Abstract

We develop the quantum approach to magnetometry utilizing phase estimation algorithms, demonstrating improvements in the estimation of magnetic flux in both precision and dynamical range. We propose the modifications to conventional algorithms including the signal modulation and proximity time measurements. We demonstrate that our approach extends the dynamical range and improves the precision of magnetic flux detection. We show that our approach enhances performance of superconducting qubits and enables higher information gain without compromising dynamical range, paving the way toward achieving the Heisenberg limit. Combining adaptive algorithms with device-specific calibration, our methods bridge the gap between theoretical advancements and practical quantum sensing applications, offering a powerful framework for metrology using superconducting qubits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum sensing and metrology represent powerful frameworks for achieving precise measurements of physical quantities by exploiting the inherent quantum properties of probe systems 1,2. These quantum sensors enable measuring a broad spectrum of phenomena, including gravitational forces, electromagnetic fields, and photon propagation, with unprecedented precision that surpasses the fundamental limits of classical techniques. Quantum sensors find applications in diverse fields, ranging from fundamental physics 3,4,5 to medical imaging 6,7, industrial diagnostics 8,9, and advanced technological applications 10, establishing their indispensable role across various domains.

Many leading platforms for quantum sensing including the nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers in diamond 11, cold-atom magnetometry 12, dc-superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs) 13,14 and superconducting qubits 15,16 attract significant attention. Superconducting qubits, in particular, offer exceptional opportunities for enhanced sensitivity in detecting weak magnetic fields and other environmental perturbations, primarily due to their ability to exploit quantum coherence and entanglement. Transmon qubits 15 are applied in magnetometry 16,17,18 due to their flux tunability and promising relaxation times. In this work, we explore fluxonium qubits 19,20,21 for quantum sensing, which offer longer coherence \(T_1\) and dephasing \(T_2\) times, higher inductance, and reduced susceptibility to charge noise.

Phase estimation algorithms (PEAs) are an integral part of quantum sensing protocols 22,23, serving as key tools for enhancing measurement precision. These algorithms 24,25,26,27, developed originally for quantum computing tasks such as Shor’s factorization algorithm 28,29 and Lloyd’s algorithm for solving linear systems 30, have become equally vital in quantum metrology 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. By enabling the precise estimation of unknown parameters that influence the quantum sensor’s energy spectrum, PEAs facilitate enhanced sensing. Optimizing the design of chip architecture incorporating superconducting qubits 17,21 and employing advanced PEAs promises to significantly improve the magnetic flux sensitivity, pushing up the limits of quantum-enhanced sensing.

Magnetometry with superconducting qubits

Quantum magnetometry using superconducting qubits leverages the sensitivity of the qubit’s transition frequency to external magnetic flux. A qubit device 44, often described as an artificial atom 16, carries the fundamental unit of quantum information, analogous to the classical bit. However, a qubit is a quantum two-level system that can exist not only in its two basic states, its ground state \(|0\rangle\) and excited state \(|1\rangle\), but, also in a superposition of these states. The possibility of such a superposition enables qubits45,46,47 to outperform their classical counterparts in certain computational tasks 48 and sensing applications 49. The qubit’s main transition frequency between the ground and excited states, \(\omega _{01}\), varies with the magnetic flux threading the superconducting loop interrupted by tunnel junctions 15,50, enabling precise magnetic field measurements, see Methods section for details. The key to improving the sensitivity of qubit-based magnetometers lies in optimizing the interaction between the qubit and the external flux. To quantify this interaction, the concept of a passport function was introduced 16, which characterizes the probability of the qubit to be in a particular state as a function of the phase accumulation time \(\tau\) and the external flux \(\Phi\). This probability function provides a reference for determining unknown flux values which are extracted by comparing the measured probabilities to the estimated predictions.

To measure the pattern of the passport function, the Ramsey sequence is employed to facilitate phase accumulation in the qubit. The sequence consists of two \({\pi }/{2}\) pulses, Hadamard gates, applied at the frequency \(\omega _{\text {dr}}\), which is the drive frequency of the control pulses, and which are separated by the phase accumulation time \(\tau\). Following the first pulse, the qubit state evolves around the z-axis on the Bloch sphere at a frequency \({\omega _{\text {e}}(\Phi )} = \omega _{01}(\Phi ) - \omega _{\text {dr}}\), accumulating phase over the time \(\tau\). The total acquired phase is then \(\phi = {\omega _{\text {e}} (\Phi )} \tau\). Here \(\omega _{01}(\Phi )\) is the transition frequency of the qubit at the working flux bias point \(\Phi\).

The qubit’s coherence is destroyed, as usual, by decoherence processes with the dephasing time \(T_2\); this dephasing time is used as a critical factor characterizing decoherence. The dephasing rate, \(T_2^{-1}\), is determined by energy relaxation time, \(T_1\), and pure dephasing characteristic \(\Gamma\); this implies that \(T_2^{-1}=(2T_1)^{-1} + \Gamma\). For modern superconducting qubits 21, it is the 1/f noise that often dominates the dephasing process 51,52,53,54,55,56,57, leading to a Gaussian decay in the qubit’s coherence as \(\exp [-(\Gamma _{1/f} \tau )^2]\). The relaxation rate remains relatively constant when the qubit operates away from its sweet spot, while the dephasing rate is more sensitive to external noise sources, resulting in faster decay of the coherence over time 20. Different measurement schemes have recently been implemented to study the relaxation mechanisms associated with quasiparticles 58 and two-level systems (TLS) 59.

The probability of finding the qubit in its ground state after completing the Ramsey sequence is given by

This probability depends on the external flux \(\Phi\) and the dephasing rate \(\Gamma _{1/f}\). After each measurement, the qubit is reinitialized to its initial state, and the experiment is repeated. If N repetitions yield \(N_0\) detections that the qubit is in its ground state, we can estimate this probability as \(P[\tau ,\,{\omega _{\text {e}}(\Phi )}] \approx {N_0}/{N}\). For small flux variations, the detuning rate can be approximated as \({\omega _{\text {e}}(\Phi )} = {\omega _{\text {e}}(0)} + ({d\omega _{01}(\Phi )}/{d\Phi })\Phi\).

Using this approximation, one obtains the following expression for the measured external flux

This expression shows the periodic nature of the measurement outcome, introducing an ambiguity in the determination of \(\Phi\) due to the cosine function’s periodicity. To resolve this ambiguity, PEAs such as the Kitaev 60 and quantum Fourier transform (QFT) 61,62,63 algorithms are employed. These algorithms refine the phase accumulation time \(\tau\) to narrow down the possible flux values, ultimately enabling an unambiguous flux determination.

The precision of magnetic flux measurements is characterized by the flux resolution precision \(\delta \Phi\) 16

where \(T_{\text {rep}}\) represents the duration of one measurement iteration, and \(t = N T_{\text {rep}}\) is the total measurement time for a given \(\tau\). This expression illustrates the complex interplay between phase accumulation time, decoherence, and the number of measurement repetitions in determining the flux resolution.

By optimizing the phase accumulation time \(\tau\), it is possible to achieve enhanced sensitivity. The optimal accumulation time \(\tau ^*\) balances the trade-off between the coherence time \(T_2\) and the measurement dynamics. Depending on the relationship between the reset time \(T_{\text {reset}}\) 64,65 (0.25 - 1 \(\mu s\)), gate time \(T_{\text {gate}}\) (\(\approx\) 6 ns) 66,67, and coherence 68 time \(T_2\), the optimal \(\tau ^*\) can range between \({T_2}/{\sqrt{2}}\) and \({T_2}/{2}\), ensuring the best measurement precision. If \(T_\textrm{reset} \gg \tau ^*\), then \(\tau ^* = {1}/({\Gamma _{1/f} \sqrt{2}}) = {T_2}/{\sqrt{2}}\), and if \(T_\textrm{reset} \ll \tau ^*\), then \(\tau ^* ={1}/({2\Gamma _{1/f}}) = {T_2}/{2}\).

To further enhance the magnetometer’s sensitivity, when using phase estimation algorithms like Kitaev and Fourier algorithms, we systematically vary the phase accumulation time in order to refine the flux estimate. For precision analysis, we use a parameter 16,69:

which is independent of the total measurement time. These algorithms utilize the properties of the probability function \(P[\tau , {\omega _{\text {e}}(\Phi )}]\) in order to achieve precise and unambiguous flux measurements, surpassing the classical shot-noise limit and approaching quantum-limited precision.

