participants exceeding this threshold were classified as the “high-ADHD” subgroup (n = 20). To avoid overfitting in this small subgroup, we deliberately refrained from using stepwise regression. Even a two-variable regression model typically requires at least 40 observations to ensure stable predictive performance42. Instead, we conservatively selected a single predictor—maternal responsiveness—based on its strong and statistically significant correlation with children’s ADHD symptoms (see Supplementary Material 3).

Regression analysis revealed that maternal responsiveness alone accounted for 58% of the variance in ADHD tendencies among children in the high-ADHD subgroup (represented in gray in Fig. 2C; see also Fig. 2D; Table 5). This significant association suggests that heightened maternal attentiveness may exacerbate ADHD-like behaviors in children who are already predisposed to such tendencies.

Multiple regression analysis of child boredom level

In the correlation analysis, children’s academic performance was more strongly associated with ADHD tendencies than with boredom levels. However, this may reflect the limited variability in academic performance typically observed during the elementary school years. To better assess the potential long-term contributions of ADHD and boredom, we conducted follow-up analyses using adult data, examining associations between self-reported final educational attainment, income, boredom proneness, and ADHD tendencies.

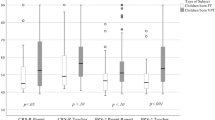

Among adults stratified by educational attainment (bachelor’s degree or higher vs. lower) and household income (above or below 10 million JPY—an approximate benchmark of financial affluence in Japan), t-test results revealed no significant differences in ADHD tendencies. In contrast, adults with higher educational attainment and income levels showed significantly lower boredom proneness (Fig. 3A and 3B). These results suggest that boredom proneness—likely a relatively stable trait from childhood to adulthood—may precede and contribute to later educational and economic outcomes.

Lifelong impact of boredom proneness and performance of regression models for child boredom. A) Comparison of parents’ ADHD and boredom proneness according to educational background (n = 239 and 358 for groups with “below bachelor’s degree” and “bachelor’s degree or above,” respectively. A significant difference between the two groups was observed for boredom proneness but not for ADHD: ADHD, t(595) = −1.058, p = 0.291; Boredom, t(595) = 4.285, p = 0.000. ***p < 0.001). B) Parents’ ADHD and boredom proneness by household income (n = 496 for an annual income of 1–10 million JPY, and n = 100 for an annual income > 10 million JPY. A significant difference between the two groups was observed for boredom proneness but not for ADHD: ADHD, t(594) = 0.326, p = 0.745; Boredom, t(594) = 4.468, p = 0.000. ***p < 0.001). (C) Scatter plot of actual children’s boredom levels against predictions made using innate factors of their ADHD and maternal BPS. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval (all variables were standardized before regression analysis; n = 301, p = 7.2 × 10−11). (D) Scatter plot of actual children’s boredom levels versus predictions based on innate factors and parenting styles. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval (all variables were standardized before regression analysis; n = 301, p = 5.2 × 10−11).

Building on these findings, we conducted multiple regression analyses using a stepwise AIC method to identify predictors of children’s boredom levels. All models included main effects and interaction terms to comprehensively evaluate potential explanatory relationships. We first constructed an innate-only model based on the child’s characteristics and parental traits. In this model, the child’s ADHD tendency emerged as a strong predictor (β = 0.31, p < 0.001), and maternal boredom proneness also contributed significantly (β = 0.19, p < 0.001).The influence of paternal boredom proneness was accounted for indirectly via the child’s ADHD tendency and was not retained in the optimized model (Table 6; Fig. 1).To assess the risk of overfitting in this and subsequent models, we calculated cross-validated R² in addition to Multiple and Adjusted R². The cross-validated R² values were comparable to or slightly higher than the other R² metrics, indicating stable predictive performance across folds and minimizing concerns of overfitting.

Next, recognizing that boredom may be more malleable to environmental influences than ADHD tendencies21,43, we extended the model to include parenting variables. In this combined (innate + parenting) model, maternal control emerged as a significant negative predictor (β = − 0.14, p < 0.05), suggesting that more structured maternal discipline may reduce boredom in children. Additionally, a significant interaction was found between children’s ADHD tendencies and paternal responsiveness (β = 0.11, p < 0.05). No other interaction terms included in the stepwise procedure were retained. These findings indicate that high ADHD tendencies in children may be particularly associated with elevated boredom when coupled with high paternal responsiveness (Table 6). As with the previous model, we evaluated model fit using cross-validated R², which again supported the robustness and generalizability of the model by showing no indication of overfitting.

