Abstract

In this study breakthrough methodology has been used to deliver advanced polymer composites based on polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) integrated with green-synthesized nickel metal complex (NiMC), utilizing a simple casting methodology. The structural and optical characteristics of PVA composite films were studied using XRD, FTIR, and UV-Vis spectroscopy, respectively. Band shifting in FTIR spectra and broadening of sharp peak in PVA composites compared to pure PVA establish strong interaction between NiMC and PVA functional groups. The surface of the films was examined for roughness and phase separation using FESEM investigation. Various optical models were employed to determine the optical band gap (Eg). The Eg decreased from 6.05 eV to 1.69 eV for direct and 1.21 eV for indirect transitions. The increase in Urbach energy from 0.28 to 0.62 eV was correlated with XRD results. The oscillator energy parameters were determined from the empirical Wemple-DiDomenico model. The real and imaginary dielectric constants, volume and surface energy loss functions, optical density, 3rd order susceptibility X(3), nonlinear refractive index n(2) and skin depth was studied in detail. Optical oscillator strengths(f), optical moments M− 1 and, and interband strength M− 3 were also determined. The ( J) and figure of merit (φ) versus hv were used to specify the photons that are capable to electron transfer from HOMO to LOMO orbitals. The optoelectronic parameters, including (N/M*), t, (wp ), (uopt ), (Popt ), the average interband oscillator wavelength, and average oscillator strength(So), were also determined for all the films.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal complexes have been used for diverse applications for ages, with initial instances observable to ancient civilizations. The systematic investigation and utilization of metal complexes in chemistry, especially in coordination chemistry was originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries1. Consequently, researchers and scientists are developing novel, environmentally friendly, and cost-effective materials2. The leaves of green tea after processing and preparation contain tea polyphenols, amino acids, caffeine, tannins, and saponins that comprises around [10–30% (w/w)] polyphenols and [2–4% (w/w)] caffeine. Catechins are polyhydroxy compounds that form the principal polyphenolic category in tea products. [epicatechin gallate (ECG), Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), epicatechin (EC), and epigallocatechin (EGC)] are the four primary catechins present in fresh green tea leaves, each displaying unique biological effects3,4. Previous studies established the formation of complexes between Zn²⁺ and Co²⁺ transition metal ions and phenolic chemicals from the high-weight molecular fraction obtained from green tea. Interactions between polyphenols and metal ions could impact the transfer of these metal ions and (GTD) polyphenols to metal complexes5,6. Transition metals can form stable compounds with polyphenols and precipite during preparation which is easy to separate and washing7. The metal ions are acidic and can interact with Lewis-basic molecules (polyphenols) to create acid-base complexes. Bark et al. investigated spectroscopic investigations of the interactions between catechin and metal ions, including Co2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, and Fe3+, in methanol utilizing fluorescence spectroscopy and UV-vis spectrophotometry8. Transition metals possess partially filled d-orbitals and exhibit varying oxidation states. Elements including Cu1+, Cu2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Pd2+, and Ag1+ are classified as transition metals or d-block elements9. The main difficulty is that a specific coordination environment imposes a significantly weaker ligand field on a 3 d transition metal than on (4d or 5 d) different species, as the more contracted (3d) orbitals display reduced spatial overlap with the corresponding ligand orbitals compared to the (4d or 5 d) orbitals. Consequently, metal complexes possessing partially (3d) occupied orbitals typically display many metal-centered excited states, and the electronic ground state is energetically close to each of them. The lowest excited state often controls photochemical and photophysical characteristics, rendering it the most crucial. Conversely, ligand-to-metal charge and metal-to-ligand transfers are advantageous for several purposes10. Ni2+ is the most stable oxidation state for nickel complexes11. Green tea (pair electron donors) bases are frequently employed as ligands in coordination complexes due to their capacity to interact with metal ions (Ni2+) through the nitrogen atom (N) and hydroxyl functional (OH) groups, as illustrated in Schematic 1b. In 1922, renowned scientist and Nobel Laureate Paul Sabatier assessed the advancements in catalysis within organic chemistry and emphasized the distinguishing properties of nickel catalysts. He observed, “Such a nickel can perform various tasks and tolerates its efficacy for an extended duration”12. A study conducted by Luneauto et al.13 investigates the magnetic and structural characterization of Ni2+ and Mn2+ complexes with chelating nitronyl nitroxide ligand, namely [2-(2-pyridyl)−4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-4,5-dihydro-1 H-imidazolyl-1-oxy 3-oxide (NIT2-Py)]. Researchers compared the structural and magnetic properties of these novel compounds.

The global scientific community is actively involved in the progress of green chemistry, defined by developing techniques demonstrating remarkable efficiency and environmental sustainability2. Continuing our work in utilizing green chemistry tools to synthesize new metal complexes, we used a simple technique to synthesize a polyphenol ligand from GTD to synthesize NiMCs. Holt et al.14 Present diamagnetic tetragonal and octahedral, paramagnetic tetrahedral, and square-planar Ni complexes, including what appear to be the first isolated isomers of octahedral Ni. The determinants influencing nickel’s adoption of a specific structure are also examined.

Polymer composites are highly regarded in numerous energy applications due to their stretchy properties and user-friendly nature. Significant focus has been directed on studying the optical characteristics of polymers to enhance their applicability in optical energy technologies15. Polymers have attracted significant interest in optics, electronics, and optoelectronics research.

Polymers are increasingly used in electronics engineering to manufacture nano- and microelectronic devices. Polymers are utilized in optical communication systems for optical sensing, optical filters, mode size conversion, optical or plasmonic modulators, electro-optic modulators, light emission, and fiber lasers16. The polymer matrix contributes significant characteristics like processability, solubility, and thermal stability to the systems. PVA exhibits remarkable chemical stability in organic solvents and is soluble in hot water owing to its hydrophilic properties17. In addition, biocompatible polymer material in various technological, medicinal, and biomedical applications. PVA serves as an extraordinary host material owing to its thermal stability, flexibility, optical clarity, biodegradability, chemical resistance, and mechanical strength. PVA has garnered interest owing to its non-toxic nature and its capacity for reduction18,19,20,21. PVA is a degradable polymer whose hydrolysis can be enhanced because of the existence of hydroxyl OH groups on the carbon atoms. Furthermore, it is soluble in water and possesses a hydrophilic characteristic22. The optical properties seek to enhance absorption (excited electron from the highest occupied molecular orbital states HOMO to the lowest occupied molecular orbital state LOMO), reflection, transmitted, interference, and polarization characteristics. Dopants can alter a polymer’s electrical and optical characteristics23.

Devi et al.23 research demonstrated that PVA may be efficiently doped with AgNO3 to improve its electrical conductivity and modify its conduction characteristics. The absorption edge and \(\:{(E}_{g})\) (direct and indirect) decreased from 5.30, 5.45 to 5.0, and 5.25 eV trends, with raised dopant concentrations of up to 0.5 wt% of the dopant, respectively. Ghanipour and Dorranian24 investigated the influence of silver nanoparticles in PVA on composite films’ structural and optical characteristics. The \(\:{(E}_{g})\) of the pure PVA sample is 4.96 eV. When the Ag nanoparticle concentration increases in the films, the \(\:{(E}_{g})\) reduced to 4.78 eV. Jassim et al.25 indicate that the XRD that PVA is semi-crystalline, with intensity rising alongside increased gamma irradiation dosage; it is seen that the \(\:{(E}_{g})\) for pure PVA film is 4.66 eV at 0 kGy for both forbidden and allowed transitions. The energy gap of irradiated PVA polymer increases with higher radiation doses, reaching 4.88 eV at 10 kGy and 5 eV at 15 kGy. Aziz et al.26 investigated PVA through a casting procedure to fabricate PVA/Fe3+ composite samples with FeCl3. The absorption coefficient was noted to rise, and the \(\:{(E}_{g})\) in pure PVA shifted to lower energy (from 5.34 to 2.55 eV) with increased dopant concentration. Ali et al.27 examined the enhanced optical properties of PVA, noting that an increase in Ni2+ doping concentration led to the formation of non-homogeneous nanoparticle sizes, averaging from 1.03 μm to 4.47 μm for 0.027 wt% Ni2+/PVA and NPVA5 films, respectively. UV–Vis-IR spectroscopies are employed to evaluate optical characteristics. The indirect \(\:{(E}_{g})\) reduces from 5.09 to 4.85 eV. Salman et al. synthesized a composite of PVA and Ni(CH3COO)₂, observing that the \(\:{(E}_{g})\) decreases as the weight% of Ni(CH3COO)₂ increases across several concentrations (2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 wt%). The bandgap energy (Eg) falls from 5.65 eV to 5.0 eV. Soliman et al.28 showed that the optical \(\:{(E}_{g})\) of PVA decreased with the doping of Ni nanoparticles, decreasing for direct transitions from 5.9 to 5.15 eV and for indirect transitions from 4.9 to 3.4 eV as the concentration of Ni nanoparticles in the polymer matrix increased.