We apply these optimized measurement protocols to superconducting qubits, with a particular focus on fluxonium, a qubit architecture known for its long coherence times 70,71,72 and tuneable high sensitivity to magnetic flux. Our results demonstrate that careful optimization of both, Ramsey measurement protocol and phase estimation algorithms, can significantly enhance the precision of quantum magnetometry.

Kitaev algorithm

The standard Kitaev algorithm 60 consists of multiple steps, with the number of steps m determined by the qubit’s characteristics; typically, \(m = \left[ \log _2({{\tau ^*}/{t_\text {min}}})\right]\), where \(t_\text {min}\) is the minimum phase accumulation time constrained by the gate operation time \(T_\text {gate}\). The k-th step of the algorithm, with enumeration starting from zero, involves performing \(N_k\) steps of the following operations:

-

1.

The qubit is initialized into the state \(|\psi \rangle _\textrm{i} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(|0\rangle + |1\rangle )\) using an Hadamard gate, the algorithm can be optimized by using an initial state correction, see Methods, “Initial state correction”.

-

2.

The qubit evolves under the influence of an external magnetic flux for a duration \(\tau _\textrm{k} = 2^k t_\text {min}\).

-

3.

The qubit is rotated out of the xy-plane using a second Hadamard gate and its state is measured using a z-projective single-shot measurement. The probability of measuring a zero is given by Eq. (1).

Throughout the measurements, statistics are accumulated, and the presumed distribution is updated using Bayesian learning. Initially, it is assumed that the field lies within the range \(I_0= [\Phi _\text {min}, \; \Phi _\text {min} + {\Delta \Phi }]\), where \({\Delta \Phi }=\frac{\pi }{t_\text {min}} \left| \frac{d\omega _{01}(\Phi )}{d\Phi }\right| ^{-1}\). The number of measurements \(N_\textrm{k}\) is chosen in a way that after \(N_\textrm{k}\) measurements in the k-th step, the field range is halved with a confidence \(\varepsilon\). This means that the probability of the actual field being outside the narrowed range is \(\varepsilon\). At the first step, the phase accumulation time is doubled, ensuring the algorithm remains unambiguous within the new range. This narrowing continues through all m steps:

In the absence of dephasing, the number of measurements would remain constant across all steps. However, as evident from Eq. (3) and the relationship \(\sigma \approx 1/\sqrt{N}\), the number of measurements in the k-th step must be

assuming that the qubit is fully coherent at the initial step.

In this work, we develop a quantum metrological framework for magnetic flux sensing based on phase estimation algorithms (PEA), demonstrating enhanced precision and an expanded dynamical range. We introduce a modified PEAs that integrates signal modulation and proximity time measurements to improve sensitivity to flux variations while remaining resilient to realistic noise sources. To further advance performance, we propose the Reflected Kitaev Algorithm and systematically benchmark it towards the standard Kitaev, Fourier, and Linear Ascending Metrological Algorithm (LAMA). We also present an Enhanced LAMA variant, which extends the operational range by two orders of magnitude and significantly reduces convergence error. In the following sections, we explain the details of the proposed modifications to PEA, numerical simulations, and performance evaluations.

Detailed description of the proposed methods

Proximity time measurements

The measurement range \({\Delta \Phi }\) in the Kitaev algorithm is \({\Delta \Phi }\approx 2\pi \frac{1}{\tau _0} \left| \frac{d\omega _{01}(\Phi )}{d\Phi }\right| ^{-1}\). This range can be increased in two ways. The first one involves reducing \(\left| \frac{d\omega _{01}(\Phi )}{d\Phi }\right|\) by moving the qubit closer to the sweet spot. However, this adjustment may lead to an increased noise proportion from non-flux sources, thus reducing measurement accuracy.

The second way of increasing the measurement range is to influence the minimum phase accumulation time \(\tau _0\). This time depends on several factors. The primary constraint is the time for \({\pi }/{2}\) gates, which imposes a lower bound of \(\tau _0 > 20\) ns. Each \({\pi }/{2}\) gate requires approximately 10 ns, necessitating two such rotations per iteration. A secondary limitation is the quality of the pulse generator. Resolving the gate duration issue can increase the measurement range by two orders of magnitude.

When performing N measurements with a phase accumulation time \(\tau\), the estimated field is expressed via an Eq. (2). Given the inherent imprecision in measuring the field, we assume that the probability density of the external field \(\Phi\) is described by a sum of Gaussian distributions. Each Gaussian distribution uses a mean value given by Equation (2) and a dispersion defined by Eq. (3) and denoted as \(\sigma _{\tau , N}\). Although the use of a Gaussian distribution is not entirely rigorous, the central limit theorem justifies its application for large N. In this context, our probability density will resemble a “fence” with a period

This implies that subsequently performing a series of analogous measurements with a phase accumulation time \(\tilde{\tau }\) yields a distribution with a period of \(\frac{2\pi }{\tilde{\tau }} \left| \frac{d\omega _{01}(\Phi )}{d\Phi }\right| ^{-1}\) and a dispersion \(\sigma _\mathrm{{\tilde{\tau }, N}}\). We consider the results of various measurements to be statistically independent events. Then the final probability density can be represented as the normalized product of the first two densities. This product resembles a modulated signal, with an envelope shaped like a Gaussian distribution having a period of

and a dispersion

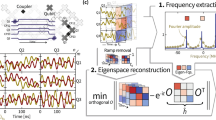

Here the index 2N indicates the total number of measurements in a given set of measurements. A qualitative plot of the probability density distribution of the field is shown in Fig. 1. Thus, the measurement range depends not on \({1}/{\tau _0}\), but on \({1}/{|\tau -\tilde{\tau }|}\), enabling its increase by a factor of \({|\tau -\tilde{\tau }|}/{\tau _0}\).

The unnormalized probability density of the field distribution, represented in arbitrary units on the Y-axis, is shown in red for the first measurement with a phase accumulation time \(\tau = \tau _0\), and in green for the measurement with \(\tilde{\tau } = 1.05\tau _0\). The resulting probability density from both measurements, along with its envelope, is shown in purple. It is seen that the phase change of the resulting signal acquires a period of \(\frac{\tau _0}{\tilde{\tau }-\tau _0}\), i.e. \(\frac{1}{1.05-1} {\Delta \Phi } = 20 {\Delta \Phi }\), which effectively expands the measurement range by factor of 20. The arrows at the top of the figure indicate the flux range in which the measurements are unambiguous for a standard measurement with \(\tau = \tau _0\) (red) and for a pair of measurements with times \(\tau = \tau _0\) and \(\tilde{\tau } = 1.05\tau _0\) (purple). The greater the range of the flow of a pair of measurements, the closer the phase selection times for each pair of measurements are to each other.

Signal modulation

We analyze a pair of measurements with phase accumulation times \(\tau\) and \(\tilde{\tau }\). This is the simplest pattern utilizing the signal modulation effect. However, the Kitaev algorithm involves multiple steps, allowing for the construction of more accurate measurement patterns. Let us consider the specific case of Equation (10) where \(\sigma _\mathrm{{\tau , N}} = \sigma _\mathrm{{\tilde{\tau }, N}}\), and assume \(\tau \approx \tilde{\tau } \gg |\tau -\tilde{\tau }| = {\Delta \tau }\). In this scenario, the dispersion is given by

Next, let us consider a set of three measurements with phase accumulation times \(\tau - {\Delta \tau }\), \(\tau\), and \(\tau + {\Delta \tau }\). This results in an envelope with the same period as the two-measurement case but with a dispersion

It can be seen that the dispersion decreases by half with \(\sigma _\mathrm{{\Omega , 2N}}^2 = 2\sigma _\mathrm{{\Omega , 3N}}^3\). Assuming \(\sigma _\mathrm{{\tau , N}} = \sigma _\mathrm{{\tilde{\tau }, N}}\) and \(\tau \gg {\Delta \tau }\), we consider that N Ramsey experiments are conducted for each phase accumulation time. Thus, measuring at three times takes 1.5 times longer than at two times. We see that according to Eq. (3), \(\sigma \propto {1}/{\sqrt{N}}\). Therefore, reducing the number of iterations per measurement at three times by a factor of 1.5 results in an envelope with a dispersion that is approximately 1.6 times smaller than that of the two-time measurement, given the same total measurement duration. Furthermore, increasing the number of measurements can further reduce the dispersion.