Furthermore, building on our finding that boredom proneness—but not ADHD tendencies—was associated with socioeconomic status (SES) in adulthood, we considered whether parental SES might also relate to children’s boredom levels. To evaluate this possibility, we incorporated SES indicators (father’s education, mother’s education, and household income) into the stepwise AIC regression. However, none of these variables were retained in the final models, as they did not reach statistical significance during the selection process.

Recognizing the theoretical importance of SES and the possibility of more complex, indirect effects, we additionally constructed a structural equation model (SEM) that included children’s ADHD tendencies, parental characteristics, SES variables, and their interactions. This model allowed us to examine both direct and indirect pathways—for example, from household income to child boredom via parental traits. However, the overall model fit did not meet conventional thresholds: CFI = 0.888, TLI = 0.794, RMSEA = 0.069, and SRMR = 0.052. In particular, the CFI and TLI values fell below the typical cutoff (≥ 0.90) for acceptable model fit. Moreover, the SEM’s significant direct effects were limited to children’s ADHD tendencies and maternal boredom proneness—both of which had already emerged as significant predictors in the stepwise AIC model. Although an indirect path from household income to child boredom proneness via maternal boredom proneness was statistically significant, its standardized coefficient was less than 0.04, indicating a negligible effect size (Table 7).

By contrast, the stepwise AIC model (innate + parenting) provided a more parsimonious structure, consisting of five main effects and one interaction. Although the model’s explanatory power was modest (Adjusted R² = 0.166), it offered greater statistical efficiency and clearer interpretability than the SEM. Taken together, these results suggest that while SEM can elucidate potential indirect pathways and theoretical structures, the stepwise regression model remains more robust and practically informative given the present data constraints.

Discussion

This study investigated factors associated with the development of children’s ADHD tendencies and boredom levels by analyzing paternal and maternal influences. Consistent with existing literature, ADHD tendencies and boredom proneness were closely related within each parent. As anticipated, parental ADHD tendencies directly contributed to their child’s ADHD tendencies, which in turn were strongly associated with the child’s boredom level. However, the contributions of fathers’ and mothers’ ADHD and boredom tendencies to their children were not identical. Additionally, the impact of parenting styles varied depending on the child’s level of ADHD tendencies, with significant associations observed only in children with high ADHD tendencies. Although a partial influence of parenting styles was anticipated, the conditional effect based on ADHD severity was an unexpected finding.

This study also revealed relationships of child and parental boredom and ADHD tendencies with other factors. Contrary to expectations, children’s academic performance was more strongly correlated with ADHD tendencies than with boredom levels. The implications of each result are discussed in detail below. First, the relationship between parental and child ADHD tendencies is examined in the context of existing literature, followed by a discussion of the novel findings unique to this study.

Stepwise regression analysis of children’s ADHD tendencies revealed that both parents’ ADHD tendencies significantly contributed to their child’s ADHD tendencies, consistent with previous research findings39,40,41. A multiplicative interaction was observed when both parents exhibited high ADHD tendencies. In addition, a correlation was found between both parents’ ADHD tendencies, suggesting that individuals with similarly high ADHD traits may be more likely to form partnerships, which could in turn be associated with a greater likelihood of elevated ADHD tendencies in their offspring. This observation contrasted with previous studies44,45, which have reported inconsistent associations between parental and child ADHD symptoms or subtypes. Some studies have indicated weak correlations for specific symptoms or subtypes, but few consistent significant associations have been found overall.

Being female emerged as a significant explanatory variable, suggesting a lower likelihood of ADHD in girls, consistent with previous studies showing that ADHD symptoms are more common in boys46,47.

To better distinguish between genetic and nurturing influences of parents and other congenital and environmental factors (e.g., cultural influences) on children’s ADHD tendencies, future research should examine a broader range of general parent–child data, including individual ADHD tendency assessments. Comprehensive data collection across diverse populations is necessary to clarify the complex interplay between genetic predisposition, parenting styles, and environmental factors in the context of the development of ADHD tendencies in children.

Although all data were based on parental reports, the present study provided novel insights by analyzing parent–child ADHD tendencies alongside data on parent–child boredom levels, parenting styles, and socioeconomic factors, such as income and academic level.