This study investigates the optical characteristics of polar polymer (PVA) doped with different amounts of nickel metal complexes (NiMCs). Various filler concentrations were utilized to modify the polymer’s structure and optical physical characteristics, aiming to achieve a filled polymer with specific technological uses. This study primarily examines the absorption spectrum, energy gap, dielectric constant, refractive index, non-linear optics, figure of merit, and tail of the localized state in PVA with varying filling levels. The novelty of the current work is that the prepared metal complex were used without dry process. The results establish that prepared wet metal complexes interact strongly with the functional groups of the PVA via ligands around the metal complex. This work will open a new methodology to prepare polymer composites with good performance and well-dispersed fillers, which couldn’t be resolved in traditional methods. The current work establishes that the green approach to transfer metal salts to metal complexes is a great achievement to prepare polymer composites with enhanced optical properties, which are crucial for various technologies from the viewpoint of optical materials.

Experimental specifications

Preparation of samples

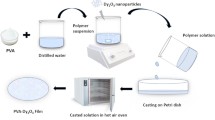

The casting method was utilized to produce polar PVA with NiMC composite films. The PVA solution, serving as the host material, was made by precisely mixing 4 g of polar PVA powder (average molecular weight of 17000–18000 g/mol from Sigma-Aldrich with 200 ml of DW at 90 °C, thereafter agitating with a magnetic stirrer for nearly two hours. When a clear and transparent solution was obtained, the PVA solution was cooled to room temperature and stirred for one day to ensure everything was thoroughly mixed.

Metal complexes can be produced in solvents by reacting nickel acetate, Ni(CH3COO)2, metal salts, and extracting GTD ligand polyphenol molecules. Ligand molecules are organic entities capable of donating electron pairs to attach to the metal ion Ni2+ via one or many sites.

For this experiment, we purchased GT at a London, England, market, and BiOCHEM for nickel acetate tetrahydrate Ni(CH3COO)2·4H2O. At approximately 95 °C, 24 g of GT leaf is added to 800 mL of DW. Whatman paper, 41with a pore radius of 20 μm (cat. no. 1441), was used to filter out any remaining residue after a 20-minute stand-up period from the extracted GTD solution. A separate flask turned pale green after dissolving 10 g of Ni(CH3COO)2 in 200 mL of DW in 30 min. By adding a Ni(CH3COO)2 to the extracted GTD solutions and stirring for about 90 min at 70 °C, NiMCs were synthesized using the Ni2+ ion from the salt and polyphenols (PPHs) in GTD. The reaction between metal salts and ligands can occur. This procedure can be considered environmentally friendly when a non-toxic solvent has been used. As the extract solution turned from green to light brown on the surface of the beaker and material precipitated to form clouds at the bottom, it was proven that Ni2+-metal ions had complexed with PPHs. The complex mixture was allowed to cool until the ambient temperature was reached. After several washes with DW, the complexes were separated in 90 mL of the solvent to obtain Ni2+-PPHs (NiMCs).

The PVA samples were doped with the NiMCs complex. The NiMC solution was gradually added to the homogeneous PVA in increments of 0–36 mL, with each addition duplicated increasing the concentration. About sixty minutes of stirring was applied to the resulting solutions. The volumes of the added complex solution were 0, 9, 18, and 36 mL, respectively, and the samples were labeled PVNiMC0, PVNiMC1, PVNiMC2, and PVNiMC3. The created films were completed by placing the composite into Petri dishes and allowing them to dehydrate at room temperature. Before character development, the materials were further dried using silica gel desiccant. Composite films and polar PVA had thicknesses between 0.010 and 0.0145 cm. Schematic 1 shows the process of making composite films, NiMCs, and PVA.

Sample characterization

An XRD model, a PANalytical X’Pert Pro powder diffractometer, was used to assess the semi-crystal structure of the polar PVA and amorphous of the composite films in their produced state. The XRD spectra were recorded using a monochromatic Cu-Kα (wavelength of 0.154) source in the 2θ series of (10°−80°) with a step 0.01°/s. A study was carried out on the samples using a Model-Shimadzu IRSpirit with QATR-S ATIR spectrophotometer to identify functional groups using FTIR spectroscopy (FTIR). The NiMC and GTD powder samples were created with KBr pellets by thoroughly mixing them. Information was documented as the transmittance ratio to wavenumber (cm− 1), falling between 400 and 4000 cm− 1. The surface morphologies of the pure PVA and composite films were examined using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM).

FESEM measurements were carried out using a MIRA3 TESCAN at 10 kV. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted using a TA Instruments SDT Q600 (USA) in an argon environment. The samples, with a mass of approximately 3.7900 mg, were subjected to heating within a temperature range of 30–800 °C at an average rate of 20 °C min− 1 to assess their thermal stability.

An ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer Lambda25 UV-Vis spectroscopy) was used to examine the optical characteristics of films29. The absorbance measurements are in the 190–1100 nm wavelength range. To do this, the powdered samples were mixed with DW and then subjected to 30 min of stirring to ensure even distribution. The solution was carefully poured into the cuvette until it was distributed correctly to get the absorbance data from the UV (Lambda 25) spectrophotometer.

Findings and analysis

Analyzing the structure

Figure 1 demonstrates that the amorphous domain of polar PVA polymer composite films is developed with the addition of NiMCs. Polar PVA exhibits three peaks at 2θ values of 19°, 27.20°, and 40.07°; they correspond to the planes (110), (200), and (210) in that order. These peaks thus confirm the crystallinity of the polar PVA matrix’s hexagonal phase. Additionally, the crystallinity results from the strong hydrogen bonding between the PVA chains30. The formation of polymer complexes is enhanced by PVA, due to its carbon chain backbone with hydroxyl groups that provide hydrogen bonding, hence considerably assisting this process31. These hydrogen atoms may be interconnected. The crystallinity of PVA can be modified through the incorporation of additives. Nagarkar and Patel showed that physically crosslinked PVA with hydroxyethyl additive can enhance the crystallinity of PVA32. Reversely, the order of increasing amorphous nature of the polymer relates to the breaking of hydrogen bonding in polar PVA33. A significant peak with a high intensity of around 19 has been detected in the XRD pattern of polar PVA. However, in the composite system, there is an increase in breadth and a drop in intensity. The reduction in peak intensity indicates the amorphous nature of the complex system. The data can be analyzed according to the criterion developed by Saadiah et al.34, which correlates peak height with crystallinity degree. The enhanced breadth and reduced intensity have been greater in NiMC-doped PVA polymer matrices35,36. Figure 1 and its inset reveal a peak at 40 in the XRD patterns of the complexes, signifying the complete interaction between polar PVA and NiMCs. The XRD analyses verified the existence of a specific complex coordination between PVA and the nickel metal complex, particularly in the final sample PVNiMC3, which exhibits a plateau region, as shown in the yellow area32.

FTIR analyzes

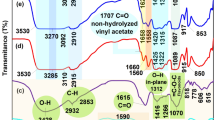

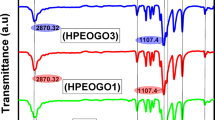

Figure 2a. The FTIR spectra of the Ni(CH3COO)2+4H2O powder show a broad band at 3476 cm− 1, ascribed to the hydroxyl groups’ O-H stretch vibration. This broadband is due to the four H2O molecules in the salt. The weak peaks at 1339 cm− 1 and 1031 cm− 1 are related to carbonate ions, which may have originated from CO2 dissolution in the atmosphere. A broad band at 552 and 678 cm− 1 is attributed to the Ni-O vibration of stretching37. Two peaks at 1411 cm− 1 and 1552 cm− 1 were assigned to asymmetry and symmetry of the C = O stretching mode of the acetate38,39. Yamashita et al. showed that the symmetric stretching vibration (COO) and the asymmetric stretching vibration (COO) of COO groups in metal carboxylates are detected at 1408 and 1585 cm⁻¹ for Ni(II) acetate40. The weak peaks at 2927 cm− 1 are ascribed to asymmetric C–H bonds41. Figure 2b illustrates the FTIR spectra of the GTD sample; the vibrational band assignment for the prominent peaks and the chemical components identified are provided in Table 1. The metal complex FTIR spectra are compared to those of the salt and ligands to identify the coordination sites. Two peaks at 1411 cm− 1 and 1552 cm− 1 in Ni acetate salt are absent in NiMC, which confirms the formation of NiMC22. The bands’ position and/or intensities will shift during coordination. The critical IR bands of the metal complexes with likely assignments are presented in Table 1. The band at 1622 cm− 1 is accredited to the (C = O) group. The broadband was observed at 3370 cm− 1, corresponding to the functional group (O–H). The absence of the band’s presence in the spectra of their respective metal complexes (MCs) is attributed to the coordination of the oxygen atom from the (OH) group to the metal ion42. The IR spectrum of the free ligand in the regions 1223 and 1622 cm− 1 is assignable to amide II (C–N) and amide I (C = O), respectively, as shown in Fig. 2c. This peak appears at 1223 cm− 1 in the metal complex, supporting the ligand coordination with central metal ion Ni(II) and shifting this band from 1242 cm− 1 in ligand to 1223 cm− 1 in metal complexes43. The 1370, 1076, and 649 cm− 1 peaks correspond to C-O bending, C-O-C, and NiO, establishing metal in coordination43,44,45.