For measurements at k times \(\{\tau _1, \tau _2, \ldots , \tau _k\}\) with a total number of iterations N, which is equivalent to achieving dispersion \(\sigma _\mathrm{{\tau , N}}\) for a single phase accumulation time \(\tau\), the dispersion is

Reflected Kitaev algorithm

In the implementation of the Reflected Kitaev Algorithm, we seek to eliminate the phase accumulation measurements performed at short times, which are typically associated with lower classical precision. To achieve this, we relocate all steps, except for the final two, to the regime of longer phase accumulation times. The number of measurements at each time interval \(\tau\) is chosen to match that of the standard Kitaev steps for the same \(\tau\). The demonstration of the selection of phase accumulation times for the Standard and Reflected Kitaev algorithm is given in Fig. 2.

Here is a general formula for choosing the phase set times for m steps

where \(\Delta t\) is the minimum time step provided by the pulse generator. The reliability of convergence is preserved because the set of steps \(\left\{ \frac{3\tau ^*}{4}, \; \frac{3\tau ^*}{4} - {\Delta t}, \; \frac{3\tau ^*}{4} - 2{\Delta t}\right\}\) is equivalent to step \(\left\{ \tau = {\Delta t}\right\}\) in the standard Kitaev algorithm, the set \(\left\{ \frac{3\tau ^*}{4}, \; \frac{3\tau ^*}{4} - 2{\Delta t}, \; \frac{3\tau ^*}{4} - 4{\Delta t}\right\}\) is equivalent to step \(\left\{ \tau = 2 {\Delta t}\right\}\), etc, see “Signal modulation”.

It is noteworthy that the last two measurements coincide with those in the standard Kitaev algorithm, as they are conducted at longer \(\tau\), where classical precision is inherently higher. When comparing this algorithm to the standard Kitaev algorithm, it is important to emphasize that our measurements are conducted primarily in the regime of longer phase accumulation times. As a consequence, the impact of decoherence becomes more pronounced, necessitating an increased number of measurements to maintain the reliability of the results. This requirement is also applicable to standard phase estimation algorithms. Notably, there exists a minimum number of measurements necessary to ensure the algorithm’s convergence towards the true value of the field.

Pulse diagrams for Kitaev algorithm (a) and Reflected Kitaev algorithm (b). The transparent blocks represent initialization and reading, and the shaded blocks represent rotations by \(\pi /2\) around the Y axis. A two-way arrow indicates the time delay between pulses. \(\tau _0\) is minimum phase set time. (a) Four-step Kitaev performs measurements in the time range from \(\tau _0\) to \(8\tau _0\). (b) Reflected Kitaev performs measurement steps in the time range from \(4\tau _0\) to \(8\tau _0\). Due to higher estimation times, the measurement accuracy of this algorithm is slightly higher than that of Kitaev. The measurement range is also higher (by a factor of 4) since it is determined not by the minimum phase set time \(\tau _0\) but by the minimum difference between the 1st and 2nd steps \(\tau _0/4\). Improving the range by a factor of 4 requires an increase in the number of steps to 6 and some increase in the algorithm running time.

If additional measurements at the optimal point are not required to achieve the desired accuracy, the algorithm can be modified in a different manner. Specifically, we do not alter the placement of existing points in the standard Kitaev algorithm but instead add additional measurements that are spaced closer together than \(\tau _0\) between the times for the 0th and 1st steps. For simplicity, let us assume that \({t_{\text {min}}}/{\Delta t} = 2^q\), where \(q \in \mathbb {N}\). Then, the times for the m-step algorithm will be given by the set:

This algorithm does not shift the measurement points to increase accuracy but instead extends the measurement range through a modulation effect. We will refer to this action as to the small Reflected Kitaev algorithm. Figure 3 illustrates a comparative analysis of the flux probability density distribution across various steps for the standard Kitaev algorithm, the Fourier algorithm, the Reflected Kitaev algorithm, and the Enhanced Linear Ascending Metrological Algorithm.

The Kitaev algorithm, see Fig. 3a, demonstrates a gradual reduction in the uncertainty of the flux estimate over successive steps. At each step, the algorithm effectively halves the range of possible flux values by doubling the phase accumulation time. The Fourier algorithm, see Fig. 3b, uses a different approach. The first measurement is carried out when the maximum phase set time. As a result, the algorithm immediately gets narrow peaks in the probability density distribution. However, this measurement is ambiguous over the entire flux range. Therefore, further measurements are carried out at shorter phase estimation times. The extra peaks are gradually discarded until only one peak corresponds to the measured flux. Since the sets of phase estimation times are the same in the Fourier and Kitaev algorithms, and the algorithms differ only in the order of selection of these times, they give identical probability density distributions of the flux at the end of their work. It is worth noting that Kitaev gives particular results at each step of its work, while Fourier gets an unambiguous result only at the last step of the algorithm.

The Reflected Kitaev algorithm (RKA), see Fig. 3c, improves the convergence process by concentrating measurements on longer phase accumulation times, where classical precision is inherently higher. It combines the approach of the Kitaev and Fourier algorithms. This approach immediately gets narrow peaks, as in Fourier’s work. At the same time, the envelope of these peaks behaves like the density of the field distribution during the Kitaev algorithm is running. Also, the flux range in such a measurement is determined not by the Ramsey sequence minimum time but by the sample period of the pulse generator, which can be two orders of magnitude less.

Flux probability density distribution at various steps of the algorithms: (a) Kitaev, (b) Fourier, (c) Reflected Kitaev, and (d) ELAMA. The Kitaev and Fourier algorithms were computed similarly to those in Table 3. In the reflected Kitaev and ELAMA algorithms, the number of steps was reduced from 12 to 8 and from 1300 to 130, respectively, for better clarity. Kitaev’s algorithm gets a broad peak and narrows it as it works. The Fourier algorithm receives a large peak number and then discards them, leaving one correct one. The Reflected Kitaev algorithm combines these two methods in a sense. It creates a large sample of narrow peaks, as in the case of Fourier, the envelope of which is a broad peak like in Kitaev. Then, the envelope narrows until it is equal to the distance between the peaks. Thus, only one peak remains as a result. The behavior of ELAMA is generally similar to the Reflected Kitaev.

It is evident that algorithms based on closely spaced measurements cannot utilize a frequency shift (denoted as FS) approach that accounts for the measured field until they reach the stage where they begin to behave like the classical Kitaev algorithm. The details of the correction of the initial state by shifting the carrier frequency of the Ramsey pulse are given in Methods, “Initial state correction”. In the case of the reflected Kitaev algorithm, this only occurs at the final step, while in the small reflected Kitaev algorithm, it happens during the last \(m-q\) steps. The remaining steps must be performed using an FS approach that does not take the measured field into account. This slightly reduces the final accuracy, but still provides an advantage over the standard Kitaev algorithm.

Enhanced linear ascending metrological algorithm

The presence of noise leads to the need to carry out a large number (at least hundreds) of measurements to ensure the convergence of algorithms. The number of steps in Kitaev’s algorithm is small because it is limited by the \(\left[ \log _2{\tau ^*/t_{min}}\right]\). Thus, dozens of measurements are performed at each step of the algorithm. Due to the large number of measurements required at each step of the Kitaev algorithm, it becomes suboptimal, due to uncertainty of the \(N_0/N\) in Eq. (2). Based on this observation, the LAMA algorithm 73 was proposed, where the phase accumulation times grow linearly rather than exponentially as in the Kitaev algorithm. In LAMA, only a single measurement is taken at each step, compared to at least 20 measurements per step in Kitaev. Consequently, the phase accumulation times in LAMA follow the sequence \(\{\tau _0, 2\tau _0, 3\tau _0, 4\tau _0, 5\tau _0, \dots \}\). Interestingly, only one Ramsey experiment is conducted at the time \(\tau _0\), which does not provide sufficient accuracy on its own. However, the algorithm avoids issues related to resolving ambiguities on the scale of \(\pi \frac{1}{\tau _0} \left| \frac{d\omega _{01}(\Phi )}{d\Phi }\right| ^{-1}\). This effect is well explained by the modulation effect of the signal. Indeed, by performing measurements with a step size of \(\tau _0\), we obtain a large set of closely spaced points, providing high accuracy despite the lower precision of each individual measurement.