Firstly, the analysis revealed that only fathers’ boredom proneness significantly impacted their child’s ADHD tendencies; mothers’ boredom proneness did not. This finding may be attributed to the possibility that highly boredom-prone fathers are more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking and alcohol consumption, which could contribute to the child’s development even before birth1,48. Additionally, this could be related to genetic differences between parents. A Canadian study on ADHD and depression suggested that parental hereditary influences on children might differ due to genomic imprinting, the involvement of sex chromosomes, or sex-specific physiological or hormonal factors49. Since previous studies in Japan predominantly focused on maternal influences, partly due to challenges in collecting data specifically from fathers, this finding regarding the impact of Japanese fathers’ boredom proneness on their children’s ADHD tendencies offered a novel perspective. Future research should further explore the influence of paternal factors on child development in Japan.

Secondly, the study identified a nuanced relationship between parenting style and children with high ADHD tendencies. To avoid confusion regarding causality, parenting styles were not initially included as independent variables in the regression analysis, given the lack of definitive evidence linking postnatal environments to ADHD development. However, the data indicated that parental ADHD and boredom proneness— presumed to be more genetically influenced—could only account for children’s ADHD tendencies up to a certain level. In the subgroup of children with the highest ADHD tendencies, the predicted values based on these parental traits were generally above average but did not fully align with the observed scores. Interestingly, in these cases, children’s ADHD tendencies were better explained by the mother’s responsiveness.

While this finding may suggest that excessive maternal responsiveness exacerbates ADHD-related behaviors in children, we acknowledge that the observed association may also reflect reverse or bidirectional influences. Specifically, elevated levels of child ADHD tendencies may elicit increased parental responsiveness, which could appear “excessive” but may actually represent parental accommodation or efforts to manage challenging behaviors. That is, higher responsiveness may not necessarily be maladaptive in nature, but rather a reactive and supportive strategy. Prior literature has similarly emphasized the potential for complex, bidirectional dynamics in parent–child interactions involving ADHD symptoms.

For example, one study reported that maternal warmth mitigated ADHD symptoms, particularly in low-birth-weight infants50. Conversely, another study found that children with higher ADHD tendencies tended to elicit lower warmth from their mothers51, suggesting that maternal warmth may be a response to, rather than a cause of, child symptomatology. In our study, maternal responsiveness—as captured by the reactivity index—may similarly reflect both warmth and accommodation in response to children’s behavioral challenges, rather than exerting a unidirectional influence on ADHD development.

Additionally, a UK-based study found that high parental separation anxiety was associated with improved cognitive performance across multiple domains in children with pronounced attention deficits52, further complicating assumptions about the adaptive or maladaptive nature of parental overinvolvement. Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of considering reciprocal parent–child dynamics when interpreting parenting style effects. Future research employing longitudinal or bidirectional modeling approaches (e.g., cross-lagged panel analysis) is warranted to more clearly determine the directionality of effects between parental responsiveness and children’s ADHD tendencies.

Further insights were obtained by exploring the relationship between individual boredom levels, ADHD tendencies, and various life-related indicators. In children, a stronger correlation was observed between academic performance and ADHD tendencies than between academic performance and boredom proneness. Conversely, in parents, lower boredom proneness was more likely to be associated with significantly higher education and income levels than ADHD tendencies. This aligned with previous studies on undergraduate students, which consistently highlighted a significant relationship between boredom proneness and academic performance7,53,54. These findings suggested that boredom proneness, given its broad impact on life development, warrants greater attention and further research.

Furthermore, regression analysis revealed factors significantly associated with children’s boredom levels. Consistent with previous studies, a strong link was observed between ADHD and boredom20,21. However, in regression models incorporating postnatal parenting factors, maternal control demonstrated an effective inhibitory effect on a child’s boredom. This finding was in agreement with studies indicating that individuals in environments with numerous choices are more susceptible to boredom than those in more restricted environments55. It is plausible that timely and proactive behavioral guidance of primary school-aged children by mothers, particularly in navigating complex environments, can effectively reduce their tendency towards boredom.

Additionally, the analysis revealed that fathers’ responsiveness interacted with children’s ADHD tendencies, significantly contributing to children’s boredom levels. This pattern mirrors the pattern observed in the ADHD model, where excessive maternal responsiveness was associated with heightened ADHD tendencies in children. These findings suggested that, for children at elevated genetic risk for ADHD, parental over-responsiveness may contribute to ADHD-related behaviors and may also be associated with increased boredom proneness. This underscores the importance of balanced parental involvement to avoid reinforcing such tendencies.