Figure 3 clarifies the components and interactions among polar PVA and the different concentrations of the PVA/NiMC films. The broadband in the 3600–3100 cm− 1 range corresponds to the O-H stretching vibration of the polar PVA and PVA/NiMC samples46. Figure 3 indicates a significant alteration in the position of the bands in PVA films with changing NiMC concentrations. An interesting observation in all samples of PVA/NiMC composite films is that the frequency of the vibration that is symmetrical stretching of the OH group dropped to a lower wavenumber (3302 to 3272 cm− 1) compared to that of the PVA film, indicating a slight decrease in hydrogen (H) bonding within the PVA chains, and reduced the crystallinity. Interaction of metal complex (Ni) with the PVA matrix may form bonds with the hydroxyl groups of PVA, hence decreasing the hydrogen bonding between PVA molecules47. The same results were apparent in the XRD section; an interaction between NiMC and PVA molecules reduced hydrogen bonding in the PVA polymer matrix. All samples exhibit a comparable pattern. The bands at around 2941, 2353, 1729, 1246, 1086, and 836 cm− 1 correspond to NH or CH stretching, CO2 bonding, C = O stretching vibrations (the functioning group of the unhydrolyzed ester found on the PVA backbone), C-O-C bond vibrations, and CH bending, respectively48,49,50,51. All peak intensities of these bands, following the incorporation of NiMC, exhibited lowered intensity values and moved to a lower frequency range. The greatest significant decrease in intensity was recorded on the PVNiMC3 film. Finally, we can say that the frequency may also be associated with the extent of particular molecular interactions, dipole-dipole interactions, including hydrogen bonding, which can induce alterations in the surrounding media52.

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM)

The impact of metal complexes on the surface morphology of the host PVA was examined using FESEM approach. Figure 4 depicts the FESEM images for both pure PVA and PVA doped with 9, 18, and 36 mL of NiMCs at a magnification of 20 micrometers. The micrograph indicated that the doped polymer exhibited clusters of NiMC on its surface, resulting in a rough texture appearance of the PVA composite surfaces31. The FESEM images indicated that the surfaces of the composite films (Fig. 4b-c) at different amounts of Ni metal complexes (9, 18, and 36 mL, respectively) moves from smooth to rough based on the added amount of NiMC. Non existence of phase separation is an evidence for effective interactions between the polymer matrix and the Ni metal complex53,54. The white networks observed on PVA surfaces can be attributed to pure PVA nano-fibers. PVA fibers will form and become visible on the surface of the PVA film during the casting process and solvent evaporation, particularly at a magnification of 3 kx55,56.

In the composite films the PVA fibers are disrupted and aggregated particles had no fractures or agglomerations. The FESEM results support the XRD achievements in which the crystalline regions are scarified in PVA based composites. Figure 4 demonstrates that pure PVA exhibits greater crystallinity than the composite films, which may reduce intramolecular hydrogen bonding in pure PVA while enhancing intermolecular hydrogen bonding between PVA and nickel metal complexes. Furthermore, composite films exhibit an amorphous structure, whereas pure PVA displays a semicrystalline structure. NiMC doping is observed to be detectable on both the surface and within the bulk of the PVA composite57,58. In other words, NiMCs appeared as white dots on the PVA/NiMC films, compared to the PVA film missing NiMC reinforcement. The incorporation of NiMC resulted in an excellent alteration of the microstructure (Fig. 4b-d). The uniform dispersion resulted in enhanced contact and adhesion between the polymer matrix and the NiMC surface. The denser structure enhanced the tensile characteristics of the composite films59.

Thermal analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) is an effective analytical method for evaluating the thermal stability of polymers, including NiMCs, by measuring the weight loss of a sample as a function of temperature. The TGA thermogram indicates that PVA experiences four degradation stages. The initial event transpires within the temperature range of 30 to 186 °C, resulting in a weight loss of 7.819%, attributable to the elimination of residual solvent. The subsequent decomposition phase occurs between 186 and 378 °C, characterized by a weight loss of 40.60%, indicative of substantial degradation of the side group (-OH) leading to polyene formation, as well as the cleavage of the (C-C) bonds in the main chain of PVA, referred to as carbocation formation. The third and fourth region weight loss of 17.87% and 22.80% within the temperature range 378–490 °C, and 490–800 °C, respectively60. The curves in Fig. 5a-b demonstrate essentially identical behavior; however, in the second section (purple region) of the composite film, it exhibits greater stability than pure PVA. In regions three and four of the PVNiMC3 composite film, the mass loss exceeds that of pure PVA, attributable to the decomposition of inorganic as well as organic components, particularly NiO. Analysis of both pure PVA and composite films indicates that the composite film exhibits superior thermal stability, as evidenced by a total mass loss of 99.60% in the PVA film compared to 89.09% in the composite film. The advantageous enhancements in the thermal properties of the composite film can be attributed to the extensive surface area and surface modification of the nickel metal complex, which facilitates the binding of individual polymer chains and results in cross-linking of the matrix polymer chains. The additional cross-linking in the PVA/NiMC film enhances the composite film to elevated temperatures61.

Optical properties of Polar PVA and composites PVA/NiMC films

Absorbance, transmittance, optical density, and absorption coefficient

Figure 6a shows the UV-Vis absorption spectra of the polar and doped PVA films along the 190–1100 nm wavelength (λ). The free-standing PVA/NiMC films exhibit strong absorption in the visible region, spanning from 415 to 762 nm. In contrast, in polar PVA, the absorption in the UV region is 202 to 287 nm, which is associated with the n–π* transition of C = O. This shift might be due to the formation mechanism based on the coordination of NH or OH of the NiMC with OH functional groups of PVA. This takes place when polymer chains cross-link to metal complexes62. Figure 6b illustrates the transmittance of the polar PVA and PVA/NiMC films. The rise of NiMC concentration enhanced the absorbance of the composite films. The optical transmittance decreased as the concentration of NiMC increased. In the absorption region, PVA doped with 36 mL of NiMC exhibits the lowest optical transmission values. This can be attributed to the highly electronegative nature of the metal complex NiMC in PVA samples. The rise in electronegativity enhances the absorption of our samples22,63. Figure 6c illustrates the relation between wavelength (λ) and optical density (OD) for several samples. The equation determines the optical density (OD) \(\:OD\:=\:-log10\left(T\right)=\:0.434\:\alpha\:d\), illustrating the relationship between OD, film thickness (d in cm), and α. The optical density (OD) of PVA undergoes two different phases. In the 200–300 nm wavelength range, the optical density (OD) values significantly reduce as the incident wavelength \(\:\left(\lambda\:\right)\) increases. For wavelengths over 300 nm, the optical density values stabilize for the remainder of the examined spectrum. Upon comparison of A and OD curves, both exhibit analogous behavior for \(\:\left(\lambda\:\right)\). However, the spectra in the visible area exhibit exponential growth in composite samples64.

The coefficient of absorption (α) is a crucial measure for studying the variation in the band structure of polymer materials. It provides a vital understanding of the characteristics of the energy associated with the forbidden optical band gap, which will be utilized in all forthcoming applications. The coefficient of absorption can be derived from the absorption A(λ) and the thickness of the produced films, d, utilizing the Beer-Lambert law65.

I, Io are the intensity of light after and before absorption; the absorption peak in polar PVA at 312 nm shifts to 668 nm in the PVNiMC3 sample illustrated in Figure S1, indicating a transition where an electron is excited from HOMO state to LOMO by an incident photon66.

Index of refraction and dispersive energy

The index refraction (n*(λ) = n + ik) is a crucial optical characteristic that significantly influences the uses of present-day materials. The calculation real part n can be derived from the reflectance (R) and the coefficient of extinction (k) as follows67:

Figure 7a illustrates the index of refraction concerning \(\:\left(\lambda\:\right)\) in the visible spectrum (400–800 nm) for all samples. The index of refraction of all films exhibits standard dispersal behavior, wherein the index of refraction decreases with increasing \(\:\left(\lambda\:\right)\), eventually approaching a plateau in the more extended wavelength areas. NiMC doping significantly influences the modification of the mean refractive index in PVA composites. This rise may be ascribed to the enhanced density of PVA/NiMC resulting from the interaction of the metal complex with the main chain of the PVA46. A reduction in interatomic spacing is caused by the high-density production of NiMC within the PVA structure. Making waveguides, optical films, and fibers relies on knowing the film’s refractive index. Metal complexes in PVA polymeric materials cause a reduction in the density of OH groups68.

Furthermore, the dispersion parameters of the polar PVA and PVA/NiMC films are analyzed using the Wemple and DiDomenico (WDD) single oscillator model explained in Eq. (3) inside the typical dispersion zone. Examining \(\:{E}_{o}\) and \(\:{E}_{d}\) is crucial for determining the uses of the fabricated films in communication systems and spectral analysis instruments69. The values of \(\:{E}_{o}\) and \(\:{E}_{d}\) are determined from \(\:{({n}^{2}-1)}^{-1}\) against \(\:{\left(hv\right)}^{2}\), as illustrated in Fig. 7b, where the slopes correspond to \(\:{\left({E}_{o}{E}_{d}\right)}^{-1}\)and the intercepts represent \(\:\left(\frac{{E}_{o}}{{E}_{d}}\right)\). Table 2 contains the values of \(\:{E}_{o}\) and \(\:{E}_{d}\). The \(\:{E}_{o}\) and \(\:{E}_{d}\) values change with increased Ni metal complex concentration within the host PVA. The augmentation in dispersion energies pertains to enhancing the optical transition strength of the bond system62,70.