However, there are imperfections in the standard LAMA algorithm that are addressed in the proposed ELAMA algorithm. First, as described above, instead of using the minimal phase accumulation time \(\tau _{\text {min}}\), determined by the gate rotation time, we can use the minimal step size of the pulse generator, which is two orders of magnitude smaller. This will extend the measurement range by two orders of magnitude. Second, we can avoid performing measurements at small phase accumulation times, where classical accuracy is low. Indeed, the resolution of the field ambiguity is mainly determined not by the individual measurements but by the closely spaced pairs of measurements, which resolve ambiguities equally well at all \(\tau\). Thus, we can start our algorithm at time \(\tau ^*/2\), and then proceed upwards with the minimal step size provided by the pulse generator, \(\Delta t\), following the sequence \(\{\tau ^*/2, \; \; \tau ^*/2 + {\Delta t}, \; \; \tau ^*/2 + 2{\Delta t}, \; \; \tau ^*/2 + 3{\Delta t}, \dots \}\). After a certain number of steps, the probability of convergence error will be sufficiently low.

In Fig. 3d we present the ELAMA algorithm’s convergence. The figure shows a rapid narrowing of the probability density distribution across a sequence of closely spaced steps. By continuously increasing the phase accumulation times, ELAMA effectively resolves flux ambiguities and achieves high precision in fewer steps. ELAMA demonstrates the fastest and most reliable convergence, making it highly suitable for high-precision quantum metrology applications.

Numerical comparison of various algorithms

We modeled the work of different algorithms numerically to compare their effectiveness. First, we compared the operation of various algorithms without reference to real devices. That allowed us to identify the strengths of several algorithms in the general case. Next, we performed numerical calculations for a certain qubit using the Python libraries Qiskit and Braket. We have considered the noiseless model, as well as the white noise and 1/f noise model. We have presented the calculation methods and qubit parameters in Methods “Qubit parameters and calculation methods” and “Sensitivity”.

Modeling of various PEA without reference to the device

We simulate algorithms under the assumption that \(T_\textrm{reset} \gg \tau ^*\). We randomly select the field with a uniform distribution over the segment for each algorithm run. We digitize the field distribution by an array with 40, 000 possible values and considered it dimensionless. We model the single-shot measurement in the Ramsey experiment by a pseudorandom number generator. We assume that the algorithm generates an error if the square deviation of the measurement result from the correct field is more than 400. Since some algorithms converge faster than others, we assume that the algorithms continued to make measurements after convergence at the optimal point \(\tau ^*\). The results are shown in the Table 1. For compactness, we introduced the following notations: K stands for Kitaev PEA, F denotes the PEA of the quantum Fourier transform, RK denotes the Reflected Kitaev PEA, and SRK denotes Small Reflected Kitaev PEA. Furter, \(N_\textrm{tests}\) is the number of runs of the algorithm, \(N_\textrm{errors}\) is the number of runs of the algorithm during which it converged incorrectly, \(\sigma ^2\) is the variance of the measurement error, \(\sum \limits _k^m N_\textrm{k}\) is the total number of measurement iterations in one run of the algorithm, and \(N_\mathrm{{\tau = \tau ^*}}\) is the number of iterations at the optimal phase estimation time. We applied initial state correction by adjusting the carrier frequency of the Ramsey pulses. This adjustment was performed using three methods: taking into account the previously measured field (this method is denoted as MF FS), without considering the previously measured field (this method is denoted as non-MF FS), and a mixed approach combining both methods, see Methods “Initial state correction” for details.

The simulation results generally agree with the estimates and reasoning given above, in particular, MF FS surpasses non-MF FS in accuracy for the Reflected Kitaev algorithm. However, it can not guarantee convergence because this algorithm cannot uniquely determine the field before completing its work. A combination of non-MF FS and MF FS gives an average result between them both in accuracy and convergence. That allows the mixed approach to achieve sufficiently high accuracy and guaranteed convergence with a small number of measurements.

We note that ELAMA can provide reliable convergence even with the use of MF FS. Integrating the advantages of all methods, it reaches the best combination of measurement accuracy and reliability. The reasons why ELAMA is so effective require further investigation. The increase in accuracy is understandable and comparable to MF FS RK, but unlike it, ELAMA provides guaranteed convergence that surpasses all other algorithms. Perhaps this is because LAMA performs Bayesian learning after each measurement. That is 256 times in ELAMA and 512 times in LAMA, while all other algorithms perform it only 10 times. Such frequent Bayesian learning requires serious simulation capacity.

Noiseless qubit simulations

Here, we use the Local Simulator 75 qubit simulator without noise for modeling. The calculation methods are identical to those used for Table 1. The minimum phase accumulation difference was set to \({\Delta t} = 0.3\) ns, minimum phase accumulation time was set to \(t_\mathrm{{min}} = 20\) ns 74, and \(t_\mathrm{{total}}\) is the total runtime of the algorithm. The parameters of the simulated qubit are given in “Qubit parameters and calculation methods”. The results are presented in Table 2 and in Figs. 4c and 6e,f.

The demonstration of the effectiveness of various algorithms. Calculations using (a) the 1/f-noise model, (b) white noise model and (c) noiseless model. The blue line on (a) figure represents classical measurements taken at a fixed phase accumulation time. The orange line indicates the optimal accuracy that can be achieved, for example, by taking long-term measurements at the optimal phase set time after the PEA protocol completion. The green shaded area highlights the standard algorithms; the red shaded area corresponds to algorithms utilizing correction of the initial state by shifting the carrier frequency of the Ramsey pulse, frequency shift (FS); and the blue shaded area represents algorithms that leverage both FS and the signal modulation effect. Note that the frequency shift increases the accuracy, and the effect of signal modulation significantly increases the dynamical range of measurements.

It can be noted that in noiseless mode, FS does not give a significant gain in measurement accuracy. Indeed, the main advantage of FS is the optimization of the last multiplier of the Eq. (3). But without noise, it is already minimal and equal to 1. Nevertheless, FS still does a satisfactory job with the uncertainty of the sign of the inverse cosine and significantly reduces the probability of an error in the algorithm.

Another feature is that in this mode, Reflected Kitaev significantly exceeds the standard Kitaev in accuracy. This is because the main idea of Reflected Kitaev is to increase the phase set times closer to the optimal one \(\tau ^*\). The ELAMA is also superior to LAMA in accuracy. The gain here is not so high since LAMA is already close enough to the optimum, and further algorithm improvement is difficult. However, the main advantage of algorithms based on the effect of signal modulation is a gain in the dynamical range of about 2 orders of magnitude.

The 1/f noise model

In this case, we model a qubit with Gaussian dephasing corresponding to the 1/f noise model, see Fig. 5 and Methods “Sensitivity”, commonly used in experimental analyses. We selected the phase set times to be identical across all noise models for consistent comparison. These times are optimal for the 1/f noise model. But they are good enough for white noise. Obviously, in noiseless mode, it would be more profitable to make the times as large as possible, but such consideration is too idealized and uninteresting. The total running time of the algorithms is different for different noise models. This is due to the differing measurements number at each step based on the qubit attenuation measure according to the Eq. (7). The calculation methods and qubit parameters are identical to those used for “Noiseless qubit simulations”. The results are presented in Table 3 and in Figs. 4a and 6a,b. The accuracy of the magnetometer at the optimal phase accumulation time for fluxonium qubit 20 is analytically estimated in Table 6.

The dynamical range of algorithms utilizing the signal modulation effect exceeds that of standard algorithms by two orders of magnitude, reaching up to \(5.3\times 10^6 Hz^{-1/2}\). The numerical calculation of accuracy for non-PEA coincides with the analytical one. The presence of noise worsened the accuracy of the algorithms by 1.5 times. However, MF FS allows us to reduce this drop in accuracy to 1.1 for some algorithms.

Algorithms that utilise the signal modulation effect significantly outperform conventional algorithms in terms of final information gain. This advantage arises from the additional information extracted due to their extended range of measurable fields.