Despite the comprehensive approach taken in data collection and analysis, this study had several limitations. First, in assessing children’s boredom levels, the absence of a specialized boredom proneness scale for children necessitated reliance on a simplified, single-item measure. Although no evidence of ceiling or floor effects was observed in the responses, single-item indicators are generally more susceptible to measurement error and lack the psychometric rigor of multi-item scales. The use of a limited seven-point rating scale—compared to the more detailed ADHD assessment—may have also contributed to the relatively lower explanatory power of the boredom regression model. Future research should develop and employ validated, developmentally appropriate multi-item measures to more accurately assess boredom proneness in children.

Another limitation was the inability to establish causal relationships. Although the analyses were grounded in existing literature and deductive reasoning, the use of linear regression models does not provide conclusive evidence of causality. Future studies should consider leveraging larger datasets or employing longitudinal designs and intervention experiments to better elucidate causal pathways.

Another limitation concerns the generalizability of the findings, given that the majority of participants were middle-class. While this reflects national demographic trends in Japan, the current sample did not include single-parent families or those from lower or higher socioeconomic backgrounds. Future research should aim to include a broader range of family structures and socioeconomic statuses to enhance the generalizability of the results.

A further limitation is that all child-related data were reported by parents, raising the possibility of informant bias. Although different scales were used for parents and children, and child scores were averaged across both parents to reduce single-rater effects, the use of a shared informant may still have inflated some associations. In addition, the absence of child-reported data represents a further limitation. While children’s perspectives—particularly regarding parenting—can offer valuable insights, the ADHD and boredom scales used in this study are currently validated only for parent or teacher report in Japan. Moreover, given the relatively young age range of the children, self-reports on constructs such as boredom proneness or academic performance may lack sufficient reliability and validity. Future research should incorporate teacher reports, observational measures, or task-based assessments to triangulate findings and enhance the validity of results.

Nevertheless, this study was the first to examine the associations between children’s and parents’ boredom and ADHD tendencies, as well as their relationships with parenting styles and other relevant factors. By including data from fathers alongside mothers, the findings suggested that paternal and maternal influences may differentially impact children’s boredom and ADHD tendencies. This highlighted the importance of considering both parental roles in future investigations.

Further research is needed to explore the complex interactions between children’s boredom and ADHD tendencies, parental influences, and other environmental factors. This could enhance our understanding of the underlying mechanisms and contribute to the development of effective strategies to support children’s well-being throughout their lives.

Data availability

Datasets analyzed during the current study are available in Supplementary Material 2.

References

Taylor, E., Chardwick, O., Heptinstall, E. & Danckaerts, M. Hyperactivity and conduct problems as risk factors for adolescent development. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 35, 1213–1226 (1996).

Roshani, F., Piri, R., Malek, A., Michel, T. M. & Vafaee, M. S. Comparison of cognitive flexibility, appropriate risk-taking and reaction time in individuals with and without adult ADHD. Psychiatry Res. 284, 112494 (2020).

Haager, J. S., Kuhbandner, C. & Pekrun, R. To be bored or not to be bored—How task-related boredom influences creative performance. J. Creative Behav. 52, 297–304 (2018).

Mueller, A., Hong, D. S., Shepard, S. & Moore, T. Linking ADHD to the neural circuitry of attention. Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul Ed. 21, 474–488 (2017).

Eastwood, J. D., Frischen, A., Fenske, M. J. & Smilek, D. The unengaged mind: defining boredom in terms of attention. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 7, 482–495 (2012).

Danckert, J. & Eastwood, J. D. Out of my Skull: the Psychology of Boredom (Harvard University Press, 2020).

Tze, V. M. C., Daniels, L. M. & Klassen, R. M. Evaluating the relationship between boredom and academic outcomes: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychol. Rev. 28, 119–144 (2016).

Shaw, M. et al. A systematic review and analysis of long-term outcomes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of treatment and non-treatment. BMC Med. 10, 99 (2012).

Sayal, K., Prasad, V., Daley, D., Ford, T. & Coghill, D. ADHD in children and young people: prevalence, care pathways, and service provision. Lancet Psychiatry. 5, 175–186 (2018).

Ng, H. C., Wong, W. L. & Chan, C. S. The effectiveness of an online attention training program in improving attention and reducing boredom. Motivation Emot. 48, 758–775 (2024).

Gorelik, D. & Eastwood, J. D. Trait boredom as a lack of agency: A theoretical model and a new assessment tool. Assessment 31, 321–334 (2024).