The static refractive index \(\:{n}_{o}\)(at \(\:h\upsilon\:\:=\:0\)), the static dielectric constant \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{\infty\:}\), and optical oscillator strengths (\(\:f\)) for the polar PVA and PVA/NiMC composite films were obtained using the specified relations5,71. A straightforward relationship exists between the single-oscillator \(\:{E}_{o}\) and \(\:{E}_{d}\) parameters with the interband transition strength moments’ terms. The oscillator energy \(\:{E}_{o}\) represents an “average” energy gap. Since the moments \(\:{M}_{-1}\) and \(\:{M}_{-3}\) are integral to the calculations of \(\:{E}_{o}\) and \(\:{E}_{d}\), their values are presented in Table 2 for both polar and PVA/NiMC films, necessary for understanding the mechanisms of electron transition, as illustrated in the following equation72:

Plotting \(\:{({n}^{2}\:-\:1)}^{-1}\) versus \(\:{\lambda\:}^{-2}\) exhibited a linear segment below the absorption edge, as illustrated in Fig. 7c. The index of refractions is dependent on \(\:\left(\lambda\:\right)\) allows for the determination of the extensive wavelength index of refraction \(\:\left({n}_{\infty\:}\right)\), the average wavelength of an interband oscillator \(\:\left({\lambda\:}_{o}\right)\), and the average strength of the oscillator \(\:\left({S}_{o}\right)\)for all films, utilizing the following equations derived from the model is called single-term Sellmeir oscillator73. The parameters \(\:{S}_{o}=1/slope\) and \(\:{\lambda\:}_{o}=\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{{(S}_{o\:\times\:intercept}}}\right)\), were derived from the slope and intercept of the graph plotting \(\:{({n}^{2}\:-\:1)}^{-1}\) vs. \(\:{\lambda\:}^{-2}\), as illustrated in Fig. 7c; Table 2, and are close to the respective absorption edges depicted in Fig. 5a.

Optical dielectric constant study

Furthermore, to significantly know the optical properties, we compute the optical complex dielectric constant \(\:\left({\epsilon\:}^{*}\right)\) expressed on \(\:({\epsilon\:}^{*}={\epsilon\:}_{r}+i{\epsilon\:}_{i})\). both real \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) (to estimate the density of the state) and imaginary \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\) (to evaluate the relaxation of time) parts of the dielectric constant, calculated using the following relation71,74:

The \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) describes the weakening of electromagnetic (EM) waves within materials while \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\) examines the extent to which a dielectric material absorbs electric fields due to dipole motion. Figure 8 illustrates the dielectric constants. The \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) enhanced with rising NiMC concentrations, and these findings were consistent with the similar behavior of the index of refraction as NiMC concentrations increased. The \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\) rises with increasing NiMC concentrations. The primary cause is that the disorder in the amorphous region of PVA/NiMC composite films is increasing relative to that of polar PVA. Moreover, the \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) of the samples exceed their \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\) values. This conclusion mainly results from the increased disorder in the examined polymer combination films relative to polar PVA75.

The received index of refraction data can be processed to derive the highest frequency (at \(\:{\lambda\:}^{2}\to\:0)\) dielectric constant \(\:{(\epsilon\:}_{\infty\:)}\) through methodology. The approach establishes the impact of lattice vibrational and free carrier modes on dispersion.

Where \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{\infty\:}\) is the highest frequency dielectric constant as per the initial process, \(\:N\) indicates the number of free charge carrier concentrations, \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{o}\) denoted the permittivity in free space, \(\:{m}^{*}\) the electron effective mass, c denotes the speed of light in vacuums, \(\:{n}_{o}\) represents the index of refraction at infinite wavelength. The acquired values of \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) are graphed as a function of \(\:{\lambda\:}^{2}\), as illustrated in Fig. 8a. The relationship between \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) and \(\:{\lambda\:}^{2}\) is linear for extended wavelengths. Deducing the linear segment of this relationship to zero \(\:\lambda\:\) yields the value of \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{\infty\:}\). From the slopes of these lines, the value of \(\:\left(\frac{N}{{m}^{*}}\right)\) for the examined sample was computed in accordance with Eq. 8 of the B constant. The values of \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{\infty\:}\) and \(\:\left(\frac{N}{{m}^{*}}\right)\) are presented in Table 3. The complex dielectric function \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) can be utilized to predict the optical properties of solids, which can be applied in straightforward equations to derive the associated optical values. Research has shown that the density of localized electronic states inside the forbidden \(\:\left({E}_{g}\right)\) of composite films is closely associated with the optical dielectric functions \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) and \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\).

Moreover, various other essential characteristics must be considered. The graph of \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\) vs. \(\:{{\uplambda\:}}^{3}\) (refer to Fig. 8b) was utilized to ascertain the value of \(\:\tau\:\). The \(\:\tau\:\) value was utilized to compute characteristics like plasma frequency \(\:{(\omega\:}_{p})\) optical mobility \(\:{(\mu\:}_{opt})\), and optical resistivity \(\:\left({(\rho\:}_{opt}\right)\), which can be readily derived from the \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\). Drude free electron model with the assistance of \(\:\left(\frac{N}{{m}^{*}}\right)\) magnitudes, which are derived from Eq. 9 and Fig. 8a. The values \(\:\tau\:\), \(\:{(\omega\:}_{p})\), \(\:{(\mu\:}_{opt})\), and \(\:\left({(\rho\:}_{opt}\right)\), were correlated with an increase in \(\:n\). The speed of light falls in a medium with a higher refractive index. The incorporation of PVA/NiMC elevates the electron plasma frequency \(\:{(\omega\:}_{p})\) from 1.44 × 10²⁹ to 3 × 10³⁰ Hz. When an electric field hits a polymer composite film, it creates a strong local electric field in the dipole moment. This makes the material more polarized. The addition of doping will raise the density of states and enhance the charge quantity within the polymer matrix, perhaps resulting in a reduction of resistivity76, as shown in Table 3.

Urbach energy to study the disordering

The decrease in the gap \(\:{E}_{g}\) is associated with the disorder; the disturbing of the polar polymer structure results in the appearance of localized new energy states within the forbidden band gap of the PVA. It can capture electrons between the HOMO and LOMO bands. The reduction in \(\:({E}_{g)}\) confirms the enhanced degree of disorder in the polymer layer. The width of the localized tail states within the forbidden band gap (Urbach energy \(\:{E}_{U}\)) can be verified by investigation using the following equation28.

where \(\:\alpha\:\) represents the coefficient of absorption and \(\:\alpha_\circ\) is a constant. Figure S2 illustrates the relationship between \(\:Ln\left(\alpha\:\right)\) and \(\:\left(h\upsilon\:\right)\) for the polar PVA and PVA composite films, namely the linear segment near the absorption edge77. The \(\:{E}_{U}\) values for all concentrations were computed using the inverse slope, as shown in Table 4. Urbach energy provides valuable insights into the defect levels inside \(\:{E}_{g}\) material system. The analysis of the absorption spectra (Figure S2) reveals that the tail extends to lower energies under the band edge. These can be attributed to the transitions from localized states in the (VB) tail to delocalized states in the (CB). Localized states emerge from defects and enhancements. The Urbach relation defines the absorption coefficient of amorphous materials just below the absorption edge and can be calculated using Eq. 12. The \(\:{E}_{U}\) value for polar PVA is 0.28, but for composite sample PVNiMC3, it increases to 0.62. Consequently, regarding the pattern of Urbach energy, it is interesting that the incorporation of NiMC into the PVA matrix decreases the longest-range order in the PVA film, resulting in a dispersed configuration of short-range locally accumulated textures due to the interaction between PVA and NiMC. Recently, researchers have been seeking to understand how the disorder has grown with the rise of the \(\:{E}_{U}\)5,73. The rise in Urbach energy observed in polymer composite samples is indicative of the amorphous structure, as these defects result in a distribution of localized states near the band edge.

Enhancement of optical band gap \(\:{(\varvec{E}}_{\varvec{g}})\) of the composite PVA samples

Figure 9a depicts the coefficient of absorption as a function of \(\:hv\) for samples that were synthesized at varying concentrations of NiMCs. The edge of absorption of the complex films was ascertained by extrapolating the linear segment of the \(\:hv\) versus a curve to the energy axis. With a rise in NiMC content, the ability to absorb edge changes to a lower photon energy range, suggesting that optical transitions may transpire at significantly reduced incident photon energy. The shift in the absorption edge indicates a reduction in the \(\:\left({E}_{g}\right)\) of the synthesized composite samples. The exponential behavior of the absorption edge can be ascribed to the predominant amorphous component of the composites. The absorption edge in this study decreased from 6.05 eV for polar PVA to 1.69 eV for the PVNiMC3 sample78. The redshift (to lower \(\:hv\)) of the absorption edge in the samples indicated hydrogen bonding between NiMC and the OH groups of PVA. The newly formed bonds result from alterations in crystallinity within the matrix, which subsequently reflect changes in the band gap of the synthesized films79.