The white noise model

In this section we present results of simulations including only the white noise, which dephasing mechanism leading to exponential coherence decay we described in Methods “Sensitivity”. The qubit state decay rate is measured using the Ramsey experiment to conduct Bayesian learning and to select the optimal number of measurements at each step, see Fig. 5. The attenuation model is well approximated by the exponential decay. We model the Ramsey sequence process in the algorithms using the qiskit library (we do not use the pulse-level control, we artificially perform phase set by the rz gate). The calculation methods and qubit parameters are identical to those used for “Noiseless qubit simulations”. We present the results in the Table 4 and in Figs. 4b and 6c,d.

Qubit attenuation. The excited state population was calculated numerically using the qiskit library (blue solid line). The analytical fit \(e^{-t/T_2}\), where t is the waiting time (orange dashed line), corresponds to the white noise model. The analytical attenuation \(e^{-(t/T_2)^2}\) for simulation using numpy.random.rand (green dashed line) corresponds to the 1/f noise mode. Noiseless mode when simulating using the braket library (red dashed line).

Overall, the results of algorithms computed with white noise are approximately \(25\%\) lower than those obtained using 1/f noise model. This discrepancy arises primarily because the white noise simulations model relaxation with an exponential decay, while 1/f noise model assumes a Gaussian decay. The impact of this difference is less pronounced in algorithms that involve a larger number of measurements at shorter phase accumulation times (e.g. K, F, SRK), where the accuracy is less compromised. In contrast, algorithms such as RK and LAMA, which focus on measurements near the optimal phase accumulation time, exhibit a more significant decline in accuracy. Nonetheless, algorithms operating close to optimal times still maintain accuracy comparable to conventional methods and significantly outperform them in terms of dynamical range.

Discussion

Figure 6 demonstrates the information gain dynamics of various algorithms. Notice that all algorithms lie between Heisenberg limits (HL) and classical shot-noise limit (SNL), which emphasizes their quantum nature (see methods “Sensitivity”). By incorporating modifications to the phase estimation algorithm (PEA), as detailed in “Detailed description of the proposed methods”, we further enhance the scaling of the conventional PEAs towards the HL, without exploiting the conventional quantum entanglement. We utlise our modified PEAs, i.e. RK and ELAMA, and implemented our advanced measurement strategies, including the signal modulation and proximity time measurements, to optimise the phase accumulation and sensitivity precision, which results we further discuss in details and perform comparison.

The information gain depends on the accuracy and range of measurements, see Methods “Sensitivity”. We can roughly estimate it as the logarithm of the ratio of the measured field range to the resulting measurement inaccuracy. Therefore, you can raise the accuracy or expand the measured field range to improve the information gain without significantly increasing the algorithm running time. Improving the accuracy of measurements using algorithmic methods is difficult since the proposed algorithms are already quite close to the optimum of measurements in \(\tau ^*\), see Fig. 4. An increase in the measurement range is possible, for example, by using more efficient approaches to selecting phase set times, such as the signal modulation method. Thanks to it, the corresponding algorithms can receive up to 7 bits of additional information. A further increase in the accuracy of qubit control can additionally increase this value.

The Figure 6 is convenient for comparing and analysing the dynamics of algorithms. In this comparison, it should be borne in mind that algorithms using non-MF FS (indicated by the index \(^1\) and \(^3\) in all graphs and tables of this work) have a doubled measurement range compared to their counterparts, which allows them to obtain an additional bit of information.

-

Let’s highlight separately the algorithms that do not use the effect of signal modulation: Kitaev, Fourier, and LAMA (in Fig. 4 circled in green and red). They require little work time, but their information gain is also low.

-

All versions of the RK (see “Reflected Kitaev algorithm”) algorithms require more time to work, but they provide significantly more information about the field. First of all, this is achieved due to the higher measurement range, explained in details in sections “Proximity time measurements” and “Signal modulation” .

-

SRK is a cross between RK and algorithms that do not use signal modulation. In this algorithm, most measurements take place at short phase set times. That expands the range of measured fields without significantly increasing the algorithm running time. However, this approach of measuring away from the optimal point in terms of phase estimation time leads to a measurement accuracy decrease.

-

ELAMA, see section “Enhanced linear ascending metrological algorithm”, provides a wide dynamical range and the highest measurement accuracy, but its convergence takes a long time. The long-running time is because this algorithm steps fill the entire time-space from \(\tau ^*/2\) to \(\tau ^*\) in increments of \(\Delta t\). With the discussed parameters consideration of the qubit and pulse generator, this is 1300 measurements, while about 400 is sufficient for reliable algorithm convergence for a given range of fields. If the algorithms are run on qubits with a shorter dephasing time or using generators with a lower digitization step, the ratio \(\frac{\tau ^*}{2\Delta t}\) will decrease, and ELAMA’s operating time will be closer to RK’s operating time. At the same time, ELAMA will retain the advantages of accuracy and reliability.

In addition, we compare algorithms performance, by focusing on the modified PEAs which achieved the best results. We summarize their strengths and weaknesses, and present the conditions under which the algorithm choice is optimal, see Table 5:

-

\(\text {K}^3\) and \(\text {LAMA}^2\) take the least time. \(\text {LAMA}^2\) has a higher accuracy, and \(\text {K}^3\) has a higher dynamical range. Of the shortcomings, \(\text {K}^3\) more often makes convergence errors. These algorithms are preferred if fast measurements are required and there is no need for a wide measurement range.

-

\(\text {SRK}^3\) is the fastest algorithm providing a wide dynamical range of measurements. However, it pays for this with low accuracy. This algorithm is preferable if fast measurements are required and there is a need for a wide measurement range, while high accuracy is not necessary.

-

\(\text {RK}^2\) and \(\text {RK}^3\) provide good accuracy and high measurement range with moderate operating time. \(\text {RK}^2\) wins in terms of accuracy, but it cannot ensure the reliability of convergence. \(\text {RK}^3\) is worse in accuracy but better in dynamical range and reliability.

-

\(\text {ELAMA}^2\) is the most powerful tool in terms of accuracy and reliability. It surpasses \(\text {RK}^3\) in accuracy, even if additional measurements are carried out at the optimal time point (designation \(\text {RK}^3_*\)), although \(\text {RK}^3_*\) wins in terms of range. Of the disadvantages, \(\text {ELAMA}^2\) requires high execution time and capacity of classical computational resources.

The information gain of various algorithms as a function of the total phase accumulation time (a,c,e) and the total runtime of the algorithm (b,d,f) is calculated using 1/f-noise model (a,b), white noise model (c,d) and noiseless model (e,f) of the Ramsey experiment. All algorithms were tested under the same parameters as those listed in Tables 3 and 4. The indices \(^1\), \(^2\), and \(^3\) denote algorithms that do not use, fully use, and partially use the already measured field, respectively. The black lines in the left-hand figures represent the shot noise limits (SNL): the solid line corresponds to measurements starting at \(0.15\,\text {ns}\), applicable to the Reflected Kitaev FS non-MF (\(\text {RK}^1\)), Reflected Kitaev FS Mixed (\(\text {RK}^3\)) and Small Reflected Kitaev FS Mixed (\(\text {SRK}^3\)) algorithms; the dash-dotted line corresponds to measurements starting at \(0.3\,\text {ns}\), applicable to the Reflected Kitaev (RK), Reflected Kitaev FS MF (\(\text {RK}^2\)) and ELAMA FS MF (\(\text {ELAMA}^2\)) algorithms; the dashed line corresponds to measurements starting at \(10\,\text {ns}\), applicable to the Kitaev FS non-MF (\(\text {K}^1\)) and Kitaev FS Mixed (\(\text {K}^3\)) algorithms; and the dotted lines represent the shot noise limits for measurements starting at \(20\,\text {ns}\), applicable to the LAMA, LAMA FS MF (\(\text {LAMA}^2\)), Kitaev (K), Kitaev FS MF (\(\text {K}^2\)), Fourier (F), and Fourier FS MF (\(\text {F}^2\)) algorithms. The blue lines indicate the corresponding Heisenberg limits (HL). All algorithms lie between SNL and HL, which confirms the calculation’s correctness and the algorithm’s quantum nature. The pace of information gain of algorithms using the effect of “signal modulation” is higher than that of Kitaev and lower than that of Fourier, which is consistent with the data in Fig. 3. Note that both the RK and ELAMA algorithms near completion exhibit a transition from HL scaling to a slope similar to SNL behavior.