American Psychiatric Association, D. & American Psychiatric Association. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association Washington, DC, 2013).

Otterman, D. L. et al. Executive functioning and neurodevelopmental disorders in early childhood: a prospective population-based study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Mental Health. 13, 38 (2019).

ADHD Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines Research Group, Saito, L. & Iida, J. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)-V. 43, 525p (Jihou, Tokyo, 2022). [Written in Japanese]

Naya, N. et al. The burden of undiagnosed adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in japan: a cross-sectional study. Curēus (Palo Alto CA). 13, e19615 (2021).

Faraone, S. V. et al. The world federation of ADHD international consensus statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neurosci. Biobehavioral Reviews. 128, 789–818 (2021).

Yoshimasu, K. Epidemiology and pathological condition of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder: from perspective of relationship between genetic and environmental factors. J. Japan Health Med. Association. 29, 130–141 (2020). [Written in Japanese].

Baumrind, D. Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychol. Monogr. 75, 43–88 (1967).

Maccoby, E. E. & Martin, J. A. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-Child interaction. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, Personality, and Social Development (eds Mussen, P. H. & Hetherington, E. M.) 1–101 (Wiley, 1983).

Chou, W., Chang, Y. & Yen, C. Boredom proneness and its correlation with internet addiction and internet activities in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 34, 467–474 (2018).

Golubchik, P., Manor, I., Shoval, G. & Weizman, A. Levels of proneness to boredom in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on and off methylphenidate treatment. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 30, 173–176 (2020).

Yawata, Y. et al. Mesolimbic dopamine release precedes actively sought aversive stimuli in mice. Nat. Commun. 14, 2433 (2023).

Havermans, R. C., Vancleef, L., Kalamatianos, A. & Nederkoorn, C. Eating and inflicting pain out of boredom. Appetite 85, 52–57 (2015).

Blaszczynski, A., Mcconaghy, N. & Frankova, A. Boredom proneness in pathological gambling. Psychol. Rep. 67, 35–42 (1990).

LePera, N. Relationships between boredom proneness, mindfulness, anxiety, depression, and substance use. New. School Psychol. Bull. 8, 15–25 (2011).

Sommers, J. & Vodanovich, S. J. Boredom proneness: its relationship to psychological- and physical-health symptoms. J. Clin. Psychol. 56, 149–155 (2000).

Chen, P. & Rau, P. P. Using EEG to investigate the influence of boredom on prospective memory in top-down and bottom-up processing mechanisms for intelligent interaction. Ergonomics 66, 690–703 (2023).

Uehara, I. & Ikegaya, Y. The meaning of boredom: properly managing childhood boredom could lead to more fulfilling lives. EMBO Rep. 25, 2515–2519. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44319-024-00155-0 (2024).

Arimoto, A. & Tadaka, E. Association of parental self- efficacy with loneliness, isolation and community commitment in mothers with infant children in japan: a cross- sectional study. BMJ Open. 13, e075059. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-075059 (2023).

Benesse Corporation, Benesse Educational Research and Development Institute. Monograph/Elementary School Students Now. Vol. 20 – 3: Parent-Child Relationships among Elementary School Students - Mothers’ Survey -. (2000).

Farmer, R. & Sundberg, N. D. Boredom proneness–the development and correlates of a new scale. J. Pers. Assess. 50, 4–17 (1986).

Vodanovich, S. J. & Watt, J. D. Self-report measures of boredom: an updated review of the literature. J. Psychol. 150, 196–228 (2016).

Uehara, I., Zhang, T. & Ikegaya, Y. Examination of the reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Boredom Proneness Scale: confirmation of the factor structure. J. Japan Acad. Hum. Care Sci. 17 (2), 8–18 (2024). [Written in Japanese].

Kessler, R. C. et al. The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): A short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol. Med. 35, 245–256 (2005).

Robinson, C. C., Mandleco, B., Olsen, S. F. & Hart, C. H. Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: development of a new measure. Psychol. Rep. 77, 819–830 (1995).

Nakamichi, K. & Nakazawa, J. Maternal/ paternal childrearing style and young children’s aggressive behavior. Bull. Fac. Educ. Chiba Univ. 51, 173–179 (2003). [Written in Japanese].

DuPaul, G. J. et al. [Sakamoto, R.et al. Translated to Japanese]. ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Checklists, Norms, and Clinical Interpretation Guilford Press. ; [Akashi-shoten, Translated 2008]) (1998).