Figure 9b depicts the spectra corresponding to the \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\) of the dielectric constant \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\) \(\:({\epsilon\:}_{i}=2nk)\). The optical \(\:\left({E}_{g}\right)\) were found at the intersection of the linear segments on the x-axis in Fig. 9b. The notable contributions to the optical spectra arise from the top of VBs to the bottom of CBs. The fundamental absorption edge defines the optical \(\:\left({E}_{g}\right)\) as the essential absorption edge y. A study of the optical absorption of a condensed substance is the most direct method for analyzing its electronic structure. Absorption occurs when a photon has sufficient energy to excite electrons from low-energy VBs to high-energy CBs80.

A different strategy to examine \(\:{E}_{g}\) is by optical conductivity, which \(\:{(\sigma\:}_{opt}\left)\:and\:{(\sigma\:}_{e}\right)\) are calculated using the values of \(\:n\) and \(\:\alpha\:\) via the following formula.

Figure S3(a-b) depicts the correlation between \(\:{(\sigma\:}_{opt}),\:{(\sigma\:}_{e})\:\:\)and incident photon energy \(\:\left(hv\right)\). The values of \(\:{(\sigma\:}_{opt})\) remain invariant in the lower region. This is due to the insufficient energy of the photons needed to excite the electrons in the sample. In the high photon energy area, the optical conductivity exhibits a band that changes to lower hv with rising NiMC content. This occurs because the incident photons have enough energy to effectively excite the electrons from VBs to CBs81. But as shown in Figure S3b, \(\:{(\sigma\:}_{e})\:\)has a high value in the low energy range to study \(\:{E}_{g}\)22. Both \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) and \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\) increase continuously with the rise in photon energy, although \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) exhibits too maxima. Doping typically results in a rise of \(\:\text{tan}\left(\delta\:\right)=\frac{{\epsilon\:}_{i}}{{\epsilon\:}_{r}}\), as illustrated in Figure S3c. The significant rise between 1.4 and 2.75 eV validates the energy values of the optical \(\:\left({E}_{g}\right)\); the energies within this range are suitable for optoelectronic applications. The rise in \(\:\text{t}\text{a}\text{n}\left(\delta\:\right)\) was ascribed to the absorption of an electromagnetic (EM) field82,83. Figure S3d illustrates the correlation between the quality factor (Q) of PVA films and the variation in \(\:hv\) for different doping amounts The Q values are lower at higher \(\:hv\) compared to the high and medium wavelength regions. The Q values are noted to decline significantly up to 800 nm (near 2.5 eV). The Q values for each examined films exhibit a substantial decline in the high wavelength region. Films of greater thickness are more effective than those of lesser thickness84.

Another technique used to determine\(\:{(E}_{g})\), the initial derivative of optical transmittance and reflectance respecting wavelength might be calculated to ascertain the absorption band edge \(\:{(E}_{g})\) of the composite films. The graphs of \(\:(\frac{dT}{d\lambda\:},\frac{dR}{d\lambda\:})\) against hv were illustrated, as depicted in Fig. 10(a-b). Each curve possesses a distinct minimum, corresponding to the most minor critical point on the \(\:hv\) axis, denoted as \(\:{(E}_{g})\). Thus, the absorption band edge values of the structure were found to be in the region of 1.8095 to 1.8205 eV as deposited to metal complex doping. Figure 10 illustrates the dependency of the \(\:{(E}_{g})\) derived using derivative analysis methodologies. The energy values derived from these processes match up with one another85.

Figure 10c demonstrates the absence of an absorption band for polar PVA in the visible spectrum, as indicated in Fig. 6a. The PVA polymer film is transparent to visible light. The significant absorption spectra changed to a lower \(\:hv\) as a result of the interaction between the NiMC dopant and an adjacent hydroxyl group through hydrogen bonding within the PVA matrix, PVA/NiMC polymer composites might be used as cut-off filters or optical lasers. The location of the edge of absorption has been found by extending the linear segment of the curves to null absorption \(\:\left(ln\right(A)\:=\:0)\). The results obtained are presented in Table 4. This signifies the establishment of localized energy states within the optical \(\:{(E}_{g})\)26.

The interband transition strength \(\:({J}^{*}={J}_{r}+i{J}_{i})\) incorporates the dipole selection rules for the transitions. \(\:\left({J}^{*}\right)\) is relative to the possibility of electrons transitioning from the filled VB to the vacant CB, associated to the change in the energy state, and is linked to the complex dielectric constant \(\:({\epsilon\:}^{*}={\epsilon\:}_{r}+i{\epsilon\:}_{i})\).

Where \(\:{J}_{r}\) and \(\:{J}_{i}\) symbolize both the real and imagined parts of the strength of the interband transition, \(\:m\) denotes the electron mass, \(\:e\) indicates the electron’s charge and h refers to Planck’s constant. \(\:\left({J}^{*}\right)\) is directly proportionate to the transition possibility and is measured in grams per cubic centimeter (g/cm³). For simplicity, we consider the factor \(\:\left(\frac{4\pi\:{m}^{2}}{{e}^{2}{h}^{2}}\right)\) in Eq. 15, which has a value of (8.289 × 10− 6 g.eV− 2), as unity22. The (J*) derived from Eq. 15 is illustrated in Figures S4a and S4b. It is important to know that significant absorption occurs after 5 eV for polar PVA and 1.75 eV for composite samples.

Finally, Tauc’s law can more accurately determine the kind of electron transitions (direct and indirect) and the values of \(\:{E}_{g}\). The band gap energy can, after that be computed via the Tauc formula as follows86:

Here, \(\:B\) denotes a parameter that characterizes the level of disorder in the sample. At the same time, \(\:\gamma\:\) is associated with the dominant electronic type’s transitions: direct allowed and forbidden, indirect allowed and forbidden, corresponding to values of \(\:(\frac{1}{2},\:\:\frac{3}{2},\:2,\:3)\), respectively. It is essential to ascertain both the direct and indirect optical bandgap energies of the PVA composite in its as-fabricated condition to evaluate its appropriateness for optoelectronic applications87. The \(\:{E}_{g}\) is derived from the linear intersection of the curve with the abscissa axis of the plot \(\:{\left({\upalpha\:}\text{h}\text{v}\right)}^{\frac{1}{\gamma\:}}\) vs. \(\:h\nu\:\)86,88,89. Figure 11 depicts the optical \(\:{E}_{g}\) energies from Tauc’s relationship of both polar PVA and composite PVA. Introducing metal complexes significantly decreases the band gap energy from 6.23 to 1.22 eV, signifying a drop in the polymer’s resistivity. The noted decrease is linked to structural deterioration in PVA/NiMC, leading to fragmentation and defect generation. The findings indicated that the specified direct band gap energies of PVA/NiMC films decreased from 6.13 to 1.61 eV. The indirect band gap energies decreased from 6.06 to 1.21 eV with the increasing concentration of NiMCs, as illustrated in Fig. 11and Scheme 2. The insertion of NiMC provides as the optimal filler for enhancing the optical band gap; however, Soliman et al.28 demonstrate that the optical band gaps decrease for direct transitions from 5.9 to 5.15 eV (0.75 eV) and indirect transitions from 4.9 to 3.4 eV (1.5 eV) with increased Ni nanoparticle concentration. The reduction in indirect and direct \(\:{E}_{g}\) with the rising presence of metal complexes is ascribed to defects within the band structure, which influence the absorption of light photons. The correlation between \(\:{E}_{g}\) values for direct and indirect transitions and NiMC content can be seen in Table 5. The \(\:{E}_{g}\) values are similar to those previously derived from the \(\:\alpha\:,\:{\epsilon\:}_{i},\:{\sigma\:}_{opt},\:{\sigma\:}_{e},\text{tan}\left(\delta\:\right),\:Q-factor,\:\:\frac{dT}{d\lambda\:},\frac{dR}{d\lambda\:},\:and\:\text{l}\text{n}\left(A\right)\) vs. \(\:hv\) curves.

Optical nonlinearity parameters

Moreover, the magnitude of the third-order susceptibility conveys insights into the sample’s reaction to higher laser pulses in the context of high-order phenomena. The induced polarization \(\:\left(P\right)\) at standard light intensity is a non-linear function directly proportional to the high power of the electric field \(\:\left(E\right)\). The high-order susceptibilities of all products (\(\:{\chi\:}^{\left(2\right)}\), and \(\:{\chi\:}^{\left(3\right)}\) for second-order and for third-order) and \(\:{n}^{\left(2\right)}\) (non-linear refractive index) were determined to compute the P-value. The relationship between p (polarizability) and \(\:P\) (non-linear polarization) is expressed bellow, from the quantum mechanics viewpoint \(\:{\chi\:}^{\left(2\right)}\), and \(\:{\chi\:}^{\left(3\right)}\) they are the coefficients of the tensor form77,90 :