Conclusions

We have carried out a comprehensive study of phase estimation algorithms applied to quantum magnetometry, particularly focusing on superconducting qubits. By systematically analyzing both standard and optimized algorithms, including the Kitaev, Fourier, and our proposed Reflected Kitaev (RK) and Enhanced Linear Ascending Metrological Algorithm (ELAMA), we demonstrated significant improvements in magnetic flux sensitivity and dynamical range. Our results show that the optimizations we introduced, such as signal modulation and the correction of initial states through Ramsey pulse frequency shifts, enable the RK and ELAMA to outperform standard methods in both dynamical range and precision. ELAMA’s enhanced performance, especially at longer phase accumulation times, positions it as a robust tool for quantum-enhanced magnetometry, surpassing the standard noise limit and approaching HL scaling with fewer measurement steps. Although RK showed slightly less accuracy than ELAMA, it offers larger dynamical range, and requires much less classical computational resources since it less often conducts Bayesian Learning.

Future research will explore additional enhancements to quantum magnetometry, such as the use of entangled qubits and multilevel artificial atoms, which promise to further improve sensitivity. Moreover, the integration of quantum error correction techniques could extend coherence times and lead to practical implementations of quantum-enhanced magnetometry across a broader range of systems. These developments will pave the way for even greater accuracy in fundamental physics measurements and applications requiring extreme precision, such as gravitational wave detection and secure communication protocols.

Methods

Initial state correction

Correction of the initial state of \(|\psi \rangle _i\) can enhance the sensitivity and solve the ambiguity of the inverse cosine sign problem. The correction consists of an additional \(\phi _z\) rotation, which can be carried out either by changing the carrier frequency of the Ramsey pulses or by applying an additional field to the measuring contour of the qubit. We will consider rotations by changing the pulse frequency carrier by \(-\omega ^{shift}_{e}\) since this method does not require an additional control line connected to the qubit. In this case, \(\phi _z = {\omega ^\textrm{shift}_\textrm{e}} \tau\).

We use three types of frequency shifts in this work.

-

1.

The frequency shift for the Fourier algorithm consists of shifting the frequency at the \(k\ne 0\)-th step by

$$\begin{aligned} -\omega ^\textrm{shift}_\textrm{e,k} = \left| \frac{d\omega _ {01} (\Phi )}{d\Phi } \right| \Phi _\mathrm{k-1}, \end{aligned}$$(17)where \(\Phi _\mathrm{k-1}\) is one of the most likely values of the field measured at the \(k-1\)-th step.

-

2.

Frequency shift 69 without using the already measured field (non-MF FS) for the rest of the algorithms consists of splitting a set of N measurements at a given time \(\tau\) into two equal subsets of N/2 measurements. We conduct the first subset of measurements with no changes and do the frequency shift

$$\begin{aligned} -\omega ^\textrm{shift}_\textrm{e} = \frac{\pi }{2 \tau }, \end{aligned}$$(18)in the second subset.

-

3.

The frequency shift using the already measured field \(\Phi\) (MF FS) consists of shift

$$\begin{aligned} -\omega ^\textrm{shift}_\textrm{e,k} = \frac{\pi }{2 \tau } - \left| \frac{d\omega _ {01} (\Phi )}{d\Phi } \right| \Phi \end{aligned}$$(19)for measurements on time \(\tau\). We do not carry out the frequency shift on the zero measurement, at which we do not know anything about the field yet.

We also use a mixed shift, which conducts MF FS on one set of steps and non-MS FS on the other set. In Kitaev’s algorithm, non-MF FS is performed only at the first step. In the small Reflected Kitaev algorithm, we perform non-MF FS at the first q steps. In the Reflected Kitaev algorithm, we perform non-MF FS at all steps except the last one. The remaining steps use MF FS.

Qubit parameters and calculation methods

The Hamiltonian of the fluxonium is given by

where \(E_\textrm{C}=\frac{e^2}{2C}=1.398\,\text {GHz}\), \(E_\textrm{L}=\frac{(\Phi _0/2\pi )^2}{L} = 0.523\,\text {GHz}\), and \(E_\textrm{J}=I_\textrm{c}\frac{\Phi _0}{2\pi }=2.257\,\text {GHz}\) are the charging, inductive, and Josephson energies, respectively. Here, \(\Phi _0 = \frac{h}{2e}\) is the magnetic flux quantum, \(\varphi _{\text {ext}} = 2\pi \frac{\Phi _{\text {ext}}}{\Phi _0}\) is the phase induced by the external flux \(\Phi _{\text {ext}}\), \(\hat{\varphi }\) is the superconducting phase of the island, \(\hat{n}\) is the number of Cooper pairs on the capacitor, and \(n_g\) is the offset charge on the island 20.

The potential energy of the superconducting loop containing the Josephson junctions array is approximated by \(U(\hat{\varphi }) = -E_\textrm{J}\cos (\hat{\varphi }+\varphi _{\text {ext}}) + \frac{1}{2}{E_\textrm{L}} \hat{\varphi }^2 + E_\textrm{J}\), and it strongly depends on the external flux. In Fig. 7 we show: Fig. 7a potential energy of fluxonium at half flux a quantum; Fig. 7b numerically evaluated spectra of the first four energy levels; and Fig. 7c,d shows phase and charge matrix elements for corresponding transitions. The qubit’s main transition frequency, denoted as \(\omega _{01}\), is related to the effective magnetic moment \(\mu\), which quantifies the sensitivity of the qubit to changes in the magnetic flux.

The optimal point for magnetometry selected close to the maximum of the derivative of the qubit’s main transition \({d\omega _ {01}}/{d\Phi }\), see Fig. 7e, accounting the shift to avoid crossing of the interlevel transition spectra and considering the decrease of the 1/f flux noise contribution, and thus maximizes the sensitivity to the external flux.

Spectral characteristics of fluxonium qubit 20. (a) Potential energy \(U(\varphi )\) of fluxonium at half flux a quantum of the external flux \(\frac{\Phi _{ext}}{\Phi _{0}} = 0.5\). (b) Spectra of the main transitions in fluxonium: \(\omega _{01}\), \(\omega _{12}\), \(\omega _{13}\), \(\omega _{23}\). (c,d) Phase and charge matrix elements for transitions \(|0\rangle \rightarrow |1\rangle\), \(|1\rangle \rightarrow |2\rangle\), \(|1\rangle \rightarrow |3\rangle\), \(|2\rangle \rightarrow |3\rangle\). (e) The derivative of the qubit’s main transition frequency with respect to the magnetic flux, denoted as \(\dfrac{d\omega _ {01}}{d\Phi }\). The frequencies of transitions \(|0\rangle \leftrightarrow |1\rangle\), \(|1\rangle \leftrightarrow |2\rangle\), and \(|2\rangle \leftrightarrow |3\rangle\) intersect near the maximum of the derivative of \(\dfrac{d\omega _ {01}}{d\Phi }\). At the same time, the matrix elements of transitions \(|1\rangle \leftrightarrow |2\rangle\) and \(|2\rangle \leftrightarrow |3\rangle\) are not zero. Therefore, it is necessary to choose the measurement point carefully, according to the possibility of leakage of states.

The algorithm for the calculation consists of the following steps:

-

Analysing the qubit parameters and identifying the range of the maximum sensitivity of the qubit to the external flux \(\max |d\omega _ {01}/d\Phi |\), see Table 6.

-

Determining the decoherence time \(T_2\) and the optimal phase accumulation time \(\tau ^*\) for the given external flux value, see Table 6.

-

Estimating the classical measurements accuracy at the optimal phase accumulation time for magnetic flux sensitivity \(A_{\text {quant}}\) (Eq. 4) and field dynamical range \(\frac{\Delta \Phi }{A_{\text {quant}} }\), denoted according to 16, see Table 6.

-

Selecting the nature of the dephasing according to the analytical solution (see “The 1/f noise model” for details). Next, to numerically verify the measurement accuracy without using the phase estimation algorithm (row “non PEA” in Table3). Then, to ensure consistency between the analytical and numerical calculations.

-

Performing the standard protocol for evaluating the dephasing rate of the qubit using a simulation of the Ramsey experiment, see “The white noise model” for details and Fig. 5.

-

Selecting a phase estimation algorithm and determining the optimal number of the steps based on the obtained optimal phase accumulation time.