Uehara, I. & Ikegaya, Y. Online orientation in early school grades: relationship with ADHD, boredom, concentration tendencies, and mothers’ parenting styles. Front. Psychol. 16, 1592563 (2025).

Lindblad, F., Weitoft, G. R. & Hjern, A. Maternal and paternal psychopathology increases risk of offspring ADHD equally. Epidemiol. Psychiatric Sci. 20, 367–372 (2011).

Biederman, J. et al. High-risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder among children of parents with childhood-onset of the disorder - A pilot-study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 152, 431–435 (1995).

Liljenwall, H., Lean, R. E., Smyser, T. A., Smyser, C. D. & Rogers, C. E. Parental ADHD and ASD symptoms and contributions of psychosocial risk to childhood ADHD and ASD symptoms in children born very preterm. J. Perinatol. 43, 458–464 (2023).

Schmidt, F. L. The relative efficiency of regression and simple unit predictor weights in applied differential psychology. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 31, 699–714. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447103100310 (1971).

Hsu, C. F., Chen, V. C., Ni, H. C., Chueh, N. & Eastwood, J. D. Boredom proneness and inattention in children with and without ADHD: the mediating role of delay aversion. Front. Psychiatry. 28;16, 1526089. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1526089 (2025).

Takeda, T. et al. Parental ADHD status and its association with proband ADHD subtype and severity. J. Pediatr. 157, 995–1000e1 (2010).

Faraone, S. V., Biederman, J. & Friedman, D. Validity of DSM-IV subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a family study perspective. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 39, 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200003000-00011 (2000).

Willcutt, E. G. The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analytic review. Neurotherapeutics 9, 490–499 (2012).

Ramtekkar, U. P., Reiersen, A. M., Todorov, A. A. & Todd, R. D. Sex and age differences in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and diagnoses: Implications for DSM-V and ICD-11. J Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 49, 217–228 (2010).

Han, J. et al. The effects of prenatal exposure to alcohol and environmental tobacco smoke on risk for ADHD: A large population-based study. Psychiatry Res. 225, 164–168 (2015).

Goos, L. M., Ezzatian, P. & Schachar, R. Parent-of-origin effects in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Res. 149, 1–9 (2007).

Tully, L. A., Arseneault, L., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E. & Morgan, J. Does maternal warmth moderate the effects of birth weight on twins’ attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms and low IQ? J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 72, 218–226 (2004).

Saito, A., Matsumoto, S. & Sugawara, M. Relationship between an attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) tendency and anxiety/depression: A longitudinal study of early adolescents. Japanese J. Educational Psychol. 68, 237–249 (2020). [Written in Japanese].

Anning, K. L., Langley, K., Hobson, C., De Sonneville, L. & Van Goozen, S. H. M. Inattention symptom severity and cognitive processes in children at risk of ADHD: the moderating role of separation anxiety. Child Neuropsychol. 30, 264–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2023.2190964 (2024).

Mugon, J., Boylan, J. & Danckert, J. Boredom proneness and self-control as unique risk factors in achievement settings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17, 9116 (2020).

Murakami, T., Tanaka, S. & Sasano, M. Association between susceptibility to ‘boredom’ and academic performance. J. Japanese Phys. Therapy Association. 36, 81 (2009). [Written in Japanese].

Struk, A. A., Scholer, A. A., Danckert, J. & Seli, P. Rich environments, dull experiences: how environment can exacerbate the effect of constraint on the experience of boredom. Cogn. Emot. 34, 1517–1523 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the participants for their involvement in this study. We also extend our gratitude to Yuka Sumaki for her assistance with data entry and dataset preparation.

Funding

This work received financial support from JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers JP18H05524 and JP23K17635) and from the Murata Science and Education Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.U. and Y.I. conceptualized and designed the study. I.U. prepared the study materials and was responsible for data collection and organization, which were reviewed and verified by T.Z. and Y.I. before data collection and after data arrangement. T.Z. preprocessed, classified, and analyzed the data, with validation by I.U. After drafting the majority of the manuscript, T.Z. collaborated with all authors in reviewing and finalizing the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T., Ikegaya, Y. & Uehara, I. Differential associations of parents’ ADHD tendencies, boredom proneness, and parenting styles with children’s ADHD tendencies and boredom proneness. Sci Rep 16, 575 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30163-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30163-6