where \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{o}\) signifies the dielectric constant in vacuum, \(\:{n}^{\left(0\right)}\)and \(\:{n}^{\left(2\right)}\) represent the linear and nonlinear refractive indices, respectively. Various empirical relationships are employed to determine the nonlinear optical properties, as illustrated in Eq. (21). The non-linear optical characteristics of polymer composites are primarily affected by the composite’s composition and the attributes of the constituent polymers. Nonlinear optics covers numerous photonics, communications, data processing, optical computation, and capacity planning applications. PVA is extensively utilized in several aspects of nonlinear optical applications. PVA doped with NiMC will be expected to exhibit enhanced nonlinear constants. The measured \(\:{n}^{\left(2\right)}\) values of PVA and composite films are depicted in Figure S5. \(\:{n}^{\left(2\right)}\) exhibits elevated values that qualify our composite film materials for creating nonlinear electrical or optoelectronic devices63,91. Nonlinear optics is extensively utilized in various domains, including laser technology, optical communication, information and image processing and storage, and optical computing. Given its extensive application in several domains, nonlinear optics possesses substantial value and profound scientific significance90,92. The values of \(\:{\chi\:}^{\left(2\right)}\), \(\:{\chi\:}^{\left(3\right)}\), and \(\:{n}^{\left(2\right)}\)evidently rise with the increase of NiMC in the PVA. The increased value of \(\:{\chi\:}^{\left(3\right)}\), pertains to metal complexes inside the polymer matrix. It refers to the dependency of the index of refraction on the energy of the photons. It is clear from the interaction of composite films with incident light results in electron excitation. The parameters \(\:{\chi\:}^{\left(2\right)}\), \(\:{\chi\:}^{\left(3\right)}\), and \(\:{n}^{\left(2\right)}\) have been investigated by implementing the other model (WDD) \(\:\left[{\chi\:}^{\left(1\right)}=\frac{{E}_{d}}{{4\pi\:E}_{o}}\:and\:{\chi\:}^{\left(3\right)}=6.82\times\:{\left(\frac{{E}_{d}}{{E}_{o}}\right)}^{4}\right]\)for the PVA system filled with NiMC. The measured nonlinear optical properties exceed those in the PVA/NiMC shown in Figure S5. Materials exhibiting improved non-linear optical physical characteristics can be utilized in non-linear optical devices28.

We also used two parameters, the first one (SELF), the surface energy loss function, to describe the electron optical transitions in the PVA/NiMC composite films. The second parameter is a VELF, which shows high- and low-frequency electron transitions in bulk materials. The SELF and VELF have been calculated by combining the \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) and \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\) components of the dielectric constants75.

The SELF and VELF of the PVA composite films with varying amounts of NiMC were computed and illustrated as a function of photon frequency \(\:\left(v\right)\), as shown in Figure S6(a, b). These figures specify that the SELF is altered due to variations in NiMC concentrations; hence, the electron conversion energy has been improved. Furthermore, VELF is altered due to the variation in the concentrations of NiMC. Also, it is seen that at any point, the VELF value exceeds the SELF-value, indicating that the energy loss of the traveling electrons within the films due to the doped NiMC particles is greater than that of those traveling on their surfaces70,75. The optical dielectric constant \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) refers to the medium’s attenuation of light speed. In contrast, the optical dielectric loss \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\) relates to energy absorption from the electric field due to dipole movement93. These results of SELF and VELF are in good agreement and similar to the curve of dielectric constant results. Energy dissipation occurs by the rapid motion of electrons traversing the bands. The components of surface and volume energy loss are associated with the rapid movement of electrons as they dissipate energy after traversing the material and its surface94.

Optical losses can be studied by various metrics derived from the computations of the complicated refractive index. Initially, the loss of tangent. The final section discusses the optical conductivity. Third, the skin depth,, indicates the distance light travels through a medium before its intensity drops to 37% of the initial value. This is expressed as \(\:D\:=\:1/\alpha\:\). Figure S6c clearly illustrates that decreases for all examined films as photon energy rises. The polar PVA film has a peak for that is minimally lossy at = 5 eV. This discusses the reason for PVA’s near transparency in the visible spectrum. The peak disappears in the other samples, indicating a favorable interaction between PVA and NiMC. The absorption is more acknowledged, as seen by a decreasing in this region for each sample16.

Significant optical parameters in device applications

The sheet resistance \(\:{\varvec{R}}_{\varvec{s}}\), thermal emissivity \(\:{\varvec{\epsilon\:}}_{\varvec{T}\varvec{h}}\) and figure of merit (\(\:{\varvec{\phi\:}}_{\varvec{f}\varvec{i}\varvec{l}\varvec{m}}\))

Another interesting parameter is the sheet resistance \(\:\left({R}_{s}\right)\) is associated with the wavelength of photons that are perpendicularly on the film’s surface or at various angles across the entire optical spectrum95, as a result, that arises from the excitation of electrons by photons striking the surface84.

Figure 12a illustrates the relationship between the sheet resistance \(\:\left({R}_{s}\right)\) and the \(\:\left(\lambda\:\right)\:\)for polar PVA and PVA/NiMC nanocomposites. Within the \(\:\lambda\:\) range of 400–1100 nm, the \(\:\left({R}_{s}\right)\) values significantly increase with the amplification of the incident photon wavelength; however, Within the \(\:\lambda\:\) range of 190–400 nm, the \(\:\left({R}_{s}\right)\) achieve an equilibrium level64. Figure 12a illustrates the variation in \(\:\left({R}_{s}\right)\) as a function of film thickness. Additionally, a reduction in \(\:\left({R}_{s}\right)\) is observed with the incorporation of NiMC into PVA; increasing the concentration of NiMC results in an increase in film thickness96.

The second measure, thermal emissivity \(\:{({\upepsilon\:}}_{th})\), refers to the photonic irritate of electrons on the surface of the films and characterizes the relative capacity of a material’s surface to emit radiation. The value of \(\:{({\upepsilon\:}}_{th})\) can be derived from Kirchhoff’s law. Figure 12b illustrates the correlation between \(\:{({\upepsilon\:}}_{th})\) and \(\:\lambda\:\) for PVA composites. The spectra of \(\:{({\upepsilon\:}}_{th})\) for PVA/NiMC were depending upon \(\:\lambda\:\), and the measured values of \(\:{({\upepsilon\:}}_{th})\) are significantly lower (~ 10− 9) than the blackbody (~ 1). The value \(\:{({\upepsilon\:}}_{th})\) is commonly acknowledged to be influenced by temperature, measurement direction, and other factors. Consequently, the estimated value of \(\:{({\upepsilon\:}}_{th})\) modifying the measurement direction and temperature may be regulated, among other variables. The behavior of \(\:{({\upepsilon\:}}_{th})\:\text{v}\text{s}.\:\lambda\:\). for the examined PVA/NiMC composites closely resemble the variation in \(\:{(\text{R}}_{s})\:\text{v}\text{s}.\:\:{\uplambda\:}\)97.

The Rs and T data were used to compute the figure of merit \(\:{(\varvec{\phi\:}}_{\varvec{f}\varvec{i}\varvec{l}\varvec{m}})\)as described by the Haacke equation98.

Simultaneously achieving optimal optical transmission and electrical conductivity (electrical sheet resistance) is challenging due to the inverse relationship between these qualities. Consequently, a figure of merit has been established to improve the physical properties of PVA/NiMC films. The merit of the composite samples was progressively enhanced with rising NiMC concentration. The current figures demonstrate significantly enhanced outcomes compared to polar PVA99. The optical transmission progressively reduced with NiMC, exhibiting small oscillations at higher wavelengths. The mean value was approximately 70 to 80% at 550 to 700 nm wavelengths. We observed the spectrum shift in the absorption edge to visible wavelengths. Concurrently, we augmented the \(\:\left({R}_{s}\right)\) to acquire specific φfilm values. The figure of merit measurements, which evaluated the optoelectrical performance of the transparent materials, demonstrated that the PVA/NiMC films were of better quality than the PVA film. From Fig. 12c, it is easy to understand that the absorption of composite films shifted to the visible region, and this is indicated in the left-hand of the exponential edge of composite samples before 400 nm wavelength the electrons do not have sufficient energy to excite from HOMO to LOMO. Still, on the left-hand side, the electrons have enough energy to excite take place. The photon energy \(\:hv\) is less than \(\:{E}_{g}\), and the materials are optically transparent. In solar cells, more absorption occurs, which means more energy conversion, enhancing φfilm. From Fig. 12c, we can calculate the optical \(\:{(E}_{g})\) from the absorption edge or significant peaks in polar PVA and PVA/NiMC samples by using (\(\:{(E}_{g}=\frac{hc}{\lambda\:})\), where (h=4.1357 × 10−15 eV/s), equal to (5.42, 1.95, 1.68, and 1.45 eV) for (PVNiMC0, PVNiMC1, PVNiMC2, and PVNiMC3) from significant wavelength, respectively100.