-

Executing Monte Carlo simulations and recording the resulting parameters of the algorithms in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Sensitivity

The performance of quantum sensing algorithms can be quantified using the sensitivity and the total time to reach the final result. To analyze the proposed modified PEAs algorithms, how they evolve during the field acquisition and compare their efficiency, we utilize the concept of the information gain 16. The amount of information acquired during a particular step of the algorithm evolution can be explained via the Shannon entropy. The Shannon entropy of the magnetic flux probability density after the \(n_{th}\) step is given by:

where k is the number of field digitization steps, \(P_{\Phi , i}^n\) is the estimated probability to measure flux \(\Phi _i\) after the \(n_{th}\) step of the algorithm, and \(\{\Phi _i\}\) denotes the partitioning of the interval \([\Phi _{\text {min}}, \Phi _{\text {min}} + \Delta \Phi ]\) into k equal segments. \(S^n_{\Phi }\) depends on the outcomes of all measurements up to and including step n. At the start of the algorithm, the initial uniform distribution, is characterized by the maximum entropy \(S^{\text {init}}_{\Phi } = \log _2{k}\). The information gain is given by \(\Delta I^n = S^{\text {init}}_{\Phi } - S^n_{\Phi }\), providing the amount of information acquired by the algorithm during the measurement.

Corresponding to the metrology using a superconducting qubit, i.e. fluxonium described by the Hamiltonian Eq. (20), the precision of flux estimation, see Eq. (3), in a standard (classical) measurement scales as \(\delta \Phi _\text {SNL} \propto \frac{1}{\sqrt{t}}\). The ultimately attainable precision limited by the scaling law arising from the Heisenberg relation \(\delta (\Delta E(\Phi )) \ge \frac{2\pi \hbar }{t}\), considering Eq. (21), for fluxonium qubit is given by: \(\delta \Phi \ge \frac{2\pi \hbar S}{\mu t} \sim \frac{1}{t}\).

The standard (classical) measurement is performed at a minimal effective phase accumulation time \(\tau = \tau _0 \ll T_2\). In our simulations, we optimize the phase accumulation time \(\tau\); the qubit performance is characterized by the dephasing time \(T_2\), a critical parameter for quantifying quantum performance. The dephasing rate, \(T_2^{-1}\), is determined by the energy relaxation time \(T_1\) and the pure dephasing rate \(\Gamma\), following the relationship \(T_2^{-1} = (2T_1)^{-1} + \Gamma\).

The dominant dephasing mechanisms in superconducting qubits include white noise, leading to exponential coherence decay described by \(\gamma (\tau ) = \exp (-\Gamma _{\text {wn}} \tau )\), and 1/f-noise, characterized by Gaussian decay \(\gamma (\tau ) = \exp [-(\Gamma _{1/f} \tau )^2]\). The latter primarily arises from magnetic flux fluctuations and environmental two-level systems (TLS). To investigate these mechanisms, we performed numerical simulations using three distinct platforms: Braket 75, for an ideal noiseless qubit model; Qiskit-aer.AerSimulator 76,77, assuming white noise as a simplified decoherence representation; and numpy.random.rand(...) 78, capturing the more realistic 1/f-noise effects. In this framework, the qubit interacts with a classical noise source \(\nu (t)\), inducing a stochastic phase shift \(\delta \phi = \int \nu (t) \partial \omega _{01}/\partial \nu , dt\). The resulting coherence decay function, \(\gamma (\tau ) \equiv \langle e^{i \delta \phi } \rangle\), is determined by the noise spectral density \(S_\nu (\omega )\). Specifically, white noise with constant spectral density \(S_{\nu } = S_{\text {wn}}\) yields exponential decay with \(\Gamma _{\text {wn}} = \frac{1}{2} S_{\text {wn}} (\partial \omega _{01}/\partial \nu )^2\). Conversely, 1/f-noise produces a Gaussian decay, with dephasing rate \(\Gamma _{1/f} \approx (|\partial \omega _{01}/\partial \nu |)\sqrt{S_{1/f} |\ln (\omega _c \tau )|/2\pi }\).

Flux noise is crucial for fluxonium-based quantum sensing and arises predominantly from magnetic flux fluctuations through the superconducting loop, manifesting primarily as 1/f-type noise at low frequencies. The high inductance of fluxonium, achieved through an array of Josephson junctions forming the superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID), enhances its sensitivity to external magnetic fields but simultaneously increases susceptibility to flux-induced dephasing. For fluxonium qubits, the intrinsic inductance substantially exceeds that of conventional SQUIDs or transmon qubits, enhancing the effective antenna area but also amplifying the impact of flux noise. Mitigating flux noise involves optimizing qubit design and fabrication techniques to reduce two-level system (TLS) density and flux vortex trapping. Advanced approaches, such as integrating auxiliary antennas through flux transformers 69 or careful geometric design of the SQUID loop 17, offer pathways to significantly improve flux noise resilience and thus enhance the overall accuracy and sensitivity of fluxonium-based quantum magnetometers.

Data Availability

All relevant data and figures supporting the main conclusions of the document are available on request to the corresponding authors, Azat Gubaydullin (azg@terraquantum.swiss) and Valerii Vinokur (vv@terraquantum.swiss).

References

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Advances in quantum metrology. Nat. Photon. 5, 222–229 (2011).

Degen, C. L., Reinhard, F. & Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035002 (2017).

Tetienne, J.-P. et al. Quantum imaging of current flow in graphene. Sci. Adv. 3, 1602429 (2017).

Paulsen, M. et al. An ultra-low field SQUID magnetometer for measuring antiferromagnetic and weakly remanent magnetic materials at low temperatures. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 94, 103904 (2023).

van Heck, B., Fuchs, T., Plugge, J., Bosch, W. A. & Oosterkamp, T. H. Magnetic cooling and vibration isolation of a sub-kHz mechanical resonator. J. Low Temp. Phys. 210, 588–609 (2023).

Zhang, R. et al. Recording brain activities in unshielded earth’s field with optically pumped atomic magnetometers. Sci. Adv. 6, 8792 (2020).

Faley, M. I. et al. High-Tc SQUID biomagnetometers. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 30, 083001 (2017).

Vinding, M. C. et al. The Swedish National facility for magnetoencephalography Parkinson’s disease dataset. Sci. Data 11, 150 (2024).

Fu, K.-M.C., Iwata, G. Z., Wickenbrock, A. & Budker, D. Sensitive magnetometry in challenging environments. AVS Quantum Sci. 2, 044702 (2020).

Goldie, D. J., Withington, S., Thomas, C. N., Ade, P. A. R. & Sudiwala, R. V. A route to large-scale ultra-low noise detector arrays for far-infrared space applications. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2206.15151. arXiv:2206.15151 (2022).

Casola, F., Van Der Sar, T. & Yacoby, A. Probing condensed matter physics with magnetometry based on nitrogen-vacancy centres in diamond. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 17088 (2018).

Ma, et al. Adaptive cold-atom magnetometry mitigating the trade-off between sensitivity and dynamic range. Sci. Adv.11, eadt3938. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adt3938 (2025).

Kleiner, R., Koelle, D., Ludwig, F. & Clarke, J. Superconducting quantum interference devices: State of the art and applications. Proc. IEEE 92(10), 1534–1548 (2004).

Cantor, R. & Koelle, D. Practical DC SQUIDS: Configuration and performance. In The SQUID Handbook, 171–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/3527603646.ch5 (Wiley, 2004).

Koch, J. et al. Charge-insensitive qubit design derived from the Cooper pair box. Phys. Rev. A 76, 042319 (2007).

Danilin, S. et al. Quantum-enhanced magnetometry by phase estimation algorithms with a single artificial atom. NPJ Quantum Inf. 4, 29 (2018).

Danilin, S., Nugent, N. & Weides, M. Quantum sensing with tunable superconducting qubits: optimization and speed-up. New J. Phys. 26, 103029 (2024).

Gusarov, N., Perelshtein, M., Hakonen, P. & Paraoanu, G. Optimized emulation of quantum magnetometry via superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. A 107, 052609 (2023).

Manucharyan, V. E., Koch, J., Glazman, L. I. & Devoret, M. H. Fluxonium: single cooper-pair circuit free of charge offsets. Science 326, 113 (2009).

Bao, F. et al. Fluxonium: An alternative qubit platform for high-fidelity operations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 010502 (2022).

Somoroff, A. et al. Millisecond coherence in a superconducting qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 267001 (2023).