Understanding absorption characteristics is crucial for designing materials with high φfilm in optoelectronic applications. To compare the optical and electrical properties of both PVA and doped PVA films, we measured the transmittance at (500–800 nm) and the sheet resistance for samples as shown in Fig. 12(a and c). The \(\:\left({R}_{s}\right)\) for the polar PVA and PVNiMC3 decreased from \(\:(39\times\:{10}^{7}\:to\:3\times\:{10}^{7}\:\frac{{\Omega\:}}{sq})\). The decreased sheet resistance may be attributed to the PVA’s doping actions and establishing a conductive bridge between PVA and NiMC101. Figure 12c, it showed that the photoelectric property of composite films prepared exhibited the best φfilm value,

Conclusion

In conclusions this study has emphasized that using environmentally friendly green chemistry approaches is an easy methodology to deliver metal complexes with high absorption properties. The extracted dye of green tea which enriched with various ligands such as NH, NH2, OH, C-NH-C and C = O are crucial to synthesize NiMC from nickel acetate salt. PVA doped with NiMC (9, 18, 27, and 36 mL) was used to deliver a series of composites with good optoelectronic properties using solvent casting. The drop in intensity of the main crystalline peak of PVA around 19.7o in PVA based composites and their broadening indicates amorphous growth. FESEM results established good dispersion of NiMC through PVA host medium. The creation of new hydrogen bonding between NiMC and the OH of PVA was demonstrated, and molecular vibrations within polar PVA and PVA/NiMC were identified using FTIR. PVA demonstrated significant optical transparency and momentous absorption while incorporating with NiMCs. The electron transition characterized by Tauc’s model covers both direct and indirect mechanisms. The Urbach energy \(\:{(E}_{U})\) range from 0.28 to 0.62 eV as the metal complex concentration increases; \(\:{(E}_{U})\) and XRD studies confirm the amorphous characteristics of the composite films. Nine methodologies were utilized to determine \(\:{E}_{g}\), including\(\:\alpha\:,\:{\epsilon\:}_{i},\:{\sigma\:}_{opt},\:{\sigma\:}_{e},\text{tan}\left(\delta\:\right),\:Q-factor,\:\:\frac{dT}{d\lambda\:},\frac{dR}{d\lambda\:},\:and\:\text{l}\text{n}\left(A\right)\) vs. \(\:hv\).The optical dispersion characteristics were ascertained utilizing the WDD single-dimentional oscillator model. Single oscillator energy \(\:{E}_{o}\), dispersion energy \(\:{E}_{d}\), the longest wavelength index refraction \(\:{n}_{o}\), and average oscillator strength \(\:{S}_{o}\), and average inter-band oscillator wavelength \(\:{\lambda\:}_{o}\) are significantly influenced by NiMC doping. Furthermore, the doping concentration significantly influences the augmentation of the optical parameters \(\:({\epsilon\:}_{i},\:{\epsilon\:}_{r},\:n,\:\frac{N}{{m}^{*}},{\rho\:}_{opt},\:{\omega\:}_{p},\:and\:{\mu\:}_{opt})\) of the samples due to the complex interactions induced by hydroxyl groups in PVA. They are research studies investigating how to change microscopic nonlinear parameters, such as 3rd order susceptibility \(\:{\chi\:}^{\left(3\right)}\)and nonlinear index of refraction \(\:{n}^{\left(2\right)}\), and enhance important optical parameters like \(\:{R}_{s},\:{\epsilon\:}_{Th}\), inter-band strength \(\:J\), and figure of merit. This study offers critical insights into the unique amorphous and electronic band designs appropriate for diverse optoelectronic device applications necessitating a narrow bandgap. Low-band gap materials serve as significant candidates in producing optical waveguides, contemporary optical applications, organic semiconductors, and organic solar cells. The figure of merit parameter successfully used to separate the regions of photons which are inefficient to transfer electrons from the VB to the CB.

Data availability

The datasets produced and/or examined in this work are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yadav, S., Prasad Sonkar, S., Singh Tiwari, K. & Shukla, M. A review on sustainable synthesis methods, characterization and applications of inorganic metal complexes: recent advances and future approaches. Results Chem. 10, 101743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rechem.2024.101743 (2024).

Pathan, I. R. & Patel, M. K. A comprehensive review on the synthesis and applications of schiff base ligand and metal complexes: A comparative study of conventional heating, microwave heating, and sonochemical methods. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 158, 111464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2023.111464 (2023).

Sanaeifar, A. et al. Nondestructive monitoring of polyphenols and caffeine during green tea processing using Vis-NIR spectroscopy. Food Sci. Nutr. 8, 5860–5874. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.1861 (2020).

Pan, X., Niu, G. & Liu, H. Microwave-assisted extraction of tea polyphenols and tea caffeine from green tea leaves. Chem. Eng. Process. 42, 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0255-2701(02)00037-5 (2003).

Dana, S. B. A. & Muhammad1, S. Aziz2, the impact of green chemistry to synthesize PVA/Cobalt metal complexes (CoMCs) composites with enhanced optical behavior. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 100201 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2024.116448 (2024).

Muhammad, D. S., Aziz, D. M. & Aziz, S. B. Zinc metal complexes synthesized by a green method as a new approach to alter the structural and optical characteristics of PVA: new field for polymer composite fabrication with controlled optical band gap. RSC Adv. 14, 26362–26387. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ra04228j (2024).

Herman, M., Janiak, M. A., Sadlik, J. K., Piekoszewski, W. & Amarowicz, R. Iron, Zinc, Copper, manganese and chromium in green Teas, their transfer to extracts and correlations between contents of elements and bioactive compounds. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 72, 421–429. https://doi.org/10.31883/pjfns/156394 (2022).

Bark, K. M. et al. Studies on the interaction between Catechin and metal ions. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 33, 4235–4238. https://doi.org/10.5012/bkcs.2012.33.12.4235 (2012).

Aly, A. A., Abdallah, E. M., Ahmed, S. A., Rabee, M. M. & Bräse, S. Transition metal complexes of Thiosemicarbazides, Thiocarbohydrazides, and their corresponding carbazones with Cu(I), Cu(II), Co(II), Ni(II), Pd(II), and Ag(I)—A review. Molecules 28, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28041808 (2023).

Wegeberg, C. & Wenger, O. S. Luminescent First-Row transition metal Complexes, JACS Au 1 1860–1876. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacsau.1c00353 (2021).

Wen, J., Wang, F. & Zhang, X. Asymmetric hydrogenation catalyzed by first-row transition metal complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 3211–3237. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0cs00082e (2021).

Ananikov, V. P. Nickel: the spirited horse of transition metal catalysis. ACS Catal. 5, 1964–1971. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.5b00072 (2015).

Luneau, D. et al. Transition metal derivatives of a chelating Nitronyl nitroxide Ligand. Nickel(II) and Manganese(II) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 32, 5616–5622. https://doi.org/10.1021/ic00076a032 (1993).

Carlin, L. & OF SUBSTITUTED Some Transition Metal Complexes of Substituted Thioureas. 11. Nickel (I1) l a, 0 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01069a011 (1964).

Atta, A., Abdelhamied, M. M., Abdelreheem, A. M. & Berber, M. R. Flexible Methyl cellulose/polyaniline/silver composite films with enhanced linear and nonlinear optical properties. Polym. (Basel). 13, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13081225 (2021).

Elkattan, M. & Gad, M. Tuning the optical constants of PVA based films for optoelectronic applications. Opt. Commun. 527 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2022.128979 (2023).

Heiba, Z. K., El-Naggar, A. M., Kamal, A. M., Lakshminarayana, G. & Mohamed, M. B. Optical, Structural, and dielectric characteristics of flexible PVA/PEG/ZnMn2O4/CuCo2O4/x wt % Melanin blended polymer composites. J. Macromolecular Sci. Part. B: Phys. 64, 641–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222348.2024.2362532 (2025).

Abdel Maksoud, M. I. A., Awed, A. S., Sokary, R. & Bekhit, M. Effect of gamma irradiation on the free-standing Polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan/Ag nanocomposite films: insights on the structure, optical, and dispersion properties. Appl. Phys. Mater. Sci. Process. 127 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-021-04776-3 (2021).

Wang, M. et al. Poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogels: the old and new functional materials. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2021 https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/2225426 (2021).

Teixeira, M. A., Amorim, M. T. P. & Felgueiras, H. P. Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) -Based Nanofibrous Electrospun Sca ff olds for Tissue Engineering Applications, (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12010007

Heiba, Z. K., Badawi, A., Ali, E. E., Ibrahim, R. M. & Mohamed, M. B. Electromagnetic radiation shielding and fluorescence properties of Polyvinyl Alcohol/Polyvinyl pyrrolidone blended polymer loaded with nano Vanadium/Cadmium zinc sulfide. J. Macromolecular Sci. Part. B: Phys. 0, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222348.2025.2481725 (2025).

Muhammad, D. S., Aziz, D. M. & Aziz, S. B. Green synthesized inorganic Mn-metal complex as a novel approach to modify the optical band gap of PVA polymer, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42247-025-01102-y (2025).

Devi, C. U., Sharma, A. K. & Rao, V. V. R. N. Electrical and optical properties of pure and silver nitrate-doped Polyvinyl alcohol films. Mater. Lett. 56, 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-577X(02)00434-2 (2002).

Ghanipour, M. & Dorranian, D. Effect of Ag-Nanoparticles doped in Polyvinyl alcohol on the structural and optical properties of PVA films. J. Nanomater. 2013 https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/897043 (2013).

Jassim, T. A. & Saeed, A. A. Effect of gamma irradiation on the physical properties of PVA polymer. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 928 https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/928/7/072137 (2020).

3, M. M. & Algarni, H. E. Ali1 Abdel-Aziz1, 4,*, I.S. Yahia1, The structure analysis and optical performance of PVA films doped with Fe3+-metal for UV- limiter, and optoelectronics, Materials Research Express 154.59.124.171 on 09/06/2019 at 22:26 0–14.https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ab2668 (2019).

Elhosiny Ali, H. & Khairy, Y. Microstructure and optical properties of Ni2 + doped PVA for optoelectronic devices. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 570, 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2019.05.050 (2019).

Soliman, T. S., Vshivkov, S. A. & Elkalashy, S. I. Structural, linear and nonlinear optical properties of Ni nanoparticles – Polyvinyl alcohol nanocomposite films for optoelectronic applications. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 107 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2020.110037 (2020).

Mamand, D. M. et al. Enhanced optical properties of Chitosan polymer doped with orange Peel dye investigated via UV-Vis and FTIR analysis. Sci. Rep. 15, 3232. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87425-6 (2025).

Abdelhamied, M. M., Abdelreheem, A. M. & Atta, A. Influence of ion beam and silver nanoparticles on dielectric properties of flexible PVA/PANI polymer composite films. Plast., Rubber Compos. 51, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14658011.2021.1928998 (2022).

Mohamed, M. B., El-naggar, A. M., Heiba, Z. K. & Kamal, A. M. Effect of CdS/M doping on the dielectric and radiation shielding of PVA/PEG composite film. Ann. Nucl. Energy. 216, 111321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2025.111321 (2025).

Polu, A. R. & Kumar, R. Preparation and characterization of Pva based solid polymer electrolytes for electrochemical cell applications. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. (English Edition). 31, 641–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10118-013-1246-3 (2013).

Santos, A. M. N. et al. Physically cross-linked gels of PVA with natural polymers as matrices for Manuka honey release in wound-care applications. Materials 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12040559 (2019).

Saadiah, M. A., Zhang, D., Nagao, Y., Muzakir, S. K. & Samsudin, A. S. Reducing crystallinity on thin film based CMC/PVA hybrid polymer for application as a host in polymer electrolytes. J. Non Cryst. Solids. 511, 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2018.11.032 (2019).

Hema, M., Selvasekarapandian, S., Arunkumar, D., Sakunthala, A. & Nithya, H. XRD and ac impedance spectroscopic study on PVA based polymer electrolyte doped with NH4X (X = Cl, Br, I). J. Non Cryst. Solids. 355, 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2008.10.009 (2009).

Bhargav, P. B., Mohan, V. M., Sharma, A. K. & Rao, V. V. R. N. Structural, electrical and optical characterization of pure and doped Poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA) Polymer electrolyte films. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomaterials. 56, 579–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/00914030600972790 (2007).

Mohamed, M. A., Halawy, S. A. & Ebrahim, M. M. Non-isothermal decomposition of nickel acetate tetrahydrate. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 27, 109–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-2370(93)80002-H (1993).

Saranya, S., Dhanapandian, S., Nagarajan, S., Suthakaran, S. & Krishnakumar, N. Hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of nanostructured nickel diselenide (NiSe2) from the decomposition of nickel acetate tetrahydrate (Ni(CH3COO)2).4H2O. Mater. Lett. 277, 128398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2020.128398 (2020).

Kumar, D., Singh, H. & Banerjee, S. Controlled design of phase specific Ni nanoparticles from different precursors and their antibacterial activities. Adv. Sci. Eng. Med. 8, 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1166/asem.2016.1866 (2016).

Yano, S., Yamashita, H., Matsushita, M., Aoki, K. & Yamauchi, J. Structure and molecular motion of ethylene-acrylic acid copolymers neutralized with manganese (II) and nickel (II) acetates, colloid and polymer science kolloid zeitschrift &. Z. Für Polymere. 259, 514–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01397889 (1981).

Sangeetha, R. & Muthukumaran, S. Investigation of optical, structural, FTIR and magnetic properties of Sn substituted Zn0.98Mn0.02O nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 42, 5921–5931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2015.12.140 (2016).

Kavitha, P. & Laxma Reddy, K. Synthesis, structural characterization, and biological activity studies of Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2014 https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/568741 (2014).

Chandra, S. & Gupta, L. K. EPR and electronic spectral studies on Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) complexes with a new tetradentate [N4] macrocyclic ligand and their biological activity. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 60, 1563–1571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2003.08.023 (2004).

Cai, H. et al. Thermal degradations and processes of waste tea and tea leaves via TG-FTIR: combustion performances, kinetics, thermodynamics, products and optimization. Bioresour Technol. 268, 715–725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2018.08.068 (2018).

Y.L. Jianhui ye a,b, fangyuan fan a, Xinqing Xu b, interactions of black and green tea polyphenols with whole milk. Food Res. Int. 53 449–455 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2013.05.033 (2013).

Ali, F. M., Kershi, R. M., Sayed, M. A. & AbouDeif, Y. M. Evaluation of structural and optical properties of Ce3 + ions doped (PVA/PVP) composite films for new organic semiconductors. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 538, 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2018.03.031 (2018).

Rahman Khan, M. M., Akter, M., Amin, M. K., Younus, M. & Chakraborty, N. Synthesis, luminescence and thermal properties of PVA–ZnO–Al2O3 composite films: towards fabrication of Sunlight-Induced catalyst for organic dye removal. J. Polym. Environ. 26, 3371–3381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-018-1220-9 (2018).

Abral, H. et al. Effect of ultrasonication duration of Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) gel on characterizations of PVA film. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9, 2477–2486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.12.078 (2020).

Wu, Z. et al. Physical properties and structural characterization of starch/polyvinyl alcohol/graphene oxide composite films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 123, 569–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.071 (2019).

Lin, D. et al. Physico-mechanical and structural characteristics of starch/polyvinyl alcohol/nano-titania photocatalytic antimicrobial composite films. Lwt 96, 704–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2018.06.001 (2018).

Cmc, P. V. A., Film, C. & Wang, C. Effect of Na2CO3 on the microstructure and macroscopic properties and mechanism analysis of PVA/CMC composite film, 1–13 https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12020453 (2020).

Popescu, M. C., Dogaru, B. I., Goanta, M. & Timpu, D. Structural and morphological evaluation of CNC reinforced PVA/Starch biodegradable films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 116, 385–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.05.036 (2018).

Abdel-Kader, M. H., Mohamed, M. B., Alharby, T. & Ibrahim, R. M. UV-Irradiation effects on the Structural, optical and electrical characteristics of soft blended polymeric materials loaded with Multi-Walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs). J. Macromolecular Sci. Part. B: Phys. 64, 531–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222348.2024.2357916 (2025).

El-naggar, A. M. et al. Electrical and structural investigations of PVA/CMC/PPy/MWCNTs blended polymer composites for energy storage applications. Ceram. Int. 50, 44195–44211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.08.269 (2024).

Shah, S. A. et al. Effect of carbon nanotubes and zinc oxide on electrical and mechanical properties of Polyvinyl alcohol matrix composite by electrospinning method. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79477-x (2024).

Muhammad, D. S., Aziz, D. M. & Aziz, S. B. Green tea dye ligands to transfer toxic lead metal ions to precipitated metal complexes for polymer composite applications. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12609-z (2025).

Muhammad, D. S., Aziz, D. M. & Aziz, S. B. The impact of green chemistry to synthesize PVA/cobalt metal complexes (CoMCs) composites with enhanced optical behavior. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 158, 116448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2024.116448 (2025).

Adhikari, S. & Banerji, P. Polyaniline composite by in situ polymerization on a swollen PVA gel. Synth. Met. 159, 2519–2524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synthmet.2009.08.050 (2009).

Choo, K., Ching, Y. C., Chuah, C. H., Julai, S. & Liou, N. S. Preparation and characterization of Polyvinyl alcohol-chitosan composite films reinforced with cellulose nanofiber. Materials 9, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9080644 (2016).

Reguieg, F., Ricci, L., Bouyacoub, N., Belbachir, M. & Bertoldo, M. Thermal characterization by DSC and TGA analyses of PVA hydrogels with organic and sodium MMT. Polym. Bull. 77, 929–948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-019-02782-3 (2020).

Pal, M. K. & Gautam, J. Effects of inorganic nanofillers on the thermal degradation and UV-absorbance properties of Polyvinyl acetate. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 111, 689–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-011-2153-x (2013).

Abdel Maksoud, M. I. A., Awed, A. S., Sokary, R. & Bekhit, M. Effect of gamma irradiation on the free-standing Polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan/Ag nanocomposite films: insights on the structure, optical, and dispersion properties. Appl. Phys. Mater. Sci. Process. 127, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-021-04776-3 (2021).

El-Zaidia, E. F. M., Ali, H. A. M., Hamdalla, T. A., Darwish, A. A. A. & Hanafy, T. A. Optical linearity and bandgap analysis of erythrosine B doped in Polyvinyl alcohol films. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 100 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2020.109661 (2020).

Abd-Elnaiem, A. M., Rashad, M., Hanafy, T. A. & Shaalan, N. M. Improvement of optical properties of functionalized Polyvinyl Alcohol-Zinc oxide hybrid nanocomposites for wide UV optoelectronic applications. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 33, 2429–2444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10904-023-02616-w (2023).

Ali, H. E. et al. Microstructure study and Linear/Nonlinear optical performance of Bi-Embedded PVP/PVA films for optoelectronic and optical Cut-Off applications. Polym. (Basel). 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14091741 (2022).

Aziz, S. B. et al. Structural and optical characteristics of pva:C-dot composites: tuning the absorption of ultra Violet (uv) region. Nanomaterials 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9020216 (2019).