Sekatski, P., Skotiniotis, M., Kołodyński, J. & Dürr, W. Quantum metrology with full and fast quantum control. Quantum 1, 27 (2017).

Zemlyanov, V. V. et al. Phase estimation algorithm for the multibeam optical metrology. Sci. Rep. 10, 8715 (2020).

Lesovik, G. B., Suslov, M. V. & Blatter, G. Quantum counting algorithm and its application in mesoscopic physics. Phys. Rev. A 82, 012316 (2010).

Griffiths, R. B. & Niu, C.-S. Semiclassical Fourier transform for quantum computation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 3228 (1996).

Suslov, M. V., Lesovik, G. B. & Blatter, G. Quantum abacus for counting and factorizing numbers. Phys. Rev. A 83, 052317 (2011).

Zopes, J. & Degen, C. L. Reconstruction-free quantum sensing of arbitrary waveforms. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 054028 (2019).

Shor, P. W. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. In Proc. 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 124–134 (1994).

Smolin, J. A., Smith, G. & Vargo, A. Oversimplifying quantum factoring. Nature 499, 163–165 (2013).

Harrow, A. W., Hassidim, A. & Lloyd, S. Quantum algorithm for linear systems of equations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 150502 (2009).

Lebedev, A. V., Treutlein, P. & Blatter, G. Sequential quantum-enhanced measurement with an atomic ensemble. Phys. Rev. A 89, 012118 (2014).

Vaidman, L. & Mitrani, Z. Qubits versus bits for measuring an integral of a classical field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 217902 (2004).

Giedke, G. et al. Quantum measurement of a mesoscopic spin ensemble. Phys. Rev. A 74, 032316 (2006).

Said, R. S., Berry, D. W. & Twamley, J. Nanoscale magnetometry using a single-spin system in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 83, 125410 (2011).

Higgins, B. L. et al. Entanglement-free Heisenberg-limited phase estimation. Nature 450, 393–396 (2007).

Waldherr, G. et al. High-dynamic-range magnetometry with a single nuclear spin in diamond. Nat. Nanotech. 7, 105–108 (2012).

Budker, D. & Romalis, M. Optical magnetometry. Nat. Phys. 3, 227–234 (2007).

Wood, A. A. et al. T2-limited sensing of static magnetic fields via fast rotation of quantum spins. Phys. Rev. B 98, 174114 (2018).

Wood, A. A., Stacey, A. & Martin, A. M. DC quantum magnetometry below the Ramsey limit. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 054019 (2022).

Puebla, R. et al. Versatile atomic magnetometry assisted by Bayesian inference. Phys. Rev. Appl. 16, 024044 (2021).

Baumgart, I., Cai, J.-M., Retzker, A., Plenio, M. B. & Wunderlich, C. Ultrasensitive magnetometer using a single atom. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 240801 (2016).

Wang, N. et al. Zero-field magnetometry using hyperfine-biased nitrogen-vacancy centers near diamond surfaces. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 013098 (2022).

Wolf, T. et al. Subpicotesla diamond magnetometry. Phys. Rev. X 5, 041001 (2015).

Schumacher, B. Quantum coding. Phys. Rev. A 51, 2738 (1995).

Deutsch, D. Quantum theory, the Church—Turing principle and the universal quantum computer. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 40097–40117 (1985).

Shor, P. W. Scheme for reducing decoherence in quantum computer memory. Phys. Rev. A 52, R2493(R) (1995).

Knill, E. & Laflamme, R. Theory of quantum error-correcting codes. Phys. Rev. A 55, 900 (1997).

Beckman, D., Chari, A. N., Devabhaktuni, S. & Preskill, J. Efficient networks for quantum factoring. Phys. Rev. A 54, 1034 (1996).

Il’ichev, E. & Greenberg, Ya. S. Flux qubit as a sensor of magnetic flux. EPL 77, 58005 (2007).

Barends, R. et al. Coherent Josephson qubit suitable for scalable quantum integrated circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 080502 (2013).

Kumar, P. et al. Origin and reduction of \({1}/{f}\) magnetic flux noise in superconducting devices. Phys. Rev. Appl. 6, 041001(R) (2016).

Anton, S. M. et al. Magnetic flux noise in dc SQUIDs: Temperature and geometry dependence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 147002 (2013).

Bialczak, R. C. et al. 1/f flux noise in Josephson phase qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 187006 (2007).

Yoshihara, F., Harrabi, K., Niskanen, A. O., Nakamura, Y. & Tsai, J. S. Decoherence of flux qubits due to 1/f flux noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 167001 (2006).

Lutchyn, R., Glazman, L. & Larkin, A. Quasiparticle decay rate of Josephson charge qubit oscillations. Phys. Rev. B 72, 014517 (2005).

Rower, D. A. et al. Evolution of \({1}/{f}\) flux noise in superconducting qubits with weak magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 220602 (2023).

Mehmandoost, M. & Dobrovitski, V. V. Decoherence induced by a sparse bath of two-level fluctuators: Peculiar features of \(\frac{1}{f}\) noise in high-quality qubits. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 033175 (2024).

Krause, J. et al. Quasiparticle effects in magnetic-field-resilient 3D transmons. Phys. Rev. Appl. 22, 044063. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.22.044063 (2024).

Zhuang, Z., et al. Non-Markovian Relaxation Spectroscopy of Fluxonium Qubits https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.16381. arXiv:2503.16381 (2025).

Kitaev A. Y., Quantum measurements and the Abelian stabilizer problem. ArXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.quant-ph/9511026. arXiv:quant-ph/9511026 (2005).

Cleve, R., Ekert, A., Macchiavello, C. & Mosca, M. Quantum algorithms revisited. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 454, 339–354 (1998).

van Dam, W., D’Ariano, G. M., Ekert, A., Macchiavello, C. & Mosca, M. Optimal quantum circuits for general phase estimation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 090501 (2007).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information: 10th Anniversary Edition (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

McEwen, M. et al. Removing leakage-induced correlated errors in superconducting quantum error correction. Nat. Commun. 12, 1761 (2021).

Magnard, P. et al. Fast and unconditional all-microwave reset of a superconducting qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 060502 (2018).

Abdumalikov, A. A. Jr. et al. Experimental realization of non-Abelian non-adiabatic geometric gates. Nature 496, 482–485 (2013).

Rower, D. A. et al. Suppressing counter-rotating errors for fast single-qubit gates with fluxonium. PRX Quantum 5, 040342 (2024).

Chang, T., Cohen, T., Holzman, I., Catelani, G. & Stern, M. Tunable superconducting flux qubits with long coherence times. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 024066 (2023).

Slepnev, V., Gubaydullin, A. & Vinokur, V. Fluxonium-based superconducting qubit magnetometer: optimization of phase estimation algorithms. Phys. Rev. B 110, 214423 (2024).

Nguyen, L. B. et al. High-coherence fluxonium qubit. Phys. Rev. X 9, 041041 (2019).

Somoroff, A. et al. Millisecond coherence in a superconducting qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 267001 (2023).

Somoroff, A. et al. Fluxonium qubits in a flip-chip package. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 024015 (2024).

Perelshtein, M. R. et al. Linear ascending metrological algorithm. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 013257 (2021).

Shirer, K. Subsampling techniques for achieving waveform precision in picoseconds. Zurich Instruments (2022).

Amazon Braket SDK: LocalSimulator (Version v1.88.2.post0). https://github.com/aws/amazon-braket-sdk-python

Aleksandrowicz, Gadi et al. Qiskit: An open-source framework for quantum computing. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2562110 (2019).

Qiskit Aer: High-performance simulator for quantum circuits (Version Qiskit 1.3.0). Qiskit Development Team. https://docs.quantum.ibm.com/

Harris, C. R. et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by Terra Quantum AG. We are grateful to G. S. Paraoanu, N. S. Kirsanov, A. V. Lebedev, G. Blatter, and M. Perelstein for discussions.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The work was supported by Terra Quantum AG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G., V.S., and V.V. conceptualized the work, V.S., A.G., and V.V carried out calculations, all authors discussed the results, V.S., A.G., and V.V. wrote the manuscript text, V.S. and A.G. prepared figures, all authors reviewed and discussed manuscript, V.V. supervised the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Slepnev, V., Gubaydullin, A. & Vinokur, V. Phase estimation algorithms for quantum enhanced magnetometry with artificial atoms. Sci Rep 16, 617 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30179-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30179-y